Oxford University Press's Blog, page 935

June 13, 2013

Letters from your father

By David Roberts

You’re a shy boy — inclined to blurt, shuffle and look at the floor — and you can tell from your father’s efforts on your behalf that he’s concerned. That makes things a lot worse.

From an early age, the private tutors crowd in. You’re sent away to study. When you’ve grown up a bit, the old man fixes you up with a grand tour of European capitals, opening doors into an old boys’ network of continental proportions. Reports of your improvement are, you suspect, inconsistently encouraging. You’re just too ill at ease to cope.

Still, with a quiet word here and less gentle persuasion there, he fixes you up with a seat in the Commons. Another lucky break, but it’s agony. When you give your maiden speech the other members can hardly believe it: an MP who can barely summon words for his big occasion. So father tries again, and a succession of German court appointments follows.

All this time, in fact for a period of over 30 years, he is pursuing another tack, desperate for you to attain the eminence of his own career as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Ambassador at The Hague, and His Majesty’s Secretary of State. His weapon? Letters: hundreds of them, full of worldly advice, suggestions about proper language, deportment, manners, diplomacy, politics, reading, society, relationships…

But for all their advice, the letters pray on your sense of inadequacy. He gets reports from friends of your conduct:

In company you were frequently most provokingly inattentive, absent, and distrait…you came into a room and presented yourself very awkwardly…at table you constantly threw down knives, forks, napkins, bread, etc., and…neglected your person and dress, to a degree unpardonable at any age, and much more so at yours.

His elegant comparisons tie you in knots of practical uncertainty:

Were you to converse with a King, you ought to be as easy and unembarrassed as with your own valet-de-chambre; but yet every look, word, and action, should imply the utmost respect.

Not content with an easy manner and confident knowledge, he demands a regime of exercise:

I hope you do not neglect your exercises of riding, fencing and dancing, but particularly the latter.

When he chooses, he can be straightforwardly brutal:

My object is to have you fit to live; which, if you are not, I do not desire that you should live at all.

What makes it all much worse is that you know you will never succeed not because your manner is gauche, your speech inelegant and your habits erratic. No: you are doomed to disappoint your father because of the way he fathered you. You are his son, but your mother is not his wife. Some opportunities are simply closed to you. He refuses to give up, of course. He may express sympathy with the villains of literature — with Turnus in The Aeneid or even Satan in Paradise Lost — but all the connections in Europe cannot unmake the prejudice against you. He is Sisyphus, pushing at the impossible boulder.

You have no choice but to make your own way in the world. Accept his fatherly patronage, his advice, his legion letters, but play your own game. Read his counsel about making a good match — as if the circumstances of your birth allowed — but make your own decisions. Do what he did to make you: fall in love. Find your own bride, regardless of station or convention. Have a family. Whatever you do, don’t tell him. You’re in Europe and he’s in London; he’ll never know.

But when you die young of a fever in Avignon, it turns out you underestimated him. Yes, he is shocked. No, he cannot believe that the son he had nurtured could have deceived him so, or married so far beneath the family dignity. He is alarmed to find he is, twice over, a grandfather. But his fatherly instinct revives. He provides generously for your grieving wife and begins his great project of education all over again with an allowance for your sons. Among all his words of advice, all his homilies to courtly conduct, perhaps the effortlessly civilised mind of Philip Dormer Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield, keeps returning to the last sentence of the last letter he wrote to you:

God bless, and grant you a speedy recovery.

Professor David Roberts teaches English Literature at Birmingham City University. He has taught at the universities of Bristol, Oxford, Kyoto, Osaka, and Worcester, and in 2008/09 he was the inaugural holder of the John Henry Newman Chair at Newman University College, Birmingham. He has published extensively in the fields of seventeenth and eighteenth century drama and literature, and is the editor of the Oxford World’s Classics edition of Lord Chesterfield’s Letters, as well as Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year. He has previously written about Daniel Defore in London and about disaster writing for OUPblog.

Praised in their day as a complete manual of education, and despised by Samuel Johnson for teaching `the morals of a whore and the manners of a dancing-master’, Lord Chesterfield’s Letters reflect the political craft of a leading statesman and the urbane wit of a man who associated with Pope, Addison, and Swift. The letters reveal Chesterfield’s political cynicism and his belief that his country had `always been goverened by the only two or three people, out of two or three millions, totally incapable of governing’, as well as his views on good breeding. Not originally intended for publication, this entertaining correspondence illuminates fascinating aspects of eighteenth-century life and manners.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Portrait of Philip Dormer Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield, by unknown artist [public domain]. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Letters from your father appeared first on OUPblog.

June 12, 2013

Multifarious devils, part 3. “Pumpernickel,” “Nickel,” and “Old Nick”

Although a German word, Pumpernickel (which in what follows will not be capitalized) seems to be sufficiently familiar to the English-speaking world not to require a gloss. The origin of the bread (Westphalia, and there perhaps the town of Osnabrücken) has been ascertained, but the etymology of the name remains a puzzle—at least to some extent. It would have been almost impossible to collect the countless publications on this word without an exhaustive survey by Kurt Ranke (1954), an outstanding folklorist and dyed-in-the wool Nazi, a scholar who returned to a university career shortly after the war and was embraced by academia with open arms. Too bad, talented people so often turn out to be scoundrels. Those who know enough about the career of Jan de Vries, a great Dutch Germanist, will agree.

All the earlier attempts to trace pumpernickel to its etymon failed because they assumed that everything had begun with the name of the bread. Ranke showed that this idea was wrong. Carin Gentner, who brought out her investigation on pumpernickel in 1987, two years after Ranke’s death, mentioned her illustrious predecessor in passing, but her material and conclusions contain little that is new. Documents show that pumpernickel has been attested with many senses: “different kinds of bread,” “a short fat man (or child),” part of the phrase connected with the custom of ‘singing Pumpernickel’ (the meaning of the phrase is no longer clear, but the reference is to something unconventional and often obscene; sometimes fisticuffs and the like are at the center), and “the hero of a children’s song about someone called Pumpernickel” (he is often in trouble and becomes everybody’s laughingstock). Westphalia is situated in the north of Germany, but the word pumpernickel and the character bearing this name have been recorded all over the country, including its southernmost regions.

In popular literature, one can read fanciful explanations about how the word pumpernickel came about. Most of them center on some episode in the history of the heavy bread made with coarsely ground rye: either a French soldier expressed his disgust of the food a Westphalian peasant offered him, or a kind-hearted bishop fed his starving flock with it. But, as noted, pumpernickel is not tied to the Osnabrücken region. Besides, the name does not always designate course bread. In Vienna, the well-known Lebkuchen is called this; it resembles gingerbread and is a Christmas treat baked with almonds. The word made its way into several countries outside the German speaking world, including France, and its foreign offspring are neither heavy nor coarse. No mention of pumpernickel in published sources predates the beginning of the seventeenth century. The word also occurs as pompernickel and bombernickel, but both are phonetic variants of pumpernickel and add nothing to our search.

Of real importance is the fact that already in the first third of the seventeenth century Pumpernickel sometimes meant “devil.” The name as applied to Westphalian bread appeared in documents and books some time (though not considerably) later, and perhaps the short chronological gap reflects reality: first the devil (a rather than the devil), then “devilish” bread. Despite the general uncertainty surrounding the derivation of pumpernickel, the origin of the first element poses no difficulties. In the post on bogey, I listed some b-g and p-g words that denote swelling, a noisy explosion, and so forth. Bomb and pomp were among them. Pump, pamper, and even pimp belong there too. A pimp (like the German Pimpf) was a youngster, a weakling unable to produce a big pumpf, that is, fart. Pamper refers to stuffing one with food (hence spoiling). Pumper-, as has been known for a long time, carries the same connotations. Despite the occurrence of the word from Osnabrücken to Vienna, it must have been coined in the north, for otherwise it would have had pf in place of p, at least after m. Whoever Pumpernickel was, he must have been able to produce a lot of noise, probably by breaking wind, though it is not improbable that he, like Bogey, deafened people in some other way.

Pumpernickel emerges as a vulgar clown, a prankster, the hero of drunks and whores, a figure typical of low popular culture, like Til Eulenspiegel, the protagonist of scatological tales, Richard Strauss’s symphony piece, and Charles de Coster’s magnificent prose epic. Less clear is the origin of -nickel. German etymologists are reticent on this point, but most probably we find ourselves in the presence of our friend Old Nick. As Charles P. G. Scott pointed out, in English, Nick is an abbreviation of Nicol. There indeed was a devil bearing this name.

Here the metal nickel provides some help. The history of nickel is known. In 1754 Swedish mineralogist Axel F. von Cronstedt obtained an ore he called Kupfernickel (Kupfer “copper”) and shortened it to nickel because it yielded no ore despite its appearance. The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology calls nickel a dwarf, a mischievous demon. The German etymological dictionary by Kluge-Mitzka clarifies the situation: “The name Nikolaus often became a term of abuse, especially in eastern Germany.” Let us not miss the formulation: “…the name Nikolaus,” not “the name of St. Nikolaus.” (The etymology of the metals cobalt and wolfram is similar to that of nickel.)

The word pumpernickel gained great popularity during the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648), which, quite appropriately for our subject, ended after peace treaties were signed in Osnabrücken and Münster. By that time most of Europe lay in ruins. The only good result of the war was the spread of the word pumpernickel, evidently from the “coarse” language of soldiers. They seem to have sworn by Nickel and mentioned him all the time. Just why he rather than somebody else became so prominent (given an abundance of competitors) will hardly ever become known. It could have been Tom, or Harry, or Dick (the last two would have done especially well). The bread soldiers ate in the seventeenth century was indeed heavy and produced more than one “Pumpf,” or great flatulence (to use a polite, sufficiently Latinized word). It deserved being called “fart Nickel.”

And here comes my hypothesis. It did not occur to others because they did not realize that Old Nick was a sibling of Nickel. This is what I meant when I said that etymologists never know enough. I believe that mercenaries and those who accompanied the troops made the petty devil Nickel also famous in England. It cannot be fortuitous that Old Nick and pumpernickel are such close contemporaries in the two countries. I suggest that Nick in Old Nick is a borrowing from German. If my conclusion is right, then Old Nick has no roots in medieval European folklore. St. Nicholas (our Santa Klaus) need not worry about his disreputable namesake (unless someone succeeds in showing that there is a connection between them after all). The Old Germanic crocodile (nicor ~ nihhus) fades out of the picture. Nixes and nickers are one thing, and Old Nick is something quite different.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: 10 Euro Gedenkmünze 2011 – 500 Jahre Till Eulenspiegel, PP, Bildseite. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Multifarious devils, part 3. “Pumpernickel,” “Nickel,” and “Old Nick” appeared first on OUPblog.

Happy birthday Charles Kingsley

The first time I tried to read The Water-Babies I was 7 or 8 years old. I was sitting on a beach near Margate, during a summer when my other reading had mostly been American comics: Spiderman, Superm an, and the rest. Then I opened up a strange story about a hidden underwater world, in which a young chimney sweep is transformed into a newt-like baby who swims around the world righting wrongs, and eventually discovers that the most important battles are inside him. He was like a tiny Victorian superhero.

an, and the rest. Then I opened up a strange story about a hidden underwater world, in which a young chimney sweep is transformed into a newt-like baby who swims around the world righting wrongs, and eventually discovers that the most important battles are inside him. He was like a tiny Victorian superhero.

The back of my comics usually carried an advertisement for ‘Sea Monkeys’: little marine creatures that (according to the somewhat fanciful illustration) were as exotic as mermaids and as orderly as the inhabitants of an ant farm. And The Water-Babies was no less confused and confusing; it was a scientific treatise, a fable about self-improvement, and a modern fairy tale, all crammed into less than 200 pages. I was hooked.

This year The Water-Babies is 150 years old, an event marked by a special anniversary edition published by Oxford University Press that will allow a whole new generation to dip into Tom’s strange underwater adventures. Celebrating the man who wrote it is slightly harder. Few writers are as puzzling and eccentric as Charles Kingsley, and trying to pin him down is like putting your thumb on a blob of mercury.

In some ways he was a pillar of the establishment, serving at various times as Cambridge’s Regius Professor of History, chaplain to the royal family, Canon of Westminster Abbey, and private tutor to the Prince of Wales. But he was also a bundle of contradictions. He was a shy extrovert. A no-nonsense sentimentalist. A mesmeric preacher who stammered. An apostle of healthy living who left pipes hidden in the bushes around his home in case the urge to smoke suddenly came on him when he was out walking. In public he fought for the rights of ordinary workers; in private he referred to the Irish as ‘white chimpanzees’. He was an enthusiastic hunter who once befriended a wasp he had saved from drowning.

In some ways he was a pillar of the establishment, serving at various times as Cambridge’s Regius Professor of History, chaplain to the royal family, Canon of Westminster Abbey, and private tutor to the Prince of Wales. But he was also a bundle of contradictions. He was a shy extrovert. A no-nonsense sentimentalist. A mesmeric preacher who stammered. An apostle of healthy living who left pipes hidden in the bushes around his home in case the urge to smoke suddenly came on him when he was out walking. In public he fought for the rights of ordinary workers; in private he referred to the Irish as ‘white chimpanzees’. He was an enthusiastic hunter who once befriended a wasp he had saved from drowning.

At the same time, he had some fairly constant obsessions, which rippled away underneath everything else he said and did. He was especially anxious about dirty water, and fought a long campaign for better sanitation. So did many of his contemporaries, of course, but for Kingsley clean water wasn’t just a matter of health or hygiene. Being clean on the outside was the first step to being clean on the inside. Or, as he put it in one of his sermons, ‘If you will only wash your bodies your souls will be all right’.

In 1855 he published Glaucus, a guide to rockpools, named after the fisherman in Ovid’s Metamorphoses who grows a tail and fins and ends up living under the waves. For Kingsley he was something of a role model, because one of his own fantasies, when he stood on the beach, was ‘to walk on and in under the waves … and see it all but for a moment’. In one way his fantasy was bang up to date. That same year – 1855 – a French inventor was showing a diving suit in Paris that included a helmet fitted with portholes and heavy boots that allowed the owner to clump along the seabed at depths of up to 40 metres. But in another way, for Kingsley’s fantasy to come true he didn’t need science. He needed fiction. He needed to construct an underwater world out of paper and ink.

Eight years later, with the publication of The Water-Babies, that’s exactly what he did. When little Tom slips into the river and becomes a water-baby, he also slips into a parallel world of storytelling, where he can leave his dirty body behind, like a snake wriggling out of its skin. It is like a baptism that changes him inside and out. Kingsley had created a hero whose life from now on was to be one long, happy, cold bath.

Given how strange the story is, one might expect that its readership these days would be limited to historians and psychologists. Yet for such a small book it continues to have a surprisingly large cultural presence. There are films, adaptations and abridgements galore, not to mention dozens of modern parallels in novels such as Jacqueline Wilson’s Connie and the Water-Babies. In 1998 there was even a TV advert for Evian that showed some babies performing a complicated dance routine underwater. But why would anyone still want to read the original story?

Click here to view the embedded video.

When I was writing the introduction to OUP’s new edition, this is the question that kept nagging away at me, and the best answer I can offer is closely bound up with my own childhood memories. Kingsley’s great skill as a writer is that he brings together absolute realism and absolute fantasy — two seemingly incompatible strains of thought that children love equally — and switches between them as quickly as someone spinning a coin. He describes the world as it is, and the world as it might look if the imagination was in charge, where if there is ‘sea-rock’ then why shouldn’t there be ‘sea-toffee’?

Above all, he asks us to be surprised by parts of the world we usually take for granted: spider’s webs, fish scales, soot, even children. ‘Look, again, at those sea-slugs’, he writes in one of his early papers on the seashore, and that’s exactly what his own writing does. He looks again at everything, no matter how tiny or ugly or ungainly it is. He finds a kind of awe in the ordinary.

Robert Douglas-Fairhurst is the author of Becoming Dickens (Harvard UP, 2011), winner of the 2011 Duff Cooper Prize, and he has edited editions of Dickens’s Great Expectations, and A Christmas Carol and Other Christmas Books and Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor for Oxford World’s Classics. He has written the introduction and notes for the recently published The Water-Babies. He also writes regularly for publications including the Daily Telegraph, Guardian, TLS, and New Statesman.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Images in the public domain, taken from The Water-Babies

The post Happy birthday Charles Kingsley appeared first on OUPblog.

What is a poem?

In 1934 William Carlos Williams famously published what seems to be a note left on the refrigerator for a spouse to read, only now set typographically to look like a poem. It’s called “This is Just to Say”.

I have eaten

The plums

That were in

The icebox

And which

You were probably

Saving

For breakfast

Forgive me

They were delicious

So sweet

And so cold

Like the ‘found object’ that an artist exhibits in the museum to raise the question “what is art?”, Williams’ ‘found’ poem seems to ask the reader, “is this a poem – and, if so, why?” We are invited to notice what we do when we read something as a poem. Perhaps we scrutinize it for an implied theme (“it’s really about temptation and forgiveness”, for instance); a poem is never “just to say” what it says. The space that Williams has left so abundantly around the words begs to be filled. “Forgive me” acquires a powerful resonance, all alone on the line, especially in connection with the temptation of fruit! Look what happens to the common, unremarkable words “sweet” and “cold” when you put some space around them. Williams invites us to wake up to the poetry of everyday speech.

Is “This is Just to Say” a characteristically modernist poem? Here’s another poem, written a good two thousand years before Williams’ poem, which also claims to be “just to say”. Williams was just saying sorry, and Poem 49 by Roman poet Catullus is just saying thank you.

Sweetest-spoken of Romulus’ descendants,

All that are, or have been, Marcus Tullius,

and all who will yet be in other times–

The greatest of thanks to you from Catullus,

Who’s the worst poet of all the poets,

By as much the worst of all the poets

As you’re the best of all the lawyers.

Or, in the original Latin:

Disertissime Romuli nepotum,

quot sunt quoque fuere, Marce Tulli,

quotque post aliis erunt in annis,

gratias tibi maximas Catullus

agit pessimus omnium poeta,

tanto pessimus omnium poeta,

quanto tu optimus omnium patronus.

All educated Romans had learned the art of rhetoric and eloquence was prized in all kinds of communication. Elaborate compliments and insults were honed, admired, remembered, and passed around. We sometimes speak of compliments, even insults, as being well-turned, as though they had been shaped on a lathe. So, there’s craft involved.

But is it art? Catullus published a number of well-turned insults as poems, and some compliments too, including this one. Why does he publish (and versify) this little thank you note? If we’re looking for an implicit theme, Catullus offers us little that would enable us to say “It’s really about….”. And what Catullus’ poem highlights is not so much significant words as grammatical and rhetorical forms: the superlatives, the amplified repetitions of a statement. Cicero was a great orator, and amplification was the name of the game in Roman oratory, so this might be a compliment to Cicero’s own verbal skill.

But can we be sure that it really is a compliment? In Catullus’ Latin, awkward jingles, bare symmetries, and a restricted and repetitive vocabulary all lend a dutiful sound to the string of superlatives (“most eloquent”, “best”, “worst”, “greatest”). It is as though Catullus wanted to give the impression that he was taking dictation. Even Cicero’s name, Marcus Tullius (Marce Tulli in the vocative case) is made to form a jingle with Catullus’ own name, two lines down in the same position at the end of the line. Such is the baldness and exaggeration of the comparison in the last three lines that an awkward silence seems to descend as the poem ends. Even Cicero, who was not a modest man, must have suspected that there was more to this than meets the eye.

But can we be sure that it really is a compliment? In Catullus’ Latin, awkward jingles, bare symmetries, and a restricted and repetitive vocabulary all lend a dutiful sound to the string of superlatives (“most eloquent”, “best”, “worst”, “greatest”). It is as though Catullus wanted to give the impression that he was taking dictation. Even Cicero’s name, Marcus Tullius (Marce Tulli in the vocative case) is made to form a jingle with Catullus’ own name, two lines down in the same position at the end of the line. Such is the baldness and exaggeration of the comparison in the last three lines that an awkward silence seems to descend as the poem ends. Even Cicero, who was not a modest man, must have suspected that there was more to this than meets the eye.

Was Catullus parodying the orotund symmetries of his prose? There is a nice effect in the second and third lines, where each element of the tripartite division between past, present and future is longer than the last. Cicero’s speeches are full of this device, which is called a tricolon crescendo. But Cicero might also have suspected that Catullus was mocking his high opinion of himself. The great orator was notoriously self-important, and he was well aware of this reputation. Was Catullus trying to immortalise him as the sort of person who might swallow flattery this bald? Or were all these speculations paranoid imaginings, and Cicero should accept the compliment graciously? We readers are in much the same situation as Cicero, not sure whether we are in on the joke or not. Like Cicero, we do not want to be dupes, and so we return to the poem again and again, trying to catch a tone of voice. But the poem maintains its deadpan.

What do we learn about poetry from these two poems on the edge? Perhaps a poem is what you read again because it seems to means something other than it says (and vice versa). Williams’ poem, we feel, means more than it seems to say, but Catullus makes us hover over the possibility that his words don’t mean what they say at all. Williams and Catullus may be suggesting that there is a continuity between the care we take with the language of some of our everyday communications and the care with language that makes poetry what it is. But they are also asking us to notice what it is that kicks in when we write and read an utterance as poetry.

William Fitzgerald is Professor of Latin at King’s College London and has taught at the University of California and Cambridge University. He is the author of several books on ancient literature, most recently How to Read a Latin Poem If You Can’t Read Latin Yet (OUP, 2013).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Catullus [public domain] via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What is a poem? appeared first on OUPblog.

June 11, 2013

New Generation Thinkers 2013

The research that went into my monograph was, like most academic scholarship, very specific: it focused on the ways in which Victorian poets drew on, contributed to, and resisted the development of the scientific discipline of psychology in the mid-nineteenth century. However, as is invariably the case with even the most recondite research, it also addressed larger issues. In this case, different ways literature and psychological science represent the mind, and the relationship between artistic and scientific approaches to human experience more generally. These issues are however necessarily subordinated to the detailed textual and critical analysis that forms the basis of academic literary study.

After The Poet’s Mind was published, and as I continued to research the intersections between literature and science in the nineteenth century, I kept thinking about how to combine detailed academic research with a consideration of the broader questions raised by that research. Hopeful that those questions would be of interest to a wide audience, I applied to the BBC and Arts and Humanities Research Council New Generation Thinkers initiative, which offers humanities researchers in the early stages of their careers the opportunity to discuss their research on Radio 3’s Night Waves programme and at the BBC’s annual Free Thinking Festival. In May I was announced as one of the New Generation Thinkers for 2013.

I’m delighted to have the opportunity to share my research with non-academic audiences, but now that the initial thrill of excitement has subsided and I’m starting to think about my first broadcast, I find myself asking questions about the relationship between academic scholarship and public engagement. How can I share the ideas behind my research, clearly and engagingly, with a broad audience, without losing sight of the difficult intellectual problems which drew me to my subject in the first place? How can I reconcile the complex details and the big ideas which I see as equally vital to academic research?

Image credit: the 2013 BBC/AHRC New Generation Thinkers, with Gregory Tate second from left, back row; provided by the BBC.

Shahidha Bari, one of the New Generation Thinkers for 2011, has examined the same issues. ‘Difficulty is what academics deal in,’ Bari writes, and she argues powerfully against the notion that this difficulty needs to be reduced to something more accessible in order for it to be palatable to a non-academic audience. The division between ‘difficulty’ and ‘accessibility’, Bari suggests, is a false one; the difficulty must be retained if the research is to make any substantive contribution to public debates. I support Bari’s comments resolutely, but there remains the practical issue that academic forms for disseminating research (monographs, journal articles, conference papers) and forms of public engagement (radio programmes, blogs) address different audiences, using different styles of language and speaking from and to different frames of reference.Bari’s piece highlights the difficulties of translating between these forms, but, nonetheless, a type of translation is perhaps what is required.Bari’s key point, though, remains unassailable: the process of translating academic research into public engagement cannot dispense with intellectual complexity, which is the essence of the research itself.

Forums in which academics can share their ideas with the public are proliferating at the moment: the launch in May of The Conversation, a news website written by academic researchers, is just one of the latest examples. The heightened focus on public engagement is a challenge for scholars committed to preserving the academic standards and intellectual integrity of their research, but it’s also an opportunity for us to demonstrate how our complex and original work can confront preconceptions, communicate new knowledge and new perspectives, and inform public debates. It’s an opportunity which humanities researchers, who perhaps have been less effective than scientists in publicly advocating the significance of their work, need to embrace while retaining their open-minded scepticism and determination to interrogate assumptions. Academics are skilled in communicating and discussing their ideas in the classroom, and we now need to continue the discussion outside universities as well.

My research on the complex links between literature, science, and psychology in the nineteenth century draws on an impressive body of work by a range of scholars. I strive to meet the high standards of rigour and attention to detail which characterise this work and academic research on literature more generally. I also hope, though, that my close analysis of nineteenth-century literature, and my consideration of its links to science, will be of interest to a non-academic audience, both in itself and because I’m convinced that an awareness of nineteenth-century views of the relation between literature and science can inform current debates about the place of the humanities and the sciences in education and culture. The question of how to combine these two aspects of research, the scholarly and the public, is a difficult one, but it’s also pressing and needs to be addressed. Luckily, academics are not shy about tackling difficult questions.

Gregory Tate is Lecturer in English Literature at the University of Surrey. His book, The Poet’s Mind: The Psychology of Victorian Poetry 1830-1870, is published by Oxford University Press. You can follow him on Twitter @drgregorytate.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post New Generation Thinkers 2013 appeared first on OUPblog.

Keep Calm and . . . What?

Keep Calm and Carry On was a propaganda poster produced by the British government in 1939 during the beginning of the Second World War, intended to raise the morale of the British public in the aftermath of widely predicted mass air attacks on major cities. This artistic work created by the United Kingdom Government is in the public domain.

So all the test results are back, and you’re seeing the patient (and perhaps his/her partner) to report that the patient is in the early stages of multiple sclerosis (MS) or is recovering from a clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) indicative of MS. “What’s the next step?” they may ask. Maybe you’ll tell them to go home and continue training for that cross-country bike trip or planning the wedding or designing a website for their new start-up company.In 1939, after the outbreak of World War II and in anticipation of air attacks targeting civilians, the British Ministry of Information designed a number of morale-boosting posters to be displayed across the country. The best known of these is “Keep Calm and Carry On,” which has become a new by-word in kitschy folk art as people are buying plaques and posters with this motto and humorous variations (i.e., “Keep Calm and Eat Chocolate,” “Keep Calm and Call Batman”). Keep Calm and Carry On may possibly be the best advice you can offer to someone newly diagnosed with MS.

Not all MS patients will develop severe disability nor will they develop what is known as “progressive MS”. Therefore, we do not believe inducing a sense of doom is a good idea and we do believe that caution should be exercised in recommending treatment for all patients with MS or CIS at the time of diagnosis. This is especially likely true for those patients who recover very well from their initial presenting symptom in a short time without further recurrences within the next three to five years. In the absence of symptoms or successive MRIs with increased areas of plaque, it is reasonable to withhold treatment while scheduling regular follow-up visits for the patient. Patients with MS often do well without any treatment. In addition to the likelihood that the MS may prove benign — though this requires years of follow-up to establish — disease-modifying drugs are only partially effective in the short term, and there is as yet minimal data to suggest that they prevent disability in the long term.

Currently available drugs target the early inflammatory phase of the disease, that is, the phase characterized by relapses and remissions. Most patients begin with a relapsing-remitting course; therefore, it is reasonable to focus on this aspect of the disease process. Unfortunately, none of the established or newer drugs are likely to be curative even if begun at the earliest stage of disease. There is presently very little evidence that partially stopping relapses or modifying the inflammatory response prevent patients from entering the progressive phase of the disease. Further, the lesson from the stronger medications that actually work quite well in eliminating most if not all of the inflammatory activity, such as natalizumab, should make any clinician reluctant to subject a patient to potentially lethal side effects without reasonable evidence of relatively increased inflammatory activity. Nevertheless medicines help the right patient at the right time. MS is a great example of the practice of individualized medicine.

Speaking of individualized medicine, there is a lot that can be done beyond the immunomodulatory treatments for an MS patient with clinically active disease and life-disrupting symptoms. Until a cure for all forms of MS is found, practicing physicians must help patients find symptom-management strategies to improve the quality of daily life. Successful management requires a multidisciplinary integrated approach by all health care providers involved in the patient’s care.

The pathophysiology of MS consists of bouts of inflammatory activity as well as a neurodegenerative process afflicting the central nervous system. Symptoms of MS parallel these processes. Most MS treatment approaches focus on preventing or shortening relapses by modulation (e.g. interferons), suppression (e.g. steroids), or partial elimination (e.g. plasma exchange) of immunological insult. If the acute symptom relates directly to the relapse, then these approaches can be effective. However, many MS symptoms correlate to the neurodegenerative component of the disease or are secondary to disease-associated lifestyle changes, neither of which responds to immuno-mediated strategies. Indeed, some immunomodulation strategies may worsen MS symptoms even while preventing further relapses.

Because many MS symptoms are closely inter-related, it is difficult to treat one symptom without affecting another. Patients may acquire a long list of medications, each addressing a specific symptom, from multiple providers. We recommend assembling a “multidisciplinary team” of consultants with specific interest in MS from neurology, rehabilitation, urology, psychology, psychiatry, speech therapy, sleep medicine, dietetics, patient education, and social services. Neurologists generally lead the care of patients with MS, especially regarding initial diagnosis, changes in diagnosis, choosing disease-modifying medications and prognosis discussions, but rehabilitation specialists often provide more effective symptom management.

We also recommend scheduled reassessments of patient needs as the disease evolves. While preventing relapses may be the primary goal in the early stage, reassurance may be more important in relapse-free periods. These periods allow the patient to focus on life-style adjustments for sleep and weight control. Later, the primary focus can shift to chronic progressive, neurodegenerative worsening. Because many recommendations for symptomatic relief can be stage-specific, we must inform patients from the first interaction that their needs may change. For chronic symptoms, it makes sense to focus on one or two problems at a time to prevent patient burn-out associated with consultations with multiple providers on every visit to the medical center. Early recognition and treatment with one or two drugs dealing with the core complications of MS (immobility, fatigue, sleep problems, weight control, and heat sensitivity) will minimize their impact on future symptoms.

While our goal as clinicians is to keep MS patients comfortable and well able to function, our work at the bench must still aim for prevention and cure. However, after the past decades in which all but a few investigators bought into the hypothesis that MS is only an autoimmune disease and designed experimental treatments accordingly, the lesson is, again, keep calm and don’t look for a one-size-fits-all solution. We need to treat patients by addressing their specific basic pathophysiology. Treating patients based on the immunopathology that characterizes their own lesions will ultimately result in a focused “individualized medicine” approach. For the patient who draws the short straw for MS, there is no short-term and easy answer today. Keep calm, carry on, and adapt to change for the long haul.

Moses Rodriguez, Orhun Kantarci, and Istvan Pirko are the authors of Multiple Sclerosis. Moses Rodriguez, MD, is a Professor of Immunology and Neurology at Mayo Clinic Rochester. He is a past recipient of the American Academy of Neurology’s Frontiers in Neuroscience Award. He is known for his extensive work in immunology and viral models of MS. Monoclonal antibody rHIgM22, helping repair the nervous sytem, discovered and developed in his laboratory, is now in phase I clinical trials sponsored by Orhun Kantarci, MD, born in Turkey, educated in Istanbul University and the Mayo Clinic, is an Assistant Professor of Neurology at Mayo Clinic Rochester and prolific clinician. He is known for his epidemiology and genetics work, currently compiling a virtual bio-repository of MS samples. He spear-headed the clinical trial with rHIgM22. Istvan Pirko, MD, born in Hungary and educated at the University of Budapest, the University of Cincinnati, and the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, now serves as an Associate Professor of Neurology at Mayo Clinic Rochester and is an expert in diagnostic imaging of demyelinating diseases. He has been at the forefront of imaging demyelinating diseases in mouse models besides humans. The three have collaborated on Multiple Sclerosis (Oxford University Press, May 2013).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Keep Calm and . . . What? appeared first on OUPblog.

The power of popular songs

1883. In Tourcoing, a French industrial town right on the border with Belgium, the local celebrity and writer of Flemish origin Jules Watteeuw published Le marchand d’oches for the first time. His song about a Flemish rag-and-bone man who had migrated to Northern France to make a living but kept dreaming about his hometown as the Garden of Eden, was a huge success. It was reprinted numerous times in the following decades; the song would influence the Northern French understanding of Flemish migrants for almost a century to come. Even in 1995, when inhabitants of the city Roubaix were asked for their earliest recollections of Flemish migrants in their town, some started to sing this very song.

Premier couplet

Quand ze l’a venu en France,

Ia, ze l’avais de çagrin;

Ze l’avais pas eu de çance

Dans mon butique à Menin.

Z’avais in bruette

Et mon femm’ rien de tout,

V’la qu’ z’ai in carette,

Un’ baudet et de sous:

Refrain

Ze suis de petite marçent

Ze agne beaucoup de l’arzent

Z’acett’ tout sort’ de çosses

Vela de merçant d’osses… hi!

4e couplet

Ze suis connu dans le ville,

Par lé petit et lé grand,

Tout de femme et tout de fille

Connaît bien de roux flamand.

Après me l’ouvrasse,

Moi ze rentre à me maison,

Ze manç’ de potasse

Et ze zoue de cordéon.

5e couplet

Quand ze l’aura fait feurtune,

Moi z’irai à ma pays

En Belzique à Lechterwune

Ze serai en Paradis.

Z’acét’rai de terre,

Et ze mettrai dans de çamps

Tout de pomm’ de terre

Pour moi et mes p’tits l’enfants.

The Centre for the History of Intercultural Relations (CHIR) in Kortrijk/Courtrai, Belgium, studies the integration of Flemish newcomers in Northern France in the second half of the nineteenth century. An important part of the research project centres on the identificational dimensions of this integration process: how did the Belgian Flemish migrants and Northern French inhabitants, both living in the same border region, relate to each other? This so-called history ‘from below’ requires adequate sources to grasp the actual experience of identification and confrontation between individuals and groups. A popular song such as Le marchand d’oches seems to offer some interesting insights – but only when interpreted with careful attention. Popular sources are indeed often regarded by historians as mere representations of the life and ideas of the writer and his environment. This approach denies the sources a part of their actual importance in history: similar as to literary texts, these apparently innocent popular songs had the power to influence the cultural conceptions of an entire society.

Peasants conversing, David Teniers, the younger (1610 – 1690)

Living in the industrial Tourcoing around the turn of the century, Watteeuw’s destitute Flemish peasant was an easy recognisable personage. As a poet and a writer, Watteeuw had only collected and magnified what he thought were the typical characteristics of a Flemish migrant. He thus created a stereotype which everybody knew, but nobody identified with – certainly not himself, a second generation Belgian migrant. Watteew’s personage was a peculiar character: a red-haired rag-and-bones man (stereotypic physiognomy), who spoke a hybrid Franco-Flemish language (stereotypic language), ate typically Flemish dishes such as potatoes and buttermilk (stereotypic alimentary habits), and played the accordion (stereotypic cultural expression). Of course, this Flemish migrant cherished the stereotypic dream of returning to his village in Belgium once he had made his fortune in France. Not surprisingly, the marchand d’oches planned to cultivate potatoes there. The potato as a culinary predilection of the Flemish functioned as a metaphor for the real cultural belonging of this character. It highlighted the gap between the French urban audience, that didn’t dream of growing crops on the fields, and the newcomers, that didn’t manage the give up their roots.

Of course, the personage of the Flemish migrant had already made his appearance in popular culture before the publication of the marchand d’oches. But while many authors imitated Flemish migrants in their songs by using funny language to mock and stigmatize them, it was Jules Watteeuw’s sketch of a Flemish migrant that set the standards fort the popular personage. From then on, every Flemish character and even every migrant that appeared in popular culture, turned out to be someone who dressed like a peasant, spoke an unbearable language, and abundantly referred to his alimentary habits. By the end of the nineteenth century, this stereotypical personage was adopted as a regular character in song repertoire, and emerged in local newspapers and puppet theatre in the French northern department. This omnipresence of the Flemish personage in popular culture produced a comic effect on all listeners – Flemish as well as French. The stereotypical characteristics were exaggerated to the point that not even Flemish migrants identified with them. More importantly, the fact that Flemish migrants were staged in all parts of popular culture indicates that their presence was gradually accepted. We dare say even more: the integration of Belgian-Flemish people in Northern France partially occurred by means of such discursive practices. In other words, their integration process was also a matter of discourse , in which the use of stereotypes metaphorized in some way the physical integration of Flemish migrants.

In 1883, Jules Watteeuw created a naïve, rather brute but courageous rag-and-bone man that would influence an entire sociological process of integration. For decennia to come, the Flemish migrant in Northern France would be regarded as an uncultivated peasant who did not speak any French – although he thought he did. The stereotype affected the relations between Northern French and Flemish Belgians until well into the twentieth century. Still, despite the Flemish being an object of derision, their absence from the daily scene was unthinkable – just as it was in popular culture.

Saartje Vanden Borre & Elien Declercq are employed by Centre for the History of Intercultural Relations (KU Leuven Kulak, Kortrijk, Belgium). Their article “Cultural integration of Belgian migrants in northern France (1870–1914): a Study of Popular songs” in French History is available to read for free for a limited time. Dr. Saartje Vanden Borre is a member of the research group Cultural History since 1750 of the University of Leuven and of the Centre for the History of Intercultural Relations (CHIR) at KU Leuven Kulak. Her research interests include migration history, educational history, and memory studies. She previously published on the history of Belgian migration to France in journals such as Socialist History, French History, and Tijdschrift voor Sociale en Economische Geschiedenis. She is a member of the editorial board of De Leiegouw. Dr. Elien Declercq, research fellow of the Centre for the History of Intercultural Relations, has published on literary discourse analysis, migration literature and intercultural transfer in border regions in journals such as Revue de Littérature Comparée and International Journal of Multilingualism. In 2012, Academia Press in Ghent published Vreemden op vertrouwd terrein (Foreigners on Familiar Ground) by Saartje Vanden Borre and Migrants belges en France by Elien Declercq.

French History offers an important international forum for everyone interested in the latest research in the subject. It provides a broad perspective on contemporary debates from an international range of scholars, and covers the entire chronological range of French history from the early Middle Ages to the twentieth century.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Peasants conversing by David Teniers, the younger. Public domain via wikimedia commons.

The post The power of popular songs appeared first on OUPblog.

June 10, 2013

The reign of Alexander the Great

Alexander the Great, Leader of the Macedonians, was born in 356 BC. After his death from fever on 10 June 323 BC, his dominion fell apart, the most lasting tribute to his achievement being the town of Alexandria, Egypt. We present the following extract from John Atkinson’s introduction to the new Oxford World’s Classics edition of Alexander the Great by Arrian, which highlights the importance of Alexander’s reign in world history.

The relatively short reign of Alexander (336 to 323 BC) marked one of the major turning-points in world history. The Greek city states continued to function after his death, but the world order had changed and a new era began, which came to be labelled the Hellenistic period. For Alexander, like many an autocrat, departed without leaving a viable succession plan. The senior officers who had survived the normal hazards of war and Alexander’s paranoid suspicions were not united in purpose. Known as the Successors (Diadochoi), they acknowledged as king for a while Alexander’s intellectually challenged half-brother Philip Arrhidaeus and then too Alexander’s son by his Bactrian (Afghan) wife, born after his death. In 305 the leading Successors each took the title of king and demarcated his kingdom. Thus Alexander’s empire was divided into the Hellenistic kingdoms, each with its ruling dynasty, the one that lasted the longest being Egypt under the Ptolemies, which survived till the suicide of Cleopatra in 30 BC.

Head of Alexander the Great, by Leochares, ca. 330 BC

Such is the ambiguity of dependency that while Alexander’s campaigns furthered the spread of Greek culture, the Hellenistic kingdoms revealed the two-way effects of accommodation and assimilation. This pattern is well illustrated in Egypt by the Rosetta Stone and depictions of the Ptolemy of the day as a Pharaoh. And then there was the power of Roman imperialism, for by 30 BC what remained of the Hellenistic kingdoms was all under Roman control. These developments had some impact on the shaping of the Alexander legend. For example, in Egypt in the third century BC a revisionist account claimed Alexander as one of its own, as the bastard son of the Pharaoh Nectanebo. This developed into what is styled the Alexander Romance, later falsely attributed to Callisthenes (and thus conventionally referred to, as in this volume, as the Pseudo-Callisthenes), an account which over time generated derivatives in a broad sweep of cultures from Iceland to Indonesia. But in patriarchal, imperialistic Rome Alexander became the hero to be emulated or imitated, from Pompey the Great to Alexander Severus (emperor AD 222–35), and we have the image of the lanky Caligula once parading in the breastplate of the rather short Alexander. That last case readily explains why emulation of Alexander by unpopular autocrats was countered by hostile reworking of the legend.The pattern has continued into modern times, each generation producing new variants to satisfy whatever passion or agenda it might nurse. Thus we have had Alexander welcoming into partnership the Aryan Persians as the Macedonians’ kindred Herrenvolk, or promoting the unity of mankind and campaigning with rather Victorian values. The Cold War produced a more chilling image of Alexander, more in the mould of a Stalin. But interest in the ‘real’ as well as the imagined Alexander the Great continues strong. The last few decades have seen a stream of biographies and historical novels based on the life of Alexander. In the visual media there have been documentaries, feature films, and even a recent stage play.All this activity depends on a fairly limited amount of ancient source material. Textual archival material is virtually limited to a scatter of Greek inscriptions and Babylonian records. Contemporary memoirs are known only from fragmentary quotations and more substantial summaries or reworkings written some three centuries or more after Alexander’s death. To this group belongs Arrian, though it may seem strange to label a text of the second century AD a primary source for a chapter of history of the period 336 to 323 BC. However, Arrian’s concern to revive and justify the accounts of the most authoritative and true primary sources 3 gives his work special value. Comparison with accounts written in the century or so before Arrian’s Anabasis shows that Arrian broke with the fashion of fictionalizing history and was not loading his material with a secondary level of meaning. The title Anabasis Alexandrou (Alexander’s Expedition) indicates that this was primarily a military history, covering Alexander’s advance ‘upcountry’ or into the interior of Asia. The Indica, based largely on Nearchus’ account of his mission to take Alexander’s fleet from the Indus to the Tigris and Euphrates in late 325, is even closer to an archival record. Thus Arrian’s Anabasis, with its companion-piece the Indica, represents something of a time capsule, and is generally regarded as the most authoritative ancient source on Alexander’s campaigns.

One of the most distinguished writers of his day, Arrian represented himself as a second Xenophon and adopted a style which fused elements of Xenophon into a composite, artificial (yet outstandingly lucid) diction based on the great masters, Herodotus and Thucydides. The Oxford World’s Classics edition of Alexander the Great by Arrian is translated by Martin Hammond, with an introduction and notes by John Atkinson. It includes both the Anabasis and the Indica.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, and the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Head of Alexander the Great, by Leochares, ca. 330 BC. Photo shared by Creative Commons license CC-BY-SA-2.5, via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The reign of Alexander the Great appeared first on OUPblog.

Do American children use calorie information at fast food or chain restaurants?

Federal law in the United States requires restaurants with at least 20 locations nationally to list calorie information next to menu items on menus or menu boards. This law includes the prominent placement of a statement concerning suggested daily caloric intake on the menu. While national menu labeling has not been implemented, some fast food and chain restaurants have begun to post this information voluntarily. Thus, we wanted to know if kids actually use calorie information when it is available and we wanted to know what sociodemographic and behavioral characteristics were associated with using this information.

How was the study conducted?

American youth 9-18 years old were asked in an online survey whether they used calorie information when ordering at fast food or chain restaurants and how frequently they visited a fast food or chain restaurant each week. Youth were also asked to report their height and weight from which we calculated weight status (e.g. healthy weight and obesity). The youth’s parents were questioned in a similar survey to see if their race/ethnicity, household income, marital status, and geographical region of residence were associated with youth’s use of calorie information. The study included 721 kids and excluded those who said that they never eat at fast food or chain restaurants (about 8%) and those who said they never noticed calorie information (about 20%).

What were the findings of this study?

We found that of kids who visited fast food or chain restaurants, over 40% reported using calorie information at least sometimes, when it was available. We also found that girls were more likely than boys and youth who were obese were more likely than those of a healthy weight to use calorie information. We also found that youth who eat at a fast food or chain restaurant twice a week or more were about half as likely to report using calorie compared to kids who go once a week or less. This adds to other information about kid’s eating habits.

Why are these findings important for healthy weight in youth?

Our findings are important given the prevalence of obesity among youth and the adverse health effects associated with obesity. We are encouraged that a large number of youth, particularly those who are obese, are using the calorie information to inform their ordering selections. This finding implies that calorie labeling on menus and menu boards may potentially to lead to improved food choices as a way for obese youth to manage weight. More research is needed to assess whether youth know how many calories they should consume in a day given their activity level. Further research is also needed to understand the differences in motivation to use calorie labeling between boys and girls. Public health practitioners, school nutrition services, retailers, and other interested groups can implement education programs in various venues to assist development of this understanding as a way to improve health literacy.

Holly Wethington, PhD, is a Behavioral Scientist in the Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Her work focuses on evaluating public health interventions and researching health behaviors related to obesity. She is the author of the article, “Use of calorie information at fast food and chain restaurants among US youth aged 9–18 years, 2010″ which is available to read for free for a limited time.

The Journal of Public Health invites submission of papers on any aspect of public health research and practice. We welcome papers on the theory and practice of the whole spectrum of public health across the domains of health improvement, health protection and service improvement, with a particular focus on the translation of science into action. Papers on the role of public health ethics and law are welcome.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image courtesy of the Center for Disease Control via thinkstock.com.

The post Do American children use calorie information at fast food or chain restaurants? appeared first on OUPblog.

Does part-time employment help or hinder single mothers?

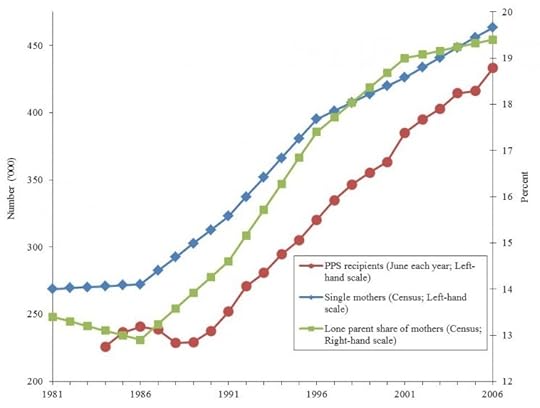

A significant demographic trend in recent decades, in Australia and a number of other developed countries, has been the growth in lone parent families as a proportion of all families. As the graph shows, in 1981, 13 per cent of Australian mothers with dependent children were lone parents; by 2006, this had risen to 20 per cent. Associated with this increase has been growth in welfare dependency of mothers of dependent children, women who may otherwise have depended on a combination of partner income and income from their own part-time employment.

Number of single mothers and Parenting Payment Single (PPS) recipients—Australia

These concomitant trends have led to considerable policy interest in the welfare dependence and employment of single mothers. A particular concern is that an extended period of withdrawal from the labour market creates a ‘disengagement’ effect, with long-term adverse consequences for employment prospects. Such disengagement effects are an issue for all mothers, almost all of whom withdraw from the labour market for at least some period of time due to childbearing. However, policy interest in avoiding or minimising this disengagement effect is considerably heightened for single mothers because of the close correspondence between non-employment and welfare dependence for this demographic group. Aside from direct fiscal implications of such welfare dependency, the concern is that, if sustained long-term, it will have adverse implications for the financial wellbeing of single mothers and their children, as well as other potential adverse outcomes, such as intergenerational transmission of welfare dependence.

Care requirements of children suggest that full-time employment is often not appropriate or desirable for single mothers when the children are young — even given the availability of affordable and high-quality child care. However, part-time employment may be viable, and it is therefore an important empirical question whether part-time employment can mitigate the disengagement effect. That is, by reducing the length of time completely out of employment, part-time employment may improve the longer-term employment prospects of single mothers. Clearly, the policy emphasis placed on accommodating, or even mandating (search for) part-time employment of welfare-dependent single mothers hinges on whether such an effect does indeed exist. Moreover, evidence on the scale and nature of the effect can also inform the particulars of policy settings—for example, how policies depend on the age of the youngest child.

Of course, it is in principle also possible that part-time employment actually hinders movements into full-time employment. Indeed, for some years now, welfare policy in Australia with respect to lone parents—in common with a number of other developed economy countries—has facilitated the combining of welfare receipt with part-time employment via a relatively generous allowance for earnings before benefit entitlements reduce (the earnings ‘disregard’), as well as reasonably low rates of withdrawal of benefits as earnings increase beyond this allowance. This creates significant potential for part-time employment, combined with welfare receipt, to be a substitute for full-time employment on a long-term basis.

Of course, it is in principle also possible that part-time employment actually hinders movements into full-time employment. Indeed, for some years now, welfare policy in Australia with respect to lone parents—in common with a number of other developed economy countries—has facilitated the combining of welfare receipt with part-time employment via a relatively generous allowance for earnings before benefit entitlements reduce (the earnings ‘disregard’), as well as reasonably low rates of withdrawal of benefits as earnings increase beyond this allowance. This creates significant potential for part-time employment, combined with welfare receipt, to be a substitute for full-time employment on a long-term basis.

This social, economic and policy context provides the motivation for our investigation of the causal effect of part-time employment on subsequent labour force status of single mothers. By estimating dynamic models of the determinants of labour force status of single mothers using household longitudinal data, we are able to identify whether part-time work represents a ‘stepping stone’ to full-time employment.

We find strong support for the argument that part-time work is more help than hindrance to transitions to full-time employment. Estimates imply that part-time employment in one year on average increases the probability of full-time employment in the next year by approximately 5 percentage points. Somewhat surprisingly, we find no evidence that the stepping stone function depends on the age of the youngest child or the number of children. This is not to say that these factors are unimportant to labour force status—far from it: estimates show large effects of these factors on labour force status. It is simply that no evidence is found that the stepping stone function of part-time employment depends on these factors. Another way of expressing this is that the increase in likelihood of moving into full-time employment as the youngest child ages, and the decrease in likelihood as the number of dependent children increases, are approximately the same for non-employed single mothers as for part-time employed single mothers.

From a policy perspective, it would seem that the Australian welfare system’s facilitation of part-time employment of lone parent welfare recipients does not promote entrenched welfare reliance. Indeed, our findings imply that policies to promote part-time employment of single mothers will in turn tend to promote full-time employment over the longer-term. Correspondingly, welfare reliance of single mothers over the long-term may be reduced by such a policy stance. Of course, reduced welfare reliance and increased full-time employment could probably also be achieved in the short-term by treating single mothers in the same manner as unemployment benefit recipients – for example, requiring active search for full-time employment – but, at least in the case of mothers with young children, the care needs of the children would suggest this is not in the interests of single mother families or the broader community.

Roger Wilkins is Principal Research Fellow at the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, The University of Melbourne. He is Deputy Director (Research) of the HILDA Survey, Australia’s household panel study. He is a labour economist with a strong interest in the use of panel data to investigate labour market behaviour and outcomes. His research interests also extend to the determinants and dynamics of household wealth, and issues of income inequality, poverty and welfare dependence. He is a co-author of the article ‘Does part-time employment help or hinder single mothers’ movements into full-time employment?’, which appears in the journal Oxford Economic Papers.

Oxford Economic Papers is a general economics journal, publishing refereed papers in economic theory, applied economics, econometrics, economic development, economic history, and the history of economic thought.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: (i) Graph, author’s own. Do not reproduce without permission. (ii) Blocks still life. By matzaball, via iStockphoto.

The post Does part-time employment help or hinder single mothers? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers