Oxford University Press's Blog, page 936

June 9, 2013

Kinky Boots

Young Charlie Price (Stark Sands) of Northampton, England, has just unwillingly inherited his family’s struggling shoe factory. His girlfriend wants him to sell it to a condominium developer and move to London, where they can live a properly upwardly mobile life. Torn between his family obligations and his desire to do something other than run a shoe factory, Charlie meets a drag queen named Lola (born Simon; played by Billy Porter), who happens to break a heel and mention that he would do anything for a better-made pair of fabulous boots to wear during drag performances. Will the two team up and save Charlie’s struggling shoe factory by serving a small but loyal drag-queen niche market? Will Charlie realize that his girlfriend Nic (Celina Carvajal) is a materialistic jerk who doesn’t truly appreciate him for who he is? Will he end up meeting a much nicer girl with better values? Will Lola/Simon teach lots of people about what it means to be a real man in the process? Will these two very different men become the best of best buddies? Will everyone learn something valuable about themselves and others by the curtain call?

Puh-lease. You have to ask?

Photo credit: Bruce Glikas

There are all sorts of reasons to dislike Kinky Boots. It has a totally predictable plot. Its messages about love and acceptance are well meaning, if heavy-handed and sort of trite. For all its gender commentary, it’s ultimately a very traditional bromance that relegates even the most talented women to the sidelines. It has some seriously wooden scenes, forced lines, and dumb lyrics. It is yet another musical based on a movie. It’s pretty fluffy and forgettable, all told.All of these reasons help explain why I was so genuinely stunned by how much I enjoyed Kinky Boots. It’s flawed, sure, whatever. It’s also charming, cute, and just so, so, so enjoyable. I saw an early preview and found that the cast was already quite strong. I hope the show brings Porter the attention he deserves. What’s more, though, is how completely representative Kinky Boots is of its fabulous, lovable, wonderful creators (Harvey Fierstein and Cyndi Lauper). You never catch a glimpse of either of them during the show, and yet they — and especially Lauper — steal every single scene.

I set out to hate the musical because, let’s face it, I am cynical and oppositional, especially when it comes to rock musicals, which this sort of, kind of is. And yet, by intermission, Kinky Boots had turned my sour mood around. By the curtain call, I was surreptitiously wiping tears from my eyes.

This is not to say that I don’t stand by my criticisms of the show, and especially my concerns about what it — and Broadway in general — says of late about gender dynamics. For the stage musical’s traditional embrace of difference, and its advocacy of social acceptance –a lways a good thing — I find myself increasingly concerned that such overarching messages are compensating for a serious shift in focus toward heteronormative male characters. Lola may be in drag, and Charlie may be a guileless guy from the sticks, but the show is almost entirely about the ways they assert their normative masculinity. Of the two women prominently featured in the show, one is the above mentioned materialistic social climber — the stereotypical evil witch, as gentle is her treatment, here. The other is a truly goofy, unbelievably fantastic factory worker named Lauren (Annaleigh Ashford), who has eyes for Charlie, impeccable comic timing, and some of the best stage presence I’ve seen in a long time. I wanted more of her, but alas, both Lauren and Nic serve primarily to help the male leads learn valuable lessons about themselves and others. I’d let this go, but there are so many other shows on Broadway about male bonding at the expense of female characters that I can only imagine Ethel Merman and Mary Martin spinning in their graves.

Yet all my concerns about on-stage erasure are matched by an equally strong tug of proto-feminist nostalgia. I love Harvey Fierstein, sure, and could hear his gravelly, reassuring voice behind many of the best lines in the show. But the even louder voice was that of Cyndi Lauper, whose squinty eyes, wacky outfits, and squeaky, nasal, Queens-bred voice insinuated itself into just about every song her characters sang.

The airwaves of my childhood were dominated by Michael Jackson, and Prince, and Madonna — and the Thompson Twins and Howard Jones and INXS and the Human League and… you get the idea. But really, in a lot of ways, the weirdest and most wonderfully reassuring presence was that of Lauper. Sure, she dressed in unbelievably bizarre fashions and her hair was dazzlingly strange. Yeah, her sharp, nasal Queens accent could cut glass. and she hung out with wrestlers who put their beards in lots of small ponytails. But Lauper was just so…unusual, even at a time when being unusual was the key to celebrity. Her star paled in comparison with Madonna’s, with whom she was in most direct competition. And yet in a lot of ways, Lauper’s messages about gender acceptance and remaining true to oneself regardless of the consequences resonated in ways that Madonna’s did not. Madonna was the brilliant marketing machine; she was a force of nature, but she was dead serious about it. Lauper — like most teenagers — was funnier, more impulsive, less carefully crafted. After all, she just wanted to have fun — and not get bullied or beat up or grounded in the process. I loved her. I never shaved my head or liked wrestlers or wore a garbage dress, but I understood her, liked her, accepted her. And on some level, even as a kid, I appreciated that, were we to meet, she would have accepted me, too.

And therein lies the rub. I enjoyed Kinky Boots because I could hear Lauper throughout it. And for all my concerns about the erasure of women on the musical stage, Lauper’s voice came through loud and clear. It always has, I guess. I was awfully glad to hear it again, after all these years, and I suspect that the show will do well for a number of reasons. It’s fun, it’s endearing, it’s moving, and it has a strong, independent, thoroughly bizarre woman behind it. Take that, heteronormative bromance! Go forth, Kinky Boots! Charm the masses, and in the process, please let your composer and lyricist conquer.

Elizabeth L. Wollman is Assistant Professor of Music at Baruch College in New York City, and author of Hard Times: The Adult Musical in 1970s New York City and The Theater Will Rock: A History of the Rock Musical, from Hair to Hedwig. She also contributes to the Show Showdown blog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Kinky Boots appeared first on OUPblog.

June 8, 2013

Ocean of history

On 8 June—a day known around the world as World Oceans Day—we should take a few moments to consider the history as well as the plight of our watery globe. The earth is mostly covered by water, not land, and that water is largely responsible for all forms of human and non-human life. The oceans are instrumental to everything; they form the basis of the earth’s water cycle, provide sustenance to much of humanity, and serve as a barometer of the mounting climate crisis. Humans have not been kind to the oceans during the past century. Industrial pollution as well as the historically unprecedented harvesting of world fisheries represents only two in a long list of severe threats to our oceans’ health. Despite these challenges, which are threatening in every conceivable way, we also have an opportunity to think about oceans from a different vantage point.

I tend to think historically—call it an occupational hazard. And my historical thinking for the past ten years has focused on the Pacific Ocean, that vast stretch of water covering one-third of the earth’s surface. It’s not an expanse of blue on the map. Instead, the Pacific is dotted by tens of thousands of islands and occupied by a dizzying complexity of humankind. And it’s been that way for a very long time. Because of this human past and ecological significance, it’s important to think historically about the Pacific as well as other oceans.

And yet, to imagine oceans as possessing rich histories may run counter to some peoples’ sense of traditional historical and geographic space. The geography upon which our histories usually take place—nations, regions, and localities—has fixed borders encompassing land, and we almost exclusively write about the peoples’ history in relation to that landed space. Landed geography connects nations and people (their ideas, commodities, politics, etc.) across distances near and far. But until recently historians have expressed little interest in imagining the ways that oceans connect people and polities. Oceans, it would seem, hardly register on historians’ mental maps of places that truly matter because we so often imagine the sea as a flight from history and humanity.

The Pacific holds many distinct and overlapping histories. For instance, during the early 1800s the Pacific waterscape witnessed one of history’s greatest convergences of humankind, as well as their commodities, microbes, ideas, and thirst for marketable commodities. Indigenous islanders and mainlanders discovered Europeans, Americans, and Asians, and recognized in them terrible new forces of historical change. Natives were subjected to the deadly viral and bacterial loads carried by these foreigners. Diseases swept through indigenous communities again and again, waves of depopulation documented by Spanish, British, French, American, and native chroniclers. Foreigners also created new seas of commerce that soon criss-crossed the “Great Ocean,” bringing the Pacific into the trade patterns that define this period of world history. The Pacific, in this way, entered and influenced the global history of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

The impact of the global convergence was not limited to people. Those mammals that lived in the Pacific’s great and ceaseless currents—whales, sea otters, seals, and more—faced an assault without parallel in history. In a matter of decades numerous marine mammal species neared extinction due to the value of their skins, hides, and blubber. Offshore islands once filled with fur seals and their deafening roars were described as eerily quiet by the 1820s. The history of this “great hunt” is one of brutal, industrial-scale violence, vividly captured in the logbooks and diaries of sea captains and common sailors.

The world’s oceans contain innumerable histories. Some of them were written and published while others were transmitted orally from person to person. Some focus on the advance of empires around the globe. Others recount the resistance to such empires, especially during the past five centuries in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian oceans. The new oceanic history incorporates many themes and subjects: social affairs, environmental conditions, mass migrations, forced diasporas, and cultural exchanges. These histories can be global in scale and encyclopedic in content, or they can tell the story of an individual vessel on a particular voyage to a certain locality. The local informs the global, and vice versa. The oceans present us with a whole new perspective on history, and World Oceans Day is an excellent reason to delve into this literature.

David Igler is Professor of History at the University of California, Irvine. He is the author of The Great Ocean: Pacific Worlds from Captain Cook to the Gold Rush (Oxford, 2013) among other books. He is currently on sabbatical and living in Madrid with his family, where he is researching a new book and enjoying Spanish wines.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Guam Sea Ocean Water Rocks Rocky Sky Clouds. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Ocean of history appeared first on OUPblog.

The origin and text of The Book of Common Prayer

Despite its controversial history, the Book of Common Prayer is an influential religious text and one of the most compelling works of English literature. How has this document retained its relevancy even after numerous revisions? What can it teach us about British history and the English language? We spoke with Brian Cummings, editor of the Oxford World’s Classics edition of The Book of Common Prayer, about the importance of this text.

Why did you want release a new edition of this book?

Click here to view the embedded video.

How did you choose the three texts used in your edition?

Click here to view the embedded video.

Why is the text considered a part of literature?

Click here to view the embedded video.

Can you tell us about the origins of the book?

Click here to view the embedded video.

How was the book incorporated into daily life?

Click here to view the embedded video.

How has the book influenced literature and language?

Click here to view the embedded video.

Brian Cummings received his BA at Cambridge University, where he also took his PhD under the supervision of the poet Geoffrey Hill and the church historian Eamon Duffy. He was previously a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge before moving to Sussex, and, from October 2012, the University of York. He was a British Academy Exchange Fellow at the Huntington Library, California, in 2007 and held a three-year Major Research Fellowship with the Leverhulme Trust from 2009 to 2012. He is the editor of the Oxford World’s Classics edition of The Book of Common Prayer.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics onTwitter, Facebook, and the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The origin and text of The Book of Common Prayer appeared first on OUPblog.

June 7, 2013

Paul Ortiz on oral history

Justin Dunnavant (Left) SPOHP graduate research coordinator and Isaiah Branton (Right), Alachua County historian and descendant of enslaved African Americans brought to the Gainesville area in 1854 from South Carolina, discusses historical photos of his family to be digitized by SPOHP staff.

By Caitlin Tyler-Richards

As regular readers might have guessed, the Oral History Review staff has spent the last few months obsessing over oral history’s bright, digital future. However, now that special issue 40.1, Oral History in the Digital Age, is out, we’re taking a break — just a break! — to recall the oral history projects that run on something other than tagging and metadata. To that end, we were lucky enough to catch up with Professor Paul Ortiz, director of the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program (SPOHP) at the University of Florida. Founded by Dr. Samuel Proctor in 1967, SPOHP is one of the longest standing institutions in the discipline of oral and, as you will learn in this podcast, responsible for a variety of fantastic projects. Dr. Ortiz also gives us a sneak peak of SPOHP’s 2013-2014 Public Program line up. Surprise, surprise, it sounds fantastic.

[See post to listen to audio]

Or download the podcast directly.

Professor Paul Ortiz serves as Director of the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program and associate professor of history at the University of Florida. He is an affiliated faculty member of Latin American Studies, African American Studies and Women’s Studies at UF. His publications include the book Emancipation Betrayed, a history of the Black Freedom struggle in Florida, and Remembering Jim Crow: African Americans Tell About Life in the Segregated South. Dr. Ortiz is the recipient of the Harry T. and Harriett V. Moore Book Prize, the Lillian Smith Book Prize and the Carey McWilliams Book Award. He is on the international editorial board of Palgrave Studies in Oral History.

The Oral History Review, published by the Oral History Association, is the U.S. journal of record for the theory and practice of oral history. Its primary mission is to explore the nature and significance of oral history and advance understanding of the field among scholars, educators, practitioners, and the general public. Follow them on Twitter at @oralhistreview, like them on Facebook, or follow the latest OUPblog posts to preview, learn, connect, discover, and study oral history.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Paul Ortiz on oral history appeared first on OUPblog.

The beauty pageant and British society

Next week sees the culmination of the 2013 search for Miss England. Aspiring beauty queens from across the nation will compete for the title and the chance to contend for the Miss World crown in front of a global audience of one billion television viewers.

Studies of the beauty contest in Britain have tended to focused on the controversy surrounding these pageants and their status as, according to some feminist activists and scholars, “celebrations of the traditional female road to success.” Without wishing to downplay the significance of resistance to the beauty contest, I think that we need to focus on the origins and development of these events in Britain in order to fully appreciate their cultural significance.

Originally conceived in the mid-nineteenth century by the American showman P.T. Barnum, the first recognisable beauty contest took place in Delaware in 1880. A panel of expert judges (including Thomas Edison) was assembled to select the winner of the Miss United States title, which was created to promote the resort of Rehoboth Beach outside of the usual holiday season. The 1921 Miss America Pageant introduced the bathing costume as a wardrobe stable for competitors, casting aside earlier fears about the need for more modest attire. In the 1920s and 1930s, such contests became widespread in Britain and were deployed to promote a variety of places and products.

Cultural commentators and journalists in interwar Britain labelled the period as a time of cultural change, embodied by factory girls that now looked (according to the writer J.B. Priestley) “like actresses.” The appearance and lifestyle of young women seemed to undergo a rapid transformation in these years. Those who worked found that they could afford to purchase mass-produced fashions, beauty products, and cosmetics. This change in appearance was coupled with access to new forms of leisure at the cinema and dancehall. Although changing fashions and an apparent obsession with Hollywood movies were criticised in the press, young women in interwar Britain were provided with a certain amount of freedom to manipulate their appearance and follow the latest trends. Girls from across the social spectrum now had the means to style themselves as a beauty contestant.

Although the Daily Mirror created its first beauty competition in 1908, these features appeared infrequently in the popular press because photographs were difficult (and expensive) to reproduce until the interwar years. This changed by 1930 when images of attractive young women and beauty queens had become “a necessary element of a popular newspaper.” While the Daily Mirror’s 1908 competition had been judged solely by a panel of experts, the ability to print photographs of participants ensured that the readers of the newspaper could also begin to play a role in choosing each beauty queen. Anecdotal evidence from the Cotton Queen Quest (launched by the Manchester Daily Dispatch in 1930) suggests that this voting system may have helped to drive additional newspaper sales amongst friends, colleagues, and relatives keen to see their candidate advance to the final round of the competition. In a period of intense competition between popular newspapers, the beauty contest was a popular feature that seems to have boosted newspaper sales.

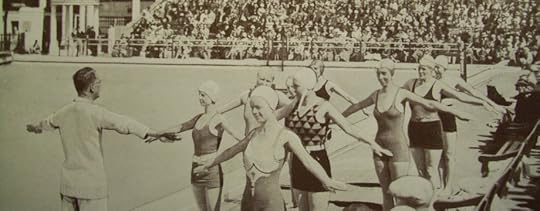

A group of novice swimmers are shown the basics in front of a packed crowd at the Open-Air Bath in Blackpool c. 1934. Image courtesy of Blackpool Archive. Used with permission.

The beauty contest flourished in interwar Britain thanks to a new focus on the healthy body and the benefits of outdoor leisure pursuits. As Ina Zweiniger-Bargielowska describes, physical exercise became a “mass phenomenon” in this period and seaside resorts responded to the vogue by constructing large open-air bathing facilities. Venues like the Open-Air Bath (1923) in Blackpool were capable of holding thousands of swimmers and spectators. Designed as sites to celebrate and cultivate a healthy body, these bathing facilities provided a natural home for the beauty contest. Pageants continued to be a regular feature at seaside swimming pools into the 1960s with new titles emerging such as Miss Great Britain, crowned at the extravagant Super Swimming Stadium in Morecambe from 1945. Without such venues, it seems unlikely that the beauty pageant would have been able to develop quite so rapidly in Britain in these years. The birth of the British beauty contest was reliant on the high level of investment and development at seaside resorts in the first part of the twentieth century.

The American origins of the beauty contest might suggest that these events were mere cultural imports like the jazz record or MGM film. While it’s easy to spot the similarities between British and American pageants, there are also important differences between each competition. British Pathé newsreels of competitions from this period highlight the clear distinctions in the staging and format of interwar beauty titles ranging from the Radio Queen, to the Queen of the English Riviera. The influence of local traditions, in particular, cannot be downplayed. The clothing and pageantry used in the grand final of the Cotton Queen competition, which operated between 1930 and 1939, was heavily influenced by British festival traditions like the May Queen.

The emergence of the beauty contest in interwar Britain demonstrates why it deserves further critical attention. The competition casts revealing light onto the popular press, gender, and leisure in the interwar years. We need to think carefully about how and why pageants are shaped by the context of their creation to truly appreciate what these events can tell us about Britain’s cultural and social history.

Dr Rebecca Conway received her PhD from the University of Manchester in 2012. She has previously taught at the University of Manchester and Sheffield Hallam University. Her article on the Cotton Queen Contest in 1930s Britain was recently published in Twentieth Century British History.

Twentieth Century British History covers the variety of British history in the twentieth century in all its aspects. It links the many different and specialized branches of historical scholarship with work in political science and related disciplines. The journal seeks to transcend traditional disciplinary boundaries, in order to foster the study of patterns of change and continuity across the twentieth century.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The beauty pageant and British society appeared first on OUPblog.

What’s the future of seamount ecosystems?

Tomorrow is World Oceans Day. To celebrate, the author of Marine Biology: A Very Short Introduction, Philip Mladenov, has written this piece on seamount fisheries.

By Philip Mladenov

Seamounts are distinctive and dramatic features of ocean basins. They are typically extinct volcanoes that rise abruptly above the surrounding deep-ocean floor but do not reach the surface of the ocean. The Global Ocean contains some 100,000 or so seamounts that rise at least 1,000 metres above the ocean floor.

Seamounts represent a very special kind of biological hotspot in the deep ocean. A prolific group of suspension feeding animals dominate the summit and flanks of seamounts, creating dense thicket-like communities comprising cold water stony corals, sea fans, black corals, and sponges that create habitat for a host of other animals including dense aggregations of fish. Many of the corals associated with seamounts show extreme longevity. For example, a type of black coral, Leiopathes, sampled from a seamount in the Pacific Ocean, was shown using radiocarbon dating to be about 4,200 years of age, making it one of the world’s longest living animals.

Seamounts support a great diversity of fish species; the latest census reveals close to 800 species have been recorded living around seamounts. In the 1960s deep sea trawling vessels looking for new stocks of fish began to trawl seamounts and discovered large aggregations of commercially important species. This triggered the creation of new deep-ocean fisheries focused on seamounts. Heavily built bottom trawls are towed from the summit down the flanks of seamounts to capture the fish. Commercial fish species that are targeted include orange roughy, oreos, alfonsinos, grenadiers, and toothfish. These fish are not generally permanent residents of seamounts, but aggregate at seamounts at certain times of the year to spawn, to feed on squid and small fishes, or simply to rest. They are very slow-growing and long-lived and mature at a late age, and thus have a low reproductive potential. A good example of this is the orange roughy, which is known to live for more than a hundred years and reaches maturity at around thirty years of age, with the females producing relatively small numbers of eggs. Such a life history is typical of many deep-ocean fish species.

Seamount fisheries have often been described as mining operations rather than sustainable fisheries. They typically collapse within a few years of the start of fishing and the trawlers then move on to other unexploited seamounts to maintain the fishery. The recovery of localised fisheries will inevitably be very slow, if at all, because of the low reproductive potential of these deep-ocean fish species.

The destruction of fish stocks is not the only concern associated with seamount fishing. The trawling of seamounts causes extensive damage to the fragile coral communities, with the trawls bringing up not only fish, but large numbers of corals and other benthic animals associated with the corals. The intensity of trawling on seamounts can be very high, with many hundreds to thousands of trawls often carried out on the same seamount over time. Tens of tons of coral can be brought up in a single trawl and in one new seamount fishery it was estimated that almost one-third of the total catch consisted of coral by-catch. Comparisons of “fished” and “unfished” seamounts have clearly shown the extent of habitat damage and loss of species diversity brought about by trawl fishing, with the dense coral habitats reduced to rubble over much of the area investigated.

Not surprisingly, seamount-based fisheries have become very controversial. An increasing number of countries have begun to close some of the seamounts present in their exclusive economic zones (EEZs) to fishing. Unfortunately, most seamounts exist in areas beyond national jurisdiction which makes it very difficult to regulate fishing activities on them, although some efforts are underway to establish international treaties to better manage and protect seamount ecosystems.

It appears that the future for seamount ecosystems lies in a delicate balance between protecting some from fishing altogether while allowing fishing on others under some form of regulation. What sort of balance is achieved remains to be seen in the face of declining fish stocks globally versus an unrelenting growing world demand for fish protein. Let’s hope that legislators, fisheries managers, and marine conservationists can work together to ensure that a good proportion of these remarkable seamount ecosystems will be preserved in an intact state as part of a more general effort to sustainably manage our ocean resources.

Philip V. Mladenov is the Director of Seven Seas Consulting Ltd and Chief Executive of the Fertiliser Association of New Zealand. He has more than 35 years of professional experience in marine biological research, teaching, and exploration. He is the author of Marine Biology: A Very Short Introduction and some 80 scientific papers and a broad range of popular articles, consulting reports, and government reviews.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only environmental and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: By NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The post What’s the future of seamount ecosystems? appeared first on OUPblog.

June 6, 2013

Think spirituality is easy? Think again…

The modern idea of spirituality—divorced from religious tradition, dependent on a personal choice of creed, centered on feeling good and avoiding stress—easily invites criticism or even contempt. Many see it as an evasion of religious truth and moral responsibility, a narcissistic choose-your-own-at-the-mall self-indulgence that has nothing to do with serious religious, ethical, or political life.

I beg to differ. Of course there are many for whom spirituality is just what the critics accuse it of being. But this hardly settles the matter, for there are also many religious traditionalists who are sanctimonious hypocrites, many political liberals who are narrow-minded, and many self-styled ethical people who blissfully ignore their own failings.

Thus the question is not “What is spirituality at its worst?” but rather “Is there at the heart of spirituality a powerful, redemptive, and transformative idea?”

I believe there is, one that is simply expressed but often excruciatingly hard to put into practice. The idea is this: our lives will be far happier, in an enduring and deep way, and we will be a lot more fun to be around, if we seek to live by certain virtues. To the extent that we choose to be mindful, accepting, grateful, compassionate, and loving, our own contentment will grow and our interpersonal behavior will be increasingly caring, respectful, and just.

A quick glance at these virtues should make anyone who thinks spirituality is easy think again. Each time we face a life choice, cultivate one habit or another, or find ourselves in a morally confusing and painful situation the virtues come into play. We have to decide whether we can accept disappointment without obsessing over not getting what we so richly deserve; try to understand the experience of people who bore or frustrate us; take the time and attention to examine the contents of our own mind rather than act out of fear or rage; and look deeply into our society’s fundamental structures to how whether our personal lives reflect vast and impersonal forms of injustice.

If we focus on one particular spiritual virtue—compassion—we will see that while the spiritual life is tied neither to a literal reading of scripture nor religious authority, it is still far from a walk in the park designed for the lazy.

Compassion may be understood as both an emotional openness to the suffering of others and an active response which seeks to lessen that suffering, and can be found in religious tradition and contemporary spiritual teachings. It is a Mahayana Buddhist ideal (the Bodhisattva seeks to end the suffering of all sentient beings). God in the Hebrew Bible (Deut: 4:31) and Jesus in the Christian (Matt: 14:14) are described as compassionate. The term resonates with virtually all contemporary eclectic and non-denominational teachers.

Sometimes compassion is relatively easy. If we encounter a good person whose suffering is not his fault and is easily remedied (take care of him for an afternoon, offer a hug, give a small amount of money), then compassion may flow easily.

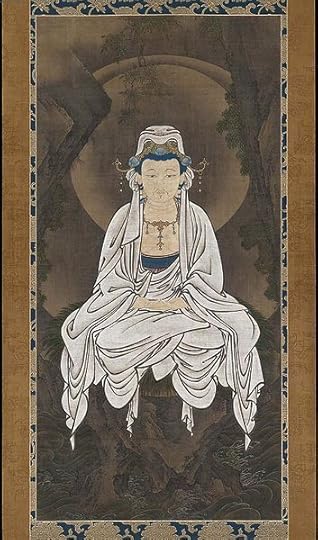

Kannon, Bodhisattva of Compassion

But think of Steve, who is always overspending: here he is again, desperately needing cash. And at the same time I am facing my own serious money troubles (family illness, stolen car). Now compassion may give way to impatience or irritation. “What about me?” I will think; or “For God’s sake, stop creating your own troubles.”

What if the suffering we encounter is part of the endless round of misery that accosts any well-informed person in today’s information overload society? Famine in Sudan, tornadoes in Missouri, pollution induced lung disease in China—and that could be just a single website on any given morning. Here we might develop what psychologist Kaetha Weingarten calls “common shock”—physical and emotional distress caused by witnessing the pain of others. We numb out and retreat, thinking “I just don’t want to hear about it.”

Here is the most difficult setting: can we have compassion for the perpetrators of crimes as well as their victims? After the Boston Marathon bombing, could we think of the killers as human beings marked by enormous emotional and moral disorientation, lacking the gift of being able to have an empathic connection to the innocent strangers they meant to kill? Can we think of cruel, selfish people as deserving of happiness? Can we, as Dante asked, have compassion for the damned?

To be compassionate even when we are needy or suffering requires that we observe our own distress without using it as an excuse to feel disdain for all those who “don’t really suffer like I do.” Dealing with common shock requires a vigilant awareness not only of all the terrible things happening in the world but of the effect of our knowledge of those things on our own minds and bodies. It requires the humility and self-awareness to admit “I simply cannot take in any more information now,” the faith that life is worthwhile even with all the suffering in the world, and the far-sightedness to see that despite all their pain human beings are more than the sum of their woes.

And the ruthless dictators, drug lords, and smiling CEOs who pollute? Don’t they deserve to be hated? Yet compassion asks us to recognize everyone’s suffering—even that of people who act very badly. The spiritual task here includes admitting our own moral weaknesses so that we can see what we have in common with the guilty; and also developing a moral clarity that allows us to act caringly against injustice without needing to be motivated by hatred.

Finally, we need to be open not only to other people’s suffering but also to their own understanding of their lives, to what we have to learn from those we would help as much as what we have to teach them. “Compassion,” insists Catholic priest Gregory Bolye, who spent decades intervening in Los Angeles gang violence, “is not a relationship between the healer and the wounded. It’s a covenant between equals.” Anglican Archbishop Rowan William’s suggests that this covenantal relationship requires a loving attention which allows other people to develop, choose freely, and come to a better, truer life by their own energies. The great temptation, says Williams, is seeking to have the last word, to control what the other says and how they live. This may be relatively easy if the person is an innocent victim. The more they are complicit in their suffering (an addict, say), or a victimizer rather than a victim, the more difficult it becomes.

Thus, true compassion might well take a whole lifetime to get good at it, let alone master. And this is true for all the other spiritual virtues, which always require attention, energy, and a willingness to let go of old habits and attachments. Each day, every moment, I am invited to choose love over hate, gratitude over bitterness, confidence in my connection to people and the world over frightened isolation.

In this light, then, spirituality is not a relaxed or cheapened version of traditional faith, or an escape from social life, but a demanding and in some ways heightened version of both religion and social engagement.

Professor of Philosophy (WPI) Roger S. Gottlieb’s most recent book is the Nautilus Book Award-winning Spirituality: What it Is and Why it Matters. You can read the Introduction on his website.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Kano Motonobu, ”White-robed Kannon, Bodhisattva of Compassion”, c. first half of the 16th century. Hanging scroll. Ink, color and gold on silk. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Think spirituality is easy? Think again… appeared first on OUPblog.

Five reasons to watch the Tony Awards on Sunday

The Tony Awards is consistently the lowest-rated broadcast of all televised entertainment awards shows, which helps explain why it is also the most awesome. I’m not being snide, here—either about the teeny spectatorship or about the awesomeness. As to the former point, here’s some perspective: The 2012 Academy Awards ceremony was watched by 39.3 million people, while the 2012 Tony Awards ceremony was watched by six million people. If you, like me, have a partner who enjoys watching late-night reruns of the mid-1990s tv series Sliders (which, your partner has probably repeatedly pointed out, starred Broadway’s own Cleavant Derricks post-Dreamgirls and pre-Brooklyn), you might think of it this way: it would take at least six parallel universes’ worth of Tony viewers to even come even close to kicking one universe’s worth of Oscar viewers’ butts from here to Schubert Alley.

But this brings me to the latter point: who would want to? I bet Cleavant Derricks wouldn’t, and I certainly wouldn’t, either. The Academy Awards can have their adoring masses, their overwhelming press coverage, their endless search for an emcee that doesn’t suck or win ratings by hitting below the belt. I’ll take the Tony ceremony anytime, in any universe. Because so few people watch it, the Tony telecast consistently feels more friendly, inclusive, and unscripted than your typical awards show. Returning emcee Neil Patrick Harris is dashing, talented, and both wickedly snarky and classy at the same time. Tony presenters and recipients all seem realer and more approachable. Acceptance speeches are often looser and less rehearsed. Long before it was acceptable anywhere else on television, gay men and lesbians who won Tony Awards would kiss, embrace, and publicly declare their love for their partners in full view of the television cameras, and God, and everyone. For all the positive changes afoot in this country, you still can’t say that much about the Oscars.

While Sliders has been off the air for a good decade now, I nevertheless suspect that Cleavant Derricks will probably not be making a surprise visit to the Tony Awards this year. I like to think that he’ll be watching from home, eating snacks, and perhaps trading Broadway war stories with his old Sliders co-star and recent Seminar alum Jerry O’Connell. But fear not—there are plenty of reasons to tune in to the ceremony anyway. Here are a few of the things I’m looking most forward to seeing:

(1) The Kinky Boots and Matilda Showdown

Allow me to be blunt. Bring It On and A Christmas Story might’ve been great fun, but neither one of them has a snowflake’s chance in hell of winning the Tony for Best Musical. The contest here is between Matilda and Kinky Boots, and while Matilda is the critical favorite, I’m not convinced it’ll take the award as easily as all that. In some ways, Matilda is the better production; it’s beautiful, innovative, and compellingly directed — an exceptional adaptation of an exceptional Roald Dahl children’s book. Also, if it comes down to which cast has the more convincing and consistent British accents, Matilda will take the prize in a heartbeat. But Matilda has its problems. It’s a darker, chillier show with somewhat more tepid word of mouth; it has lousy sound design; its score is not consistently interesting; and its orchestrations and vocal arrangements tend to overcompensate for some of the weaker songs. For all its kinks, Kinky Boots is a more conventional show in a lot of ways, but it tugs more adeptly at the heartstrings….and it’s been selling better. If there is an upset, it’ll be because Kinky Boots made more members of the Tony committee get all mushy and weepy than Matilda did.

It’s entirely possible that both musicals will come away with some big wins. Bertie Carvel—Miss Trunchbull in Matilda—is favored to win in the Best Actor category, but Billy Porter—Lola in Kinky Boots—has a devoted following and a nuanced grasp of his character, and he looks better in a dress. Both Matilda and Kinky Boots have strong books, and while I am always happy to see Harvey Fierstein give an acceptance speech, I suspect that Dennis Kelly will win Best Book of a Musical for the grace and fluidity with which he adapted the Dahl story.

(2) The Award for Best Score

Cyndi Lauper’s catchy, upbeat score for Kinky Boots is favored to win this category, and I am hoping it does, not only because I firmly believe that the world needs more Lauper, but also because I’d love to see a woman win a Tony for best music and lyrics, for once. Finally, I’ve been listening to both cast recordings a lot in the past few days, and I’ve come to the conclusion that the score for Kinky Boots is more well-conceived, memorable, and interesting than Tim Minchin’s for Matilda.

Then again, the late, lamented Hands on a Hardbody muddies this category a bit. Hardbody, with a score by Phish’s Trey Anastasio and Amanda Green, had a promising run at the La Jolla Playhouse in 2012, but just couldn’t find an audience when it landed on Broadway. Lacking in Broadway glitz, the show focused on average people, and featured a score steeped in carefully-wrought, rootsy, bluesy, folksy Americana. An upset in this category wouldn’t be an enormous surprise.

(3) Everything Related to Pippin

I enjoyed both Kinky Boots and Matilda, but the best Broadway musical I’ve seen all year was Pippin, by a mile, on a unicycle. I can’t wait to see an excerpt from it during the Awards broadcast, and I hope that it wins oodles of awards. It’s a shoo-in for some: As much as I loved the weird and wonderful Annaleigh Ashford in Kinky Boots, I suspect that Andrea Martin will run away with the Tony for Featured Actress in a Musical. Even if she weren’t as sublime in the role of Berthe as she is, there should be some kind of special award given to any person over the age of sixty who can strip down to a leotard and rock a trapeze as expertly as Martin does during her Act I show-stopper.

I also expect Pippin to win for Best Musical Revival, but the icing on the cake, at least for me, would be if Diane Paulus were to win the Tony for Best Director of a Musical. I mean no disrespect to Matthew Warchus, whose direction for Matilda is certainly award-worthy in its own right. But Paulus is a consistently interesting and hard-working director whose ability to re-envision and reinvent Pippin while keeping it solidly rooted in its Bob Fosse past is absolutely ingenious.

(4) Choreography

I can’t dance for the life of me, and I know shamefully little about dance as an object of study, but still, I know what I like, and I know what is starting to seem stale. I was impressed with Jerry Mitchell’s choreography for Kinky Boots and with Chet Walker’s careful reinvention of Fosse’s signature moves for Pippin. I did not see Bring It On, but can only imagine that Andy Blankenbuehler had its cast members sailing gracefully and frequently through the air on a regular basis. And while the Angry Teen Dancing that Bill T. Jones introduced in Spring Awakening and that Stephen Hoggett referenced in American Idiot didn’t work for me at all in Matilda, I nevertheless give Peter Darling major props for managing to teach an enormous, alternating cast of small children how to dance in lockstep. May the best man win.

(5) Best Lighting Design of a Musical

Okay, look, I know that this might not strike you as quite as compelling an award category as, say, Best Musical, but damn if this is not the category I’ve been thinking the most about. Know why? Check out the list of nominees:

Kenneth Posner, Kinky Boots

Kenneth Posner, Pippin

Kenneth Posner, Cinderella

Hugh Vanstone, Matilda the Musical

Do you see this? Think of the consequences here. If Vanstone beats out the competition, it could be utterly soul-crushing for Posner. Then again, I am not convinced that Posner will feel much better about things if he wins. Will he feel like the cards were stacked against Vanstone, and that the whole thing was thus not a fair fight to begin with? If he wins against himself for one particular show, will he be plagued with concerns as to why he didn’t win for the two other shows? Does he need the number of a good therapist? Do you now understand why the battle between Vanstone and Posner has been keeping me up nights?

To sum up then: I’m always eager for a good Tony Awards Ceremony, and I just can’t wait to watch Neil Patrick Harris emcee the ones coming up on Sunday. Join me and the rest of the teeny, tiny Tony viewing audience, won’t you? Don’t worry—there will be room on Cleavant Derricks’ couch, and ample snacks, for all of us.

Elizabeth L. Wollman is Assistant Professor of Music at Baruch College in New York City, and author of Hard Times: The Adult Musical in 1970s New York City and The Theater Will Rock: A History of the Rock Musical, from Hair to Hedwig. She also contributes to the Show Showdown blog. Read her previous blog posts on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Kinky Boots logo from kinkybootsthemusical.com used for the purposes of illustration. (2) Pippin the Musical logo from pippinthemusical.com used for the purposes of illustration.

The post Five reasons to watch the Tony Awards on Sunday appeared first on OUPblog.

Oh Mother, where art thou? Mass strandings of pilot whales

Biologists since Aristotle have puzzled over the reasons for mass strandings of whales and dolphins, in which large groups of up to several hundred individuals drive themselves up onto a beach. To date, efforts to understand mass strandings have largely focused on the role of presumably causal environmental factors, such as climatic events, bathymetric features or geomagnetic topography. But while these studies provide valuable information on the spatial and temporal variation of strandings, they give little insight into the social mechanisms that compels the whales to follow their counterparts to an almost certain death (at least without human intervention).

So how can we go further in our understanding of these enigmatic events? We believe that deciphering the relationship of the whales and their behavior at the time immediately before and during the stranding is the key. Indeed, social behavior appears to play a critical role in these events as suggested by several accounts of group cohesion during mass strandings; the most striking example of this being the intentional restranding of whales after being refloated during rescue efforts. Yet, previous attempts to describe mass stranding have largely failed to consider these social and behavioral aspects.

That’s where our own interests in mass stranding began. Our idea was to define a testable framework in which we could investigate how social relationships play into the dynamics of the strandings. Our starting point was a long-standing hypothesis regarding the reason for strandings, in which “care-giving behaviors” are mediated by family relationships. In this scenario, the stranding of one or a few whales, because of sickness or some kind of disorientation, triggers a chain reaction in which other healthy individuals are drawn into the shallows in an effort to support their family members. We draw two predictions from this scenario: first, that the whales in a stranding event should all be related to each other through a single ancestral female or matriarch. Second, that close relatives, especially mothers and calves, should be found in close proximity to each other when they end up on the beach during a stranding event.

Long-finned pilot whale spyhopping in Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Canada.

To test these assumptions, we were fortunate to have access to a unique collection of genetic samples from long-finned pilot whales that stranded in New Zealand and Tasmania, two renowned hotspots for mass strandings. Long-finned pilot whales were the perfect candidates for this study as they are the most common species to strand “en masse” worldwide. Compelling evidence also indicates that in this species, neither males nor females disperse from the group into which they were born (a community structure also found in killer whales, but otherwise thought to be rare in mammals), suggesting the critical importance of kinship bonds in their social life.Over 400 genetic samples were used to describe the kinship of individual long-finned pilot whales involved in 12 different mass strandings. Our investigation revealed that stranded groups are not necessarily members of a single extended family, which challenges the notion that mass strandings are driven primarily by kinship-based behavior. To test the second prediction, we needed to assess whether the individuals found near each other when strandings occur were kin related. To do so, we were lucky enough to have the position of whales stranded on the shore for two large mass strandings. To our surprise, no correlation was found between spatial distribution and kinship. Even mothers and nursing calves were not necessarily together when the whales drove themselves up onto the shore, and in many cases no identifiable mother of stranded unweaned calves was found among the beached whales. We called them the “missing mothers”. We believe that several scenarios could account for this lack of spatial cohesion, including the disruption of social bonds among kin before the actual strandings. It is even possible that the separation of related whales might actually be a contributing factor in the strandings.

Whatever the exact reason for this pattern, the results of this study have important implications for rescue efforts aimed at “refloating” stranded whales. Often, stranded calves are refloated with the nearest mature females, under the assumption that this is the mother. Well-intentioned rescuers hope that refloating a mother and calf together will prevent re-stranding. Unfortunately, the nearest female might not be the mother of the calf. Our results caution against making rescue decisions based only on these assumptions as the refloating of a juvenile and unrelated female could increase the tendency to restrand after rescue, as those individuals seek their still-stranded kin.

Many questions remain unanswered. For instance, where are the “missing mothers”? To answer this, we should make sure that genetic samples are collected from all whales involved in future mass strandings, including from those individuals who do eventually make it back to sea. We also need to know more about the genetic relationship among groups in the open ocean, for comparison to the composition of stranded groups. It seems likely that some form of social disruption takes place prior to strandings, but it remains unknown whether this is simple a consequence of the stranding or is actually a causal force, perhaps due to competitive or even aggressive interactions between multiple social groups.

Marc Oremus is a marine mammal biologist that earned his PhD at the University of Auckland, working on the population and social structure of several species of dolphins. Most of his work is based on a combination of molecular and demographic approaches; he is a member of the South Pacific Whale Research Consortium and IUCN Cetacean Specialist Group. Marc Oremus and C. Scott Baker are co-authors of the paper ‘Genetic Evidence of Multiple Matrilines and Spatial Disruption of Kinship Bonds in Mass Strandings of Long-finned Pilot Whales, Globicephala melas’, which appears in the Journal of Heredity.

The Journal of Heredity covers organismal genetics: conservation genetics of endangered species, population structure and phylogeography, molecular evolution and speciation, molecular genetics of disease resistance in plants and animals, genetic biodiversity and relevant computer programs. The journal is published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Genetic Association.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only earth and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Long-finned pilot whale spyhopping in Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Canada. Photo by Barney Moss [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Oh Mother, where art thou? Mass strandings of pilot whales appeared first on OUPblog.

June 5, 2013

Where no kiss has gone before

I grew up with Star Trek. When I was 10, I helped my mom put together an intricate scale model of the USS Enterprise (NCC-1701, if you’re curious). I knew that LeVar Burton could tell me about a warp core before I knew that he would read me a children’s book, and I knew that Klingon was a learnable language long before I had ever heard of human languages like Tagalog or Swahili. So, imagine my surprise when, in the course of discussing the new film Star Trek Into Darkness with some astute colleagues, I found out that the original Star Trek television series had not one, but two, fascinating connections to my work as assistant editor of the African American Studies Center.

Both stories involve the actress Nichelle Nichols, whose trailblazing work as Lieutenant Uhura, the USS Enterprise’s chief communications officer, in the original Star Trek series has been widely lauded as an important step forward for both women and African Americans in the media. Real-life astronaut Mae Jemison, who guest-starred as a transporter operator in an episode of the later Star Trek: The Next Generation series, has directly acknowledged the influence of Lt. Uhura’s character on her choice of career, and Nichols even had a role in bringing minority and female astronauts to NASA in the 1980s.

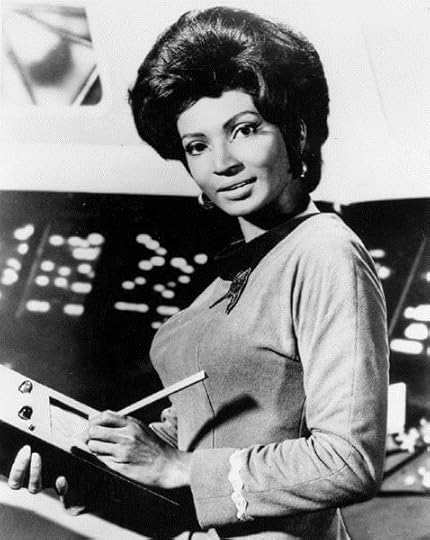

Nichelle Nichols as Lt. Uhura in the original Star Trek series. (Photo courtesy of NASA.)

The first anecdote dates to 22 November 1968, when American television audiences were treated to a particularly far-fetched episode of Star Trek entitled “Plato’s Stepchildren.” Now, the details of the show’s plot sound fairly ridiculous, even to a Trekker like me, and I will spare you their description here for fear that you won’t be able to take the rest of this post seriously. Toward the end of the episode, though, something historic occurs: Captain Kirk (played by William Shatner) and Lt. Uhura engage in a surprisingly passionate kiss. The two are not romantically linked otherwise, and the kiss is the result of alien mind control tactics, but these details are of little concern. For many people, this moment represents the instance of the first interracial kiss on television. NBC executives were concerned about how advertisers, affiliates, and audiences might react to the kiss, and they insisted that the scene be reshot without it. Shatner deliberately crossed his eyes for every new take, however, and the show’s producers decided to move forward with the scene as it had originally been shot. Audience reaction to the episode, as measured by letters sent to NBC, was nearly universally positive.

Some have argued that this was not in fact American television’s first interracial kiss, but the debate is largely semantic. Star Trek’s kiss was without a doubt a very early example of passionate interracial physical contact on television, and the show’s progressive agenda clearly anticipated a shift in cultural mores so complete that we wouldn’t bat an eye at a similar scene today.

Click here to view the embedded video.

This famous kiss might never have occurred, however, if it hadn’t been for a second incredible story that involves the intercession of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. himself. In 1967, as the first season of Star Trek was coming to a close, Nichols was ready to leave the show in order to focus on a Broadway career. After handing her letter of resignation to series creator Gene Roddenberry on a Friday afternoon, Nichols attended a fundraiser in Beverly Hills where she met Dr. King, who introduced himself as Nichols’s “greatest fan” and described in detail how his entire family made time to watch the show every week. When Nichols began to explain that she was in fact leaving the show, Dr. King stopped her mid-sentence to insist that she stay. He praised the show for its inclusive vision of the future of humanity, and underlined the significance of the fact that she played a smart African American officer with a vital role in the command structure of the USS Enterprise. If Nichols were to leave, she would simply be giving up on the incredible progress she had made.

Nichols agonized over Dr. King’s words all weekend, but resolved to return to Roddenberry’s office on Monday to take back her resignation letter. Roddenberry had already torn it up.

While these anecdotes might pass as mere trivia for some, I think that they serve as a stark reminder of just how different American popular culture looked only a few decades ago. It’s worth stating that, while Dr. King saw the promise inherent in Lt. Uhura’s character, he didn’t live to see the kiss that indicated that social barriers to equality were continuing to fall.

Was the original Star Trek ahead of its time? Cancelled after three seasons, the series was never a ratings success and certainly didn’t resonate with a wide range of television viewers when it originally aired. The fact that the show spawned a successful media franchise that has only grown more expansive in recent years suggests, however, that the show’s progressive vision contained a fundamental wisdom capable of inspiring sci-fi fans and the general public alike. Nichelle Nichols and Martin Luther King Jr. understood the power of this vision 45 years ago, and the continued presence of Star Trek in our lives today seems to be evidence that Gene Roddenberry’s hopes for humanity were not misplaced.

Tim Allen is an Assistant Editor for the Oxford African American Studies Center. You can follow him on twitter @timDallen.

The Oxford African American Studies Center combines the authority of carefully edited reference works with sophisticated technology to create the most comprehensive collection of scholarship available online to focus on the lives and events which have shaped African American and African history and culture. It provides students, scholars and librarians with more than 10,000 articles by top scholars in the field.

Subscribe to the OUPBlog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Where no kiss has gone before appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers