Oxford University Press's Blog, page 927

July 5, 2013

The third parent

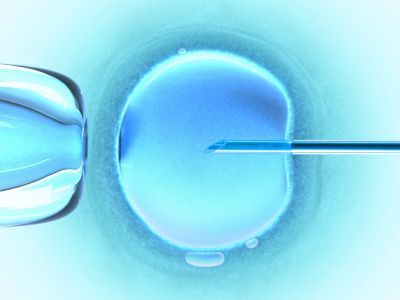

The news that Britain is set to become the first country to authorize IVF using genetic material from three people—the so-called ‘three-parent baby’—has given rise to (very predictable) divisions of opinion. On the one hand are those who celebrate a national ‘first’, just as happened when Louise Brown, the first ever ‘test-tube baby’, was born in Oldham in 1978. Just as with IVF more broadly, the possibility for people who otherwise couldn’t become parents of healthy children is something to be welcomed. On the other side, the cry goes up that this is a slippery slope, the thin end of the wedge, or any other cliché that you care to click on. At any rate, it is not a happy event, taking us one step further towards the spectre of ‘designer babies’. The issue here is about meddling with nature for the sake of hubristic human desires: seeking to ensure the production of a ‘perfect’ baby, and in the process creating the new monstrosity of triple parenthood.

The negative line about the new baby-making procedure is most often countered in these arguments by pointing out how negligible, in reality, is the contribution of the shadow third party. All that happens is that a dysfunctional aspect of the (principal) mother’s DNA is, as it were, written over by the provision of healthy mitochondrial matter from the donor. This means that the resulting baby will not go on to develop debilitating hereditary diseases that might otherwise have been passed on. The handy household metaphor of ‘changing a battery’ is much in use for this positive line; the process should be seen as just an everyday update. But the way that the argument is made—presenting the new input as a simple enabling device—reveals a need to switch off any suggestion that this hypothetical extra parent has any fundamental importance. The real identity of the future child must be seen to come from a primary mother and father, and them alone.

According to the established facts of life, it might seem obvious enough that a baby has two biological parents, and that the contribution is distributed between them with the god-given genetic equality of exactly twenty-three chromosomes each. But that is to forget a third biological element, the female body in which the new baby grows from conception (or just after, in the case of IVF) to birth. This used to be elided in the obvious certainty of maternal identity: if a woman gives birth, then the baby is ‘biologically’ hers — she was pregnant, the ovum came from her. (Whereas a father, until DNA testing, was always uncertain—pater semper incertus est, in the legal phrase—in the sense that there was no bodily evidence of any particular man having engendered any particular child.) But modern medical science has brought about the practical as well as the theoretical separation of egg and womb, breaking up what had previously appeared—and still usually is—as one single biological mother.

According to the established facts of life, it might seem obvious enough that a baby has two biological parents, and that the contribution is distributed between them with the god-given genetic equality of exactly twenty-three chromosomes each. But that is to forget a third biological element, the female body in which the new baby grows from conception (or just after, in the case of IVF) to birth. This used to be elided in the obvious certainty of maternal identity: if a woman gives birth, then the baby is ‘biologically’ hers — she was pregnant, the ovum came from her. (Whereas a father, until DNA testing, was always uncertain—pater semper incertus est, in the legal phrase—in the sense that there was no bodily evidence of any particular man having engendered any particular child.) But modern medical science has brought about the practical as well as the theoretical separation of egg and womb, breaking up what had previously appeared—and still usually is—as one single biological mother.

Twofold motherhood plays out in various possible scenarios. Conception outside the womb—in vitro fertilization—leads to the possibility of a woman giving birth to baby of which she is not the genetic mother. Depending on whether that baby is going to become the (postnatal) child of the birth mother or else of the woman whose body provided the egg, this pregnant woman will be referred to as either the mother or the surrogate. Or, to tell the same story from the genetic point of view, IVF leads to the possibility of one woman’s egg making an embryo which develops in another woman’s womb. Depending on which of them is to raise the child, she will be regarded as either the egg donor or the mother (who used a surrogate).

In all these scenarios—two in reality, four in story—biological motherhood is already divided between two women, with one or other element—the egg or the pregnancy—emphasized, depending on which of them is to become, in practice, the baby’s mother. In other words, biologically three-parent babies are nothing new (or only as new as IVF). But the drive is always towards the subordination of one maternal biological contribution so as to validate the other (and to remove the risk that the discounted proto-parent, the donor or the ‘gestational carrier’, might have any postnatal responsibilities or rights). This is what is happening again with the latest controversy over the additional mitochondrial ‘mother’. Biological parenthood is what is sought, but the biological element can have more than one definition, more than one physical manifestation.

The invention of reproductive technologies has had the odd effect of reinforcing—if it did not generate—a belief that the child of one’s own, that object of desire, should be above all the ‘biological’ child of those who seek to ‘have’ it. In one way this contemporary valorization marks a bizarre departure from earlier modern times when the bodily part of parenthood was something that women more often sought to be free from. In A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, at the end of the eighteenth century, Mary Wollstonecraft urged her fellow women to think of themselves as something above mere reproductive organisms, ‘born only to procreate and rot’. Wollstonecraft considered motherhood to be one of the privileges of being a woman. She was also a passionate advocate of maternal breastfeeding at a time when women regularly paid other women to take on that physical aspect of motherhood; wet-nurses are another example of supplementary mothers. But even so, she vehemently rejected the notion that having babies should be thought of as the be-all of human female lives. Procreating and rotting is what plants and animals do: purely biological parenthood.

Rachel Bowlby is Lord Northcliffe Professor of English at University College London. Her new book is A Child of One’s Own: Parental Stories, which uses six case studies from literature to offer fresh angles and arguments for thinking about parenthood today.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or Are we alone in the universe?

New UPSO partners quiz with Liverpool and Stanford

How well do you know Liverpool University Press and Stanford University Press, the newest members of the University Press Scholarship Online (UPSO) family? Take our quiz to test your knowledge! Search for answers on the “About” and “Reviews and Awards” pages of Liverpool Scholarship Online, and the “About,” “Reviews and Awards,” and “Letter from the Director” pages of Stanford Scholarship Online. Good luck!

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

University Press Scholarship Online brings together the best scholarly publishing from leading university presses around the world, making disparately-published works easily accessible, highly discoverable, and fully cross-searchable via a single, state-of-the-art online platform. UPSO concentrates research through its powerful and sophisticated search and browse functionality, providing access to thousands of books across over 20 subject areas in the humanities, social sciences, sciences, medicine, and law.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only media articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post New UPSO partners quiz with Liverpool and Stanford appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBring me a scapegoat to destroy: babies, blame, and bargainsEthical and Legal Considerations QuizNelson Mandela: a precursor to Barack Obama

Related StoriesBring me a scapegoat to destroy: babies, blame, and bargainsEthical and Legal Considerations QuizNelson Mandela: a precursor to Barack Obama

Nelson Mandela: a precursor to Barack Obama

By Elleke Boehmer

Not long before Barack Obama was first elected President of the United States, in October 2008, the African American novelist Alice Walker commented that the then still Senator Obama, as the leader in waiting of the most powerful nation on earth, might be regarded as a worthy successor to the towering figure of Mandela. She discerned within the American leader’s authoritative and crusading self-presentation the template of Robben Island’s most famous one-time resident.

In the run-up to Nelson Mandela’s 95th birthday on 18 July this year, still within the first year of Obama’s second term as US President, it is an interesting line of thought to pursue: to what extent might we regard the older man as a precursor to the younger. Especially in so far as Obama, too, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, if in a prospective way in 2008 to stand beside Mandela’s award in 1993, might lines of influence and political genealogy be traced between them? Is it possible to say that Mandela showed Obama a way to moral power and political authority (which is not of course to overlook the important inspiration of others, including another Nobel Peace Laureate, Martin Luther King, Jr.). In these paragraphs I’d like to unwrap the dynamics and semantics of this proposed line of inheritance a little more and ask what might be involved when we say that Obama stands on the shoulders of Mandela.

Of course any comparison between the leaders Nelson Mandela and Barack Obama must recognize that they emerge out of very different historical times, family backgrounds, and national geographies. To begin with, Mandela was born in 1918, Obama several generations later in August 1961. Obama is American though of part-African (Kenyan) descent; Mandela stems from a minor branch of a Xhosa royal family. Yet for these very reasons the parallels between them in terms of leadership style and approach are the more striking, as of course are the connections that can be drawn between their political reputations and historical legacy, including the remarkable charisma that unites them. Both embody that quality of “individual personality … set apart from ordinary men,” defined as the charisma of a great leader by social theorist Max Weber. Both were keenly aware from the beginning of their leadership that their good guidance could help found, consolidate, and safeguard traditions of democracy for their countries. At the same time they saw, too, that they, in themselves, could represent important sources of inspiration and legitimation for those national communities. Moreover, perceiving this, both were open to moulding their own symbol status or iconicity—though Mandela perhaps more overtly and ostentatiously than Obama. For example, Mandela was always keen to play to the ways in which his own life or biography could be seen to underpin South Africa’s long road to freedom. If Obama’s triumph in 2008 could be viewed as representing the fulfilment of Martin Luther King’s dream, this was something that he certainly signaled in his Acceptance and Inaugural Speeches in 2008 and 2009. Not coincidentally perhaps, both Mandela and Obama were trained as lawyers, and share a keen sense of the power of the word and the symbol, of verbal advocacy and defence.

Of course any comparison between the leaders Nelson Mandela and Barack Obama must recognize that they emerge out of very different historical times, family backgrounds, and national geographies. To begin with, Mandela was born in 1918, Obama several generations later in August 1961. Obama is American though of part-African (Kenyan) descent; Mandela stems from a minor branch of a Xhosa royal family. Yet for these very reasons the parallels between them in terms of leadership style and approach are the more striking, as of course are the connections that can be drawn between their political reputations and historical legacy, including the remarkable charisma that unites them. Both embody that quality of “individual personality … set apart from ordinary men,” defined as the charisma of a great leader by social theorist Max Weber. Both were keenly aware from the beginning of their leadership that their good guidance could help found, consolidate, and safeguard traditions of democracy for their countries. At the same time they saw, too, that they, in themselves, could represent important sources of inspiration and legitimation for those national communities. Moreover, perceiving this, both were open to moulding their own symbol status or iconicity—though Mandela perhaps more overtly and ostentatiously than Obama. For example, Mandela was always keen to play to the ways in which his own life or biography could be seen to underpin South Africa’s long road to freedom. If Obama’s triumph in 2008 could be viewed as representing the fulfilment of Martin Luther King’s dream, this was something that he certainly signaled in his Acceptance and Inaugural Speeches in 2008 and 2009. Not coincidentally perhaps, both Mandela and Obama were trained as lawyers, and share a keen sense of the power of the word and the symbol, of verbal advocacy and defence.

Both men, too, derived strength and inspiration from their African descent. Obama has many times recognized, most obviously in Dreams from My Father, that it wasn’t till he had accepted his black identity as fundamental to his makeup that he was able to step forward as a representative and leader of Americans of all races. As for Mandela, the pride in his Xhosa background and traditions that was instilled in him through his upbringing was essential for the resilience he showed in withstanding apartheid and feeling that he could speak for all South Africans, black and white. In the case of both leaders, therefore, not merely their African descent but how they embraced it, were key catalysts in the mix of character, charisma, and achievement that underpinned their leadership. Throughout, both leaders have been concerned to resist and at all levels to work against the pariah status to which Africa and Africans were once relegated in history.

But perhaps the most persuasive obvious commonality between them lies in respect of their media performances (which Alice Walker in the run-up to Obama’s first election no doubt had in forefront of her mind). Mandela is more formal and stilted in his political rhetoric than Obama, yet both leaders, building on their self-perceived messianic roles in history, have not been averse to striking the prophetic note. Both Obama’s acceptance speeches have been particularly compelling in their reference to moving on from the suffering of the past to a more hopeful and united future. His rhetoric has called an American nation into being in which African Americans regardless of their class have an equal status, and equal opportunities, to white Americans. As for Mandela, he, too, in this many speeches after his release in 1990 addressed his exhortatory and as ever performative remarks to a united South Africa: “Let freedom reign. Let a new age dawn.” Here was the President in waiting announcing himself both to the world and to his strife-torn country as a man proceeding with caution, yet filled with hope, much like Barack Obama some 14 years on.

Elleke Boehmer is Professor of World Literature in English, University of Oxford and the author of Nelson Mandela: A Very Short Introduction.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: By David Lee Katz, Special Assistant to Senator Barack Obama [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Nelson Mandela: a precursor to Barack Obama appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesUS Independence Day author Q&A: part twoUS Independence Day author Q&A: part fourUS Independence Day author Q&A: part three

Related StoriesUS Independence Day author Q&A: part twoUS Independence Day author Q&A: part fourUS Independence Day author Q&A: part three

July 4, 2013

Anaesthesia exposure and the developing brain: to be or not to be?

Rapidly mounting animal evidence clearly indicates that exposure to general anaesthesia during the early stages of brain development results in long-lasting behavioural impairments. These behavioural impairments manifest as reduced performance in tests of learning and memory know as cognitive deficits, lack of motivation, and problems with social interactions. Some worrisome similarities are apparent when emerging human data are carefully compared with animal data. For instance, rodent data suggest that although anaesthesia exposure in neonatal animals leads to slow learning in adolescence, completing the task is still attainable. As the animals approach middle age the completion of more complex tasks is not possible, thus creating a wider learning gap when compared to control animals. This suggests impairment of normal mental functions critical to higher cognitive functions such as complex memory.

Some emerging human retrospective data suggest that multiple exposures to anaesthesia during critical stages of brain development in early childhood result in learning disabilities that tend to be first detected in early school-age, but which are more pronounced in late teenage years as the complexity of cognitive tasks increases and competitive pressures mount. Interestingly, when the effect of exposure to morphine during early infancy was examined using standardized IQ testing, it was concluded that the visual analysis component was significantly and consistently impaired when these children were followed for the first 5 years of life. This is a tantalizing observation in view of the fact that the visual analysis test is the best prognostic evaluator of higher-order neurocognitive function and, as such, is the most reliable predictor of the development of higher learning functions as well as the ability to organize thoughts and activities in meaningful sequence, to manage multiple tasks in organized fashion and to make high-level decisions (often referred to as ‘executive’ functions).

Some emerging human retrospective data suggest that multiple exposures to anaesthesia during critical stages of brain development in early childhood result in learning disabilities that tend to be first detected in early school-age, but which are more pronounced in late teenage years as the complexity of cognitive tasks increases and competitive pressures mount. Interestingly, when the effect of exposure to morphine during early infancy was examined using standardized IQ testing, it was concluded that the visual analysis component was significantly and consistently impaired when these children were followed for the first 5 years of life. This is a tantalizing observation in view of the fact that the visual analysis test is the best prognostic evaluator of higher-order neurocognitive function and, as such, is the most reliable predictor of the development of higher learning functions as well as the ability to organize thoughts and activities in meaningful sequence, to manage multiple tasks in organized fashion and to make high-level decisions (often referred to as ‘executive’ functions).

While still controversial and unproven, the similarities between animal and human findings suggest that the gap in cognitive abilities caused by early exposure to general anaesthesia widens with age, leading to speculation that anaesthesia initiates a slow but inevitable reduction in cognitive reserve that could prove to be detrimental to higher intellectual performance later in life. Could it be that disturbing the fine balance between neuronal activity and quiescence reflected as action potential spikes on the one side and between excitatory and inhibitory driving forces that determine neuronal activity on the other side during critical stages of neuronal network formation has such long lasting impact on brain functioning? Or put another way, could it be that general anaesthesia initiates slow but inevitable depletion of cognitive reserve that not only prevents children from reaching their full intellectual potential but speeds cognitive decline in late adulthood, a cognitive decline that can lead to early dementia? While these possibilities are far from established, being able to answer such questions with certainty poses a monumental but worthy challenge to modern anaesthesia and neuroscience.

Vesna Jevtovic-Todorovic, MD, PhD, MBA is Harold Carron Endowed Professor of Anesthesiology and Neuroscience. An internationally recognized neuropharmacologist and the founder of the field, Dr. Jevtovic-Todorovic is an expert in developmental neurotoxicity and pathophysiogy of chronic pain. Hugh C. Hemmings Jr., MD, PhD, FRCA is Distinguished Research Professor in Anesthetic Mechanisms, Professor of Anesthesiology and Pharmacology, and Chair of Anesthesiology at Weill Cornell Medical College, and Anesthesiologist-in-Chief at New York Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell. An internationally recognized neuropharmacologist, Dr. Hemmings is an expert in the synaptic effects of general anesthetics and mechanisms of neuronal signal transduction.

BJA: British Journal of Anaesthesia has published a special issue on anaesthetic neurotoxicity and neuroplasticity, arising from a BJA-sponsored workshop on this topic and guest edited by Hugh Hemmings, Jr and Vesna Jevtovic-Todorovic. You can browse the table of contents and read all content from the issue free online. Founded in 1923, one year after the first anaesthetic journal was published by the International Anaesthesia Research Society, BJA remains the oldest and largest independent journal of anaesthesia.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Intravenous transfusion in emergency room. By beerkoff, via iStockphoto.

The post Anaesthesia exposure and the developing brain: to be or not to be? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesForcible feeding and the Cat and Mouse Act: one hundred years onPrepare for the worstAre we alone in the universe?

Related StoriesForcible feeding and the Cat and Mouse Act: one hundred years onPrepare for the worstAre we alone in the universe?

Six surprising facts about “God Bless America”

Some of my friends hate “God Bless America.” They find it sentimental, old-fashioned, cheesy. They bristle at its over-the-top jingoism, at its exceptionalism that seems out of step with the globalism of the twenty-first century. They say it violates the separation of church and state. They associate it with Bush, or Reagan, or Nixon, with the boring, mainstream, un-groovy side of American culture.

You may feel this way, too. Or you may appreciate the song and its prayerful love of country, enjoy its unapologetic patriotism, revel in the nostalgia it evokes, be moved by its associations with 9/11. Or you may not ever have given the song much thought. No matter what you think of it, “God Bless America” is more than just a simple patriotic tune. Here are some things about the song’s early history that might surprise you:

It was written by Irving Berlin.

Like so many songs that have entered in American consciousness, “God Bless America” has attained the composerless status of an anthem or a folk song, but it has roots in Tin Pan Alley. Irving Berlin originally wrote it in 1918 as the finale to an all-soldier revue called Yip, Yip, Yaphank, but he ultimately decided not to include it, tucking it away in his trunk of discarded songs.

When it was first performed, it was considered a “peace song.”

Today, “God Bless America” is often used as a symbol of support for war, sung by soldiers in uniform at baseball games and other events. But when Irving Berlin rediscovered his old song in 1938, he had been looking for a “peace song” as a response to the escalating conflict in Europe. He made changes to it and gave it to radio star Kate Smith to perform on her radio show on the eve of the first official celebration of Armistice Day—a holiday originally conceived to commemorate world peace and honor veterans of the Great War (the peace part would be dropped in 1954, when it became Veteran’s Day). When Kate Smith first performed the song on 10 November 1938, the verse evoked the escalating tensions in Europe (“As the storm clouds gather far across the sea”), and included a line that reflected the public mood of non-interventionism in the conflict: “Let us all be grateful that we’re far from there.”

It premiered one day after Kristallnacht.

“God Bless America” didn’t remain a peace song for long. The song’s debut happened to coincide with a pivotal event in the history of World War II: Kristallnacht, the Nazi’s attacks on Jewish communities, which signaled a turning point for a growing American condemnation of Nazi Germany and a move away from isolationism. By the spring of 1939, the line in the verse had been changed to “Let us all be grateful for a land so fair,” and by 1940, the song was embraced as an interventionist anthem by those urging the United States to join the war.

It inspired the song “This Land Is Your Land.”

In 1940, Woody Guthrie wrote his own patriotic song as an angry response to “God Bless America,” which he felt glossed over the problems of a country still suffering from the Great Depression. Guthrie’s original refrain—“God blessed America for me”—was later changed to “this land was made for you and me.”

It sparked an anti-Semitic backlash.

Since Irving Berlin was a Jewish immigrant (born Israel Baline, the son of a Jewish cantor who fled persecution in Europe), there were some who questioned both his right to evoke God and to call the United States his “home sweet home.” In 1940, the song was boycotted by the KKK and the Nazi-affiliated German American Bund, and one leader of a domestic pro-Nazi group blasted the song as an anthem for a Jewish conspiracy for control.

It has always been under copyright.

Though embraced as an unofficial anthem, “God Bless America” has roots in the Tin Pan Alley music business, and has always had a hidden commercial side. But Irving Berlin himself has never made money on the song; in 1940, he created the God Bless America Fund, through which all royalties have been donated to the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts.

Whatever you may think of “God Bless America,” the song serves as a reminder that a seemingly simple aspect of American culture can reveal fascinating aspects of our history. When you hear it this Fourth of July (as you inevitably will), you can use it as an opportunity to reflect on how its meaning has shifted in the 95 years since it was stashed away as a discarded pop song.

Sheryl Kaskowitz is the author of God Bless America: The Surprising History of an Iconic Song. She is a scholar of American music who has most recently served as a lecturer in American Studies at Brandeis University.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Six surprising facts about “God Bless America” appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTV got game? The NBA on NBC and other b-ball tunesRobert Kennedy’s Battle HymnUS Independence Day author Q&A: part four

Related StoriesTV got game? The NBA on NBC and other b-ball tunesRobert Kennedy’s Battle HymnUS Independence Day author Q&A: part four

US Independence Day author Q&A: part four

Happy Independence Day to our American readers! In honor of Independence Day in the United States, we asked some of our influential American history and politics VSI authors to ask each other some pointed questions related to significant matters in America. Their passionate responses inspired a four day series leading up to America’s 237th birthday today. Today Richard M. Valelly, author of American Politics: A Very Short Introduction wraps up the series with his answers. Previously L. Sandy Maisel, Donald A. Ritchie, and Charles O. Jones shared their views.

L. Sandy Maisel (American Political Parties and Elections VSI) asked: Should political leaders be judged by their ability to achieve compromise solutions to divisive issues or by their willingness to stand on principle, rather than to compromise?

Richard M. Valelly: I agree with the implicit premise of your question, that a dilemma has emerged for presidential or congressional leadership — compromise is no longer celebrated, and instead is criticized and denounced by pundits or advocacy groups. On the other hand, there is an austerity caucus in American politics — and a great deal of alarmism about major public policies being broken when in fact they are not, a leading example being Social Security, which needs only marginal adjustments to survive. So calls for compromise can be stalking horses for sweeping and unnecessary changes to successful programs. Standing on principle may, counter-intuitively, promote caution and prudent action.

L. Sandy Maisel: At other times in our nation’s history when partisan rancor has dominated the policymaking process, what steps have leaders taken to move the national discussion forward?

Richard M. Valelly: A time-honored step is the commission model. Another is to go on a listening tour. But ultimately the best step is to listen carefully to what well-designed and reliable surveys tell us about what the public wants. Benjamin Page and Robert Shapiro made a strong case for the rational public some time ago — and we know from the work of Martin Gilens that much of the public is ignored. That needs to change. The majorities that show up in public polls are artifacts of surveys, yes, but they tell us a lot about the citizenry wants government to do. Nate Silver said it best: there is a signal in the noise. Let’s listen to these signals. I’m not calling for government-by-polling, but I do think that the ordinary citizen needs better representation for the simple reason that ordinary citizens are remarkably moderate.

Charles O. Jones ( The American Presidency VSI) asked: Conventional wisdom has it the out-party does not have either a single leader, or even, nationally, a means to integrate policy proposals. Yet today the Republican Party is challenged to have an “agenda” akin to a national platform. Is this a change? Or merely a media illusion?

Richard M. Valelly: This is a change, and it goes back to the speakership of James Wright and the speakerships since then, including the Contract With America. The out-party has been programmatic for nearly 30 years now, as David Rohde first showed in his discussion of conditional party government.

Charles O. Jones: What has been the effect on the congressional committees of having outside “gangs” and/or public agenda campaigns by presidents? Immigration being the most recent case, Social Security for Bush 43 (but there are many such).

Richard M. Valelly: The “gangs” and other informal coalitions broker discussions that are now harder for formal party leaders than they once were. They seem to be a partial solution to the effects of polarization on the policy process.

Donald A. Ritchie (The US Congress VSI) asked: The US Congress has been called a “broken branch.” If that’s so, whose fault is it: the institution, the political parties, or the voters?

Richard M. Valelly: Polarization has changed Congress, so the short answer is that the parties are at fault. But Congress is very resilient, as such congressional developmental scholars as Sarah Binder, David Mayhew, and Eric Schickler, among others have shown. Sarah is probably the most concerned, and David the most sanguine within the community of political science congressionalists. There is some fascinating new work by and Alan Wiseman that shows that “gridlock” is not a one-size-fits-all phenomenon, but varies by issue domain. And as Scott Adler and John Wilkerson have shown, a lot of the congressional agenda is non-discretionary. Congress does lots of work all the time. If anything seems really broken, it is regular order in the budget process, but we’ve been there before (we spent the entire 19th century there in fact), and deficit politics, in an age of fiscal constraint, is going to make Congress look “broken” for quite a while. But I’m not sure that that means that the institution itself is anywhere near being permanently broken.

Richard M. Valelly is Claude C. Smith ’14 Professor of Political Science at Swarthmore College. His publications include American Politics: A Very Short Introduction, Princeton Readings in American Politics (2009), The Two Reconstructions: The Struggle for Black Enfranchisement (2004), which won several prizes, and Radicalism in the States: The Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party and the American Political Economy (1989).

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook. Read more in the Independence Day Q&A series.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post US Independence Day author Q&A: part four appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesUS Independence Day author Q&A: part twoUS Independence Day author Q&A: part threeUS Independence Day author Q&A: part one

Related StoriesUS Independence Day author Q&A: part twoUS Independence Day author Q&A: part threeUS Independence Day author Q&A: part one

July 3, 2013

When it rains, it does not necessarily pour

Contrary to some people’s expectation, July has arrived, and it rains incessantly, that is, in the parts of the world not suffering from drought. I often feel guilty on account of my avoiding the burning questions of our time. Experienced word columnists tend to begin their notes so (my example is of course imaginary): “Last week the President declared: ‘These shenanigans won’t deceive anybody.’ What can we say about the word shenanigans? According to the OED…. Professor S. of Shine-Sheen College confirmed in a telephone interview that, to the best of his knowledge, no consensus exists as to where the word came from. However…” This is what I call socially sensitive, sustainable word journalism: no sooner said than done. Today is my turn. The Fourth of July is with us, it raineth on the just and the unjust, and I want to rise to the importance of the moment. What then is the origin of the word rain? This question will not go away, and, even if does, it will come another day.

Walking in the Rain by Paul Sawyier, c. 1910. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Wherever the Germanic-speakers may have had their homeland, they appeared in the light of history with the same word for “rain.” It has been attested in all their old languages, including Gothic (the fourth century CE), approximately in the form regn. But other Indo-Europeans had other names for it (compare Latin pluvia and Russian dozhd’), so that we cannot decide whether the root reg’- or rek’- had any counterpart outside Germanic, and, if it did, what it meant. Old Icelandic raki “dampness,” a slew of Lithuanian words with the r-k root, and especially Latin rigare “moisten” (compare Engl. ir-rig-ate) have been cited in connection with rain. The problem has never been resolved. Some dictionaries say “etymology doubtful (uncertain, unknown),” while others give it as established, ignoring the difficulties they have chosen to bypass.

“Rain” need not have signified “water,” “moisture, vapor,” or “wet” (such is the range of meanings in the putative cognates of the Germanic noun). People distinguish between several kinds of water falling from the sky. Rain (the most abstract of the many synonyms) is, we are told, “condensed vapor of the atmosphere falling in drops” (true enough), while shower refers to “a brief and usually short fall of rain” (also true; only showers, not rains, can be scattered, and only they can bring May flowers). Rains, in the plural, unless it refers to a rainy season, sounds suspicious; compare Kipling’s: “In August was the Jackal born;/ The rains fell in September; ‘Now, ‘such a fearful storm’/ Says he/ ‘I can’t remember’”. By the way, the oldest sense of the Germanic word for “shower” seems to have had harsher connotations than those familiar to us. In Gothic, the phrase skura windis, literally “storm of wind,” has been recorded, and in all probability, Latin caurus and some other Indo-European words for “north” are related to s-kura. The violence associated with shower may corroborate my guess presented below.

A look at the many words for “rain” shows how varied the picture is. Russian liven’ “downpour” has the root of the verb for “flow.” Compounds (like downpour) are plentiful. For instance, in German we find Platzregen (platz- “to explode, burst,” Regen “rain,” and the usual gloss for the long word is “cloudburst,” which is correct), Staubregen, Sprühregen, and Niselregen (all three mean “drizzle”: Staub “dust,” sprühen “to spray”; niesen “to sneeze,” nieseln “to drizzle,” both are related to Engl. s-neeze). Engl. drizzle, which conveniently rhymes with fizzle and sizzle, has the root of the Old English verb dreosan “to fall” (dross may be akin to it), but drizzle is not any rain that “falls” to the ground: it must fall in very fine drops. Swedish has regndusk and Norwegian has duskregn (Swedes and Norwegians often do things differently). If dusk is related to Russian dozhd’, mentioned above, both are, from a historical point of view, tautological compounds “rain-rain” (such compounds were once the subject of a special post of mine).

Ray Embankment in Basel in the rain by Alexandre Benois, 1896, via Wikipaintings

We can see that people are most particular when it comes to characterizing “rain.” This is probably the reason we cannot be sure about the origin of the word that interests us. It so happens that I too have a hypothesis concerning the derivation of rain. No proof can be advanced in such cases, but it will be a pity to keep even the tiniest light under the bushel, so I am going to reveal it. The inspiration for my conjecture (a mere guess really rather than a hypothesis) was the German idiom es regnet in Bindfäden “it rains cats and dogs” (another post of mine was devoted to the enigmatic English phrase). Bindfäden is the plural of Bindfaden “string.” The image is clear: it rains so hard that the streams of water seem to stand in the air like ropes. Similarly, the Swedish idiom regnet står som spön i backen, said about a heavy downpour, means literally “the rain stands as (a) rod in the bank,” the picture being not too remote from that of German strings or ropes. So it occurred to me that perhaps the Old Germanic word for “rain” designated just such a downpour.The Germanic languages, especially Dutch, German, and those of Scandinavia, are full of verbs like ragen ~ raga ~ rage “rise, tower” and “move furiously” (there are especially many of them in dialects, but Engl. rage, from Latin, via Old French, from rabia ~ rabies, has nothing to do with them). I assume that all of them are related. By the rule of vowel alternation (as in German geben ~ gab “give ~ gave”), rag- would naturally alternate with reg-. Is it possible that the ancient form reg-n- has no direct connection with any word in Latin, Sanskrit, Lithuanian, and the rest and signified a furious shower, when it seemed that water “stood” like a rod in the air?

“It was not like our soft English rain that drops gently on the earth; it was unmerciful and somehow terrible; you felt in it the malignancy of the primitive powers of nature. It did not pour, it flowed. It was like deluge from heaven, and it rattled on the roof of corrugated iron with a steady persistence that was maddening. It seemed to have a fury of its own. And sometimes you felt that you must scream if it did not stop, and then suddenly you felt powerless, as though your bones had suddenly become soft; and you were miserable and hopeless.”

–Somerset Maugham, “The Rain.”

Is this the rain the distant ancestors of the “Teutons” saw somewhere in the south, and is this the reason they called it reg-n-? We will never find out.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post When it rains, it does not necessarily pour appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMonthly etymological gleanings for June 2013Multifarious Devils, part 4. GoblinDrinking vessels: ‘tankard’

Related StoriesMonthly etymological gleanings for June 2013Multifarious Devils, part 4. GoblinDrinking vessels: ‘tankard’

An Independence Day reading list from Oxford World’s Classics

By Penny Freedman

For this month’s Oxford World’s Classics reading list, we picked some of our favorite American classics in honor of Independence Day. There’s no better holiday to celebrate America’s iconic writers, and their great works, than the Fourth of July. Whether you were assigned to read these books in class, or keep meaning to pick up a few of those classics you missed out on, we have something for everyone on the list.

What’s your favorite American novel? Let us know.

This Side of Paradise by F. Scott Fitzgerald

By now, everyone is familiar with The Great Gatsby, thanks in part to the recent release of the movie this spring, which re-invented the story for the big screen. But, have you read Fitzgerald’s first novel? Loosely based on events of the author’s days at Princeton, This Side of Paradise tells the story of Amory Blaine’s pampered life. As he makes his way through Princeton, and falls in and out of love with a series of beautiful women, the realities of life beyond his youth give way to discontent. This novel swiftly launched Fitzgerald into success.

Moby Dick by Herman Melville

Pegged as one of the Great American novels, Moby Dick is the well-known story of a whaling journey full of adventure. Along with Captain Ahab, sailor Ishmael and the crew of the Pequod set off on a doomed voyage that they soon realize serves Ahab’s desire to seek revenge on Moby Dick, the large sperm whale that crippled him. This edition also includes passages from Melville’s correspondence with Nathaniel Hawthorne, another influential author of the time.

The House of the Seven Gables in Salem

The House of the Seven Gables by Nathaniel Hawthorne

You probably remember reading The Scarlet Letter in school, but The House of the Seven Gables is a book you may have missed out on. A Gothic tale of guilt and atonement, the story takes place in a haunted New England mansion in Salem. The house itself is based on Hawthorne’s cousin’s actual home. When a young woman comes to stay she breathes new life and romance into the home, setting a series of events in motion. Similar to The Scarlet Letter, the novel deals with the theme of human guilt, but this tale also weaves in a layer of fantasy.

Little Women by Louisa May Alcott

Long before there was Lean In, there was Little Women, the classic story of strong-minded, independent women with the desire to craft their own destiny. Set in Alcott’s own family home in Massachusetts, this popular American novel follows the lives of the March sisters during the Civil War. A highly biographical story, the struggles that Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy endure give a look into Alcott’s own life. This edition also includes an introduction by Valerie Anderson that sheds more light onto the Alcott family.

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

Famously banned for Twain’s use of language, this classic American novel gives us a closer look at the rambunctious, lovable best friend of Tom Sawyer. Narrated in the illiterate voice of Huck Finn, the story follows the escape from his violent father to the endearing friendship formed during his travels down the Mississippi River with escaped slave Jim. An influential story before its time, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn deals with issues of prejudice, class, and age in America’s Deep South before the Civil War.

Penny Freedman works on Oxford World’s Classics in Oxford University Press’s New York office.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only OWC articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Detroit Publishing Co. From United States Library of Congress‘s Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID det.4a24964. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The post An Independence Day reading list from Oxford World’s Classics appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories10 Questions for Justin Scott10 Questions for Domenica RutaUS Independence Day author Q&A: part three

Related Stories10 Questions for Justin Scott10 Questions for Domenica RutaUS Independence Day author Q&A: part three

Five things you should know about the Fed

This year marks the 100th anniversary of The Federal Reserve, which was created after President Woodrow Wilson signed the Federal Reserve Act on 23 December 1913. In this adapted excerpt from The Federal Reserve: What Everyone Needs to Know, Stephen H. Axilrod answers questions about The Federal Reserve’s historical origins, evolving responsibilities, and major challenges in a period of economic crisis.

Why is the Fed so important to the country?

The Fed is the nation’s central bank and, as authorized by law, independently determines the country’s monetary policy. It has a unique capacity to control inflation, helps moderate cycles in the economy, and acts as a buffer against potentially destabilizing financial and credit market conditions. Policy is normally implemented mainly through three traditional policy instruments: open market operations in government securities, lending via its discount window, and setting reserve requirements on bank deposits.

The Fed also has an important role in establishing the nation’s regulatory policies in the financial area, especially as they apply to commercial banks and certain related entities. Such policies can impinge on and interact with monetary policy and the use of monetary instruments. While a central bank’s monetary policy function is special, its regulatory role is similar to, and shared with, other regulatory authorities in the country. Many, but not all, central banks around the world combine both monetary policy and a certain regulatory authority.

When and why was the Fed founded?

The Fed was originally established in December 1913 under very different economic and financial conditions than currently exist in the United States and the rest of the world. At that time, the financial panics and breakdowns in the banking system that had all too frequently unsettled our economy impelled the Congress to create an institution (the Federal Reserve System) with lending, regulatory, and other powers that could, it was thought, moderate, if not avert, significant financial disruptions.

The United States Federal Reserve Building in Washington, D.C. Photo by Tim Evanson, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

How did the Fed evolve?

The original Federal Reserve Act was modified a number of times. As experience was gained with the central bank’s basic monetary policy instruments, their unique influence on the nation’s overall credit and money conditions became better understood. At the same time, the United States developed into a major worldwide financial and economic power, with increasingly dynamic, and unfortunately still occasionally crisis-prone, markets; the stock market crisis of 1929, the banking crisis of the early 1930s, and the credit crisis of 2008–2009 among the most notable. Practical experience and ongoing economic research helped guide legislative changes that affected the economic and financial role of the Fed and its monetary policy objectives, but not without considerable and occasionally acrimonious debate.

Monetary policy came to be clearly recognized as one of the two major so-called macro-economic tools, along with the US government’s fiscal policy, which help to assure that everyone who wants a job can get one and that the average level of prices remains generally stable. Like other central banks around the world, the Fed is especially concerned with maintaining reasonable price stability over time. In the course of the great inflation of the 1970s, the public became increasingly aware of the institution’s responsibilities to contain inflation. But it also makes decisions to help keep economic activity on an even keel and to avert dangerous financial instabilities—issues that brought the Fed under enormous public and political scrutiny as the great credit crisis of 2008–2009 and its aftermath unfolded.

The Fed of today came into its own after amendments to the Federal Reserve Act by the mid-1930s improved, among other things, the organizational basis for policy, and after 1951, when the institution was freed from agreed restraints that helped finance WWII at low interest rates.

How do the Fed’s unique policy instruments affect the nation’s economy as a whole?

In response to the emerging interest rate effects and changes in credit availability and liquidity from the Fed’s actions, the nation’s economic well-being will be eventually affected in one way or another—indicated by the behavior of economic activity, employment, and the average level of prices. In practice, it takes some time for those influences to be felt. Moreover, the Fed’s degree of influence is not easy to distinguish, given all the other influences, both domestic and international, that weigh on the economy. Over the long run, however, a central bank with its power to create money out of nothing, so to speak, does bear a clear, special responsibility for the behavior of inflation.

A central bank’s powers to create credit or money, in addition to being crucial to its monetary policy function, also serve as a buffer against destabilizing and economically disruptive financial crises. The recent credit crises in the United States and Europe, for instance, were contained, at least to a degree, through an unusually large expansion in the balance sheet of central banks as they provided funds to markets that were being dragged down by bad debts.

In general, the Fed and other central banks can be viewed as unique institutions that, in their money-and credit-creating powers, have the power independently, from on high as it were, to tilt the ongoing balance of supply and demand in financial markets. However, central banks cannot control the ensuing plot development like an author can, and the eventual outcomes of their intervention are shrouded in uncertainty even if the direction appears clear. That is essentially why good central banking depends so much on sound judgment and an almost intuitive feel for markets by its leadership as much as, or more than, practically useful results of economic analysis and research.

What major challenges face the Fed as an organization in the future?

First, the Fed needs somehow to bring regulatory issues more to the fore in considering its monetary policy. It seems to be working in that direction. That will be greatly helped when the President actually nominates a governor to become vice chairman for supervision, the position added in the Dodd-Frank Act.

Second, it behooves the Fed to continue with its efforts to regain the institutional credibility with the public and the Congress that was severely shaken by the credit crisis. It had been thrown into so much doubt that even the Fed’s viability as an independent institution or, perhaps more practically, as an institution that could pursue its independent powers as effectively as desired seemed in question.

Third, though less pressing a challenge than the previous two, would be an effort to intensify thinking about structural and operational adaptations as the startling, technologically driven innovations of recent decades continue. The structure of the Federal Reserve System itself might appear increasingly outdated, as economies and financial markets of regions of the country become more and more interdependent and the operational role of regional banks appears less crucial.

Stephen H. Axilrod worked from 1952 to 1986 at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System in Washington, D.C., rising to Staff Director for Monetary and Financial Policy and Staff Director and Secretary of the Federal Open Market Committee, the Fed’s main monetary policy arm. Since 1986 he has worked in private markets and as a consultant on monetary policy with foreign monetary authorities. He is the author of The Federal Reserve: What Everyone Needs to Know.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Five things you should know about the Fed appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThree Attorneys General are wrongPrepping for tax seasonBring me a scapegoat to destroy: babies, blame, and bargains

Related StoriesThree Attorneys General are wrongPrepping for tax seasonBring me a scapegoat to destroy: babies, blame, and bargains

US Independence Day author Q&A: part three

In honor of Independence Day in the United States, we asked some of our influential American history and politics VSI authors to ask each other some pointed questions related to significant matters in America. Their passionate responses have inspired a four day series leading up to America’s 237th birthday. Today Charles O. Jones, author of The American Presidency: A Very Short Introduction shares his answers. Previously L. Sandy Maisel and Donald A. Ritchie shared their views. Check back tomorrow for Richard M. Valelly’s responses.

Richard M. Valelly (American Politics VSI) asked: Pundits and political scientists seem to fundamentally disagree on how powerful the president is. Pundits remark on the majesty and power of the office; political scientists are struck by how demanding the position is and how hard it is for presidents to make a difference. Yet some political scientists increasingly see a president empowered to act unilaterally. Where are we really in the evolution of the presidency?

Charles O. Jones: The status of any one presidency is explained primarily by the extent to which the incumbent accurately assesses and effectively employs available political capital. As the only term-limited elected officials in Washington, presidents are challenged to lead a government mostly in place and at work when they arrive. Even two-term presidents are among the shortest tenured members of the official Washington community.

Therefore, influencing other power-holders is enhanced or diminished by the incumbent’s demonstrated leadership skills. Presidents can act unilaterally, paying little heed to these others. Doing so may, however, risk reducing future presidential influence, perhaps with little short-term gain and long-term unfortunate repercussions.

So: “Where are we really in the evolution of the presidency?” My opening sentence focuses on “available political capital.” Presidents in the last 25 years have “really” possessed limited political capital by reason of narrow popular vote margins and lack of commanding party control of Congress. Yet presidents of this era (notably Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama) have, on critical issues, overestimated their heft. Consequently, the presidency is in need of more skillful, cross-partisan leadership suited to low- or no-mandate politics. Unilateralism in a separated powers system is not recommended.

L. Sandy Maisel (American Political Parties and Elections VSI) asked: Should political leaders be judged by their ability to achieve compromise solutions to divisive issues or by their willingness to stand on principle, rather than to compromise?

Charles O. Jones: By the Founders’ design, our national political leaders are not typically offered clear choices between principle and compromise. Therefore, judgments of their records based solely on one or the other are mostly inapt. Representational diversity, by form and interests, was locked into the nation’s governmental structure with population featured in the House of Representatives, jurisdictions (states) in the Senate, and a combination in the Electoral College. Furthermore, terms of service are varied, thus likely to affect representation: two years (House), six years staggered (Senate), and four years with a two-term limitation added (president).

This premium placed by the Founders on variable representational bases invites multiple perspectives, principles, and values in lawmaking, implementation, and evaluation. The system design also assured, again intentionally, that no one leader rules all—no kings here. Expectations of leader behaviors are bound to differ, as associated with the purposes and functions of their settings in each institutions. Presidents, cabinet secretaries, House Speakers, floor leaders, and committee chairs have different jobs. And each is affected by actions of the others. Separation of powers systems are, by definition, interdependent. Accordingly, leaders are regularly served menus of issues in various stages of processing.

How then should political leaders be judged in a government like ours? Primarily by their abilities to maximize representation of legitimate interests, to facilitate negotiation among those interests, and to devise strategically sound sequences, revealing of priorities. The House, Senate, presidency, and executive departments and agencies are organized to accomplish these ends. It is the responsibility of leaders to make those bodies work effectively.

Donald A. Ritchie (The US Congress VSI) asked: The US Congress has been called a “broken branch.” If that’s so, whose fault is it: the institution, the political parties, or the voters?

Charles O. Jones: If the answer is: “Congress today is a broken branch,” what exactly is the question? Mostly it appears to be a variation of: “Why isn’t lawmaking working the way I want it to work?” Or: “What has happened to the Congress I once knew?” Either question implies change, which, in turn, suggests shifting political conditions. And sure enough, the so-called “broken branch” today is shaped by very different circumstances than in the past, even the recent past.

If so, perhaps what is “broken” is more aptly reactions and modifications on Capitol Hill to changing political conditions. Rather than assigning fault we might better inquire what are those shifts and how might they be better understood? Paramount among shifts are new versions of split-party arrangements between the president and Congress and the continuity of narrow-margin politics.

Split-party arrangements have been common in the post-World War II period, until 1994 featuring dominance of Democratic congressional majorities with Republican presidents. Following the dramatic 1994 mid-term election, Republican congressional majorities have, in one house or both, served with Democratic presidents for ten years (six with Clinton; four, so far, with Obama). In recent decades, these congressional majorities have been by narrow margins.

Such conditions foster partisanship, whichever party is the majority. Slim margins invite, really demand, party unity. They also offer incentives for congressional policy initiatives in competition with the president and the other party. And one may predict changes in rules as the narrow-margin majority exploits its advantages while the Senate minority resists by forcing super majority votes in that chamber. Not pretty but when was lawmaking a work of art?

Political scientists once favored vigorous two-party competition. Now that conditions promote it, the results are said to have “broken” the branch. Whose at fault? All of the above. It is, however, good to recall representative democracy is not for the weak hearted.

Charles O. Jones is Professor of Political Science Emeritus, University of Wisconsin, Madison, and a nonresident senior fellow, Miller Center for Public Affairs, University of Virginia. A former President of the American Political Science Association and editor of the American Political Science Review, his many books include: The American Presidency: A Very Short Introduction, The Presidency in a Separated System, Clean Air, Clinton and Congress, 1993-1996, and Passages to the Presidency.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook. Read more in the Independence Day Q&A series.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post US Independence Day author Q&A: part three appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesUS Independence Day author Q&A: part twoUS Independence Day author Q&A: part oneTen things you didn’t know about the Battle of Gettysburg

Related StoriesUS Independence Day author Q&A: part twoUS Independence Day author Q&A: part oneTen things you didn’t know about the Battle of Gettysburg

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers