Oxford University Press's Blog, page 897

October 2, 2013

Ostentatious breeches, gods’ braggadocio, and ars poetica

As promised, I am returning to the English verb brag and the Old Scandinavian god Bragi (see the previous post). If compared with boast, brag would seem to be more suggestive of bluster and hot air. Yet both may have been specimens of Middle English slang or expressive formations; hence perhaps the obscurity of their origin. The OED gives a summary of the attempts to trace brag to its source. Since the time the first volume of the great dictionary appeared (1884) the situation has not become significantly clearer. The latest publication on the subject (2002), in which the author argues for the Scandinavian derivation of brag, also left several stones unturned.

When Skeat began publishing his dictionary (1882), he quite naturally felt more confident than three decades later. Study of etymology teaches its practitioners caution and humility: the older and the more experienced they become, the less positive they feel about many things (but then such is the way of all scholarly flesh). In the first edition of his dictionary, Skeat insisted that brag was a Celtic word because its putative etymon has been recorded in all (he stressed: all) the Celtic languages. However, he soon gave up his idea. Perhaps, after all, the Celtic verbs were borrowed from English. But this conclusion also has an element of uncertainty. Brag is not such a common word as to be taken over by the speakers of other, even neighboring, countries with unreserved enthusiasm. To be sure, it may have enjoyed greater popularity in the Middle Ages (there is no way of knowing).

Despite the pessimistic tenor of the introduction, it will be wrong to say that absolutely no progress has been made since researchers began pondering the fortunes of brag. French has (had) the noun bragues ~ braies “trousers,” from Latin braca ~ braces, possibly a borrowing in that language. In France, breeches were part of the aristocratic apparel. The lower classes that took part in the French Revolution were called sans-culottes (“without trousers”) for exactly that reason: they wore no “breeches.” According to the French hypothesis of the origin of brag, bragging takes us back to ostentatious clothes. But all the relevant French words were attested centuries later than Engl. brag, so that the connection should be rejected as improbable.

Most likely, brag is a Germanic word. If we disregard as unpromising its comparison with Old Engl. brogne “branch, bough” (this comparison has once been made), we will end up with Old Icelandic braga “shine; glimmer,” bragr “chieftain,” bragr “the art of poetry,” and Bragi, the name of the god of poetry and of the first skald. As usual, semantic bridges are comparatively easy to draw. Poetry was closely connected with its patrons (kings and chieftains), “shine” and “king” form an obvious union, and words for emitting light occasionally also mean “to produce a loud sound” (from a historical point of view, such is, for example, German hell “bright”). Bragging is loud; ostentation and sheen also go together. All this is edifying, but none of the words listed above has any direct connection with boasting. For that reason, Old Engl. (ge)bræc “noise” caught the fancy of many etymologists (ge- is a prefix, æ has the value of a in Modern Eng. brag). Boasting and making a lot of noise go together quite well, but final -c in -bræc (which has the value of Modern Engl. k) and final -g in brag don’t. In Modern English, words ending in -g (tug, leg, rag, drag; bog, bag, fig) are rarely native. But words signifying emotions and those which reached the Standard from the language of “rogues,” such as prig and smug, need not have been borrowings. Therefore, it is at least possible that brag is an expressive variant of brac-, but this is, of course, guesswork.

Most likely, brag is a Germanic word. If we disregard as unpromising its comparison with Old Engl. brogne “branch, bough” (this comparison has once been made), we will end up with Old Icelandic braga “shine; glimmer,” bragr “chieftain,” bragr “the art of poetry,” and Bragi, the name of the god of poetry and of the first skald. As usual, semantic bridges are comparatively easy to draw. Poetry was closely connected with its patrons (kings and chieftains), “shine” and “king” form an obvious union, and words for emitting light occasionally also mean “to produce a loud sound” (from a historical point of view, such is, for example, German hell “bright”). Bragging is loud; ostentation and sheen also go together. All this is edifying, but none of the words listed above has any direct connection with boasting. For that reason, Old Engl. (ge)bræc “noise” caught the fancy of many etymologists (ge- is a prefix, æ has the value of a in Modern Eng. brag). Boasting and making a lot of noise go together quite well, but final -c in -bræc (which has the value of Modern Engl. k) and final -g in brag don’t. In Modern English, words ending in -g (tug, leg, rag, drag; bog, bag, fig) are rarely native. But words signifying emotions and those which reached the Standard from the language of “rogues,” such as prig and smug, need not have been borrowings. Therefore, it is at least possible that brag is an expressive variant of brac-, but this is, of course, guesswork.

Perhaps more can be said about br-, a combination that is habitually associated with noise. Classic examples are Engl. break and Swedish bryta “to break.”(Old Icelandic had brjóta; Old Engl. gebryttan dropped out of the language, but its cognate brittle “breakable, fragile” survived.) Old Engl. breahtm meant “noise; cry; revelry” and “brightness.” Pr- may play a similar role. In German prahlen “to boast,” pr- goes back to br-, but in the Dutch verb pronken “to parade, strut” pr- may be original. At first blush, brag belongs with such br- words. Especially important is Middle High German brogen “boast,” which looks almost like a doublet of Engl. brag (first noted in this context by L. W. van Helten).

Here Franciscus Junius the younger (1591-1677), another Dutch scholar, should be mentioned. In 1743 Edward Lye published his etymological dictionary of English, a work of considerable value even today. Junius compared brag with Old Engl. bregan “to frighten.” The two cannot be connected directly, because bregan had long e, which is incompatible with short a in brag. But, related to bregan, the noun broga (also with a long root vowel) “fright, terror; prodigy” has been recorded, and an Old English verb bragan is not unthinkable (short a and long o alternated according to a regular rule). Bragan, assuming that it is not a ghost word, would have yielded Modern Engl. braw (compare draw from dragen), and I suspect that Engl. brawl (of unknown origin!) is a continuation of this unattested braw with the pseudo-suffix -l, on analogy of bawl, maul, and the like. Old Engl. bragan, which I conjured up to boost my argument, may have had an expressive doublet braggan, and such a form would have become Modern Engl. brag in the same way in which stacga and frocga (cg = gg) became stag and frog. But the more unknowns we add to an etymological equation, the harder it is to justify the result. In any case, the Low German or even native origin of brag seems more probable than its borrowing from Scandinavian. I’ll leave out of account a good deal of etymological bric-à-brac and return to Icelandic bragr and others.

The history of those words is, if possible, even more obscure than that of Engl. brag and its half-invisible kin. The sense “poem” (and, consequently, “the god of poetry”) does not accord too well with bragging or showing off, especially if the semantic nucleus of brag was “making a noise.” The art of poetry was associated with “finding” the best words (so in Old Icelandic and Old English, and such is the meaning of the terms troubadour and trouvère, both of them “finders”), “stitching songs together” (such were the Greek rhapsodes), and producers of merriment or inspiration. Poets, even in a state of ecstasy are not braggarts. They may be called the greatest mullahs (so in Kazakhstan, where an akyn is the winner of a contest of singers), but the reference is hardly ever to boastful shouting. The function of some poets was to mock and deride. The Old English scops at one time supposedly performed such a function. A similar interpretation of Old Icelandic skáld “skald” (“scolder?”) has been offered, but it is problematic. Given the evidence at our disposal, we cannot be sure that the senses “chieftain, prince” in Icelandic have anything to do with “poetry.” We also lack good arguments for connecting the god’s name (divine names are called theonyms) with the secular proper name Bragi. For all such reasons, I would prefer to separate Bragi from Engl. brag. Other researchers have different opinions. And this is exactly the reason why in the entry brag we will always read: “Origin unknown.” Nothing to boast of.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

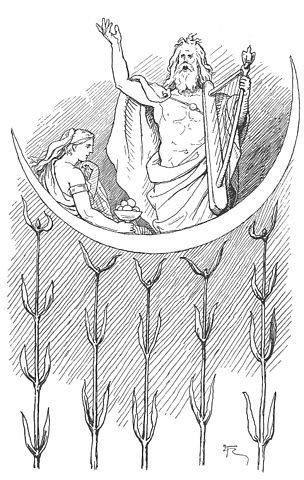

Image credit: The skaldic god Bragi holds a harp and sings while his wife Iðunn holds a bowl of apples in the background. Lorenz Frølich. Published in Gjellerup, Karl (1895). Den ældre Eddas Gudesange. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Ostentatious breeches, gods’ braggadocio, and ars poetica appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEtymology gleanings for September 2013Are you daft or deft? Or, between lunacy and follyNo simplistic etymology of “simpleton”

Related StoriesEtymology gleanings for September 2013Are you daft or deft? Or, between lunacy and follyNo simplistic etymology of “simpleton”

Why is Gandhi relevant to the problem of violence against Indian women?

By Judith M. Brown

The global media has, in recent months, brought to the attention of a world audience the prevalence of violence against women in India. The horrific rape of a woman student, returning home after watching an early evening showing of The Life of Pi, in Delhi in December 2012, and the subsequent trial and conviction of her drunken and violent attackers, has led to considerable comment about violence against women. It ranges from low level harassment on public transport, to rape within and outside marriage, to the murder of brides whose families fail to provide enough dowry, and the abortion of female foetuses. As a result India has an abnormal and skewed sex ratio, demonstrating what Amartya Sen famously called the scandal of India’s millions of “missing women”. A few figures say more than words.

The worst areas for women’s survival are in the north and west of the country. In Punjab there were, in 2011, 893 women to every 1,000 men; in Haryana the female figure was 877 and in Delhi 866

In 2011 24,000 rape cases were reported (over 17% of these in Delhi) and this is just the tip of the iceberg as so many do not get reported

The news service, TrustLaw, ranks India as the worst G20 country in which to be a woman

Why should we think Gandhi, revered as the Father of the Indian nation, had anything relevant to say about this? He is generally thought of as India’s leading nationalist leader in the struggle for independence against the British raj in India in the early 20th century; or as a prophet of non-violence and pioneer of non-violent resistance in the modern world. But this is to underestimate the range of his thinking about India and what sort of nation and country it might become.

Protests in Bangalore following the rape and murder of a young woman in Delhi, December 2012. Photo by Jim Ankan Deka. [CC-BY-SA 3.0]

For Gandhi, independence ( swaraj or self rule) was far more than political independence. It required a radical transformation of Indian social and economic relations — to correct the ills and errors he felt had developed in India under imperial rule. So much of his speaking and writing and his practical work was focussed on these moral “ills”, particularly enmity between people of different religious groups, the treatment of those at the base of Indian society, the appalling depth of poverty for so many, and of course the treatment of women. He was a staunch supporter of women’s health and education, of women’s rights as citizens, and of women’s significant role in the public sphere, particularly in the work of building a new nation. He paid particular attention to the issues surrounding the very early age of marriage, and particularly the plight of child widows who had been married to much older men for reasons of caste. Recognising the violence women faced outside the home he also argued for a profound change in male attitudes — that men should consider all women as if they were their mothers or daughters. As he wrote in 1940, “Woman is described as man’s better half. As long as she does not have the same rights in law as man, so long as the birth of a girl does not receive the same welcome as that of a boy, so long we should know that India is suffering from partial paralysis. Suppression of women is a denial of ahimsa [non-violence].”Of course he was not alone in recognising these problems. From the early 19th century many brave male and female social reformers argued for better treatment of women, for the possibility of widow re-marriage, for the raising of the age of consent and of marriage, and for the education to university level of girls. The result of these multiple campaigns by men and women has been major changes in Indian law. But law on paper and law on the ground are very different. As Gandhi recognised, the absolute fundamental for any serious social change is a change of heart, or perception, of attitudes: in this case it is the need for the change the attitudes of so many men, who see women and girls as disposable items, objects of casual pleasure, not to say second class citizens. Of course this is not to deny that they are many millions of loving, sensitive men in India who treat their female relatives and women in the public sphere with great care and respect. Many of them came out on to the streets to protest at the Delhi rape and engaged in public dialogue on this and wider associated issues.

Gandhi’s Essential Writings, published in 2008, was a new edition of an earlier collection of Gandhi’s writings. Much of the thinking behind the new selections was the need to show how broad Gandhi’s thinking was, and how very practical and even earthy issues were central to his work for swaraj. Part III, ‘Transforming societies’ and Part IV, ‘India under British rule: making a new nation’ gather evidence of his thinking and work on these matters.

It is time to return to Gandhi to gain a perspective on problems which are old and yet contemporary.

The Rev. Prof. Judith M. Brown was the Beit Professor of Commonwealth History at the University of Oxford from 1990-2011, when she retired from teaching. She is the editor of the Oxford World’s Classics edition of Gandhi’s Essential Writings.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Protests in Bangalore following the rape and murder of a young woman in Delhi, December 2012. Photo by Jim Ankan Deka. [CC-BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Why is Gandhi relevant to the problem of violence against Indian women? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesÉmile Zola and the integrity of representationEdmund Gosse: nonconformist?Why foreign policy must be more ideological than economic policy

Related StoriesÉmile Zola and the integrity of representationEdmund Gosse: nonconformist?Why foreign policy must be more ideological than economic policy

Why foreign policy must be more ideological than economic policy

To what extent should economic and foreign policies be guided by ideology? Are politicians who remain committed to particular policy prescriptions principled representatives? Are they opportunists who ride the popularity of simple, easily explained idea into office? Or are they Neanderthals incapable of adapting to new ideas or responding to changing conditions?

For economic policy, the answer depends on how we define ideology. The vast majority of economists agree on certain basic principles that both theory and empirical analysis support: that the market-based economic systems that characterize the industrialized world today perform far better than the Soviet-style command economies in existence prior to the fall of the Berlin Wall; that setting all personal income tax rates at 95% will choke off work effort and setting them at 5% will not generate enough tax revenue to allow the government to perform its core functions; that relatively free and unfettered trade will lead to a higher standard of living than erecting many barriers to trade. Adhering stubbornly to these rigorously tested principles can hardly be termed ideological intransigence.

Within these broad guidelines, however, there is considerable room for disagreement and debate. The economic models adopted by the United States, Germany, Japan, and the Scandinavian countries each have something to recommend them. And the data show that each has outperformed the others under different circumstances and at various points in history. We should not, therefore, condemn as ideologically narrow-minded those who consistently lean on one side of the debate.

It is also important to note that the criteria for selecting appropriate economic policies depends on the relative weights politicians and policymakers place on economic growth and distribution. Economics has a great deal to say about the consequences of various fiscal, monetary, trade, and regulatory policies and whether they promote or hinder economic growth, stability, low unemployment, and moderate inflation. These policies often also have important consequences for the distribution of wealth and income among the rich, the poor, the oilman, the farmer, and many other groups within society. Although economics is good at identifying these distributional effects, it has much less to say about whether making one sector of society better or worse off is good or bad, fair or unfair.

Ideology is damaging in the economic sphere when policymakers adopt one key idea as the centerpiece of their policy and cling to it under any and all circumstances, whether or not this approach is supported by evidence.

Consider how one country’s unflinching fidelity to an economic ideology led to a tragedy of massive proportions.

The Irish famine was one of the worst humanitarian disasters of the 19th century. It left roughly one million people—or about one ninth of Ireland’s population—dead in its wake and led an even larger number to emigrate.

The basic facts of the famine are well known. In the autumn of 1845, the fungus Phythophthora infestans reached Ireland and devastated the potato crop. The blight, as it is now known, had no name when it was first discovered, but was referred to as the disease, the blight, distemper, the rot, the murrain and, perhaps most fittingly, “the blackness,” because it rendered the afflicted potatoes an inedible black mass. The blight devastated the potato crop in several consecutive years and, because of the central place of potatoes in the Irish diet, led to mass starvation.

Britain’s prime minister at the time, the Conservative Sir Robert Peel, immediately took steps to alleviate the suffering in Ireland, sending experts to study the cause of the infestation, promising to provide free of charge any chemical that would combat the blight, and arranging — without Parliamentary authorization — a large shipment of corn from the United States. Most importantly, Peel undertook the politically dangerous task of repealing the long-standing tariff on imported grain, the Corn Laws, in order to lower the price of food faced by the Irish.

The repeal of the Corn Laws helped Ireland’s poor, but, because the tax on imported grain was popular with the Conservative Party landed artistocracy, cost Peel his job. Peel’s replacement as prime minister, the Liberal Lord John Russell came into office adamantly opposed to any measures that would interfere with the workings of the free market for grain. Commenting on Peel’s response to the famine, he wrote: “It must be thoroughly understood that we cannot feed the people. It was a cruel delusion to pretend to do so.” Russell’s commitment to completely free and unfettered markets proved tragic, leading to an even heavier death toll than the famine would have otherwise taken. In this case, economic policy guided solely by ideology had tragic results.

Does the same calculus apply to foreign policy? No.

The results of foreign policy are, by their very nature, less easily measured than those of economic policy and their goals far less well defined. For comparison’s sake, consider the mission statements of the US Treasury and the US Department of State. Treasury’s mission is to: “Maintain a strong economy and create economic and job opportunities by promoting conditions that enable economic growth and stability at home and abroad, strengthen national security by combating threats and protecting the integrity of the financial system, and manage the U.S. Government’s finances and resources.” The success of this mission can be evaluated by looking at current levels of GDP per capita (and its growth), unemployment, and inflation.

By contrast, indicators of an effective foreign policy are more nebulous. Does success mean opening more embassies? Concluding more international agreements? Presiding over fewer boots on the ground?

The State Department’s mission statement is: “Advance freedom for the benefit of the American people and the international community by helping to build and sustain a more democratic, secure, and prosperous world composed of well-governed states that respond to the needs of their people, reduce widespread poverty, and act responsibly within the international system.”

The goals of American foreign policy are both more difficult to measure and are inherently more ideological in nature than those of economic policy. During the Cold War, the United States sided with Great Britain, France, West Germany, and the western allies against the Soviet Union and its satellites. In addition to their commitment to democracy, our allies were more economically dynamic that the USSR. If our allies had been poor, and the Soviet Union rich, would we have abandoned our alliance with these democracies in favor of a wealthier totalitarian state?

Similarly, in the Middle East today we are far more closely allied with Israel—which, despite its imperfections, is an open, well-governed state that shares our democratic values—than with the numerous states with which it is still at war, which are, on the whole, neither open, nor democratic, nor particularly well-governed.

This brings us to Syria which, by anyone’s standards except Russia’s, is not acting responsibly within the international system and should be a pariah state. American isolationists argue that meddling in Syria is none of our business. Other opponents of US action argue that anything short of a major US intervention in Syria will do no good and so should not be attempted. These positions are hard to square with our ideological commitment to supporting well-governed states that respond to the needs of their people.

Historically, ideologically-based economic policies have been spectacularly unsuccessful. Britain’s unwavering commitment to free markets during the Irish famine — despite ample evidence that free markets were not working — was madness. Pledging to never vote for a tax increase — as almost all Republican members of the last Congress did — was similarly foolhardy.

As in economic policy, foreign policy makers must make judgments based on solid evidence and hard-headed analysis. However, because the goals of foreign policy are different than those of economic policy, there must be a greater role for ideology.

Richard S. Grossman is a professor of economics at Wesleyan University in Middletown, CT and a visiting scholar at the Institute for Quantitative Social Science, Harvard University. His book Wrong: Nine Economic Policy Disasters and What We Can Learn from Them will be published in November by Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: A king on a chess board. © RBFried via iStockphoto.

The post Why foreign policy must be more ideological than economic policy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe trouble with LiborFeral politics: Searching for meaning in the 21st centuryThe price of free speech

Related StoriesThe trouble with LiborFeral politics: Searching for meaning in the 21st centuryThe price of free speech

Feral politics: Searching for meaning in the 21st century

Could it be that conventional party politics has simply become too tame to stir the interests of most citizens? With increasing political disaffection, particularly amongst the young, could George Monbiot’s arguments about re-wilding nature and the countryside offer a new perspective on how to reconnect disaffected democrats? In short, do we actually need feral politics?

Feral: ‘In a wild state, especially after escape from captivity or domestication’

My wife and I like to play a game. She insists I am not allowed to read ‘work’ books about politics during weekends or holidays; I respond by searching out the best political writing that happens not to have an obviously political title. The benefit of this little game of domestic power politics is that I am frequently forced to read books that would of otherwise have ever made it to the top of my ‘must read’ pile. One such example is George Monbiot’s Feral: Searching for Enchantment on the Frontiers of Rewilding which I devoured last week and like all good books it left my mind buzzing not just in relation to the specific focus and arguments of the book but also in relation to its broader relevance.

When stripped down to its basic components Feral is a treatise about re-engaging with nature and rediscovering our landscape by restoring and rewilding our ecosystem. This process might range from changing farming and fishing methods away from a hegemonic monoculture through to reintroducing certain animals such as wild boar, lynx, and wolves to certain parts of Western Europe. Unlike the bleak pessimism of a great deal of environmental writing Monbiot charts away out of ecological decline by allowing nature to return to a wilder less predictable form. This new positive environmentalism offers a way to re-conceptualize the world around us — to redefine the art of living — in relation to the physical landscape. But it also offered much more. The problem was that for at least a week I couldn’t quite put my finger on what exactly this ‘more’ element was or why it mattered. And then the party political conference season opened in the United Kingdom and everything became clear.

George Monbiot, author of Feral Politics

In essence, George Monbiot’s book is not about boar and bears but about the art of living in the twenty-first century. It is about how we live our lives, how we define what matters and whether, deep down, we are satisfied by a world based around ever-increasing consumption. The simple fact would seem to suggest that we are not satisfied. The World Health Organization rates clinical depression as one of the main health challenges for the twenty-first century, while in the United Kingdom the most common cause of death amongst young men is suicide. To rewild or turn feral is not therefore just about reconnecting with the landscape but it is also about reconnecting with yourself.

‘We still possess the fear, the courage, the aggression, which evolved to see us through our quests and crises, and we still feel the need to exercise them. But our sublimated lives oblige us to invent challenges to replace the horrors of which we have been deprived,’ Monbiot argues. ‘We find ourselves hedged by the consequences of our nature, living meekly for fear of provoking or damaging others.’ Such arguments resonate with Sigmund Freud’s arguments in Civilization and its Discontents (1930) that ‘civilization’ (Western modern civilization) was a trade-off in which one cherished value (individual freedom) is exchanged for another (a degree of security). The tension between a deep need for instinctual freedom — wildness, adventure, risk, those qualities that make life worth living — and the conformity demanded by society was the root, according to Freud, of widespread social discontent. Émile Durkheim‘s classic 1897 work on social anomie and suicide came to not dissimilar conclusions about the evolution of modern life. And yet the contemporary relevance of this seam of scholarship only became clear when watching the party conferences. Has there ever been a more depressing display of the death of politics in the sense of a failure to promote fresh ideas, to inspire belief or hope, to offer new choices or dare to stand out from the pack? Is it any wonder that recent surveys suggest that only twelve per cent of 18-25 year olds are currently planning to vote in the 2015 General Election? To them politics simply doesn’t matter, and if the party political conferences are anything to go by its easy to see why they think this.

My argument is not, of course, that politics does not matter — it matters far more than most disaffected democrats seem to realize — but at the same time it would be naive to deny the existence of a serious disconnection between the governors and the governed. Might an argument about rewilding not therefore apply to the political realm? Could there be an as yet unmet need for a slightly wilder political life — a desire for a fiercer, less predictable and more variated political ecosystem? Just as both the land and sea suffers from a hegemonic monoculture — captured perfectly in the term ‘sheep wrecked’ — so politics seems trapped within a similarly narrow hegemonic ideological framework where the parties offer variants of the same pro-market model. Can anyone show me the creative rebels or the big ideas or the politicians who are simply willing to tell the public that there are no simple solutions to complex problems?

The danger of using the metaphor of ‘re-wilding’ or encouraging the evolution of feral politics without some accepted boundaries is that it risks unleashing a range of social forces that once freed cannot so easily be controlled or channeled. Put slightly differently, there are many parts of the word where politics seems far wilder but I doubt whether those countries or regions offer great inspiration for those seeking a more contented or meaningful life. If they did why would hundreds of thousands of refugees risk their lives attempting to seek out a new life in Western Europe, North America, or Australasia? Could it be that the notion of feral politics risks throwing away centuries of social progress and that democratic politics is by its nature slow, incremental… domesticated (i.e. Max Weber‘s ‘slow boring of hard wood’)?

I’m not convinced. Political choices are rarely black or white and my sense is that the public have an appetite for ‘big ideas’ that dare to question the robotic and instrumental nature of modern life. George Monbiot’s book provides a glimpse of what some of these ideas might be.

Professor Matthew Flinders is Director of the Sir Bernard Crick Centre for the Public Understanding of Politics at the University of Sheffield. He wrote this blog while travelling to ‘The Civic Culture – Revisited’ conference that was organized by the University of Kent and hosted by the London school of Economics and Political Science on the 26 September 2013. The research and data presented at the event tended to chart a rising tide of political skepticism amongst the public. Author of Defending Politics (2012), you can find Matthew Flinders on Twitter @PoliticalSpike and read more of Matthew Flinders’s blog posts here.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: George Monbiot [CC-BY-SA 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Feral politics: Searching for meaning in the 21st century appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe price of free speechWill young invincibles buy into the ACA?Criticisms of Obamacare

Related StoriesThe price of free speechWill young invincibles buy into the ACA?Criticisms of Obamacare

October 1, 2013

The first ray gun

When reporting on the origin of that science fiction cliché, the ray gun or death ray, most histories cite H.G. Wells’ classic story The War of the Worlds, which first appeared in Pearson’s Magazine between April and December of 1897. Wells was undoubtedly one of the founders of science fiction, striving to create original situations and ideas. The Martian Heat Ray, like the use of gas warfare, is completely unlike Western weapons of the day, and marks the Martian culture as a truly different and alien one.

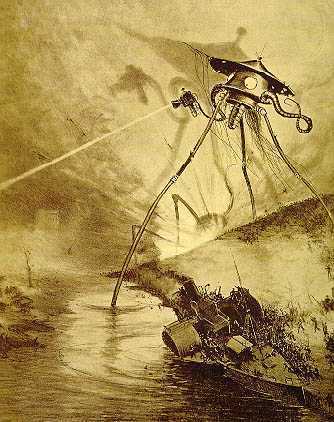

Alien tripod illustration by Alvim Corréa, from the 1906 French edition of H.G. Wells’ “War of the Worlds”. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

But Wells was not the first to write about alien invaders from another world, armed with superior technology — including heat rays — with which they invaded an unsuspecting earth and conquered it as Europeans had conquered the Americas and elsewhere. The story had been told almost a century earlier. The story of how it first appeared takes us back to the newspapers of the beginning of the nineteenth century.

On 26 October 1809, the following advertisement appeared in The New York Evening Post:

Distressing

Left his lodgings, some time since, and has not since been heard of, a small elderly

gentleman, dressed in an old black coat and cocked hat, by the name of

Knickerbocker. As there are some reasons for believing he is not entirely in his right

mind, and as great anxiety is entertained about him, any information concerning

him left either at the Columbian Hotel, Mulberry Street, or at the office of this

paper, will be thankfully received.

P.S. Printers of newspapers would be aiding the cause of humanity in giving an

insertion to the above.

This was followed a week later by a letter in the same newspaper:

To the Editor of The Evening Post

Sir – Having read in your paper of the 26th October last, a paragraph respecting an old gentleman by the name of Knickerbocker, who was missing from his lodgings; if it would be any relief to his friends, or furnish them with any clue to discover where he is, you may inform them that a person answering the description given, was seen by the passengers of the Albany stage, early in the morning, about four or five weeks since, resting himself by the side of the road, a little above King’s Bridge. He had in his hand a small bundle, tied in a red bandana handkerchief; He appeared to be travelling northward, and was very much fatigued and exhausted.

A Traveller

This was answered on 16 November by another letter:

To the Editor of The Evening Post

Sir – You have been good enough to publish in your paper a paragraph about Mr. Diedrich Knickerbocker, who was missing so strangely some time since. Nothing satisfactory has been heard of the old gentleman since; but a very curious kind of a written book has since been found in his room, in his own handwriting. Now I wish you to notice him, if he is still alive, that if he does not return and pay off his bill for boarding and lodging, I shall have to dispose of his book to satisfy me for the same.

– I am, sir, Your Humble Servant

Seth Handaside

Landlord of the Independent

Columbian Hotel

Mulberry Street

On 6 December 1809, the following advertisement appeared in The American Citizen:

A History of New York

from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty

This work was found in the Chamber of

Mr. Diedrich Knickerbocker,

The old gentleman whose sudden and mysterious disappearance has been noticed.

It is published in order to discharge certain

Debts he has left behind.

The full title of the work, which is rarely given, suggests that this is not a serious work. “From the Beginning of the World…” is expected, but that final “…to the End of the Dutch Dynasty” suggests that the author, with the ultra-Dutch name of “Diedrich Knickerbocker,” thinks the end of Dutch rule in New York is comparable to The End of the World.

In fact, no such person as Diedrich Knickerbocker ever existed. The name was affixed to the satirical history of New York by its real author, and the series of advertisements were done to drum up excitement and interest — what we would today call a viral marketing campaign. (In light of which, the postscript to the first entry was a sly way of getting other newspapers to spread the story for free.)

Portrait of Washington Irving by John Wesley Jarvis, 1809. Historic Hudson Valley. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The real author of the book was a 26-year-old writer, satirist, editor, and lawyer named Washington Irving, today better known for The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and Rip van Winkle. As in his prior writings, he used this nominal history to poke fun at his fellow New Yorkers. In the opening portion, he took issue with European and American attitudes toward Native Americans and their treatment by the American settlers. How, he asked, would his compatriots feel if the inhabitants of the Moon were to similarly conquer them?

To return, then, to my supposition—let us suppose that the aerial visitants I have mentioned, possessed of vastly superior knowledge to ourselves—that is to say, possessed of superior knowledge in the art of extermination—riding on hippogriffs—defended with impenetrable armor—armed with concentrated sunbeams, and provided with vast engines, to hurl enormous moonstones; in short, let us suppose them, if our vanity will permit the supposition, as superior to us in knowledge, and consequently in power, as the Europeans were to the Indians when they first discovered them.

“Armed with concentrated sunbeams.” What could have inspired that thought of non-traditional, non-Western weaponry almost a century before Wells? Eight years previously William Herschel (discoverer of the planet Uranus) had observed that the mercury in a thermometer rose when placed in the portion of a spectrum beyond the observed red rays. This indicated the presence of a new and invisible form of light which he called Calorific Rays, and which we today call infrared light. A year later Johann Wilhelm Ritter looked for similarly invisible light at the opposite end of the spectrum and discovered invisible rays that could turn silver chloride-treated paper black. Today his Chemical Rays are called ultraviolet light.

But there was a more direct inspiration than these discoveries of previously unknown forms of light. In 1807 François Peyrard, Professor of Mathematics and Astronomy at the Lycée Bonaparte, had published his translation of the works of Archimedes with his own commentaries and experimental results. One of the more striking events in the book was the description of Archimedes’ supposed schemes for the defense of Syracuse against the Roman fleet about 212 BCE. The most memorable of these was the creation of an enormous concave mirror, made up of smaller individual mirrors arranged on a frame. With this, Archimedes was said to be able to set fire to ships in the Roman fleet from a distance. Peyrard performed his own experiments with mirrors and believed the scheme could work. Irving had traveled in Europe between 1804 and 1806, and might have heard of Peyrard’s work. Certainly such destruction without mechanical agent and from a great distance would meet his requirement of superior and different technology. No one seems to have followed up on this suggestion of ray weapons for a long time.

In the decades prior to Wells’ book, there had been much work on electrical discharges, which produced exotic new “rays.” Cathode Rays (electrons), Canal Rays (protons), and X-rays (even shorter wavelengths than ultraviolet) had been discovered before The War of the Worlds was written. Radioactivity, made up of the later-named alpha rays, beta rays, and gamma rays, was to follow, so the idea of new forces was in the air. Nonetheless, when Wells finally came to describe the origin of the Martian Heat Ray, it was suggested to be a highly collimated beam of infrared radiation.

Unknown to Wells at the time, and without his permission, his work was being serialized in the United States in the Boston and New York newspapers. After the run was completed, the editor of the Boston Post demanded a sequel. Moreover, he wanted one where, unlike in Wells’ original story, the people of Earth were able to effectively fight back and eventually win. Garrett P. Serviss responded with Edison’s Conquest of Mars, which ran from February to 13 March in 1898. In it, not only do Earth engineers invent rockets to bring the fight to Mars, but Thomas Edison (only 51 then and still very active in business) appears as a character in the story and invents a new beam weapon to counter the Martian heat ray — the Disintegrator. Until then, the term “Disintegrator” had been used for a type of mill, but now it was applied to a device that generated electrical vibrations that caused matter to selectively decompose.

In later years, many other authors were to appropriate the name “Disintegrator” along with the method of effectively dissolving matter, most notably Philip F. Nowlan and his character Buck Rogers. And with that, ray guns were off and running in popular fiction.

Stephen Wilk is a contributing editor for the Optical Society of America and the author of How the Ray Gun Got Its Zap: Odd Excursions into Optics and Medusa: Solving the Mystery of the Gorgon. He holds a Ph.D. in Physics and has worked on Laser Propulsion and High Energy Lasers at Textron and MIT’s Lincoln Labs, and has designed and built optical apparatus at Optikos Corporation, Cognex, and AOtec. He was previously a visiting professor at Tufts and a visiting scientist at MIT.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The first ray gun appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSix methods of detection in Sherlock HolmesSagan and the modern scientist-prophetsFive things you may not know about Jimmy Carter

Related StoriesSix methods of detection in Sherlock HolmesSagan and the modern scientist-prophetsFive things you may not know about Jimmy Carter

Sagan and the modern scientist-prophets

Nobody questions Carl Sagan’s charisma. He was television’s first science rock star. He made appearances on the Tonight Show; he drove a Porsche with a vanity plate that read “PHOBOS,” one of Mars’s moons; journalists enthused over his “velour” voice. Over 700 million people have viewed Sagan’s groundbreaking public-television series, Cosmos, and about one in three Amazon commenters on the DVD set indicates that the show inspired him/her to pursue science.

Obviously, there has to be a lot more to Sagan’s success than just his personal magnetism. Yet until recently, even hard-nosed scholars have not seemed to be able to get past it. If we can better understand the cultural structures that enabled Sagan’s meteoric rise to fame—not just his, but also the trajectories of science stars such as Stephen Hawking, Sam Harris, and Neil deGrasse Tyson—we can better understand the enormous authority science wields in public life. To begin, I would argue Sagan benefited from a sort of bully pulpit that was cemented into place by 3,000 years of civic practice in the West. That bully pulpit, ironically, used to belong to the prophet.

I say “ironically” because Sagan was an avowed agnostic, although it would be hard to find an agnostic who talked more openly, often, and positively to the public about god and spirituality. Sagan claimed in Demon-Haunted World, “Science is not only compatible with spirituality; it is a profound source of spirituality” (p. 29). This argument echoed throughout the narrative of Cosmos, which Sagan navigated in his chapel-like “Ship of the Imagination,” complete with a glowing altar and a hymnal by Vangelis.

But Sagan’s public rhetoric was more than vaguely religious; it was specifically prophetic. Sagan boasted in Demon-Haunted World, “Not every branch of science can foretell the future—paleontology can’t—but many can and with stunning accuracy. If you want to know when the next eclipse of the Sun will be, you might try magicians or mystics, but you’ll do much better with scientists” (p. 30). The final episode of Cosmos opens with Sagan reading from the book of Deuteronomy: “I have set before you life and death, blessing and cursing: therefore choose life, that both thou and thy seed may live…” (30:15). In Sagan’s bible, death was nuclear winter, a cause he pushed on- and off-screen with the zeal of Jeremiah.

Carl Sagan with a model of the Viking lander. NASA. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

While Sagan was the first public scientist to leverage television as his bully pulpit, he did not invent the stance of the scientist-prophet. That honor goes to the founders of the Royal Society in the mid-seventeenth century. Robert Boyle and his colleagues hybridized Protestant prophecy and natural magic (a forerunner of our sciences) to make “experimental philosophy”—and to establish it as England’s new civic oracle, its certainty factory. In the end, what a prophet does isn’t to tell the future; a prophet engages the public in an evaluative dialogue that manufactures certainty out of crisis. When the gears of our democracies grind to an impasse, our prophets step forth from the wilderness and remind us who we are, what we really value. With our dilemma cast in this new light, we can at last move off its horns and into civic action.

This was what Jeremiah did for the nation of Judah; this was what the Delphic oracle did for Athens as it faced down Xerxes. But after the precedent set by the Royal Society—who confirmed their prophetic calling with resurrected birds, glowing phosphorus, and other signs and wonders never before seen on the face of this earth—scientists became the new prophets of democracy. In this way, Charles Darwin helped Victorian England build and justify its new industrial society; and Louis Agassis bolstered American manifest destiny. In the twentieth century, Albert Einstein and J. Robert Oppenheimer helped usher in the nuclear age. Then Rachel Carson helped mothers and physicians push it back for a slim chance at returning to a bucolic, pre-industrial America.

So when Carl Sagan strode out onto the California seashore in the first episode of Cosmos, the stage was set for him in more ways than one. His viewers, disciplined by generations of cultural practice, immediately recognized Sagan’s prophetic stance. Along with the objective cosmological research he presented, they listened to his admonitions about mutually assured destruction and nuclear winter as if these were totally normal things for a scientist to say—which in fact they are not: a considerable body of research has found that scientists strongly discourage each other from making moral pronouncements in technical settings. Whether Sagan precipitated or followed public will against nuclear stockpiling is impossible to say, but he was certainly in the flow of his times. By the time Sagan recorded his new preface to Cosmos in 1991, he was able to announce that widespread fear of nuclear holocaust was a thing of the past.

Since Sagan’s groundbreaking television performance, the media venues for scientist-prophets have proliferated; so have the number of celebrity and public scientists. Stephen Hawking, Stephen Jay Gould, Neil deGrasse Tyson, Sam Harris, Stephen Schneider, Richard Dawkins, Olivia Judson, James Hansen, and other scientists regularly get up in their bully pulpits to tell us not just what they’ve learned but also how they think we should live as a result. Whether we think this is a good thing or not is up to our personal politics. The fact remains that as long as our public crises turn on technological, medical, or environmental issues (as nearly all of them do), we will turn to science for answers; and as long as science is our dominant channel to civic truth, scientists will remain our prophets.

Lynda Walsh is an Associate Professor of English at the University of Nevada, Reno. She specializes in the rhetoric of science and reception theory. Her new book Scientists as Prophets: A Rhetorical Genealogy traces the historical evolution of the science adviser’s cultural authority in public life.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Sagan and the modern scientist-prophets appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFive things you may not know about Jimmy CarterThe price of free speechYggdrasil and northern Christian art

Related StoriesFive things you may not know about Jimmy CarterThe price of free speechYggdrasil and northern Christian art

Five things you may not know about Jimmy Carter

Most people think of Jimmy Carter, if they ever do, as a failed president and perhaps overly energetic former president. Yet a closer look at his four years in office suggest there was more to his presidency than his forging a Middle East peace initiative and his landslide loss in his reelection campaign based on rising inflation, the popularity of his opponent Ronald Reagan, and inept managing of the Iran hostage crisis. Indeed, here are five things you may not about Carter’s presidency.

First, he was actually able to get Congress to approve most of his ambitious legislative agenda. Though Carter had tense relationships with the Democratic majority in Congress throughout most of his presidency, Carter signed several landmark pieces of legislation into law in environmental regulation and government ethics.

Second, Carter diversified the federal judiciary to an unprecedented degree. He appointed more women and minorities to federal judgeships than any previous president. Indeed, his judicial nominees became a model for those of later Democratic presidents, including Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. Clinton’s two Supreme Court appointees — Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer — had previously been federal courts of appeal judges appointed by President Carter.

Third, Jimmy Carter was the first person from the deep South elected President of the United States. Indeed, his support in Southern States had been instrumental to his election in 1976, and the loss of that support was devastating to his reelection bid.

Fourth, Jimmy Carter was the first Evangelical elected President of the United States. Indeed, Carter’s open religiosity, including his teaching Sunday school and acknowledging his religious faith as the basis for many of his political (and international) initiatives, became a model for subsequent presidents, who have all openly discussed the importance of their religious faiths in their lives.

Last but not least, Carter’s leadership in civil rights still resonates in American politics, particularly among Democratic presidents. He was the first president to champion women’s rights and affirmative action, which both Presidents Clinton and Obama have supported as well.

Nor is this all there was to Carter’s presidency. Both his successes and failures in office are important to understand in order to appreciate the extent of even an unpopular president’s powers in office.

Michael Gerhardt is Samuel Ashe Distinguished Professor of Constitutional Law at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. A nationally recognized authority on constitutional conflicts, he has testified in several Supreme Court confirmation hearings, and has published five books, including The Forgotten Presidents and The Power of Precedent. Read his previous blog posts on the American presidents.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Official Presidential portrait of James Earl “Jimmy” Carter by Herbert E. Abrams. White House. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Five things you may not know about Jimmy Carter appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe price of free speechCheers to the local barA cool president: what you might not know about Calvin Coolidge

Related StoriesThe price of free speechCheers to the local barA cool president: what you might not know about Calvin Coolidge

The price of free speech

It is ironic: Free speech is seldom free. It often demands a price. There is a comic adage that says, “tell your boss what you think of him and the truth will set you free.” Indeed. Too often, such is the cost of free speech.

The Newseum’s five freedoms guaranteed by the First Amendment of the US Constitution: Freedom of Religion, Freedom of Speech, Freedom of the Press, Freedom of Assembly Peaceably, Freedom to Petition the Government for Grievances at the opening, April 11 2008. Photo by David (dbking). CC 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The aspirational goal of the First Amendment is to reduce the punitive costs of exercising free speech rights for everyone from irksome anarchists to self-righteous anti-abortionists to confrontational environmentalists to vexing Tea Party types to those who trade in taboo. Faithfully applied, the First Amendment should allow all Americans — including people of color and people of conscience — to voice their own life gospel regardless of how offensive it might be to the rest of us, the respectful many.

Toleration is the stock of the First Amendment. It holds in reserve the patience needed to prevent the punitive costs typically associated with breaching societal norms by contesting them or even mocking them. If the First Amendment did not protect offensive expression, why would we need it? After all, there is no reason to protect speech with which we agree or ideas which we accept or values which we cherish. The whole idea of the great Madisonian experiment is stay the government hand when it would be oppressive, when it would censor those whose messages we abhor.

Lenny Bruce, the vulgar satirist, died for our First Amendment sins in convicting him for words crimes. Lawrence Ferlinghetti, the publisher of City Lights Books and founder of City Lights Bookstore, fought censors to defend a poem (Howl). The costs of such abridgements are far too high for any society committed to First Amendment ideas. They are part of a past that reminds us of our censorial blunders.

To be American is to celebrate, not denigrate, dissent. Sure, we may disagree. True, we might take strong exception. What to do? The remedy is to respond in kind: add more speech (your speech) to the mix. You cannot stand those folks who demonstrate at military funerals? Okay. So why not demonstrate around them? That is, form a protective circle around our fallen military men and women and thereby do your part to diminish the hateful message of those who feel that is their God-given duty to disseminate hate. To celebrate the idea and practice of dissent does not mean that one must yield to bigotry or homophobia or mean-spiritedness. It just means that we tolerate them. Consider, for example, two forms of dissident expression I have witnessed recently:

A man stands outside of the Vatican Embassy in Washington, D.C. He is a regular at his protest post on the sidewalk where he holds huge signs that say things like “The Vatican Aids Pedophiles.” Is it true? Is it fair? I don’t know, though I have a view on the matter. What I do know is that this sign of dissent is a good sign in America. I celebrate it!

Abortion protestors stand on an island in the street holding graphic posters with gruesome images of disembodied fetuses. I turn my head. Do I share their views? No! But I confess to taking some strange comfort in the fact that their public spectacle is tolerated, no matter how much it causes commotion in my circle of comfort.

Today Muslims and government whistleblowers sometimes bear the brunt of intolerance. Some don’t like their mosques in our neighborhoods, while others have no patience for those who release government secrets about government wrong-doing. They irk us; they contest our life creed; and they are said to place our safety at risk. Stop them, slap them, wiretap them, imprison them, drive them out of our society or into our prisons. The outsider, the non-conformist, the agitator — they’re all insufferable to many of us at some time or even most of the time.

Censors, of course, have a variety of devious ways for dealing with insufferable types. Take, for example, “free speech zones” — an Orwellian turn of phrase if ever there was one. Such zones (like the ones at the 2004 Democratic National Convention) are an anathema to the liberty ideal embodied in the First Amendment. And yet, our society permits them on campuses and elsewhere with the hope that dissident messages can be foiled by fences or ruled by regulations.

In the end, know this: the speech we defend is the liberty we preserve. Yes, the costs of freedom are always great, no matter what the era or society. Then again, to be unwilling to pay such a price is to be unfit for that kind of government worthy of a free people.

Ronald Collins is the Harold S. Shefelman scholar at the University of Washington School of Law. He is the co-author with Sam Chaltain of We Must not be Afraid to be Free (2011), and On Dissent (2013), with David Skover. His next work, also with Skover, is an e-book titled When Money Speaks: Campaign Finance Laws, the McCutcheon Case & the First Amendment, due out next spring.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The price of free speech appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe amended ConstitutionCheers to the local barJudging a book by its cover: recordings, street art, and John Coltrane

Related StoriesThe amended ConstitutionCheers to the local barJudging a book by its cover: recordings, street art, and John Coltrane

Judging a book by its cover: recordings, street art, and John Coltrane

Created by the Berlin-based street artist MTO, a graffiti artwork was painted on a Parisian wall a few years ago and only on display for a few days before being painted over. A few photographs of the image, taken by MTO at the scene, are all that remain of the work. MTO’s image served as a perfect visual manifestation of the issues and strategies at play in my research: a graffiti version of an iconic photograph of John Coltrane which appears on the front of his 1964 album, A Love Supreme.

MTO, John Coltrane, 2009. Courtesy of the author.

The influence of recordings is more than just musical or sonic in nature; recordings impact different arts and appear in different cultural contexts. In many ways, they have the potential to alter our view of the places we live in and, in some instances, can change our relationship to history itself. The temporary nature of MTO’s artwork and its subsequent use in photographic form and on the web also mirrors the changes that occur when music is recorded, disseminated, and used in different ways. Just as the recordings themselves can be understood in a number of different ways, these layers of mediation — that is, the channels through which we communicate, or the involvement of third parties in the construction and distribution of meaning — enable A Love Supreme (and other recordings) to take on infinite new lives and meanings.

MTO’s image is inspired by Coltrane but also acts as an alternative to everyday representations of the icon. This is not an official reading of Coltrane’s masterpiece and, arguably, it conveys a certain politics: the graffiti artwork itself can be read as an act of subversion. Similarly, some of my research interests involve challenging official or dominant narratives that have become associated with Coltrane, trying to seek out underlying agendas which might play a role in the changing representation and interpretations of his music, and offering an alternative means of understanding the Coltrane legacy.

Album cover of John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, 1964. Courtesy of the author.

Coltrane’s seminal recording and MTO’s image exist among several other voices. A Love Supreme interweaves with, and stands out against, a crowded backdrop of other art (whether it is recorded sound or street art). The image encourages us to make links between the past and the present and also encourages us to think about the relationship between recordings and the materiality of everyday life.

MTO painted a collection of other music-inspired street scenes in different settings, including portraits of Jimi Hendrix and Thelonious Monk. Yet the artists and his graffiti remain elusive. There are several untold stories such as how the work was created and who exactly MTO is beyond his pseudonym. (The artist has remained anonymous throughout our correspondence.) MTO is most often received as a mediated figure, but his presence speaks to many people in different communities in deeply personal ways.

Finally, MTO’s image suggests a type of interdisciplinarity that is rooted in everyday life. It is not high art made for the gallery but a music-inspired creation that interacts with, and helps to shape, its environment. We are not instructed as to how to interpret this image, yet an awareness of Coltrane will play a part in our reading of it. This feeds directly into the way in which jazz is an interdisciplinary, cross-cultural, and transnational form. Arguably, images (whether they be on album covers or street walls), as well as written texts, poems, films, anecdotes, and broader cultural mythologies, have as much a role to play in the construction and framing of jazz as the sounds we hear on record.

Throughout my study of Coltrane’s seminal album and a selection of his subsequent recordings, I wanted to convey a picture of the complexity of the Coltrane legacy and the politics of interpreting and understanding what Coltrane’s music means to people today. In many respects, I also wanted to highlight several paradoxes that are at play in the representation of Coltrane, between the increasingly controlled and restricted interpretations of Coltrane and his music on the one hand, and the widespread and multifaceted nature of Coltrane’s cultural influence on the other. MTO’s image served as a perfect visual manifestation of the issues and strategies at play. For me, MTO’s image, scenario, and the ideas that flow from it embody several of the key themes that run through my work. The saying goes that you should never judge a book by its cover. However, in the case of my Beyond A Love Supreme: John Coltrane and the Legacy of an Album, I would be happy for such a judgement to be made.

Tony Whyton is Professor of Jazz and Musical Cultures at the University of Salford and the author of Beyond A Love Supreme: John Coltrane and the Legacy of an Album and Jazz Icons: Heroes, Myths, and the Jazz Tradition. He is the founding editor of the international journal The Source: Challenging Jazz Criticism and co-editor of the Jazz Research Journal.

The Oxford African American Studies Center combines the authority of carefully edited reference works with sophisticated technology to create the most comprehensive collection of scholarship available online to focus on the lives and events which have shaped African American and African history and culture.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Judging a book by its cover: recordings, street art, and John Coltrane appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBreaking Bad’s Faustian CastTen surprising facts about the violinFrancesca Caccini, the composer

Related StoriesBreaking Bad’s Faustian CastTen surprising facts about the violinFrancesca Caccini, the composer

September 30, 2013

Yggdrasil and northern Christian art

A lot of things become clear when you realize that many of the puzzling and mysterious Christian artifacts and poetry of the North, those from England and Germany as well as those from the Scandinavian countries, are speaking in the language of Germanic myth—specifically in the language of the ancient evergreen tree, the savior of the last human beings, Yggdrasil. Below is a look at the curiously designed stave churches of Norway and the round churches of Denmark, all with connections to Yggdrasil, the heart and soul of much of northern Christian art.

A view of the Borgund church from the west southwest, showing the tiers of roofs as they decrease in size as the eye goes upward, suggesting the shape of a pine or spruce tree. The bell tower rides saddleback on the third roof and has sides that are carved with openwork to let the bells’s sound pass. The next two roofs constructed above the bell tower seem to have no structural function except that of giving to the building the shape and profile of an evergreen tree. Image courtesy of G. Ronald Murphy, S.J. All rights reserved.

Detail from the baldachin of the church at Ål. Christ carrying his cross. The exaggerated length of the stumps of sawn off branches serves to show the cross to be a tree. The artist even painted the stumps of the branches red to make them more obvious and perhaps also to bring the tree’s weeping from its wounds into association with the wounding and suffering of Chris. As in the Dream of the Rood, the painting associates Yggdrasil with the cross. From the Oldsaksammling of the University Museum in Oslo. Image courtesy of G. Ronald Murphy, S.J. All rights reserved.

The central pillar supporting the roof structure of the Uvdal Stave Church. The ceiling above it is an early modern modification which may contribute to better heat retention, but which prevents any sight of the branching of the rafters away from the “tree trunk.” The early-modern artist who decorated the church may have been aware of the Yggdrasil tradition, for he painted an enveloping and luxuriant spread of leaves and vines on the ceiling and walls of the church. The central wooden stave or tree trunk structure used in Norway was paralleled by the central stone pillar design of the round churches on Bornholm in Denmark. Image courtesy of G. Ronald Murphy, S.J. All rights reserved.

The baptismal font in the Aakirke on Bornholm. Above the three kings bring their gifts to the baby Jesus seated on his mother’s lap. Below, the vines and intertangled life forms of Yggdrasil. The cloth left on the top left of the font is from a baptism that had just been done. Image courtesy of G. Ronald Murphy, S.J. All rights reserved.

Olskirke, upper storey. The radially placed rafters suggest a tree-like building on the inside, as does the cone-shaped roof they support when viewed from the outside. Image courtesy of G. Ronald Murphy, S.J. All rights reserved.

More than any other, Olskirke’s central pillar with its overhanging circular vaulting, all painted in vines, stars, constellations, even with evergreen pine (spruce) cones, gives the observer the feeling of standing under the protection of the Yggdrasil as the World Tree. Image courtesy of G. Ronald Murphy, S.J. All rights reserved.

G. Ronald Murphy is Professor of German at Georgetown University and author of The Owl, The Raven, and the Dove: The Religious Meaning of the Grimms’ Magic Fairy Tales, Gemstone of Paradise: The Holy Grail in Wolfram’s Parzival, and Tree of Salvation: Yggdrasil and the Cross in the North.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Yggdrasil and northern Christian art appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHealing the divide between Christianity and the occultThe Holy CrossCheers to the local bar

Related StoriesHealing the divide between Christianity and the occultThe Holy CrossCheers to the local bar

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers