Oxford University Press's Blog, page 932

June 22, 2013

The History of the World: Nazis attack the USSR (‘Operation Barbarossa’)

22 June 1941

The following is a brief extract from The History of the World: Sixth Edition by J.M. Roberts and O.A. Westad.

In December 1940 planning began for a German invasion of the Soviet Union.

By that winter, the USSR had made further gains in the west, apparently with an eye to securing a glacis against a future German attack. A war against Finland gave her important strategic areas. The Baltic republics of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia were swallowed in 1940. Bessarabia, which Romania had taken from Russia in 1918, was now taken back, together with the northern Bukovina. In the last case, Stalin was going beyond tsarist boundaries. The German decision to attack the USSR arose in part because of disagreements about the future direction of Soviet expansion: Germany sought to keep the USSR away from the Balkans and the Straits. It was also aimed at demonstrating, by a quick overthrow of the Soviet Union, that further British fighting was pointless. But there was also a deep personal element in the decision. Hitler had always sincerely and fanatically detested Bolshevism and maintained that the Slavs, a racially inferior group in his mind, should provide Germans with living space and raw materials in the east. His was a last, perverted vision of the old struggle of the Teuton to impose European civilization on the Slav east. Many Germans responded to such a theme. It was to justify more appalling atrocities than any earlier crusading myth.

1941, Operation Barbarossa: Germans inspecting Russian planes. The plane in the front is a Yakovlev UT-1 and the one in the back is a Polikarpov I-16. (c) Copyright Public Domain via WikiCommons.

In a brief spring campaign, which provided an overture to the coming clash of titans, the Germans overran Yugoslavia and Greece (with the second of which Italian forces had been unhappily engaged since October 1940). Once again British arms were driven from the mainland of Europe. Crete, too, was taken by a spectacular German airborne assault. Now all was ready for ‘Barbarossa’, as the great onslaught on the USSR was named, after the medieval emperor who had led the Third Crusade (and had been drowned in the course of it).

The attack was launched on 22 June 1941 and had huge early successes. Vast numbers of prisoners were taken and the Soviet armies fell back hundreds of miles.

The German advance guard came within a few miles of entering Moscow… But that margin was not quite eliminated and by Christmas the first successful Red Army counter-attacks had announced that in fact Germany was pinned down.

Reprinted from THE HISTORY OF THE WORLD: Sixth Edition by J.M. Roberts and O.A. Westad with permission from Oxford University Press, Inc. Copyright © 2013 by O.A. Westad.

J. M. Roberts CBE died in 2003. He was Warden at Merton College, Oxford University, until his retirement and is widely considered one of the leading historians of his era. He is also renowned as the author and presenter of the BBC TV series ‘The Triumph of the West’ (1985). Odd Arne Westad edited the sixth edition of The History of the World. He is Professor of International History at the London School of Economics. He has published fifteen books on modern and contemporary international history, among them ‘The Global Cold War,’ which won the Bancroft Prize.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The History of the World: Nazis attack the USSR (‘Operation Barbarossa’) appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe History of the World: Napoleon defeated at WaterlooThe History of the World: President Kennedy and the moon landingThe History of the World: Israel becomes a state

Related StoriesThe History of the World: Napoleon defeated at WaterlooThe History of the World: President Kennedy and the moon landingThe History of the World: Israel becomes a state

June 21, 2013

OHR signing off (temporarily!)

Dear readers, the time has come for the Oral History Review (OHR) social media team to say so long for now. We’ve had a fantastic time bringing you the latest and greatest on scholarship in oral history and its sister fields. However, all sorts of summer adventures are calling our names, so we’re taking a brief hiatus from the world wide web. In fact, as you are reading this, I am on my way to Nigeria for two months!

Managing editor Troy Reeves will lurk around Twitter and Facebook for a few weeks, until he succumbs to the allure of Madison sunshine — which any Wisconsinite will tell you is an elusive blessing that must be enjoyed whenever possible. We will both return in mid-August with all new podcasts and witty twitter banter. We even have a few new social media surprises in store!

To keep up on oral history news while we’re gone, we heartily recommend you stalk the following people/organizations:

@douglasaboyd, Oral History Reviews’s esteemed digital initiatives editor.

@UWMadArchives, which in addition to tweeting about the best university in the universe, shares a new oral history website every week.

@OUPAcademic, a sincere suggestion, I promise! They tweet out their own and other publications’ articles on a myriad of always-intriguing topics.

@SamuelJRedman, UMass faculty member consistently tweeting on oral history and public history.

@FionaCosson, social historian and creator of The Oral History Noticeboard, a must for any UK oral historians.

Please leave additional suggestions in the comments below. We’ll see you in August!

Caitlin Tyler-Richards is the editorial/media assistant at the Oral History Review. When not sharing profound witticisms at @OralHistReview, Caitlin pursues a PhD in African History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her research revolves around the intersection of West African history, literature and identity construction, as well as a fledgling interest in digital humanities. Before coming to Madison, Caitlin worked for the Lannan Center for Poetics and Social Practice at Georgetown University.

The Oral History Review, published by the Oral History Association, is the U.S. journal of record for the theory and practice of oral history. Its primary mission is to explore the nature and significance of oral history and advance understanding of the field among scholars, educators, practitioners, and the general public. Follow them on Twitter at @oralhistreview, like them on Facebook, or follow the latest OUPblog posts to preview, learn, connect, discover, and study oral history.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: The back of Three Kids Standing on a Dock Wrapped in Towels looking out over a Lake in the Beautiful North Woods of Wisconsin. © Richard McGowan via iStockphoto.

The post OHR signing off (temporarily!) appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOnline resources for oral historyOnline resources for oral history - EnclosurePaul Ortiz on oral history - Enclosure

Related StoriesOnline resources for oral historyOnline resources for oral history - EnclosurePaul Ortiz on oral history - Enclosure

The end of ownership

Is there such a thing as a “used” MP3?

That was the question before the United States District Court for Southern New York earlier this Spring, when Capitol Records sued the tech firm ReDigi for providing consumers with an online marketplace to “sell” their unwanted audio files to other music fans.

ReDigi only allowed its users to upload and transfer files they had lawfully purchased through iTunes—you couldn’t rip your dad’s Led Zep CD and start selling bootleg MP3s by the dozen—and the company claimed that its technology ensured that the file was scrubbed from the users’ computer once it was sold to someone else. In essence, users could not have their cake and eat it too.

Image credit: Photo by Dennis Tang, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

At the core of the case was a key precept of American copyright—the first sale doctrine. This tenet gives consumers broad latitude to do what they please with a work once they’ve purchased it. Dan Brown can’t come into your house and harass you for using The Da Vinci Code to prop up a chair with one short leg, nor can he prevent you from loaning the book to a friend.

The District Court had to determine whether this policy applies in the digital world, where copies can be made at virtually no marginal cost and successive copies are generally as good as the original. In his ruling, Judge Richard J. Sullivan decided that the same rules could not possibly work for MP3s as for books or CDs.

The ReDigi case raises some thorny issues, but they are by no means new to the Internet or MP3s. Copyright interests have always hated “secondary markets” for used books, music, and movies, and they have long lobbied for greater control over their products. In 1906, when the US Congress first grappled with the question of how to regulate the new recording industry, lobbyists for music publishers beseeched lawmakers to forbid people from sharing music with each other. Most alarmingly, churches were buying one set of sheet music for their choirs and then loaning it to other churches—thus denying the publisher of an additional sale.

Congressmen were skeptical, though. Buying a piece of sheet music did not imply a license with the publisher, allowing only the purchaser to use the product in specified ways. Rep. John C. Chaney, a Republican from Indiana, asked a lobbyist if music publishers really believed that “the property itself does not carry the right to use it.” The answer was unequivocal. “That is the point,” the lobbyist replied. “You have stated it better than I could do it.”

Congress declined to heed the industry’s cries in 1906, but the issue of how consumers may use copyrighted works has cropped up and again. In the 1930s some record companies placed labels on their discs that said they were for “home use only”—not for playing on the radio. The courts rejected this restriction and sided with broadcasters. In the early 1980s, the music industry successfully lobbied Congress to pass the Record Rental Amendment, ensuring that a Blockbuster-like store for renting music would never emerge.

Hollywood, of course, had no love for its products being copied either. Movie studios had already tried to snuff out the VCR by fighting Sony all the way to the Supreme Court. Yet the Court ruled in the 1984 decision Sony v. Universal that consumers had the right to tape TV shows and movies on a noncommercial basis.

Today, we see a renewed attack on the rights of consumers by big business. Overly zealous regulation means that consumers are essentially barred from “unlocking” a cell phone, or severing the device from its original wireless carrier. Critics warn that such restrictions not only limit the rights of consumers but threaten to stifle old-fashioned tinkering and innovation. It is as if Ford told customers that they can’t pop the hood of their car and mess around its inner workings (which is how the world got NASCAR, incidentally).

How far should a phone company’s power extend into our personal lives when we buy one of their products? When you buy a phone or an MP3, is it really yours—or has a company just loaned it to you with a laundry list of stipulations and provisos? The age of cloud computing is upon us, and soon most of our books, movies, and musics might have no material form. We may discover that buying something no longer means owning it in any meaningful sense—and our stuff isn’t really ours anymore.

Alex Sayf Cummings is an assistant professor of History at Georgia State University, and co-editor of the blog Tropics of Meta. His book Democracy of Sound: Music Piracy and the Remaking of American Copyright in the Twentieth Century was recently published by Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The end of ownership appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMusic to surf byUniversity as a portfolio investment: part-time work isn’t just about beer moneyThe search for ‘folk music’ in art music

Related StoriesMusic to surf byUniversity as a portfolio investment: part-time work isn’t just about beer moneyThe search for ‘folk music’ in art music

When is a question a question?

By Russell Stannard

Is there such a thing as a Higgs boson? To find out, one builds the Large Hadron Collider. That is how science normally progresses: one poses a question, and then carries out the appropriate experiment to find the answer.

But the more far-reaching discoveries come not from answering such questions. Rather they come from discovering that some questions, although they seem to be perfectly reasonable, are in fact is not meaningful. Such instances reveal a fundamental flaw in one’s thinking, and herald the need for a radically new perspective.

Relativity theory offers several examples. Take the famous Michelson Morley experiment. The motivation behind this was the recognition that light is made up of electromagnetic waves. Waves, such as sound and water waves, require a medium. Thus light (so the argument went) needed a medium; it was named the aether. Light passes through the empty space between the sun and the earth, so the aether must fill all of space. A very reasonable question arises: In its journey round the Sun, how fast is the Earth moving relative to the aether? The aforementioned experiment revealed no movement. There was no aether; electromagnetic waves do not require a medium.

Closer examination of the behaviour of light then leads into Einstein’s revolutionary Special Theory of Relativity. This is concerned with the effects on space and time of uniform motion. One of the consequences of this is that a mission controller at Houston, observing a high speed space ship passing by, concludes that time on the space ship is going more slowly than his own. The astronaut’s clock is lagging behind his. However, because the motion is relative, the astronaut has an equal right to use the theory to conclude that time on Earth is going slow, and the controller’s clock is the one that is lagging. But surely they can’t both be lagging behind each other, can they? Which one (if either) is really going slow? A perfectly reasonable question. Except that it is not. It assumes that there is some kind of absolute time against which the clocks can be compared. But there is none. The word ‘time’ is meaningful only in the context of it being related to a particular observer with a well-defined motion relative to the phenomenon being observed. There is the astronaut’s time, and there is the controller’s time, but there is no THE time.

Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity goes a stage further to incorporate the effects on space and time of gravity. It provides us with our understanding of the Universe as a whole. As is well known, the Universe began with a Big Bang. So, what caused the Big Bang? Again a perfectly legitimate question to ask. Or is it? According to a widely held belief, the Big Bang saw not only the coming into existence of the contents of the universe but also the coming into existence of space and of time. There was no time before the Big Bang. Cause comes before the effect. Any cause of the Big Bang must have come before it. But where the Big Bang is concerned, there is no before. Hence it is meaningless to ask about its cause.

So much for relativity theory. How about quantum theory? We have seen how light travels through space as a wave. But when it reaches its destination, and gives up its energy on impact, it switches over to being a particle (called a photon). This so-called wave-particle duality affects everything — electrons, protons, atoms, molecules. Travelling through space they act as waves, but in their interactions with matter they behave like particles. But how can something be both a spread-out wave and at the same time, a tiny localised particle. Is an electron really a particle, or really a wave? Again, it sounds a perfectly reasonable question to ask.

It was Niels Bohr who claimed that it was nothing of the sort. According to his Copenhagen Interpretation of quantum physics, we have to stop asking all questions that begin “What is…?” Science does not answer such questions. All we can meaningfully talk about are our observations of the world. One either observes the electron to be travelling through space, in which case one uses the word “wave”, or one observes it interacting, in which case one uses the word “particle”. One can’t be doing both at the same time, so there is no call to use both words at the same time. Thus, the wave/particle paradox is solved.

It used to be thought that the job of science was to describe the world. One has to look at it, and experiment on it, in order to find out what kind of world it is. But having made the observations, what one writes down in the physics text-books is a description of the world as it is whether or not one is still observing it. However, according to this interpretation of what is going on, one has done nothing of the kind. All one’s questioning — even the legitimate questioning — has revealed nothing whatsoever about the world as it is in itself, only what it is like to observe that world.

Russell Stannard is Emeritus Professor of Physics at the Open University, UK. He is the author of Relativity: A Very Short Introduction. His other recent books include The End of Discovery, and Science and Belief: The Big Issues.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: ?? by Jérôme Paniel [Creative Commons licence] via Wikimedia Commons.

The post When is a question a question? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesVery Short Film competition: we have a winner!Medical Law: A Very, Very, Very, Very Short IntroductionForcible feeding and the Cat and Mouse Act: one hundred years on

Related StoriesVery Short Film competition: we have a winner!Medical Law: A Very, Very, Very, Very Short IntroductionForcible feeding and the Cat and Mouse Act: one hundred years on

June 20, 2013

Religious, political, spiritual—something in common after all?

Many people think it’s a great idea: we can have all the benefits of religion…without religion. We’ll call it “spirituality” and in choosing it we will have unlimited freedom to adopt this or that ritual, these or those beliefs, to meditate or pray or do yoga, to admire (equally) inspiring Hindu gurus, breathtakingly calm Buddhist meditation teachers, selfless priests who work against gang violence, wise old rabbis, and Native American shamans—not to mention figures who belong to no faith whatsoever. We’ll get the calm of one tradition, the reverence of another and the benefits of just those prayers, yoga poses, and meditations that feel comfortable.

As spiritual seekers we ask: What feels good to me? We do not ask: What is true? Who is right? To whom or what do I owe obedience?

Ironically, this outlook has aroused critics on both the ‘right’ and the ‘left.’ From traditional religion, the idea that individuals could or should choose the truth for themselves is a direct violation of orthodoxy’s claim to possess the inside story on the universe’s ultimate reality. Spirituality’s orientation to (in Robert Wuthnow’s telling phrase) seek rather than dwell seems to signal a frivolous, arrogant, pretentious attitude. “Who are you to decide?” religious orthodoxy asks angrily. “It is God and scripture that are the authorities, not your individual, weak, and often sinful self.”

From the political left “spirituality” appears to be a glossy, earth-toned, natural fiber, self-interested consumerism with a New Age music soundtrack. Where is concern with other people’s calm or contentment? Where is awareness of the social structures which allow the spiritual seeker to choose among teachers and practices while a billion people go to bed hungry every night, victims of imperialist or jihadist wars abound, and industrial civilization eliminates a species every ten minutes?

As is almost always the case in highly charged cultural conflicts, both sets of critics have a point, but these criticisms are also far from being the whole story. Let us—to vastly oversimplify a form of life that has been around for at least 2000 years and arisen in every human culture—think of spirituality as the attempt to live by the virtues of awareness, acceptance, gratitude, compassion, and love. This attempt is motivated by the belief that only these virtues can bring real, lasting, happiness. And that without these virtues personal conduct and society as a whole are doomed to frustration, greed, and injustice.

The first thing to notice is that the standard social ego, tied to desire, self-concern, fear and arrogance, will perceive spiritual virtues through its own distorted lenses. It will seek personal contentment while avoiding the hard work of overcoming old habits; think meditative calm can be achieved without examining the attachments which provoke a restless mind; be inspired by nature but not question its own environmental behavior. It is here that the charge—from both left and right—of self-oriented superficiality rings true. It is also the case that such spirituality always proves to be self-defeating. The contentment spirituality offers is not that of the standard ego, but of a self dramatically remade by commitment to practice spiritual virtues.

Pavilion of Harmony, Chinese University of Hong Kong

But the inability to take one’s stated goals seriously is widely shared among the human race, as easily found among traditional religious believers and committed social justice workers as within the ranks of spiritual types. How many Christians truly seek to follow Jesus’s teaching about wealth (shun it), retribution (“turn the other cheek”), or religious pride (definitely not for the Christian)? How many social critics pursue their political goals with close-mindedness, arrogance, or careerism?

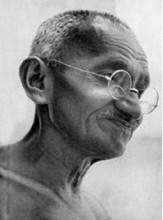

Conversely, it is not hard to find an essentially spiritual orientation within the ranks of both revered religious figures and important social activists.

Along with its complicated doctrine of mental and emotional analysis, Mahayana Buddhism teaches the insignificance of doctrine itself. Only detachment and compassion matter, and all theology (in a Zen Buddhist image) is like a finger pointing at the moon, not the moon (true Enlightenment) itself. Thomas à Kempis, among the most revered of Catholic saints, emphasized a kind of spiritual solidarity: not judgment of others, but a fellowship constituted by shared weakness and need of support. Sufi poets identified with Islam, but also proclaimed their love of spiritual seekers of whatever creed or constancy: “Whoever you may be, come, “ said Rumi, “Even though you may be an unbeliever, a pagan, or fire-worshippers, come, our brotherhood is not one of despair, Even though you may have broken Your vows of repentance a hundred times, come.”

For these and countless other traditional religious voices–who may not have dominated tradition but can easily be found within it–the point of religious life was never verbal acceptance of a particular claim about God, scrupulous performance of ritual, or spending a lot of time judging other people. It was always the manifestation of—surprise—spiritual virtues. To love your neighbor (Christianity); to develop a compassion that makes no distinction between one’s own happiness or suffering and that of others (Buddhism); to be, as Kierkegaard put it, so consumed with living your own life of faith that you don’t have time left over to worry about other people’s failings.

If modern spirituality is particularly detached from conventional creeds, particularly willing to utilize a wide variety of traditional and non-traditional (e.g. psychotherapy, physically oriented hatha yoga) resources, it is nevertheless faces the same struggles as serious people of any denomination. It will always be extremely difficult to discipline the mind, renounce addictive pleasures, care for strangers, accept disappointment, and be grateful when times are rough. Whether we are motivated to do so because God commands us to, or because we just think it is the only way to a really good life, living this way will never come easy. And therefore the struggle to do so is something that “spiritual but not religious” types and the most orthodox of the faithful have in common.

On the political front it seems clear to me that progressive political movements have often foundered on a lack of spiritual virtue. Violence towards the enemy, advancing one’s own group at the expense of others, seeking personal power and even wealth within “the movement,” and a blindness to one’s own oppressive habits can found in the history of communism and socialism, liberalism and feminism, struggles for the rights of marginalized groups, environmental sanity, and national liberation.

Gandhi, 1929. By Vyankappa Kaushik (1890–1988), Counsic Brothers (gandhiserve.org (PEMG1929505003)). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

That is why spiritually-oriented political leaders stand out as beacons of sanity and models of the best of what social justice movements can offer. Gandhi and King faced entrenched power and violent suppression. They responded with teachings of peace, humility, and unrelenting activism. Far from perfect as either individuals or political leaders, they nevertheless avoided many common pitfalls precisely because they focused on spiritual virtues of compassion and self-awareness as much as on the critically important goals of social change. Comparable virtues can be found in Burma’s democracy movement leader Ang San Suu Kyi, and in lesser well-known but highly valuable groups like Mennonite peacemakers and interfaith environmental groups.

Does this all mean that there are no differences among the readers of Yoga Journal and the Catholic World? Between Move On.org and your local yoga teacher? Not at all. It means, rather, that despite very considerable differences there may be some very important things in common. If compassion for others and willingness to ask oneself hard questions are part of what you are about, then spirituality is something you can respect, for it is part of your life already. And if as a spiritual person you care about the fate of humans and the earth, political activism beckons as a vital spiritual practice.

Professor of Philosophy (WPI) Roger S. Gottlieb’s most recent book is the Nautilus Book Award winning Spirituality: What it Is and Why it Matters. You can read the Introduction here.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: first image: Pavillion of Harmony by Nghoyin (Own work). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Second image: Gandhi, 1929 by by Vyankappa Kaushik (1890–1988), Counsic Brothers (gandhiserve.org (PEMG1929505003)). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Religious, political, spiritual—something in common after all? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMeditation in actionThink spirituality is easy? Think again…Indian forces massacre Sikhs in Amritsar

Related StoriesMeditation in actionThink spirituality is easy? Think again…Indian forces massacre Sikhs in Amritsar

Music to surf by

The 20th of June is International Surfing Day. I’m not sure if I have the proper street cred to write about surfing. For one thing, even though I grew up on the Mid-Atlantic coast, I can’t swim. My nephew, however, was part of a hardcore crowd who surfed regularly on the beaches near Ocean City, Maryland, and the Indian River Inlet, Delaware, in the ‘80s and ‘90s. It may not be Southern California, Hawaii, or Australia, but those guys were still amazing.

M Naylor surfs at the Indian River Inlet, Delaware, in the early ‘90s.

These days, I currently live on England’s south coast — perhaps not a place Americans immediately associate with sun and tans or images of jams, hoedads, and bushy bushy blond hairdos.

But heck, yeah, there’s surfing in Britain. Come to Thurso East, Scotland, Devon (where the University of Plymouth offers a degree in surfing) or Cornwall, where it’s only forty miles from Polperro to Perranporth if you want to see the sun rise and set in the sea on the same day (travel time may vary if it’s August Bank Holiday). We even have palm trees.

UK surfing is serious business.

Surfer boys and girls at sunset along the beach at Perranporth, Cornwall, August 2011

I do like surf music, and fortunately, not everyone who plays or listens to surf music must own a wetsuit. Some of the best stuff at the height of the original era (1960 to 1964ish) came from groups as far inland as Colorado (The Astronauts), Minnesota (The Trashmen), and Indiana (The Riveras); The Ventures up in Seattle pounded out terrific instrumentals; Engerland had The Shadows and The Dakotas; and landlocked Hungary has, these days, The Summer Schatzies.

Dancing is part of surf culture, but, I grew up too far north in Delaware, USA, to be part of the Carolina shagging scene (NB: ‘shagging music’ means something distinctly different in Blighty than it does in the Carolinas…). I drive, which surely counts as vicarious surfing. Jan and Dean went sidewalk surfing; surf-pop is, of course, nicknamed ‘surf ‘n’ drag.’ And I like the Beach Boys. A lot. Two years ago I flew to London from Philly just for the weekend to see Brian Wilson perform at the Southbank Centre, and I lectured on him when I taught history of rock. At the moment, the Beach Boys are in heavy rotation in my little car. Their cheerful surf-pop with its complex arrangements and polyphonic vocals kept me from road raging on I-95 in the US, and currently does the same when I navigate the M3 in Britain.

I need those bright vocals, because I’m afraid if I listened to surf-rock, I’d have to replace the Mini with something a bit more sinister as surf-rock’s exotic, sinuous melodies and pounding drums would awaken my dark side. If I’m listening and singing along to ‘Surfin’ USA,’ and you cut me off as you dart across three lanes of rush hour traffic and don’t signal, I’ll just smile and carry on. But if it were ‘Intruder’ by The Madeira, for example, with its relentless vibratos and mean minor chord changes resonating along my spinal chord, I would devolve to a primeval creature, my little car gliding through the traffic like a tiny British Racing Green-coloured shark. A smiling shark. Wearing shades.

Listen to ‘Ghost Hop’ by The Surfmen:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Can you experience Death Valley’s ‘Lammie Don’t Surf’ and not feel transformed?

Click here to view the embedded video.

Before Ritchie Blackmore went all New Age and Celtic music in the ‘70s, he teamed up with E Grieg to go on ‘Satan’s Holiday’ in 1965:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Whether you live in Sioux Falls, North Dakota (which Wikipedia tells me is the point of inaccessibility to the ocean in North America), or that point farthest from the sea in Great Britain (a subject of raging controversy whenever it comes up on chat shows or a slow news day at The Grauniad), these instrumentals capture more than the feel and excitement of riding the perfect wave, the crash of the surf, or the roar inside the pipeline.

Plato, the fourth-century BC philosopher, spent a good deal of his time banging on about how the harmonic intervals that vibrate throughout the cosmos (musica universalis) reverberate in the internal music of mortal beings (musica humana). Humans, he said, resonate sympathetically with the musical vibrations that pulse throughout creation. Consequently good music leads to good behaviour, and this maintains, at the atomic level, an orderly universe. Good vibrations, indeed.

Surfers themselves can be mystical and deeply spiritual, and quite honestly, there is something in the wet reverb and riveting solos of surf-rock instrumentals that vibrates within one’s very bones if not within the soul. Surf-rock, in any of its incarnations, is pure emotion and adrenaline pumped through a Fender amp, realised by vibrato, glissando, and a judicious application of the whammy bar.

The 20th of June is also Brian’s birthday.

Carey Fleiner is a lecturer in classical and early medieval history at the University of Winchester, with a background in teaching the history of rock music. Her areas of interest are imperial Roman women, popular culture in the ancient world, and the Kinks, with upcoming conference papers including ‘Simplicity and the Past as Haven in the Music of Ray Davies and the Kinks’ (which, coincidentally, she will be presenting on Ray’s birthday, the 21st June) and ‘Isabelle of Angoulême: Images of a Queen in the Popular Culture of the 13th, 19th, and 21st Centuries’.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: All images courtesy of Carey Fleiner. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post Music to surf by appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMars and musicEuropa borealis: Reflections on the 2013 Eurovision Song Contest MalmöThe search for ‘folk music’ in art music

Related StoriesMars and musicEuropa borealis: Reflections on the 2013 Eurovision Song Contest MalmöThe search for ‘folk music’ in art music

University as a portfolio investment: part-time work isn’t just about beer money

“When I was at university 25 years ago, I was lucky enough not to need a job. My student grant covered the costs of living in halls, just about, so that what I saved by buying the virtually fat free milk that never went off, I was able to spend on pints of Guinness. If I thought at all about how to spend my time, it was a choice between another game of pool, a third slice of toast in someone’s room, or perhaps – once in a while – a trip to the library.“ (1980s Graduate)

Gone are the days when all students had to wonder about was how much – or little – effort to put into studying without compromising their chances of getting a degree and walking into a graduate job, thanks to changes in higher education funding and increasing student numbers. The participation rate of young people in higher education in the UK has increased substantially over the past half a century, from 6%, in 1960 to 41% by the 2011/2012 academic year. Today’s students face fees up of to £9,000 a year, and high levels of debt. So it is not surprising that many choose to take on part-time work alongside their studies. The growth in term time employment is evident over recent decades, as increasingly the costs of higher education are shifted towards the student, with, for example, a TUC report finding a 54% increase in the number of students undertaking term time employment between 1996 and 2006.

But are they taking jobs just to stem the rising tide of debt? There may be other reasons. A Confederation of British Industry survey indicates that both employers and students pay at least as much attention to ‘employability skills’ (e.g., self-management, team working, business awareness, and problem-solving) as to degree results, and hence students need more than just their academic achievement to gain a foothold in the graduate labour market. Although it diverts time from study at a potential cost to academic achievement, term-time employment may be a useful way to demonstrate these employability skills to prospective employers.

But are they taking jobs just to stem the rising tide of debt? There may be other reasons. A Confederation of British Industry survey indicates that both employers and students pay at least as much attention to ‘employability skills’ (e.g., self-management, team working, business awareness, and problem-solving) as to degree results, and hence students need more than just their academic achievement to gain a foothold in the graduate labour market. Although it diverts time from study at a potential cost to academic achievement, term-time employment may be a useful way to demonstrate these employability skills to prospective employers.

In effect, students now have a portfolio of investment decisions to make, not just about how to fund their education, and how much time they invest in academic work, but also about how to invest in skills that give them an edge in the labour market. As well as generating an additional source of income, term time employment might be useful investment in human capital. This idea has been previously considered, especially in a Northern American context, but no prior work captures the interlocking nature of higher education students’ decisions about borrowing, paid employment, studying, employability, and leisure.

We conducted a detailed empirical study of the effects of working while studying on both academic outcomes and early career labour market success. When we looked at choices about loans and about how many hours to work during term-time, we found that students are clustered at one of two extremes in each case. 82% of students choose the maximum loan available to them, with 10% at the other extreme of zero loans. A similar pattern occurs with term time employment, with 51% of students not working during term time and at the other extreme 16% committing to a high intensity of term time employment. These patterns suggest that the incentive structure systematically pushes HE students towards corner solutions for both loans and employment, with only a minority choosing other solutions.

We used these empirical results to develop a model explaining the varying degree of behaviour, which is dominated by student choices at corner solutions. One key feature of our model is that term time employment strengthens and signals ‘soft’ skills such as ambition, propensity to work and employability skills, which are distinguishable from ‘hard ‘skills (academic achievement), although the extent to which term time employment can signal these soft skills may be dependent on the type and the amount of paid employment. Factors that affect students’ decisions include: size of parental transfers, the rate of return they receive from studying and term time employment, borrowing constraints, loan repayment rate, preference for leisure and consumption (both current and future), and level of fees.

Our model raises the question of whether term time employment is a good or bad thing. It may eat into study time, potentially reducing academic achievement, especially for those working out of financial necessity. But at the same time, beyond providing additional income, it brings experience of work and signals motivation and initiative to future employers.

Sarah Jewell is a lecturer at the University of Reading, whose current research interests include UK graduate labour market outcomes. Jim Pemberton is emeritus professor at the University of Reading. Alessandra Faggian is Associate Professor at the Ohio State University, AED Economics Department and co-editor of Papers in Regional Science. Zella King is an Associate Professor at Henley Business School at the University of Reading. They are the authors of the paper ‘Higher education as a portfolio investment: students’ choices about studying, term time employment, leisure, and loans’, recently published in Oxford Economic Papers.

Oxford Economic Papers is a general economics journal, publishing refereed papers in economic theory, applied economics, econometrics, economic development, economic history, and the history of economic thought.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Open books and a hand with pen. By yekorzh, via iStockphoto.

The post University as a portfolio investment: part-time work isn’t just about beer money appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy are married men working so much?Forcible feeding and the Cat and Mouse Act: one hundred years onPlebgate

Related StoriesWhy are married men working so much?Forcible feeding and the Cat and Mouse Act: one hundred years onPlebgate

June 19, 2013

Multifarious Devils, part 4. Goblin

Petty devils are all around us. Products of so-called low mythology, they often have impenetrable names. (Higher mythology deals with gods, yet their names are often equally opaque!) Some such evil creatures have appeared, figuratively speaking, the day before yesterday, but that does not prevent them from hiding their origin with envious dexterity (after all, they are imps). A famous evader is gremlin. It has the same “suffix” as goblin, and quite probably borrowed -lin from its ancestor. The “ancestor” is known to have caused mischief already in the twelfth century, while the word gremlin surfaced in the Royal Air Force (RAF) around 1920. It may seem strange that we don’t know the derivation of such a recent coinage, but such is the fate of all slang; our acquaintance may have come up with a catchword and never boasted of it. As a result, dictionaries say ruefully: “Origin unknown.” Is gremlin a grim goblin (that is, a slightly altered blend) or a witty variant of Kremlin (a place responsible for all kinds of trouble)? Since this is anybody’s guess and moreover, since gremlin also means (or meant) a low-ranking air pilot, we will leave Mr./Ms. Anybody at their guessing game and turn to goblin.

The names of demons often fall victim to taboo. People believed that, if they pronounced goblin (to give one example), the creature would mistake the speech act for an invitation and come, but if the sounds were scrambled, the danger would be averted (obviously, if you said Kid, no one called Dick would appear). See the post on Old Nick. It once occurred to me that goblin was really boglin, with gob for bog, as in bogey, and an obscure diminutive suffix. However, I gave up this idea, because -lin kept vexing me. The diminutive suffix is -in; -l belongs to the root. Later I learned that I had a predecessor who launched the same hypothesis in 1953. This is the reward or punishment for having a good etymological database. You always discover that, however imaginative you may be, you are not the first. Nothing like having someone to prick your vanity.

As always, people have tried to derive goblin from some similar-sounding word: gobble or French gober “swallow, gulp down” (though goblins are not cannibals and do not devour their victims) and even gibberish (though the resemblance is slight, and goblins do not have a reputation for obsessive chattering). According to the funniest theory, elves and goblins go back to Guelphs and Ghibellines, the names of two political parties that divided Italy during the Middle Ages, when the Pope and the Holy Roman Empire were at daggers drawn. The author of this etymology was E.K., the otherwise anonymous glosser of Edmund Spenser, the author of Fairie Queene. Before that great poem he published Shepheardes Calender (1579), and in the commentary on “June Eclogue” E.K. tells us that elves and goblins were invented to keep the common people in ignorance:

“When all Italy was distraicte into factions of the Guelfs and the Gibelins, being two famous houses in Florence, the name began through their great mischiefs and many outrages, to be so odious, or rather dreadful… that if theyr children at any time were frowarde and wanton, they would say to them that the Guelfs and the Gibeline came. Which words nowe from them… be come into our usage, and, for Guelfs and Gibelines, we say Elfes and Goblins….”

James f. Royster (1928), of the University of North Carolina, suspected (quite rightly, I believe) that E.K. had borrowed his etymology from an earlier authority but failed to find the source. This etymology received a mention in two great seventeenth-century dictionaries (Minsheu’s and Skinner’s), and to my amazement, I found it in a British encyclopedia published less than a hundred and fifty years ago.

We have only one firmly established fact at our disposal. Orderic Vitalis (1075-1142), an English chronicler and Benedectine monk, gave an account of a certain demon called Gobelinus (that is, Gobelin; -us is merely a Latin ending), expelled from a neighboring temple in Normandy. It follows that the English probably borrowed the word from northern French. We would like to know how the French obtained it. A similar word is German kobold “brownie,” a house spirit and a gnome that haunts mines (I mentioned it in connection with nickel, while dealing with Old Nick). Its origin is also unclear, and consequently, we remain in the dark as to its affinity with goblin. Perhaps kob-old consists of a word for “hut; dwelling,” with the second part meaning “ruler” or “spirit” (two candidates have been proposed). But perhaps this interpretation is a clever folk etymology. We also have Medieval Latin cobalus “mountain spirit.” The route might be from Germanic or simply German to Medieval Latin, to northern French, and from there to English. In this well-designed itinerary, a small point seems to have been overlooked, namely the absence of -d or -t in the English word. Whatever the ultimate origin of -bold — in Old Engl. cofgodas or cofgodu, plural (cof “chamber,” god “deity”) and in German Kobold — d is present but in goblin it is not. Only once have I run across a puzzled query about the loss of d in Gobelinus ~ goblin. Yet this question strikes me as important.

From early on, etymologies have cited Greek kóbalos “an impudent rogue, an arrant knave” (the plural Kóbaloi meant “a set of mischievous goblins, invoked by rogues”) and derived goblin from it. However, in later dictionaries, including the 1910 edition of Skeat, who followed the OED, the idea of the Germanic origin goblin has prevailed. I see little advantage in the Greek etymology. The truth will, of necessity, remain hidden, but goblin looks like a migratory name of a malicious hideous sprite. In Greek, the word is usually believed to be of Phrygian origin, though its relatedness to the root for “vault, arch” (verb) has also been considered. (Kóbalos emerged as “the spirit of the cave,” a rather fanciful reconstruction.) Its way to the rest of Europe cannot be traced, for Medieval Latin cobalus has no known etymon in Classical Latin. Orderic’s Gobel-in is fairly close to kóbal-os, while Old English cof-god is not.

If German kobold goes back to kob-walt or kob-hulth, it has nothing to do with the Greek form but resembles (somewhat) the Old English one. To be sure, one can suggest that not the entire Greek word but only its root caught the imagination of the oldest Germanic speakers and that to this root, reinterpreted as “chamber; dwelling,” they added their own words meaning “god; ruler; spirit.” Cob is such a common syllable in the languages of the world that its association with some other word can always be expected. For instance, when we hear Welsh coblyn “goblin,” from English, cobio “thump” comes to mind (as in coblyn y coed “woodpecker”). On the other hand, Old Engl. cof-god- may, like its German analog, have been independent of the migratory word I posited. Then goblin owes nothing to Germanic. I don’t know the answer but would like our most authoritative dictionaries to be less dogmatic when it comes to dealing with such a sly creature. Too bad lexicographers have not invited Harry Potter as a consultant.

Gobelin, a national establishment in Paris, celebrated for its tapestry and upholstery, goes back to the family named Gobelin. The existence of such a forbidding surname need not surprise us; compare the German family names Teufel, Düwel (both mean “devil”), and Waldteufel (= forest devil). In hobgoblin, hob- is a variant of Rob, Robert being a common name of the devil (compare Robin good fellow). The whole has a particularly good ring, because hob- rhymes with gob-.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: “The Goblins in the Gold-Mine” The Book of Knowledge, The Children’s Encyclopedia, Edited by Arthur Mee and Holland Thompson, Ph. D., Vol II, Copyright 1912, The Grolier Society of New York. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Multifarious Devils, part 4. Goblin appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDrinking vessels: ‘tankard’How come the past of ‘go’ is ‘went?’Drinking vessels: ‘goblet’

Related StoriesDrinking vessels: ‘tankard’How come the past of ‘go’ is ‘went?’Drinking vessels: ‘goblet’

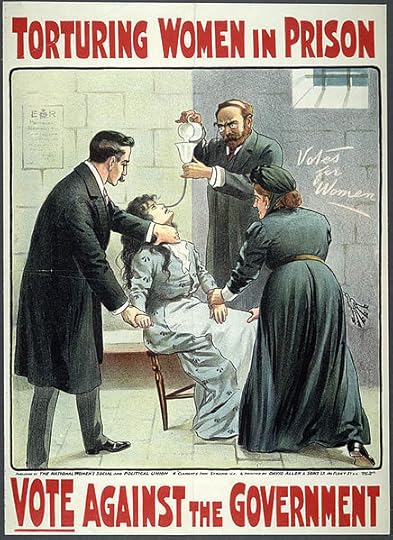

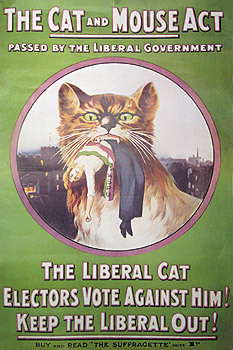

Forcible feeding and the Cat and Mouse Act: one hundred years on

Between 1909 and 1914, imprisoned militant suffragettes undertook hunger strikes across Britain and Ireland. Public distaste for the practice of forcible feeding ultimately led to the passing of the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act, or ‘the Cat and Mouse Act’ as it was more commonly known. The 25th of April 2013 marks the 100th anniversary of this Act, passed so that prison medical officers could discharge hunger-striking suffragettes from prisons if they fell ill from hunger.

“Torturing Women in Prison. Vote Against the Government.” London: National Women’s Social and Political Union, ca. 1909. Color Lithograph. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (117b)

My research revealed that contrasting perspectives existed on the purpose of forcible feeding: whether it was a therapeutic or coercive practice. The Home Office insisted that prison doctors performing the practice were preserving the life of prisoners who would otherwise starve. According to this perspective, forcible feeding was safe, humane, and ethically uncomplicated. In response, enraged suffragettes filled the pages of their newspaper Votes for Women with contradictory medical testimony claiming that forcible feeding risked producing an array of complaints including throat laceration, stomach damage, heart complaints, syncope, and septic pneumonia should food accidentally enter the lungs.

Medical opposition was rife. Suffragette doctor Louisa Garrett Anderson publicly insisted that forcible feeding was coercive. Physiologist Charles Mansell-Moullin asserted that ‘violence and brutality have no place in hospital’. Psychiatrist Lyttelton Forbes Winslow stated that so many risks were proven to accompany artificial feeding in clinical practice that he had long since abandoned the method, adding details of one case where the patient had allegedly bitten off his own tongue after it had become twisted behind the feeding tube.

The suffragettes left a rich array of autobiographical and printed resources which detail their problematic encounters with Edwardian prison doctors. For instance, in 1909, Laura Ainsworth wrote of her painful feeding through her nostrils with a tube. In addition, she described an alternative procedure which involved the prison medical officers pinning her down, her mouth being prised open with a steel instrument, and the insertion of a tube into her gullet which caused choking and intense nausea. Ainsworth continued to be fed twice daily in this manner until she was eventually moved to a hospital to be fed with a feeding cup. The following year, another female prisoner recalled how she had once overheard her doctor exclaiming that ‘this is like stuffing a turkey for Christmas’.

Artist/Photographer/Maker, Women’s Social and Political Union, David Allen. Date, 1914. Museum of London. Image Number 004152.

Between 1909 and 1914, opponents of forcible feeding strove to decisively prove its physical and psychological consequences. They raised fascinating ethical questions: did forcible feeding have adverse psychological effects? Did it cause illness or simply hasten pre-existing conditions? And was it ethically appropriate to forcibly feed mentally ill individuals? A particularly provocative case which I discovered was that of William Ball, subject to the procedure from Christmas Day 1911. By February, Ball believed that he was being tormented by electricity. Although his imaginary fears of electrical torture subsided, he began smashing his prison windows under a false illusion that a detective was waiting outside for him. Some weeks later, Ball announced to his prison officials that he no longer minded his electrical torture so much but objected vehemently to the needle torture that he was now being subjected to. In June 1912, Emily Davison threw herself on to the wire netting on the prison landing, and then dramatically flung herself through a gap in the netting, crashing onto a set of stone stairs. Davison later recounted this attempted act of suicide as resulting directly from the horrors of being forcibly fed.

Efforts to prove the harmful physical and psychological effects of forcible feeding became ever more refined following Ball’s case. In 1912, dermatologist Agnes Savill, Mansell-Moullin, and surgeon Victor Horsley published an extensive report intended to pressure the government into reassessing its policy. They delivered an extensive account of the physical and mental implications of forcible feeding that detailed a range of physical and emotional effects including cerebro-spinal neurasthenia and exaggerated knee reflexes and fatigue. The authors also identified the mental anguish produced by hearing the cries, choking, and struggles of their friends as psychologically damaging.

Pankhurst, Emmeline (1911). The Suffragette. New York: Sturgis & Walton Company. p. 433.

The issue of feeding patients who suffered from physical or mental debility also captured public attention. During 1913, the Home Office came to believe that militant suffragettes were encouraging “abnormal and neurotic” individuals to become imprisoned to increase the likelihood of martyrdom. It feared that militants were being specially selected to commit punishable crimes who were “weaklings suffering from physical defects in order to cause as much embarrassment as possible to the authorities.” Types believed to have been chosen ranged from people with histories of fits, those who had suffered a nervous breakdown, the “mentally unstable” and the “eccentric.” Margaret James was noted to be “a dwarf, an epileptic, and a cripple, and in weak physical condition.” Her medical officers feared that, if forcibly fed, epilepsy and mental excitement might ensue, firmly tipping James over the borderline to insanity. Royal assent was given to the Cat and Mouse Act on 25 April 2013 in response to public unease about, and medical opposition to, forcible feeding.

Ian Miller is a Irish Research Council Government of Ireland Postdoctoral Fellow at the Centre for the History of Medicine in Ireland, University College Dublin. He is the author of “‘A Prostitution of the Profession’? Forcible Feeding, Prison Doctors, Suffrage and the British State, 1909–1914” in the latest issue of Social History of Medicine, which is available to read for free for a limited time. His first monograph, A Modern History of the Stomach: Gastric Illness, Medicine and British Society, 1800-1950 was published by Pickering and Chatto in 2011. A second monograph, Reforming Food in Post-Famine Ireland: Medicine, Science and Improvement, 1845-1922, is in press with Manchester University Press. Read his food history blog Digesting the Medical Past and follow him on Twitter @IanMill33234498.

Social History of Medicine is concerned with all aspects of health, illness, and medical treatment in the past. It is committed to publishing work on the social history of medicine from a variety of disciplines. The journal offers its readers substantive and lively articles on a variety of themes, critical assessments of archives and sources, conference reports, up-to-date information on research in progress, a discussion point on topics of current controversy and concern, review articles, and wide-ranging book reviews.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Forcible feeding and the Cat and Mouse Act: one hundred years on appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPrepare for the worstTwo parents after divorceFinding the future of democracy in the past

Related StoriesPrepare for the worstTwo parents after divorceFinding the future of democracy in the past

Finding the future of democracy in the past

There are two different questions that might be asked about contemporary democracy: how did we get here? And where else might we have tried to get? A great deal of the ‘history of democracy’’ is written in the former mode, with the classical world and subsequent periods being identified as steps in a path towards a modern democratic world in which the people elect their governments and hold them accountable to greater or lesser extents. In Britain, the normal staging posts identified are the Levellers, the 1790s, the Great Reform Act, and the suffragist movement. In America they are the Declaration of Independence in 1776, the Federal Constitution of 1788, Jacksonian Democracy in the 1830s, the Civil War, and the Voting Rights act of 1965. In France, the French Revolution, 1830, 1848, 1871, 1836, and 1944. Ireland has far fewer dates!

This sort of history is in effect being written backwards; it is a history of the present and how we got to it, not a history of the past, and what we might have fought for. One mark of this approach is that relatively little attention is given to the language people actually used; if we think their aspirations were democratic then it is assumed that we can describe their goal as democracy, even if they didn’t use the word. Moreover, since we link democracy to elections, we assume that the history of democratic aspiration was primarily a story of struggle over the suffrage. But much of this does violence to the evidence.

This sort of history is in effect being written backwards; it is a history of the present and how we got to it, not a history of the past, and what we might have fought for. One mark of this approach is that relatively little attention is given to the language people actually used; if we think their aspirations were democratic then it is assumed that we can describe their goal as democracy, even if they didn’t use the word. Moreover, since we link democracy to elections, we assume that the history of democratic aspiration was primarily a story of struggle over the suffrage. But much of this does violence to the evidence.

If we ask what people who wanted to put more power in the hands of ordinary men (or more rarely, women) thought that they were doing, and how they conceptualised their objectives and behaviour, we find that democracy came on to the scene as a popular term rather belatedly. Throughout the eighteenth century, it was a literate term, referring to ancient Greece and Rome, though also used by educated commentators to refer to small, faction-ridden, tumultuous states, prone to collapse under the influence of demagogues into despotism. Though they could imagine that modern states might, like Britain, have a relatively democratic component, few of those who knew the term thought that ‘democracy’ had any relevance to the growing commercial empires of late eighteenth-century Europe.

Yet, within a hundred years, democracy had become established as part of the political lexicon across the populations of America, France, Britain and Ireland. It was still widely condemned by many, who saw it as a force that threatened the social, economic and political order; but by 1848 it had established advocates, and more inspiring connotations. Even those who spoke of it with some trepidation saw it as a modern phenomenon, often as ineluctable, and as something to which the political order needed to adapt. Not only had the word acquired new significance and connotations, but also in different countries different meanings and institutions had come to be associated with it. In France, for instance, it had become identified with formal and to some extent real social levelling that political institutions had somehow to contain, whereas in Britain it was associated with active political struggles for more effective popular control of the House of Commons. In Ireland it was associated with mass mobilisations, designed to affect political agendas more than political institutions. In this process of re-imagining democracy many came to associate it with innovation, with new ideas, experiences and experiments, and saw new possibilities opened for them. This is not a story of steady progress towards a determined goal: it remained uncertain how and even whether the people’s wish to share in the exercise of power could be given stable institutional form. Nor was it a story of steady progress towards any goal — the French Revolution did much to rendered the term anathema across Europe for more than twenty years. It is, however, an often surprising story. These four countries shared a classical inheritance and understandings of ‘democracy’ derived from that, but in responding to local experiences and conflicts, they developed sometimes strikingly different understandings and practices, and they differed too in what they arrayed under the banner of democracy as that came to be unfurled.

If we read the past wholly in the light of the present, then we also will read our futures in that way. But if we recognise the foreignness of the past, and the very different ways in which people in different political settings responded to the pressures of social change and the emergence of more popular forms of politics at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth centuries, we may find ourselves able to ask questions of our present — and of our futures — that would not otherwise be asked.

Mark Philp and Joanna Innes are co-editors of Re-imagining Democracy in the Age of Revolutions: America, France, Britain, Ireland 1750-1850 (OUP, 2013). Mark Philp has taught political theory in Oxford University for thirty years and has worked extensively on the political thinking and social movements of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in Britain, and on methodological approaches to the study of political ideas. Joanna Innes was educated in Britain and the United States. She has taught and researched at Oxford University for thirty years. Her interest in this subject grows out of her interest in government and political culture in Britain and elsewhere, especially during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: To speak up for democracy, read up on democracy poster [Fair Use] via Library of Congress.

The post Finding the future of democracy in the past appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPrepare for the worstThe History of the World: Napoleon defeated at WaterlooThe case for a European intelligence service with full British participation

Related StoriesPrepare for the worstThe History of the World: Napoleon defeated at WaterlooThe case for a European intelligence service with full British participation

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers