Oxford University Press's Blog, page 913

August 15, 2013

Sophie Elisabeth, not an anachronism

An intriguing post popped up in my Tumblr feed recently, called “The all-white reinvention of Medieval Europe” from the blog Medieval POC. Both in this post and generally throughout the blog the author makes the point that “People of Color are not an anachronism”, and goes into great detail about the whitewashing of European medieval art, with the removal or suppression of the representation of People of Color therein by later historians.

It got me thinking about how women composers are often treated as an anachronism. Music history classes tend to jump from Hildegard von Bingen straight to Libby Larsen, and even then as a sort of afterthought. (Granted, it’s been about ten years since I’ve taken a music history course, so perhaps things have changed since then.) Coincidentally enough, it was brought to my attention not long after reading the Medieval POC post that Tuesday marks the 400th anniversary of composer Sophie Elisabeth, Duchess of Brunswick-Lüneburg’s birth. Never heard of her? Neither had I.

In her “Women in Music” article on Grove Music Online, Judith Tick writes that Sophie Elisabeth was one of the earliest documented German female composers after the Middle Ages. Born on 20 August 1613, Sophie Elisabeth was also a poet and librettist, as well as being what we today might call an arts administrator. She was responsible for the organization of the court orchestra and established a tradition of several annual performances of various types (plays, ballets, masquerades), for which she also wrote some of the music. Sophie Elisabeth worked closely with Heinrich Schütz (he was kind of a big deal back then), who started out as her musical adviser and later collaborated with her on at least one project. He called her a “uniquely accomplished princess, particularly in the worshipful calling of music.” She composed several hymn melodies, as well as four Singspiele (“sung plays”), among other works. Sadly, most of her work is either lost or very difficult to access.

As composer Kristin Kuster recently pointed out in the New York Times, “we’ve still got a long way to go” before today’s women composers are represented in equal numbers with today’s men composers on faculties and in the concert hall. Similarly, we’ve still got a long way to go before the women composers of the past are represented in a way that even comes close to the representation of the men composers of the past. It would be excellent if the music history books of the near future were woven through with women composers, instead of patching them in here and there.

As a parting gift I leave you with this 1977 documentary about the 20th century composer Nadia Boulanger commemorating her 90th birthday. It’s really more about her illustrious career as a composition teacher than as a composer, but interesting nonetheless. Bonus: you get to hear Leonard Bernstein speaking fluently in French.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Additional reading/listening:

“A Suggestion for Composer of the Week — some women” on The Rambler, including three woman-composer Spotify playlists

The Grove Music Online “Women in music” timeline (subscription required)

Kyle Gann’s “My Favorite Women Composers of All Time” list

Or, you know, google it!

Meghann Wilhoite is an Assistant Editor at Grove Music/Oxford Music Online, music blogger, and organist. Follow her on Twitter at @megwilhoite. Read her previous blog posts on Sibelius, the pipe organ, John Zorn, West Side Story, and other subjects.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Sophie Elisabeth, not an anachronism appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAnthems of AfricaLullaby for a royal babyNo love for the viola?

Related StoriesAnthems of AfricaLullaby for a royal babyNo love for the viola?

Walter Scott’s anachronisms

By Ian Duncan

One of Sir Walter Scott’s creations has been much in the news lately: his country house at Abbotsford was formally reopened to the public by Her Majesty the Queen on 3 July 2013, following a £12 million restoration. Abbotsford looms large in recent accounts of Scott as (in Stuart Kelly’s phrase) “the man who invented a nation” — the Romantic Scotland of tartan-swathed Highlanders that still enthralls the popular imagination, two hundred years after Waverley and The Lady of the Lake. For much of the twentieth century critics and historians denounced “Scott-Land” as a garish anachronism, woven from a tissue of anachronisms, the fantastic fabric of an ancient nation draped over the real one. Abbotsford, Scott’s gas-lit “Conundrum Castle,” was its architectural confection, a misbegotten attempt at feudal revival in an industrial age. The relics with which the house is crammed (Rob Roy’s gun and sword, Prince Charlie’s quaigh, the door of “The Heart of Midlothian”) transform the object-world of Scottish history into a jumble sale of props from its author’s fiction.

Now that the Union is relaxing its grip on Scotland, the disavowal of Scott no longer seems a necessary rite of nationalist passage. A more tolerant, curious, even appreciative interest in his achievement is emerging, even if Abbotsford and other spectacular artefacts of the “invention of Scotland” (George IV’s 1822 state visit to Edinburgh, stage-managed by Scott; the Scott Monument on Princes Street) overshadow the poems and novels that made him the most famous author of the nineteenth century. Today, after a long hiatus in which those poems and novels dropped out of print, we are well placed to rediscover the originality — the imaginative audacity and experimental strangeness — that once took the Atlantic world by storm.

The Scott Monument in Edinburgh

Scott was not most celebrated for his Scottish fictions, wildly popular though they were. The man who invented a nation didn’t stop at one but went on to give the English their idea of England too, in Ivanhoe , his glittering romance of the twelfth-century greenwood. Ivanhoe installed a myth of national origins that still conditions the popular idea of the Middle Ages: Robin Hood, the Black Knight, Richard the Lionheart, boozy monks, sinister Templars, they are all there. Some have found Scott’s medievalism as objectionable as his tartanry. Professional historians were quick to point out the novel’s errors and anachronisms, from details of costume and weaponry to its grand theme, the colonial antagonism between Normans and Saxons, and its pastiche of antique English, the most brilliant stylistic experiment in British fiction before Joyce’s Ulysses . But Ivanhoe is “A Romance,” as its subtitle promises, not a historical treatise. Its errors and anachronisms are knowing rather than symptomatic. They do creative and critical work.Take the Jews, Isaac and Rebecca, Scott’s treatment of whom disrupts the novel’s official story of the foundation of English upon a reconciliation between alien races. Triangulating the opposition between Saxon and Norman, the Jews dismantle it — revealing both as bloody-minded Anti-Semites. Scott makes Rebecca by far the most admirable character in Ivanhoe. She embodies chivalric and Christian virtues more convincingly than any of the novel’s warriors and clerics, even as she resists a series of attempts to convert her to Christianity. Scott dramatizes her resistance as principled, even heroic, an eloquent refusal of the universal history (of Christianity’s digestion of its Jewish heritage) that underwrites the national history of assimilation. At the close of the novel, Ivanhoe and his friends look forward to a happy domestic settlement, while Rebecca and her father prepare for an exile that will transport them not just in space but in time, three hundred years into the future, to the court of “Mohammed Boabdil, King of Granada” — Abu Abdallah Mahommed XII, last of the Nasrid Sultans, who surrendered his kingdom to the Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella in 1492. The Reconquista meant the final expulsion of the Jews from Spain as well as of Muslims who would not convert to the new order. Scott’s audacious anachronism reminds us that further cycles of dispossession await Rebecca and her people — a dispossession Scott’s readers should have recognized as reaching into their own historical present. At the same time, Rebecca speaks for an ecumenical ideal of tolerance and magnanimity that none of the Christians in Ivanhoe can live up to. Through her we glimpse another kind of history, one very different from the English destiny of compromise and settlement: a radically unsettled, unfinished history, of worldwide dispossession and wandering, but also of utopian aspiration and humanist hope — the products, it seems, of that very condition of dispossession and wandering.

The union that ends the novel seems smaller in every sense, lacking spiritual grandeur, than the sublime horizon that opens around Rebecca. Readers who wished Ivanhoe had married Rebecca rather than the fair Saxon Rowena, and rewrote the end of the novel to satisfy their preference, were not being perverse. Scott baits the end of his romance with a yearning that cannot be assuaged by any literal rewriting, since it occupies the gap between a universal ideal of human possibility and what a contingent, merely national history can afford. The most imaginative treatments of that yearning would be by George Eliot, who makes withheld unions — between Dorothea and Lydgate in Middlemarch, between the Christian Gwendolen and the Jew Daniel in Daniel Deronda — structurally central to her great novels of the 1870s. As for the gap: wishing, Scott’s novel insists, will never close it.

Ian Duncan, Florence Green Bixby Professor of English at the University of California, Berkeley, has edited Scott’s Ivanhoe and Rob Roy for Oxford World’s Classics. His edition of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped will be published next year.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: The Scott Monument in Edinburgh. By Tony Hisgett [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Walter Scott’s anachronisms appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories10 questions for Wayne KoestenbaumA children’s literature reading list from Oxford World’s ClassicsWhy we should commemorate Walter Pater

Related Stories10 questions for Wayne KoestenbaumA children’s literature reading list from Oxford World’s ClassicsWhy we should commemorate Walter Pater

August 14, 2013

Three recent theories of “kibosh”

The phrase put the kibosh on surfaced in texts in the early thirties of the nineteenth century. For a long time etymologists have been trying to discover what kibosh means and where it came from. Hebrew, Arabic, Turkish, Gaelic Irish, and French have been explored for that purpose. I have twice discussed the word in this blog: on 19 May and on 28 July 2010. My modest aim was to call attention to the existing conjectures and sort them out. I also thought that the unexpected sense of kibosh “Portland cement” might furnish a clue to the sought-for etymology. No one supported my idea, and I am aware of three recent attempts to solve the puzzle. They belong to J. Peter Maher (who has thought about this word for a long time), Stephen Goranson, and David L. Gold. The first has not been published in full, but I have Professor Maher’s permission to use the versions he sent me (some of them exist on the Internet). Goranson’s work appeared in the periodical Comments on Etymology (2010) and Gold’s in Revista Alicantina de Estudios Ingleses (2011). I assume that neither Comments on Etymology nor Revista Alicantina has wide currency among the readers of this blog (however, Goranson’s hypothesis has been referenced by Michael Quinion in World Wide Words). It may therefore be useful for our readers to have a brief summary of the views of the three scholars side by side.

The only authentic kibosh. All others are counterfeit. But which of the three is the authentic-est of all?

The earliest attestation of kibosh in the OED1 went back to Dickens’s kye-bosk (sic; 1836), but now several occurrences of the word in newspapers for 1834 are known. The predating per se would have had little value because if some word caught Dickens’s attention in 1835 or 1836, naturally, it must have existed earlier. Yet thanks to it we have proof that kibosh indeed emerged in “low” speech around 1830+. Whether it led an underground existence before it turned up in London slang cannot be decided. No etymology offered so far explained why kibosh conquered the capital when it did. What provoked the vogue for it? Its original pronunciation also remains a riddle. Even if we disregard Dickens’s -bosk with its strange -sk (a typo?), there is no certainty that the word was stressed on ki- or that the first vowel was “short” (as in sit, rather than as in site); the spelling kibbosh has also been recorded. At least one old woman who has participated in the Internet discussion said that she had always heard kibosh stressed on the second syllable. Whatever the origin of kibosh, it does resemble several homophones from various languages, and the coincidence, perhaps fortuitous, may have contributed to the word’s dissemination. With the present evidence at our disposal, the chance of unearthing the origin of kibosh is vanishingly small.

J. Peter Maher traces kibosh to French caboche “head (informal), noodle, nut” or rather the English verb cabosh (from French) “to cut off a stag’s head behind the ears (with no part of the neck in view) as a trophy.” Both the noun and the verb are common terms in heraldry. In French, caboche, an irreverent word for a human head, has also become a surname (Caboche). “It was the Cockneys of London who turned the aristocratic verb cabosh into a slang expression…. Likewise, a Cockney expression for the 1d./6p. coin was cabosh for the head of the monarch on coins.” Maher assumed that the story began with the verb and that the noun was formed from it. Usually etymologists derive the verb kibosh from the noun: “…we can say spin the ball or transform this into the style put a spin on the ball.” The development of kibosh was allegedly similar. Maher has no trust in the modern spelling of kibosh. In his opinion, i after k was an imperfect way of rendering the unstressed vowel of the first syllable, while “the spelling kye-bosh is based on mispronunciation of the troublesome spelling kibosh.” This etymology does not say how a term of heraldry reached “the Cockneys,” but, as noted, no one has explored the zigzags of the word’s history from a putative etymon to nineteenth-century slang. It is not even clear whether those zigzags can be reconstructed.

Stephen Goranson. The issue of Comments on Etymology (CoE, 2010), mentioned above, contains a mass of material on the early attestation of kibosh (correspondence among several people and Gerald Cohen, the journal’s editor) and Cohen’s summary. It turned out that another researcher (Matthew Little) had offered the same etymology as Goranson, but his contribution (also to CoE!) was not published in 2009. However, Goranson’s material is incomparably richer than Little’s. His etymon of kibosh is kurbash “a long whip made of hippopotamus or rhinoceros hide used as an instrument of punishment in parts of the Muslim world.” Like kibosh, kurbash has been attested in many forms. The phrase put the kibosh on seems to presuppose that a kibosh is an object that can be raised or at least “put on.” (As we have seen, this reasoning did not go far with Maher.) Judging by the attestation, there was some confusion between kurbash and kibosh, at least in texts. The difficulties Goranson faces are predictable. Once again we are tied to a form with initial stress. Even in an r-less dialect ur and i (short) do not look like interchangeable spelling variants of the same unstressed vowel (schwa), the more so as even koorbash and korbash occur. From this point of view kibosh with long i fares even worse. (Long i makes us admit that today’s most common pronunciation of kibosh is due to its spelling image or to what Maher calls mispronunciation—a strange development for slang.) The word is exotic, and accepting it as the etymon of kibosh presupposes the familiarity of the London street with it some time before 1842. These obstacles are hard to explain away. My last remark will be unconnected with kurbash. In commenting on my post, Goranson wrote that kibosh “Portland cement,” the gloss to which I attached special importance, turned out to be impossible to verify. I have not dealt with this question since 2010.

David L. Gold informs us that his article, though it takes up 56 pages of the journal issue, is a reduced variant of a more comprehensive study. It will probably become a book when he brings it out. At present it contains 33 pages of text, 23 compact pages of notes (many of them highly entertaining), and an extensive but incomplete bibliography that features, among others, 42 references to his own works, some still in manuscript. Gold’s starting point is the clogmakers’ term kibosh “iron bar about a foot long that, when hot, is used to soften and smooth leather” (another long and menacing object!). Putting the kibosh on a clog might perhaps mean “finish the work.” Or did the idiom at its inception have the sense “to make the thing fit” (a recorded sense)? If so, a stag’s head and a whip fade out of the picture. Knowing nothing about the technology of clog making, I cannot judge at what stage a kibosh was put on the leather. Let experts comment on this detail; I will stick to my last. Other than that, the spread of a technical expression from some locality to the rest of the country (according to Gold, kibosh originated in the north of England) and becoming part of the universally known slang is possible. The very word slang has such a history, and professional language is a common source of colloquialisms.

However, Gold has hardly drawn the curtain over the bothersome problem. The main handicap is partly familiar to us from the previous exposition. Kybosh “an iron bar,” even if native, is a rare word, to say the least, and the phrase put the kibosh (on) has not been recorded in any technical description of clog making. The origin of the word kibosh, regardless of the collocation in which it occurs, also remains obscure. In the past, clogmakers used the verb bosh, sometimes alternating with burnish, whose sense was “rub waxed and oiled leather with a hot iron bar.” Gold suggested tracing bosh to burnish, but this derivation is unlikely for phonetic reasons. If bosh is the second part of kibosh, ki will be unaccounted for. Long ago, Charles P.G. Scott, the etymologist for The Century Dictionary, considered the possibility of ki- being identical with ca-, as in caboodle, or ker-, as in kerfuffle. Gold supported this idea, though he gave no reference to Scott. I am afraid both of them were wrong. This prefix of Celtic or Dutch origin is never stressed (as far as I can judge, unlike Maher, neither Scott nor Gold doubted the initial stress in kibosh), never has the form ki- with long i (that is, the diphthong ai: here again, unlike Maher, Scott and Gold took long i for granted), and is never added to stylistically neutral words (though the stylistic register of bosh cannot be assessed). One might even suggest that bosh was “abstracted” from kibosh by way of back formation. I also wonder (and in this I am quite alone) why people said the kibosh rather than a kibosh. Is the definite article here of the same type as in spare the rod, spoil the child?

The word kibosh, English clogmakers’ lingo notwithstanding, looks foreign. But at the moment it is “stateless,” like so many other refugees of our time.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: (1) Stag’s head erased (heraldry). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) The ‘Chicote’ or whip via NYPL Digital Library. (3) A pair of leather clogs by Vincent van Gogh/ Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Three recent theories of “kibosh” appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAlphabet soup, part 2: H and YAlphabet soup, part 1: V and ZMonthly etymological gleanings for July 2013

Related StoriesAlphabet soup, part 2: H and YAlphabet soup, part 1: V and ZMonthly etymological gleanings for July 2013

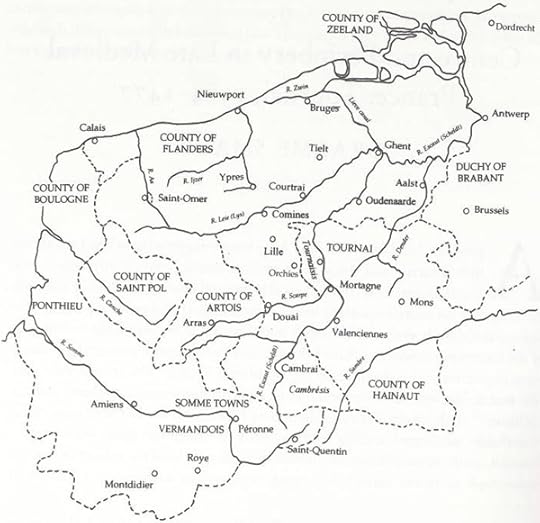

Crossbow competitions and civic communities

In the popular imagination, tournaments feature prominently as the greatest spectacles of the Middle Ages. If archery competitions are thought of, it is probably in the context of Robin Hood films or the great English longbow (and the successes it brought, particularly Agincourt). Yet the archery and crossbow competitions organised by guilds across Northern France and the Low Countries had dramatic entrances with dragons and play wagons, took over marketplaces for weeks (even months) at a time, and allowed princes to interact with townsmen. In studying the guilds and their competitions, I have tried to understand why such elaborate and exciting events were staged.

Photo by Laura Crombie. Reproduced with permission of City of Ghent, City Archives, Fonds Sint Joris, 155, 1.

One of the earliest crossbow competitions was held in Oudenaarde, in central Flanders, in 1328 with local teams shooting for a few days and rewarded with wine. Competitions grew in size and splendour; by the fifteenth century events typically lasted for two-three months and took over civic space, dominating towns as few other events ever did. Prizes became more elaborate, with silver dragons (for their association with Saint George, the patron saint of many crossbow guilds), roses, gems, unicorns, even a silver monkey — all awarded for best individual shot, best team, best entrance, best costume, best play, or for hitting the centre of target.

Town accounts make clear the importance of honour in funding guilds and competitions. In 1394 the crossbowmen of Douai attended a competition in Tournai and were initially given just £26; but when the aldermen heard they had won prizes, they received another £41, 17 sous ‘for the honour of the town’. These are no empty words. In travelling across a number of different counties, perhaps even national borders, the archers and crossbowmen became important civic representatives: in civic livery, pulling memorable play floats, funded by civic finances. Competitions allowed towns to represent their identity on a regional scale.

In looking at the chronology of archery and crossbow competitions, and in analysing attendance patterns, the role of competitions within inter-regional networks can be appreciated. Rather than being staged in year of tension in the build up to wars or rebellion, perhaps for training, the greatest competitions were held just after conflict, to use martial displays to rebuild festive and commercial networks. One of the earliest competitions in Tournai was held in 1344, just four years after the town have been besieged by an Anglo-Flemish force under Edward III, as part of his attempt to enforce his claim to the throne of France. Tournai was a French Episcopal city, but relied upon its northern neighbours, especially Flanders and Brabant, for trade so it had to restore and rebuild urban networks. A crossbow competition had become the best way to restore peace.

Tournai held another great competition in 1455. The event’s declared purpose was to celebrate the recent victories of the French king, in driving the English out of France save Calais and effectively ending the Hundred Years War. The competition shows Tournai again using a crossbow competition to show and enhance its place within Flemish and Brabant urban networks. The attendance at the 1455 competition, with 59 guilds from 45 towns, none of which were French, shows that despite its loyalty to the French crown, Tournai was culturally, festively, and commercially tied to lands ruled by the Valois Dukes of Burgundy.

In G. Small ‘Centre and periphery in late medieval France: Tournai, 1384-1477,’ in War, Government and Power in Late Medieval France. Ed. C. Allmand (Liverpool, 2000). Used with permission. All rights reserved.

Urban networks and civic priorities in funding archery and crossbow competitions were fluid and evolved depending on the political situation. With the death of the last Valois duke of Burgundy, Charles the Bold, in 1477, France and the Low Countries were at war. Tournai became the centre of a prolonged and violent campaign, with daily pillaging and burning. The violence of 1477 tore Tournai from its urban networks. Though competitions were held in the 1480s, to try to restore peace as the event of 1344 had done, they were less spectacular, and Tournai was no longer willing to spend significant sums on civic networks, or on using the archers and crossbowmen to build bonds with Flemish towns. In a Ghent contest in 1498, the Tournai entrance was one of the smallest, showing that competitions were not longer a civic priority capable of winning civic honour and building bonds with neighbouring towns.

Archery and crossbow competitions were every bit as spectacular as jousts, with costumes and plays, as well as weeks of shooting. They were put on at great cost for towns to show their status and to enhance regional communities. The competitions developed across the fourteenth and fifteenth century, giving towns and townsmen opportunities to show civic identity and to win honour. They also built festive networks, strengthening social and economic inter-urban connections. But they were bound up with political events and ripped apart by the violence of 1477.

Dr Laura Crombie is a lecturer in Medieval History at the University of York. She publishes on the social history of the archery and crossbow guilds of Flanders and is currently engaged in studying other urban groups and urban festivities in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. She is the author of “French and Flemish urban festive networks: archery and crossbow competitions attended and hosted by Tournai in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries” (available to read for free for a limited time) in French History.

French History offers an important international forum for everyone interested in the latest research in the subject. It provides a broad perspective on contemporary debates from an international range of scholars, and covers the entire chronological range of French history from the early Middle Ages to the twentieth century.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Crossbow competitions and civic communities appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBetween self-murder and suicide: the etymology of a modern stigmaMoney, prices, and growth in pre-industrial EnglandAre HD broadcasts “cannibalizing” the Metropolitan Opera’s live audiences?

Related StoriesBetween self-murder and suicide: the etymology of a modern stigmaMoney, prices, and growth in pre-industrial EnglandAre HD broadcasts “cannibalizing” the Metropolitan Opera’s live audiences?

Spain’s unemployment conundrum

There is only a glimmer of light in Spain’s long unemployment tunnel after five years of recession. This is because a new economic model has yet to emerge to replace the one excessively based on the property sector, which collapsed with devastating consequences.

The depth of Spain’s crisis is such that the country, with 11% of the euro zone’s GDP and a population of 47 million, has 5.9 million unemployed (around one-third of the zone’s total jobless), whereas Germany (population 82 million and 30% of the GDP) has only 2.8 million jobless (15% of the zone’s total).

Spain’s unemployment rate of 26.2% is the highest in the developed world (more than double the euro zone average) and five times higher than Germany’s rate of 5.3%, the lowest since reunification in 1991, and it is forecast to remain at around this level for several years.

This disproportionate difference cannot be explained away by Germany’s widely used kurzabeit system, under which companies agree to avoid laying off workers and instead reduce their working hours, with the government making up some of the employers’ lost income, or by Spain’s labor market laws.

The Spanish economy has not contracted significantly more over the last five years than the German, French or Italian economies, and yet its jobless rate, unlike in these other countries, has skyrocketed.

The problem is as much related to Spain’s lopsided and unsustainable economic model, disproportionately based on the labor-intensive property sector. This model created millions of jobs, mostly temporary ones, when the economy was booming and destroyed them equally massively when the housing bubble burst. Moreover, it acted as a magnet for immigrants, without whom so many houses could not have been built. Their unemployment rate is 35%. Of the 3.7 million jobs shed since 2007, 1.6 million were in construction.

Railway in Bilbao, Spain. Image by tpsdave via Pixabay.

The government’s labour market reforms have lowered dismissal costs and give companies the upper hand, depending on their financial health, in collective wage bargaining agreements between management and unions. Facilities were provided to adapt working conditions, including hours and salary.

The reforms are having no significant impact on job creation. They will, however, lower the GDP growth threshold for net job creation from around 2% to 1.3% when the economy starts to grow again. But Spain is not expected to expand by more than 1% until 2018, according to the IMF’s latest forecasts.

The previous economic model was incapable of creating jobs on a sustained basis and a new model has yet to emerge. Given the state of the education system and the large pool of unskilled workers, it will be very difficult to change the model. One in every four people in Spain between the ages of 18 and 24 are early school leavers, double the European Union average but down from a peak of one-third during the economic boom, when students dropped out of school at 16 and flocked in droves to work in the construction sector. Equally worrying is that one-quarter of 15-29 year-olds are not in education, training or employment (known as Ni-Nis).

Results in the OECD’s Pisa tests in reading, mathematics, and scientific knowledge for 15-year-old students and for fourth-grade children in the TIMS and PIRLS tests are also poor; no Spanish university is among the world’s top 200 in the main academic rankings and research and development and innovation spending, at 1.3% of GDP, is way below that of other developed economies.

In these conditions, a more knowledge-based economy is a pipe dream, compounded by the government’s short-sighted cuts in R&D and education spending. Furthermore, the decision of the US company Las Vegas Sands to site Europe’s largest casino, conference, and hotels complex on the outskirts of Madrid accentuates the already skewed economic model.

The IMF has urged the government to deepen its labour market reforms in order to lower unemployment. The Bank of Spain raised the controversial idea of suspending the minimum wage in certain circumstances. One option would be a German-style mini jobs scheme.

The one bright spot is exports, but this sector cannot create sufficient jobs to make a major dent in unemployment.

With the construction and property sectors unlikely to get back on their feet for a decade, massive job cuts in the public administrations in order to cut the budget deficit and depressed domestic consumption discouraging the creation of new firms, the employment outlook is bound to remain bleak. For how long will Spaniards remain so resilient?

William Chislett, the author of Spain: What Everyone Needs to Know, is a journalist who has lived in Madrid since 1986. He covered Spain’s transition to democracy (1975-78) for The Times of London and was later the Mexico correspondent for the Financial Times (1978-84). He writes about Spain for the Elcano Royal Institute, which has published three books of his on the country, and he has a weekly column in the online newspaper El Imparcial.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Spain’s unemployment conundrum appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe fall of the Celtic Tiger – what next?Five things you should know about the FedBetween self-murder and suicide: the etymology of a modern stigma

Related StoriesThe fall of the Celtic Tiger – what next?Five things you should know about the FedBetween self-murder and suicide: the etymology of a modern stigma

Between self-murder and suicide: the etymology of a modern stigma

Translated from German by Dominic Bonfiglio

Some words can kill. Even those one wouldn’t have thought so to look at. Consider “self-murder.” Perpetrators of this supposed crime die a second, linguistic death in retribution for their deed — eye for eye, tooth for tooth. Persons who utter the word send a clear message: take your life and you kill not only yourself but also the society that feeds you. For many centuries, loss of honour, memory, and property followed the act as a posthumous reminder. At stake was more than a symbolic, social death. Even in the late nineteenth century, British courts could punish attempted self-murder with death by hanging. Religion usually supplied the rationale. For the God-fearing judiciary, those who repudiated the gift of life disturbed the order of creation. God’s representatives on earth could not let such a transgression go unpunished, and denied the guilty the salvation of a Christian burial.

Other words can liberate. “Voluntary death” takes against the condemnatory tradition and insists on the moral right to end one’s own life, even if few choose to do so. Today English speakers typically use the ostensibly neutral term “suicide.” Its use has become so natural and widespread that its historical origins have been mostly forgotten. The word originated under the influence of Enlightenment thought, as denunciation of the deed gradually gave way to empathy for the doer. In England this process began in the 1650s; in France and Germany it started in the second half of the eighteenth century, with German giving rise to the equivalent term Selbstentleibung (“self-disembodiment”). The attendant decriminalisation of self-killing turned self-murder into suicide. Sinners and criminals became victims and patients, melancholics and the mentally ill.

The notion of suicide rendered the act’s aetiology more important than the act itself. A pictorial representation of this conceptual shift can be found in William Hogarth’s cycle Marriage à la Mode (1743-45). The six-painting series depicts the unhappy consequences of an arranged marriage between a wealthy merchant’s daughter and the son of a bankrupt earl. The woman, bored by her husband of convenience, soon embarks on an extramarital liaison with a silver-tongued lawyer. At a tryst in a bath house, the two lovers are surprised by the cuckolded spouse, who is then fatally wounded in a scuffle with the paramour. In the final painting the woman poisons herself out of grief after her lover is hanged for murder.

William Hogarth (1697-1764), “The Suicide of the Countess,” from Marriage à la Mode, The National Gallery, London.

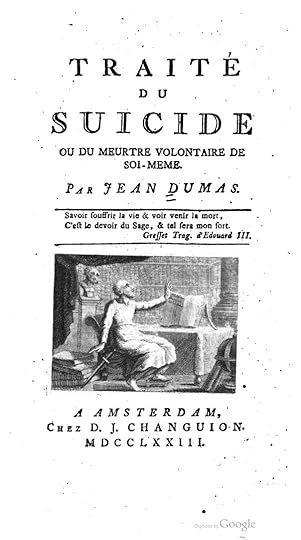

At first glance, the cycle seems not to condemn suicide but to track its causes and circumstances, not to judge the deed but to understand its origins. Yet there’s reason to doubt the veracity of this apparent liberation. Historically, the concept of suicide did not simply replace that of self-murder. While self-murder is the older term, it only predates suicide by several decades, appearing in the second half of the sixteenth century; both entered the vocabulary of the early modern era more or less together, and have coexisted ever since. They made self-killing into a linguistic entity and with it, into a matter of fact, first juridical and then moral. Hogarth seems to trace the woman’s death back to a moral error, saying in effect: look what happens to couples who enter into arranged marriage. But the narrative’s implied premise is that suicide is morally reprehensible. Accordingly, it is neither accident nor sloppiness when Samuel Johnson, in his Dictionary of the English Language (1755-56), defines suicide as “Self-murder; the horrid crime of destroying one’s self,” or when the reformed preacher Jean Dumas titles one of his works, a particularly voluminous tome, Du suicide ou du meurtre volontaire de soi-même (1773).

Jean Dumas, Traité du Suicide ou du meurtre volontaire de soi-même (Amsterdam, 1773).

In the course of the eighteenth century a person who took his or her own life assumed, almost invariably, the status of a melancholic adjudicated as mentally incompetent. The reclassification failed to exorcise the underlying moral stigma, however: pathologization implied the original contemptibility of the act it sought to exonerate; otherwise there would have been no need for it. Pathologization and contemptibility frame the modern idea of what it means to be a free and morally autonomous person; which is to say, of what it means to have forsaken the sphere in which God and His servant the Devil determine human action. Going hand in hand with this perspective is a concept of society that is vulnerable to suicide while also being one of its sources, though not its ultimate cause.

In the late nineteenth century the belief that self-killing was the symptom of individual and societal illness was systematized in the study of suicidology. The discourse’s psychiatric, psychological, and sociological categories, by eliminating individual accountability, removed from the deed its culpability as well as its dignity. Those with suicidal tendencies are now placed in the custody of a therapist; the invention of suicide merely replaced one stigma with another. To this day, whoever takes his own life can hardly hope for understanding. Who knows how many this knowledge has driven to despair.

Andreas Bähr is a researcher at the Free University of Berlin. He is the author of “Between ‘Self-Murder’ and ‘Suicide’: The Modern Etymology of Self-Killing” (available to read for free for a limited time) in the Journal of Social History.

The Journal of Social History has served as one of the leading outlets for work in this growing research field since its inception over 40 years ago. JSH publishes articles in social history from all areas and periods, and has played an important role in integrating work in Latin American, African, Asian and Russian history with sociohistorical analysis in Western Europe and the United States.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Images: (1) William Hogarth (1697-1764), “The Suicide of the Countess,” from Marriage à la Mode, The National Gallery, London. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Jean Dumas, Traité du Suicide ou du meurtre volontaire de soi-même (Amsterdam, 1773). Public domain via Google books.

The post Between self-murder and suicide: the etymology of a modern stigma appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMoney, prices, and growth in pre-industrial EnglandAre HD broadcasts “cannibalizing” the Metropolitan Opera’s live audiences?A cool president: what you might not know about Calvin Coolidge

Related StoriesMoney, prices, and growth in pre-industrial EnglandAre HD broadcasts “cannibalizing” the Metropolitan Opera’s live audiences?A cool president: what you might not know about Calvin Coolidge

August 13, 2013

Money, prices, and growth in pre-industrial England

At a time when governments across the world are pursuing the elusive goal of economic growth, it may be instructive to consider the historical evidence for growth in Britain.

A hoard of gold angels (1470 to 1526) recently discovered in Oxfordshire. Image courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum.

Recently, economic growth has been addressed in a Leverhulme project involving Stephen Broadberry, Bruce Campbell, Alexander Klein, Mark Overton and Bas van Leeuwen, which offers annual estimates of British GDP from 1270 to 1870. The Broadberrry-Campbell team’s estimates confirm Paul Bairoch’s proposed method of estimating pre-industrial GDP fundamentally dependent on population levels. The team’s findings associate GDP closely with population until c.1700, when industrial, agricultural, and technological developments began to liberate GDP from population. However, even before 1700 the Broadberry-Campbell team’s work suggests that economic growth may have been a pre-condition of population growth. From the thirteenth century at least, economic growth matches or exceeds demographic growth.

Given the marriage patterns in Britain, and the requirement that couples establish a means of support before setting up home, this is not surprising. Kussmall has shown how marriage in seventeenth-century south-west England correlated with economic opportunity. Even more explicitly, Langdon and Masschaele have observed that “there is a powerful conjunction between entrepreneurial activity and population growth.”

These insights also have a bearing on the influence of population change on price levels. Ever since the 1950s some, perhaps most, historians have associated rising population levels with the great inflationary periods of the thirteenth-fourteenth centuries and early modern period (1550-1650). The argument was that rising population created increased demand which pushed up prices.

This interpretation challenged the monetary explanation of price movements based on the Quantity Theory. (Traditionally Quantity Theory explains the behavior of prices as MV=PT, in which M stands for money stock, V for the velocity of circulation, P for the price level, and T for the level of transactions. Nowadays Quantity Theory usually replaces T with GDP, the measure of the size of the economy, represented by the symbol Y.) Over the last 50 years demographic and monetary interpretations of price history have contested the subject.

However, new work on economic growth suggests that while population did undoubtedly rise during the periods of inflation, so too did GDP. In other words, though demand rose, so too did supply, which might be expected to have neutralised the effect of rising population on prices.

As we have observed already, in the period 1250 to 1750 population levels and GDP were always closely associated, and estimates of the size of the money stock have little importance without an understanding of the size of the economy that the money stock has to service. In this sense, population levels find a place within the Quantity Theory, but the demographic role influences not only demand but also supply. If this is accepted, the long-standing and increasingly sterile battle between monetary and demographic explanations for the behaviour of prices can be drawn to a close. Money clearly influences the price level, as does velocity, but the size of the economy remains an essential element in the equation. Economic growth emerges as a fundamental influence on population and on price levels.

The reassertion of Quantity Theory should not be seen as a victory for the Chicago school since Keynesian observations about the role of velocity (or its inverse, demand for money to hold) and the effect of time lags remain important qualifications. Still more importantly, much depends on the quality of our estimates of GDP, prices, and the money stock.

Nick Mayhew is a fellow of St Cross College, Oxford, and director of the Winton Institute for Monetary History in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. He is the author of “Prices in England, 1170–1750” in a recent issue of Past and Present, which is available to read for free for a limited time.

Founded in 1952, Past & Present is widely acknowledged to be the liveliest and most stimulating historical journal in the English-speaking world.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Money, prices, and growth in pre-industrial England appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAre HD broadcasts “cannibalizing” the Metropolitan Opera’s live audiences?Recent advances and new challenges in managing painOn ‘work ethic’

Related StoriesAre HD broadcasts “cannibalizing” the Metropolitan Opera’s live audiences?Recent advances and new challenges in managing painOn ‘work ethic’

Buddhism beyond the nation state

Concern with the limitations imposed by presuming contemporary geo-political divisions as the organizing principle for scholarship is not new, nor is it limited to Buddhist studies. Jonathan Skaff opens his recent Sui-Tang China and Its Turko-Mongol Neighbors: Culture, Power, and Connections, 580–800 by quoting Marc Bloch’s 1928 address to the International Congress of Historical Sciences (1928): “It is high time to set about breaking down the outmoded topographical compartments within which we seek to confine social realities, for they are not large enough to hold the material we try to cram into them.”

Skaff is not alone in his intention to overcome “the normal practice of professional historians to take the nation-state as the primary unit of analysis.” At the recent Association for Asian Studies (ASA) conference, four scholars, each in their own way, spoke to the constraints imposed by privileging geo-political categories as the structures by which Buddhism is apprehended, raising issues directly relevant to the discussions made here regarding the rhetorical and lexical consequences of categorizing Buddhism according to the convenient artifice of the nation-state. They propose instead to explore Buddhism in the broader context of Asian history as a civilization that introduced new social institutions and languages, established new agricultural technologies and trading relations, and transformed the environment beyond national borders and ethnic categories.

Reflecting on the problematic organizational hierarchy of contemporary Buddhist studies, which employs regional categories based on the ‘area studies’ model subdivided further into national categories, David Gray (University of Santa Clara) questions the category Tibetan Buddhism. In his essay “How Tibetan is Tibetan Buddhism? On the Applicability of a National Designation for a Transnational Tradition,” he points out that today there is no Tibet to which this label can refer. Additionally, arguably the majority of practitioners of “Tibetan” Buddhism neither are ethnic Tibetans, nor do they speak or read Tibetan. More significantly, while Tibetans considered themselves Buddhists and had a sense of Tibet as a distinct geo-political category, “they simply did not conceive of their tradition in nationalistic terms.” Since there is no equivalent for “Tibetan Buddhism” in premodern Buddhist literature from Tibet, Gray suggests “Vajrayāna.” This is itself an emic category (rdo rje theg pa), and also identifies a form of Buddhism that stretches across many national boundaries. Thus, it allows for further designation as needed, but without precluding meaningful comparisons. For example Kūkai and Tshong Khapa can be juxtaposed as Vajrayāna teachers, rather than separated as Japanese and Tibetan respectively.

Anya Bernstein (University of Michigan) further examines the way in which Buddhist social identities can be both formed by and recognized in terms of lineage and reincarnation, rather than nationality or ethnicity. In her essay “Indigenous Cosmopolitans: Mobility, Authority and Cultural Politics in Buryat Buddhism,” she focuses on two ethnically Tibetan monks from the (new) Drepung Monastery, who are recognized by Buryat Mongolians as having Buryat “roots.” The first is a reincarnated Buryat lama who had gone to Tibet in the late 1920s and died while incarcerated by the Chinese. He reincarnated in a Tibetan expatriate family in Nepal, and is now a member of the Drepung monastery. The second was the disciple of a Buryat monk. Both lineage and reincarnation serve to establish connections with the Buryat Buddhist community on bases distinct from nationality or ethnicity.

Gerdeng Monastery. Photo by Jialiang Gao. February 2003. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

That the convenient nation-state model is inadequate for an accurate in-depth understanding of Buddhism in the context of Asian history is also made obvious by Tansen Sen (Baruch College, City University of New York). Focusing on the works of several figures from the 1920s and 1930s, Sen shows that the idea of peaceful cooperation between India and China on the basis of Buddhism was invented by projecting back the contemporary nation-states into the ancient past. The consequence of constructing this imaginary history is that the contributions of all the other peoples—Sogdians, Tokharians, Uighurs, and so on—were left out. Instead we find “simplistic models and misperceptions that continue to have considerable impact on contemporary views about the pre-colonial interactions between South Asia and the region that is now within the borders of the People’s Republic of China.”

While the epistemological issue of contemporary intellectual concerns molding historiography is well-recognized, Sen reveals something more blatant. The political goals held by individuals in the early twentieth century created a pan-Asianist rhetoric, including a mythology of peaceful relations between two continuously existing unitary nations. The representation is false on both counts; not only were the relations not peaceful, but the contemporary nation-states also do not constitute continuous political entities stretching back to the second century CE. This representation was created to serve divergent political purposes. When the goal was resistance to the European colonial powers, Japan was included as part of the pan-Asianist rhetoric. When the goal was China requesting India’s help in resisting Japan’s invasion, the rhetoric was restructured to emphasize only the Buddhist connection between these two countries.

Johan Elverskog (Southern Methodist University) has addressed the ecological impact of Buddhism across the entire landscape of Asia in a paper entitled “The Buddhist Exchange: Irrigation, Crops and the Spread of the Dharma.” The term “exchange” here, borrowed from environmental studies, refers to the way expansion of human societies transforms the environment by transmitting new crops and agricultural technologies from one region to another. Clearing the misconception of Buddhism as inherently environmentally friendly, a “green” religion, Elverskog then provides a panoramic overview of the impact of the expansion of Buddhism across the entirety of the Asian continent. The expansion of the monastic institution was not simply a “religious” event, but included introducing wet-rice agriculture, and irrigation technologies into new regions. This affected vast regions across Asia, simultaneously creating population growth and the conditions for urbanization. Seen thus, Buddhism is not only a collection of abstruse doctrines, but a complex social institution affecting people’s lives and transforming the environment in very concrete ways across national boundaries.

As organizing principles, lineage and reincarnation can work across ethnicity and nationality. “Tibetan Buddhism” is neither emic to premodern Tibet, nor does it identify a presently existing nation-state, nor were the forms of Buddhism called “Tibetan” ever delimited by either ethnic or national boundaries. The mythology of Buddhism as a peaceful bridge between India and China ignores the important roles played by other groups that were the links between the two. The Buddhist civilization that spread across Asia brought new crops and new technologies. The categories that have long served to organize Buddhist studies have been largely based on nation-states, giving us such familiar categories as Chinese Buddhism, Thai Buddhism, Korean Buddhism, or Tibetan Buddhism. The recent work by these scholars and others reveal that such categories are problematic. While there may be particular research programs for which they are appropriate, they cannot simply be presumed and used by default.

Richard K. Payne is the Dean of the Institute of Buddhist Studies at the Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley; serves as Editor-in-Chief of the Institute’s annual journal, Pacific World; is chair of the Editorial Committee of the Pure Land Buddhist Studies Series; and is Editor-in-Chief of Oxford Bibliographies in Buddhism. He also sporadically maintains a blog entitled Critical Reflections on Buddhist Thought: Contemporary and Classical.

Developed cooperatively with scholars and librarians worldwide, Oxford Bibliographies offers exclusive, authoritative research guides. Combining the best features of an annotated bibliography and a high-level encyclopedia, this cutting-edge resource guides researchers to the best available scholarship across a wide variety of subjects.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Buddhism beyond the nation state appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAn interview with Sarah JaphetAn interview with Sarah Japhet - Enclosure10 questions for Wayne Koestenbaum

Related StoriesAn interview with Sarah JaphetAn interview with Sarah Japhet - Enclosure10 questions for Wayne Koestenbaum

A cool president: what you might not know about Calvin Coolidge

The 3rd of August marked the 90th anniversary of Calvin Coolidge swearing in as the 30th President of the Unites States following the sudden death of Warren G. Harding. Calvin Coolidge won re-election in 1924. In The Forgotten Presidents: Their Untold Constitutional Legacy, Michael Gerhardt uncovers the overlooked vestiges of his presidency, highlighting five interesting things you may not have known about Calvin Coolidge.

Calvin Coolidge, photo portrait head and shoulders, seated. 1919. Photo by Notman Photo Co., Boston, Mass. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

(1) He supported lower taxes and smaller government.

“[Calvin Coolidge] was the first President to champion the need for ‘lower taxes, less government, and more freedom.’ [Ronald] Reagan admired Coolidge because he, ‘cut taxes 4 times. We had probably the greatest growth and prosperity that we’ve ever known. [I have] taken head of that, because if he did nothing, maybe that’s the answer [for] the federal government.’”

“’The functions which the Congress are to discharge are not those of local government. The greatest solicitude should be exercised to prevent any encroachment upon the rights of the states or their various political subdivisions. Local self-government is one of the most precious possessions. It is the greatest contributing factor to the stability, strength, liberty, and the progress of the Nation.’”

(2) He spoke pointedly and understood the power of the press in spreading his words.

“Coolidge was the last President to write his own speeches and he deliberately kept them short. The average length of Coolidge’s sentences was 18 words — by comparison Lincoln’s average was 26.6 words and George Washington’s was 51.5.”

“In spite of his distaste for interacting with the press, he recognized the institutional advantage of a president’s using the press to bypass Congress and to speak directly to the American people. Hence, Coolidge held press conferences twice a week, regularly made off-the-record comments to the press, and generally tried to use the press to facilitate public awareness of — and support for — his administration. Indeed Coolidge was the first president to have his State of the Union broadcast nationally.”

(3) He fought corruption.

“Because he inherited Harding’s scandal-ridden administration, Coolidge became the first twentieth- century president to address the constitutional and political fallout from the misconduct of high-ranking, executive branch officials whom he had not appointed.”

“Coolidge became the first president who appointed special prosecutors to investigate a single scandal and allowed them to complete their mission with no interference at all on his part.”

(4) He enforced the power of the presidency.

“Coolidge’s strong exercises of his veto and pardon authorities belie his image as Silent Cal. The statistics along underscore how much he embraced these powers: He issued 1,545 pardons, the second most pardons (after Wilson) issued by a president before Franklin Roosevelt; and he cast fifty vetos, the fourth largest number cast by any president before Franklin Roosevelt and the most cast by any president, except for Teddy Roosevelt, from 1900-1933.”

(5) He regulated radio broadcast frequencies.

“Coolidge signed into law the nation’s first federal regulation of radio broadcasting. Initially commercial broadcasting was a small part of the industry, and the stations broadcasting often aired on overlapping frequencies. The industry lobbied the federal government for support, but it got none until Coolidge became president. As he declared, ‘This important public function has drafted into such chaos as seems likely, if not remedied, to destroy its great value.’ Coolidge signed the Radio Act into law in 1927. It declared the airwaves public property and therefore subject to federal control pursuant to Congress’s Commerce Clause power. Over the next few decades, the Radio Act erected a foundation for modern broadcast regulation.”

Elyse Turr joined Oxford University Press in May 2006. She is the marketing manager for Oxford’s esteemed History list.

Michael Gerhardt is Samuel Ashe Distinguished Professor of Constitutional Law at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. A nationally recognized authority on constitutional conflicts, he has testified in several Supreme Court confirmation hearings, and has published five books, including The Forgotten Presidents and The Power of Precedent.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A cool president: what you might not know about Calvin Coolidge appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWho inspired President Abraham Lincoln?Reparations and regret: a look at Japanese internmentPresidential fathers

Related StoriesWho inspired President Abraham Lincoln?Reparations and regret: a look at Japanese internmentPresidential fathers

Are HD broadcasts “cannibalizing” the Metropolitan Opera’s live audiences?

When the Metropolitan Opera launched its high-definition broadcast initiative in 2006, hopes were very high. The basic concept was simple: the Met would offer live cinema broadcasts of its Saturday matinee performances to a network of movie theaters around the country. For many decades the Met had offered such access to radio listeners, but now audiences far from New York could both see and hear their favorite Met stars from their local cineplex, for only about $20 a ticket, less than even a standing-room ticket at the company’s home at Lincoln Center.

Soon to enter their eighth season, the Met “Live in HD” has indeed emerged as the most successful initiative of the tenure of General Manager Peter Gelb, whose main goal has been to make opera a more popular and accessible art form. The HD broadcasts are the most spectacular aspect of this agenda and are now being screened in almost 2,000 movie theaters in over 60 different countries. The Met has also established a SiriusXM satellite radio station, as well as offering its own “Met On Demand” service with extensive online content.

But despite these innovative programs, Gelb’s record as leader of the Met, the largest performing arts organization in the country, has been rocky at best. Alex Ross of The New Yorker has repeatedly questioned Gelb’s artistic vision and institutional priorities, in particular the massive investment in Robert LePage’s elaborate “machine” for the house’s new production of Wagner’s Ring. Even the amiable Anthony Tommasini of the New York Times proposed not too long ago that Gelb hire an artistic advisor of some sort, a suggestion that has yet to be acted upon. (In Gelb’s defense, the artistic vision of the company has been significantly compromised by the failing health of music director James Levine, whose sporadic presence has left artistic leadership in a semi-permanent limbo.)

Amid such turmoil, Gelb has happily been able to point to the Met’s HD initiative has an undisputed success. Each year the broadcasts have brought in bigger audiences and more revenue, and for several seasons have been turning a profit. The cinemas that host the broadcasts are also quite happy with the results; with overall movie attendance in decline, they are grateful for the extra foot traffic, and popcorn sales.

But at the Met’s season announcement this past spring, Gelb made a somewhat stunning admission. While citing the continued success of the HD initiative in terms of attendance and revenue, he revealed that ticket sales at the Met’s actual performances had witnessed a decline. This was perhaps in part due to an ill-timed hike in ticket prices, which the Met has rescinded for the coming season. But Gelb shockingly posited an additional cause: the increased access to HD broadcasts were “cannibalizing” the Met’s live audiences.

It seems that even audiences with geographic access to the Met are increasingly opting for the mediatized Met over the live version. If even the powerful Metropolitan Opera can’t keep audiences coming in person, how does this bode for smaller regional opera companies, who now have to compete with the Met’s broadcasts in their own communities? In places such as San Luis Obispo, California, organizations are using the broadcasts as a means to identify new ticket buyers and donors, a model that other organizations would be well advised to adopt. Sports fans and pop music audiences continue to sell out live games and concerts despite the widespread availability of mediated versions. Can opera achieve this same success? For the time being, the answer remains to be seen.

James Steichen is a PhD candidate in musicology at Princeton University who is completing a dissertation on George Balanchine and the early history of the New York City Ballet. You can read more on his research into the Metropolitan Opera “Live in HD” in his Opera Quarterly article “HD Opera: A Love/Hate Story.”

Since its inception in 1983, The Opera Quarterly has earned the enthusiastic praise of opera lovers and scholars alike for its engagement within the field of opera studies. In 2005, David J. Levin, a dramaturg at various opera houses and critical theorist at the University of Chicago, assumed the executive editorship of The Opera Quarterly, with the goal of extending the journal’s reputation as a rigorous forum for all aspects of opera and operatic production.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only theatre and dance articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Promotional web banner for the Metropolitan Opera’s 2013-14 Live in HD Season via metoperafamily.org. Used for the purposes of illustration.

The post Are HD broadcasts “cannibalizing” the Metropolitan Opera’s live audiences? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBreaking Bad: masculinity as tragedyIn memoriam: George DukeUNDRIP, CANZUS, and indigenous rights

Related StoriesBreaking Bad: masculinity as tragedyIn memoriam: George DukeUNDRIP, CANZUS, and indigenous rights

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers