Oxford University Press's Blog, page 916

August 7, 2013

Human rights education and human rights law: two worlds?

Education and training programmes have become one of the most familiar features of the contemporary global human rights landscape. Their current volume and scope would have been unimaginable even two decades ago. Programmes dedicated to human rights education and training are now delivered by a myriad of actors and are aimed at various audiences. Some of these seek to prompt and inform legislative change or policymaking through outreach to government officials, parliamentarians and civil servants — or to reduce and prevent human rights violations through the training of military or law enforcement personnel. Others are aimed at ‘in-house’ training of human rights advocates, arising out of a perceived need to equip researchers, activists, and advocates with crucial knowledge and skills for more effective promotion and protection of human rights through their work — reflecting a heightened interest in issues around professional standards for human rights work and questions of ethical responsibility, particularly in field operations. The emergence of university-based human rights practice curriculum in recent decades, where students learn not only about international standards, but also about research methodologies and campaigning and advocacy strategies in preparation for careers in the human rights sector, has also extended our understanding of the possibilities for human rights education and training.

In a Special Issue of the Journal of Human Rights Practice, the editors were keen to examine the variety of positions thinkers, activists, and educators have staked out on the question of what might be described as the ‘right relationship’ of human rights education programming to the international human rights legal framework. Is international human rights law — as expressed in the canon of United Nations and regional treaties and then informing other standards — the indisputable basis for the global human rights project and therefore a foundation in which all education interventions must be grounded if they are to have coherence, rigor, and legitimacy? Or, as often seems the case in much writing and talking about human rights education, should the field’s relationship to that defining architecture be something more fluid, creative, or even somewhat detached? On occasion it can seem as though human rights and human rights education inhabit parallel worlds.

There is often something of a critical tone adopted in writing and discussion about human rights education when the relationship with international human rights law is being articulated — an insistence that human rights education needs to set itself up in contrast to or perhaps even in opposition to what is derided as mere human rights legalism. Often what risks becoming rather vague talk about ‘human rights values’ and the creation of ‘human rights culture’ is claimed to be the proper basis for human rights education and its aspirations – occasionally with little more than a nod in the direction of the idea of a necessary prerequisite knowledge and understanding of the international human rights legal framework itself. Concepts like ‘equality’, ‘dignity’, and ‘non-discrimination’ get lifted from foundational documents and invoked as touchstones for human rights education; sometimes invoked endlessly to the point of imprecision.

This tension raises a series of important questions. Is a framing in terms of values and culture more accessible for the general public? Is it an acceptable entry-point for human rights education in contexts where there is considerable hostility to human rights but where core principles such as non-discrimination enjoy more widespread support? Are instrumental framings acceptable — e.g. human rights will make policing more effective or professional? What are the consequences of this tension between activists and scholars for whom the human rights project without reference to international standards makes no sense whatsoever and human rights educators who claim that a certain freedom from that framework is both necessary and desirable in their work? Can human rights education stand apart from the legal framework and still have any real substance?

At the other end of the spectrum, human rights education and training is sometimes understood to be no more than the formulaic delivery of international human rights standards. ‘If people know the law, then the job is done’, can be the ethos behind such interventions. This too, surely, is inadequate. The emphasis in human rights education and training on knowledge, skills and values requires creative approaches anchored in the law, but also horizons and perspectives beyond the law.

Paul Gready is the Director of the Centre for Applied Human Rights (CAHR), University of York. His research is mainly on transitional justice, and development and human rights. His most recent book is ‘The Era of Transitional Justice: The Aftermath of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa and Beyond’, published by Routledge. Brian Phillips is a human rights educator and practitioner, based in Toronto. They are the Editors of the Journal of Human Rights Practice, which has published a Special Issue on human rights education and training.

The Journal of Human Rights Practice is the main academic journal focusing on human rights practice and activism. The application of human rights, and its study, has grown exponentially over the last two decades. The journal covers all aspects of human rights activism, spanning professional and geographical boundaries. It seeks to challenge conventional ways of working, stimulate innovation, encourage reflective practice, highlight fieldwork and evidence, and engage a global audience.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS

Image credit: Justice lady. By 123ducu, via iStockphoto.

The post Human rights education and human rights law: two worlds? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIs yoga religious? Understanding the Encitas Public School Yoga Trial‘Yesterday I lost a country’The origins of the Fulbright program

Related StoriesIs yoga religious? Understanding the Encitas Public School Yoga Trial‘Yesterday I lost a country’The origins of the Fulbright program

August 6, 2013

Is yoga religious? Understanding the Encitas Public School Yoga Trial

Practicing yoga is more popular than ever, with plenty of studios to be found across the US. As yoga has now begun to enter school curriculum, some parents and their children are unhappy, feeling that programs such as these are religious. The topic was recently up for debate in Encinitas, CA, where Candy Gunther Brown, author of The Healing Gods: Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Christian America, served as an expert witness in the case. Brown explains the case, the ruling, and its implications.

Are you familiar with a recent court case in Encinitas, California over yoga in public schools?

Yes, I served as an expert witness in this case. The plaintiffs asked me to testify because I am a religious studies scholar who studies yoga’s cultural mainstreaming in America. I accepted the request because part of my job as a university professor is to educate the public about “religion.”

What events led up to the Encinitas Public School Yoga Trial?

The Encinitas Union School District (EUSD) accepted a $533,720 grant from the Jois Foundation to establish (to quote the signed grant) an “Ashtanga Yoga” program staffed by Jois “trained” and “certified” instructors who “partner”ed in developing a “comprehensive” yoga curriculum for Jois to export to “other school systems.” The program appeared religious to children and parents who discussed their concerns with school officials and collected 250 signatures on a petition.

[image error]

WholyFit Certified Instructor performing “Overcomer” pose in a church building with a Christian cross in the background, 2011. Image courtesy of Erin Garvey.

What is Ashtanga yoga?

Ashtanga, or eight-limbed, yoga was developed by Krishna Pattabhi Jois (1915-2009) from the Yoga Sutras, a sacred text for Hindus. The eight limbs are (1) yama: moral restraint, (2) niyama: ethical observance; (3) asana: posture; (4) pranayama: focused breathing; (5) pratyahara: calm mind; (6) dharana: attention; (7) dhayana: meditation; (8) samadhi: union with God (Brahman).

Ashtanga emphasizes postures and breathing on the premise that these practices will “automatically” lead practitioners to experience the other limbs and “become one with God,” in the words of Jois, “whether they want it or not.”

Ashtanga begins with Surya Namaskara (Sun Salutations, or Opening Sequence) to “pray to the sun god,” Surya, chief Hindu solar deity, coordinates breath with movement (to “let the prana [vital breath, or spiritual energy] flow”), and ends with lotus poses, which symbolize spiritual purity and move prana to facilitate meditation.

What is the Jois Foundation?

The Jois Foundation was founded “in loving dedication” to K. P. Jois, with funding from billionaire Paul Tudor Jones whose wife Sonia is an Ashtanga devotee, to spread Ashtanga, especially to kids. Following the trial, the foundation was renamed Sonima, after Sonia.

What was the judge’s ruling?

Superior Court Judge John Meyer had to decide whether the EUSD yoga program violates the religious establishment clause of the Constitution’s First Amendment by advancing or inhibiting religion or entangling government with religion.

Meyer determined that “yoga,” including “Ashtanga” yoga, “is religious.” Nevertheless, he allowed EUSD’s yoga program to continue, since he did not think children would perceive the program as advancing or inhibiting religion. The judge found the Jois Foundation partnership “troublesome,” but did not rule that it excessively entangled government with religion.

Were you surprised by the decision?

I found the decision inconsistent in its internal logic, as well as with legal precedents and facts in evidence. Courts have found that practices such as prayer and Bible reading cannot be taught in public schools because they are religious. If yoga is religious, it should not be taught in schools. Courts ask whether a reasonable, informed observer would consider practices religious. Children may not have enough information to determine whether less familiar practices are religious.

What would an informed observer perceive as religious about the EUSD yoga program?

EUSD teachers displayed posters of an eight-limbed Ashtanga tree and asana sequences taught by the “K. Pattabhi Jois Ashtanga Yoga Institute”; used a textbook, Myths of the Asanas, that explains how poses represent gods and inspire virtue; taught terminology in Sanskrit (a language sacred for Hindus); taught moral character using yamas and niyamas from the Yoga Sutras; used guided meditation and visualization scripts and taught kids to color mandalas (used in visual meditation on deities).

Although EUSD officials reacted to parent complaints by modifying some practices, EUSD classes still always begin with “Opening Sequence” (Surya Namaskara) and end with “lotuses” and “resting” (aka shavasana or “corpse”—which encourages reflection on one’s death to inspire virtuous living), and teach symbolic gestures such as “praying hands” (anjalimudra) and “wisdom gesture” (jnanamudra), which in Ashtanga yoga symbolize union with the divine and instill religious feelings.

Have any EUSD kids associated the school yoga program with religion?

Yes. Some refused to participate in activities that felt like prayer to them. Many kids in EUSD classes still chant Om, assume jnanamudra, close their eyes to meditate while sitting in lotus, and use Sanskrit, such as Namaste (“I bow to the god within you”) and shavasana for “resting” pose.

How do you explain the judge’s decision?

Judge Meyer discounted everything that happened in EUSD classrooms between August 2011 and December 2012 that “could be arguably deemed religious.” He also overlooked ongoing practices such as Surya Namaskara, shavasana, anjalimudra, chanting Om, meditation, kids’ use of Sanskrit, and EUSD use of the Sanskrit term yoga, which in Ashtanga means yoking with the divine. He refused to admit into evidence a newly discovered document revealing that in March 2013 EUSD-employed “Jois Foundation teachers” took EUSD students on a field trip to demonstrate “teaching Ashtanga yoga to children both in and out of the school system” at an overtly religious Ashtanga conference (opened by a Ganesh Puja).

Meyer got basic facts wrong. He concluded that EUSD removed the appearance of religion by renaming poses, giving the example that “the so-called lotus position was renamed criss-cross applesauce.” The term “criss-cross applesauce” does not appear even once in the spring 2013 yoga curriculum; the term “lotus” appears 194 times. The 2013 EUSD promotional video records a teacher instructing: “go into lotus.” Meyer believed testimony that jnanamudra was replaced by “brain highways,” a claim contradicted by defendant declarations and the video. Indeed, Meyer ignored multiple instances where defense witnesses contradicted themselves, each other, and documents they signed.

What are the implications of this ruling?

The ruling sets a precedent for public schools to offer religious yoga programs. Indeed, just last week, EUSD accepted a new $1.4 million grant from the Jois/Sonima Foundation to expand its yoga program. Scientific research shows that practicing yoga can lead to religious transformations. For example, Kristin is a Catholic who started Ashtanga for the stretching; she now prefers Ashtanga’s “eight limbs” to the “Ten Commandments.” Kids who learn yoga in public schools may also be learning religion.

Candy Gunther Brown is Associate Professor of Religious Studies at Indiana University. She is the author of The Healing Gods: Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Christian America, Testing Prayer: Science and Healing, and The Word in the World, and she is the editor of Global Pentecostal and Charismatic Healing. Her work has been published in The Huffington Post, Psychology Today, and The Daily.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Is yoga religious? Understanding the Encitas Public School Yoga Trial appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories‘Yesterday I lost a country’The mysteries of Pope FrancisWhy should we care about the Septuagint?

Related Stories‘Yesterday I lost a country’The mysteries of Pope FrancisWhy should we care about the Septuagint?

An interview with Sarah Japhet

Shai le-Sara Japhet: Studies in the Bible, Its Exegesis and Its Language [Hebrew]

Bar-Asher, Moshe, Dalit Rom-Shiloni, Emanuel Tov and Nili Wazana, editors. Jerusalem: Bialik Institute, 2007

In an interview with Professor Marc Zvi Brettler of Brandeis University, Professor Japhet explains how she became interested in the Chronicler, which she describes as “a fresh, critical spirit with the courage to look at Israelite history in a different way.” This emphasis on new and critical perspectives, she explains, helped to frame her career, and was fitting given her appointment as the first tenured woman in the Bible Department at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. In addition, Japhet discusses how her early experiences with Chronicles informed her ongoing work on the larger issues of exegesis and historiography.

The audio version of the interview is embedded above, and a transcription with footnotes is available here

Robert Repino is an Editor in the Reference department of Oxford University Press. After serving in the Peace Corps in Grenada, he earned an MFA in Creative Writing at Emerson College. His work has appeared in numerous publications, including The African American National Biography (2nd Edition), The Literary Review, The Coachella Review, Hobart, and JMWW. His debut novel is forthcoming from Soho Press in 2014.

Oxford Biblical Studies Online is a comprehensive resource for the study of the Bible and biblical history. With Biblical texts, authoritative reference works, and tools that provide ease of research into the background, context, and issues related to the Bible, Oxford Biblical Studies Online is a valuable resource for students, scholars, clergy, and any reader seeking an up-to-date ecumenical resource. Oxford Biblical Studies Online is vetted by a team of leading scholars headed by Michael D. Coogan.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post An interview with Sarah Japhet appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAn interview with Sarah Japhet - EnclosureTwelve facts about the drum kitUnderstanding history through biography

Related StoriesAn interview with Sarah Japhet - EnclosureTwelve facts about the drum kitUnderstanding history through biography

Memo From Manhattan: The Tompkins Square Park Riot

Today, the sixth of August, marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Tompkins Square Park riot in New York’s East Village. Though on that night many neighborhood residents were protesting in the streets — a crowd that included activists, artists, punks, skinheads, squatters and anarchists — the riot was caused by police brutality. Many still blame the police for enforcing a 1 a.m. curfew on the park, knocking demonstrators and bystanders to the ground and clubbing them till blood flowed.

The riot marked the end of politics as art and life as a performance, hallmarks of the alternative cultures for which the East Village was known. But even more important, the police denial of access to the park signaled the local triumph of gentrification.

The stain of gentrification had spread slowly through the neighborhood. Built as a working class district in the mid-nineteenth century, this northern half of the Lower East Side housed generations of immigrants, first from Germany and then from Eastern Europe, and eventually Puerto Ricans who came to New York in the 1950s. Many of the old tenements were in dismal condition. Buildings on Avenue A, on the park’s perimeter, were abandoned. In some of them, squatters illegally siphoned water and electricity. Their DIY renovations symbolically waved a red flag in the face of the police, private property owners, and the city government.

Yet some landlords had already begun to carry out renovations and charge higher rents. Christadora House, on Avenue B, which during the Great Depression offered social services to the neighborhood’s poor, had recently been sold by the city government to a private investor and converted to condos. At the time of the riot, an apartment there sold for the then astronomical price of half a million dollars.

On the night of 6 August 1988, protesters shouted at the police and shattered the Christadora’s glass doors. They carried hand-painted banners that said “Gentrification is Class War.” They understood that police brutality, access to the park, and affordable homes were locked in the same struggle: a struggle for the city’s soul.

“A Hot Summer Night”

The events of the night were indisputable. Even before the days of cell phone videos, reporters and photographers recorded graphic images of violence. They “showed police officers striking people with nightsticks, kicking people who were on the ground, and covering their shields to hide their identity.” That is the dispassionate description on the website of the Civilian Complaint Review Board, which has the authority to evaluate police actions.

Also beyond dispute is the local precinct’s desire to assert its control. But looking back on that night in a recent documentary film, one of the protesters, who calls himself a squatter/anarchist, now says, “It was a hot summer night, and all the cops were young.”

Whether by inexperience or a drive for power, both sides that night were primed for conflict. The NYPD has never had a reputation for tolerating political demonstrations and the local precinct, perhaps with little guidance from central command, believed it was enforcing the community’s will.

A Changing Community

In fact, the 1 a.m. curfew that closed Tompkins Square Park was supported by many who lived in the area, including traditional Puerto Rican families, Ukrainian and Polish exiles from communism, and young, “white” newcomers with higher incomes and education.

Many of them had suffered from, and been drawn into, the underground economy of illegal drug dealing that the police targeted with Operation Pressure Point in the mid-1980s. Hispanics for the most part were victims of a heroin epidemic. But they also cleared drug debris from the many vacant lots where abandoned houses had stood, and turned those hostile spaces into community gardens. Though they had no reason to love the police, they wanted more police protection against drug dealers and a calmer, more orderly street life.

Some residents, not only Hispanics, wanted relief from the panhandling and public displays that hippies who came to the area in the late 1960s engaged in. Others wanted relief from the loud music that people performed at night in Tompkins Square Park and nearby bars.

But the counterculture of the sixties had changed the East Village. Migrating from all over the United States, and from overseas as well, hippies made the neighborhood a focal point of youth culture, experimentations with marijuana and LSD, and polymorphous sexuality. Unlike earlier artistic migrants, like Beat poet Allen Ginsberg and jazz musician Charlie Parker, who were a “creative class” for the Fordist era, the newcomers didn’t blend easily into local coffee shops and diners. Instead, they colonized the sidewalks and formed communes in vacant stores. They opened cheap used clothing stores, music exchanges, and shops for drug paraphernalia.

The combination of Beats and hippies, living in dilapidated housing with only sporadic police control, was a magnet for artists and free thinkers of all kinds. Some of them affiliated with punk rock and nihilism — the raunchy music club CBGB was nearby — while others started art studios, opened fledging art galleries in their bathrooms, and performed in multi-purpose bars. This was the downtown crucible in which Jean-Michel Basquiat, Madonna and Blondie were formed.

When the New York Times Magazine published a cover story on the East Village art scene in 1985, it was clear the neighborhood was headed toward gentrification.

The Political Brew

During the 1980s, gentrification throughout Manhattan made the brew of local politics even darker. The mayor saw the East Village turning a corner from low-income housing and squatters to market rents. New York University, whose campus spread eastward from Washington Square Park, expanded its student body and many students would pay high rents for tenement apartments. Rent control laws were steadily losing political support; city government programs subsidized improvements that went beyond the controls and brought higher rents. Under these conditions, skinheads, squatters and anarchists posed a fiery response, but it and they were not accepted by others in the community.

The local community board could not balance the antithetical cultures of all East Village groups. Pressed by competing demands, board members endorsed a nightly curfew for Tompkins Square Park that the city government proposed. This is the issue that led the police to incite a riot.

Aftermath

After the riot of 6 August, police officers were censured and some lost or left their jobs. Within a few years, the Civilian Complaint Review Board was reorganized to remove police members. But the question of who would control the park, and the even larger issue of gentrification, were not resolved.

In 1991, a homeless encampment in Tompkins Square Park was forcefully destroyed by the city government. During the previous few years, rising numbers of homeless men and women had spilled into more streets and parks. Some of them had been chased out of Washington Square Park by the police and out of Union Square Park by the business improvement district that managed it. In Tompkins Square Park, they slept on benches and erected tents.

As in 1988, the tent city was not accepted by all groups in the community. Parents saw the park as dirty and dangerous and could not bring their children to the playground. Many residents felt threatened by the large homeless presence and by the problems of untreated illness, alcoholism, and drug abuse they brought with them.

Mayor David N. Dinkins took the same point of view. “This park is a park,” he said. “It is not a place to live. I will not have it any other way.” So did the parks commissioner, Betsy Gotbaum. “What we’ve learned is when you start to see that stuff — people putting up tents and tepees — you’ve got to go in and get rid of it,” she said. “Otherwise it will turn into a shantytown, and that’s not what parks are for.”

My late friend and colleague, the geographer Neil Smith, staunchly argued that this view reflects a deep-seated hatred of the poor, and that it ushered in an era of “revanchism” that pushed low-income residents outside the centers of cities and found comfort in repression. This is not entirely correct.

Though no one can argue that many of the poor and even not-so-poor have not left the East Village, the middle class are not to blame for rising rents. Real estate developers have a long-term interest in “producing” urban space and city governments need to raise revenues from whoever has deep pockets. When many private owners control housing, government has no incentive to interfere.

Photo by Sharon Zukin. All rights reserved.

But Tompkins Square Park has gone through the process of privatization that Neil foresaw. For many years the city government has continued to cut the parks department’s budget, leading this park, like many others, to depend on private funding. Since 1995, Tompkins Square Park has been partly financed by a private, nonprofit group, East Village Parks Conservancy. For $4,000, you can dedicate any tree in the park, including three historic Great Sycamores and any elm. For $3,000, you can dedicate any tree except the sycamores. And for $2,000, you can dedicate any tree except the sycamores and the elms. Moreover, its dog run was the first in the city to be privately funded by another group of “friends.”

You can gaze on the now beautifully landscaped park from a window across the street, in the Christadora. In 2011, a one-bedroom apartment there sold for almost $2 million.

Sharon Zukin is Professor of Sociology at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center. She is the author of Loft Living, Landscapes of Power (winner of the C. Wright Mills Award), The Cultures of Cities, Point of Purchase, and most recently Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places. You can read her previous posts Memo From Manhattan on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Poor people’s parks – Tompkins Square. From Hearth and home. 1873. Courtesy of NYPL Digital Collection.

The post Memo From Manhattan: The Tompkins Square Park Riot appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTwo faces of the Limited Test Ban TreatyWhy we should commemorate Walter PaterA lion: Joseph Paxton in the nineteenth century and today

Related StoriesTwo faces of the Limited Test Ban TreatyWhy we should commemorate Walter PaterA lion: Joseph Paxton in the nineteenth century and today

Twelve facts about the drum kit

Drummers are often seen as the most unintelligent and unmusical of band members. Few realize how essential the kick of a pedal and tap of the hi-hat are for setting down the beat and forming the tone of the band. So what is there to the drum kit besides a set of drums, suspended cymbals, and other percussion instruments? What’s in this basic equipment of the jazz, rock, and dance-band drummer? I searched the Oxford Index for 12 short facts about the drum kit and the drummers that make it such a remarkable instrument.

(1) Rick Allen, the drummer for Def Leppard, used a semi-electronic drum kit following the loss of one of his arms in an accident in 1984.

(2) Suitcase was once a popular slang term for a drum kit, chiefly among African Americans.

(3) Brushes have been used since the 1920s, especially in jazz and dance bands, to produce a softer sound than ordinary side-drum sticks.

(4) Many drummers were given their first drum kit at a very young age (presumably by parents with a high tolerance for noise): Baby Lovett was given a drum kit at the age of 13, Al Foster at the age of 10, Jason Bonham at the age of four.

(5) The most visible of the 1930′s drummers, Gene Krupa, had a major effect on his colleagues. The Krupa “look”, his ideas and techniques and showmanship, were dominant during that time. Krupa brought high-level discipline and energy and a whole array of new challenges to drumming. In the 1930s, while defining and formalizing a traditional swing vocabulary for drums, Krupa moved the drummer into the foreground. A technically advanced, exciting player, he had a lot to do with making the drum solo not only acceptable but musically and commercially viable.

Gene Krupa, Washington, D.C., between 1938 and 1948. Photograph by William P. Gottlieb. Image courtesy of Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

(6) While the drum kit is most prevalent in popular music, it sometimes appears in classical compositions. Michael Smetanin’s interest in rock and funk music is evident in the expanded drum kit sound of the percussion quartet Speed of Sound (1983). Vic Hoyland’s Dumbshow (1984) requires a male and female performer in Edwardian costume to execute minutely detailed actions on giant chessboards in exact synchronzation with a meticulously notated score for drum kit.

(7) Bebop drummers used the drum kit in new, inventive ways. In swing big bands, the drummer generally kept up a strong four-beat rhythm on the bass drum, and often on the snare drum as well. By contrast, the innovative bop drummer Kenny Clarke—soon followed by Art Blakey and Max Roach—used the bass drum only for occasional punctuation, “dropping bombs” to spur on a soloist or to provide particular emphasis. For bop drummers, the key timekeeper was the ride cymbal, a single large cymbal mounted on a stand. Drummers found it easier to negotiate bop’s often blistering tempos with light, shimmering rhythms on the cymbal than with the comparatively clumsy foot-pedal (operated bass drum). Using the ride cymbal to maintain the ground beat also freed the other parts of the drum kit—the snare drum, floor tom, high hat cymbal, and bass drum—for the drummer to use in adding fills, cross rhythms, and tonal color. Ideally, the drummer, bass player, and pianist worked as a smooth and responsive unit in support of the improvising soloists.

(8) Drum kits are an essential element of the rhythm section: the percussion, bass, and chordal instruments of a jazz ensemble, typically consisting of drum kit, double bass (always played pizzicato).

(9) A drummer’s distinct style can shape the music of a band. For example, Ringo Starr’s style became synonymous with the ‘Mersey beat’ that swept the world of pop music.

(10) Sunny Murray was responsible for the development of the colouristic, unmetred style of free-jazz drumming in which the player, rather than marking time, contributes to the collective improvisation by accentuating freely and by exploring the timbres and pitches of the various components of the drum kit.

(11) “Viola and her 17 Drums” was a solo act by American drummer Viola Smith, one of the few famous female drummers.

(12) The first product of renowned instrument maker Ludwig was a foot-pedal for trap drums.

Do you have any fun facts about the drum kit to add to our list?

Alice Northover is a Social Media Manager at Oxford University Press. She is editor of the OUPblog, constant tweeter @OUPAcademic, daily Facebooker at Oxford Academic, and Google Plus updater of Oxford Academic, amongst other things. She quit band when she failed to learn how to play the drum kit and the teacher found out she’d been faking understanding musical notes while playing the timpani.

The Oxford Index is a free search and discovery tool from Oxford University Press. The Index is designed to help you begin your research journey by providing a single, convenient search portal for trusted scholarship from Oxford and our partners, and then point you to the most relevant related materials — from journal articles to scholarly monographs.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Twelve facts about the drum kit appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAnthems of AfricaAn ice cream quizLullaby for a royal baby

Related StoriesAnthems of AfricaAn ice cream quizLullaby for a royal baby

August 5, 2013

The federalist argument for the Multi-State Worker Act

By Edward Zelinsky

The Multi-State Worker Act (the current version of the Telecommuter Tax Fairness Act) would, if enacted into law, prevent states from taxing non-resident telecommuters (like me) on the days they work at their out-of-state homes. Can someone who values the states and their autonomy (also like me) favor the Act?

The answer is “yes.” The Multi-State Worker Act would advance federalist concerns by protecting the states whose residents are currently subject to intrusive and unconstitutional taxation by New York under New York’s so-called “convenience of the employer” doctrine.

For over a decade, supporters of telecommuting have criticized New York’s convenience of the employer doctrine as unwise and unconstitutional. Under the banner of employer convenience, New York imposes income taxes on non-residents on the days they work at their homes outside the Empire State. In my case, New York imposes income taxes on me for the days when I write, grade, and research at my home in New Haven, Connecticut — even though, on these work-at-home days, I spend no time in New York and receive all of my public services on that day from the Nutmeg State and its municipalities.

New York’s taxation of work performed in other states was once dismissed as a rare and regional phenomenon, restricted to New York’s occasional income taxation of individuals on their days working at their homes in Connecticut and New Jersey. However, as cases like Mr. Huckaby’s and Mr. Kakar’s indicate, New York today routinely sends income tax bills to individuals who work at home throughout the nation. New York taxed Mr. Huckaby’s income on the days he worked in Tennessee and taxed Mr. Kakar’s income on the days he worked at home in Arizona. It is particularly ironic for New York to tax Mr. Huckaby’s income for a day worked at his Nashville home when the Tennessee legislature levies no personal income tax on that income earned in Tennessee.

Other states, seeing New York tax outside its borders with impunity, are starting to emulate the Empire State. Thus, Delaware taxed Dorothy Flynn’s income for the days she worked at her Pennsylvania home, even though Ms. Flynn did not set foot in Delaware on these work-at-home days.

Over the years, telecommuting has become more common and New York’s projection of its taxing authority throughout the nation has become more blatant and more troublesome. Within the Empire State, some recognize that the employer convenience doctrine is bad for New York, one more tax-related reason for employers and investors to avoid New York. To date, however, for New York’s policymakers, the temptation to tax nonvoting, non-residents on days they work at their out-of-state homes has proved politically attractive, despite the long-term damage such overreaching income taxation causes to New York’s economy. And, as Ms. Flynn’s case demonstrates, other states are likely to follow New York by taxing non-voting non-residents on the days they work at their out-of-state homes.

It has thus become clear that Congress, acting under the Commerce Clause of the US Constitution, must legislate to end New York’s taxation of telecommuters who work outside New York’s boundaries. Such legislation has in the past been introduced in Congress on a bi-partisan basis and is supported by a wide array of groups including the Small Business & Entrepreneurship Council, and Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America. Veterans groups are particularly sensitive to the benefits of telecommuting for veterans re-entering the workforce and the harm of New York’s tax policies on such telecommuting.

As national legislation has emerged as the right response to the problem of New York’s unconstitutional income taxation of non-resident telecommuters on the days such telecommuters work at their out-of-state homes, the question has increasingly been posed: How can such national legislation be reconciled with federalist concerns, that is, respect for the authority of the states?

This shift in the debate is encouraging. No one any longer doubts that New York brazenly sends income tax bills throughout the nation for work performed outside the boundaries of the Empire State. No one doubts the growing importance of telework performed at home or the unfair and inefficient burden New York imposes on such work. The danger that other states will emulate New York is, as Ms. Flynn can testify, now equally apparent.

The threat to federalist values stems, not from the Multi-State Worker Act, but from New York’s overreaching. Central to the federalist enterprise is the ability of each state to tax and govern within its own borders. National legislation outlawing New York’s (and other states’) taxation of out-of-state telecommuters would enhance federalist values by protecting the states in which non-resident telecommuters live and work. When New York sends a tax bill to me in Connecticut, to Mr. Huckaby in Tennessee, or Mr. Kakar in Arizona, New York illegitimately intrudes into the jurisdiction of those three states. Acting under the Commerce Clause, Congress has the authority to protect states and their citizens from New York’s unconstitutional and unfair intrusion of its taxing authority into those states.

The Act would thus protect the other states and their residents from New York’s intrusive taxation outside its borders. In federalist terms, the Multi-State Worker Act would protect the states into which New York (and other states) intrude under New York’s convenience of the employer doctrine. Passage of the Act is long overdue.

Edward A. Zelinsky is the Morris and Annie Trachman Professor of Law at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law of Yeshiva University. He is the author of The Origins of the Ownership Society: How The Defined Contribution Paradigm Changed America. His monthly column appears on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Woman in home office with computer and paperwork frowning. © monkeybusinessimages via iStockphoto.

The post The federalist argument for the Multi-State Worker Act appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThings to do in Orlando during AOM2013‘Yesterday I lost a country’The strengths and limitations of global immunization programmes

Related StoriesThings to do in Orlando during AOM2013‘Yesterday I lost a country’The strengths and limitations of global immunization programmes

Things to do in Orlando during AOM2013

By Kathleen Tam

The 73rd Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management is taking place in Orlando this year. The conference provides a forum for sharing research and expertise in all management disciplines through invited and competitive paper sessions, panels, symposia, workshops, speakers, and special programs for doctoral students. The 2013 theme is “Capitalism in Question” and will feature 1,600 activities involving more than 8,300 people from 88 countries.

First and foremost, we’d love to see you at the OUP booth #500. You can follow the conference on social media with the hashtag #AOM2013, follow the Academy of Management on Twitter @AOMConnect, and attend the AOM Tweetup on Sunday.

If you get a chance while you’re in Orlando, here are a few places you might want to visit:

Disney’s Boardwalk

It is walking distance from the Dolphin hotel. It includes restaurants, shops and entertainment.

ESPN Club. Are you a big sports fan? This restaurant/bar has over 300 television screens to watch your favorite game or program. Fun fact: TVs hover all over the restaurant so you literally won’t miss one minute of your favorite game!

BoardWalk Joe’s Marvelous Margaritas. Known for its quick service to get margaritas, sangrias, beer and soft drinks if you need to cool down and relax for a little.

Flying Fish Café. This restaurant is known for its seafood and steaks.

Epcot and Hollywood Studios theme parks

From the Dolphin hotel, you can walk to Epcot or take a boat to Epcot or Hollywood Studios. The boat leaves you right outside the respective theme parks.

Coral Reef in Epcot. Highly recommended this restaurant for its food and atmosphere. While eating, you can see an aquarium (the fish and scuba divers).

Sci-Fi Dine In in Hollywood Studios. This restaurant takes you back to 1950s and makes you believe you are at a drive-in movie theater.

Jeweled Dragon Acrobats. In Epcot China, these kid acrobats show their balance, flexibility, and strength in this wonderful performance.

Fantasmic! A firework and light show taken place at night in Hollywood Studios, features Mickey Mouse and characters from your favorite Disney movies.

Downtown Disney Marketplace

You can either drive or take the Disney bus to Downtown Disney. This is a great break from the theme park crowds. Restaurants include the House of Blues and Fulton’s Crab House. Enjoy entertainment at La Nouba-Cirque de Soleli and the Lego Store. And don’t forget to buy souvenirs for your family and friends.

Walt Disney World Swan and Dolphin Resort

These famous Disney resort hotels are located in the heart of the Walt Disney World. You can even stay fit at the health clubs (with equipment, lockers, showers etc.), on the jogging trails (to enjoy a scenic view), and in the courts (basketball tennis, and volleyball) — all included in your hotel fees! But if you’re looking for some time out…

Mandara Spa. Located at the Dolphin hotel, provides services such as massages, hair, nails, and makeup.

Kinomos. Even though it’s known for its high class and sushi bar, they also have karaoke at night.

Fresh Mediterranean Market. This restaurant serve food from all over the world (Spain, Italy, France, Greece and Morocco), giving the vibe of a real Mediterranean market.

Picabu. This is an affordable buffet for adults and especially kids.

See you at the conference!

Kathleen Tam is a marketing intern at Oxford University Press (OUP). Representatives from OUP will be attending the Academy of Management Annual Meeting highlighting some of our newest works including The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Governance, Materiality and Organizing, and Knowledge, Organization, and Management.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Things to do in Orlando during AOM2013 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories‘Yesterday I lost a country’The strengths and limitations of global immunization programmesOil and threatened food security

Related Stories‘Yesterday I lost a country’The strengths and limitations of global immunization programmesOil and threatened food security

Two faces of the Limited Test Ban Treaty

Fifty years ago, the United States, United Kingdom, and Soviet Union signed a pact to stop testing nuclear bombs in the atmosphere, oceans, and space. As we commemorate the treaty, we will not agree on what to celebrate. There are two sides of the story.

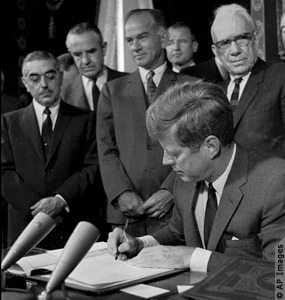

President John F. Kennedy signs the Limited Test Ban Treaty in October 1963. Courtesy of U.S. Department of State.

Without question, the treaty was a positive highlight for those striving to ease tensions and move the world toward peace. Having come to the brink of disaster during the Cuban Missile Crisis, negotiators got serious about arms control and took specific measures. The subsequent SALT limitations, START reductions, and comprehensive test ban all trace their lineage to that important document of the Kennedy-Khrushchev era.

As an accord about war and peace, the treaty is comprehensible. What about the treaty as an environmental document? There is an intriguing line in the formal text stating a key motivation as “desiring to put an end to the contamination of man’s environment by radioactive substances.”

That motivation has nothing to do with war or peace. It is about the widespread, harmful effects of human actions.

Did governments revise their national policies because their actions were altering the earth? Given the important role of governments in addressing today’s environmental challenges, this would be something extraordinary to commemorate, if it were true.

Nuclear tests prompted serious questions about the changing natural environment. For example, the tests were frequently linked to wild swings in weather. The winter of 1962-63 was horrendous, following on the heels of the most atmospheric testing ever. Plummeting temperatures and extreme weather became the norm throughout the northern hemisphere. People in the town of Bari, on the heel of Italy, had ten inches of snow, and Japan endured its worst snowstorms in recorded meteorological history. In Britain it was called the “Big Freeze of ’63,” and helicopters had to drop supplies into marooned villages.

Even NATO scientists thought linking fusion blasts to geophysical events had promise. In the early 1960s they imagined using hydrogen bombs to trigger earthquakes, steer hurricanes, and redirect ocean currents. Had the LTBT treaty never been signed, environmental warfare—a NATO term—might have been incorporated into tests.

In addition to weather, geneticists believed that fallout—the radioactive debris from the tests—generated harmful mutations in the world’s gene pool. Each test meant additional birth defects somewhere in the world. Some scientists, such as Caltech biochemist Linus Pauling, tried to stop the tests on legal grounds. What right did the nuclear states have to subject the whole world to the harmful effects of fallout? Pauling’s efforts to present an anti-testing petition to the United Nations, signed by over nine thousand scientists, won him 1962’s Nobel Peace Prize.

Ironically, signing the test ban treaty as a gesture of peace meant that governments never had to make a decision based purely on the harm done by the tests themselves. Although they rolled the fallout controversy into the treaty language, they did so without full engagement of the scientific evidence of harm and without entertaining the argument about the illegality of testing.

American, British, and Soviet government activities prior to test bans illustrated how profoundly insulated they were from health and environmental arguments. Before the first informal testing moratorium in 1958 under President Eisenhower, all three nations rushed to get in as many tests as possible. Britain made five tests at Christmas Island, its Pacific test site, while the Soviets tested 34, more than twice that of the previous year. The United States detonated 72 bombs, including a project to explode bombs in the earth’s newly-discovered radiation belt.

When the Soviets broke the moratorium, they did so with gusto, including a detonation called Tsar Bomba, about 4,000 times the size of the blast that destroyed Hiroshima.

In the year leading up to the Limited Test Ban Treaty—that is, after diplomats already had planned to negotiate an end to the tests—the nuclear powers created the greatest fireworks displays of all time and saturated the atmosphere with radioactive debris. The United States led the way in Operation Dominic, with more than a hundred nuclear tests, including more at high-altitude in the radiation belts. One of these, the Starfish Prime shot, knocked out the electricity in Hawaii. The Soviets also had an ambition program in 1961 and 1962, conducting 138 nuclear tests. All the nuclear powers saw these as the last hurrah.

The nuclear testing blitz in 1962 should serve as a sobering reminder of the tiny impact of scientific arguments about health and environmental effects. On the other hand, these governments were quite responsive to the political problem posed by the fallout controversy, which is why the treaty refers to radioactive debris.

The Limited Test Ban Treaty was not ideal. Because it was above all an arms control agreement, its authors simply swept away the arguments against nuclear testing rather than answer them. Still, the world got what it needed: a genuine ban and the first treaty to point out the threat of global environmental contamination.

Jacob Darwin Hamblin is an associate professor of history at Oregon State University and is the author of Arming Mother Nature: The Birth of Catastrophic Environmentalism. You can follow him on Twitter @jdhamblin.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Two faces of the Limited Test Ban Treaty appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy we should commemorate Walter PaterA lion: Joseph Paxton in the nineteenth century and todayThe first branch of the Mabinogi

Related StoriesWhy we should commemorate Walter PaterA lion: Joseph Paxton in the nineteenth century and todayThe first branch of the Mabinogi

‘Yesterday I lost a country’

Since 2003, Iraq has experienced significant political unrest and the emergence of ethno-religious divisions. A sectarian complexion to emerging socio-political movements in Iraq (religious, ethno-political) is not in question. The ‘fear of sectarianism’ has undoubtedly shaped and formed how protest movements in Iraq (and indeed regionally) are constituted. There is a rootedness in the identity politics of the region, a ready-made framework within which these divisions are articulated. One challenge in providing historical backdrops to still unfolding stories of state-crafting is that history itself remains a project, one in which there are competing claims to hegemonic discourse, the defining version of events which captures the social formation of a state (Castellino & Cavanaugh). It is in these ‘memories of state’ and state crafting that the politics of sectarianism in Iraq are rooted and ten years on from the invasion of Iraq, they continue to play out.

The tenth anniversary of the invasion of Iraq has attracted relatively little international attention or much needed reflection, yet its remnants are woven into a geography of violence that penetrates the legal, political, and social spheres in Iraq. Politically, Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki has used the past seven years to consolidate his power. During his time in office, his strategic and micromanaging skills have served him well. He has deployed state resources to cement loyalty and outmanoeuvre political opposition, and has undermined newly created independent institutions and brought them under his direct control. Although he has indicated that he will not run for another term, much like Kurdish leader, Masoud Barzani, al-Maliki appears to be grooming his son for succession.

Yet there are cracks in al-Maliki’s power base and despite significant popular support in the polls, political challenges to his increasingly authoritarian rule and his Baghdad centred governance (and policies) are growing. In local elections held earlier this month, al-Maliki’s State of the Law List secured only 97 of 378 seats on the governorate councils, preventing him from forming key local governments. Two major Shi‛a rivals, the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (ISCI), led by Ammar Al-Hakim, and the Sadrist Trend of Muqtada Al-Sadr, secured 124 seats and went on to form local coalition governments in Baghdad and several other southern provinces after reaching agreements with Sunni lists and blocs representing a mix of secular and minority groups (which secured the remainder of the 378 seats). This shift in power at the local level suggests that al-Maliki’s regime is far from secure in the run up to the 2014 general elections.

Within the legal landscape, despite notions of equality and rights embedded in the 2005 Iraqi Constitution and its accession to the UN Convention Against Torture in 2011, serious human rights violations remain, including the arrest and detention of persons “for prolonged periods without being charged and without access to legal counsel [as well as] prisoner and detainee abuse and torture.” Although quite significant investment has been made by the EU (and UN) to train police in forensic evidence gathering, the Iraqi Judiciary are reluctant to accept anything other than confessional-based evidence, ensuring that the practice of torture and ill treatment in detention stays firmly rooted.

Since the United States withdrew in 2011, Iraqi civil society has endured crisis after crisis. Iraq’s economy and infrastructure especially in rural areas are weak and the prospect for economic prosperity is “subject to significant risks, deriving mainly from institutional and capacity constraints, oil prices volatility, delays in the development of oil infrastructure, and an extremely fragile political and security situation.” While the sectarian violence that followed the 2003 invasion of Iraq started to ebb in 2008, the internal (resource, security, political infighting) and external (Syria) pressures have led some commentators to openly fear a return to a full scale civil conflict in Iraq.

These forensics leave little question that ten years after the US invasion, what remains is not just a democratic deficit in Iraq, but a society and political system that is fractured and bruised. Change is necessary to prevent further (and deeper) conflict in Iraq. Who is best placed to build a political community that transcends the ethnically divided political map in Iraq? Al-Sadr appears to be the favoured contender, having reshaped his public profile from a military to political leader. Whatever leadership emerges in 2014, shedding historical hangovers and reimagining a political community that counter and undo the politics of sectarianism, in practice and discourse, will be a formidable task. Yet in this country ‘lost’ to war, these are critical first steps along the road to finding what Iraqi poet Dunya Mikhail calls ‘homeland’.

Kathleen Cavanaugh is currently a Lecturer of International Law in the Faculty of Law, Irish Centre for Human Rights (ICHR), National University of Ireland, Galway. She has recently co-authored Minority Rights in the Middle East with Joshua Castellino (OUP 2013). Read her previous blog post “Moralizing states: intervening in Syria.” The title of this post from I Was in a Hurry, by Dunya Mikhail, translated by Elizabeth Winslow, from The War Works Hard, copyright 1993, 1997, 2000, 2005 by Dunya Mikhail.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in Public International Law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Cross by Caroline Jaine.

The post ‘Yesterday I lost a country’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOil and threatened food securityThe strengths and limitations of global immunization programmesMoralizing states: intervening in Syria

Related StoriesOil and threatened food securityThe strengths and limitations of global immunization programmesMoralizing states: intervening in Syria

The strengths and limitations of global immunization programmes

Modern vaccines are among the most powerful tools available to public health. They have saved millions of lives, protected millions more against the ravages of crippling and debilitating disease, and have the capacity to save many more. But like all complex and sophisticated tools, they can be used for different purposes, in different ways, and with various consequences.

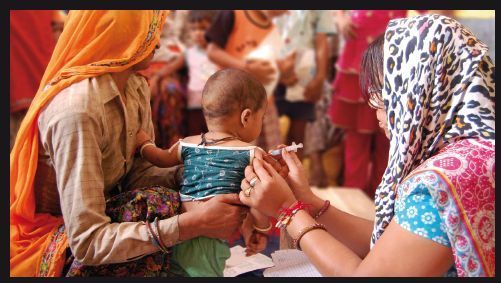

Children getting their vaccines from a nurse at the government preschool centre in their village. Photo by Dagrun Kyte Gjøstein

When polio eradication was proposed as a global objective, in the late 1980s, it was vigorously debated. No one doubted the power of the polio vaccine to protect children. But experts differed in how they thought it should best be used. Some have regarded vaccination programmes as a means of strengthening primary health care, whilst others have seen them as likely to divert attention and resources from needed improvements in health services. At issue in such debates is not the immunological properties of a vaccine, but the way in which it should best be used. Taking the health care needs of children, and especially those whose health is most at risk, as the key objective, how should vaccines best be deployed?

The question is even more relevant today, as more and more new vaccines are becoming available, and huge financial resources are being deployed to promote global immunisation. These donor-funded programmes now account for a major part of the effort devoted to improving the health of children in developing countries.

Three distinctive, but interrelated, trends can be identified in international public health in recent years:

A growing reliance on health technologies, and on vaccines in particular;

A global perspective that is increasingly taken for granted;

Quantifiable targets, and especially the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), play a very important role.

Health policy makers at national level are expected to implement global immunisation programmes in a standard manner and report progress according to standard indicators. Pressures and incentives to meet the targets set are then transmitted down to the community level health worker who actually meets the parents and children to implement these programmes.

Today, despite continuing or even increased talk of ‘country ownership’, there are growing demands for performance accountability, reflected in demands for measurement of performance — not just outputs, but also outcomes and impacts — based on objective quantitative indicators. The MDGs have contributed to the process. One of the attractions of vaccines is precisely their measurability: both as regards specifying targets and measuring achievement. Dividing the number of vaccines distributed by the number of children of the appropriate age in the target population is made to yield two simple but powerful numbers: percentage coverage, and number of lives saved

Although we are not questioning the intentions of global actors who contribute to this situation, we do note that the effect of their actions is to strengthen the ‘verticality’ in the global health system. In this system money, and vaccines themselves, emanate from the global level and travel down from national to district and to village levels, accompanied by technical advice, exhortation and targets to be achieved. In return — up the chain, emanating from the most local level — come reports on performance, and measures of achievements, expressed in terms of numbers of children vaccinated. In this way, not only is the autonomy of national governments reduced, their accountability may even be reversed. Instead of being accountable ‘downwards’ to their citizens, they become accountable ‘upwards’ to global actors.

Protecting the World’s Children. Photo by Dagrun Kyte Gjøstein.

The need to show progress can create distortions and lead to the production of misleading data, and an unwillingness to report problems. Vaccines could more effectively serve children’s health needs if immunisation programmes were better understood and acknowledged, and if local knowledge and realities were enabled to inform national and international health policy.

Desmond McNeill is co-editor, along with Sidsel Roalkvam and Stuart Blume, of Protecting the World’s Children: Immunisation policies and Practices (2013). He is Professor, and former Director, at SUM, the Centre for Development and Environment at the University of Oslo. He heads the research area on Governance for Sustainable Development, and is Director of SUMs Research School. He has worked in over 15 developing countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America and written extensively on aid and global governance.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Photographs © Dagrun Kyte Gjostein, all rights reserved.

The post The strengths and limitations of global immunization programmes appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHomicide bombers, not suicide bombersOil and threatened food securityWorld Hepatitis Day 2013: This is hepatitis. Know it. Confront it.

Related StoriesHomicide bombers, not suicide bombersOil and threatened food securityWorld Hepatitis Day 2013: This is hepatitis. Know it. Confront it.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers

![Shai le-Sara Japhet: Studies in the Bible, Its Exegesis and Its Language [Hebrew] Bar-Asher, Moshe, Dalit Rom-Shiloni, Emanuel Tov and Nili Wazana, editors. Jerusalem: Bialik Institute, 2007](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1387651021i/7642805._SY540_.jpg)