Oxford University Press's Blog, page 921

July 24, 2013

Alphabet soup, part 1: V and Z

It is common knowledge that an average page of an English dictionary contains at least twice as many borrowed as native words, even though come, go, see, sit, stand, do, make, man, woman, in, on, and other similar heavy duty words go back to Old English. But anyone who has the knack for reading dictionaries page after page (a rare knack, I must admit) will be surprised to learn that practically all English words beginning with the letters v and z are of foreign descent. This person will notice that in Dutch and German v- and z-words fill up dozens of columns, while in English, the virtues of zeal and the stripes of zebras notwithstanding, such columns are few. Very, vogue, virgin, voucher, vomit—wherever we look, the answer is always the same: from French (mainly), Latin, or Italian, as the case may be. What is the reason for that? What has happened to the native stock? Before going on, a term has to be introduced. The consonants f, s and th (as in Engl. thigh) and their voiced counterparts (v, z, and th, as in Engl. thy) are called spirants.

Long ago, while answering someone’s question, I briefly touched on the nature of this phenomenon, but, since even I don’t remember the context, it will be safe to assume that no one else does. Therefore, I will proceed. In Old English, the sounds v and z occurred only between vowels. Thus, lufu and risan (Modern Engl. love and rise) were pronounced approximately as luvu and reezan. In present day English, those voiced spirants can still be found in the place in which they stood a thousand years ago. Why then are there so many v- and z- words in Dutch and German and nearly none in English? German is an easy case. Both letters deceive the outsider because they designate the sounds of f and ts respectively. Vater means “father” and in pronunciation begins with f, while z (for instance, in the familiar Zeitgeist “spirit of the time”) is the ts of Engl. tsetse and cats. For the spirant v- German has the letter w-, as in wann “when” and wo “where.” But in Dutch initial v and z designate “real” v and z.

In all the Germanic languages, spirants were swept by a slow-moving but inexorable wave of voicing. We will disregard its remote causes and concentrate on its effects. This sound change perhaps resembles more a stone rolling downhill than a wave. The “stone” was pushed about two millennia ago. In the oldest texts we can still observe f, s, and th (voiceless) alternating under certain conditions with v, z, and th (voiced) and their reflexes (continuations). Later, voicing affected the spirants that escaped the first round, and that is when risan and lufu became “reezan” and “luvu” (at the dawn of their history, they were pronounced with -f- and -s-). Finally, the “stone” dragged down initial consonants. It is not improbable that the odd spelling of German Vater and its likes reflects the occasional old pronunciation with v-. The situation with v-, but initial s- became z- in all German words. See “sea; lake” and so forth are only spelled with an s (consequently, the letter z could be used for another purpose). In Dutch, both f- and s- participated in the process, and, contrary to German, Dutch spelling reflects the change. That is why there are so many v- and z- words in Dutch.

Nor did English get out of the way of the rolling stone, but the change was local and limited to Kent and a few southwestern dialects. Modern English owes a few of its phonetic features to Kent, partly because Chaucer, though a native of London, lived there for a while and retained some “kentisms” in his speech. After these preliminaries, we can return to the V-section of English dictionaries. Although French dominates it, the other sources need not be disregarded. A few insignificant v-words are of Scandinavian origin: Valkyrie (literally “corpse chooser”), Varangian, and Viking should be mentioned. Vodka is, alas, from Russian and is usually explained in an unconvincing way: allegedly, it contains the root of Russian voda “water” and a diminutive suffix. Voda does mean “water,” but the suffix poses problems: in this word, it is not diminutive, for vodka cannot be understood as “little water.” Not unexpectedly, now that we know what happened to initial f in Dutch, a few v-words came to English from that language. However, they are special terms and little known: veer “allow to drift further; pay out a cable, etc.” (distinct from veer “change course,” which is from French) and vang “rope for steadying the gaffs of a sail.” Vang is related to German fangen “to catch.” The English name of such a rope is painter, a noun of doubtful origin; those who do not know it are advised to reread the first chapter of The Wind in the Willows. We can pass by Volapük ~ Volapuk and a few other exotic items embellishing the V-section.

However, there is a short list of native v-words: van “winning basket or shovel; wing (common in Romantic poetry); sail of a windmill,” vane (as in weathervane), vat, and vixen. It is instructive to trace their etymology. Vixen is a counterpart of German Füchsin “she-fox,” minus umlaut and with “southern voicing,” which makes its connection with fox impossible for a modern English-speaker to recognize. Vat also has a German cognate, namely Fass “vessel.” The story of van is less transparent. It is an etymological doublet of fan, so presumably, a southern form, but Old Engl. fann was a borrowing of Latin vannus. The speakers of Old English could not pronounce initial v; hence f-. Old French also had van, a reflex of Latin vannus. The existence of that word might influence the Middle English one. It cannot be deiced whether the interplay of native dialectal voicing and the French analog played a role in the history of Engl. van.

In Middle English, final vowels were lost. Lufu became love (two syllables: lo-ve) and still later a monosyllable. The final spirant was not devoiced, and the English learned to pronounce v not only between vowels. Once that happened, French words like very (from Middle Engl. verray) no longer caused them any trouble. It is rather unlikely that Londoners would have been able to articulate initial v without forms like lov “love” (noun).

After such an explanation the history of Engl. z- comes like an anticlimax. Zenith, zymosis, and the rest are so unmistakably foreign. Still one runs into zinc (from German), zounds (a contraction of His wounds), zip (probably onomatopoeic), and zigzag (Germanic). In the dialects in which initial f became v, s- also yielded z-. Edgar (King Lear), while feigning madness, says zir for sir. But no word of this type entered the Standard. This is one of the reasons the Z-part of an English dictionary looks so sparse.

Does the stone of sound change ever stop rolling downhill? It probably does, assuming that it can eventually strike bottom and hit all its potential victims.  Much later than the events described above voicing affected the beginning of short, mainly unstressed, words, such as the, this, that, there, then, and thy (all of which once had the th- of thorn and thick) and the end of is, was, as, and has, the latter being a relatively modern replacement of hath, and of. The future will show whether there is still something left for the voicing of spirants to do. Historical phonetics keeps us in permanent suspense.

Much later than the events described above voicing affected the beginning of short, mainly unstressed, words, such as the, this, that, there, then, and thy (all of which once had the th- of thorn and thick) and the end of is, was, as, and has, the latter being a relatively modern replacement of hath, and of. The future will show whether there is still something left for the voicing of spirants to do. Historical phonetics keeps us in permanent suspense.

The picture gracing this post is an illustration to Pushkin’s fairy tale The Golden Cockerel (and there is an opera by Rimsky-Korsakov, his last one, known in the West as Le coq d’or, on this plot). Now that in our prudish parlance cock has yielded to rooster, weather cock has become weathervane, but it was indeed a cock, the same we still see on many houses, even though not made of pure gold. However, in the story of initial v-, vane did its work well.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Book cover by Willy Pogany for The Golden Cockerel: From the Original Russian Fairy Tale of Alexander Pushkin by Elaine Pogany via Barnes & Noble.

The post Alphabet soup, part 1: V and Z appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMonthly etymological gleanings for June 2013How courteous are you at court?Flutes and flatterers

Related StoriesMonthly etymological gleanings for June 2013How courteous are you at court?Flutes and flatterers

The misfortune of Athos

We wish a happy birthday to Alexandre Dumas today with the musketeers. In the 1620s at the court of Louis XIII, Athos, Porthos, and Aramis with their companion, the headstrong d’Artagnan, are engaged in a battle against Richelieu, the King’s minister, and the beautiful, unscrupulous spy, Milady. Behind the flashing blades and bravura, Dumas explores the eternal conflict between good and evil. The following is an excerpt from Chapter 27, “The Wife of Athos.”

‘Now we must obtain some intelligence of Athos,’ said d’Artagnan to the joyous Aramis, after he had told him everything that had happened since their departure from Paris, and after an excellent dinner had made the one forget his thesis, and the other his fatigue.

‘Do you believe, then, that any misfortune has befallen him?’ demanded Aramis. ‘Athos is so cool, so brave, and wields his sword so skilfully!’

‘Yes, doubtless, and no one knows better than I do the courage and address of Athos. But I like better the shock of lances on my sword than the blows of sticks; and I fear that Athos may have been beaten by the rabble, who hit hard, and do not leave off quickly. It is, I confess, on this account that I should like to set out as soon as possible.’

‘I will endeavour to accompany you,’ said Aramis, although I am scarcely in a fit state to mount a horse. Yesterday, I used the discipline, which you see on the wall; but the pain made me give up that pious exercise.’

‘My dear friend, none ever heard of endeavouring to cure the wounds of a carbine by the strokes of a cat-o’-nine-tails. But you were ill; and, as illness makes the head light, I excuse you.’

‘And when shall you set out?’

‘Tomorrow, at break of day. Rest as well as you can to-night, and to-morrow, if you are able, we will go together.’

‘Farewell, then, till to-morrow,’ said Aramis; ‘for, iron as you are, you must surely want some rest.’

When d’Artagnan entered Aramis’s room, the next morning, he found him looking out of the window.

‘What are you looking at?’ said he.

‘Faith, I am admiring those three magnificent horses which the stable-boys are holding: it is a princely pleasure to travel on such animals.’

‘Well, then, my dear Aramis, you will give yourself that pleasure, for one of those horses belongs to you.’

‘Nonsense! and which!’

‘Whichever you like, for I have no preference.’

‘and the rich caparison which covers him – is that, also, mine?’

‘Certainly.’

‘You are laughing at me, d’Artagnan.’

‘I have left off laughing since you began to speak French again.’

‘And are those gilded holsters, that velvet housing, and that saddle, studded with silver, mine?’

‘Yours! Just as that horse which steps so proudly is mine; and that other one which caracoles so bravely, is for Athos.’

‘I ‘faith, they are superb animals.’

‘I am glad that they suit your taste.’

‘Is it the king, then, who has made you this present?’

‘You may be quite sure that it was not cardinal: but do not disturb yourself as to whence they came, only be satisfied that one of them is your own.’

‘I choose the one that the red-haired valet is holding.’

‘Well chosen.’

‘Thank God!’ cried Aramis, ‘this drives away the last remnant of my pain. I would mount such a horse with thirty bullets in my body. Ah! upon my soul, what superb stirrups. Hallo! Bazin, come here this instant.’

Bazin appeared, silent and melancholy, at the door.

‘Polish up my sword, smarten my hat, brush my cloak, and load my pistols!’ said Aramis.

‘The last order is unnecessary,’ said d’Artagnan, ‘for there are loaded pistols in your holsters.’

Bazin sighed deeply.

‘Come, Master Bazin, console yourself,’ said d’Artagnan; ‘the kingdom of heaven may be gained in any condition of life.’

‘But he was already such a good theologian,’ said Bazin, almost in tears; ‘he would have become a bishop – perhaps even a cardinal.’

‘Well! my poor Bazin, let us see, and reflect a little. What is the use of being a churchman, pray? You do not by that means avoid going to war; for you see that the cardinal is about to make his first campaign with a head-piece on, and a halbert in his hand; and M. de Nearest de la Valette, what do you say to him? He is a cardinal too, and ask his lackey how often he had made lint for him.’

‘Alas!’ sighed Bazin, ‘I know it, sir. The whole world is turned topsy turvey, nowadays.’

Alexandre Dumas was a French novelist, dramatist, and pioneer of the romantic theatre. The Three Musketeers (1844) is one of the world’s greatest historical adventure stories. Its heroes have become symbols for the spirit of youth, daring, and comradeship. The Oxford World’s Classics edition is edited by David Coward, Emeritus Professor of French Literature, University of Leeds.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics onTwitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: A Game of Piquet by Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier, 1881. National Museum of Wales. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The misfortune of Athos appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Poetic Edda and Wagner’s Ring CycleGimme Shelter: De Quincey on DrugsHappy Birthday, Topsy

Related StoriesThe Poetic Edda and Wagner’s Ring CycleGimme Shelter: De Quincey on DrugsHappy Birthday, Topsy

Of Mormonish and Saintspeak

In the beginning, Mormonism was a cult. Not in the vulgar sense often attributed to feared or misconstrued religious minorities, but in the way that earliest Christianity or nascent Islam was a cult: a group that forms around a charismatic figure coupled with radical new religious claims. Like these predecessors, Mormonism has long since grown from cult to culture. This is reflected in its fertile, distinctive parlance–by turns revealing, quaint, ingenious, paradoxical, and humorous.

The Salt Lake Temple, the sixth temple built by the LDS church overall, and the fourth operating temple. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

The term Mormon, referring to a church member, has an uneven acceptance among the faithful. It is a shortened form of Mormonite, an 1830s appellation assigned by critics to early believers in The Book of Mormon. Just as early converts to “the Society of Friends” were by outsiders labeled “Quakers” after their sometimes demonstrative practice of shaking with the spirit during worship, so adherents of the newly founded “Church of Christ” were called after Mormon, the purported ancient editor of their new scriptural book, which believers took to complement the Bible. Some Mormons prefer Saints, which is what first-century Christians called themselves, or Latter-day Saints (“LDS”), deriving from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: the church’s cumbersome official title since 1838. But these days many believers happily accept the sobriquet “Mormon”; it remains in wide use and did not, after all, seem to offend founding prophet Joseph Smith during his lifetime.

What the tight-knit Mormons call themselves and others engenders jokes. One old joke is that whenever a Jew arrives in Utah he says: “This is the only place in the world where I am seen as a gentile.” The humor turns on Mormon self-identity as heirs both of ancient Israel and of a restored original Christianity. Hence, traditionally, Mormons are Saints and outsiders are gentiles. The quip draws laughter among Mormons, Jews, and others, although in actuality Mormons have never thought of Jews as gentiles.

Moreover, Mormon nomenclature evolves. The prominent Methodist scholar, Jan Shipps, has made her career studying the Saints for more than a half-century. When she began in the 1960s, she became affectionately known among her subjects as the “gentile Mormon watcher.” As Mormonism grew and became less tribal, “gentile” faded from its vocabulary and Shipps became a non-Mormon. Subsequently, she reports, she was referred to as a non-member, perhaps a bureaucratic inflection of the Correlation movement in a religion working to retain firm organizational control of its diverse programs, curriculum, finances, and liturgy amidst dramatic international growth in the second half of the 20th century. At last Dr. Shipps became simply a Methodist scholar of Mormonism–all this change in labels without her altering her stance or private affiliation!

When humans name each other, or their institutions and possessions, they reveal something of their backgrounds, perspectives, whimsies, tastes, aspirations, fears, and beliefs. This is evident in the names of Mormon places, which harbor stories and thus are “place tales.” The Mormon toponymy may be traced from the movement’s antebellum origins in western New York through its sojourn in the Midwest and its forced exodus across the plains to the Rocky Mountains. The serene woods where Joseph Smith had his earliest vision in 1820 in present-day Palmyra, New York, is now, to Mormons, the Sacred Grove. A nearby hill in which Smith reported discovering the gold plates, whose translation became the Book of Mormon, is called after its Book of Mormon name, Cumorah. Despite the violent Mormon exile from Nauvoo, Illinois, after 1846, the town retains the name bequeathed to it by Joseph Smith when his followers gathered there in 1839; Smith explained the name as Hebrew for a “beautiful place.” In Iowa, Lamoni (after a king) and Zarahemla (a figure, city, and land) derive from the Book of Mormon. Western states contiguous to Utah are dotted with Mormon placenames: Joseph City, Mormon Lake, and Mormon Mountain in Arizona, for example. In Utah proper the names are myriad: Orderville, after the United Order in which 19th-century disciples enacted a communal economic system urged by church leaders; Brigham City, after Mormonism’s great presiding colonizer, Brigham Young; tiny Veyo, from a Mormon acronym for Virtue, Enterprise, Youth, and Order; and the Jordan River, named when Mormon pioneers discovered that the climate and terrain of their new homeland in the western desert resembled “Palestine inverted,” complete with a large dead sea (the Great Salt Lake) that was connected by a narrow river to a smaller fresh Galilee (Utah Lake) to the south.

Perhaps the two most common Mormon placenames in the state are Zion and Deseret. Originally among the aspiring Mormons, Zion suggested the “New Israel” where service and cooperation, rather than profit, drove the economy and its society. There “the pure in heart” were to dwell with such harmony that there would be “no poor among them.” Today Zion ironically attaches as much to commercial as to religious affairs: banks, rare coin dealerships, energy companies, insurance agencies, real estate corporations, and numerous others are called after this name.

“Deseret” is the Book of Mormon name for “honeybee”–denoting industry and connoting organization, prized Mormon virtues. Mormon leaders in the 19th century repeatedly proposed that the vast territory they called Deseret be granted statehood, though the federal Congress, wishing to limit Mormon power, spurned the name, instead designating the territory and later the state after a native tribe, the Utes. But the symbol and concept of Deseret infuse Mormon culture. A beehive beneath the word “Industry” comprises the center of the Utah state flag. The dominant religious bookstore chain in the state is the church-owned Deseret Book Co.; Deseret First Credit Union is a prominent financial institution; one of Salt Lake City’s two major newspapers is the church’s Deseret News; Deseret Industries thrift stores is a division of Mormonism’s vast and impressive Welfare Services enterprise which displaces nationally-known Good Will Industries in places where Mormons are numerous.

In Mormon popular culture, anywhere outside of Utah and vicinity is the missionfield. Elders are commonly 18-year-old men. And virtually all members of a ward (congregation) have a calling or responsibility. This arguably produces more presidents per square mile than any other organization in existence, for a half-dozen Saints preside over various aspects of their respective wards.

All this grants us the briefest glimpse at Mormonism’s rich and colorful culture. Doubtless a substantive book could be written on Mormon vernacular.

Philip L. Barlow is Arrington Chair of Mormon History and Culture at Utah State University. His books include the updated edition of Mormons and the Bible (2013), The Oxford Handbook to Mormonism (co-edited with Terryl Givens, forthcoming, 2013), The New Historical Atlas of Religion in America (2000, co-authored with Edwin Scott Gaustad) and, as co-editor with Mark Silk, Religion and Public Life in the Midwest: America’s Common Denominator? (2004). He is past president of the Mormon History Association.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Of Mormonish and Saintspeak appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOn ‘work ethic’Why should we care about the Septuagint?A bit of a virtual vade mecum

Related StoriesOn ‘work ethic’Why should we care about the Septuagint?A bit of a virtual vade mecum

A bit of a virtual vade mecum

Surveying recent scholarship, one could be forgiven to think that “international investment law” is a fad. Articles suggest that, like vuvuzelas at football games, “investment law” made a rather noisy entrance, annoyed the majority of onlookers, and destroyed the integrity and purity of a centuries’ long tradition. Many suggest that it would soon be abandoned and treated as an interesting but formidable mistake. Why, then, how should one study international arbitral decisions applying investment protection treaties?

Arbitral proceedings between host states and foreign investors show no sign of abating. Of 419 total cases registered by the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes or ICSID (the main arbitral body administering investor-state arbitrations since 1972), 50 were registered in 2012. This exceeds the prior record years’ for new case activity by about a third. According to some accounts, the claim value of investor-state disputes nears the GDP of Switzerland. In all of these new cases, it would be unthinkable to argue a point without reference to earlier awards and decisions. One reason to study arbitral decisions, therefore, is to be an effective advocate in investor-state proceedings. For the more academically minded, studying investor-state decisions (and their reliance on prior decisions) will permit one to understand the rules of decisions employed by investor-state tribunals. A systematic collection of investor-state decisions is an inevitable tool to act within and speak about a burgeoning field of international law.

Angel Gurría, OECD Secretary-General, gives the opening speech at the Global Angel Gurría, OECD Secretary-General, gives the opening speech at the Global Forum VIII on International Investment. Photo by Hervé Cortinat/OECD, CC BY 2.1, via Flickr.

This pragmatic answer is superficial. Some commentators have warned that tribunals frequently come to facially inconsistent decisions. It can lead one to opine that this inconsistency threatens the predictable application of investment protection treaties. Such an opinion would focus almost exclusively on the result reached by investor-state tribunals. Rather than understanding decisions as an organic outgrowth of the dispute resolution process — the record and arguments presented by the parties — one would exclusively read and rely upon decontextualized snippets of holdings and treat them like the aphoristic disembodied wisdom of a distant sage.

In truth, investor-state arbitral decisions have relevance for an entirely different reason. For instance, the body of jurisdictional decisions by investor-state tribunals perfectly exemplifies the process and principle of access to justice at international law. The International Court of Justice developed a balancing test that “there is no burden of proof to be discharged in the matter of jurisdiction” but that a tribunal instead must determine from the record “whether the force of the arguments militating in favour of jurisdiction is preponderant.” This process gives pride of place to the context of decision — the record and the submission of the parties ignored by the superficial engagement of investor-state decisions. It also captures the international law principle of access to justice. It bridges the competing considerations that (a) exercising of jurisdiction is the sole means of access to justice against the respondent state and (b) that the respondent has limited its submission to international jurisdiction by the terms of the consent instrument. Digesting investor-state jurisdictional decisions in their entirety (including the arguments presented by the parties) provides a systemic map of the uniquely complex international law process of jurisdictional decision as actually applied.

Investor-state awards similarly transcend a shallow exercise in quotation and glossing the holding of particular cases. They are building blocks of a coalescing international common law, grown from an evolving understanding of common problems, such as the meaning of a certain non-precluded measures clause in a US bilateral investment treaty. Internationa law did not develop around pithy quotes lifted from earlier awards. The parties provide alternative accounts and different potential solutions in each new case involving the same language to be interpreted (for instance, the WTO interpretation of said non-precluded measures clause was only pled by Argentina one of the latest proceedings). None of these solutions is ever final. Rather, investor-state awards provide hypotheses to be tested by different, rival considerations not previously expressed. This process of problem solving is relevant beyond investor-state arbitration in any international legal proceeding.

A principled approach is needed to navigate the complex maze of international law decisions. Studying international arbitral decisions provides key insights into international law by unveiling how it operates.

Frédéric G. Sourgens is an Associate Professor of Law at Washburn University School of Law. He is a contributor to Investment Claims, an online law resource from Oxford University Press.

Investment Claims is a regularly updated collection of materials and analysis used for research in international investment law and arbitration. Described as an invaluable resource by its users, Investment Claims contains fully searchable arbitration awards and decisions, bilateral investment treaties, multilateral treaties, journal articles, monographs, arbitration laws, and much more, all linked and cross-referenced via the Oxford Law Citator.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS

The post A bit of a virtual vade mecum appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesUnderstanding history through biographyUnderstanding history through biography - EnclosureMyths about rape myths

Related StoriesUnderstanding history through biographyUnderstanding history through biography - EnclosureMyths about rape myths

July 23, 2013

On ‘work ethic’

The expression is somehow on everybody’s lips. Its incidence in the media has risen steadily over the last decade or so, and now an attentive reader of the broadsheets is likely to encounter it every day. It’s most often found on the sports pages: one recent 48-hour period registered online praise for the respective work ethics of the footballer Nicolas Anelka, the cricketer Peter Siddle, the tennis player Marion Bartoli, and the British Lions rugby team.

Linguistically, this is rather surprising. The concept of an ethic – a theoretically identifiable system of moral assumptions – is, you could say, metadiscursive: the word doesn’t speak about what is good, it speaks about a way in which people speak about what is good. This makes it useful to sociologists, but you would hardly expect to find it serving the immediate purposes of football managers. How has it vaulted the academic fence and got into the mainstream?

Everyone agrees that it comes originally from Max Weber’s classic study The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, published in Germany in 1905 and in English translation in 1930. And indeed the earliest English entry for ‘work ethic’ in the current OED is from a 1959 article by a historian who was using it to refer explicitly to Weber’s theory. However, it turns out to be one of those pseudo-quotations, like ‘Elementary, my dear Watson’ or ‘Play it again, Sam’, which are very famous but can’t be found in the text they supposedly come from. Although Weber certainly argued that Protestant teaching attached a special value to hard work, the expression ‘work ethic’ appears nowhere in his book. It isn’t what he said, quite. It’s the sound-bite version of what he said.

The ‘ethic’ Weber described is a complicated mixture of spiritual and practical imperatives, embracing ideas of self-government, the suppression of natural impulses, the search for marks of divine grace, and the purposive ordering of a person’s whole life. It is distinctively Protestant in the sense that it took the ascetic discipline of the monastic tradition and tried to rewrite it for life in the world. It was also, according to Weber, the victim of a historical irony: these particular virtues, promoted for religious reasons, were often conducive to making a great deal of money, and so bringing about conditions of luxury and leisure that threatened to undermine the virtues themselves. In other words, what Weber has to say about work is embedded in a story about how we became who we are. Many historians have argued that it is not an entirely true story; but it is nevertheless an interesting one. Reducing it to the simple promulgation of a ‘work ethic’ destroys most of its interest, its power to provoke thought. The cliché works, as clichés often do, to make the idea at once more digestible and less alive.

In the process, several inconvenient signs of life drop away. One of them is the class content. As Weber tartly puts it, a ‘bourgeois businessman’, interpreting his bottom line as a mark of God’s blessing, ‘could follow his pecuniary interests as he would and feel that he was fulfilling a duty in doing so.’ Meanwhile, ‘The power of religious asceticism provided him in addition with sober, conscientious, and unusually industrious workmen’. That is, the shared beliefs of employer and employee caused both of them to act in the employer’s interests. ‘The work ethic’ is not the same for everyone: it depends where you are in a system of working relationships. Abstracting the phrase from the system loses that subtlety. A work ethic becomes the attribute of an individual. Some people have it, some people don’t, and all those who have it have the same thing. Society vanishes from the idea.

And then what vanishes next is ambivalence. As used by a cultural historian, the phrase offers a non-committal description of somebody else’s values. Some people believe that hard work is a sign of spiritual grace, just as some people believe that children are innocent, or that eating meat is wrong. I can describe such beliefs without saying whether or not I share them. For much of its life, that is how ‘work ethic’ has been used. If you track the quotations in the OED, you see that most users take up a position that is external to the values they are naming, and several are actively hostile — implying, for instance, that the work ethic is unwholesomely guilt-ridden, or that it’s destructive of beauty and pleasure. More recently, though, that critical reserve has been worn away by use. When the team needs to improve its work ethic, or when the lack of a work ethic among young NEETs demands urgent action, there is no doubt that we are talking about a Good Thing. The expression changes not its meaning but its function: once it served to identify certain values, now it works to enforce them.

This closure is then sealed into the phrase by the very peculiarity of its trajectory. As it spreads, it increasingly features in discourses where ‘ethic’, as a singular noun, never appears in any other connection. Insensibly, then, it starts to look as if the work ethic is the only ethic in town — not only that working is good, but also that there are no other ways of being good. At this point the work ethic has become (a) ahistorical, (b) unambiguous, and (c) unquestionable. We might wonder (idly, of course) whose interests are served by this perfect semantic storm.

Professor Peter Womack teaches literature at the University of East Anglia. His most recent book was the New Critical Idiom volume on Dialogue. His article in the current Cambridge Quarterly, ‘Dialogue and Leisure at the Fin-de-siècle’, looks to Oscar Wilde for another kind of ethic.

The Cambridge Quarterly is a journal of literary criticism which also publishes articles on cinema, the visual arts, and music. It aims, without sacrifice of scholarly standards, to engage readers outside as well as inside the academic profession. It welcomes articles that encourage the re-reading of familiar authors, as well as those that champion new or neglected work. The journal remains committed to the re-appraisal of accepted views, and the principle that criticism and scholarship should reinforce the pleasure for which literature and other works of arts are created.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Work ethics. By marekuliasz, via iStockphoto.

The post On ‘work ethic’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesArmchair travelsMyths about rape myths‘Wild-haired and witch-like’: the wisewoman in industrial society

Related StoriesArmchair travelsMyths about rape myths‘Wild-haired and witch-like’: the wisewoman in industrial society

Summers with George Balanchine

A hundred years ago in the summer of 1913, nine-year-old George Balanchine, then Georgi Balanchivadze, spent the last moments of normal childhood — in the country, in the forest by a lake — before he was abruptly brought back to St. Petersburg city and left by his mother in the Imperial Theater School to be trained to be a ballet dancer.

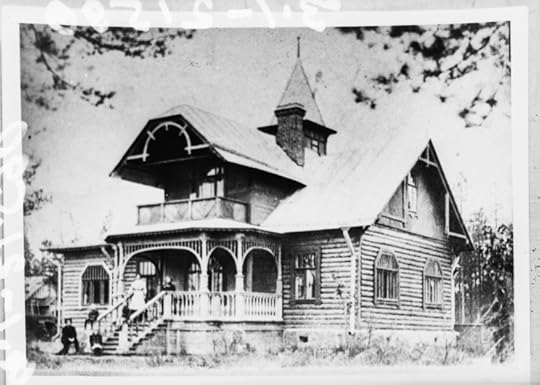

Five years earlier, the Balanchivadze family — Papa Meliton, Mother Maria, and children Tamara, Georgi, and Andrei — had bought land with money won in a lottery outside their city in Finland in a fashionable vacation “development” called Lounatjoki (in Finnish, southwest wind river). They’d built a big wooden fairytale dacha summer house, with stairways and porches and balustrades. They’d hosted some legendary summer parties.

The Balanchivadze’s home in Lounatjoki, Finland. Image courtesy of Bernard Taper.

But then they’d lost their money and had to move in year-round to their summer home. Little Georgi became an isolated child, with only his siblings for company, trudging through the snowy woods, helping out his mother in the family’s huge vegetable garden, practicing the piano at set times and hours. But then, for summers, the other dacha residents returned to their houses, for that brief marvelous few months when the sky stays light nearly all night.

George’s sister Tamara (left) and two friends. Image courtesy of The National Archives of Georgia.

There were other boys to run around, play and swim with. In 1913, in fact, the whole Russian empire was having its last normal summer; the next summer, World War I would start, followed by the Russian Revolution that would upend all of life as it was then known. We can imagine the lithe little Georgi of 100 years ago celebrating summer, running among those tall pine trees, hiding from his mother and “auntie,” jumping into the clear lake and scrambling out onto a granite boulder, shouting with a gang of boy children (and his little blond brother tagging along)…all unaware that soon he would be dressed in a cadet’s uniform like the other student dancers and fitted to a strict regimentation that knew no summer or winter.

In the summer of 2006, I took the slow commuter train from St. Petersburg’s Finland Station to find that dacha settlement. It’s not called Lounatjoki anymore, but Zakhotskoe — after the border wars of 1917 and 1939, it’s Russian, not Finnish. My fellow passengers were mushroom-pickers in hiking boots, carrying baskets and backpacks.

Where should my niece, a spirited traveling companion, and I go when we got off the train? An amateur historian had overheard us buying our Zakhodskoe tickets in the Finland Station. He drew us a map of the path from the train platform to the little lake that I think was called Sarkjarvi (the “lake of Sarks,” a little fish with red eyes). He told us how to recognize the ruins of the dachas, or rather their foundations, now covered with moss and grasses.

The abandoned path through the old dacha settlement ran straight among the tall silent pines, hiding those many mossy fundament ruins. We found the little round lake, reflecting the forest. We disrobed and swam in its cold clear water, then dried on a boulder, just as a young Balanchine would have. Afterwards we stumbled onto a marble stairway, alone in the woods — the only witness left of that idyllic summer a hundred years ago.

A staircase, the only remains, of Balanchine’s home in Finland. Photograph by Elizabeth Kendall.

But somewhere the ghost of the boy Balanchine was there too, hiding in the forest. As the summer of 1913 wound to an end, the carefree boy, thinking his own thoughts, would soon be torn away from family and woods and given a whole new family and a whole new un-childish world in the backstage of the great Mariinsky Theater and the majestic yet Spartan corridors of the Imperial Theater School.

Click here to view the embedded video.

In addition to Balanchine and the Lost Muse, Elizabeth Kendall is the author of Autobiography of a Wardrobe; American Daughter; The Runaway Bride: Hollywood Romantic Comedy of the 1930s; and Where She Danced. She is a tenured associate professor of Literary Studies at The New School. She has written for The New Yorker, Vogue, Ballet News, Dance Magazine, The New York Times, Elle, The New Republic and other journals.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only theatre and dance articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Summers with George Balanchine appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesNo love for the viola?“I am Troy Davis”Post-Soviet Chechnya and the Caucasus

Related StoriesNo love for the viola?“I am Troy Davis”Post-Soviet Chechnya and the Caucasus

Understanding history through biography

At the April 2013 Annual Meeting of the Organization of American Historians, Susan Ware, General Editor of the American National Biography, discussed her first year in charge of the site and her vision for its future. Ware argues that one of the best ways to understand history is through the lives of history’s major and minor players — and this means being as inclusive as possible about who is included. This mission also means frequent updates as our interpretations of history change. Fortunately, with 17,000 entries on the site covering every aspect of American history, there’s a thriving online community to support the project and find new writers.

Listen to the podcast:

The landmark American National Biography (ANB Online) offers portraits of more than 18,700 men & women — from all eras and walks of life — whose lives have shaped the nation. The wealth of biographies are supplemented with over 900 articles from The Oxford Companion to United States History and over 2,500 illustrations and photographs providing depth and context to the portraits. It is updated twice a year with new biographies, illustrations, and articles. Find out more about the latest update by visiting the Highlights page. American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS) sponsors the American National Biography (ANB Online), which is published by Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Understanding history through biography appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesUnderstanding history through biography - EnclosureAn Oxford Companion to surviving a zombie apocalypseThe life of a nation is told by the lives of its people…

Related StoriesUnderstanding history through biography - EnclosureAn Oxford Companion to surviving a zombie apocalypseThe life of a nation is told by the lives of its people…

No love for the viola?

To be frank, there has never been much love for the viola (or violists). As an erstwhile violist I would get two types of reactions about my instrument of choice: from non-musicians, “what’s a viola?” and from musicians… well just Google “viola jokes” and it will return some real doozies:

How do you keep your violin from getting stolen?

Put it in a viola case.

Why don’t violists play hide and seek?

Because no one will look for them.

What do you call the cadenza in a viola concerto?

Comic relief.

How is a symphony viola section like the Beatles?

Neither has played together for years.

Why is a viola like a grenade?

When you hear it, it’s too late!

The Grove Music Online entry on the viola cites that the “instrument of the middle” even back in 1752 was, as noted by J.J. Quantz (Versuch, 1752), perceived as

“…of little importance in the musical establishment. The reason may well be that it is often played by persons who are either still beginners in the ensemble or have no particular gifts with which to distinguish themselves on the violin, or that the instrument yields all too few advantages to its players, so that able people are not easily persuaded to take it up. I maintain, however, that if the entire accompaniment is to be without defect, the violist must be just as able as the second violinist.”

Photo by Frinck51. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons

I get it; the viola does look a lot like a violin, a viola solo is rare, the parts written for it are often deemed as mundane accompaniments, and many transposed pieces for the viola are awkwardly executed. I will admit that I did not dream of becoming a violist at first; in fact the only reason I made the transition was because my string ensemble desperately needed viola players. However, I quickly fell in love with its darker and richer tones, a quality which has been increasingly appreciated by composers, performers, and audiences.

For the first 250 or so years of its existence, solo viola compositions were few and far between. However a notable increase was seen in the 19th century with famed pieces such as The Viola Concerto in D by Carl Stamitz. The 20th century also saw an increase in solo pieces which may have been inspired by a wave of world class violists such as Paul Hindemith or William Primrose. More recently, conductor John Williams premiered his Concerto for Viola and Orchestra in 2007, and Nicholas Hersh arranged and conducted Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody for Orchestra and Solo Viola for the Indiana University Studio Orchestra.

With an array of beloved string quartets and quintets, the viola is “most at home” with chamber music. It is through this type of music that the viola (and violist) is often used to the fullest. Many works by “classical” greats such as Beethoven and Shostakovich reveal the viola’s register and timbre in both solo and polyphonic contexts. Duets are another arena that violists revel in. For example, Halvorsen’s Passcaglia for Violin and Viola (based on a theme by Handel) has become one of the more celebrated works in the viola’s repertoire. It was famously performed by Itzhak Perlman (violin) and Pinchas Zukerman (viola) in 1997, which you can see in the video below. Note the witty repartee between Perlman and Zukerman at the beginning of the video, with Zukerman proclaiming “a violin is easy to play. But a viola is something special!”

Click here to view the embedded video.

One time, during a string ensemble rehearsal of Bach’s Air on a G String, our teacher said, “I just want to hear the viola part on its own, as it is the most beautiful part of the piece.” After we gladly performed our part for our fellow players, rehearsal resumed with the next piece, one in which the viola section served as accompaniment, playing yet another banal alto part (choral singers will understand). But that’s okay, if violists are anything we’re team players.

Katherine Stopa is an Editorial Intern at Grove Music/Oxford Music Online. She is a Canadian born and raised, and has strong connections to music, pop culture and breakfast. She is currently pursuing an M.S. in Publishing at NYU’s School of Continuing and Professional Studies. You can follow her on twitter @katiest_tweets.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post No love for the viola? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLullaby for a royal babyConcerning the celloMusic to surf by

Related StoriesLullaby for a royal babyConcerning the celloMusic to surf by

July 22, 2013

Why should we care about the Septuagint?

Even though the Bible is one of the most widely read books in history, most readers of religious literature have no knowledge of the Septuagint—the Bible that was used almost universally by early Christians—or how it differs from the Bible used as the basis for most modern translations.

Timothy Michael Law, author of When God Spoke Greek: The Septuagint and the Making of the Christian Bible explains what the Septuagint is, and why it is so important to the study of Christianity.

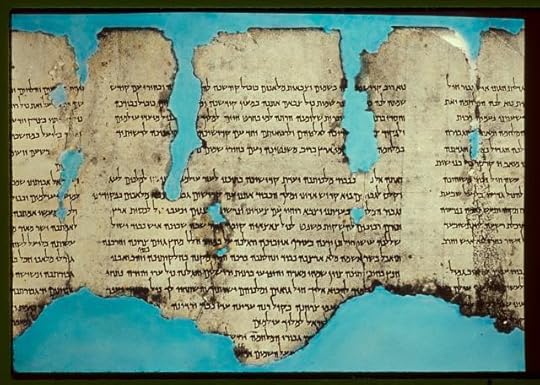

An early depiction of the Hebrew Bible translated into Greek as the Septuagint. Image credit: Photo by Xerones, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

What is the Septuagint?

The name Septuagint refers to what is mostly a collection of ancient translations. The Jewish scriptures were translated from Hebrew and Aramaic into Greek from about the third century BCE in Alexandria, a place booming with Hellenistic learning, to perhaps as late as the second century CE in Palestine. Originally the translation was of the Hebrew Torah alone.

A legend was written in the second century BCE to explain how the collection came about. In the legend, seventy learned men from the twelve tribes of Israel came to Alexandria to translate, so later when this tradition was passed down, the name “Septuagint” (seventy) was given to the entire collection of books that make up what Christians call the Old Testament.

The ancient world had known about translation activity, but there had never been a project this size and certainly not one for religious motives on this scale. I’ve always thought it’s one of the most important cultural artifacts of antiquity, but it often gets discarded as interesting only to those concerned with biblical studies. But there is also information in the Septuagint about the Greek language of the period, the socio-religious context of the Jewish Diaspora, and the very science of translation.

To me, the story of the Septuagint’s creation—what it tells us about the growth of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament, and its role in the birth and early development of Christianity—is absorbing.

Not much is known about the Septuagint outside of the academy. Why do you think that is?

In the West, we have a cultural tradition dominated by Protestant and Catholic Christianity. An early Latin version of the Bible was made as a translation of the Septuagint, but by the end of the fourth century Jerome began to argue that the Bible was in need of revision. He thought the Old Testament should be translated from the Hebrew so that it would match the Bible of the Jews. Jerome’s new translation, later called the Vulgate, was the first significant challenge to the position of the Septuagint as the “Bible of the Church.” As the Latin Church grew apart from the Greek East in the next half millennium, Jerome’s Vulgate finally became the standard Bible. The Protestant Reformers basically accepted Jerome’s position on the authority of the Hebrew Bible, and for that reason the vernacular translations were made from the Hebrew. So for the last 1500 years, the Septuagint has struggled to find readers in the West, although it is still read in the Greek Orthodox Church. The same bias for the Hebrew Bible affects scholars, too. Because the Reformation spread throughout Europe and left its imprint on the creation of the modern European (and then the American) university, the Hebrew Bible has been studied and the Septuagint has been seen as a mere “witness” to the Hebrew text. It was thrown in the Bible scholar’s toolbox to use only when the Hebrew was difficult to understand.

A photograph of the War Scroll, one of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Photographed by Eric Matson of the Matson photo service, 21 May 2012. From the Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

When we think about biblical manuscripts, the Dead Sea Scrolls have of course gained a lot of attention since their discovery in the 1940s. In some ways the Septuagint benefitted from the Scrolls.

The Septuagint is commonly treated only as a translation of the known Hebrew Bible text, and in some places a very bad one! But the discoveries in the Judean Desert provided a boost to interest in the Septuagint. Up to that time, the Hebrew Bible texts that were studied were the medieval editions. The Dead Sea Scrolls for the first time revealed many biblical texts that were a millennium older than the medieval editions. More spectacularly, these manuscripts showed significant divergences with the standard medieval text in some well-known biblical books.

The Scrolls proved that some books of the Hebrew Bible were still being edited, supplemented, reduced, etc., well into the Common Era. But if you were reading the Septuagint before the 1940s, you knew that it was produced in the Hellenistic period, and so you still might have concluded—even without the help of actual Hebrew manuscripts—that the Bible was in flux at this time based on the way these books appear in Greek in such alternative forms.

Imagine if you knew Russian, and when you were reading Dostoevsky in English you suddenly discovered that there was an entire extended passage, or one that was significantly abbreviated. You have two options. You either conclude the translator exercised a tremendous, even scandalous, amount of freedom, or you believe the English translator had a manuscript different to any others you ever knew existed in Russian.

Those were the two basic options for understanding the Septuagint, and most scholars chose the first route. But when the Dead Sea Scrolls showed these divergent text forms in Hebrew, and when some of these were represented verbatim in translation in the Septuagint, the calculus suddenly changed. Now that we had the Dead Sea Scrolls, we knew the Septuagint translators were in many of these cases translating actual biblical texts.

Septuagint scholars are about as grateful as any for the discovery of the Scrolls. The biblical texts from the Judean Desert now confirm what those familiar with the Septuagint already suspected: the divergences in some biblical books give a window into the Bible’s early formation history.

What role did the Septuagint play in the formation of Christianity?

Beginning with the New Testament itself, we see the influence of the Septuagint because these writers of what would become Christian scripture are writing in Greek. It’s natural that they turn to the Greek Jewish scriptures, but in some cases we can see how the Septuagint provided the perfect phrase—different to the same passage in the Hebrew—for them. The apostle Paul, for example, builds much of his magnum opus, the Book of Romans, with quotations from the Septuagint, not the Hebrew Bible.

Most of the early Christian movement was a Greek-speaking movement, so they too adopted the Greek Jewish scriptures as their new “Old Testament.” The early development of theological, homiletical, and liturgical language is almost exclusively indebted to the Septuagint. More needs to be done in this area, but it is clear that the Septuagint lies at the foundation of early Christianity.

Timothy Michael Law is Publisher and Editor-in-Chief of The Marginalia Review of Books. He is the author of When God Spoke Greek: The Septuagint and the Making of the Christian Bible and tweets @TMichaelLaw.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Why should we care about the Septuagint? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy do women struggle to achieve work-life balance?The Poetic Edda and Wagner’s Ring Cycle10 questions for Raúl Esparza

Related StoriesWhy do women struggle to achieve work-life balance?The Poetic Edda and Wagner’s Ring Cycle10 questions for Raúl Esparza

Myths about rape myths

In recent decades, England and Wales have experienced extensive rape law reform and a substantial rise in rape reporting, but the number of rape convictions has not kept pace, leading to a galloping attrition rate: the current proportion of recorded rapes that result in a rape conviction is about 7%. To the extent that rape law reform aimed at convicting more men of rape, it has not been an unqualified success.

This has led many erstwhile law reformers to turn their attention to attitudes to rape. Their argument is that reform has proved ineffective because so many people, particularly those involved in the criminal justice system, hold ‘rape myths’. This argument has achieved broad consensus; perhaps perplexingly, most people believe that most people believe rape myths. But I suggest that popular belief in rape myths has been exaggerated. We are creating myths about myths, or myth myths.

Myth Myth No. 1

There is a particularly stark justice gap in relation to rape — many rapes aren’t acknowledged as such by the victim, most acknowledged rapes aren’t reported, and most reported rapes don’t result in a conviction — so a particularly high proportion of rape complainants will not see the perpetrator convicted.

Throughout the criminal justice system, the proportion of offenders who end up convicted is tiny — higher than rape for some crimes, lower than rape for other crimes. Burglary has about the same attrition rate (from recorded crime to conviction). There is not good evidence that people are less likely to acknowledge or report rape than other crimes.

Myth Myth No. 2

Evidence from rape myth attitude surveys proves that people hold rape myths.

Current rape myth survey research tends to define rape myths as ethically wrong rather than factually false. What’s more, your view can be factually correct but still classed as ethically wrong and therefore a rape myth. So what these rape myth researchers are actually proving is that lots of people have views that are accurate but different from the researchers. We now have the oxymoronic ‘true myth’.

Next, rape myth researchers designed their questions to catch people, adjusting these questions until they managed to produce a bell curve. Bell curves have their uses, but they can’t be used to show that people have awful attitudes. This is just like making the driving test practically impossible to pass, then treating the resulting fail rate as evidence of appalling driving.

Myth Myth No. 3

People believe in ‘real rape’ – a very violent attack by an armed stranger on a woman who ends up physically injured.

What does this even mean? Does it mean that people believe ‘real rape’ is the only sort of rape, the most common sort of rape, or the most serious type of rape? The only strong evidence for any of these propositions is that ‘real rape’ is more likely to lead to a conviction at the end of a trial. But this doesn’t mean that jurors believe the ‘real rape’ myth — they might just find it easier to convict when the evidence doesn’t boil down to whose story they believe.

Myth Myth No. 4

People believe that women cry rape, but they don’t.

There isn’t good evidence that people are less believing of rape complainants than other complainants. Mumsnet’s recently launched rape awareness campaign is called simply ‘We Believe You’. There also isn’t good evidence as to the proportion of women who do cry rape. To achieve justice, it is important to be both sympathetic and questioning towards all complainants, including rape complainants.

Myth Myth No. 5

People believe that women show consent to sex through their behaviour, such as inviting a man back for coffee, but this isn’t the case.

It may be messy, but people do tend to show sexual consent with roundabout signs; there is no formula. If people tell the researchers that coffee is one of those signs then it probably is. Sometimes rape myth reformers’ real objection seems to be to a traditional construction of heterosexuality in which men pursue women. There are many good reasons to challenge this gendered binary, but it can’t be done by creating a code cracker for sexual consent. A different sexual vision needs to be argued for openly, not smuggled in as opposition to rape myths.

Myth Myth No. 6

Jurors scrutinise rape complainants’ behaviour: why she was there, what she was wearing, etc. This is wrong.

It’s not wrong: jurors have to work out if the woman was consenting. This can only be done by looking at her behaviour, and of course the defendant’s response to it.

Myth Myth No. 7

People blame rape victims, even when they believe them.

There isn’t good evidence that people blame rape victims more than other crime victims. Public opinion surveys such as the Amnesty survey ask people if they think rape victims are ‘responsible’ and then treat responsibility as equivalent to blame. It isn’t. In fact, there is evidence that people tend to blame rape victims less than other crime victims; witness the vitriol heaped on the McCanns.

Helen Reece joined LSE as a Reader in Law in September 2009. Her main teaching responsibilities and research interests lie in Family Law. She is the author of “Rape Myths: Is Elite Opinion Right and Popular Opinion Wrong?” (available to read for free for a limited time) in the Oxford Journal of Legal Studies.

The Oxford Journal of Legal Studies is published on behalf of the Faculty of Law in the University of Oxford. It is designed to encourage interest in all matters relating to law, with an emphasis on matters of theory and on broad issues arising from the relationship of law to other disciplines.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Myths about rape myths appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesArmchair travels‘Wild-haired and witch-like’: the wisewoman in industrial societyThe good, the bad, the missed opportunities: UK government

Related StoriesArmchair travels‘Wild-haired and witch-like’: the wisewoman in industrial societyThe good, the bad, the missed opportunities: UK government

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers