Oxford University Press's Blog, page 926

July 9, 2013

Lady Chatterley’s Lover and the politics of “variable obscenity”

It’s the most famous own goal in English legal history. In London’s Old Bailey, late in 1960, Penguin Books is being prosecuted for publishing an obscene book – an unexpurgated edition of D. H. Lawrence’s novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover. The prosecution asks the jury whether Lady Chatterley’s Lover was “a book that you would even wish your wife or your servants to read.” Some of the jurors laugh. Three of them are women. Quite a few are manual or retail workers – not the sorts of people who have live-in servants. Mervyn Griffith-Jones, a prosecutor who once secured the conviction of a Nazi propagandist in the Nuremburg trials, has made himself look ridiculous.

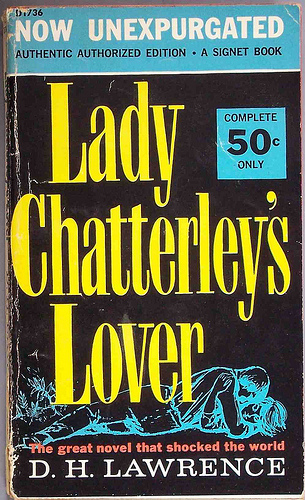

Lady Chatterley’s Lover by D.H. Lawrence. Photo by Chris Drumm, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

Everyone who writes about this landmark case quotes Griffith-Jones’s disastrous question to the jury. It’s invoked as a sign of how out of touch the British Establishment was. Clearly, Griffith-Jones was out of touch with the Britain of 1960. But there was something more interesting than fogeyism going on here.

Griffith-Jones’s question reflected what had long been a convention of English obscenity law. A sexually frank book might be acceptable in an expensive limited edition, but it would not be acceptable if it was produced for a mass market. This principle has been called “variable obscenity.” Of course, censors still assume that younger readers and viewers need special protection and restrict access accordingly. What’s intriguing about the history of English obscenity law is the way gender and social class figured in the judgments that the police and the courts made about who could be trusted to read what.

In the late nineteenth century, companies that published translations of salacious French novels in cheap editions within the reach of working people risked prosecution, but authorities could turn a blind eye to lavish editions that were beyond the means of “the ordinary English public.” Here the law embodied a Victorian assumption that the qualities gathered under the umbrella terms “character” and “self-government” could be indexed to social position. This thinking was crucial in debates about the franchise from the 1850s onwards. Which working-class men were responsible enough to be entrusted with the vote? The various answers to this question involved using tax status as a proxy for patriarchal qualities. So when Griffith-Jones asked jurors whether they would trust their wives or servants with Lady Chatterley’s Lover, he was not just expressing an old-fashioned social and moral code: he was working with a Victorian conception of citizenship.

Those ideas had long since become untenable in other reaches of British culture. After every adult was enfranchised in the decade following World War I, it became a liability for an elected politician to cast doubt on the mental or moral capacity of all women or working-class people. These social judgments were kept alive in obscenity law not just by the paternalism of senior lawyers but also by the routines of policing and the circular force of reasoning from precedent. An informal legal doctrine was able to stay constant even in the midst of social change.

The Lady Chatterley’s Lover trial fatally discredited variable obscenity. The new Obscene Publications Act, passed the year before the trial, enabled the defense to call witnesses with Establishment authority of their own. The 1959 legislation had not been drafted to put an end to variable obscenity, but its expert-testimony provisions opened up a space where the social assumptions of the law could be exposed to challenge. Cultural change often happens this way. Social trends can be enveloping without being pervasive, and it can be through a change in some localized practice or procedure that they make their impact on the law — or literature, or education, or another cultural structure with its own conventions and procedures.

Griffith-Jones’s overreach, too, played a part in the democratization of English obscenity law. Penguin’s counsel, Gerald Gardiner, had been briefed to minimize arguments about class differences, but in his closing statement he confronted Griffith-Jones’s question head-on: “I cannot help thinking this was, consciously or unconsciously, an echo from an observation which had fallen from the bench in an earlier case: ‘It would never do to let members of the working class read this.’” This “whole attitude,” Gardiner said, was “one which Penguin Books was formed to fight against … this attitude that it is all right to publish a special edition at five or ten guineas, so that people who are less well off cannot read what other people do. Is not everybody, whether they are in effect earning £10 a week or £20 a week, equally interested in the society in which we live, in the problems of human relationship, including sexual relationship? In view of the reference made to wives, are not women equally interested in human relations, including sexual relationships?”

Christopher Hilliard is an associate professor of history at the University of Sydney. he is the author of “‘Is It a Book That You Would Even Wish Your Wife or Your Servants to Read?’ Obscenity Law and the Politics of Reading in Modern England” in The American Historical Review, which is available to read for free for a limited time. He is the author of English as a Vocation: The ‘Scrutiny’ Movement (Oxford University Press, 2012), and To Exercise Our Talents: The Democratization of Writing in Britain (Harvard University Press, 2006), which is about ordinary people becoming creative writers in the twentieth century.

The American Historical Review (AHR) is the official publication of the American Historical Association (AHA). The AHR has been the journal of record for the historical profession in the United States since 1895—the only journal that brings together scholarship from every major field of historical study. The AHR is unparalleled in its efforts to choose articles that are new in content and interpretation and that make a contribution to historical knowledge.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Lady Chatterley’s Lover and the politics of “variable obscenity” appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThinking through comedy from Fey to FeoBeware of gifts near elections: Cyprus and the EurozoneGoogle: the unique case of the monopolistic search engine

Related StoriesThinking through comedy from Fey to FeoBeware of gifts near elections: Cyprus and the EurozoneGoogle: the unique case of the monopolistic search engine

Thinking through comedy from Fey to Feo

Comedy is having a bit of a cultural moment. Everywhere you turn people seem to be writing seriously about comedians and the art of comedy. Tina Fey and Caitlin Moran are credited with setting the agenda for pop feminism, Marc Maron is hailed as a pioneer of new media journalism, Louis CK is mentioned in the same breath as Truffaut, and Tig Notaro is regarded as an “icon” for speaking honestly about disease, grief, and resilience. Aristotle famously said that comedy is the “imitation of inferior persons” and tragedy the “imitation of an action that is serious.” We seem to be living in a world upside down: comedians are the sage dispensers of human wisdom; tragedians are fodder for tabloid journalism.

Could it be that these are exceptional times? Has some new species of comedian sprouted from the lowly sod of the comic earth? I am skeptical. New media has allowed us, in some ways for the first time, to listen in as comedians and humourists talk about their craft. The care, hard work, and thoughtfulness with which they go about their work are impressive. (See Marc Maron’s intimate podcast interviews, or video of Jerry Seinfeld explaining his writing process, via the New York Times.) But if we look closely I think it’s clear that in essence comedy has always been a serious thing.

For early modern scholars — and particularly for music historians — the task of uncovering the inner workings of comedies that haven’t been performed in over 200 years is sometimes a difficult one. Librettists and composers rarely recorded their thoughts about such works (at least in media that survive). Critics and scholars did. But what they had to say about comedy was often less than flattering.

Italian theatre scholars were particularly savage. Ludovico Antonio Muratori, for one, remarked in 1706 that comedy “has put itself in the grip of those who do not know how to make us laugh — not with their harmful words and not with indecent misunderstandings and ideas that are foolish, worthless, and shameful” (si è la Commedia data in preda a chi non sa farci ridere, se non con isconci motti, con disonesti equivochi, e con invenzioni sciocche, ridicole, e vergognose).

Many librettists agreed and expurgated comedy from opera around the turn of the eighteenth century. However, the comic impulse could not be suppressed. The very same year that Muratori published his scathing critique musical comedy re-emerged in the form of the comic intermezzo — a short work performed in between the acts of a serious opera. Many of the most popular composers of the day, from Francesco Feo to Johann Adolph Hasse, to Leonardo Vinci, began their careers writing intermezzos.

Thanks to the work of Gordana Lazarevich, Ortrun Landmann, Irène Mamczarz, Michael Talbot, Charles Troy, and others, the history of the intermezzo is well-documented and there are fine performing editions of some works. Intermezzo specialists Kathleen and Peter Van De Graaf have even recreated the phenomenon of the travelling husband-and-wife performance duo. Intermezzo comedy is still very much alive and well for those that seek it out.

Frontispiece and titlepage from a 1688 edition of “Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme”, or “The Middle-class Nobleman”, by Moliere.

A few years ago the Vinci scholar Kurt Markstrom generously shared with me the libretto and score for the intermezzo Albino e Plautilla da pedante. This isn’t the sort of work that you’ll read about in a general history of music. It was performed in Naples in the fall of 1723, after which it was consigned to the archive shelf. Reading through the words and notes I found myself laughing at a scene that seemed oddly familiar. The ambitious but uncouth Albino was getting a lesson in the pronunciation of vowels from his female servant disguised as a philosopher. Molière! Monsieur Jourdain received the same lesson in Il Bourgeois Gentilhomme (1670).

These kinds of discoveries have a way of sending you on unexpected adventures. As I dug further it became clear that this silly lesson was inextricably bound up with the New Philosophy of Descartes and perhaps its promotion in Naples by Giuseppa Eleonora Barbapiccola. French plays, Cartesian treatises, female philosophers — Albino was a musical farce that seemed to tackle some remarkably weighty subject matter. How many other intermezzos might touch upon a raw cultural nerve?

When it comes to comic works of the present we eagerly seek the deeper truth behind the punch line. But when it comes to works of the past we too often look only for earnestness in drama and hilarity in comedy. As Man Booker-winner Howard Jacobson points out, “we have created a false division between laughter and thought, between comedy and seriousness.”

Studying the humour of the comic intermezzo has made me a believer. Comedy at its best, regardless of when it was written, provides keen insight into the convictions, insecurities, terrors, and joys of its moment in time. And musical comedy in particular can communicate the nuance of experience in immediate and affecting ways. In short, the intermezzo has the potential to be a better record of history than any diary or treatise. Early modern comedy is perhaps an imitation of inferior persons, but surely also a keeper of profound truth.

Keith Johnston is Visiting Assistant Professor of Music History and Theory at Stony Brook University. He principally investigates comedy in Italian operas of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. His research explores two complementary aspects of comic theatre: the shared compositional structures that underpin musical, written, and improvised material; and the cultural, philosophical, and political forces that shaped the selection and adaptation of that material. His article in Music & Letters — “Molière, Descartes, and the Practice of Comedy in the Intermezzo” — is available to read for free for a limited time.

Music & Letters is a leading international journal of musical scholarship, publishing articles on topics ranging from antiquity to the present day and embracing musics from classical, popular, and world traditions. Since its foundation in the 1920s, Music & Letters has especially encouraged fruitful dialogue between musicology and other disciplines.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Frontispiece and titlepage from a 1688 edition of “Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme”, “The Middle-class Nobleman”, by Moliere., 1688. From the Private Collection of S. Whitehead. Moliere and Henri Wetstein. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Thinking through comedy from Fey to Feo appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesUniversity as a portfolio investment: part-time work isn’t just about beer moneyThe search for ‘folk music’ in art musicMusical scores and female detectives of the 1940s

Related StoriesUniversity as a portfolio investment: part-time work isn’t just about beer moneyThe search for ‘folk music’ in art musicMusical scores and female detectives of the 1940s

July 8, 2013

Creativity in the social sciences

The question of how social scientists choose the topics they write about doesn’t agitate inquiring minds as the puzzle of what drives creative writers and artists does.

Many innovative social scientists take up the same subjects again and again, and their obsessiveness is probably indicative of considerations and compulsions more powerful than increasing ease with a familiar field of inquiry. They are specialists who have fallen in love with their subjects, rather like artists were thought to become impassioned with their models in the days of High Romanticism.

Some topics look trendier, more pressing, and perhaps more fundable on the face of it. This happened during the Vietnam War with revolutions, cast as “agrarian rebellions.” A similarly topical logic stirred up interest in religious movements with the almost wholly unanticipated Iranian revolution and the gradual but no less surprising emergence of religious fundamentalism and its intrusion into politics after the tumultuous sixties. Moreover, embedded in the surprise of such events is an incentive to question the structure of presuppositions that leads observers to overlook impending change in the first place. Challenging conventional wisdom is not a bad way to get the creative juices flowing.

The beautiful and inspiring interior of the Durham Cathedral in England.

In the case of religious studies in the social sciences, secularization theory encapsulated this old way of thinking. Boiled down, the idea was that with modernization—urbanization, education, media exposure, and so on—belief in the miraculous would wither away. Reality stridently contradicted this paradigm. However, the claim has started to make a comeback in part because the number of Americans who vouchsafe neither religious affiliation nor belief in God has grown. Admittedly, the depiction of implacable modernization as the advent of sweet reason is something of a straw man, so sophisticated versions of contingent, polymorphic secularization have gained ground.At the same time there is a respectable case to be made for framing totalitarian mobilization and control as fill-ins for the hope and security once provided by traditional religions. The argument makes some sense for Nazi Germany and perhaps Soviet Russia but less so, or in less transparent ways, for revolutionary China. The larger lesson is that single factor explanations of social phenomena are almost always tendentious by their very nature. Grand theory has become suspect. Sweeping narratives, like super-sized sodas, are bad for you.

In the end there are good reasons why no one loses much sleep over why social scientists working in religion fix on certain topics and what makes some such enterprises more creative than others. Both questions have a self-referential, insider-gossip air to them.

The more important question is what drives religious creativity and spiritual genius itself. Everyone who has taken Sociology 101 remembers Max Weber’s ideas about the metamorphosis from charismatic to bureaucratic leadership that religious organizations follow. The trajectory goes, comparatively speaking, from moments of madness to sober rationality. Ossification sets in, and it grows on you.

It is remarkable that a century after Weber we have yet to come to terms with the mirror-image question. How do established religions renew themselves? Is it through periodic outbursts of charismatic leadership? Or are other, less cyclical sequences imaginable? How, exactly, can transformative change happen?

This is the question facing Catholicism, in acute form, with the onset of the papacy of Francis—an old hand at institutional maneuvering, among other things.

Peter McDonough has written two books on the Jesuits and others on democratization in Brazil and Spain. His most recent book is The Catholic Labyrinth: Power, Apathy, and a Passion for Reform in the American Church. He lives in Glendale, California.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Photo from Cornell University Library, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Creativity in the social sciences appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesReligious, political, spiritual—something in common after all?Russia’s toughest prisons: what can the Pussy Riot band members expect?An idioms and formulaic language quiz

Related StoriesReligious, political, spiritual—something in common after all?Russia’s toughest prisons: what can the Pussy Riot band members expect?An idioms and formulaic language quiz

What’s really at stake in the National Security Agency data sweeps

As controversy continues over the efforts of the National Security Agency to collect the telephone records of millions of innocent Americans, officials have sought to reassure the public that these programs are permitted by the Constitution, approved by Congress, and overseen by the courts. Yet the reality is that these programs fully deserve the discomfort they have aroused.

To be sure, existing case law gives no Fourth Amendment protection to communications transactions records such as numbers dialed, the length of a call, and other digital transmissions data. This conclusion rests on a 1979 decision (Smith v. Maryland), which ruled that the use of a pen register — a device that records numbers dialed from a telephone – is not a search and that a warrant therefore is not required. The Court held that a pen register did not disturb a “reasonable expectation of privacy,” because the number would be available to the phone company anyway.

Even in 1979, the Smith decision was exceptionally problematic. To treat information conveyed to a trusted intermediary, under promise of confidentiality, as if it had been posted on a public billboard is to make nonsense of the Fourth Amendment. This objection to Smith is not the familiar but difficult one that arises when an old constitutional rule has unexpected new implications. Smith’s notion that shared information should have no Fourth Amendment protection would make as little sense in the eighteenth century world of the Framers as it does in our own because privacy has never been equated with mere secrecy. Privacy is something much more important: the right to control knowledge about our personal lives, the right to decide how much information gets revealed to whom and for which purposes. The religious dissenters who gathered to pray in eighteenth century England and the political dissidents who plotted the American Revolution certainly understood the privacy of shared information. There is no doubt that information about whom we call, how long we talk to them, and when they call us back can produce a deeply revealing picture of our personal activities and associations, even when it contains no details about the content of our conversations.

Only a hermit seeks complete secrecy. For anyone who wishes to inhabit the world, daily life inevitably involves personal associations. Relationships and the information we exchange within them give meaning to our lives and define a large part of who we are. To insist that information is private only when it remains completely secret is therefore preposterous. Indeed, personal information often becomes more valuable when we share it confidentially with chosen associates who help us pursue common projects. The Framers of our Fourth Amendment intended it to nurture and support civic life, not to provide an alternative to it.

If the Supreme Court’s rule denying Fourth Amendment protection to information shared in confidence was shaky in 1979, it is even more so today. Thirty years ago, communication still consisted primarily of hard-copy correspondence through the Postal Service and conversations that occurred in person or by telephone. So in its day, the Smith decision represented only limited incursion on privacy. Because the computer technology of the time afforded little opportunity to store, collate, and analyze the underlying transactions data, the data by itself provided only a limited window into the private lives of individuals.

Today in contrast, email, Facebook, Twitter, and the like — all services facilitated through third parties — have gone far towards displacing first-class mail and the telephone as citizens’ primary means of communication. These programs rely on digital information processed on a server before and during transmission, so they generate an enormous volume of data relating to each communication. Because that data can be stored indefinitely and probed systematically by powerful computers deploying complex algorithms, this digital information now has vastly greater potential for revealing personal details that innocent individuals typically prefer to keep confidential.

Of course, commercial data collection can tell marketing companies quite a bit about our private associations and preferences — an argument for allowing the government to collect and analyze the data too. But the NSA sweeps of communications data are different in two fundamental ways. First, they give the government access to call records that typically are not available to commercial data aggregators. Second, commercial data mining at its worst subjects us only to unwelcome, machine-generated email and phone calls; we are offered products and services we have no desire to buy. This is a nuisance, but the harm is trivial.

The dangers are entirely different when personal information becomes available to the government with its vast power over the lives of individuals. Government officials can deploy computer power that dwarfs anything available in the private sector and if they are looking for patterns that can reveal confidential details, they can learn a great deal about anyone very quickly. Investigators seeking to deter leaks about controversial government programs can use data mining software to ascertain a journalist’s confidential sources. Data mining gives the government access to a citizen’s political and religious beliefs, personal associations, sexual interests, or other matters that can expose the individual to political intimidation, blackmail, or selective prosecution for trivial infractions. Unconstrained government data mining has unique potential to dampen creativity, impoverish social life, and chill the political discussion and association that are essential pillars of our democracy.

For many Americans, unfortunately, all this is beside the point because fear of terrorism prompts them to value their safety from attack over the resulting loss of civil liberties. This notion of an inherent “trade-off” between the two is profoundly misleading. Decisions to sacrifice privacy can easily divert attention and energy from better ways to prevent attacks — for example, hiring more agents who understand foreign languages or investing in the protection of our ports and chemical plants.

The supposed liberty-security trade-off is misleading for a second and more fundamental reason, one that goes to the heart of the Fourth Amendment. In debates over strong surveillance powers, proponents and skeptics alike typically assume that the Fourth Amendment, if allowed to apply, will create an impenetrable wall of protection for any information we decide to consider “private.” This assumption is widely held but completely inaccurate. The Fourth Amendment never places information entirely beyond the government’s reach; its point is only to regulate surveillance, in order to assure accountability. The most intimate areas of our homes can be searched, provided that investigators can demonstrate probable cause for a judicial warrant. Other, less intrusive searches are allowed under more permissive standards, but provided again that investigating police and prosecutors remain subject to oversight.

As a result, the claim that we must opt for more privacy or more security presents a false choice. The relevant alternatives are surveillance with oversight or surveillance without. Our Fourth Amendment history makes clear that the latter option, though inevitably preferred by officials guarding their freedom of action, always leads to abuse — unnecessary abuse because the same public safety objectives typically could have been achieved simply by putting in place reasonable independent systems to assure accountability.

Thus, the debate over NSA data sweeps has largely sidestepped the one issue that should be straightforward and uncontroversial: the need for effective, independent Congressional and judicial oversight. Although President Obama and his administration have spoken repeatedly of Congressional briefings and authorization by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance (FISA) Court, the reality is that the NSA program faces few independent checks. The FISA court is required to approve data collection requests for any “authorized investigation,” and its opinions explaining what this crucial term means are classified “top secret.” Some members of Congress are briefed, but only in vague terms, in secret sessions that are closed even to the staff they need for help on these complex issues. Barring a sensational (and illegal) leak that brings the matter to public attention, political realities ensure that Congress will remain powerless on the sidelines.

The NSA data sweeps therefore may satisfy the letter of the law, but they are profoundly at odds with the spirit of the Fourth Amendment because genuine checks and balances are almost entirely absent. As government powers of this sort expand, the sheltered spaces we need for personal autonomy and political freedom gradually disappear.

Fidelity to our Fourth Amendment tradition demands that the FISA court have the authority to verify the basis for the surveillance measures it is asked to approve and that it have the obligation to make its key legal rulings available, so that the public can know what kinds of powers it has given its government. Finally, Congress must be briefed in ways that encourage rather than impede its involvement.

These Fourth Amendment oversight practices can give national security officials the authority they need while at the same time building confidence that powerful surveillance tools will not put at risk the freedoms that are the foundations of our democracy.

Stephen J. Schulhofer is Robert B. McKay Professor of Law at the New York University School of Law. His most recent book, More Essential Than Ever: The Fourth Amendment in the Twenty-first Century, was published by OUP in 2012. His other books include Rethinking the Patriot Act, The Enemy Within, and Unwanted Sex.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: (1) Padlock standing on a black laptop keyboard. © winterling via iStockphoto (2) Stephen J. Schulhofer, courtesy of NYU Photo Bureau/Asselin.

The post What’s really at stake in the National Security Agency data sweeps appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSuspicious young men, then and nowWhat can we learn from the French Revolution?Nelson Mandela: a precursor to Barack Obama

Related StoriesSuspicious young men, then and nowWhat can we learn from the French Revolution?Nelson Mandela: a precursor to Barack Obama

On suicide prevention

Each year about a million people worldwide die by suicide and an unknown number, estimated at 10 to 20 times that, engage in some form or other of life-threatening behavior. As a result, strong feelings are usually evoked in others, particularly in family and close friends.

Psychiatric practice for over 40 years has not made me immune to such feelings. As a newly graduated medical intern in 1968, two patients are still indelibly imprinted on my mind. The first was an attractive young woman with brain damage, the result of carbon monoxide poisoning following a break up with her boyfriend. Sadly, there was no hope of improvement. The other was an elderly man admitted with severe pneumonia, which when treated revealed a profoundly depressed man whose chest infection had arisen after a near fatal overdose. Surprisingly to me at that time, his depression and wish to die responded well to electro-convulsive therapy and follow-up antidepressants.

This spectrum of outcomes is all too familiar to practicing psychiatrists. Sometimes seemingly trivial issues can lead to risk-taking, death, or irreversible injury, and at times we can provide very effective treatment. The only obvious common thread for these two patients was the suicidal behavior — and there’s one of the dilemmas facing those who attempt to understand the enigma of suicide.

It is clear that there are many paths to suicide, a fact sometimes ignored by those who promote either psychosocial or biomedical causes. Such a dichotomy is not only counterproductive to good clinical practice, but it is wrong. Suicide is predominantly related to socio-economic issues in less developed countries and those with repressive political regimes, where there are poorly developed health services and inadequate social service safety nets. However, sophisticated genetic studies in developed countries have confirmed the importance of inherited factors. These are mediated by psychiatric illnesses and the optimum management of these can influence suicide.

This may seem obvious, but it is difficult to prove conclusively because of the low base rate of suicide. What this means is that although when suicide occurs it is dramatic and there may seem to be clear cut precipitants, the dilemma is that those apparent causes lack specificity. Indeed, the numbers needed to demonstrate the effectiveness of any intervention are so great that the conventional gold standard of proof, a randomized controlled trial, is impractical.

This has led to some being pessimistic about our ability to prevent suicide. However, the astute investor is aware of other investments beside gold, and there are alternative research methodologies which have convincingly demonstrated the effectiveness of suicide prevention measures. Population-based pharmaco-epidemiological studies have shown a reduction in suicide in association with increasing uptake of certain antidepressants; there is persuasive evidence for the protective effect of lithium in bipolar disorders; and recent large community studies in England have demonstrated that when a health service implements recommendations such as the provision of 24-hour crisis care, specific treatment policies for those with dual diagnoses, and multi-disciplinary reviews when suicide does occur, there is a significant fall in suicide compared to areas where such initiatives are not undertaken. Other measures such as more appropriate media reporting of suicide and prevention of access to jumping sites, firearms, or potentially lethal pesticides are also effective.

None of this is rocket science. However, some measures require persistent advocacy and political legislation, which can be frustrating to clinicians used to routinely introducing evidence-based practice. While this broad approach may be necessary, particularly in developing countries, it is important that the individual person’s distress is addressed and has the potential benefit of optimum treatment, whatever psychiatric illness may be present . Unfortunately two large studies from the UK and Australia have shown that at least 20% of suicides after contact with psychiatric services could have been prevented, if it were not for issues of inadequate assessment and treatment and poor staff communication. Long personal experience of coroner enquiries certainly confirms that.

Not all suicide can be prevented. That is particularly so when help is not sought. On other occasions suicide can be interpreted as the inevitable outcome of a malignant mental disorder, and that can be of some comfort to grieving families and friends who may be feeling guilty at their sense of relief that uncertainty is over. Clinicians may also share those emotions. However, if adequate assessment of each individual is undertaken and appropriate management pursued, on balance there will be an overall reduction in the unacceptable rate of suicide worldwide.

Robert Goldney AO, MD is the author of Suicide Prevention (Second Edition, OUP, 2013). He is Emeritus Professor in the Discipline of Psychiatry at the University of Adelaide. He has researched and published in the field of suicidal behaviors for 40 years and has been President of both the International Association for Suicide Prevention and the International Academy of Suicide Research.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology and neuroscience articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Autumn in Nymphenburg via iStockPhoto.

The post On suicide prevention appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAnaesthesia exposure and the developing brain: to be or not to be?DSM-5 and psychiatric progressBeyond narcissism and evil: The decision to use chemical weapons

Related StoriesAnaesthesia exposure and the developing brain: to be or not to be?DSM-5 and psychiatric progressBeyond narcissism and evil: The decision to use chemical weapons

July 7, 2013

Beyond narcissism and evil: The decision to use chemical weapons

With all eyes on chemical and nuclear weapons in the Middle East, it might seem natural to speculate about the ethical and moral positions of world leaders, or even to apply psychological analyses to them. We ask ourselves whether the Iranian leaders are psychotic enough to attack Israel with nuclear weapons, or we wonder which of the Syrian leaders would be monstrous enough to use chemical weapons. After all, Saddam Hussein allegedly was a malignant narcissist, incapable of empathy, and proved it by using chemical weapons “against his own people,” a phrase that returned to public discourse when Secretary of State John Kerry used it to describe Syrian president Bashar al-Assad’s similar actions in Syria. These inquiries often end up with some permutation of the question, “who would do such a thing?”

We are so tied up in the rhetoric of evil and narcissism that we cannot see straight. The Soviet Union was Ronald Reagan’s so-called evil empire, and Iraq, Iran, and North Korea were parts of George W. Bush’s “axis of evil.” Saddam Hussein, Hitler, Stalin — actions by all of these people are explained away by saying their mental health was in question. You can Google “malignant narcissism” with either “George W. Bush” or “Barack Obama” and get plenty of hits too. It will come as no surprise that Iranian and Syrian leaders are currently being perceived as malignant narcissists.

Using such language may be politically useful, but scholars, policymakers, and thinking people everywhere need to avoid drinking the Kool-Aid. We will never solve the problems associated with war atrocities by managing the psychological profiles of world leaders. We can only do so by assessing the causes of conflict and trying to address them.

When trying to imagine why world leaders might use something as terrible as chemical weapons, we should leave morality out of it and start with two simple questions. First, do they think it would serve their interests? And second, equally important, do they think they can get away with it? You can add psychology and notions of good and evil on top of that if you must, but only after the basic questions have been answered.

An English gas bomb from World War I, 1915. Private collection of Christoph Herrmann. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

In case anyone is tempted to say that democracy has something to do with it, let me point out that the United States pioneered—as in, led the way—in research and manufacture of biological weapons in the early Cold War era. Why? Because American military leaders believed that they were going to fight another world war with the Soviet Union sometime in the near future. Neither the US Department of Defense nor the US Joint Chiefs of Staff perceived such weapons as morally outrageous. After all, they had just finished a war with Japan and Germany in which they used statisticians to help strategic bombers maximize human death in cities. Their bombs created firestorms, a term used to describe the rush of air from the uptake of oxygen in flames, creating storm-force winds amidst the inferno. Then they dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. American leaders had already crossed the line toward targeting civilians and committing horrifying deeds in wartime, and they knew it.

The United States developed not only biological, chemical, and nuclear weapons, but they worked on radiological ones (dirty bombs), weather control, crop destruction, and even considered using hydrogen bombs to create tsunamis and raise sea levels. Military leaders figured that the Soviets were doing the same. These ideas seem insane, perhaps even evil, to us now. Ironically, much of this work has informed our own sense of vulnerability to environmental threats, because war planners had to imagine how successful an enemy might be if they used such weapons.

In the case of the United States, the government was armed to the teeth in the most extraordinary weapons during the Cold War and did not use them. Correspondence between the Army, Navy, and Air Force in the early 1950s (during the Korean War) attests that the political cost of using them would simply be too high. Actually the North Koreans and Chinese claimed that the Americans had waged secret biological warfare, but the United States managed that crisis and persuaded most of the world that they hadn’t. The international uproar taught the US government that, had it been true, the political cost would have been exceptionally high. In those days, some politicians said that using atomic bombs in Korea would be just fine. And yet the United States didn’t do it. Not because of goodness or moral righteousness, or psychological soundness, but because the United States could not get away with it.

Since the heyday of biological and chemical weapons research, circa 1940s-1960s, the political winds have shifted so dramatically, and the moral weight of opinion in the United States and the West generally has changed so fully, that we associate these weapons with evil. And maybe they are. But more importantly, politicians and military officers in the United States know that there are almost no situations in which they could get away with using them. In the late 1960s, President Nixon renounced biological weapons, and in the 1970s, the United States even ratified the Geneva Protocol, half a century after signing it in the first place. They didn’t give up on nukes, though, because the political context for retaining such (immoral? psychotic? evil?) weapons was alive and well in the 1970s. Only now, with the Cold War over, is there meaningful discussion about reducing nuclear weapons.

Any person, and any government, is capable of using these horrific weapons. They will not use them if there is a range of better, viable alternatives, and if the court of public opinion matters to them. When we call a government evil or call a leader a psychopath we are not only taking the lazy way out, we are endangering human lives, committing ourselves to a position that ties our hands and theirs at the same time, leaving no room for maneuver or compromise. It encourages the most desperate kinds of actions by leaders who see few paths available to them. We should never put someone who possesses biological and chemical weapons, or a potential for nuclear weapons, into a situation in which he has nothing to lose.

Jacob Darwin Hamblin is an associate professor of history at Oregon State University and is the author of Arming Mother Nature: The Birth of Catastrophic Environmentalism. You can follow him on Twitter @jdhamblin.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Beyond narcissism and evil: The decision to use chemical weapons appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMoralizing states: intervening in SyriaWhat can we learn from the French Revolution?Suspicious young men, then and now

Related StoriesMoralizing states: intervening in SyriaWhat can we learn from the French Revolution?Suspicious young men, then and now

An idioms and formulaic language quiz

On this day in 1928, sliced bread was sold for the first time by the Chillicothe Baking Company of Chillicothe, Missouri. Ever since then, sliced bread has been held up as the ideal — at least in idiomatic expressions. Ever heard of “the greatest thing since sliced bread”? In honor of that fateful day, we’ve compiled a quiz to test your knowledge of some of the most common (and not so common) idioms that have found their way into daily conversation.

But first, what is an idiom? To paraphrase from Oxford Dictionaries Online, it is a common phrase that is understood as something different than the sum of its individual words. Through repeated usage, the meaning of an idiom becomes standardized within a larger audience, making it useful in conversation to quickly and succinctly communicate a sentiment. Take, “it’s raining cats and dogs,” for instance. This is a clichéd example that refers to heavy rain and not animals falling from the sky.

Though many people are quick to disparage idioms as stale, static components of language, Raymond W. Gibbs offers an alternative view in the Oxford Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics. In “Idioms and Formulaic Language,” he argues that one’s language fluency is dependent on mastering such formulaic language. He asserts, “Idiomatic/proverbial phrases are not (emphasis added) mere linguistic ornaments, intended to dress up a person’s speech style, but are an integral part of the language that eases social interaction, enhances textual coherence, and, quite importantly, reflect fundamental patterns of human thought.”

With that in mind, and without further ado, a quiz. Break a leg!

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Native of Southern California, Audrey Ingerson is a marketing intern at Oxford University Press and a rising senior at Amherst College. In addition to swimming and pursuing a double English/Psychology major, she fills her time with an unhealthy addiction to crafting and desserts.

Oxford Handbooks Online brings together the world’s leading scholars to write review essays that evaluate the current thinking on a field or topic, and make an original argument about the future direction of the debate. The Oxford Handbooks are one of the most successful and cited series within scholarly publishing, containing in-depth, high-level articles by scholars at the top of their field and for the first time, the entire collection of work across 14 subject areas is available online.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post An idioms and formulaic language quiz appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhen it rains, it does not necessarily pourMonthly etymological gleanings for June 2013When in Rome, swear as the Romans do

Related StoriesWhen it rains, it does not necessarily pourMonthly etymological gleanings for June 2013When in Rome, swear as the Romans do

July 6, 2013

What can we learn from the French Revolution?

The world has seen a new wave of revolutions; in North Africa, the Middle East, and beyond, we can see revolutions unfolding on our tv screens even if we’ve never been near an actual revolution in our lives. The experience makes us think anew about the nature of revolutions, about what happens, and why it may happen. Revolutions are born out of hope for a better future. People who participate in revolutions do so believing in the possibility that they can transform their circumstances. They may be ready to make immense personal sacrifices, even sometimes their own lives, in the struggle to create a genuine democracy, where government would be an instrument of the people’s will, rather than a source of power and enrichment for a privileged and corrupt elite.

The lion of Egyptian revolution at the Qasr al-Nil Bridge. Photo by Kodak Agfa from Egypt, 2011. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

Yet such a fledgling democracy born out of revolution can be fragile. Its leaders have to learn how to manage the new business of politics, often with very little previous experience. Revolutions are by their very nature unstable and perilous, often beset by internal conflict and outside intervention. State violence and militarism can bring a return to stability, but at a price. Revolutionary leaders who started out as humanitarian idealists, given certain circumstances, may adopt brutal methods; they may choose to use political violence, even terror, either to defend the gains of the revolution or, more cynically, to maintain themselves in power. The quest for liberty and equality can be a disheartening experience.

How does such a transformation from boundless hope to the nightmare of terror come about? Is there any way it can be avoided? One way to reconsider this problem is to look at revolution as a process, and to study how the process of revolution unfolded in previous revolutions. By taking a comparative approach we can throw light on how certain choices made by people in positions of power had particular consequences. Above all, we can consider what kind of circumstances could lead to revolutionary leaders choosing terror.

The French Revolution that broke out 1789 became a model for future revolutions. It was in the course of the French Revolution that the idea of political terror was invented; the words ‘terrorism’ and ‘terrorist’ were coined in late 1794 to describe the regime that had been overthrown the previous July, that of Robespierre and the Jacobins. We should be wary, though, of making simplistic comparisons; the Jacobin version of terror was different in many ways to the modern phenomenon. When we speak of ‘terrorism’ in the modern era we think of anarchic movements directed against the government and innocent bystanders, of bombs, of suicide bombers. The Terror in the French Revolution was different. It was not directed against the government; it was led by the government. It was a legalised terror.

La Liberté guidant le peuple by Eugène Delacroix, 1830. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

So what makes idealistic humanitarian people, choose terror? Too often the French revolutionary leaders have been glibly compared to twentieth-century dictators. The leaders of the French Revolution weren’t all-powerful dictators. Nor were they violent psychopaths. Most of them were genuine idealists, even if they also sought to derive personal advantage from events, by forging a career for themselves in revolutionary politics. They did not set out to become terrorists; it was a path that they took, step by step, making contingent choices along the way.

Political inexperience was a key problem. France had no tradition of representative politics — of the tactics, backroom deals, political image-making — all the rather cynical, sometimes frankly seedy, business that is day-to-day politics. The revolutionaries’ baptism of fire came through transformative politics — the politics of revolution — which they invented even as they practised it. After this tumultuous beginning, they found it hard to establish a stable politics. Revolutionary politics had been constructed in deliberate contrast to the system that had existed under the monarchy: a system that had been opaque, corrupt, venal and self-serving, with power concentrated in the hands of the king and a few powerful court nobles with their ‘behind closed doors’ influence. At the same time the French revolutionaries also rejected the corrupt party politics and cronyism that characterised the English parliament in the 1790s.

Instead, the French revolutionaries were committed to transparent politics. They believed that every national representative should think only of the public good; his public and private life should be an open book, reflecting the purity of his devotion to the patrie. This volatile political birthing process might well have settled down given time. During the early years of the Revolution a constitutional monarchy was established, along with a limited franchise based on property-holding, and to all intents and purposes the Revolution was over.

But a series of factors destabilised the new regime. Chief amongst these was the counter-revolutionary opposition of many leading nobles, who resented their loss of power and prestige; they would never accept the Revolution and did all they could to undermine it. The greatest betrayal of all was that of the king himself who, in June 1791, attempted to flee his country, getting close to the border before he was intercepted and brought back. The onset of war with the major foreign powers in April 1792 put France under increased threat, and ratcheted up the tension, making internal compromise all but impossible. War in turn led directly to the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of the first French Republic. Further betrayals took place as leading generals, Lafayette and later Dumouriez, attempted to turn the French armies on the representative assembly and to overthrow it by force. Suspicion, polarisation and renewed internal conflict were a consequence of such betrayals. A further factor was the anarchic violence of the people on the streets. This violence, and the threat of further popular violence, helped maintain the revolutionary leaders in power, yet the leaders were all too aware that this anarchic violence might at any time be turned on themselves if they failed to deliver.

It was largely in response to popular street violence that in September 1793 the revolutionary leaders set up a legalised system of terror, bringing violence under state control, though they preferred to think of it as justice — the swift and often brutal justice of a wartime government under pressure. Ironically, the revolutionary leaders were hardest on themselves; they too were subject to terror. Many revolutionary leaders were accused — in most cases falsely — of being the ‘enemy within’, secretly in league with the counter-revolutionaries and the foreign invaders to subvert the Revolution for their own benefit, even to destroy it. They had no parliamentary immunity, and were relatively unprotected whether from terror, assassination or any other form of violence that might be used against them. They had no personal defences, no bodyguards, and they were not hidden away behind palace walls. Most lived in lodging houses, hotels and private homes. Robespierre himself lived, not in a palace, but as a lodger in the house of a master carpenter.

In this, as in many other ways, the French revolutionary leaders were unlike Stalin and other twentieth-century dictators. In the Year II many of the leading revolutionaries fell victim to the Terror that they had helped to set up. The revolutionary leaders were afraid and with good reason. They were desperate to show their own integrity, that they could not be bought by the counter-revolution. And this very fear in its turn made them pitiless with one another. They dealt out terror in part because they too were terrorised. Paradoxically, the Terror emerged partly from the relative weakness of the revolutionary leaders. The Jacobins used coercive violence and the power of fear to subdue their enemies, including opponents from their own ranks, ‘the enemy within’. Terror was motivated less by abstract ideas, than by the gut-wrenching emotion of fear on the part of the people who chose it.

As a Jacobin leader, Robespierre had supported the use of terror. He made some of the key speeches seeking to justify its use in order to sustain the Republic. But he was far from alone, and very far from being the dictator of a Reign of Terror — that was a myth perpetrated by the revolutionaries who overthrew him out of terror for their own lives, not because they wanted to dismantle the Terror. These surviving former terrorists ensured that Robespierre and the group around him took the rap posthumously for the Terror; even whilst they opportunistically reinvented themselves as men who had kept their hands clean.

Robespierre himself remains a complex figure. He was known as ‘the Incorruptible’ — a quality almost as rare in contemporary politics as it was in his lifetime. He was that rare figure, a conviction politician. For nearly thirty years now, since long before I became a professional historian, I have been haunted by a question: what led a man like Robespierre (and others like him) who at the start of the Revolution was a humanitarian opposed to the death penalty, to chose terror four years later? I’m not the first person to ask this question. Many historians have asked it and come up with very different answers. But then historians always disagree with one another, and few people have divided historical opinion as much as Robespierre. Yet two things I do know: firstly that the answer has to be sought not in some warp of Robespierre’s personality, but in the politics of the Revolution itself; and secondly, that in addressing it there is no room for complacency.

To understand the French revolutionaries is to better understand ourselves. We have cause to be grateful that we have not been confronted with such choices, in such circumstances, and with such tragic consequences, as they faced in their own lives.

Marisa Linton is a leading historian of the French Revolution. She is currently Reader in History at Kingston University. She has published widely on eighteenth-century France and the French Revolution. She is the author of Choosing Terror: Virtue, Friendship, and Authenticity in the French Revolution (2013), The Politics of Virtue in Enlightenment France (2001) and the co-editor of Conspiracy in the French Revolution (2007).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post What can we learn from the French Revolution? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSuspicious young men, then and nowNelson Mandela: a precursor to Barack ObamaUS Independence Day author Q&A: part four

Related StoriesSuspicious young men, then and nowNelson Mandela: a precursor to Barack ObamaUS Independence Day author Q&A: part four

An Oxford Companion to Wimbledon

This weekend, Wimbledon will come to an end, looking far different from tennis’s start in the middle ages. Originally played in cloisters by hitting the ball with the palm of a hand, tennis added rackets in the sixteenth century. Lawn tennis emerged in Britain in the 1870s and the first championships took place at Wimbledon in 1877.

Two hundred attendees watched Wimbledon’s inaugural final; this year, the finalists will meet at Centre Court, which can seat 15,000 spectators. At Wimbledon last year, 25,000 bottles of champagne were popped, 28,000 kg of fresh strawberries were devoured, 54,250 tennis balls were hit, and 25,000 Championship’s Towels were sold.

Tennis at Wimbledon (ca. 1922-1939). Image courtesy of the NYPL Digital Gallery.

This year’s finals will be notable for other reasons. So far, the 2013 Wimbledon championships have made one thing startlingly apparent: we’ve reached the end of a tennis era. Rafael Nadal, fresh off his French Open win, lost in the first round to Steve Darcis, ranked 135th. Roger Federer exited shortly after in the second round, leaving a Grand Slam before the quarterfinals for the first time since 2004. Third seeded Maria Sharapova also said her goodbyes after the second round, while Wimbledon-favorite Serena Williams exited in the fourth round.

If this year’s Wimbledon is any indication, the past decade reign of Federer and Nadal, with Djokovic serving as Crown Prince, is coming to an end. So, what comes next? Just as there is always a rising tennis great waiting on the sidelines, history is also waiting to reassert itself while technology is eager to revolutionize the game. If so, here are some trends we can expect, or hope, to see in the coming years:

Tennis cake: an English Victorian cream cake served to accompany lawn tennis. With hints of vanilla, cinnamon, maraschino liquer and baked with glacé cherries, sultanas, and candied peel, this is a trend we wouldn’t mind having back.

A return to its linguistic roots: Wimbledon, a southwest suburb of London, derives from Wunemannedune circa 950 . It probably means “hill of a man” from Old English dūn and an Old English personal name. It evolved to Wymmendona in the twelfth century and eventually made its way to Wimbeldon in 1211. So, shall we be seeing you at Wymmendona next year?

Healthy tennis bodies: Here’s hoping that we’ll see medical advancements amerliorating tennis elbow, a form of tendinitis common in tennis players, and tennis leg, sudden sharp pains in the calf due to degeneration of the tendon. King Kong arm also seems like something to worry about.

Tennis court theatres: In the unlikely and unfortunate event that tennis becomes obsolete, the courts at Wimbledon could be converted into playhouses, just as it happened in France in the seventeenth century. Molière’s company, the Illustre Théâtre, was originally a tennis court until its conversion in 1643, as was the first Paris opera house.

Email tennis: If the above plays out, you can be comforted by email tennis, the rapid fire exchange of emails. Can you write an email faster than Nadal’s serve?

No matter the changes, hopefully one thing will stay the same. In tennis, zero points is notated as “love,” from the phrase “play for love [not for money].” Here’s to many more years of tennis, filled with love of the game!

Alana Podolsky works on the publicity team at OUP USA. Although she lost every tennis match in which she competed (0-6, 0-6), she’s still a tennis fan. You can follow her on twitter @aspodolsky. You can find more about the resources mentioned in this article at Oxford Reference.

Oxford Reference is the home of Oxford’s quality reference publishing, bringing together over 2 million entries, many of which are illustrated, into a single cross-searchable resource. With a fresh and modern look and feel, and specifically designed to meet the needs and expectations of reference users, Oxford Reference provides quality, up-to-date reference content at the click of a button.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only sports articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post An Oxford Companion to Wimbledon appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWimbledon, Shakespeare, and strawberriesOh, I say! Brits win WimbledonSix surprising facts about “God Bless America”

Related StoriesWimbledon, Shakespeare, and strawberriesOh, I say! Brits win WimbledonSix surprising facts about “God Bless America”

Suspicious young men, then and now

What do Edward Joseph Snowden and Samuel Taylor Coleridge have in common? Both were upset by government snooping into private communications on the pretext of national security. Snowden exposed the US National Security Agency’s vast programs of electronic surveillance to the Guardian and the Washington Post. Coleridge belittled the spy system of William Pitt the Younger in his autobiography, Biographia Literaria (1817).

Nothing new here, except the technology being used to snoop and the media being snooped into It’s all on a spectrum, that expands or contracts over time, depending on the need — the perceived national emergency. But the methods used are always state-of-the-art, whatever that state is, in the 1790s or the 2010s.

Why the 1790s? That was the time of the French Revolution, when it was “bliss to be alive,” and “very heaven to be young,” according to Coleridge’s friend Wordsworth. Yet those heady times of liberty, fraternity, and equality also saw quantum leaps in the means used to spy on individual persons or suspect groups of persons — often in the name of protecting Liberty, Fraternity, and Equality themselves. The kangaroo courts of the French Reign of Terror and the packed juries of Britain’s Reign of Alarm depended for their operation, and their self-defined successes, on new sources of information and ways of information-gathering. Indeed, the very word ‘information’ gained one of its modern meanings in those best and worst of times: information was what an informer delivered to you, if you were a spy master. And such informations were the evidence used in special courts set up to punish the enemies of the state’s reigning ideology.

There were more trials for treason and sedition in 1790s Britain than at any other time in its history, before or since. Much of the evidence produced in these trials came from violations of civil rights that few persons dared to protest. The right of habeus corpus, the very cornerstone of British civil liberties, was suspended for a total of nearly four years during the decade. Letters were openly routinely by Post Office at the beck of local magistrates (“I suspect them grievously,” said Coleridge), or hints relayed from Whitehall that someone in their neighborhood might be in cahoots or correspondence with French revolutionaries.

‘Smelling out a Rat; — or The Atheistical-Revolutionist disturbed in his Midnight “Calculations”‘ (James Gillray, 3 December 1790) (c) National Portrait Gallery. Used with permission.

One example of such surveillance has become a long-standing joke because its target, Coleridge, presented it as one in his Biographia, published 20 years after the event. But at the time, in August of 1797, Coleridge was scared out of his wits, betraying and abandoning friends in his haste to protect himself from suspicion. A Home Office agent had been sent down from London to check on the reported suspicious doings of Coleridge and Wordsworth, and their temporary guest, the radical orator, John Thelwall, Public Enemy No. 1 since his acquittal in the great Treason Trials of 1794. The agent accurately reported that this was no group of French revolutionary sympathizers, but “a gang of disaffected Englishmen,” which they certainly were. Disaffection is not, however, treason — or only becomes so when the stakes or the threats are very high, as they must have seemed to Edward Snowden when he publicized his information about the NSA (a.k.a., jokingly, ‘No Such Agency’).

Coleridge’s joke name for his agent was ‘Spy Nozy.’ His real name was James Walsh, but Coleridge pretended that Walsh thought the poets’ conversations about Spinoza referred to him. But it was all a literary fabrication by Coleridge, safely in the clear, 20 years after the fact and, not at all coincidentally, two years after the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo had ended Britain’s fears about revolution and invasion. The joke, of course, was the idea that harmless poets could have said anything of interest to a government spy. But that was no joke in 1797, especially not for Coleridge, who was desperately trying to distance himself from his very radical lectures, letters, and poems of 1793-1796.

Not that he would’ve been convicted of espionage or conspiracy. But to the extent that he could have been widely suspected of uttering unpatriotic words, his career prospects could’ve been seriously compromised, if not ruined. James Gillray’s cartoon, “Smelling out a Rat,” is a good visual representation of how this process of alarming suspicion worked. (Rev. Richard Price is the rat/victim here.)

This is what will happen, at a minimum, to the prospects of Edward Snowden, even if he manages to stay out of jail. Snowden is admittedly guilty of something; the US government calls it espionage. Like WikiLeaks’ Julian Assange, Snowden’s future career choices will be drastically narrowed. For other idealistic young people, disaffected by their government spying on them for their own good, the example of Snowden will be cautionary. So too was the example of ‘Spy Nozy’ to Coleridge and Wordsworth and Thelwall: they dropped out of sight for a few years, laying low in Germany or deepest Wales.

The effects of the information supplied by ‘Spy Nozy’ and other agents like him in Pitt’s Reign of Alarm, on members of the young Romantic generation, was both immediate and long-term. They saw that their liberal words and actions would have to be soft-pedaled, destroyed, or radically (that is, conservatively) revised, once the extent of their government’s determination to squash dissent became clear.

Kenneth R. Johnston is the author of Unusual Suspects: Pitt’s Reign of Alarm and the Lost Generation of the 1790s. He is also the author of The Hidden Wordsworth: Poet, Lover, Rebel, Spy (1998) and Wordsworth and “The Recluse” (1984), and editor of Romantic Revolutions (1990). He is Ruth N. Halls Professor of English Emeritus at Indiana University and has held Guggenheim, Fulbright, and National Endowment for the Humanities fellowships.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Suspicious young men, then and now appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesNelson Mandela: a precursor to Barack ObamaUS Independence Day author Q&A: part fourUS Independence Day author Q&A: part two

Related StoriesNelson Mandela: a precursor to Barack ObamaUS Independence Day author Q&A: part fourUS Independence Day author Q&A: part two

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers