Oxford University Press's Blog, page 939

May 31, 2013

Antiquity and perceptions of Chinese culture

What role does antiquity play in defining popular perceptions of Chinese culture? Kenneth W. Holloway confronted this issue recently with a set of bamboo manuscripts featured in the opening ceremony of the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Confucians have claimed these manuscripts while denying its relevance to the rest of early China. Excavated texts have the potential to transform our understanding of history, but we cannot force them to conform to long held intellectual frameworks.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Kenneth Holloway is Associate Professor of History and Levenson Professor of Asian Studies at Florida Atlantic University. He is the author of The Quest for Ecstatic Morality in Early China.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Antiquity and perceptions of Chinese culture appeared first on OUPblog.

World No Tobacco Day: How do we end tobacco promotion?

For the past 25 years, the World Health Organisation and its partners have marked World No Tobacco Day. This day provides an opportunity to assess the impact of the world’s leading cause of preventable death — responsible for one in ten deaths globally — and to advocate for effective action to end tobacco smoking. This year, the WHO has selected the theme of banning tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship.

Why does this matter? Some still believe that active smoking is an adult choice and that the tobacco industry should be able to promote its products in the same way as the producers of other consumer goods. Yet research has shown us that the vast majority of the world’s smokers begin using tobacco as children and that advertising influences uptake as well as continued smoking. Removing all forms of tobacco promotion is a key component of effective tobacco control. For this reason, Article 13 of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, the world’s first global public health treaty, requires the 176 jurisdictions that are currently party to the Treaty to introduce comprehensive bans.

Why does this matter? Some still believe that active smoking is an adult choice and that the tobacco industry should be able to promote its products in the same way as the producers of other consumer goods. Yet research has shown us that the vast majority of the world’s smokers begin using tobacco as children and that advertising influences uptake as well as continued smoking. Removing all forms of tobacco promotion is a key component of effective tobacco control. For this reason, Article 13 of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, the world’s first global public health treaty, requires the 176 jurisdictions that are currently party to the Treaty to introduce comprehensive bans.

What can advertising bans achieve? First, by removing advertising from television, billboards and magazines, for example, we know that the tobacco industry’s ability to deceive consumers about the attractiveness of its product and the ‘health’ benefits of particular forms of tobacco (such as low tar cigarettes or hand-rolled tobacco) is restricted. Secondly, advertising bans (including removing sports sponsorship and point of sale displays) protect children from tobacco marketing, which is important. Although the industry will claim that its marketing is aimed at adults, studies in a number of countries have demonstrated the relationship between exposure to tobacco advertising and smoking in children, with dose effects related to frequency and type of exposure. Finally, research that has examined the impact of voluntary codes to limit tobacco promotion and partial advertising bans has found these to be ineffective. There is no such thing as ‘responsible’ tobacco advertising.

Yet even in developed countries where most forms or tobacco advertising, including point of sale displays, are now banned, one pernicious form of promotion remains. This is tobacco packaging. As government action has removed the ability of the tobacco industry to spend its generous marketing budgets on traditional forms of advertising, companies such as Phillip Morris, British American Tobacco, and Japan International Tobacco have invested in increasingly innovative, attractive, and tailored (aimed at girls and young women, for example) packs. A recent systematic review found 37 studies that examined the potential impact of removing the promotion that branded packaging provides and replacing it with plain or standardised packaging. The studies in the review show that plain packaging would: reduce the appeal of smoking; increase the noticeability of health warnings and messages; and reduce the use of packaging design techniques that mislead consumers about the harmfulness of tobacco products. Some of this research was influential in persuading the Australian government to introduce plain packaging in December 2012, and despite the tobacco industry’s best efforts to derail its introduction through litigation, this policy is now under active consideration in a number of other countries.

Despite the progress made in ending tobacco promotion in some countries, there is still some way to go, particularly in low and middle income countries where smoking rates are still rising. Today just 6% of the world’s population live in countries where comprehensive tobacco advertising bans are in place. Action is needed to persuade governments who have not yet introduced restrictions — or only have partial bans in place — to end tobacco promotion in their country. A good starting place is to ensure that policymakers understand the weight of evidence underpinning Article 13 of the FCTC, including the role of tobacco packaging in promotion. The research community needs to work with advocates and policy makers to ensure that this evidence is understood and used. It has a powerful role to play in counteracting the ongoing efforts of the tobacco industry to promote a product that kills.

Linda Bauld is Professor of Health Policy at the University of Stirling. She is Deputy Editor of the journal Nicotine and Tobacco Research, Chair of Cancer Research UK’s Tobacco Advisory Group, a visiting professor at the University of Bath and Chair of the NICE Tobacco Harm Reduction Programme Development Group.

To mark this year’s WHO theme of banning tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship, the Nicotine and Tobacco Research’s Editor has selected five articles for further reading. They can be read in full and for free on the journal’s website:

Implementation and Research Priorities for FCTC Articles 13 and 16: Tobacco Advertising, Promotion, and Sponsorship and Sales to and by Minors

Perceptions of Plain and Branded Cigarette Packaging Among Norwegian Youth and Adults: A Focus Group Study

Germany SimSmoke: The Effect of Tobacco Control Policies on Future Smoking Prevalence and Smoking-Attributable Deaths in Germany

The Association Between Point-of-Sale Displays and Youth Smoking Susceptibility

The Effect of Graphic Cigarette Warning Labels on Smoking Behavior: Evidence from the Canadian Experience

Nicotine & Tobacco Research is one of the world’s few peer-reviewed journals devoted exclusively to the study of nicotine and tobacco. It aims to provide a forum for empirical findings, critical reviews, and conceptual papers on the many aspects of nicotine and tobacco, including research from the biobehavioral, neurobiological, molecular biologic, epidemiological, prevention, and treatment arenas. The journal is published by OUP on behalf of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Cigarettes. Photo by robeo, iStockphoto.

The post World No Tobacco Day: How do we end tobacco promotion? appeared first on OUPblog.

Doubting Thomas: a patron saint for scientists?

By Thomas Dixon

The story of Doubting Thomas is a wonderful philosophical parable about seeing and believing, but what exactly is the intended moral? And what light does it shed on the relationship between science and religion?

The standard view portrays Doubting Thomas as a scientific hero demanding evidence and refusing to succumb to blind faith. Richard Dawkins has popularised this version since the publication of The Selfish Gene in 1976. Last September he tweeted, “If there’s evidence, it isn’t faith. Doubting Thomas, patron saint of scientists, wanted evidence. Other disciples praised for not doing so.”

But this is not an entirely convincing interpretation either of the bible or of the nature of scientific knowledge.

In John’s gospel, the other disciples tell Thomas: “We have seen the Lord.” Thomas is not convinced: ”Unless I see in his hands the print of the nails, and place my finger in the mark of the nails, and place my hand in his side, I will not believe.” A week later Jesus appears to all the disciples, and addresses Thomas: “Put your finger here, and see my hands; and put out your hand and place it in my side; do not be faithless, but believing.” Thomas now believes, and Jesus comments: “Blessed are those who have not seen and yet believe.”

Now, remember that according to Dawkins the story is told so that we should admire not Thomas, but the other disciples, “whose faith was so strong that they did not need evidence.” What is wrong with that? Well, first of all, the other disciples believed in the resurrection not through blind faith, but because they saw the risen Jesus with their own eyes.

Dawkins is right that we are not supposed to admire Thomas’s refusal to believe, but he is wrong about the reason. Thomas’s behaviour really is a little irrational. What better basis for belief could he have had than the testimony of his most trusted friends? We all have to rely on testimony rather than first-hand experience for the vast majority of our knowledge.

Thomas’s sin was the refusal to believe reliable testimony. The English natural philosopher and theologian John Wilkins wrote about the Doubting Thomas story in the seventeenth century. Jesus’s saying ‘Blessed are those who have not seen and yet believe’ signified, for Wilkins, that it was ‘a more excellent, commendable and blessed thing for a man to yield his assent, upon such evidence as is in itself sufficient, without insisting upon more.’ The testimony of the other disciples should have been in itself sufficient for Thomas; and yet he insisted upon more.

Communal observation and testimony are central to both religion and science. Caravaggio’s The Incredulity of St Thomas (c. 1601-2) depicts a collective act of witnessing. Should we, perhaps, even think of Thomas’s finger here as a rudimentary scientific instrument? Is he making a digital measurement? Are the other disciples there to corroborate his observations? Rembrandt’s slightly later painting of an anatomy lesson (1632) can be seen as a transposition of this model to a scientific setting. In both cases, the body of an executed criminal is being probed — in the case of Rembrandt’s image, with forceps rather than just a finger — in front of a group of witnesses, and with the aim of producing knowledge.

The key point here is that these images depict acts of communal knowledge-production. Scientific knowledge, like religious belief, is produced by collaborative acts of observation which, in turn, rely on the observations, testimony and inferences of others.

Richard Dawkins suggests that Doubting Thomas should be the patron saint of scientists. In fact he is patron saint of the blind, which is perhaps more fitting. If Thomas does stand for the view that the true basis of knowledge is unaided individual sense perception, then his is indeed an unscientific world and a world of blindness — a world where, in a phrase of Galileo’s, “one wanders in vain through a dark labyrinth.” Galileo admired those who believed in the sun-centred system before the advent of the telescope: “They have by sheer force of intellect done such violence to their own senses as to prefer what reason told them over that which sense experience plainly showed them to be the case.” Blessed, you might say, are those who have not seen and yet believe.

Returning to Caravaggio’s painting, we see Thomas, his hand being taken by Christ and placed in the wound in his side. Thomas’s eyes are dark, glazed, blank; he is gazing straight ahead, not at the wound. This is indeed a depiction of a blind man – a man being led by the hand towards something he cannot see. Caravaggio seems to say that the man who seeks to base all his knowledge on individual sense experience will see nothing. In both religion and science, the most important beliefs rest on a kind of seeing that cannot be done by an individual alone, that cannot be done with unaided human eyes, and that cannot be done without belief in an unseen realm.

Dr Thomas Dixon is Senior Lecturer in History at Queen Mary, University of London and the author of Science and Religion: A Very Short Introduction, which won the BSHS Dingle Prize in 2009. You can find him on Twitter at @thomasdixon2013 .

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: Caravaggio [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons; Rembrandt [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Doubting Thomas: a patron saint for scientists? appeared first on OUPblog.

May 30, 2013

The IRS scandal and tax compliance

The IRS is under withering scrutiny for allegedly using partisan political criteria to evaluate applications for nonprofit 501(c)(4) status. All sides agree that, if true, this would constitute an unacceptable abuse of power and that it raises serious questions about the adequacy of IRS governance.

But the economic consequences have gone unexamined amidst all of the political fallout. To be specific, will the publicity about the IRS actions, and any accompanying decline in taxpayer trust in the IRS’s procedures, affect tax compliance? This is no trivial matter. Taxpayers already skirt an estimated $400 billion in tax liability—a figure that looms especially large given the $600 billion annual deficit. If noncompliance were to grow significantly, it would exacerbate our already daunting fiscal challenges.

The best available evidence suggests that the answer is probably no, unless the scandal undermines the IRS’s ability to effectively monitor and punish noncompliance. Economists posit a simple model of tax evasion: taxpayers decide whether, and how much, to cheat by comparing the expected tax saving from successful tax evasion to the costs, including penalties, of being caught. The extent of tax evasion depends on people’s perceptions of the chance of getting caught, the perceived penalty of detected evasion, and taxpayer risk aversion toward the gamble that is tax evasion. It is hard to see how the scandal, by itself, would affect any of these factors.

Some social scientists have argued that this framework misses important elements of the tax evasion decision. For example, some people may comply with their legal obligation because of a sense of civic duty, not fear of punishment. But government actions can affect citizens’ sense of obligation. Tom Tyler of Yale University argues that citizens are more likely to be law-abiding if they view legal authorities as legitimate. Margaret Levi of the University of Washington argues that some taxpayers’ behavior depends on the behavior, motivations, and intentions of the government. When citizens believe that the government will act in their interests, that its procedures are fair, and that their trust of the state and others is reciprocated, then people are more likely to become “contingent consenters” who cooperate in paying taxes even when their short-term material interest would make evasion the better option.

Though plausible, no evidence compellingly suggests that these factors have much of an effect on tax evasion. In particular, direct written appeals to taxpayer duty have no apparent effect on compliance behavior. In contrast, abundant evidence supports the theory that a higher chance of detection deters evasion significantly. Strikingly, for wages and salaries, where employer information reports and IRS computer matching make successful evasion unlikely, the noncompliance rate is just 1%; for self-employment income, where no such information reports exist, the noncompliance rate is more than 50%.

If, as the evidence suggests, evasion is constrained mostly by the threat of detection and penalty, then the IRS scandal will cause the tax gap to grow only if the uproar about the IRS results in a cutback in their ability to enforce the law effectively. If, for example, Congress slashes the IRS budget in retaliation or otherwise handcuffs the tax authorities, that could have significant, and lasting, fiscal implications.

Leonard E. Burman and Joel Slemrod are the author of Taxes in America: What Everyone Needs to Know. Leonard E. Burman is Daniel Patrick Moynihan Professor of Public Affairs at Maxwell School of Syracuse University. Joel Slemrod is Professor of Economics in the Department of Economics and the Paul W. McCracken Collegiate Professor of Business Economics and Public Policy in the Stephen M. Ross School of Business, at the University of Michigan.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image via iStockphoto.

The post The IRS scandal and tax compliance appeared first on OUPblog.

The mysteries around Christopher Marlowe

Four hundred and twenty years ago, on Wednesday 30 May 1593, Christopher Marlowe was famously killed under mysterious circumstances at the young age of 29. Test your knowledge on this enigmatic figure of history. Do you know when Marlowe was born? Who killed him and why? Find out answers to these and much more in our quiz. Good luck!

Four hundred and twenty years ago, on Wednesday 30 May 1593, Christopher Marlowe was famously killed under mysterious circumstances at the young age of 29. Test your knowledge on this enigmatic figure of history. Do you know when Marlowe was born? Who killed him and why? Find out answers to these and much more in our quiz. Good luck!

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Answers can be found by using a combination of Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (OSEO)’s post “Mysteries around Marlowe” and the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography article on Marlowe, free to view until 30 June 2013.

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (OSEO) is a major new publishing initiative from Oxford University Press. The launch content (as at September 2012) includes the complete text of more than 170 scholarly editions of material written between 1485 and 1660, including all of Shakespeare’s plays and the poetry of John Donne, opening up exciting new possibilities for research and comparison. The collection is set to grow into a massive virtual library, ultimately including the entirety of Oxford’s distinguished list of authoritative scholarly editions.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: A portrait, supposedly of Christopher Marlowe. 1585. Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The mysteries around Christopher Marlowe appeared first on OUPblog.

Hay hopes

The Telegraph Hay Festival is taking place from 23 May to 2 June 2013 on the edge of the beautiful Brecon Beacons National Park. We’re delighted to have many Oxford University Press authors participating in the Festival this year. OUPblog will be bringing you a selection of blog posts from these authors so that even if you can’t join us in Hay-on-Wye, you won’t miss out. Don’t forget you can also follow @hayfestival and view the event programme here.

Caroline Shenton will be appearing at The Telegraph Hay Festival on Sunday 2nd June 2013 at 10am to talk about The Day Parliament Burned Down More information and tickets.

By Caroline Shenton

Writing a book also means talking about it. A lot. Over the last nine months since publication, I have given around thirty talks about #parliamentburns, as the book is known on Twitter, to groups large and small, here and abroad, and in huge lecture theatres as well as at a pub, an art gallery, and in someone’s front room with a greedy labrador in attendance (actually one of my favourite venues). I’ve composed presentations of different lengths – from twenty minutes to one hour and twenty minutes – as well talks tailored to groups interested in firefighting, archives, Dickens, and Turner. I use a series of drawings, watercolours, engravings and oil paintings of the catastrophic fire at Westminster in 1834 to tell this forgotten story, and provided the lights are down and the battery in my remote control slide controller doesn’t run out (it did at the Cheltenham Festival!), the audience comes with me on an immersive tour round the greatest disaster to hit London since 1666. I’m delighted to be doing a session at the Hay Festival about this year and I have great hopes of the audience, but not perhaps in the way you might imagine.

I tell the story of how in the early evening of 16 October 1834, to the horror of bystanders, a huge ball of fire exploded through the roof of the Houses of Parliament, creating a blaze so enormous that it could be seen by the King and Queen at Windsor, and from stagecoaches on top of the South Downs. In front of hundreds of thousands of witnesses the great conflagration destroyed Parliament’s glorious old buildings and their contents. No one who witnessed the disaster would ever forget it. The events of that October day in 1834 were as shocking and significant to contemporaries as the deaths of JFK and Princess Diana were to our generation – yet today this national catastrophe is a forgotten disaster, not least because Barry and Pugin’s monumental new Palace of Westminster has obliterated all memory of its 800 year-old predecessor. In one hour I aim to relate the story of the fire as it burns through the building during a day and a night.

But the  real point is, talking about the book is not a one-way process. In the last year I’ve been amazed and delighted by the response of members of the audience who have come forward with more information about the fire at the old Palace of Westminster. Following one lecture I was shown a snuffbox carved from the surviving wood of the Painted Chamber – a wonderful survival. I had discovered in my research that such souvenirs were made from remnants of the destroyed building, and widely advertised and sold at the time, but I never imagined to see any of them intact today.

real point is, talking about the book is not a one-way process. In the last year I’ve been amazed and delighted by the response of members of the audience who have come forward with more information about the fire at the old Palace of Westminster. Following one lecture I was shown a snuffbox carved from the surviving wood of the Painted Chamber – a wonderful survival. I had discovered in my research that such souvenirs were made from remnants of the destroyed building, and widely advertised and sold at the time, but I never imagined to see any of them intact today.

After another event, this time at the Soane Museum, news of some other mementoes made from the ruins came to my attention. This time were some limestone ‘chess pieces’ created from salvaged stonework, depicting a mysterious man and woman.

People ask such interesting questions as well. Were the first steam-powered fire engines used at the scene? What would have  happened to the old Houses of Parliament if there hadn’t been a fire; would it have been restored or knocked down anyway? Where was Turner actually standing when he painted the scenes – was he in fact on the first floor of a stranger’s house, or in a boatyard shack? Can we trace where the salvaged stone was reused? Who conducted the public inquiry that followed the fire – was there a cover-up? And in a reversal of what you might expect, UK audiences nearly always want to know whether anyone was punished, while American audiences mostly want to know about what the greatest art losses were.

happened to the old Houses of Parliament if there hadn’t been a fire; would it have been restored or knocked down anyway? Where was Turner actually standing when he painted the scenes – was he in fact on the first floor of a stranger’s house, or in a boatyard shack? Can we trace where the salvaged stone was reused? Who conducted the public inquiry that followed the fire – was there a cover-up? And in a reversal of what you might expect, UK audiences nearly always want to know whether anyone was punished, while American audiences mostly want to know about what the greatest art losses were.

People have been in touch with new eyewitness accounts of the fire, and details of local Westminster residents at the time of the fire; and some friends who are architectural historians gave me a picture of the fire they had found in a print shop as a memento.

I’ve been thrilled to be offered all this new information, but now I’m setting my sights higher. My ultimate aim is to track down the stuffed body of Chance, the celebrity firedog who attended the fire and whose body was last seen in at the London Fire Brigade’s HQ in Watling Street, London in the 1880s. Now, to have an audience member come forward at Hay with a glass case containing a moth-eaten carcase of the famous Manchester terrier would be the best piece of audience participation of all…

Caroline Shenton is currently Archives Accommodation Study Director at the Parliamentary Archives in Westminster. Her book The Day Parliament Burned Down (OUP) was published in 2012. Shortlisted for the Longman-HistoryToday Prize, in February 2013 it won the inaugural Paddy Power and Total Politics Political Book of the Year Award. Caroline tweets @dustshoveller and has a blog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: courtesy of Caroline Shenton. All rights reserved.

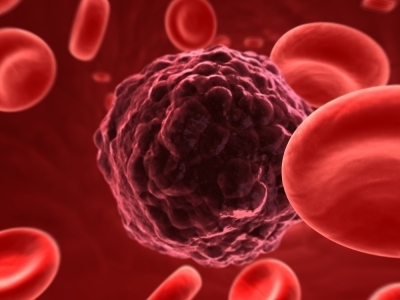

Cancer drug rationing – dare we speak its name?

I have been an oncologist for thirty years, intimately involved in patient care and in the development of novel anti-cancer therapies. Over that time I have seen the average survival for patients with advanced and metastatic colorectal cancer (my particular field of study) improve from six months without treatment, to around two years with the full panoply of currently available medicines. This has been achieved by a series of incremental steps, extending life by about six months for every increase in the complexity of treatment (from supportive care to single agent, to double agent combination, to doublet chemotherapy plus a biological agent). Although there is a relatively linear relationship between clinical outcome and the number of drugs used in combination, the cost of treatment rises exponentially.

Although drug expenditure accounts for approximately 10% of the total costs of cancer treatment, it seems to dominate the public cancer debate. Usually the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) is in the firing line for failing to approve some new drug which does not meet the incremental cost-effective criteria by which they judge all innovative medical technologies. More recently, the government’s Cancer Drug Fund, established as an election promise by David Cameron, has found itself in the headlines, mainly due to lobbyists urging the government to continue this fund.

Interestingly, oddly even, I have had a hand in the establishment of both of these outfits. I was a founding Commissioner for Health Improvement, tasked with supporting implementation of NICE policy — remember that NICE was introduced as an antidote to the postcode prescribing prevalent throughout the NHS — and I was Health Adviser to David Cameron and Andrew Lansley in the run up to the last election and supported the creation of the Cancer Drug Fund and the associated commitment to get the UK’s cancer survival figures up among the best in Europe. The initial idea around the Fund was to make anticancer drugs available for rare cancers for which the evidence base underpinning their use would be more difficult to assemble.

This all begs the question: why do cancer drugs cost so much for so relatively little benefit — months rather than years of added life? There is a mystery in this: an element of ‘what the market will bear’; an element of pricing for failure as the majority of anticancer drugs don’t make it to the clinic; an element of spiraling development costs and regulatory bureaucracy. What there is not in common with so many industries is a direct relationship between cost of manufacture and price. When patents expire and the cancer drug becomes generic, meaning that it can be manufactured by anyone with the appropriate environment and skills, the price can reduce overnight by 85%.

How might we make cancer drugs more affordable? I say ‘we’, because it will require a multisectoral approach to solve the problem. The current model of anticancer drug development may be broken and will need industry, academia, funders of research and government to work together to come up with new ways of increasing efficiency and likelihood of success. Colleagues of mine in Oxford have started to promulgate the idea of open access science and how we might apply this to developing better cancer drugs, especially in the early discovery phase, and we are considering how we might match with open access clinical trials linked to real time reporting of side effects and tumour volume.

In the interim, we need to rationalise NICE and the Cancer Drugs Fund. It would be logical to consult widely on the utility of the Fund, on how it has been used, and on its future. It seems illogical and even unfair, that cancer be considered separate from all other diseases. NICE is supposed to provide a unified means of comparing the relative value of interventions across all of medicine, so perhaps the societal debate about the affordability of new drugs should encompass all medical specialties, rather than cancer as a special case.

David Kerr is a Professor of Cancer Medicine at University of Oxford, UK and Adjunct Professor of Medicine, Weill-Cornell College of Medicine, New York, USA. He is one of the editors of Drugs in Cancer Care, a medical text in the Drugs in… series.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: cancer cell – closeup. Image by Eraxion, iStockphoto.

The post Cancer drug rationing – dare we speak its name? appeared first on OUPblog.

May 29, 2013

X-rays and science: from molecules to galaxies

We often think of x-rays strictly in terms of medical diagnosis, but in fact they have played a huge role in scientific discovery beyond medicine. Though they are part of the same electromagnetic spectrum that includes visible light, their different properties enable them to reveal phenomena that the naked eye cannot perceive. For example, x-rays have opened up our understanding of the worlds of the very small and the very large, enabling us to grasp the structure of some of the most essential molecules in living organisms. They have also spawned remarkable insights into the origin, structure, and ongoing evolution of the universe of which we are a part.

Some would say that the single most important biological discovery of the 20th century concerned the structure of DNA, which is sometimes referred to as the “master molecule” of life. In 1962, James Watson, Francis Crick, and Maurice Wilkins shared the Nobel Prize for this discovery, but much of the groundwork had been laid over the preceding decades. Perhaps the single most important technique for making inferences about DNA’s structure was x-ray crystallography, which is performed by projecting x-rays onto a crystalline solid. The resulting images make it possible to determine how its atoms are positioned relative to one another.

The father-son team of William Bragg and William Bragg developed much of the theory behind x-ray crystallography. Ironically, the elder Bragg had been the first person on the continent of Australia to use x-rays for medical purposes when he diagnosed the fracture of a bone in the younger Bragg’s arm when the boy was only 5 years old. Many years later, it would be the younger Bragg who nominated Watson, Crick, and Wilkins for their Nobel Prize. Later researchers, including Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin, used the Braggs’ technique to show that DNA had a long, threadlike structure, though neither one deduced its now well-known double-helical structure.

Rosalind Franklin was a particularly interesting figure. Franklin battled sexism throughout her life, and eventually earned her PhD at Cambridge University. During her postdoctoral work in Paris, she was able to improve on Wilkins’ techniques and produce much more precise images of DNA’s molecular structure. According to Watson, it was Franklin’s x-ray crystallographic images that made it possible for him and Crick to arrive at the double-helix model. Unfortunately, Franklin did not share in the Nobel Prize because she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer at the age of only 36 years. Nobel Prizes are not awarded posthumously, and Franklin had succumbed 5 years before the award was made.

James Watson was an American wunderkind who earned his PhD at Indiana University at only 22, while the British Francis Crick was in his mid-30s and had not yet received his PhD at the time he and Watson made their breakthrough. They were competing against other remarkable scientists, including the American Linus Pauling, whom many consider the greatest American scientist of the 20th century. Pauling is also one of only a handful of people to receive two Nobel prizes. Pauling mistakenly published a triple-helix model of DNA, leaving the field open for Watson and Crick, relying on better x-ray crystallographic data, to produce the correct double-helix model.

A black hole concept drawing by NASA. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

X-rays have also opened up our understanding of some of the largest and most extraordinary objects in the universe, up to and including the universe itself. X-rays are a particularly high-energy form of electromagnetic radiation, meaning that they are generally released by processes producing a temperature thousands of times higher than the heat of the sun. For many years, astronomers could rely only on visible light for their observations, but around 1960 the world of x-ray astronomy began to open up. This is due to the fact that cosmic x-rays are filtered out by the earth’s atmosphere, but about this time it began to be possible to put x-ray detection devices into space on rockets.

For example, in 1962, a rocket launched to assess x-ray emissions by the moon identified what became known as the first extra-solar x-ray source. Known as Scorpius X-1, it is a neutron star approximately 9,000 light years away. Its visible light emission is only 1/400 that of the dimmest star detectable in the night sky, but, at least from earth’s point of view, it is the strongest source of x-rays in the sky. Its x-ray output is approximately 60,000 times greater than the luminosity of the sun. We now believe that these tremendously energetic x-ray emissions originate as the immense gravitational pull of the neutron star draws off material from a companion star, converting much of its matter to energy.

What exactly is a neutron star? A neutron star is an incredibly dense object. It has been estimated that one containing half a million times the mass of the earth would fit into a sphere with a diameter equal to that of Brooklyn, New York. It is created by gravitational collapse following the explosion of a massive star, a so-called supernova. Most of the atomic components are released in the explosion, but the neutrons remain and collapse in on themselves, creating an extraordinarily dense, hot, and rapidly rotating object. The gravitational pull of neutron stars is so great that they bend light, in a phenomenon known as gravitational lensing.

Black holes are even more bizarre x-ray sources. The represent the final stage of the evolution of very massive stars, and it is thought that the supermassive black holes at the centers of some galaxies may have masses equivalent to billions of suns. As a result, they collapse and compress matter to an even greater extent than a neutron star, to the point that the entire mass of the earth would fit into the palm of a hand. These objects bend space-time to such an extent that even light cannot escape, and the passage of time itself ceases, in the sense that there is no longer any before or after. Such an object cannot be directly observed, and its presence is inferred based on the way it gobbles up matter.

Specifically, as matter approaches a black hole, it is accelerated to relativistic speeds near the speed of light. Once such matter reaches a certain point, known as the event horizon, it is impossible for anything to escape, and all light that reaches the horizon is absorbed, making a black hole impossible to visualize. But as matter approaches the event horizon, it is heated to an incredible degree, emitting huge quantities of x-rays. Moreover, it emits lesser quantities of energy as visible light, helping to form some of the brightest light sources in the universe. Though most of the light is blocked by intervening debris, the x-rays can travel vast distances and reach our detectors.

Wilhelm Roentgen, the German physicist who discovered X-rays in 1985, could not have imagined the immense impact this new invisible light would have on the course of science. In addition to their use in crystallography and astronomy, x-rays can also be used in microscopy, fluorescence, and spectroscopy. They have many additional applications, such as inspecting welds, producing precise three-dimensional images of objects such as violins, and scanning passengers and baggage at the airport. It is remarkable to think that, though x-rays themselves are invisible to the eye, they continue to play a huge role in revealing the world around and within us.

Richard Gunderman, MD PhD, is a Professor of Radiology, Pediatrics, Medical Education, Philosophy, Liberal Arts, and Philanthrophy at Indiana University, Indianapolis, Indiana, and winner of the 2012 Alpha Omega Alpha Robert Glaser Distinguished Teacher Award. He is the author of X-Ray Vision: The Evolution of Medical Imaging and Its Human Implications. He will be hosting a webinar on this subject on Wednesday, 29 May 2013, 3:00-4:00 p.m. Eastern.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: DNA depiction via iStockphoto.

The post X-rays and science: from molecules to galaxies appeared first on OUPblog.

Monthly etymological gleanings for May 2013

Language controlled by ruling powers?

Very much depends on whether the country has a language academy that decides what is correct and what is wrong. Even in the absence of such an organization, a committee consisting of respected scholars and politicians sometimes lays down the law. Spelling is a classic case of “ruling the language.” Once a certain norm is established, deviations in printed sources become impossible. Exceptions are rare. For instance, at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century, some American journals allowed their contributors to use “simplified” variants (liket for liked, and so forth). Other than that, languages like English, Spanish, French, and German (to mention a few) have what is called the Standard. Editors and teachers enforce it, but in oral communication people are free to go their own way, which they do. Consider the universal use of ain’t, and the war on it by the “establishment.” Sometimes the rules imposed on speakers enjoy universal support. Modern Icelandic is a case in point. Icelanders believe that they should avoid borrowings and welcome native substitutes. By contrast, no one likes English spelling (see Masha Bell’s comment on her mail). Yet the illogical rules will be upheld until some “power”changes them.

Support for small languages.

Support for small languages.

Should we welcome attempts to support languages like Welsh? I think we should. Given a reasonable number of people who speak a small language and are willing to cultivate it, allowing it to die would be silly and sinful. Here everything depends on institutional support. Schools need teachers proficient in the endangered language, books and newspapers have to be published, and scholarship in those languages will require funding. Seeing how much money the world wastes, steals, embezzles, and misuses, we should hardly count every penny when it comes to saving cultural heritage.

Capitalizing the first person pronoun in English.

John Cowan has referred to a detailed discussion of this question, but, as follows from it, the causes of capitalizing I in English still remain partly unknown. In my blog post, I cited the most common explanation, and it does not seem to have been refuted. One thing is clear (and I mentioned it): English speakers did not use a capital letter for this pronoun in order to aggrandize themselves.

The letter y.

Yes, spelling applie for apply makes sense, but y is in general a superfluous letter. Sometimes we even run into homographs: compare supply, the adverb of supple (suppl-y), and the verb supply. Among other things, I have been asked about the name of this letter and will deal with it in a special post. Some related questions are also worth discussing. But let me first get rid of multifarious devils (bogey was the hero of the previous post). Bogeyman “snotman” is a jocular extension of bogeyman “evil spirit.” All of us were children once and learned the word in its “nursery” meaning. Now we have grown up and can afford studying etymological devilry.

Engl. rye ~ German Roggen, Engl. lye ~ German Lauge.

Our correspondent is right: in Old Engl. ryge “rye,” the letter g designated what would be y in Modern English. The history of lye is less straightforward. Its Old English form was leag (with long ea). Leag was pronounced approximately leah. It shed final h, and the old diphthong ea yielded a long monophthong, which eventually became Modern Engl. i, now designated by the letter y. Thus, lye bears less resemblance to its etymon than does rye.

Rising intonation.

The rise in sentence final position in Australian English has often been discussed. It is far from clear whether the “infection” came to British English from there. Cockney may have had this intonation for centuries, and the colony was used for deporting the criminals, most of whom spoke the dialect of the London underworld. The possible Cockney base of Australian phonetics has also been the object of numerous publications, but no consensus on this matter exists.

Handsome is as handsome does.

Annie Morgan would like to know when this proverb acquired a pejorative meaning. I wonder how many speakers detect negative connotations in it. At worst (or so I think), the saying contains a mild warning: this person is handsome, but good looks do not necessarily presuppose good behavior, so be on your guard. Personal beauty and virtue may not go together. Novels about charming rakes and seductive but perfidious women have beaten this moral in us once for all (naturally, novels took their cue from life).

Dickens’s cashy face.

Yes, of course, cashy might, in some oblique way, refer to Dickens’s wealth. It is the uniqueness of the phrase that puzzles me. I have not been able to find another case of cashy face in the corpus. Therefore, whatever the journalist meant, the question remains why he used such a strange collocation. And how was it understood by the readers of the newspaper?

The history of the word enormity.

The adjective enormous, an obvious borrowing from Romance, surfaced in late Middle English with the sense reflecting its etymology (from e-, that is, ex-, and norm-) and meant “abnormal; wicked, evil, heinous.” Later its meaning was narrowed (a common case in historical semantics) to “abnormal with regard to size,” but even today enormous is not simply huge but unimaginably (“awesomely”?) big. The noun enormity followed the same route.

Spanish mono “pretty, cute.”

This is indeed a sense that owes its origin to mono “monkey.” Incidentally, in both Spanish and Portuguese mona can signify being drunk, and this sense also goes back to the monkey’s tricks. Monkeys do not touch alcohol but are often made responsible for people’s idiocy. Similarly, in German we find the idiom sich einen Affen kaufen, literally, “to buy oneself a monkey” = “to be drunk.”

German Bengel ~ Danish bengel ~ Swedish bängel, etc. “rogue, scoundrel.”

The origin of these words is more complicated than it seems. Their often proclaimed connection with a sound imitative verb meaning “strike” (compare Engl. bang) needn’t be taken for granted. Those  interested in details will find a useful discussion in Olav Ahlbäck’s article “Bängel” (Nysvenska studier 59, 1979, 179-188; in Swedish). An interesting English word is bang-, as in bangtail and bangs. Its connection with bang! and to bang (and bengel) has not been clarified to everybody’s satisfaction.

interested in details will find a useful discussion in Olav Ahlbäck’s article “Bängel” (Nysvenska studier 59, 1979, 179-188; in Swedish). An interesting English word is bang-, as in bangtail and bangs. Its connection with bang! and to bang (and bengel) has not been clarified to everybody’s satisfaction.

Engl. thief ~ Lithuanian vagis.

These words are not related, and nothing connects them except their meaning. The putative Baltic cognates of thief are certain verbs, mentioned in the previous posts.

“This is all there is to my tale.”

I finished a recent post with this sentence and added: “As Chesterton may have said and perhaps even did.” Stephen Goranson informs me that Chesterton never said so. Alas! I conjured up Chesterton’s ghost because Pater Brown stories sometimes end with the humble conclusion to the effect that the solution turned out to be easy.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Caricature of Chesterton, by James Montgomery Flagg, 1914. The Well-Knowns. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Monthly etymological gleanings for May 2013 appeared first on OUPblog.

60th anniversary of the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II

On 2 June 1953 Queen Elizabeth II took her coronation oath in a ceremony at Westminster Abbey. Since her accession on 6 February 1952 aged 25, following the death of her father King George VI, the day had been planned in great detail. Our Who’s Who editors take a look at the day, and test your knowledge of the people who made it a historical event to remember.

The Earl Marshal, the 16th Duke of Norfolk, was responsible for organising the Coronation and the ceremony was directed by the Garter Principal King of Arms, Hon. Sir George Bellew. A procession of 250 representatives from Crown, Church and State entered the Abbey, joining over 8000 guests, including prime ministers and heads of state from around the Commonwealth.

The Queen’s white satin dress, exquisitely embroidered and encrusted with jewels, was designed by Sir Norman Hartnell. The Coronation service began at 11.15 a.m. and lasted almost three hours. Music included Sir William Walton’s ‘Orb and Sceptre’ Coronation March. The Archbishop of Canterbury, Geoffrey Fisher (later Baron Fisher of Lambeth), concluded the ceremony by placing St Edward’s Crown on the Queen’s head.

Three million people lined the streets of London to catch a glimpse of the new monarch in the golden state coach. During the two-hour procession from the Abbey to Buckingham Palace Queen Salote of Tonga won the hearts of the crowds by refusing to raise the roof of her carriage despite the heavy rainfall.

An estimated 27 million people in Britain watched the ceremony on television and 11 million listened on the radio. The BBC’s televising of the Coronation, produced and directed by Peter Dimmock, was a breakthrough in the history of outside broadcasting. The commentator was Richard Dimbleby.

After an appearance by the Queen on the balcony of Buckingham Palace, guests were treated to Coronation Chicken, a dish newly created by Constance Spry who also advised on floral arrangements. Official photographs were taken by Sir Cecil Beaton, and the artist Feliks Topolski was commissioned to produce a 30 metre frieze as a permanent record of the occasion. Terence Cuneo created a painting of the Coronation ceremony, and James Gunn painted a state portrait of the Queen in Coronation robes.

The 60th anniversary of the Queen’s Coronation will be marked with a service of celebration at Westminster Abbey on 4 June 2013. The Bishop of London will give a public lecture, Vivat Regina, looking at the historical significance of the Coronation, and a photographic exhibition at the Abbey’s Chapter House has opened in partnership with Mark Getty’s Getty Images. Buckingham Palace will hold a four-day Coronation Festival in July, bringing together over 200 companies who hold Royal Warrants of Appointment.

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Who’s Who is the essential directory of the noteworthy and influential in every area of public life, published worldwide, and written by the entrants themselves. Who’s Who 2013 includes autobiographical information on over 34,000 influential people from all walks of life. The 165th edition includes a foreword by Arianna Huffington on ways technology is rapidly transforming the media. Please note that the Who’s Who articles in this blog post will be freely accessible until the 20th June 2013, after which you can access through a subscription. You can follow Who’s Who on Twitter @ukwhoswho.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Photo of Queen Elizabeth II in Royal Dress. February 1953, Associated Press. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post 60th anniversary of the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers