Oxford University Press's Blog, page 938

June 3, 2013

Humor in the New Testament

For many people, religion is serious business which rules out any positive connection between belief and humor. For them, humor connected to religion is humor directed, in a negative and derisive manner, against religion. If this is true for religion in general, then the disconnect between the Bible and humor in particular would be especially well defined. However, scholarship in this field has grown in recent years and has attempted to dispel the notion that humor is inappropriate in, and absent from, Scripture.

For a quick overview of the topic, it is useful to divide exemplars into different categories. First, there are many passages that, in their original language, produced plays on words that the intended audience would have understood as humorous, or at least ironic. At the end of the tale of Susanna, which forms part of the expanded text of the apocryphal book of Daniel, a woman refuses the advances of two men, who seek revenge by bringing false charges of adultery against her. After Susanna is sentenced to death, the hero Daniel cross-examines the two men, thus proving that they have fabricated the charges. Daniel pronounces judgment on the two disgraced elders by declaring that one would be “cut” and the other “sawed.” In the original Greek, these verbs are closely related to the trees—“mastic” and “evergreen oak,” respectively—which each man falsely declared was the spot where Susanna supposedly met her lover.

La Justification de Suzanne. François-Guillaume Méneageot c. 1779. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Plays on words also recur with proper names. On some occasions, the names fit perfectly, as with Nabal (1 Samuel 25)—literally translated as “fool” or “brute” —who is exactly the “desiccated fool” that his name implies; or Eglon (of Judges 3), the Moabite king whom Ehud slaughters in precisely the way that his name—related to the Hebrew word for “fatted calf”—suggests.

At other times, the proper name is at odds with the circumstances. Thus, in the New Testament book of Luke (chapter 9), Jesus bestows the nickname “Boanerges”—meaning “the sons of thunder”—on two of his disciples just after he had thwarted their efforts to bring down lightning, presumably along with thunder, on a group of Samaritans. Another example would be the punishment inflicted upon the murderer Cain, who is doomed ironically to “settle” in the land of Nod, a word that literally means “to wander” (Genesis 4:12).

A second category of biblical humor is what I call “situational,” in that the humor derives from the context in which a given element is depicted. Without knowing the context, how, for example, would we know that it is probably funny when Peter thrice denies any knowledge of Jesus (Matthew 26)? In that case, his actions perfectly fulfill the prediction Jesus made about him, and completely contradict Peter’s promise to remain faithful (Matthew 26:31–32). When this same disciple—having just escaped from prison—is described as continually knocking at Mary’s door (Acts 12), we again see an example of situational humor: Peter begs for someone to let him in, while those inside the house waste time debating whether they have been visited by his “angel” (Acts 12:16). When Eutychus, having fallen asleep during Paul’s preaching, literally falls out of window (Acts 20), the biblical authors seem to be commenting on Paul’s tendency to be long-winded. Finally, when Zacchaeus, “short in stature,” climbs a sycamore tree to view Jesus (Luke 19), we find an example of awkward, almost slapstick humor at the expense of a laughable character.

A third category consists of what we’d probably call “vindictive” humor, in which the biblical writers, presumably on behalf of their community, takes what would appear—from at least some perspectives, although not the biblical one—unseemly pleasure in the defeat of Israel’s enemies. This is true in several narratives contained in the book of Judges, such as the above-mentioned evisceration of Eglon (Judges 3) and the defeat of the Canaanite general Sisera at the hand of Yael, a woman—especially when this is coupled with the expectations for Sisera’s bright future on the part of his unknowing mother (both found in Judges 5). The thwarting of male opponents by far wilier females is on full display throughout the book of Esther and in several chapters of the book of Judith. It is, we might opine, not for nothing that female characters bestow their names on these two books.

In general, any defeat of a male by a female would be contrary to expectations in antiquity, and this overcoming of expectations forms a fourth category of biblical humor. In addition to Yael, Esther, and Judith, we can think of Abigail as another woman who summarily bests a man, in this case the aforementioned and unfortunately named Nabal.

The overcoming of expectations is found not only in narrative, but also in sayings. An excellent example of this is found near the beginning of the Sermon on the Mount, when Jesus foretells the inheritance of the land by the meek (Matthew 5). Who would have thought it?

These examples will, I hope, entice readers to go directly to the biblical passages themselves. If beauty is, as they say, in the eye of the beholder, perhaps the same holds true for humor. Let me know what you think.

Leonard J. Greenspoon is author of the Biblical Archaeology Review’s popular “The Bible in the News” column, and holds the Philip M. and Ethel Klutznick Chair in Jewish Civilization at Creighton University in Omaha. He is editor-in-chief of the Studies in Jewish Civilization series, which is publishing its 24th volume this fall. He has just published The Bible in the News: How the Popular Press Relates, Conflates and Updates Sacred Writ, an eBook that contains a compilation of his column, “The Bible in the News,” that has appeared for over a decade in Bible Review and Biblical Archaeology Review. Recently, Professor Greenspoon completed a trio of featured essays for Oxford Biblical Studies Online: Humor in the Old Testament, Humor in the Apocrypha, Humor in the New Testament.

Oxford Biblical Studies Online is a comprehensive resource for the study of the Bible and biblical history. With Biblical texts, authoritative reference works, and tools that provide ease of research into the background, context, and issues related to the Bible, Oxford Biblical Studies Online is a valuable resource for students, scholars, clergy, and any reader seeking an up-to-date ecumenical resource. Oxford Biblical Studies Online is vetted by a team of leading scholars headed by Michael D. Coogan.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Humor in the New Testament appeared first on OUPblog.

Ten things you didn’t know about the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law

1. Key dimensions: If you are lucky enough to own the entire ten volume set, plus the Index and Tables, you will need to be equipped with a sturdy shelf. Each volume of the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law (MPEPIL) weighs roughly two kilograms.

2. Quality Control: Each article in the Encyclopedia can go through up to eight rounds of review to ensure that the scholarship is of the highest possible standard.

3. Author credentials: Over 800 scholars and practitioners from 83 countries contributed to the volumes, making it one of the most definitive reference resources on public international law.

4. Continuous evolution: The Encyclopedia online is constantly changing with new content being added and many articles revised throughout the year!

5. An A-Z of public international law: The online version of the Encyclopedia contains a grand total of 1,639 articles, on subjects ranging from air warfare to the Zambezi River — and it’s growing. Better get started.

6. Bizarre content: The Encyclopedia contains many interesting and, sometimes, unusual entries. For example, did you know that, as a result of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, states are forbidden from claiming any territorial ownership on the moon? Also, did you know that the tuna fish is the most commercial high migratory stock and is regulated in a total of five regional fishery management organizations?

6. Bizarre content: The Encyclopedia contains many interesting and, sometimes, unusual entries. For example, did you know that, as a result of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, states are forbidden from claiming any territorial ownership on the moon? Also, did you know that the tuna fish is the most commercial high migratory stock and is regulated in a total of five regional fishery management organizations?

7. Citations, citations, and more citations: The Index contains a complete list of citations for documents referenced in every article. That’s over 15,000 citations in total.

8. Number crunching: If you add together all the pages in the Encyclopedia and Index and you get… 12,836. If all pages were laid end to end, they would stretch nearly two miles.

9. Origins: The main precursor to MPEPIL was the Encyclopedia of Public International Law (EPIL), which was published between 1981 and 1990. However, radical changes in public international law over recent decades meant that nearly every article had to be completely re-written for this new edition.

10. Timeline: The Encyclopedia began to be compiled by OUP in 2004 and was first published as an online database in 2008. Finally in 2012, it was published in print and has graced the bookshelves of law scholars ever since.

Katherine Marshall is Marketing Executive for Academic Law titles at Oxford University Press.

The Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law is a comprehensive online resource containing peer-reviewed articles on every aspect of public international law. Written and edited by an incomparable team of over 800 scholars and practitioners, published in partnership with the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law, and updated through-out the year, this major reference work is essential for anyone researching or teaching international law. An all-new user experience is coming summer 2013.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in Public International Law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Full Moon by Gregory H. Revera. Creative Commons License Wikimedia Commons

The post Ten things you didn’t know about the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law appeared first on OUPblog.

A history of nationalism

In 1904 Józef Pilsudski and Roman Dmowski, rival Polish nationalist leaders, were both in Tokyo, just after Japan had defeated Russia, one of their major enemies. Japan now served as a model for other nationalists. Pilsudski was to become head of state in post-1918 independent Poland. Dmowski expressed admiration for Japanese nationalism well into the 1930s. This episode illustrates two points neglected in the history of nationalism. First, nationalism is global; nationalists are influenced by a wide range of models. Second, it calls into question the widespread assumption that if nationalism does spread, this is from “west to east”. The lines of direction have to be understood more in terms of degrees of success. Asian nationalism beyond Japan modelled itself on Japanese nationalism; African nationalism after 1947 in part was modelled on Indian success.

To explore this history calls for a range and depth of knowledge beyond the expertise of any individual. It means challenging the practice of writing the history of nationalism as one aspect of national history. General studies of nationalism are mainly theoretical and/or contemporary, dominated by disciplines such as political science, sociology, and psychology. The major exception is the history of ideas. However, the interest in nationalism is less as interesting idea and more as significant politics. In 1800 only a small part of the world political map consisted of nation-states. Nationalism as organised politics seeking such states did not exist. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union — the world’s last officially multi-national state — only a handful of states might not be categorised as nation-states. Even the Sultanate of Brunei calls itself `Nation of Brunei, Abode of Peace’. There are today 193 members of the United Nations, whose very name equates nation with state.

How to write a history of nationalism as a distinct political ideology and movement, rising from the margins to the centre of modern political history, global in scope and distanced from national historiography?

We can focus on ideas, for example by exploring how European thinkers first formulated the nationalist doctrine or how that was taken in different directions beyond Europe. Perspective is gained by considering rival ideas like international socialism, pan-nationalism, transnational religious movements, and globalisation. We can show how poets, philologists, composers, artists, and others “reawakened” interest in national cultures or how national sentiments become part of “everyday life”. In a world of nation-states we can investigate how nationalism has shaped international relations or intervention in the internal affairs of sovereign nation-states, or is used to justify claims by “nations without states”.

However, the biggest challenge is to show how political nationalism develops, first seeking political autonomy for the nation and, after nation-states have been formed, shaping subsequent politics. One promising approach is to do this regional, not national frames. One cannot predict how nationalism will shape a region’s political geography. Ho-Chi Minh was a founder of the Indochinese Communist Party, seeking an Indochina free of French rule; he ended as leader of North Vietnam pursuing a unified Vietnam against the USA. By contrast, Javanese nationalists were marginalised or shifted towards the broader objective of Indonesian independence. Yet few in 1945, though anticipating the end of European colonial rule, would have predicted four separate nation-states in French Indochina but just one successor state in the Dutch East Indies.

Historical perspective makes the world map of nation-states we take for granted puzzling. Most people regard national identity as “natural” and nationalism as expressing such identity. Yet history shows one cannot align nationalism with any fixed or agreed national identity. Nationalists disagree over aims and methods, as with Pilsudski and Dmowski. Many nationalists neither anticipate nor welcome “their” new nation state, as with Garibaldi and Mazzini. Many nationalists “learn” and practice their nationalism beyond their own nation. Mazzini spent years in London cooperating with non-Italian radical exiles. Sun Yat-Sen was educated in Hawaii, converted to Christianity, spent years in Hong Kong, London and Japan, and hardly knew China beyond Canton and Shanghai.

Nationalists continue quarrelling after nation-state formation. Scottish and Catalan, Flemish, and Kurdish nationalists insist that “their” nation is distinct from that of the existing state. Kurdish nationalism varies between Turkey and Syria, Iraq and Iran, and is internally fragmented within each of those states. Nationalists accuse democratically elected national governments of betraying the nation, whether from the right, like the Front Nationale and UKIP, or the Greek radical left SYRIZA. Whenever there is a debate about national identity, no consensus can be found. Calling for such debate itself indicates disagreement and uncertainty.

Nationalism has concealed its transnational, diverse, changing and quarrelsome qualities with the widespread assumption that it is the handmaiden of nations, each with its unique and clear-cut identity, each seeking its distinct place in the world. It is vital to challenge that assumption.

John Breuilly is Professor of Nationalism and Ethnicity at the London School of Economics. His main interests are in the history and theory of nationalism and in modern European, especially German history. He is the editor of The Oxford Handbook of the History of Nationalism (OUP, 2013).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: shining world map via iStockphoto.

The post A history of nationalism appeared first on OUPblog.

June 2, 2013

Why equal protection trumps federalism in same-sex marriage cases

Federalism is once again at the forefront of the Supreme Court’s most contentious cases this Term. The cases attracting most attention are the two same-sex marriage cases that were argued in March. Facing intense public sentiment on both sides of the issue and the difficult questions they raise about the boundary between state and federal authority, some justices openly questioned whether they should just defer to the political process. And while this is often a wise prudential approach in review of contested federalism-sensitive policymaking, it’s exactly the wrong course of action when the matter at hand is an individual right.

Federalism is once again at the forefront of the Supreme Court’s most contentious cases this Term. The cases attracting most attention are the two same-sex marriage cases that were argued in March. Facing intense public sentiment on both sides of the issue and the difficult questions they raise about the boundary between state and federal authority, some justices openly questioned whether they should just defer to the political process. And while this is often a wise prudential approach in review of contested federalism-sensitive policymaking, it’s exactly the wrong course of action when the matter at hand is an individual right.

While both cases raise curious issues of standing, the substantive issue at the heart of each case is whether same-sex couples should be able to marry. Hollingsworth v. Perry asks the Court to review the constitutionality of a California’s “Prop 8,” a ballot initiative banning same-sex marriages within the state.United States v. Windsor tests the constitutionality of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), a federal law that prevents the U.S. government from recognizing same-sex marriages performed in states that allow it (and affecting the administration of some 1,100 federal benefits connected with marriage).

Yet the looming question for the Supreme Court is not just whether gays and lesbians have the right to marry; the justices must also confront the question of who should decide whether same-sex couples can marry. Is this something that states should be able to decide for themselves, by making and interpreting state law? (After all, matters of family law have traditionally been left to state regulation.) Or, is the decision to marry so fundamentally important that it triggers the federal Constitution’s promise that all citizens will be treated equally under the law? (After all, even though family law is traditionally left to the states, the Constitution won’t allow them to deny interracial marriages.)

So these cases are not only about the rights of same-sex couples to marry, but also about the relationship between the state and federal governments in regulating marriage. And what’s especially strange about the cases is that they pose the ‘same-sex marriage’ question from opposite sides of the ‘federalism’ issue.

In the Prop 8 case, same-sex marriage advocates want federal law to override the state approach, arguing that the US Constitution prevents California from discriminating against gay and lesbian citizens who wish to marry — and opponents want the feds to butt out of an area of traditional state prerogative. In the DOMA case, same-sex marriage advocates want the feds to butt out, arguing (in part) that Congress shouldn’t interfere with state authority by limiting the legal effect of marriages performed according to state law — while opponents are maintaining the propriety of federal intrusion. (Some analysts have even surmised that members the Court may have strategically partnered the two cases together, using each as a foil against the other.)

Indeed, should the Court invalidate DOMA on federalism grounds alone — holding that the federal law unconstitutionally intrudes on a protected zone of state sovereignty — then same-sex marriage advocates would be celebrating a mixed victory. DOMA would no longer bar legally married gays and lesbians from federal benefits in the few states that have legalized same-sex marriage. But it would seemingly affirm the ability of states like California to deny them the legal right to marry in the first place, without the threat of federal interference.

Joining with same-sex marriage advocates, the Justice Department has advanced the other constitutional argument that would resolve both cases on the same grounds: that both DOMA and Prop 8 violate the Constitution’s essential promise to treat all citizens equally before the law.

By this claim, both laws violate the Equal Protection Clause of the 5th and 14th Amendments, because there is no legitimate basis for the federal or state governments to discriminate between heterosexual and homosexual couples who wish to marry. If the Court agrees that there is an equal protection problem with DOMA, then that federal interest would properly override the traditional allocation of family law to the states, because the Bill of Rights clearly limits all state and federal lawmaking. (Again, recall the constitutional invalidation of anti-miscegenation laws for the same reason.) If this happens, the Court will also have to set, for the first time, the specific level of equal protection “scrutiny” that courts should apply when reviewing laws that discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation.

At least on the (sketchy) basis of reading the tea leaves at oral argument, no clear majority is ready to take either approach to invaliding the challenged laws — nor is a majority prepared to uphold them. Most analysts are presuming that the four most liberal members of the Court would accept the equal protection rationale for invalidating DOMA and that the four most conservative members are sympathetic to preserving it. Justice Anthony Kennedy, the likely swing vote, is the author of past opinions that have championed both states’ rights and gay rights. In the DOMA oral arguments, he seemed drawn to the federalism rationale for invalidating DOMA, though it was not clear this view could command a majority. In the Prop 8 arguments, he appeared deeply reluctant to insert the Court in the dispute at all, fueling uncertainty and anxiety among stakeholders on both sides.

Indeed, Justice Kennedy seemed deeply moved by the argument frequently made by the supporters of Prop 8 and DOMA against judicial interference in both cases. The argument is that American culture is in transition on the issue of gay marriage, and that the Court should allow the democratic process to proceed legislatively. Following suggestive public comments by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, some are pointing to the abortion-related culture wars that followed the Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade as a cautionary tale about what can happen when the Court gets out too far in front of public opinion. Leave same-sex marriage to the ballot box, they argue, and the people will work this out for themselves — as they have in the handful of states that have independently legalized gay marriage (and of course, the vast majority that have not).

But from the jurisprudential perspective, deference to the political process misses the very point of judicial review and the constitutional rights that these nine justices have sworn to protect. Constitutional individual rights are — by their very nature — counter-majoritarian. You hold them regardless of what the majority thinks, and they are most dear when the majority is against you. Freedom of religion means that your neighbors can’t force you into their church if they don’t particularly like yours. Your right to jury trial is especially valuable when the public at large believes you should be locked up and the key thrown away. Your right to free speech is important precisely because others may prefer that you just shut up. Equal protection is the Constitution’s promise that you won’t be treated unfairly by the government, even when most Americans really want you to be.

So when, as here, the issue on the line is about protecting individual rights against unfair discrimination by the majority — then the Supreme Court has a constitutional obligation notto just leave the matter to the majoritarian political process. Questions about the existence and scope of individual rights are exactly the kind of issue that requires the judiciary to weigh in, delivering on the Constitution’s sacred promise of fair and equal treatment. Can you imagine if the Supreme Court had concluded that Brown v. Board of Education was “improvidently granted” in order to allow the political process more time to work things out?

Properly understanding the same-sex marriage cases as matters of equal protection also squarely resolves the federalism issue. Under the Supremacy Clause, there is no question but that state law falls when it conflicts with constitutionally protected individual rights — which is precisely as it should be. After all, one of the most frequently acknowledged purposes of our federal structure is its maintenance of checks and balances between local and national authority in order to protect individual rights against incursion by either side. To put abstract federalism concerns before equal protection is to put the constitutional cart before the horse, and to misunderstand the underlying purposes of American federalism to begin with. “States’ rights” serve only one true purpose: the fuller protection of individuals.

The Court should recognize the critical relationship between the federalism and equal protection arguments in these cases. Questions about the boundary between state and federal authority may hold more sway in murkier interjurisdictional realms like health care and education, but if the Constitution protects gay and lesbian people from discrimination, then the issue is elevated beyond the reach of federalism for its own sake. Federalism is never “for its own sake;” it is a structural means to a substantive end. In the United States, that end should be fairness and justice for all.

A version of this article originally appeared on the ACS Law blog.

Erin Ryan is an Associate Professor of Law at Northwestern School of Law, Lewis & Clark College. Professor Ryan is the author of Federalism and the Tug of War Within. For more on the cases raising marriage equality concerns see the ACSblog symposium on Hollingsworth v. Perry and U.S. v. Windsor.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Why equal protection trumps federalism in same-sex marriage cases appeared first on OUPblog.

Quantum parallelism and scientific realism

George Berkeley

The philosopher Althusser said that philosophy represents ideology, in particular religious ideology to science, and science to ideology. As science extended its field of explanation, a series of ‘reprise’ operations were carried out by philosophers to either make the findings of science acceptable to religion or to cast doubt on the relative trustworthiness of science compared to the teachings of the church.This started with Berkeley’s subjective idealism and extended through to the instrumentalist interpretation of scientific research popularised by Mach in the late 19th century. In more recent years a particular interpretation of quantum mechanics, the Copenhagen one, has provided a rich seam for such reprises. A classic example is given here:

Which are real, waves or particles? On this opinions are divided, but what humans actually perceive in laboratory experiments are particles, or the impacts of particles. Waves are postulated to account for the patterns such impacts make. So while some theorists affirm that probability waves really exist, most physicists have a preference for particles, which at least are actualities, not just probabilities.

But that preference carries with it some unusual implications, very different from those of classical physics. For it seems that particles only really exist when they are observed. John Wheeler says, ‘No elementary phenomenon is a real phenomenon until it is an observed phenomenon’. Philosophers will recall the eighteenth century Anglican Bishop Berkeley’s dictum that ‘to be is to be perceived’. Nothing is real, the Bishop held, unless it exists in the mind of some observer, whether it is some finite spirit or the mind of God.

Known as Idealism, this philosophical view has been unpopular in recent times, partly because science seemed to suggest that nothing exists except material particles, and that the mind is no more than an accidental by-product of the material brain. In a totally surprising way, quantum physics is taken by some to show that Berkeley was more or less right, after all. Nobel Laureate Eugene Wigner writes: ‘The very study of the external world led to the conclusion that the content of the consciousness is an ultimate reality’. Particles only exist when observed, he suggests, and so the reality of particles entails that consciousness is a fundamental element of reality, not just a by-product of some ‘real’ material world. (Gresham Professor of Divinity Keith Ward speaking in 2005)

Having gone from arguing the consciousness is the fundamental reality, it is an easy step for Professor Ward to conclude at the end of his lecture that “It moves God much closer to the centre of the scientific view of the world, and makes belief in God, if not compelling, at least highly plausible.”

Does quantum mechanics actually imply what he says?

Well that is certainly what one historically influential interpretation says. Ward is able to quote Wigner and von Neumann in his defence. But this is fundamentally a philosophical interpretation of the quantum theory not the theory itself. The interpretation can be seen as just a continuation of Mach’s instrumentalist views which were very influential around the turn of 19th to 20th century when founders of quantum mechanics were starting on their careers. According to this, science was about explaining correlations between measurements on scientific instruments; it could not go beyond this and assume the reality of what its theories described.

Ludwig Boltzmann

Boltzman had huge difficulties persuading his contemporary physics community of his theory of statistical mechanics which depended on the existence of atoms. Mach’s instrumentalism held that atoms were just a convenient fiction. The argument being: classical thermodynamics can explain what we see on thermometers etc, why posit these atoms? It was not until 1905 and Einstein’s paper on Brownian motion that he was vindicated. If one thinks how dependent on the idea of atoms all subsequent solid state physics, organic chemistry, etc. has been, then Mach’s view, and the obstacles Boltzmann encountered were hardly helpful.But the point here is that skepticism about the existence of atoms or particles preceded the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum physics on which Ward relies, and was essentially grounded in philosophical methodology.

There has, since the 1950s, been another interpretation available: the many worlds interpretation due to Everett. Suppose we are observing a particle with possible spin up or spin down states. According to the Copenhagen interpretation a system evolves according to the wave equation with multiple possible states each with their own wave amplitude until it is observed, at which point the wave function collapses, and there is a single observed value.

In the many worlds view, all these multiple states continue into the future, the collapse of the wave function is a subjective illusion since arising from the fact that we can only observe one of the possibilities at a time. There are multiple universes, in half of which we observe the spin pointing down and in another half we observe the spin pointing up.

Proponents of the Copenhagen view say this multiplicity of universes is a big price to pay. Surely Occam’s razor would enjoin us to the simpler solution : that the wave function simply collapses on observation.

The Copenhagen view puts the observer at the center, as the Ptolomaic view did in astronomy. The Copernican revolution introduced, for the first time, the possibility of many worlds around other suns and reduced us as observers to an insignificant portion of the universe. Everett’s many worlds interpretation posits many parallel worlds occupying the same space as us, with our conscious experience being just one of multiple possible threads through this multiverse.

The Everett interpretation is objectivist, and undercuts the attempt to find support for theology in quantum theory. But you might think it was a matter of ’you pay your money and you take your choice’, with one interpretation being as good as another.

The game changer is quantum computing. The whole field stems from Deutsch’s 1984 paper in Transactions of the Royal Society. Deutsch’s paper explicitly draws on the Everett hypothesis to justify the proposal for quantum parallelism. He has said that as a young physicist he was inspired by Everett and his book The Fabric of Reality is a popular expression of the many worlds view. If one accepts the Everett hypothesis then the idea of quantum parallelism is much easier to come to than if you accept the Copenhagen view. Quantum computing does not depend on the prior advances of semiconductor technology, it is having to invent the basic technology from the start, and as such, it could as well have started research in the 1960s than the 1990s. So here we have another instance where the dominance of instrumentalism may plausibly have held a field back.

In a conventional computer each bit holds either a one or a zero. In a quantum computer it can hold both values simultaneous. Quantum parallelism uses many threads of the multiverse simultaneously. The difficult part comes from getting the different threads to interfere so that information can be passed from one thread to another. As of now there are only a few quantum algorithms and they seem to mainly have applications in cryptography. Grover’s algorithm for example can be used to crack passwords by searching through all possible passwords simultaneously. Suppose we have an eight-character password (as used in the DES standard). Since most people will use seven-bit ASCII as their passwords, this means that the password is effectively 56 bits long. As long ago as when DES was proposed in the 1970s it was pointed out that, in principle, this lent itself to cracking using massive parallelism. Suppose we can check a potential DES code in one microsecond using special combinatorial logic, and suppose that the NSA can afford one million such chips, both plausible assumptions. Then we could search through all combinations in under five hours, and on average, find the password in just over two hours. Using a single quantum computer running Grover’s algorithm, again performing checks at a microsecond each, you could get an answer in around four minutes. It does this by searching all possible passwords in parallel and allowing the different threads of the multiverse to interfere until the probability of ending up in the thread that contains the right answer is high.

The parables of the Copenhagen interpretation have a certain plausibility when the intervention of the human observer is between two binary values : a spin up or spin down. One can just about credit ‘free will’ with being able to do this. But when it is a matter of selecting one out of hundreds of billions of possible passwords, or the extraction of prime factors using Shorr’s algorithm then one has either to accept the reality of the multiverse or attribute supernatural prescience to the ‘observer’.

Up to now, people can not build quantum computers big enough to run more than toy examples. It requires extraordinarily nice engineering — manipulating individual ions in some designs — and reliability is a huge problem. But they prove the principle, the rest is just engineering development.

Paul Cockshott is a computer scientist and political economist working at the University of Glasgow. His most recent books are Computation and its Limits (with Mackenzie and Michaelson) and Arguments for Socialism (with Zachariah). His research includes programming languages and parallelism, hypercomputing and computability, image processing, and experimental computers.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) George Berkeley portrait by John Smybert 1727. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Ludwig Boltzmann portrait, 1902. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Quantum parallelism and scientific realism appeared first on OUPblog.

June 1, 2013

BRCA1 and BRCA2 in the digital age

With as little thought as combing our hair or brushing our teeth, we tweet, engage with family and friends on Facebook, write blogs, and give our opinions on social media sites. On the major streets of all major cities in the world, children, teenagers, professionals, the unemployed, and pensioners alike take calls and send texts without a second thought. Technology is so much a part of our day to day lives that we can barely remember how we could have managed without it. It is also rapidly advancing and taking us along with it. New inventions are rapidly assimilated into our lives and adopted by the vast majority of society.

The human genome was deciphered in 2003. For most people the Human Genome Project has not made even a ripple in the sea of their lives. Yet this advance is at least as significant as anything developed for connecting society. Unfortunately, the genomic revolution has failed to have any real impact on the lives of the average person on the street — that is, until Angelina Jolie’s announcement. She had recently undergone a double mastectomy because she carries the defective gene BRCA1 and I can’t help but wonder what this might do for society’s familiarity with genomics.

There are very few people that can draw global attention to an issue like Angelina Jolie. From her effective and compassionate action on behalf of the victims of rape in war zones, to bringing light to the plight of orphans in the Third World, she is one of the greatest advocates and ambassadors on substantive causes of her generation. The only other woman that possibly had a greater impact and global reach was the late Princess Diana. Now that Angelina Jolie has brought attention and light to her genomic dilemma and plight, one can’t help but hope that this may be what genomics has needed to bring this substantive, complex, and ethereal subject down to street level, to the technological conversant generation.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are now registering in many people’s consciousness. BRCA1 is a regulator gene in the human cell that controls cell growth. When this gene is defective, cells multiply in an uncontrolled manner, causing cancer. People that carry the defective gene have a higher probability of developing breast, ovarian, and other cancers than people without the defect. Many such women have already watched other close female relatives in their families die from one or both of these cancers. Angelina Jolie lost her mother to ovarian cancer at the young age of 56.

This needed publicity also helps to shine light on other aspects of genomics, including the patenting of genes. BRCA1 genes were patented by Myriad Genetics in 1997. The Supreme Court is considering the legality of the patenting of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. The legal outcome will be available in June 2013. Of course, the investment of time and effort to determine the importance of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes should be financially rewarded. In this case, it seems inappropriate to allow a firm, any firm, to patent a gene that it did not create. Sadly, BRCA1 and BRCA2 are only the tip of the iceberg. Approximately more than 20% of the human genome has been patented.

Myriad Genetics is the only firm that can test for the mutation in the United States, giving Myriad Genetics an effective monopoly. The cost of the test is approximately $3000. This is prohibitively expensive for many women who would take the test if they could. Not only is the test expensive, but the cost of any preventive surgery is also prohibitively expensive for many women.

It is my hope that the Supreme Court will make the right decision in this case. Ordinary women who do not have the access to the resources that Angelina Jolie has should be able to be tested for their BRCA1 and BRCA2 status if they so wish, especially if they are from high risk families. At some point the ethics of earning huge profits in the face of inaccessibility to potentially life-saving tests must be questioned. The economics of greater access to the test may make the test profitable at lower cost rates. Regardless of potentially reduced costs, it has to be asked if it is ethical and responsible for Myriad Genetics to continue to keep the cost of the test as high as it is.

Dr. Lorna Speid is the author of Clinical Trials: What Patients and Healthy Volunteers Need to Know. She is the president of Speid and Associates, Inc., a regulatory affairs and drug development consultancy and has worked for the international pharmaceutical industry since the late 1980s.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Pink ribbon with word ‘Care’ surrounded by female paperdoll. © Rudyanto Wijaya via iStockphoto.

The post BRCA1 and BRCA2 in the digital age appeared first on OUPblog.

Stories We Tell: How we reconstruct the past

Our memories, in many ways, define who we are as an individual or at least who we think we are. In the recent documentary, Stories We Tell, filmmaker Sarah Polley presents her own tale of the search for her biological father. Through interviews with relative and friends, snapshots, and re-enactments of pertinent events that look like old home movies, the documentary moves like a real-life Rashomon, wherein bits of the “truth” are revealed from various points of views. The stories revolve around Sarah’s mother, Diane Polley, a stage actress who died of cancer when Sarah was 11 years old. The “seminal” event, if you will, took place nine months before Sarah’s birth, when Diane took an extended leave and moved hundreds of miles away from home and family to perform in a play in Montreal. As such, there was opportunity and several prime suspects in the mystery of Sarah’s biological father.

Sarah Polley in Stories We Tell.

During family gatherings, jokes were often made that Sarah didn’t really look like anyone else in the family, particularly Michael, Sarah’s putative father. Michael, however, never questioned his paternity as he did visit Diane in Montreal during her time away. Much of the film is presented from Michael’s perspective, though we very soon appreciate the disparity of interpretations through other players, including Sarah’s biological father (part of the fun is the revelation of who this man is, and I won’t spoil the fun). With Sarah’s mother unable to provide her own recollections, we are left with Michael’s story, the biological father’s story (which has its own depth and poignancy), and Sarah’s perspective as defined by what she decided to portray in the re-enactments and how she decided to edit the interviews. Indeed, an essential and wonderfully pertinent aspect of the movie is the way Polley shows how memories are reconstructed “stories” built from true experiences plastered with fictional additions and modifications.

Memory researchers have long viewed recollections as stories that are reconstituted each time we tell them. As we replay our memories, we add to and color the past. In a chilling retelling of a life event, New York Times columnist and former drug addict David Carr documented his recollection of a day twenty years earlier when he was fired from a job (Carr, 2008, The Night of the Gun, see interview). He remembers going to a bar with an old college buddy, Donald, to “celebrate” his firing. Spiked with pills, booze, and cocaine, Carr’s behavior was so erratic that he was asked to leave the bar. While outside the premises, Donald complained about Carr’s behavior, which led to him being pushed by Carr against his own Ford LTD. Carr remembers Donald driving off without him but later phoning his friend at home to tell him “I’m coming over” in a rather menacing tone. His friend advises against it and says he has a gun. Ignoring the admonition, Carr arrives at Donald’s door and confronts his friend who has “a handgun at his side.” An altercation breaks out with Carr smashing a window with his fist, Donald calling the cops and saying: “You should leave. They’re coming right now.” Twenty years later, Carr discussed his recollections with Donald, who confirmed much of Carr’s recollection of the day, except for a critical feature—it wasn’t he who had the gun.

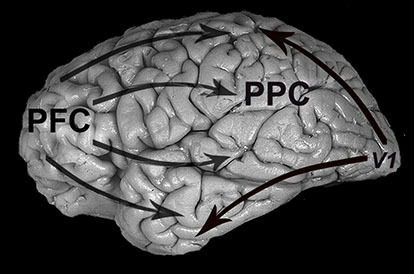

The preeminent psychologist Elizabeth Loftus has conducted ingenious experiments about the malleability of our memories and how life events can interfere with each other and blend across time. She has shown that our recollections are indeed reconstructions that are partly true and partly fiction. She has even managed to convince individuals of remembering that they were once lost in a shopping mall, though the “memory” was planted by Loftus in cahoots with a family member. Brain scientists have shown that when we have a strong recollection of a past event (even if it’s a false memory), the posterior parietal cortex (PPC) is particularly active. This brain region has been viewed as a convergence zone or integrative area. That is, pieces of an event are stored in various parts of the brain—such as visual ones stored along paths emanating from the back of the brain (V1)—and become linked together as we reconstruct the past. When we try to retrieve a past experience, the prefrontal cortex (PFC) helps guide and search for the stray pieces, and the PPC glues the pieces together as an encapsulated memory, such as remembering a particularly good meal with friends at a new restaurant (figure from Shimamura, 2013).

(c) Arthur P. Shimamura.

Whenever we reminisce about the past, we build stories based on “re-collecting” details of prior events. Movies act as a powerful means of visually narrating our life stories, and Polley’s film offers both a documentation of a personal experience and a lesson in how the telling of our past can be colored. During the movie, one realizes that what looks like footage from home movies from a shaky Super 8 camera are actually re-enactments, the kind of dramatizations often presented in cheesy history documentaries seen on TV. I tend to dislike such portrayals, yet in Polley’s film these re-creations foster the notion that our own memories are reconstructions of the past. One moral of Stories We Tell is that we may never fully know how we got to where we are today. As David Carr has said about his own recollections: “You can’t know the whole truth, but if there is one it lies in the space between people.”

Arthur P. Shimamura is Professor of Psychology at the University of California, Berkeley and faculty member of the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute. He studies the psychological and biological underpinnings of memory and movies. He was awarded a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship in 2008 to study links between art, mind, and brain. He is co-editor of Aesthetic Science: Connecting Minds, Brains, and Experience (Shimamura & Palmer, ed., OUP, 2012), editor of the forthcoming Psychocinematics: Exploring Cognition at the Movies (ed., OUP, March 2013), and author of the forthcoming book, Experiencing Art: In the Brain of the Beholder (May 2013). Further musings can be found on his blog, Psychocinematics: Cognition at the Movies.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only television and film articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Stories We Tell: How we reconstruct the past appeared first on OUPblog.

An Eastern reading list from Oxford World’s Classics

By Kirsty Doole

The great works of the Eastern world have provided inspiration for this month’s Oxford World’s Classics reading list. From those you have probably heard of (like the Kamasutra) to those you may not have (such as The Recognition of Sakuntala), these classic works provide a window on the classical worlds of India, China, and the Middle East.

Sayings of the Buddha, edited and translated by Rupert Gethin

Buddhist religious and philosophical beliefs derive from the teachings of Gotama the Buddha, a wandering ascetic in India during the fifth century BCE. One of the main sources for knowledge of his teachings is the four Pali Nikayas, or ‘collections’ of his sayings. Written in the ancient Indian language Pali, which is closely related to Sanskrit, the Nikayas are among the oldest of all Buddhist texts.

This selection of the Buddha’s sayings reflect the full variety of the Pali Nikayas, covering the Buddha’s biography, philosophical discourse, instruction on morality, meditation, and his ideas on the spiritual life.

Myths of Mesopotamia, edited and translated by Stephanie Dalley

The ancient civilization of Mesopotamia was located between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates. The myths collected here, originally written in cuneiform on clay tablets, include the Creation and the Flood, and the famous Epic of Gilgamesh, the tale of a man of great strength, whose heroic quest for immortality is dashed through one moment of weakness.

Stephanie Dalley, who translated and edited this volume for Oxford World’s Classics, may be familiar to readers as the author of The Mystery Of The Hanging Garden Of Babylon, a new book that questions whether the Hanging Garden of Babylon was really in Babylon at all.

Statue of Laozi in Quanzhou, China.

Daodejing by Laozi; edited and translated by Edmund Ryden; introduction by Benjamin Penny

The Daodejing by Laozi is one of the most important texts in the philosophical tradition of Daoism, and is one of the most widely-known texts in China. Also called the Classic of the Way and the Life-Force, it expresses the main beliefs of Daoism, and upholds it as a way of life as well as a philosophy and religion. The dominant image is of the Way, the mysterious path through the whole cosmos modelled on the Milky Way. A life-giving stream, the Way gives rise to all things and enables the individual, and society as a whole, to harmonize the various demands of daily life and achieve a more profound level of understanding.

The Recognition of Sakuntala by Kalidasa; translated by W. J. Johnson

The Recognition of Sakuntala is a play in seven acts originally written in Sanskrit in the fourth century CE. It follows the relationship between King Dusyanta and Sakuntala, a hermitage girl, as they fall in love, are separated by a curse, and are ultimately reunited. Overwhelmingly erotic in tone, in peformance The Recognition of Sakuntala aimed to produce an experience of aesthetic rapture in the audience, akin to a mystical experience.

Arabian Nights’ Entertainment, edited by Robert L. Mack

The Arabian Nights’ Entertainment is famous as being the first literary appearance of Sinbad, Aladdin, and Ali Baba, among others.

The Sultan Schahriar’s misguided resolution to shelter himself from the possible infidelities of his wives leads to an outbreak of barbarity in his kingdoms and a reign of terror in his court, stopped only by the resourceful Scheherazade. Scheherazade nightly postpones Schahriar’s murderous intent by telling him tales that have entered our language like no others. The stories contained in this ‘store house of ingenious fiction’ initiate a pattern of literary reference and influence which today remains as powerful and intense as it ever was.

Pañcatantra: The Book of India’s Folk Wisdom, edited and translated by Patrick Olivelle

The Pañcatantra is the most famous collection of fables in India and was one of the first Indian books to be translated into a Western language. A significant influence on the Arabian Nights and the Fables of La Fontaine, the Pañcatantra teaches the principles of good government through the medium of animal stories. Its positive attitude towards life and its advocacy of ambition and enterprise counters any preconceived ideas of passivity and other-worldliness in ancient Indian society.

The Bodhicaryavatara by Sanideva; edited by Paul Williams; translated by Kate Crosby and Andrew Skilton

Written in India in the early eighth century AD, Santideva’s Bodhicaryavatara became one of the most popular accounts of the Buddhist’s spiritual path. It takes as its subject the profound desire to become a Buddha and save all beings from suffering, enacted by a Bodhisattva. Santideva not only sets out what the Bodhisattva must do and become, he also invokes the intense feelings of aspiration which underlie such a commitment.

Important as a manual of training among Mahayana Buddhists, especially in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, the Bodhicaryavatara continues to be used as the basis for teaching by modern Buddhist teachers.

Kamasutra by Mallanaga Vatsyayana; edited and translated by Wendy Doniger and Sudhir Kakar

“When the wheel of sexual ecstasy is in full motion, there is no textbook at all, and no order.”

There aren’t many people who haven’t heard of the third century CE manual of erotic love. But it’s about much more than just sexual positions. It covers the topics of finding a partner, maintaining power in a marriage, committing adultery, living as or with a courtesan, and using drugs. Composed in Sanskrit, the literary language of ancient India, it combines an encyclopaedic coverage of all imaginable aspects of sex with a closely observed sexual psychology and a dramatic, novelistic narrative of seduction, consummation, and disentanglement.

Kirsty Doole is Publicity Manager for Oxford World’s Classics, amongst other things.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, and the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Statue of Laozi in Quanzhou, China. By Thanato [CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The post An Eastern reading list from Oxford World’s Classics appeared first on OUPblog.

May 31, 2013

Europa borealis: Reflections on the 2013 Eurovision Song Contest Malmö

In the spirit of the Eurovision Song Contest motto for 2013 “We Are One,” we seek the common space afforded by dialogic reflections on the European unity that has inspired and eluded the Eurovision since 1956. We search to rescue stretto from the fragments of the largest and most spectacular popular-music competition in the world.

Dafni Tragaki : I’d like to begin by sharing with you one of my general impressions of the 2013 Eurovision Song Contest: the magnificent loneliness of the singers on the grand Eurovision stage. This minimalist spectacle of “oneness” was mediated by the dominance of the singing voice — what you described in Empire of Song as “the return of the Eurovision song.” And it resonated with this year’s slogan “we are one” that sounds almost like an imperative for European togetherness/oneness.

Philip V. Bohlman : It was almost impossible not to be struck by the theme of oneness and the singularity of its variants — loneliness, uniqueness, solitariness, togetherness. No less striking was the irony of the plural “we” becoming the singular “one.” The imperative surely depended on who held the power. It is interesting that, collectively, the “Big Five” (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom) all sent solo singers as their envoys to Malmö, but each one of them ultimately failed to define the parameters of their powerful oneness. While the UK debates whether to remain in the European Union, Bonnie Tyler, stands on the stage oblivious to the Eurovision and its history. Germany’s “Glorious” musically rips off Sweden’s winning “Euphoria” from the year before with impunity, France trumps the blues with chanson, Spain throws in a bagpipe to suggest that its oneness includes Galicia, and Italy proves that the Sanremo song never was at one with the Eurovision song.

Dafni Tragaki : I think that this loneliness of the “big” in this year’s Eurovision Song Contest (ESC) mediates a European self in a state of melancholic introspection sounded through the solitariness of the ballad, the genre that dominated this years’ competition. Sentimentalism as a transnational economy of affect — I am inspired by Martin Stokes’s 2010 The Republic of Love here — appears to be the musical response to or the defense against the vanity of the European oneness that is endlessly in question. “No air, no pride” as suggested by Anouk’s song for the Netherlands.

Philip V. Bohlman : And where better to witness the internalization of oneness than in Emmelie de Forest’s winning entry for Denmark, “Only Teardrops”? The lyrics unfold as a haunting counterpoint between the collective and the divisiveness of singularity. “How many times can we win and lose? How many times can we break the rules between us?” The solo singer and the narrative power of the ballad is rallied in support of this allegorical deconstruction of Europe as collective undermined by solitary selfishness. “Only Teardrops” seizes on this power when the answer to the question of European survival — “How many times till we get it right between us?” — is answered by the insistent recurrence of what has become a non-answer: Only teardrops, only teardrops…

Click here to view the embedded video.

Dafni Tragaki : I can hear this urgency for European survival in the sounds of the military drumming in the refrain — the heartbeats of the European precariousness in those times of teardrops. The sense of alertness intensifies as the drum-beats alternate with the serene melodic lines of the pipe that transpose us to the collective paradise of a pastoral and “natural” pastness. At the same time, Emmelie’s performance mediate the singer as the subject at a state of dispossession, I would say, positioned within a risky, to-be-destroyed realm featured by the towering flames of fire projected on the video-walls. As the winner, she is perhaps safe for now. “We could be one” — to paraphrase this year’s motto.

Philip V. Bohlman : There is more than a little political paradox in the ways the 2013 contestants responded to the motto, “We Are One.” Whereas it may seem to be politically charged, even responsive to the Euro Crisis and the fissures in the European Union, few songs actually included an open claim to do explicit political work. Greece is surely the best case of a political song, with Koza Mostra and Agathonas Iakovidis performing “Alcohol Is Free” as a criticism of the austerity programs imposed on Greece and other Mediterranean nations. True, a handful of entries took interpreted “We Are One” from the perspectives of eco-politics, but more often than not, the political slipped easily into an apolitical, even feel-good parody.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Dafni Tragaki : Yet, don’t you think that this apparent distance from the political is so politically charged? We could perhaps interpret the “apolitical” entries as performances of embarrassment with the political, disguised in sounds of political immunity. Indeed, a parody of feel-goodness, as you say. Or, we could think of the “apolitical” as a sort of post-political, following Slavoj Žižek, response that negotiates the political in song by employing the saturating modalities of emotion broadly recognized as “apolitical”. See the Azerbaijani entry “Hold Me,” for instance. The apolitical sung melodrama of a lover in despair encapsulates the politics of a nation projected as an agent of affective intensity. It sounds the Azeri power to affect and to be affective. In the end, Azerbaijan might not be considered to be a democratic state (who cares? this is Eurovision after all). Democracies are problematic in today’s neoliberal Europe. Sweden’s Eurovision spectacle was followed immediately by riots on its own streets, blamed on the immigrants in a northern European nation dependent on a work force from beyond Europe’s borders. Once again, we could perhaps understand the power of the “apolitical” as a paradox in the context of the supposed return of the Eurovision song at its imaginative native home, the North.

Philip V. Bohlman : The politics of Eurovision regionalism have been shifting for the past several years, redeployed from the much-maligned bloc-voting that pulled Eurovision victories into Eastern Europe after 2000 to the cool spectacle of the North. Eurovision Orientalism has given way to Borealism. Clichés of northernness have multiplied especially since Alexander Rybak’s 2009 “Fairytale,” which brought the grand prix to Norway with the largest margin of victory ever. The Eurovision’s migration to the North does not so much follow the region’s industrial power as absorb the metaphors of dark winters against the backdrop of the aurora borealis. Sweden transformed metaphor to narrative, presenting each nation as boreal with snow and ice on the postcards preceding the performances (even Azerbaijan’s postcard featured a skiing scene), and historicizing the grand finale into a show of Swedish nostalgia, complete with a “new Eurovision hymn” by Benny Anderson and Björn Alvaeus (with DJ Avicii) of ABBA, whose “Waterloo” won in 1974.

Dafni Tragaki : And the borealist turn in ESC that you describe also takes place in the metaphor of Malmӧ’s theme art, the butterfly. National songs are likened to butterflies which exist in thousand different forms, yet “they have one common name” (see Malmö 2013: We are one). It seems that, nonetheless, despite their common name, nation-butterflies each year undergo metamorphoses that lead to the diverse fates of the ESC’s eventful togetherness, the spectacular oneness of Eurovision Liebestod.

Philip V. Bohlman is the Mary Werkman Distinguished Service Professor of Music at the University of Chicago, Honorarprofessor at the Hochschule für Musik, Theater und Medien Hannover, and a member of the Grove Music editorial board. He has written widely about the Eurovision Song Contest and nationalism in European music, including in his books, World Music: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2002) and Focus: Music, Nationalism, and the Making of the New Europe (Routledge, 2011).

Dafni Tragaki is a lecturer in Anthropology of Music at the Univ. of Thessaly (Volos, Greece). She is the editor of Empire of Song. Europe and Nation in the Eurovision Song Contest (Scarecrow Press, 2013).

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Europa borealis: Reflections on the 2013 Eurovision Song Contest Malmö appeared first on OUPblog.

Friday procrastination: the month of May edition

It’s been several weeks since our last procrastination round-up, so I hope you enjoy this mega-link list. (I’ve cut it down.)

Tom Chatfield picks the most interesting neologisms drawn from the digital world.

Is your PhD a waste of time?

Editors hate the passive voice.

Make sure you have a strong argument.

You should follow Jo the Librarian on Tumblr.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Who doesn’t love Kierkegaard? Daphne Hampson does.

The . (h/t The Millions)

Fight Nazis and save art.

Duke has beautiful pics of Brazilian musicians.

The National Archives presents history with facts alone.

#bbpBox_337889711710416896 a { text-decoration:none; color:#337DCC; }#bbpBox_337889711710416896 a:hover { text-decoration:underline; }V. entertaining Eton exam paper: "You are the PM. Write a speech on why employing the Army was the only option" http://t.co/AO8lXXNcEP

May 24, 2013 7:15 am via web

Reply

Retweet

Favorite

Aeon Magazine

May 24, 2013 7:15 am via web

Reply

Retweet

Favorite

Aeon MagazineAcross the MOOC universe.

Transformative works and the law.

What’s the difference between the Library of Congress and the National Archives?

Click here to view the embedded video.

The origins of the (75 this year!) man of steel.

The advantages of paper.

Talk like a 15,000-year-old adult.

North American English dialects.

Why women leave academia.

The cost of using and running archives.

We have been stripping phytonutrients from our diet since we stopped foraging for wild plants some 10,000 years ago and became farmers.

Jonathon Green and Jack Kerouac get stoned.

Putting passion back into your academic writing.

Alice Northover joined Oxford University Press as Social Media Manager in January 2012. She is editor of the OUPblog, constant tweeter @OUPAcademic, daily Facebooker at Oxford Academic, and Google Plus updater of Oxford Academic, amongst other things. You can learn more about her bizarre habits on the blog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Friday procrastination: the month of May edition appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers