Oxford University Press's Blog, page 937

June 5, 2013

Multifarious Devils, part 2. Old Nick and the Crocodile

In our enlightened age, we are beginning to forget how thickly the world of our ancestors was populated by imps and devils. Shakespeare still felt at home among them, would have recognized Grimalkin, and, as noted in a recent post, knew the charm aroint thee, which scared away witches. Flibbertigibbet (a member of a sizable family in King Lear), the wily Rumpelstilzchen, and their kin have names that are sometimes hard to decipher, a fact of which Rumpelstilzchen was fully aware. For some reason, devils, at least in English, are often called old: Old Bogey, Old Scratch, Old Nick, and even Old Nick Bogey…. Bogey was my subject two weeks ago, Scratch has respectable Germanic siblings (probably also onomatopoeic), and Nick seems transparent. But who was Nick? This question has bothered numerous researchers.

Did Nick at any time refer to some person (real or mythic) or does the name go back to Engl. nicker “a water sprite”? In Old English, nicor was a sea monster, and Beowulf met many of them while swimming through the ocean. However, nicker is a word only folklorists today recognize easily, whereas Old Nick is still familiar to many. Some people even think that nickname (from an eke name “additional name”; eke as in eke out one’s salary, related to German auch “also” and so forth) is really Nick name, given intentionally to hoodwink the Devil: confused by a wrong name, the one not given at birth, the Devil will not fetch his victim. More than one etymologist suspected that Old Nick “nicks” (kills) people, that is, cuts them; leaves a notch in them; has something to do with their necks, or taunts them (compare German necken “tease”).

A truly bizarre etymology of Old Nick connects Nick with Niccolò Machiavelli. As Macaulay observed, while the Church of Rome pronounced Machiavelli’s works accursed, Englishmen coined out of his surname an epithet for a knave and of his Christian name a synonym for the Devil. Fortunately, he admitted the existence of a schism on this subject among antiquarians and philologists, but it is odd that he could mention such a conjecture as worthy of anyone’s attention. The OED discusses the Old Nick and Machiavelli theory. Samuel Butler, the author of Hudibras, wrote: “Nick Machiavel had ne’er a trick,/ Though he gave his name to our Old Nick,/ But was below the least of these” (III.1: 1313). Hudibras, a long mock-heroic satire by Samuel Butler (not to be confused with another Samuel Butler, the author of The Way of All Flesh, Erewhon, and other clever but moderately entertaining books), was published in three parts between 1663 and 1678. The Machiavellian etymology of Old Nick must have been widely popular in the middle of the seventeenth century for the collocation surfaced in print just around that time. One should always count on a period during which a joke or slang leads an underground existence before it turns up in a written text, but if Old Nick had long existed before 1678 in what we today call oral tradition, it would probably have left some traces in legends, charms, or songs. The earliest citation of Old Nick in the OED is dated to 1643.

A fairly recent hypothesis derives Old Nick from Old Iniquity, the name of the devil in medieval plays. The derivation is clever, and the OED mentions it in a noncommittal way, but it is one of several equally ingenious guesses. Charles P. G. Scott, the etymologist for The Century Dictionary, wrote a book-length article titled “The Devil and his Imps.” At one time, he remarked, the name Nicol was very common (compare Nicolson). That Nicol could be abbreviated to Nick requires no proof. But Nick also served as the “nickname” for Hick (from mine Hick, in the same way in which Ned developed from mine Ed). As a result (so Scott), it aligned itself with Dick (the root of Dickens; compare what the Dickens!), Hob, Rob, Jack (with the lantern), Will (with the wisp), and the devil Hick, to cite a few. In Scott’s words: “In considering the application of the name Nick thus derived, and of other familiar personal names, to the Devil, we are not to think of that personage as the black malignant theological spirit of evil, but rather as a goblin of limited powers, a ‘poor’ devil, who may be half daunted, half placated, by a little friendly impudence or homely familiarity.” Curiously, not a hint of this hypothesis can be found in The Century Dictionary.

Scott was an excellent etymologist, neglected by later scholarship and most undeservedly forgotten. He denied any connection between Nick and Old Engl. nicor, though this connection was taken for granted by all earlier sources, including the first edition of Skeat’s dictionary (1882). Here the OED (in 1907) followed Scott, and once the OED made its opinion known, everybody repeated it. Skeat, too, gave up his initial idea. We don’t know whether the name Old Nick is considerably older than the seventeenth century or roughly contemporaneous with the sixteen-forties. As I said, the first scenario is unlikely. However, serious scholars have at least twice tried to discover echoes of ancient superstitions in Old Nick. According to a medieval legend, a certain man called Nicola pesce (Italian pesce “fish”) could live many days under water and plunge to the bottom of the sea. Popular belief turned this person into a sea demon—hence, allegedly, Norwegian Mikkelfisk, from the unattested Nickelfisch. In it n is said to have become m under the influence of the Scandinavian word for “great” (as in Scots mickle), and confusion with St. Michael was the result. Elsewhere, the fabulous sea dweller was confused with St. Nicholas. We can see that Johann Knobloch, the author of this reconstruction, also does without Old Engl. nicor but in a way different from Scott’s.

Unlike Scott and Knobloch, Claude Lecouteux returned to nicor and the words related to it. In Germany, nicchus ~ nihhus (now Nix ~ Nixe) meant “crocodile.” Lecouteux suggested that St. Nicholas, whose cult spread in the eleventh century, was venerated for encountering and vanquishing a sea monster (a nihhus) and became inseparable from him. He pointed out that St. Nicholas has strong ties with water. Quite often the saint appears in legend accompanied by a frightening figure, seemingly a transformation of his old adversary. This theory has a grave flaw. Beowulf killed Grendel (another water demon) and his mother, while St. George killed the dragon, but we do not have a story in which St. Nicholas confronts the nihhus. One would have expected that such a story would have become the kernel of his cult.

As far as I can judge, all the conjectures briefly mentioned above are wrong. My bitter experience has taught me that an etymologist never knows enough. Certain facts look convincing, as has happened with Old Nick, but there is one more that ruins the reconstruction. Neck, necken, to nick, “Nick” Machiavelli, nicor ~ nihhus (nicker), Old Iniquity, Hick, the amphibian Nicola pesce, the indomitable St. Nicholas— some of them had at least some chance of becoming Old Nick, while others had none. Sometimes the decisive factor in offering a good derivation is chronology. Why did Old Nick turn up only in the seventeenth century? The scholars and amateurs who dealt with our “poor devil” never asked this question and missed a crucial piece of information. What is it? But here, Scheherazade-like, I will stop, to return to my fairy tale next week (not next night).

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Nøkken by Theodor Kittelsen, 1904. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Multifarious Devils, part 2. Old Nick and the Crocodile appeared first on OUPblog.

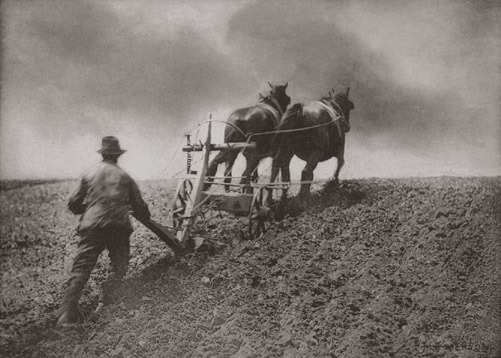

Traditional farming practices and the evolution of gender norms across the globe

The gender division of labor varies significantly across societies. In particular, there are large differences in the extent to which women participate in activities outside of the home. For instance, in 2000, the share of women aged 15 to 64 in the labor force ranged from a low of 16.1% in Pakistan to 90.5% in Burundi.

A number of scholars have argued that these differences reflect differences in underlying cultural values and beliefs. Consistent with this, data on self-reported values about gender confirm that countries with lower female labor force participation also have stronger beliefs of gender inequality. However, this culture-based explanation still leaves unanswered the deeper question of why cultural differences exist in the first place.

One hypothesis, initially proposed by Ester Boserup (1970), is that the origin of these differences lies in the different types of agriculture traditionally practiced across societies. In particular, she highlights important differences between shifting agriculture and plough agriculture. Shifting agriculture, which uses hand-held tools like the hoe and the digging stick, is labor-intensive with women actively participating in farm work. By contrast, plough agriculture is more capital-intensive, using the plough to prepare the soil. Unlike the hoe or digging stick, the plough requires significant upper body strength, grip strength, and bursts of power, which are needed to either pull the plough or control the animal that pulls it. As well, farming with the plough is less compatible with simultaneous childcare, which is almost always the responsibility of women. As a result, men tended to specialize in agricultural work outside the home.

Within plough agriculture societies, centuries of a gender-based division of labor created a cultural belief that it is more natural for men to work outside the home than women. These cultural beliefs then continue to persist even after the economy transitions from agriculture to industry and services. Through this cultural channel, traditional agriculture affects the participation of women in activities performed outside of the home today.

We empirically tested this hypothesis by combining pre-industrial ethnographic data, reporting whether societies traditionally used the plough in pre-industrial agriculture, with contemporary measures of individuals’ views about gender roles, as well as measures of female participation in activities outside the home. Using this linked data we found that countries with ancestors that traditionally engaged in plough agriculture have greater gender inequality today. In particular, traditional plough agriculture is associated with self-reported attitudes reflecting greater gender inequality, and with lower female labor force participation, less female firm ownership, and less female participation in politics.

Our study complements the cross-national estimates with analyses using individual-level data from national censuses of eight countries from Africa, Asia and Latin America. (These are all countries for which the micro data necessary for the analysis is available.) Comparing women living within the same district of a given country but from different ethnic backgrounds, we show that ancestral plough use is associated with less female labor force participation today.

We also explore differences across individuals in self-reported beliefs about gender roles, taken from the World Values Surveys. Looking across 700 regions within 79 countries, we find that a tradition of plough use is associated with a greater prevalence of the belief that men should have priority to jobs over women, and that men make better leaders than women.

Having traced the long-term impact of traditional plough-use on gender norms, we finally turned to an analysis of the precise channels underlying the effects. It is possible that the persistence of cultural beliefs and values explains the developments we identify. But, it is also possible that traditional plough use also affected the formation of specific institutions, markets, and policies, which in turn affected the activities of women in society. To disentangle the impact of the plough working through institutions versus direct cultural persistence, we examined the behavior of the children of immigrants to the United States and to twenty-six European countries. The sample of immigrant children is particularly informative because it provides us with a set of individuals who now live in identical institutional settings, but have different cultural backgrounds. Even within this group, we find that a history of ancestral plough-use is still strongly related to lower female labor force participation and to stronger attitudes of gender inequality.

Although our findings should not be interpreted as showing that only history matters, our findings do show that history does matter, and that to fully understand differences in current cultural traits around the globe it is important to look back in time at their evolution and persistence.

Alberto Alesina, Paolo Guiliano, and Nathan Nunn are the authors of “On the Origins of Gender Roles: Women and the Plough” in The Quarterly Journal of Economics, which is available to read for free for a limited time. Paola Giuliano is an Assistant Professor of Economics in the Global Economics and Management Group at UCLA Anderson School of Management. Her main areas of research are culture and economics and political economy.Professor Giuliano is a faculty research fellow of the NBER and the CEPR, and a research affiliate of IZA (Institute for the Study of Labor). She received the Young Economist Award from the European Economic Association in 2004. Nathan Nunn is a Professor of Economics at Harvard University. Professor Nunn’s primary research interests are in economic history, economic development, political economy and international trade. He is an NBER Faculty Research Fellow, a Research Fellow at BREAD, and a Faculty Associate at Harvard’s Weatherhead Center for International Affairs (WCFIA). He is also currently co-editor of the Journal of Development Economics. Alberto Alesina is the Nathaniel Ropes Professor of Political Economy at Harvard University. He served as Chairman of the Department of Economics from 2003 – 2006. He is a leader in the field of Political Economics and has published extensively in all major academic journals in economics. He has published five books and edited many more.

The Quarterly Journal of Economics is the oldest professional journal of economics in the English language. Edited at Harvard University’s Department of Economics, it covers all aspects of the field.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only anthropology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: A Stiff Pull by Peter Henry Emerson. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Traditional farming practices and the evolution of gender norms across the globe appeared first on OUPblog.

Violence, now and then

We are used to finding a stream of extreme violence reported in the media: from the brutal familial holocaust engineered by Mick Philpott to the terror of the Boston bombings. Maybe it is because such cases seem close to home and elicit reactions both voyeuristic and frightened, that they gain so much more emotive coverage than quotidian violence in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan. As a historian of violence, it is tempting to join in this discussion. And yet it is perhaps more revealing to comment upon the commentary. Indeed, the meta-commentary surrounding these cases has been particularly striking: from outrage over the demonization of the welfare state by the Daily Mail, to criticism of the hypocrisy of political and media focus on the Boston bombings, to the exclusion of the higher mortality rates from daily American gun-crime. Such acts are self-evidently out of the ordinary, abnormal. And yet they can tell us a lot about the ordinary, about what is considered normal, in the reactions they elicit. Then we can expose the fissures and hypocrisies of our own responses to violence.

This also presents a fruitful approach for historians and anthropologists of violence. In many ways, this is a question of sources; we are reliant upon representations of acts of brutality and all the distortions that this entails. So it makes sense to think more carefully about how violence was, and is, represented and reacted to. In my own work on the fourteenth century, a picture of a society with a somewhat schizophrenic attitude towards physical violence emerges. Levels of violence and bloodshed were probably very high compared to nowadays. Yet the very profusion of evidence, legal, literary and moral, indicates that this was an era when people were bothered and frightened by extreme violence, but couldn’t quite make up their minds about it. They weren’t sure what distinguished violence from discipline, familial or judicial; whether violence was the prerogative of the state, or whether it was a useful way of negotiating social relations within the community; sometimes they weren’t even sure whether things were funny or appalling. But they certainly discussed violence in ways at least as complex as commentary today.

On the one hand, we find old men traumatised by memories of violence from half a century previously. An inquiry into judicial rights in the northern French village of Ham-en-Artois in 1303 reported witnesses in their sixties recalling their distress at seeing a murdered corpse when they were just ten years old. They remembered the name of the victim, the location of the body, the time when the crime was supposed to have been committed. The source reveals not just distressed individuals unable to shake off the vision of violence many years later, but a community which had discussed the case over the intervening years, debating, corroborating, and clarifying the details. Here we have a picture of a society shocked and upset by brutality.

On the one hand, we find old men traumatised by memories of violence from half a century previously. An inquiry into judicial rights in the northern French village of Ham-en-Artois in 1303 reported witnesses in their sixties recalling their distress at seeing a murdered corpse when they were just ten years old. They remembered the name of the victim, the location of the body, the time when the crime was supposed to have been committed. The source reveals not just distressed individuals unable to shake off the vision of violence many years later, but a community which had discussed the case over the intervening years, debating, corroborating, and clarifying the details. Here we have a picture of a society shocked and upset by brutality.

But consider reactions to the following incident. Records from 1288 in the northern French town of Merck describe an accusation by the wife and child of a man who had apparently committed suicide; they claimed that the local legal official had engineered the man’s death by drowning in order to make it look like suicide. The official was apparently motivated by personal enmity, as well as sheer greed (a suicide’s possessions were forfeited to the relevant authorities). We cannot know the truth of the case. But we do know that this complaint only gained attention several years later and that the official was barely held accountable, perhaps out of unwillingness to undermine the legal system, perhaps because it was sensed that this was really about personal vendetta. He even gained re-employment in another town in a similar capacity. Thirteenth-century contemporaries were not overly bothered by the emotional and physical cruelty of the incident.

What can we learn nowadays from these widely contrasting responses to violence in the fourteenth century? There may have been a statistical decline in levels of physical violence over the centuries, and we may have become more sensitized to the sight of blood, but this doesn’t mean that our reactions have become any less problematic and ambivalent. If we step back and think about the range of modern reactions to violence — from horror at cases like that of Mick Philpott or the Boston bombings, to a willingness to turn aside from confronting the impact of gun-crime, to the chronic brutality in much modern entertainment — we will find a similarly complex and troubling set of attitudes. Whilst so-called acts of terror seem to linger in the collective memory, we quickly forget or turn aside from much violence which challenges our collective responsibility in ways too challenging fully to acknowledge.

Hannah Skoda is Fellow and Tutor in History at St John’s College, Oxford. Her recent published work includes Medieval Violence: Physical Brutality in Northern France, 1270-1330 and Legalism: Anthropology and History, co-edited with Paul Dresch. She is currently embarking on research into the misbehaviour of students in fifteenth-century Oxford, Paris, and Heidelberg. She writes about the perspectives afforded by the study of medieval history on her blog, Ideas Now and Then.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only sociology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Vie de saint Denis – cropped [public domain] via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Violence, now and then appeared first on OUPblog.

Foolish, but no fool: Boris Johnson and the art of politics

It would be too easy – and also quite mistaken – to define Boris Johnson as little more than the clown of British politics; more accurate to define him as a deceptively polished and calculating über-politician.

The news that receives the least attention arguably tells us the most about contemporary politics and society. Therefore, the fact a recent Appeal Court decision – that it was in the ‘public interest’ for people to know Boris Johnson had fathered a child in 2009 – was met with little or no public outcry or debate pricked my attention (a poor choice of phrase I admit). Philandering politicians are rarely popular and in this case the British judicial system seemed intent on underlining the manner in which Boris Johnson’s ‘recklessness’ raised serious questions about his fitness for public office. And yet there appears to be one set of rules for Boris and a completely different set for all other politicians. Social attitude surveys consistently reveal that the public expects higher moral standards and behavior from its elected representatives than from any other profession. The public are, however, far more forgiving when it comes to Boris. A poll last week found that over three-quarters of respondents disagreed that the revelation about him secretly fathering a child would make them any less inclined to vote for him in a General Election.

As Paul Goodman, editor of the ConservativeHome website, said, ‘In modern politics unconventional politicians are judged by different rules from conventional ones. Boris is part of a small band of unconventional politicians’. However, the danger of this interpretation is that it risks adding to ‘the cult of Boris’ in a way that simply overlooks the carefully manufactured foppishness. The head scratching dufferishness, slightly confused – even deranged – look of a person that does not seem to know where they have been, where they are, or where they are going is little more than an act. An act, more importantly, that veils the existence of an incredibly sharp, astute, and calculating politician.

The public may therefore be entertained by Boris Johnson’s antics, and he certainly adds a dash of color to an increasingly grey and soulless profession, but there is value in looking a little deeper at someone who covets the very highest office. I’m not actually bothered if ‘ping pong is coming home’ or if he ‘mildly sandpapered something somebody said’ (and was sacked from The Times as a result) or about any of the other misdemeanors and indiscretions that form part of his personal or political history. I am, however, interested in understanding his capacity for political survival and isolating what distinguishes Boris from his contemporaries. The answer lies in a combination of charisma and guile.

Charisma is, as Max Weber famously argued, a critical element of political leadership despite the fact that it is almost impossible to measure, define or quantify. The simple fact is that – like him or loathe him – Boris Johnson is charismatic. I remember watching him address a large public audience in Bromley during the summer of 2010 as part of the Mayor of London’s ‘Outreach’ initiative. What was immediately striking was the manner in which he captivated the audience. They were entranced to the extent that strident political opponents seem disarmed by his rhetoric, energy, and emotion. He knew how to play the audience like a conductor on a podium, and play them he did. Yet, charisma on its own is not enough, and just as Machiavelli argued that a true leader needed the strength of a lion and the cunning of a fox, so too must charisma be matched by guile.

One central element of Boris Johnson’s political arsenal rests in answering every question not with an answer but with a joke or an anecdote — guile in the form of distraction. The hot gymnasium in a large Bromley secondary school therefore provided a master-class in political oratory and theatre but little in terms of ‘Questions and Answers with the Mayor of London’. The critical point, however, was that nobody in the audience seemed to care. They had come – from all walks of life and from all parts of the political spectrum – to see ‘the Boris Show’ and that’s what they got. As I loitered by the exit to the gym at the end of the event I asked one or two questioners how they felt about the manner in which Boris had dealt with their questions (obliquely in one case, not at all in the other): the responses – ‘Isn’t he lovely!’ and ‘I don’t care – it was good fun!’ – left me strangely puzzled and downcast.

The point I am trying to make is that Boris Johnson is no fool. He may often be foolish in terms of how he behaves or what he says, but he is no fool. His buffoonery provides a rather odd but strangely effective political self-preservation mechanism that often distracts opponents or inquisitors from the more important issues of the day.

Defining Boris Johnson’s statecraft as little more than politics as the art of distraction may be unfair; suggesting that the public is unable to see beyond the japes of an old Etonian may be equally unfair. But as more and more people comment on Boris’ Teflon-like ability to shrug off personal, political, and sexual controversies I thought it might be useful to try tomake something stick.

Matthew Flinders is Professor of Parliamentary Government & Governance at the

University of Sheffield. He was once the victim of ‘the Boris lunge’ (this is where Boris takes an interviewer by surprise by grabbing their list of questions off them before proceeding to select those questions he wishes to answer from the list). Author of Defending Politics (2012), you can find Matthew Flinders on Twitter @PoliticalSpike and read more of Matthew Flinders’s blog posts here.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Boris Johnson. Photo by Adam Procter, 2006. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Foolish, but no fool: Boris Johnson and the art of politics appeared first on OUPblog.

June 4, 2013

Why is Emily Wilding Davison remembered as the first suffragette martyr?

“She paid ‘the price of freedom’. Glad to pay it — glad though it brought her to death (..) the first woman martyr who has gone to death for this cause.” In the context of the women’s suffrage campaign who do you think was the subject of this eulogy? Was it Emily Wilding Davison, the centenary of whose death is being honoured this June?

Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst

In fact the words are taken from the obituary for Mary Clarke, Emmeline Pankhurst’s “dearest sister”, who died in 1910, two days after being released from Holloway, her imprisonment a direct result of her actions as a suffragette. The obituary, published in Votes for Women (6 January 1911), was written by Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, one of Mrs Pankhurst’s co-leaders of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) and explained that, to bring women freedom, “Mary Clarke laid down her life [and] faced ridicule, blows, hard usage by roughs, the handling of the police, and three imprisonments.” After this eulogy why is Mary Clarke forgotten and it is Emily Wilding Davison who is hailed as the first martyr to the cause of ‘Votes for Women’?Unlike Emily Davison, Mary Clarke was not merely a member of the WSPU, but one of its inner circle, fully involved in the campaign from its early days, twice imprisoned after taking part in deputations, and, from mid-1909, based in Brighton as a paid organizer. Her final imprisonment came at the end of November 1910; she had thrown a stone through the window of a London police station. On 23 December, on her release from Holloway, she spoke at a WSPU ‘welcome’ luncheon and two days later, aged 48, died of a brain hemorrhage attributed to the strain of her prison sentence. Her sister, Emmeline, was at her side when she died.

Why did Mary Clarke, ‘the first woman martyr who has gone to death for this cause’, not receive from the WSPU a splendid funeral, on a par with the published encomium? Her funeral was, in fact, very quiet; as Mrs Pethick-Lawrence reported “There was no singing at the graveside, for owing to the break-up of the holidays the funeral was private and but few were able to be present.” But such by now was the power the WSPU could exert over its members that, holidays or not, if it had decided to make a public spectacle out of the death of Mrs Pankhurst’s favourite sister, a public spectacle there would have been.

The answer lies in the politics of the day. In early January 1911 a general election was underway and it was not advantageous for the WSPU to divert resources away from their campaign of opposing Liberal candidates. Nor, of course, was January a good seasonal moment; the first London suffragist rally, held in February 1907, wasn’t named the “Mud March” for nothing. By summer 1913, however, the climate, in every sense of the word, was very different.

Since January 1911 the WSPU campaign had become increasingly militant, its leadership undergoing dramatic changes. Together with her daughter, Christabel, who had fled to Paris to escape prosecution, Emmeline Pankhurst was now sole leader. In April 1913, found guilty on a charge related to the bombing of Lloyd George’s house, she’d been sentenced to three years’ penal servitude. A dynamic series of reactions followed, resulting in Mrs Pankhurst spending successive periods in prison on hunger strike, before under the new “Cat and Mouse Act” released to recover, while many of her followers were roaming the country, on the run from the police. Emily Davison was not one of these outlaws, although, at the end of 1911, by setting fire to a pillar box, she had instigated a new level of militancy. She had served her sentence in Holloway, some of the time on hunger strike, but since her release hadn’t been directly implicated in any attacks on property.

By early June 1913 the atmosphere among WSPU members was febrile. The government was tightening its hold on the WSPU, doing all it could to deprive it of funds, members, and publicity. It’s in this context that Emily Davison’s action at the Derby and the WSPU’s reaction must be viewed. By undertaking a dangerous action, in front of the newsreel cameras on one of the most popular holiday-making occasions of the year, Emily perhaps thought to draw the world’s attention to Mrs Pankhurst’s predicament. Her action, though fatal for her, was fortuitous for the WSPU. It was by now impossible that the Home Office would have given permission for a suffragette rally per se, but to have opposed a funeral procession would have, literally, fuelled the flames. This was a final opportunity to reclaim the moral high ground, to demonstrate the dignity and solidarity of suffrage campaigners, compelled, as they saw it, by an intransigent government to employ methods of last resort.

Emily Wilding Davison’s funeral procession approaches St George’s Church, Bloomsbury, where a service was held.

The WSPU rose to the occasion and on 14 June staged a magnificent funeral procession. Kate Frye, a sympathetic eyewitness, wrote that night in her diary: “It was really most wonderful — the really organized part — groups of women in black with white lilies — in white and in purple — and lots of clergymen and special sort of pall bearers each side of the coffin. She gave her life publicly to make known to the public the demand of Votes for Women — it was only fitting she should be honoured publicly by the comrades.”

Thus it is that Emily Wilding Davison has been remembered as the epitome of suffragette sacrifice, her ‘Price of Liberty’ published in The Suffragette (5 June 1914), while Mary Clarke went quietly to her grave, ‘the price of freedom’ she paid quite forgotten.

Elizabeth Crawford is an independent researcher and the author of The Women’s Suffrage Movement: a reference guide 1866-1928 (Routledge, 1999); Enterprising Women: the Garretts and their circle (Francis Boutle, 2002); The Women’s Suffrage Movement in Britain and Ireland: a regional survey (Routledge, 2005) and Campaigning for the Vote: Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diaries (Francis Boutle, 2013). Her website Woman and Her Sphere contains a wide range of material relating to the women’s suffrage movement, as well as other areas of women’s and social history. She is the author of “‘Women do not count, neither shall they be counted’: Suffrage, Citizenship and the Battle for the 1911 Census” in History Workshop Journal, which is available to read for free for a limited time.

Since its launch in 1976, History Workshop Journal (HWJ) has become one of the world’s leading historical journals. Through incisive scholarship and imaginative presentation it brings past and present into dialogue, engaging readers inside and outside universities. HWJ publishes a wide variety of essays, reports and reviews, ranging from literary to economic subjects, local history to geopolitical analyses.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only historyarticles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) a picture of Mrs Pankhurst. Credit: Elizabeth Crawford’s Collection ; (2) a picture of EWD’s funeral. Credit: Elizabeth Crawford’s Collection

The post Why is Emily Wilding Davison remembered as the first suffragette martyr? appeared first on OUPblog.

Ten reasons you should get to know Irish playwright Stewart Parker

Stewart who? That’s okay — I’m used to starting at the beginning.

(1) Stewart Parker just might be the most important Irish writer you’ve never heard of. Born in 1941, he began his career as a poet, tried his hand at experimental prose, and eventually dedicated himself to drama. His plays for radio, television, and the stage engage with historical events to offer a range of perspectives on the political and sectarian conflicts in his native Northern Ireland, while managing at the same time to be vastly entertaining. His best-known plays include Spokesong about a Belfast bicycle salesman obsessed with his dead grandparents; Northern Star which focused on Henry Joy McCracken, one of the real-life leaders of the eighteenth-century United Irish movement; and Pentecost, set during the Ulster Workers’ Council Strike of 1974, in which four of Parker’s contemporaries share a house with the ghost of its longtime inhabitant.

(2) He wrote the first regular pop music column for the Irish Times, introducing Irish readers to musicians and bands such as Joni Mitchell and Steely Dan. Most of his plays also feature music. Spokesong, for example, includes songs that evoke styles spanning eighty years. Catchpenny Twist centers on a pair of song-writers. Kingdom Come, co-written with Irish composer Shaun Davey, is an Irish-Caribbean musical set on a fictional island where the political configuration bears an uncanny resemblance to Northern Ireland’s.

(3) He grew up in a Protestant, unionist family in industrial east Belfast. Many writers from this part of the island (C. S. Lewis, for example, whose birthplace lies within walking distance of Parker’s) neither consider themselves Irish nor are seen as such by others. Parker did regard himself as Irish, even an Irish nationalist, but his “British” background may help to explain why he has often been overlooked by people with an interest in Irish literature.

(4) He took after James Joyce in his determination to capture the multifarious life of the city of his birth. Other things he appreciated about Joyce included his sense of humor, “verbal felicity,” “positive vision of life,” and penchant for “using actual information about things in a way that transcends documentary and gives you an insight into people’s lives, relationships and history.” All of these also characterize Parker’s own writing and make it worthy of close study.

(5) He lost his left leg to a rare form of bone cancer at age 19. Living as an amputee gave him a greater appreciation than most of us of the things that human beings have in common, chief among these mortality. His consciousness of the frailty of human bodies and the finitude of human existence reinforced his intolerance of violence and the arbitrary distinctions that divide people from one another.

(6) He belonged to the original Belfast Writers’ Group, founded by English poet and academic Philip Hobsbaum in 1963. Hobsbaum had a keen eye for talent, and he considered two members of the group especially promising. One of these, Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney, you probably do know something about. The other was Stewart Parker.

(7) He spent five formative years in the United States. From 1964 to 1969, Parker taught at Hamilton College and Cornell University, both in upstate New York, and witnessed the civil rights and anti-war movements as an interested outsider. His American sojourn decisively shaped his political consciousness and sense of purpose as a writer, prompting him to return to Northern Ireland in order to be more than an observer of social transformation.

(8) He arrived home in August 1969, the same week, coincidentally, that British troops were sent to Belfast to try to restore order there after days of sectarian rioting. Little did anyone know at the time that this round of Ireland’s periodic “Troubles” would last for nearly thirty years. Parker remained in Belfast until 1978, living through the worst of the violence there and storing up impressions that he would later draw on as a dramatist.

(9) He died of stomach cancer in 1988 at the age of 47. His early and abrupt demise has been largely responsible for obscuring his achievement.

(10) He was a fine person as well as a great writer. As even the most casual student of literature knows, the two do not always go together, but in Parker’s case they did. Having spent twenty years working on his biography, I should know. This book is dedicated “to the friends of Stewart Parker, old and new.” Maybe, soon, you will be one of them.

Marilynn Richtarik is an Associate Professor of English at Georgia State University in Atlanta. Her two books, Acting Between the Lines: The Field Day Theatre Company and Irish Cultural Politics 1980-1984 and Stewart Parker: A Life, are both published by Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Ten reasons you should get to know Irish playwright Stewart Parker appeared first on OUPblog.

Coronation Music

Sunday 2 June 2013 marks the 60th anniversary of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II at Westminster Abbey in London. It also therefore follows that it is the anniversary of the works which were first performed at the coronation, including William Walton’s Orb and Sceptre March and Coronation Te Deum, and Ralph Vaughan Williams’s O taste and see and Old Hundredth Psalm Tune (All people that on earth do dwell).

William Walton

The coronation featured works by a host of British composers — Butterworth, Byrd, Elgar, Gibbons, Holst, Parry, Purcell, and Tallis — which included a who’s who of early twentieth-century British composers — Bax, Bliss, Dyson, Howells, Ireland, Jacob, and Stanford. Not forgetting honorary Brit George Frideric Handel whose Zadok the Priest has been played at every British coronation since its première at the coronation of George II in 1727.People wrongly assume that the Walton Crown Imperial was written for the 1953 coronation. In fact it was commissioned by the BBC for the coronation of King Edward VIII (which never happened because of the abdication) but wasn’t actually used until the coronation of King George VI in 1937. The work was played during the entry of the dowager Queen Mary and Queen Maud of Norway into Westminster Abbey. The original version was reduced by 2 minutes by Walton a couple of years later for a concert version which has become popular all round the world.

To celebrate the 60th anniversary of our Queen’s coronation Bob Chilcott was commissioned to write The King shall rejoice, which will first be performed at Westminster Abbey on 4 June 2013.

Listen to the playlist below for the 1953 coronation published by Oxford University Press. Which is your favourite?

Miriam Higgins is the Music Hire Librarian for Oxford University Press. Her favourite piece on the list is Walton’s Crown Imperial.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Oxford Sheet Music is distributed in the USA by Peters Edition

Image credit: Image courtesy of Oxford University Press Sheet Music department.

The post Coronation Music appeared first on OUPblog.

June 3, 2013

10 Questions for Jonathan Dee

Each summer, Oxford University Press USA and Bryant Park in New York City partner for their summer reading series Word for Word Book Club. The Bryant Park Reading Room offers free copies of book club selections while supply lasts, compliments of Oxford University Press, and guest speakers lead the group in discussion. On Tuesday 4 June 2013, author Jonathan Dee leads a discussion on Father and Son by Edmund Gosse.

Jonathan Dee. Photo by Ulf Andersen.

What was your inspiration for this book?

I would say a combination of Tiger Woods and John Calvin.

Where do you do your best writing?

In conditions of silence, with a pen and a legal pad, in the easy chair in my living room.

Which author do you wish had been your 7th grade English teacher?

Probably Edna O’Brien, or Clarice Lispector, or Sylvia Plath . . . Remember, I’m a 7th grade boy in this scenario.

What is your secret talent?

My daughter would say it is that I can talk like Donald Duck.

What is your favorite book?

Impossible to say. Madame Bovary, Anna Karenina, To The Lighthouse, The Good Soldier, The USA Trilogy, The Postman Always Rings Twice . . .

Who reads your first draft?

My first drafts are written in longhand, so no one else could read them even if they wanted to.

Do you prefer writing on a computer or longhand?

See above.

What book are you currently reading? (Old school or e-Reader?)

Death of the Black-Haired Girl by Robert Stone. Old school always.

What word or punctuation mark are you most guilty of overusing?

The semicolon. Like duct tape for sentences. The worst part is how I scoff at other writers who have the same weakness I do.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you be?

In my twenties I worked at The Paris Review, on the theory that if I didn’t make it as a writer, I would still want a professional foothold in some world where people valued the same things I did. So I probably would have been an editor of some sort, or an academic.

Did you have an “a-ha!” moment that made you want to be a writer?

Reading the short story “So Much Unfairness of Things” by C.D.B. Bryan when I was in the seventh grade. It was my introduction to the idea that a story’s job might be to make it harder, rather than easier, to judge the characters within it.

Do you read your books after they’ve been published?

Never. I can’t finish a page without coming across a sentence I want to rewrite, and it’s painful to realize that I’m too late.

Jonathan Dee is the author of five novels, including The Privileges, which was both a finalist for the 2010 Pulitzer Prize and winner of the 2011 Prix Fitzgerald. He is a contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine, a National Magazine Award–nominated literary critic for Harper’s, and a former senior editor of the Paris Review. He teaches in the graduate writing programs at Columbia University and the New School. He is the recipient of fellowships from Yaddo, the MacDowell Colony, the National Endowment of the Arts, and the Guggenheim Foundation. His most recent novel is A Thousand Pardons.

Read previous interviews with Word for Word Book Club guest speakers.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post 10 Questions for Jonathan Dee appeared first on OUPblog.

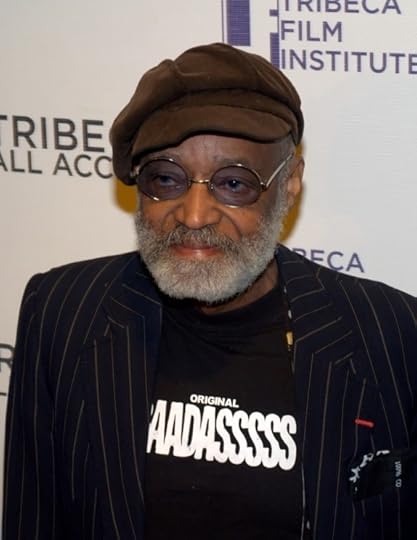

Blaxploitation, from Shaft to Django

What do you get when you combine Hollywood, African American actors, gritty urban settings, sex, and a whole lot of action? Some would simply call it a recipe for box office success, but since the early 1970s, most people have known this filmmaking formula by the name “Blaxploitation.” Blaxploitation cinema occupies a fascinating place in the landscape of American pop culture. At once vilified and glorified by different facets of the African American community, the films of this genre provide an extended meditation on the impact of racial divisions that persist even now.

Origins

1971’s Shaft, one of the first films commonly identified as Blaxploitation, gave us the character of John Shaft, possibly the quintessential Blaxploitation hero. Based on the novel by Ernest Tidyman and starring actor Richard Roundtree, the first Shaft film traces a few days in the life of the titular private detective. The contours of the story are familiar: After a series of run-ins with Harlem gangs and the Mafia, not to mention a handful of beautiful women, Shaft saves the day in an exciting (and violent) final scene. Shaft was a major commercial success and also a critical darling. Its instantly-recognizable theme song, composed and performed by Isaac Hayes, won Golden Globe, Grammy, BAFTA, and Academy awards.

[image error]

Gordon Parks Sr., director of the 1971 action film Shaft, in 1963. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Scores of similar films followed, including 1972’s genre masterpiece Super Fly. The film’s plot is perhaps less important than the attitude and image that star Ron O’Neal projected in the principal role of Youngblood Priest. Here was an African American man with power, undeniable swagger, a cool car, even a desire to put his drug-dealing ways behind him and do something greater with his life. Financed and produced entirely by African Americans, accompanied by Curtis Mayfield’s now-classic soul soundtrack, and the source of much controversy regarding the role of film in the African American community, Super Fly may have been Blaxploitation cinema’s high-water mark.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Reactions

Combining the words “black” and “exploitation,” “Blaxploitation” was originally intended to draw attention to what some saw as the corrupting nature of the emerging genre. Coined in 1972 by Beverly Hills/Hollywood NAACP chapter leader Junius Griffin to describe Super Fly, the term came to designate certain films thought to be taking advantage of African American cinemagoers’ desire to see recognizably African American stories and characters represented in cinema. Instead of providing positive depictions of African Americans, Blaxploitation films offered a window into a world of crime, sex, and violence that appealed to an audience’s most prurient interests.

Opposition to Blaxploitation cinema proved to be a galvanizing force within the landscape of American activism. The NAACP officially came out against the films, and joined forces with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to form the Coalition Against Blaxploitation (CAB) in 1972. The CAB included nearly 400 African American constituents working in the film industry and attempted to effect positive change regarding the roles of African Americans in Hollywood.

In order to combat what CORE national chairman Roy Innis identified as the films’ “subtle ways of promoting Black genocide in the Black community” through glorification of drugs and murder, the CAB attempted to develop a ratings system that would assign qualitative assessments to new films according to the films’ representation of African Americans. The CAB also organized boycotts of theaters that ran Blaxploitation movies, and even attempted to promote its agenda behind the scenes through negotiation with studio executives.

While many joined Griffin in decrying the nascent trend in African American film, there were others who denied the notion that these films were engaging in any sort of exploitation. For some, the genre’s frequent use of strong male and female leads who lived by their own code was empowering. African American characters who thrived outside the law exemplified a necessary rejection of an oppressive system designed and controlled by “the Man.” And films set in urban ghettoes reflected the experiences of millions of African Americans whose lives were otherwise absent from representation in mainstream American culture.

Indeed, Hollywood’s African American contingent was far from unified in its reaction to Blaxploitation cinema. Actor Jim Brown defended the films, for example, explaining that they created much-needed work for African American actors and writers. Fred Williamson, star of a number of Blaxploitation films, saw a double standard in the absence of similar criticism of violent films starring white actors. And director Oscar Williams understood the rejection of Blaxploitation cinema as a greedy Hollywood maneuver to keep African Americans away from the vast sums of money being made in the movie business.

Though the reasons are unclear, production of Blaxploitation films waned at the end of the 1970s. Some have suggested that this decline was due to the actions of groups such as the CAB, while others point to general audience fatigue and the films’ poor production values. Still others feel that Hollywood studios decided that they could continue to draw large African American crowds to films made up of white casts, and that Blaxploitation films were consequently not worth the trouble they created. Whatever the cause, the era of Blaxploitation had essentially ended by 1980.

Legacy

The most visible influence of Blaxploitation is on hip hop, a subculture that is unimaginable without films such as Shaft and the iconic soundtracks that accompanied them. More ambiguous, however, is the legacy of Blaxploitation in cinema—a direct result of the ongoing lack of diversity in the film industry. Numerous African American-directed movies have paid homage to the genre in some way since the late 1980s, often finding critical success, including Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing (1989), John Singleton’s Boyz in the Hood (1991), Albert and Allen Hughes’ Menace II Society (1993), and Mario Van Peebles’ New Jack City (1991) and Posse (1993). In 2000, Singleton directed a new version of Shaft with Samuel L. Jackson and Christian Bale, which served as both a sequel and a remake. Van Peebles later directed and starred in Baadasssss! (2003), which detailed the making of his father’s Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971). The influence has also extended to big budget movies primarily made by and starring white people, most notably the crowd-pleasing action movies of the 1980s. Blockbusters such as Commando (1985), in which the protagonist would often deliver a snarky one-liner after killing an enemy, were reminiscent of the black gangster films of the ’70s—only this time, the themes had more conservative and militaristic leanings.

Melvin Van Peebles, director of the 1971 Blaxploitation film Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, in New York City in 2010. Photo courtesy of David Shankbone/Wikimedia Commons.

But the filmmaker who has gotten the most mileage out of the genre is almost certainly Quentin Tarantino. Not without controversy, Tarantino has employed Blaxploitation tropes and music in hit films such as Jackie Brown (1997) and Pulp Fiction (1994). In 2012, Tarantino was able to take the genre to an epic, Oscar-winning level with Django Unchained, a violent revenge fantasy starring Jamie Foxx. Though the film was a huge success, some critics (including Spike Lee) accused Tarantino of trivializing the crime of slavery, and raised questions about whether white filmmakers should be the ones to tell the most painful stories of black history. The ongoing debate calls to mind Robert Townsend’s satire Hollywood Shuffle (1987). In that film, Townsend plays a black actor compelled to make an exploitative gangster movie, a situation illustrating the way black artists are often viewed in Hollywood. In other words, while the influence of the Blaxploitation era is undeniable, it is also clear that the genre has been co-opted into the mainstream in ways that the original filmmakers did not foresee.

Robert Repino is an Editor in the Reference department of Oxford University Press. After serving in the Peace Corps in Grenada, he earned an MFA in Creative Writing at Emerson College. His work has appeared in numerous publications, including The African American National Biography (2nd Edition), The Literary Review, The Coachella Review, Hobart, and JMWW. His debut novel is forthcoming from Soho Press in 2014.

Tim Allen is an Assistant Editor for the Oxford African American Studies Center. You can follow him on twitter @timDallen.

The Oxford African American Studies Center combines the authority of carefully edited reference works with sophisticated technology to create the most comprehensive collection of scholarship available online to focus on the lives and events which have shaped African American and African history and culture. It provides students, scholars and librarians with more than 10,000 articles by top scholars in the field.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Blaxploitation, from Shaft to Django appeared first on OUPblog.

The continuing irrationality of New York’s “Convenience of the Employer” rule

By Edward Zelinsky

On Friday, 17 May 2013, two Metro-North commuter trains collided near Bridgeport, Connecticut. Through the following Tuesday, the Metro-North accident disrupted normal commuter train service between parts of Connecticut and New York City. To cope, Connecticut Governor Dannel Malloy asked residents of the Nutmeg State to work from their homes until rail service could be restored. New York’s long-standing policy of double taxing nonresident telecommuters penalized those Connecticut residents who complied with Governor Malloy’s request that they work at home until train service to the Big Apple could be restored.

Under New York’s “convenience of the employer” doctrine, the Empire State double taxes persons throughout the country on the days such persons perform work at their out-of-state homes for New York-based employers. New York thereby improperly projects its taxing authority beyond its borders throughout the nation. When an individual works at home, it is the home state, not New York, which provides public services to that individual. Most states (quite correctly) do not grant credits against their respective income taxes for the taxes New York assesses under the employer convenience rule.

In a typical case, New York imposed its income tax on Manohar Kakar for the days he worked at his home in Gilbert, Arizona. If, for example, Mr. Kakar needed police or EMT assistance on a day he worked at home in Arizona, it was Arizona, not New York, which would have provided such assistance. It is accordingly Arizona, not the Empire State, which had a legitimate claim to tax the income Mr. Kakar earned since it was Arizona which provided government benefits to Mr. Kakar on that work-at-home day. Nevertheless, New York, despite the persuasive criticism of independent commentators, insists on imposing its income taxes on the day a nonresident, like Mr. Kakar, works at his out-of-state home for a New York employer. New York thereby projects its taxing authority beyond its boundaries, indeed throughout the nation.

In a typical case, New York imposed its income tax on Manohar Kakar for the days he worked at his home in Gilbert, Arizona. If, for example, Mr. Kakar needed police or EMT assistance on a day he worked at home in Arizona, it was Arizona, not New York, which would have provided such assistance. It is accordingly Arizona, not the Empire State, which had a legitimate claim to tax the income Mr. Kakar earned since it was Arizona which provided government benefits to Mr. Kakar on that work-at-home day. Nevertheless, New York, despite the persuasive criticism of independent commentators, insists on imposing its income taxes on the day a nonresident, like Mr. Kakar, works at his out-of-state home for a New York employer. New York thereby projects its taxing authority beyond its boundaries, indeed throughout the nation.

Consequently, Connecticut residents who work for New York employers and who heeded Governor Malloy’s call to work at home after the Metro-North accident will be penalized by double income taxation of their salaries allocable to those work-at-home days. Connecticut provided such residents with public services on those work-at-home days and thus will legitimately collect income taxes attributable to the income earned on those days. However, New York under the employer convenience banner will also assess income taxes on those days – even though the Connecticut residents who followed Governor Malloy’s advice to work at home did not set foot in New York on those days.

Governor Andrew Cuomo has commendably stated that New York should shed its problematic status as the tax capital of the United States. However, New York will retain that dubious distinction as long as New York persists in irrational tax policies like its double taxation of nonresident telecommuters on days such telecommuters work at home. It is questionable whether New York’s fiscal balance benefits from the employer convenience doctrine since that doctrine drives nonresidents to cut their ties to the Empire State to avoid tax on their telecommuting days. As a result, New York loses the taxes it could legitimately collect on the days these employees would actually have worked in New York.

Congress, under the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution, could preclude New York’s use of its employer convenience rule to tax income earned outside of New York’s borders. Most recently, in the 112th Congress, Senators Blumenthal and Lieberman, along with Representatives DeLauro, Murphy and Himes, sponsored legislation (S. 1811, H.R. 5615) to preclude any state from taxing income earned outside the state’s borders. Such federal legislation is an overdue reaffirmation of the constitutional norm that states may only tax the economic activity which occurs within their respective borders. New York flouts that rule when it projects its taxing authority beyond its boundaries via the employer convenience rule by taxing individuals on the days they work at their out-of-state homes.

Adopting legislation takes time. In the meanwhile, Governor Cuomo should suspend New York’s enforcement of its double income tax policy for the days when Metro-North commuter train service was impaired. Even better, Governor Cuomo should implement his pledge to dethrone New York as America’s tax capital by repealing the irrational employer convenience rule altogether.

Edward A. Zelinsky is the Morris and Annie Trachman Professor of Law at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law of Yeshiva University. He is the author of The Origins of the Ownership Society: How The Defined Contribution Paradigm Changed America. His monthly column appears here.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Time to pay. © Gustavo Andrade via iStockphoto.

The post The continuing irrationality of New York’s “Convenience of the Employer” rule appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers