Oxford University Press's Blog, page 933

June 18, 2013

Forging Man of Steel

I like Superman—as a character, as a superhero, as an embodiment of (certain) values. I looked forward to seeing Man of Steel this summer. Although I was disappointed, I’ll start with its strengths. Warning: Spoilers ahead.

I like Superman—as a character, as a superhero, as an embodiment of (certain) values. I looked forward to seeing Man of Steel this summer. Although I was disappointed, I’ll start with its strengths. Warning: Spoilers ahead.

The importance of point-of-view in defining “good” versus “evil” is nicely portrayed. According to my typology of supervillains classification scheme, this incarnation of Zod is a heroic villain. His actions are motivated by—what is to him—an altruistic cause (saving Krypton/Kryptonians). This is made explicit at the beginning of the film, when Zod says to Jor-El (Superman’s father) that he’s taken up the sword against his own people for a greater good. Jor-El, too, could be considered a heroic villain in that he’s done something against Kryptonian law, but is doing so for what he believes is a greater good. It’s not a “black and white” morality tale.

The film (accurately) portrayed the social challenge of being gifted (i.e., “super”). Like many superheroes, gifted children sometimes hide their talents and abilities from others for fear of social ostracism or harassment. In Clark Kent’s case, though, it was because the government might want to “take” him. The young Clark views his budding powers as burdens to be hidden, yet Clark’s father explains that one day he’ll view his abilities as gifts, not burdens.

Amy Adams’ Lois Lane is the best screen version thus far. She’s smart and spunky but not high strung or temperamental. It’s easy to see why Clark would like her (which isn’t true in the other films). She’s an admirable character. Way to go!

The aspects of the film that I didn’t like were, unfortunately, numerous. One fundamental flaw rests on the reason for Jor-El and Lara trying to conceive “naturally” on Krypton: To bring a child into the world that wasn’t pre-conceived or pre-programmed with a destiny. (On this version of Krypton, it seems that children’s DNA is genetically engineered to fill society’s niches—soldier, scientist, etc.—and fetuses are externally incubated.) Yet the young adult Clark discovers a holographic-type projection of his long-dead father, who tells Clark what his destiny is—why he was sent to Earth. He’s “supposed to guide humans, to be a force for good. You will help them to accomplish wonders.” This hypocritical stance about destiny versus free choice is a major plot flaw.

Another plot contradiction is the alien-among-us fear, which drives much of story of Clark’s childhood, but is carelessly thrown off by the end of the film. After downtown Metropolis has been practically laid waste by aliens, no humans seem worried about Superman being an alien, or even that there was an alien battle on Earth.

Finally, the wanton destruction, the endless fight scenes, explosions, buildings collapsing became boring. I couldn’t help but notice that the Daily Planet building took its share of damage, yet by the end of the film, the Planet’s office looks fine. There no sense of the trauma that Metropolis’s citizens experienced since their city was a center ring in which aliens fought. The city is magically clean and rebuilt by the end. We have to suspend disbelief in most superhero films (perhaps Christopher Nolan’s Batman films being the exception), but not this much.

The film was called Man of Steel, but too little of the film was actually about Superman. It was really about Jor-El versus Zod, with Superman acting as proxy for Jor-El. I wanted to see more character development about the adult Clark/Superman. In a film over two hours long, it seemed that his screen time—when he wasn’t in a fight scene—was too brief and his “character development” superficial.

This film contrasts dramatically with the Nolan Batman films, which is ironic because the script was written by the same folks who wrote Batman Begins: Jonathan Nolan and David Goyer. Whereas Batman Begins provides wonderful and psychologically insightful character development, Man of Steel does not.

Robin S. Rosenberg, PhD, ABPP is a clinical psychologist in private practice in San Francisco and Menlo Park, Calif. She often writes about the psychology of superheroes. Her latest books are What Is a Superhero? and Our Superheroes, Ourselves.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only television and film articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Man of Steel movie poster TM & © 2013 WARNER BROS. ENTERTAINMENT INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. TM & © DC COMICS (From DC Entertainment), via manofsteel.warnerbros.com, used for the purposes of illustration.

The post Forging Man of Steel appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA love of superheroesSuperhero essay competition: tell us your favorite superpowerQuickcast – COMIC CON

Related StoriesA love of superheroesSuperhero essay competition: tell us your favorite superpowerQuickcast – COMIC CON

Prepare for the worst

The front cover of Lady Ann Fanshawe’s manuscript recipe book (Wellcome MS 7113). Creative Commons by permission of Wellcome Images.

These days we generally agree that the big medical problems should be left to the professionals. We don’t see ourselves as the appropriate people and our homes as the appropriate places to deal with major injuries, severe illnesses, chronic conditions, and many other significant medical events. This wasn’t the case in seventeenth-century Britain, where domestic healing was the norm and the home was the central place where healing occurred. People prepared to deal with the very worst illnesses and injuries at home.Early modern Britons even kept on hand instructions to make medicines to heal diseases like smallpox and the plague. They thought that householders should have knowledge of how to deal with all eventualities, even life-threatening ailments. In this era the most important site of healing was the home. When you fell ill, you would almost invariably begin your search for recovery at home, and even if you graduated to paying for outside medical care, healers would usually come to your home. The home therefore played an essential role in care, nursing, recovery, and in the end death.

We can get a vivid idea of the range of health problems people thought they might need to face at home from a unique and fascinating type of historical document, the manuscript recipe book. Many people who weren’t in any medical occupation nonetheless traded and collected recipes instructing them in how to make medicines at home. Some then gathered their recipes into handwritten volumes like the one pictured above, which belonged to the Lady Ann Fanshawe, wife of the Royalist, MP, diplomat, and writer Sir Richard Fanshawe. Lady Ann was herself a memoirist. Much like her, most collectors took down medical and cookery recipes as well as those for household supplies like ink, cosmetics, perfumes, and more. Hundreds of manuscript collections survive, though of course they were only compiled by those like Lady Ann with enough wealth to undertake such a project.

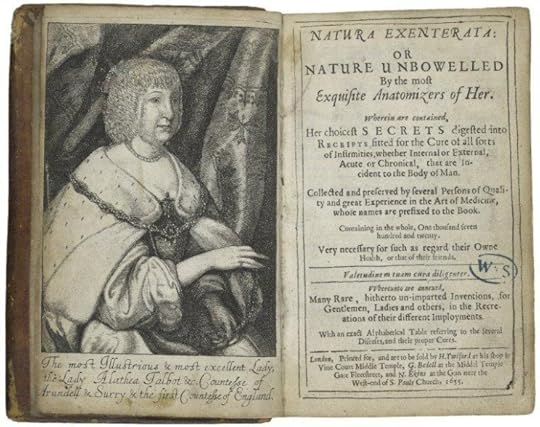

There was also a healthy trade in printed recipe collections. Here is the frontispiece and title page to one from 1655, Natura Exenterata. Creative Commons by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

A woman does the difficult work of distillation. From The accomplished ladies rich closet of rarities (1691). Creative Commons by permission of Wellcome Images.

For an excellent primer on the genre, take a look at Dr. Elaine Leong’s introduction to the collection at the Folger Shakespeare Library and The Recipes Project, a multi-contributor blog devoted to the subject. The Wellcome Library has digitised dozens and dozens of collections. I would urge anyone interested in them to take a look!Medical recipes in these manuscripts run the gamut from simple, single-substance medicines (like one using just sheep’s skin) to complex concoctions with exotic and expensive ingredients. For example, another asks for unicorn horn and bezoar stone (a stone found in the digestive systems of animals and reputed to be a powerful poison antidote). Recipes could also be highly complex to follow. For instance, many involve distillation, an art requiring specialized training and equipment.

These collections were filled with directions for making medicines to use in the home, and they therefore tell us what compilers thought they might need to heal there. Domestic healers collected recipes for a broad array of ailments, including life-threatening ones. Clearly, they thought they might have to manage severe illnesses and injuries at home. Let’s look at a few examples.

Recipes for plague preventatives and cures are very common, both in print and manuscript collections. The title of this one from a collection owned by Mrs Anne Brumwich and Rhoda Hussey (wife of Baron Ferdinando Fairfax), claims that it was used to “help 600 in York,” and that “in one house where 8 were infected 2 of them drunk of it and lived, the others would not and died.” The recipe instructs readers in concocting a tisane from rue, marigold, featherfew, burnet, sorrel, and dragon root. These were all ingredients easily available from gardens or growing in the wild. Then sugar and a poison antidote (mithridate) are added. Both of these were available in apothecaries’ shops. This was an easy recipe to follow, and it promised a powerful cure for one of the diseases that most terrified people. It’s easy to see why someone might have added it to their collection.

“An excellent recipe for the plague.” From Anne Brumwich and others, Booke of Receipts, Wellcome MS 160, fol. 58r. Creative Commons by permission of the Wellcome Library.

Rickets is another disease frequently addressed in manuscript recipe collections. We know rickets as a deficiency disease that remains a scourge of children in developing nations, but seventeenth-century people had no knowledge of vitamins or other modern nutritional concepts. They did, however, see rickets as a debilitating, indeed deadly, disease. The London Bills of Mortality, which listed causes of death in the capital, indicate particular prevalence in the seventeenth century. They record hundreds of deaths from the disease. Recipe collections show great fear of it; many contain multiple, often highly complex directions for treating rickets in children.

A rickets medicine. From the Lady Ann Fanshaw’s collection, Wellcome MS 7113, fol. 111r. Creative Commons by permission of the Wellcome Library.

This recipe from Lady Ann Fanshawe’s collection, attributed to Mrs Price, gives instructions for making a topical medicine and applying it to a child’s body. It’s another simple recipe, one we can easily imagine making in a seventeenth-century home. It asks for calves’ (“neats”) feet, some common plants, and wine, all prepared with some simple cooking procedures. It then tells us how to apply the medicine by rubbing it upwards on the child’s back from the backside to the lower torso, on the back of the thighs and calves, and on the wrists. Finally, you swathe the child’s wrists and ankles. Again, we can imagine why this would have appealed to a collector. Rickets was another terrifying disease, and this recipe offered parents a cheap and easy cure, guiding them through the entire process of preparation and application. The certainty of such a recipe, with the endorsement that came with its attribution, must have been comforting.

From our point of view it’s unlikely that these medicines could have done much for the ill. Indeed, it can be quite distressing to imagine what our own prospects and experiences would have been, long before (for instance) reliable anaesthetics or knowledge of antibiotics. Early modern people did not take a resigned attitude towards the dangers of their world, however. Nor were they entirely dependant on medical practitioners. They stockpiled directions for homemade cures for the full range of injuries and illnesses, right up to the deadliest and most dangerous.

DISCLAIMER: This post discusses medicines strictly in a historical context. It does not endorse the use of these medicines in any way. It should not be used as healthcare advice.

Seth Stein LeJacq is a PhD candidate in the Department of the History of Medicine at the Johns Hopkins University. His dissertation research deals with the history of the Royal Navy during the Age of Sail. His essay “The Bounds of Domestic Healing: Medical Recipes, Storytelling and Surgery in Early Modern England” in the Social History of Medicine won the Roy Porter Student Prize Essay 2013.

Social History of Medicine is concerned with all aspects of health, illness, and medical treatment in the past. It is committed to publishing work on the social history of medicine from a variety of disciplines. The journal offers its readers substantive and lively articles on a variety of themes, critical assessments of archives and sources, conference reports, up-to-date information on research in progress, a discussion point on topics of current controversy and concern, review articles, and wide-ranging book reviews.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Prepare for the worst appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe search for ‘folk music’ in art musicThe case for a European intelligence service with full British participationPlebgate

Related StoriesThe search for ‘folk music’ in art musicThe case for a European intelligence service with full British participationPlebgate

The History of the World: Napoleon defeated at Waterloo

18 June 1815

The following is a brief extract from The History of the World: Sixth Edition by J.M. Roberts and O.A. Westad.

In the end, though the dynasty Napoleon hoped to found and the empire he set up both proved ephemeral, his work was of great importance. He unlocked reserves of energy in other countries just as the Revolution had unlocked them in France, and afterwards they could never be quite shut up again. He ensured the legacy of the Revolution its maximum effect, and this was his greatest achievement, whether he desired it or not.

Napoleonic Europe (c) Helicon Publishing Ltd

His unconditional abdication in 1814 was not quite the end of the story. Just under a year later the emperor returned to France from Elba, where he had lived in a pensioned exile, and the restored Bourbon regime crumbled at a touch. The allies none the less determined to overthrow him, for he had frightened them too much in the past. Napoleon’s attempt to anticipate the gathering of overwhelming forces against him came to an end at Waterloo, on 18 June 1815, when the threat of a revived French empire was destroyed by the Anglo-Belgian and Prussian armies. This time the victors sent him to St Helena, thousands of miles away in the South Atlantic, where he died in 1821. The fright that he had given them strengthened their determination to make a peace that would avoid any danger of a repetition of the quarter century of almost continuous war which Europe had undergone in the wake of the Revolution. Thus Napoleon still shaped the map of Europe, not only by the changes he had made in it, but also by the fear France had inspired under his leadership.

Reprinted from THE HISTORY OF THE WORLD: Sixth Edition by J.M. Roberts and O.A. Westad with permission from Oxford University Press, Inc. Copyright © 2013 by O.A. Westad.

J. M. Roberts CBE died in 2003. He was Warden at Merton College, Oxford University, until his retirement and is widely considered one of the leading historians of his era. He is also renowned as the author and presenter of the BBC TV series ‘The Triumph of the West’ (1985). Odd Arne Westad edited the sixth edition of The History of the World. He is Professor of International History at the London School of Economics. He has published fifteen books on modern and contemporary international history, among them ‘The Global Cold War,’ which won the Bancroft Prize.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The History of the World: Napoleon defeated at Waterloo appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesNapoleon defeated at the Battle of WaterlooThe History of the World: Nixon visits MoscowThe History of the World: Israel becomes a state

Related StoriesNapoleon defeated at the Battle of WaterlooThe History of the World: Nixon visits MoscowThe History of the World: Israel becomes a state

The search for ‘folk music’ in art music

Writing about the perceptions and contexts for music from the Haná region in Moravia in the most recent volume of Early Music got me thinking more broadly about the subject of ‘folk music’ or rustic music of various types, and the emphasis and value frequently placed upon it in the context of art music. In particular, I started to think again about Bedřich Smetana (1824–84). The very concept of ‘folk music’ owes its origins to late enlightenment thinkers, especially Johann Gottfried Herder’s use of ‘Volkslied’ in 1771. Even then, Herder accompanied his discussion with a grovelling apology to the reader for even having addressed the topic of peasant music at all. In recent years, Dave Harker and Matthew Gelbert, among others, have argued that the concept of ‘folk music’ is essentially a bourgeois one (an observation of peasant music made by the educated classes).

Whatever name we would like to give to peasant music (which frequently carries a similar social connotation as ‘folk music’), the recreational music-making of ordinary Europeans found its way, by one means or another, into much art music of the past 500 years or more. Why do musicians find so much value in peasant music? How and why did this happen? In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the art of performing included being able to create something new from older materials. Examples include Diego Ortiz’s Tratado de glosas (1565), the English school of playing ‘divisions’ upon popular airs or basses, the elaborated Lutheran hymn tunes in Bach’s chorale preludes, and the tradition of variation pieces. The reason for their popularity is pretty straightforward, given the appeal of combining both the familiar and the new; but where this becomes even more mysterious is the role of the (perceived) national origins of these melodies in both perpetuating and understanding the desire to find belonging (usually one’s own ‘people’) in the context of music.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The quest to identify ‘national’ traits in music has been little short of an obsession for historians of various sorts since the early nineteenth century, and in some ways before. Why is this so important? For many historians, finding local or national traditional music in the context of art music is similar to looking upon an ancient monument in a town or city square—it inscribes the past onto the present and ties those who identify the melody as ‘theirs’ to both a physical place and a continuing place in history. This is a very different phenomenon to the performance-based music I mentioned earlier, which were part of a musical narrative, rather than a regional or national one.

Historians tend to point to Smetana as the godfather of modern Czech music, but he represents a fundamental but overlooked transformation in how peasant music (or rather an evocation of peasant music) appears in art music. Typically seventeenth and eighteenth century rural musicians, steeped in Italian repertoire and genres, brought their experience to courts in provincial towns as well as major cities, including Prague, Vienna, Paris, London, and Dresden. Of course those rural musical experiences became part of their sound world, albeit unconsciously; that is, the sounds of village life were deliberately avoided by musicians who, in Geoff Chew’s words, sought to be ‘ersatz Italians’ at court. When the Moravian composer and musician Gottfried Finger (c.1655–1730) arrived in London in the 1680s he was amazed to find that ‘the Italian style is but lately naturaliz’d in England’—it had long been the mainstay of most musicians in central Europe. Musicians in the Czech lands also followed this rural-to-urban pattern. However, by the age of Smetana, the situation had reversed; now it was urban composers going to the countryside in search of authentic ‘Czechness’. Smetana, raised in a bourgeois environment, only learned Czech as an adult and had to turn to the countryside to imbue his music with ‘Czechness’.

Seventeenth and eighteenth-century evocations of peasant life followed two basic paths: to be evoked at court as an object of ridicule or humour (Biber’s Battalia is a good example of this, composed for Salzburg Carnival in 1673), or slightly more sympathetic readings by travelling priests, empathising with the sufferings of peasantry more generally. Smetana’s peasants in The Bartered Bride (Prodaná nevěsta), for example, never encounter their social betters (there are no Habsburg administrators or lords in the opera) or any signs of the toils of rural life, but live in a post-Enlightenment world of rural idyll, where they are to be admired for their rustic earnestness and simplicity. Even in eighteenth-century Czech theatrical works, which admitted the reality of Habsburg political rule, there was at least a nod to the difficulties of peasant life.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Nevertheless, Smetana is rather careful in how he integrates folk elements into the score of The Bartered Bride. They generally work along the ‘monument’ model I mentioned above: while folk dances are not part of the opera’s main musical vocabulary, they serve as a monument upon which the peasant characters see their history written (see the furiant dance in The Bartered Bride). The presence of folk elements in this context serves the characters in the opera as well as some of the audience, so that both characters and Czech audiences could identify and experience a sense of belonging. It is a clever device of the composer to portray several kinds of unity simultaneously, and it is critical to note that folk elements were incorporated into all ensemble pieces. Finally, it may seen curious that Smetana’s opera does not challenge the social or political situations of its central characters (a little surprising given Smetana’s political activism in the 1848 Prague uprising), but perhaps the composer aimed to redeem their circumstances through the beauty of a modern, cosmopolitan, and sophisticated musical language. Take, for instance, the moment when Jeník has just agreed to barter his future bride and confesses his unwavering love for her (sung here by the magnificent Slovak tenor Peter Dvorsky).

Click here to view the embedded video.

Even though the revolution of 1848 had failed to liberate the Czech lands from Austria, Smetana could offer a kind of remedy—a fairy-tale picture of idealised unity and freedom—on the stage of Prague’s Provisional Theatre. This interpretation also helps account for the total absence of the Austrian Empire in the story.

Dr Robert G. Rawson is Senior Lecturer and Director of Early Music Ensemble in the Department of Music and Performing Arts at Canterbury Christ Church University. He is the author of “Courtly contexts for Moravian Hanák music in the 17th and 18th centuries” in the latest issue of Early Music, which is available to read for free for a limited time.

Early Music is a stimulating and richly illustrated journal, and is unrivalled in its field. Founded in 1973, it remains the journal for anyone interested in early music and how it is being interpreted today. Contributions from scholars and performers on international standing explore every aspect of earlier musical repertoires, present vital new evidence for our understanding of the music of the past, and tackle controversial issues of performance practice.

The post The search for ‘folk music’ in art music appeared first on OUPblog.

June 17, 2013

10 Questions for Domenica Ruta

Each summer, Oxford University Press USA and Bryant Park in New York City partner for their summer reading series Word for Word Book Club. The Bryant Park Reading Room offers free copies of book club selections while supply lasts, compliments of Oxford University Press, and guest speakers lead the group in discussion. On Tuesday 18 June 2013, author Domenica Ruta leads a discussion on The Turn of the Screw by Henry James.

What was your inspiration for this book?

The book I chose for the book club? Simple – I wanted fun but stimulating summer reading. A ghost story novella by James met the criteria perfectly.

Domenica Ruta. Photo by Meredith Zinner.

For my book? A lifetime of beauty and pain only makes sense to me after it has been distilled into sentences. I had to write this book in order to move on and write other things, like my novel.

Where do you do your best writing?

Honestly…in bed. I know it’s bad for every single muscle and joint in my body. I am going to make some osteopath a very rich man.

Which author do you wish had been your 7th grade English teacher?

My seventh grade English teacher was execrable. Almost anyone with basic literacy could have improved upon her so-called lessons. I like to imagine Joseph Campbell coming in to do guest lectures on mythology. Seventh graders are perfectly located in intellectual time to be transformed by something like that – one foot still in childhood, where magical stories still have power, and one foot in the complicated world of adulthood, where metaphors can be analyzed for greater meaning.

What is your secret talent?

I am pretty good at guessing what mix of breeds make up a mutt dog.

What is your favorite book?

I cannot, will not, answer that question. I love too many too much.

Who reads your first draft?

NO ONE! My first drafts are hideous, putrid, bloody, mangled beasts. It is immoral to expose anyone to something so ugly. My seventh or eight drafts go to my best friend and best reader, novelist/screenwriter Brian McGreevy.

Do you prefer writing on a computer or longhand?

I do both. Different energy fuels each process, and so there are times when longhand makes the most sense, and times when I need to type.

What book are you currently reading? (Old school or e-Reader?)

I am just finishing a brilliant little monograph by Marie-Louise Von Franz, a disciple of Jung, called The Cat, about this wonderful Romanian folk tale. Also reading Daniel Berrigan’s Ezekiel – a brilliant and disquieting alchemy of poetry, politics, biblical exegesis, rant, and rally. I’m also reading a forthcoming memoir by Nicole Kear called Now I See You. And of course re-reading Turn of the Screw.

What word or punctuation mark are you most guilty of overusing?

I refuse to limit myself in any way when I write. (Remember what I said about horrible first drafts?) I use any color on the palette I want. If it turns out ugly, I just delete it. Guilt is a waste of time.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you be?

A figure skater. A veterinarian. A radical eco-activist. Ideally, all three.

Did you have an “a-ha!” moment that made you want to be a writer?

Read chapter four of my memoir for the answer to that.

Do you read your books after they’ve been published?

I just recently published my first book and I’m in no hurry to reread it.

Domenica Ruta was born and raised in Danvers, Massachusetts. She is a graduate of Oberlin College and holds an MFA from the Michener Center for Writers at the University of Texas at Austin. She was a finalist for the Keene Prize for Literature and has been awarded residencies at Yaddo, the MacDowell Colony, the Blue Mountain Center, Jentel, and Hedgebrook. Her memoir With or Without You was published by Spiegel & Grau, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, in February.

Read previous interviews with Word for Word Book Club guest speakers.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics onTwitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post 10 Questions for Domenica Ruta appeared first on OUPblog.

The evolution of language and society

We might have grown skeptical about our cultural legacy, but it is quite natural for us to assume that our own cognitive theories are the latest word when compared with those of our predecessors. Yet in some areas, the questions we are now asking are not too different from those posed some two-three centuries ago, if not earlier.

One of the most topical questions in today’s cognitive science is the precise role of language in the brain and in human perception. Further disciplines, such as anthropology and evolutionary biology, are concerned with the emergence of language: How is it that homo sapiens is the only species possessing such a complex syntactic and sematic tool as human language? What is the relationship between human language and animal communication? Could there be any bridge between them, or are they of categorically different orders, as seems to be suggested by Noam Chomsky’s views?

Such questions stood at the very centre of a fascinating debate in eighteenth-century Europe. From Riga to Glasgow and from Berlin down to Naples, Enlightenment authors asked themselves how language could have evolved among initially animal-like human beings. Some of them suggested some continuities between bestial and human communication, though most thinkers pointed to a strict barrier separating human language from vocal and gestural exchange among animals. In broad lines, this period witnessed a transition from an earlier theory of language, which saw our words as mirroring self-standing ideas, to the modern notion that signs are precisely what enables us to form our ideas in the first place. Such signs had, however, to be artificially crafted by human beings themselves; after all, natural sounds and gestures are also used by animals.

According to various eighteenth-century thinkers, this transition from natural communication to artificial or arbitrary signs was the prerequisite for the creation of complex human interrelations and mutual commitments — in short, the basis for the creation of human society as we know it, with its political structures, economic relations, and artistic endeavours. In this sense, the language debates in eighteenth-century Europe highlighted a crucial problem in Enlightenment thought: how to think of the transition from a natural form of life (frequently conceptualized as a ‘state of nature’) to an artificial or man-made social condition (usually referred to as ‘civil society’). Language was a much more significant topic in Enlightenment thought than hitherto suggested.

According to various eighteenth-century thinkers, this transition from natural communication to artificial or arbitrary signs was the prerequisite for the creation of complex human interrelations and mutual commitments — in short, the basis for the creation of human society as we know it, with its political structures, economic relations, and artistic endeavours. In this sense, the language debates in eighteenth-century Europe highlighted a crucial problem in Enlightenment thought: how to think of the transition from a natural form of life (frequently conceptualized as a ‘state of nature’) to an artificial or man-made social condition (usually referred to as ‘civil society’). Language was a much more significant topic in Enlightenment thought than hitherto suggested.

Furthermore, the idea that all distinctive forms of human life are based on artificial signs has been regarded as a main tenet of the Counter-Enlightenment, a relativistic and largely conservative movement which Isaiah Berlin contrasted to a universalistic French Enlightenment. By contrast, that awareness of the historicity and linguistic rootedness of life was a mainstream Enlightenment notion.

This last point means that even if the eighteenth-century discussions of language and mind were quite similar to ours, particular nuances and approaches were moulded by contemporary concerns and contexts. The open and malleable character of the eighteenth-century Republic of Letters is found in a wide variety of authors: Leibniz, Wolff, Condillac, Rousseau, Michaelis, and Herder, among others. The language debates demonstrate that German theories of culture and language were not merely a rejection of French ideas. New notions of the genius of language and its role in cognition were constructed through a complex interaction with cross-European currents, especially via the prize contests at the Berlin Academy.

Avi Lifschitz is Lecturer in Early Modern European History at University College London (UCL); in 2012/13 he is Research Fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study (Wissenschaftskolleg) in Berlin. He is the author of Language and Enlightenment: The Berlin Debates of the Eighteenth Century, available in print from Oxford University Press and online from Oxford Scholarship Online, and co-editor of Epicurus in the Enlightenment (2009).

Oxford Scholarship Online (OSO) is a vast and rapidly-expanding research library. Launched in 2003 with four subject modules, Oxford Scholarship Online is now available in 20 subject areas and has grown to be one of the leading academic research resources in the world. Oxford Scholarship Online offers full-text access to academic monographs from key disciplines in the humanities, social sciences, science, medicine, and law, providing quick and easy access to award-winning Oxford University Press scholarship.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Portrait of Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716), German philosopher, circa 1700, by Christoph Bernhard Francke. Herzog-Anton-Ulrich-Museum, Braunschweig. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The evolution of language and society appeared first on OUPblog.

How can you reduce pain during a hospital stay?

Too often patients feel like they’re in the passenger seat when entering the hospital. Even in the best of circumstances — such as planned admissions — patients often don’t feel in control of their own care.

Image credit: Photo by Jose Goulao, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

One of the most unnecessary issues facing patients when they enter the hospital is untreated (or undertreated) pain. Often the focus of the medical team is to treat a condition, and controlling a patient’s pain comes second. Fortunately, this doesn’t need to be the situation. Here are a few tips for patients to ensure that their pain does not go overlooked:Let someone know if you are in pain. This may seem obvious, but patients often hesitate to question their doctor. Pain control during your hospital stay is not a luxury, and you need to know you have a right to pain control during your stay. If your doctor or nurse is not answering your questions regarding pain, ask to see pain specialist who will likely address your concerns as well as the concerns of the doctors and nurses taking care of you. Unfortunately when it comes to treating pain, not all doctors are trained equally.

Have a family member or good friend to act as your advocate. Have this individual get involved in your medical care and act on your behalf during your hospitalization.

Search for the right hospital for your medical condition. People end up at hospitals for a variety of reasons, but which hospital you go to for your care can make all of the difference. There are several websites that rate hospitals including Hospital Compare, HealthGrades, US News & World Report, and Consumer Reports. Many of these sites allow you to compare hospitals on a variety of criteria, including death rates for a variety of conditions — from heart attacks to pneumonia to surgeries. Hospital Compare, a website provided by the Department of Health and Human Services, even allows you to see how patients felt about how their pain was treated during their stay.

Ask questions. Many people are afraid to question their nurses and doctors. Don’t be. If a medication looks new or different, ask what it is and what it is for. As long as you are polite and respectful, your request should be met with acceptance. If you don’t understand something, always question about it. Be assertive.

Keep a notebook during your hospital stay, and know your medications and allergies. Record your daily progress, pain levels, medication names and dosages, procedures, treatments, and the names and contact information of your medical team. This way you know what is working well for you pain. Also take notes on conversations with doctors and nurses. Carry the most up-to-date list of your allergies with you, along with another list that contains information on all medications you are taking and the dosages.

Meet with your doctors and nurses. Ask your loved one to join you during doctors’ rounds so he or she can also make a list and help you go through your checklist. It’s handy to have someone there to ask questions you may have forgotten. Have your notebook handy. Prepare questions ahead of time about your diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Show appreciation to your primary nurse. The more good will you express to this professional, the more attention you will receive. More attention translates to the probability of fewer errors.

Avoid medical errors. In 1999, the Institute of Medicine estimated that between 44,000 and 98,000 Americans die each year in hospitals due to medical errors. Medication errors are among the most common medical errors, harming at least 1.5 million people every year. Write down your medications and dosages. List what the medication looks like, the shape and color of any pills, and the names on the labels of bottles or IV bags. Holidays, weekends, and nights have higher likelihood of medical errors, so ask your advocate to be with you as much as possible during these times to help avoid medical errors.

Once recovered, leave the hospital as soon as medically possible. While a hospital is the ideal place when you need lifesaving care, it can also create the perfect storm of risks to your health. Hospital-acquired infections, deadly blood clots, falls, and many other “complications” can result from your hospital stay. Every day that you stay in the hospital unnecessarily exposes you to these risks. Ask every person who comes in contact with you, including the physicians and nurses, to wash their hands or put on a fresh pair of disposable gloves before touching you.

Dr. Anita Gupta is a Board Certified Anesthesiologist, Pain Specialist, Pharmacist & Editor. She is an awarding winning physician and is currently an Associate Professor and Medical Director at Drexel College of Medicine in the Division of Pain Medicine in the Department of Anesthesiology in Philadelphia, PA. She has completed the Wharton Total Leadership Program, an active member of the World Health Organization, founder of Women in Medicine, and has been featured on NBC for health topics related to treating pain. She has been a continuous recipient of the National Patients and Compassionate Physician Choice Award from 2010 to 2012, and author of top selling textbooks, Interventional Pain Medicine and Pharmacology in Anesthesia Practice. She also completed the competitive media and medical advocacy fellowship with the Mayday Foundation in Washington DC.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post How can you reduce pain during a hospital stay? appeared first on OUPblog.

Drone killings

Targeted killing by drones (using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV) or Unmanned Combat Aircraft Systems (UCAS) as weapon platforms) has become an increasingly debated subject. Criticism is not only directed against its overall legality and legitimacy, but also its negative impact on the theatre state as a sovereign state in cases of extraterritorial strikes, a potential lack of efficiency, and a growing uneasiness with its morality. It seems there has been a change in how targeted killing is viewed. Apart from a growing discomfort with civilian ‘collateral’ casualties, there is growing concern about its effectiveness and the acceptance of targeted killing as a new form of warfare. Ben Emmerson, the newly appointed UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and Counterterrorism, has called for more transparency and accountability when employing this form of warfare.

Drones protest at General Atomics in San Diego by Steve Rhodes,CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

Targeted killing has direct implications for the morality of armed conflict and combat. Evolving drone technology arguably removes the soldier from the actual battlefield and with it the intimacy of war. UAV technology has created a mechanical and moral distance between the operator and his ‘target’. Targeted killings may have removed any remnants of the ‘humanity of combat’. Such a dehumanizing distance between the protagonists of this new form of armed conflict, asymmetric in terms of weapon technologies and capabilities, has led to a growing criticism of the Obama Administration’s use of drones. Keith Shurtleff, the US Army Chaplain and military ethics teacher, aptly summarized this concern “that as war becomes safer and easier, as soldiers are removed from the horrors of war and see the enemy not as humans but as blips on a screen, there is very real danger of losing the deterrent that such horrors provide.”

Linked to these emerging morality concerns is a growing debate in regard to targeting efficiency: whether target elimination is indeed as efficient as has been claimed, and whether the rising numbers of civilian ‘collateral’ casualties during combat, among the affected civilian populations in Pakistan has a negative impact on antiterrorism and counterinsurgency campaigns. The number of American drone strikes in Pakistan has significantly increased under Obama, since he took office in 2009: “Estimates state that while there were 52 such strikes during George W Bush’s time, this number has risen to 282 over the past three and a half years.” While the Obama Administration maintains that its drone program was largely successful in terms of efficiency rates and low civilian ‘collateral’ casualties, new reports show the opposite. The Bureau of Investigative Journalism (TBIJ) reported “that from June 2004 through mid-September 2012, available data indicate that drone strikes killed 2,562-3,325 people in Pakistan, of whom 474-881 were civilians, including 176 children. TBIJ reports that these strikes also injured additional 1,228 – 1,362 individuals,” which would amount to a ‘collateral’ rate of 20 percent.

Whether such a figure alone constitutes violations of the principles of distinction and proportionality of the Law of Armed Conflict, and therefore constitutes possible war crimes, has yet to be seen. A critical high profile joint report by Stanford /NYU report, Living Under Drones, which was released last autumn, alleges that there was a lack of effectiveness when targeting leaders and commanders of Taliban and other affiliated forces. The report calls for a careful re-evaluation of the current use of US targeted killing and drone strikes. These findings contradict any policy announcement by the US government. The casualty figures from the above TBIJ report have already found their way into global public debate. Together with another report by Columbia University, which investigated the human cost of drone strikes, and the UN’s decision to embark on an official inquiry into the use of drones, the official US policy announcement that drone strikes constituted “a surgically precise and effective tool that makes the U.S. safer” is in serious doubt. Moreover, this critique already takes into account that the US has a right to defend itself against Al Qaeda, and therefore the United States is in an armed conflict with a non-state actor. How much harder would it be to justify such ineffective strikes under the alternative non-combat paradigm of law enforcement?

The repercussions of the increasing reliance on drones for executing enemies abroad has led an increase in anti-US hostility, possibly swelled the numbers of the Taliban and other affiliated groups in the region, and led to open criticism by its ally in the region, Pakistan. The Obama Administration has not been taken Such ‘collateral damage’ in the wider sense seriously enough. As the main protagonist of this form of warfare, an omission might turn out to question the success of the ‘War on Terror’ in general and Operation Enduring Freedom in particular. It remains to be seen whether Obama’s recent announcement to impose tighter oversight and targeting rules on drone strikes will be enough to change anything.

Sascha-Dominik Bachmann is a Reader in International Law (University of Lincoln); State Exam in Law (Ludwig-Maximilians Universität, Munich), Assessor Jur, LL.M (Stellenbosch), LL.D (Johannesburg); Sascha-Dominik is a Lieutenant Colonel in the German Army Reserves and had multiple deployments in peacekeeping missions in operational and advisory roles as part of NATO/KFOR from 2002 to 2006. During that time he was also an exchange officer to the 23rd US Marine Regiment. He wants to thank Noach Bachmann for his input. This blog post draws from Sascha’s article “Targeted Killings: Contemporary Challenges, Risks and Opportunities” in the Journal of Conflict Security Law and available to read for free for a limited time.

The Journal of Conflict & Security Law is a refereed journal aimed at academics, government officials, military lawyers and lawyers working in the area, as well as individuals interested in the areas of arms control law, the law of armed conflict and collective security law. The journal aims to further understanding of each of the specific areas covered, but also aims to promote the study of the interfaces and relations between them.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in Public International Law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Drone killings appeared first on OUPblog.

The mystery of the Hanging Garden of Babylon

I once gave a general talk about ancient Mesopotamian gardens, and was astonished, when I prepared for it, to find that there was really no hard evidence for the Hanging Garden at Babylon, although all the other wonders of the ancient world certainly did exist. A member of the audience stood up and said how disappointed she was that I had not mentioned it. All the stories of the garden were written by Greek writers many centuries after the garden was supposedly built, so some scholars thought the accounts were fairy-tale fiction. That meant that the Hanging Garden didn’t fit the category of marvellous places you could visit. I could see that my audience was disappointed, and the problem lingered irritatingly in the back of my mind.

Some years later I was working on an inscription of the Assyrian king Sennacherib who ruled around 700 BC, at Nineveh not Babylon. It was edited in the 1920s, and one passage made nonsense in the translation.

With a further 70 years of scholarly work now available, including vastly better dictionaries, I have been able to show that the passage relates how Sennacherib cast screws in bronze for watering his terraced garden, some centuries before the time of Archimedes whose name is usually quoted as the inventor. The castings were huge. Sennacherib’s own inscriptions show that he was personally proud of his technical achievements in metal-casting, water management, and collecting exotic foreign plants. Sennacherib called his work a wonder for all peoples.

Because this was all so unusual and unexpected, I re-read the Greek accounts of the Hanging Garden. Strabo mentioned the use of the screw, and must have known that Archimedes lived long after the garden was supposedly made. Herodotus described Babylon, but did not mention the garden. Only one author, Josephus, actually named Nebuchadnezzar as the builder. Another wrote that an Assyrian king built it. Could it be that there were so many confusions, especially Nebuchadnezzar for Sennacherib, Babylon for Nineveh?

In the British Museum a panel of sculpture found at Nineveh had long been understood as a likely prototype for the Hanging Garden at Babylon. It was carved in the reign of Sennacherib’s grandson, and was thought to show Sennacherib’s garden when it had matured. It shows an aqueduct supplying water just as the Greek accounts said. The British Museum also has a 19th century drawing of a sculpture from Nineveh, now lost, which matched the most original detail in the Greek texts: there was a pillared walkway on the top terrace of the garden, thickly roofed, and trees were planted on top of that roof.

The aqueduct shown in the British Museum’s sculpture could not be traced by archaeologists at Nineveh, but could be traced further away in a watercourse that stretched back 80km into the mountains. Wonderful rock-cut panels with huge sculptures of the king Sennacherib and the gods of Assyria, as well as an inscription, revealed that the palace garden at Nineveh was only the end result of a staggering work of water engineering.

More than 300 years later, when Alexander the Great was preparing for the battle of Gaugamela in which he defeated the Persian king, he camped in the vicinity of a central part of Sennacherib’s watercourse where over two million dressed stones were used in an aqueduct crossing a valley. His scouts would have seen inscriptions and sculptures, and heard about the garden. Later Greek writers extracted their accounts of the Hanging Garden from Alexander’s companions whose writings no longer survive.

There may be much confusion surrounding the Hanging Garden, but it is clear that amazing technology created a magnificent garden and justifies its place among the original seven wonders of the world.

Stephanie Dalley is an Honorary Research Fellow at Somerville College, Oxford, and a member of the Oriental Institute at Wolfson College, Oxford. With degrees in Assyriology from the Universities of Cambridge and London, her academic career has specialized in the study of ancient cuneiform texts and she has worked on archaeological excavations in Iraq, Turkey, Syria, and Jordan. Her most recent book, The Mystery of the Hanging Garden of Babylon, was published by OUP in 2013.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The mystery of the Hanging Garden of Babylon appeared first on OUPblog.

June 16, 2013

Presidential fathers

On Father’s Day, we rarely celebrate presidents, though we could. All but a handful of our presidents were fathers, and our first president, George Washington, is commonly regarded as the Father of our country. While of course nothing about being president necessarily makes anyone a better parent, many presidents have in fact had their legacies largely shaped by their relationships with their fathers and children. Only a few of these relationships have been examined at great length, especially those between John Adams and George H.W. Bush and their two sons, who each became president in their own right. While most others have been forgotten, remembering at least some of them would enrich our understanding of not only other presidencies but also the human dimensions of the presidency.

Consider just three examples. First, William Henry Harrison is known only as the first president to die in office. He is widely dismissed having been a non-entity as president since he died merely 31 days after his inauguration. Yet, Harrison came by his interest in politics honestly. He was the son of a distinguished politician, Benjamin Harrison V, who had been, among other things, a delegate to the Continental Congress, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, and a Governor of Virginia. Before becoming president, William Henry Harrison had enjoyed a career in public service that rivaled his father and had 11 children, including one whom he named after his father. Another one of his sons, John, had 10 children himself, including one whom he named Benjamin. Benjamin was eight years old when his grandfather became president. When Benjamin became president in 1888, he was determined not to fade into obscurity as his grandfather had done. He accomplished a surprising amount in his one term in office, including making four Supreme Court appointments (the fourth most by a president in a single term) and signing several landmark pieces of legislation, including the Sherman Antitrust Act. However when his wife died in the midst of his reelection campaign, he lost whatever desire he had left for public service. He subsequently married his deceased wife’s niece and former secretary, and lived out his remaining days estranged from his other children but active as both a distinguished lawyer and father to their young child.

Franklin Pierce was a president who was heavily influenced by his son. Most historians dismiss Pierce as a weak, ineffective president. Yet Pierce’s presidency cannot be understood without recognizing the tragedy before it. As he, his wife, and young son traveled to Washington for his inauguration, the railcar in which they were riding came off the tracks and Pierce and his wife watched helplessly as the train rolled down an embankment, their son crushed to death. Pierce’s wife Jane never recovered. She spent most of her time in the White House shunning her husband and blaming him for the death of their son. The effect on Pierce himself was hard. He opened his inaugural address by asking the American people to give him strength. Throughout his presidency, he looked for solace in religion and in the company of a very few people whom he liked and trusted. Among these was Jefferson Davis, who wielded enormous influence over Pierce as his Secretary of War. Davis, along with Senator Stephen Douglas, persuaded Pierce to abandon his campaign pledge to maintain the Missouri Compromise (which barred slavery in certain federal territories) and instead to sign into law a bill that allowed the new States of Kansas and Nebraska the sovereignty to decide for themselves on whether to allow or bar slavery. Pierce’s decision to side with the pro-slavery forces in Kansas, supported by Davis, among others, provoked civil war in Kansas. After failing to be re-nominated for president by his own party (the last sitting president to have failed to have done so), he blamed abolitionists for the Civil War and looked for solace in alcohol, which eventually killed him.

William Howard Taft, like William Henry Harrison, came from Ohio and a political family. Taft’s father served as both Secretary of War and Attorney General in Grant’s administration, and he instilled within his son William a strong passion for public service. By the time he became president, William Howard Taft had assembled one of the most distinguished records of public service of any president, including service as Secretary of War and federal court of appeals judge. Unlike Harrison, Taft made it through one term, though he did not enjoy it. He wanted instead to become Chief Justice of the United States, a position he achieved almost a decade after losing reelection in 1916. Taft had three children, including one son, Robert, whom he named after the first Taft to settle in this country. Robert’s son, Robert Jr., became an influential senator from Ohio and strong contender for the presidency in the 1950s. Bob Taft, Jr., shared his grandfather’s staunch conservatism and became a model for conservative senators throughout the remainder of the 20th century.

One of the conservatives whom William Howard Taft strongly influenced was Calvin Coolidge. Coolidge was a little known Governor of Massachusetts when he became Warren Harding’s running mate and Vice-President. After Harding died, Coolidge won Americans’ confidence when he helped to oversee the investigation into the corruption in Harding’s — and his own — administration. When he nominated the Attorney General he had brought in to clean up the Justice Department, Harland Fiske Stone, to the Supreme Court, Stone made history himself as the first Supreme Court nominee to testify before the Senate Judiciary Committee. By 1924, Coolidge was so popular that he easily won election to the presidency in his own right. Unfortunately, by then, he had lost his interest in the job. Just before the election, his beloved son, Cal, died from a freak accident he had suffered while playing tennis bare foot on the White House tennis court. Coolidge became eager to leave the presidency and did little to help his Secretary of Commerce, Herbert Hoover, in his presidential bid in 1928. When Coolidge died shortly before Franklin Roosevelt’s inauguration, most Americans had either forgotten him or dismissed him as a relic of the past.

These other presidents, who both influenced and were influenced by their children, are reminders that in the end presidents are people too. They are not just powerful leaders but also, sometimes more importantly, fathers; and the pride and pain they felt as fathers were at least as important to them as anything they did in office.

Michael Gerhardt is Samuel Ashe Distinguished Professor of Constitutional Law at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. A nationally recognized authority on constitutional conflicts, he has testified in several Supreme Court confirmation hearings, and has published several books, including The Forgotten Presidents: Their Untold Constitutional Legacy. Read his previous blog post “The presidents that time forgot.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Presidential fathers appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers