Oxford University Press's Blog, page 930

June 27, 2013

The great quiet

The story of military music is absent from conventional music histories even though it had a vast influence on many aspects of musical life. Bands of music originated in the British military in the eighteenth century among the aristocratic officer class as a form of entertainment and as a means of enhancing the cultural status of that profession. They retained this function throughout the nineteenth century and beyond; by the turn of the twentieth, military music had proliferated in most countries. In Victorian Britain its most visible association was with the new brand of state ceremony and its utilisation to convey the authority of the state both at home and in the vastly expanding empire.

The regimental band retained its importance within the gentlemanly, socially exclusive world of the officers’ mess throughout the nineteenth century and beyond, as illustrated by ‘Bandnight’ (1911), a pen and ink sketch by Lt. P. R. Quayle of the 127th Baluch Light Infantry, then stationed in Poona, India. (Courtesy of the Council of the National Army Museum, London.)

Military music created a massive expansion of the music profession, and the commercial and economic infrastructures on which it relied. The first bands of music were formed from London professional players, but this supply was sufficient only for the small group of elite regiments attached to the royal guards. A new source of players was needed. From the late eighteenth century, thousands of men and boys were recruited to the army and quickly trained as literate instrumentalists by German civilian bandmasters imported for that purpose. Many of these previously untutored army musicians came from the urban and rural dispossessed: those pressed into service and the inhabitants of workhouses, orphanages, and the ‘military schools’ founded to accommodate the sons of soldiers who had fallen in the many wars of the century. Many Victorian musical luminaries were products of this legacy; one such was Sir Arthur Sullivan, son of a military musician who had been recruited from a military orphanage.

The Royal Military School of Music at Kneller Hall, London, was established in 1857 to train a new breed of student musicians, many recruited from schools and orphanages, in response to the proliferation of military bands. The School’s band is shown here in an engraving from The Graphic, 8 September 1894.

There is a mass of evidence about the effect of music on soldiers in fields of conflict. The diaries and journals of ordinary soldiers provide vivid testimony of this, as do the reports of war correspondents. Soldiers would recline exhausted and draw nourishment from the arrangements of the classics and the jaunty and sentimental songs that reminded them of home. Popular songs were also used for marching, and William Howard Russell, the legendary war reporter of The Times, wrote of “how regiments, when fatigued on the march, cheer up at the strains of their band, and dress up, keep step, and walk with animation and vigour when it is playing.” The odd, bitter-sweet juxtaposition of pleasant music and the barely imaginable realities of nineteenth-century warfare provide a surprisingly saddening account of men and boys, a long way from home and persistently conscious of the frailty of their destinies. This was the context for the experience of listening to music.

The band of the 1/24th Regiment of Foot, photographed in 1878 in South Africa, played cheery, morale-boosting melodies as the regiment marched to the killing fields of Zululand; the entire band lost their lives. (By permission of the Regimental Museum of The Royal Welsh, Brecon.)

The Crimean War was the first to be fought under the gaze of the press, and many reporters risked perils not very different from those of the soldiers themselves, who acted out their service amidst the carnage and bloodshed of the Crimea as well as the diseases that ran rampant and which accounted for so many of the casualties. Men would wander well beyond their own unit to the midst of another if it was known to have a good band. The most compelling evidence of the impact of music in fields of conflict is found in accounts of what became known as the “great quiet”. The British command decided to prohibit all bugle calls and music to avoid advertising the position of its troops to the enemy. For months the twenty-five bands of the British army which had sustained the morale of tens of thousands of men in the Crimea were reduced to silence:

The silence and gloom of our camp …[is] very striking. No drum, no bugle call, no music of any kind, is ever heard within our precincts…. Many of our instruments have been placed in store, and the regimental bands are broken up or disorganized…. Judging from one’s own feelings, and from the expressions of those around…the want of music in camp is productive of graver consequences than appear likely to occur at first from such a cause…. It seems to be an error to deprive [the soldiers] of a cheering and wholesome influence at the very time they need it most. The military band is not meant alone for the delectation of garrison towns, or for the pleasure of the officers’ quarters, and the men are fairly entitled to its inspiration during the long and weary march in the enemy’s country, and in the monotony of a standing camp ere beginning a siege.

Any thoughts that this sentiment was exaggerated or even trivial should be abandoned; there is too much evidence to the contrary. The story of the “great quiet” speaks vividly of the power of music and the potency of its effect on the human condition.

Trevor Herbert is Professor of Music at the Open University, and author of Music & the British Military in the Long Nineteenth Century. He has written extensively on the convergence of musical and cultural history.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The great quiet appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesByrd’s reasons to singHappy birthday Mr. OrwellConcerning the cello

Related StoriesByrd’s reasons to singHappy birthday Mr. OrwellConcerning the cello

The realities of spy fiction

When talking about spy fiction, people sometimes confuse verisimilitude and reality. Spy novelists who use the words “friends” and “cousins” to describe our American collaborators are engaging in verbal verisimilitude. When John Le Carré tells us in his latest novel A Delicate Truth that the business of secret intelligence is now being privatized, he’s conveying an important reality.

Yet, what do we mean by reality? Do we mean realism, such as that conveyed in Joseph Conrad’s descriptions of Verloc’s pornography shop in The Secret Agent? Is reality, then, the successful conjuring up of an atmosphere? Or is it revelatory as in A Delicate Truth? Or does it convey human feelings and deeper meanings?

On the latter front, there have been intimations of deficiency. Graham Greene dismissed his own spy fiction as “entertainment”. He wanted us to admire The Power and the Glory and The Heart of the Matter and not The Quiet American or Our Man in Havana. There is an associated idea that a person writes spy novels not to convey deeper truths but because they generate bigger sales and larger advances on royalties. As I know from my own experience, historians who write about spies do get larger advances and easier publishing contracts; my first book, a tome on industrial relations based on my Cambridge PhD, was accepted only on the thirty-second attempt at finding a publisher!

But does its record of easy success mean that spy fiction or spy history can’t message reality? On the contrary, The Quiet American had insight into the frailties of the early 1950s CIA and the untenability of US intervention in Vietnam. Alden Pyle, its protagonist, is a recognizable prototype of the Ivy League “best and brightest” who got America stuck in the Southeast Asian quagmire.

United Nations fact finding. In 1958 a Canadian team surveys the Mekong Delta seeking opportunities for economic development. Western intelligence agencies pursued a less peaceful course.

There is a further issue here. Is high literature more realistic than low literature, does Greene tell us more than, say, Ian Fleming? Arising from this, why are there only two examples of American high spy fiction? These are James Fenimore Cooper, The Spy and Norman Mailer’s Harlot’s Ghost. Over here, we have Joseph Conrad, Erskine Childers, Somerset Maugham, John Buchan, Graham Greene, John Le Carré and a gang of young pretenders.

Also, “hardboiled” as distinct from cerebral detective fiction is an American genre. Perhaps the Americans are insufficiently devious to write good crooked fiction. It was long an article of faith in British intelligence that Americans blundered in practice, too, and had much to learn from us about the art of espionage. Or perhaps their literature led us astray, and they have been better in reality than in fiction.

Let’s have a think, here, about what we mean by fiction. Is it the opposite of truth, or just unrelated to it? Can it have the potency of myth, a narrative that may be true or false and has the ability to create new realities?

CIA director Allen Dulles thought that by massaging the message he could produce a public opinion more favorable to the CIA. Thus he agreed to the commissioning of E. Howard Hunt to write a series of American spy novels that would outshine those of Ian Fleming. The scheme failed because Hunt was a less able writer, and because Dulles had to resign after the Bay of Pigs fiasco, with the CIA now on a downhill trajectory.

Allen Dulles. A lifelong secret agent and director of the CIA, 1953-61, he admired both MI6 and its 007 image, and sought to emulate them.

But the idea is interesting. And in the 1960s the British authorities set out to encourage and facilitate official histories of our intelligence activities, especially in World War II. The idea was the same; prestige enhances one’s standing and one’s budget. Official historians have access to classified records. In this way, their output is reality. Or is it fiction? Discuss and send me your answers sine die, the date when all of us get to see the records.

A couple of writers operated on the interface of fiction and reality. Somerset Maugham spied for us and the Americans against Germany and then the Bolsheviks. With breathtaking audacity, Maugham used as cover for spying his vocation as a writer of short stories about spying. They appeared in his compilation Ashenden in 1928, and contain recognizable characters such as the Czech patriot Emmanuel Voska. Then there’s Compton Mackenzie’s Water on the Brain. Aegean Memories, his first-hand account of secret service in Greece in World War I, had been critical of MI6 and was suppressed in an Official Secrets Act prosecution. Water on the Brain was satire masquerading as fiction in a sweet moment of revenge.

What might follow the rise, fall and obsolescence of the Anglo-American special intelligence relationship — a United Nations solution to truth-seeking, or perhaps something on the European level? In Spies We Trust is based on interviews, documents, and profound research. That makes it reality not fiction, right? What day is it today?

Rhodri Jeffreys-Jones is Emeritus Professor of American History at the University of Edinburgh and has held postdoctoral fellowships at Harvard, the Free University of Berlin, and Toronto. The founder of the Scottish Association for the Study of America, of which is he the current honorary president, he has also published widely on intelligence history, including The CIA and American Democracy (1989) and The FBI: A History (2007). His most recent book, In Spies We Trust: The Story of Western Intelligence, published with OUP in 2013.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) United Nations fact finding at the Mekong Delta © United Nations. Do not reproduce without permission. (2) Portrait of Allen Dulles © The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). Do not reproduce without permission.

The post The realities of spy fiction appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA flag of one’s own? Aimé Césaire between poetry and politicsHappy birthday Mr. OrwellThe case for a European intelligence service with full British participation

Related StoriesA flag of one’s own? Aimé Césaire between poetry and politicsHappy birthday Mr. OrwellThe case for a European intelligence service with full British participation

June 26, 2013

What’s next for same-sex marriage after the U.S. Supreme Court

The same-sex marriage decisions at the Supreme Court on Wednesday represented important wins for same-sex couples, even if the victories were not quite complete. After Wednesday’s rulings, section 3 of the federal Defense of Marriage Act is no longer constitutional, and California’s Proposition 8 has been effectively voided. However, same-sex marriage prohibitions remain in place in other states.

The question now looming for LGBT public interest groups is where to go from here.

The question now looming for LGBT public interest groups is where to go from here.

The decisions would seem to put supporters of same-sex marriage in a difficult position. On the one hand, federal litigation is probably foreclosed for the near future. Despite Justice Scalia’s off-handed remark in his dissent in the DOMA case, U.S. v. Windsor, that the next challenges to state marriage laws would come “maybe next Term,” the litigation process is unlikely to move so quickly. It will probably be years before another test case emerges, and when it comes there is no guarantee that the justices will hand same-sex couples a broad victory.

That said, there is language in Windsor pointing towards a more sweeping decision sometime in the future. Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion remarks on the “personhood and dignity” of gay people, extending themes that Kennedy developed in previous landmark gay rights cases like Romer v. Evans (1996) and Lawrence v. Texas (2003). Once again, Kennedy has established that laws cannot be motivated by a “desire to harm a politically unpopular group.” Quite potentially, the Supreme Court might be persuaded in a future case that state prohibitions of same-sex marriage do just that. But that decision, if it comes, is likely a few years off.

State by state, LGBT public interest groups are also reaching the limits of what they can accomplish through ordinary legislative or judicial means. Even though Proposition 8 has been overturned, judges in thirty other states are still constrained by state constitutional amendments defining marriage as the union of one man and one woman. These amendments also limit state legislative activity. It would seem, then, that the opportunities for supporters of same-sex marriage are rapidly diminishing.

But appearances can be deceiving. The prospects for same-sex marriage in the states seem gloomy only if we think of state constitutional amendments as being more permanent than they really are. The misperception arises because the procedures for amending the federal constitution are very burdensome, requiring the support of two-thirds of Congress and three-quarters of the states. We hardly ever enact federal constitutional amendments, let alone repeal them. We only repealed a federal amendment once, with the Twenty-First Amendment striking down the Eighteenth Amendment’s prohibition of alcohol.

However, state constitutional amendments are not nearly so difficult to enact—or to repeal. In most states, amendments require the support of only a simple majority of citizens after they have been proposed by the state legislature or the citizens directly. The relative ease of the process is what enabled thirty-one states to enact amendments so quickly in the first place.

These same amendments can be overturned just as easily if majorities of the public are willing, and recently support for same-sex marriage has been increasing. Recent polls have consistently placed national public support for same-sex marriage at above 50%. Even more encouraging, the shift in public opinion has translated into victories at the ballot box. This past November, supporters of same-sex marriage won victories in Maine, Maryland, Washington, and Minnesota, the first time that the issue has won popular support in state ballot initiatives.

Of course, there are many states in which same-sex marriage will still lose in a popular vote. It is the public opinion in each state that counts, regardless of how much public opinion nationwide is changing. In many states, support for marriage equality has not come far enough.

But supporters of same-sex marriage would do well to chip away at states in which public opinion has changed. If the amendments in these states are successfully overturned, the victories might create mandates, persuading state legislators or judges to formalize the legalization of same-sex marriage within their borders. As the number of states legalizing same-sex marriage increases, the pressure for other states to follow suit will increase.

Moreover, an implication of Wednesday’s Proposition 8 case, Hollingsworth v. Perry, is that if state governments disapprove of same-sex marriage amendments enacted through ballot initiatives, they might be able to undermine the amendments by refusing to defend them in federal court. It will be interesting to see whether other state governments follow California’s example.

The Supreme Court may not have given same-sex couples the full victory they wanted, but the movement is far from over. The state constitutional amendments that washed over the country in the past decade can be washed away just as quickly, as LGBT public interest groups take advantage of initiative amendment procedures that have previously worked to oppress them. With public opinion now shifting, it is time to turn the tide.

Robert J. Hume is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Fordham University. His new book Courthouse Democracy and Minority Rights: Same-Sex Marriage in the States, is available at Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image via iStockphoto.

The post What’s next for same-sex marriage after the U.S. Supreme Court appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe highest dictionary in the land?Exclusion and the LGBT life courseBeware of gifts near elections: Cyprus and the Eurozone

Related StoriesThe highest dictionary in the land?Exclusion and the LGBT life courseBeware of gifts near elections: Cyprus and the Eurozone

Monthly etymological gleanings for June 2013

One cannot predict which posts will interest the public and which will leave them indifferent. I hoped that my “revolutionary” hypothesis on the origin of Old Nick would result in a tidal wave (title wave, as some of my students write), but it did not produce as much as a ripple, whereas the fairly trivial essay on the letter y aroused a lively discussion. I have heard statements along the same lines from publishers: a book seemingly destined to explode like a bomb falls to the ground without any noise, while an obscure treatise becomes a bestseller. Jack London tells the same story in Martin Eden, which is, in my opinion, his best, and quite undeservedly neglected, novel.

Summer is the time for light-minded pursuits, so today, instead of a regular set of gleanings, I decided to offer our readers a sample of what used to be called “table talk.” Serious answers next time!

Language and war.

Yes, indeed, great wars and conquests have a decisive effect on the spread of languages. The history of Greek, Latin, German, French, and English provides enough evidence of this fact. The decay of prestige is another worthy topic. In the nineteenth-century humanities, one had to use German and, in some areas, French. Nowadays it is English, but one need not ignore other circumstances. Thus, Latin remained the preferred medium of communication among scholars for more than a millennium after the death of the last native speaker of that language. There is always hope.

From my trasher island.

Those who have read the first, delightful editions of H.W. Fowler’s Modern English Usage know that nearly all the examples of bad English he quoted came from newspapers, reports, and other documents of this type, though he was not above castigating Dickens and Thackeray. Reading newspapers, ads, and memos only for grammar, while ignoring (not even noticing) their content, is one of the greatest pleasures of every linguist. I have a sizable file of sentences that make me wonder what their authors were up to and call it trasher island. Here are some “facts on file.”

Will in conditional sentences.

“If you stand to earn some money with an accurate answer, cheerleading becomes much less attractive. And if you will lose real money with an inaccurate answer, you put a higher premium on accuracy” (Bloomberg News). If you stand to earn versus if you will lose: this is puzzling, or a conundrum, as people who think that they know Latin, say. In a conditional clause, will is not needed (“If you call me tomorrow, I’ll try to help you”). “If you will step into the next room, I may be able to help you” means approximately: “If you are so good as to step.…” Hence the much discussed and much abused phrase if you will “with your permission.” Or is will in the sentence given above a typo?

A daring past participle.

“Ended her near-silence about more than a week of massive, violent protests, she said in a prime time TV broadcast….” (New York Times; the reference is to the President of Brazil). This must mean having ended or after ending. With intransitive verbs such constructions are fine (“wounded in the war, he could no longer play the piano”), but a transitive verb is a different matter: compare lost his arm, he could no longer play the piano (obvious nonsense). So why did the two NYT authors write such a strange sentence? Another conundrum.

A controversial plural?

“Patients are what matter, first and foremost. Just as Hippocrates first wrote, thousands of years ago” (CAM, the alumnus magazine of Cambridge University). Even if Hippocrates made such a statement, he made it in Greek, whereas we are interested in the what matter group, which is Modern English. Shouldn’t matter have agreed with its subject what rather than with patients?

The present perfect.

“The contract has been signed a few years ago. It hasn’t been fulfilled yet,” Putin said (The Associated Press). I am sure Putin said it in Russian, so that at some stage an American journalist translated his words into English. Does has been signed go with a few years ago? I have grave doubts on this score.

Another gem from the Associated Press: who versus whom.

“The protests are seen as a display of frustration with Erdogan, whom critics say has become increasingly authoritarian.” It is funnier than usual, for here the verb (say) would not have been able to govern the pronoun.

Pride comes before the fall

Pride before a fall?The adjective proud has undergone a curious development. Below are a few examples parading on a descending scale.

I am often invited to speak on subjects as different as the end of the world and Dickens’s bicentennial. Once an old lady (I could guess her age only from her voice) asked me on the telephone whether I would like to come to their group and speak about the Icelandic sagas (the group’s members were of Norwegian descent). I inquired meekly whether the group would offer me an honorarium. “We are a small but proud society,” was the answer. “Does that mean that you don’t pay your speakers?” “We are a small but proud society,” repeated the lady indignantly and hung up.

Little children constantly ask their parents on what appears to be the slightest provocation: “Are you proud of me?” Isn’t proud too strong a synonym for “pleased, satisfied”?

A local “eatery” near the place where I live “is proud to offer its customers New England coffee,” and at an excellent hotel I read: “Our Sustainability Program is proud to feature fast drying hand dryer in place of paper towels.” Really!

An old chestnut: amount versus number.

Here is at last something on which everybody seems to agree: use amount with uncountable nouns (a great amount of milk) and number with countables (a great number of milk bottles). Everybody, that is, except the speakers, who stubbornly cling to amount in both cases. Undergraduates, the most nonchalant cross-section of the semi-educated population, refuse to follow the rule approved by all grammarians. And Oscar Wilde, a lord of language, as he called himself, spoke about an amount of books and even about a scandalous amount of bachelors in London.

The denouement on a solemn note.

From the editor’s ad in The International Review 5, 1878, p. 701: “Dr. Charles Mackay informs me that the elaborate etymological work upon which he has been engaged for some years back will shortly be published. Its full title will be The Gallic Etymology of the Languages of Western Europe, and more especially of the English and Lowland Scotch, and of their Slang, Cant, and Colloquial Dialects. The work is dedicated by permission to the Prince of Wales, and will be issued in the first instance to subscribers only… The list of subscribers includes three princes, all the universities, many of our nobility, and most of the well-known writers in English literature.” How sad! Mackay, a knowledgeable man and a good popular poet, derived thousands of words from Irish and became the laughing stock of philologists. Advice to subscribers, even if they belong to the quality of the land: look before you leap.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Climber in trouble clinging to a cliff for dear life in The Sierra Nevada Mountains, California. © gregepperson via iStockphoto.

The post Monthly etymological gleanings for June 2013 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMonthly etymology gleanings for January 2013, part 1How come the past of ‘go’ is ‘went?’‘Guests’ and ‘hosts’

Related StoriesMonthly etymology gleanings for January 2013, part 1How come the past of ‘go’ is ‘went?’‘Guests’ and ‘hosts’

A flag of one’s own? Aimé Césaire between poetry and politics

Aimé Césaire (1913 – 2008) has left behind an extraordinary dual legacy as eminent poet and political leader. Several critics have claimed to observe a contradiction between the vehement anti-colonial stance expressed in his writings and his political practice. Criticism has focused on his support for the law of “departmentalization” (which incorporated the French Antilles, along with other overseas territories, as administrative “departments” within the French Republic) and his reluctance to lead his country to political independence. However, this perception of contradiction is misleading. A close reading of his poetic corpus and his published essays, such as the famous Discourse on Colonialism, supports an integrated view of his social thought and political practice.

While Césaire respected the sentiment of “national pride,” he was more deeply committed to the project of restoring “black pride” — an idea that transcends the institution of a modern nation-state. When I interviewed him in Fort-de-France, the city of which he was mayor from 1945 until 1993, the first question he put to me on learning that I was a native of the Caribbean island of Antigua was: “Are Antiguans proud to be black?”

The key to arriving at a holistic view of Césaire’s ideological position is to be found, not only in his espousal of “negritude,” but also in his quest to achieve genuine “decolonization.” By his controversial support of departmental status, Césaire signaled early in his career that true decolonization should embrace not only the political and economic spheres (though he doubted Martinique’s ability to successfully “go it alone,” given the persistence of “neo-colonialist” control of global markets ), but also the domain of cultural values. The leaders of newly created independent African nation-states (such as the Senegalese, Leopold Senghor, his close friend from his student days in Paris; or Sekou Touré of Guinea, whom he celebrated in a lyric poem, “Guinée”) chose to follow the path advocated by Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah in the slogan, “Seek ye first the political kingdom.” Césaire, on the other hand, understood in a very prescient way that “neo-colonialism” meant that economic exploitation invariably persists even after the hoisting of a new national flag.

Decolonization and negritude were inseparable in Césaire’s thinking. Both were ambitious projects for remaking ex-colonial Martinican society by reinstating pride among its people of color. As his signature poem, Cahier d’un retour au pays natal (“Journal of a Homecoming,” in my English rendition) discloses, he saw negritude as an ongoing process of resurrecting a positive racial identity for peoples of African descent in the face of the degradation inflicted on them by European colonial powers. In this regard he shared the insight of the historian and political leader, the Trinidadian Eric Williams, that racism in its New World incarnation had been cooked up by the slave owners as a rationalization for enslavement of Africans. He therefore came to regard the Haitian Revolution, in which the slaves of the wealthy colony of Saint-Domingue (as Haiti was called under colonial French rule) successfully wrested power from their masters, as the historic crucible of negritude. As Césaire puts it in an arresting passage in the Journal, Haiti was the place “where for the first time negritude stood up tall and straight and declared that it believed in its humanity.”

For Césaire, then, negritude, as incarnated in the Haitian revolution, involves adopting a rebellious stance against the dehumanization of blacks. This theme is present in several of his plays, such as A Tempest, which explores the psychological complexity of the relationship between colonizer and colonized. In his brilliant recasting of Shakespeare’s play, the monstrous figure of Caliban is transformed into an articulate, subjugated native who plots a successful rebellion against his repressive master, the European Prospero.

Césaire’s dual agenda was, at bottom, “moral” in conception. His consistent goal, as poet and politician, was to promote genuine equality for the blacks of his homeland in the sphere of public policy no less than in social relations.

During his long service as deputy from Martinique to the French parliament, he acted as moral gadfly by making uncompromising “interventions” in order to ensure that the Antilles, as an “overseas department,” received treatment equal to that of the departments in continental France. He continued to play this role even after his official retirement, most famously in his brush with the former French president, Nicolas Sarkozy: Césaire publicly rebuked him after he made a notorious remark on the benefits of French colonialism. By an ironic twist of fate, Sarkozy eventually made up for his lapse on the occasion of Césaire’s posthumous canonization in the French Panthéon by delivering a laudatory tribute to the great writer and statesman, in which he declared: “To tell the truth, he never ceased to goad France into examining its conscience.” [My translation.]

When I once asked him in a conversation in the mayor’s office what he thought of the radical independence movement (then centered in the sister island of Guadeloupe), he replied: “The French do not want independence.” Since the blacks of the French Caribbean were citizens of France, he was content to re-affirm the preference of the majority to retain their departmental status. For those who deplore this preference, I offer the following challenge: visit a few of the independent mini-states of the Caribbean archipelago and compare their economic and social progress with that of the Martinique bequeathed by the Césairean gadfly.

Gregson Davis is Professor of Classics and Comparative Literature at New York University, where his research focuses on the interpretation of poetic texts in the Greco-Roman as well as Caribbean traditions. He has taught previously at Stanford University, Cornell University, and Duke University. His published work includes a biography of Aimé Césaire (Cambridge University Press, 1997), translations of Césaire’s poetry (Stanford University Press, 1984), and the entry on Césaire in The Oxford Encyclopedia of African Thought, available online at the Oxford African American Studies Center.

The Oxford African American Studies Center combines the authority of carefully edited reference works with sophisticated technology to create the most comprehensive collection of scholarship available online to focus on the lives and events which have shaped African American and African history and culture.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A flag of one’s own? Aimé Césaire between poetry and politics appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHappy birthday Mr. OrwellGoogle: the unique case of the monopolistic search engineOh, I say! Brits win Wimbledon

Related StoriesHappy birthday Mr. OrwellGoogle: the unique case of the monopolistic search engineOh, I say! Brits win Wimbledon

Beware of gifts near elections: Cyprus and the Eurozone

Cyprus was not on the agenda of most analysts as the next plot twist in the Eurozone Sovereign debt saga. Although the island nation has been locked out of international capital markets since May 2011, the government of President Demetris Christophias only asked for support from the Eurogroup on 25 July 2012.

It quickly became clear that the request would not be resolved swiftly. Although Cyprus requested a small amount in absolute values, it was large relative to the size of the economy, and the Cyprus government also seemed reluctant to finalize the agreement. The island’s banking sector, which was far larger that its GDP, also suffered critical losses through its exposure to Greece and the Greek PSI. In addition, the stance of northern European creditor nations was hardening, especially in Germany, where upcoming elections altered the Bailout dynamic. All this combined to delay the resolution of the bailout terms. Nevertheless, on 4 December 2012, the outgoing President Christophias announced that he would be signing a memorandum of understanding. Yet, his term of office expired on 28 February 2013 with no resolution. Facing a large repayment of debt that Cyprus could not afford, the new president, Nicos Anastasiades, flew to Brussels to finalize the agreement on 15 March.

The nature of the agreement thrust Cyprus in the global spotlight thanks to the decision to swap a part of all Cypriot deposits for shares in the country’s troubled financial institutions. The ESM/IMF was willing to fund €10bn out of the €17bn that Cyprus needed. This left the government of Cyprus having to find €7bn to recapitalise its banking sector. Junior bank bondholders were bailed-in, and the remaining €5.8bn needed was to be raised by a “shares-for-deposits” swap on all deposits in all banks, even for insured depositors. Deposits over the insured €100,000 would have 9.9% of deposits converted to shares, with insured depositors also affected with 6.75% of their deposits converted.

The deal was immediately disowned by all when the extent of its unpopularity was known: it failed to pass the Cypriot parliament and caused outcry in the Eurozone. Even leaked IMF meeting notes indicate that executive board members regarded the deal as “unacceptable as it imposed losses on small insured depositors.” While a new deal was being hashed out, the banks remained closed and the Cypriot economy nosedived. By the 25th a new deal was reached and the banks finally opened on the 28 March, after a record twelve-day bank holiday.

The final bailout could be called a success for the Eurozone but a disaster for Cyprus. It still breaks new ground in the Eurozone saga as bank depositors were bailed-in and capital controls were implemented, but it spared insured depositors. The turmoil caused by the bank closure ensured that the amount Cyprus needed increased from €17bn to €20.6bn; an increase equal to 20% of Cypriot GDP. Unlike the original scheme, the two largest banks on the island were bailed-in. The uninsured depositors of Laiki Bank were bailed-in 100% and became shareholders of “bad” Laiki, which would have some non-performing assets. Bank of Cyprus uninsured depositors were also partially bailed-in (currently at 37.5%) and the bank absorbed the insured depositors and good assets of Laiki, as well as the very large liabilities of Laiki towards the ECB.

The Eurogroup insisted that all Greek branches of Cypriot banks were sold to Piraeus Bank in order to prevent contagion. This made Greek depositors exempt from the bail-in, increasing the contribution of Cypriot depositors. Piraeus Bank bought the branches using funds from the Hellenic Financial Stability Fund (HFSF), a Eurogroup funded body set up after the Greek Bailout. Piraeus Bank received the Cypriot branches in Greece at knockdown prices and free of their significant capitalization needs: the large amounts borrowed under the Emergency Liquidity Assistance to fund withdrawals of Greek depositors were transferred to the banking system of Cyprus, aggravating existing liquidity shortages. The deal was so advantageous for Piraeus Bank that it announced a “negative goodwill” of €3.4bn in the first quarter results of 2013. Thus, the Cyprus bailout in effect asked for Eurozone taxpayers’ money, given to Greece under its bailout, to be used in order for a private Greek bank to make large profits.

Yet for the Eurogroup the whole operation can be seen as a success: contagion was prevented, insured depositors were protected, and bond spreads remained stable. In addition, the new deal adheres to German sensitivities prior to elections. Yet the reality is that the Eurozone has emerged weaker from the Cypriot bailout: capital controls in Cyprus mean the Eurozone has violated the free movement of currency between its members, weakening the troubled periphery. The way the bail-in was bungled in practise has led to hundreds of lawsuits at Cypriot district and constitutional courts, and in other jurisdictions, that threaten to derail the resolution of the banks. In Cyprus itself businesses lost their working capital, while capital controls are killing the services sector. Since a cumulative reduction of up to 30% of GDP is probable, debt sustainability assumptions underlying the bailout are unrealistic.

Despite the pressure to make Cypriot debt sustainable, the agreement has insisted on preferential treatment for foreign law sovereign bondholders relative to Bank depositors, local law bondholders and even foreign governments. Local law debt will be restructured with a “voluntary” rollover providing longer maturity or written down through acquisition of government land. The direct loan from the Russian Federation that Cyprus had acquired also had its maturity extended and the interest rate reduced. Yet, foreign law bond holders are to be paid on time and in full. The fact that Eurozone decision makers have preferred to hurt bank depositors and foreign governments rather than attempt to restructure foreign law bonds is extraordinary: that stills seems to be a “bridge to far” for the Eurozone.

Why was the bail-in of depositors chosen as the way to restructure the Cypriot Banking sector? One thing is clear: the blame must be shared by many. The previous government of President Christofias must take the lion’s share: its recalcitrance, its excessive fiscal spending, and its lack of understanding of the mortal effects the Greek PSI had on the Cypriot banking sector were critical errors. The new government of Anastasiades also made mistakes, although its share of the blame is limited, as it was only in power for 15 days prior to the first Eurogroup agreement.

The banking sector and its regulators also failed at a Cypriot and a European level. At a local level, banking was allowed to become far larger than the ability of the island to support it, and many mistakes were made in the Bank restructuring processes. The risky trade in Greek government bonds, helped by Cypriot banks, must be investigated over the morality of the trade, and over possible illegalities. Yet the fact that the Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) of Laiki Bank was allowed to rise at such high levels is in part the responsibility of the ECB that allowed the increasing injections of liquidity in a failed bank.

Part of the blame also belongs to the Eurogroup. The political pressure to make a bail-in of depositors part of the programme led to the Eurogroup’s refusal to assist the two largest banks on the island. Yet without funding for the banking sector, the stability of the economy cannot be guaranteed. Right now Bank of Cyprus might not survive even if a 60% bail-in of its depositors because of the large liabilities towards the ECB which it inherited from Laiki. This prevents the resolution in the banking system. The lack of resolution maintains capital controls and is sending the economy into deep depression, making a second bailout increasingly likely. Cyprus is currently caught in a death spiral and only direct funding for its banking system will stop it tumbling. Unfortunately this is not the end of Cyprus-related twists in the Eurozone story.

Alexander Apostolides is a Lecturer at the European University Cyprus. He is the author of the paper ‘Beware of German gifts near elections: how Cyprus got here and why it is currently more out than in the Eurozone’, which is published in Capital Markets Law Journal.

Capital Markets Law Journal is essential for all serious capital markets practitioners and for academics with an interest in this growing field around the World. It is the first periodical to focus entirely on aspects related to capital markets for lawyers and covers all of the fields within this practice area: Debt; Derivatives; Equity; High Yield Products; Securitisation; and Repackaging. With an international perspective, each issue covers articles and news relevant to the financial centres in the US, Europe and Asia.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Cypriot Flag. By mtrommer, via iStockphoto.

The post Beware of gifts near elections: Cyprus and the Eurozone appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGoogle: the unique case of the monopolistic search enginePlebgateThe highest dictionary in the land?

Related StoriesGoogle: the unique case of the monopolistic search enginePlebgateThe highest dictionary in the land?

June 25, 2013

Byrd’s reasons to sing

The composer William Byrd published the first great English songbook (Psalms, Sonnets and Songs) in 1588. He began his book with an unusual and charming list: “Reasons briefly set down by the author to persuade everyone to learn to sing.”

Byrd’s “reasons to sing” give us a glimpse into everyday musical life in the time of Shakespeare. They reflect some unexpected sides of the composer’s own personality. They also have something to say to music-lovers in the 21st century – whether we enjoy singing in a choir, or with our families, or just in the shower. Here are a few of the items in his list:

“The exercise of singing is delightful to nature, and good to preserve the health of man.”

Byrd wrote elsewhere about his own “natural inclination and love to the art of music, wherein I have spent the better part of my age.” He was born into a musical family. His two brothers Simon and John sang at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. His sister Barbara married a maker of musical instruments and helped run the shop. All this music-making certainly seems to have kept them in good health. The Byrd siblings were a lively clan, constantly embroiled in political intrigues and shady business adventures. William himself lived into his early eighties — no mean feat in the Renaissance — and kept on travelling and writing until his death in 1623. His eldest brother John surpassed him in longevity, living to the age of ninety.

The opening of Byrd’s five-voice mass.

“It is the best means to procure a perfect pronunciation, and to make a good orator.”

“Procure a perfect pronunciation”: say that three times fast! Byrd may have been speaking tongue-in-cheek when he wrote this line, but he knew the real importance of rhetoric and oratory. He worked with the best authors of his day. He set the words of many Elizabethan poets, including Philip Sidney, Walter Raleigh, Edward de Vere, and a host of characters less familiar to modern readers. Byrd was also familiar with the harsher oratory of the law courts, where he spent so many hours defending his own causes. One of his songs features a comic mock-trial scene with the soprano shouting “Oyez, oyez” — the “Hear ye, hear ye” still heard in some courtrooms today.

“It is a knowledge easily taught, and quickly learned, where there is a good master, and an apt scholar.”

Byrd was a famous teacher of music, and apparently an eager one. He complained at one point, rather disarmingly, that his duties in Queen Elizabeth’s royal chapel cut into the time he had set aside for private teaching. He lived long enough to influence two full generations of English musicians. His teaching was immortalized by his student Thomas Morley in the Plain and Easy Introduction to Practical Music (1597). Morley’s book is written as a lively series of musical dialogues. We see “a good master” (who he freely admits is modeled on Byrd), “an apt scholar”, and that mainstay of Socratic-style dialogue, the dim pupil who never quite gets it right.

“It is the only way to know where nature hath bestowed the benefit of a good voice: which gift is so rare as there is not one among a thousand that hath it.”

This songbook was being sold to amateur audiences, but Byrd pulls no punches here. Not even one person in a thousand, he says, has a truly good singing voice — and he goes on to say that “in many, that excellent gift is lost, because they want (i.e. lack) art to express nature.”

“There is not any music of instruments whatsoever comparable to that which is made of the voices of men, where the voices are good, and the same are well sorted and ordered.”

Although Byrd was a keyboard virtuoso who wrote a lot of music for harpsichord and organ, he clearly had a special place in his heart for singing. We’re lucky to have many beautiful performances of his vocal music at our fingertips. Here is the Agnus Dei from his four-part mass, sung (as it was in his own day) by a small group of “good voices . . . well sorted and ordered.”

Click here to view the embedded video.

Byrd leaves us with a memorable couplet:

“Since singing is so good a thing,

I wish all men would learn to sing.”

Kerry McCarthy has taught at Duke University since 2003. She has written widely on the music and culture of the English Renaissance, and her most recent book, Byrd, was published by OUP in 2013. Kerry will give a pre-concert talk about Byrd’s life and musical achievement at a Renaissance Singers concert in London on Saturday, 29 June 2013.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image from Early English Books Online. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post Byrd’s reasons to sing appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesConcerning the celloThe Bible and the American RevolutionThe end of ownership

Related StoriesConcerning the celloThe Bible and the American RevolutionThe end of ownership

Days are long—Life is short

Author Christopher Peterson passed away late last year. As the World Congress on Positive Psychology approaches (Oxford University Press will be at booth 110), we’d like to pay tribute to one of the founders of the field in this brief excerpt from Pursuing the Good Life.

I have spent my days stringing and unstringing my instrument,

while the song I came to sing remains unsung.

—Rabindranath Tagore

I hope that no one thinks that a writer of reflections about the good life (i.e., me) has it all together. Competitive soul that I am, I bet I could trounce most of you who read what I write on formal measures of neuroticism and rumination. As a writer, I try to convey a public persona of being somewhat evolved and somewhat wise. Believe me, it ain’t so.

As much as anyone and maybe more than most, I get mired down in the minutiae and hassles of everyday life. I fret about the ever-growing number of e-mail messages that inhabit my inbox. I worry that people may not like me, even and especially people I don’t like myself. I putter way too much, sometimes spending as much time formatting a scholarly paper as I do researching and writing it. I fill up many of my days doing small things that do not matter. I know it, but sometimes I can’t help myself.

A common inside joke among research psychologists is that we study those topics that we simply do not get. In some cases, this is obvious. Myopic psychologists seem more likely to study vision than their 20-20 colleagues. Out-of-shape psychologists seem more likely to study physical fitness, and unmarried psychologists seem more likely to study marriage.

Following this line of reasoning, are positive psychologists less than positive? Sometimes yes, sometimes no. I could characterize the major players in positive psychology as walking the walk versus talking the talk, but they are my friends and my colleagues, happy or not, and I will respect their privacy. It’s probably enough that I have just outed myself as needing further work.

Indeed, gossip is not my point. Rather, my point is to discuss an enemy of the good life, one that is my particular demon but also one that may plague others: getting mired down in the unpleasant details and demands of everyday life.

Sometimes people are urged to live in the moment. I think this advice needs to be qualified by understanding what the moment entails. To paraphrase Albert Ellis, if the moment in which we live is draped in ought’s and should’s, it is probably better not to live in it.

Everyday life of course poses demands, and I am not saying that we should ignore those we do not like. I am simply saying—to myself, if no one else—to keep the bigger picture in mind. Things not worth doing are not worth doing obsessively.

There must be an ancient Buddhist aphorism that makes my point profoundly, but I’ll just say it bluntly, in plain 21st century Americanese: Don’t sweat the small stuff; and most of it is small stuff.

Days are long. Life is short. Live it well.

In Pursuing the Good Life, one of the founders of positive psychology, Christopher Peterson, offers one hundred bite-sized reflections exploring the many sides of this exciting new field. With the humor, warmth, and wisdom that has made him an award-winning teacher, Peterson takes readers on a lively tour of the sunny side of the psychological street. Christopher Peterson was Professor of Psychology at the University of Michigan. One of the world’s most highly cited research psychologists and a founder of the field of positive psychology, Peterson was best-known for his studies of optimism and character strengths and their relationship to psychological and physical well-being. He was a frequent blogger for Psychology Today, where many of these short essays, including this one, first appeared.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Days are long—Life is short appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow will a changing global landscape affect health care providers?Exclusion and the LGBT life courseMaking sense with data visualisation

Related StoriesHow will a changing global landscape affect health care providers?Exclusion and the LGBT life courseMaking sense with data visualisation

The History of the World: North Korea invades South Korea

25 June 1950

The following is a brief extract from The History of the World: Sixth Edition by J.M. Roberts and O.A. Westad.

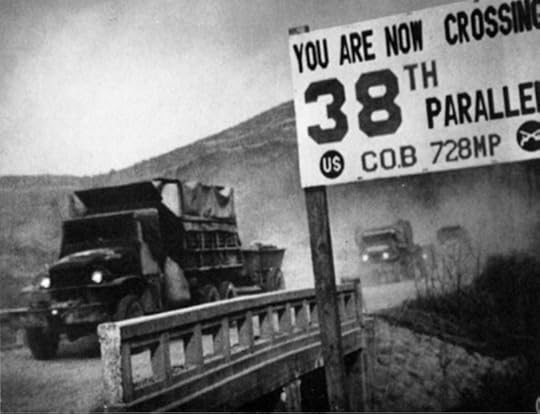

In 1945 Korea had been divided along the 38th parallel, its industrial north being occupied by the Soviets and the agricultural south by the Americans. Korean leaders wanted a quick reunification, but only on their own terms, and the Communists taking power in the north did not see eye to eye with the nationalists whom the Americans supported in the south. With reunification on hold, in 1948 the Americans and the Soviets respectively recognized the governments in their zone as having authority for the whole country. Soviet and American forces both withdrew, but North Korean forces invaded the south in June 1950 with Stalin’s foreknowledge and approval. Within two days President Truman had sent American forces to fight them, acting in the name of the United Nations. The Security Council had voted to resist aggression, and as the Soviets were at that moment boycotting the Council, they could not veto United Nations action.

Crossing the 38th parallel. United Nations forces withdraw from Pyongyang, the North Korean capital. (c) Public Domain, National Archives and Records Administration

The Americans always provided the bulk of the UN forces in Korea, but other nations soon fielded contingents. Within a few months they were operating well north of the 38th parallel. It seemed likely that North Korea would be overthrown. When fighting drew near the Manchurian border, however, Chinese Communist forces intervened. There was now a danger of a much bigger conflict. China was the second largest Communist state in the world, and the largest in terms of population. Behind it stood the USSR; a man could (in theory, at least) walk from Helsinki to Hong Kong without once leaving Communist territory. The threat emerged of direct conflict, possibly with nuclear weapons, between the United States and China…

An armistice was signed in July 1953… estimates suggest the war cost 3 million dead, most of them Korean civilians.

Reprinted from THE HISTORY OF THE WORLD: Sixth Edition by J.M. Roberts and O.A. Westad with permission from Oxford University Press, Inc. Copyright © 2013 by O.A. Westad.

J. M. Roberts CBE died in 2003. He was Warden at Merton College, Oxford University, until his retirement and is widely considered one of the leading historians of his era. He is also renowned as the author and presenter of the BBC TV series ‘The Triumph of the West’ (1985). Odd Arne Westad edited the sixth edition of The History of the World. He is Professor of International History at the London School of Economics. He has published fifteen books on modern and contemporary international history, among them ‘The Global Cold War,’ which won the Bancroft Prize.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The History of the World: North Korea invades South Korea appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe History of the World: Nazis attack the USSR (‘Operation Barbarossa’)The History of the World: Napoleon defeated at WaterlooThe History of the World: Nixon visits Moscow

Related StoriesThe History of the World: Nazis attack the USSR (‘Operation Barbarossa’)The History of the World: Napoleon defeated at WaterlooThe History of the World: Nixon visits Moscow

Happy birthday Mr. Orwell

Dear George (if I may),

Happy Birthday and best wishes on this lovely June morning. I did have a card for you but I didn’t know where to send it, so this will have to do instead. Apparently you’re a bit of a blogger yourself. Pity you’re not down here any more because you’d have plenty to blog about. Every time we hear yet more news of state surveillance and telephone tapping Big Brother is invoked. Mind you, there’s not a single telephone call in Nineteen Eighty-Four.

I hope you don’t mind me calling you ‘George’? We’ve never met and for a man of your class and generation, it might sound a bit pushy. I hope not. You’re known around the world as ‘Orwell’ but I feel I’ve known you for long enough to call you ‘George’ and to write ‘Dear Orwell’, you see, from my point of view, would seem just a little bit public school — as if we’d been to Eton together or something. So, given you don’t like your real name (Eric) and given it can’t be ‘Orwell’, it will have to be ‘George’. Sorry and all that but as you know names matter.

Anyway, I’m sending you this because I have just written a book called George Orwell: English Rebel and byway of a change I thought I’d write this in the first person as a change from all that the third person distancing which controlled our relationship over the past couple of years.

I bought my first ‘Orwell’ at Sussex University Bookshop in 1967. It was a Penguin, three shillings and sixpence, orange and black, and bought because it looked edgy. I’ve still got it — pale and crumbly, worth nothing on eBay but everything to me. The Road to Wigan Pier is a period piece now, but then I suppose we all are.

You were born 110 years ago into a different world. Your father was a lower middle-ranker in the British Raj. Your mother was a memsahib. You were another Bengal baby with a bad chest. No one ever expected you to live to 110 of course — and you didn’t. You died in 1950, age 46, at University College Hospital in Central London, alone in the night, with a massive bleeding of the lung.

Not that you feared dying. You’d been terribly ill for at least two years before hospital – losing weight, high temperatures, rattling lungs, bed, cough, blood, spit, all that — but you’d known you had TB since you were 34 and you must have suspected it long before that. As a young man you lived with tramps on the streets and in the fields and in their many and various ‘kips’. You caught pneumonia at least twice — once when you were down and out in Paris, and the other time as a young school master driving your motorbike without coat or hat from Suffolk to London in the freezing rain. After that, you got shot in Spain, bombed out in London, half drowned in Scotland and driven to the very ends of your life finishing Nineteen Eighty-Four. In Barcelona you and your first wife Eileen narrowly escaped arrest and execution while at the same time trying to save an innocent man from the very same people who were trying to arrest and execute you. This, and chain-smoking, and never enough money, and never a place to call home, and careless of everything except for the work: ‘with George, the work always comes first’, said Eileen.

You’ll be smiling ruefully at my patronizing interest in your health. But please don’t get the impression I feel sorry for you. I never feel that because you never felt sorry for yourself. But I would like to know why you took no interest. I appreciate you were not exactly one for the gym, and would have laughed at the thought of early nights and mineral water, but sometimes you seemed hell bent on self destruction. And it’s not as if you ever got tired of being alive. You enjoyed life’s pleasures, and wrote about them. You got involved in War and Revolution and wrote about that. You thrived on authority (superintendant in the Imperial Police, corporal in the Spanish Militia, sergeant in the Home Guard) but at the same time you resisted it, and distrusted it, and that became a feature of your writing too. Why were you so contrary? Some scholars revel in your ‘contradictions’. But then, some scholars never get further than ‘contradictions’.

You’ll be smiling ruefully at my patronizing interest in your health. But please don’t get the impression I feel sorry for you. I never feel that because you never felt sorry for yourself. But I would like to know why you took no interest. I appreciate you were not exactly one for the gym, and would have laughed at the thought of early nights and mineral water, but sometimes you seemed hell bent on self destruction. And it’s not as if you ever got tired of being alive. You enjoyed life’s pleasures, and wrote about them. You got involved in War and Revolution and wrote about that. You thrived on authority (superintendant in the Imperial Police, corporal in the Spanish Militia, sergeant in the Home Guard) but at the same time you resisted it, and distrusted it, and that became a feature of your writing too. Why were you so contrary? Some scholars revel in your ‘contradictions’. But then, some scholars never get further than ‘contradictions’.

As for your death, how did you deal with that? Your pal Muggeridge reckoned you knew you were a goner. He said he could see it in your face. Tosco Fyvel too said you looked stretched and ‘waxen’. Yet all the while you were sitting up and looking forward. Marrying Sonia from your hospital bed was a huge statement (but of what exactly?) and you went along with her plan to take you to Switzerland. She said she was going to be your nurse and business manager — only your body failed to live up to it. I’d like to know, incidentally, how you were going to be sick man and golden goose both at the same time.

On your 38th birthday Eileen allowed you a ‘birthday treat’, and you spent it inviting an old girlfriend to resume relations. Hmmmm. I have to ask you about that. I do have a special fondness for Eileen, you see, because like me she came from South Shields (did you ever go there?), and because she brought wit and generosity to your life. I like the sound of her. I could go on, but it would be unseemly, would it not, to tell another man how lovely his wife is? But that is what I want to do and there is a reason for it. To be straight, I think you stopped loving her but she did not stop loving you and, although it is never possible to find anything but tragedy in such situations, I am interested in the extent to which the tragedy was all hers.

No, I don’t expect you to answer that. A man who went round telling friends after her death that she was ‘a good old stick’ is not going to talk about such things.

Talking of things not said — where are your letters to Eileen? We have a number of her letters to you, and we have hundreds of letters from you to other people (about 1700 in Davison’s Complete Works), but we only have a solitary letter from you to her. What on earth happened to the rest? It’s implausible to think that that was the only one she kept and it’s equally implausible to think that any one else but you had any say in what happened to the collection. Tell me, did you destroy them because they weren’t worth keeping — or because they were?

How is it ‘up there’ by the way? My idea of heaven is that our greatest journalist goes there and tells us what it’s like. Is it a republic or a monarchy (sounds like a monarchy to me)? Is it boring (like being dead) or full of possibilities (like being alive)? And, just for the record, how was it for a godless Protestant like yourself to find you were wrong on both counts?

The big idea behind my book was to let a historian (me) have a go at someone (you) who had been well turned over by the biographers, the philosophers, the literary types, the political scientists and so on. My argument is that it was your Englishness, not your socialism, or your common sense, or your personal decency, that underpinned your writing and, after a slow start, Englishness provided you with all that a contrarian could want without having to actually surrender to one big idea. I have argued moreover that as an intellectual who was ashamed of intellectuals, Englishness provided you a persona that you might otherwise have lacked and at the same time forced you into the company of the sort of people intellectuals cant stop calling ‘ordinary’. In the end, all this battling made for a man who sought resolution in his writing…

Oh dear, this sounds far too complicated. You’ve probably stopped reading it by now. But to keep going, I have argued that for all your protestations, deep down you were a Tory. Yes, yes, I know you voted Labour and said you were a socialist and so on but I mean ‘Tory’ in the wide philosophical sense which used to include a strong sense of belonging to the people as well It’s true you followed the well worn 1930s path of middle-class men going north to gawp at working-class men. But it’s also true that, given the circumstances, you were not condescending. Rather you tried to write about them with what Edward Garnett called (in relation to D H Lawrence) a ‘hard veracity’ that matched how they worked. Am I right or wrong on this and if wrong, how wrong? And if right, how right? And if mostly right — could you please tell my reviewers?

Sorry to bother you with serious thoughts on your birthday George, but you’ve become quite a famous chap down here. To your certain horror you’ve even become slightly fashionable and it’s only a matter of time before some lithe young man calling himself ‘Orwell’ comes sashaying down the catwalk in bags and cords, thin tash and Tin Tin hair. In a certain light, TB can look like cocaine, and there’s not a day goes by that you are not quoted by some hard-pressed journalist looking for serious moral back up. Did you know they opened the XXX London Olympiad with a pageant of British history that could have been written by you? As someone who sometimes had the truth conveyed to him in dreams, maybe it was written by you? And did you know that last summer there was a move by Joan Bakewell and friends at the BBC to put a statue of you in front of Broadcasting House? Patron Saint of Journalists! Think of that! I’m not sure you’d like it. On the other hand (and one learns with you there’s always another hand) I think it’s a great idea. They say Philip Larkin’s sculptor Martin Jennings might do it. You’ll not remember Larkin. He was the weedy 19 year old who took you for a cheap meal after a talk you’d given to Oxford University English Club in 1942. Like you, he is dead but has never been more alive — and the statue helps. So come on, let’s have a statue: larger than life, scarf and coat, hands on hips, head thrust back — I have a photo of you in the book just like that.

I wonder what are you up to on your birthday? What’s the treat this time? Writing to your old girl friend again? Or a romp round the garden with Richard? Or off to the The Moon Under Water to sink a few pints with your literary mates? Now that you don’t have lungs to worry about, I can see you now scrubbing up for a night on the Celestial Town with Sonia (leaving Eileen at home knitting her brows). Who can say? Not me. I’m only the interpreter. But whatever you are doing George, I hope you are enjoying it. Here’s to you old boy, and all those who make a decent living out of you! Long may you live.

Rob

Robert Colls is Professor of Cultural History at De Montfort University, Leicester. He was born in South Shields and educated at South Shields Grammar Technical School and the universities of Sussex and York. He has held fellowships at the universities of Oxford, Yale, and Dortmund, and with the Leverhulme Trust. He is author of the acclaimed Identity of England, which is also published by Oxford University Press (2002). His new book, George Orwell: English Rebel, will be published in Autumn 2013.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: George Orwell Press Photo. By Branch of the National Union of Journalists (BNUJ). [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Happy birthday Mr. Orwell appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOh, I say! Brits win WimbledonThe Bible and the American RevolutionWhen in Rome, swear as the Romans do

Related StoriesOh, I say! Brits win WimbledonThe Bible and the American RevolutionWhen in Rome, swear as the Romans do

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers