Oxford University Press's Blog, page 943

May 20, 2013

The “public safety” exception to Miranda then and now

In 1984 a 6-3 majority of the US Supreme Court established the “public safety” exception to Miranda in a case called New York v. Quarles. Unfortunately, the factual basis for the exception the Court made in this case was quite weak.

A woman told the police she had just been raped, that the rapist had just entered a specified supermarket and that he was carrying a gun. Officer Kraft entered the store, only a few steps behind Mr. Quarles, the alleged rapist. Upon seeing the officer right behind him, Quarles ran toward the rear of the store. Officer Kraft pursued him with a drawn gun and ordered him to stop and put his hands over his head.

A minute or two later, three other police officers arrived on the scene. But Kraft was the first one to reach Mr. Quarles. After frisking the defendant, the officer noticed he was wearing an empty shoulder holster. The officer then handcuffed Mr. Quarles and — without giving him the Miranda warnings — asked him where his gun was. Quarles nodded in the direction of some nearby empty cartons and told the officer “the gun is over there.” In a couple of minutes, the police found the gun.

The Supreme Court admitted the defendant’s statement as well as the gun. Justice Rehnquist, who wrote the majority opinion, summed up the situation as follows: “So long as the gun was concealed somewhere in the supermarket, with its actual whereabouts unknown, it obviously posed more than one danger to the public safety: an accomplice might make use of it, a customer or employee might later come upon it.”

This summary of the facts is misleading. Although the arrest took place in a supermarket, it occurred some time after midnight. The store was completely deserted except for the clerks at the checkout counters. All that one of the four officers had to do was stand outside the entrance to the store and tell any potential customer that because of a police emergency he or she could not enter the store for ten or fifteen minutes. Moreover, Officer Kraft was so close behind Quarles before he apprehended the defendant that he must have known Mr. Quarles’s gun was almost within reaching distance of him.

Nobody indicated that Mr. Quarles had an accomplice. (Nor did he in fact have one.) Moreover, as the New York courts (which had dealt with the case before it reached the US Supreme Court) had pointed out when they rejected the contention that under the circumstances the police were entitled to a “public safety” exception to Miranda, the arresting officers were sufficiently confident of their safety to put away their guns once they surrounded the defendant.

To sum up, applying a “public safety” exception to the facts of the Quarles case looks like quite a stretch. On the other hand, applying the exception to the recent Boston Marathon bombing case appears quite different. The Boston case is one that does call for a “public safety” exception to Miranda immediately after the bomber was apprehended.

When the explosions first occurred, law enforcement officials had no idea what they were up against. They knew neither the size nor shape of a possibly large conspiracy to wreak havoc or to terrorize the public.

There is reason to believe that the Department of Justice reads the “public safety” exception to Miranda more expansively than I think it should be read, applying it even when there is no immediate threat to public safety. I disagree. It should be plain that law enforcement officials could not delay giving the Miranda warnings indefinitely. However, I believe that in the Boston case the police could have done so long enough to satisfy themselves that the bombing was not part of, or not being coordinated with, another or larger act of terrorism. If law enforcement officers had done so (and at this point it is unclear precisely what actually happened), then they would have made a proper use of the “public safety” exception.

Yale Kamisar is the Clarence Darrow Distinguished University Professor Emeritus of Law at the University of Michigan and a nationally recognized authority on constitutional law and criminal procedure.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Symbol of law and justice in the empty courtroom, law and justice concept. iStockphoto.

The post The “public safety” exception to Miranda then and now appeared first on OUPblog.

The future of user-generated content is now

In its December press release, the European Commission agreed to reopen the debate on copyright. A dialogue will be launched to tackle several major issues with the current copyright framework, including the topic ‘user-generated content’. The outcome of this open discussion should guide the Commission in its mission to modernize the European copyright framework and adapt it to the digital economy. ‘User-generated content’ is a major bone of contention in the copyright debate. It is also a confusing concept in that it fails to distinguish original content from derivative works, which is the actual point of disagreement between rights holders, providers of online services and their users. Derivative works are based on one or more pre-existing copyright protected works and the right to create them is exclusively reserved to their original creators. The standard practice for rights holders is to license such rights on an individual basis, so as to control the adaptation of their work and to generate income from the commercialization of derivatives. This classic licensing model has arguably lost some of its relevance in the internet age, whereas copyright is at best misunderstood if not simply ignored by most users.

Nowadays everyone has easy access to user-generated content. Recent advances in technology have reduced the costs of creating and sharing derivative works, and the mass popularity of social media such as YouTube, Facebook or Tumblr has prompted the emergence of new social and cultural behaviours, where people are now empowered to become active creators. This phenomenon, called the ‘read/write culture’ by Lawrence Lessig but often referred to as the ‘remix culture’, has radically transformed our creative landscape and favoured the rapid development of social media, which provide the backbone for instantaneous content distribution. Over a few years these companies have also built vibrant audiences eager to consume, create and share, and they have found innovative ways to serve these audiences and to fuel a new type of creativity.

Nowadays everyone has easy access to user-generated content. Recent advances in technology have reduced the costs of creating and sharing derivative works, and the mass popularity of social media such as YouTube, Facebook or Tumblr has prompted the emergence of new social and cultural behaviours, where people are now empowered to become active creators. This phenomenon, called the ‘read/write culture’ by Lawrence Lessig but often referred to as the ‘remix culture’, has radically transformed our creative landscape and favoured the rapid development of social media, which provide the backbone for instantaneous content distribution. Over a few years these companies have also built vibrant audiences eager to consume, create and share, and they have found innovative ways to serve these audiences and to fuel a new type of creativity.

The fast development of social media companies in Europe has also been enabled in part by the ‘hosting’ provision of the e-Commerce Directive, which is loosely based on similar provisions in the US Digital Millennium Copyright Act and analogously limits the liability of internet service providers for hosting infringing content, provided they swiftly remove that content as soon as they become aware of it, usually upon a rights holder’s notification. Even if it is true that this limitation of liability is indispensable for ISPs, it places the monitoring burden on the rights holders, since the directive clearly states that there is no obligation on ISPs to monitor for infringing content. This is the apple of discord for them, as they strongly disagree with the sheer principle of monitoring their own content. This situation affects in turn social media users who are immersed in the remix culture. That culture does not recognize the complexities of copyright law: for example, crediting the original author is deemed sufficient when a derivative work is created for non-commercial purposes, although this is clearly not sufficient from a legal point of view, absent any fair use defences. Users are often left confused about how and why the content they intend to share is infringing on someone else’s copyright.

It is clear that user-generated content is here to stay. Finding inspiration in the works of others and building upon it has become a socially—if not legally—endorsed process of self-expression and this fact is becoming increasingly difficult to ignore, when 72 hours of video are uploaded on to YouTube every minute. One can only welcome the decision of the European Commission to prioritize this issue and hope that its cultural and social dimensions won’t be underestimated. It is in the interest of all stakeholders to closely collaborate, so as to find a solution that works for everyone. Rights holders might want to become more open to the concept of user-generated content and show more flexibility towards the use of their rights. ISPs and social media must act responsibly and go beyond the minimal requirements in limiting their liability in case of copyright infringement. Focus should be put on educating their users, so that they understand basic copyright concepts and feel more secure when sharing content online. Finally, the European Commission should supervise the debate as transparently as possible without neglecting its social and cultural implications. To that extent, the involvement of the digital agenda team and of the Culture Directorate is a sign that advancing towards a balanced copyright framework has been understood as a concerted effort and this acknowledgement alone should be praised.

A version of this article originally appeared as an editorial in the Journal of Intellectual Property Law and Practice.

Grégoire Marino is a IP & IT enthusiast who likes to look at copyright and patent issues from a social and public policy perspective. He currently works as a rights and privacy specialist for a leading social sound platform and serves as editorial board member of OUP’s Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice. Feel free to ask him anything here.

Journal of Intellectual Property Law and Practice is a peer-reviewed journal dedicated to intellectual property law and practice. Published monthly, coverage includes the full range of substantive IP topics, practice-related matters such as litigation, enforcement, drafting and transactions, plus relevant aspects of related subjects such as competition and world trade law. Read the JIPLP blog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Cute woman with earphones and white laptop in the park. Photo by Osuleo, iStockphoto.

The post The future of user-generated content is now appeared first on OUPblog.

They’re watching, but are they seeing?

Notwithstanding the many privacy concerns it raises, the role of video surveillance footage in cracking the Boston terror attack case in a matter of days is well known. Such footage played an equally critical role in tracking down the bombers of the 2005 London attacks. However, in 2005 investigators took weeks to manually sift through about two thousand hours of video footage. This time around, thousands of hours of video were analyzed in barely 48 hours.

The city of Boston is smaller than London; still, it has thousands of surveillance cameras, very similar to the London of 2005. What has changed is technology: video analysis has become significantly more sophisticated in the years since 2005. For example, pre-processing tools are able to filter hours of video footage in, say, an empty subway station at night. Investigators are able to focus only on periods of activity rather than patiently watch footage of an empty platform for hours on end.

Of course, more crowded scenes, especially those as packed as the sidewalks alongside the marathon route require far more sophisticated technology, much of which is still in its infancy. Today there are many commercial video analytics tools that claim to be able to detect a person leaving a bag or backpack and walking away. Such tools are certainly very useful in narrowing down portions of video footage to be analyzed manually during post-incident investigations. But can they reliably alert us in real-time without generating too many false positives? For example, you lay down a brief case and move behind a pillar to find a quiet place to make a phone call. A video surveillance system might well conclude that you have left the scene and your bag is a potential threat. Hundreds of such warnings might be generated every minute — who is to monitor and decide which ones to follow up on?

Another technique that has seen significant advances in recent years is tracking moving objects in videos, especially human beings. Further, it is now possible (only barely though), to track the same person as he moves across large distances as he moves in and out of the field of view of multiple cameras. So, in principle, a hypothetical `big brother’ central server that processes feeds from multiple cameras should be able to track anyone suspected in a ‘left bag’ event and verify whether they rapidly walk away from the scene or not. Of course, bandwidth remains a limitation, which is why many video analytics solutions rely on local ‘event detection’ at the camera level so as to minimize transferring too much data across a network. Further, in such situations, different cameras need to be ‘told’ to track a ‘particular’ person seen by another camera, and that too in a bandwidth efficient manner. So much work remains to be done for efficient large-scale multi-camera tracking.

But there is more: Many recent terror attacks, especially in India, share a similar modus operendi — the terrorist leaves his dangerous cargo on a bicycle that he parks in a crowded market and walks away, seemingly on an innocent shopping errand. Should our central server raise an alarm? After all, many people genuinely shop while their two-wheeled vehicle, bicycle or motorbike, lies parked nearby, perhaps also loaded with their recent purchases. Do we warn citizens of dire consequences if they leave packets on their bikes?

Clearly our central server needs to work harder, track more people, for longer. Most importantly, it needs to reason. However ubiquitous video cameras might be, they still cannot be everywhere — certainly not in every store, restaurant, or loo! The central server would need to explain away the actions of most of the people it tracked, and narrow down on only a few, such as someone entering a subway station, leaving a bag and then boarding a train. (Such ‘explaining away’ to home in on the right answer is an example of ‘abductive reasoning’. If it appears difficult for a machine to mimic, take note that just such reasoning has in fact already been used by IBM’s Watson program that won the 2009 Jeopardy! competition.)

Moreover, how might the video surveillance servers of the future come to know what is normal behavior and what is not? Certainly it would be impossible to catalogue every instance of normalness for the machine to ‘look up’ and compare against. Instead, the machine would need to learn, using massive amounts of ‘normal’ video footage. Difficult, but by no means impossible any more. Consider this: each year over 15 million hours of video is uploaded onto YouTube. In contrast, a human being is exposed to barely half a million hours of ‘video experience’ over a lifetime (90 years × 365 days × 16 hours/day). Yet we learn, and rather early on, the difference between normal and abnormal, be it suspicious or merely eccentric. Granted that eccentricity is not entirely absent from YouTube videos, still, there is more than enough ‘normal’ video available today for machines to learn from, if only they knew how.

Intelligent systems such as our hypothetical central video-surveillance server need to go beyond merely looking at the world while watching us. They also need to continuously learn from the data they experience, so as to see and focus on what is actually important. Only then can they connect the dots and make reasonably accurate predictions, so corrective action can be taken in time, and not only after a tragedy has occurred.

Finally, the cycle we just described above: Look, Listen, and Learn, so as to Connect, Predict and finally Correct, will be a common feature of the highly connected ‘web-intelligent’ systems of the not too distant future, be they for video surveillance, self-driving cars, or even the smart-grid.

Gautam Shroff is Vice President & Chief Scientist, Tata Consultancy Services and head of the TCS Innovation Lab in Delhi, India. He occasionally teaches in an adjunct capacity at the IIT Delhi and IIIT Delhi, as well as online via Coursera. He is the author of The Intelligent Web: Search, smart algorithms, and big data.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only technology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: High tech overhead security camera at a government owned building. Photo © trekandshoot via iStockphoto.

The post They’re watching, but are they seeing? appeared first on OUPblog.

Thinking gender and speaking international law

Gender studies begin by asking how you understand gender, the boundary, the space, the difference, the divergence and the sameness between m and f. How femininity and masculinity are knowable, reversible, collapsible, forgettable, changeable and open to renegotiation, supposedly given, fixed, yet mutable.

As a feminist theorist who writes on international law with a particular focus on collective security, the use of force and peacekeeping, I examine the constructed spaces of international law and its institutions. I attempt to delineate the rules and practices of the Security Council, the International Criminal Court, the Convention to Eliminate All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), and the work of UN Women and the UN Secretary-General’s Special Advisor on Sexual Violence. Of course there will be controversies but they will be contestable in defined and expected (legal) spaces.

As a feminist theorist who writes on international law with a particular focus on collective security, the use of force and peacekeeping, I examine the constructed spaces of international law and its institutions. I attempt to delineate the rules and practices of the Security Council, the International Criminal Court, the Convention to Eliminate All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), and the work of UN Women and the UN Secretary-General’s Special Advisor on Sexual Violence. Of course there will be controversies but they will be contestable in defined and expected (legal) spaces.

Yet feminist approaches to international law began with a foundational engagement with the boundaries and biases in international law rather than a focus on specific arenas of rights and protections applied to women. In The Boundaries of International Law, Charlesworth and Chinkin wrote of re-drawing the boundaries of international law in 2000 and labelled was ‘structural bias feminism’ for its analysis of the structures and foundations of the discipline. They analysed the mechanisms, forms, and functions at the foundations of international law through the lens of gender. They sketched their gender theory from contemporary feminist writing outside of international law and legal scholarship, drawing on gender theory and feminist thinking to develop insight and approaches to the structures of international law. Feminist approaches to international law need to re-connect to these wider approaches to gender, sexuality, and feminist thinking and activism.

Recently, the SOAS Centre for Gender Studies workshop on Border Crossings showcased scholarship on gender across faculties, departments, schools and centres at SOAS, University of London. Staff and students spoke on ‘New Directions in Gender at SOAS’ and organised around the theme of Border Crossing. Over 10-11 May 2013 gender studies scholars at SOAS demonstrated the strength and resonance of the discipline in papers that crossed places and spaces, temporalities as well as disciplines and methods. This was as challenging as it was invigorating. When does an international lawyer listen to an anthropologist, historian, ethnographer, or South Asian studies scholar and hear resonance in her own work?

Mainstream approaches to international law recognise the nexus between the international and the everyday, yet this boundary crossing is little explored within the discipline of international law. If gender is a primary human organising principle that influences our everyday lives (before you were born somebody asked, are you a girl or boy?) once we disrupt the f and m binary we bring wonder and engagement with a whole list of further binaries: rational/emotional, nature/culture, objective/subjective, written/visual, hard/soft, international/everyday, high culture/low culture, public/private, home/diaspora, mind/body. Binaries are transposed into continuums of knowing and not knowing, and positives constructed by the existence of the negative, the other.

At the same time we are forced to remember that we all create borders and we must be mindful of creating new boundaries within our thinking, especially in terms of who speaks, how we speak, who is visible, and who is heard. Multidisciplinary spaces are not the same as interdisciplinary spaces. Asking how we can speak across borders (of knowledge, space, language) is a question of continual importance. Interdisciplinary work shifts beyond the bounded interaction within other disciplines towards a reinvigoration of our methods and thinking.

As international lawyers we must also recall the preoccupation with land and territory that borders dictate, even in crossing. Boundaries and borders privilege land and enclosure or corporeality over the flow of unbounded spaces. Spaces undefined by borders (for example, the ocean, airspace, and cyberspace) are increasingly relevant to post-millennium international law. New forms of regulation and disciplining take place alongside the unbounded, interdisciplinary forming of ideas and revolutions. For example, the freedom of the ocean alongside the unseen bodies and boats left untethered to land, untethered from statehood and often denied citizenship (belonging), presents a conundrum. Finite legal distinctions about who may cross from sea safely onto land require attention from international lawyers preoccupied with sovereignty as known lands, borders, and boundaries laid neatly via rules.

Feminist approaches within international law must see the body bag, the state, the border as equally as we might conceive of interrogating the ocean as a regulated space despite its lack of boundaries. In the era of remote airstrikes, airspace presents a similar challenge, as does the unconfined yet regulated space of our virtual worlds. The failure to see unbounded space as regulated is to reproduce the bodies of war and law whose enclosure and death international law remains complicit in. The contradiction, equivalent to the fixed yet mutable space of knowing gender, is that the space of the ill-defined border also represents a new way of crossing and is a space of innovation. Gender studies ask the international lawyer to hear the peripheral subject in the borderless space, to cross her borders of knowing, and to see outside the boundaries of the discipline.

Gina Heathcote is the author of The Law on the Use of Force: a Feminist Analysis and a contributor to the forthcoming The Oxford Handbook of the Use of Force in International Law. She lectures in Gender Studies and Public International Law at SOAS, University of London.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in Public International Law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Law. © Bartłomiej Senkowski via iStockphoto.

The post Thinking gender and speaking international law appeared first on OUPblog.

Law, gerontology, and human rights: can we connect them all?

Historically, law was not generally considered an important part of gerontological science. As noted by Doron & Hofman in 2005, the law was, at best, considered part of gerontology in that it played a part in the shaping of public policy towards the older population, or was incidental to ethical discussions connected with old age. At worst, gerontology has simply ignored those aspects of the law connected with the old, and kept lawyers out of its province.

Yet in recent years there have been winds of change. Lawyers and gerontologist have started to work together and have slowly but surely developed what is becoming known as “Jurisprudential Gerontology” (or “Geriatric Jurisprudence“): a true inter, multi, and trans-disciplinary project that looks into the fascinating interactions between law, society, and aging, in all its different aspects. These changes have become much more relevant as the UN has started to engage in the process to establish a new convention for the rights of older persons.

As part of this attempt to “connect” law, human rights, and gerontology, I have recently conducted a study on the European Court of Justice. The European Court of Justice (ECJ) is considered by many to be the most important judicial institution of the European Union today. Nevertheless, despite the potential importance and relevance of the ECJ rulings to the lives and rights of older Europeans, no research has attempted to analyze or study the ECJ rulings in a gerontological context.

Using a mixed, quantitative method (measuring and testing through statistical tools) and qualitative method (understanding the content through textual analysis), a sample of ECJ cases involving older persons were collected and descriptively analyzed. In establishing the sample, an internet-based computerized keyword search was conducted within the ECJ official website. The preliminary search identified 1,325 cases, out of which 123 “direct cases” were found (i.e. cases that included issues directly relevant to rights of older persons).

Analyzing these results found that the 123 cases were spread throughout the period of 1994 to 2009 in the following way:

Number of cases per year

As seen above, there is no clear pattern of either increase of decrease in the number of cases throughout the years, and on average, in most of the time period, each year between 5–10 cases were filed. This equals to 1%-2% of the general annual new case load of the ECJ.

From a legal issue perspective, almost half the cases (58/47.2%) were categorized by the ECJ as “Social Policy” issues, while the two other major legal issues were Free Movement of Persons (29/23.6%) and Social Security for Migrant Workers (26/21.1%). Only very few elder rights cases involved issues like Competition (3 cases), or Principles of Community Law (1 case). Attempting to move beyond the ECJ’s own categorization, and analyzing the actual legal issues, it was found that the vast majority of the cases involved issues of pensions: either state funded pensions (61/49.6%) or employer-based occupational pensions (36/29.3%). The rest of the cases were mostly age discrimination, mandatory retirement, or attendance/home care (all of them 6 cases each).

In conclusion, it could be said on the one hand that the number of elder rights cases brought before the ECJ is very low, and their overall quantitative weight is minor at best. Yet on the other hand, within these limited numbers of cases and narrow scope of legal decisions, the outcomes are encouraging. In the majority of the cases the court rules in favor of the elderly. Overall then, the findings of this study suggest that the ECJ can potentially serve as an important protector of rights of older Europeans, if, and to the extent that, these cases reach its jurisdiction.

Prof. Israel (Issi) Doron is the Head of the Department of Gerontology at the University of Haifa, Israel, and the Past President of the Israeli Gerontological Society. His research focuses on the relationships between law, aging and human rights, with specific interest in international human rights of older persons. His paper ‘Older Europeans and the European Courts of Justice’ appears in the journal Age and Ageing and can be read in full and for free for a limited time.

Age and Ageing is an international journal publishing refereed original articles and commissioned reviews on geriatric medicine and gerontology. Its range includes research on ageing and clinical, epidemiological, and psychological aspects of later life.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Symbol of law and justice in the empty courtroom, law and justice concept. Photo by VladimirCetinski, iStockphoto.

The post Law, gerontology, and human rights: can we connect them all? appeared first on OUPblog.

May 19, 2013

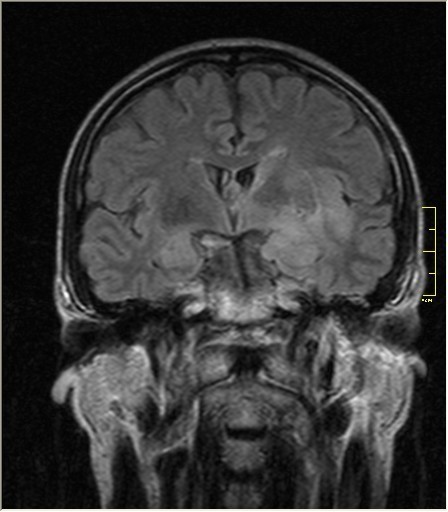

Dangerous assumptions in neuroscience

I’ve spent decades in magnetic resonance research and since 1980 my colleagues and I have been studying the human brain. Like many fields of science, it is astounding to reflect on the progress made in the uses of magnetic resonance which has gone from being a physicist’s means of studying the nucleus to an omnipresent tool for clinical medicine and biological research, especially in neuroscience. Our society holds great hopes for brain research. The Obama administration recently announced a “Brain Activity Map” project that would seek “to advance the knowledge of the brain’s billions of neurons and gain greater insights into perception, actions, and ultimately, consciousness.” However, the work that my colleagues and I have done to understand brain metabolism and function argues that some of the enthusiasm shown for these methods needs a fundamental re-examination.

In essence, I have seen too much scientific work that starts with assumptions that we know and have a solid and consensus-driven understanding of concepts like memory or consciousness when in fact we do not and cannot. Countless tests of “memory” that track activated areas of the brain via fMRI have abandoned scientific observation and induction in favor of a priori assumptions about words or ideas that have value during common usage but are not empirical concepts. What we now know about consciousness from brain imaging is that certain measurable brain properties, such as the total neuronal energy consumption, are necessary for the person to be in the state of consciousness as defined by the anesthesiologist during surgery. As more properties, including brain activities, necessary for a person to be in the state of consciousness are uncovered, the better we will understand it, but we will not get there by trying to define that elusive intangible called consciousness.

Image Credit: Brain MRI, 60M. Photo by © Nevit Dilmen, Creative Commons via Wikimedia Commons.

While there are marvelous results to be gained from careful research on brain metabolism and blood flow as measured by fMRI, there is little to be gained by making assumptions about the human mind. We shouldn’t leap from early but exciting understanding of brain activities necessary for a person’s behavior to assumptions about mental processes presumed to underlie those behaviors. Once we are trained to do things reproducibly — like recognizing a face or avoiding a moving automobile — brain activity supports our response. While we (as scientists) know a lot about how the muscle receives electrical impulses, we would never assert that the biceps, triceps, and deltoids lift a bride over the threshold after a wedding — the groom does. Even as we learn, with astounding precision, about which areas of the visual cortex are activated when the person learns to differentiate between cars and vases, we should not assume that the brain makes this distinction. It is the person who decides and acts; it is the organ — the muscle or brain — that supports her behavior.

One can postulate many reasons for society’s enthusiasm to translate basic research into useful applications in health and control. Nevertheless, it is dangerous for a subtle collective willingness among research scientists to replace traditional scientific methods that are producing wonderful descriptions of the brain’s support of observable behaviors with claims of having found a physical basis for mental concepts like working memory or attention.

Thomas Nagel’s recent book offers a very clear lens for this approach. He proposes that science has failed as an epistemological method because material science cannot explain the mind. Nagel argues that the mind obviously exists, and since chemistry and physics can’t explain it then science has failed and we must look for alternate epistemologies. I certainly agree that physical science cannot explain mind but I would depart from Nagel’s solution for two important reasons. While he defines physical science as proposing to explain everything, the more realistic and generally held view is that science is capable of understanding some aspects of the world but not necessarily all. We can’t combine the subjective views of the mind held by literature, psychology, philosophy, and everyday life with measurements of neuronal activities to give us a scientific, objective, or complete description of mind. However this is a failing of material science only if one holds a nineteenth century view that material science can explain everything in the world, a view discarded when the limits of classical physics were revealed by quantum mechanics and relativity.

As Neils Bohr succinctly observed “Physics does not tell us what nature is but rather tells us what we can say about nature.”

Robert G. Shulman is a biophysicist who has pioneered the use of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and other spectroscopic techniques in physics, biochemistry, and brain imaging. He is the author of Brain Imaging: What it Can (and Cannot) Tell Us About Consciousness. His original studies created active fields of investigation in all these disciplines. He is the Sterling Professor (Emeritus) of Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry at Yale University where he formed the Magnetic Resonance Center, taught Biochemistry, Biophysics, and Literature, and was Director of the Division of Biological Sciences. He is a member of the National Academy of Sciences and of the Institute of Medicine.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology and neuroscience articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Dangerous assumptions in neuroscience appeared first on OUPblog.

Mindful exercise and mental health

There is currently extensive use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) — also known as integrative or mind-body medicine — in the United States to sustain well-being in both aging baby boomers and in children and adolescents. The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) defines CAM therapies as “a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not generally considered part of conventional medicine,” with “conventional” medicine being defined as the approaches used by clinicians in the routine daily practice of Western or allopathic medicine that are within the currently accepted standard of care.

The most recent comprehensive assessment of CAM use in the United States found that roughly 40% of US adults had used at least one CAM therapy within the past year. In addition, Americans make more visits to CAM providers each year than to primary care physicians and spend at least as much money on out-of-pocket expenses for CAM services as they do for all conventional physician services combined. Patients with mental disorders turn to CAM for relief of symptoms of anxiety, mood, insomnia, impaired cognition, and perceived stress. The most commonly used CAM techniques include prayer for health and the use of multivitamin supplementation. Given widespread use of CAM services among patients, there is an urgent need for greater awareness and familiarity with its applications and outcomes.

As baby boomers age and increase use of CAM, mental health professionals require a working knowledge of CAM techniques intended to address late life mood disorders. An estimated 33-88% of older adults will use CAM therapies, including those with late-life depression and bipolar disorder. CAM treatments of mood and anxiety disorders include acupuncture, deep breathing exercises, massage therapy, meditation, naturopathy, and yoga.

Complementary and alternative medicine encompasses a number of techniques collectively known as mindful exercise (e.g. yoga, Qigong, and Tai Chi), or meditation. This ‘physical exercise executed with a profound inwardly directed contemplative focus’ is increasingly utilized for improving psychological well-being. In general, mindful physical exercise contains the following key elements:

a non-competitive, non-judgmental meditative component,

mental focus on muscular movement and movement awareness combined with a low to moderate level of muscular activity,

centered breathing,

a focus on anatomic alignment (i.e., spine, trunk, and pelvis) and proper physical form,

energy centric awareness of individual flow of intrinsic body energy, otherwise known as prana, life force, qi, or Kundalini.

Mindful exercise has been shown to provide an immediate source of relaxation and mental quiescence. Scientific evidence has shown that medical conditions such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, insulin resistance, depression, and anxiety disorders respond favorably to mindful exercises.

There is a growing database of the physiological effects of mindful exercise and meditation. Tai Chi and Qi Gong have been shown to promote relaxation and decrease sympathetic output, and to benefit anxiety, depression, blood pressure, and recovery from immune-mediated diseases. Tai Chi and Qi Gong have been shown to improve immune function and vaccine-response. These practices have also been shown to increase blood levels of endorphins and baroreflex sensitivity, and to reduce levels of inflammatory markers (CRP), adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH), and cortisol, implicating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis as a mediator of stress and anxiety reduction. Brain wave or electroencephalopathy (EEG) studies of participants undergoing Tai Chi and Qi Gong exercise have found increased frontal EEG alpha, beta, and theta wave activity, suggesting increased relaxation and attentiveness. These changes have not been found in aerobic exercise controls.

Yogic meditation (Kirtan Kriya) for stressed family dementia caregivers resulted in lower levels of depressive symptoms, and improvements in mental health and cognitive functioning. Participants in the yogic meditation group showed a 43% improvement in telomerase activity after 12 minutes of daily practice for 8 weeks, compared with 3.7% in relaxation music control participants. This suggests that brief daily meditation practices can benefit stress-induced cellular aging. Kirtan Kriya reversed the pattern of increased NF-κB-related transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and decreased IRF1-related transcription of innate antiviral response genes in distressed dementia caregivers. This reinforces the relationship between stress reduction and beneficial immune response. In the same study, nine caregivers received brain FDG-PET scans at baseline and post-intervention. When comparing the regional cerebral metabolism between groups, significant differences over time were found in different patterns of regional cerebral metabolism suggesting brain-fitness effect different from passive relaxation.

Studies of meditation also report decreased sympathetic nervous activity and increased parasympathetic activity associated with decreased heart rate and blood pressure, decreased respiratory rate, and decreased oxygen metabolism. Functional neuroimaging studies have been able to corroborate these subjective experiences by demonstrating the up-regulation in brain regions of internalized attention and emotion processing with meditation.

In a recent systematic review of neurobiological and clinical features of mindfulness meditations, Chiesa and Serretti (2010) provided evidence on the neurobiological changes related to Mindfulness Meditation (MM) practice in psychiatric disorders. Meditation practices that focus on concentration of an object or mantra seem to elicit the activation of fronto-parietal networks of internalized attention; meditation techniques that focus on breathing may elicit additional activation of paralimbic regions of insula and anterior cingulate; and meditation techniques that focus on emotion may elicit fronto-limbic activation. Future studies will be needed to disentangle the brain activation patterns related to different meditation traditions.

Given the noninvasive nature of mindful exercise and meditation, these exercises are an appropriate option for consumers and clinicians, particularly for conditions that have been examined in controlled studies. Significant evidence supports the assertion that Tai Chi and Qi Gong and yoga and meditation can improve physical and mental health, and quality of life. Ethical considerations should be taken into account when practicing or recommending spiritual interventions by healthcare professionals to respect patients’ beliefs in choosing mind-body interventions.

Dr. Helen Lavretsky is a Professor of Psychiatry at the Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior at UCLA, a geriatric psychiatrist with the research interest in geriatric depression and caregiver stress, as well as complementary and alternative medicine and mind-body approaches to treatment and prevention of disorders in older adults. She is co-editor of Late-Life Mood Disorders with Martha Sajatovic and Charles Reynolds. She is a recipient of the two Career Development awards from NIMH and other prestigious research awards. Her current research include clinical and translational studies of geriatric depression and caregiver stress, as well as complementary and alternative interventions for stress reduction in older adults.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology and neuroscience articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Mindful exercise and mental health appeared first on OUPblog.

May 18, 2013

The science non-fiction of Commander Chris Hadfield’s ‘Space Oddity’

Audi now employs two generations of Spocks as spokesmen and Axe body spray hawks a space voyage sweepstakes to hormonal jocks with the promise that chicks dig astronauts. Tired of ninjas, pirates, robots, and zombies, edgy advertisers appear to have set their fad-hungry gaze on space as the current (if not final) frontier of Awesome—the somewhat-undefinable quality that high-fives our inner ten year-old. And maybe an aging generation of underfunded aerospace engineers is wise to seize the moment as a bid for relevance; after all, it was the media-savvy Comic-Con set who pitched in last summer to buy up Nikola Tesla’s old lab and convert it into a museum, spurred on by a Kickstarter Project that cashed in on the late scientist’s re-branding as Awesome.

Click here to view the embedded video.

So, to those of us who clicked on astronaut Chris Hadfield’s now-viral YouTube video of the song that he recorded in a space station, what followed was a surprise. A piano gently pined with seventh chords as we saw our slowly turning planet from orbit. Then, balding and with a speckled mustache, Hadfield appeared onscreen and sang in a boxy, thin warble, “Ground Control to Major Tom.” Hadfield’s zero-gravity performance of David Bowie’s classic “Space Oddity” appears to reach back to the lunar landing of 1969, but viewed from this moment of identity crisis in our culture’s own sense of “progress,” it does so with remarkably little preciousness or delusion. Hadfield manages to sing a wholly different relationship of humankind to its future than the Audis and Axes of the Internet would have us imagine.

The proto-glam original of “Space Oddity” may cast the singer as Major Tom, but David Bowie’s musical storyline has always been that of the alien. Hadfield stages none of Bowie’s dire theatrical camp and instead focuses on the humanness of his last five months aboard the International Space Station. The 46-year-old Canadian changes lyrics here and there, replacing the song’s inflections of sci-fi and tragedy with references to the ISS sawyer’s hatch and a simple assurance that “our commander comes down back to Earth,” revealing that the banal factuality of space needs no dressing up to seem remarkable. When he sings, “I’m floating in a most peculiar way,” there’s no trace of druggy psychedelia because we literally see him floating, sans special effects. Up there, everything is a space oddity. Hadfield understands this and is keen to share it—as is clear in the video where he giddily demonstrates to a science class back on Earth what it’s like to wring out a wet towel in space.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Little wonders like this are easy to lose track of because the media, politics, and economics have rendered space no longer the promising future that it once seemed. In fact, I’d be far from the first to acknowledge that somewhere amid the oil crises of the 1970s, the end of the Cold War, and having crossed the symbolic finish line of the millennium, the very idea of the future lost its shine.

In January 1986, I sat before a big screen TV with 20 fellow first-graders to watch the Challenger launch. Our school had primed us with a tremendous lead up to the event as a matter of pride in Christa McAuliffe—a teacher from our own little state of New Hampshire. We’d built a papier mâché space shuttle and there was cake. We didn’t really understand what happened next, but we knew it wasn’t supposed to go that way. As for culture at large, cynicism descended fast. Keith LeBlanc’s 1986 single “Major Malfunction,” for example, lays down a metallic shuffle beat and samples Reagan’s assurance of “space pulling us into the future,” pitting it against repeated clip declaring “technology works” while its music video juxtaposes the Challenger explosion with mushroom clouds.

That day might not have been the singular end of western culture’s belief in space exploration as manifest destiny, a wide-eyed and righteous progression into the endless wonder of our own inevitable fulfillment. But it surely dealt a blow—especially because around that time my classmates and I started spending our lunch break huddled around the school’s first computer, which promised that the future lay more in the infinitesimal than in the infinite.

But if Chris Hadfield’s “Space Oddity” is too maturely earnest to be labeled as Awesome, then it’s also too forward-looking to hear as nostalgic or mourning. Musicians Joe Corcoran and Emm Gryner made the instrumental backing track glossy enough to seem sonically less like post-2000 rock (where pianos and strings aim for rugged indie authenticity above shininess), and more like the neo-symphonic scores of post-2000 videogames—seemingly the last corner of pop culture as-of-yet unconquered by Instagram retro aesthetics. Hadfield’s verse about returning to Earth is no less literal than his floating; he landed yesterday, but hints at the continuation of humankind’s explorations.

Remarkably, by recording this song in space, alone amid all the unglamorous gray stuff of functional technology, he has removed the sheen of the metaphorical and made it intensely personal. The song is no longer epic, and we should be glad because given the way “epic” has been fully conscripted as a synonym of Awesome in recent years, this allows us to strip space and the future of its needless and jokey faux-bigness. Instead, through this intensely personal reflection on real time spent in real space, Chris Hadley reminds us the future’s wonder can and will exceed the facile fuzziness of memory and the inarticulate thing we call “hope.” He reminds us that whatever lies ahead is not an awesome advertisement, a hipster wisecrack, or an historical eulogy; it’s there to grasp and feel in all its realness.

S. Alexander Reed is a professor and musician. He is the author of Assimilate: A Critical History of Industrial Music (Oxford University Press, June 2013).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The science non-fiction of Commander Chris Hadfield’s ‘Space Oddity’ appeared first on OUPblog.

War and glory

The failures of leadership… the destructive power of beauty… the quest for fame… the plight of women… the brutality of war… Such themes have endured for over 2,700 years in Homer’s classic The Iliad — from the flight of Helen and Paris, to the fury of Menelaus and Agamemnon, to the fight between Hector and Achilles. We sat down with Barbara Graziosi and Anthony Verity, the writer of the introduction and translator respectively, to discuss the new Oxford World’s Classics edition of The Iliad.

How did the Ancient Greek performance tradition inform the text of The Iliad?

Click here to view the embedded video.

What can you tell us about the writer of The Iliad?

Click here to view the embedded video.

How is the anger of Achilles portrayed in the poem?

Click here to view the embedded video.

How is war, violence, and death portrayed in the poem?

Click here to view the embedded video.

Describe the translation process.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Barbara Graziosi is Professor of Classics at Durham University. She has written extensively on Homer.

Anthony Verity taught Classics in several schools in England, his last job being Master of Dulwich College. He has translated Theocritus and Pindar for Oxford World’s Classics, his OWC edition of The Illiad was published in September, and he is currently working on a version of Homer’s Odyssey. Read his previous blog post: “Who needs another translation of Homer’s Iliad?”

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics onTwitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post War and glory appeared first on OUPblog.

Clinician’s guide to DSM-5

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is a classification of all diagnoses given to patients by mental health professionals. Since the publication of the third edition in 1980, each edition has been a subject of intense interest to the general public. The current manual, DSM-5, is the first major revision since 1994.

DSM-5 is not, as sometimes claimed, “the bible of psychiatry”. It is not based on a thorough understanding of the causes of mental disorder, which remain largely unknown. Nor does it provide guidance concerning treatment. What DSM does is to allow mental health professionals to communicate with each other by listing criteria by which diagnoses can be made reliable.

When DSM-5 was in the planning stage, there was talk of radical changes, leading to a “paradigm shift”. This did not happen, as the scientific reviewers of proposals for revision insisted that major changes could not be made without very strong scientific evidence. A few changes attracted attention in the media (such as allowing a diagnosis of depression in people suffering from grief). By and large, the manual is not that different from its predecessors.

The problems with DSM-5 are the same as those affecting all earlier editions. If we do not understand what causes mental illness, it is very difficult to classify it. Unfortunately, the use of certain diagnoses is so widespread that people get the impression that categories in psychiatry are as real as hepatitis or multiple sclerosis. They are not. They are simply convenient ways of describing what clinicians see in practice. None of them have a correlation with biomarkers such as blood tests, genes, or brain imaging. They remain entirely dependent on signs and symptoms, which is all that mental health practitioners can currently observe.

The DSM system has led to an inflated prevalence of certain disorders, sometimes producing diagnostic epidemics. These problems affect some of the most common disorders in practice. Thus “major depression” is a very disparate collection of signs and symptoms that cannot be used to determine the correct treatment. Bipolar disorder is being diagnosed in patients who do not have its classical features, and has even been applied to young children. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has no definite boundaries, and is being greatly over-diagnosed, both in children and adults. Autism spectrum disorders, once considered rare, are now being seen as among the most common of all conditions that professionals see.

The real problem behind diagnostic epidemics is the failure of the DSM system to distinguish between mental disorder and normality. There is no agreed on definition of mental illness, whose scope has been steadily expanded. This trend is associated with a dangerous over-prescription of drugs that were originally developed for patients with severe and clearcut illnesses.

The DSM system can be described as flawed but necessary. Clinicians need to communicate to each other, and even a wrong diagnosis allows them to do so. However it will require many decades before we know enough about mental illness to produce a truly scientific classification.

Joel Paris is a professor of psychiatry at McGill University (Montreal, Canada), and a research associate at the SMBD-Jewish General Hospital, Montreal. He is the author of 15 books, most recently The Intelligent Clinician’s Guide to the DSM-5®, and 183 peer-reviewed scientific articles.

The OUPblog is running a series of articles on the DSM-5 in anticipation of its launch today, 18 May 2013. Read previous posts: “DSM-5 will be the last” by Edward Shorter, “The classification of mental illness” by Daniel Freeman and Jason Freeman, “Personality disorders in DSM-5″ by Donald W. Black, and “American psychiatry is morally challenged” by Michael A. Taylor.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: young woman in a conversation with a consultant or psychologist. Photo by AlexRaths, iStockphoto.

The post Clinician’s guide to DSM-5 appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers