Oxford University Press's Blog, page 922

July 22, 2013

Europe’s 1968: voices of revolt

May ‘68 is often used as a shorthand for the protests and revolts that took place in that year, conjuring up images of barricades and Molotov cocktails in the Latin Quarter of Paris. But 1968 did not take place only in one year; it began in the mid 1960s and went on deep into the 1970s. Neither was it restricted to Paris; things happened from Madrid to Leningrad and from Copenhagen to Athens. It was a real European revolution – or was it? Europe was divided by the Cold War and between democracies in the north and dictatorships in the south. And activists did not always share the same ideas. When West German student leader KD Wolff attended an international youth festival in Sofia in 1968, he was appalled by the naïveté of the Czechoslovak activists who seemed to understand nothing about Marxist revolution. “You couldn’t talk to them. They were stupid,” he recalled. “They said ‘Freedom of the press! Dubcek is our man!’ Boring you know.” However, Polish activist Sewewrn Blumensztajn didn’t understand the West German militants either. He lived in a communist state and didn’t like it. “For us democracy was a dream,” he reflected, “but for them it was a prison.”

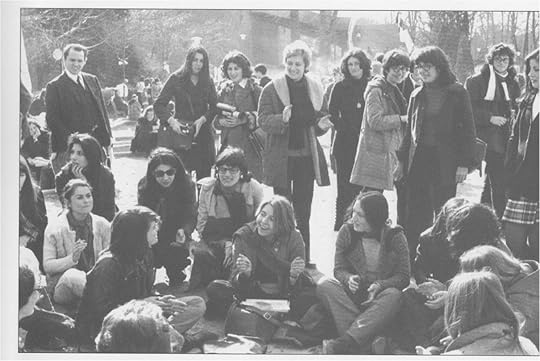

Feminist group in France, 1971.

Activists encountered each other all over Europe in the years around 1968. They travelled for their studies to France, Italy, or West Germany and to summer camps for young communists in East Germany or for young anarchists in Switzerland. They fled from Franco’s Spain or from Greece after the 1967 military coup as political exiles. Sometimes they just showed up as revolutionary tourists in Berlin or in Paris for May ’68. The Iron Curtain was a barrier but it was porous in part and they shared a similar history. Their parents had resisted Nazism or fascism in the Second World War, or had not, and were either to be imitated or hated. They had a common hatred of imperialism, whether American or Soviet, and loved Mao, Ho Chi-Minh, and Che Guevara. In many ways, however, they failed to understand each other — not only over communism but also over consumerism, which was despised by Western militants but craved in the East. Time did bring them closer together. Some West European Marxists became disillusioned with Marxism and Third World revolution in the 1970s and were impressed by the struggles of East European activists against Communist totalitarianism. Scorn turned to admiration.

Activists wanted not only to change the world but to change themselves, and this too changed over time. When they met obstacles in one sphere and the authorities clamped down, they rethought and reworked their strategies for another opening. Even in the West, Marxism and anarchism were only two options: 1968 gave rise to feminism, gay rights, and men’s groups. The nuclear family came under attack and experiments in communal living proliferated from London to Leningrad. Liberation theology was born and base communities sprang up in conflict with established churches. 1968 generated radical plans to reform prisons and to turn psychiatric hospitals inside out, forcing a rethink of who was mad and bad, who good and sane. Many activists came out of 1968 with a sense that they had burned their fingers on political violence or hedonism. Others were more upbeat. “I don’t look back nostalgically to that 1968 moment,” says British activist Jeffrey Weeks, “I actually see it as having opened up possibilities, which are still continuing.”

Robert Gildea is Professor of Modern History at the University of Oxford. He was a Lecturer at King’s College London (1978-79) and Fellow and Tutor in History at Merton College Oxford (1979-2006). He is a Fellow of the British Academy. He is co-editor, with James Mark and Annette Waring, of Europe’s 1968: Voices of Revolt (OUP, 2013).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Feminist group in France, 28 March 1971. Used with permission of Catherine Deudon, from ’Un Mouvement a soi. Images du Mouvement des Femmes, 1970-2001′.

The post Europe’s 1968: voices of revolt appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesArmchair travels‘Wild-haired and witch-like’: the wisewoman in industrial societyWhat have we learned from modern wars?

Related StoriesArmchair travels‘Wild-haired and witch-like’: the wisewoman in industrial societyWhat have we learned from modern wars?

July 21, 2013

It’s only a virus

“It’s only a virus.” How often do GPs utter those words over the course of a working day? They mean, of course, that your symptoms are mild, non-specific, and don’t warrant any treatment. If you just go home and rest you’ll recover in a few days. But that does not apply to all viruses, and the flu is one that can vary enormously in severity. It may be relatively mild like the 2009 pandemic strain, but it can also be a killer. Just consider the H5N1 bird flu that emerged in 1997, which kills around 60% of those it infects. Now a new bird flu virus is on the loose — H7N9 — that seems to be almost as deadly as its predecessor.

Photo by Fondazione Giannino Bassetti/UAF Center for Distance Education, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

H7N9 was first reported this February in China. By the beginning of June, it had caused 132 known infections, including 37 deaths. This has galvanised flu experts around the world into action. While the virus hunters are trying to locate the origin of the outbreak and stop the virus from spreading any further, other scientists are racing to make a vaccine against it.

So far there is both good news and bad news to report. One piece of good news is that, to date, H7N9 has not succeeded in spreading effectively from one person to another. At present, each new infection seems to be acquired either directly or indirectly from an infected animal — presumably some kind of domestic poultry. But the bad news is that flu viruses mutate quickly and this one already has many of the mutations it needs to spread easily between humans — a recipe for a pandemic.

Again, on the positive side, H7N9 has not yet spread outside China, and at the time of writing, there seems to be a lull in new cases. However, cases are scattered widely across China with no obvious source. Scientists must find its origin in order to stop it from spreading further, generally by closing local live poultry markets and culling infected flocks. But so far they are baffled. While they have detected infected birds in several markets, they can’t find the virus on any of the farms that supply the birds. Until they pinpoint the source, the question of whether to close markets remains an open one; while on the one hand this would prevent transport of infected birds, on the other it risks the trade going underground.

Scientists trying to make a vaccine also face a dilemma. Flu vaccines take several months to prepare so it’s best to get ahead of the game, but start too early and the virus may mutate to become unrecognisable to immunity generated by the vaccine. Generally the gap between the start of an epidemic and vaccine availability is plugged by using anti-viral drugs. But the Chinese often give anti-virals to poultry and so, unsurprisingly, some cases are already resistant to drugs like Tamiflu. Another piece of bad news comes from early stage vaccine development. Apparently, H7N9 only stimulates a weak immune response. This means that around 13 times more of the vaccine would be needed to protect against this virus than is required with other flu strains. So if there is a pandemic there will be less vaccine to go around. Conventional flu vaccine strains are laboriously grown in hens’ eggs, making the whole process difficult to scale up. However, on the plus side, a synthetic vaccine is being developed which could cut the production time by up to a month.

With all the uncertainty about the origin of H7N9, the speed and randomness of its mutations and the unpredictability of its spread, we are left with many unanswered questions to discuss and debate.

Dorothy H. Crawford is the Robert Irvine Professor of Medical Microbiology and the Assistant Principal for Public Understanding of Medicine at the University of Edinburgh. She is the author of Virus Hunt: The search for the origin of HIV/AIDs, as well as The Invisible Enemy: A Natural History of Viruses , Deadly Companions: How Microbes Shaped our History, and Viruses: A Very Short Introduction.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post It’s only a virus appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesVaccination: what are the risks?‘Wild-haired and witch-like’: the wisewoman in industrial societyWhy do women struggle to achieve work-life balance?

Related StoriesVaccination: what are the risks?‘Wild-haired and witch-like’: the wisewoman in industrial societyWhy do women struggle to achieve work-life balance?

Armchair travels

This is a piece about subjectivity. And while we’re on the topic, let’s just stop for a moment to talk about me. When the weekend paper delivers its fullness at the breakfast table, I don’t stop to read the travel section. It’s the first to go into the recycling bin. Travel writing bores me. And so do travel photos, ever since I can remember being forced to feign interest through someone else’s slideshow narrative.

Perhaps, then, I’m a glutton for punishment, but I have spent the last year reading dozens of travel accounts from the nineteenth century. Travel writing tends to slip between disciplinary cracks. It is not literature of the highest order, nor is it straightforward archival material. Yet travel works were highly popular in nineteenth century France, and this fact, if nothing else, must move the curious cultural historian to ask why. I have an answer, too: life was less than settled in nineteenth-century France. The Revolution may have introduced the concepts of nationhood and citizenship, but French men and women spent much of the next century (and some might argue the one after that), settling on a shared understanding of these terms. While the French drew on tradition and ideology to conceptualise their ideal of the nation, they found inspiration equally in the travel account. Elsewhere could be a site for imagining the nation; ideals and utopias, disgruntlement and desire, all could take shape on a blank, foreign canvas. It is no coincidence that some of the greatest writers in a century when writing was truly great, also wrote travel accounts. Flaubert, du Camp, Nerval, and Gautier can be counted among them. The novel and the travel account were in many ways equal mixes of reality and fiction. Writers would use a fictional or exotic canvas to tell stories of themselves. If their works are fictional, they are also political, and often based on deeply felt impressions of their own world. The tension between fiction and fact is underscored by the fact that Alexandre Dumas produced travel works, but these were written at his desk, at home in France.

Théophile Gautier by Nadar c1856

Edward Said has written, most evocatively and convincingly, about the way the exotic could be shackled to the needs of the political. But he assumed that this was always for the purpose of domination. He was wrong about that. Travel literature might reify the exotic. It might paint Arabs as primitive and lazy. It often did. But it also called on stereotypes of the foreign in order to stereotype the familiar. Elsewhere could be a place for imagining the nation. Travel writing could be a forum for the expression of criticism. Materialism, capitalism, the loss of Catholicism’s legitimacy, individualism: all of these criticisms were levelled at France through the medium of the travel account that could describe how things might be, by describing somewhere else. Théophile Gautier might not figure among the very greatest that creative Paris produced in the nineteenth century. He was, nonetheless, a man of wonderful insight and wit; a keen observer of his age, and an enthusiastic traveller. Gautier worshipped art. He hated the cynical materialism that he felt defined his era. In Italy, Spain, Russia, and Egypt, he found purity. He, himself, wished to be Oriental. “It seems to me,” his friends reported him as saying, that he had “a Muslim soul. I need blue sky. I will go to the Orient and make myself into a Turk!” In the Orient, in fact, Gautier – who so hated the “civilisation of factories and coal,” – found himself.

And isn’t that the nature of travel writing? Nineteenth-century French writers travelled not to lose themselves, but for precisely the opposite reason. They went elsewhere for the purpose of self-discovery and self-expression. It is in this sense that travel writing is a deeply subjective genre. And if it was thus in the nineteenth century, arguably, it is still so. This might make for irritation for impatient and intolerant readers such as me, but it’s a golden seam that can lead to a mine for the historian.

Julie Kalman is a Senior Lecturer in history at Monash University. She is a specialist of nineteenth-century France and her writing to date has dealt with the interplay between French and Jewish history in this period. Her most recent publications include the articles “The Jew in the Scenery: Historicising Nineteenth-Century French Travel Literature” and “Going Home to the Holy Land: The Jews of Jerusalem in Nineteenth-Century French Catholic Pilgrimage,” and her book, Rethinking Antisemitism in Nineteenth-Century France.

French History offers an important international forum for everyone interested in the latest research in the subject. It provides a broad perspective on contemporary debates from an international range of scholars, and covers the entire chronological range of French history from the early Middle Ages to the twentieth century.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Portrait of Théophile Gautier by Nadar. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Armchair travels appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories‘Wild-haired and witch-like’: the wisewoman in industrial societyThe good, the bad, the missed opportunities: UK governmentIntersections of sister fields

Related Stories‘Wild-haired and witch-like’: the wisewoman in industrial societyThe good, the bad, the missed opportunities: UK governmentIntersections of sister fields

July 20, 2013

‘Wild-haired and witch-like’: the wisewoman in industrial society

Many of us rely on herbal remedies to maintain our health, from peppermint tea to soothe our stomachs to arnica cream for alleviating bruising. Such is the faith in these remedies that Britain’s National Health Service (NHS) has funded alternative medical treatments and specialist homeopathic hospitals. However, in recent years, there has been impassioned debate about the efficacy and risks of alternative medicine. In 2010 The Telegraph reported the British Medical Association’s announcement that its members considered these practices to be ‘witchcraft.’ And in June 2013, NHS Lothian took the decision to cease funding homeopathic treatments. So what are the origins of these controversial set of healing practices? By whom were these skills used and for what purpose?

There are particular regions of the UK where historians have discovered evidence of alternative healing cultures including London, the South West, and Lancashire. Historians already know that wisewomen were important purveyors of traditional healing techniques in pre-industrial times. They were the equivalent of the present-day NHS 24; providing treatments for minor injuries such as burns or cuts and setting broken bones. These practitioners were well known for their work laying out the dead and delivering babies. Often older members of communities, they passed on their knowledge through female networks of family and friends.

Research on the career of one wisewoman working in Lancashire in the early twentieth century has revealed new and unexpected information about the history of alternative healing practices. Nell Racker (1846-1933) was a community midwife, herbalist, and spiritual healer. Nell’s career reveals that despite the challenge from the increasing importance of hospital-based medicine, remarkably, alternative healing networks and practices found ways to survive well into the twentieth century.

During the nineteenth and early twentieth century, most women gave birth at home with the help of women like Nell who had learned their midwifery skills by being present at births. Working-class women continued to prefer the services of these bona fide midwives, largely because they had built up relationships of trust having been cared for by these practitioners through several pregnancies, and, in the case of Nell, having sought her advice for a range of health problems.

Nell was not only famed for her skill as a midwife, but she was greatly respected as an herbalist. Using ingredients collected from the moors near her home, Nell created herbal ointments and preparations for her clients. We know that these services were extremely popular, with clients travelling large distances and queuing at her door to buy her remedies.

Nell was a truly remarkable practitioner. Her range of services included many of those that historians would expect from a local wisewoman, but fascinatingly they also encompassed more irregular and even controversial services. Nell’s clients told of their delight at her accuracy as a clairvoyant. She had been schooled in psychological healing techniques such as spiritualism and divination by her mother. Spiritual healing work using charms and incantations allowed her to attend to the emotional realm of well-being as well as the physical.

Perhaps inevitably, Nell’s more unusual services led to speculation about her practice and her character. Archival research has revealed that while the local community were impressed by her healing achievements, some also feared her prowess. Allegations of witchcraft were made repeatedly during her career. What is significant about these suggestions is that there is evidence to suggest that Nell may have deliberately encouraged the association of her work with the occult. Observers told of her wild hair and witch-like appearance which only added to her reputation as a powerful healer. Clearly, this wisewoman was not fazed by the categorisation of alternative healing practices as witchcraft.

Nell died in 1933, around the time that hospital-based care, especially for birth, was becoming the norm. Her career spanned an era of remarkable change in healthcare in the United Kingdom, yet her work reminds us of the significance of continuity and local culture in healthcare. Witch or not, what is absolutely clear about this traditional practitioner is that not only her skills in orthodox practice but also her more irregular and controversial work were fundamental to the health of her community. Regardless of speculation about the occult nature of some of her practices, Nell was greatly respected for the skill, discretion, and care she provided for her clients. Her career reminds us that treatments which achieve acceptable results for patients come in many forms and the freedom to choose is important. This is as true today as it was in early twentieth-century Lancashire.

Francesca Moore is Special Supervisor of Studies in Historical Geography at Newnham College, University of Cambridge. She is the author of “‘Go and see Nell; She’ll put you right’: The Wisewoman and Working-Class Health Care in Early Twentieth-century Lancashire” in Social History of Medicine, which is available to read for free for a limited time. Follow her on Twitter @drfplmoore.

Social History of Medicine is concerned with all aspects of health, illness, and medical treatment in the past. It is committed to publishing work on the social history of medicine from a variety of disciplines. The journal offers its readers substantive and lively articles on a variety of themes, critical assessments of archives and sources, conference reports, up-to-date information on research in progress, a discussion point on topics of current controversy and concern, review articles, and wide-ranging book reviews.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via Glaucoma: not just a disease of adults

Why do women struggle to achieve work-life balance?

Is work-life balance consistent with professional ambition? A recent study concludes that young women are now proclaiming that they don’t want to be leaders. Does this data suggest that young women who do want to be leaders should not bother to ‘lean in’ by acquiring expert level knowledge, attaining specialized skills and pursuing experience-building work projects when they have the opportunity? Or does this research mean that women should go ahead and work hard prior to having families, but remain in subordinate positions throughout their careers? Why bother to work so hard early in life only to subsequently decline promotions and leadership roles due to an eventual lack of willingness to sacrifice everything to achieve notable success?

Photo by George Joch/Argonne National Laboratory, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

Furthermore, when young women cannot help but notice that the majority of leadership roles in almost every professional field are held by men, they cannot be faulted for concluding that the reason for this reality may be that achievement, recognition, and higher pay in the workforce might not be compatible with family life for women, even in our modern times. However, there are many serious drawbacks extending beyond the workplace for women who do not pursue educational recognition and professional advancement. First and foremost, the difference in pay and benefits (such as health benefits) between jobs that require high level education and those that do not can leave women and their children dependent on less than favorable personal family arrangements. Yet there is no doubt that even as doors open for women, the reality remains that there are only twenty-four hours in a day.

How can young women reconcile the genuine need for work-life balance with the fact that they may ultimately find themselves declining the numerous prestigious leadership opportunities available to them once they become highly qualified? Women may even take this long-term restriction of goals to heart and perform less effectively> during schooling and at work, so that they ultimately will not be given the choice of whether to decline or accept leadership roles. This apparent paradox often results in ambivalence among promising young women during their educational and early occupational years. There is an answer to this very real dilemma. A genuine solution lies in the fact that women need to actively create new definitions of leadership positions in the workforce. As more and more women continue to enter into prominent fields, these women need to redefine the rules for success so that they can continue to maintain a balanced and satisfying family life compatible with mid-career and senior-level success. Just because the road to respect has traditionally involved hours of face time and long days in the office that does not mean it must continue to be this way. In fact, part-time workers often forgo long, possibly wasteful breaks during the workday in favor of an abbreviated, yet more productive, workday.

For physicians in particular, where female medical students have outnumbered male medical students for several years, the established route to professional credibility and an esteemed reputation involves extensive work hours, on call duties, and a sense of pride in constant availability. Yet over the years this work ethic has not functioned to protect physicians from the crisis of declining reimbursement and increasing bureaucracy. Instead, this situation has actually served to exacerbate the lack of economic viability for women who want to work part-time. Malpractice premiums are so high that often the low reimbursement for part-time work cannot be sufficient to cover the costs of overhead.

Clearly the traditional rules have not worked. Women professionals must lead, not only by securing the stamp of approval from higher-ups, but by becoming valuable enough and skilled enough to have the leverage to insist on new rules, better rules that reward quality rather than quantity. Consequently, if women anticipate that they may choose to forgo intense work either briefly or even long-term in favor of work-life balance, an early investment of time and education and training is of great benefit. Women who ‘lean in’ early in educational years gain the skills, confidence, and credibility to be able to make their own rules if they chose to do so later. Leaning in early on does not have to translate into a lifetime of difficult sacrifices and painful choices. Hard work and commitment can position one to be able to find and attain non-traditional careers that are challenging, fascinating, and compensate well on an hourly bases, even allowing self-limited work hours to be lucrative and fulfilling. The key is opening one’s eyes to be able to make the environment adapt to the changing workforce—not reluctantly accepting antiquated rules that reward long hours rather than results and creativity. Those who have taken the initiative to seize the undefined opportunities and create new roles have found that early dedication to building valuable experience is extremely rewarding because while it can pave the road for traditional leadership roles, it also opens doors for non-traditional leadership roles that can change the future of the profession itself.

Heidi Moawad M.D. is author of Careers Beyond Clinical Medicine, a resource for health care professionals who are interested in professionally adapting to the changing medical environment while improving the health care system. Dr. Moawad teaches at John Carroll University in University Heights, Ohio and in a recipient of The McGregor Course Development Grant Award in Globalization Studies. Read her previous blog post “How will a changing global landscape affect health care providers?”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Why do women struggle to achieve work-life balance? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow will a changing global landscape affect health care providers?Vaccination: what are the risks?Glaucoma: not just a disease of adults

Related StoriesHow will a changing global landscape affect health care providers?Vaccination: what are the risks?Glaucoma: not just a disease of adults

July 19, 2013

The superpower I want most

Back in June, we asked you to tell us your favorite superpower. After reviewing several entries, our expert panel of judges has selected Gary Zenker’s piece on “The superpower I want most.”

By Gary Zenker

To select just one — and just one — superpower is akin to making someone choose just one ice cream flavor from a Baskin Robbins or one flavor from Rita’s Water Ice. It can be done, of course, made easier knowing that others await to be sampled another day. Choosing one with the knowledge that it precludes you from ever trying another makes the choice harder…but mostly for those individuals focused on themselves.

My personal choice is perhaps easier than for others. It dates back to one of America’s first superheroes, Superman, and what is in reality his most striking power.

That power isn’t the one you would first think. It isn’t his super strength, his invulnerability, or even that crazy freeze breath he sometimes uses against select villains in the (excuse the pun) heat of battle. In fact, his most striking power and the one I would want most is none of those he acquired by living under a yellow sun. The power I would want most is the one he learned from his father as superman grew from boy to adult. The power I would want is the ability to influence others to be better.

By holding an absolute moral code by which he lives and acts, people know what Superman stands for…and what he stands against. Superman believes in doing the right thing, no matter how people treat him. And we know he stands by that code no matter what is thrown at him (or by whom it is thrown).

Seth Zenker dressed as Captain Marvel for his Comic Con appearance this year. Photo by Gary Zenker. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

That power doesn’t come free: it exacts a definite price involving personal sacrifice. Superman must always live the part because one slip and he is labeled a hypocrite at best. At worst, he loses the trust others have in him, no matter how many good deeds he does or how many lives he changes for the better. Kryptonite isn’t the only thing that can take away his most astounding power. And he is well aware of it.The power to influence people around you can affect tens, hundreds, or even thousands of other people and continue to do so far into the future. But you only have to affect one other person for someone to declare that you possess superpowers.

You don’t have to affect everyone around you to be a Superman. If you have a young child (like I do) you know that you can be that superhero…at least for a short time. Each one of us has, at some point in our lives, had someone do something for us so extraordinary that we remember that moment forever. And we model that behavior and pay it forward to others.

After some careful thought, it turns out that I already have the superpower that I want most. The everyday challenge is ensuring that I use that power for good every day and every time.

Gary Zenker is a 25 year marketing professional, helping companies and entrepreneurs create strategic plans and then implement them. He also founded and leads The Main Line Writers Group in King of Prussia PA. His first book, co-authored with his son Seth, Says Seth, offers life observations from a six year old perspective with snarky after-comments and is available through Amazon and on Kindle. He is (obviously) a big fan of superheroes and the many lessons we learn from their stories.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only arts and leisure articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The superpower I want most appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Poetic Edda and Wagner’s Ring CycleThe pleasure gardens of 18th-century LondonForging Man of Steel

Related StoriesThe Poetic Edda and Wagner’s Ring CycleThe pleasure gardens of 18th-century LondonForging Man of Steel

Vaccination: what are the risks?

All prediction is probabilistic. Maybe that statement is unfamiliar. It’s central to the thinking of every scientist, though this is not to the way media commentators like Jenny McCarthy approach the world. Scientists make certain predictions, or recommend courses of action on the basis of the best available evidence, but we realize that there is always an element of risk. Particularly in regard to childhood vaccination, that idea of relative risk can dominate thinking.

What the public health authorities ask is that young parents take a perfectly normal child to their physician or nurse practitioner where they are then exposed to a mild form of virus, or injected with a non-living product derived from some human pathogen. Given the nature of any immune response, the kid may be grumpy for a couple of days due to various chemicals produced by the body, but that’s hopefully the end of it and the child will then be protected from some horrible disease. Where this becomes problematic is that, because most kids in western society are vaccinated and we have sufficient “herd immunity” to protect the others, younger adults have never seen (or experienced) diseases like measles, whooping cough, diphtheria, and so forth that can be truly horrible and even kill.

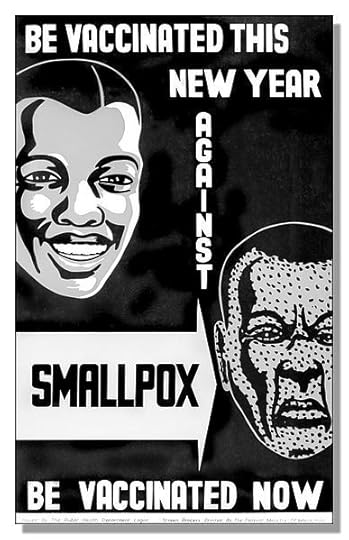

By 1979, global vaccination campaigns successfully eradicated the smallpox virus (variola). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Then there are often well-publicized reports of vaccinations that went very wrong. For any scientist to give credence to such information they will want to see a proper, statistically valid analysis. But that is not, of course, the world most of us live in. As was pointed out several years back by Stephen Colbert when discussing comments on the human papilloma virus vaccine, many will believe an anecdote from The New England Journal of the Lady I Just Met rather than the statements based in evidence from responsible authorities like the Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC) or the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Still, things do occasionally go wrong with vaccines. A case in point would be giving the live Sabin polio vaccine to an infant with a hitherto undetected, profound immunodeficiency. Perhaps the child was protected until then by passively acquired maternal antibodies, but as those wane, the risk posed by life-threatening infections would soon become clear. Then there’s a rare genetic condition that can cause a child with fever to go into severe convulsions and become epileptic: that would have happened anyway, but vaccination may bring on the first episode. Convulsions associated with fever are relatively common in small children, usually without untoward sequelae, but there have been situations in which this has happened with childhood vaccines and, as a consequence, the product has been rapidly withdrawn. The massive preponderance of evidence with the standard, long available vaccines of childhood is, though, that any risk of adverse effects is infinitely smaller than the dangerous short- and long-term consequences of contracting the actual disease.

There are some situations where vaccination is mandatory. If, for instance, you want to travel to West Africa, then return without taking the risk of being quarantined, you must take the yellow fever vaccine. It’s a very good and long-established product, so most will be happy to do that when they understand what an awful disease this is. If we were to face a truly horrible pandemic like that imagined in the movie Contagion, I very much doubt that many would refuse an available vaccine, especially for their children.

Emergency situations are where the relative risk equation with vaccines can become a prominent consideration. When we need to get something out very quickly in the face of a major threat, there is just not time for the extensive safety testing that is normally required. Over the decades this has, in practice, been mostly an issue for influenza vaccines. The influenza viruses change constantly and, because they spread with such speed, any vaccine has to be rolled out fast if it is to be of value. Though the protocols used to make the product will be thoroughly tested and approved, modifying the virus proteins slightly (which is what nature actually does) increases the possibility of untoward consequences.

We’ve got better at making influenza vaccines safely over the decades, but there is still a minimal, finite risk, especially with very young children. Any danger associated with injecting large amounts of viral protein and adjuvants (substances that promote immunity) is eliminated when we turn to the alternative of low-dose, live attenuated vaccines that are just dropped in the nose. Such products are, though, not approved in the USA for the elderly, the population that is generally at greatest risk from influenza. I take the opportunity to be injected with the killed vaccine every year.

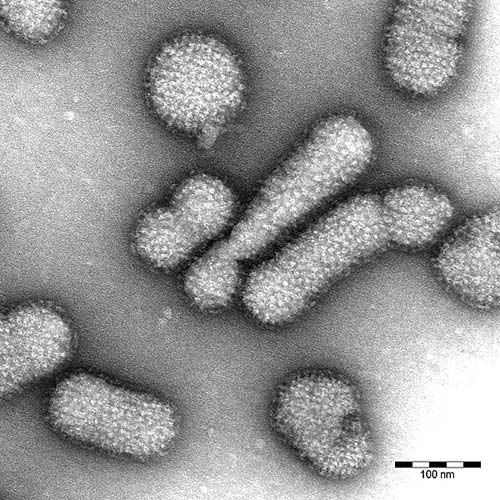

The influenza virus mutates frequently, requiring a new vaccine to be developed each year. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Vaccine research is a very dynamic area of science, with the focus being on developing better and safer products. There are also infections where no vaccine is currently available, particularly for HIV and Hepatitis C virus. The same is true for the noroviruses that can destroy your cruise ship vacation. In general, there is little problem of vaccine acceptance in developing countries where the common infectious diseases of childhood are still at a high prevalence. But we can’t be complacent, and we’re seeing far too high an incidence of, particularly, whooping cough and measles in western societies, leading to some deaths. Vaccinating children is a collective responsibility. The very young and the elderly are particularly at risk from, especially, the respiratory infections of childhood. Keeping herd immunity high protects all of us.

Relative risk defines the human experience. Most of us don’t think about it when strapping our kids into a car safety seat, but what we are in effect doing is acknowledging that we are trying to minimize a finite risk. There may also, for example, be the danger that restraining a small child could lead to their being trapped in a serious accident. But we acknowledge that, following an impact, the probability of being thrown out the window or against a hard surface is infinitely higher. We also allow children to take risks climbing on playground equipment, riding bicycles, or driving quad bikes because we understand that they have to grow in judgment so that they can live satisfactorily in a potentially dangerous world. Emphasizing personal freedom, some parents will not mandate that their kid wear a bike safety helmet, though the relative risk justification for that could not be more obvious.

With infectious diseases, childhood vaccination offers the infinitely lower risk alternative. And it’s not just for the short term. Imagine how you would feel if, for example, your unimmunized, pregnant daughter contracts rubella. Many diseases, like measles, are much worse in previously un-exposed, or unvaccinated, adults. Will your son who contracted mumps while travelling in a developing country thank you if he suffers testicular atrophy, and even sterility, as a consequence?

If you are a young adult who is not sure whether your parents had you vaccinated, check with your local physician or travel clinic before you head off to the more exotic parts of the world. Do that at least six to eight weeks ahead of time so that you can be given the standard childhood (and any other) vaccines, and there is time for them to take effect. Nothing in life is absolutely safe, but much of what we do as sensible human beings is concerned with minimizing avoidable risk.

Peter C. Doherty is Chairman of the Department of Immunology at St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital, and a Laureate Professor of Microbiology and Immunology at the University of Melbourne. He received the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1996. In addition to Pandemics: What Everyone Needs to Know (September/OUP), he is the author of The Beginner’s Guide to Winning the Nobel Prize: Advice for Young Scientists, Their Fate is Our Fate: How Birds Foretell Threats to Our Health and Our World, published in Australia as Sentinel Chickens: What Birds Tell us About Our Health and the World; and A Light History of Hot Air. Follow him on Twitter at @ProfPCDoherty.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Vaccination: what are the risks? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGlaucoma: not just a disease of adultsCritical Thinking For Helping ProfessionalsUtilizing the Body to Address Emotions: Integrative Body-Mind-Spirit Social Work

Related StoriesGlaucoma: not just a disease of adultsCritical Thinking For Helping ProfessionalsUtilizing the Body to Address Emotions: Integrative Body-Mind-Spirit Social Work

The Poetic Edda and Wagner’s Ring Cycle

By Carolyne Larrington

Heil dir, Sonne Hail, sun!

Heil dir, Licht! hail, light!

Heil dir, leuchtender Tag! hail, radiant day!

Lang war mein Schlaf; Long was my sleep;

ich bin erwacht. I am awakened.

Wer ist der Held, Who is the hero

der mich erweckt? who awakened me? Siegfried, Act III, sc. 3.

At the climax of Siegfried, an astonishing emotional and dramatic climax within the Ring, Brünnhilde at last awakens from her enchanted sleep. Her ecstatic song quotes directly from the Poetic Edda, combining lines from the first three stanzas of the Old Norse poem Sigrdrífumál (The Lay of Sigrdrifa).

Heill dagr, heilir dags synir, Hail to the day! Hail to the sons of day!

heil nótt oc nipt! … hail to night and her kin! …

Lengi ec svaf, lengi ec sofnuð var, … Long I slept, long was I sleeping …

hverr feldi af mér fölvar nauðir? Who has lifted from me my pallid coercion?

Wagner saw that the simplicity and intensity of the poem’s language at this transcendent moment could not be improved upon. Brünnhilde awakes to her hero, the man who knows no fear, to a new world in which — deprived of her divinity — a new human existence of love and glory seems possible for her and for Siegfried.

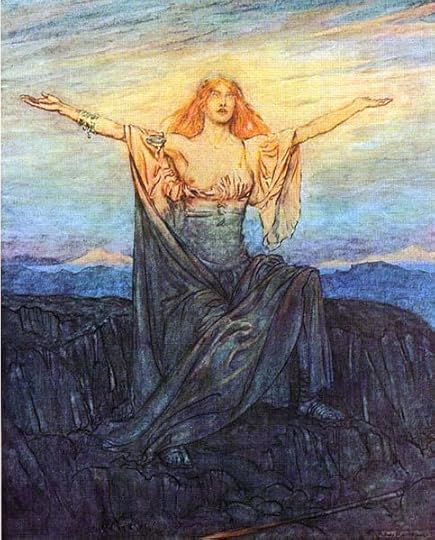

Brünnhilde awakens

In his masterpiece, Wagner synthesised stories from across the Old Norse-Icelandic collection of poems known as the Poetic Edda. He had long been mulling over an opera based on the German epic, Das Nibelungenlied, but he realised that he needed more material and more inspiration. Wagner knew where he might find it: “I must study these Old Norse eddic poems of yours; they are far more profound than our medieval poems,” he remarked to the Danish composer Niels Gade in 1846. In 1851, when he got his hands on Karl Simrock’s edition of the Poetic Edda, Wagner finally saw how to develop his ideas about the death of Siegfried into a cycle and he also discovered the rhythms of traditional Germanic alliterative verse which he would use for his libretto.

The first poem of the Edda, “The Seeress’s Prophecy” selectively narrates the history of the universe, from Creation, when the world rises up out of the sea, to Ragna rök or Götterdämmerung, when the world ends in ice and fire. Wagner starts his opera about halfway through “The Seeress’s Prophecy”, where the Seeress allusively notes how moral corruption comes among the gods when they betray the giant who rebuilt the walls of Asgard for them. Interwoven in Das Rheingold with the gods’ bad faith is the tale of the Rheingold from the later heroic poems: the cursed treasure-hoard which brings strife in its wake, epitomised by the ring Andvari’s Jewel.

Wagner used a prose retelling of the heroic legends associated with Sigmund for Die Walküre, themes known to the poets of the Edda, but not recounted by them. Siegfried takes up the Edda once again with the troubled relationship of the young hero and Mime (Regin in Norse), the dragon fight, and the meeting with the valkyrie. In the Edda, Sigurd learns wisdom from the valkyrie: how to use runic magic for healing and protection, to ensure a calm sea, and to make fetters fall from the feet. The deliriously joyful union of hero and valkyrie is lost in a gap in the manuscript. When the story resumes, we are already deep into the betrayal and heartbreak caused by Sigurd’s forgetfulness — thanks to the magic potion given him at his in-law’s court — and the destruction of that sublime love through the hero’s innocence and Brynhild’s vengefulness.

Brünnhilde on the horse Grane rides onto Siegfried’s funeral pyre.

Wagner follows German tradition for Siegfried’s death: stabbed in the back beside the Rhine, his one vulnerable spot revealed by Brünnhilde. The Poetic Edda gives fuller weight to the feelings of Sigurd’s wife. The two queens quarrel and Gudrun flaunts her knowledge of the truth: it was Sigurd who crossed the flame-wall to claim Brynhild for Gunnar. Wagner understood how the story of Siegfried and Brünnhilde must end, in immolation and the destruction of the compromised order of the gods. The world ends in fire as the waters rise and the Rhine overflows. When the ring returns to the Rhinemaidens, the circle is completed, ready — as the “Seeress’s Prophecy” suggests — for rebirth.

It’s 200 years since Wagner’s birth, 137 years since the Ring Cycle was performed for the first time in Bayreuth and shortly afterwards in London. More than any other artist before or since, Wagner saw to the heart of eddic themes, saw the inevitable compromises and double-dealing that divinity must make to accommodate desire and law. He saw how passion transfigures and destroys, how treasure and the torsions of power eat into the soul and bring tragedy to birth. He ended his cycle with Ragna rök and the deaths of his protagonists; he did not wish to follow Gudrun through the terrible cycles of marriage and vengeance that follow the loss of her first husband. The Poetic Edda manuscript ends with the last stand of Gudrun’s only remaining sons, sword in hands perched on the corpses of the slain like eagles on a bough. They die avenging Sigurd’s daughter Svanhildr, whose white-gold hair was, on her husband’s orders, trampled into the mud by wild horses.

Josef Hoffmann, 1876, closing scene of Das Rheingold. The gods make ready to enter Walhall

In this anniversary year, Wagner’s music is played, staged and celebrated. Wagner’s understanding of the mythic and the heroic, of the timeless patterns in human existence, sharply delineated in the powerful lines of the poems which inspired him, invites a re-reading of the Poetic Edda, not only to admire how Wagner adapted what he found there, but to step out across Bifröst, the rainbow bridge that leads to Valhalla, and to immerse ourselves in the stark, uncompromising, yet glorious, imaginative universe where the gods, giants, and heroes walk.Carolyne Larrington is Supernumerary Fellow and Tutor in medieval English Literature at St John’s College, Oxford. She has published extensively on Old Norse mythological and heroic poetry. Her translation of The Poetic Edda is available from Oxford World’s Classics.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Brünnhilde wakes up and greets the day and Siegfried [public domain]. By Arthur Rackham, via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Brünnhilde on Grane leaps onto the funeral pyre of Siegfried [public domain]. By Arthur Rackham, via Wikimedia Commons. (3) Outside the Hall of the Gibichungs [public domain]. By Josef Hoffmann, via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Poetic Edda and Wagner’s Ring Cycle appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhitman todayA National Poetry Month reading list from Oxford World’s ClassicsGimme Shelter: De Quincey on Drugs

Related StoriesWhitman todayA National Poetry Month reading list from Oxford World’s ClassicsGimme Shelter: De Quincey on Drugs

What have we learned from modern wars?

By Richard English

War remains arguably the greatest threat that we face as a species. It also remains an area of activity in which we still tend to get far too many things wrong. For there’s a depressing disjunction between what we very often assume, think, expect, and claim about modern war, and its actual historical reality when carefully assessed. The alleged causes for wars beginning and ending often fail to match the actual reasons behind these developments; meanwhile, the things making people actually fight in such wars often differ both from the ostensible claims made by or about such warriors, and also from the actual reasons for the wars occurring in any case. Much of what we anticipate, celebrate, commemorate, and remember regarding the experience and achievements of modern war bears only partially overlapping relation to historical reality, and wars’ actual achievements greatly diverge from both the publicly articulated and the actual aims and justifications behind their initial eruption. Again – and most depressingly – most of our attempts to set out prophylactic measures and structures against modern war have seemed (and continue to appear) frequently doomed to blood-spattered failure.

Consider some of the conflicts likely to dominate memory of the first years of the twenty-first century. The Iraq War which began in 2003 was publicly justified on various grounds, including the false claim that Saddam Hussein had played a role in generating the 9/11 atrocity; the mistaken assertion that he possessed a certain array of Weapons of Mass Destruction and thus represented an immediate threat to the West; and the claim that his regime was vile and oppressive — itself a reasonable point, but one undermined by the fact that the USA and its allies have tolerated in the past, and continue to tolerate in the present, equally or more despicable regimes remaining in power when political judgment seems to recommend such an approach.

In the event, the early phase of the Iraq War saw a dramatic and impressive military victory for the US-led campaign. But this was followed by a post-war phase of appalling violence, ill-considered policy, political chaos, and hubristic assertions about victory. The casting of the Iraq War as part of a War on Terror made it even less persuasive as a venture. There were, perhaps, some sound reasons for wanting to depose Saddam Hussein (among them, the view that he indeed did want to possess WMDs, and that it would be better to depose him before he had them than after he had acquired them). But in terms of terrorism, what Iraq did was to intensify the desire of some people to attack Western forces – whether in Iraq itself or in Western countries. And it is likely that, in a hundred years’ time, very few people will be able to name even a handful of victims of early-twenty-first-century al-Qaida terrorism, but that many people will remember the lesser nastiness of Abu Ghraib prison, and the unnecessary discrediting of the USA as a consequence.

My suspicion is that we will fail to learn very much, in terms of future political planning, from these mistakes and difficulties. Has the USA and UK sounded much more persuasive, and seemed more sure-footed, in its reaction to the varied conflicts emerging recently in Libya, Syria, or Egypt? Did the ludicrous over-reaction of the authorities in Boston to the terrible (but ultimately trivial, in terms of its global, political weight) marathon bombing suggest that we have moved forward in how we respond to what tends to be a very small terrorist threat?

It is possible, as scholars such as Harvard’s Steven Pinker have powerfully argued, that we are becoming less violent overall as a species, in terms of the percentage likelihood of members of the human race actually experiencing violent actions. It is also true, however, that our tendency to misdiagnose causes, to anticipate futures which do not have much chance in practice of occurring, to present dubious justifications for naively-sanctioned campaigns of warfare, and to over-react to small provocations by terrorist groups and individuals, might yet produce certain explosive conflicts which carry with them truly devastating consequences — consequences likely to endure far longer than the short-term and unhistorical thinking which brought them into being.

Richard English is Bishop Wardlaw Professor of Politics, and Director of the Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence at the University of St Andrews. Modern War: A Very Short Introduction publishes in July 2013.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or US Independence Day author Q&A: part three

July 18, 2013

Glaucoma: not just a disease of adults

Glaucoma is a potentially blinding disease where degeneration of the optic nerve leads to progressive vision loss. In the United States, it is estimated that 2.2 million suffer from glaucoma. The eye is constantly producing aqueous (fluid) that in a normal person’s eye is drained out via a structure called the trabecular meshwork. In people with glaucoma, this drain doesn’t work, resulting in high intraocular pressure and vision loss.

Generally, glaucoma is thought of as an “old person’s” disease. Although rare, glaucoma can affect the pediatric population, often with different signs and symptoms than present in an adult population. Congenital/infantile glaucoma occurs in 1 in every 10,000 births in the United States, and most cases are diagnosed within the first year. These children often have large eyes with cloudy corneas, due to stretching of the eye to accommodate the extra fluid. Excessive tearing and sensitivity to light (manifested by hiding from bright light or squeezing of the eyelids) is also common.

Juvenile glaucoma can be diagnosed at any time during childhood. These children may not have the anatomic abnormalities described above but will be better able to communicate discomfort and other symptoms of glaucoma. Sensitivity to light, vision loss, difficulty adjusting to the dark, headaches or eye pain, frequent blinking or squeezing of the eyelids, and consistent red eyes are some hallmarks of the disease.

Secondary glaucomas can also occur in children. These glaucomas are associated with systemic medical conditions (i.e. Sturge-Weber syndrome, Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome, Marfan syndrome), ocular abnormalities (aniridia and various other congenital conditions), trauma, or after surgery (cataract extraction or due to treatment with steroids).

Early diagnosis and treatment are the crucial to preserve as much vision as possible. In young children, an exam under anesthesia in a hospital setting may be done. Older children can be examined in the office. Follow-up is just as crucial as the initial diagnostic exam to monitor changes in vision and other eye functions. Treatment may include medications or potentially surgery depending on the cause of the glaucoma, but with treatment children can go on to live happy, full lives with good vision.

At the World Glaucoma Congress in Vancouver in July, my departmental colleague Dr. Lauren Blieden and I are gladly meeting with other pediatric glaucoma specialists to develop a consensus on terminology and guidelines for pediatric glaucomas. The goal of this meeting is to provide consistent definitions and standards for treatment so that pediatric glaucoma patients can be effectively helped and the disease researched thoroughly.

Dr. Robert M. Feldman is Richard S. Ruiz, MD Distinguished University Professor and Chairman of the Ruiz Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Science at The University of Texas Medical School in Houston. Along with his departmental colleague Dr. Nicholas P. Bell, he is editor and contributor to Complications of Glaucoma Surgery, which discusses both common and rare complications of glaucoma surgery and how to recognize, prevent, and manage them.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or Head Start: Management Issues

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers