Oxford University Press's Blog, page 917

August 4, 2013

Oil and threatened food security

Today, debate in the West remains largely focused on energy security and decreased dependence on foreign oil, but in the Middle East, an equally threatening crisis looms in a shortage of food and water. Ahead of the Agricultural and Applied Economics Association & CAES Joint Annual Meeting (4-6 August 2013 in Washington, D.C.), we present a brief excerpt from Eckart Woertz’s Oil for Food: The Global Food Crisis in the Middle East.

The deeply ingrained sensitivity about food self-sufficiency in the Arab world is reminiscent of the discourse about energy independence in the West. Historic precedence informs the threat perception. Dependence on food imports during WWII was fragile. An embargo-happy US politicized food trade in the 1970s. Domestic agro-lobbies in the Middle East also like to sing the praises of self-reliance in order to defend subsidies and access to scarce resources like water.

During the global food crisis of 2008, food prices skyrocketed and food exporters announced export restrictions. As a result, agricultural investments have moved to center stage of strategic considerations in the Middle East. Privileged access to food production is seen as a cornerstone of food security, if not at home for reasons of limited water resources and arable land, then at least in countries that are geographically close and beckon with established political and cultural ties like Sudan and Pakistan. If “drill baby drill” is regarded as a panacea for the energy challenge by some in the US, “plant baby plant” is the rallying cry of an equally convinced crowd in the Middle East.

Water scarcity has also rendered self-sufficiency but a dream. Since the 1970s, the Middle East as a whole cannot grow its required food supplies from renewable water resources anymore. Extremely water-scarce parts of it like Israel, Palestine, and desert Libya lost this ability in the 1950s already. So did the Gulf countries. Their recourse to mining of fossil water aquifers is unsustainable and the day of reckoning is drawing closer. Saudi Arabia has decided to phase out its subsidized wheat production by 2016. Groundwater depletion is an even more pressing issue in the Middle East than contentious cross-border sharing of surface water along the Nile, Euphrates, Tigris, and Jordan. As agriculture consumes around 80% of water, the easiest way to save it is to reduce agricultural production and direct scarce water resources to more urgent or more valuable uses in the residential, industrial, and service sectors.

Wheat harvest, Chirah, Bagrote Valley, Gilgit Baltistan, Pakistan, 2007 by Zensky. Creative commons license via Wikimedia Commons.

The perception of Gulf countries is one of threatened food security. With oil prices above $100 per barrel, rising food prices in the wake of the global food crisis were easy for them to stomach. They did not face the same challenges like their poor cousins in the rest of the Arab world. Their balances of payments were not stretched and they had the means to intervene in local food markets to stabilize prices. However, the export restrictions imposed by food exporters like Argentina, Russia, India, and Vietnam had an immense psychological impact. Gulf countries now face the specter that someday they might not be able to secure enough food imports at any price, even if their pockets are lined with petrodollars. This has reinforced the impression that food security is too important to be left to markets. Meanwhile, the political realities of the Arab food security debate have prompted approaches that are unsustainable and expensive.

The oil-for-food trade-off will be a determining factor for Middle East food security over the coming decades. Oil and gas revenues supply the bulk of the foreign currency that finances the growing food imports of the region, not only in the Gulf countries, but also in other exporter nations like Algeria, Libya, Iraq, Iran, the two Sudans, and Yemen. Furthermore, oil revenues reach the poorer neighbors of the Gulf countries indirectly in the form of aid, investments, and remittances by expatriate workers. They affect balance of payments and import options.

Oil and gas are also indispensable input factors of modern, globalized agriculture, which has grown dramatically since WWII and the Green Revolution in the 1960s. Mechanization, irrigation, and distribution networks need fuel. Nitrogen fertilizer from natural gas is crucial to feed 7 billion people. Other links between oil and food include the economics of biofuels and the impact of pollution and climate change on agricultural production capacity. The Middle East does not only play a prominent role in global oil markets as producer but also in global food markets as consumer. It imports already 1/3 of globally traded cereals.

International farmland investments are at the heart of the global food security challenge and put the Middle East in the spotlight of overlapping global crises in food, finance, and energy. Foreign agro-investments in poor countries that are food net importers like Sudan, Ethiopia, Pakistan, or the Philippines are controversial. They might compromise these countries’ domestic food security and infringe upon customary land rights of smallholders and pastoralists. There is an urgent need to structure investments with consideration of such stakeholders. Given the amount of publicity that Gulf land investments have attracted, two things are striking: (1) five years after their announcement few projects have been implemented; and (2) very little is known about the Middle East investors themselves. An increasing number of academic studies focus on the target countries. Less work has been done on the sources of investment. As far as they figure, accounts are based on secondary sources in English-speaking media that often take inflated numbers about land investments at face value. Why have Gulf countries started to undertake such investments? What role does their political economy of food play and what capacity constraints do they face? Why do they mistrust international markets? What geopolitical implications are behind the current investment drive? And why has there been such a gap between announcements and actual realization of projects?

Eckart Woertz is senior researcher at the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs (CIDOB). Formerly he was a visiting fellow at Princeton University, director of economic studies at the Gulf Research Center in Dubai, and worked for banks in Germany and the United Arab Emirates. He is the author of Oil for Food: The Global Food Crisis in the Middle East.

The Agricultural and Applied Economics Association & CAES Joint Annual Meeting will take place 4-6 August 2013 in Washington, D.C. Oxford University Press publishes Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy (AEPP) on behalf of Agricultural and Applied Economics Association. AEPP aims to present high-quality research in a forum that is informative to a broad audience of agricultural and applied economists, including those both inside and outside academia, and those who are not specialists in the subject matter of the articles.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Oil and threatened food security appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe good, the bad, the missed opportunities: UK governmentTest your knowledge of nutrition, health, and economicsWonga-bashing won’t save the Church of England

Related StoriesThe good, the bad, the missed opportunities: UK governmentTest your knowledge of nutrition, health, and economicsWonga-bashing won’t save the Church of England

Why we should commemorate Walter Pater

By Matthew Beaumont

Is there any point in celebrating the fact that 174 years ago today the art critic Walter Pater was born?

Pater’s most celebrated and controversial book, Studies in the History of the Renaissance (1873) is about the distant past, superficially at least, and therefore risked seeming irrelevant even in his own time. It could not however have inspired a generation of undergraduates, including Oscar Wilde, to embrace aestheticism and a cult of homoeroticism, as his critics claimed, if it had not also been a coded polemic about the present. But Pater’s thinking was also about the future. It is in this utopian dimension of Pater that I think should be celebrated in the twenty-first century. There is a good deal of point in looking back at the Walter Pater who was looking forward to the future.

Pater’s career as a published writer, from the mid-1860s to the mid-1890s, coincides almost exactly with the period in which, once the confidence in the capitalist system that had been characteristic of the third quarter of the nineteenth century had started to corrode, especially in the face of a sustained economic depression, utopian literature became an almost compulsory form of political discourse. Pater has not often been associated with this ideological climate because he is generally dismissed as apolitical. But his ‘impressionist’ criticism can nonetheless productively be reconsidered as a kind of social dreaming.

The aesthetic that Pater excavates from the past is in Studies in the History of the Renaissance intended to act as the foundation for an ethic that, in the future, might transcend the deformations of capitalist society, including the repression of homosexuality. The reception of this book, which was viciously attacked by conservative commentators, testified to the ethical implications of his criticism. But Pater’s prose also promoted a disposition that was inescapably political.

Plaque commemorating Walter Pater at 12 Earls Terrace, London.

Pater’s writings of the 1860s and 1870s look to the future. A utopian impulse is, for example, constituent of the piece that is generally said to inaugurate his intellectual biography: “Diaphaneitè.” This was an essay he read aloud in July 1864 to his intimates in the Old Mortality Society, a fraternity of young, mostly agnostic intellectuals studying at Oxford University. The Old Mortality, established in 1856, thrived for a decade as an alternative, albeit exclusive, forum for philosophical debate inside the university, and attracted a number of intellectual luminaries with radical reputations, including A.C. Swinburne and J.A. Symonds.Pater’s elusive title, “Diaphaneitè,” is intended to evoke a condition of diaphanousness, that is, a transparency of spirit at once luminous and mysterious. The paper is an enigmatic, highly poetic meditation on the “type of life,” as he puts it, which “might serve as a basement type.” By “basement type” he means the archetype that might form the foundation of a different social order, one that is peaceful and filled with a sense of completeness. Pater looks to the past, particularly the Hellenic past, for the proleptic image of a utopian future that might still be realizable; “the character we have before us is a kind of prophecy of this repose and simplicity, coming as it were in the order of grace,” he writes.

“Diaphaneitè” posits nothing less than the prototype of a utopian society. “The type must be one discontented with society at it is,” Pater declares, and the mass proliferation of this man of the future, he adds, “would be the regeneration of the world.” This is no activist though. “The philosopher, the saint, the artist, neither of them can be this type.” No, Pater’s “revolutionist,” to use his ascription, is the diaphanous type. In its perfect simplicity, this archetype represents a critique of the dessicated conditions of life in industrial society, one that is paradoxically both crystalline and quicksilver. In contrast to the saint, the artist, or the philosopher, who is so often “confused, jarred, disintegrated in the world,” the diaphanous type is “like a relic from the classical age, laid open by accident to our alien modern atmosphere.”

The diaphanous type embodies the youthful Pater’s utopian dreams of a homosocial society that might reinstate the ethics and aesthetics associated with the spirit of Hellenism. It is thought to have been inspired by Charles Lancelot Shadwell, a friend and former student famed for his handsomeness, and himself a member of the Old Mortality. “Often the presence of this nature,” Pater writes in tones that tremble with erotic excitement, “is felt like a sweet aroma in early manhood.” Pater subsequently dedicated Studies to Shadwell, who had in the summer of 1865 accompanied him on the trip to Italy during which he soaked up many of the impressions that permeate the book.

Pater’s paper on the diaphanous character might be described as an attempt to articulate a utopian politics that is apolitical. It acknowledges that to prognosticate about the Coming Race is to engage a political language, but it seeks at the same time to escape the logic of this political language by etherealizing it, diaphanizing it. What Pater hopes for is a revolution without revolution (which is rather different from a process of evolution, and rather more radical). “Revolution is often impious,” he wrote; “But in this [diaphanous] nature revolutionism is softened, harmonised, subdued as by distance. It is the revolutionism of one who has slept a hundred years.”

Pater’s revolutionist is a Rip van Winkle relieved to discover, on awakening from his epochal sleep, that the social transformation that has taken place in the meantime embodies not the sudden appearance of modernity but its utopian displacement. If a cryogenically preserved Pater were to be reborn on 4 August 2013, he would I suspect be disappointed to discover that, in spite of the dramatic advances achieved by homosexuals in the meantime, the diaphanous type of which he dreamed remains confined to a “basement type,” and isn’t the archetype of an open, liberated society. All the more reason, then, to commemorate Pater the revolutionist.

Matthew Beaumont is a Senior Lecturer in the English department at University College London. He has edited Walter Pater’s Studies in the History of the Renaissance and Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward 2000-1887 for Oxford World’s Classics.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Photo of plaque commemorating Walter Pater, By Simon Harriyott [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Why we should commemorate Walter Pater appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe first branch of the MabinogiDress as an expression of the pecuniary cultureThe misfortune of Athos

Related StoriesThe first branch of the MabinogiDress as an expression of the pecuniary cultureThe misfortune of Athos

August 3, 2013

A lion: Joseph Paxton in the nineteenth century and today

Two hundred years ago today, on 3 August 1813, Joseph Paxton turned ten. In a farm hand’s family of nine children, this was likely to have been a non-event. A decade after that, the day would also have come and gone like any other. At twenty, Paxton was pretty much on his own, working here and there in some outdoor capacity or other on nearby estates. While considering enrolling as an apprentice at the London Horticultural Society, the opportunity to train for an occupation as a gardener looked quite promising to a young man who otherwise had no prospects. Accepted at Chatsworth as a laborer later in 1823, Paxton was promoted to under-gardener within a couple of years. Then, after a few more months, the Duke of Devonshire proposed that he assume the post of head gardener. What this meant, apart from a fantastical break for Paxton, was that one hundred acres of pleasure grounds of one of the greatest of England’s great estates would come under the charge of a twenty-two-year-old greenhorn. The Duke, who leased land to the Horticultural Society, had happened to notice Paxton and find him agreeable. The officers of the society shrugged.

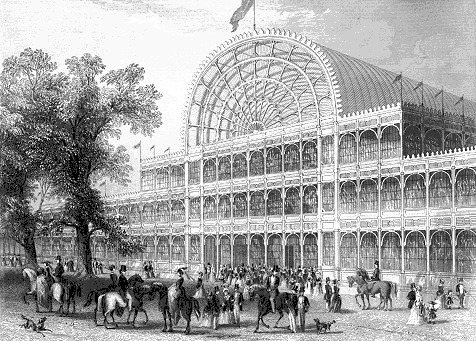

By the late 1830s, Paxton was the most celebrated gardener in garden-crazed Britain and the foremost glass-house designer in the world. In the 1840s, he also became a railroad tycoon in his own right and a media mogul. In 1850, he built the Crystal Palace, the glass colossus that epitomized one of the greatest original achievements of the Victorian age. In 1854, he rebuilt it on an even bigger scale. On the side, he laid out municipal parks and gardenesque cemeteries, drew up plans for castles, mansions, chateaux, formed the first civil engineering brigade, and hobnobbed with luminaries, dignitaries, and royals. All the while, he remained the Duke’s head gardener, as well as his faithful factotum, ever-ready sidekick, and best of all friends.

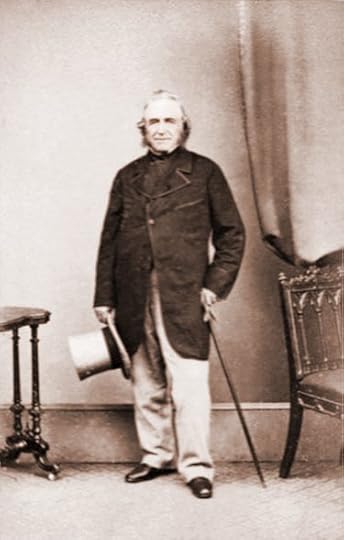

How do you account for a man like Paxton? Mid-century photos don’t offer a clue. Bewhiskered and balding, he has intelligent eyes and a pleasant enough face. A respectable middle-aged personage, you might say. A visionary man of action—probably not. He looks pretty staid. He was definitely quite stout. Yet he was more than a mover and shaker; he was a dynamo, a virtuoso, an ace in just about everything he tried, which was just about always something big, bold, and new.

Joseph Paxton circa 1860s. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

To be sure, Paxton had all the man-power and steam-power he could possibly want when undertaking the herculean endeavors that made Chatsworth’s grounds the most spectacular in the land, its waterworks and rockworks and houses of glass the grandest imaginable, its collections of flora the most luxuriant ever amassed. He also had access to the deep pockets of the lavishly extravagant Duke, who, in addition, was singularly and personally generous to his head gardener, gave him a gentleman’s education in art, architecture, and the ways of the world, took him on grand tours and shopping sprees, and introduced him to the great and the good. That Paxton’s wife preferred to be a homebody certainly helped free up Paxton to go gadding about with the Duke.

Blunt, brisk, and bossy, Sarah made an excellent proxy for her husband when he was gone from the estate (and even when he wasn’t). A shrewd businesswoman, with a keen eye for profit and an aversion to risk, she was also an ideal partner (and occasionally necessary counterweight) in his many and various independent enterprises and ventures (and together the two of them became very rich). In raising their seven children, Sarah was a vigilant matron. In dealing with her husband, she could be curt. But she also fussed over Paxton, whom she called her “Dear Dob” in tender moments (they were private, infrequent).

At any rate, between his employer and his wife, Paxton couldn’t possibly claim to be a self-made man, and never did—though now and then he did report to Sarah that in the circles where he moved he was a “lion.” The boast is pardonable: he was.

It’s often said that Paxton was a “genius.” The term doesn’t elucidate anything much. It does, however, have the advantage of suggesting he belonged in some rarefied realm that’s way above most of our heads. And, after all, even with all the resources at his disposal, there’s still something inexplicable about Paxton. His epic exploits can certainly stretch our credulity now. They sure baffled many a worldly witness then. How did he fashion an ancient-looking rockery from massive boulders and slabs and give it the authentically uncanny feel of a Stonehenge? For his glass houses, constructed from the most modern materials, using the latest efficiencies of industry, fairy tales served as the main reference point. The Great Conservatory at Chatsworth was pronounced to be “magical.” In Hyde Park, the Crystal Palace went up so fast that it seemed as though “Aladdin raised it one night.” “Dazzling the eye,” “bewildering the mind,” it “stunned” the overwhelming majority of visitors. Neither repeated explanations of the rationality of the design nor rote recitations of matters of fact seemed to have done anything to dispel the impression.

The front entrance of the Crystal Palace, Hyde Park, London that housed the Great Exhibition of 1851, the first World’s Fair. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Paxton’s resume has a somewhat similar effect. His works can be enumerated and explicated, his many and various enterprises, detailed. Still, cumulatively, his coups are staggering. He stands out as an overachiever amongst towering, overachieving Victorians. No one comparable leaps out from the ranks of phenoms today. And yet it seems quite likely that he’d be at home in the twenty-first century, amongst the outsized cult personalities of our customarily hyperbolically overcharged world. “Fortunate, not fortuitous”: that’s how Paxton described his achievements, absolutely begging the question. On this 210th anniversary of his birthday, it’s about as open-ended as it ever was.

Tatiana Holway is an independent scholar and academic consultant with a doctorate in Victorian literature and society. Author of several studies of Dickens and popular culture, she also serves on the advisory board for the Nineteenth-Century Collections Online global archiving project. Currently, she lives outside of Boston, where she pursues a passion for gardening. Her most recent book is The Flower of Empire: An Amazonian Water Lily, The Quest to Make it Bloom, and the World it Created.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A lion: Joseph Paxton in the nineteenth century and today appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe first branch of the MabinogiNine facts about athletics in Ancient Greece

Related StoriesThe first branch of the MabinogiNine facts about athletics in Ancient Greece

Recovery residences and long-term addiction recovery

Drug abuse and addiction are among the costliest of health problems, totaling approximately $428 billion annually. People recovering from substance abuse disorders face many obstacles in our current health care system. Dropout is common from detoxification and acute treatment programs, and many people who dropout relapse. This cycle often repeats many times with high personal and social costs. It has become increasingly clear that detoxification and short-term treatment programs are insufficient to ensure success; for most people with substance use disorders continued longer-term support following treatment is necessary. There are a number of community-based organizations that provide support to those following treatment, including self-help organizations such as AA. Unfortunately, groups such as AA do not provide needed housing, employment, or reliable sober-living environments. Halfway houses and therapeutic communities are one type of environmental support for many following substance abuse treatment. However, they have a number of limitations including length of stay, high cost, and required completion or involvement in some type of formal treatment.

In contrast, recovery residences are lower cost, community-based residential environments that require abstinence from substance use and abuse. Typically, residents can stay for as long as they want, but they are required to abstain from alcohol and illegal drug use and pay a modest rent to the recovery home owner. These residences go by a variety of different names (e.g., sober living houses, recovery homes, and Oxford Houses) and provide at a minimum peer-to-peer recovery support. Many recovery residences have staff to oversee operations and help link residents with treatment and other support services; some even provide these services directly to residents. Although the exact number of recovery residences is currently unknown, many thousands exist across the United States.

A small but growing body of research supports the effectiveness of recovery residences to promote abstinence and improve outcomes in a variety of other domains. Moreover, research generally finds that recovery residences don’t negatively affect neighborhoods and may even provide benefits to the communities in which they are located. Unfortunately, there continues to be formidable neighborhood and community opposition; operators often face barriers to obtaining funding to open and operate recovery residences. Critical stakeholders (e.g. health and human professionals, community leaders, and potential funders) are all too often unaware of the role that recovery residences can play in promoting long-term recovery.

The Affordable Care Act will have significant impact on the prevention and treatment of substance abuse disorders, including the integration of primary and behavioral health care, providing better screening, treatment, and referral practices to enhance behavioral health outcomes. These steps should result in a more chronic care-focused, integrated system that delivers better screening for at-risk individuals and services for relapse prevention. Recovery residences could play a major role in this new federal initiative to provide community-based support that could ensure more long term recovery following treatment.

Leonard A. Jason, professor of clinical and community psychology at DePaul University and director of the Center for Community Research, is the author of Principles of Social Change published by Oxford University Press. He has investigated the self-help recovery movement for the last 20 years. He is a member of the National Association of Recovery Residences Research Committee and has co-authored a policy paper on the role of recovery residences in promoting long-term recovery from addiction, which will be published in the American Journal of Community Psychology. Read his previous blog posts on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only social work articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: sad young man put his head on knees sitting on stone stairs. © Iogannsb via iStockphoto.

The post Recovery residences and long-term addiction recovery appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEven small government incentives can help tackle entrenched social problemsHumane, cost-effective systems for formerly incarcerated peopleBirds and Bees and Babies

Related StoriesEven small government incentives can help tackle entrenched social problemsHumane, cost-effective systems for formerly incarcerated peopleBirds and Bees and Babies

What is “toxic” about anger?

What is anger?

In essence, anger is a subjective feeling tied to perceived wrongdoing and a tendency to counter or redress that wrongdoing in ways that may range from resistance to retaliation (Fernandez, 2013). Like sadness and fear, the feeling of anger can take the form of emotion, mood, or temperament (Fernandez & Kerns, 2008).

What wrongdoings usually elicit anger?

Many psychological tests of anger present a list of anger-provoking scenarios, as in the Reaction Inventory (Evans & Strangeland, 1971), the Multidimensional Anger Inventory (Siegel, 1986), and the Novaco Provocation Inventory (Novaco, 2003). Some of the items on these inventories are highly specific. In general, research shows that wrongdoing is perceived not merely in the instance when one is physically assaulted. Wrongdoing also falls within several psychosocial categories: (i) insults or affronts, (ii) insensitivity or indifference, (iii) deception and betrayal, (iv) abandonment and rejection, (v) breach of agreement or promise, (vi) ingratitude, and (vii) exploitation.

Photo by Chris Sgaraglino, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

What is the difference between the experience and expression of anger?

A common saying is that the good or the bad is not in anger per se but in “what you do with it.” In other words, it is not the experience of anger but its expression that determines whether it is appropriate or not. After all, in the psychoevolutionary perspective, anger (like any affective quality) has evolved to serve a function. That function, in the case of anger, is to mobilize the individual to counter or redress a wrongdoing, just as fear would serve to mobilize the individual to escape or avoid, and sadness might demobilize the individual to the point of yielding or giving up.

So, should we direct our attention to the expression of anger more so than the experience of anger? Not so fast! There is abundant research showing that anger itself has deleterious effects on one’s health. Foremost among these is the effect on cardiovascular function. One striking observation in this regard is that a one-point increase in externalized anger or internalized anger is associated with a 12% increase in the risk of hypertension (Everson et al., 1998).

But anger is virtually unavoidable in human relations and to eradicate it as we go about eradicating smallpox and other pathogens would be unrealistic in the world as we know it. Therefore, it makes more sense to direct our efforts to the expression of anger.

What makes anger dysfunctional?

The typical answer uttered in response to this question is “violence” or “aggression.” However, clinical anecdotes are replete with people who do not get aggressive or violent, yet harbor anger that impairs their relationships in work, family, and social settings. As Averill (1983) astutely pointed out, anger can occur without aggression and vice versa. Anger may be expressed along a variety of dimensions (Fernandez, 2008): it may be reflected or deflected, internalized or externalized, physical or verbal, resistance or retaliation, controlled or uncontrolled, and restorative or punitive. Elevations on particular dimensions can be plotted to form configurations that reflect such diagnoses as intermittent explosive disorder or passive aggressive personality.

Of course, any psychometric scores or profiles of anger should not be divorced from the particular context in which the anger occurs. A diagnosis of Intermittent Explosive Disorder, for example, hinges on the extent to which the aggressive outburst is out of proportion to the provoking event. As with other so-called “mental disorders,” broader sociocultural contextualization is also crucial when reaching conclusions about what is a disorder and what is not. However, one provocative question that arises is whether a whole sociocultural standard for the expression of anger could be dysfunctional – a matter for further debate.

One lesson that emerges in the search for what is wrong with anger is that it is not just the (culturally unsanctioned) blatantly aggressive anger that is maladaptive. Anger that is expressed in covert and indirect ways has also been the object of much interest dating back to the famous Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (BDHI; Buss & Durkee, 1957). For there is much in anger that is not manifest but masked, not obvious but insidious, and such anger may also have considerable destructive potential to others, not to mention the long-term ill effects exerted on the person who harbors such anger.

Ephrem Fernandez will be signing copies of Treatments for Anger in Specific Populations from 11 a.m. to 12 noon on 3 August 2013 at OUP Booth #918 at the American Psychological Assocation Conference in Honolulu. He is currently a Professor at the University of Texas at San Antonio who teaches primarily in the areas of clinical and health psychology and conducts research on anger assessment, anger treatment, cognitive behavioral affective therapy, lexical approaches to pain assessment, and psychosomatic processes.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post What is “toxic” about anger? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPsychiatry and the brainWhere’s Mrs Y? The effects of unnecessary ward movesFrom RDC to RDoC: a history of the future?

Related StoriesPsychiatry and the brainWhere’s Mrs Y? The effects of unnecessary ward movesFrom RDC to RDoC: a history of the future?

August 2, 2013

What are you drinking?

Today is International Beer Day and there’s nothing we like to talk about more than a few good brews. Between the Oxford Companion to Beer, America Walks into a Bar, Beer: Tap into the Art and Science of Brewing, The Economics of Beer, and several episodes of The Oxford Comment, OUP employees have managed to imbibe a little expertise in the area. So we asked a few staffers about the brews they’ve been enjoying lately…

Matt Dorville, Digital Publishing Analyst, Reference

Matt Dorville, Digital Publishing Analyst, Reference

This is a beer I had with one of the tour guides (the cook actually) on a hike up the Salcantay trail to Machu Picchu. I learned two things from this trip: (1) I’m a terrible hiker. (2) I can outdrink Peruvian tour guides. While the first lesson led to very sore feet and quite a lot of complaining, the second one led to a couple of incredible nights. These beers (one of which you partly see here) might be some of the best beers I’ve ever had. They were Pillsen beer and while they aren’t my favorite beers (I tend to go for Belgium triples) they made me forget all the hiking I did that day and all the hiking I knew I had to do tomorrow. They also fermented a nice kinship with me and my guides on the tour and brought comradery in a way that beer can do to strangers who live worlds apart.

Owen Keiter, Publicity Assistant

For reasons unknown, my friends and I have begun to drink this bizarre concoctions made by Bud Light called the Lime-A-Rita. The drink comes in a large can, tastes sort of like a lemon-lime Gatorade that’s gone bad, and is high enough proof to knock you over if you’re not careful. Despite our lack of respect for the beverage, it’s strangely enjoyable, and it has begun appearing regularly in our apartment down in Bushwick. You enjoy it like a truly awful pop song — it’s the Vengaboys of booze.

Tim Allen, Assistant Editor, Reference

Though I live in New York City, I’m a Chicagoan by birth. New Yorkers may not know how to make a deep-dish pizza or a proper hot dog, but Goose Island IPA is a little taste of home that I can find just about anywhere in the city.

Alyssa Bender, Marketing Associate

I’m all about the craft beers, and as there are so many to work your way through, I like to try a different beer every time I go out. Right now I’m definitely more drawn to wheat beers and pale ales, and just tried Breckenridge Agave Wheat this past weekend—very smooth, refreshing, and enjoyable.

I’m also a sucker for Sam Adam’s Summer Ale. And come fall, any and all pumpkin ales. (Last fall I had one called “Braaaiins!” from the Spring House Brewing Company. Quite tasty.)

Jeremy Wang-Iverson, Senior Publicist

Jeremy Wang-Iverson, Senior Publicist

Certainly outdoor beer drinking is one of my favorite summer activities in NYC – I don’t want to use the august forum of the OUPblog to condone or suggest I have participated in any illegal activity, but I have noticed others finding ways to discretely sip adult beverages at Prospect Park concerts or under the Brooklyn Bridge. Some of the best establishments for drinking en plein air include Habana Outpost in Fort Greene, the Beer Garden in Astoria and….the Zeppelin in Jersey City, where this photo was taken this past July.

Jonathan Kroberger, Associate Publicist

OK I’ll be honest; I have no idea what I’m drinking here. But I do remember drinking it in a “German beer hall” in Jersey City on a recent OUP outing, so it’s fair to say I’ve been drinking lots of German beer lately. Generally there’s nothing crazy about them, no blueberries or sage leaves, nothing aged in wooden casks salvaged from an ancient shipping vessel. Just beer. My favorite is Ayinger’s Oktober Fest-Märzen. Pumpkins don’t get anywhere near this seasonal brew, yet it still manages to taste like a big glass of Fall.

What do you recommend enjoying this August?

Jonathan Kroberger is an Associate Publicist at Oxford University Press in New York.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only food and drink articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post What are you drinking? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAn ice cream quizMy 9 favorite bars in AmericaThe first branch of the Mabinogi

Related StoriesAn ice cream quizMy 9 favorite bars in AmericaThe first branch of the Mabinogi

The first branch of the Mabinogi

In celebration of the National Eisteddfod of Wales, we thought an excerpt from a Welsh classic would be appropriate. The Mabinogion is the title given to eleven medieval Welsh prose tales preserved mainly in the White Book of Rhydderch (c.1350) and the Red Book of Hergest (c.1400). They were never conceived as a collection—the title was adopted in the nineteenth century when the tales were first translated into English by Lady Charlotte Guest. Yet they all draw on oral tradition and on the storytelling conventions of the medieval cyfarwydd (‘storyteller’), providing a fascinating insight into the wealth of narrative material that was circulating in medieval Wales: not only do they reflect themes from Celtic mythology and Arthurian romance, they also present an intriguing interpretation of British history. Below is an excerpt from the tale ‘The First Branch of the Mabinogi’.

Pwyll, prince of Dyfed, was lord over the seven cantrefs of Dyfed. Once upon a time he was at Arberth, one of his chief courts, and it came into his head and his heart to go hunting. The part of his realm he wanted to hunt was Glyn Cuch. He set out that night from Arberth, and came as far as Pen Llwyn Diarwya, and stayed there that night. And early the next day he got up, and came to Glyn Cuch to unleash his dogs in the forest. And he blew his horn, and began to muster the hunt, and went off after the dogs, and became separated from his companions. And as he was listening for the cry of his pack, he heard the cry of another pack, but these had a different cry, and they were coming towards his own pack. And he could see a clearing in the forest, a level field; and as his own pack was reaching the edge of the clearing, he saw a stag in front of the other pack. And towards the middle of the clearing, the pack that was chasing caught up with the stag and brought it to the ground.

Then Pwyll looked at the colour of the pack, without bothering to look at the stag. And of all the hounds he had seen in the world, he had never seen dogs of this colour––they were a gleaming shining white, and their ears were red. And as the whiteness of the dogs shone so did the redness of their ears. Then he came to the dogs, and drove away the pack that had killed the stag, and fed his own pack on it.

As he was feeding the dogs, he could see a rider coming after the pack on a large dapple-grey horse, with a hunting horn round his neck, and wearing hunting clothes of a light grey material. Then the rider came up to him, and spoke to him like this: ‘Sir,’ he said, ‘I know who you are, but I will not greet you.’

‘Well,’ said Pwyll, ‘perhaps your rank is such that you are not obliged to.’

‘Well,’ said Pwyll, ‘perhaps your rank is such that you are not obliged to.’

‘God knows,’ he said, ‘it’s not the level of my rank that prevents me.’

‘What else, sir?’ said Pwyll.

‘Between me and God,’ he said, ‘your own lack of manners and discourtesy.’

‘What discourtesy, sir, have you seen in me?’

‘I have seen no greater discourtesy in a man,’ he said, ‘than to drive away the pack that had killed the stag, and feed your own pack on it; that’, he said, ‘was discourtesy: and although I will not take revenge upon you, between me and God,’ he said, ‘I will bring shame upon you to the value of a hundred stags.’

‘Sir,’ said Pwyll, ‘if I have done wrong, I will redeem your friendship.’

‘How will you redeem it?’ he replied.

‘According to your rank, but I do not know who you are.’

‘I am a crowned king in the land that I come from.’

‘Lord,’ said Pwyll, ‘good day to you. And which land do you come from?’

‘From Annwfn,’ he replied. ‘I am Arawn, king of Annwfn.’

‘Lord,’ said Pwyll, ‘how shall I win your friendship?’

‘This is how,’ he replied. ‘A man whose territory is next to mine is forever fighting me. He is Hafgan, a king from Annwfn. By ridding me of that oppression––and you can do that easily––you will win my friendship.’

‘I will do that gladly,’ said Pwyll. ‘Tell me how I can do it.’

‘I will,’ he replied. ‘This is how: I will make a firm alliance with you. What I shall do is to put you in my place in Annwfn, and give you the most beautiful woman you have ever seen to sleep with you every night, and give you my face and form so that no chamberlain nor officer nor any other person who has ever served me shall know that you are not me. All this’, he said, ‘from tomorrow until the end of the year, and then we shall meet again in this place.’

‘Well and good,’ Pwyll replied, ‘but even if I am there until the end of the year, how will I find the man of whom you speak?’

‘A year from tonight,’ Arawn said, ‘there is a meeting between him and me at the ford. Be there in my shape,’ he said, ‘and you must give him only one blow––he will not survive it. And although he may ask you to give him another, you must not, however much he begs you. Because no matter how many more blows I gave him, the next day he was fighting against me as well as before.’

‘Well and good,’ said Pwyll, ‘but what shall I do with my realm?’

‘I shall arrange that no man or woman in your realm realizes that I am not you, and I will take your place,’ said Arawn.

‘Gladly,’ said Pwyll, ‘and I will go on my way.’

‘Your path will be smooth, and nothing will hinder you until you get to my land, and I will escort you.’

Arawn escorted Pwyll until he saw the court and dwelling-places.

‘There is the court and the realm under your authority,’ he said.

‘Make for the court; there is no one there who will not recognize you. And as you observe the service there, you will come to know the custom of the court.’

He made his way to the court. He saw sleeping quarters there and halls and rooms and the most beautifully adorned buildings that anyone had seen. And he went to the hall to take off his boots. Chamberlains and young lads came to remove his boots, and everyone greeted him as they arrived. Two knights came to remove his hunting clothes, and to dress him in a golden garment of brocaded silk. The hall was got ready. With that he could see a war-band and retinues coming in, and the fairest and best-equipped men that anyone had ever seen, and the queen with them, the most beautiful woman that anyone had seen, wearing a golden garment of shining brocaded silk. Then they went to wash, and went to the tables, and sat like this, the queen on his one side and the earl, he supposed, on the other. And he and the queen began to converse. As he conversed with her, he found her to be the most noble woman and the most gracious of disposition and discourse he had ever seen. They spent the time eating and drinking, singing and carousing. Of all the courts he had seen on earth, that was the court with the most food and drink and golden vessels and royal jewels. Time came for them to go to sleep, and they went to sleep, he and the queen. As soon as they got into bed, he turned his face to the edge of the bed, and his back to her. From then to the next day, he did not say a word to her. The next day there was tenderness and friendly conversation between them. Whatever affection existed between them during the day, not a single night until the end of the year was different from the first night.

He spent the year hunting and singing and carousing, and in friendship and conversation with companions until the night of the meeting. On that night the meeting was as well remembered by the inhabitant in the remotest part of the realm as it was by him. So he came to the meeting, accompanied by the noblemen of his realm. As soon as he came to the ford, a knight got up and spoke like this:

‘Noblemen,’ he said, ‘listen carefully. This confrontation is between the two kings, and between their two persons alone. Each one is making a claim against the other regarding land and territory; all of you should stand aside and leave the fighting between the two of them.’

With that the two kings approached each other towards the middle of the ford for the fight. And at the first attack, the man who was in Arawn’s place strikes Hafgan in the centre of the boss of his shield, so that it splits in half, and all his armour shatters, and Hafgan is thrown the length of his arm and spear-shaft over his horse’s crupper to the ground, suffering a fatal blow.

‘Lord,’ said Hafgan, ‘what right did you have to my death? I was claiming nothing from you. Nor do I know of any reason for you to kill me; but for God’s sake,’ he said, ‘since you have begun, then finish!’

‘Lord,’ said the other, ‘I may regret doing what I did to you. Find someone else who will kill you; I will not kill you.’

‘My faithful noblemen,’ said Hafgan, ‘take me away from here; my death is now certain. There is no way I can support you any longer.’

‘And my noblemen,’ said the man who was in Arawn’s place, ‘take advice and find out who should become vassals of mine.’

‘Lord,’ said the noblemen, ‘everyone should, for there is no king over the whole of Annwfn except you.’

‘Indeed,’ he said, ‘those who come submissively, it is right to receive them. Those who do not come willingly, we will force them by the power of the sword.’

Then he received the men’s allegiance, and began to take over the land. And by noon the following day both kingdoms were under his authority.

The Oxford World’s Classics edition of The Mabinogion is edited by Sioned Davies, Chair of Welsh at Cardiff University.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Flag of Wales. By ayzek, iStockPhoto.

The post The first branch of the Mabinogi appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOn ‘work ethic’Nine facts about athletics in Ancient GreeceKammerer, Carr, and an early Beat tragedy

Related StoriesOn ‘work ethic’Nine facts about athletics in Ancient GreeceKammerer, Carr, and an early Beat tragedy

Nine facts about athletics in Ancient Greece

The World Championships in Athletics takes place this month in Moscow. Since 1983 the championship has grown in size and now includes around 200 participating countries and territories, giving rise to the global prominence of athletics. The Ancient Greeks were some of the earliest to begin holding competitions around athletics, with each Greek state competing in a series of sporting events in the city of Olympia once every four years. J.C. McKeown unearths some amusing and surprising facts about the Greeks in A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities, including their sporting traditions.

In early times it was custom for athletes to compete with their clothes tucked up, but Coroebus ran naked when he won the short footrace at Olympia.

The sprint (two hundred meters) was the only competitive event in the first 13 Olympic Games.

If you place heavy weights on a plank of palm wood, pressing it until it can no longer bear the load, it does not give way downward, bending in a concave manner. Instead it rises up to counter the weight, with a convex curve. This is why, according to Plutarch, the palm has been chosen to represent victory in athletic competitions; the nature of the wood is such that it does not yield to pressure.

Athletes sometimes had their penis tied up to assist freedom of movement. The foreskin was pulled forward and tied up with a string called the cynodesme, which literally means “dog leash”.

A Chian was angry with his slave and said to him “I’m not going to send you to the mill, I’m going to take you to Olympia.” He apparently considered it a far more bitter punishment to be a spectator roasting in the rays of the sun, than to be put to work grinding flour in a mill.

A corpse was once pronounced victor. Arrhachion was wrestling in the final at Olympia. While his opponent was squeezing his neck, he broke one of his opponent’s toes. Arrhachion died of suffocation just as his opponent gave in because of the pain in his toe.

Marcus once ran in the race in armour. He was still running at midnight, and the stadium authorities locked up because he was one of the stone statues. When they opened up again, he had finished the first lap.

When a humble and inferior boxer is matched against a famous opponent who has never been defeated, the spectators immediately side with the weaker figure, shouting encouragement to him and punching when he does.

Euripides competed as a boxer at the Isthmian and Nemean Games, and was crowned as victor.

J.C. McKeown is Professor of Classics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, co-editor of the Oxford Anthology of Roman Literature, and author of Classical Latin: An Introductory Course and A Cabinet of Roman Curiosities. He is the author of A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities published by OUP in July 2013.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles via email or RSS.

Image credit: Mosaic floor depicting various athletes wearing wreaths. From the Museum of Olympia. Photo by Tkoletsis. Creative commons license via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Nine facts about athletics in Ancient Greece appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesNine curiosities about Ancient Greek dramaWonga-bashing won’t save the Church of EnglandThe mysteries of Pope Francis

Related StoriesNine curiosities about Ancient Greek dramaWonga-bashing won’t save the Church of EnglandThe mysteries of Pope Francis

Wonga-bashing won’t save the Church of England

By Linda Woodhead

We are living through a very significant historical change: the collapse of the historic churches which have shaped British society and culture. The Church of England, by law established, is no exception. A survey I recently carried out with YouGov for the Westminster Faith Debates (June 2013) shows tha in Great Britain as a whole only 11% of young people in their twenties now call themselves CofE or Anglican, compared to nearer half of over-70s. The challenge facing the new Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, is to address this decline. But the initial indications suggest he may be heading in the wrong direction.

Consider the Archbishop’s recent criticisms of Wonga and other payday loan providers. Most commentators were positive. Welby braved the revelation that the Church had a small investment in Wonga, took advantage of the media coverage, and managed to highlight an important issue. This is remarkable given that he didn’t have any serious initiative to announce for the Church doesn’t have the wherewithal to set up the credit unions of which he spoke so favourably. Here, it seems, is a churchman with something to say, the ability to say it in a comprehensible fashion, and the courage to stand up for social justice. So what’s the problem?

Consider the Archbishop’s recent criticisms of Wonga and other payday loan providers. Most commentators were positive. Welby braved the revelation that the Church had a small investment in Wonga, took advantage of the media coverage, and managed to highlight an important issue. This is remarkable given that he didn’t have any serious initiative to announce for the Church doesn’t have the wherewithal to set up the credit unions of which he spoke so favourably. Here, it seems, is a churchman with something to say, the ability to say it in a comprehensible fashion, and the courage to stand up for social justice. So what’s the problem?

Providing care for the poorest in society was, historically, part of the Church’s business. In the mid-twentieth century it happily joined forces with the state to nationalise this work. When the Thatcher government started to challenge the welfare consensus, the Church of England was quick to leap to the defence of the poor. Its 1985 report Faith in the City greatly irritated Mrs Thatcher, just as Mrs Thatcher’s ‘Sermon on the Mound’ greatly irritated the clergy.

I was near the heart of all this, straight out of university to my first job teaching in an Anglican theological college (seminary). In the wake of Faith in the City it had been decreed that the students should be bundled off to “urban priority areas” to “get alongside the poor,” and win their clerical spurs. Despite good intentions, I found the whole thing patronising and economically naïve. Quite a lot of “the poor” didn’t seem to want to be got alongside. There was also a very obvious set of gender biases; the ideas were still of male clergy supporting working-class men. And the underpinning thinking was long on wealth distribution, short on wealth creation.

Fast forward to the last Archbishop, Rowan Williams, a self-confessed “beardy leftie.” Under his benevolent rule, the Church’s focus on the poor and social justice remained remarkably similar to that of the 1980s, despite the fact that the category of “the poor” had by this time become highly problematic. So when Rowan William’s successor immediately turned his attention to ‘the poorest in society’, I heard the same old record going round.

The stuck-ness is concerning. What’s worse is that this set of priorities is now strikingly out of step with the views of a majority of Anglicans, not to mention a majority of the British people. My YouGov poll finds that, even after correcting for age, most Anglicans fall on the ‘free market’ (in favour of individual enterprise) rather than the ‘social welfare’ (in favour of welfare and state interventions) side of the political-values scale. Indeed, Anglicans are more tilted in that direction than the general population of the UK, even though the latter is also tilted towards ‘free market’ values. For example, just under half of all Anglicans, churchgoing or not, think that Mrs Thatcher did more good for Britain than Tony Blair, compared with 38% of the general population (16% of Anglicans think Tony Blair did more good, compared with 18% of the general population). And nearly 70% of Anglicans believe that the welfare system has created a culture of dependency, which is almost 10 percentage points more than the general population.

The stuck-ness is concerning. What’s worse is that this set of priorities is now strikingly out of step with the views of a majority of Anglicans, not to mention a majority of the British people. My YouGov poll finds that, even after correcting for age, most Anglicans fall on the ‘free market’ (in favour of individual enterprise) rather than the ‘social welfare’ (in favour of welfare and state interventions) side of the political-values scale. Indeed, Anglicans are more tilted in that direction than the general population of the UK, even though the latter is also tilted towards ‘free market’ values. For example, just under half of all Anglicans, churchgoing or not, think that Mrs Thatcher did more good for Britain than Tony Blair, compared with 38% of the general population (16% of Anglicans think Tony Blair did more good, compared with 18% of the general population). And nearly 70% of Anglicans believe that the welfare system has created a culture of dependency, which is almost 10 percentage points more than the general population.

But the real killer for the Church of England is that most people, including most Anglicans, are also out of step with official teaching on other issues of justice and fairness — most notably the Church’s policies towards women and gay people. To give him his due, the new Archbishop has spoken strongly in favour of women bishops. But one of his earliest contributions to public life, even before Wonga, was to speak out strongly in the House of Lords against the legislation to allow gay marriage. Although he claimed that a majority of Anglicans are strongly opposed to this change, our poll shows that, on the contrary, Anglicans are now in favour of the proposed legislation by a small margin — as is the country as a whole, including most overwhelmingly younger people. My survey asked under-25s with negative views about the church why they held those views. Not surprisingly, the most common answer was: “The Church of England is too prejudiced – it discriminates against women and gay people.”

The problem which Justin Welby has to face is that you can’t claim to be pro justice for some – “the poor” – but not others – women and gay people. And since personal morality is the church’s core business in a way welfare provision is not, those who still know their Bible may find a verse from Matthew springing to mind: “Why beholdest thou the mote that is in thy brother’s eye, but considerest not the beam that is in thine own eye?”

Linda Woodhead is Professor of Sociology of Religion at Lancaster University. She co-organises the Westminster Faith Debates (for public debate on religion), which are funded by the ESRC and AHRC, and which supported the YouGov poll cited here. She is the author of Christianity: A Very Short Introduction. Follow @LindaWoodhead on Twitter.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Photograph of Payday Loans shop, by Seth Anderson; CC-BY-SA 2.0 License via Flickr. (2) Photograph of Justin Welby, by Catholic Church (England and Wales); CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 License via Flickr.

The post Wonga-bashing won’t save the Church of England appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesKammerer, Carr, and an early Beat tragedyWhat have we learned from modern wars?The mysteries of Pope Francis

Related StoriesKammerer, Carr, and an early Beat tragedyWhat have we learned from modern wars?The mysteries of Pope Francis

August 1, 2013

The origins of the Fulbright program

Since its creation in the summer of 1946, the Fulbright program has become the “flagship international educational exchange program” of the US government. Over the past 67 years, almost 320,000 students, scholars and teachers have traveled internationally as part of the program’s vast effort to improve mutual understanding between nations. Understandably, given the profound effect these experiences have had on the lives of grant recipients, the Fulbright is often seen as among the most liberal, generous, and benevolent international programs of the US state. Historian Arnold Toynbee spoke for many when he praised the program as “one of the really generous and imaginative things that have been done in the world since World War II.” But the origins of the Fulbright program suggest a rather different story — less heart-warming, but more interesting.

To begin with, the United States didn’t have to pay for the early Fulbright exchanges. Rather, foreign nations footed the bill. How did the United States pull this off? Surprisingly, it did so by taking advantage of its uniquely prosperous and productive economy in the waning stages of World War II. When the war came to an end, US military supply lines criss-crossed the world, and millions of different types of military material were scattered across the globe — trucks, tanks, food, tents, uniforms, radios. The US government at first thought the material was worthless because it was difficult to transport and guard, it was deteriorating in the elements, and war-ravaged foreign nations couldn’t afford to purchase it.

To begin with, the United States didn’t have to pay for the early Fulbright exchanges. Rather, foreign nations footed the bill. How did the United States pull this off? Surprisingly, it did so by taking advantage of its uniquely prosperous and productive economy in the waning stages of World War II. When the war came to an end, US military supply lines criss-crossed the world, and millions of different types of military material were scattered across the globe — trucks, tanks, food, tents, uniforms, radios. The US government at first thought the material was worthless because it was difficult to transport and guard, it was deteriorating in the elements, and war-ravaged foreign nations couldn’t afford to purchase it.

But rather than abandon this surplus military material, government administrators decided they could trade it to foreign nations in exchange for what they called ‘intangible benefits’ — treaty concessions, embassy lands, and, importantly, the funding of educational exchange programs. What we think of as the ‘Fulbright bill’ was actually an amendment to the Surplus Property Act of 1944, allowing the State Department to make these kinds of trades. So the funding of the Fulbright program was less an act of American generosity than what one contemporary commentator called “an ingenious piece of higher mathematics…[that] found a way to finance out of the sale of war junk a world wide system of American scholarships.” Rotting food and rusting trucks, not the largesse of the American government, created the Fulbright program. As one congressman noted approvingly in 1946, the Fulbright program “does not cost us a cent.”

If the economics of the Fulbright served American interests, early administrators of the program also assumed that educational exchange would redound to the benefit of America. These administrators thought that the experience of living and studying in America would have a profound impact on foreigners. In fact, they were worried that younger students might become so enamored of America that they would return home as “misfits unable to readjust to their native cultures.” Fulbright grants were therefore limited to presumably more mature and level-headed graduate students. Still, the experience of studying in America was supposed to convert foreigners to the American way of life. Senator J. William Fulbright, for instance, praised a Columbia-educated Turkish politician because “his mind is like a channel, open and sympathetic” through which American ideas could be transmitted to the people of Turkey. In a similarly revealing flight of rhetorical fancy, Fulbright also imagined “what a fine thing it would be if Mr. Stalin or Mr Molotov could have gone…to Columbia College in their youth.” Advocates of cultural exchange were so confident in the power of the American experience that even a young Stalin would have become a convert.

There was little worry, on the other hand, that American students and scholars going abroad would become seduced by foreign ways of life. Rather, upon their return home American Fulbrighters were expected to become a national asset, familiar with foreign nations and peoples. And they would return, as one administrator put it, “with a deeper appreciation of our own institutions and our way of life.” Like Dorothy, Americans would travel far only to find that there truly was no place like home.

The Fulbright program, in other words, was underpinned by a contradictory understanding of educational exchange. While foreigners in the United States would absorb American culture, Americans abroad would spread American culture. There was no coherent model of acculturation or cultural exchange underpinning the program. Rather, the apparent contradiction was resolved by administrators’ unspoken faith in the power of American culture to transform the world without itself being transformed. Beneath the rhetoric of “mutual exchange and understanding” the cultural exchanges of the Fulbright program were expected to be one-way streets.

Of course, educational exchange wouldn’t end up working exactly as these administrators imagined. Individual students, scholars, and teachers have had a multitude of different experiences while funded by the program — experiences that were far more complex, varied, and interesting. And with the rise of the Cold War propaganda struggle with the USSR, the American state would begin to fund an expanded Fulbright program directly.

Still, the expectations of early Fulbright administrators are important, because their nationalist assumptions remind us that the program was created in a moment of supreme American self-confidence. For all the good the program has done in the world, it was intended to serve very particular American interests in the late 1940s: to dispose of surplus military material as profitably as possible, and to facilitate the spread of American culture. We can only hope that the program will survive the current moment of national uncertainty and fiscal belt-tightening. Then, perhaps, we might be able to start talking about acts of generosity.

Sam Lebovic is an Assistant Professor of History at George Mason University. He is the author of “From War Junk to Educational Exchange: The World War II Origins of the Fulbright Program and the Foundations of American Cultural Globalism, 1945–50” in Diplomatic History, which is available to read for free for a limited time. He is currently completing his first book, a history of American press freedom from the rise of the modern First Amendment in 1919 until the crises of Watergate and the Pentagon Papers.

As the principal journal devoted to the history of U.S. diplomacy, foreign relations, and security issues, Diplomatic History examines issues from the colonial period to the present in a global and comparative context. The journal offers a variety of perspectives on the economic, strategic, cultural, racial, and ideological aspects of the United States in the world.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS..

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Newcomer in the city. © Razvan via iStockphoto.

The post The origins of the Fulbright program appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhere’s Mrs Y? The effects of unnecessary ward movesWorld Hepatitis Day 2013: This is hepatitis. Know it. Confront it.On ‘work ethic’

Related StoriesWhere’s Mrs Y? The effects of unnecessary ward movesWorld Hepatitis Day 2013: This is hepatitis. Know it. Confront it.On ‘work ethic’

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers