Oxford University Press's Blog, page 942

May 24, 2013

Symmetry is transformation

By Ian Stewart

Symmetry has been recognised in art for millennia as a form of visual harmony and balance, but it has now become one of the great unifying principles of mathematics. A precise mathematical concept of symmetry emerged in the nineteenth century, as an unexpected side-effect of research into algebraic equations. Since then it has developed into a huge area of mathematics, with applications throughout the sciences.

Today we usually think of symmetry as a regularity of visual pattern—the sixfold symmetry of a snowflake, the circular symmetry of ripples on a pond, the spherical symmetry of a droplet of water or a planet. Here the role of symmetry is mainly descriptive. But there is a sense in which a natural process can also be symmetric, and the mathematics of symmetry can predict the results of that process, helping us to understand how nature’s patterns arise.

The key step towards a rigorous notion of symmetry arose not in geometry, but in algebra: attempts to solve quintic equations. The ancient Babylonians knew how to solve quadratic equations, and Renaissance Italian mathematicians discovered how to solve cubic and quartic equations, but here, everyone got stuck. Eventually, it turned out that no solution of the required kind exists for the general quintic equation.

The deep reason for this impossibility lies in the symmetries of the equation, which are the possible ways to permute its solutions while preserving all algebraic relations among them. When an equation has ‘the wrong kind of symmetry’ it can’t be solved by a formula of the traditional type. And equations of the fifth degree have the wrong kind of symmetry.

Mathematicians realised that symmetry is not a thing, but a transformation: a way to move or otherwise disturb something while—paradoxically—leaving it unchanged. For example, to a good approximation a human figure viewed in a mirror looks just like the original. Mixing up the roots of an equation doesn’t change suitable formulas in which they appear. Rotating a sphere through some angles produces an identical sphere.

The collection of all such transformations is called the symmetry group of the object; the structure of this group provides a powerful way to find out how the object behaves. The upshot of this discovery was a new, abstract branch of algebra: group theory.

Groups turned out to be fundamental to the study of crystals; the form and behaviour of a crystal depends on the symmetry group of its atomic lattice. Groups are also vital to chemistry: the way a molecule vibrates depends on its symmetries. The symmetries of a uniformly flat desert determine the possible patterns of sand dunes when the flat pattern becomes unstable. The symmetries of biological tissue determine the possible patterns of animal markings, such as stripes and spots. The symmetries of a cloud of gas determine the spiral form of a galaxy. The symmetries of space and time underpin Einstein’s theories of special and general relativity. The symmetries of fundamental particles constrain quantum field theory and affect the possibilities for unifying it with relativity.

Symmetry is such a huge idea, with so many diverse ramifications, that only an encyclopaedia could really do it justice. But it is possible to sketch its origins, give some idea of how the formal theory works out, sample its applications, and witness its diversity and generality. Moreover, the subject has great visual beauty and appeal: here, for once, mathematics can be a spectator sport, and audience participation is not mandatory.

I have spent much of my research career working on connections between symmetries and nature’s patterns, in fluid flow, animal movement, visual perception, and evolutionary biology—and I am just one of many. The well is nowhere near running dry. New applications are constantly being found. Symmetry is one of the truly deep concepts, possessing both visual and logical beauty. Its effects can be seen everywhere, if you know how to look.

Ian Stewart is Emeritus Professor of Mathematics at Warwick University. He is a well-established communicator of mathematics, and the author of over 80 books, including several on the subject of symmetry, such as Symmetry: A Very Short Introduction. His summary of the problems of mathematics, From Here to Infinity, and collections of his columns from Scientific American (How to Cut a Cake, Cows in the Maze), have been very successful, and his recent book Professor Stewart’s Cabinet of Mathematical Curiosities, has been a bestseller.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only mathematics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: Symmetrical landscape, By Johann Jaritz (Own work), Creative Commons Licence via Wikimedia Commons

The post Symmetry is transformation appeared first on OUPblog.

May 23, 2013

People of computing

According to Oxford Reference the Internet is “[a] global computer network providing a variety of information and communication facilities, consisting of interconnected networks using standardized communication protocols.” Today the Internet industry is booming, with billions of people logging on read the news, find a recipe, talk with friends, read a blog article (!), and much more.

But how much do you know about the people behind the Internet? Who were the founding fathers and mothers of computer science? Do you know who coined the term ‘computer bug’ or who said “We don’t have the option of turning away from the future. No one gets to vote on whether technology is going to change our lives”?

Take our computing quiz, compiled from resources in Who’s Who, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford Reference, and the American National Biography, to see if you’re a computer genius or if you need an upgrade!

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Who’s Who, published annually by A & C Black since 1897, and online exclusively by Oxford University Press since 2008, is the leading source of up-to-date information about over 35,000 influential people from all walks of life, worldwide, who have left their mark on British public life. Written by specialist authors, the Oxford DNB biographies will introduce you to the people behind British history’s great events as well as its literature, science, art, music, and ideas. Oxford Reference is the home of Oxford’s quality reference publishing bringing together over 2 million entries, and more than 16,000 illustrations, into a single cross-searchable resource. Discover the lives of more than 18,700 men and women — from all eras and walks of life — who have influenced American history and culture in the acclaimed American National Biography Online.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only technology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post People of computing appeared first on OUPblog.

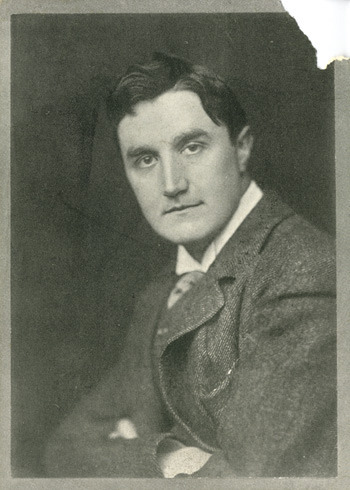

The old shall be made new

The issue and performance of previously unpublished musical works — juvenilia, early pieces, and even completions by others of music left by composers, for one reason or another, incomplete — always provokes interesting debate. Would the composer have wanted it? Does the newly presented work serve the best interests of the composer’s reputation? Does the music throw new (or even controversial) light on ‘the life and works’?

With Sir Edward Elgar, the recent recording of the quadrilles and polkas that he wrote as a young man for entertainment at the Powick Asylum generated mild interest, but in 1998 Anthony Payne’s completion of the third symphony sketches and fragments left by Elgar at the end his life (and now in the British Library) caused a sensation. Payne called his work an ‘elaboration’ of Elgar’s sketches and — overnight, and fair and square — it gave the world a fine and substantial new piece. If not written by Sir Edward, it is by all counts completely worthy of him, a remarkable tribute, and something by way of repayment by one of his admirers. All the British composers that followed Elgar — such as Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) — owe him a debt.

As a young man and ‘apprentice’ composer, Vaughan Williams wrote much music (chamber works, orchestral pieces, choral works) which received performances at the time, but which he subsequently withdrew. Ursula Vaughan Williams, his widow, ensured that, where possible, the manuscripts for these early works were preserved (the majority were to be deposited in the British Library, along with those of the published works), but during her lifetime generally continued her husband’s policy of not allowing performance or publication.

As a young man and ‘apprentice’ composer, Vaughan Williams wrote much music (chamber works, orchestral pieces, choral works) which received performances at the time, but which he subsequently withdrew. Ursula Vaughan Williams, his widow, ensured that, where possible, the manuscripts for these early works were preserved (the majority were to be deposited in the British Library, along with those of the published works), but during her lifetime generally continued her husband’s policy of not allowing performance or publication.

Towards the end of her life (she died in 2007, almost fifty years after Vaughan Williams) Ursula relaxed her view, realizing the cultural and artistic value of releasing at least a selection of her husband’s early and by now forgotten works (really, the only information about them then available to the public was their listings in Michael Kennedy’s complete catalogue of Vaughan Williams’ works). Since her death The Vaughan Williams Charitable Trust has continued to release selected works, either previously unpublished or earlier versions of works already in the repertoire, to each of the composer’s original music publishers (there were several) or their successors. Such releases include early chamber music to Faber Music and the original (longer) version of A London Symphony to Stainer & Bell.

In 2009 Oxford University Press (OUP) published a small and previously unknown carol by Vaughan Williams (O My Dear Heart), but OUP’s recent issues of unpublished Vaughan Williams titles have been exclusively of orchestral works. The Solent was written in 1902/3 and was planned to be one part of a four-movement orchestral ‘impressions’ of the New Forest. It received a private performance on 19 June 1903 and was then forgotten, although Vaughan Williams made use of one of its themes in at least one later work (his ninth symphony, written shortly before his death). The Serenade in A Minor dates from five years earlier, and was heard at Bournemouth in April 1904 and again in London’s Aeolian Hall in 1908. Like The Solent, it was then forgotten. These two works are being performed on 24 May as part of the English Music Festival, in a ‘Searching for English Music’ concert at Dorchester Abbey, Oxfordshire, with the BBC Concert Orchestra conducted by Martin Yates. These performances will bring two early scores by Vaughan Williams to the ears of modern audiences for the first time, and will allow listeners to judge for themselves just how and where they fit into the already large and popular oeuvre of this celebrated English composer. The score for Serenade was published by OUP in 2012, and that for The Solent will be issued later this year.

Later this summer, we hear Anthony Payne’s re-imagining not of Elgar but of another Vaughan Williams score. At the request of the BBC he has orchestrated the Four Last Songs, written by Vaughan Williams (originally for voice and piano) to poems by Ursula in the last years of his life, and published posthumously by OUP. Payne’s orchestration will be heard at the Royal Albert Hall in a BBC Promenade Concert on 4 September 2013. New versions of works by Vaughan Williams? The composer would most definitely have approved, but that is another story.

Simon Wright is Head of Rights & Contracts, Music at Oxford University Press. Read his previous blog post: “Sinfonia Antartica: ‘Good, great and joyous, beautiful and free’.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Oxford Sheet Music is distributed in the USA by Peters Edition

Image credit: Portrait of Ralph Vaughan Williams courtesy of OUP sheet music department. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post The old shall be made new appeared first on OUPblog.

China: the making of an economic superpower

The Telegraph Hay Festival is taking place from 23 May to 2 June 2013 on the edge of the beautiful Brecon Beacons National Park. We’re delighted to have many Oxford University Press authors participating in the Festival this year. OUPblog will be bringing you a selection of blog posts from these authors so that even if you can’t join us in Hay-on-Wye, you won’t miss out. Don’t forget you can also follow @hayfestival and view the event programme here.

Linda Yueh will be appearing at The Telegraph Hay Festival on Sunday 26 May 2013 at 5.30 p.m. to examine China’s growth and the making of an economic superpower. More information and tickets.

By Linda Yueh

China has successfully utilised inward foreign direct investment (FDI) to “catch up” in growth by using foreign investment to help develop manufacturing and export capacity. The next phase requires technological progress and thus will involve outward FDI, including its firms’ “going global.” The “going out, bringing in” policy means that its “open door” policy has been supplemented by the “going out” of its firms as well as “pulling in” FDI. This is a key part of China’s future growth; that is dependent on the ability to produce globally competitive corporations that will help China move up the value chain and sustain its development and overcome the “middle income country trap”. This refers to how countries slow down after reaching about $14,000 per capita – the level that China is forecast to reach before 2020. Thus, the next phase of growth will be characterised by a shift in its growth paradigm and centre on global integration characterised by outward investment as China takes its place as a burgeoning economic superpower.

It also has macroeconomic benefits in reducing foreign reserve accumulation from its record $3.44 trillion by buying more real assets instead of government bonds to balance its current account surplus. China has worried about the value of its holdings with Western economies struggling in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis and the ongoing euro debt crisis. Thus, China has also launched a policy to internationalize the RMB, increasing the use of the Chinese currency internationally, via offshore centres to allow gradual capital or financial account liberalisation. That ambition to develop the RMB, plus the aim to invest rather than buy government debt, will fundamentally transform China’s impact on the global economy.

These are the key steps toward an inevitable structural shift in the economy – both the external sector and also re-orienting more toward domestic demand. These were highlighted in the major policy document of the 12th Five Year Plan (2011-2015) as well as in the World Bank and China’s State Council Development Research Centre’s “China 2030” report, both of which I served as an advisor on.

Re-balancing growth

Re-balancing growth will add to China’s stability and allow it to become more like the structure of the only economy in the world larger than China’s. America is one of the world’s top three traders, but its economy is largely driven by domestic demand. China, too, can become a large, open economy. China would gain greater stability and a more sustainable basis for its future growth if it continues to be globally integrated, but be less subject to the volatility that plagues small, open economies such as those in Asia.

To orient toward domestic demand means boosting consumption in China, i.e. reducing the savings tendencies of households and firms. Consumption fell from around half of GDP in the 1980s and early 1990s to nearly one-third by the late 2000s. In developed economies, consumption is typically between half to two-thirds of GDP.

For Chinese households, precautionary savings motives are important to address, particularly in rural areas. There has also been an increase in savings by firms (state-owned and non-state-owned) during the 2000s where firm savings have rivalled that of households. The reason is thought to be because China’s distorted financial system is biased toward state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and private firms have trouble obtaining credit—whether from banks or the underdeveloped domestic capital markets.

Going global

China also recognizes that its growth will slow in the coming decades, and it is wary of falling into the “middle income country trap”. It therefore wants to upgrade technologically, have globally competitive firms and sponsor greater innovation, which requires having firms that operate, compete and learn in developed markets. This is a trait shared by those countries that have joined the ranks of rich nations, such as Japan, South Korea and others – and China is keen to do the same.

Plus, China has been aiming for some time to diversify out of U.S. Treasury bonds due to worries about the American fiscal position. But, the euro debt crisis has also raised concerns about the eurozone. Thus, the recent thrust of Chinese policy has been to use foreign exchange reserves to finance investments by Chinese companies overseas instead of acquiring more government debt.

There has been exponential growth of outward FDI since the mid 2000s when the first commercial investment by a Chinese firm was permitted in 2004 with TCL’s purchase of France’s Thomson. By last year, China reported that it had invested a record $117 billion overseas. China is aiming to show that its industrial capacity is not only a function of foreign firms producing its exports, but indicative of a more widespread upgrading of its industry.

China’s changing impact on the world

China can become a large, open economy – developing domestic demand and upgrading industry/promoting globally competitive firms – that recognises its wider impact as it is unlike small, open, export-led economies. China already does and will increasingly do so as it promotes outward investment, the internationalisation of the RMB and the gradual opening of its capital account. With per capita incomes still only at $9,100, there is significant scope for China to continue to grow even though it ranks as the world’s second largest economy. The Chinese government has a 30 year plan that hinges on these components that will undoubtedly transform the world economy in a fundamentally different manner than the past impact via cheap manufactured goods. The new trends will involve the rise of the RMB as a reserve currency, competitive Chinese multinationals and greater opening of the mainland market. Most importantly, successfully re-balancing China will mean a more sustainable growth path for China and perhaps the world economy.

Dr. Linda Yueh is Director of the China Growth Centre and Fellow in Economics, St Edmund Hall, University of Oxford, Adjunct Professor of Economics at the London Business School, and Visiting Professor of Economics at Peking University. She is the Chief Business Correspondent at the BBC and the host of a new weekly business programme on BBC World News. She is the author of several books, including two by Oxford University Press: China’s Growth: The Making of an Economic Superpower and Enterprising China: Business, Economic, and Legal Developments Since 1979. You can follow her on Twitter @lindayueh

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Flag of China. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post China: the making of an economic superpower appeared first on OUPblog.

May 22, 2013

Multifarious devils, part 1: “bogey”

As has often happened in the recent past, this essay is an answer to a letter, but I will not only address the question of our correspondent but also develop the topic and write about Old Nick, his crew, and the goblin. The question was about the origin of the words bogey and boggle. I have dealt with both in my dictionary and in passing probably in the blog, but after more than seven years the archive of “The Oxford Etymologist” has grown to such an extent that even I remember dimly whether certain subjects have been covered in the “gleanings” or in a special essay. So what is the origin of bogey? One should perhaps begin with the word boo!

Nobody will contest the idea that boo is an interjection. However, putting a classificatory label on it does not mean solving its etymology. Most interjections are studied, artificial words, from oops and ouch to jiminy and Gosh, and their origin is often lost. The same can be said about the polite oh, ah, and eh. Only natural shrieks (when we holler with pain) are natural, but they are hard to verbalize. Let us agree for the sake of (the) argument that boo is an imitative word and proceed from there. To put it differently, let us agree that we associate boo with noise. Noisy things deafen people. They swell, burst, explode, and by doing so scare us; they are often huge and inflatable, and their spread is beyond people’s control. The most dangerous step in our search will be the first. Can we assume that various consonants tend to attach themselves to sound complexes like boo or bu and form nouns, adjectives, and verbs of more or less predictable semantics? Once we make such a step, we will be in serious trouble, but there is no choice. If boo is sound imitative, does the same hold for boom? Most language historians think so. And bomb? It matters little that Engl. bomb is a borrowing from French (ultimately from Latin, from Greek). Imitative words are similar all over the world, don’t obey so-called phonetic laws, and are easily borrowed.

Now, if bomb is onomatopoeic, nothing prevents us from drawing pomp, pumpkin, and even pooh-pooh, into this net, and, sure enough, it has been done. Since we have allowed our words to begin with p- and have various vowels, we may try to add consonants other than b ~ mb to b- ~ p-. Along the way, we cannot avoid the adjective big. Its derivation has been the object of involved and largely profitless speculation, with one or two improbable hypotheses thrown in for good measure, but, since we need words designating menacing, noisy objects, big will suit us. Strangely, big is the Dutch for “pig,” and pig (the name of a fat, “big” animal) is another word whose origin has been called unknown.

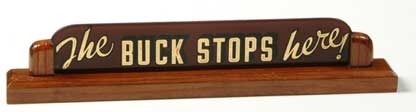

The next object of horror is buck, designating a particularly corpulent beast. The Germanic spectrum of senses in this word is limited: “the male of a horned animal,” (specifically) “the male of the bovine family,” “male deer,” and “billy-goat,” with the root often ending in -kk (a long consonant, or geminate, to use a technical term, emphasizes the word’s affectionate, expressive nature). Irish bocc and Sanskrit bukka “billy-goat,” Armenian buc “lamb,” and Russian byk “buck” (with similar cognates elsewhere in Slavic) are variants of the same word. They may trace to boo “moo,” but pigs do not moo and yet big ~ pig resemble buck, whose most ancient form must have been bukkaz. Nor is bleating (compare Armenian buc) the same as booing ~ mooing, but we remain in more or less the same sphere.

Once we have done with the cattle, we run into Russian buka “bogyman” and wonder what to do with Russian bukashka (stress on the second syllable) “a small insect of any kind,” a word allegedly (but uncertainly) related to another onomatopoeic verb. Lost among bucks, pigs, and their look-alikes, we cannot avoid bug. Its earlier English synonym (or etymon?) was budde, but consonant and vowel variation has long since stopped bothering us: in this game, everything goes. Besides, buds swell and burst, just as we expected. Norwegian bugge means “big sturdy man.” Bug “an object of dread” and bug “insect” (in British English, mainly “beetle”), along with the verb bug (“What’s bugging you?”) and the bug in our computers, are probably different senses of the same word, originally the name of a creature endowed with the ability to swell (hence ready to explode, produce a lot of noise, and fill its surroundings with fright). In its vicinity we discover bugaboo and its earlier variant bugaboy. The latter need not be a “corruption” of bugaboo, because boy, a noun phonetically close to boo, was attested in Middle English with the sense “devil,” and the phrases at a boy and oh, boy may be relics of that sense. The second element of bugbear is bear (an animal name), because people stood in mortal fear of bears and wolves.

Boogie, as in boogie-woogie, is believed to be a West African coinage, and, if it is true that boogie originally meant “prostitute,” we are dealing with a social bugaboo. Speakers all over the world use the sound complex boog- ~ bog- for naming similar objects. Bogey emerged as a member of a large family. Old Bogey is the Devil, a bug, a bugbear. Bogus, initially, as it seems, part of counterfeiters’ slang, is, like most words being discussed here, of unknown etymology. It may well be a relative of bogey. Boggle means “to bedevil,” that is, not only “to confuse” but also “to frighten.” Russian bog (a Common Slavic word) means “god.” It is akin to several Sanskrit and Iranian words for “endowing with gifts” and so forth. In Modern Russian, bogatyi (stress on the second syllable) means “rich.” Long ago attempts were made to connect Slavic bog with English bogey, but they were given up as fanciful. Yet I wonder whether the positive senses (“riches, gifts”) did not arise later. Pagan gods, an invisible multitude, filled worshipers with dread and were propitiated in the hope of warding off the evil they caused. The development of the generic concept (God), characteristic of monotheistic religions, is particularly hard to trace.

Etymology stopped being guesswork when phonetic correspondences were discovered. The exercise offered above smacks of medieval linguistics. Vowels and consonants play leapfrog at will. It is no wonder that good dictionaries call most of such words etymologically obscure. If one can mention boo, boom, bomb, pomp, pig, big, bud, bug, and bogey in one breath, when and where do we stop and for how many more words should we make special dispensation? Are we allowed to incorporate bog “swamp,” puddle, and pudding into the list? They do not burst, but they certainly “spread.” No one can give a definite answer to those questions.

Words are not soldiers marching in single file, but they are not a disorganized crowd either. Neither limitless free trade nor strict planning will do them justice. Boggled by this opportunistic conclusion, we can only say that Old Bogey is a noisy demon, an evil bug and that his name reflects this fact.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: The Buck Stops Here sign from Harry Truman’s White House desk. Image courtesy of the Truman Presidential Library. Public domain.

The post Multifarious devils, part 1: “bogey” appeared first on OUPblog.

The History of the World: Nixon visits Moscow

22 May 1972

The following is a brief extract from The History of the World: Sixth Edition by J.M. Roberts and O.A. Westad.

In October 1971 the UN General Assembly had recognized the People’s Republic as the only legitimate representative of China in the United Nations, and expelled the representative of Taiwan. This was not an outcome the United States had anticipated until the crucial vote was taken. The following February, there took place a visit by Nixon to China that was the first visit ever made by an American president to mainland Asia, and one he described as an attempt to bridge ‘sixteen thousand miles and twenty-two years of hostility.’

Post War Europe – Economic and Military Blocks (c) Helicon Publishing Ltd

When Nixon followed his Chinese trip by becoming also the first American president to visit Moscow (in May 1972), and this was followed by an interim agreement on arms limitation – the first of its kind – it seemed that another important change had come about. The stark, polarized simplicities of the Cold War were blurring, however doubtful the future might be.

Reprinted from THE HISTORY OF THE WORLD: Sixth Edition by J.M. Roberts and O.A. Westad with permission from Oxford University Press, Inc. Copyright © 2013 by O.A. Westad.

J. M. Roberts CBE died in 2003. He was Warden at Merton College, Oxford University, until his retirement and is widely considered one of the leading historians of his era. He is also renowned as the author and presenter of the BBC TV series ‘The Triumph of the West’ (1985). Odd Arne Westad edited the sixth edition of The History of the World. He is Professor of International History at the London School of Economics. He has published fifteen books on modern and contemporary international history, among them ‘The Global Cold War,’ which won the Bancroft Prize.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The History of the World: Nixon visits Moscow appeared first on OUPblog.

Getting to the heart of poetry

Oxford University Press recently partnered with The Poetry Archive to support Poetry by Heart, a new national poetry competition in England which saw thousands of students aged 14 to 18 competing to become national champion for their skill in memorising and reciting poems by heart. OUP provided free content from OED Online, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, and the American National Biography Online to support students participating in the competition. Here, 18 year old winning contestant Kaiti Soultana writes about the experience.

By Kaiti Soultana

What impelled me to participate in Poetry by Heart? Like many of the other contestants, I wanted both to galvanize others and to be inspired myself. It seems that poets strive to enhance the minds of those reading and listening, and I find this so philanthropic. Though a cliché, it is true to say that although I won the competition, I would have won even if I had not gained first place; the experience was invaluable and truly irreplaceable.

What Poetry by Heart offered was an opportunity to deliver a poem aloud and consequently for me to retain it. What I think makes the spoken word superior to reading a poem silently is that delivering a poem aloud allows for both the poet’s and the speaker’s voices to truly be heard. Quite often you find that it is not only the words of the poem but also the sound of it that attracts us to it, even before fully understanding the message it is giving. That is something I experienced when exploring the part of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight that I chose to recite. As competitors, we were provided with an anthology of poems of two categories to choose from and recite: a pre-1914 and a post-1914 list. It was the work of that anonymous 14th century poet that aroused within me such delight, though amusingly I initially understood very little of what I was reading.

It was that yearning to learn, and to explore what would otherwise go unexplored, which I found so inviting about Sir Gawain. I took up the challenge to inspire others through this astonishing, demanding, and somewhat alien ‘old’ English language. The alliterative threads that bound the poem made it easier to immerse both myself and the audience in such an unfamiliar realm, and it was this, I believe, that made my recitation successful.

My choice of post-1914 poetry developed from a somewhat different quality that poetry as a medium triumphs in: the ability to reveal the extraordinary within the ordinary. Elizabeth Bishop seemed to express such perplexed beauty in her poem The Fish, so much so that it established an abnormal yet completely natural and loving bond between myself as a reader and a mere fish.

I began preparing my recitations by acquiring as much basic contextual knowledge about both poem and author, attempting to understand what message each one was trying to convey, yet interpreting it personally and intimately. My progression in understanding each of my poems grew from a minimal surface reading to one where my own interpretation and ideas worked alongside that of the poet’s. I seemed to gain companionship with a person I had never met or talked with. I began to gain an insight into their minds, into the worlds they had constructed. It wasn’t just a poem by rote I had gained, but the appreciation and understanding of a poet’s imagination.

The competition itself seemed far more like a humble gathering of young literary enthusiasts. Through the stages – from school heats to county contests and finally the regional and national finals weekend – the rounds seemed more like a programme of complementary performances. They allowed for initial introductions to mature into lasting friendships – I have experienced the development of such friendships with people across the country thanks to Poetry by Heart.

Though enjoyable, I was unsuccessful in casting away the nerves I am often plagued with. However, it was participating in a competition that I sincerely valued and appreciated, that motivated and inspired me, and allowed me to at least control those nerves.

In addition to viewing others’ regional heats, Poetry by Heart’s organisers scheduled excursions for participants to the London Eye, the British Library and tours of the National Portrait Gallery, none of which I had been privileged to visit before. I was stimulated to explore a small part of London, an opportunity that was exciting, fun, and invaluable.

The weekend itself was nothing shy of extraordinary. It seems unanimous that what we had gained by offering ourselves as orators of the poems was more than just the memory of the poem itself. What I gained was far more remarkable; I discovered the importance of poetry to human beings, and how this importance has spanned generations. It continues to grow as a form of universal expression, and with great thanks to Poetry by Heart I have truly understood its often unacknowledged value.

Kaiti Soultana is 18 and studying A levels at Bilborough College, Nottingham.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: Courtesy of Poetry by Heart; do not reproduce without permission.

The post Getting to the heart of poetry appeared first on OUPblog.

May 21, 2013

The marginalized Alexander Pope

Spring 2013 marks two significant anniversaries for Alexander Pope, perhaps the most representative and alien English poet of the 18th century. Pope is memorialized both for the 325th anniversary of his birth, on 21 May 1688, and for the 300th anniversary of two significant literary acts: one a publication, the other a proposal to publish.

Spring 2013 marks two significant anniversaries for Alexander Pope, perhaps the most representative and alien English poet of the 18th century. Pope is memorialized both for the 325th anniversary of his birth, on 21 May 1688, and for the 300th anniversary of two significant literary acts: one a publication, the other a proposal to publish.

On the 7 March 1713, Pope published one of his most important poems. Windsor Forest was published the same month as the signing of the multi-stage Treaty of Utrecht, with which, in part, the poem deals: “Hail, sacred Peace! hail long-expected days” (Windsor Forest, line 353). The redistribution of territories determined by that treaty created various, continuing friction points between Protestant Britain and its Catholic adversaries: France ceded vast North American territories to Great Britain leaving French Canada surrounded by English lands, while Spain ceded Gibraltar to Britain and acquired the Falkland islands (Islas Malvinas). It was a period of global, territorial conflicts, but passions were inflamed by the Protestant/Catholic schism.

Later that same year, Pope made public, and sought subscriptions for, a proposal for the first major English translation of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey since that of Shakespeare’s contemporary George Chapman (1559–1634). Pope’s Homeric effort became one of the major cultural accomplishments of the period. In a letter of 4 October 1726, Voltaire praised Pope’s fingers, “which have dressed Homer so becomingly in an english coat”.

As a man, Pope himself has at least two claims on our attention, though his anniversary will undoubtedly rank lower in public attention than would that of many other poets of these Isles. A Google search on English poets by forename and surname lets us plot a rough graph of Internet popularity:

However, there are other digital measures of a poet’s popularity. Pope’s epigrammatic style and his rhyming couplets, which suffered critically at the hands of the Romantics and later generations, now proves to be remarkably popular among the choruses of Twitter, where there are a number of “Pope” persona:

— and endless Pope Tweets, quoting (or misquoting) lines from his verse. Pope’s epigrammatic couplets were crafted to place a succinct thought within a limited number of words:

One of the things that continues to intrigue about Pope, is his extraordinary confidence and ability to focus on his vision of what he should do and be in life. Two years before the date marked by this anniversary, Pope published one of his two great “epigrammatic essays” — An Essay on Criticism (first published anonymously, 15 May 1711). Pope was only 23, and the work does more than mark him out as a singular and singularly memorable essayist on the human condition. It presents us with the noteworthy instance of a young man, still at the beginning of his literary career, publicly admonishing and correcting the established critical community. It reminds me of the equally confident, if often less accessible, manifestoes of the Modernist movement.

For Pope was no social or cultural insider, but what might be thought of as a “corporeal and incorporeal outsider.” Pope was twice marginalized in his world. Marginalized once for his beliefs — as a Catholic, then barred from teaching, attending university, voting, or holding public office on pain of imprisonment. The anti-Catholic sentiment was aggravated by the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714), which led to a statute preventing Catholics from living within 10 miles (16 km) of either London or Westminster.

These constraints would have pinched especially hard on the ambitions of Pope’s essentially middle class family. They were prosperous enough, however, to be able to escape to the country, moving to a small estate in Binfield (or Bynfield), Berkshire, when Alexander was twelve. Binfield was only a dozen kilometres west of Great Windsor Park, though remains of the ancient royal hunting grounds of Windsor Forest undoubtedly “crown’d with tufted trees” (Windsor Forest, line 27) various plots between the two. On the verges of these forests, you could pretend to be anyone, and one’s beliefs could be recast in the poetic imagery of patriotism and Classical analogy we find in Windsor Forest.

Estates at Windsor, Berkshire — British Library, “The unveiling of Britain”. © The British Library Board Royal Ms. 18.D.III, f.32

Pope could never escape his second marginalization, however, for he literally carried it with him on his back. From the age of twelve, exactly at the time of the family move from London, Pope suffered from a form of tuberculosis that affected the bone, deforming his body, stunting his growth. Pope grew to a height of only 4 feet 6 inches (1.37 m), and was left with a severe hunchback.

The disease received its formal medical description in Pope’s lifetime, though too late to help the poet. A decade before Pope’s death in 1744, a Liverpool surgeon, H. Park, wrote an epistolary volume in which characteristics and (painful) treatments of the disease were described: An Account of a new method of treating diseases of the joints of the knee and elbow, in a letter to Mr. Percival Pott. (London: J. Johnson, 1733). The recipient of the “letter”, the remarkable English surgeon Sir Percivall Pott (1714–1788) was one of the founders of orthopedy, and the first scientist to demonstrate that cancer may be caused by an environmental carcinogen. He published a volume on Some few general remarks on fractures and dislocations (London: Hawes, Clarke and Collins, 1768), providing the first clinical description of extrapulmonary tuberculosis (tuberculous spondylitis), the disease with which Pope suffered, subsequently known as Pott’s disease.

The disease received its formal medical description in Pope’s lifetime, though too late to help the poet. A decade before Pope’s death in 1744, a Liverpool surgeon, H. Park, wrote an epistolary volume in which characteristics and (painful) treatments of the disease were described: An Account of a new method of treating diseases of the joints of the knee and elbow, in a letter to Mr. Percival Pott. (London: J. Johnson, 1733). The recipient of the “letter”, the remarkable English surgeon Sir Percivall Pott (1714–1788) was one of the founders of orthopedy, and the first scientist to demonstrate that cancer may be caused by an environmental carcinogen. He published a volume on Some few general remarks on fractures and dislocations (London: Hawes, Clarke and Collins, 1768), providing the first clinical description of extrapulmonary tuberculosis (tuberculous spondylitis), the disease with which Pope suffered, subsequently known as Pott’s disease.

I recommend a re-reading of Windsor Forest with some sense of the twice-excluded author in mind. All good poems can be read in many ways, but one of the things this re-reading proposes is the struggle of an outsider to create a re-vision of the world that contains and excludes him.

Dr. Robert V. McNamee is the Director of the Electronic Enlightenment Project, Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

Electronic Enlightenment is a scholarly research project of the Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, and is available exclusively from Oxford University Press. It is the most wide-ranging online collection of edited correspondence of the early modern period, linking people across Europe, the Americas, and Asia from the early 17th to the mid-19th century — reconstructing one of the world’s great historical “conversations”.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Alexander Pope portrait. NYPL Digital Gallery. (2) Google searches for poets. Copyright Dr. Robert V. McNamee. Used with permission. (3) Screengrab from Twitter by Dr. Robert V. McNamee. (4) Screengrab from Twitter by Dr. Robert V. McNamee. (5) Estates at Windsor, Berkshire — British Library, “The unveiling of Britain.” © The British Library Board Royal Ms. 18.D.III, f.32. Used with permission. (6) From a mid-19th century text book. Out of copyright.

The post The marginalized Alexander Pope appeared first on OUPblog.

The dire offences of Alexander Pope

By Pat Rogers

There’s never been a shortage of readers to love and admire Alexander Pope. But if you think you don’t, or wouldn’t, like his poetry, you’re in good company there too. Ever since his own day, detractors have stuck their oar in, some blasting the work and some determined to write off the writer. A noted poet and anthologist, James Reeves, wrote an entire book in 1976 to assail Pope’s achievement and influence. But it has never succeeded; Pope, a combative as well as a marvellously skilled author, keeps coming back for more. He produced more first-rate poems than anyone else in the eighteenth century, as we might guess from his fame across Europe and his huge appeal in America before and after the Revolution.

In truth, much of the hostility he faced in his lifetime had to with fear of his scathing wit. “Yes, I am proud; I must be proud to see / Men not afraid of God, afraid of me,” he wrote late in his career. The stark clarity with which he states the idea must have made quite a few contemporaries shuffle another step backwards.

It doesn’t take much more to enjoy Pope than a reasonably good ear and a feeling for language. To read his works carefully will give anyone a grounding in how lines sing, how to make words bend and let meanings fold into each other. It will spare you a whole module on the creative writing course. Sound and sense are delicately adjusted, rhyme and rhythm subtly integrated, wit and wisdom dispersed with the utmost economy.

The most single brilliant item is The Rape of the Lock, completed in 1714 when he was only twenty-five. On the surface this relates how a brutal upper-class twit attacks an airhead socialite. You can find the tale amusingly retold by Sophie Gee in her novel The Scandal of the Season (2007). Actually the ravishing of a beauty in this ravishingly beautiful poem amounts to cutting off just one of her curls, but the text constantly insists that a more serious violation has gone on.

Queen Anne, whose court is satirized in Pope’s ‘The Rape of the Lock’.

What Pope does is imbue this episode with layers of submerged meaning. Though it is easy to follow the narrative, the events are just the excuse for a dazzling exercise in channelling literary sources, which makes the allusive structure of Finnegans Wake seem almost a doddle. The Rape supplies a ridiculously miniaturized version of classical epics like The Iliad , with heroic battles fought at a card-table; an appropriation of Paradise Lost ; a reinvention of the fairy lore in A Midsummer Night’s Dream ; a subversion of fanciful occult systems such as that of the Rosicrucians; and a satire on court life under Queen Anne, as well as a dramatization of the limited marriage market for the gentry among Pope’s own Catholic community. It plays with arcane connections associated with the seasons and the times of day; makes fun of fashionable pseudo-medical ideas linking hysteria to women’s biology; and cruelly exposes the consumerism of a materially obsessed society, while rendering the texture and glitter of its luxury objects in enticing detail.The main trick is to build up this critique from a phrase, a verse, a couplet, a paragraph, and a canto, all serving as fractals which contain within themselves the central paradox announced in the first two lines: “What dire offence from am’rous causes springs, / What mighty contests rise from trivial things.” The contrasting terms here form what we call antithesis, borrowing an expression originally used in classical rhetoric. Pope extends antithesis to his grammar, his versification, his metaphors, and his narrative.

A single bit of wordplay encapsulates this process. It comes in the famous pun that describes the queen’s routine at Hampton Court, where she “sometimes counsel take[s] — and sometimes tea.” In the previous couplet, British statesmen plot the fall of “foreign tyrants,” but also of “nymphs at home.” Everything from the tiniest unit up to the overall shape of the work is designed to enforce the same balanced oppositions between the grand and the slight. And none of it ever ceases to be funny.

Pope’s supreme technique meant he could excel in almost every genre available to him. His powerful satire The Dunciad makes mincemeat of the vapid scribblers in Grub Street. You don’t have to know who they were to get most of the jokes. An Epistle to a Lady might have been written as a set text for modern feminists, so provocatively does it raise issues on the gender front for debate and appraisal. An Epistle to Bathurst provides a telling picture of the repercussions of the South Sea Bubble in 1720. While Pope doesn’t forget the investors who lost everything, he bothers less about perpetrators in the financial industry than about the hypocrisy of a corrupt crew in government and parliament whose regulatory touch was so light as to be invisible.

For a long time An Essay on Man was about the most cited treatise worldwide on morals and metaphysics, while An Essay on Criticism wittily expounds – well, criticism. Pope’s version of Homer remains among the few translations of a masterpiece to constitute a major work in its own right when converted to the host language. He also wrote superb prose, for example in his good humoured but damning retorts to the scandalous publisher Edmund Curll.

In case you thought Pope sounds a bit remote, you might recall when you last heard someone use phrases like these: “To err is human, to forgive divine” ; “Fools rush in where angels fear to tread” ; “Hope springs eternal in the human breast” ; “Who breaks a butterfly upon a wheel?” ; “A little learning is a dangerous thing” ; “Damn with faint praise.” We owe them all to one man. These and many more have entered the stock of colloquial language, an idiom Pope learnt to utilize in sparkling poems that explore the full range of the human comedy.

Pat Rogers, Distinguished University Professor, University of South Florida, editor of The Major Works of Alexander Pope for the Oxford World’s Classics, and author of works on Swift, Defoe, Fielding, Johnson, Boswell, and Austen among others.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Portrait of Queen Anne by John Smith (1652–1742) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post The dire offences of Alexander Pope appeared first on OUPblog.

One hundred years of The Rite of Spring

The centenary of the 29 May 1913 premiere of Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring is being celebrated by numerous orchestras and ballet companies this year, which is always worth mentioning when that first performance incited a riot. The ballet (also performed as an orchestra piece) depicts a collection of pagan spring rituals involving fortune telling, holy processions, and culminating in l’élue (the elected one) dancing herself to death. It was not the subject matter but the music and choreography that upset that first audience 100 years ago. Indeed, according to this interview with Stravinsky, even during the compositional process the composer was upsetting people, namely his collaborators:

Click here to view the embedded video.

It’s clear from the video that Stravinsky knew how uncommon-sounding and challenging the work would be for his listeners. He also seemed delightfully aware of the piece’s significance for the story of Western art music. The eight-note chord is “new,” and the accents are “even more new.” New how? Taking into consideration Stravinsky’s education (the musical part, not the law school part) and the cultural milieu in which he placed himself, it’s safe to say he was thinking in terms of the circa 250 year old Western European tonal tradition when he used the word “new.” The eight note chord was new because it eschewed the traditionally three or four note construction of tonal chords.

The chord that Stravinsky plays in the video is notated above (the chord is the left-most one in the example). By taking two traditionally constructed chords, F-flat major and E-flat seven, and stacking them on top of each other, he has created a polychord that has a much more complex sound than either of the two chords as heard separately.

The accents were “even more new” because they disrupted the metrical norms of the tonal style (in which the strongest beat happens at the beginning of the measure) by rendering the beat uneven.

Traditionally, accents denote the beginning of a measure that contains a recurring number of beats; it’s part of how we mentally divide up time when we play or listen to music. As you can see in the example above, Stravinsky disrupts that regularity by essentially restarting the beat-division at unusual points in the measure (I’ve tried to demonstrate this by numbering the eighth notes).

What’s interesting is that Stravinsky’s polychords and persistent syncopating of the beat weren’t actually the newest “new” sounds around at the time of Rite’s premiere. A group of Austrians were already composing music that disregarded tonality and meter altogether. Nevertheless, Stravinsky’s music deviated sufficiently from tonal norms for it to sound somewhat shocking to his first listeners.

Today The Rite of Spring still sounds new, even to someone like me who spends so much time listening to recently composed, avant garde music. If you haven’t heard the piece, I highly recommend doing so (perhaps this recording from jazz trio The Bad Plus will spark your interest); better yet, see it live if you can. And no need to worry, it’s been nearly a century since it caused a riot.

Meghann Wilhoite is an Assistant Editor at Grove Music/Oxford Music Online, music blogger, and organist. Follow her on Twitter at @megwilhoite. Read her previous blog posts on Sibelius, the pipe organ, John Zorn, West Side Story, and other subjects.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post One hundred years of The Rite of Spring appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers