Oxford University Press's Blog, page 920

July 26, 2013

Experiencing art: it’s a whole-brain issue, stupid!

We love art. We put it on our walls, we admire it at museums and on others’ walls, and if we’re inspired, we may even create it. Philosophers, historians, critics, and scientists have bandied about the reasons why we enjoy creating and beholding art, and each has offered important and interesting perspectives. Recently, brain scientists have joined the conversation, as it is now possible to put someone in a MRI scanner and assess brain activity in response to viewing art or even creating it (e.g. jazz improvisation). With such exciting new prospects, budding intellectual fields such as “neuroaesthetics,” “neuroarthistory,” and “neurocinematics” have cropped up.

I applaud these attempts to integrate science with the humanities. In the end, art is an experience, and as such neuroscience may be useful in explaining the biological processes underlying it. One feature that is often ignored, however, is the role that knowledge plays. We never experience art with naïve eyes. Rather we bring with us a set of preconceived notions in the form of our cultural background, personal knowledge, and even knowledge about art itself. In large measure, what we like is based on what we know. When we accept the fact that our art experience depends on a confluence of sensations, knowledge, and feelings, it becomes clear that there is no “art center” in the brain. Instead, when we confront art, we essentially co-opt the multitude of brain regions we use in everyday interactions with the world. Thus, with respect to “neuroaesthetics,” the question “How do we experience art?” can be simply answered as: “It’s a whole-brain issue, stupid!”

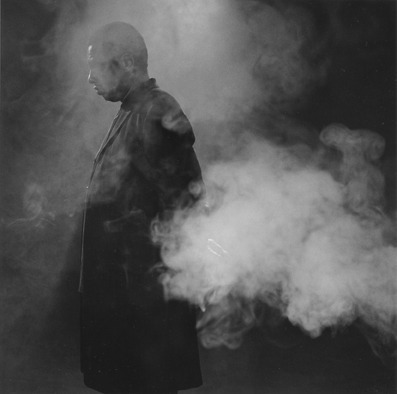

Cloudscape, 2004 by Lorna Simpson. All rights reserved.

We can, however, go further in developing a science of aesthetics as the brain is not a homogenous blob of neurons. Different regions serve different functions, and over the past two decades, neuroimaging research has advanced our understanding of the biological bases of many mental functions to the point that it has completely revolutionized psychological science. What has become clear is that for a thorough analysis of any complex mental process, including our appreciation of art, we must characterize how neural processes interact in addition to where in the brain they occur. With respect to art, I suggest that when our sensory, conceptual, and emotional parts of our brain are all coordinated and extremely aroused—say 11 on a scale of 10—we experience that “wow” feeling, as one might have while standing in front of Michelangelo’s David or Van Gogh’s Starry Night Over the Rhone.

On a recent visit to Paris, I had several “wow” moments at the Jeu de Paume gallery where a retrospective of Lorna Simpson works is being held. I was familiar with Simpson’s photographic works, though primarily through book reproductions. At the exhibition, her photographs come alive as they are large and lusciously detailed. Even more provocative were her video installations, particularly Cloudscape, 2004, in which a man stands and whistles a haunting melody while an ethereal haze blows around him. Half way through the video, the scene shifts subtly, which makes one consider the conceptual underpinnings of the work. I won’t reveal the nature of the change, but one can view it at Lorna Simpson’s website.

Whenever we experience a work of art, we must consider how it stimulates our sensations, thoughts, and feelings. Yet you might ask, can the firing of neurons really tell us about the way we appreciate a Leonardo, Picasso, or Simpson? Do we even know what an “art” experience is? There are certainly limits to current brain imaging technology, and there may even be inherent limits in the degree to which science can contribute to our understanding of art and aesthetics. Yet by considering a multidisciplinary approach that fosters interactions among philosophers, historians, scientists, and artists themselves, we may be able to gain a better understanding of the joy of art. In addition, by evaluating such a universal and distinctly human practice, art may tell us more about brain than the other way around.

Arthur Shimamura is Professor of Psychology at the University of California, Berkeley and faculty member of the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute. He was awarded a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship in 2008 to study links between art, mind, and brain. His new book is Experiencing Art: In the Brain of the Beholder (Oxford University Press, 2013). He is also editor of Psychocinematics: Exploring Cognition at the Movies (Oxford University Press, 2013). Further musings can be found on his Psychocinematics blog, or his previous OUPblog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only brain sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Experiencing art: it’s a whole-brain issue, stupid! appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPsychocinematics: discovering the magic of moviesThese days do we really need a Man of Steel?Songs of summer, OUP style

Related StoriesPsychocinematics: discovering the magic of moviesThese days do we really need a Man of Steel?Songs of summer, OUP style

Songs of summer, OUP style

It’s finally summer — the perfect time to spend with family and friends, enjoy the weather, gardens and parks, and create fond memories. What better way to create those summer memories than have our favorite songs playing in the background? This summer we asked different members of the Oxford University Press (OUP) staff to share their favorite summer songs and the reason why they like them so much. The result was an interesting playlist of songs from different genres, so take a look and see what our OUP staff have to say about their favorite songs.

Billy Joel’s “Scenes From An Italian Restaurant”

“The images in this song always make me think of summer — friends reuniting, sharing a bottle of red/white/rosé at an outdoor table, dancing to jukebox music. In particular, Brenda and Eddie driving around with the top down, music blasting, as they head to their hometown diner, makes me smile when I think of all the summers in high school when my friends and I did the same.”

– Georgia Mierswa, Marketing Associate, Digital

Click here to view the embedded video.

Frank Sinatra’s “Summer Wind”

“… for when the sun is setting, the air is cooling, and you’re still at the beach with absolutely no intention to leave.”

– Jeff Yerger, Marketing Assistant, Higher Education Group

Click here to view the embedded video.

Don Henley’s “The Boys of Summer”

“I’m pretty sure every punk band there was did a cover of this when I was in high school, and I almost blew out my car stereo once blasting it. The name does half of the work, but ‘The Boys of Summer’ will always be my default summer song: laid back and intense at the same time.”

– Kate Pais, Marketing Assistant, Academic/Trade

Click here to view the embedded video.

Daft Punk’s “Get Lucky”

“My summers are usually spent in the car a lot—travelling to see friends and family, or heading to the Jersey shore. Thus, a good summer song to me is a good one to dance to in the car. My favorite summer song changes every year so this summer, it’s Daft Punk’s ‘Get Lucky’. Perfect for turning the volume way up and shoulder dancing to.”

– Alyssa Bender, Marketing Associate, Academic/Trade and Bibles divisions

Click here to view the embedded video.

Colleen Green’s “Only One”

“I’ve been really into Colleen Green’s new record Sock It To Me lately. She takes saccharine, girl-group melodies and mixes them with incredibly simplistic drum machines and punk instrumentation; the result is totally unique.”

– Owen Keiter, Publicity Assistant

Click here to view the embedded video.

“Sumer Is Icumen In” (Anon. c. 1260)

“This was a favorite song among all medieval beachgoers. Its six-part melodic counterpoint indicates that these sunbathers were quite the vocal masters. I like it because it has inspired parodies by Ezra Pound, Vernon Duke, and the Fugs, among many others.“

– Richard Carlin, Executive Editor, Music and Art, Higher Education

Click here to view the embedded video.

“Ein heisser Sommer wie wunderbar 1968″

“I’ve always enjoyed the titular song from the 1968 East German beach film musical Heisser Sommer, or Hot Summer. It’s so terrible that it’s actually quite good, a moment of unexpected camp in East German cinema.”

– Norman Hirschy, Editor, Academic Editorial

Click here to view the embedded video.

Harry Nilsson’s “Coconut”

“The lyrics border on the ridiculous yet the song is catchy and enduring in that ‘hard to get out of your head’ way.”

– Coleen Hatrick, Senior Publicist

Click here to view the embedded video.

Mean Lady’s “Lonely”

“This is a fantastic song all about waiting to be back together with someone after a long time apart. It’s an awesome song year-round, but it’s great to blast going into summer after a long winter.”

– Ryan John, Summer Intern, Music Editorial

Click here to view the embedded video.

The Phenomenal Handclap Band’s “15 to 20″

“I’ve seen this band twice, once at Southpaw in Park Slope with my friend Steffen who now lives in Florida and then later at Le Poussin Rouge in the West Village after the first album came out. Both shows were in the summer and both times they were awesome. This is their hit single from the first album. The video is also great, an extraordinary endeavor of 8 short films featuring each member of the band weaved into an NYC heist story.”

– Jeremy Wang-Iverson, Senior Publicist

Click here to view the embedded video.

Japandroids’ “The House That Heaven Built”

“Nothing like driving down the Garden State Parkway with your friends, rolling the windows down to feel the ocean breeze, and singing along to this anthem at the top of your lungs.”

– Jeff Yerger, Marketing Assistant, Higher Education Group

Click here to view the embedded video.

Blur’s “Parklife”

“One of my fondest summer-related memories is being a camp counselor with my best friend Kelle for three weeks down in Ellenton, FL. Every night I would listen to ‘Parklife’ by Blur on my Walkman to help me fall asleep after long days covered in sweat and teaching kids all sorts of crazy games. The title track still brings out the fancy-free 19-year-old in me.”

– Meg Wilhoite, Assistant Editor, Grove Music/Oxford Music Online

Click here to view the embedded video.

Foster the People’s “Pumped up Kicks”

“I did some travelling a couple of years ago and this song was the soundtrack to my trip. Whenever I hear the start of the song, it immediately reminds me of driving around California in the sunshine! Definitely my favourite summer song.”

– Annie Leyman, Marketing Executive, Academic Music Books (UK)

Click here to view the embedded video.

Your Oxford Summer Playlist:

Natasha Zaman is an intern at Oxford University Press in New York this summer.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Songs of summer, OUP style appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA birthday gift of lullabies for Baby CambridgeKammerer, Carr, and an early Beat tragedySummers with George Balanchine

Related StoriesA birthday gift of lullabies for Baby CambridgeKammerer, Carr, and an early Beat tragedySummers with George Balanchine

Kammerer, Carr, and an early Beat tragedy

Following last year’s release of On the Road, adapted by director Walter Salles from the legendary Jack Kerouac novel published in 1957, two more Beat Generation movies are on the way. Big Sur, a November release directed by Michael Polish, stars Jean-Marc Barr, Stana Katic, Anthony Edwards, and Radha Mitchell in a story based on Kerouac’s 1962 novel about his efforts to shake off inner demons at an isolated cabin near the California coast. Kill Your Darlings, arriving in October, marks the feature-film debut of John Krokidas, who directed and co-wrote it. It’s a tale of madness and mayhem centering on an actual tragedy that occurred in 1944, involving two friends of the young Beats during their Columbia University days. Lucien Carr is an emotionally insecure student caught in a turbulent relationship with David Kammerer, an older man whose erotic obsession with Carr leads to his own death. The cast includes Michael C. Hall as Kammerer, Dane DeHaan as Carr, Daniel Radcliffe as Allen Ginsberg, and Jack Huston as Kerouac.

The real-life episode is described in this excerpt from David Sterritt’s The Beats: A Very Short Introduction.

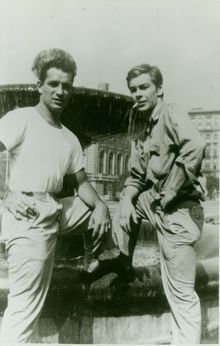

Jack Kerouac and Lucien Carr

In 1944 an event took place that troubled Kerouac as well as Burroughs and Ginsberg, helping to catalyze the unhappy outlook on life that characterizes some early Beat writing. The main players in this tragedy were Lucien Carr and David Kammerer.

Kammerer had been a friend of Burroughs since childhood, and in 1933 they had visited Europe together. Burroughs found him “always very funny, the veritable life of the party, and completely without any middle-class morality.” Kammerer became an instructor at Washington University in St. Louis, and he also ran a youth group that Carr joined while still a boy. By all reports, Kammerer was infatuated and then obsessed with Carr, a well-to- do Columbia student whom Kerouac describes in Vanity of Duluoz as a young man of “fantastic male beauty . . . actually like Oscar Wilde’s model male heroes.”

They traveled to Mexico together in 1940, with permission from Carr’s mother. After finding some of Kammerer’s letters, however, the shocked mother worked hard to keep them apart. Kammerer then followed Carr to each of several schools he enrolled in. Carr evidently had no interest in a homosexual relationship, but he appeared to enjoy the attention his older friend lavished on him, especially when the former English teacher ghost-wrote his college homework. Carr transferred to Columbia in 1943, with Kammerer and Burroughs trailing along. Soon Kammerer met Ginsberg and Kerouac, becoming part of the fledgling Beat circle.

Kammerer and Carr were an odd couple with a penchant for trouble, ranging from childish horseplay to deep emotional crises. An instance of the latter arose in 1943, when Carr landed in a mental institution after an apparent suicide attempt. The already unstable mood of their friendship took another downturn when Carr fell in love with a young woman. Kammerer stalked Carr on some days and refused to see him on others. The tension between them finally exploded on a summer night in 1944. Kammerer had been hunting for Carr that evening, eventually finding him drunk in the West End, a bar in the Columbia neighborhood. They left the bar together, and later in the night they came to blows on a hillside not far away.

According to Ted Morgan’s account, Carr then went to the apartment that Burroughs was sharing with Kerouac and Edie Parker, telling them what had happened next and throwing Kammerer’s eyeglasses onto a table. “I just got rid of the old man,” Carr said. “I stabbed him in the heart with my Boy Scout knife.” Kerouac asked why. Carr answered, “He jumped me. He said I love you and all that stuff, and couldn’t live without me.” He added that Kammerer had threatened to kill both him and his girlfriend. After stabbing Kammerer, the young man had tied stones onto the body’s arms and legs, using strips torn from the shirt. Then he had pushed Kammerer’s body into the Hudson River, where it hovered until Carr waded in up to his chin and pushed it into the current.

Burroughs advised Carr to turn himself in and make a plea of self-defense. Taking a very different tack, Kerouac went with Carr to the scene of the crime, where Carr buried the incriminating glasses and dropped his knife into a sewer. Then they went for drinks and watched a movie. Two days later, Carr took Burroughs’s advice and surrendered to the police, reaching a plea bargain that reduced a possible twenty-year sentence to two years of actual time served, and placed him in a reformatory rather than a penitentiary. He left the reformatory a changed man, so eager for a conventional life that he complained when Ginsberg later dedicated “Howl” to him. Burroughs and Kerouac, considered material witnesses to the crime, were arrested for not reporting it. Burroughs’s family bailed him out immediately. Kerouac’s humiliated father refused to follow suit, so Parker put up the money on the condition that Kerouac marry her. He did. Ginsberg was not hauled into the legal system, but he was deeply shocked by what had happened, fearing it was a horrific consequence of the morbidly tinged romanticism in which he and his friends had indulged. He soon started a novel, The Bloodsong, based on the incident. Kerouac wrote about the tragedy in I Wish I Were You, a novella that also went unfinished. He later wove the affair into his first novel, The Town and the City, and his last, Vanity of Duluoz. In its immediate aftermath, Kerouac and Burroughs used it as the basis for their attempt at a joint novel, And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tank, writing under pseudonyms and borrowing their title from a news report about a circus fire. They found an agent, but nobody would publish it.

David Sterritt is a film professor at Columbia University and the Maryland Institute College of Art, and professor emeritus at Long Island University. A noted critic, author, and scholar, he is chair of the National Society of Film Critics and chief book critic of Film Quarterly, and was for many years the film critic for The Christian Science Monitor. His books include The Beats: A Very Short Introduction, Mad to Be Saved: The Beats, the ’50s, and Film and Screening the Beats: Media Culture and the Beat Sensibility, and he serves on the editorial board of the Journal of Beat Studies. Read his previous blog post: “Jack Kerouac: On and Off the Road”

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Jack Kerouac and Lucien Carr (right), late Spring 1944, Columbia College Campus. From Allenginsberg.org used for the purposes of illustration via Wikimedia Commons

The post Kammerer, Carr, and an early Beat tragedy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat have we learned from modern wars?Nelson Mandela: a precursor to Barack ObamaUS Independence Day author Q&A: part four

Related StoriesWhat have we learned from modern wars?Nelson Mandela: a precursor to Barack ObamaUS Independence Day author Q&A: part four

July 25, 2013

Fit for a (future) king: George, Alexander, and Louis

It’s not been easy to avoid news that the duke and duchess of Cambridge have had their first child, that the baby is a boy, and that he’s been named George Alexander Louis. The media have hailed this choice as ‘traditional’. Tradition in this case is the Oxford English Dictionary’s fourth sense: ‘fact of being handed down, from one to another, or from generation to generation.’ When, and with whom, did that tradition begin? The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography can help identify the origins and the nature of what may be being communicated with those three names. In doing so, it also reminds us of some unexpected associations with historical forebears who answered to George, Alexander, or Louis.

George …

George I of Great Britain by Sir Godfrey Kneller, 1714.

Contrary to popular expectations, the use of the name George by six British kings can’t be attributed directly to St George’s position as England’s patron saint. Rather, the prominence of the name among British royalty derives from its popularity among German ruling families. August 2014 will see the 300th anniversary of the accession of the first King George as monarch of a recently created ‘Great Britain’. The names given this week to the infant prince appear to commemorate this, George I ’s forenames being George Louis. In his native German he was Georg Ludwig, and the usual English form in the king’s lifetime was George Lewis. In the early eighteenth century, the name Louis was associated in Britain with the country’s recent enemy, Louis XIV of France, and was suppressed at George I’s accession.George I was the first of four successive monarchs with this name: eighteenth-century Britain is, of course ‘Georgian’ (or sometimes Hanoverian) Britain. He and his son George II epitomized a practical form of kingship, proud of its background in efficient soldiering. George III and George IV are often remembered negatively but both were patrons of science and the arts with influence over agriculture, architecture, and painting. Much of the prospective built inheritance of the infant Prince George—notably at Windsor Castle and Buckingham Palace—is the legacy of these two monarchs. All four Georges exercised substantial political influence. By contrast, their descendants, George V and George VI—monarchs from the early to mid-twentieth century—experienced the limits of a parliamentary monarchy in the age of universal suffrage. These diminishing political responsibilities were largely established through the responses of Georges V and VI to political and dynastic crises in this period.

Georges III and IV never saw military service, whereas V and VI were both active naval officers. From the mid-eighteenth to the early nineteenth century, the British monarchy’s role as military leader was delegated to members of the family outside the direct line of succession. Most prominent of these was the first Prince George of Cambridge (1819-1904), now better remembered as the second duke of Cambridge. He was a grandson of George III, served in the Crimean war, and became the army’s commander-in-chief in 1856. The duke’s own reforms and personal popularity were overtaken by political demands; from 1870 his position became subordinate to the Secretary of State for War, a shift indicative of the weakening of the crown’s independence. The second duke’s public and private life expressed a duality of a kind that today’s Prince George of Cambridge is very unlikely to experience. While a defender of royal authority, the second duke was one of many princes in the period to marry someone who was not his social equal creating a union of which Queen Victoria could not approve; consequently the duke’s marriage to the actress Louisa Fairbrother was declared void by the terms of the 1772 Royal Marriages Act.

All the British kings names George have reigned over multiple territories and united several crowns in one person. It is impossible to establish what form late twenty-first century kingship will take, but it’s very likely that the Commonwealth of Nations, successor of the British empire, will continue to play a part in the formation of Prince George’s sense of royal duty. It seems probable that the number of Commonwealth countries which retain the British monarch as head of state will diminish, but the prince has namesakes in the history of one of the other Commonwealth monarchies. Siaosi, the Tongan form of George, appears frequently among the names of the Tongan royal family, beginning with the first king of Tonga, Siaosi Taufa’ahau Tupou I.

Alexander …

Alexander I of Scotland from History of Scottish seals by Walter de Gray Birch.

The royal use of Alexander falls into two phases—the first being its use by medieval Scottish kings. The naming of Alexander I was perhaps intended to associate Scottish kingship with mainstream western European Christendom, commemorating Pope Alexander II, pontiff between 1061 and 1073. As a consolidator of royal authority in Scotland, Alexander I was overshadowed by his successor David I, but he was remembered in the names of his thirteenth-century descendants Alexander II and Alexander III—both astute protectors of the Scottish kingdom against English claims to overlordship.Under the House of Stewart, the name Alexander was borne by younger sons whose record as servants of the king was erratic at best. Alexander Stewart, earl of Buchan, ‘the Wolf of Badenoch’, ruled much of northern Scotland notionally under his father Robert II in the 1370s and ‘80s. A century later, Alexander Stewart, duke of Albany, sought to dominate affairs either through his elder brother, James III, or in opposition to him; for a period in 1482 he called himself ‘Allexander, king of Scotlande’. The name Alexander might have been redeemed by James IV’s illegitimate son Alexander Stewart, archbishop-designate of St Andrews, had he not been killed alongside his father at Flodden in 1513.

The name resurfaced in the nineteenth century in part to honour Tsar Alexander I of Russia, as in the case of Queen Victoria’s first name, Alexandrina. More obviously her daughter-in-law Alexandra, consort of Edward VII, established Alexandra and by extension Alexander as part of modern royal naming patterns. Alexandra is also the middle name of Elizabeth II who was born a year after Queen Alexandra’s death. The conventional military career for male members of the extended royal family (as experienced by Georges V and VI) was also followed by Prince Alexander of Teck, nephew of George, second duke of Cambridge. After the First World War (during which, in 1917, he became Alexander Cambridge, earl of Athlone) the prince became known for his philanthropic work and also served as governor-general of South Africa (1924-39) and Canada (1940-6).

Louis …

The conjunction of the names Alexander and Louis takes us back to thirteenth century, and seems to commemorate an almost-successful change of dynasty in England in 1215-16. King John’s repudiation of Magna Carta led his opponents to offer the throne to Louis, son of Philippe II of France. The strength of the opposition to John was such that Alexander II of Scotland was able to proceed to Canterbury to swear homage to Louis for his English territories. John’s death in 1216 made it easier for loyalists to the Angevin dynasty to secure their position and that of John’s son Henry III, then still a child. But the alliance of (the Scottish) Alexander and (the French) Louis is a reminder that the narrative of nation-building—often conveyed through the medium of royal history—was not inevitable and obscures telling realities.

As already seen with George I, ‘Louis’ had currency in the Hanoverian dynasty. When George I was named it had solid protestant associations through his maternal uncle Charles Lewis, elector palatine of the Rhine, though the ‘universal monarchy’ of the Catholic Louis XIV also loomed large. After George II’s daughter Louisa the name did not appear again until the mid-nineteenth century: Princess Louise, duchess of Argyll being one such example. A century on, the greatest influence on the modern revival of the name Louis was Louis Mountbatten, first Earl Mountbatten of Burma, ‘honorary grandfather’ to the baby’s grandfather Prince Charles and indefatigable manager of imperial twilight in India and at home. His name came, in turn, from his father, Prince Louis of Battenberg (Louis Mountbatten, first marquess of Milford Haven)—for whom it served to advertise his kinship to the grand dukes of Hesse and by Rhine.

Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten. Photo by

Cecil Beaton. Imperial War Museum

George Alexander Louis might seem a modest selection of names compared to the seven forenames given in 1894 to the future Edward VIII (Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David; plus the boyhood nickname ‘Sardine’). The choice made for the young Prince George connects him to royal forebears who began the monarchy’s transition from late imperialism to the modern United Kingdom. Yet it also brings reminders of aspects of medieval kingship, and the long close association of British monarchs with continental Europe. How these ideas inform the life of the young Prince George of Cambridge is for him to experience and for us—as far as we are allowed—to observe.

Dr Matthew Kilburn is an associate research editor of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. In addition to writing and lecturing on the history of the British monarchy, he is also a contributor to the forthcoming History of Oxford University Press.

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography is the national record of men and women who have shaped British history and culture, worldwide, from the Romans to the 21st century. In addition to 58,700 life stories, the ODNB offers a free, twice monthly biography podcast with over 185 life stories now available. You can also sign up for Life of the Day, a topical biography delivered to your inbox, or follow @odnb on Twitter for people in the news. The Oxford DNB is freely available via public libraries across the UK. Libraries offer ‘remote access’ allowing members to log-on to the complete dictionary, for free, from home (or any other computer) twenty-four hours a day.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: All images public domain via Wikimedia Commons: (1) George I, (2) Alexander I, (3) Lord Mountbatten.

The post appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOn ‘work ethic’Understanding history through biography

Related StoriesOn ‘work ethic’Understanding history through biography

Recent advances and new challenges in managing pain

“The aim of the wise is not to secure pleasure, but to avoid pain.” –Aristotle

Pain is one of the most feared symptoms whether it is after surgery, in the context of chronic disease, or related to cancer. Around 18% of people will be affected by moderate to severe chronic pain at some point in their life, with chronic pain having as big a negative impact on quality of life as severe heart disease or a major mental health problem. Five years ago we dedicated a whole postgraduate issue to pain medicine, based on the inaugural meeting of the Faculty of Pain Medicine of the Royal College of Anaesthetists, London. As the number of patients suffering from chronic pain continues to increase, with our aging population and improved longevity, so does the need to improve our understanding and management of pain.

A first step in the successful management of any pain problem is proper assessment. The medical school teaching of “history and examination” underpins this in the clinical setting, and in the research setting, this is perhaps equally as important. It is widely acknowledged that what have appeared to be good animal models of different chronic pain syndromes have often failed to translate into clinical practice. Some of the reasons for this failure include how we might better align pain assessment in the laboratory with the clinical syndromes being studied. By only focussing on the sensory aspects of pain, the complexities of pain will be missed, and the dynamic interplay between mood, thoughts and sensations that help to define the pain experience will be lost. While there are limitations to laboratory models, they have delivered some successful treatments to the clinic: future success may be improved by a closer conversation between clinicians and scientists.

Irene Tracey‘s group in Oxford is world-leading in the use of neuroimaging techniques to advance our understanding of pain. We intuitively know that personality and expectation will influence our pain experience; it is fascinating to see how there are discrete neural mechanisms that explain this. The basis of the placebo response has been studied, with it becoming clear that this powerful tool may be used positively. What a bonus for economically stressed healthcare systems with restricted drug budgets if we can utilise the placebo response to minimise pain! The quote from Hippocrates — “It is more important to know what sort of person has a disease than to know what sort of disease a person has” — may apply very particularly to the management of pain.

For some time, it has been suspected by many that there are differences between men and women, with suspicion that they may even come from different planets on occasion (Mars or Venus?). There are myths and sometimes contradictory literature on the differences in pain sensitivity and response to analgesics between men and women. This area still remains somewhat murky, with a likely contribution from genetics, hormones, and psychosocial factors. The suggestion for sex-specific treatments in the future is interesting — perhaps “man flu” needs stronger drugs!

While clinical trial design may seem like a somewhat dry topic, those of us in clinical practice recognise the mismatch between what we see in day to day clinical practice the published literature: the potential of having missed what might be very effective treatments for particular subgroups of patients, or how complex analysis techniques may significantly over-estimate how effective a treatment is and skew the evidence base. Other topical areas include pain management in the elderly, challenges of cancer-treatment related pain, chronic pain after surgery, and the effect of opioids on the immune system. I hope for a stimulating update in the field of pain medicine and to emphasise the importance of ongoing close collaboration between multidisciplinary groups, from basic scientists, to epidemiologists, neuroimagers, and psychologists, in order to improve the lot of our patients and reduce the burden of suffering from poorly managed pain.

“When we are suddenly released from an acute absorbing bodily pain, our heart and senses leap out in new freedom; we think even the noise of streets harmonious, and are ready to hug the tradesman who is wrapping up our change.” –George Eliot

Lesley Colvin is the Editor of the British Journal of Anaesthesia (BJA). This year’s postgraduate issue of BJA is dedicated to the challenges that face anaesthetists, and the new advances that may help anaesthetists to improve the experience of patients who have the misfortune to suffer pain. When selecting the reviews for this issue, Dave Rowbotham (guest editor) and Lesley Colvin aimed to have a broad range of articles from exciting new basics science developments, through to the use of neuroimaging techniques to tease out the complexities of pain perception and its modulation, as well as broader societal aspects of pain and how we manage it. This issue also presents a first: a collaboration with the British Pain Society to publish an expert commentary alongside two of their new Pain Patient Pathways, on particularly challenging and common pain syndromes: low back pain and neuropathic pain. It is hoped that these clearly laid out pathways can be adapted for use in a variety of healthcare systems to improve management for these patients.

Founded in 1923, one year after the first anaesthetic journal was published by the International Anaesthesia Research Society, British Journal of Anaesthesia remains the oldest and largest independent journal of anaesthesia. It became the Journal of The College of Anaesthetists in 1990. The College was granted a Royal Charter in 1992. Since April 2013, the BJA has also been the official Journal of the College of Anaesthetists of Ireland and members of both colleges now have online and print access. Although there are links between BJA and both colleges, the Journal retains editorial independence.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Backache. By kaarsten, via iStockphoto.

The post Recent advances and new challenges in managing pain appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories‘Wild-haired and witch-like’: the wisewoman in industrial societyOn ‘work ethic’Anaesthesia exposure and the developing brain: to be or not to be?

Related Stories‘Wild-haired and witch-like’: the wisewoman in industrial societyOn ‘work ethic’Anaesthesia exposure and the developing brain: to be or not to be?

A birthday gift of lullabies for Baby Cambridge

After a long wait, the royal baby has arrived. To honor the occasion, congratulate the Duchess of Cambridge, and welcome the new baby, we at Oxford University Press (OUP) have arranged a birthday gift: a compilation of classic lullabies from some of the different regions around the globe where OUP has offices.

Lullaby from the United Kingdom:

Over the Hills and Far Away

“Over the Hills and Far Away” is a traditional English song from the 17th century. There are at least three versions of this lullaby — written by D’Urfey, Gay, and Farquhar — but the title line and the tune has always remained the same over the years. All the different versions of the song also begin with the same theme, about Tom, the Piper’s Son who only knows one tune, this one.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Lullabies from the Americas:

All The Pretty Little Horses

“All The Pretty Little Horses” describes a mother or caretaker singing a baby to sleep, promising that when the child wakes up it “shall have all the pretty little horses.” There is a theory that explains that the song used to be sung by an African American slave to her master’s child. The slave could not take care of her baby because she was too busy taking care of her master’s child.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Oneida

The song “Oneida” is named after one of the six tribes associated with the Iroquois confederacy, known today as the Hadenosaunee. When roughly translated in English, the lyrics mean:

“Sleep, sleep, baby, I love you

Because you are a very good child, I love you…”

Click here to view the embedded video.

A La Roro Niño

“A la roro niño” is a lovely, sensitively arranged Mexican carol which when translated in English mean:

“Rock my child, rock

Sleep my child, sleep my love…”

Click here to view the embedded video.

Lullabies from Europe:

Bayushki Bayu

“Bayushki Bayu” is a beautiful lullaby from Russia that means:

“Sleep, my darling, sleep, my baby, close your eyes and sleep.

Darkness comes, into your cradle, moonbeams shyly peep…”

Click here to view the embedded video.

Frère Jacques

“Frère Jacques” is the original French version of the rhyme:

“Are you sleeping, are you sleeping

Brother John, Brother John

Morning bells are ringing…”

The tune was first published in 1811, and the lyrics were published in Paris in 1869.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Lullabies from Asia:

So Ja Rajkumari

“So Ja Rajkumari” is an old children’s song first sung in the movie Zindagi in 1940 by singer K. L. Saigal and later by popular singer Lata Mangeshkar as a tribute to Saigal. In English the lyrics are:

“Go to sleep, princess, go to sleep

Go to sleep, my precious one

Sleep and see sweet dreams, in the dream see your beloved…”

Click here to view the embedded video.

Zhao Z Zhao

“Zhao Z Zhao” is a fun Chinese children’s song which means:

“Looking for a friend

Find a good friend

Making a salute, shaking hands

You are my good friend…”

Click here to view the embedded video.

Lullaby from Africa:

Kye Kye Kule

“Kye Kye Kule” (pronounced “Chay Chay Koolay”) is a popular Ghanian song that has been picked up by children all over the globe. It originated from the Fanti Tribe who speak Fanti and Twi. The song does not have any real words in it but is more like a rhyming teasing song that can be played along with a game of touch your head, touch your shoulder-hips-knees-and-toes.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Lullaby from Australia:

Kookaburra

The “Kookaburra” lullaby originated in Australia. It is about a native Australian bird called the Kookabura which is famous for its unmistakable call that sounds uncannily like loud, good-natured but hysterical human laughter.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Natasha Zaman is a marketing intern at Oxford University Press in New York.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A birthday gift of lullabies for Baby Cambridge appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLullaby for a royal babyA bit of a virtual vade mecum

Related StoriesLullaby for a royal babyA bit of a virtual vade mecum

The fall of Mussolini

Seventy years ago today, in the late afternoon of Sunday, 25 July 1943, the fascist dictator Benito Mussolini went for what he imagined was a fairly routine audience with the Italian king.

The war had been going badly for Italy. Two weeks earlier US, Canadian, and British forces had landed in Sicily and were met with little resistance. The previous evening a number of senior fascists had passed a motion calling on the king to assume full military command. However Mussolini had been in power for over twenty years, and in all that time the king had never taken a stand against him. He had little reason to suspect things would be different now. But in the course of the royal audience the king suddenly told him that he was being dismissed as prime minister. Mussolini walked out of Villa Savoia, dazed and incredulous, into the evening Rome sun. He was arrested by military police, bundled into a Red Cross van, and driven away to secret captivity.

Mussolini besichtigt eine neue Fallschirmproduktion bei der italienischen Fliegertruppe!, unknown town, Italy, 1931. Photographer unknown. From the German Federal Archive. Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-12577 / CC-BY-SA. Creative Commons 3.0 Germany via Wikimedia Commons.

The announcement on the radio later that evening that the ‘Duce’ had fallen brought crowds pouring into the streets and piazzas. Joy was mixed with anger. Photographs of Mussolini were tossed from windows; symbols of the fascist party were hacked off buildings; and pavements everywhere were littered with party insignia torn from caps and jackets. But as most commentators recognised, the combination of jubilation and iconoclasm was not the product of relief at being liberated from a reviled dictator. Far more important were the hope — wildly misplaced as it turned out — that Italy’s war would soon be over, and anger that someone in whom so many Italians had pledged such faith had let them down.

Indeed, as countless private diaries and letters reveal, millions of Italians had a relationship with Mussolini that was akin to a love affair. While Hitler received around a thousand letters a month from members of the public, Mussolini regularly received 1,500 a day. Many of these were prosaic requests for help of one kind or another. But many were effusive expressions of devotion. Often these letters were highly sensual, especially those from women. The fact that Mussolini was known to have an extraordinary libido (he kept several mistresses simultaneously, had sexual trysts with female admirers on a daily basis, and fathered countless illegitimate children) encouraged women to relate to him in an erotic way.

Take the case of a Bologna housewife who sent 848 passionate letters to Mussolini between 1937 and 1943:

My great lord and beautiful Duce … you have always been generous in supporting me, because you have experienced the love that I have felt for you and still feel, and I will always love you. And you too have loved me, and your love has felt so sweet and beautiful that my heart will never forget it. I feel your love strongly, and this gives me the strength to remain yours and wait.

Private diaries of women often reveal similar sentiments. One (not untypical) Tuscan teenager agonised in her diary over whether she should love her boyfriend or Mussolini more. In April 1939 she wrote of her ‘liberation’ after breaking up (temporarily) with her boyfriend:

Now that I have no love … it is like a liberation … For I have a heart that needs to love, and I now feel great satisfaction in the love of my fatherland, as I love the Duce above everything else. Because the Duce makes me tremble with excitement, because I only need to hear his words to be transported in heart and soul into a world of joy and greatness.

Such sentiments found an additional emotional charge in religion. The fact that the fascist regime described itself as a ‘religion’ — with the ‘cult’ of the Duce at its apex — encouraged ordinary Italians to relate to Mussolini as if he were a divine figure. A young woman from Genoa who wrote to Mussolini after hearing him on the radio on 30 March 1938 was one of millions — men as well as women — who regarded the Duce, quite genuinely it seems, as a ‘man of providence’:

Forgive me if I, just a humble woman, dare to write to you and use [the familiar form of] ‘tu’. But when I turn to God I do not use [the formal] ‘Voi’ or ‘Lei’ and You for me are a God, a supernatural being sent to us by a superior power to guide our beautiful Italy to the destiny assigned to when Romulus and Remus founded Rome …

Such language was sanctioned by the Catholic Church. From the time Mussolini came to power in 1922, the Vatican saw fascism as a partner and tool in the restoration of ‘Christian civilisation’. Fascism and Catholicism had a common opposition to the ‘materialist’ doctrines of liberalism and socialism. They also shared a belief (amongst many other things) in the importance of spirituality, faith, obedience, authority and order. The frequent and effusive references by the Pope and senior clergy to Mussolini as ‘divinely protected’ or as ‘a man of providence’ (not least after the various failed attempts on his life) perhaps contributed to one of the most curious aspects of the ‘cult of the Duce’. This was the desire, at all costs, to see Mussolini as blameless for what was going wrong in Italy.

Striking in diaries and letters is the widespread belief that the country’s appalling economic problems, rampant corruption, chaotic administration, lack of preparedness for war and disastrous military performance from the summer of 1940 were not Mussolini’s fault. He was ignorant of what was going on due to incompetent advisers. Or worse, he was the victim of treachery. The determination of millions of Italians to keep the man whom they had been encouraged for so many years to see as a genius and a demi-god cocooned in a moral bubble helps to explain the scenes on the streets of Italy seventy years ago. And while many took to the streets to voice anger at what seemed misplaced trust, many also chose to close their eyes to reality.

Typical of the many who did not want to let go of their faith was a Florentine hotel manager. He had heard Mussolini give a speech in Milan in 1920 and was convinced from the start that the fascist leader was sent by God to save Italy. He was in a prisoner of war camp in Kenya when he heard of Mussolini’s fall. The news, as he wrote in his diary, left him physically sick:

I was overcome with a kind of vertigo that left me stunned and confused and stopped me from speaking … Until they bring me concrete and tangible evidence, I will not believe the infamy that is being hurled in the face of a man who passionately wanted our greatness. Have there been any errors? … Until now he can be accused of only one, namely of having too much goodness … Certainly this is strange in someone of his kind … Indeed if he had imitated, if only partly the ferocious Stalin … purging all the scum, we would perhaps not have come to this.

Italy never had any systematic reckoning with its fascist past after the Second World War. And in the last twenty years Silvio Berlusconi (whose own personality cult shares many of the characteristics of that of Mussolini) has encouraged the rehabilitation of the fascist leader. Today dozens, sometimes hundreds, of people daily visit Mussolini’s tomb in the Romagna town of Predappio. The tributes they leave in the registers are often — disturbingly — as passionate as anything their grandparents would have written.

Christopher Duggan is professor of Modern Italian History at the University of Reading. His book, Fascist Voices: An Intimate History of Mussolini’s Italy, is published by Oxford University Press in the United States and has won the Wolfson Prize.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The fall of Mussolini appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesConstantine in RomeThe challenge of decentralized competition enforcement

Related StoriesConstantine in RomeThe challenge of decentralized competition enforcement

Constantine in Rome

July is a month of historic anniversaries. The Fourth of July and Bastille Day celebrate moments that have shaped the modern world. No less important is the 25th of July. This Thursday will mark the 1707th anniversary of Constantine’s accession to the throne of part of the Roman Empire (the part that included York in the UK). Within five years he would have taken over a good deal of the rest of the Roman world and converted to Christianity, setting in motion the transformation of the Roman Empire, and subsequently, Western Europe into Christian societies.

Although Constantine took the throne in York, Rome is the city where Constantine rules this summer. This past fall the Superintendenza speciali per bene di Archeologici di Rome began celebrating the 1700th anniversary of Constantine’s occupation of Rome and conversion to Christianity with a spectacular exhibition in the Colosseum: “Constantino 313 d.C”. The exhibition’s location couldn’t be better, nor could its content be more spectacular. Thousands of people who pass through every day can look out at the great arch celebrating Constantine’s victorious entry into the city. The exhibition puts on view an extraordinary range of unique objects enabling us to appreciate the complexity of the world in which Constantine lived, the remarkable nature of his career, and his relationship with the extraordinary woman who was his mother.

Helena is most often remembered today for something she didn’t really do—that is, discover the fragments of the True Cross on a trip to Jerusalem. What she seems really to have done was give her son the strength and confidence to succeed, even after she was dumped so his father could make a more political marriage. That’s a difficult story, so maybe it’s better to remember her with a myth and a visit to the beautiful Church of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, built where her Roman palace once stood down the street from the massive Church of San Giovanni in Latereno. The same myth appears at the shrine holding her remains in the Church of Santa Maria in Ariceoli. There she resides as a sort of patron saint of the Capitoline and Rome’s eternal empress.

Constantine and Helena. Mosaic in Hosios Loukas. 11th century.

It is appropriate that mother and son greet us as we enter the exhibition. First we see the great colossal bronze portrait of Constantine, brought here from the Capitoline Museum, and then another masterpiece from the same collection, the statue of Helena in the unusually chaste form of the seated goddess Venus. Behind her we meet other actors in this period with busts of other rulers, including a remarkable portrait of Maxentius, who died fighting Constantine in the decisive battle of the Mulvian Bridge. Before he left Rome on the day of the battle he left his imperial regalia in a chest in his palace on the Palatine. These were uncovered a few years ago and are now a stunning part of this exhibition.

It was on the way to Rome that Constantine converted to Christianity. The exhibition, combining treasures of early Christian art with masterpieces of contemporary paganism, helps us understand just how momentous a moment that was. Paganism was anything but a dead letter when Constantine became emperor; he himself was deeply attached to the Invincible Sun, originally a Middle Eastern version of the Classical Sun God believed to have brought victory to an emperor’s armies in a civil war that raged a few years before Constantine’s birth in AD 282. This God was important, but he was scarcely the only eastern God to be garnering attention. In the exhibition we see images of the god Mithras creating the universe by slaughtering the primordial bull, of Serapis (a savior god from Egypt), of Isis (likewise Egyptian and likewise bringing fresh hope to mortals), and of Jupiter Dolichenus (a Syrian God standing on the back of a bull). But then there are the traditional gods of the state, such as Hercules. We can see amulets that people wore to protect themselves from evil spirits and even the occasional evil spirit. At the same time, in the early Christian art so well displayed here, we can see how traditional pagan motifs were given new Christian meaning, just as Constantine was coming to realize that the sun was a symbol of resurrection and the Sun God of his father might really be the God of the Christians. It was Constantine who declared Sunday, or as he put it, the Sacred Day of the Sun, a holiday.

The exhibition also shows us Constantine in the context of other emperors. He was never supposed to have been emperor. His selection was the result of the angry reaction of a group of army officers to the prospect of a new emperor being sent from the Balkans to rule over them. We’re reminded here that Constantine was a political revolutionary before he was a religious revolutionary. He succeeded because he understood that revolutionary leaders must speak the language of their people, hear their concerns, and share their values. If we were to move from the Colosseum along the edge of the Forum, we’ll see memorials to a couple other Roman revolutionaries—the ones we remember every year through the months of July and August. July, of course, recalls Julius Caesar, and August his successor, the emperor Augustus. Without them, there wouldn’t have been a Roman Empire for Constantine to rule.

David Potter is the author of Constantine the Emperor and is Francis W. Kelsey Collegiate Professor of Greek and Roman History and Arthur F. Thurnau Professor of Greek and Latin at the University of Michigan. His books include The Victor’s Crown (OUP), Emperors of Rome, and Ancient Rome: A New History. Read his previous articles for the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Constantine and Helena. Mosaic in Hosios Loukas. 11th century. Photo by anominus. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Constantine in Rome appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesConstantine and EasterOn ‘work ethic’

Related StoriesConstantine and EasterOn ‘work ethic’

The challenge of decentralized competition enforcement

The adoption of Regulation 1/2003 produced a number of significant effects for the enforcement of EU competition law. The European Commission was of course provided with more robust enforcement powers; the relationship between national competition law and EU competition law was clarified; and the EU-level notification system was abolished, with Article 101(3) TFEU becoming directly applicable for the first time. The latter two of these changes in particular have increased the need for EU competition law experts to keep abreast of national competition law developments in the EU.

The relationship between national competition law and EU competition law is now clear: when enforcing national competition law, national competition law enforcers must also apply the relevant EU competition law provision if there is an effect on trade between Member States. The application of national competition law may not lead to the prohibition of agreements, which may affect trade between Member States but which do not fall foul of EU competition law. A comprehensive knowledge of national developments is important here as national cases on restrictive agreements can inform us: (a) whether the Member States are adhering to EU competition law in practice; and (b) whether national enforcers have novel, inspired, or, indeed, unenlightened interpretations of what Article 101 TFEU does and does not prohibit. Regarding unilateral conduct, the Member States can adopt national laws which are stricter than Article 102 TFEU. This fact also ensures that a decent knowledge of national developments concerning unilateral conduct cases is desirable; such cases could provide interesting insights into how jurisprudence on Article 102 TFEU should (or should not) develop in future. These insights could be relevant to practitioners arguing a case before the EU courts or to academics arguing that a different approach to the regulation of unilateral conduct is warranted.

The fact that both Article 101 TFEU and Article 102 TFEU are now directly applicable in the Member States also increases the need for a detailed knowledge of national developments. Private enforcement of competition law has been facilitated by Regulation 1/2003, and, although it remains underdeveloped in Europe, recent developments (such as the publication of a draft Directive on actions for damages) and anticipated future developments could well inspire the growth of private enforcers. If so, such national cases could again provide interesting insights into how the EU competition law rules should be interpreted, particularly if they are stand-alone cases.

Decentralization of EU competition law enforcement is not the only factor leading to the need to understand national competition law decisions and judgments within the EU. A ‘modern’ competition law is a ‘global’ one, a fact that is borne out by the inability of antitrust academics, practitioners and officials, wherever they may be, to continue to ignore the antitrust ideas generated in those regimes that are not their own. An understanding of developments in Europe, then, is also desirable for non-European antitrust practitioners and academics.

Dr Peter Whelan is a Senior Lecturer in Law at UEA Law School and is a Faculty Member of the ESRC Centre for Competition Policy, University of East Anglia. He is the Managing Editor of Oxford Competition Law. A version of this post appears on Oxford Competition Law.

Oxford Competition Law (OCL) is the only fully integrated service to combine universally recognised market leading commentaries with rigorous, selective case reports and analysis from EU member states. The service is continually updated with cases and materials, a must-have for practitioners and legal scholars needing up-to-date information quickly. Oxford Competition Law is the only competition law case reporting service to offer translations into English of the key portions of foreign language judgments.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS

The post The challenge of decentralized competition enforcement appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA bit of a virtual vade mecumUnderstanding history through biographyUnderstanding history through biography - Enclosure

Related StoriesA bit of a virtual vade mecumUnderstanding history through biographyUnderstanding history through biography - Enclosure

July 24, 2013

What’s in a royal name?

HRH Prince George Alexander Louis of Cambridge has arrived! There was much hand-wringing over which names would be chosen for the third in line to the British throne, so we thought this would be an excellent opportunity to pull out our copy of by Patrick Hanks and examine the history of the names given to mother, father, and baby. Below are extracts from the text.

George Alexander Louis (Baby)

George: M. Via Old French and Latin from Greek Georgios. The Greek name is a derivative of geo¯rgos ‘farmer’, from ge¯ ‘earth’ + ergein ‘to work’. This was the name of several early saints, including the legendary figure who is now the patron of England (as well as of Germany and Portugal). If the saint existed at all, he was perhaps martyred in Palestine in the persecutions instigated by the Emperor Diocletian at the beginning of the 4th century. The popular legend in which he is a hero who slays a dragon is a medieval Italian invention. He was for a long time a more important saint in the Orthodox Church than in the West, and the name was not much used in England during the Middle Ages, even after St. George came to be regarded as the patron of England in the 14th century. The real impulse for its popularity was the accession of the first king of England of this name, who came from Germany in 1714 and brought many German retainers with him. It has been one of the most popular English male names ever since.

Alexander: M. From the Latin form of the Greek name Alexandros ‘defender of men’. Its use as a Christian name was sanctioned by the fact that it was borne by several characters in the New Testament and some early Christian saints. However, its tremendous popularity throughout Europe is due mainly to the exploits of the conqueror Alexander the Great (356–23 bc), around whom a large body of popular legend grew up in late antiquity, much of which came to be embodied in the medieval ‘Alexander romances’.

Louis: M. French name, of Germanic (Frankish) origin, from hlud ‘fame’ + wı¯g ‘warrior’ (modern German Ludwig). It was very common in French royal and noble families. Louis I (778–840) was the son of Charlemagne, who ruled both as King of France and Holy Roman Emperor. Altogether, the name was borne by sixteen kings of France up to the French Revolution, in which Louis XVI perished. Louis XIV, ‘the Sun King’ (1638–1715), reigned for 72 years (1643–1715), presiding in the middle part of his reign over a period of unparalleled French power and prosperity. In modern times Louis is also found in the English-speaking world (usually pronounced ‘loo-ee’). In Britain the Anglicized form Lewis is rather more common, as is the alternative spelling Louie.

William Arthur Philip Louis (Father)

William: M. Probably the most successful of all the Old French names of Germanic origin that were introduced to England by the Normans. It is derived from Germanic wil ‘will’, ‘desire’ + helm ‘helmet’, ‘protection’. The fact that it was borne by the Conqueror himself does not seem to have inhibited its favour with the ‘conquered’ population: in the first century after the Conquest it was the commonest male name of all, and not only among the Normans. In the later Middle Ages it was overtaken by John, but continued to run second to that name until the 20th century, when the picture became more fragmented. There are various short forms and pet forms, including Will, Bill; Willy, Willie, and Billy.

Arthur: M. Of Celtic origin. The historical King Arthur was a British king of the 5th or 6th century, about whom very few facts are known. He ruled in Britain after the collapse of the Roman Empire, at the time of the first invasions of the Angles and Saxons, to which he led the resistance. A vast body of legends and romances grew up around him in the literatures of medieval Western Europe. His name is first found in the Latinized form Artorius; the origin is unknown. The spelling with -th- is a 16th-century development. The name became particularly popular in Britain in the 19th century, partly in honour of Arthur Wellesley (1769–1852), Duke of Wellington, the victor of Waterloo, partly because of the popularity of Tennyson’s Idylls of the King (1859–85), and partly because of the enormous Victorian interest in things medieval in general and in Arthurian legend in particular.

Philip: M. From the Greek name Philippos, meaning ‘lover of horses’. This was popular in the classical period and since. It was the name of the father of Alexander the Great. It was also the name of one of Christ’s apostles, of a deacon ordained by the apostles after the death of Christ, and of several other early saints.

Catherine Elizabeth (Mother)

Katherine: F. English form of the name of a saint martyred at Alexandria in 307. The story has it that she was condemned to be broken on the wheel for her Christian belief. However, the wheel miraculously fell apart, so she was beheaded instead. The earliest sources that mention her are in Greek and give the name in the form Aikaterine¯. The name is of unknown etymology, but from an early date it was associated with the Greek adjective katharos ‘pure’. This led to spellings with -th- and to a change in the middle vowel (see Katharine). Several later saints also bore the name, including the mystic St Katherine of Siena (1347–80), who both led a contemplative life and played a role in the affairs of state. Katherine is also a royal name: in England it was borne by Katherine of Aragon (1485–1536), first wife of Henry VIII, as well as by the wives of Henry V and Charles II. The spellings Katharine, Catherine, Catharine, Katheryn, Kathryn, and Cathryn are also found.

Elizabeth: F. The usual spelling of Elisabeth in English. It first became popular because of its association with Queen Elizabeth I of England (1533–1603). Throughout the 20th century it was extremely fashionable, partly because it was the name of Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon (1900–2002), who in 1936 became Queen Elizabeth as the wife of King George VI; even more influentially, it is the name of their daughter Queen Elizabeth II (b. 1926). There are numerous short forms, pet forms, and derivatives, including Eliza, Liza, Lisa, Elsa, Liz, Beth, Bet, Bess, Elsie, Bessy,Betty, Betsy, Libby, and Lizzie.

Elisabeth: F. The spelling of Elizabeth used in the Authorized Version of the New Testament and in most modern European languages. This was the name of the mother of John the Baptist (Luke 1:60). Etymologically, the name means ‘God is my oath’ and it is therefore identical with Elisheba, the name of the wife of Aaron, according to the genealogy at Exodus 6:23. The final element was probably altered by association with Hebrew shabba¯th ‘Sabbath’.

Patrick Hanks has been a lexicographer and linguistic researcher for almost three decades. He was Chief Editor for Current English Dictionaries at Oxford University Press, and is now a professor at the University of the West of England in Bristol. His books include and .

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge, Prince George of Cambridge, and Prince Harry on the balcony of Buckingham Palace, June 2013 by Carfax 2. Creative Commons license via Wikimedia Commons.

The post appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAlphabet soup, part 1: V and ZOf Mormonish and SaintspeakA bit of a virtual vade mecum

Related StoriesAlphabet soup, part 1: V and ZOf Mormonish and SaintspeakA bit of a virtual vade mecum

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers