Oxford University Press's Blog, page 925

July 12, 2013

Why reference editors are more like Gandalf than Maxwell Perkins

Recently I was chatting with a regular at my gym, an Irish man named Stephen, when he asked me what I do for a living. I told him I am an editor in the reference department at Oxford University Press, and he excitedly launched into a description of the draft manuscript he had just completed, a novel about his wild (and illicit) youth spent between Galway and the Canary Islands. Stephen was looking for an editor to help him smooth out his dialectical writing and horrible grammar so that it didn’t read quite so much like Trainspotting. His concern was humorously underscored when, I thought at first that he had written a novel about his horrible grandma, having misunderstood his thick brogue. After shaking off visions of Livia Soprano, I gently suggested I might not be the editor he was looking for.

Stephen, like many people I’ve spoken to, assumed that my job entails revising manuscripts and helping authors write more clearly and forcefully, while picking off the occasional dangling modifier or the incorrect use of “effect” vs. “affect.” That’s the editing process people are familiar with, the craftsmanship that adds style and coherence to writing once the big ideas are down on paper. Editing to “let the fire show through the smoke,” as the author and editor Arthur Plotnik once said.

The trouble is, that doesn’t remotely describe a reference editor’s job. The truth is that I’m more like a project manager than a Maxwell Perkins (legendary editor to Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald, among others). I plan scholarly reference works (mostly print and online encyclopedias), and then I guide them through to publication. Because these reference works are so complex, written by dozens, if not hundreds of authors, the publisher needs to take a very active role in the publication process, much more so than with single-authored books.

Ok, but a project manager? Snore. How about you just think of me as Gandalf? Like Gandalf, I assemble and lead a fellowship of individuals who each play an important role in a grand (publishing) quest. Like Gandalf, I know each leg of that quest, our final destination, and all the potential dangers along the way. While I’d prefer to go by Gandalf, in publisher’s parlance I’m actually called a commissioning editor, as opposed to an acquisitions editor. Acquisitions editors review query letters, or partial or complete manuscripts, and then make decisions about which ones to publish, or compete with other publishers for the rights if the title is popular enough. But as a commissioning editor, I come up with an idea for an encyclopedia or reference website, and then I go out and find, or “commission,” the experts to make it happen – my merry (occasionally not-so-merry) fellowship.

My job is to partner with a subject specialist, usually the Editor-in-Chief, to think through the scope of the work (how many articles, and on what topics?), author assignments (who will write each article?), and the composition of articles (will there be abstracts? Keywords? Bibliographies and further reading sections?). Because the Oxford editor has a macro responsibility for the project, we do relatively little actual editing of individual articles. The Editor in Chief, usually with the help of an Editorial Board of area experts, spend the most time reviewing and suggesting revisions to individual articles, while dedicated proofreaders and copyeditors focus on the writing mechanics.

Recently I’ve been acting as the Grey Wanderer for the Encyclopedia of Social Work, which is free for you to explore throughout the summer and has the added benefit of illustrating some unique aspects of digital publishing. The Encyclopedia of Social Work is considered the standard reference work in the field, a classic reference work last published in four volumes in 2008 through a partnership between Oxford University Press (OUP) and the National Association of Social Workers Press (NASW). It contains overview articles on most major social work-related topics, from Alzheimer’s disease and caring for the elderly to migrant worker populations and violence in urban practice. Around 2011, OUP and NASW decided it was time to transform the print Encyclopedia into a dynamic online reference resource.

My first task was to write a proposal outlining OUP’s and NASW’s shared vision for the site. I highlighted key factors that I felt would make it successful, such as discoverability (users should be able to find it through a simple Google search), flexible publishing schedules (we should commission online-only articles and be able to quickly publish them once they pass peer review), and comprehensiveness and internationality (users should be able to find articles on any major topic of interest to social workers, including on global issues). I also decided that, since online publication frees us from length constraints (i.e. no physical page count limit), we could allow authors to write lengthier articles that cover their assigned topics in greater depth.

Once the proposal and accompanying budget were approved, I needed to think about editorial oversight. This project was unique in that OUP had a publishing partner, NASW, dedicated to serving social workers, and so I followed their recommendation that we build a standing online editorial board of thirteen subject specialists and one Editor in Chief, Dr. Cynthia Franklin of The University of Texas at Austin School of Social Work. I reached out to the area editors and to Cynthia, discussed the work that they would need to commit to, and contracted them. I next worked with them to build out the headword list, or list of articles included in a reference work. The existing 2008 print edition had a headword list of approximately 400 subject articles and 200 biographies, and I wanted to add at least 100 new articles within the first year of launching the site. I asked each Editorial Board member to come up with twenty ideas for new articles within his or her area of expertise, and I solicited further suggestions from social workers unconnected to the Encyclopedia.

In addition to commissioning new articles, I realized that some existing articles needed to be revised. For instance, the articles often included outdated demographic data, since the Census Bureau has now released census data from 2010. And legislative changes, such as the Affordable Care Act, had implications for social work healthcare. I asked the Editorial Board to come up with a few articles that should be extensively revised as a matter of priority, while at the same time inviting all 437 existing contributors to update their articles in minor ways, such as by incorporating more recent books and websites into their bibliographies and further reading sections.

The content of a work is obviously very important, but a commissioning editor is also responsible to a certain extent for the look of it. If I were working on a new print edition of the Encyclopedia of Social Work, that would mean picking out an appropriate trim size for the binding, deciding whether it would be paperback or hardcover, whether it would have images, and if so, whether they would be color or black and white, and offering feedback to the designer on different cover options. Since the Encyclopedia is an online product, I collaborated with a large team of XML content specialists, graphic designers, marketers, and site developers to ensure that the articles display cleanly, that the homepage is attractive, and that users can easily navigate to the content they are looking for. Seemingly minor questions, such as whether the Browse-by-Subfield box should be collapsed or expanded by default, required thought.

And, presto, we have a new reference site up and running! Ok, obviously I’ve glossed over some steps (the Encyclopedia of Social Work site took about two years to plan and execute!), but in its simplest form that’s what it takes to build a large-scale reference work. Admittedly, the idea of working with a single author, on a single manuscript, is at times appealing. (Am I the only reference editor who has ever had an anxiety dream in which the database I use to track my most complex projects turns into the cockpit of an Airbus, and I don’t know how to fly? I doubt it). But when all the moving parts of a project come together to form something of lasting value to a community of people, you have a sense of pride from having been there from the shires to the mountains of Mordor.

Max Sinsheimer is a Reference Editor at Oxford University Press in New York.

The Encyclopedia of Social Work is the first continuously updated online collaboration between the National Association of Social Workers (NASW Press) and Oxford University Press (OUP). Building off the classic reference work, a valuable tool for social workers for over 85 years, the online resource of the same name offers the reliability of print with the accessibility of a digital platform. Over 400 overview articles, on key topics ranging from international issues to ethical standards, offer students, scholars, and practitioners a trusted foundation for a lifetime of work and research, with new articles and revisions to existing articles added regularly.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only social work articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Photo of Concise OED definition by Alice Northover via Instagram.

The post Why reference editors are more like Gandalf than Maxwell Perkins appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCelebrate National Library Week with OUPLady Chatterley’s Lover and the politics of “variable obscenity”Why are reference works still important?

Related StoriesCelebrate National Library Week with OUPLady Chatterley’s Lover and the politics of “variable obscenity”Why are reference works still important?

Letters from Heaven

While researching in the Archive of Everyday Writings (Archivo de las Escrituras Cotidianas) in Alcalá de Henares, I came across a very curious manuscript. It was the copy of a letter from God which, it claimed, had descended to earth during a Mass held in St. Peter’s in Rome. It had been picked up by a deaf-mute boy called Angel, who miraculously began to read it aloud. The letter exhorted the faithful to observe the Sabbath and live a Godly life, because otherwise God in his vengeance would send war, disease and ferocious dogs to tear apart all those who disobeyed Him. The letter went on to suggest the best remedy against these awful consequences; it urged its readers and listeners to copy it and broadcast the message as widely as possible. It offered a magical incentive: the letter had the power to guarantee a successful childbirth to any pregnant woman who kept a copy.

The letter was a mystery. It was an isolated document, and apart from the date of 1896 there was no context to help me interpret it. No one could even tell me who had donated it to the archive. I knew that ordinary people often wrote prayers to God, and they still do so today. In the Church of Notre Dame de la Daurade in Toulouse, I had seen the book left open for the faithful to inscribe their desperate and grateful prayers to the Black Virgin. But I was not previously aware that corresponding with heaven was a two-way process. My search for other examples of this strange genre bore fruit when after googling various keywords in the catalogue of the Bibliothèque nationale de France I turned up several dozen printed versions of celestial letters.

The Black Virgin of the Daurade, Toulouse

I discovered that many of them had unfortunately gone missing. Perhaps they had been removed from the library by an over-zealous collector, or perhaps these single sheets or small leaflets had simply been swallowed up amongst the library’s millions of documents. What remained of them was kept in the rare book section. I managed to assemble a corpus of 40 celestial letters dating from the nineteenth century, all of them printed except for the Alcalá version which had originally sparked my curiosity.

The letters from heaven followed a common pattern; they told the story of their own miraculous appearance, in which a young and possibly dumb child was empowered to speak and interpret the written word of God. In some versions the letter could not easily be opened. I called this version the ‘Excalibur narrative’, because like the Sword in the Stone, someone special was needed to extract it. In the case of the letters from heaven, that ‘someone special’ was a bishop or a Pope. The letters would allegedly appear at high points in the Christian calendar, like Easter or Assumption Day (15 August), and in sacred locations like St. Peter’s or the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Sometimes the letter was allegedly written in gold, and at other times in the blood of Christ.

The letters from heaven had two faces. On one hand they resembled sermons, urging obedience to the Commandments, Sunday observance, penitence and generous charity to the poor. Like medieval fire-and-brimstone sermons, they threatened plagues, natural disasters and the wrath of God if Christians did not follow the straight and narrow path. All this suggested to me that the letters were authorised or written by the clergy to maintain Christian discipline amongst their flocks. At the same time, letters from God had a more unorthodox character. They were sacred objects which protected the bearer from the evil eye. The magical powers which the letters claimed for themselves betrayed common fears and neuroses, especially about death. For example, the fear of sudden accidental death, which might arrive by drowning or in a fire, could be avoided, and many letters specifically added that the reader who used the letter wisely would not die without confession. I found some letters from heaven which promised the bearer that a vision of the Virgin would appear shortly before his or her death; so the reader would have a little time to prepare for departure. The celestial letter was a form of insurance policy; if you kept it safely in your house, it would not burn down, nor would it be visited by les malins esprits (evil spirits).

The most curious aspect of all was the emphasis on copying the letter and distributing it. Anyone who failed to do this would be damned. According to the letters, the same fate awaited any sceptics who refused to believe that the letter had divine authorship. The letters from heaven had to be copied out and passed on, very much like the chain letters of the late twentieth century of which they were perhaps ancestors. To copy was to be saved and the copyist would be eligible for good luck, a miraculous cure or a win in the lottery.

My search for correspondence from God had started with the intriguing Alcalá letter and brought me via a parish church in Toulouse to the rare book room of the BNF in Paris. The journey had shown me one important thing: it convinced me that even in the nineteenth century ordinary people believed in the magical power of writing. Writing was accorded sacred and magical properties in a world where it was taken for granted that supernatural beings and objects could act directly on people’s daily lives.

Martyn Lyons was born in London and in 1977 moved to Sydney, where he is now Emeritus Professor of History. He research and publish work on the history or reading and writing in modern Europe and Australia. He is the author of “Celestial Letters: Morals and Magic in Nineteenth-Century France” in French History, which is available to read for free for a limited time.

French History offers an important international forum for everyone interested in the latest research in the subject. It provides a broad perspective on contemporary debates from an international range of scholars, and covers the entire chronological range of French history from the early Middle Ages to the twentieth century. French History includes articles covering a wide range of enquiry across the arts and social sciences, as well as across historical periods, and a book reviews section that is an essential reference for any serious student of French history.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: The Black Virgin of the Daurade, Toulouse. Image courtesy of Martyn Lyons. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post Letters from Heaven appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCooperation through unproductive costsLady Chatterley’s Lover and the politics of “variable obscenity”Thinking through comedy from Fey to Feo

Related StoriesCooperation through unproductive costsLady Chatterley’s Lover and the politics of “variable obscenity”Thinking through comedy from Fey to Feo

Book groups and the latest ‘it’ novel

By Robert Eaglestone

I’ve never been to a book group (although I was once invited to a Dad’s ‘Listening to the Album of the Month with Beer’ club) but I’ve always been afraid that it would be a bit of a busman’s holiday for me, or worse, that – because I’m basically a teacher – it would turn me into the sort of terribly bossy know-it-all you don’t want drinking your nicely chilled wine. That said, I often get asked to recommend the current ‘it’ novel for book groups.

But one of the problems with contemporary fiction is just that there is so much written and published all the time that any book, however good, just seems like a drop in the ocean. There is no one ‘it’ book. So, instead, I’m going to sketch a pattern of what’s going on in contemporary fiction to provide a context for reading or choosing a book.

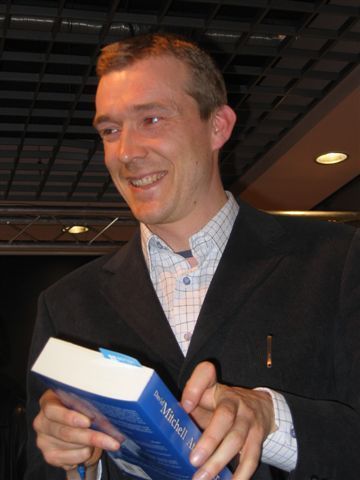

The first thin g that’s going on at the moment in fiction is a sort of literary playfulness. The 60s and 70s were a heyday of ‘experimental fiction’ (B. S. Johnson wrote a novel on cards, so that you could shuffle it and read it in any order you chose) and many novels in the 80s and 90s were ‘postmodern’, playing games with sense, narration and the very idea of fiction itself. Lots of literary fiction today has, on the one hand, inherited and reused these traditions, but on the other, retreated from their (sometimes quite challenging) extremes. Once thought of as terribly inaccessible, these demanding literary techniques have been domesticated and used in the service of plot and narrative. For example, the British novelist David Mitchell’s novel Cloud Atlas is made up of interlocking stories, one within the other. One of its main sources of inspiration is the ‘classic of postmodernism’ If on a winter’s night a traveller by the Italian writer Italo Calvino. But in Calvino’s novel, different stories follow each other and frustratingly, none of the stories are finished; there is no end. In contrast, in Mitchell’s novel the stories, while interrupted in turn, are finished making it both more satisfying, but perhaps less memorable.

g that’s going on at the moment in fiction is a sort of literary playfulness. The 60s and 70s were a heyday of ‘experimental fiction’ (B. S. Johnson wrote a novel on cards, so that you could shuffle it and read it in any order you chose) and many novels in the 80s and 90s were ‘postmodern’, playing games with sense, narration and the very idea of fiction itself. Lots of literary fiction today has, on the one hand, inherited and reused these traditions, but on the other, retreated from their (sometimes quite challenging) extremes. Once thought of as terribly inaccessible, these demanding literary techniques have been domesticated and used in the service of plot and narrative. For example, the British novelist David Mitchell’s novel Cloud Atlas is made up of interlocking stories, one within the other. One of its main sources of inspiration is the ‘classic of postmodernism’ If on a winter’s night a traveller by the Italian writer Italo Calvino. But in Calvino’s novel, different stories follow each other and frustratingly, none of the stories are finished; there is no end. In contrast, in Mitchell’s novel the stories, while interrupted in turn, are finished making it both more satisfying, but perhaps less memorable.

Linked to this is a return not to the weird experimentalism of the 60s but to older traditions of modernism, to writers like Virginia Woolf and James Joyce, where the form of the novel itself is a central part of its meaning. Ali Smith’s brilliant novel, The Accidental (2005), is of this sort. The narrative proceeds through the very different consciousnesses of the characters, shifting and playing games with the chronology. The styles change too: one part is written in questions and answers, another uses different styles of love poetry. But the playing with the text tells you as much about what is going on as the characters.

In contrast to this playfulness in fiction, and equally important, is what can be seen as a turn away from fiction to something more ‘real’. The American novelist and critic David Shields has described this as Reality Hunger and discusses writers and artists who are “breaking larger and larger chunks of ‘reality’ into their works.” This is also happening in other art forms: ‘reality TV’, verbatim theater (in which the script is taken from government enquires, court cases and so on) and in fine art (where Tracey Emin, for example, takes her experiences as the artwork itself). In writing, one symptom of this is ‘popular history’. Kate Summerscale’s The Suspicions of Mr Whicher reads more like thriller than a history book, for example. And of course, after Hilary Mantel, there is a huge boom in good historical fiction, which — like your best history teacher — entertains but also seems to tell you about, say, the Tudors. But part of it also comes from writers like the W. G. Sebald and David Eggers. Sebald’s best work, The Rings of Saturn, describes a walking tour around Suffolk, and it’s unclear whether or not this is fact of fiction. Certainly, it’s full of bits of history, all of which circle around the (rather melancholy) themes of destruction and decay. In contrast to this European melancholy is the exuberance of the American writer David Eggers. His fiction mixes the real (his first book even included his friends’ phone numbers) with the ‘shaped’ and is packed with jokes and reflections. His later work has become more consciously political: What Is the What: The Autobiography of Valentino Achak Deng is by both Eggers (it’s called a novel) and a Sudanese ‘lost boy’ Valentino Achak Deng. It highlights and explains the terrible events in Sudan while making pointed comments about the USA; it’s still pretty exuberant, though.

Contemporary literary fiction, then, is made up by these two divergent trends – the more experimental, the more seeming ‘real’. They can be picked up in all sorts of fiction (even genre fiction: real life thrillers, for example) and even in non-fiction (who’d have thought that an account of financial mismanagement would be so gripping – but John Lanchester’s novelistic account of the credit crunch, Whoops!, really is). Perhaps these trends, and their blurring, is telling us something important about the world in which we live.

Robert Eaglestone is Professor of Contemporary Literature and Thought at Royal Holloway, University of London. He is Deputy Director (and formerly Director) of the Holocaust Research Centre. His research interests are in contemporary literature and literary theory, contemporary philosophy, and on Holocaust and genocide studies. He is the author of Contemporary Fiction: A Very Short Introduction (OUP, 2013) and Doing English: A Guide for Literature Students (third revised edition) (Routledge, 2009). You can follow him on Twitter: @BobEaglestone.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: David Mitchell by Mariusz Kubik (Attribution, GFDL), Creative Commons Licence via Wikimedia Commons; Virginia Woolf by George Charles Beresford [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Book groups and the latest ‘it’ novel appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLady Chatterley’s Lover and the politics of “variable obscenity”Nelson Mandela: a precursor to Barack ObamaUS Independence Day author Q&A: part four

Related StoriesLady Chatterley’s Lover and the politics of “variable obscenity”Nelson Mandela: a precursor to Barack ObamaUS Independence Day author Q&A: part four

July 11, 2013

A sweet, sweet song of salvation: the stars of Jesus rock

The Jesus People movement emerged in the 1960s within the hippie counterculture as the Flower Children rubbed shoulders with America’s pervasive evangelical subculture. While the first major pockets of the movement appeared in California, smaller groups of “Jesus freaks” popped up—seemingly spontaneously—across the country in the late Sixties. After a heavy dose of publicity in the early 1970s, the Jesus People became a national evangelical youth culture that spread across the United States, appealing especially to church-going youth within conservative Protestant circles which had, until that time, strongly resisted the blandishments of worldly entertainments and the allure of youth culture.

One of the most important elements of this popular religious movement was the music which emanated from within its ranks. Hiley Ward, a Detroit reporter who toured a number of Jesus People communes and groups in the early ‘70s noted their “preoccupation with new music,” and a Time cover story in the summer of 1971 noted that music “was the special medium of the Jesus People.” Not only did they write songs for their own devotional edification and worship services, but they utilized the new music to evangelize—and entertain—their generational peers in home Bible studies, coffeehouses, impromptu street concerts, high school auditoriums, and concert halls. In the process, an entirely new subgenre of American pop music—“Jesus Music”—developed around an army of musicians that included an assemblage of guitar-plunking coffeehouse troubadours, straight-on hard rock bands with regional followings, and secular rock musicians who had undergone a conversion experience and left the mainstream music business behind.

While it was dwarfed by the larger world of big time rock ‘n’ roll, Jesus Music nonetheless became its own parallel universe featuring networks of local venues, recording contracts and record labels, annual music festivals, and artists who sold hundreds of thousands of records to the dedicated Jesus People fan base. Eventually, Jesus Music would attract the attention (and dollars) of major music corporations and—as it morphed into “Contemporary Christian Music” in the 1980s—go on to claim a larger share of the American musical market than classical, jazz, Latin, and New Age music combined.

Below is a guide to some of the most popular music acts of the 1970s that many American youth of that era never heard of—the stars of Jesus Music:

#1: Love Song:

The Calvary Chapel-based band Love Song ca. 1972; top, l. to r.: Jay Mehler, Chuck Girard, Tommy Coomes; bottom, l. to r: Jay Truax, Fred Field. Courtesy of Calvary Chapel.

Suburban Orange County, CA, was one of the Jesus movement’s earliest hot spots. Love Song was the major house band at the biggest Jesus People center in that area, Calvary Chapel in Costa Mesa. Their eponymous 1971 debut album sold over 250,000 copies and had a revolutionary impact on evangelical teens’ music listening habits and tastes.

#2: Larry Norman

The “Father of Christian Rock,” Larry Norman, performing at the Hollywood Paladium ca. 1970. Courtesy of Archives, Hubbard Library, Fuller Theological Seminary.

Larry Norman is considered the “grandfather of Christian rock.” A former member of the San Jose-based band People! (their 1968 hit “I Love You [But the Words Won’t Come]” placed in the Billboard Top 20), Norman became a major component of the Los Angeles Jesus People scene and developed a national following. Fans of Contemporary Christian Music still consider his 1973 album Only Visiting This Planet one of the best the genre has ever produced.

#3: “e”

A publicity shot for a leading Midwestern Jesus band: “e” of Indianapolis ca. 1972. Courtesy of Ron Rendleman.

A five-member rock unit hailing from the Indianapolis area, “e” was an example of one of the Jesus rock bands that developed a strong regional following at coffeehouses, concerts, and music festivals throughout the Midwest in the early and mid-70s.

#4: Barry McGuire

Barry McGuire at the 3 day Music & Alternatives festival, New Zealand 1979. From Nambassa Trust and Peter Terry via Wikimedia Commons.

An example of someone with mainstream music success that lent an added dose of “street cred” to the new genre was Barry McGuire, a former member of the New Christy Minstrels who rocketed to the #1 spot on the national charts with his 1966 hit “Eve of Destruction.” Bottomed out on drugs, McGuire found Jesus in 1970 and became a major star in the developing Jesus Music scene.

#5: Jeremy Spencer

Jeremy Spencer, Fleetwood Mac, March 18, 1970 Niedersachsenhalle, Hannover, Germany. Via W.W.Thaler – H. Weber, Hildesheim via Wikimedia Commons.

Fleetwood Mac guitarist Jeremy Spencer was an early convert to the Jesus movement from the world of British rock. While his conversion was avidly-touted in early Jesus People sources, his involvement with an increasingly marginalized group called the Children of God put him on the outs with the gatekeepers of the fledgling Jesus Music business and kept him from developing into a major figure in the world of Jesus Music.

#6: Nancy “Honeytree” Henigbaum

Courtesy of Nancy Honeytree Miller.

The first generation of Jesus People musicians was dominated by male singers and bands. One of the exceptions was Honeytree (Nancy Henigbaum—“Honeytree” was a literal translation of her German surname) who started out as a secretary for the Adam’s Apple coffeehouse in Ft. Wayne, IN. Armed with just her voice and guitar she began leading “worship times” and eventually began performing on the coffeehouse circuit. Honeytree’s first album—produced on a budget of $2,500—was picked up by Texas-based Word Records in 1973, fulfilling a national musical niche for a Jesus People version of ‘70s singer-songwriters like Carole King.

#7: Keith Green

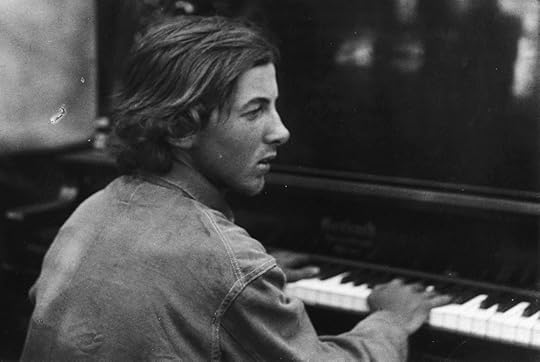

Keith Gordon Green, an American gospel singer, songwriter, musician, and Contemporary Christian Music artist. From Last Days Ministries via Wikimedia Commons.

The catchy pop of piano-playing, singer-songwriter Keith Green made him the artist many Jesus Music fans thought might become the first “crossover” onto the secular charts. But Green became increasingly “prophetic” in his renunciation of sin and materialism as the ’70s moved on and strained his relationships with the executives of the nascent Contemporary Christian music industry. He was killed, along with two of his children and nine others, in a 1982 plane crash in Texas.

A “Stars of Early Jesus Music” playlist:

Larry Eskridge was born in North Carolina and raised in the Chicago area, where he was involved with the Jesus People movement in the 1970s. A student of evangelicals’ relationship to mass media and pop culture, he has been on the staff of the Institute for the Study of American Evangelicals at Wheaton College since 1988. He is the author of God’s Forever Family: The Jesus People Movement in America.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A sweet, sweet song of salvation: the stars of Jesus rock appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSeven things you didn’t know about “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”Creativity in the social sciencesUntied threads

Related StoriesSeven things you didn’t know about “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”Creativity in the social sciencesUntied threads

Untied threads

Unidentified key players are the bane of biographers, who cannot resist the urge to tie all the knots. In my case, writing about the extraordinary life of the composer Henry Cowell, two people resisted identification, both of them connected with the sad story of Cowell’s imprisonment on a morals charge. The offense was so minor — a single act of consensual oral sex with an adult — that even the district attorney later said that if Cowell hadn’t misguidedly pleaded guilty, the offense would never have been prosecuted. By pleading guilty, Cowell landed himself with fifteen years in San Quentin, of which he served four. To say it was a tragedy is to grotesquely understate what happened.

During the lengthy struggle to gain parole, a woman named Helen Hope Page suddenly appeared. She did not know Cowell but admired his work and wanted to help, which she did, constantly reminding him and his stepmother (who was coordinating all the parole efforts) to keep her efforts utterly secret because she was a neighbor of a member of the parole board, and her position in their town, Oakdale, would be terribly damaged if anyone found out. All that I could learn about her was that she lived in Oakdale, had some health problems, a cat, and either she or her presumed husband had a connection with a Stockton, California newspaper. Page seemed to know everyone; she even proposed linking up Cowell’s stepmother with Eleanor Roosevelt. Beyond that, I found nothing. Learning that Yale has some correspondence between Page and Carl Sandburg, I made contact and learned that the library also had no idea who Page was.

I was therefore quite surprised, a few months after the biography was published, to receive an email from someone whose name meant nothing to me, providing me with fascinating information about Page: her birth and death years, the fact that she was editor of the Oakdale branch of the Stockton newspaper, the probability that she was gay, and her birth name. The author presumed that the name Page came from a former husband. Astonished, I asked about the identity of my correspondent. He identified himself as a civil court judge in Vienna, who had a strong interest in American music, came across my book, and read it on a very long train ride. He was able to find Page because, as a civil court judge, he was fluent in the many sophisticated genealogical research tools.

Henry Cowell playing the piano, ca. 1913. Copyright Sidney Robertson Cowell. Cowell Collection at the NYPL. Used with permission.

His second discovery was even more interesting. Sidney Cowell said more than once that her husband was protected from sexual assault in San Quentin by a violinist who was the ranking murderer and could put out a “do not touch” order. She assumed that the violinist was one Raoul Pereira, a former pupil of Brahms’s close friend Joseph Joachim. Pereira, however, was in for passing bad checks. The only other possible candidate seemed to be the director of the prison band, an inmate named W. E. J. Hendricks. Cowell knew Hendricks well. He was deeply involved in the band, playing flute (extremely badly, he said) acting as its librarian, doing preparatory rehearsals, and eventually conducting some concerts. He and Hendricks worked together to upgrade the repertory. He does not mention him as a violinist, but seems to have thought highly of Hendricks’ ability. Hendricks was also described in complimentary terms in the autobiography of Clinton Duffy, the reformer appointed Warden in 1940 by Democratic Governor Culbert Olson to clean up the notoriously violent prison, whose guards happily beat up prisoners or consigned them to a horrible dungeon. Although Duffy came in just after Cowell was paroled, he knew the prison very well, having grown up in it as a guard’s son. Since Duffy was clearly a good man, a compliment from Duffy carried weight. Duffy felt Hendricks was an intelligent and basically good man, who could have contributed to society if he had not broken parole and disappeared when he got out a couple of years after Cowell. Hendricks therefore could have decided to protect Cowell, but did he really have the clout? After all, the prisoners included some completely amoral and viciously violent men. Sexual assaults were the plague of the prison.

I should have sent for Hendricks’ file from the California archives, but became so wary of going down peripheral paths that I didn’t. I assumed that if Hendricks got out relatively quickly, he was probably in for a crime of passion. It didn’t seem to matter much in the context of Cowell’s life. My Viennese correspondent had started under the same assumption, but sent for the file and found a different picture. Hendricks and a buddy had robbed and strangled a fellow resident in a World War I veterans’ home and dumped his body into a ravine in Los Angeles dressed only in a belt and the necktie with which they had strangled him. Hendricks got life, but was eligible to be out in 9 years. He, a murderer, and Cowell, a very minor sex offender, would have to serve the same amount of time! Most interesting of all the items in the file, however, was an article from the Utah Republican printed when Hendricks was paroled. Fueled by outrage over Hendricks’ parole, the article is a vicious, gratuitous attack on Warden Duffy – who, recall, was a Democratic appointee. The newspaper claimed that Duffy did not run San Quentin; Hendricks did.

Although one would be hesitant to take the story literally, it is reasonable to think that Hendricks, the band conductor and vicious murderer, was indeed in a position to protect Henry Cowell. Thanks for doing it, Hendricks!

Joel Sachs is Professor of Music History, Chamber Music, and New Music Performance at The Juilliard School, where he conducts the New Juilliard Ensemble. He is the author of Henry Cowell: A Man Made of Music. Read his previous blog posts on Henry Cowell: “Henry Cowell’s Imprisonment” and “Unravelling the life of Henry Cowell without unravelling the biographer.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Untied threads appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSeven things you didn’t know about “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”Thinking through comedy from Fey to FeoFlutes and flatterers

Related StoriesSeven things you didn’t know about “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”Thinking through comedy from Fey to FeoFlutes and flatterers

Cooperation through unproductive costs

What do prison gangs, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Ultra-Orthodox Jews have in common? All of these groups require highly-visible “costs” that reduce their members’ opportunities in the outside world. Prison gangs often require tattoos, Jehovah’s Witnesses demand significant time from there members, and Ultra-Orthodox Jews require a style of dress that is far from fashionable. Examples of groups that have similar costly requirements abound: fraternities haze their members, tribes perform ritual scarring, cults require public proselytization efforts, and so on. To an economist, it is not obvious why groups would require such costly behavior from their members. How is it possible that groups can not only form, but thrive, by requiring their members to reduce their outside options?

Prison gang tattoo

In a 1992 article, Laurence Iannaccone was the first to provide an economic rationale for such behavior. He argued that prohibitions on otherwise normal behavior — including restrictions on dress, diet, grooming, entertainment, economic activity, sexual conduct, and social interactions — served a distinct economic purpose. This is, namely, that highly-visible prohibitions help groups keep out people who want to enjoy the benefits of group membership without contributing to the group. This is important for the survival of these groups, as many of them thrive precisely because all members are committed to the cause.

Yet, the very nature of these groups makes it difficult to ignore alternative explanations for their behavior. Certainly, most insiders would not claim that the costs they face are economic ones, but are time-honored traditions, hidden truths, or directly productive behavior. Conversely, critics of these groups emphasize ignorance, indoctrination, coercion, or outright irrationality. Others claim that most examples of seemingly bizarre beliefs and behavior simply reflect atypical preferences.

We attempted to discern between these competing hypotheses by formulating a laboratory experiment that is completely devoid of ideologies, deviant tastes, intense interactions, outcast identities, or any other special feature of cults, communes, clans, and the like. In this experiment, subjects were asked to divide a pool of money between contributions to their group and their own account. Like the groups we were concerned with, any contribution to the group were multiplied, so giving to the group increased the overall wealth of members. Of course, there was also a significant incentive to keep all the money for oneself while benefitting from the generosity of one’s group members. This is precisely the type of problem faced by cults, communes, and the like: they provide “goods” to group members, but these goods are available only if everyone contributes.

We attempted to discern between these competing hypotheses by formulating a laboratory experiment that is completely devoid of ideologies, deviant tastes, intense interactions, outcast identities, or any other special feature of cults, communes, clans, and the like. In this experiment, subjects were asked to divide a pool of money between contributions to their group and their own account. Like the groups we were concerned with, any contribution to the group were multiplied, so giving to the group increased the overall wealth of members. Of course, there was also a significant incentive to keep all the money for oneself while benefitting from the generosity of one’s group members. This is precisely the type of problem faced by cults, communes, and the like: they provide “goods” to group members, but these goods are available only if everyone contributes.

The experiment described above is well-known in experimental economics as a “voluntary contribution mechanism.” In our experiment, we added a twist: subjects can also choose which groups to enter, with groups differentiated by the portion of money one kept when they contributed to their own account. In “high sacrifice” groups, every dollar that is kept turns into a payment of fifty-five cents at the conclusion of the experiment. Subjects in these groups were figuratively burning forty-five cents for every dollar that they did not contribute to the group. Economically, this is similar to what happens to members of the groups described above. For example, getting a highly-visible tattoo may make one a member of a prison gang (giving access to all of the associated benefits), but it also greatly reduces the wages one can make when out of prison.

One might ask, “Why would anyone voluntarily join a group where a good portion of their private (non-group) money is burned?” Iannaccone’s insight suggests that these groups thrive only if people entering these groups give more to the group once they are a member. In our experiment, this is precisely what we find. When given the option to effectively destroy a portion of their private productivity, with no compensation but the prospect of being grouped with like-minded others, more than half of all people we determined to be “cooperators” did so. But “non-cooperators” overwhelmingly rejected the offer, thus enabling cooperative “sacrificers” to greatly increase their group’s output. Nor was this the only effect; contributions averaged around 85% of total endowment in the most costly groups, 35% in the moderately costly groups, and 15% in the least costly groups. In our experiment, these seemingly unproductive costs thus did their job: they prevented people who do not give to the group from entering, and they encouraged greater giving to the group once groups were formed. In short, we were able to carry a popular theory into the lab and subject it to a relatively clean test.

Our results demonstrate that sacrifice can enhance collective action and raise individual welfare, even in an austere laboratory environment. It does not require a specific set of beliefs, shared identity, or spiritual context. Sacrifice is a means by which any group can potentially harness the commitment and collective capacity of its members. Whether it is military units or sports clubs, prison gangs or organic food cooperatives, we shouldn’t be surprised that our closest knit, most successful groups are built around a shared sacrifice.

Jason A. Aimone, Laurence R. Iannaccone, Michael D. Makowsky, and Jared Rubin are authors of “Endogenous Group Formation via Unproductive Costs”, published in The Review of Economic Studies. Jason A. Aimone is an assistant professor at Baylor University and a post-doctoral researcher at the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute. His research uses the tools of experimental and neuroeconomics to explore economic behavior and decision-making. Laurence Iannaccone is Professor of Economics at Chapman University, Director of Chapman’s Institute for the Study of Religion, Economics, and Society, (IRES) and the President of the Association for the Study of Religion, Economics, and Culture (ASREC). Michael D. Makowsky is an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University. His research explores the variety of ways in which groups form and the patterns that emerge within their constituent and collective behavioral norms. Jared Rubin is an assistant professor at Chapman University. His research focuses on relationship between political and religious institutions and their role in economic development.

The Review of Economic Studies aims to encourage research in theoretical and applied economics, especially by young economists. It is widely recognised as one of the core top-five economics journal, with a reputation for publishing path-breaking papers, and is essential reading for economists.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1)Prison gang tattoo [public domain], via the US Department of Justice (2) Polish postcard depicting some Hasidic boys, circa World War I [public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Cooperation through unproductive costs appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBeware of gifts near elections: Cyprus and the EurozoneLady Chatterley’s Lover and the politics of “variable obscenity”Thinking through comedy from Fey to Feo

Related StoriesBeware of gifts near elections: Cyprus and the EurozoneLady Chatterley’s Lover and the politics of “variable obscenity”Thinking through comedy from Fey to Feo

July 10, 2013

Flutes and flatterers

The names of musical instruments constitute one of the most intriguing chapters in the science and pseudoscience of etymology. Many such names travel from land to land, and we are surprised when a word with romantic overtones reveals a prosaic origin. For example, lute is from Arabic (al’ud: the definite article followed by a word for “wood, timber”). The haunting lines by Duncan Campbell Scott (“I have done. Put by the lute”) don’t make us think of “the wood.” In everyday life it is usually preferable not to know the derivation of the words we use. Harp and fiddle fare no better than lute. Both are, in my opinion, Germanic. The verb harp as in harping on one note supplies a clue to the etymology of the noun harp (also think about harpoons) and phrases like fiddling with something or fiddle away shed light on how fiddle began its career. (Dictionaries assert that fiddle is a borrowing of Romance vitula, but vitula is, more likely, a borrowing from Germanic.) Harp and fiddle are unpretentious, homey words. They convey the idea of plucking the strings or moving the bow (just call it fiddlestick) over them.

A few curious things can be said about flute (which, of course, has nothing to do with lute). Unlike fiddle, this word is certainly of Romance descent. Vowels in it differed and still differ from language to language (see the display at the end of this post), but fl and t remain constant, and it is fl- that deserves our attention. In numerous Indo-European languages, especially in Germanic and Romance, initial fl-, bl-, and pl- have a sound symbolic or a sound imitative value and are connected with words for flying, flowing, floating, and blowing. Hence many puzzles. For example, fluent is a participle of Latin fluere “to flow.” At first sight, flow and fluere are congeners. Yet they cannot belong together, because the Latin consonant corresponding to Engl. f happens to be p, as in father ~ pater, not f, and, to be sure, we find Latin pluere “to rain,” a perfect cognate of flow as regards sound and sense. What then should we do with fluere in its relation to flow, a verb rhyming with pluere and belonging to the same semantic sphere? What is the origin of this confusion? No one has a definite answer. In any case, the often-repeated explanation that fluere should be kept apart from flow, which has modified its sense under the influence of the Latin verb, does not rest on any evidence. It is wishful thinking, for how can one demonstrate influence? The other explanation refers to the sound symbolism common to Latin and Germanic (the “fluiditiy” of fl-), but, although sound symbolism unquestionably exists, when it comes to concrete cases, adducing proof constitutes a problem.

One can imagine that wind instruments, including several varieties of the flute, are among the most ancient of all, since some kind of bulrush was widely available and shepherds always needed pipes. Blowing into a reed, the way King Midas’s barber did, and producing some primitive music would not have been too difficult. According to another Greek myth, Athena invented an aulós, usually translated as “oboe,” but threw it away because it distorted her face (or so she thought). Although indifferent to amorous pursuits, she was quite particular about her good looks. The satyr Marsyas picked up the instrument and learned to play it so well that he challenged Apollo to a contest in music. He lost, and the vengeful god, who did not brook competition, flayed him alive. Even if the aulós designated the oboe, the verb auléo is glossed in Greek dictionaries as “play the pipe or flute,” which is not surprising, for the root of the word signified a hollow tube (those who care to learn more about this root may look up alveolus ~ alveoli in English etymological dictionaries). Apparently, the idea behind the naming of those instruments was blowing: compare Engl. the winds. In other languages, the notion of blowing in the generic name of the winds comes to the foreground even more strongly. Whistling (as in Russian svirel’ “pipe”; stress on the last syllable) and chirping (as in pipe; Latin pipare “chirp”) are also close by. A phonetic variant of pipe is fife, related to Gaelic piob.

An illustration of the Pied Piper by Kate Greenaway from The Pied Piper of Hamelin, by Robert Browning, public domain via Project Gutenberg and Wikimedia Commons.

Of course, there can be other associations. The poet Vladimir Mayakovski likened the flute, with its keys and blowholes, to the human spine, and the Romans called the flute tibia “shin.” But reference to blowing prevails, and where blowing appears, the group fl- is close by. Therefore, the stern conclusion of The Century Dictionary (at flute) should, I believe, be taken with a grain of salt: “Ultimate derivation unknown. The common derivation, through a supposed Medieval Latin *flatuare, from Latin flatus, a blowing, flare… is untenable” (an asterisk designates a form, reconstructed but not attested in written records; the great Romance philologist Friedrich C. Diez wanted *flatuare to become *flautare and thus yield the desired combination flaut-). Nor did Murray think much of the flatuare idea. “Ultimate origin unknown” is what most modern dictionaries prefer to say about flute, though Skeat remained at least partly noncommittal: “Of uncertain origin. The fl may have been suggested by Latin flare, to blow.” This is a familiar motif: we have already witnessed the attempt to solve the flow ~ fluere riddle in the same way.

Sound imitative words tend to resemble one another like people wearing the same uniform. Yet belonging to the same regiment does not amount to blood kinship. “The ultimate origin” of flute is indeed unknown, but the word may be onomatopoeic. It is a seldom-mentioned fact that English recognizes the flute as a hollow tube or channel. The connection can be discerned only in a past participle: a fluted column, for instance, is one decorated with flutings (carved vertical grooves).

Any instrument has the capacity of producing dulcet or harsh notes. There is the dialectal word Fladuse in Low (= northern) German. It means “flattery,” from the antiquated French phrase fleute douce “sweet flute,” supposedly, coined under the influence (!) of French flatter “to flatter.” But couldn’t the idea of sweet sounds suggest flattery directly, without any “influence”? The origin of flatter has been hotly contested. I support the hypothesis that the word was coined in Germanic and meant “flutter around the person whose favors one wishes to obtain,” with the French verb having been borrowed from Middle English. Flutter, flitter, and flatter begin with the group fl- that we find in flute. In English, contrary to German, flute left a jeering echo. Rather probably, flout has been taken over from Middle Dutch. In Modern Dutch, fluiten has the expected sense “whistle; play the flute,” but many centuries ago it also meant “mock, jibe”; German pfeifen carries similar connotations. It only remains for me to list the numerous forms in which the word flute has been recorded in the old and modern Romance languages: fleute, flaute, flauto, flahute, flavuto, frauto, flaguto…, but flageolet is seemingly not related to any of them.

Its origin is (alas!) unknown, but I find it hard to believe that the paths of flare, flute, and flageolet have not crossed more than once. “Blow, winds, crack your cheeks! rage! blow!” But we will not leave the shelter of the wall and from our secure corner play sweet tunes, flatter the ancient gods, and flout the elements.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Flutes and flatterers appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhen it rains, it does not necessarily pourMonthly etymological gleanings for June 2013Multifarious Devils, part 4. Goblin

Related StoriesWhen it rains, it does not necessarily pourMonthly etymological gleanings for June 2013Multifarious Devils, part 4. Goblin

Nine curiosities about Ancient Greek drama

The International Festival of Ancient Greek Drama held annually in Cyprus during the month of July. Since its beginning in 1996, the festival has reimagined performances from the great Ancient Greek playwrights, so we dug into J.C. McKeown’s A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities for some of the lesser known facts about Ancient Greek theatre. Here are nine weird and wonderful facts about the plays, playwrights, and spectators of the time.

Sophocles’ Oedipus the King is regarded by many as the greatest surviving tragedy, but the trilogy in which it appears was beaten into second place by Aeschylus’s nephew, Philocles, of whose hundred or so plays almost nothing survives. Alexander wanted to have a stage made of bronze for his theatre in Pella, but the architect refused to follow his instructions since that would ruin the actor’s voices.

There were officials in the theatre who carried canes to ensure good order among the spectators.

There were officials in the theatre who carried canes to ensure good order among the spectators.

Anaxandrides was rather sour tempered. If ever his comedies failed to win, he did not revise them as most dramatists do; instead he let them be cut up and used as wrappers in the perfume market.

Sophocles used to criticize Aeschylus for writing his plays while drunk, saying that “Even though he composes as he should, he does so without being aware of what he is doing.”

At the festival in honour of Dionysius, there was a keen competition for the seats, involving some of the citizens in violence and injury. So the people decided that admission should no longer be free. A charge for seating was imposed, but the poor were disadvantaged because the rich could easily afford to pay for this. A decree was then passed limiting the charge to one drachma, and they called it “the price for plays”.

A story about the unusual nature of Aeschylus’s death made it worth recording. He went outside the walls of the Sicilian city in which he was staying and sat down in a sunny spot. An eagle flying over with a tortoise in its talons mistook his shiny head for a stone. It dropped the tortoise on Aeschylus’s head so that it could break its shell and eat its flesh.

The story of Euripides death has tragic overtones. Euripides was returning from dinner with King Archelaus of Macedon, when he was torn to pieces by dogs set on him by some jealous rival. In the Bacchae, one of the plays in Euripides’s final trilogy, Pentheus is torn apart by his female kinsfolk.

Tragedy: the original meaning is generally agreed to be “goat song” (from tragos and ode), either because the actors originally dressed up as goats, or because the prize for victory in dramatic competitions was a goat.

Avenging the murder of Agamemnon is the only story treated by all three great tragedians in extant plays.

J.C. McKeown is Professor of Classics at the University of Wisconsin Madison, co-editor of the Oxford Anthology of Roman Literature, and author of Classical Latin: An Introductory Course and A Cabinet of Roman Curiosities. He is the author of A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities published by OUP in July 2013.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles via email or RSS.

Image credit: Sophocles. Cast of a bust of the Farnese Collection (now in Naples) in the Pushkin Museum. Photo by Shako. Creative Commons license via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Nine curiosities about Ancient Greek drama appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDemystifying the Hanging Garden of BabylonLady Chatterley’s Lover and the politics of “variable obscenity”Thinking through comedy from Fey to Feo

Related StoriesDemystifying the Hanging Garden of BabylonLady Chatterley’s Lover and the politics of “variable obscenity”Thinking through comedy from Fey to Feo

Can religion evolve?

On the last page of On The Origin of Species, Charles Darwin turns from millions of years of natural selection in the past to what he calls a “future of equally inappreciable length” and ventures the judgment that “all corporeal and mental endowments will tend to progress to perfection.”

A heady thought. And just a tad overstated, most contemporary Darwinians would say. The directions evolution will take in the billion years or so left for life on Earth will depend on unforeseeable changes. For all we know, evolution in the far distant future may proceed quite without us — and indeed without any beings smarter than a goldfish.

Yes, for all we know. But by the same token, things could turn out rather differently. A lot can happen in ten million centuries: maybe we or future species will advance science and philosophy significantly. Something similar might be said about politics, art, and athletics. Few who are at all acquainted with evolution and geological time would disagree with these maybes.

But what about religion? It’s amusing how quickly a large chorus of voices shouts “No!” Religious zealots, of course, are in the chorus. They think their current religious beliefs and practices can bear the weight of eternity. But also in the chorus — way off to the other side — are a bunch of contemporary evolutionary thinkers, who find religion ridiculous and regard it as on the way out.

Why should religion alone, of all the main areas of human life, be regarded as incapable of evolving, and in a manner leading to improvements? At least part of the answer, I suspect, is that traditional religion is emotionally sticky, the flypapery sundew of the ideological world. Because it still holds us in its sway, both negatively and positively stirring the emotions, even intellectuals are led to fixate on its particular forms and doctrines and effects, as though religion could never be anything else.

But this can’t possibly be the right way to think about religion. Evolutionists, it seems, have a lot to tell us about it that they have not yet learned.

This suggests itself all the more insistently when we set that big future for life on Earth mentioned a moment ago – that billion years – alongside the piddly few thousand years humans have so far spent in a semi-reflective frame of mind. When I represent a billion years with a twenty-foot chalk line for my students, they’re shocked to discover that those several thousand years, which to our ears have such an impressive ring, move us forward from the starting point less than one seven hundredth of an inch. And we think our best religious efforts are behind us!

Well, maybe they are. Perhaps for ten million centuries our descendants will glorify us for having drained religion dry in only a second of scientific time. But is it reasonable to believe this? One wonders what developments in thinking and feeling the world might see in so much time. How primitive religiously would we seem to intelligent beings evolved from us even a few million years from now? Contemplating such thoughts, one begins to wonder whether the very idea of our primitivity contains the germ of some interesting religious developments. What would religion in our own time look like if it were developed while holding this idea of our primitivity firmly in mind? Might it be more rational? Might it also become more useful, an aid in the project of ensuring human survival over the long term?

Consider, for example, our tendency today to identify religiousness with the mental state of believing. Maybe religion is not ready for belief. Moreover, there are other attitudes capable of sustaining a religious commitment with which the idea of an ultimate divine reality can be addressed — might I suggest imagination? And we may soon discover them.

Or consider the idea of God. The cognitive science of religion tells us that humans are strangely drawn to agent-centered notions of the divine. But for evolutionists, this has to be qualified: humans at present. After all, the beginning is near. It’s right behind us! Maybe the idea of a person-like God will be one of our first – and unsuccessful – attempts to think beyond ourselves. And while they pore over the possibilities, maybe religious types who are wise to our evolutionary immaturity will learn to take as the most fundamental object of their imagination something far more general than the idea of God. (An evolutionary rationale for the much denigrated tendency of liberal theologians to say little about the nature of the divine – who knew?)

The interesting thing is that no one has seen the evolutionary door to such thoughts about religion being opened.

Darwin himself seems not to have seen it. His remark about the deep future came in a rare moment, and his own thoughts about religion were preoccupied with its traditional forms. Contemporary evolutionary theists and pantheists haven’t seen it. They stand by Darwin’s door looking back, either still preoccupied with the traditional God idea, trying to reconcile it with the gory facts of natural selection, or else absorbed in wonderment over the processes that have led from the deep past to us while ignoring the deep future. Theologians of a reductionist bent haven’t noticed Darwin’s door opening either. Instead they merrily throw out the holy religious baby with its unholy bathwater, dealing with traditional religion’s implausible claims about reality by seeking to dissociate religion entirely from claims about reality. Certainly evolutionary irreligionists like Richard Dawkins haven’t seen it. They’re too busy using the shortcomings of much existing religion to help spread the belief — as premature at our stage of development as religious belief — that there is no more to reality than the natural facts science can track.

The deep future, as we will discover, has radical consequences for all such thinking about religion. Most of them have not yet been noticed, let alone absorbed. So look out! If we dare to walk through the door Darwin left open, religion and evolution could become a hot topic in ways we have not yet dreamed.

J. L. Schellenberg is Professor of Philosophy at Mount Saint Vincent University in Canada and Adjunct Professor in the Faculty of Graduate Studies at Dalhousie University. His first book was Divine Hiddenness and Human Reason (Cornell, 1993) and his most recent is Evolutionary Religion (OUP, 2013).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Evolution art by Ade McO-Campbell (own work), Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Can religion evolve? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEp. 4.5 – RELIGION (Part 2)Ep. 4.5 – RELIGION (Part 2) - EnclosureCreativity in the social sciences

Related StoriesEp. 4.5 – RELIGION (Part 2)Ep. 4.5 – RELIGION (Part 2) - EnclosureCreativity in the social sciences

July 9, 2013

Seven things you didn’t know about “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”

Photo by Det N., CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

“Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” the iconic hit featured on the Beatles’ much-celebrated 1967 album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, is probably among one of the most mesmerizing and musically inventive Billboard-toppers of all time. Described by Rolling Stone magazine as “Lennon’s lavish daydream,” everything from “Lucy’s” illusive lyrics to its complex arrangement has enhanced the psychedelic tune’s enduring power – and legacy. Here are seven lesser-known facts about the inspiration, composition, and reverberating impact of this rock ‘n’ roll classic, from Lucy in the Mind of Lennon .1) It was banned by the BBC (British Broadcasting Company) for what they thought were thinly-veiled drug references. Speculations that the song’s title was a clever mnemonic for the psychedelic drug LSD, and that lyrical content of the song itself detailed the band’s experience with drug experimentation, never quite escaped Lennon, who denied those rumors up until his death in 1980. “It was purely unconscious that it came out to be LSD,” he insisted. “Until somebody pointed it out, I never even thought of it. I mean, who would ever bother to look at initials of a title? It’s not an acid song.” (Source: All We Are Saying, David Sheff)

2) In fact, “Lucy’s” song title was actually inspired by a picture that Lennon’s then four-year-old son, Julian, painted of classmate Lucy O’Donnell. “I was trundled home from school and came walking up with one of my watercolor paintings,” Julian recalled years later in an attempt to address popular misconception. “It was just a bunch of stars and this blonde girl I knew at school. And Dad said, ‘What’s this?’ I said, ‘It’s Lucy in the sky!’” The Beatles’ 1968 Christmas Record also featured another of Julian’s drawings. (Source: Hey Jules)

3) The dream-like images referenced in Lennon’s song lyrics were inspired by imagery from Lewis Carroll’s Alice In Wonderland. “The images were from Alice In Wonderland,” said Lennon in 1980. “It was Alice in the boat. She is buying an egg and it turns into Humpty-Dumpty. The woman serving in the shop turns into a sheep, and the next minute they are rowing in a rowing boat somewhere and I was visualising that. There was also the image of the female who would someday come save me – a ‘girl with kaleidoscope eyes’ who would come out of the sky. It turned out to be Yoko, though I hadn’t met Yoko yet. So maybe it should be Yoko In The Sky With Diamonds.” (Source: All We Are Saying, David Sheff)

4) George Harrison played a tambura on this song. A long-necked lute played in Macedonia and Bulgaria, the tambura is a stringed folk instrument that is similar to a mandolin. Harrison had previously incorporated tambura samples in other tracks featured on the Beatles’ 1966 album Revolver, including “Tomorrow Never Knows.”

5) In 1974, this cover of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” was a #1 hit for Elton John.

Click here to view the embedded video.

6) Actor William Shatner also covered the song in dramatic, spoken-word style.

Click here to view the embedded video.

7) A group called John Fred and his Playboy Band had a #1 hit in 1968 with “Judy In Disguise (with Glasses),” a song that was a parody of “Lucy.”

Click here to view the embedded video.

And now a “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” cover playlist:

Tim Kasser is Professor and Chair of Psychology at Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois. He is the author of Lucy in the Mind of Lennon, and has published numerous scientific articles and book chapters on materialism, values, and goals, among other topics.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Seven things you didn’t know about “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThinking through comedy from Fey to FeoAn Oxford Companion to WimbledonSix surprising facts about “God Bless America”

Related StoriesThinking through comedy from Fey to FeoAn Oxford Companion to WimbledonSix surprising facts about “God Bless America”

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers