Oxford University Press's Blog, page 931

June 25, 2013

Concerning the cello

How many times have I heard someone say, “Oh, I just love the cello! What a beautiful instrument!”? Certainly too many to count or remember, since I began playing the instrument at the age of nine. Of course, it’s little wonder that the cello resonates so strongly with people, since its range and timbre so neatly overlap with the human voice, as many cellists will be quick to point out. So it is that even someone playing the cello for the first time could draw out a deep and round open C, with a tone rivaling a rare basso profondo, while intermediate players begin to work their way further up the fingerboard into the tenor range, and those who wish advance further must hone the quality of the upper-most registers, which scream and soar like a soprano (and I really do mean that in the kindest way possible).

The ease of relation and appreciation creates an irony in my own musical history, which is that I play the cello precisely because of its unpopularity. I clearly remember the session my third grade class attended near the end of the school year to sample and select the instruments which we would begin receiving instruction in when school resumed again in the fall. Working his way down a line of instruments, the band teacher called eager students one by one to the front of the room for a shot at making sound. Kids were practically jumping out of their seats to try the cool instruments like the trumpet and the saxophone — but when the cello’s turn came, it was met with silence. Being someone who seriously struggles with silence, it was in my nature to volunteer and “save the day”. All it took was one stroke of the bow across the lower strings for me to begin to appreciate the power of the instrument. I felt its vibrations where it touched my legs, chest, and hands. Yes, I could do this, I thought to myself. I like this.

The ease of relation and appreciation creates an irony in my own musical history, which is that I play the cello precisely because of its unpopularity. I clearly remember the session my third grade class attended near the end of the school year to sample and select the instruments which we would begin receiving instruction in when school resumed again in the fall. Working his way down a line of instruments, the band teacher called eager students one by one to the front of the room for a shot at making sound. Kids were practically jumping out of their seats to try the cool instruments like the trumpet and the saxophone — but when the cello’s turn came, it was met with silence. Being someone who seriously struggles with silence, it was in my nature to volunteer and “save the day”. All it took was one stroke of the bow across the lower strings for me to begin to appreciate the power of the instrument. I felt its vibrations where it touched my legs, chest, and hands. Yes, I could do this, I thought to myself. I like this.

Little did I know how infuriatingly difficult the instrument is to play. Coming from several years of piano instruction, I was used to a different sort of relationship between technique and tone. Where the piano is straightforward — you know exactly what you’re going to get when you press a key, because consistency, equality, and reliability are infused in the instrument’s essence — so little about the cello seemed to be trying to help me produce anything beautiful at all. I learned to struggle with intonation on a fretless instrument, where each note’s success depends on the placement of your left-hand fingers down to the smallest fraction of an inch and the bow requires an attention to the subtlest degrees of difference in angle, pressure, and speed. Even the process of tuning the instrument was outrageous, and often led to my complete neglect of practice for extended periods of time.

That being said, I did pursue private study and continued with the instrument throughout high school. The instrument became more natural as I matured and practiced, and the orchestras and ensembles I played with brought me into pit bands around New York, across the ocean to Vienna and Salzburg, down south to New Orleans, and ever upwards until I had played Carnegie Hall. The cello brought me across the world, and now I feel like it’s only right to be mindful of where the cello itself came from, and where it may be going.

There is a consensus among musicologists that the history of the cello may be traced back, along with the rest of the stringed instruments, to those early hunters who first realized that plucking the sinews of their bows unleashed forms quite distant from the violent forces that had determined the weapon’s existence. Thus began a peaceful appropriation of the hunter’s equipment as a new branch of a cultural evolution no longer geared towards survival, but instead amusement. What followed were generations of experiments with the string’s length, density, material, and number; additions to the instrument’s body for the purposes of pitch and resonance, until we arrived (quite recently) at the viol in the 15th century, the violone (bass violin) in the 16th, and the violoncello (‘cello or cello for short: literally meaning “small large viol”) across the 17th and 18th centuries. Then, as orchestras became more organized structures, conformity became a necessity and the most successful, versatile instrument models became the norm of today.

These days we have the benefit of video, so my narrative will take a turn if you’re willing to come along. People are still doing cool things with the cello. Really cool things. Like A Cello Rondo, in which Ethan Winer plays 37 different cello parts to create one song. Or this head-banging rendition of “The Final Countdown,” featuring three distorted cello soloists backed by a full rock orchestra. The cello continues to bridge genres with the international success of Apocalyptica, whose Finnish metal sound is about as heavy as their name would imply. What they’ve done is fascinating to me, but Ben Sollee is perhaps more accessible, as a singer-songwriter who mixes folk, bluegrass, and jazz. I would even say that Kevin “K-O.” Olusola gives Justin Timberlake a run for his money with his cover of the recent hit, “Mirrors.” Finally, this tour would feel incomplete to me, personally, if I did not mention Eugene Friesen’s brilliant playing year after year with the Paul Winter Consort as they celebrate the winter solstice at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine: here, the cello is an integral part of a New Age ensemble with a global consciousness, upholding an ancient pagan tradition.

It’s really all quite an elegant picture. In a sense the cello was born of carnivorous hunger, modified by playfulness and curiosity, and standardized by Western precision and discipline. Today the instrument is a forceful presence in genres of all kinds across the entire planet. And its journey isn’t even over yet: to see what’s next, it looks like you’ll just have to stay tuned.

Simon Riker grew up in Rye, New York, and has spent his entire life so far trying to get a job in a skyscraper. When Simon isn’t interning at Oxford University Press, he can be found studying Music and Sociology at Wesleyan University, where he expects to graduate next year.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Cello, isolated on white with clipping path. © Robyn Mackenzie via iStockphoto.

The post Concerning the cello appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMusic to surf byMars and musicEuropa borealis: Reflections on the 2013 Eurovision Song Contest Malmö

Related StoriesMusic to surf byMars and musicEuropa borealis: Reflections on the 2013 Eurovision Song Contest Malmö

June 24, 2013

Google: the unique case of the monopolistic search engine

In early January, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) closed its nearly two-year investigation into Google’s conduct. Unanimously, the Commissioners stated that Google’s alleged favoring of its own vertical search features in search results was not an antitrust violation. They found that changes to Google’s search algorithm were intended to offer more informative search results. The FTC acknowledged that modifications of Google’s algorithm deprived some vertical search sites of traffic, but stated that harm to competitors is a “common byproduct of ‘competition on the merits.’” Responding to other allegations, Google voluntarily agreed to stop appropriating content from vertical search engines and allow online advertisers greater flexibility in managing concurrent ad campaigns on multiple search engines. Investigations into Google’s practices continue in other jurisdictions, including the European Commission (EC) and the Korea Fair Trade Commission (KFTC). Given the high level of cooperation between these authorities in the Google matter, it seems unlikely that the pending investigations will reach significantly different results, though they may lead to legally binding commitments. Under a proposed settlement with the EC, Google has, among other things, offered to label its own vertical features and display three relevant non-Google vertical sites in search results. Reports indicate that many competitors of Google and some consumer groups are unhappy with the proposal, believing it to be inadequate. If adopted, this remedy would not differ dramatically from Google’s original, voluntary pledges to the FTC. (Given the scrutiny it has received and will continue to receive, Google would be foolish not to abide by these legally non-binding commitments to the FTC.)

Google Logo in Building43 by Robert Scoble, CC BY 2.0 , via Flickr.

We do not have access to the proprietary data and diversity of viewpoints available to these various antitrust authorities. But the question we would like to raise in this editorial is: “what if?” Suppose the FTC had found that Google’s search bias violated antitrust laws, or that such a finding could be made by another antitrust authority around the globe, concluding that the remedy proposed by Google to the EC was insufficient. Beyond the clear labeling of Google’s own services and the prominent displaying of non-Google sites, what remedy would be appropriate to counter the allegedly illegal conduct adopted by the firm?

Ongoing supervision of Google’s search algorithm is fraught with problems. Google constantly revises its algorithms to improve its search results. It is doubtful that any of the antitrust authorities mentioned above have the institutional capacity to review every significant or complaint-inducing change to Google’s search algorithm. And, in the event Google’s search formula could be monitored, this regulatory oversight would raise multiple concerns. First, detailed regulation of a dynamic company may deter desirable innovation. Second, regulation affecting the display of content in one of the primary gateways to the Internet would raise legitimate concerns of government control over access to information and speech. A structural remedy would avoid the pitfalls of a regulatory solution. For example, an authority could, in theory, direct Google to divest its vertical search sites and confine itself to general search. This would reduce Google’s incentive to modify its algorithm to favor its vertical search offerings. Yet, structural separation, by prohibiting vertical integration between different categories of search, could impede functional improvements. It is a conundrum.

This all should not eliminate concerns over Google’s market power. Google remains the dominant search engine in the United States and around much of the world. Google’s power should concern everyone who values an open Internet, not to mention the protection of privacy. At present, Microsoft’s Bing is the primary constraint on Google’s ability to manipulate search results. Users dissatisfied with Google have the option of using Microsoft’s search engine. Without Bing’s presence, a monopolistic Google would have the power to change its search algorithm with less regard for user preferences. The focus in military intelligence on capabilities rather than intent of a potential enemy is instructive. For example, consider the risks presented by Google under different, more ideological leadership. Could it rig its search results to give prominent rankings to only conservative (or only liberal) news sites and blogs, and even attempt to manipulate the preferences of undecided voters?

Despite the limitations of antitrust law, governments around the world are not powerless to preserve an Internet with multiple search engines. After all, they are among the largest purchasers of goods and services in the world. To promote the public interest in free and open access to information on the Internet, they should use their power to ensure the long-term survival of Bing (and other smaller non-Google search engines). They could, for example, require IT vendors to make Bing the default search engine on millions of government computers and move a significant fraction of advertising for government jobs and contracts from Google to Bing. Governments have other opportunities to tilt a playing field in the larger interest of maintaining a competitive industry structure. These policies could increase the number of visitors to Bing directly and also make Bing a more attractive resource for search relating to government.

Critics of this proposal might allege that it would be an unprecedented attempt by governments to “pick winners.” Ordinarily, the antitrust laws protect the competitive process against collusion and exclusion. In universal search, however, the antitrust laws alone likely cannot preserve a competitive market. Moreover, if Google turns out to be a natural monopoly, because of economies of scale and scope, public utility regulation or public ownership — the normal governmental responses — have significant shortcomings, including free speech objections. With the gatekeeper role that search engines play in the Internet, the existence of multiple engines is arguably even more important than having multiple producers in most markets. Furthermore, direct promotion of competition by national governments has famous precedents. During the Second World War, the US government constructed several aluminum smelters because Alcoa did not have sufficient capacity to meet wartime demand. Following the war, the government sold the smelters to Kaiser and Reynolds at discount prices to end Alcoa’s decades-long monopoly. More recently, the Brazilian government opted to purchase computers with open-source Linux instead of Microsoft Windows, to save money and develop an affordable operating system designed for local needs.

As a general principle, governments should not offer direct support to some companies, and not others. And, furthermore, the actual power of governments to promote competition through their purchasing decisions is far from certain. But sometimes neither antitrust nor regulation can adequately protect the public. The case of Google requires us to consider all alternatives, including the deliberate use of public resources to maintain effective choice in information sources on the Internet.

Albert A. Foer is President of the American Antitrust Institute and Sandeep Vaheesan is Special Counsel. A version of this article originally appeared as an editorial in the Journal of European Competition Law & Practice.

Journal of European Competition Law & Practice is a peer-reviewed journal dedicated to the practice of competition law in Europe. Primarily focused on EU Competition Law, the journal includes within its scope key developments at the international level and also at the national EU member state level, where they provide insight on EU Competition Law.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS

The post Google: the unique case of the monopolistic search engine appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPlebgateDoes Elton John have a private life?The highest dictionary in the land?

Related StoriesPlebgateDoes Elton John have a private life?The highest dictionary in the land?

Oh, I say! Brits win Wimbledon

It’s 1 July 1977: the Jacksons are Number 1 in the UK charts; a pint of beer costs 40 pence, milk per pint is 11p; Elvis has just given what will be his final concert; Virginia Wade becomes the last British player to win the women’s singles tennis championship at Wimbledon.

It’s 4 July 1936; a pint of milk costs 2d; it’ll be another 16 years until someone invents the ‘hit parade’; you can buy a newspaper for 1d. Summer headlines in those papers include Edward VIII’s relationship with Mrs Simpson, test flights of the Spitfire, and Fred Perry—the last British player to win the men’s singles championship at Wimbledon.

In recent years it’s become a feature of the British summer season. Whether or not tennis is your game, for two weeks in June/July a nation dares to hope. We’ve been getting closer—first, with Come on Tim! Henman and now Andy Murray. Today the collective sentiment is more expectation than flight of fantasy, though the reality remains elusive. It hasn’t always been so. Winners’ boards at Wimbledon were once generously populated with the names of British players. Indeed, Fred Perry’s victory in July 1936 completed a remarkable hat-trick of men’s singles titles from 1934.

In the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography we’ve the stories of 11 one-time British Wimbledon champions—who together scooped 44 singles titles between 1886 and 1937—as well as many others who came close, among them Bunny Austin, the last British men’s singles finalist (in 1938) until Andy Murray’s appearance in 2012. If you’re reading this on Monday 24 June—the opening day of this year’s Wimbledon—then everything’s still possible. If you’ve come to us in Week Two this may no longer be the case. However things unfold, it’s sure to be an exciting couple of weeks during which the following may inspire, or console, as required.

Viewed across 77 fallow years, Fred Perry’s Wimbledon achievements can appear quasi miraculous. But they’re less extraordinary when seen in the context of some other leading British and empire players of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Between 1910 and 1913 the New Zealand-born, Cambridge-educated Anthony Wilding went one better than Perry, securing four successive men’s singles victories. More remarkable was that he did so while pursuing a high-flying legal career, having been appointed solicitor to the New Zealand supreme court in 1909. But Wilding’s achievement still falls short of that of the Doherty brothers, Reggie and Laurie. Together they shared the men’s singles title nine times between 1897 and 1906—Reggie consecutively from 1897 to 1900 before (after a year’s interlude) handing over to Laurie (1902-6). The brothers differed in their approach to the game and were dubbed ‘Big Do and Little Do’ for their distinctive physiques. Tall, thin Reggie covered the court with languid ease while the more diminutive Laurie brought guile and intelligence. What they shared was the ability to win. Near invincible for a decade on their own, together in doubles they were near invincible squared, winning eight All England Championships (1897-1905) and becoming Olympic gold medallists in 1900.

Dorothea Douglas, 1903

In the women’s game, Wimbledon’s greatest British player (on singles titles alone) is Dorothea Lambert Chambers who won the title seven times between 1903 and 1914—victories five, six, and seven coming after the birth of her two children. Though she added no further titles post-war, Chambers continued to play at Wimbledon until 1927 when, aged 49, she notched up her 161st competitive match in SW19. Though the post-war era brought younger challengers and new styles, Chambers remained unmoved. One match report from 1919 noted that her only concession ‘to the passing of time since 1903 was that her long-sleeved blouse was open at the neck and her long skirt just a trifle longer’.By contrast, Chambers’ nearest rival Charlotte Sterry proved more open to innovation, being one of the few women to serve overhead before the style was widely adopted in ladies’ tennis from the late 1910s. A five-times Wimbledon champion, Sterry won her final title (a memorable victory over Chambers) in 1908, and this after a seven-year interval to bring up her children. Blanche Hillyard’s span of victories was longer still, with 14 years dividing her first title (in 1886) and her fifth and last (1900) in a Wimbledon career of nearly three decades. In Hillyard’s hand the racket also became a weapon in debates over women’s equality. As she wrote in her 1892 guide to the sport: “In tennis our sex can compete with a certain amount of equality with the ‘lords of creation,’” since playing “promotes that coolness of head … which we are so often taunted with lacking.” Finally there’s Lottie Dod, the supreme British sportswoman of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, whose dominance (five Wimbledon singles championships, 1887-93) ended only because she declared herself ‘bored’ with tennis and went off to try other sports. These included racing cycling, golf, archery, skiing, tobogganing, mountaineering, hockey, and archery. Where most people really do ‘try’ a new sport, Dod excelled. Post-Wimbledon she won golf championships, played hockey for England, and secured an archery Silver at the London Olympics of 1906.

It’s not just about the number of titles won, of course. Some of Britain’s tennis greats owe their place in the Oxford DNB to the timing of a victory or indeed sometimes to the nature of a defeat. In July 1934 Dorothy Round won her first Wimbledon singles title, as did Fred Perry in the men’s competition. Celebrated as the first British double victory for 25 years, it’s likely to remain the last for (shall we say) the foreseeable future. Round also reached the final a year earlier when she faced (and was defeated by) the great American player Helen Wills Moody. The match swung on a controversial line-call that was initially declared for Round, who graciously asked that the decision be overturned in her opponent’s favour. During the 1930s Bunny Austin struggled to escape the long shadow cast by Fred Perry who dominated the men’s game. Twice a defeated Wimbledon finalist, Austin is now remembered for his elegant and fluid play, debonair personality, and for pioneering men’s wearing of shorts rather than long flannel trousers.

Among the pleasures of tennis biographies are the personal insights they provide into lives away from centre court. Take, for example, Kitty Godfree, the Wimbledon ladies’ champion in 1924 and 1926. A sporty child who also excelled in skating and lacrosse, the nine-year-old Kitty had ‘cycled from London to Berlin as part of a family outing’. Then there are the Doherty brothers who stopped competing at Wimbledon in 1906 in response to their mother’s worries that strenuous matches would damage her sons’ health. Sadly, Mrs Doherty’s fears were grounded as both brothers died from natural causes, Laurie aged 44 and Reggie at 38. Finally, did you know that Fred Perry, son of a Labour MP, first honed his skills not on manicured lawns but at the ping pong tables of the Ealing YMCA? Such was Perry’s talent that he became the table-tennis world champion in 1929, and carried over many of his winning shots to lawn tennis.

Talk of former British champions, seemingly winning at will, shouldn’t get out of hand. If by Week Two things aren’t going to plan, take heart by adopting an alternative perspective. Defeats too can be memorable: those suffered by Dorothy Round in 1933 or by Kay Stammers in the 1938 final remain among Wimbledon’s most celebrated and era-defining matches. Nor, despite the numerous successes of a Doherty, Chambers or Hillyard, was the modern ‘waiting game’ unknown to tennis fans of the early twentieth century. Fred Perry and Bunny Austin’s victory in the 1933 Davis Cup, for instance, followed 21 years in the wilderness. (Coaching the winning team was Dan Maskell who later became the BBC’s ‘voice of Wimbledon’, best known for his ‘Oh I say!’ catchphrase.) Likewise Perry’s win at the US Open in 1930, was the first by a Briton for 30 years. Dorothy Round and Kitty Godfree meanwhile were the only British women to win at Wimbledon between the wars, a period otherwise dominated by France’s Suzanne Lenglen and the Americans, Wills Moody and Helen Jacobs. As we learn at school, history, including tennis history, is continuity as well as change.

Philip Carter is Publication Editor of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography is the national record of men and women who have shaped British history and culture, worldwide, from the Romans to the 21st century. In addition to 58,700 life stories, the ODNB offers a free, twice monthly biography podcast with over 185 life stories now available (including that of Fred Perry). You can also sign up for Life of the Day, a topical biography delivered to your inbox, or follow @odnb on Twitter for people in the news. The Oxford DNB is freely available via public libraries across the UK. Libraries offer ‘remote access’ allowing members to log-on to the complete dictionary, for free, from home (or any other computer) twenty-four hours a day.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only sports articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Dorothea Douglas, Wimbledon and Olympic Games tennis champion. Picture taken in 1903. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Oh, I say! Brits win Wimbledon appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAn ODNB guide to the people of the London 2012 opening ceremonyThe mysteries around Christopher MarloweFive things you might not know about Bobby Moore

Related StoriesAn ODNB guide to the people of the London 2012 opening ceremonyThe mysteries around Christopher MarloweFive things you might not know about Bobby Moore

Does Elton John have a private life?

Do celebrities forfeit their right to privacy? Pop stars, stars of screen, radio, television, sport and the catwalk—are regarded as fair game by the paparazzi. Members of the British Royal family, most conspicuously and tragically the Princess of Wales, have long been preyed upon by the media. More recently, photographs of the Duchess of Cambridge, taken surreptitiously while she was sunbathing at a private villa in Provence, were published online.

It is often claimed that public figures surrender their privacy. This is usually based on one of two arguments. Either it is asserted that celebrities relish publicity when it is favourable, but resent it when it is hostile. They cannot, it is argued, have it both ways. Secondly, it is said that the media have the right to ‘put the record straight.’

The first contention is fallacious. It is based on the idiom: ‘live by the sword, die by the sword.’ But surely the fact that a celebrity courts publicity—an inescapable feature of fame—cannot be allowed to annihilate his or her right to shield intimate features of their lives from public view (an argument accepted by the report of the recent Leveson Inquiry).

Nor is the second argument convincing. Suppose that a footballer were HIV-positive or suffering from cancer. Can it really be right that a legitimate desire on his part to deny that he is a sufferer of one of these diseases may be annihilated by the media’s right to ‘put the record straight’? If so, the protection of privacy is a fragile reed. Truth or falsity should not block the expectation of those who dwell in the glare of public attention.

Nor is the second argument convincing. Suppose that a footballer were HIV-positive or suffering from cancer. Can it really be right that a legitimate desire on his part to deny that he is a sufferer of one of these diseases may be annihilated by the media’s right to ‘put the record straight’? If so, the protection of privacy is a fragile reed. Truth or falsity should not block the expectation of those who dwell in the glare of public attention.

The courts are often faced with complex, always contested, factual, philosophical, and legal issues that are not always easy to resolve. English judges must strike a balance between the competing rights of victim and media. Since the enactment of the Human Rights Act 1998, they have devised a number of tests in pursuit of this invariably contentious equilibrium between Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (which refers to ‘respect for private and family life …’), and Article 10 (which protects freedom of expression).

In the case of Naomi Campbell the newspaper had, along with a photograph of her leaving a meeting of Narcotics Anonymous (NA) in a public place with other drug addicts, published the fact that she was an addict for which she had attended NA for some time. Elton John, on the other hand, the court decided had no reasonable expectation of privacy when he was photographed outside his home sporting a tracksuit and baseball cap.

Are the media entitled to ‘put the record straight? Superstars and supermodels attract little sympathy when they complain of media intrusion. They bask in the glory of favourable publicity; they cannot therefore legitimately protest when a disclosure reveals them in a less than satisfactory light. But this simple judgment neglects the principal purpose of the legal protection of personal information against its gratuitous disclosure.

A moment’s thought reveals how misconceived this argument is. When celebrities object to unsolicited disclosures of their personal information, their complaint is not that they have attracted negative ‘publicity,’ but that their privacy has been violated. There is, in other words, an important—and widely overlooked—distinction between the revelations of one’s intimate or sensitive information, on the one hand, and publicity about, say, a pop star, on the other.

There is, of course, even less sympathy for public figures that dissemble. Indeed, Naomi Campbell conceded at trial that because she had lied about her drug addiction, the media had a right to put the record straight. There is a public interest in the media revealing the truth. She was, the court held ‘ a well-known figure who courts rather than shuns publicity, described as a role model for other young women, who had consistently lied about her drug addiction and compared herself favourably with others in the fashion business who were regular users of drugs. By these actions she had forfeited the protection to which she would otherwise have been entitled and made the information about her addiction and treatment a matter of legitimate public comment on which the press were entitled to put the record straight.’

Can this be correct? Perhaps it is only in circumstances where the public figure has exhibited a degree of gross hypocrisy or mendacity that the media has exposed.

Should it matter that the victim is a ‘role model’? The argument is similar to the claim that the media have a right to put the record straight. Why should an individual, whether or not he or she happens to be a celebrity, forfeit Article 8 protection on the ground that those who regard such personsare ‘let down’ by their behaviour? Is it really ‘self-evident’, as one senior judge put it, that a famous footballer’s activities off the field have ‘a modicum of public interest … [because they] are role models for young people and undesirable behaviour on their part can set an unfortunate example’?

Several other similar cases have arisen before the courts. While there is always a delicate balance to be struck, the two most common contentions deployed against celebrities (however much we may revile them) cut little ice. Elton should be treated no differently from his many fans.

Raymond Wacks is Emeritus Professor of Law and Legal Theory. He has published numerous articles on various aspects of law and jurisprudence in leading scholarly journals and his books include Understanding Jurisprudence: An Introduction to Legal Theory (3rd ed, 2012), Philosophy of Law: A Very Short Introduction (2006), and Law: A Very Short Introduction (2008). Professor Wacks has been a leading authority on the legal protection of privacy for almost four decades. His major works in this field are The Protection of Privacy, the first book on the subject in England (1980); Personal Information: Privacy and the Law (1989); Privacy, a two-volume collection of essays (1993); Privacy and Press Freedom (1995) and Privacy: A Very Short Introduction (2010). Professor Wacks is a former chairman of the privacy committee of the Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong, and was a member of the statutory Personal Data (Privacy) Advisory Committee.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: By Richard Mushet on Flickr [Creative Commons Licence] via Wikimedia Commons

The post Does Elton John have a private life? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe highest dictionary in the land?The end of ownershipWhen in Rome, swear as the Romans do

Related StoriesThe highest dictionary in the land?The end of ownershipWhen in Rome, swear as the Romans do

June 23, 2013

When in Rome, swear as the Romans do

What’s the meaning of the word irrumatio? In Ancient Rome, to threaten another individual with irrumatio qualified as one of the highest offenses, topping off a list of seemingly frivolous obscenities that — needless to say — did not survive into the modern era. Instead, shifting cultural taboos from century to century produced an ever-changing assortment of swear words, with varying sexual, religious, and racial connotations. Melissa Mohr, author of Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing, examines one of our timeless guilty pleasures and demonstrates the usefulness of linguistic obscenity in order to “express emotion, whether that emotion is negative or positive, offer catharsis as a response to pain or powerful feelings, [and] cement ties among members of groups in ways that other words cannot.”

Click here to view the embedded video.

Melissa Mohr received a Ph.D. in English Literature from Stanford University, specializing in Medieval and Renaissance literature. Her most recent book is Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post When in Rome, swear as the Romans do appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow come the past of ‘go’ is ‘went?’Monthly etymology gleanings for January 2013, part 1‘Guests’ and ‘hosts’

Related StoriesHow come the past of ‘go’ is ‘went?’Monthly etymology gleanings for January 2013, part 1‘Guests’ and ‘hosts’

The highest dictionary in the land?

Perhaps the highest-profile cases to be decided by the US Supreme Court this term are the two involving the definition of marriage. US v. Windsor challenges the federal definition of marriage as “a legal union between one man and one woman” (Defense of Marriage Act [DOMA], 1 USC § 7), and Hollingsworth v. Perry seeks a ruling on the constitutionality of California’s Proposition 8, a ban on same-sex marriage which reads, “Only marriage between a man and a woman is valid or recognized in California.” Both cases concern who gets to write the definition of marriage, and what that definition says. The high court may check dictionary definitions in deciding these cases. It could defer to state laws defining marriage. Or it could simply write its own definition of marriage, because courts, like dictionaries, are in the business of telling us what words mean. The highest court in the land is poised to become the highest dictionary in the land.

Judges, like the rest of us, turn to dictionaries when they’re not sure about the meaning of a word. Or they turn to dictionaries when they’re sure about a word’s meaning, but they need some confirmation. Or they turn to a dictionary that defines a word the way they want it defined, rejecting as irrelevant, inadmissible, and immaterial any definitions they don’t like.

The Supreme Court has referred to dictionaries in its opinions over 664 times. In recent years, almost every major case and many minor ones find the justices, or their clerks, thumbing throughWebster’s Third or the Oxford English Dictionary. And it’s not just high-profile cases like District of Columbia v. Heller, the one about the Second Amendment, where definitions of words like militia and bear arms came into play. While he was writing an opinion in a patent case, Chief Justice John Roberts looked up words in five different dictionaries. When was the last time you looked up a word in more than one dictionary?

Sometimes even five dictionaries aren’t enough. In Taniguchi v. Kan Pacific Saipan (2012), Justice Samuel Alito checked ten dictionaries to prove that the word interpreter refers to someone who translates speech, not writing, and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg found four dictionaries supporting her view that interpreter can refer to a translator of documents as well. Complicating things even more, both justices relied on the same definitions of interpreter in Webster’s Third and Black’s Law Dictionary to support their opposing claims. It turns out that dictionary definitions need interpreting, just as the law does.

Why all this consulting of dictionaries by the courts? When a word is not defined in a statute, legal convention says that we’re supposed to give that word its ordinary, customary, or plain meaning. But the ‘ordinary meaning’ of words is often in dispute: the recent case of Bullock v. BankChampaign (2013) turned on the meaning of defalcation, an obscure accounting term that has no plain meaning. But the meaning of more common words is often also up for grabs. That’s why as many as 15 or 16 million civil lawsuits are filed every year, all of them based on conflicting interpretations of the words in our laws and contracts.

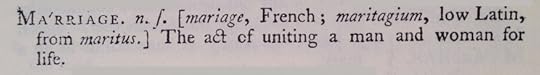

If the marriage-equality cases before the Court lead to dictionary look-ups, here’s what the justices will find. Samuel Johnson (1755), the great English lexicographer, defines marriage as “the act of uniting a man and woman for life.” Noah Webster (1828), a lawyer by training, defines marriage as a specifically heterosexual union and moralizes at length about its religious virtues, something today’s more modest lexicographers refrain from doing:

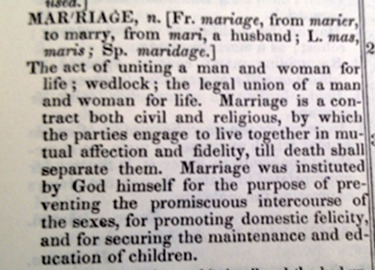

Marriage. n. s. The act of uniting a man and woman for life; wedlock; the legal union of a man and woman for life. Marriage is a contract both civil and religious, by which the parties engage to live together in mutual affection and fidelity, till death shall separate them. Marriage was instituted by God himself for the purpose of preventing the promiscuous intercourse of the sexes, for promoting domestic felicity, and for securing the maintenance and education of children.

Samuel Johnson’s definition, from his Dictionary of the English Language (1755), via Dennis Baron.

Noah Webster’s definition, from An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828), via Dennis Baron.

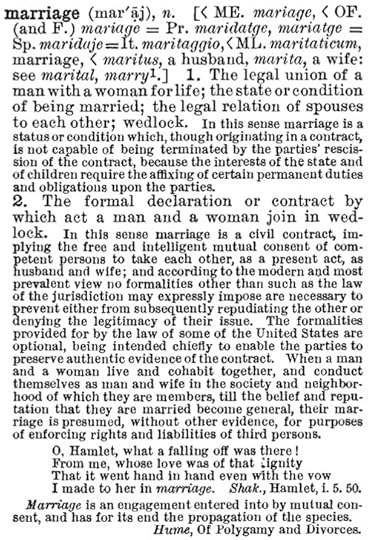

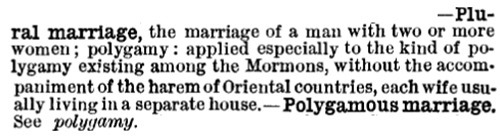

The Century Dictionary (1891), the first to be based on scientific and linguistic principles, stresses the civil nature of marriage as “the legal union of a man with a woman for life”–nothing shocking there. But it’s also the first dictionary to recognize that marriage is defined differently in different cultures. Marriage may include both common law marriage and “plural marriage,” or polygamy (not just abroad, the Century tells us, but even in the United States, as practiced by Mormons).

The Century Dictionary defines marriage as heterosexual, but its definition takes an anthropological bent, recognizing the fluidity of wedlock practices across cultures, via Dennis Baron.

The Century also has an entry defining plural marriage, both “among the Mormons” and in “Oriental countries” (a reference not to the Far East, but to Islam), via Dennis Baron.

In contrast to the moralizing Webster, Black’s Law Dictionary (2nd ed., 1910), confirms earlier definitions specifying heterosexual monogamy, but grounds the institution in civil law rather than religion:

Marriage . . . is the civil status of one man and one woman united in law for life, for the discharge to each other and the community of the duties legally incumbent on those whose association is founded on the distinction of sex.

But the latest edition of Black’s (9e) gives this more-neutral definition, “the legal union of a couple as spouses,” and a subentry for same-sex marriage refines the definition to take into account its treatment in various jurisdictions:

The ceremonial union of two people of the same sex; a marriage or marriage-like relationship between two women or two men .• The United States government and most American states do not recognize same-sex marriages, even if legally contracted in other countries such as Canada, so couples usu. do not acquire the legal status of spouses. But in some states same-sex couples have successfully challenged the laws against same-sex marriage on constitutional grounds.

In 2003, Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary (11e), an authority frequently cited by the courts, added same-sex unions to its definition of marriage:

1a (1) the state of being united to a person of the opposite sex as husband or wife in a consensual and contractual relationship recognized by law (2): the state of being united to a person of the same sex in a relationship like that of a traditional marriage.

The Oxford English Dictionary, another favorite with judges, has also added same-sex marriage to its definition:

persons married to each other; matrimony. The term is now sometimes used with reference to long-term relationships between partners of the same sex.

The OED also adds this definition of gay marriage (s.v., gay), tracing the first use of the term back to 1971:

gay marriage n. relationship or bond between partners of the same sex which is likened to that between a married man and woman; (in later use chiefly) a formal marriage bond contracted between two people of the same sex, often conferring legal rights; (also) the action of entering into such a relationship; the condition of marriage between partners of the same sex.

And in 2011, the American Heritage Dictionary (5e) added both same-sex marriage and polygamy to its definition of marriage:

a. The legal union of a man and woman as husband and wife, and in some jurisdictions, between two persons of the same sex, usually entailing legal obligations of each person to the other.

b. A similar union of more than two people; a polygamous marriage.

c. A union between persons that is recognized by custom or religious tradition as a marriage.

d. A common-law marriage.

Dictionaries have modified their definitions of marriage as social attitudes toward marriage have changed. That’s because dictionaries record how speakers and writers have used some words some of the time in some contexts. The new definitions of marriage may help the Court decide its current cases. But it’s also possible that the Court will ignore them, because, despite our reverence for dictionaries as the ultimate language authorities, lexicographers don’t write dictionaries with the law in mind.

The courts are coming to realize this, if only slowly. In U.S. v. Costello, Judge Richard Posner rejected the government’s dictionary-definition of to harbor as ‘to shelter’ (Costello had been convicted of “harboring” her partner, a convicted drug dealer and illegal alien, in violation of the Espionage Act): “‘Sheltering’ doesn’t seem the right word for letting your boyfriend live with you.” Quoting Learned Hand, he admonished the government attorneys “not to make a fortress out of the dictionary,” because dictionaries don’t generally give enough information about how a word is used in context. Instead, Posner sought the meaning of harbor by googling the word.

The Supreme Court may be moving away from its reliance on dictionaries as well. In Bullock, the Court was asked to decide if defalcation, which means a reduction in the funds in an account, can be accidental, or if it must require criminal intent. Legal precedents and jurisprudence don’t supply a clear answer to the question of intent. Turning to lexicographical authorities, Justice Stephen Breyer found that “definitions of the term in modern and older dictionaries are unhelpful,” some suggesting defalcation is criminal, others that it’s not, and still others that can be either innocent or criminal. So the Court wrote its own definition: because defalcation occurs in the same sentence of the Bankruptcy Act as fraud, embezzlement, and larceny, Breyer reasoned that, like these other terms, defalcation must require criminal knowledge or intent. And that is how the highest court now defines the word.

The Supreme Court’s definitions are confined to legal contexts. We are still free to call translators of documents interpreters, but after Taniguchi, the law must define them as translators of speech. We can use defalcation to mean the accidental loss of funds, as when Uncle Billy misplaces the bank deposit in It’s a Wonderful Life—if we think of this unusual word at all. And we can still think that in the Second Amendment, bearing arms refers to military service, not sport or self-defense, but after Heller, it became grammatical to bear arms against a rabbit too.

The Supreme Court may choose not to define marriage at all–we’ll know more soon. But if it does rule that marriage includes same-sex marriage, or excludes it, no matter how we define marriage privately, we’ll have to follow those definitions in dealing with the legal aspects of marriage, at least until the Court changes its mind and rewrites its dictionary.

Dennis Baron is Professor of English and Linguistics at the University of Illinois. His book, A Better Pencil: Readers, Writers, and the Digital Revolution, looks at the evolution of communication technology, from pencils to pixels. You can view his previous OUPblog posts or read more on his personal site, The Web of Language, where a version of this article originally appeared. Until next time, keep up with Professor Baron on Twitter: @DrGrammar.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The highest dictionary in the land? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe end of ownershipExclusion and the LGBT life coursePlebgate

Related StoriesThe end of ownershipExclusion and the LGBT life coursePlebgate

The Bible and the American Revolution

Was the American Revolution more of a religious war than we thought? The Bible had a powerful influence in a land that was originally established as a haven for Protestant freedom. As seen in these examples taken from James P. Byrd’s Sacred Scripture, Sacred War: The Bible and the American Revolution, notable men in history frequently referenced Christian faith to help justify their patriotism and ultimately, war.

John Lathrop

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

John Adams

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Alexander Hamilton

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

George Washington

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Nathan Perkins

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

');

');tid('spinner').style.visibility = 'visible';

var sgpro_slideshow = new TINY.sgpro_slideshow("sgpro_slideshow");

jQuery(document).ready(function($) {

// set a timeout before launching the sgpro_slideshow

window.setTimeout(function() {

sgpro_slideshow.slidearray = jsSlideshow;

sgpro_slideshow.auto = 0;

sgpro_slideshow.nolink = 0;

sgpro_slideshow.nolinkpage = 1;

sgpro_slideshow.pagelink="self";

sgpro_slideshow.speed = 10;

sgpro_slideshow.imgSpeed = 10;

sgpro_slideshow.navOpacity = 25;

sgpro_slideshow.navHover = 70;

sgpro_slideshow.letterbox = "#000000";

sgpro_slideshow.info = "information";

sgpro_slideshow.infoShow = "S";

sgpro_slideshow.infoSpeed = 10;

// sgpro_slideshow.transition = F;

sgpro_slideshow.left = "slideleft";

sgpro_slideshow.wrap = "slideshow-wrapper";

sgpro_slideshow.widecenter = 1;

sgpro_slideshow.right = "slideright";

sgpro_slideshow.link = "linkhover";

sgpro_slideshow.gallery = "post-44241";

sgpro_slideshow.thumbs = "";

sgpro_slideshow.thumbOpacity = 70;

sgpro_slideshow.thumbHeight = 75;

// sgpro_slideshow.scrollSpeed = 5;

sgpro_slideshow.scrollSpeed = 0;

sgpro_slideshow.spacing = 5;

sgpro_slideshow.active = "#FFFFFF";

sgpro_slideshow.imagesbox = "thickbox";

jQuery("#spinner").remove();

sgpro_slideshow.init("sgpro_slideshow","sgpro_image","imgprev","imgnext","imglink");

}, 1000);

tid('slideshow-wrapper').style.visibility = 'visible';

});

On some occasions, conviction in the Bible led to fool-hardiness. Before the American Revolution, soldier Goodman Wright fought in King Philip’s War. Wright believed even just holding the Bible protected him from harm, which he would quickly discover was not the case when he was slaughtered and had the book stuffed inside of him by the enemy.

However, Christian faith still inspired some of the most powerful men in American history to ultimately succeed in achieving independence and leave behind a passionate legacy.

Kate Pais joined Oxford University Press in April 2013. She works as a marketing assistant in the Academic/Trade division for the history, religion and theology, and bibles lists.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only Religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Portrait of John Lathrop, 1852. From Chandler Robbins. A history of the Second Church, or Old North, in Boston: to which is added a History of the New Brick Church. Boston: John Wilson & Son, 1852. Artist Unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) John Adams, Second President of the US., 1823-24. Painting by Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) A portrait of Alexander Hamilton painted by noted American portrait painter Daniel Huntington in c.1865, based on a full length portrait painted by John Trumbull. U.S. Treasury Collection, Secretary of the Treasury Portraits., 1865. From the US Treasury. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (4) George Washington, 1795-1796, 1795-1796. From Art in The Frick Collection: Paintings, Sculpture, Decorative Arts, New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (5) >First Church of Christ (Congregational), Main Street, between School & Church Streets, Hartford County, CT. Created by Jack E. Boucher. Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American Landscapes Survey.

The post The Bible and the American Revolution appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesReligious, political, spiritual—something in common after all?Remembering the doughboysThe History of the World: Nazis attack the USSR (‘Operation Barbarossa’)

Related StoriesReligious, political, spiritual—something in common after all?Remembering the doughboysThe History of the World: Nazis attack the USSR (‘Operation Barbarossa’)

June 22, 2013

How will a changing global landscape affect health care providers?

Health care is expanding its reach in many directions. Globalization is increasingly allowing patients throughout the world to access all types of health care from anywhere in the world. Between the growth in medical tourism, medical missions service, international education, and the increasing intersection of western medicine into eastern culture and eastern medicine into western culture, individuals have vaster array of choices to preserve their health than ever before. At the same time, the trend of specialized urban medical centers extending their facilities to reach small, localized patient populations in response to patient demands for convenience, and the development of enhanced telemedicine capabilities, have allowed more patients to remain local while obtaining cutting edge health care, than ever before. The population around the world is becoming better educated and, thus, more interested in exploring personal health care options. Up to date information is available to a growing percentage of the world’s healthy and sick as a consequence of improved technology and communication channels.

Image credit: Photo by Carol Garcia / SECOM, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

How do all of these developments affect health care providers? More and more doctors, dentists, nurses, therapists and pharmacists are becoming important players in the currently emerging divergent trends of both wide spanning globalization and localization in health care. Health care providers are responding to the many exciting changes in the health care atmosphere by becoming skilled at improved ways to deliver health care and learning how to advance health care as a whole. Globalization and localization are affecting our current time, making it a key time in history for knowledgeable doctors and all health care providers who can use their skills and background in non-traditional ways to respond to the expanding demands in the health care field.

When innovation becomes available, individuals demand the services immediately. Yet the providers who deliver these services continue to spend years meticulously evaluating the effectiveness, the benefits, the drawbacks, and the best ways to enhance integration of new ways with old. Many providers relish the opportunity to become part of new developments early on, even prior to regulatory stability. Early adopters of the latest advances can play a principal role in directing the prevailing guidelines as they develop. Health care providers must be prepared to adapt to globalization and localization in health care delivery. And, while adapting is critical, it is even more advantageous to anticipate emerging trends and to play a fundamental role in moving medical care in a positive direction.

Heidi Moawad MD is author of Careers Beyond Clinical Medicine, a resource for health care professionals who are interested in improving the health care system. Dr. Moawad teaches at John Carroll University in University Heights, Ohio and in a recipient of The McGregor Course Development Grant Award in Globalization Studies.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post How will a changing global landscape affect health care providers? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow can you reduce pain during a hospital stay?Making sense with data visualisationWhen is a question a question?

Related StoriesHow can you reduce pain during a hospital stay?Making sense with data visualisationWhen is a question a question?

Remembering the doughboys

Ninety-six years ago today, on 26 June 1917, over 14,000 American soldiers disembarked at the port of St. Nazaire on the western coast of France. They were the initial members of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), the United States’ contribution to the First World War. As America approaches the centennial of World War I, will it remember the doughboys? For their sake—and for ours—we should.

That there would be soldiers in Europe so soon—or soldiers at all—surprised both American military planners and their European counterparts. Battle had been underway for two and a half years when the United States declared war on Germany on 6 April 1917. The US Regular Army then included just 128,000 men, and the Germans gambled that American troops would not reach the front in time to make a difference. The French, by contrast, desperately hoped that they would, particularly after a failed military offensive that spring provoked mass mutinies in the French army. President Woodrow Wilson agreed with French military officers that the immediate arrival of even a token force would have “an enormously stimulating effect in France.”

Meeting the AEF at the docks that day was their commanding officer, John J. Pershing, plucked from a military campaign along the Mexican border and dispatched to Europe after just a single meeting at the White House with Woodrow Wilson. There, on May 24, 1917, Wilson and his Secretary of War Newton Baker gave Pershing little guidance on how to conduct the war other than to insist that the AEF’s separate identity “must be preserved.” The Americans would fight as an “associated” power rather than an ally, lest the doughboys become cannon fodder for French or British generals.

America’s answer. The second official United States war picture (1918). Courtesy of Library of Congress

Who were the first doughboys? While many were hardened career soldiers from the Army or Marines, Pershing kept some of the best at home to train the raw recruits that the recently-adopted Selective Service Act was about to send to military camps. At least half the men assembled into the Army’s new 1st Division had joined up after the declaration of war, arriving in France with just six or eight weeks’ training. They made a poor first impression. One soldier thought his companions were “less impressive than any other outfit I have ever seen.” The young captain George Marshall found the men embarrassingly ill-trained, badly dressed, and poorly behaved. Pershing, aware of the soldiers’ weaknesses, charitably called them “sturdy rookies.” Pershing was right.

Five hundred of the men who disembarked in France that day were African American stevedores, contractors hired to unload the American ships. Their work was the sign of things to come, as many of the 380,000 black soldiers who later served in France found themselves relegated to secondary service roles and labor battalions. But at St. Nazaire they also mingled with French colonial soldiers from West Africa and the Caribbean; postwar global movements for racial equality were forged on those Atlantic docks.

Many of the soldiers who arrived at St. Nazaire that June remembered the town as eerily silent. “Every woman seemed to be in mourning,” George Marshall recalled. “The one thing we noticed most of all there was no enthusiasm at all over our arrival.” French children and war widows watched quietly, hesitatingly wondering what the AEF’s arrival might portend. Pershing had noticed the same trepidation at the highest levels of the French Army: at a dinner with his counterpart Philippe Pétain, the French general fell into a silent funk, looked up and muttered, “I hope it is not too late.”

Petain and Pershing during World War I. Bain News Service. Image courtesy of Library of Congress.

It wasn’t. In just 19 months, more than two million American men and women would serve in France, where they played a crucial role in the war’s final stages. Not least of all by shoring up their allies’ morale, a change noticeable just days after the landing at St. Nazaire, as a contingent of the 16th Infantry marched through Paris in a hastily arranged July Fourth parade. Greeted as heroes, they made a pilgrimage to Lafayette’s tomb, where Pershing—never much of a public speaker—asked a French-speaking fellow officer to say a few words in honor of the French soldier who had come to America’s aid during its Revolution more than a century before. Charles Stanton provided one of the war’s most memorable lines: “Lafayette, we are here!”

The soldiers of the AEF have faded from view, America’s first world war overshadowed by its second. On 16 January this year, the U.S. government grudgingly established a World War I centennial commission, insisting that it receive no taxpayer dollars. But as Americans continue to grapple with their role in the world today, it would be worth pausing to remember the history made at St. Nazaire by the first doughboys. We owe those “sturdy rookies” nothing less.

Christopher Capozzola is Associate Professor of History at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the author of Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Remembering the doughboys appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe History of the World: Nazis attack the USSR (‘Operation Barbarossa’)OHR signing off (temporarily!)The end of ownership

Related StoriesThe History of the World: Nazis attack the USSR (‘Operation Barbarossa’)OHR signing off (temporarily!)The end of ownership

Making sense with data visualisation

Statistics to me has always been about trying to make the best sense of incomplete information and having some feeling for how good that ‘best sense’ is. At a very crude level if you have a firm employing 235 people and you randomly sample 200 of these on some topic, I would feel my information was pretty good (even though it is incomplete). If the information I have is based on a sample of five people or I have asked all the people in one office, then I would know my information was nothing like as good as in the former case.

More than ever, in the current International Year of Statistics, there is an acceptance that understanding quantitative information is a necessary skill in almost any academic discipline and in almost all professional jobs (and very many jobs at lower levels). Statistics is used wide range of contexts such as physical, life and social sciences, sports, marketing, finance, geography, and psychology. In fact it’s used anywhere there is interesting data, and with supporting visual explanations of what is happening in various statistical techniques, it need not be an intimidating area to be involved in.

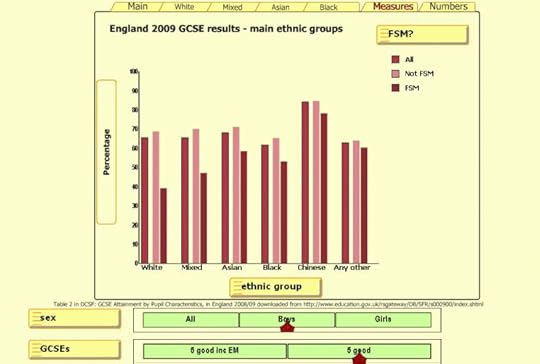

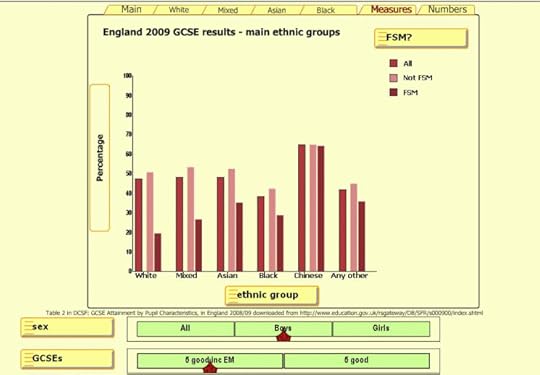

I am currently doing some work at Durham on data visualisation, including on education performance data, the 2011 UK riots, and health. For example, interactive data resources show the proportions of pupils gaining five good GCSEs (with and without a requirement to include English and Maths), disaggregated by sex, ethnicity and whether they are eligible for free school meals. The first screen shot shows boys’ performance rates for various ethnic groups and how eligibility for free school meals varies across ethnic groups. You can see it’s very dramatic in both white and mixed groups, and much more modest for asian, black and other groups, and almost non-existent for the Chinese. The second screen shot shows how the display changes if the bottom slider is moved to change the performance measure to remove the requirement for English and Maths. The position of the variables can be moved (just drag and drop) to different positions to allow other comparisons to be made directly, and to develop a real sense of the stories in the data.

It would be much more logical if social scientists wanting to put forward theoretical explanations for inequalities in health, in education, in crime etc., were able to explore the data actively in an interface like this – to develop a rich picture of the relationships between factors, which are important and which less so, where particular combinations of factors give unexpected outcomes – and then to try to provide theory which is consistent with the observed patterns of behaviour.

Additionally, I have just started working on a new project working on visualisations of 2011 UK Census data and with Imperial College Reach Out Lab on supporting data sharing in science. Essentially there is a Pratice Transfer Partnership of HE Reach Out Labs where we are trying to develop experiments with more variables that different institutions will collaborate on to bulld a large multi-variate data set which students and teachers would then have access to embedded in our visualisation tools. The ambition is to tie more mathematics in with authentic scientific enquiry, so the collaboration between Science and Mathematics is something with real potential in making mathematics and statistics more directly and obviously relevant to students.

James Nicholson is the author of Statistics S1 and Statistics S2 in the A Level Mathematics for Edexcel course published by Oxford University Press. He is also Principal Research Fellow at the SMART Centre at Durham University.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only mathematics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Graphs created by James Nicholson. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

The post Making sense with data visualisation appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat’s the Problem with Maths?Omar is no OzzieWhen is a question a question?

Related StoriesWhat’s the Problem with Maths?Omar is no OzzieWhen is a question a question?

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers