Oxford University Press's Blog, page 892

October 18, 2013

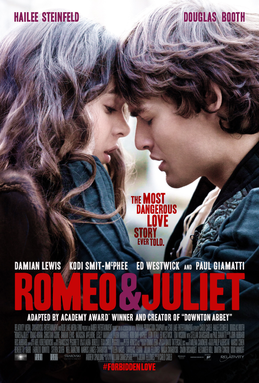

Romeo & Juliet: the film adaptations

By Jill L. Levenson

In its fall preview issue for 2013 (dated 2-9 September), New York magazine lists Romeo and Juliet with other films opening on 11 October 2013, and it comments: “Julian Fellowes (the beloved creator of Downton Abbey) tries to de-Luhrmann-ize this classic.” The statement makes two notable points.

First, it connects the new film primarily with its screenwriter, known to potential audiences from his successful and recent work on television, as well as his screenplay for Gosford Park. Although it mentions in passing only the two lead actors, members of the cast are also familiar from more or less star turns on television and film in the United Kingdom and the United States. For instance, , who plays Juliet, performed the role of Mattie Ross in the Coen brothers’ True Grit; and , who appears as Romeo, was Boy George in the BBC Two dramatic film Worried About the Boy. The new Romeo and Juliet assigns a few secondary roles to seasoned actors: , known for a series of accomplished films (such as Sideways), plays Friar Laurence; , having collaborated often on films with Mike Leigh, plays the Nurse. enjoys the most celebrity. At the moment he brings to the relatively small role of Lord Capulet his background as Marine Sergeant Nicholas Brody on the highly-rated American television series Homeland.

Second, the New York statement connects this twenty-first-century version of Romeo and Juliet with the last important film of the tragedy in the twentieth century, Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet (released in 1996); it suggests that Fellowes’s adaptation subverts Luhrmann’s. Further, reviews of the new film link it with the other influential cinematic version during the second half of the twentieth century, Franco Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet (released in 1968). They find visual parallels in the settings and costumes, and in the youth of the actors performing the lead roles. Possibly Abel Korzeniowski’s score here and there recalls the romantic background music that Nino Rota created for Zeffirelli’s film. In short, contemporary reviewers and commentators compare Fellowes’s film with the two cinematic adaptations that capped the last century. Both adaptations were original and widely known.

Aware of theatrical and cinematic precedents, Zeffirelli absorbed key events and characters from the play, with only one-third of the dialogue, into a new composition. He deliberately contextualized the narrative in the anxieties of the late 1960s, reflecting on issues from sexual identity and generational conflict to Vietnam, omitting passages which interfered with the impression of contemporaneity. In his film version there are few traces of lyricism. He distinguishes the protagonists from other characters by allowing them to speak less – and less articulately – than the others, even while they look beautiful and very young. Played by the teenage and , they had turned into victims of the twentieth-century zeitgeist. Zeffirelli’s vision produced the most popular and lucrative rendition of the tragedy for a period of almost thirty years.

Luhrmann’s version also reflects its era, perhaps more specifically, in its postmodern style: it echoes key figures in cinematic history, from Busby Berkeley to Federico Fellini to Ken Russell; it uses techniques and images familiar from television networks and genres. Like Zeffirelli’s, this film adapts the plot, characters, and about one-third of the dialogue to a medium which allows the play a radically new ambience. It projects sympathetic lovers, the young and , in an urban setting of anarchic gang violence and disintegrating social structures, a political tableau. With his reworking of Romeo and Juliet, Luhrmann spoke clearly to the very late twentieth century: North American teenagers rushed to see the film more than once, and adults gave it a positive, sometimes enthusiastic response.

Despite the claim in New York, Fellowes’s film adaptation barely refers to these precedents, nor does he use much of Shakespeare’s text. “Seventy-five per cent of the film is Shakespeare,” he claims in an interview. “We’ve tightened the narrative, we’ve made certain things clearer that were difficult to understand, but the great speeches are all still in” (quoted in The Globe and Mail, 11 October 2013, R3). Although statistics are difficult to confirm on the basis of viewing the film rather than analyzing its screenplay, it seems apparent that Shakespeare’s dialogue has been cut by well more than twenty-five per cent. Fellowes either omits Shakespeare’s words completely or he substitutes others which make the diction more colloquial and the literal even more obvious. Early in the film Romeo’s first love interest, Rosaline (unseen in the play), appears and explains: “Juliet is a Capulet. The Montagues and the Capulets are mortal enemies!” Later the Nurse will complain: “my back is killing me”’. The film sounds as if the notes to an introductory school edition of Romeo and Juliet had been incorporated into the dialogue to replace or paraphrase Shakespeare’s text.

Nevertheless, Fellowes has preserved Shakespeare’s plot, the dozen events in sequence established by Luigi da Porto in his 1530 novella and lasting through the sixteenth century. As he says, ‘the great speeches are all still in’. Sometimes during those moments – Romeo and Juliet meeting at the party, the balcony scenes – the performances capture the lyricism of Shakespeare’s text. At other times, performances of unexceptional speeches achieve depths beyond what the original script would seem to allow. Damian Lewis’s response to Juliet’s disobedience at the end of the third act, and Paul Giamatti’s preparation of the sleeping potion at the beginning of the fourth, could stand alone as brilliant and original explications of those episodes. Even the Apothecary who appears briefly in the fifth act, played by veteran actor , has an unusually meaningful exchange with Romeo. If Fellowes ignores the kinds of experimentation and social commentary represented by his immediate predecessors, the actors, and perhaps the unsung director, Carlo Carlei, have recovered fragments from the original play and given them new wholeness. They make it seem worthwhile to view this latest film adaptation along with Zeffirelli’s and Luhrmann’s, the better to appreciate the uniqueness of each one.

Jill L. Levenson is an expert in Shakespearean literature, and a professor at Trinity College, the University of Toronto. She has published scholarly articles and books on Shakespeare and his contemporaries, and edited Romeo and Juliet: The Oxford Shakespeare.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or subscribe to Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Movie poster for the 2013 film Romeo and Juliet. By: Amber Entertainment , Indiana Production Company, Swarovski Entertainment. Used to serve as the primary means of visual identification at the top of the article dedicated to the work in question. Via Wikemedia Commons.

The post Romeo & Juliet: the film adaptations appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWatching Titus, feeling fleshMary Hays and the “triumph of affection”Shakespeare and the controversy over Richard III’s remains

Related StoriesWatching Titus, feeling fleshMary Hays and the “triumph of affection”Shakespeare and the controversy over Richard III’s remains

Riots, meaning, and social phenomena

The academic long vacation offers the opportunity to catch-up on some reading and reflect upon it. Amongst my reading this summer was the special edition of Policing and Society devoted to contemporary rioting and protest. It was good reading. I was stimulated, challenged, and enraged by the articles in equal measure — I even agreed occasionally.

Long ago, a pioneer of sociology, Max Weber, drew a distinction between explanations at the level of causality and at the level of meaning. Explaining something — protest and disorder — at the level of causality involves finding that concatenation of conditions that enhance the likelihood that protest and disorder will occur and in the absence of which it will not. Frequently, the contributions to this special edition implicitly attempt to do precisely that. Many of them invoke the ‘usual suspects’ of economic conditions — globalisation, recession, public expenditure cuts, and so forth — as creating pre-dispositions for the occurrence of protest and rioting.

We are all agreed, I think, that the causation of social phenomena is complex and demands multi-factorial explanations. There is no shortage of factors that authors intuitively regard as important. The problem is that if the phenomenon demands multi-factorial explanation, then all the case studies in the world simply won’t cut it. It may seem intuitively obvious why the electrocution of two youths who sought sanctuary from pursuing police in an electricity substation was likely to ignite the banlieues of many French cities. Yet, sadly, deaths following contact with the police are not so uncommon; some of these deaths are intensely controversial, but still they only rarely result in rioting. In the 1960s, American cities were repeatedly convulsed by rioting. When Spilerman (1970; 1971; 1976) examined not just those cities that suffered disorder, but a wide range of cities, he found that economic deprivation, inequality, and other ‘usual suspects’ failed to explain why some erupted in violence and others didn’t.

If we really want causally to explain protests and disorder, we should hand the problem over to mathematicians who are good at detecting patterns and spotting aberrations, however rare their occurrence. It’s simple: collect all the information we possibly can on all manner of variables — social, economic, political, historical, and be sure to include environmental conditions (people rarely riot during winter time) — create a ‘big data’ dataset, and start the supercomputers churning. This could do for social science what ‘big data’ has achieved in meteorology and medicine. Nonetheless, I wager that it will not explain very much.

Why not? The answer lies, I believe, in Weber’s notion of explanations at the level of meaning. As Professor Body-Gendrot puts it in her contribution to this volume: “Inequality is a powerful social divider.” Yes, it is: but it needs to be accompanied by “a rising awareness of inequalities.” People can live peacefully in the most appalling circumstances, whilst their comparatively privilege peers erupt in collective disorder and violence. What would explain such perversity? Well, it would appear that when people are scraping a living, they have little time in which to ponder the conditions that govern their lives and their causes. It is when people do have the time to ponder that they reflect on their circumstances, draw comparisons between their own lives and those of the more privileged — and become angry. It is how people make sense of their deprivations that explains why they protest and become disorderly. Students of protest politics emphasise how issues must be ‘framed’ in order to translate personal woes into collective grievances.

Here too there are formidable problems. How do we know how people interpret and what they believe about, say, the deaths of two youths in a Paris suburb? Asking a suitable sample of rioters why they are rioting, would be hazardous. If we ask people after the event why they rioted, we are likely to obtain self-serving justifications. Another veteran sociological theorist, Thomas Schutz drew an important distinction between ‘in order to’ motives offered in advance of action and after the fact ‘because’ motives. Explanations after the event may well be justifications or neutralisations which were not in play at the time of their actions. Before the event, people may go into riots with few or very ill-informed motives.

There is also the question of ex post facto collective constructions of meaning: when people try to make sense of what they have done they may well rely on the arguments of others or negotiate meanings between themselves. They may be ably assisted in this by academics, who are prone to attribute their own preferred meanings to events like riots. Riots become political Rorschach blots eliciting otherwise hidden meanings, and most academics are clever enough to piece together some sort of persuasive narrative and find some convincing evidence to develop what they say.

Of course, all this is premised on the assumption that such events do have coherent meaning. Sometimes people embark on action without clear purpose or plan. Weber also drew the valid and valuable distinction between instrumental and expressive purposes. We should not, too readily, assume that rioting is instrumental, it may just be expressive: as Paul Rock observed (1981) rioting is ‘fun’. Even worse, it might be both.

We are, I fear, condemned to gaze upon this phenomena from the outside and imagine what might be going in people’s heads.

P.A.J. Waddington is Professor of Social Policy, Hon. Director, Central Institute for the Study of Public Protection, The University of Wolverhampton. He is the co-editor of Professional Police Practice: Scenarios and Dilemmas with John Kleinig and Martin Wright, and a general editor for Policing. Read his previous blog posts.

A leading policy and practice publication aimed at senior police officers, policy makers, and academics, Policing contains in-depth comment and critical analysis on a wide range of topics including current ACPO policy, police reform, political and legal developments, training and education, specialist operations, accountability, and human rights.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Riots – Cars on fire. © MacXever via iStockphoto.

The post Riots, meaning, and social phenomena appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGetting parents involved in educationFood fortificationCelebrating World Anaesthesia Day

Related StoriesGetting parents involved in educationFood fortificationCelebrating World Anaesthesia Day

What patients really want

By Aidan O’Donnell

Picture this scenario. In a brightly-lit room, young women in spotless white tunics apply high-tech treatments to a group of people lying on beds. At first glance, you might think this is a hospital or clinic, but in fact, it is a beauty salon.

We are becoming increasingly familiar with the paradigm that beauty treatments are good for us. Companies use evocative phrases such as “beauty therapy” to associate cosmetic treatments with medical ones. Beauticians wear white smocks suggestive of lab coats. Advertisements for skin and hair products often feature pseudo-technical jargon and complex diagrams, to suggest to consumers that their particular favourites have been lovingly created (or at least formulated and controlled) by white-coated scientists in a high-tech laboratory, rather than churned out of a chemical factory which also produces industrial lubricants and agricultural pesticides. Remember when every shampoo ad had the science part?

The association between cosmetics and pharmaceuticals has created a neologism, cosmeceuticals, which refers to cosmetic products which imply some additional medical or pharmaceutical action.

The cosmetic industry uses these strategies because they are effective in selling products to consumers. By appropriating the trappings of medicine and science, it adds to its products an air of medically-endorsed respectability they might otherwise lack.

Do these initiatives actually make your hair silkier, your skin more lustrous, your wrinkles less noticeable, your eyes more captivating? No! But they make you feel like they do, and that counts: it adds value, which can be expressed in economic terms.

From my point of view as a doctor, this is a deliberate use of the placebo effect. There is a lot of nonsense spoken about the placebo effect, so to avoid confusion, let me specify that I consider the placebo effect to be the added satisfaction patients derive from a treatment, over and above its actual benefit. It is neither quackery nor witchcraft; nor is it closed to the orthodox tools of scientific inquiry. The crux of it is this: the placebo effect makes you feel better, even if it doesn’t make you get better.

The placebo effect is associated with perceived expertise, hence the beauticians in the white coats. It is associated with dramatic treatments, and expensive ones. Most importantly, the placebo effect is associated with the attention of a warm and caring practitioner.

The placebo effect is associated with perceived expertise, hence the beauticians in the white coats. It is associated with dramatic treatments, and expensive ones. Most importantly, the placebo effect is associated with the attention of a warm and caring practitioner.

Most types of complementary and alternative medicine are proven to be no better than placebo, yet they are extremely popular and increasingly mainstream. High-street pharmacies stock herbal and homeopathic remedies alongside more traditional preparations.

Marcia Angell and Jerome Kassirer famously stated in the New England Journal of Medicine (1998) that “There cannot be two kinds of medicine—conventional and alternative. There is only medicine that has been adequately tested and medicine that has not, medicine that works and medicine that may or may not work.”

Angell and Kassirer’s editorial is powerful, forthright and unambiguous. I applaud its clarity, but I can’t help wondering if it misses something very important: patients want the placebo effect. In fact, some of them are prepared to shun orthodox medicine and pay money to practitioners who can provide them with only the placebo effect.Worldwide, people spend over US$100 billion on complementary or alternative medicine. It seems that people are voting with their wallets, for treatments which don’t “work”.

To be clear, I do not consider such people to be credulous fools. Instead, I think they are looking for something which orthodox medicine doesn’t quite recognise the value of.

In New Zealand, the UK, and other countries, doctors are no longer permitted to wear white coats. This is because it has been shown that white coats are a vector of infection which can be transmitted from patient to patient via the doctors’ sleeves. Similarly, neckties have been banned in most hospitals. As a result, doctors turn up to work wearing short-sleeved shirts with no tie: they don’t really look like doctors any more.

This impacts not one whit on the quality of care such doctors provide. But it diminishes doctors’ status in the eyes of some patients, makes it hard for patients to figure out who the doctor is, and creates the irony that just about the only people these days who dress like doctors are actually beauticians.

What can doctors do about all this? The first thing is to oppose erosion of the status of the medical profession in the eyes of the public. We are still trusted, we are still valued, and I believe being a doctor is still something meritorious and honourable.

The second thing is to reclaim the placebo effect, and learn how to use it to our own advantage. The placebo effect isn’t something to be used in place of orthodox medicine, but something which can be added to it. The placebo effect lies in the solid relationship between the doctor and the patient. We can harness the placebo effect to our orthodox treatments, and provide therapies which both make our patients get better and feel better.

Because they’re worth it.

Aidan O’Donnell is a consultant anaesthetist who works in New Zealand. He is a Fellow of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and a Fellow of the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists. He is the assistant editor of the current edition of the Oxford Handbook of Anaesthesia, and author of Anaesthesia: A Very Short Introduction. You can also see his previous post on Propofol and the Death of Michael Jackson.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday, subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS, and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Blond woman with white coat is writing on a clipboard via iStock photo

The post What patients really want appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCelebrating World Anaesthesia DayThe economics of cancer careCookstoves and health in the developing world

Related StoriesCelebrating World Anaesthesia DayThe economics of cancer careCookstoves and health in the developing world

October 17, 2013

Cookstoves and health in the developing world

Many in the developing world rely on crude indoor cookstoves for heat and food preparation. The incidence of childhood pneumonia and early mortality in these regions points to the public health threat of these cultural institutions, but as Gautam Yadama and Mark Katzman show, simply replacing the stoves may not be the simple solution that many presume. In Fires, Fuel, and the Fate of 3 Billion, they examine the difficult issues at play and the following slideshow extracts some of their photographic and scientific discourse on cookstove use in rural India shines a beautiful light on this underrepresented social and public health issue.

Man showing his solar charging panels

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Unexpectedly, in midst of threadbare living, people adopt and invest in new technologies that they consider necessary. Living without electricity, but cannot do without a cell phone. Enter small general stores that supply solar panels for charging.

farmers with bullocks weeding their crop

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Providing access to clean, cost-effective energy systems for the poor is clearly a complex undertaking. Risk laden livelihoods dependent on rain-fed agriculture in drought prone regions complicate the dissemination and implementation of such innovations.

kids running around outdoor fires and smoke from charcoal making

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Making charcoal to meet the energy demands of a distant urban household takes its toll on the health of women and children. Children in the midst of rising smoke from large piles of burning invasive mesquite wood that mothers tend to all day.

night fires burning in homes

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Smoke billows from Missing tribal households, fires burning from morning until night, providing food and comfort. Missing households without these fires are not traditional.

woman on a bamboo platform cooking

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Tradition-bound, communities on the river islands of Brahmaputra, Assam, keep the wood burning. Women get household fuel from three significant sources: driftwood from the river, Kalmu –dried stalks of a riverbank weed, or wood from Casuarina trees from outlying islands.

Woman in polka dots carrying wood

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

She endures the weight of a cultural expectation, compounded by household poverty, to shoulder a globally consequential burden: providing daily fuel for her household. They pour out of jungles carrying firewood to heat their homes, to cook hot meals for their families. Photograph by Mark Katzman.

Gautam N. Yadama is the author and Mark Katzman the photographer of Fires, Fuel, and the Fate of 3 Billion: The State of the Energy Impoverished. Gautam N. Yadama, PhD, is an Associate Professor at the Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis, and a Faculty Scholar in Washington University’s Institute of Public Health. His research transcends disciplinary boundaries to better understand and address complex energy, environment, health, and sustainability problems central to social wellbeing of the poor. Mark Katzman has traveled the globe as a distinguished commercial photographer, on assignments from such publications as Time, Newsweek, Audubon, Backpacker, Food and Wine, Forbes, and Fortune, and international companies. Named one of the 200 Best Advertising Photographers in the World in 2012 by Luerzer’s Archive, Katzman is considered an international expert on the photogravure process.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: All photos copyright Mark Katzman.

The post Cookstoves and health in the developing world appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesChildren’s invented notions of rhythms“Deuce,” “doozy,” and “floozy.” Part 1Food fortification

Related StoriesChildren’s invented notions of rhythms“Deuce,” “doozy,” and “floozy.” Part 1Food fortification

Children’s invented notions of rhythms

What is your earliest musical memory? How has it formed your creativite impulse? Jeanne Bamberger’s research focuses on cognitive aspects of music perception, learning, and development, so when it came to reviewing her work, she thought of her own earliest musical experiences. The following is an adapted extract from Discovering the musical mind: A view of creativity as learning by Jeanne Bamberger.

My piano studies began at the age of 4 or 5 with the neighborhood music teacher, Miss Margaret Carlson. It was only sometime later that I learned that Miss Carlson had been a student of Jacque Dalcroze in Geneva, Switzerland. With this news, I recognized that Miss Carlson’s Dalcroze studies had actually formed the background for our piano lessons and also the Saturday morning visits to her house where I, along with her other neighborhood piano students, participated in group Eurythmics lessons. I now realize that it was through these Eurythmics sessions that I first experienced an aspect of music that has strongly influenced my whole musical development and, more recently, the direction of my research. It was the experience of participating in actively shaping musical time by expressing through movement, the motion of a phrase as it evolved towards its goals.

Much later, as a teenager, I was a student of Artur Schnabel, and looking back I can now see that these two widely separated studies had surprising and important aspects in common. Schnabel’s teaching, like his playing, also focused intensely on the motion of the phrase as it makes and shapes time. He told us, ‘Practicing should be experiment, not drill,’ and experiment meant primarily experimenting with possible structural groupings — possible moments of arrival and departure of a melody line and how best to project these structural gestures as we made them into sound moving through time.

After an excursion into philosophy, and still later, in my studies with Roger Sessions, shaping time was again an important focus. But now, it was the hierarchy of such structures along with just how the composer had generated these nested levels of organized motion. As he said, we must pay attention to the ‘details and the large design’ as each creates and informs the other.

Looking back, I see more clearly that these earlier and later musical experiences and the associated academic studies were the germinal seeds from which my present interests have grown. Without them, I think I would have failed to notice the intriguing puzzles and the often hidden clues that children give us concerning what they are attending to in listening to or clapping even a simple rhythm, or following a familiar melody. For it is eminently clear that a feeling for the motion of a phrase, its boundaries, and its goals along with its inner motion, the motive or figure, are the natural, and spontaneous aspects of even very young children’s musical experience. Indeed, I find that it is the continuing development of these early intuitions (the capacity for parsing a continuous musical ‘line’) that nourishes the artistry of mature musical performance, as well — the performer’s ability to hear and project the directed motion of a phrase and the relationships among phrases as the ‘large design’ unfolds in time.

With all this in mind, I went back to revisit the children’s invented notations for simple rhythms and melodies that I had collected back in the 1970’s. Going through the old cardboard box in which I had stored some two hundred children’s drawings, I found myself intrigued and puzzled all over again. I saw in the drawings the centrality of the children’s efforts to capture movement and gesture, but there was another aspect as well. Looking at one drawing after another, I marveled at how and why the children, like philosophers, scientists, and musicians, have continued to work at finding means with which to turn the continuous flow of our actions — clapping a rhythm, bouncing a ball, swinging on the park swing — into static, discrete marks on paper that hold still to be looked at ‘out there.’

The children’s invented notations helped me to see the evolution of learning and the complexity of conceptual work that is involved in this pursuit. Looking at the children’s inventions, I saw that this complexity sometimes emerges in comparing one child’s work with that of another’s. And sometimes complexity can be seen by watching one child as from moment-to-moment she transforms for herself the very meaning of the phenomena with which she is working. Caught on the wing of invention, the notations mirror in their making the process through which learning and the silence of perception can be made visible. The inventions become objects of reflection and inquiry for both child and teacher as together they learn from one another.

But this very reflection reveals a critical paradox. Christopher Hasty in his book Meter as rhythm, makes the paradox poignantly clear:

As something experienced, rhythm shares the irreducibility and the unrepeatability of experience…when it is past, the rhythmic event cannot be again made present…Rhythm is in this way evanescent: it can be ‘grasped’ but not held fast. (Hasty, 1997, p.12)

The paradox also helps us recognize that the serious study of children’s spontaneous productions requires taking a bold step: In order to understand another’s sense-making, we must learn to question our own belief systems, to interrogate and make evident the deeply internalized assumptions with which we make the musical sense that we too easily think is ‘just there.’

The task of reflection thus becomes one that is mutual and reciprocal between teacher and student. It follows that the most evocative situations, the most productive research questions, often occur during passing moments of learning in the real life of the classroom or the music studio. It is noticing and holding fast these fleeting moments that arise unexpectedly, puzzling events caught on-the-fly, that teaching and research, instead of being separate and different kinds of enterprises, become a single, mutually informing one.

Jeanne Bamberger is Emerita Professor of Music and Urban Education at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where she taught music theory and music cognition. She is currently Visiting Scholar in the Music Department at UC-Berkeley. Bamberger’s research focuses on cognitive aspects of music perception, learning, and development. She is the author of Discovering the Musical Mind: A view of creativity as learning.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image via iStockphoto.

The post Children’s invented notions of rhythms appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesInterview with Charles Hiroshi Garrett“Deuce,” “doozy,” and “floozy.” Part 1Developing countries in the world economy

Related StoriesInterview with Charles Hiroshi Garrett“Deuce,” “doozy,” and “floozy.” Part 1Developing countries in the world economy

Getting parents involved in education

Problems of truancy, violence, and discipline can contribute to many schoolchildren in industrialized societies graduating from school without mastering basic skills. Increasing parental involvement has been widely considered as a means of overcoming these difficulties, and significant amounts of funding are available to programs which promise to increase parental participation. However, it is still not clear whether schools can really act on parental involvement.

Using a randomized experiment run in the school district of Créteil, France, we can show that simple meetings between parents and the school head can lead to substantial improvement in parental involvement and student behavior. In particular, by the end of the school year, the program is associated with a decline of about 25% in truancy. We also show that the behavior of all students in the selected classes improved, including those whose parents did not participate.

The school district of Créteil is a densely populated area of suburbs east of Paris with large populations of recent and second-generation immigrants. These parents face numerous barriers to navigating the hierarchical education system: many speak limited French and work far away from local schools. In this environment, we sought to discover whether increasing parental awareness and involvement has the potential to improve children’s educational success in local middle schools.

The school district of Créteil is a densely populated area of suburbs east of Paris with large populations of recent and second-generation immigrants. These parents face numerous barriers to navigating the hierarchical education system: many speak limited French and work far away from local schools. In this environment, we sought to discover whether increasing parental awareness and involvement has the potential to improve children’s educational success in local middle schools.

At the beginning of the 2008–2009 school year, parents in about 200 sixth-grade classes were asked to volunteer for a program of three facilitated discussions with the school staff on how to successfully navigate the transition to middle school. Around 1,000 parents (22% of the total) volunteered for the program. In a randomly selected half of the classes, the parents who had previously volunteered were invited to participate in the discussions. By randomly selecting a subset of all the parents willing to participate in the program, we were able to compare parents who participated to a valid comparison group: parents who would have participated in the program had they been given the opportunity. This allows us to separate the effects of the program from the effect of parents’ preexisting involvement in their children’s education. Discussions were facilitated by the school head, drawing upon precise guidelines designed by the district’s educational experts and were open to all volunteer parents in the treatment classes. Facilitators were given standard materials, including a DVD explaining the purpose of various school personnel and documents explaining the functions of the various school offices.

Parents in the selected classes who had volunteered to attend changed their behavior significantly in response to the program. They were more likely to make individual appointments with teachers and more likely to participate in parents’ organizations. On a questionnaire of their involvement in children’s education at home, these parents also scored 40% of a standard deviation higher than their volunteer counterparts in comparison classes. This change in parental involvement is of the same magnitude as the initial gap in involvement between blue-collar and white-collar families. However, there were no changes in parental involvement among parents in the selected classes who had not initially volunteered for the meetings.

This increase in parental involvement caused a large improvement in student behavior, and this improvement was seen even in classmates whose parents were not volunteers and did not attend meetings. For instance, children of volunteer parents in selected classes were 15% less likely to be sanctioned for disciplinary reasons than children of volunteer parents in non-selected classes, and children of non-volunteer parents in selected classes were 8 percent less likely to be sanctioned than their comparison class counterparts. Similar results were seen in other measures of behavior improvement: truancy decreased by 25%, and the proportion who received honors increased by 10%. These improvements in behavior also had a limited but significant impact on children’s test scores in French, though these impacts were concentrated among the children of volunteer parents

Overall, our results show that low levels of parental involvement are not a fatality in poor neighborhoods. Schools have the critical ability to trigger higher levels of involvement among parents: parental attitudes and school involvement can be significantly upgraded through simple participation programs and that such policies have a potential for reducing disciplinary problems in young teenagers. These findings are further consistent with the fact that the initial treatment has first influenced the attitude of children of volunteer parents through repeated family interactions, which has in turn progressively influenced the attitude of children of non-volunteer parents through repeated classroom interactions all over the school year. The fact that these benefits were enjoyed even by students whose parents did not participate in meetings contradicts the view that parental involvement campaigns are bound to benefit only the small fraction of actively participating families.

Francesco Avvisati is an analyst for the OECD. Marc Gurgand is Associate Member at the Paris School of Economics. Nina Guyon has a PhD from the Paris School of Economics. Éric Maurin is Associate Chair at the Paris School of Economics.

The Review of Economic Studies aims to encourage research in theoretical and applied economics, especially by young economists. It is widely recognised as one of the core top-five economics journal, with a reputation for publishing path-breaking papers, and is essential reading for economists.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only education articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Crossing the Street. By LuminaStock, via iStockphoto.

The post Getting parents involved in education appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDeveloping countries in the world economyFive reasons why China has the most interesting economy in the worldAnother kind of government shutdown

Related StoriesDeveloping countries in the world economyFive reasons why China has the most interesting economy in the worldAnother kind of government shutdown

October 16, 2013

“Deuce,” “doozy,” and “floozy.” Part 1

Don’t hold your breath: all three words, especially the second and the third, came in from the cold and will return there. Nor do we know whether anything connects them. Deuce is by far the oldest of the three. Our attestations of it go back to the middle of the seventeenth century; 1650 (assuming that it was approximately then that deuce came into existence) is too late for reconstructing an ancient native coinage. This point will be belabored below. Most probably, the word reached English from abroad. The sixteen-hundreds witnessed great wars, which meant not only a mountain of corpses and the triumph of wilderness but also the movement of great masses of population (an amalgamation of races, to use a phrase George Babington Macaulay liked). Mercenaries, adventurers, prostitutes, and the riffraff of all kinds (“ragtag and bobtail”) moved from country to country and made their slang and curses international (compare what is said in the post on Old Nick). Given the circumstances, it follows that deuce did not have to be taken over from French, the richest source of our borrowings: one can rather expect an infusion of vulgar colloquialisms from the north of Germany and the Netherlands. German has the exclamation ei der Daus, roughly equivalent to Engl. the deuce (he did); der is the article. The diphthong au in Daus corresponds to uu in Low (= northern) German. The form duus would become doos/deuce in English.

This derivation looks plausible, for the coincidence, down to the use of the definite article, is impressive. Skeat, at the beginning of his career as an etymologist, traced Engl. deuce to Latin deus “god” and with the self-confidence he lost in later years pooh-poohed all possible objections. Indeed, in imprecations the words for “God” and “Devil” are sometimes nearly interchangeable. Thus, the Italian curse Domine! and Engl. gosh!, Lor’ (the latter an alteration of God and Lord) do not become gentle or particularly sweet despite the absence of Devil in them. A profanity remains a profanity, however we may mask it. Yet Skeat did not do justice to the German word, for daus might perhaps be a “corruption” of deus, but duus could not. A lively exchange between Frank Chance and A. L. Mayhew, who attacked Skeat and each other, is a typical example of late nineteenth-century British journalism. Mayhew was especially trenchant, even vicious, and I have never been able to figure out his relations with Skeat. They heaped invective on each other in public (especially Mayhew did, but Skeat’s irascibility, too, has become proverbial) and ended up by co-authoring a book on the history of English sounds. Later, Skeat gave up his conjecture and agreed with opinion of the OED, about which see Part 2 next week.

As noticed long ago, the Venerable Bede, the great Old English historian of the Church (672 or 673 to 735), mentioned the demons called dusii. They were said to appear as male seducers to women and as female seducers to men. Bede’s source may have been Isidore of Seville (ca. 560-636), the author of the widely read book Etymologiae; he also mentioned “German” dusius. The Dutch philologist Franciscus Junius Jr. (1545-1632) repeated Isidore’s derivation, and nowadays Elmar Seebold, the leading German etymologist, does not find it improbable. The path from Gallo-Romance dusius to Duus/deuce would have been straight but for an almost fateful chronological hitch. The German word surfaced in the fifteenth century, two centuries before it made its entry on English soil, but no traces of it exist between the days of Isidore (and Bede) and the late Middle Ages. To be sure, such words may have been avoided by the authors of early works. However, the gap of almost 800 years in attestation almost invalidates dusius as the etymon of duus.

There has also been no lack of attempts to derive duus and deuce, through a sting of phonetic changes, from Latin diabolus “devil.” Considering how ingeniously the words of “God” and “Devil” are mutilated by taboo, this hypothesis cannot be rejected out of hand. Yet if such were the origin of the words in question, they should probably have come to German and English from some northern French dialect. Various contracted forms of diabolus have been cited, but from the south of France, and even there the match is not too good. Hensleigh Wedgwood, the best-known etymologist before the time Skeat made all his predecessors obsolete (which is not the same as irrelevant), insisted on the derivation of deuce from the Scandinavian word for “giant; hobgoblin, monster” (tuss, tusse, tosse, with ss from rs; Old Icelandic þurs, that is, thurs). But this idea is hard to defend because contrary to tuss, the vowel is long in duus and deuce, and because Engl. deuce is a likely borrowing of German duus (Scandinavian influence in Germany can be dismissed as improbable). Wedgwood, it seems, found no supporters.

For curiosity’s sake I may mention the suggestion that deuce owes its origin to the name of the Roman general Claudius Drusus. The name became so dreaded among the “Teutons” that its very sound filled them with horror. This source of the word for “devil” might perhaps impress a Dutch speaker, for Dutch droes, rhyming with Engl. deuce but having a shorter vowel, means “Devil.” Still we would like to know what happened to r after d. In Dutch, droes has been known since Cornelis Kiliaan, a distinguished lexicographer, recorded it, but the first edition of his dictionary appeared only in 1599, while Claudius Drusus died at the beginning of the Common Era. According to the Drusus-droes etymology, droes, like Gallo-Romance dusius, must have led an underground existence for many centuries before it surfaced in a modern language.

YE OUP BLOG DEUCE,

YE OUP BLOG DEUCE,

Ye Onlie True and Original Devil.

Beware of Ye Imitations.

All others are Counterfeit.

Caution requires that we stay away from both ancient words in our search for the origin of deuce and droes, but we need not ignore the fact that between the fifteenth and the seventeenth century similar sounding names of the devil emerged in German, Dutch, and English. We may be dealing with loosely related slangy formations. Migratory slang is a serious problem. Latin muger meant “a cheat at dice.” It resembles Modern French mouche “spy,” Engl. mooch, the root of Engl. s-mugg-le, and the verb to mug (all the words sound alike and refer to underhand or criminal activities). If they are “loosely related,” as dictionaries like to say in such cases, we get an example of slang traveling from land to land for millennia. In endless peregrinations an inserted r (duus versus droes) becomes a dispensable obstacle. Those are interesting fantasies.

At this stage, we will only agree that deuce and duus ~ daus seem to belong together. The rest should wait until next week, when dice and suggestive personal names return to haunt us. Let us hope that the etymological devil is not as black as he is painted. In the meantime, read the caption under the picture. It is a parody of a notice in a famous story. Try to guess what story is meant. If you succeed, leave a comment. If you don’t succeed, do the same.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Bust of Drusus the Elder (Nero Claudius Drusus), in the Musée du Cinquantenaire, Brussels. Photo by ChrisO, Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

The post “Deuce,” “doozy,” and “floozy.” Part 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAn interludeOstentatious breeches, gods’ braggadocio, and ars poeticaAre you daft or deft? Or, between lunacy and folly

Related StoriesAn interludeOstentatious breeches, gods’ braggadocio, and ars poeticaAre you daft or deft? Or, between lunacy and folly

Food fortification

Today (16 October 2013) is World Food Day and it’s sobering to think that globally more than two billion people are affected by micronutrient malnutrition, most commonly presenting as vitamin A deficiency, iron deficiency, anaemia, and iodine deficiency disorders. Alleviating micronutrient malnutrition is now firmly on the agendas of United Nations agencies and countries around the world.

Food fortification, that is the addition of one or more nutrients to a food whether or not they are normally contained in the food, is receiving much attention as a potential solution for preventing or correcting a demonstrated nutrient deficiency. It is a powerful technology for rapidly increasing the nutrient intake of populations. Political agendas and technological capacities are combining to significantly increase the number of staple foods that are being fortified, the number of added nutrients they contain and their reach. Across the world approximately one third of the flour processed in large roller mills is now being fortified.

Yet food fortification is a complex and contested technological intervention. Proponents of food fortification point to the ability of this technology to be introduced relatively quickly and delivered efficiently through centralised food systems to increase an individual’s nutrient exposure without the need for dietary behaviour change. Public-private partnerships involving collaborations between governments and the private sector are substantially increasing the capacity of governments to develop and implement food fortification interventions around the world. For example, the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) is the primary vehicle globally brokering among governments, non-government organisations, the private sector, and civil society to promote food fortification. GAIN receives funding from a number of public and private sector donors, including the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and USAID.

Those who are more cautious about food fortification highlight that there are alternative policy interventions available to correct nutrient deficiencies. There are public health, social, and agriculture development measures available to promote food security and healthy dietary behaviours. For example, the Food and Agriculture Organization has proclaimed that “Sustainable Food Systems for Food Security and Nutrition” will be the focus of World Food Day in 2013. Some suggest that food fortification policy decisions should be made with regard to uncertainties about scientific evidence and ethical considerations. Scientific uncertainties relate to the public heath effectiveness as well as safety implications of food fortification. Ethical considerations – associated with increasing nutrient exposure resulting from food fortification – relate to balancing the rights of individuals, population groups and the population as a whole. How do we decide when to select food fortification and/or an alternative policy intervention as the preferred approach to tackle inadequate nutrient intake within a population?

It is my view that an evidence-informed approach to food fortification policy-making starts with the recognition that not all causes of inadequate nutrient intake are the same. Too often food fortification policy is made because of the perception it offers a relatively easy and immediate quick fix to a health problem resulting from an inadequate nutrient intake, irrespective of the cause of the inadequacy. A failure to consider the underlying cause of an inadequate nutrient intake risks putting in place an ineffective policy intervention, or worse, one that carries safety concerns as well as adverse ethical implications.

Successful food fortification interventions have been those where the technology has been used to directly tackle the underlying cause of an inadequate nutrient intake such as addressing inherent nutrient deficiencies in the food supply. For example, universal salt iodization has been highly effective in reducing the prevalence of iodine deficiency disorders around the world with minimal risks (when implemented in accordance with policy guidelines) and minimal adverse ethical implications.

Conversely, potential health risks and adverse ethical implications have resulted when food fortification policies have been developed and implemented with a lack of consideration of the underlying cause of an inadequate nutrient intake. For example, mandatory flour fortification with folic acid has been implemented in approximately 70 countries around the world as an intervention to reduce the prevalence of neural tube defects (NTDs). This policy intervention has been based on compelling epidemiological evidence that folic acid can reduce the risk of a relatively small number of women experiencing a NTD-affected pregnancy. However, NTDs have an uncertain multifactorial aetiology in which genetics plays a major role. What the evidence also shows is that for the small number of women who may be genetically predisposed to a raised folic acid requirement, folic acid is exerting its protective influence by acting more as a therapeutic agent than as a conventional nutrient. In these circumstances targeted folic acid supplementation or voluntary flour fortification with folic acid are policy interventions that are more directly tackling the underlying genetic cause of the policy problem. These policy interventions are associated with less health risks and adverse ethical implications than mandatory flour fortification with folic acid. The mandatory fortification policy intervention results in the exposure of everyone in the population who consumes flour, including infants, children, teenagers, men and older adults, to a lifetime of raised synthetic folic acid despite little evidence of any health benefit, but possible harm.

In the future, food fortification interventions look set to become progressively more widespread. Ongoing monitoring and evaluation of the impact of individual and collective food fortification activities on the nutrient composition of foods, population nutrient intakes, health outcomes, and food system operations, will be critical to inform policy and practice to protect and promote public health.

Mark Lawrence is an Associate Professor of Public Health Nutrition in the Population Health Strategic Research Centre at Deakin University. His latest book is Food Fortification: The evidence, ethics, and politics of adding nutrients to food (Oxford University Press).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: apple filled with pills – vitamins concept. © diosmic via iStockphoto.

The post Food fortification appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCelebrating World Anaesthesia DayAnnouncing the Place of the Year 2013 Longlist: Vote for your pickWorld Arthritis Day – promoting awareness of rheumatic diseases

Related StoriesCelebrating World Anaesthesia DayAnnouncing the Place of the Year 2013 Longlist: Vote for your pickWorld Arthritis Day – promoting awareness of rheumatic diseases

Developing countries in the world economy

In the span of world history, the distinction between industrialized and developing economies, or rich and poor countries, is relatively recent. It surfaced in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. In fact, one thousand years ago, Asia, Africa and South America, taken together, accounted for more than 80% of world population and world income. This was attributable in large part to Asia, where just two countries, China and India, accounted for approximately 50% of world population and world income.

The overwhelming significance of these three continents in the world economy continued for another five centuries until 1500. The beginnings of change are discernible from the early sixteenth century to the late eighteenth century, as Europe created the initial conditions for capitalist development. Even so, in the mid-eighteenth century, the similarities between Europe and Asia were far more significant than the differences. Indeed demography, technology, and institutions were broadly comparable.

The Industrial Revolution in Britain during the late eighteenth century, which spread to Europe over the next fifty years, exercised a profound influence on the shape of things to come. Yet in 1820, less than 200 years ago, Asia, Africa, and South America still accounted for almost three-fourths of world population and around two-thirds of world income. The share of China and India, taken together, was 50% even in 1820.

The dramatic transformation of the world economy began around 1820. Slowly but surely, the geographical divides in the world turned into economic divides. The divide rapidly became a wide chasm. The economic significance of Asia, Africa, and Latin America witnessed a precipitous decline such that by 1950 there was a pronounced asymmetry between their share of world population at two-thirds and their share of world income at about one-fourth.

In sharp contrast, between 1820 and 1950, Europe, North America, and Japan increased their share in world population from one-fourth to one-third and in world income from more than one-third to almost three-fourths. The rise of ‘The West’ was concentrated in Western Europe and North America. The decline and fall of ‘The Rest’ was concentrated in Asia, much of it attributable to China and India.

The Great Divergence in per capita incomes was, nevertheless, the reality. In a short span of 130 years, from 1820 to 1950, as a proportion of GDP per capita in Western Europe and North America, GDP per capita in Latin America dropped from 3:5 to 2:5, in Africa from 1:3 to 1:7, and in Asia from 1:2 to 1:10. But that was not all. Between 1830 and 1913, the share of Asia, Africa, and Latin America in world manufacturing production (attributable mostly to Asia, in particular China and India) collapsed from 60.5% to 7.5% — while the share of Europe, North America, and Japan rose from 39.5% to 92.5%, to stay at these levels until 1950.

The industrialization of Western Europe and the de-industrialization of Asia during the nineteenth century were two sides of the same coin. The century from 1850 to 1950 witnessed a progressive integration of Asia, Africa and Latin America into the world economy, which created and embedded a division of labour between countries that was unequal in its consequences for development. The outcome of this process was the decline and fall of Asia and a retrogression of Africa, although Latin America fared better. Consequently, by 1950, the divide between rich industrialized countries and poor underdeveloped countries was enormous.

During the six decades beginning 1950, changes in the share of developing countries in world output and in levels of per capita income relative to industrialized countries, provide a sharp contrast. In terms of PPP statistics, the share of developing countries in world output stopped its continuous decline circa 1960, when it was about 25%, to increase rapidly after 1980, so that it was almost 50% by 2008, while the divergence in GDP per capita also came to a stop in 1980 and was followed by a modest convergence thereafter, so that as a proportion of GDP per capita in industrialized countries it was somewhat less than 1:5 in 2008.

There was a significant catch-up in industrialization for the developing world as a whole beginning around 1950 that gathered momentum two decades later. Between 1970 and 2010, in current prices, the share of developing countries in world industrial production jumped from 13% to 41%, while their share in world exports of manufactures rose from 7% to 40%.

It is clear that, during the second half of the twentieth century and the first decade of the twenty-first century, there was a substantial catch-up on the part of developing countries. In 2008, the share of developing countries in world GDP was close to their share around 1850, while their GDP per capita as a proportion of that in industrialized countries was about the same as in 1900. The share of developing countries in world industrial production remained at its 1913 level until 1970. By 2010, however, this share was higher than it was in 1860 and possibly close to its level around 1850.

On the whole, the significance of developing countries in the world economy circa 2010 is about the same as it was in 1870 or a little earlier. Given this situation in 2010, which is an outcome of the catch up process since 1950, it is likely that the significance of developing countries in the world economy circa 2030 will be about the same as it was in 1820.

This is an untold story. Some important questions arise. First, why did the countries and continents, now described as the developing world, experience such a decline and fall in the short span of time from 1820 to 1950? Second, what were the factors underlying their catch up in output, income, and industrialization since 1950? Third, how was this catch up distributed between continents, countries, and people? Fourth, is it possible to learn from recent experience, and the past, about the future of developing countries in the world economy?

Deepak Nayyar is Emeritus Professor of Economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, and was, until recently, Distinguished University Professor of Economics at the New School for Social Research, New York. He is the author of Trade and Globalization.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Close-up of crystal globe on financial papers with orange light in background. © tetmc via iStockphoto.

The post Developing countries in the world economy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOn shutdown politics: why it is not the Constitution’s faultAnother kind of government shutdownAccelerating world trend to abolish capital punishment

Related StoriesOn shutdown politics: why it is not the Constitution’s faultAnother kind of government shutdownAccelerating world trend to abolish capital punishment

From Boris Johnson to Oscar Wilde: who is the wittiest of them all?

Today marks the publication of the fifth edition of the Oxford Dictionary of Humorous Quotations under the editorship of broadcaster and former MP Gyles Brandreth. But who is the wittiest of them all? Of the 5,000 sharpest, wittiest, and funniest lines recorded in the new edition of the Dictionary, Gyles here reveals the people most quoted in its pages, and also highlights his personal top ten favourite quotations.

By Gyles Brandreth

Most Quoted in the Oxford Dictionary of Humorous Quotations – The magnificent seven

It is fitting to see that today, on Oscar Wilde’s birthday, Wilde is leagues ahead of the rest of the pack. He is without doubt the most quoted and quotable of them all. Bernard Shaw’s plays may not be performed as often as once they were, but his lines remain memorable. Woody Allen is the only living person to make the top ten and he has pushed the great eighteenth century lexicographer and wit, Dr. Johnson, into eighth place.

Oscar Wilde (1854–1900) – 92 entries

George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950) – 55 entries

Noel Coward (1899–1973) – 53 entries

Mark Twain (1835–1910) – 43 entries

Dorothy Parker (1893–1967) – 43 entries

P. G. Wodehouse (1881–1975) – 42 entries

Woody Allen (1935–) – 35 entries

Statue of Oscar Wilde in Merrion Park, Dublin

Wittiest Women – The top five most quotedIn this edition of the Dictionary, women feature more than ever before. As well as the classic wit of Jane Austen and George Eliot, and established favourites such as Dorothy Parker and Mae West, twenty-first century newcomers include Jo Brand and Miranda Hart.

Dorothy Parker (1893–1967)

Mae West (1892–1980)

Fran Lebowitz (1946–)

Joan Rivers (1933–)

Margaret Thatcher (1925–2013)

Priceless British Politicians – The top five most quoted

Margaret Thatcher was not noted for her sense of humour, but she is in the top five because she said some memorable things, such as this oft-quoted line: ‘If you want anything said, ask a man. If you want anything done, ask a woman.’ Sometimes Thatcher’s lines were written for her by speech-writers; that’s the one difference between her and the men in the list, all of whom created their own lines. Interestingly, Conservatives appear to be consistently more amusing than other politicians. The most-quoted American politician in the Oxford Dictionary of Humorous Quotations is Adlai Stevenson, followed closely by Ronald Reagan.

Winston Churchill (1874–1965)

Benjamin Disraeli (1804–81)

Boris Johnson (1964–)

Margaret Thatcher (1925–2013)

Harold Macmillan (1894–1986)

Brandreth’s Choice – Top ten humorous quotations of all time

My personal top ten selection reflects the range of contributors to the Dictionary – and what’s making me smile today. The joy of a dictionary like this is that, with over 5000 quotations, I can have ten different favourites every week and not run out of them for ten years.

Gyles Brandreth

1. “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” – Jane Austen (1775–1817)

2. Nancy Astor: “If I were your wife I would put poison in your coffee!” Winston Churchill: “And if I were your husband I would drink it.”

3. “I never forget a face, but in your case I’ll be glad to make an exception.” – Groucho Marx (1890-1977)

4. “Between two evils, I always pick the one I never tried before.” – Mae West (1892–1980)

5. “To lose one parent, Mr. Worthing, may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness.” – Oscar Wilde (1854–1900)

6. “If not actually disgruntled, he was far from being gruntled.” – P. G. Wodehouse (1881–1975)

7. “If God had wanted us to bend over, He would have put diamonds on the floor.” – Joan Rivers (1933–)

8. “Knowledge is knowing a tomato is a fruit; Wisdom is not putting it in a fruit salad.” – Miles Kington (1941–2008)

9. “If you lived in Sheffield and were called Sebastian, you had to learn to run fast at a very early stage.” – Sebastian Coe (1956–)

10. “The email of the species is deadlier than the mail.” – Stephen Fry (1957–)

Editor’s Pick – Top five one-liners of the 21st century

1. “My policy on cake is still pro having it and pro eating it!” – Boris Johnson (1964–)

2. “We’re supposed to have just a small family affair.” – Prince William (1982 –) on his wedding

3. “All my friends started getting boyfriends. But I didn’t want a boyfriend, I wanted a thirteen colour biro.” – Victoria Wood (1953–)

4. “I saw that show ‘Fifty Things To Do Before You Die’. I would have thought the obvious one was ‘Shout For Help’.” – Jimmy Carr (1972–)

5. “I will take questions from the guys, but from the girls I want telephone numbers.” – Silvio Berlusconi (1936–)

Do you agree with Gyles’s choices? Let us know in the comments or join in the discussion on Twitter: @OxfordWords #amlaughing.

Gyles Brandreth is a writer, broadcaster, former MP and government whip, now best known as a reporter for The One Show on BBC1, a regular on Radio 4’s Just A Minute and the host of Wordaholics on Radio 4. A former Oxford scholar and President of the Oxford Union, a journalist and award-winning interviewer, a theatre producer, an actor and after-dinner speaker, he has been collecting quotations for more than fifty years.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: (1) Statue of Oscar Wilde. By Arbol01 [CC-BY-SA-3.0] via Wikimedia Commons; (2) Photograph © Gyles Brandreth

The post From Boris Johnson to Oscar Wilde: who is the wittiest of them all? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSagan and the modern scientist-prophetsHow to be an English language tourist?Interview with Charles Hiroshi Garrett

Related StoriesSagan and the modern scientist-prophetsHow to be an English language tourist?Interview with Charles Hiroshi Garrett

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers