Oxford University Press's Blog, page 915

August 9, 2013

A children’s literature reading list from Oxford World’s Classics

By Kirsty Doole

For many of us that love reading, the seeds are sown in childhood through the books we read or have read to us. Children’s literature was the inspiration for this month’s Oxford World’s Classics reading list and below is just a selection of many classics of the genre that are out there. What were your favourites? Let us know in the comments.

Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens / Peter and Wendy by J. M. Barrie

Peter Pan, the boy who refused to grow up, is an exploration of eternal youth created by J. M. Barrie. This work deals with Peter as an infant who was, we learn, “part-bird”. After overhearing a discussion about his future, adult life, he escaped by flying out the window, and took refuge in Kensington Gardens. He meets a little girl who is lost called Maimie Mannering, a character who prefigures Wendy Darling in Barrie’s later ‘Peter and Wendy’.

The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett

The Secret Garden is surely one of the most famous and well-loved of children’s classics. It tells the romantic story of the regeneration of two sickly, spoiled children, Mary Lennox and her cousin Colin, through contact with nature. After she discovers the secret garden, Mary Lennox gradually becomes a healthy, unselfish girl who in turn redeems both Colin and his gloomy, Byronic father. Frances Hodgson Burnett’s inspiring story of salvation gently subverted the conventions of a century of romantic and gothic fiction for girls.

J. M. Barrie (as Hook) with Michael Llewelyn Davies (as Peter Pan) in August 1906

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass by Lewis Carroll

On first glance, the ‘Alice’ books are delightful, innocent fantasies for children, but on further inspection they are also full of complex mathematical, linguistic, and philosophical jokes. Alice’s encounters with the White Rabbit, the Cheshire-Cat, the King and Queen of Hearts, the Mad Hatter, Tweedledum and Tweedledee and many other extraordinary characters have made them masterpieces of nonsense, yet they also appeal to adults through the layers of satire, allusion, and symbolism about Victorian culture.

Tom Brown’s Schooldays by Thomas Hughes

Tom Brown’s Schooldays by Thomas Hughes was one of the earliest books written specifically for boys. A true Victorian classic, it has long had an influence well beyond the public school world that it describes. An active social reformer, Thomas Hughes wrote with a tolerance which keeps this novel refreshingly distinct from other schoolboy adventures.

Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson

An old seaman arrives at the Admiral Benbow inn, where the landlady’s son, Jim Hawkins, manages to get hold of his treasure map. Jim gives it to Squire Trelawney and the Squire and his friend Dr Livesey set off for Treasure Island in the schooner Hispaniola, taking Jim with them. Some of the crew are the squire’s faithful dependants, but most are old buccaneers recruited by Long John Silver. This famous tale by Robert Louis Stevenson is arguably a reinvention of the adventure story genre, a boys’ story that appeals as much to adults as to children, and whose moral ambiguities turned the Victorian universe on its head.

The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame

An international children’s classic, The Wind in the Willows grew from the author’s letters to his young son. It is a celebration of the English riverside through the characters of Mole, Rat, and Badger, whose humanization seems to confirm their natural forms and habitations—Rat’s love of the river, Mole’s shyness and simplicity, Badger’s gruffness and solidity—while giving their adventures familiarity. Perhaps surprisingly for a story usually associated with children, it is concerned almost exclusively with adult themes: fear of radical changes in political, social, and economic power. A profoundly English fiction, it is, Peter Hunt argues in the Introduction, a book for adults adopted by children. It is also a timeless masterpiece, and a vital portrait of an age.

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum

L. Frank Baum’s fantasy was named after the O–Z drawer in his filing cabinet. Dorothy and her dog Toto are transported to bright, colourful Oz, where Dorothy accidentally defeats the Wicked Witch of the West, and with her companions, a Tin Man, a Scarecrow, and a Cowardly Lion, is tricked by the ‘Wizard’ (a ‘Great Humbug’) into finding their missing desires (heart, brain, courage, and Dorothy’s Kansas home). Published at the beginning of the last century, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz immediately captivated both children and grown-ups.

Kirsty Doole is Publicity Manager for Oxford World’s Classics, amongst other things.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, and the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Photograph of J. M. Barrie (as Hook) and Michael Llewelyn Davies (as Peter Pan). By Unknown, presumably Sylvia Llewelyn Davies [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post A children’s literature reading list from Oxford World’s Classics appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe misfortune of AthosWhy we should commemorate Walter PaterThe first branch of the Mabinogi

Related StoriesThe misfortune of AthosWhy we should commemorate Walter PaterThe first branch of the Mabinogi

Honouring treaty and gender equality

In Canada, there are almost 600 documented cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women over the last 20 years. The Canadian government has continuously refused to hold a national public inquiry into the missing and murdered women, despite mounting international and domestic pressure to do so. Given the paucity of the existing domestic framework, international human rights and transnational activism might have a role in pressing for social justice for the “Stolen Sisters” or “Sisters in Spirit”. As the headline of a 2012 article in the Indigenous newspaper, Windspeaker declared: “UN to do the job that Canada will not.”

Source: APTN news.

The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples proclaims the importance of all human rights for all Indigenous peoples and, as stated in the preamble, these rights are claimed in the context of the dispossession of lands and resources, and the need for self-determination and respect for Indigenous knowledge, culture, and tradition. Article 22 of the Declaration states the right of Indigenous women and children to “enjoy the full protection and guarantees against all forms of violence and discrimination.” In the case of the Stolen Sisters, Article 22 underscores the racialized and gendered nature of Canada’s failure to live up to its formal obligations under the Convention to Eliminate All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and other legally binding international treaties.

Justice for the Stolen Sisters, moreover, relates to honouring treaty in the sense of the Two Row Wampum. The Kaswentha from the Haudenosaunee (or Six Nations) people is a sacred wampum belt that embodies “principles of Peace, Friendship and Mutual Respect.” It is a symbolic record of the first agreement between Europeans and Indigenous peoples on Turtle Island (North America), and it formed the basis for numerous treaties between Haudenosaunee and non-Haudenosaunee. The two rows of purple beads are said to symbolize two separate vessels travelling parallel to one another down the “River of Life.”

Source: Two Row Wampum Renewal Campaign.

The history of colonization in Canada evidences a tradition of terrible disregard for the principles of the Two Row Wampum. For instance, the Indian Residential School system sought forcibly to assimilate Indigenous children through the destruction of language and culture, a genocidal project that aimed to “kill the Indian in the child.” The schools were rampant with sexual and physical abuse, malnutrition, loneliness, and neglect. The impact of the Indian Residential School system on Indigenous communities and families over one hundred years has been profoundly negative. “Many [family members] spoke of the resulting family dysfunction or disconnect as impacting their lives and placing the women in a vulnerable situation,” write Beverley Jacobs and Andrea J. Williams in their chapter in From Truth to Reconciliation. In most cases concerning Stolen Sisters, their parents or grandparents attended Indian Residential School.

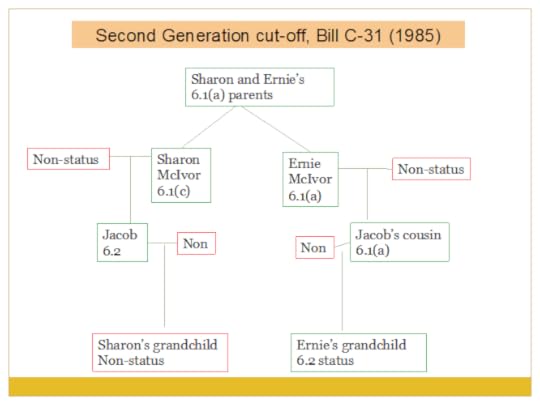

Furthermore, many of the missing women “had been displaced from their community due to the impacts of the genocidal policies of the Indian Act.” The 1876 Indian Act, which controls almost every aspect of First Nations’ land and governance, greatly reduced the strength of Indigenous women and Indigenous matrilineal systems. In granting “Indian status” through a patrilineal system, the Indian Act effectually reduced the number of “status Indians” every time a woman “married out.” In 1985, the Indian Act was amended following a 1981 ruling against Canada at the United Nations Human Rights Committee (Lovelace v. Canada). Although this amendment resulted in the reinstatement of status for thousands of women, the “second-generation cut-off” continues to deny status and therefore treaty rights to the grandchildren of some of these women. For this and other reasons, Mi’kmaq professor and activist Pamela Palmater estimates that some First Nations will be “legally extinct” within 75 years. Sharon McIvor is currently petitioning the United Nations after having partially lost her Supreme Court challenge against gender discrimination in the Indian Act (she also contests the 2010 amendments in Bill C-3).

Under Section 6 of the Indian Act, people are accorded different levels of status. Sharon’s grandchild loses status, while her brother’s grandchild retains status.

The international arena provides a variety of venues for investigation into the Stolen Sisters. Here is where the UN may do the job that Canada will not:

Universal periodic review of Canada’s overall human rights record at the UN Human Rights Council in April 2013

A hearing at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights on 28 March 2012 and a planned visit to Canada

A planned visit to Canada by the CEDAW committee (the UN committee that monitors the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women)

A planned visit by the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples

Discussions and an expert study on violence against Indigenous women at the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues

Canada voted against the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007, as did the United States, Australia, and New Zealand. While all four settler states have now belatedly endorsed the Declaration, they repeatedly emphasize its “aspirational” and legally “non-binding” character. Despite an historic apology by the Prime Minister of Canada in 2008 for Indian Residential Schools, the government continues to give short shrift to the broader context of colonization in which the schools existed.

As the Native Women’s Association of Canada writes in its report on the Sisters in Spirit Initiative, “to truly address violence against Aboriginal women, it is necessary to support the revitalization of our ways of being.” This revitalization speaks to the core principles behind the UN Declaration, the ongoing need for settler states to decolonize their legal, bureaucratic and social structures, and a return to the principles of the two-row wampum.

The theme of this year’s International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples is “Honouring Treaty.” Canadians and the international community can take actions today in order to respect and fulfill both contemporary and historic agreements that form the basis for right relationships. These actions include righting the racialized gender discrimination that lies at the core of the colonial project.

Rosemary Nagy is an associate professor of Gender Equality and Social Justice at Nipissing University in the traditional territory of Nipissing First Nation. She is the author of a number of articles on internationalized transitional justice, including “The Scope and Bounds of Transitional Justice and the Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission” (available to read for free for a limited time). Her work has been published in The International Journal of Transitional Justice, Law and Society Review, and Third World Quarterly.

The International Journal of Transitional Justice publishes high quality, refereed articles in the rapidly growing field of transitional justice; that is the study of those strategies employed by states and international institutions to deal with a legacy of human rights abuses and to effect social reconstruction in the wake of widespread violence.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Honouring treaty and gender equality appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesUNDRIP, CANZUS, and indigenous rightsAssembling a coherent picture in the Daniel Pelka caseHuman rights education and human rights law: two worlds?

Related StoriesUNDRIP, CANZUS, and indigenous rightsAssembling a coherent picture in the Daniel Pelka caseHuman rights education and human rights law: two worlds?

A lost opportunity for sustainable ocean management

By Philip Mladenov

A swarm of Krill fish

Russia has recently blocked the creation of two of the world’s largest marine protected areas at a special meeting of the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) in Bremerhaven. These marine reserves would have been massive — covering more than 3.5 million square kilometres of the Southern Ocean off the coast of Antarctica. This represents a tragic lost opportunity to forge a seminal deal in support of international ocean conservation — a deal which would have established the foundations for a more rational approach to how we manage our ocean environments.To put this lost opportunity into perspective, it is first important to acknowledge that there has been exploitation of Southern Ocean marine resources for hundreds of years, which belies the commonly espoused notion that Antarctica possesses one of the planet’s last pristine marine systems. Southern Ocean marine mammals were ruthlessly exploited in the past. Fur seal hunting began in the late 1700s and by 1830 most fur seal colonies had been exterminated or reduced to a size where it was uneconomical to continue to hunt them. Antarctic whaling commenced in the early 1900s, initially targeting humpback whales, then spreading rapidly to other species. In the years before the Second World War tens of thousands of whales were taken annually — some 631,518 whales were officially recorded killed in the period between 1956 and 1965 alone. The industry collapsed in the 1960s when it became uneconomical to hunt the remnant populations of whales that remained.

The exploitation of Antarctic marine species then moved down the food web to target smaller animals. Commercial fishing began in the late 1960s, first focussed on species such as the mackerel icefish. In the 1980s fishing vessels began to exploit the Patagonian toothfish at depths of around 1,000 metres. This fishery has recently expanded to a related species, the Antarctic toothfish. Antarctic toothfish are food for sperm whales, killer whales, Weddell seals and large squid, so their removal will potentially impact on these dependent species. Even the krill in the Southern Ocean — the core of the food web — are subject to human exploitation. Antarctic krill fishing began in the 1970s and by the early 1980s about half a million tonnes were being harvested annually. Catches then declined to around 100,000 tonnes per year as most nations abandoned the fishery because of the high cost of operating in the Southern Ocean. However, the demand for krill appears to be increasing again. Krill are being caught, and processed into fish meal, and used as a source of health food supplements, such as omega-3 oils.

A group of crabeater seals

This litany of human impacts has undoubtedly pushed the Antarctic marine system out of its natural equilibrium, although it has been difficult to document the changes because of Antarctica’s remoteness and the lack of an historical baseline of what is “natural” in the Southern Ocean. That being said, no parts of the Global Ocean are anymore pristine and, compared to other parts of the Global Ocean, the Southern Ocean remains a relatively healthy and intact ecosystem in a state of recovery and one well worthy of having significant areas placed under international protection. Furthermore, and perhaps more importantly, conservation of parts of the Southern Ocean will contribute to a much needed global system of marine protected areas that will pay big dividends in future in terms of sustainable production of seafood for a rapidly growing human population. This is because marine protected areas are beneficial to the recovery of commercial fisheries through “spill over” effects.

It is sobering to compare the efforts we put into protection of terrestrial environments compared to marine environments. We take national and regional parks and protected areas on land for granted as a prudent requirement for preservation of significant and representative areas of terrestrial wildlife and landscape in the face of growing human pressures. At this time about 12% of the planet’s land area is now under some form of protection. The corresponding figure for the oceans is well less than 1%, with most of this area still open to some form of exploitation. The area of the oceans where human exploitation is completely restricted is miniscule, consisting of a small number of scattered “no-take” marine reserves.

Humpback Whales in the Gerlache Strait, Antarctica

How much of the Global Ocean do we need to protect in order to allow sufficient over-exploited marine systems to recover and contribute to a more sustainable marine harvest? The consensus among marine scientists is that somewhere in the vicinity of 20%-40% of the oceans need to be protected to maximise the amount of food we can harvest from the oceans. This means we would need roughly 50 times the area presently under protection.

The actions of Russia were thus very unfortunate and well out of step with what is required to begin to manage our oceans sustainably. No one is really sure why the Russian delegation acted to block this important initiative but it can be speculated that their mandate was to protect Russian fishing interests in the Southern Ocean. A concerted effort is now required to ensure that Russia will have a change of heart when the proposal for protection of parts of the Southern Ocean is considered again at the next meeting of CCAMLR in Hobart in November.

Philip V. Mladenov is the Director of Seven Seas Consulting Ltd and Chief Executive of the Fertiliser Association of New Zealand. He has more than 35 years of professional experience in marine biological research, teaching, and exploration. He is the author of Marine Biology: A Very Short Introduction and some 80 scientific papers and a broad range of popular articles, consulting reports, and government reviews. You can also read his previous post on seamount ecosystems.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only environmental and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Krill Swarm, By Jamie Hall [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons; (2) Crabeater Seals in the Lemaire Channel Antarctica; (3) Humpback Whales in the Gerlache Strait, Antarctica: both by Liam Quinn from Canada [CC-BY-SA-2.0] via Wikimedia Commons

The post A lost opportunity for sustainable ocean management appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow do you study large whales?UNDRIP, CANZUS, and indigenous rights

Related StoriesHow do you study large whales?UNDRIP, CANZUS, and indigenous rights

August 8, 2013

Sound symbolism and product names

In many animal communications, there’s a transparent link between what is being communicated and how that message is communicated. Animal threat displays, for instance, often make the aggressor look larger and fiercer through raising of the hair and baring of the teeth. A dog communicates excitement through look and sound.

Human language is different: most words and sentences don’t inherently look or sound like anything in particular. It is only through a conventional and learned association of sounds with meanings that a message is conveyed. That’s why the same animal can be called dog in English, perro in Spanish, chien in French, and hund in German. And that’s why a human can sit in a dark movie theater and quietly whisper, “That’s exciting!” or stand on a hiking trail and calmly say “Freeze; there’s a rattlesnake just ahead.”

But some words in human language do resemble what they mean. Think about crinkly and crispy, smooth and satin. This phenomenon is known as sound symbolism and it has been observed in many languages. People who are shown word pairs of an unfamiliar language can guess above chance which word would refer to something that is, say, crinkly vs. smooth. The links between sound and meaning apply to vowels as well as consonants. High-pitched vowels, made toward the front of the mouth, tend to be associated with things that are thin and light. Lower-pitched vowels, made toward the back of the mouth, tend to be associated with things that are large and heavy.

Linguist Dan Jurafsky has shown that the food industry imbues food names with this sort of sound symbolism. He found that commercial ice creams, which gain market share by being known as rich and creamy, tend to use more names with back vowels (consider rocky road, Jamoca almond fudge, chocolate, caramel, and so on). On the other hand, crackers, which are products meant to be crisp and crunchy, tend to use names with front vowels (consider Cheez-Its, Ritz, Krispy, Wheat Thins). So sound symbolism is not a vestige of long-ago days when human language emerged from some more primitive form of communication. It is commonly and productively used in creating names for things in the modern world.

But are marketing departments full of former linguistics majors who learned their lessons about sound symbolism well? Jurafsky’s research didn’t address that question. More likely, the link between sound and meaning is reinforced by focus groups that reliably prefer certain types of names for certain types of products. Not every product has the benefit of such vetting of names, though. Cars like the Edsel and Gremlin may have helped sealed their own fate as sales disasters by having the wrong vowels in their names.

Barbara Malt is a Professor of Psychology at Lehigh University. She is the Associate Editor of the Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition and a co-editor of Words and the Mind: How Words Capture the Human Experience. She is interested in language, thought, and the relation between the two.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Caramel nut ice cream by Lotus Head. Creative commons license via Wikimedia Commons.

The post appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAlphabet soup, part 2: H and YFive things to know about my epilepsyThe impact of a dementia treatment

Related StoriesAlphabet soup, part 2: H and YFive things to know about my epilepsyThe impact of a dementia treatment

In memoriam: George Duke

When a famous musician dies, journalists reach for a handle, some short phrase to summarize what a performer did to gain a dose of fame. Keyboardist George Duke, who died on Monday at age 67, resists such pigeonholing.

Most of the published tributes call Duke a jazz musician, and he certainly left his mark on that idiom. But I first heard George Duke in a rock band—and one of the best rock bands of all time. As a sideman with Frank Zappa, Duke participated on a series of pathbreaking albums from the 1970s. If you evaluated rock LPs on musicianship and sheer bravado, albums such as Waka/Jawaka, The Grand Wazoo, and Roxy & Elsewhere, Duke would have earned double-platinum status long ago. Zappa sold more records in the 1980s, when he dished out “Valley Girl” and other humor-driven bits of musical cynicism, but I’ll take the albums with Duke over any of those later efforts.

I also admired Duke’s work with violinist Jean-Luc Ponty, another Zappa sideman with deep jazz credentials, and his projects with Miles Davis are classics of late-stage jazz-rock fusion. But Duke was equally comfortable with pop, even with the King of Pop—you can hear him on Michael Jackson’s “Off the Wall.” He also worked with Phil Collins, Jeffrey Osborne, George Clinton, and even kept it in the family with his cousin, vocalist Dianne Reeves. Duke could fit in with old school jazz performers such as Harry “Sweets” Edison and Marian McPartland or match the groove with Brazilian artists Milton Nascimento and Flora Purim. He was most famous for his synthisizer work, but he could also sing, produce, compose, or do whatever else it took to turn vinyl into gold. And when he wasn’t playing the music, others were sampling what he had played in the past. You can hear his borrowed licks on tracks by everyone from Kanye West to Daft Punk.

Then, of course, we have the albums under his own leadership—around 40 releases that built a huge following for Duke with their pleasing mix of funk, R&B, pop and jazz. Just a few days before his death, Duke released Dreamweaver, a musical tribute to his late wife Corine who died a year ago. But now Dreamweaver will also be heard by fans as a posthumous celebration of Duke himself. The song “Missing You” from the album very much sums up the feeling his many fans are experiencing today. He will continue to be missed, but in the music business, where it’s always hit or miss, George Duke will be remembered even more for the hits.

George Duke

12 January 1946 – 5 August 2013

Ted Gioia is the author of eight books on music, including The History of Jazz and The Jazz Standards.

Image credit: George Duke and Miles Davis in 1986 at Montreux Jazz Festival. Photo by Dr Jean Fortunet. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

The post In memoriam: George Duke appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIn memoriam: George DukeFive quirky facts about Harry NilssonThe Clooneys and the Kennedys

Related StoriesIn memoriam: George DukeFive quirky facts about Harry NilssonThe Clooneys and the Kennedys

UNDRIP, CANZUS, and indigenous rights

In recent weeks, the Global Indigenous Preparatory Conference for the United Nations High Level Plenary Meeting of the General Assembly convened in Alta, Norway and released its comprehensive ‘Outcome Document’. The document has met with resounding indifference. That result might have been expected. For while indigenous representatives and international bureaucrats have developed a customary practice of international assembly and proclamation, what they say in New York, Geneva, or wherever has little consequence for, and less effect upon, most indigenous peoples in the places where they actually live and work.

In marking International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples on the 9th of August, we should reflect critically upon the significance of international indigenous politics. To illustrate, if we consider the sacred text of international indigeneity, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, questions remain as to whether this document is worth the energy expended upon it.

Of course, one can exaggerate UNDRIP’s limitations, but these are particularly apparent in the so-called ‘CANZUS’ group of Anglo-settler democracies (Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States). These states all voted against the Declaration in 2007 and then subsequently endorsed it, Australia in 2009 and the rest in 2010. Each of those endorsements emphasized that UNDRIP is an aspirational document that would inspire but not change the legal, economic, social, or political circumstance of indigenous peoples.

It comes as no surprise then to find that the UNDRIP and other international statements on the subject — not to mention days of celebration — have not substantially influenced the agendas of indigenous politics in the settler states. Rather, the political claims of indigenous peoples and state responses to them are shaped by particular politics, histories, and institutions.

In Australia, for example, the federal government’s response to the abuse and neglect of children in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities has dominated indigenous politics since 2007. The conservative government of John Howard introduced the Northern Territory Intervention, sending armed forces into indigenous communities as part of an ‘Emergency Response.’ This highly controversial policy has been continued in only slightly modified form under Labor. Critics claim that the policy denies the autonomy of indigenous Australians and constitutes an attempt, in the guise of protecting human rights, to re-enforce federal control over Aboriginal land in the wake of the 1992 Mabo decision.

Australia: Aboriginal Culture 002. Photo by Steve Evans from Citizen of the World. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

In New Zealand, indigenous politics are driven by the institutional processes of the Waitangi Tribunal, which hears the claims of Māori and recommends on them based on the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi. The Treaty is interpreted to guarantee Māori control over Māori affairs, but in a manner which falls short of complete self-determination. Intertwined with Treaty politics are the politics of Māori political representation, both the guaranteed seven Māori electoral seats in New Zealand’s parliament and the Māori Party (currently in coalition with the conservative, National-led government).

Turning to North America, in Canada the unfolding Indian Residential School Settlements Agreement, and in particular the ongoing Truth and Reconciliation Commission, dominates indigenous politics. Canada’s TRC is investigating the legacy of the residential school system through which the government forcibly removed indigenous children and incarcerated them within a systemically abusive, underfunded, and assimilative education system.

And finally, in the United States, a polity with a constitutional allergy to international institutions, indigenous politics remain, as they have been for some time, oriented around and within particular tribal relationships. The struggles to gain recognition as peoples, to secure fair terms of economic and political existence, and to flourish in the future are carried out within the frameworks of local, state, and federal politics.

Looking at the primary engines of indigenous politics in the CANZUS group, it is clear that global indigenous institutions play merely supportive roles. Moreover, although academics and indigenous elites discuss global ‘norms of indigeneity’ and the benefits of global communications, strategy-formation and mutual moral support, there is an inevitable tension between global focus and the lived experience of indigenous peoples in terms of their local connections to land, community, and political institutions. Indigenous politics are fundamentally national, or even sub-national, politics as indigenous people define themselves in terms of particular political struggles in postcolonial states.

In light of those thoughts, the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples and similar events serve a salutary hortatory purpose by reminding us of the moral values and principles that underlie indigenous political claims. However, in terms of politics that matter to people, they fall into the political category of ‘nice to have’ but inessential.

Stephen Winter is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Political Studies at the University of Auckland. He is the author of “Towards a Unified Theory of Transitional Justice” (available to read for free for a limited time) in the International Journal of Transitional Justice. Katherine Smits is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Political Studies at the University of Auckland.

The International Journal of Transitional Justice publishes high quality, refereed articles in the rapidly growing field of transitional justice; that is the study of those strategies employed by states and international institutions to deal with a legacy of human rights abuses and to effect social reconstruction in the wake of widespread violence.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post UNDRIP, CANZUS, and indigenous rights appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAssembling a coherent picture in the Daniel Pelka caseHuman rights education and human rights law: two worlds?‘Yesterday I lost a country’

Related StoriesAssembling a coherent picture in the Daniel Pelka caseHuman rights education and human rights law: two worlds?‘Yesterday I lost a country’

Five things to know about my epilepsy

Seeing as I was diagnosed with epilepsy more than half my lifetime ago, I can’t remember what it’s like not to know about it. Despite being the most common serious neurological condition in the world, there is still a surprising number of misconceptions surrounding it.

(1) Should I put a spoon in your mouth?

This question, or variants of it, is the one I get asked most often. It stems from the misunderstanding that you can swallow your tongue when having an epileptic seizure. But the tongue is attached, so therefore incredibly unlikely that you could swallow it.

So the simple answer? No, definitely not. Please don’t put a spoon, your fingers, or anything else, into my mouth. I will bite it, and bite it hard — with the strong likelihood of hurting you — and the spoon. And trust me, a sore tongue is better than a friend who isn’t talking to you because you made them bleed.

(2) What does it feel like to have a seizure?

There are many different kinds of seizures, and they can feel different to different people. The most well-known seizure is the one people associate with falling to the ground and ‘foaming at the mouth’. The technical name is tonic-clonic (or grand mal) and is a seizure I have experienced many times.

I find that I cannot recall the majority of the seizure. What I generally remember is the aftermath: I feel like I’ve run a marathon (not that I’ve ever run a marathon), my body aches, and I’ve normally bitten my tongue. I can feel a bit woozy but it doesn’t take me long before I’m absolutely fine again.

(3) Does epilepsy mean you can’t go to nightclubs?

No, it doesn’t mean that. Some people with epilepsy (and only some) are photosensitive which means that certain patterns of light can trigger a seizure. Strobe lights are often found in nightclubs, and so this can limit the ones I go to, but the medication I take should also control the photosensitive aspect of my epilepsy.

In 2010, Jane won a YoungScot award for continually working to improve awareness of epilepsy

Strangely, covering one eye when confronted with a strobe light means I will not have a seizure — as both eyes need to see the light. This meant that in university, my friends and I invented a rather fetching ‘one eye dance’ which meant we could all keep dancing without fear of seizures.

(4) What should I do if you have a seizure?

If we take this question to mean a tonic-clonic seizure, then my answer is generally along the lines of ‘do nothing’. Tonic-clonic seizures do look very scary (I wouldn’t want to see myself have a seizure) but the key thing to remember is this is what epilepsy means and entails: the reoccurrence of seizures. I am not in any harm when I am mid-seizure.

Generally, as a rule, you should never move or try and restrain someone who is having a seizure — unless they’re at risk of causing themselves further harm (for example if they started having a seizure at the top of a staircase or at the edge of a cliff). Time the seizure and if it lasts more than five minutes phone an ambulance, but generally they will last no more than two minutes (though it can feel like a lifetime). Stay with the person and reassure them of what has happened. They may be very confused (I have been known to ask my mum who she is).

(5) What triggers your seizures?

All kinds of things can trigger seizures in people with epilepsy but for me, the most common trigger by far is a lack of sleep. More specifically, my seizures are triggered when my sleep pattern is disturbed. For example, I have long been banned from having naps as there is no guarantee that when having a nap, the phone won’t ring, the postman won’t knock at the door, or the next door neighbour won’t decide to start renovating their house — and these disturbances could trigger a seizure for me.

However, on the plus side, there is a huge range of medications that control seizures and for many people, if taken correctly, their seizures stop. I am one of these lucky people, and most days, I completely forget that I have epilepsy. It’s just a case of remembering to take my medication!

In the 12 years since my diagnosis, I have found that reading and learning about epilepsy is the best way of knowing how to cope with it. When friends ask about it, I can answer with confidence and I have often found if I am not scared, then neither are they. Although seizures can be frightening, when you know what they are, why they are happening and how to deal with them, much of the fear disappears.

Jane Williams is a Marketing Executive at Oxford University Press. She was diagnosed with Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy at 12 years old.

The Facts series gives clear, straightforward, and practical advice about a range of medical conditions and topics. It provides the essential facts for both patients and their families wishing to go beyond the information available from busy doctors, or simply not sure of the right questions to ask. The two books available on epilepsy in this series are Epilepsy and Epilepsy in Women, which address all aspects of epilepsy, at all ages.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Photo: Jane with her YoungScot award for continually working to improve awareness of epilepsy. All rights reserved.

The post Five things to know about my epilepsy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe impact of a dementia treatmentWhat is “toxic” about anger?Psychiatry and the brain

Related StoriesThe impact of a dementia treatmentWhat is “toxic” about anger?Psychiatry and the brain

August 7, 2013

Alphabet soup, part 2: H and Y

This is a story of the names of two letters. Appreciate the fact that I did not call it “A Tale of Two Letters.” No other phrase has been pawed over to such an extent as the title of Dickens’s novel.

The letter H.

The name aitch stands out. We observe the usual vocalization of letter names in Engl. B (bee), K (kay), S (es), German H (ha; at the end of the tenth century, ha was still the name of H in Latin, and in the twelfth century an Icelandic grammarian called H the same), and Italian F (effe). But aitch? What does H, which designates aspiration, have to do with ch, a sound belonging with affricates (to use a special term), that is, with kh, ts, dz, j (as in jay), and pf? And why ai-? Strangely, the answer is not quite clear, though the name of any letter can be expected to have a transparent origin.

The older explanation presupposes that at one time Latin had the form accha or ahha, with aitch being its descendant. But as long ago as 1892 a more convincing etymology was proposed by the American linguist Esther S. Sheldon. It was developed and improved by Horst Weinstock, a contemporary German historian of the English language and an expert in old scripts.

The reconstructed name ahha looks like ha with a and ha reversed, h doubled for an unexplained reason, and another a added for vocalization. Yet, as we have seen, long after the collapse of the Roman Empire the name was still ha in the Germanic part of medieval Europe. If the reconstructed ahha arouses suspicion, accha inspires even less confidence, for where did c come from? Yet its legitimacy cannot be doubted, for Italian acca, Spanish ache, and English aitch presuppose the sound of k as its source (English ch in old words always goes back to k: so church, child, each, birch).

An alphabet is a sequence of letters, and rules exist in many cultures to help learners memorize it. Songs like A, B, C, D, E,—you are in the jungle in a coconut tree or X, Y, Z, now we know the alphabet are well-known. It appears likely that medieval Romance learners, while memorizing the part of the alphabet beginning with H, skipped the vowel I (J did not exist at all), so that H and K found themselves in close proximity. Their closeness produced the sound complex HAKA. Since initial h was lost nearly everywhere in the Romance speaking world, haka became aka, of which Italian acca is a natural continuation. It should also be borne in mind that under no circumstances could ha in its capacity as a letter name survive in Romance, for, once h- disappeared, ha (H), merged with the name of the vowel A. The involvement of K in the merger caused minimal trouble, because in the Romance languages K had very low frequency. All the work was done by C; since early times, K appeared only in words of Greek and Germanic origin. Paleographers (students of ancient writing) discovered that alphabets in many Roman manuscripts lack the letter K. (In so far as I never miss the chance of lambasting English spelling, I might as well give a fling to it here too. If we really need both C and K in English, we could at least abolish the difference between skate and scathe and agree that sk would do well for all cases, even—horribile dictu—for skool, that is school.)

Perhaps especially telling is the Portuguese name agá, with its stress on the second syllable. We can assume that in reciting or chanting the alphabet stress was not fixed and vacillated according to the requirements of intonation and rhythm, as it sometimes does in English: compare Ténnessee Wílliams but the státe of Tennessée, fífteen books but Room Fiftéen, goodbye but The Góodbye Girl. Agá is a similar variant of ácca. Nor is the case of Portuguese isolated: accá turned up in Langobardian and Franconian Romania. In Anglo-Norman, the letter H was called hace, which should have yielded Engl. haitch; compare the noun ache: it was pronounced aitch for a long time. The loss of initial h testifies to the influence of Central French. Few etymologies are perfect. The etymology presented above rests on the suggestion that at one time speakers recited the alphabet, with K immediately following H. This reconstruction may not satisfy everybody, but at the moment it is the best we have.

The letter Y.

Some time ago, I wrote a post about the uselessness of the letter Y in English. One of our correspondents asked me about the origin of that letter name. His query suggested the entire idea of my “Alphabet Soup,” which shows that the more questions and comments I receive the better. It turned out that the etymology of wy (the letter name) is even more obscure than that of aitch (h). With very few exceptions (the OED being one of them) dictionaries do not touch on the enigmatic name, and the OED admits that the riddle has not been solved. My etymological database contains only one relevant citation. On 25 October 1895, Skeat gave a talk to the Cambridge Philological Society titled: “On the Origin of the Name of the Letter y and the Spelling of the Verbs ‘build’ and ‘bruise’.” This is what he said. In Anglo-French, the letter was called wi. This is known from a manuscript written about 1210. For rendering Old Engl. y, whose value, when the vowel was long, must have been that of Modern German long ü, as a rule, the scribe used the letter u, but in at least seven instances he substituted the digraph ui for u (herein lies the connection between the main subject of Skeat’s talk and the verbs bruise and build).

I think it will be more profitable if I quote rather than retell Skeat:

“Since in those days the vowel u was not pronounced (as now) like the ew in ‘few’, but like oo in ‘cool’, it follows that the symbol ui must have been called oo-i, or in rapid speech wi [with long i] (formerly sounded as we, not as wy). That is, the name wy denoted ui, a symbol used in Southern English of the thirteenth century to represent the sound of Old English y. If we reverse ui, and write iu, which (pronounced quickly) gives the sound of the ew in ‘few’, we get the present name of the letter U; and it is well known that the modern sound of u in ‘cure’ arose from the Old French u, which was pronounced very like the Anglo-Saxon y. That is, u-i (= wy) gives the name of the Old English y, and i-u (= eu) gives the name of the Old French u sound which resembled it. It follows that the true U, as heard in ‘ruby’ has no name at all in modern English. It ought to be called oo. This result is fairly proved by the fact that two verbs with the spelling ui (for A[nglo]-S[axon] y) still survive in Modern English. These are ‘build’ from A.S. byldan and bruise from A.S. brysan [with long y]. These spellings are the more interesting from the fact that they have never been either understood or explained till now.”

The best etymologies are usually simple, while Skeat’s explanation is rather convoluted, but, obviously, wy could develop only from wi, with long i, that is, from a form sounding like modern wee, and ui is a good candidate for its etymon.

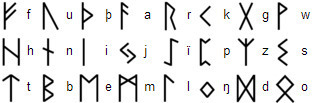

In the picture, you can see the Old Icelandic runic alphabet, the so-called futhark (f-u-th-a-r-k are the first letters of the sequence). The letter for ha (for the purposes of memorization it was called hagl “hail,” noun) is the first in the second row.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: The Elder Futhark table (screencap) via Wikipedia.

The post Alphabet soup, part 2: H and Y appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAlphabet soup, part 1: V and ZMonthly etymological gleanings for July 2013How courteous are you at court?

Related StoriesAlphabet soup, part 1: V and ZMonthly etymological gleanings for July 2013How courteous are you at court?

The impact of a dementia treatment

Dementia is a collection of symptoms caused by a number of different disorders, including neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. The term dementia describes a progressive decline in memory or other cognitive functions that interferes with the ability to perform your usual daily activities (driving, shopping, balancing a checkbook, working, communicating, etc.). One of the major risk factors for developing dementia is age, meaning the older you are, the more likely you are to develop it. Age-related risk applies to many other conditions like heart disease and vascular problems, which means a single person may have two or more concurrent health problems leading to cognitive, behavioral, or motor symptoms. This co-morbidity can make both diagnosis and treatment more complicated.

In the recent study by Michael Hurd of RAND, the estimated prevalence of dementia in people over age 70 in the US in 2010 was 14.7%. They calculated “that dementia leads to total annual societal costs of $41,000 to $56,000 per case, with a total cost of $159 billion to $215 billion nationwide in 2010.” Furthermore, the “aging of the US population will result in an increase of nearly 80% in total societal costs per adult by 2040.” This means an anticipated $73,800–100,800 per adult in 2040. In 2050, the oldest-old are projected to grow from 5.8 million in 2010 to 19 million, with people 85 and over accounting for 4.3% of the of the population (US Census Bureau). As there is no cure for dementia yet, these costs are largely driven by the costs involved in helping people live their daily lives—something that dementia makes progressively harder to do. “The main component of the costs attributable to dementia is the cost for institutional and home-based long-term care rather than the costs of medical services — the sum of the costs for nursing home care and formal and informal home care represent 75 to 84% of attributable costs” (Hurd et al. 2013).

How would a cure change this gloomy forecast? Without attempting to quantify any improvement in quality of life, a cure would have a major impact on these numbers. It is projected that a treatment that could merely delay the onset of symptoms for five years and “began to show its effects in 2015 would decrease the total number of Americans age 65 and older with Alzheimer’s disease from 5.6 million to 4 million by 2020″ (Alzheimer’s Association). This delay would obviously have a huge impact on both the national economy and individual families. A prevention, cure, or reversal of symptoms would have an even larger impact.

There have been many clinical trials for potential Alzheimer’s treatments so far. Sadly, all have failed. Speculation on why these trials have failed has ranged from testing on patients that are too late in the disease to show any improvement to targeting the wrong molecular component of the disease. Scientists from public institutions and universities are currently collaborating through privately-funded consortia to investigate different targets (accumulated tau protein, accumulated beta-amyloid protein, or protein-clearing pathways) and patients with an earlier diagnosis (or even undiagnosed but carrying a gene that means they will develop the disease). If these groups can prove the principle behind a particular therapeutic in a small study, then a larger drug company might be able to take on the complexity and cost of adequate testing for safety and efficacy to develop a widely used therapy. While some of that investment will ultimately be passed back to the patient, the overall benefit should be profound at both the national and individual level.

For the first time, the health care providers for patients with dementia are hopeful and enthusiastic about the trials coming down the pipeline. The research is close; it just needs support to go the last mile.

Bruce L. Miller, MD is Professor of Neurology at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) where he holds the A.W. & Mary Margaret Clausen Distinguished Chair, teaches extensively and directs the busy UCSF dementia center. He is a behavioral neurologist focused in dementia with special interests in brain and behavior relationships as well as the genetic and molecular underpinnings of disease, and the author of Frontotemporal Dementia.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only brain sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Provided by the author. All rights reserved.

The post The impact of a dementia treatment appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat is “toxic” about anger?Psychiatry and the brainFrom RDC to RDoC: a history of the future?

Related StoriesWhat is “toxic” about anger?Psychiatry and the brainFrom RDC to RDoC: a history of the future?

Assembling a coherent picture in the Daniel Pelka case

The appalling murder of Daniel Pelka by his mother, Magdelena Luczak, and her partner, Mariusz Krezolek, has yet again been followed by soul-searching and a storm of criticism directed at ‘the authorities’ for their failure to protect Daniel from the child abuse that eventually led to his death. Of course, we must wait for the conclusions of the ‘serious case review’, which doubtless will yet again find failures of communication between agencies, and indecision, prevarication, and hesitation to take action on the part of at least some of their personnel. Nothing new there, then? Daniel has now taken his tragic place in a very long line of children abused and eventually killed by their parents or parent surrogates. This line stretches back to 1973 when the murder of Maria Colwell by her stepfather led to an inquiry amid popular indignation. The inquiry found — you guessed it — lack of communication between the agencies who were well aware of her vulnerability. Why does nothing change?

For an answer, perhaps the public should look at itself, for public opinion is nothing if not fickle. In the days and weeks before Daniel’s murder grabbed the headlines, there was another cause célèbre consuming acres of newsprint and hours of mass media programming. It was the revelation by Edward Snowden (the CIA ‘whistle-blower’) that GCHQ was scanning and retaining the meta-data of all and contents of some electronic communications that left our shores. To say that I wasn’t at all surprised by this is an understatement; I was flabbergasted that anyone was surprised.

What do these two scandals have in common? The answer is that they pose the ‘intelligence dilemma’ from either end of the telescope. The fate of Daniel Pelka prompts us to peer more sceptically beneath the surface appearance of family life, whereas Edward Snowden warns us against being too intrusive.

Intelligence is not merely the gathering of information, but more importantly its assemblage into a coherent picture. As the former head of the domestic intelligence service (MI5) Eliza Manningham–Buller put it in her BBC Reith Lectures, it is a question of ‘joining the dots’. Often it is the case with abused and murdered children that there was an abundance of dots, it is just that they were not joined together correctly. Time and again we find that different agencies knew snippets of information that were not shared and hence no picture emerged with sufficient clarity to take action.

What would the assembling of these dots require? It would require that agencies with very different purposes, structures, and values should share information with each other. Let us consider perhaps the most sensitive information: medical histories. Some of these children had been treated by medical staff, usually in Accident and Emergency. Should those medics share confidential information about those children with other state agencies, such as the police? If so, should the police be told everything, or only some things? If only some things, then what? Also, what should the police do with that information because many children pass through A&E on their way to maturity? For the injuries young children sustain to be reported to the police would amount to the collection of vast quantities of medical information about not only those at genuine risk, but also about those at little or no risk.

If we demand, in the wake of some horror, that ‘someone must have known what was happening and should have shared those concerns,’ then we are demanding that the state, through its various agencies, should know almost everything about all of us — a ‘Snowdenian’ nightmare. Such a nightmare is not a fanciful possibility. In another case of child murder — the Soham murders of Holly Wells and Jessica Chapman at the hands of Ian Huntley — the inevitable inquiry, chaired by Sir Michael Bichard, concluded that in order to mitigate risk the police and other agencies needed to pool what they knew about those who came to their attention in a huge database. In due course this recommendation blossomed into the Independent Safeguarding Authority, which decreed that all those working, in whatever capacity, with children and vulnerable adults must be thoroughly vetted. This created a furore. Leading authors who read stories to young children very publicly refused to be vetted and thereby faced exclusion from such activities. Volunteers who drove the occasional church outing in a mini-bus found that they too must be vetted. In 2012 the Independent Safeguarding Authority was dissolved and the demands for such stringent vetting ceased and state remained, if not blind, then myopic when it came to the risks being posed to children and vulnerable adults.

This exposes the irony of intelligence: it is best done in retrospect. It’s obvious, isn’t it, that a youth who has sexual relations with girls just under the age of consent and is falsely accused of rape is likely to murder, ten years later, two innocent young girls who he hardly knew? Surveys of teenage girls suggest that around half of them are or have been in sexual relationships, some of which are likely to be with lads a little over the age of consent. To prevent Huntley murdering Holly and Jessica on these grounds would probably disqualify thousands of men from becoming school caretakers, or come to that doing any of the jobs in which they come into contact with young girls. Retrospection is far easier than prediction and we have very little idea of what biographical indicators predict any form of criminality.

Suppose we did find that there were such tell-tale signs, would resolve the intelligence dilemma? No, it would not, for two reasons. First, such tell-tale signs would be accompanied by as much, if not more, error than contemporary weather forecasts. Negative errors would result in failing to distinguish the occasional individual who did not display such tell-tale signs and yet posed a danger to children. Positive errors would mean wrongly identifying some people as dangerous when they were not. Both would provoke public scandal and we would be little better off.

The second reason why the discovery of tell-tale signs would not resolve the intelligence dilemma brings us back to Mr Snowden and GCHQ. In order to identify those who exhibit the tell-tale signs it is necessary to scan everyone at some level. The reason that Amazon knows what DVDs I like better than I do, is not only because thousands of people make millions of purchases, from which Amazon’s data–miners are able to extract enduring preferences. It is also because, armed with that information, they are able to distinguish my online purchasing habits from those of my wife. Unless the veil of privacy is raised at least a little on everyone, then we can never have sufficient information to ‘join the dots’ with any accuracy.

Perhaps we need to recognise reluctantly that there are many things in life that cannot be predicted and that we would not want to be predicted. All we can do is to express our outrage at those who perpetrate such horrors.

P.A.J. Waddington is Professor of Social Policy, Hon. Director, Central Institute for the Study of Public Protection, The University of Wolverhampton. He is a general editor for Policing. Read his previous blog posts.

A leading policy and practice publication aimed at senior police officers, policy makers, and academics, Policing contains in-depth comment and critical analysis on a wide range of topics including current ACPO policy, police reform, political and legal developments, training and education, specialist operations, accountability, and human rights.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Social network background. © bekir gürgen via iStockphoto.

The post Assembling a coherent picture in the Daniel Pelka case appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHuman rights education and human rights law: two worlds?Is yoga religious? Understanding the Encitas Public School Yoga Trial‘Yesterday I lost a country’

Related StoriesHuman rights education and human rights law: two worlds?Is yoga religious? Understanding the Encitas Public School Yoga Trial‘Yesterday I lost a country’

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers