Oxford University Press's Blog, page 910

August 24, 2013

The Cuadrilla fracking site: a policing dilemma

I’m not claiming to be clairvoyant, but the current controversy concerning Cuadrilla’s fracking site at Balcombe, West Sussex, is eerily similar to one of the five scenarios that form the foundations for the book I and my colleagues, John Kleinig and Martin Wright have recently published. (Our contributors — police officers and academics — attempt to solve these wickedly contrived scenarios that pose acute dilemmas to hypothetical police officers.)

Envisage a police force in whose area a nuclear power plant is due for renewal on its current site. A private overseas company, about which there have been recent negative exposés, is to build it. Protests are planned, but there is no intelligence suggesting that violence will be used, although protesters plan to invade the site. On the other hand, the company is threatening government that if protesters succeed even in disrupting this operation, they will withdraw from all future power plant construction. The government communicated this message to the police, with the added reminder that such power plants are part of the ‘critical national infrastructure.’ So the police find themselves in a dilemma: the recent strictures of Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Constabulary — that police have a duty to facilitate peaceful protest — should still be ringing in their ears, but raw national interest has a firmer grip on other parts of their anatomy. (As some American wit once said, “When you got ‘em by the balls, the hearts and minds will follow.”)

A similar situation has arisen in Balcombe: Cuadrilla is a business and if protesters succeed in shutting down an exploratory drilling sight, they will increase the costs of such exploration and deter this and other energy companies from conducting further explorations — which is precisely their strategic aim. The police would hardly need reminding of this reality and they would be aware that energy production is essential to the national interest — unless we close the looming energy gap the lights will go out. We need not search for a shadowy figure communicating these imperatives to the police, all they need do is to read the newspapers and watch television.

For environmentalists, fracked gas poses almost as big a threat as nuclear power. If it turns out to be abundant, is cheap to exploit, and produces lower carbon emissions than other fossil fuels, then not only the United States, but other countries too, will be tempted to rely on it. This would not only continue to produce dangerously high carbon emissions into the atmosphere, it would do so for longer because the incentive would be to continue fracking rather than developing alternatives. For environmentalists now is the time to act, because they can make a significant impact on the costs of exploration. It is a case of passion versus interests.

The police are caught on the horns of this particular dilemma because, on the one hand, the protesters are merely asserting their rights under the European Convention and there has been no hint of violence. Don’t forget, as HMCIC pointed out, that protest can be both ‘unlawful’ (much of it is) whilst still being ‘peaceful’. On the other hand, if the police facilitate peaceful protest designed to disrupt the drilling operation, they may be harming the national interest. It isn’t simply a case of police standing between parties opposed to each. It is a conflict essentially between the law and the national interest.

The police are caught on the horns of this particular dilemma because, on the one hand, the protesters are merely asserting their rights under the European Convention and there has been no hint of violence. Don’t forget, as HMCIC pointed out, that protest can be both ‘unlawful’ (much of it is) whilst still being ‘peaceful’. On the other hand, if the police facilitate peaceful protest designed to disrupt the drilling operation, they may be harming the national interest. It isn’t simply a case of police standing between parties opposed to each. It is a conflict essentially between the law and the national interest.

As a student of protest politics, I find this particular case fascinating. There is no lack spokespeople promoting sadly neglected causes célèbre, such as the current campaign to cease the consumption of octopus (although why anyone would pay to eat rubber defeats me!). After all, ‘save the whale’ and the campaigns against seal culling, became the pin-ups of the early environmental and animal rights movements. Such campaigns have seen considerable success with global restrictions on whale-hunting enforced (with limited success) for years and the annual seal cull a thing of distant memory. So why aren’t we as concerned with the humble octopus as we are about fracking?

Well fracking illustrates a well-known truth about protest politics: size matters and friends in high places matter even more. Fracking is such a potent issue because it unites two sources of concern that are only rarely bedfellows: environmentalism and Nimbyism. Environmentalists don’t want any form of energy production that increases global warming. They are quite content to cover the rural hinterland in wind farms, but a fracking plant — no thank you! Nimbys want their enjoyment of the surrounding countryside to be left unspoiled. They revolt against the prospect of wind farms and the idea of fracking plants blighting the view. (I write this as an unapologetic Nimbyist, as I gaze across the rural idyll in which I live!) The overlap is purely tactical: join forces and achieve the limited goal.

Protesters are invariably uncompromising about their causes, but their passion is only rarely understood and even more rarely evokes agreement from a wider public. It is a fact of life that those groups who lack public understanding of and sympathy for their cause can be policed more robustly than those who enjoy understanding and sympathy. Consider how football supporters were, and still are, treated by the police. If the police did likewise to Save the Children, there would be hell to pay! Environmentalism has succeeded in winning significant rhetorical support in the public sphere, but suffers from its hippie associations. Because fracking stimulates our Nimby instincts, they can rely upon powerful, articulate people who represent a local community in a leafy village to spread the message. I’m willing to wager that there are, among the good citizens of Balcombe, a clutch of media people whose skills are being used to maximum effect.

So the scene is set. The police find themselves torn between powerful, contradictory forces — national interest and passionate opponents. We’ll just have to await developments to see how police in a real-life, wickedly difficult scenario actually resolve it!

P.A.J. Waddington is Professor of Social Policy, Hon. Director, Central Institute for the Study of Public Protection, The University of Wolverhampton. He is the co-editor of Professional Police Practice: Scenarios and Dilemmas with John Kleinig and Martin Wright, and a general editor for Policing. Read his previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Police Lantern In England Outside The Station. By Stuart Miles, iStockPhoto.

The post The Cuadrilla fracking site: a policing dilemma appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIs Edward Snowden a civil disobedient?Remembering the slave tradeAssembling a coherent picture in the Daniel Pelka case

Related StoriesIs Edward Snowden a civil disobedient?Remembering the slave tradeAssembling a coherent picture in the Daniel Pelka case

Ten facts about toasts

On 4 August 1693, Dom Perignon invented champagne, or so the story goes. The date is no doubt made up, sparkling wines had existed long before the 17th century, and the treasurer of the Abbey of Hautvilliers actually did everything he could to prevent wine from refermenting. But who wouldn’t mind a glass of bubbly to celebrate?

“Toasting” comes from the piece of toast that was put into loving cups, communal drinks that were passed around at banquets, at old universities.

In 1918, as World War I was ending, Sir Winston Churchill proclaimed, “Remember, gentlemen, it’s not just France we are fighting for, it’s Champagne!”

A thought-provoking toast from the time of the Cold War (c. 1955): “Here’s to today! For tomorrow we may be radioactive.”

After the American War of Independence, dinners had to be accompanied by thirteen toasts: one for each of the states of the Union at that time. This tradition — unsurprisingly — faded, but persisted during Fourth of July celebrations for many years.

Sláinte (‘health’) is the most common Irish toast, and the word has passed into general use in Ireland and among the Irish abroad.

A ‘Yorkshireman’s Toast’ is as follows: “Here’s to us, all of us; may we never want anything, any of us; nor I either.”

When giving a toast to the monarch, everyone must stand — except for members of the Royal Navy, who are allowed to sit. Why? The story is that when George IV acknowledged a toast in his honour on a ship, he bumped his head on a beam as he stood up.

During the American War of Independence, toasts were usually curses, such as: “To the enemies of our country! May they have cobweb breeches, a porcupine saddle, a hard-trotting horse, and an eternal journey.”

A wonderful Scottish toast from the eighteenth-century goes: “Here’s tae us; wha’s like us?

Gey few, and they’re a’ deid.” [Here’s to us; what’s like us? Very few and they’re all dead.]

And finally, a fantastic toast from Jonathan Swift: “May you live all the days of your life.”

Jessica Harris graduated from Warwick University with a degree in Politics, Philosophy, and Economics and has been working as an intern in the Online Product Marketing department in the Oxford office of Oxford University Press.

Oxford Reference is the home of Oxford’s quality reference publishing, bringing together over 2 million entries, many of which are illustrated, into a single cross-searchable resource. Both fully integrated and cross-searchable, Oxford Reference couples Oxford’s trusted A-Z reference material with an intuitive design to deliver a discoverable, up-to-date, and expanding reference resource.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only food and drink articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Cheers! Two champagne glasses. © karandaev via iStockphoto.

The post Ten facts about toasts appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA quiz on the history of sandwichesThe 1812 Overture: an attempted narrationCelebrating Coco Chanel (1883-1971)

Related StoriesA quiz on the history of sandwichesThe 1812 Overture: an attempted narrationCelebrating Coco Chanel (1883-1971)

The ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum

The historic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79 may have buried Pompeii and Herculaneum under a thick carpet of volcanic ash, but it preserved what is surely our most valuable archaeological record of daily life in Ancient Rome to date. Hundreds of excavated artifacts — from bronze fountain spouts to terracotta statuettes — have uncovered the public and private rituals of men, women and children, providing a timeless and thought-provoking window into classical antiquity. Here, Paul Roberts, author of Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum, compiles a visual guide and intimate examination of Roman life interrupted by the devastation of natural disaster.

BRONZE LANTERN, ORGINALLY FITTED WITH THIN SHEETS OF TRANSLUCENT HORN (FROM VESUVIAN AREA)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

EMERALD GREEN GLASS DISH IN THE FORM OF A BOAT, POSSIBLY FOR CONDIMENTS (FROM POMPEII)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

FRESCO SHOWING A STILL LIFE OF A HARBOR SCENE (FROM BOSCOREALE)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

FRESCO SHOWING A MUSIC LESSON (FROM POMPEII)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

TERRACOTTA STATUETTE OF PAN AND THE GOAT, POSSIBLY MADE BY JOSEPH NOLLEKENS

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

BRONZE WIND-CHIME IN THE FORM OF A PHALLUS WITH HANGING BELLS (FROM POMPEII)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

BRONZE FOUNTAIN SPOUT IN THE FORM OF A PINE CONE (FROM POMPEII)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

MOUNT VESUVIUS SEEN FROM POMPEII

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Paul Roberts is the author of Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum. He is head of the Roman section in the Department of Greece and Rome, and is responsible for all of the Roman collections at the British Museum.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles via email or RSS.

Image credit: All images from Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum. All rights reserved.

The post The ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhose Odyssey is it anyway?Nine facts about athletics in Ancient GreeceImages to remember the Battle of Plataea

Related StoriesWhose Odyssey is it anyway?Nine facts about athletics in Ancient GreeceImages to remember the Battle of Plataea

August 23, 2013

Is Edward Snowden a civil disobedient?

Since he exposed himself in June 2013 as the source of the NSA leaks to the Guardian and Washington Post, former CIA analyst Edward Snowden has been called many things including a hero, a traitor, a whistleblower, and a civil disobedient. The last of these labels tracks a much-debated philosophical notion and a practice made famous by Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., Aung San Suu Kyi, and others. Paradigmatically, civil disobedience is a constrained, conscientious, and communicative breach of law that aims to raise awareness about a cause and bring about lasting changes in law and policy. Not all civil disobedients champion worthy causes. But, their self-restrained willingness to stand up for what they believe despite the personal risk means that their disobedience should be taken seriously and tolerated if possible. Now, is Edward Snowden a civil disobedient? And if he is, how should society and the law treat him?

In his favour, Snowden willingly exposed himself to considerable personal risk by leaking information about the NSA programs Prism, Boundless Informant, and XKeyscore, which collect and analyse massive amounts of personal data on Americans and foreigners. Moreover, Snowden acted non-evasively by revealing himself as the source of the leaks. Finally, by his own account, he acted with the aim, and he certainly achieved the effect, of initiating a public debate about the legitimacy of NSA and GCHQ activities.

In his favour, Snowden willingly exposed himself to considerable personal risk by leaking information about the NSA programs Prism, Boundless Informant, and XKeyscore, which collect and analyse massive amounts of personal data on Americans and foreigners. Moreover, Snowden acted non-evasively by revealing himself as the source of the leaks. Finally, by his own account, he acted with the aim, and he certainly achieved the effect, of initiating a public debate about the legitimacy of NSA and GCHQ activities.

But are Snowden’s leaks sufficiently constrained to warrant the label ‘civil disobedience’? His acts were neither violent nor coercive in any straightforward sense, but they’ve had repercussions for his society and the global community. Just how serious are those repercussions? Some US officials, such as NSA Director Keith Alexander, say Snowden’s disclosures have done irreversible and significant damage to the United States and its allies (whose citizens are, of course, among those under surveillance). But other US officials, such as newly appointed National Security Advisor Susan Rice, say the diplomatic consequences at least are not that significant. Given US officials’ political interests in keeping these programs secret, their word isn’t the best gauge of the seriousness of Snowden’s acts. It’s worth remembering that similar complaints about seriousness were made against civil rights activists in the 1960’s. Martin Luther King, Jr. stated then that “Actually, we who engage in nonviolent direct action are not the creators of tension. We merely bring to the surface the hidden tension that is already alive.” In short, the responsibility for questionable, rights-intruding programs that have little judicial or legislative oversight lies with those who implement them, not with those who seek to expose them for public debate.

Other supposed points against Snowden’s credentials as a civil disobedient are, first, that his flight from the United States to Hong Kong in May and his flight to Russia in July in pursuit of temporary asylum seem inconsistent with a civil disobedient’s willingness to accept the personal risks of dissent. Second, as pointed out by the US government, there seems to be an inconsistency between Snowden’s declared commitment to transparency and his choices of Hong Kong and Russia as places of refuge.

These criticisms have bite if we embrace a narrow account of civil disobedience such as John Rawls’s, which says that civil disobedients must be willing to accept not only the risk of punishment, but punishment itself to show that they have a broad fidelity to the legal system and are unlike ordinary offenders. By evading US authorities, Snowden has shown that he’s unwilling to do this. But Rawls’s narrow view of civil disobedience can be challenged. The willingness to accept punishment often doesn’t reflect fidelity to a legal system. It reflects instead a choice of strategy since punishment can bring attention to both a cause and its champions. Moreover, Snowden hasn’t had much choice about his protectors. He’s reportedly applied to 27 countries for asylum without success and he faces serious charges in the United States, so his conscientious commitment to transparency isn’t necessarily in doubt. But now that he has successfully influenced the public perception of his acts and has limited the United States’s options in how it treats him, he’d do well to return to face the criminal justice music despite the personal costs it’ll bring. Doing so would confirm that his acts are civilly disobedient.

Facing the music may not be as jarring as Snowden expects because, although many judges and juries view civil disobedience with scepticism, not all do. Some recognise that civil disobedience is a vital practice in a democracy. It can rectify deficits in democratic debate, can jolt us out of our complacent assumptions, and can bring about much needed moral revolutions. Many judges praise the character of the civil disobedients they see and do what they can to soften the blow of the law. May it be so for Edward Snowden.

Kimberley Brownlee is an Associate Professor of Legal and Moral Philosophy at the University of Warwick. She is the author of Conscience and Conviction: The Case for Civil Disobedience (OUP, 2012), which she has discussed in interviews with 3:am Magazine and New Books in Philosophy. She is currently working on a book provisionally titled No Entry: The Evils of Social Deprivation and the Ethics of Sociability.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: The shadow of a man crossing the street. Textured. © Ivan Bastien via iStockphoto.

The post Is Edward Snowden a civil disobedient? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRemembering the slave tradeWhat’s really at stake in the National Security Agency data sweepsReligious displays and the gray area between church and state

Related StoriesRemembering the slave tradeWhat’s really at stake in the National Security Agency data sweepsReligious displays and the gray area between church and state

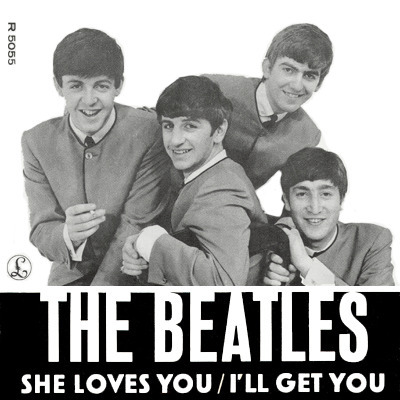

The Beatles and “She Loves You”: 23 August 1963

As the summer of 1963 drew to a close and students prepared to return to school, the Beatles released what may have been their most successful single. “She Loves You” would top the British charts twice that year, remain near the top for months, and help to launch the band into the American consciousness. Some of their other singles would remain at the top longer, but few would have the lasting cultural impact of this disc.

With the success of “From Me to You” in British charts (followed almost immediately by Billy J Kramer’s version of Lennon and McCartney’s “Do You Want to Know a Secret”), the Beatles began thinking about their next recording. “Love Me Do” started the year in the top 20, “Please Please Me” climbed to the top five, and “From Me to You” undeniably sat at the top for several weeks. For Lennon and McCartney, the challenge seemed to be how to perfect a model that had worked so well with the previous songs. Personal pronouns? Check. Up-tempo optimism? Check. Vocal harmonies? Check. Repeated song hook? Check. Stopping the song with punctuating chords? Check. Isley Brothers’ “ooo” performed while shaking heads? Check. All of these devices (and a few others) had been successful in their songs and performances in 1963. The trick would be to make it all sound new again and to provide something that they could perform live. What they created may be the ultimate example of how the Beatles contributed to the creation of Beatlemania. Indeed, McCartney has described “She Loves You” as “custom-built for the record we had to make.”

Newcastle, 26 June 1963. Like so many touring musicians, Lennon and McCartney found themselves stuck in a hotel room with little to do; but, with a looming recording session, they set to work on a song. Their inspiration may have been a tune written by London songwriter and producer Tony Hatch that American Bobby Rydell had recorded and that had achieved modest success on British charts. “Forget Him” follows the familiar model of songs that complain in the first person to a former lover that the new lover will never offer what the author could. McCartney would take this conceit one step further by making the singer an observer of a relationship who conveys a “message” from one lover to the other.

The choice of the words “yeah, yeah, yeah” also carried an obvious coded ideological meaning for younger fans. When the songwriters returned to McCartney’s Liverpool home the day after Newcastle and played their new creation for his father, he complained about the distinctly American flavor of the language, instead preferring “yes, yes, yes.” In a context where the Beatles’ primary audience (teens) sought to distinguish themselves from their parents and their parents’ generation, the simple use of language could prove a subtle and effective marker. “Yeah, yeah, yeah” evoked both rebellion and an innocence of teen infatuation that parents might protest, but could not ban, especially coming as it did in the context of a song. They might correct their children’s speech, but the words to a song were a kind of excusable poetic extravagance.

The core musical model lies in the responsorial structure of rhythm-and-blues and gospel. McCartney has described beginning “She Loves You” as an “answering” song, meaning that someone would sing “she loves you,” to which “the others would do the ‘yeah, yeah, yeah’ lines…”

London, 1 July 1963. Lennon and McCartney apparently arrived at EMI with some well-formed ideas about how they wanted the band to perform “She Loves You,” a remarkable accomplishment given how touring afforded them little time to prepare. When the songwriters played the song for Harrison and Starr in studio two on this Monday (five days after they had written it), the bandmates quickly reacted by inventing musical responses. All of this speaks to a major change in how they prepared for recording. With “Love Me Do” and “Please Please Me,” they had already included the music in their stage performance so that when they arrived at the studio, they knew their parts and had established appropriate roles. Now, Lennon and McCartney needed to anticipate how Harrison and Starr might contribute in order to expedite the recording process. They certainly allowed their bandmates flexibility in how they might articulate their musical contributions with the assured knowledge that what they created would be perfect — but they also would have given them parameters.

The entire session bubbles with self-confidence and enthusiasm. A well-crafted song requires a convincing performance to be successful and the Beatles deliver “She Loves You” with enough energy to illuminate London. The opening drums of the performance almost burst through the speakers and grab the listener by the chest, eschewing the cymbals for toms that pound like an imminent heart attack. Not to be outdone, the vocals race with adrenaline through the microphone cables, the singers perhaps reacting to the fans that had invaded the sanctity of EMI’s Abbey Road recording facilities this day, overwhelming the staid security, racing through the halls, and briefly penetrating even studio two.

Click here to view the embedded video.

23 August 1963. British reviewers generally expressed disappointment with the release. David Jacobs complained that he found “the new Beatles record rather disappointing” and fellow disc jockey Brian Matthew complained that “She Loves You” was “the first Beatles record that hasn’t knocked me out.” Matthew projected that the band “rested far too much on the success they’ve already had” and that this release fell “far short of their other discs.” Reviewer Don Nicholl similarly complained “what a pity it is to waste such energy and rhythmic enthusiasm on such an ordinary song. The lyric is feeble and unimaginative.” Nevertheless, all agreed that “She Loves You” would be a hit. They were right about that assessment.

Gordon R. Thompson is Professor of Music and Chair of the Department of Music at Skidmore College. His book, Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out, offers an insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. Check out Gordon Thompson’s posts on The Beatles and other music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Cover art for the single “She Loves You” by The Beatles. (c) Parlophone. Used for the purposes of illustration. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Beatles and “She Loves You”: 23 August 1963 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFive things you didn’t know about DebussySeven things you didn’t know about “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”A quiz on the history of sandwiches

Related StoriesFive things you didn’t know about DebussySeven things you didn’t know about “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”A quiz on the history of sandwiches

Remembering the slave trade

Today is International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition, established by UNESCO “to inscribe the tragedy of the slave trade in the memory of peoples.”

That tragedy was the development of, in Robin Blackburn’s words, a “different species of slavery.” One that took the artisan slavery of old (consisting in the main of handfuls of slaves working on small estates or as domestic servants) and industrialised it, creating plantations in the Americas which fed the near insatiable appetite of Europeans for sugar, coffee, and tobacco.

Thanks to the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, we know that between the 16th and 19th century, more than 12.5 million individuals were taken as slaves from Africa.

In essence there were two transatlantic slave trade routes which emerged as a result of international agreements. Portugal, and later an independent Brazil, carried out an unhindered trade south of the equator until late into 19th century. This, the greater of the two slave-trade routes, emerged as an encounter between Brazil and the two Portuguese colonies of Mozambique and Angola, where nearly half of all slaves taken during the Transatlantic slave trade embarked (more than 5 million).

The second trade route, north of the equator was triangular in nature. Goods from Europe (including firearms which fuelled African rivalries and created emperors) were destined for African leaders. These leaders delivered slaves from the interior to the coast through conquest, for embarkation from places such as Elmina on the Gold Coast in modern day Ghana and Ouidah on the Slave Coast in today’s Benin. During the second leg of this triangular trade, the human cargo on board and destined for the Americas, travelled through the horrors of the so-called ‘middle passage’ where more than 2 million lost their lives crossing the Atlantic. Once disembarked, the stores of ships were once more filled with slave-produced commodities, which drove the economy of the Americas, for the final leg of their voyage back to the Old Continent.

The transatlantic slave trade changed the face of the Americas. In the wake of the decimation of the indigenous populations, Africans came to make up the majority of the populations of most countries of the Americas during the 16th and early 17th century. It was not until African slaves had built the infrastructures of the Western Hemisphere and the age of sail gave way to steam, that the ‘Great Era of Migration’ of Europeans took place in the mid-19th century, thus allowing Europeans to displace Africans as the largest population to colonise the New World.

The legacy of the transatlantic slave trade is found in faces throughout the Americas, most evidently on the Eastern seaboard, where from Nova Scotia to Terra del Fuego, African descendents make up large segments of the population.

The 23rd of August was chosen by UNESCO as this date of Remembrance in honor of a 1791 slave revolt which would ultimately lead to Haitian independence.

Over the last 50 years, there has been much debate over why the United Kingdom moved in 1807 from being the largest slaving nation (at this point in time, every second slave destined for the New World was transported on British flagged ships) to abolishing the slave-trade a sea destined for its colonies. That debate (Williams vs Drescher) had originally focused on abolition having transpired for moral reasons vs economic reasons. The former focused on internal politics in England and the rise of the abolitionist movement. The latter focused on British foreign policy after its loss of the United States of America and its new found dominance of the seas after Trafalgar.

Yet over the last decade or so the debate has gained a new voice: that of the slaves themselves and their role through rebellion and resistance. Slavery became less tenable in the Age of Revolution, especially as the French Declaration of the Rights of Man was internalised throughout the Americas.

Slavery did not start with the transatlantic slave trade, nor did it stop with its abolition.

Today we recognise, in law, that slavery can transpire even when laws allowing for it have long been abolished. Yet just as the outlawing of torture does not mean that torture has disappeared, so too has there been a recognition that slavery remains part of the fabric of our contemporary societies. Nowhere is this more evident that in the United Kingdom, where in 1772 it was declared that Britain was ”a soil whose air is deemed too pure for slaves to breathe in it,” only to find itself legislating in 2009 to in fact criminalise slavery.

While it is often thought that owning a person was fundamental to slavery, the research of late has shown that not only were people enslaved without legal ownership at the fringes of slave societies throughout the Americas. The legal definition of slavery established nearly 90 years ago in an era when legal ownership was still possible, is actually resilient enough to be used today, as it has been, to prosecute people in various parts of the world for contemporary cases of enslavement.

Jean Allain is Professor of Public International Law, Queen’s University Belfast, and an Extraordinary Professor, Centre for Human Rights, Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria, South Africa. He is author of Slavery in International Law and editor of The Legal Understanding of Slavery.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in Public International Law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Triangular trade between western Europe, Africa and Americas by Sémhur. GNU Free Documentation License via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Remembering the slave trade appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWho were the Carlisle Commissioners? Part two: Jeremy BenthamJust who are humanitarian workers?The black quest for justice and innocence

Related StoriesWho were the Carlisle Commissioners? Part two: Jeremy BenthamJust who are humanitarian workers?The black quest for justice and innocence

Zeroing in on zero-hours work

By Stephen Fineman

The growth of zero-hours work contracts has grabbed the headlines recently. The contracts offer no guaranteed work hours and can swing between feast (over work) and famine (literally nil hours). Employees are expected to be available as and when needed. If they refuse (which in principle they can) they risk being labelled as unreliable and overlooked the next time round.

No fixed hours means no fixed pay, and traditional benefits, such as holiday entitlements and sickness pay, can be minimal or non-existent. Zero-hours contracts have been a mainstay of the low paid service industry (McDonald’s has admitted to hiring all but a tiny proportion of its staff on that basis), and are common to social care, hotels, retail outlets, and even UK’s House of Commons and the hallowed confines of Buckingham Palace.

The status of zero-hours sharply divides commentators — political and academic — broadly along left wing/right wing lines. Three perspectives are discernible:

Zero-hours are exploitative. They place undue power in the hands of the employer to do almost what they like with employees, providing them with little security or work predictability. It’s turning back the clock on workers’ rights.

Zero-hours are a manifestation of the 21st century patterns of work flexibility. They suit many people’s lifestyles and are a lot better than being unemployed.

Concern about zero-hours is a distraction. They are a symptom of an economy adjusting to a recession and to little or no growth. Fix the economy and zero-hours will wither on the vine.

These contentions contain a degree of truth and degree of fallacy. There are employers who take advantage of a large pool of unemployed; the work-desperate are at their disposal. Zero-hours contracts help an employer slim their overheads and extract, in Marxian terms, more surplus-value from a large reserve of labour. Anecdotally, we know this can be oppressive to workers. They are unsure about what they will earn in a week, yet still have regular bills to pay (banks regard them as not credit worthy). They cannot risk absence for illness or to care for others in case it is used against them. Some feel treated like dirt.

Zero-hours endanger the hard won rights of organized labour, so it is not surprising that unions are unnerved at the prospect. It is offensive. But zero-hours without the ‘contract’ word attached to it has long been the fate of low-skilled and migrant labour at the margins of Western capitalism, and far less marginal in parts of the world where the jobless gather each morning on street corners, by shipyards, and in front of factory gates in the hope that today they will be chosen for work.

The difficulty for Western societies is when zero-hours looks as if they are going mainstream, and here the evidence suggests that it is increasing but is proportionately small. However, small numbers do not blunt the moral case against major employers who use zero-hours as vehicles of convenience to increase already substantial profits on the backs of a vulnerable workforce. The situation seems different for small and medium sized enterprises that, without zero-hours, or some variant on them, would probably go bust. I am thinking here of the small workshop, the restaurant, bar, garden centre, plumbers, builders, or seaside accommodation where seasonal and weekly fluctuations in business make planning very difficult.

Flexibility has become the mantra of the postmodern workplace and is often positively coupled with zero-hours. But flexible for whom? For instance, zero-hours are concentrated in the social care sector, but they undermine the continuity and familiarity that clients crave, and that care workers consider vital. The unpredictably of zero-hours – sporadic, irregular work — is challenging for families dependent on a single income or for single parents trying to juggle child care work. As one zero-hourer explained, “A job is better than no job, but not to know if you are working when you wake up is much sadder.” On the other hand, there are workers who are untroubled by zero-hours. They fit comfortably with their lifestyles, such as students dovetailing paid work with their studies and retirees adding extra income and activity to their later years

It is a comforting but naive assertion that that zero-hours are no more an unfortunate spike on the economic landscape, and when markets pick up zero-hours will fade. The very existence of zero-hours seeds worker disaffection and distrust and adds to consumer lack of confidence. Zero-hours contracts have become part of the recovery problem, not simply a symptom of it. And I suspect that now the zero-hours’ genie is out of the bottle, it is not easily reinserted; it serves too well some business interests. Zero hour on zero-hours is some way off.

Stephen Fineman is Professor Emeritus at the School of Management, University of Bath, UK and the author of Work: A Very Short Introduction. He has a long and distinguished reputation in the field of organizational behaviour, publishing specialized monographs, edited books and textbooks, all directly or indirectly concerned with the world of work.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to OUPblog only Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS

Subscribe to on Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) By Mimi-chan (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons; (2) By Spc. William J. Taylor [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Zeroing in on zero-hours work appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFive important facts about the Russian economyChallenges of the social life of languageSpain’s unemployment conundrum

Related StoriesFive important facts about the Russian economyChallenges of the social life of languageSpain’s unemployment conundrum

August 22, 2013

Religious displays and the gray area between church and state

This August marks the 10-year anniversary of Alabama Chief Justice Roy Moore’s suspension for refusing to comply with a federal court order to remove a display of the Ten Commandments from the Alabama Supreme Court building. Judge Moore, rather famously, erected the statue in the middle of the night and created a controversy that stirred up emotions about what role religion should play in our public spaces. Since Judge Moore’s stealth attempt to insert the Ten Commandments into the hallowed halls of the Alabama Supreme Court building, the US Supreme court has attempted to determine when a religious display is constitutional, and when is it not.

The first time the Supreme Court addressed the issue of religious displays was in 1980 when Kentucky installed the Ten Commandments in public school classrooms. They ruled that this type of display was indeed unconstitutional and violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment, which states that government shall make no law establishing, or favoring one religion over the other. Since this decision the rulings by both the Supreme Court and the lower courts has been unpredictable and varied. For example, in 2005 the Supreme Court ruled that a 40 year old Ten Commandments display in Texas was constitutional, but a similar newer display in Kentucky was not.

As in the Texas and Kentucky cases, much of the reasoning behind these decisions has rested on the idea of whether or not a display could be considered historical. So far the conclusion the Supreme Court seems to have come to is—if the religious display has been there for a long time then it’s fine to stay, but if it is not a historical object that has been there a long time, then this type of display in public places is unconstitutional. In short, if it’s covered with dust and set-up by your great-grandfather it can stay. If you put it up in a public space as a political and religious statement knowing that these objects are now seen as overtly religious, you will probably be taking it down.

So the tricky part is, what makes a display historical in the eyes of the Supreme Court? This uncertainty in how the law can be interpreted, along with the religious ideology that influences the decisions made by many elected officials, has meant that the controversy surrounding these objects lives on, along with the attempts to put up new displays. In fact, at the state level there has been a great deal of largely unnoticed legislation governing these types of displays, as well as other state laws that attempt to breach church/state separation. The passage of 33 state-level laws providing overt support for displays of religious symbols in public settings between 1995-2009, is simply one component of a larger trend in which there has been increasing passage of what we refer to as “religious inclusion legislation”. The passage of these types of laws, as well as new displays put up by state officials, might not be such a surprise when one realizes that most people support such displays. Two different Pew Center studies conducted in 2005 found that 83% of Americans said displays of Christmas symbols should be allowed on government property and 74% of Americans said they believe it is proper to display the Ten Commandments in government buildings.

In an analysis examining which states passed more religious inclusion legislation during 1995-2009, we found that states with more conservative state legislators, larger proportions of evangelical congregations, and a stronger influence of the Christian Right in state Republican Parties were more likely to pass legislation increasing the inclusion of religious considerations and practices into public life. Such legislation seeks to test the limits of church-state separation or intentionally seeks to fashion a new regime of closer church-state interaction. These polices represent the successes achieved by a resurgent conservative evangelical movement whose ultimate goal is to create a new regime of church state relations in which the government may play a role in promoting or facilitating religious expression. This specific conception of the role of religion in public life is very different from the separation that many currently view as a core American principle.

While these analyses only cover up to the year 2009, attention to such issues has become increasingly important following the massive increase in both the proportion of Republican state legislators and the number of state houses under Republican control following the 2010 Republican wave election. These new laws mean that the issue of religious displays will not disappear anytime soon. In fact, the numbers and types of displays are likely to increase over time, ensuring that the battle over the proper interpretation of the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause will continue.

Rebecca Sager, Keith Gunnar Bentele, Gary Adler, and Sarah A. Soule are co-authors of “Breaking Down the Wall Between Church and State: State Adoption of Religious Inclusion Legislation, 1995-2009” (available to read for free for a limited time) in the Journal of Church and State. Rebecca Sager is an Associate Professor of Sociology at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. Professor Sager’s research focuses on the intersection of religion, policy, and social movements. She has published several pieces on the Faith-Based Initiative and church/state issues in various research journals including the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion and Non-Profit Voluntary Sector Quarterly, and most recently her book, Faith, Politics, and Power: The Politics of Faith-Based Initiatives examined early state implementation. Keith Gunnar Bentele is an assistant professor of Sociology at the University of Massachusetts Boston who studies public policy and inequality. Much of his research examines the factors shaping policy outcomes in US state legislatures, with particular attention to the influences of social movements and political ideology. In particular, he has focused on the consequences of welfare reform, rising earnings inequality in the U.S., and the passage of multiple types of state legislation sought by the conservative Evangelical movement.

The Journal of Church and State seeks to stimulate interest, dialogue, research, and publication in the broad area of religion and the state. JCS publishes constitutional, historical, philosophical, theological, and sociological studies on religion and the body politic in various countries and cultures of the world, including the United States.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: A controversial tablet displaying the Ten Commandments, located on the grounds of the Texas State Capitol (behind the capitol building) in Austin, Texas, USA. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Religious displays and the gray area between church and state appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFamily values and immigration reformUNDRIP, CANZUS, and indigenous rightsAssembling a coherent picture in the Daniel Pelka case

Related StoriesFamily values and immigration reformUNDRIP, CANZUS, and indigenous rightsAssembling a coherent picture in the Daniel Pelka case

Five things you didn’t know about Debussy

To mark the anniversary of Debussy’s birth today in 1862, a list of little known facts about the composer.

(1) It was Debussy who blazed the way to modern music in the United States in the early twentieth century, as evidenced by the many commentaries of American music critics. While Debussy’s highly original harmonic language and style brought mixed reactions at the first performances of his opera in Paris, his modernistic musical language and symbolist ideals soon evoked great enthusiasm in the United States. His orchestral music was championed more than that of any other contemporary composer in the early decades of the century by the symphony orchestras of Boston, Chicago, and New York. Debussy himself appreciated the responsiveness to his music in America.

(2) Much of Debussy’s music is pervaded by the imprint of late nineteenth-century Russian music, including that of Tchaikovsky, Mussorgsky, Borodin, and others. This may be attributed generally to the increasing cross-cultural flow during the period of the Franco-Russian alliance in the late nineteenth century, the sonic influence of Tchaikovsky shifting to the Mighty Five by the time of the Paris Exposition universelle of 1889. But Russian music was already evident in France since the 1870s as it drew the attention of Liszt, Saint-Saëns, and a larger generation of musicians.

(3) The vault scene of Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande, his first and only completed opera, and the entire fabric of The Fall of the House of Usher, his last and unfinished opera, are directly influenced by the macabre world of American poet Edgar Allan Poe. His obsession with Poe was to become increasingly evident after 1908, when he abandoned other compositions for work on Usher. Although he dwelled on the gruesome world of Poe for most of the last decade of his life, it is striking that he could not complete the opera by the time of his death in 1918 for reasons apparently related to personal, practical, and musico-dramatic issues.

(4) Although Debussy was a central figure associated with Impressionist music, he himself vehemently rejected the term as applied to his own compositions, saying: “I am trying to do ‘something different’ — in a way realities — what the imbeciles call ‘impressionism’ is a term which is as poorly used as possible, particularly by art critics.” Although he was contemptuous of those who applied the term to his music, he himself invoked it at a later date.

(5) Debussy was plagued by a lack of money, a recurrent theme throughout his correspondence that raises questions regarding the reception and recompense for his compositions. It is certain, however, that when he had opportunities for official positions other than composing, such as conducting or teaching, he turned them down.

Elliott Antokoletz, Professor of Musicology at the University of Texas at Austin, has held two Endowed Professorships. Elliott Antokoletz and Marianne Wheeldon are the editors of Rethinking Debussy.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Claude Debussy au piano l’été 1893 dans la maison de Luzancy (chez son ami Ernest Chausson). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Five things you didn’t know about Debussy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe 1812 Overture: an attempted narrationAre HD broadcasts “cannibalizing” the Metropolitan Opera’s live audiences?A quiz on the history of sandwiches

Related StoriesThe 1812 Overture: an attempted narrationAre HD broadcasts “cannibalizing” the Metropolitan Opera’s live audiences?A quiz on the history of sandwiches

Ten ways to use a bibliography

What is a student to do with a list of citations? Are an author’s sources merely proof or can they be something more? We often discuss the challenges of the research process with students, scholars, and librarians, and we’ve come to the conclusion that a good bibliography can help in the following ten ways.

(1) Make research more efficient.

How do you begin your research journey? In a world of plentiful information, it can sometimes be too much; we need to cull Rotten Tomatoes reviews from our search while seeking journal articles on Hitchcock’s work. Bibliographies allow us to follow a thread to locate what we’re really seeking.

(2) Separate reliable, peer-reviewed sources from the unreliable or out-of-date.

Sometimes students assume that something in print must be true, when the opposite could in fact be the case. A peer-reviewed bibliography assures researchers that the information they find in those sources is held to the highest standard by experts in the field.

(3) Establish classic, foundational works in a field.

Current academic debate is often shaped over many years, with specific works framing the discussion. For an informed analysis of a subject area, it is often essential that a select number of specific works be consulted and understood.

(4) Provide a guide for independent study.

What questions are scholars asking? What sources are they reading? Bibliographies provide crucial information which can direct independent research.

(5) Structure a class syllabus.

Syllabi often present a challenge for new professors, as does the task of creating a new course. Comprehension of the area of study and critical works is vital.

(6) Create a course reading and supplemental reading list.

Can you point students to the right resources? A strong bibliography will enable this.

(7) Assist with student advisory.

Many professors have the experience of feeding the right monographs and articles to students in order to get them on the right research track from the start.

(8) Help with collection development.

Just as universities expand and create new programs or departments, university libraries must adapt with them. Bibliographies can offer assistance for developing collections in these new areas.

(9) Support research advisory.

Librarians often advise students on how and where to start their research. Librarians can use bibliographies of scholars they know and trust to help inform the process.

(10) Stimulate ideas for events and displays.

Libraries and institutions often highlight specific works to encourage students and scholars to use various resources. Bibliographies around a theme can provide a leg-up in this process.

Alice Northover is a Social Media Manager at Oxford University Press. She is editor of the OUPblog, constant tweeter @OUPAcademic, daily Facebooker at Oxford Academic, and Google Plus updater of Oxford Academic, amongst other things.

Developed cooperatively with scholars and librarians worldwide, Oxford Bibliographies offers exclusive, authoritative research guides. Combining the best features of an annotated bibliography and a high-level encyclopedia, this cutting-edge resource guides researchers to the best available scholarship across a wide variety of subjects.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only media articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Ten ways to use a bibliography appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOh! what a lovely conclaveA quiz on the history of sandwichesHappy birthday, Scofield!

Related StoriesOh! what a lovely conclaveA quiz on the history of sandwichesHappy birthday, Scofield!

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers