Oxford University Press's Blog, page 911

August 21, 2013

Looking “askance”

I have been meaning to tell the story of askance for quite some time—as a parable or an exemplum. Popular books and blogs prefer to deal with so-called interesting words. Dude, snob, and haberdasher always arouse a measure of enthusiasm, along with the whole nine yards, dated and recent slang, and the outwardly undecipherable family names. Smut is equally attractive, but there is a limited amount of it, and its novelty and allure wear off with age. This blog is no exception, though occasionally I risk talking about north, winter, rain, and other “colorless” words. People outside the profession seldom realize how much labor has to be expended before one can write a line or two about etymology in a “thick” dictionary. Even the off-putting verdict “origin unknown (uncertain)” usually means that numerous efforts to reconstruct a word’s past have been unsuccessful rather than that no one has tried to solve the riddle. Kibosh, featured last week, serves as a good illustration of such a case: many men, many minds, and no final solution in view.

The adverb askance (now used only or almost only in look askance) has been known since the fifteen-thirties. No one is sure how it came into being. The prefix a- may be from French, but it may be a reduced form of Engl. on, as in abed and asleep. A century and a half before the emergence of this askance (let us call it askance2) another askance (askance1), a conjunction meaning “as if, as though,” surfaced in English. Language historians have been unable to agree on their possible interaction: Are we dealing with two senses of the same word (despite the chronological gap) or two homonyms having nothing to do with each other?

Students of sound change can be guided by so-called laws (to use a less pompous term, rules or correspondences) and when, for instance, they observe that milk is called moloko in Russian (stress on the last syllable), they are puzzled, rather than elated, because if those words (one from a Germanic language, the other from Slavic) were cognate, they would not have had the same last consonant (k; however, m- and m- are fine). By contrast, in semantics bridges are easy to draw and even easier to demolish. Is there a way from “as if, as though” to “sideways”? Perhaps there is. Someone who dissimulates or is moved by disdain, envy, or distrust tends to avoid looking his interlocutor squarely in the face—thus, from “as if” to “obliquely.” I find this reasoning convincing (the formulation belongs to the noted etymologist Leo Spitzer); others don’t. Both the conjunction and the adverb have always been low frequency words, so that they could not be expected to occur in texts often enough to provide us with sufficient information about the time of their coining..

A classic question of etymology is: “Native or borrowed?” No one doubts that askance, whether it be askance1 or askance2 (and modern speakers are interested only in askance2) does not go back to Old English. The debating point is whether the lending language belongs to the Romance or the Germanic group. Both contain numerous words that may theoretically have produced askance. To begin with Romance, such are Italian schiancio “oblique, sloping” and aschiancio “across, athwart”. Close by are Italian scansare “avoid” and a scansa (di) “obliquely.” Old French seems to have had escant “out of the corner, out of the square” (only eschantel seems to have been recorded) and certainly had escons(e) “hidden.” Even if some of the Italian and French words are related, English borrowed askance only from one language, so that the question about the source remains.

Looking sideways

The etymology of askance “as if” is secure: it leads us to Latin quamsi (the same meaning). If askance1 and askance2 are not related, this fact has no weight in the present discussion. However, if they are, quamsi should be thrown into the hopper and stay there. The main early work pertaining to the French origin of askance was done by Frank Chance, an excellent etymologist, now almost forgotten. He believed that askance1 and askance2, though both of French descent, were different words. Skeat followed Frank but forgot to refer to his predecessor, and Notes and Queries, the periodical in which Chance published nearly everything he wrote (that is why hardly anyone remembers him today), has preserved Chance’s indignant letter and Skeat’s lame apology. As time went on, Skeat felt less and less certain about the origin of askance. The same holds for Chance. The progress of etymology consists as much in discovering words’ true origins as in discarding wrong and dubious conjectures. One of its bitter triumphs is the ability to say “origin unknown.”

The pun on Frank Chance’s name is unintentional, but the etymon of askance may be the word chance, not necessarily French chance but a Germanic reflex of Medieval Latin cadentia “fall” (noun) via Dutch or Scandinavian. Such was Frank Chance’s later opinion. Yet the Germanic ways might have been more devious. Askance has often been compared with Dutch schuin “oblique” and Engl. squint. Then there is Old Icelandic á ská “across, askew,” along with á skant and Danish åskands—a veritable embarrassment of riches.

My proposal is as questionable as anybody else’s. However, I believe that no etymology of askance will carry conviction unless both askance1 and askance2 have been explained. Very few researchers were ready to traverse so much ground and since askance “as if” is obsolete (one can say “dead”), even the most comprehensive dictionaries of Modern English enjoy the luxury of dealing with the adverb and ignoring the conjunction. Since I find the reconstruction of the semantic path from “as if, as though” to “sideways, obliquely” plausible and since the conjunction (“as if”) is certainly of Romance origin (Latin quamsi), I conclude that the adverb (“sideways”) ultimately goes back to the same word and reject the Germanic etymons mentioned above. The development from “as if” to “sideways” must have taken place in English.

Will my colleagues who think differently agree with me? They undoubtedly won’t. Consensus among historians is rare. The same holds for language historians. Etymologies are not theorems (they do not depend on a set of axioms or postulates) and cannot be proved. I think that I have cast my net more broadly than some of my “rivals,” but in tracing the past and in evaluating this process very much is a matter of opinion. Despite the inevitable uncertainty, formulating hypotheses, especially such as are based on all the facts known at the moment, is not a waste of time. Each honest attempt to discover the truth is a step in the right direction. A colleague of mine who believes that all etymology is a fairy tale and who therefore pities my activity has no need to feel superior (I tried to bring it home to her many times but without success). Etymologists have ploughed a good deal of fertile soil, not only tons of sand. No one is justified in looking at them askance.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: The Cardsharps by Caravaggio, circa 1594. Kimbell Art Museum. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Looking “askance” appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThree recent theories of “kibosh”Alphabet soup, part 2: H and YMonthly etymological gleanings for July 2013

Related StoriesThree recent theories of “kibosh”Alphabet soup, part 2: H and YMonthly etymological gleanings for July 2013

A quiz on the history of sandwiches

August in National Panini month, honoring the lightly grilled, trendy sandwich that Americans have come to love over that past few decades. Instead of just focusing on just one sandwich though, we would like to present the entirety of the sandwich universe. Therefore, we’ve come up with up with a short quiz about them. What exactly is a Muffaletta Sandwich anyway?

What’s there to know about sandwiches? Well, let’s start with the fact that today in the 21st century they’re being consumed in some form in almost every country in the world. Not to mention, by 1986 it was estimated that the average high school student consumed a whopping 1500 peanut butter and jelly sandwiches before they even walked across the stage for graduation. Why don’t you dive into the quiz and find out what you really know?

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Andrew F. Smith teaches culinary history and professional food writing at The New School University in Manhattan. He is the Editor-in-chief of The Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America, Second Edition. He serves as a consultant to several food television productions (airing on the History Channel and the Food Network), and is the General Editor for the University of Illinois Press’ Food Series. He has written several books on food, including The Tomato in America, Pure Ketchup, and Popped Culture: A Social History of Popcorn in America.

The Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America (2 ed.) is included in Oxford Reference, home of Oxford’s quality reference publishing, bringing together over 2 million entries, many of which are illustrated, into a single cross-searchable resource. With a fresh and modern look and feel, and specifically designed to meet the needs and expectations of reference users, Oxford Reference provides quality, up-to-date reference content at the click of a button.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only food and drink articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Girl eating a sandwich at Camp Goodwill 1905. Chicago Daily News, Inc., photographer. Chicago Daily News negatives collection, Chicago History Museum. Public domain via Library of Congress.

The post A quiz on the history of sandwiches appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAn ice cream quizWhat are you drinking?Happy birthday, Scofield!

Related StoriesAn ice cream quizWhat are you drinking?Happy birthday, Scofield!

Five important facts about the Russian economy

Churchill once famously said that Russia was “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.” While this definition was based mainly on Russia’s behavior in international politics in the late 1930s, it could also apply it to Russia’s economy today. Russia is a space power that doesn’t seem to be able to produce a decent passenger car; it is a market economy with pervasive state influence, both formal and informal, in almost all areas of economic activities; it is a country with first-rate scholars and it is also rather backward in many respects. Can this riddle be solved? Many books and scholarly papers have been trying to provide an answer. What are some of the main takeaways from an analysis of this mystery?

Moscow, Russia. Photo by Henry de Saussure Copeland, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

(1) The Soviet legacy is alive.

Twenty years after the demise of the Soviet system it continues to impede Russia’s development but also provides some temporary benefits to the economy and society. The Soviet legacy can be classified into three types: physical (the old physical and human capital, and its allocation among sectors and regions), institutional (formal and informal rules, including those related to private property rights and contracting), and behavioral (the mindset of the people, including the leadership). These legacies interact and perpetuate themselves. For example, there is still a large inventory of geographically misallocated and technologically obsolete physical capital in cold areas of the country and the current system makes it worthwhile in the short run to continue exploiting the old assets and investing in their maintenance rather than scrapping them and taking advantage of new technologies in more hospitable areas. Perhaps the hardest part of the Soviet legacy to overcome is the people’s mindset that discourages initiative and risk-taking, at least in the official sector of the economy. Nonetheless, some progress has been made and there is hope that Russia will eventually rid itself of the worst features of Soviet heritage and join the club of advanced market economies.

(2) Most of the new institutions are not working too well.

Over the last 20 years, many market economy institutions have emerged. Contract law has been developed; private property rights defined; the tax system looks similar to those in developed West European countries. However, these institutions often do not function properly, mainly because of the lack of judiciary independence from the state and pervasive corruption. Russia is in the bottom 15% of the countries in terms of corruption control according to World Bank rankings. More generally, Russia lags behind most other economies in transition and even many poor countries in terms of institutional quality. The only thriving institutions are those used for natural resource rent extraction (e.g. financial infrastructure and security services).

(3) Oil and gas are still the mainstay of the economy that appears to be addicted to natural resource rents.

It is common knowledge that oil and gas represent the dominant sector of Russia’s economy. What might be less known is that the dependence on this sector has grown significantly since the turn of the century despite the apparent diversification efforts by the government. As a result, while the federal budget was in surplus at oil prices of $69/barrel just six years ago, it now requires $117/barrel prices to avoid deficits. The reliance on oil and gas rents weakens the incentives for restructuring the economy, subsidizes and perpetuates inefficient manufacturing and other sectors, and supports a bloated state bureaucracy and the military. In addition, the reliance on oil and gas exposes the economy to significant volatility due to notoriously unstable prices of these commodities.

(4) Geography and demography present major long-term challenges.

Most of the above challenges could be overcome by government policies if there is sufficient skill to diagnose the problems and determination to fix them. The problems posed by geography and demographic trends are more difficult or at least more expensive to solve. Russia is by far the largest country in the world. Moreover, much of Russia’s natural resources and a significant share of the population are located in remote areas with inhospitable climate (Soviet legacy again). Despite early expectations, there has been little migration from those areas to warmer parts of the country. Its geographical challenges are exacerbated by relatively small and rapidly ageing population that declined every year between 1993 and 2009 due to high mortality rates and low fertility. In the end, these demographic and geographic factors may prove decisive in determining the future of Russia and its economy.

(5) The economy has grown greatly since 1999.

Despite all of the challenges, Russia’s GDP per capita has approximately doubled since 1999. However, what was one of the fastest world rates of economic growth prior to the crisis of 2009 has slowed down to below 2% in the first quarter of 2013 and zero growth in June, according to preliminary data. The slowdown is partly caused by stable oil prices and thus may be temporary, but all of the challenges described above require bold policies to put Russia’s economy on a sustainable growth path less dependent on the vagaries of the world commodity prices.

Michael V. Alexeev is a Professor of Economics at Indiana University in Bloomington. His research interests include economics of institutions, public economics and economics of transition. He is the co-editor of The Oxford Handbook of the Russian Economy with Shlomo Weber.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Five important facts about the Russian economy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesJust who are humanitarian workers?Gender politics and the United Nations Security CouncilThe black quest for justice and innocence

Related StoriesJust who are humanitarian workers?Gender politics and the United Nations Security CouncilThe black quest for justice and innocence

A Who’s Who of the Edinburgh Festival

It’s that time of year again; Edinburgh is ablaze with art, theatre, and music from around the world. For the month of August, Edinburgh is the culture capital of the world, as thousands of musicians, street-performers, actors, comedians, authors, and artists demonstrate their art at various venues across the city. Some of the most famous names to have performed at the festival since its inception in 1947 are listed in Who’s Who and Who Was Who. Edinburgh Festival is a collective term for an array of arts and music festivals that take part in the city during August. The original and largest component festivals are the Edinburgh International Festival and the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. So please take your seats at the front, sit back, and take a cultural tour of the Festival and its stars.

Jonathan Edward Harland Mills has been the Director of the Edinburgh International Festival since 2007. Jonathan’s video introduction to the 2013 Edinburgh Festival shows that one of the primary themes of this year’s festival is how artists take seemingly simple concepts and use them to transform our perceptions of the world around us. He highlights Andreas Haefliger and the Scottish Ballet, amongst other, as events that should not be missed. Unlike the Edinburgh Fringe, performers at the Edinburgh International Festival must be invited to perform by the Director himself. The Edinburgh International Festival hosts the world’s best classical musicians and focuses on delivering the very best in opera, dance, and solo performances each year. This tradition dates back to the creation of the festival in 1947, as its list of founders includes Sir Rudolf Bing, who was at the time the General Manager of Glyndebourne Opera Festival.

Regular performers at the Edinburgh International Festival include Yo-Yo Ma, world renowned cellist, and André Previn, the German-American conductor, pianist and composer. As one of the most famous cellists of the modern-age, Yo-Yo Ma has received multiple Grammy Awards, as well as the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2011. André Previn has won four Academy Awards for his work in film scores, eleven Grammy Awards for his recordings, and has been a Guest Conductor at Edinburgh several times. The music doesn’t stop there though, oh no. Who’s Who includes the most famous musicians to have performed at the Edinburgh International Festival throughout the 20th century. From Maria Callas to Sir Michael Tippett, from Jacqueline Du Pré to Mstislav Rostropovich, and from Sir Malcolm Sargent to Humphrey Lyttelton, Edinburgh International Festival has played host to an incredibly diverse selection of the highest class musicians since 1947. Rostropovich’s 1960 Edinburgh performance was particularly memorable as it was the first performance in the UK of Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. 1, a concerto written and dedicated to Rostropovich in 1959.

It is not just the footsteps of past musicians that you can retrace in Edinburgh though. Actors and directors such as Sir John Gielgud, Richard Burton, Dame Edith Ashcroft, and Ingmar Bergman have all appeared at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. Richard Burton played Hamlet in a critically acclaimed Old Vic production that later made the journey down to London, setting the trend for successful Edinburgh shows in the future. The Edinburgh Fringe Festival has become the largest arts festival in the world and continues to grow each year. More and more shows premiere at the Edinburgh Fringe, only to go on runs in London and New York after. The 2012 Edinburgh Fringe Festival spanned 25 days, and totalled over 2,695 shows from 47 countries in 279 venues. Out of these shows, 1,418 shows were having their world premiere.

It is for this reason that so many performers use Edinburgh as a kind of “Litmus Test” to gauge the appeal of their show – or to make their name in such a competitive industry. For instance, Rowan Atkinson impressed so much in the Oxford University Revue sketch show in 1976 that within a few years, he was the youngest ever stand-up comedian to have a one-man show in London’s West End. At a similar time, the Edinburgh Fringe Festival also launched the careers of Stephen Fry, Hugh Laurie, and Emma Thompson through the Cambridge University Footlights Group in 1981. Other performers in recent years that have cut their teeth at the Edinburgh Fringe include; Tim Minchin, Ronni Ancona, Steven Berkoff, Dame Judi Dench, Alan Rickman, and Miranda Richardson.

However, it is not always the case that positive reviews at the Edinburgh Fringe translate to positive reviews in London or New York — or even that negative reviews in Edinburgh culminate in the death of a show. Indeed, Alan Bennett, co-author and actor in Beyond the Fringe, was disappointed by a tepid response to his sketch-show at Edinburgh. Yet, after the play transferred to the Fortune Theatre, London, Beyond the Fringe became a huge success story and is often credited as seminal in the rise of satire in London’s West End.

So that’s it. The curtain is coming down on this Edinburgh Festival tour. But if you enjoy a good encore (and who doesn’t?) then discover even more performers who made their name at the Edinburgh Festival in Who’s Who Online.

Daniel Parker is publicity assistant for Who’s Who and numerous other OUP online products.

Who’s Who is the essential directory of the noteworthy and influential in every area of public life, published worldwide, and written by the entrants themselves. Who’s Who 2013 includes autobiographical information on over 34,000 influential people from all walks of life. You can browse by people, education, and even recreation. The 165th edition includes a foreword by Arianna Huffington on ways technology is rapidly transforming the media. Please note that the Who’s Who articles in this blog post will be freely accessible until the 20th June 2013, after which you can access through a subscription. You can follow Who’s Who on Twitter @ukwhoswho.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only arts and leisure articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credits: (1) Elvis Character at the Edinburgh Fringe via iStockphoto. (2) Rowan Atkinson via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A Who’s Who of the Edinburgh Festival appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEdinburgh International Book Festival: Frank Close and Peter HiggsWho were the Carlisle Commissioners? Part two: Jeremy BenthamThe 1812 Overture: an attempted narration

Related StoriesEdinburgh International Book Festival: Frank Close and Peter HiggsWho were the Carlisle Commissioners? Part two: Jeremy BenthamThe 1812 Overture: an attempted narration

August 20, 2013

100th anniversary of the first crystal structure determinations

This year celebrates the hundredth anniversary of the first crystal structure determinations. On 30 July 1913, the crystal structure of diamond was published by W. H. and W. L. Bragg, father and son, and those of sodium chloride, potassium chloride, and potassium bromide, by W. L. Bragg, the son. They were the first crystal structures determined by X-ray diffraction, and they revolutionized the ideas of the time about chemical bonds in solids.

The determination of crystal structures was made possible by M. von Laue, W. Friedrich, and P. Knipping’s discovery of the diffraction of X-rays by crystals in April 1912, just over a year before, in Munich, Germany. That discovery, which came 17 years after the discovery of X-rays by W. C. Röntgen, really changed the world. It had far-reaching consequences, by making possible the studies of the structure of the atom and of the structure of matter.

Laue, Friedrich, and Knipping had put crystals of copper sulphate and zinc-blende (ZnS) in the beam emitted by an X-ray tube, and had observed discrete diffraction spots. This simple observation showed the wave character of X-rays and confirmed the space-lattice hypothesis of the arrangement of atoms in crystals. M. von Laue was awarded the 1914 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery.

The news reached the Braggs in July 1912 at their holiday site on the Yorkshire coast. William Henry Bragg, the father, then 50 years old, was Professor of Physics at the University of Leeds and had recently come back from Australia, where he had been Professor of Physics for 23 years. William Lawrence Bragg, the son, was just 22 years old, and a student at Trinity College, Cambridge. Laue’s experiment puzzled them a great deal, until the young Willie, remembering the lectures of his optics Professor, C. T. R. Wilson, proposed quite a different interpretation of the Munich experiment than Laue had done. He suggested that the observed diffraction spots were due to the diffraction of X-ray waves on the various families of lattice planes which build up crystals.

W. L Bragg calculated the positions of the diffraction spots on the Laue diagram, using the well known equation, now called Bragg’s law, and showed that zinc-blende, ZnS has in fact a face-centred cubic lattice, and not a simple cubic lattice, as had been assumed by Laue. It was this feat that opened up the possibility of determining crystal structures. Bragg’s results were presented at the Cambridge Philosophical Society by the Director of the Cavendish Laboratory, Professor J. J. Thomson, on 11 November 1912. They were a remarkable accomplishment for a 22-years-old man, still a mere student.

The successful interpretation of Laue’s diagram was not the end of the story for W. L. Bragg. He started making experiments of his own, and, during the spring of 1913, recorded in Cambridge Laue diagrams of crystals of alkali halides, zinc-blende, and fluorite, CaF2, while his father, in Leeds, designed the first X-ray spectrometer, using an ionization chamber.

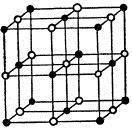

Figure 1. Structure of sodium chloride. After W. L. Bragg (1913). The Structure of Some Crystals as indicated by their Diffraction of X-rays. Proc. Roy. Soc. 89, 248-277.

With it, father and son recorded in April 1913 the first X-ray spectra, constituted by lines due to the diffraction of the characteristic lines of the anticathode of the X-ray tube by a crystal sodium chloride. It is both from the Laue diagrams taken in Cambridge and from data recorded in Leeds with his father’s spectrometer that W. L. Bragg determined the structure of sodium chloride (Figure 1, right).Together, father and son determined the structure of diamond, also using both Laue diagrams and spectra recorded with the ionization chamber. They showed that the carbon atoms are located at the centres of tetrahedra, the summits of which are also occupied by atoms of carbon. The resulting structure is shown in Figure 2, below.

Figure 2: Model of the structure of diamond by W. H. Bragg. Museum of the Royal Institution, London. Photo by the author.

The structure of alkali halides was not so easily accepted by chemists. There are no individual molecules, neither in diamond nor in sodium chloride: every carbon atom is linked to four carbon atoms in diamond; in sodium chloride, each chlorine is surrounded by six sodium and each sodium by six chlorine, and this throughout the volume of the crystal. The crystal is therefore in itself a single molecule. This went strongly against the molecular theory of the chemists. The German chemist P. Pfeiffer noted in 1915 that ‘the ordinary notion of valency didn’t seem to apply’, and fourteen years later, the influential chemist H. E. Armstong still found Bragg’s proposed structure of sodium chloride ‘more than repugnant to the common sense, not chemical cricket’!

X-ray diffraction produced a microscope with atomic resolution that does not show the atoms themselves, but their electron distribution. It has opened the way for entirely new developments in solid-state chemistry, solid-state physics, mineralogy, geosciences, materials science, and biocrystallography. Thanks to X-ray diffraction, the structure of the semiconductors used in the microelectronic devices was discovered, a classification of the silicates abundant in the earth’s crust could be established, and were determined the structure of DNA and of the big proteins responsible for the cycle of life. It is now used routinely in the development of new drugs.

W.H. and W.L. Bragg were awarded the 1915 Nobel Prize in Physics, for their services in the analysis of crystal structure by means of X-rays. More than 20 Nobel Prizes were awarded for work using X-ray or electron diffraction, the latest being the 2012 Nobel Prize for Chemistry awarded to R. Lefkowitz and H. Hughes for studies related to the crystal structure determination of ‘G-protein-coupled receptors’.

André Authier is Professor Emeritus at the Université P. et M. Curie, Paris, and a member of the German Acazdemy of Sciences, Leopoldina. He is a former President of the Internaational Union of Crysrallography (1990-1993). His book, Early Days of X-ray Crystallography, is published by Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post 100th anniversary of the first crystal structure determinations appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWho were the Carlisle Commissioners? Part two: Jeremy BenthamThe 1812 Overture: an attempted narrationHappy birthday, Scofield!

Related StoriesWho were the Carlisle Commissioners? Part two: Jeremy BenthamThe 1812 Overture: an attempted narrationHappy birthday, Scofield!

Who were the Carlisle Commissioners? Part two: Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) was something of an enigma. At the age of three, he started studying Latin and, allegedly, finished reading a multi-volume history of England by the age of four. He is known as the founder of Utilitarianism, a leading theorist in the Anglo-American philosophy of law, and the spiritual founder of University College London. He also advocated freedom of expression, equal rights for women, the right to divorce, abolition of slavery, the abolition of the death penalty, the abolition of physical punishment, including that of children, and the decriminalising of homosexual acts almost two centuries before it became fashionable to do any of these things.

However, Electronic Enlightenment have uncovered previously lost correspondence written by Jeremy Bentham that illustrates that he also wanted to become a Carlisle Peace Commissioner but his application was wilfully ignored by Governor Johnstone. As aforementioned in yesterday’s blog post, the Carlisle Peace Commissioners set out to the United States in 1778, three years into the American Revolutionary War, to negotiate a peace treaty. Jeremy Bentham himself (self-promoting legal expert that he was), highly expected that he would be one of the Carlisle Peace Commissioners.

Writing to a correspondent in Russia, the Reverend John Forster (1697–1781), Bentham outlines his proposal to become a Carlisle Commissioner by speaking to Governor Johnstone about why he merited a place on the voyage:

I thought myself within an ace t’other day of being of his party to America. Governor Johnstone, who is another of the Commissioners, I had heard was very fond of the Fragment, and used to carry it about with him in his pocket. A few days before they set out I happened to hear of his having written to Professor Ferguson of Edinburgh, author of the Essay on Civil Society, to ask him to go with him on that expedition, not I believe in the official capacity of a Secretary, but as a friend, for the sake of company and advice. Storer, who is in Parliament I heard at the same time was to go on the same footing with Lord Carlisle. The warning was so short, that it appeared probable that Ferguson might not have time enough before him to enable him to accept the offer. It occurred to me in the instant that if he should not, it might not be impossible that the Governor as he seemed to have taken such a liking to my writings (indeed I should have told you he had asked a friend of mine to make him acquainted with me) might be willing to take me. The company I thought would be agreable, the sea voyage would be of service to my health, and the object of the expedition might give me a little practise in public business. I therefore went immediately to a friend of mine who is intimate with Johnstone, to whom he proposed it without loss of time.

Jeremy Bentham

The initial response from the Governor massaged Bentham’s considerable ego but, crucially, did not commit to accepting Bentham on the voyage, as he goes on to explain:

Johnstone’s answer was so flattering to me, (though I have never heard him spoken of as a man of compliments) that were it not for what follow’d, it would hardly be decent for me to mention it. He said if he could but get me, he should think he had got a treasure: thanked my friend for mentioning it, but chid him for not mentioning it before: regretted he had sent for Ferguson, and that it was too late to countermand him: but said that he was to have two gentlemen with him, the other a Barrister of our Inn who had been recommended to him by his Brother Pulteney (Pulteney you know was originally a Johnstone, and took his name for the Bath estate) that he would take me in either of two events: If Ferguson did not come at the time expected, or if Mr. Pulteney could be prevailed on to let him off with respect to the other gentleman: observed that he (Johnstone) was under great obligations to his brother, that he was dependent on him, and therefore that if he should peremptorily refuse to let him off there was no remedy. For he was so circumstanced that it was necessary for him not to quarrel with his brother. “rompre en visière” was the expression: for being so remarkable an one, I put it again and again to my friend to tell me whether it was really the one he used. He concluded with saying that he would go and talk with his brother that instant, and would immediately acquaint my friend with the result.

As the letter then goes on to show, Bentham waited and waited to hear back from Governor Johnstone, expecting that he would at the very least hear back from the Governor who had said: “if he could but get me, he should think he had got a treasure”. But no response ever arrived:

This was on the Friday: the Commissioners set off for Portsmouth the Tuesday after. Would not you have imagined that some sort of apology or at least some answer would have been made to me? Not a syllable have my friend or I heard from Johnstone to this hour. My friend was highly exasperated, while as yet there was nothing to complain of but delay; He wrote him a note in pretty peremptory language which was sent, but, as it proved, too late to reach him. To love mankind, says Helvetius, one should expect but little of them. I do expect but little of them, and am therefore seldom disappointed, and never vehemently.

Sadly, rejection became a recurring motif in Bentham’s life; he also spent sixteen years developing and designing ideas for a new British national penitentiary building only for his plans to be ignored by the British government. The Panopticon penitentiary design has since had a significant impact on 20th century philosophers, particularly Michel Foucault. Sadly, Bentham died before he could see the impact he had on modern philosophy — just like he never set sail to meet with the US Congress as a Carlisle Peace Commissioner.

Daniel Parker is Publicity Assistant for Electronic Enlightenment and numerous other online products at OUP.

Electronic Enlightenment is a scholarly research project of the Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, and is available exclusively from Oxford University Press. It is the most wide-ranging online collection of edited correspondence of the early modern period, linking people across Europe, the Americas, and Asia from the early 17th to the mid-19th century — reconstructing one of the world’s great historical “conversations”.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Jeremy Bentham by Henry William Pickersgill via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Who were the Carlisle Commissioners? Part two: Jeremy Bentham appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWho were the Carlisle Commissioners? Part oneCelebrating Coco Chanel (1883-1971)The 1812 Overture: an attempted narration

Related StoriesWho were the Carlisle Commissioners? Part oneCelebrating Coco Chanel (1883-1971)The 1812 Overture: an attempted narration

The 1812 Overture: an attempted narration

I was a sophomore in college, sitting in my morning music history course on the Romantic period, and my professor was discussing the concept of program music, which Grove Music Online defines as “Music of a narrative or descriptive kind; the term is often extended to all music that attempts to represent extra-musical concepts without resort to sung words.”

The musical example my professor chose to illustrate the idea was Tchaikovsky’s 1812 overture, which is celebrating the 131st anniversary of its premiere at the Moscow Arts and Industry Exhibition in 1882. The original title of the piece, which is a festival overture, is simply 1812, “The 1812 Overture,” being its accepted nickname.

It turned out that this piece of music I’d been enjoying every 4th of July for the past 18 years was trying to tell me a very specific story. That story was not, of course, the story of the War of 1812, though its title might be misinterpreted that way by American audiences. Despite its traditional performance by US orchestras on Independence Day, the work is unrelated to any British-American conflict. Tchaikovsky wrote the overture to celebrate Russia’s defeat of Napoleon’s army in 1812.

My professor went on to play a recording of 1812 and eloquently narrated the entire thing, never pausing, like a foreign-language interpreter. The level of detail in what the music intended to tell us was impressive; the piece was not about nationalism or war in general, but described in detail this specific conflict’s individual participants, their actions, and the conclusion of the fighting.

I went to my friend’s house the night after the lecture and told him all about it. We found a recording of the overture and I claimed I could narrate it just like my professor had done for the class. And I was doing well, for about two minutes—after that there were long stretches of the piece during which I had no idea what Tchaikovsky was trying to describe. I could fake my way through it for ten-second stretches, maybe, but each was followed by awkward pauses in my storytelling, and my poor friend had to sit for 15 minutes of me vamping between reprises of musical motifs I knew how to explain.

For today, I’ve prepared a little better. I hope you’ll join me in celebrating the anniversary of the 1812’s premiere (and in apologizing to my friend) by listening to this recording and reading along with my second attempt at narrating the piece. Be forewarned that there are still some moments in the overture whose meanings elude me.

I’ve indicated the time markings for each section below, so please listen along with the same recording I used. (I picked this recording because it warns you that it uses real cannons—be sure not to listen to this with headphones on, as I did when I was preparing, or to at least keep the volume turned down. They’ll be louder than you think. Ow.)

Click here to view the embedded video.

(1) [0:00–1:30 or so]: An arrangement of the Russian hymn “Spasi, Gospodi, Iyudi Tvoya” (“O Lord, Save Thy People”) is played by soloists in the viola and cello sections, with other orchestra members entering in gradually. We, the listeners, are in Russia, our minds trained on the country’s inhabitants.

(2) [2:12– 3:45]: The suspenseful, storm’s-a-comin’ sort of music (notice any narrative water-treading already? Yeah, me too.) emerges out of the peaceful hymn, and we know that trouble is approaching Russia.

(3) [3:48– 4:45]: French soldiers are on their way! Snare drums, long a musical indicator of the military, are heard in this first appearance of what is probably the overture’s best-known theme:

Or to put it phonetically: bada-bumbum-BUMbumbumbum-BUM-bum-bummmmm….

(4) [4:46– 6:36]: Frantic, escalating passages culminate in brief snippets of La Marseillaise, the French national anthem, underscored by tense ostinatos in the strings. The French are on the attack. This music then morphs into…

(5)6:36–8:10]: …the attractive Russian countryside? Hoo boy, I’m not sure. I think of this pastoral section sort of like those side chapters in long novels where the authors take a break from the main plot to discuss an attractive landscape in great detail. Pretty, but lacking in action. Perhaps it’s just here to give us a respite from the battle scenes. Eventually transitioning into a minor key, it segues gradually into the next section.

(6) [8:10–8:54]: The traditional, dance-like Russian folk-tune “U vorot” (“At the gate”) enters the work. Perhaps Tchaikovsky’s borrowing of several different Russian tunes while providing only one musical stand-in for France says something important about the way the piece characterizes the two warring countries: one is more complex, with a great depth of culture and slant toward the serene, while the other is a single-minded aggressor.

(7) [8:54–10:25]: Suspense builds again—the battle is back on—as a variation of the earlier frantic music and the accompanying hints of the Marseillaise return in a modified form.

(8) [10:25–11:10]: The peaceful-countryside music returns again, first in a major key, then in minor.

(9) [11:10–11:31]: “U vorot” is reprised, completing the cycle of repeated sections. Note that the first time through this cycle (sections 4 through 6) took approximately four minutes and nine seconds to complete, while this second time (7 through 9) only took two minutes and 37 seconds. The plot is moving more quickly now; we’re approaching the denouement.

(10) [11:31–]: The Marseillaise snippets appear alone in the horns, accompanied by more frantic playing from the strings and a rumble in the timpani that grows, and grows, and grows, until…

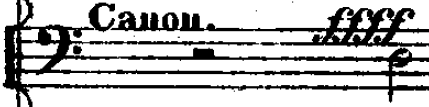

(11) [12:04–12:11]: THE CANNON. Boom, boom, boom, boom, boom. The five blasts ring out as the powerful Russian army fights back against their enemies. This, by the way, is how a cannon blast was notated in the score I looked at:

Notice the dynamic marking, ffff, or fortissississimo. This is actually from cannon blasts later on in the piece, at section 14—those in section 11 are only marked fortissimo. Apparently specific levels of loudness can be indicated for cannon fire (even if it was just for consistency within the score)—they have a bigger dynamic range than I thought. Remember to play out, you guys!

(12) [12:56–13:59]: Bells begin ringing out. To reference Grove Music Online once more, apparently Tchaikovsky originally wanted to use “all the churchbells in Moscow,” but “had to be content with the massive bells at Uspensky Cathedral where it was first performed.” I guess sometimes we just have to make do with what we’ve got.

(13) [14:01–14:08]: Goodbye, French! Their bada-bumbum-BUMbumbumbum-BUM-bum-bummmmm theme is played quickly as they retreat.

(14) 14:09–15:09: “Bozhe, Tsarya khrani!” (“God save the Tsar!”, the Russian Empire’s national anthem during Tchaikovsky’s lifetime) overtakes the French theme, and is underscored (or overscored, depending on your speaker system) by ten more cannon blasts, the last of which, at 14:31, overlaps with a return of the bells, confirming the Russian victory.

Jessica Barbour is the Associate Editor for Grove Music/Oxford Music Online. You can read her previous blog posts, “Baseball scoring,” “Glissandos and Glissandon’ts,” and “Wedding Music” and learn more about Tchaikovsky, program music, and musical nationalism with a subscription to Grove Music Online.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Snippets from the score courtesy of IMSLP.

The post The 1812 Overture: an attempted narration appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSophie Elisabeth, not an anachronismAnthems of AfricaCelebrating Coco Chanel (1883-1971)

Related StoriesSophie Elisabeth, not an anachronismAnthems of AfricaCelebrating Coco Chanel (1883-1971)

August 19, 2013

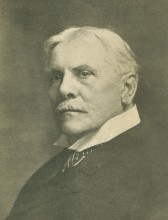

Happy birthday, Scofield!

Best known for its cross referencing system, helpful commentary in the margins, and highlighting quotations from Jesus in red, the Scofield Study Bible provides many resources for modern readers of various backgrounds. The Scofield Reference Bible, as it is also known, is used by millions of readers around the world from numerous denominations of Christianity and academic fields. Where did this version of the Bible come from? Now with nearly a hundred years of prestige and popularity behind it, we can look back and learn about the creator of this format, American Cyrus I. Scofield. For the anniversary of his birthday, test out your knowledge about the man behind the Bible with this quiz!

Best known for its cross referencing system, helpful commentary in the margins, and highlighting quotations from Jesus in red, the Scofield Study Bible provides many resources for modern readers of various backgrounds. The Scofield Reference Bible, as it is also known, is used by millions of readers around the world from numerous denominations of Christianity and academic fields. Where did this version of the Bible come from? Now with nearly a hundred years of prestige and popularity behind it, we can look back and learn about the creator of this format, American Cyrus I. Scofield. For the anniversary of his birthday, test out your knowledge about the man behind the Bible with this quiz!

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Kate Pais joined Oxford University Press in April 2013. She works as a marketing assistant for the history, religion and theology, and bibles lists.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Photograph of Cyrus Ingerson Scofield, Bible teacher and creator of the Scofield Reference Bible, c. 1920. Author unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Happy birthday, Scofield! appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesReparations and regret: a look at Japanese internmentAn ice cream quizWhy should we care about the Septuagint?

Related StoriesReparations and regret: a look at Japanese internmentAn ice cream quizWhy should we care about the Septuagint?

Celebrating Coco Chanel (1883-1971)

“I, who love women, wanted to give her clothes in which she could drive a car, yet at the same time clothes that emphasized her femininity, clothes that flowed with her body. A woman is closest to being naked when she is well dressed.”

© Condé Nast Archive/Corbis

The 19th of August marks what would have been the 130th birthday of Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel (1883-1971), a woman who revolutionized fashion with her emphasis on simplicity and sophistication. From little black dresses to bold accessories to classic suits, her innovative designs have influenced style for decades and continue to inspire modern aesthetics. Such enduring success is indicative of the unparalleled quality and timelessness of her work. More than forty years after her death, Chanel’s distinctive fragrances and handbags remain mainstays in the world of fashion.

In celebration of Coco Chanel’s incredible legacy, the Berg Fashion Library is offering a free article detailing the notable moments of her life and career – including the source of her legendary nickname. Interestingly, the name does not have its origin in fashion. Before becoming a renowned designer, Chanel worked as an evening concert singer at the café La Rotonde in Paris, where her rendition of “Qui qu’a vu Coco dans le Trocadéro” purportedly earned her the distinction of “Coco.”

© Philadelphia Museum of Art

Soon afterward, her fashion career gained traction: Chanel released her first ready-to-wear collection in 1913, and introduced her first couture collection to the public in 1917. Her inspiration came largely from sportswear and utilitarian dress, and her fashion perspective was always one of functionality and comfort — a defining philosophy that established her as a relevant designer well into her 70s. With a strikingly confident demeanor and an impeccable sense of style, Chanel continually set standards for imitation.

Following her death, Karl Lagerfeld is credited with revitalizing the iconic label after being appointed chief designer in 1983. By modernizing the brand’s classic elegance, he ensures that Chanel continues to be synonymous with high fashion — a statement of both classic and contemporary tastes.

Native of Southern California, Audrey Ingerson is a marketing intern at Oxford University Press and a rising senior at Amherst College. In addition to swimming and pursuing a double English/Psychology major, she fills her time with an unhealthy addiction to crafting and desserts.

Informed by prestigious academic and library advisors, and anchored by the 10-volume Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion, the Berg Fashion Library is the first online resource to provide access to interdisciplinary and integrated text, image, and journal content on world dress and fashion. The Berg Fashion Library offers users cross-searchable access to an expanding range of essential resources in this discipline of growing importance and relevance and will be of use to anyone working in, researching, or studying fashion, anthropology, art history, history, museum studies, and cultural studies.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only Art and Architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Both images courtesy of Berg Fashion Library. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post Celebrating Coco Chanel (1883-1971) appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAn ice cream quizWho were the Carlisle Commissioners? Part oneSophie Elisabeth, not an anachronism

Related StoriesAn ice cream quizWho were the Carlisle Commissioners? Part oneSophie Elisabeth, not an anachronism

Just who are humanitarian workers?

On the 19th of August, World Humanitarian Day, we honor the contributions of humanitarian workers around the world, especially those who have lost their lives helping people in war-torn societies. This day was first marked in 2008 through a Swedish-sponsored resolution in the United Nations General Assembly to commemorate 19 August 2003, when nearly two dozen humanitarian workers were killed in a suicide car bomb blast at the Canal Hotel in Baghdad, Iraq. Their number included Brazilian diplomat Sergio Vieira de Mello, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights; Egyptian Nadia Younes, his chief of staff; American refugee advocate Arthur Helton, of the Council on Foreign Relations; Iraqi chauffeur Ihsan Taha Hussein, of the United Nations Humanitarian Information Center; and 18 others — a total of 22 humanitarian workers of 12 different nationalities.

Not all incidents of violence in which aid workers are killed, wounded, or kidnapped lead to high-profile media attention. According to the Aid Worker Security Database, over 50 humanitarian aid workers have been killed per year since 2003, from a high of 127 in 2008 to a low of 54 in 2005. Already upwards of 72 humanitarian workers have died this year, with 117 more wounded or kidnapped, including 40 staff of international agencies and 149 nationals of the countries in which they served.

In acknowledging the sacrifice of those wounded or killed in the line of duty, we should not forget the thousands of people around the world for whom humanitarian service is their life’s calling. Researchers Peter Walker and Catherine Russ caution that “we simply do not know how many humanitarian aid workers there are in the world,” but estimate that “there are, at any one time, tens of thousands of humanitarian aid workers, performing a professional service, saving lives and livelihoods in-extremis.”

In honoring the work and sacrifice of humanitarian aid workers, we have the opportunity to reaffirm our commitment to humanitarian action and humanitarian principles.

Just what are humanitarian principles? They are at once legal, philosophical, and operational rules for responding to human suffering caused by war. At the most basic level, humanitarianism is rooted in four simple and elegant customary rules of armed conflict that underlie the 1949 Geneva Conventions and their 1977 Additional Protocols. The principle of humanity responds to the existential needs of human beings to shelter, food, clean water, medical care, human contact and community, and seeks to alleviate the suffering caused by war. The principle of distinction demands that civilians, their homes, hospitals, places of work, commerce, and worship not be treated as military targets. The principle of necessity requires that military force be used only against military targets in response to military threat. The principle of proportionality holds that responsive force should not exceed the violence to which it responds, and only when justified in the first instance by the principle of necessity.

Just who are humanitarian workers? They are diplomats, drivers, public health officers, lawyers, cleaners, social workers, and public servants. They work for the International Committee of the Red Cross, for national Red Cross and Red Crescent organizations, for UN agencies, and a myriad of grass roots, international philanthropic, and advocacy organizations. They work in booming metropoles and tiny border communities. They attend to the needs of war-effected populations, providing clean water and medical care, helping in the search for lost family members, and visiting POWs and people detained in various places. They appeal to and cajole, coordinate with and extol, and on rare instances even expose military, security, and civilian authorities. They speak truth to power and facilitate non-violent dialogue between armed and political groups. On a daily basis they improve the quality of life for war survivors and contribute to the cause of conflict resolution and post-conflict reconstruction.

Humanitarian workers carry out their daily jobs in situations of armed conflict where civilians are targeted, in violation of the Geneva Conventions and the tenets of international humanitarian law. The reality remains that humanitarian law and humanitarian principles are too often honored in the breach, and it is the humanitarian workers who jump into that breach to lessen the suffering of armed conflict. They put the principle of humanity to work, in the very circumstances that the principles of necessity, proportionality, and distinction have been violated. On the 19th of August we honor them and their work.

Jennifer Moore is on the faculty of the University of New Mexico School of Law. She is the author of Humanitarian Law in Action within Africa (Oxford University Press 2012).

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in Public International Law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: World Humanitarian Day 2013 logo via un.org. Used for the purposes of illustration.

The post Just who are humanitarian workers? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGender politics and the United Nations Security CouncilThe Detroit bankruptcy and the US ConstitutionCross-border suspicions and law enforcement at US-Mexico border

Related StoriesGender politics and the United Nations Security CouncilThe Detroit bankruptcy and the US ConstitutionCross-border suspicions and law enforcement at US-Mexico border

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers