Oxford University Press's Blog, page 914

August 12, 2013

10 questions for Wayne Koestenbaum

Each summer, Oxford University Press USA and Bryant Park in New York City partner for their summer reading series Word for Word Book Club. The Bryant Park Reading Room offers free copies of book club selections while supply lasts, compliments of Oxford University Press, and guest speakers lead the group in discussion. On Tuesday 13 August 2013, writer Wayne Koestenbaum leads a discussion on The Metamorphosis and Other Stories by Franz Kafka.

What was your inspiration for this book?

I chose Kafka’s Metamorphosis because he writes about punishment—and the sensation of always already being punished (even if punishment is not actually on the horizon)—with the greatest wit and acuity of any writer in history.

Where do you do your best writing?

Either in a café, a train, an airplane, or at my desk in my apartment.

Image Courtesy of Ad Hoc Vox by Andrea Bellu

Which author do you wish had been your 7th grade English teacher?

I actually liked my 7th grade English teacher! I wrote a play for him; it included a transsexual. But my runner-up English teacher, my dream-cast English teacher, would be Robert Walser, author of the divine Jacob von Gunten.

What is your secret talent?

I love to sleep.

What is your favorite book?

The Collected Poems of Frank O’Hara.

Who reads your first draft?

I read it. No one else. Ever.

Do you prefer writing on a computer or longhand?

I like both. At the moment, I’m writing a very long poem longhand, in notebooks. But most of the essays that appear in my newest book, My 1980s & Other Essays, I wrote on a computer or on a typewriter. (Yes, a typewriter!)

What book are you currently reading? (Old school or e-Reader?)

Brandon Downing’s Mellow Actions, a book of poems published by Fence Books, one of my favorite independent presses.

What word or punctuation mark are you most guilty of overusing?

These days I love the word “interstitial.” I overuse it.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you be?

A lost cause.

Did you have an “a-ha!” moment that made you want to be a writer?

When I read D. H. Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers, and I realized that emotional ambivalence was a fact of life, and the motivation for literature.

Do you read your books after they’ve been published?

I glance at them. I read random passages from them. Sometimes with satisfaction. Sometimes with shame.

Wayne Koestenbaum has published six books of poetry: Blue Stranger with Mosaic Background, Best-Selling Jewish Porn Films, Model Homes, The Milk of Inquiry, Rhapsodies of a Repeat Offender, and Ode to Anna Moffo and Other Poems. He has also published a novel, Moira Orfei in Aigues-Mortes, and eight books of nonfiction: The Anatomy of Harpo Marx, Humiliation, Hotel Theory, Andy Warhol, Cleavage, Jackie Under My Skin, The Queen’s Throat (a National Book Critics Circle Award finalist), and Double Talk. His next book, My 1980s & Other Essays, is forthcoming in August 2013 from FSG. Koestenbaum is a Distinguished Professor of English at the CUNY Graduate Center. His first solo exhibition of paintings was at White Columns gallery in New York in Fall 2012.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook. Read previous interviews with Word for Word Book Club guest speakers.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post 10 questions for Wayne Koestenbaum appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA children’s literature reading list from Oxford World’s ClassicsThe Poetic Edda and Wagner’s Ring CycleWhy we should commemorate Walter Pater

Related StoriesA children’s literature reading list from Oxford World’s ClassicsThe Poetic Edda and Wagner’s Ring CycleWhy we should commemorate Walter Pater

Family values and immigration reform

This summer has been pivotal for the American family. On 26 June 2013, the US Supreme Court ruled that the Defense of Marriage Act is unconstitutional, making same-sex couples eligible for the same federal benefits that opposite-sex couples have. The following day, the US Senate passed a bipartisan immigration reform bill that could grant legal status to many of the 11 million undocumented immigrants in the United States. For many Americans, the first decision is clearly about the family. But the second could be just as powerful in shaping American families in the coming years.

According to the Pew Hispanic Center, 4.5 million US citizen children have at least one parent who is undocumented. The Department of Homeland Security’s records reveal that close to 200,000 parents of US citizen children were deported from the United States between 1998 and 2007, a number that has only increased in subsequent years. The Applied Research Center estimates that over 5,000 of the US citizen children of these deportees are now in foster care. By providing temporary legal status and a pathway to citizenship for many undocumented immigrants, the Senate’s immigration bill has the potential to preserve family unity for millions of Americans. So why do so few Americans (and so few politicians) see immigration as a family issue?

The 4th Annual Coming Out of the Shadows March & Rally in Chicago. Hundreds of undocumented students and families and their supporters marched to protest the continued deportations under the Obama administration and to stand with those immigrants who continue to be criminalized. Photo by sarah-ji, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr

Responding to the Supreme Court’s decision on DOMA, former Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee tweeted “Jesus wept,” echoing the displeasure of many religious conservatives at the increasing legal and cultural acceptance of LGBT families in the United States. The strong connection between the religious right and “family values” since the 1980s has focused national attention on defending (or challenging, depending on the side you’re on) the dominance of a particular family model rather than on strengthening the diverse types of families that exist in the United States today.

Over the past 10 years, immigrant rights activists have fought to transform this way of viewing the politics of the family. Campaigns like La Familia Latina Unida, Families for Freedom, and the New Sanctuary Movement have tirelessly highlighted how deportation splits up families. They have drawn connections between religious teachings and immigration, expanding the national conversation about family values to include valuing immigrant family unity. For them, the passage of the Senate bill is a major step forward in keeping immigrant families together and in affirming their value.

Still, the bill does not go far enough for many families. Take Jean Montrevil. As a young man during the 1980s, he migrated legally to the United States from his native Haiti, green card in hand. A few years later, he was convicted of selling drugs during the height of the War on Drugs. He served an 11-year prison sentence. According to current US immigration policy, Jean is “the worst of the worst.” The Obama administration has focused on deporting people with criminal convictions, no matter how old their convictions are, how much they have been rehabilitated, or how much it could impact their families if they are deported.

Today, Jean is a business owner, a church member, a husband, and a father of four US citizen children. The main breadwinner for his family, his wife and children depend on his presence in the United States both emotionally and financially. Those who know Jean speak of him as a model friend and community member, as far from “the worst of the worst” as one could get. Yet the Senate’s immigration bill brings no relief for families like Jean’s. Jean could be detained and deported from the United States at any time, leaving his wife and children without their husband and father.

There is still time for the US House of Representatives to build an immigration bill that includes provisions for families like Jean’s, though the anti-reform sentiments in the House make it unlikely. Many of the strongest voices against a path to legalization and citizenship in the House are also opposed to the DOMA decision, arguing that recognizing same-sex marriage will damage the family. What remains to be seen is whether the same leaders will reject legislation that could keep immigrant families together.

Grace Yukich, an assistant professor of sociology at Quinnipiac University, is the author of the new book One Family Under God: Immigration Politics and Progressive Religion in America.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Family values and immigration reform appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe emergence of an international arbitration cultureIs yoga religious? Understanding the Encitas Public School Yoga Trial‘Yesterday I lost a country’

Related StoriesThe emergence of an international arbitration cultureIs yoga religious? Understanding the Encitas Public School Yoga Trial‘Yesterday I lost a country’

Is your doctor’s behavior unethical or unprofessional?

Doctors and residents working with patients at the JFK clinic in St. Louis. Photo by Mercy Health, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

During a difficult operation on a patient, a surgeon is handed the wrong instrument by the nurse assisting him. He screams at the nurse, “You gave me the wrong thing,” and throws the instrument across the room. The nurse immediately hands him the correct instrument, but she feels humiliated and the rest of the surgical team become anxiously fearful of another outburst. This scene is repeated all too often in hospitals, and the anxiety provocation in members of the health care team can lead to poor patient care. Is such behavior unethical or unprofessional — and is there any real difference between the two?At some point in his or her life, virtually every person will require the care or assistance of a health professional. It is reasonable to expect that physicians, nurses, and all others who contribute to health care, will act professionally. Note that I did not say ethically, but professionally; for example, the behavior of the surgeon cited above was not unethical, but certainly unprofessional. Physicians are capable of acting unprofessionally, but cannot act unethically, as ethical standards are part of their profession. Therefore, it behooves all patients to educate themselves on what constitutes “professional” and “unprofessional” behavior for those involved in health care.

First, consider that it takes a team to care for patients, and that not all team members are considered members of the same profession. For instance, almost everyone can identify physicians and nurses as health professionals, but many other health team members also belong to different professions that have different professional standards. Others members of the team can include physicians, nurses, public health practitioners, dentists, pharmacists, social workers, lawyers, clergy, economists/businesspersons, and ancillary service persons, such as those who provide nutrition and maintenance of the environment (can you imagine a clinical setting without a maintenance group to assure cleanliness and functioning of the equipment?).

It is critical for patients to distinguish between differing standards of professionalism, depending on the specific health team member involved in their care. This enables patients to have reasonable expectations for the way they should be treated by health professionals – before, during and after their treatment. But how many real or potential patients actually know the professional standards of those who will care for them? Probably very few, although most have expectations for how they believe a health professional should behave. Most people would probably have some idea of the Hippocratic oath for physicians, but not many actually have read it and understand what it means. Similarly, most have heard of Florence Nightingale, but few know about how she laid the foundation for professional nursing and that a Florence Nightingale Pledge exists.

It is safe to conjecture that the vast majority of individuals know more about what to expect before buying a car than they do about putting their lives in the hands of health care professionals. However, since your life is certainly worth more than any other possession, why not take the time and effort necessary to know each health team member’s standards of professionalism?

Dr. Catherine D. DeAngelis is University Distinguished Service Professor Emerita, professor of pediatrics emerita at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and professor of health policy and management at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. She served as the editor in chief emerita of JAMA, The Journal of the American Medical Association, and is the author of Patient Care and Professionalism.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Is your doctor’s behavior unethical or unprofessional? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA lost opportunity for sustainable ocean managementFive things to know about my epilepsyWhat is “toxic” about anger?

Related StoriesA lost opportunity for sustainable ocean managementFive things to know about my epilepsyWhat is “toxic” about anger?

The emergence of an international arbitration culture

International arbitration is an obscure field, even among lawyers. However, it is becoming more visible for the simple reason that the field is growing. Arbitration is now one of the most important means for the resolution of international business disputes, including — most notably from the public’s point of view — disputes between investors and the governments of countries in which they invest. Academics and policymakers have begun to describe international arbitration as a form of “global governance.”

Despite its importance, the actual decision-making of international arbitral tribunals remains opaque, especially when compared with that of courts. Normally, if you want to understand legal decision-making, you would just go and read some decisions, along with the laws on which those decisions are based. With international arbitration, you can’t do that, for two main reasons. First, most arbitrations are confidential. Even arbitrations involving public interests (like those between states and foreign investors) are largely closed to the public, although they are more transparent than they used to be. Most business-to-business international arbitrations are entirely secret; even the existence of the dispute is kept confidential. Second, there is no such thing as a law of international arbitration. Instead, arbitrations may be governed by any national or international set of laws chosen by the parties or by the tribunal. For example, many international shipping contracts are governed by English law, regardless of the nationality of the parties. Public disputes like investor-state arbitrations are governed by public international law, which is notoriously uncertain and incomplete.

With traditional tools of legal analysis rendered largely useless, the key to understanding the decision-making of international arbitrators, and thereby the kind of justice or kind of governance provided by international arbitration, is the emerging legal culture of the international arbitration community.

Lawyers tend to reject cultural explanations for legal outcomes. They are, after all, trained in the language of rules and precedents. Nevertheless, the notion of a legal culture is uncontroversial. Legal processes, like all human interactions, take place within a context of shared cultural norms and assumptions. Anyone who has had the slightest contact with a legal system knows that “the law” can never be reduced to just “the applicable legal rules.” If nothing else, the rules need interpreting, and there will always be situations for which no specific rule exists. Legal culture fills those gaps because it inculcates a collective, reflexive response that often obviates the need for argument. In many ways, the real purpose of a law school education is to instil common ways of thinking and reacting.

However, it is much harder to conceive of a shared legal culture in international arbitration, where lawyers and arbitrators don’t share a common nationality, language, religious/ethical system, or professional formation, or even access to a common body of governing laws and precedents. How can so diverse a group as international arbitration practitioners share a legal culture? Do they even constitute an identifiable community?

Despite their differences, international arbitration practitioners actually have more in common than the body of legal practitioners within any one jurisdiction. After all, the gap between the work environment, perspective, and career path of a high prestige corporation lawyer and a sole practitioner in any given city is so great as to make it hard to see any significant bonds of common experience and interest between them.

International arbitration lawyers tend to have attended a relatively small number of elite western universities (at least at the graduate level), to have developed their careers in large, corporate, usually Anglo-American firms or major universities, and to travel in both business and academic circles. They tend to share cosmopolitan, multinational backgrounds and speak multiple languages. They work repeatedly with each other and on disputes within a relatively narrow band of commercial subjects. It actually makes more sense to speak of an international arbitration community than to speak of a legal community within a country.

In my research on international arbitration, I have identified several individual norms that comprise international arbitration culture. Those norms inform a set of predictions about how arbitrators are likely to decide on commercial disputes and in turn how contract law will evolve through arbitral decision-making. In the absence of a shared set of codified rules or even published case reports, this kind of socio-legal analysis is one of the only available means for making these kinds of predictions.

In domestic legal communities, culture provides a shared frame of reference on the applicable laws and also fills the inevitable gaps in those laws. The same is true in the transnational sphere. Like so many other social fields, law has become simultaneously globalized and privatized. This transition has led to the emergence of a transnational community of international arbitration practitioners who have more in common with each other than they do with their compatriots. These kinds of stateless global communities are emerging in practically every sector of society and industry. (Think of the “Davos set.”) They are sufficiently closely-knit to develop their own informal codes and mores. For better or worse, if we want to understand how these communities are transforming our societies, we have to pay attention to their cultures.

Joshua Karton is an Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Law at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, Canada, where he has taught since 2009. A graduate of Yale (BA 2001) and Columbia Law School (JD 2005), he is a member of the New York Bar. He practiced as an associate in the litigation/arbitration group at Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton LLP in New York before pursuing his doctoral studies at Cambridge, from which he graduated in 2011 with a PhD in law. He is the author of The Culture of International Arbitration and the Evolution of Contract Law.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: iStockphoto. Do not use without permission.

The post The emergence of an international arbitration culture appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories‘Yesterday I lost a country’A bit of a virtual vade mecumThe fall of the Celtic Tiger – what next?

Related Stories‘Yesterday I lost a country’A bit of a virtual vade mecumThe fall of the Celtic Tiger – what next?

The fall of the Celtic Tiger – what next?

Traditionally the Irish, who can sing the dead to sleep, have been good at organising wakes. The financial wake of 2008 is another matter. It will be known as the year that initiated the great Irish financial crisis, just as 1847 has gone down as “Black 47,” the year when the Great Irish Famine peaked. “Black 47” involved a massive loss of population and a debilitating legacy of emigration. While not as catastrophic in human terms, “Black 2008” caused extensive damage to a sizeable part of Ireland’s economic fabric and had major repercussions for all parts of society. The scale of the economic and financial catastrophe that befell Ireland was virtually unprecedented in post-war industrial country history.

Ireland experienced four interrelated crises: a property crisis, a banking crisis, a fiscal crisis, and a financial crisis. Several key questions continue to be highly controversial. First, exactly who or what was “to blame” for what happened? While the international dimensions (the prevailing philosophy of light financial regulation, the inadequacy of the EU, and euro area architecture) were important, major responsibility lay at the domestic level. Very many were happy to benefit greatly from the artificial riches of the boom (especially public sector employees whose salaries soared as well as those involved in finance and construction). There were the “cheerleaders” (politicians of all parties and most of the media) and the “experts” (the Financial Regulator, the Central Bank, the Department of Finance, and much of the economist profession), none of whom shouted “stop.” All share responsibility, in different ways, for the fact that collectively Irish society “lost the run of itself.”

Second, once the financial crisis began to emerge in 2008, could anything have been done differently to reduce the massive costs to the taxpayer or to avert the indignity of the bail out from the EU/International Monetary Fund (IMF) troika in late 2010? This appears very doubtful. Given the paramount need to avert the collapse of the banks (with potentially catastrophic consequences), it is difficult to see how some form of comprehensive bank guarantee along the lines granted by the Irish government in late 2008 could have been avoided. At the same time, given the soaring underlying budgetary deficit, subsequent intervention by the EU/IMF became inevitable.

There is, however, a third very important question. Ireland has faced two financial crises in the last twenty five years. What conclusions can be drawn about the inadequacies of the Irish policymaking process? In the first place, there is a clear need to pay more attention to learning from elsewhere. Although Ireland’s property bubble was similar to that experienced by many other countries, many erroneously came to believe that this time was somehow “different.” History, including economic history and the history of economic thought, is still of paramount importance to avoid the excesses of those who think that the present is unique and the past of little relevance.

The absence of sufficient self-questioning and internal debate lies at the heart of the run up to the Irish crisis. Each component of the economic policymaking apparatus took solace from the belief that others must be doing a good job and from the praise lavished by official international agencies, most of whose judgments turned out to have been spectacularly wrong.

Any small economy on the periphery needs to guard against insular thinking by ensuring that key decision makers bring to the table sufficient technical expertise and exposure to today’s sophisticated environment. In Ireland’s case these elements were clearly lacking. There was also a noticeable tendency among senior officials to dismiss “contrarian” views while the boom was in full force. Those few who did raise unpleasant issues encountered considerable opprobrium — including from much of the media, lobby groups, and senior politicians. A “comfortable consensus” stifled serious analysis and the preparation of contingency plans to deal with perceived low probability, but high cost outcomes. Moreover, officials appeared reluctant to place their views explicitly on the record in advance of the emergence of a “consensus,” thus hindering the accountability that is critical for good governance.

It could be argued that some of these tendencies are inevitable in a small country like Ireland where sharp disagreements could cause friction to long standing personal relationships. However, the record of other similar countries does not suggest that this is inevitable. Ireland might not witness for a long time another property bubble, reckless lending by the banks, or a return to fiscal profligacy. But another crisis in the future — from whatever currently unknown source — cannot be excluded. A wide ranging systematic reflection on what is required for Ireland to establish a fundamentally sound policy making process is therefore essential.

Donal Donovan is a former deputy director at the IMF and a member of the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council. Antoin E. Murphy is a Professor Emeritus of Economics at Trinity College Dublin. Their book The Fall of the Celtic Tiger: Ireland and the Euro Debt Crisis was published by Oxford University Press in June 2013.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Dublin, Ireland – August 19, 2012: A series of rent/sales signs on several buildings in one of Dublin’s busiest streets show the remaints of the financial crisis in the country. © MichaelJay via iStockphoto.

The post The fall of the Celtic Tiger – what next? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThings to do in Orlando during AOM2013Five things you should know about the FedBeware of gifts near elections: Cyprus and the Eurozone

Related StoriesThings to do in Orlando during AOM2013Five things you should know about the FedBeware of gifts near elections: Cyprus and the Eurozone

August 11, 2013

Who inspired President Abraham Lincoln?

If Abraham Lincoln can be credited for delivering America from the grip of Civil War-era secessionism, he stood on the shoulders of two presidential giants. The iconic nineteenth century visionary honored the same constitutional ideals of Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore, emulating both men’s governmental principles and the extent to which they were willing to use force in the interest of national preservation. Here, Michael Gerhardt, author of The Forgotten Presidents: Their Untold Constitutional Legacy, explains the origins of Lincoln’s distinctive style of leadership, examining how these two political predecessors in particular shaped Lincoln’s legendary presidency.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Michael Gerhardt is the Samuel Ashe Distinguished Professor of Constitutional Law at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and author of The Forgotten Presidents: Their Untold Constitutional Legacy. A nationally recognized authority on constitutional conflicts, he has testified in several Supreme Court confirmation hearings, and has published five books, including The Power of Precedent. Read his previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Who inspired President Abraham Lincoln? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPresidential fathersNatural wonder or national symbol? A history of the Victoria RegiaReparations and regret: a look at Japanese internment

Related StoriesPresidential fathersNatural wonder or national symbol? A history of the Victoria RegiaReparations and regret: a look at Japanese internment

August 10, 2013

Reparations and regret: a look at Japanese internment

Twenty-five years ago today, President Ronald Reagan gave $20,000 to each Japanese-American who was imprisoned in an internment camp during World War II. Though difficult to imagine, the American government created several camps in the United States and the Philippines to lock away Japanese Americans under the guise of concern for their safety. We offer a brief slideshow of images from the time when thousands of people who were forcibly moved to camps, and the eventual response to this tragic grievance.

The movement begins

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Exclusion Order posted to direct Japanese Americans living in the first San Francisco section to evacuate. From the US Department of the Interior, 11 April 1942. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Japanese Americans in front of poster with internment orders. Photograph by War Relocation Authority. From the US Department of the Interior, National Archives. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Japanese family heads and persons living alone, form a line outside Civil Control Station located in the Japanese American Citizens League Auditorium at 2031 Bush Street, to appear for "processing" in response to Civilian Exclusion Order Number 20, San Francisco, 25 April 1942. From Central Photographic File of the War Relocation Authority. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

San Francisco, California. As a safeguard for health, evacuees of Japanese descent were inoculated as they registered for evacuation at 2031 Bush Street. Nurses and doctors, also of Japanese ancestry, administered inoculations. Evacuees were later transferred to War Relocation Authority centers for the duration, 20 April 1942. Photograph by War Relocation Authority. From the US Department of the Interior, National Archives. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Los Angeles (vicinity), California. Baggage of Japanese-Americans evacuated from certain West coast areas under United States Army war emergency order, who have arrived at a reception center at a racetrack, May 1942. Photography by the US Farm Security Administration. From the Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

San Francisco, California. Oldest member of the Japanese Methodist church, who came from Japan 50 years ago. He is at the Wartime Civil Control Administration station waiting for instructions regarding his evacuation to Tanforan Assembly center, 25 April 1942. Photograph by War Relocation Authority. From the US Department of the Interior, National Archives. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

World War II. Many of the Residents of Santo Tomas Internment Center built huts, called shanties, to escape crowded conditions in the dormitories. From US Army Signal Corps. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Florin, California. This American soldier of Japanese ancestry is shown at the railroad station of a small town in an agricultural community. He and nine other service men of Japanese ancestry received furloughs to enable them to come home to assist their families get ready for evacuation from their west coast homes. He is an older son, which, in the traditional Japanese family structure, means that much responsibility for their welfare depends upon him. He is the only American citizen in their family, 10 May 1942. Photograph by War Relocation Authority. From the US Department of the Interior, National Archives. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Granada Relocation Center, Amache, Colorado. Participants in the Bon Odori dance, August 14, sponsored by the Granada Buddhist Church, showing colorful kimonos. Spectators are in background, 14 August 1943. Photograph by War Relocation Authority. From the US Department of the Interior, National Archives. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Roosevelts visit

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Eleanor Roosevelt at Gila River, Arizona at Japanese, American Internment Center, 23 April 1943. Photography by Franklin D. Roosevelt's Administration. From Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, National Archives. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

President Ronald Reagan signing the Japanese reparations bill, 1988. From the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Kate Pais joined Oxford University Press in April 2013. She works as a marketing assistant for the history, religion and theology, and bibles lists. If you’re interested in the history of Japanese Americans, learn more in Eiichiro Azuma’s Between Two Empires: Race, History, and Transnationalism in Japanese America.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Reparations and regret: a look at Japanese internment appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCaptive Nations WeekNatural wonder or national symbol? A history of the Victoria RegiaTwo faces of the Limited Test Ban Treaty

Related StoriesCaptive Nations WeekNatural wonder or national symbol? A history of the Victoria RegiaTwo faces of the Limited Test Ban Treaty

Natural wonder or national symbol? A history of the Victoria Regia

Few could have imagined the elusive floral wonder retrieved in January 1837 from the heart of Guyana’s wildest jungles — and fewer still could have predicted the extent to which it would transform an entire continent’s cultural and aesthetic sensibilities. With leaves nearly five feet across, and a flower as large as eighteen inches in diameter, the Victoria Regia water lily, named after Queen Victoria (and now known as the Victoria amazonica), was initially discovered by explorer Robert Shomburgk in Great Britain’s first South American colony, evolving from lesser-known natural wonder to widely-recognized national symbol. Here, Tatiana Holway, author of The Flower of Empire: An Amazonian Water Lily, the Quest to Make it Bloom, and the World it Created, unravels the lily’s uniquely mysterious beginnings, its literal and figurative voyage across the Atlantic, and its enduring impact on the cultural landscape of the nineteenth century.

Click here to view the embedded video.

On Robert Shomburgk’s challenging journey into the thick of Guyana, and his world-changing discovery of the Victoria Regia water lily.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Tatiana Holway is an independent scholar and academic consultant with a doctorate in Victorian literature and society. She is the author of The Flower of Empire, in addition to several studies of Dickens and popular culture. Holway also serves on the advisory board for the Nineteenth-Century Collections Online archive.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Natural wonder or national symbol? A history of the Victoria Regia appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA lion: Joseph Paxton in the nineteenth century and todayTwo faces of the Limited Test Ban TreatyRe-introducing Oral History in the Digital Age

Related StoriesA lion: Joseph Paxton in the nineteenth century and todayTwo faces of the Limited Test Ban TreatyRe-introducing Oral History in the Digital Age

August 9, 2013

What’s your favorite Back to School memory?

Fading tans and falling temperatures mean it’s that time of year again. As the new academic term approaches, the annual Back to School frenzy has kicked into high-gear, with parents and students of all ages rushing to complete last-minute mall runs and Staples trips in preparation. Of course, this sense of a new beginning — and its accompanying exhilaration — leaves us navigating the chaos of the here-and-now with little retrospection. Yet decades from now, the same bundled nerves and feelings of anticipation surrounding our school-age years may be among the things we recall most sweetly. From nostalgic recollections to elementary-age regrets, Oxford University Press staff members share their fondest Back to School memories.

1941 All Clear at school. Hengistbury School, Southbourne, Bournemouth. Photo by Philip Howard, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

“As the youngest child in a family with three boys, my Back to School clothes often consisted of my older brothers’ hand-me-downs. I remember feeling embarrassed and self-conscious about my not-so-new Back to School attire. As an adult, a lifelong friend told me that she thought I was cooler than the others because I didn’t show up the first day/week dressed in some crazy trendy outfits our peers plucked from the racks of the Pyramid Mall over in Saratoga, the closest mall to my hometown in upstate New York. Cool is arbitrary, I guess. Ron Wood said it best when he sang, ‘Wish I knew then, what I know now when I was younger.’”

—Christian Purdy, Director of Publicity, OUP USA

“After a summer of part-time work, babysitting, and everything I could find, I remember taking my earnings and going to buy one of my first pairs of Chuck Taylors. Something about the independence of getting them myself imbued them with extra greatness. They were this really intense Kelly green, and I drew patterns on the heel of the right shoe during study halls. They gave a spring to my step almost every single day of high school (by the end of which, they had promptly fallen apart).”

—Kate Pais, Marketing Assistant (Academic/Trade), OUP USA

“Hmmm… I remember spending most of August 1996 arguing that it was absolutely necessary that my parents buy me the burgundy JanSport backpack with a suede leather bottom and flower stitching on the smaller compartment. I also promised that, yes, if they were to comply I not even ask for a new backpack the next school year. I lied.”

—Leslie Schaffer, Retail/Wholesale Sales, OUP USA

“I remember when I was moving to a new secondary school. My primary school had only had about 80 people in it, so it was really, really small and everyone knew everyone. However, my secondary school had 800 and so I was absolutely terrified by the idea of being surrounded by so many people. I remember my Mum buying me a whole set of uniform which was way too big for me and all starchy and stiff because it was so new. I had this long, blue tartan, pleated skirt. Anyway, on the first day I got to school feeling ridiculous but thinking ‘everyone will look just like me — it’ll be fine.’ It wasn’t. Everyone, and I mean everyone in the entire school had a totally different skirt — theirs were straight, not pleated, and far shorter than mine. (Mine was, inexplicably, halfway down my calves.) Of course, my Mum wouldn’t buy me another for at least a term, so I had to spend the first term of my secondary school life with this tent of a skirt — heavily pleated and below my knees. I remember that whenever it was windy, it used to balloon out — sort of like the Marilyn Monroe thing, but without any charm or grace whatsoever.”

—Jessica Harris, Online Product Marketing Intern, OUP UK

“Back to School for me always meant getting a new pencil case. The rubbery plastic type, with the zip at the top. That smell always takes me straight back to WH Smith in August, a few weeks before the new term. Who was I going to be this year? Open and honest, showing my personalised pencils and zoo animal rubbers through a clear plastic case? A bit dark and mysterious (for a nine-year-old), a creepy crawlies cover hiding the never-used set square within? (I still don’t think I’ve ever used a set square.) I was given a cuddly panda pencil case once. I loved her but she didn’t have the right smell. She had to stay at home.”

—Debbie Sims, Publicity Administrator, OUP UK

“The first day of school! The new colorful pens! The new blank notebooks, blinding white and waiting to be filled with brilliant insights! The smell of the library crammed full of old pages! Comparing schedules with friends and finding out you had classes together! Yes, it was always great to go back to school each year; to do something familiar yet new, and as often happened, come away enlightened.”

—Lana Goldsmith, Publisher Services, OUP USA

“My favorite Back to School memory was back in elementary school, where just before the year started, my school would list the upcoming year’s classroom assignments in the local newspaper. (Side note: I am from a very, very small town.) I remember being so excited and nervous looking over these, as you couldn’t wait to see if you got the teacher you wanted (or the one you really didn’t), or, more importantly, if your best friends were in your class (or if they sadly weren’t).”

—Alyssa Bender, Marketing Associate, OUP USA

“My favorite Back to School memory would have to be buying new school supplies. I would also go with my mom to a local drug store that had two narrow little supply aisles and stock-up on whatever the “in” school supply was at the time: Five Star notebooks, binders with slots for photos, purple glue sticks. But my favorite would have to be the reign of Lisa Frank folders.”

—Penny Freedman, Marketing Coordinator, OUP USA

“My favorite Back to School memory would be receiving our new textbooks and writing books on the first day of term, then taking them home to cover, in anything from wrapping paper to wallpaper!”

—Julie O’Shea, Senior Marketing Executive, OUP UK

Don’t forget to share your favorite Back to School memory using the hashtag #BTSmemory, and we’ll be sharing along with you across our social media. And if you’re looking to stock up, check out these popular Oxford University Press USA Back to School titles, including our celebrated Compact Oxford Dictionaries series. See you in school!

Sonia Tsuruoka is a social media intern at Oxford University Press and a student at Johns Hopkins University. Her writing has appeared in a variety of publications, including Slate Magazine and the JHU News-Letter.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only education articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Pile of books isolated on white background. © thebroker via iStockphoto.

The post What’s your favorite Back to School memory? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA lost opportunity for sustainable ocean managementIs yoga religious? Understanding the Encitas Public School Yoga TrialHead Start: Management Issues

Related StoriesA lost opportunity for sustainable ocean managementIs yoga religious? Understanding the Encitas Public School Yoga TrialHead Start: Management Issues

Breaking Bad: masculinity as tragedy

In the opening shots of Vince Gilligan’s Breaking Bad, a pair of khaki pants is suspended, for a tranquil moment, in the desert air. The pants are then unceremoniously run over by an RV methamphetamine lab with two murdered bodies in back. When the camper crashes into a ditch, the driver Walter White (played by Bryan Cranston) gets out, tucks a gun in in his underwear, takes a camera, and records a death note for his wife and son. He is wearing tighty whities.

We return this month to witness what, the series has led us to expect, will be Walt’s spectacular fall. The first half of this final season, which aired last summer, saw Walt at a brutal extreme, high on the power of the drug ring he has created. He began the series humiliated and enfeebled: washing cars to supplement his income as a high school chemistry teacher, terminally ill with lung cancer. His defiant rise to power was marked by cunning, manipulation, and violence — blowing up a building with himself inside of it, duping his only friend and sidekick, cowing his wife Skyler to the point that she is evacuated of any feelings for him but fear. Walt’s other victims have fared worse, leaving a trail of destruction that has drained our sympathy from him and prepared us for his reckoning. His journey from emasculated pushover to alpha-male kingpin has reached its apogee. Walt has become the provider, the head of household; he is finally “wearing the pants” in the relationship.

How could this end but in tragedy? The closer we look at Walt’s emergent masculine identity — his power to father, to provide, to be free — the more corrosive, and terrifying, it appears. We begin with the logic of the man of the house, the idea that, as Walt puts it in the death note of the pilot, “no matter how it may look, I only had you in my heart.” We view financial stability for Skyler, the new baby, and Walter Jr., who has cerebral palsy, as a preeminent, perhaps even primal need. Perhaps we even warm to the deeply misogynistic idea that a man is the victim of his voracious, unappeasable family, who are holding him back from personal freedom. And for our growing sympathies with Walt’s notion of manhood — let’s call it masculinity-as-martyrdom — we have a reward: we see Walt destroy what he claims to love.

Tragedy has often left us deeply uneasy about tough-guys with pants issues, launching radical critiques of its masculine “heroes.” From Oedipus Rex to Death of a Salesman, the genre presents protagonists who unleash their inner, violent, masculine needs on their families. Emasculated, desperate, crushed by forces outside of their control, who do these men annihilate? Inevitably, tragically, their families, together with themselves.

Breaking Bad places this conflict in the modern, molecular world. When Walt names his drug lord alter-ego “Heisenberg,” he alludes to the discoverer of the uncertainty principle, the fundamental limit in accuracy of physical measurements. When we look at something hard enough, when we distill it to its most fundamental properties, we both see, and cannot see its horror. “Breaking” Walt’s masculine drive for jouissance, reducing it to its chemical makeup, still we cannot see it for what it is, cannot fully acknowledge the terrible entropy at its root.

We experience a similarly terrible gaze, anticipating quantum mechanics, in the denouement of Othello. When the great general’s wife lies suffocated on the bed and Emilia’s stabbed body lies next to her, Lodovico commands Iago to fix his gaze on the wedding sheets, and we cannot avoid staring with him:

Look on the tragic loading of this bed;

This is thy work. The object poisons sight,

Let it be hid. (5.4.426-28)

Aristotle might call this anagnôrisis or “recognition” — the sublime knowledge that is naturally dictated by the events of the plot, a realization of what in some sense we already know. But why, then, is this spectacle “poison”? Why must it be hidden as soon as it is revealed? Is it in fact the “viper” Iago’s work, or is it Othello’s, or even our own? Do we see in that bed our own relentless gaze on what happens in Desdemona’s bed, our bloodlust as eager onlookers of this tragedy, telling us something about ourselves?

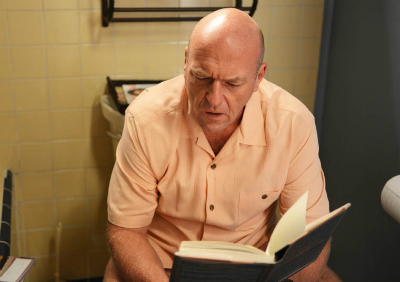

In the final shots of Breaking Bad on air last summer, Walt’s brother-in-law and foil, the FBI agent Hank, sits on the toilet with a copy of Leaves of Grass inscribed by Walt’s victim and former co-conspirator, “To my other favorite W. W.” Hank has already seen these initials in his investigation and, at this moment of anagnôrisis, recognizes what he has already half-known. Hank’s trajectory in the series has been the direct inverse of Walt’s, from fun-loving tough-guy to clueless Gringo, and only now, on the toilet with his pants down, does the sinking feeling set in. Emasculated, humiliated, he glimpses a hint of Walt in himself — a hint of what a tragic “hero,” self-martyred and desperate, is capable of. Tragedy brings us to this threshold, to the edge of what masculinity means — continues to mean — to its victims.

Scott A. Trudell is Assistant Professor of English at the University of Maryland, College Park. He is currently writing a book about song and mediation in Renaissance England, and he is a contributor to Early Modern Theatricality: Oxford 21st Century Approaches to Literature (Oxford University Press, 2013) edited by Henry S. Turner. Follow him on Twitter @Scott_Trudell.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only television and film articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: All images from Breaking Bad on AMC. Images used for the purposes of illustration. All rights reserved.

The post Breaking Bad: masculinity as tragedy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIn memoriam: George DukeNine curiosities about Ancient Greek dramaWimbledon, Shakespeare, and strawberries

Related StoriesIn memoriam: George DukeNine curiosities about Ancient Greek dramaWimbledon, Shakespeare, and strawberries

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers