Oxford University Press's Blog, page 945

May 14, 2013

DSM-5 will be the last

In assessing DSM-5, the fog of battle has covered the field. To go by media coverage, everything is wrong with the new DSM, from the way it classifies children with autism to its unremitting expansion of psychiatry into the reach of “normal.” What aspects should we really be concerned about?

Think of a bowl of spaghetti. There are the central swirls of spaghetti in the middle of the bowl and the strands of spaghetti hanging over the side. Most of the controversy has been about the strands dangling down, how we classify marginal disorders of various kinds. It’s not that people with these disorders, such as the hyperactive and the autistic, aren’t important, but they aren’t the meat and drink of psychiatry.

The problem that the DSM-5 doesn’t address lies at the center of the bowl. It concerns psychiatry’s main diagnoses, not its marginal outliers, and those main diagnoses are major depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. The new edition hasn’t really touched any of them; the way they were defined and classified, and the way they continue to be recognized, ignores major differences within each diagnosis.

Keep in mind how easy it has been to get funny-sounding new diagnoses into psychiatry. Some, such as bipolar disorder, come in as a result of fad. A German psychiatrist named Karl Leonhard created bipolar disorder in 1957 when he said that there are two kinds of depression, unipolar depression (no mania) and the depression that alternates with mania (later called, in DSM-3 in 1980, bipolar disorder). Leonhard’s European and American disciples — a small but influential band — saw to it that separating depressions by “polarity” was widely accepted. Yet there was no new science here; it was the whim of one man.

Some of the diagnoses at the heart of the bowl came in by fiat. Robert Spitzer, the architect of DSM-3, simply decided in 1980 to collapse psychiatry’s various depressions — which had been as diverse as chalk and cheese — into a single disorder: major depression. There were howls of protest, but, hey, the thing was already in print. Set in stone. Even though it makes no scientific sense to classify depressions on the basis of polarity, that’s what we have ended up doing.

Serious depression — or melancholia — remains serious depression whether an episode of mania complicates it or not. Sooner or later, many patients with serious depression will experience some manic features, without that changing their basic diagnosis.

Related to schizophrenia, psychosis (loss of contact with reality via hallucinations or delusions) certainly exists. And there are many forms of it: some come out of the blue, others begin insidiously and seem to grow out of the patient’s personality; some involve loss of brain tissue, others don’t; some end very badly, others stabilize at the ability to lead a more or less normal life: you may not become a neurosurgeon, but you get married, have kids, keep a job, the whole ball of wax. These are different diseases.

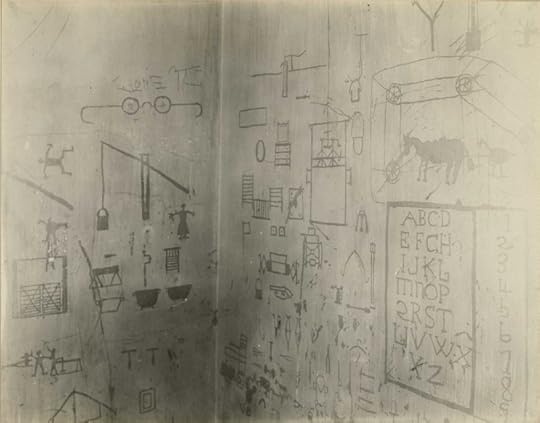

St. Elizabeth’s Hospital. Wall of room in Ward Retreat 1. Reproductions made by a patient with dementia praecox…Pictures symbolize events in patient’s past life and represent a mild state of mental regression. Undated, but likely early 20th century. Washington, DC. Selected by Kathleen.

Yet we now give all these forms of psychosis a single diagnosis: schizophrenia. That’s without a plural “s.” If you’ve got chronic psychosis you’ll be called schizophrenic, even though you may not have any symptoms in common with others who have that diagnosis. You may have quite different family (genetic) backgrounds; you may not have a common response to treatment; and you may not have a common course and outcome. Those are all the ways we delineate separate diseases and “schizophrenia” demonstrates none of those hallmarks. It’s an artifact that Emil Kraepelin, the great German disease classifier, inserted into the literature in the 1890s, calling it dementia praecox. So powerful was his concept — that all the different “subtypes” of schizophrenia went remorselessly downhill — that the term has survived the relentless scientific plucking that all other diagnoses in medicine continually experience.

But conceptual power is not the same thing as verification. There is no marker telling us that everybody with “schizophrenia” has the same disease. (There are, by the way, such markers for some other major diseases; I don’t have space to go into it here, but google “dexamethasone suppression test”.)

So, are there problems with DSM-5? Yes, but they aren’t the problems most critics pick at. Criticisms of DSM-5 seem to be rising in a crescendo, as though a gaggle of high-school teachers were called to assess the work of a very naughty schoolboy. The drafters of the current edition were mightily concerned with maintaining stability; they didn’t want to hack great changes into previous editions. So there is not a chance in the world they would have looked critically at these central problems.

But out there in the real world, there are growing numbers of nosological rebels, or skeptics about the DSM version of disease classification. They have mainly stayed off the airwaves up to now. But you can feel the dubiety rising. There probably will not be a DSM-6.

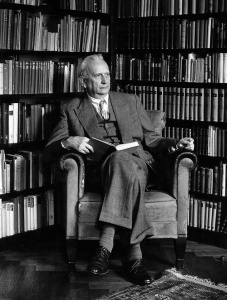

Edward Shorter is Jason A. Hannah Professor in the History of Medicine and Professor of Psychiatry in the Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto. He is an internationally-recognized historian of psychiatry and the author of numerous books, including How Everyone Became Depressed: The Rise and Fall of the Nervous Breakdown, A Historical Dictionary of Psychiatry and Before Prozac: The Troubled History of Mood Disorders in Psychiatry. Read his previous blog posts.

The OUPblog is running a series of articles on the DSM-5 in anticipation of its launch on 18 May 2013. Stay tuned for views from Daniel and Jason Freeman, Donald W. Black, Michael A. Taylor, and Joel Paris.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: By Otis Historical Archives National Museum of Health and Medicine (originally posted to Flickr as Reeve37258). Creative commons license via Wikimedia Commons.

The post DSM-5 will be the last appeared first on OUPblog.

10 moments I love in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby that aren’t in Baz Luhrmann’s film

The build-up to the release of Baz Luhrmann’s frenetic, chromatic interpretation of The Great Gatsby was a wild ride for several of us who live and breathe F. Scott Fitzgerald daily. One minute you’re grading end-of-the semester papers, fighting the losing battle against the extinction of the apostrophe, the next you’re fielding phone calls from NPR or the Associated Press. The experience has been a whirlwind introduction to media relations. I’ve learned, for example, never to declare, “I’m a homer!” when asked my feelings about Fitzgerald over a static-crackling phone line. Mishearing will confuse even the best of reporters.

I’ll say unabashedly that the movie delighted me, as it did many scholars I admire, including such leading Fitzgerald folks as Jackson R. Bryer, James L. W. West III, and Anne Margaret Daniel, as well as my writer pal Therese Anne Fowler, author of the current bestseller Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald. Frankly, any flick that can make Rex Reed’s pacemaker misfire is aces by me. And while I appreciate the objections of The New Yorker and Salon, I honestly think a razzle-dazzle, Adderall-induced Gatsby is what we need at this moment in time—or maybe what I need after so many years now of struggling to persuade students and other resisting readers that Fitzgerald’s lapidary prose isn’t “boring.” For whatever credibility it might cost me, I’m genuinely less interested in what David Denby or Peter Travers think than in watching general audiences dress up as flappers, slip on 3D glasses, and “fangirl” on Tumblr and Facebook. After all, I’ve been “fanboying” since long before I ever presumed to understand the novel.

Elizabeth Debicki as Jordan Baker and Tobey Maguire as Nick Carraway in The Great Gatsby.

That said, I was struck that, for all the familiar lines and symbols incorporated into Luhrmann and Craig Pearce’s screenplay, how many of my personal moments didn’t end up on the screen. After returning from a late-night sneak preview, I sat out by my pool (which, unlike Gatsby’s, has no monogram at the bottom) and reread the book for the zillionth time. If nothing else, the resulting list shows how inexhaustibly intricate The Great Gatsby is.

10. The Dedication. By 1925, Fitzgerald had already dedicated his first short-story collection, Flappers and Philosophers (1920), to his wife/muse, Zelda Sayre. Rather than simply repeat himself he crafted an elegantly metrical acknowledgment of her inspiration that has since become a poignant proclamation of how all roads in life led back to her: “Once Again to Zelda.” Gertrude Stein famously complimented the melody of the phrase, telling Fitzgerald, “[I]t shows that you have a background of beauty and tenderness and that is a comfort.” It’s since become one of the most quoted dedications in literature, providing Marlene Wagman-Geller a wonderful title for her 2008 study of “The Stories Behind Literature’s Most Intriguing Dedications.” I even borrowed the line for a recent reminiscence in The Southern Review on reading Nancy Milford’s biography Zelda in college.

9. The “frosted wedding cake of the ceiling.” When we first see Carey Mulligan as Daisy it’s amid the whip-cracking flutter of curtains at the Buchanans’ East Egg estate. These “pale flags” nearly suffocate Nick Carraway and viewers alike for a few seconds, giving us a sense of what it’s like to be swathed suddenly in opulence. Yet I’ve always been struck more by Fitzgerald’s clever description of the trim and plaster in this “rosy-colored room” as a decorated cake, a metaphor that glides by as smoothly and effortlessly as a spatula stroke of icing. It’s indicative of how finely detailed and sculpted even passing details are. Weirdly enough, Ernest Hemingway would rip off this line in his least graceful novel, To Have and Have Not (1937).

8. Myrtle Wilson’s change, in a single chapter, from crêpe-de-chine to muslin to chiffon. In a book in which stacks of custom-made shirts can bring a woman to tears, every mention of fabric is a significant index of character texture. In Chapter II, Tom Buchanan’s mistress changes clothes three times in rapid succession as Fitzgerald dramatizes her hopelessly vulgar pretensions to style. From what I remember, Isla Fisher only sports two different outfits in her initial sequence with the adulterous Tom Buchanan, but the clothes are emphasized less than her Cupid’s bow lips and boop-boop-de-doop delivery (a slightly anachronistic nod to Betty Boop, who wasn’t born until 1930).

Isla Fisher as Myrtle Wilson, Joel Edgerton as Tom Buchanan, Adelaide Clemens as Catherine, Tobey Maguire as Nick Carraway and Kate Mulvany as Mrs. McKee in The Great Gatsby.

7. Mr. McKee’s underwear. I burst out laughing when Eden Falk came on-screen with the silliest mustache this side of Matt Damon in True Grit. But the parvenu photographer Chester McKee is barely more than an extra in the movie and his most famous scene in the book is nowhere to be found. At the end of Chapter II, after an inebriated ellipsis, Nick discovers himself next to a bed where McKee is described as “sitting up between the sheets, clad in his underwear, with a great portfolio in his hands.” And while “great portfolio” is not a euphemism, the sudden appearance of underoos has launched a thousand seminar and book-club debates about Nick’s sexual leanings.

6. That tear. The first Gatsby party Nick attends is a stylistic tour-de-force of style and technique, with Fitzgerald employing synesthesia and tense shifts to dramatize the sensory dissociation of a wild time. My absolute favorite passage in the “blue gardens” interlude concerns the drunken chorus girl who sings as the revelry gives way to sleepy exhaustion. The singer brings herself to tears, causing her mascara run in rivulets. “A humorous suggestion was made that she sing the notes on her face,” Nick reports. Going into the movie, I was sure that staves and staffs would float off the 3D screen at me and that I would bathe in that tear. Alas.…

5. Gatsby’s guest list. Whole academic careers have been spent chasing down potential Long Island analogues for the social register Nick recites of “those who accepted Gatsby’s hospitality and paid him the subtle tribute of knowing nothing whatever about him.” Luhrmann does give us a Clarence Endive, but I missed Dr. Webster Civet, Willie Voltaire, the Smirkes, the Scullys, and Edgar Beaver, for whom I’ve always felt a pang of empathy: “[His] hair, they say, turned cotton-white one winter afternoon for no reason at all.”

4. The bad driver motif/Myrtle’s “left breast … swinging loose like a flap.” Cars abound in the movie; the driving-into-Manhattan scenes are so fast and furious I kept expecting Vin Diesel to squeal into the frame. But while Luhrmann includes the drunken fender bender at the end of Gatsby’s first party, we don’t get the motif of bad driving as a symbol for moral irresponsibility. This is largely because in the book it’s staged between Nick and Jordan Baker, whose romance is excised from the movie. (As Jordan says, “It takes two to make an accident,” so as long as she sticks around careful people her own carelessness isn’t dangerous.)

Tobey Maguire as Nick Carraway and Leonardo DiCaprio as Jay Gatsby in The Great Gatsby.

Myrtle Wilson’s hit-and-run demise, meanwhile, has always posed a potential tonal turn into Pure Corn. Neither Shelly Winters in 1949 nor Karen Black in 1974 pulled it off. (Winters mainly because of a risible special effect). While in recent years YouTube has hosted a bizarre string of dangerous reenactment videos—made, one assumes as high-school English class projects—no director is likely to visualize the most gruesome image in Gatsby. Myrtle’s nearly severed breast, which dangles like the amputated car wheel in the fender bender scene. The disfigurement is indicative of the Jazz Age’s morbid fascination with the damage automobiles and new machine technologies in general could inflict on a human body.

3. Wolfsheim (or Wolfshiem, depending on your preference) skipping Gatsby’s funeral. Among the most inventive of Luhrmann’s decisions is his casting of Bollywood legend Amitabh Bachchan as the man who fixed the 1919 World Series, a gangster based on Arnold Rothstein (newly rediscovered thanks to Boardwalk Empire). The casting is a clever way to sidestep the charges of anti-Semitism that dog the character. But the new Gatsby leaves out the gangster’s weaselly explanation for missing his protégé/front’s funeral (“When a man gets killed I never like to get mixed up in it”). The movie also avoids one of the strangest literary coincidences ever by not showing the name of Wolfsheim’s business, “The Swastika Holding Company.” Fitzgerald apparently chose this ancient symbol without knowing Adolf Hitler had adopted it for the Nazi Party in 1920.

2. The unnamed obscenity. In the final two pages, as Fitzgerald builds up to his “boats against the current” climax, he shows Nick erasing a dirty word scrawled by a trespasser on Gatsby’s immaculate white steps. Had Hemingway written Gatsby we’d have known exactly what that word was. At the very least, we’d have had the f—ks and c—s—rs he was forced to put in their place. (And Scribner’s wouldn’t even let him get away with c—s—r.) In his worst alcoholic stupors Fitzgerald reportedly rained down F- and C-bombs like artillery shells. Part of his charm, however, is that in his writing he was averse even to “violent innuendo,” much less the “obstetrical conversation” of the meretricious young men at Gatsby’s parties. Erasing the word is Nick’s way of keeping even the detritus of Gatsby’s dream in the polished state of his naiveté.

1. Taking Ravenously, Taking Unscrupulously. In the novel, Fitzgerald breaks up the backstory of Daisy Fay and Jay Gatsby’s 1917 romance into at least three separate flashbacks. The middle one concerns the apotheosizing kiss by which the penniless soldier “wed[s] his unutterable visions to her perishable breath”—a long, intricate passage full of stars and flowers that I’ve seen grown men weep over when read aloud. Later, however, we discover a description of Gatsby first “taking” Daisy out of less noble intentions (“He took what he could get, ravenously and unscrupulously—eventually he took Daisy one still October night, took her because he had no real right to touch her hand”), implying the intriguing possibility that the transformative kiss occurs after their first sexual encounter.

“I wish we could just run away…” – Daisy Buchanan (Carey Mulligan)

The chronology is vague, but the ambiguity reinforces a critical truism: The Great Gatsby isn’t a love story—it’s the story of American self-making. Yet Luhrmann depicts Gatsby as such a romantic naïf in his flashback scenes that true love seems his compelling motivation. Instead, for Fitzgerald, the romance merely validates his hero’s “Platonic conception of himself,” with Daisy a means to an end.

Luhrmann’s insistence that Gatsby is a “great, tragic love story”—a melodrama on the order of Gone With the Wind—is partly why he’s taking such a critical drubbing. But the paradoxes of Gatsby’s “colossal” delusion are probably too complex for a splashy movie, and I found the love story surprisingly affecting, especially the added moment when Daisy attempts to telephone Gatsby just as Wilson arrives to avenge Myrtle’s death. The scene made me empathize with Daisy emotionally rather than intellectualizing her predicament as the book leaves me to do. Maybe that’s the greatest benefit of pushing the romance angle: if a reinterpretation spares me from having to explain one more time why Jay Gatsby would fall for a ditzy “bitch goddess,” I’m down.

In the end, I’m glad we have a version that is controversial and divisive as opposed to the suffocating reverence of the 1974 Robert Redford/Mia Farrow snoozefest, which makes the Jazz Age seems about as fun and dangerous as a dinner with one’s parents. Perhaps I have low expectations for literature and reading at this point, but any version that stops audiences from using “dull” and The Great Gatsby in the same sentence is performing a public service for me. On my way out of the sneak preview I overheard an excited teenage girl declare, “I didn’t cry this much at the end of Titanic.”

Mission accomplished, Luhrmann. Mission accomplished.

Kirk Curnutt is professor and chair of English at Troy University’s Montgomery, Alabama, campus, where Scott Fitzgerald met Zelda Sayre in 1918. His publications include A Historical Guide to F. Scott Fitzgerald (2004), the novels Breathing Out the Ghost (2008) and Dixie Noir (2009), and Brian Wilson (2012). He is currently at work on a reader’s guide to Ernest Hemingway’s To Have and Have Not.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: All images from thegreatgatsby.warnerbros.com. © 2013 Warner Bros. Ent. Used for the purposes of illustration.

The post 10 moments I love in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby that aren’t in Baz Luhrmann’s film appeared first on OUPblog.

The History of the World: Israel becomes a state

14 May 1948

The following is a brief extract from The History of the World: Sixth Edition by J.M. Roberts and O.A. Westad by J.M. Roberts and O.A. Westad.

From the beginning of the Nazi persecution the numbers of Jews who wished to settle in Palestine rose. As the extermination policies began to unroll in the war years, they made nonsense of British attempts to restrict immigration, which was the side of British policy unacceptable to the Jews; the other side – the partitioning of Palestine – was rejected by the Arabs. The issue was dramatized as soon as the war was over by a World Zionist Congress demand that a million Jews should be admitted to Palestine at once. Other new factors now began to operate. The British in 1945 had looked benevolently on the formation of an ‘Arab League’ of Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, the Yemen and Jordan. There had always been in British policy a strand of illusion – that pan-Arabism might prove the way in which the Middle East could be persuaded to settle down after post-Ottoman confusion, and that the co-ordination of the policies of Arab states would open the way to the solution of its problems. In fact the Arab League was soon preoccupied with Palestine to the virtual exclusion of anything else.

Proposed UN partition of Palestine 1947 (c) Helicon Publishing Ltd

The other novelty was the Cold War. In the immediate post-war era, Stalin took the view that Britain and the United States would rival each other for world dominance, and that the Soviets would be served by stirring the pot. Verbal attacks on British positions and influence therefore followed, and in the Middle East this, of course, coincided with traditional interests … The Americans struggled with making out their position. There was major public support in the United States for Zionist views, fueled by the terrible revelations that were coming out of the Nazis’ death-camps.

Thus beset, the British sought to disentangle themselves from the Holy Land. From 1945 they faced both Jewish and Arab terrorism and guerrilla warfare in Palestine. Unhappy Arab, Jewish and British policemen struggled to hold the ring while the British government still strove to find a way acceptable to both sides of bringing the mandate to an end. American help was sought, but to no avail; Truman wanted a pro-Zionist solution. In the end the British took the matter to the United Nations. It recommended partition, but this was still a non-starter for the Arabs. Fighting between the two communities grew fiercer and the British decided to withdraw without more ado.

On the day that they did so, 14 May 1948, the state of Israel was proclaimed. It was immediately recognized by the United States (sixteen minutes after the foundation act) and the USSR; they were to agree about little else in the Middle East for the next quarter of a century.

Reprinted from The History of the World: Sixth Edition by J.M. Roberts and O.A. Westad with permission from Oxford University Press, Inc. Copyright © 2013 by O.A. Westad.

J. M. Roberts CBE died in 2003. He was Warden at Merton College, Oxford University, until his retirement and is widely considered one of the leading historians of his era. He is also renowned as the author and presenter of the BBC TV series ‘The Triumph of the West’ (1985). Odd Arne Westad edited the sixth edition of The History of the World. He is Professor of International History at the London School of Economics. He has published fifteen books on modern and contemporary international history, among them ‘The Global Cold War,’ which won the Bancroft Prize.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The History of the World: Israel becomes a state appeared first on OUPblog.

Baseball scoring

What is it about the sounds of baseball that make them musical, and so easily romanticized? In Ken Burns’ documentary Baseball, George Plimpton says that “Baseball has these absolutely unique sounds. The sounds of spring and summer….The sound of the ball against the bat is absolutely extraordinary. I don’t know any American male that doesn’t hear that in the springtime and get called back to some moment in the past.” These sounds are especially vivid in a game that’s often so quiet.

It’s been made the subject of numerous songs, many of which are collected and fully digitized in the Library of Congress Performing Arts Encyclopedia. Each song is freely available to the public to peruse and parody, including one of the most iconic American songs ever written, “Take me out to the ballgame,” written by Albert Von Tilzer, with lyrics by Jack Norworth. (I’ve been wondering lately if all of Norworth’s lyrics make him sound like a freeloader. He doesn’t pay for the game; he doesn’t pay for the concessions. Maybe the fact that he’d never been out to a ballgame when he wrote the song can be explained by the fact that no one wanted to take him.)

Baseball even gave us the first documented use of the word “jazz.” According to the OED, in 1912 a professional pitcher describing his curve ball was quoted in the Los Angeles Times as saying, “I call it the Jazz ball because it wobbles and you simply can’t do anything with it.”

Despite its connections with the musical world, I have to admit now to a long-standing personal indifference towards the sport. My first-hand experience is limited to a third grade T-ball championship and some horrifying moments in co-ed little league. Baseball was never on TV at home when I grew up, and I’d become immediately bored if I even glanced at a game.

I’ve slowly come around to it (thanks in part to my boyfriend, who wrote the article on baseball songs linked above) to the point where I was comforting myself the day after the Boston Marathon bombing by watching the New York Yankees’ home game against the Arizona Diamondbacks on TV. As Plimpton said, the sounds of the game do bring me back to old memories of summer days (though I’m actually an American female, I think it still counts), and watching the game was having a calming effect on me.

After two and a half innings, the commentators told the audience at home that the song “Sweet Caroline” was going to be played in the stadium, and that they’d broadcast it for those watching at home.

I was moved: “Sweet Caroline” is a Boston song. I know next to nothing about baseball culture, but I learned that much from my two years living in Massachusetts. It’s been played at Red Sox games for years, despite the lyrics having no obvious connections to either sports or Boston.

A 2005 story in the Boston Globe traced the origins of the song’s use there to Amy Tobey, who was in charge of picking the music that would play at Fenway Park from 1998–2004. She’d heard the song at other sporting events and decided to play it in Boston. It was very well-received. The song has been played in the eighth inning of every home game there since 2002; that’s more than 800 eighth-inning sing-alongs over the last decade.

Experience has taught me that, prior to the game on the 16th of April, singing “Sweet Caroline” in Yankee Stadium would probably earn you a few dirty looks, which must be difficult for all those Yankees fans who also happen to be Neil Diamond enthusiasts. So, taking advantage both of an opportunity to show that they were thinking of Boston’s residents and of the only chance they might ever have to yell “So good! So good!” in the stands at Yankee Stadium, the crowd looked like this.

Click here to view the embedded video.

I found the gesture incredibly touching. When I described it to other people the next day, I remembered it being exclusively full of joyful, smiling singers-along. When I watch that video now, almost a month later, it feels a little more staid. Maybe a lot of people felt too sad about the attack to express support that way; maybe a lot of people just didn’t like singing. Maybe in my excitement at recognizing this sports-culture event as it was happening, I remembered it being a little more dramatic.

The crowd looked smaller than the reported attendance of 34,107, but there were still thousands of people for the camera operators to focus on. I wonder why they chose the ones they did, the fans who were in turn waving at the camera, leaning on each other, talking, slowly eating an ice cream bar without getting any on their beards, swaying, belting out the refrain, and then, quickly, getting back to the game. They didn’t even play the whole song. In short, it looked like any other baseball sing-along. But the good will coming out of my TV that night was palpable.

The soundtrack of baseball includes an outside score as well as the rhythms created by the game itself, and musical touchstones like “Sweet Caroline” are fascinating. The opening lyrics (“Where it began/I can’t begin to knowing/But then I know it’s growing strong”) might as well be pulled from quotes from the fans in the Boston Globe article about why they sing the song—as far as they knew, Boston fans sing it because they’ve always sung it, despite the fact that the tradition was only a few years old when that article was written.

But the message from the Yankees as they blared their rival’s anthem at home that night was clear to anyone tuned in to the game. And in a situation like the one that week, where it was easy to feel useless and helpless, that simple musical gesture was very deeply felt. The music of baseball is a part of it that even I can appreciate.

Jessica Barbour is the Associate Editor for Grove Music/Oxford Music Online. You can read her previous blog posts, including “Glissandos and glissandon’ts” and “Wedding Music”. You can read more about Albert Von Tilzer, Jack Norworth, and popular music in Grove Music Online.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: young baseball player hitting the ball. © Tomwang112 via iStockphoto.

The post Baseball scoring appeared first on OUPblog.

May 13, 2013

Insomnia in older adults

What keeps you up at night? Do the effects of sleep deprivation change with age? What are risks associated with insomnia in older adults? Mr. Christopher Kaufmann and Dr. Adam Spira join us to discuss their most recent research in The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences.

How common is insomnia in older adults, and what are the repercussions of chronic sleep problems?

Insomnia is very common among older adults, and is associated with adverse health outcomes, including cognitive and functional decline. It has been estimated that approximately 40-70% of older adults age 65 and older experience sleep problems, with about 20% experiencing severe sleep problems. Insomnia has multiple causes, but chronic health conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, cancer, and osteoarthritis are among the most common health problems associated with poor sleep. Another common cause of insomnia is depression. Furthermore, insomnia in older adults may exacerbate the severity of pre-existing health conditions, perhaps leading to costly health service use.

Who were your participants in this study?

The sample of our study consisted of middle-aged and older adults aged 50 years or older who participated in the longitudinal Health and Retirement Study. Individuals in our sample were assessed for insomnia symptoms in 2006, and their health service utilization was assessed two years later. At baseline, 55% of participants were women, 88% were non-Hispanic white, 59% had a diagnosis of hypertension, 38% had osteoarthritis, and 21 percent had diabetes. Twenty-four percent reported one insomnia symptom, and 18% reported two or more insomnia symptoms at baseline.

According to your research, what is the link between insomnia and the use of health care services in older adults?

We found that individuals reporting one insomnia symptom, as well as two or more insomnia symptoms at baseline, were more likely to use a number of health services two years later compared to those reporting no insomnia symptoms. This health service utilization included hospitalization, use of home healthcare services, and use of a nursing home. Surprisingly, we found this association was still statistically significant for hospitalization and use of any of the three health services after accounting for a number of common health conditions, and depression.

Image courtesy of the authors.

What do your results suggest?

Our results suggest that insomnia is associated with greater use of costly health services, and that perhaps preventing, or at least clinically addressing insomnia symptoms, might minimize healthcare costs for middle-aged and older adults. Our results also suggest that the assessment and recognition of insomnia by clinicians might help identify individuals at greater risk of hospitalization and other costly services. Medical professionals might be able to target and provide more intensive preventive care to individuals reporting insomnia symptoms. Our study found that if the association between the experience of insomnia symptoms and health service use were in fact causal, we would expect to see a six to fourteen percent decrease in health service use. It should be noted that our findings are based on self-reported insomnia symptoms and health service utilization, which is subject to reporting and recall bias. Furthermore, we only examined any use of health services, and we did not assess the duration and frequency of use. Our findings need to be confirmed in other population-based studies of older adults, and more research is needed to examine this association using objective measures of sleep quality and measures that capture the intensity of health service use.

What are some ways to prevent and treat insomnia?

Very often, simple sleep hygiene measures such as reducing environmental stimuli at night, establishing bedtime routines, or avoiding day-time naps would be sufficient to address insomnia. Adequately addressing and managing chronic health conditions can also prevent the development of insomnia. If these measures do not improve sleep, behavioral therapy can be effective. In some cases, sleep medications may be used on a short-term basis. However, the use of sleep medications in older adults, if taken for a longer period of time, has been shown to lead to numerous adverse health outcomes, such as falls, hip fractures, and cognitive and functional impairment.

Mr. Christopher Kaufmann is a doctoral student in the Department of Mental Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. His research interests are in the utilization of health services related to psychiatric disorders, as well as the use of prescription medications among older adults. Dr. Adam Spira is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Mental Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. He studies the link between sleep disturbance and both cognitive and functional decline in older people. Together they are the authors of “Insomnia and Health Services Utilization in Middle-Aged and Older Adults: Results From the Health and Retirement Study” in The Journals of Gerontology Series A, which is available to read for free for a limited time.

The Journals of Gerontology were the first journals on aging published in the United States. The tradition of excellence in these peer-reviewed scientific journals, established in 1946, continues today. The Journals of Gerontology, Series A publishes within its covers the Journal of Gerontology: Biological Sciences and the Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Insomnia in older adults appeared first on OUPblog.

100 years of psychopathology

In 1913, Allgemeine Psychopathologie (General Psychopathology) was published. A guide for young students, doctors and psychologists, it had been completed two years earlier by a 28-year-old German psychiatrist: Karl Jaspers. He aimed to overcome scientific reductionism and establish psychopathology as a new comprehensive science during a period of significant advances in neuroscience. The work had an immediate, dramatic impact and is now a classic in psychiatric literature. Moreover, he established psychopathology as a discipline in its own right — to carefully describe, define, differentiate, and bring order to the chaos of anomalous mental phenomena.The relevance of psychopathology for psychiatry is threefold: it is the common language that allows specialists, belonging to different schools, each one speaking its own jargon, to understand each other; it is the ground for diagnosis and classification in a field where all major conditions are not aetiologically defined disease entities, but exclusively clinically defined syndromes; it makes an indispensable contribution to understanding, a special kind of intelligibility based on the meanings and conditions of possibility of personal experiences.

Department of Psychosis Studies, Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London and OASIS Team, South London and the Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK. Used with permission.

Psychiatrists need both the personal cultivation and thorough scientific education that psychopathology provides. Its emphasis on human experience, meaningfulness, and valid and reliable methodology to approximate human subjectivity makes it the organon of the humanities in psychiatry, and perhaps in medicine in general. When evidence-based guidelines are still scarce (as is the case, for instance, with early psychoses), psychopathological formation seems to be an indispensable resource for the psychiatrist. For example, it provides the ability to feel an atmosphere and attune to situations that are not yet plainly and unambiguously defined. Moreover, Jaspers drew attention to the active role of the patient. As a self-interpreting agent engaged in a world, the patient interacts with his or her basic disorder and contributes to the shaping of the clinical syndromes.

Jaspers was also active in other fields, such as philosophy, which deeply influenced his work as a psychopathologist. General Psychopathology tried to bring the direct investigation and description of clinical phenomena as subjectively experienced by the patients into the field of clinical psychiatry. Specifically, it changed our understanding of psychosis and schizophrenia. Jaspers’ phenomenological analyses of the pre-delusional atmosphere are still considered an outstanding example of “what it is like” to be a person who is undergoing puzzling and ineffable experiential changes which pave the way to full-blown schizophrenic delusions.

Today, Jaspers work continues to reward and inform psychiatrists. His phenomenological method can help solve ongoing diagnostic concerns by improving the validity of present clinical phenotypes and his approach can be integrated with current neurobiological hypotheses. His person-centered approach in clinical practice is very useful to contemporary psychiatry. In fact, patients are seen as meaning-making, participating in their own healing as empowered agents, and their behaviors not necessarily pathological but potentially adaptive. One hundred years on, we’re still learning from Karl Jaspers.

Paolo Fusar-Poli, MD, PhD, RCPsych is Clinical Senior Lecturer at the Department of Psychosis Studies at the Institute of Psychiatry, London and consultant at the OASIS prodromal team, South London and the Maudsley Foundation NHS Trust. Giovanni Stanghellini, MD and Dr. Phil. honoris causa is full professor of Dynamic Psychology and Psychopathology at Chieti University (Italy) and Associate Professor at Diego Portales University in Santiago (Chile). Schizophrenia Bulletin has a special issue on the 100th anniversary of General Psychopathology.

Schizophrenia Bulletin seeks to review recent developments and empirically based hypotheses regarding the etiology and treatment of schizophrenia. They have published a special issue devoted to the centenary of its publication (1913-2013), as well as other publications including the volume One Century of Karl Jaspers General Psychopathology to be published by Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology and neuroscience articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post 100 years of psychopathology appeared first on OUPblog.

Pornography, sperm competition, and behavioural ecology

Over millions of years, evolution by natural selection has produced adaptations in humans: biological and psychological traits that improved human survival and reproduction in ancestral environments. For example, ripe fruit was an infrequent but calorically rich part of the human ancestral diet. We therefore have a sweet tooth that rewards us when we eat ripe fruit.

But evolution works slowly and gradually, over many generations. Sometimes, the environment changes so quickly that our adaptations can’t evolve quickly enough in response to these changes. This is called an “adaptive mismatch.” Today, modern society presents us with many sweet-tasting goodies, like candy, that aren’t healthy for us. And yet, we continue to crave these unhealthy treats because they “parasitize” our sweet preference—an adaption that was designed to reward ripe fruit-eating.

But, what do adaptive mismatches have to do with pornography? A lot.

Heterosexual men become sexually aroused from seeing naked, fertile women. This sexual arousal is an adaptation that motivates men to prepare for the possibility of sex.

Like candy, pornography creates an adaptive mismatch. For a moment, try to see the world not from “human eyes” but from the eyes of an animal biologist. You might think that men’s enjoyment of pornography is bizarre: men are sexually aroused by the sight of ink that’s splattered on magazine pages, or computer pixels that display light. Nobody would argue that men evolved to have sex with magazines or computers. Adaptive mismatch? Quite.

Pornography is a formidable industry, with men as the primary consumers. And because pornography exploits slow-to-change adaptations, investigating men’s preferences in pornography can inform us about those adaptations.

A previous study documented that pornography depicting two men having sex with one woman (MMF) was more prevalent than pornography depicting two women having sex with one man (FFM). However, a different study documented that men report viewing FFM pornography preferentially over MMF pornography. To reconcile these contradictory findings, we recently published in Behavioral Ecology a paper documenting that adult DVDs containing more depictions of MMF on the DVD cover achieve better sales rankings than DVDs containing more depictions of FFM. Our results indicate two important things about men’s sexual psychology: (1) The type of pornography men say they view may differ from what they actually view, and (2) men’s greater sexual arousal from viewing MMF pornography may be a consequence of another adaptive mismatch: adaptations to sperm competition.

Sperm competition occurs when a woman has sex with two or more men within a sufficiently brief period of time, and the different men’s sperm compete to fertilize the ova. Men have evolved adaptations to increase their chances of success in sperm competition. Some adaptations to sperm competition involve increasing sexual arousal. For example, when men estimate a greater likelihood that their romantic partner recently had sex with another man, they ejaculate more sperm the next time they have sex with her, report greater interest in having sex with her, and sometimes, sexually coerce her.

To tie this all together, men’s preference for MMF pornography is evidence of adaptations to sperm competition. Men who see MMF scenes are “witnessing” sperm competition unfold between the two men in that scene. And as sperm competition theory predicts, men have adaptations that cause them to become sexually aroused by the risk of sperm competition, motivating them to purchase adult DVDs that contain depictions of it.

Sperm competition theory may help solve other puzzles about male sexuality. Notably, it may inform the question of why men become jealous—yet simultaneously, sexually aroused—by the thought of their romantic partner having sex with another man.

Michael N. Pham is a graduate student in evolutionary psychology at Oakland University. William F. McKibbin is an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Michigan—Flint. Todd K. Shackelford is chair and professor of psychology at Oakland University. They are the co-authors of the paper ‘Human sperm competition in postindustrial ecologies: sperm competition cues predict adult DVD sales’, published in the journal Behavioural Ecology.

Bringing together significant work on all aspects of the subject, Behavioral Ecology is broad-based and covers both empirical and theoretical approaches. Studies on the whole range of behaving organisms, including plants, invertebrates, vertebrates, and humans, are welcomed.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only earth and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Spermatozoons, floating to ovule. By frentusha, via iStockphoto.

The post Pornography, sperm competition, and behavioural ecology appeared first on OUPblog.

May 12, 2013

A National Short Story Month reading list from Oxford World’s Classics

By Kirsty Doole

In this month’s Oxford World’s Classics reading list, we decided to celebrate National Short Story Month by selecting some of favourite story collections. We have everything here from Gaskell to Cervantes, Fitzgerald to Kafka. But have we missed your favourite? Let us know.

Exemplary Stories by Miguel de Cervantes

While Cervantes is best known for Don Quixote, he also wrote stories, which were actually much more popular in his day than the larger work. The Exemplary Stories range from the picaresque to the satirical, and skilfully draw on colloquial language and farce to create a tension between the everyday and the literary. While Cervantes wants his readers to reach their own moral conclusions, he also paints vivid pictures of the coincidental and the incredible, such as a young nobleman undergoing a change of identity at the behest of a gipsy girl, and two young boys indulging in a life of crime. There are also talking dogs philosophizing in a ward full of syphilitics… and who doesn’t want to read that?

Tales of the Jazz Age by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Everyone knows that Fitzgerald wrote The Great Gatsby (especially after the release of Baz Luhrmann’s film) but he was also a short story writer. Tales of the Jazz Age was his second short story collection, and it contains some of the best examples of his talent as a writer of short fiction. These stories demonstrate the same originality and inventive range as his great novels, as he chronicles the hedonistic 1920s. This collection contains two of his greatest stories, ‘May Day’ and ‘The Diamond as Big as the Ritz’.

Cousin Phillis and Other Stories by Elizabeth Gaskell

Elizabeth Gaskell has long been one of the most popular of Victorian novelists, yet in her lifetime her shorter fictions were just as admired as North and South or Wives and Daughters. This edition’s title story, Cousin Phillis, is a lyrical depiction of a vanishing way of life and a girl’s disappointment in love. The other five stories were all written during the 1850s for Dickens’s periodical Household Words. They range from a quietly original tale of urban poverty and a fallen woman in ‘Lizzie Leigh’ to an historical tale of a great family in ‘Morton Hall’; echoes of the French Revolution, the bleakness of winter in Westmorland, and a tragic secret are brought vividly to life.

A Hunger Artist and Other Stories by Franz Kafka

Enigmatic, satirical, often bleakly humorous, these stories approach human experience at a tangent: a singing mouse, an ape, an inquisitive dog, and a paranoid burrowing creature are among the protagonists, as well as the professional starvation artist. A patient seems to be dying from a metaphysical wound; the war-horse of Alexander the Great steps aside from history and adopts a quiet profession as a lawyer. Fictional meditations on art and artists, and a series of aphorisms that come close to expressing Kafka’s philosophy of life, further explore themes that recur in his major novels.

A portrait of Katherine Mansfield in 1918, by Anne Estelle Rice [public domain]

Selected Stories by Katherine Mansfield

Virginia Woolf was a keen admirer of Katherine Mansfield’s work, saying it was “the only writing I have ever been jealous of”. Other admirers included Thomas Hardy, D. H. Lawrence, and Elizabeth Bowen.

Our edition of her Selected Stories covers the full range of Mansfield’s fiction, from her early satirical stories to the nuanced comedy of ‘The Daughters of the Late Colonel’ and the macabre and ominous ‘A Married Man’s Story’. Ranging between Europe and her native New Zealand, disruption is a constant theme, whether the tone is comic, tragic, nostalgic, or domestic, echoing Mansfield’s disrupted life and the fractured expressions of Modernism.

The Complete Short Stories by Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde was already famous as a wit and raconteur when he first began to publish his short stories in the late 1880s. The stories are full to the brim with Wilde’s originality, literary skill, and sophistication. They include poignant fairy-tales such as ‘The Happy Prince’ and ‘The Selfish Giant’, and the extravagant comedy and social observation of ‘Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime’ and ‘The Canterville Ghost’. They also encompass the daring narrative experiments of ‘The Portrait of Mr. W. H.’, Wilde’s fictional investigation into the identity of the dedicatee of Shakespeare’s sonnets, and the ‘Poems in Prose’, based on the Gospels.

While ‘Decadence’ was a movement that swept most of Europe, its epicentre was Paris. On the eve of Freud’s early discoveries, writers such as Gourmont, Lorrain, Maupassant, Mirbeau, Richepin, Schwob, and Villiers engaged in a species of wild analysis of their own, perfecting the art of short fiction as they did so. Their stories teem with addicts, maniacs, and murderers as they strive to outdo each other. This selection of tales includes well-known writers such as those mentioned above, as well as lesser known figures such as Léon Bloy, Jean Richepin, and the Belgian Georges Rodenbach.

Kirsty Doole is Publicity Manager for Oxford World’s Classics, amongst other things.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Portrait of Katherine Mansfield (1918). By Anne Estelle Rice [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A National Short Story Month reading list from Oxford World’s Classics appeared first on OUPblog.

Israel’s urgent strategic imperative

“Whenever the new Muses present themselves, the masses bristle.”

– Jose Ortega y Gasset, The Dehumanization of Art

It is hard to understand at first, but Israel’s survival is linked to certain core insights of the great Spanish existentialist philosopher, Jose Ortega y Gasset. Although he was speaking to abstract issues of art, culture, and literature, Ortega’s insights can be extended productively to very concrete matters of world politics. More precisely, just as there must take place periodic “revolutions” in the way that we humans look at beauty (Ortega’s intended argument), there must also appear new ways of understanding national strategies.

Strategic theories, like theories of art, are essentially a “net.” In war and peace, only those who cast will catch. Moreover, this net must be constantly re-woven and refined. Without a carefully derived and markedly innovative system of theory, the IDF will be unable to conform its critical order of battle to the constantly changing and increasingly lethal correlation of forces mustering on the regional battlefield.

Not all of the staggering IDF planning problems are purely theoretical or conceptual. Even where strategic studies proceed on a sound intellectual foundation — for example, one that would involve appropriately dialectical reasoning, rather than merely sterile accumulations of collected data — they will still need to remain sheltered from unsound political judgments. This lack of sheltering was the real problem back in the “old days” of Oslo, and it is still likely to be a source of concern in the current intellectual climate of a US-endorsed Road Map.

Yet another expression of utterly twisted cartography, the politics-driven Road Map could quickly override even the most sophisticated and otherwise promising directions of Israeli strategic studies.

What needs to be done?

First, Israeli strategists must look directly, unhesitatingly, and relentlessly at their country’s manifestly existential threats, and then identify these particular threats, promptly and openly, as the primary object and rationale of their inquiries. They must, therefore, reveal an unambiguous hierarchy of what is now most important to safeguard and secure, and display a subsequent obeisance to the determined rank-orderings of this effectively “sacred” hierarchy.

Second, Israeli strategists must fully understand, and without any further delay, that Israel is a system; that existential threats confronting Israel are themselves interrelated; and that the complex effects of these interrelated threats upon Israel must be examined together.

Third, Israeli strategists must understand that the world arena is best understood as a system, and that any disintegration of power and authority structures within this wider macro-system will impact, with more-or-less enormous and at-least partially foreseeable consequences, the Israeli micro-system. Since the seventeenth-century and the Peace of Westphalia (1648), all world politics have been anarchic. Still, anarchy is not the same as chaos. How shall Israel prepare to survive in a world of growing chaos?

Fourth, Israeli strategists must consciously and conspicuously turn away from too-much “prudence,” that is, from altogether too-mainstream kinds of strategic analyses. For the moment, these assessments may please their designated military and political advocates, but they could nonetheless remain potentially valueless, or even counter-productive, for vital Israeli policy formations.

Fourth, Israeli strategists must consciously and conspicuously turn away from too-much “prudence,” that is, from altogether too-mainstream kinds of strategic analyses. For the moment, these assessments may please their designated military and political advocates, but they could nonetheless remain potentially valueless, or even counter-productive, for vital Israeli policy formations.

A principal assumption of current Israeli strategic studies is the always idée fixe of rationality in enemy calculations. Because the functioning of nuclear deterrence necessarily depends upon this core assumption, Israeli strategists consequently turn away from any unexpected circumstances in which rationality would not be expected to operate. The predictable and dangerous result is that Israeli strategic studies may now accomplish too-little to prepare the political leadership in Jerusalem for increasingly probable confrontations with irrational enemy states, or with equally-irrational state proxies.

Naturally, Israeli strategists must soon acknowledge, more forthrightly, the still-conceivable fusion of a non-rational leadership in Tehran, with a nuclear military capacity. This combination, after all, could produce what amounts to a suicide-bomber writ large. However, irrationality is not the same as madness; such national decision-makers would value certain preferences more highly than continued national survival.

Fifth, Israeli strategists, in their work, must learn to consider seemingly irrelevant literature, not the mundane and narrowly technical materials normally generated by American strategists, but the authentically creative and artistic product of writers, poets, and playwrights. The broad intellectual insights that can be gleaned from such serious literature can provide a fundamentally better source of strategic understanding than the visually-impressive, but often misleading matrices, mathematics, metaphors, and scenarios of our military “experts.”

Sixth, Israeli strategists need to recognize the distinct advantages of private as opposed to collective academic thought. There is a suitably correct time for collaborative or “team” investigations, but in certain matters concerning Israeli security, we may sometimes discover greater conceptual value in the private musings of certain talented single individuals, than in the combined efforts of entire academic centers.

Seventh, Israeli strategists now need to open up, again, and with far greater diligence and formal insight, the question of nuclear ambiguity. Here it must be understood that examining the “bomb in the basement” is not merely a matter of belaboring the obvious, but rather one of optimally exploiting appropriate and variable levels of nuclear disclosure, for purposes of enhanced nuclear deterrence, and, quite possibly, non-nuclear preemptions.

Eighth, Israeli strategists still need to widen their consideration of the broader national questions of nuclear weapons and national strategy. Key issues will be those of nuclear targeting doctrine, and ballistic missile defense. Corollary concerns should center on investigations of the “rationality of pretended irrationality” (a strategy that may now already be underway in North Korean nuclear posturing), and on more-or-less explicit intimations of a refined “Samson” doctrine.

Ninth, Israeli strategists must cease their contemplation of an end to national existence as a purely objective consideration. These strategists can somehow contemplate the literal end of Israel in their formal studies, and still persevere quite calmly in their most routine day-to-day affairs. This ironic and potentially counterproductive juxtaposition would no longer be the case if these flesh-and-blood scholars could begin to contemplate the very moment of Israel’s collective disappearance.

Tenth, Israeli strategists should pay special attention to the compelling requirements of scholarly audacity — to steer clear of the comfortable intellectual middle-ground. Individual strategists will need to take risks, both personal and professional, in finding serious policy answers to the vital strategic questions. From the beginning, Israelis have generally exhibited remarkable and even unique levels of personal bravery in war. As yet, however, there have been substantially fewer evident examples of “bravery” in Israeli strategic scholarship. For the most part, this scholarship has been narrowly technical and viscerally imitative of its American antecedents.

Israel has always had to travel along precipices. From the beginning, therefore, its overriding obligation has been to somehow keep its balance. Now, when still-growing and sometimes intersecting sources of instability present themselves, this obligation can best be met by accepting certain new and more creative forms of strategic scholarship. In the end, Israel’s fate will hang upon its willingness to accept and refine “new Muses” in all areas of its indispensable strategic thought.

Louis René Beres (Ph.D., Princeton, 1971) is the author of ten books and several hundred scholarly articles dealing with international relations and international law. He has lectured and published widely on strategic matters in Israel, Europe, and the United States. Professor Beres’ writings also appear in many major newspapers and magazines, including US News & World Report and The Atlantic.

If you are interested in this subject, you may be interested in The Practice of Strategy: From Alexander the Great to the Present, edited by John Andreas Olsen and Colin S. Gray. It focuses on grand strategy and military strategy as practiced over an extended period of time and under very different circumstances, from the campaigns of Alexander the Great to insurgencies and counter-insurgencies in present-day Afghanistan and Iraq.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: chess board with figure. Image by DusanJankovic, iStockphoto.

The post Israel’s urgent strategic imperative appeared first on OUPblog.

May 11, 2013

How sequesterable are you?

Leonard Jason, Madison Sunnquist, Suzanna So, and Sarah Callahan have created an infographic regarding the sequestration and its impacts.

You can also download a pdf of the infographic.

Leonard A. Jason, professor of clinical and community psychology at DePaul University and director of the Center for Community Research, is the author of Principles of Social Change published by Oxford University Press. Madison Sunnquist, Suzanna So, and Sarah Callahan are research assistants at the Center for Community Psychology at DePaul University.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only social sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Infographic courtesy of the author.

The post How sequesterable are you? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers