Oxford University Press's Blog, page 891

October 21, 2013

Gravity: developmental themes in the Alfonso Cuarón film

Spoiler Alert: This article includes plot details from the film.

Watching Gravity as a professor who teaches child psychology, I could not help but see the developmental themes that resonate with this film. One of the luminous images that lingered with me long after the film ended is the scene in which Ryan Stone (Sandra Bullock) is nestled in the safety of a spacecraft following a grueling battle for her life. She knows this battle is not yet over. In her serene weightless and suspended state, she slowly retracts her limbs into a resting position that brings to mind the image of a fetus in utero. Here director Alfonso Cuarón waits for a sustained pause, a fermata.

Sandra Bullock as Ryan Stone in ‘Gravity’. (c) Warner Bros. Source: gravitymovie.warnerbros.com.

Later, when she is sitting at the controls of the Soyuz space capsule after a period of intense solitude, Ryan is overjoyed to hear the sound of a human voice transmitted over the speaker. It is a playful melodious male voice. The language is not one she understands. Nevertheless, she is transfixed by the voice, the one tether to the world she knows. Just as a young infant is completely engrossed in speech sounds directed to her, Ryan is mesmerized by all that is musical about a voice (prosody) — its melody, tempo, rhythm, phrasing, pauses — without comprehending its content (semantics).

Arbitary connections between sound and assigned meanings defy her. The first sound she attaches to is the howling of a dog in the background of the grainy audio, which she begins to repeat, just as an infant imitates animal sounds and noises with ease. Soothed, she resigns herself to a peaceful and (possibly final) sleep to the sound of what she surmises to be a lullaby, sung by the voice to a young infant.

From what I can recall from a single viewing (and readers are invited to confirm this) the lullaby is sung on repeated pitches that are about a fifth apart. Later, Ryan hums the same interval softly (almost inaudibly) as she prepares the capsule for its final descent to earth. Based on the laws of physics, the interval of a fifth is one of the most pure and consonant intervals that can be produced by two musical tones. Studies show that even as infants, we are drawn to the simple beauty of octaves and perfect fifths. Pythagoras referred to this kind of perfect consonance as ‘the music of the spheres’, ultimately giving Kepler insight into the movement of the planets.

At the end of the film, Ryan escapes the space capsule after it has landed in water and has started to sink, preparing to swim to the surface. A frog is seen swimming by. I am reminded of creatures that are better adapted to live in changing conditions than we are. The amphibious frog begins life as a tadpole with gills but takes in oxygen through both lungs and skin as it develops into a mature frog, allowing it to stay submerged for long periods or hibernate underwater. The human being also begins life submerged in a liquid environment and does not need lungs for survival in the womb. Yet the lungs (which begin to form just one month after conception) must be fully functional when deployed at birth. From that moment on, we will be entirely dependent on the ebb and flow of air to our lungs to live.

Ryan finally breaks the surface of the water for her first gasp of air. We are reminded that human life cannot thrive in the vast emptiness of space nor in the depths of the ocean, but only in the narrow margin, the small interval between sea and sky.

The last scene shows Ryan finally reaching the shores of a beach, lying face down at the water’s edge. Her time in a weightless environment has taken a toll on her muscles. Like the young infant passing through early motor milestones, she musters up enough strength to raise her head for a moment before her chin meets mud again. Gradually she raises her head up higher, her shoulders, and then her chest. Like the typical infant, whose upper body is many times stronger than the lower limbs, Ryan draws herself up to a crawling posture mainly by the strengths of her arms — legs collapsing beneath her until they are finally engaged. At last, Ryan is seen standing upright and taking her first steps on the beach, her stiff ankles giving her the gait of an unsteady toddler. And in the developmental progression of a single human being echoes the achievements of an entire species.

Siu-Lan Tan is an Associate Professor of Psychology at Kalamazoo College, where she has taught developmental psychology and psychology of music for 15 years. She is co-editor and co-author of the recently published 2013 book, The Psychology of Music in Multimedia. It is the first book to consolidate the research on the role of sound and music in film, television, video games, and computer interfaces. A version of this post also appears on Siu-Lan’s blog, What Shapes Film: Elements of the Cinematic Experience on Psychology Today. Read her previous OUPblog articles.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only television and film articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Gravity: developmental themes in the Alfonso Cuarón film appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow film music shapes narrativeSolomon Northup’s 12 Years a Slave, slave narratives, and the American publicRomeo & Juliet: the film adaptations

Related StoriesHow film music shapes narrativeSolomon Northup’s 12 Years a Slave, slave narratives, and the American publicRomeo & Juliet: the film adaptations

Place of the Year: History of the Atlas

At the end of each year at Oxford University Press, we look back at places around the globe (and beyond) that have been at the center of historic news and events. In conjunction with the publication of the 20th edition of Oxford Atlas of the World we launched Place of the Year (POTY) 2013 last week. In honor of 20 editions of the Atlas, we put together a longlist of 20 nominees that made an impact heard around the world this year. If you haven’t voted, there’s still time! (Vote below.)

Many may wonder what’s so special about an atlas when websites like Google Maps put the entire world in our hands. The true beauty of an atlas is difficult to recreate without the traditional concept of paper and binding. What you could spend hours searching the web for is pulled into just one place when you reach for an atlas. A collection of computer-derived maps using digital cartographic techniques, up-to-date world statistics, satellite imagery of Earth, and details including the latitude and longitude of cities are only some of the many things you may find together in an atlas.

Atlases are a perfect resource not only for glancing back at what the world looked like years ago, but how we once viewed the world. When reflecting on past editions of the Atlas of the World, we learned some interesting things about the publication of an atlas, how exactly the world had changed over the years, and how our views of the world have changed.

Atlas of the World: Key Changes over the Years

1992 (1st Edition): The locator maps were printed in black and white. A far cry from the color printing we are now accustomed to seeing when cracking open a brand new atlas today.

1996 (4th Edition): The first time we see color added to the contents and map locators in the Atlas. As advances in computer technology significantly changed the landscape of the world, the first eight digitally produced maps were included.

1997 (5th Edition): Hong Kong was returned to China’s sovereignty from the United Kingdom, and the update was reflected in the Atlas.

2000 (8th Edition): EROS A, a high resolution satellite with 1.9-1.2M resolution panchromatic was launched, and the first use of satellite imagery appears.

2001 (9th Edition): The bombing of Baghdad brings greater interest and awareness of the city to the world. It is included as one of the 67 maps of major cities around the world.

2002 (10th Edition): The split of Czechoslovakia is detailed, showing the breakdown of Czech and Slovak Republics more clearly.

2010 (17th Edition): As the world population swelled to over 6.5 billion, the worry about our ability to produce enough food to feed everyone was reflected in the six-page “Will The World Run Out of Food” section.

2012 (19th Edition): Figures from the 2010 US Census were used to update mapping. On 9 July 2011, South Sudan declared its independence, and the new country is shown for the first time in the Atlas.

2013 (20th Edition) With satellite imagery more widespread than ever, seven new satellite images of London, Amsterdam, Riyadh, Cairo, Vancouver, Sydney, Panama Canal, and Rio de Janeiro were added to the Atlas of the World.

The cover of the Atlas of the World has seen some interesting changes over the years too. Take a look at some past editions covers in the slideshow below, and let us know which one you think is the best.

Atlas of the World, 5th Edition

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Atlas of the World, 6th Edition

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Atlas of the World, 8th Edition

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Atlas of the World, 9th Edition

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Atlas of the World, 10th Edition

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Atlas of the World, 11th Edition

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Atlas of the World, 13th Edition

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Atlas of the World, Deluxe Edition

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Atlas of the World, 14th Edition

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Atlas of the World, 15th Edition

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Atlas of the World, 16th Edition

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Atlas of the World, 18th Edition

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Atlas of the World, 19th Edition

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Atlas of the World, 20th Edition

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Don’t forget to vote for what you think the Place of the Year should be. With your input, we’ll narrow the list down to a shortlist to be released on 4 November 2013. Following another round of voting from the public, and input from our committee of geographers and experts, the Place of the Year will be announced on 2 December 2013. In the meantime, check back weekly for more posts full of insights and explorations on geography, cartography, and the POTY contenders.

What should be Place of the Year 2013?

Moscow, RussiaSyriaTahrir Square, EgyptPyongyang, North KoreaCanada’s Tar SandsLake BaikalA Citibike StandRio de Janeiro, BrazilDemocratic Republic of the CongoColorado, USAThe NSA Data Center in UtahBoston, MABrooklyn, NYGreenland’s Grand CanyonDelhi, IndiaNorthern IrelandVenezuelaGrand Central TerminalThe United States Supreme CourtBenghazi, Libya

View Result

Total voters: 45Total votes: 57Moscow, Russia (3 votes, 5%)Syria (7 votes, 12%)Tahrir Square, Egypt (7 votes, 12%)Pyongyang, North Korea (1 votes, 2%)Canada’s Tar Sands (0 votes, 0%)Lake Baikal (1 votes, 2%)A Citibike Stand (2 votes, 4%)Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (4 votes, 7%)Democratic Republic of the Congo (2 votes, 4%)Colorado, USA (3 votes, 5%)The NSA Data Center in Utah (13 votes, 23%)Boston, MA (1 votes, 2%)Brooklyn, NY (1 votes, 2%)Greenland’s Grand Canyon (4 votes, 7%)Delhi, India (3 votes, 5%)Northern Ireland (2 votes, 4%)Venezuela (1 votes, 2%)Grand Central Terminal (0 votes, 0%)The United States Supreme Court (1 votes, 2%)Benghazi, Libya (1 votes, 0%)

Vote

Oxford’s Atlas of the World — the only world atlas updated annually, guaranteeing that users will find the most current geographic information — is the most authoritative resource on the market. The milestone Twentieth Edition is full of crisp, clear cartography of urban areas and virtually uninhabited landscapes around the globe, maps of cities and regions at carefully selected scales that give a striking view of the Earth’s surface, and the most up-to-date census information. The acclaimed resource is not only the best-selling volume of its size and price, but also the benchmark by which all other atlases are measured.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only geography articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Place of the Year: History of the Atlas appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPlace of the Year: Through the yearsAnnouncing the Place of the Year 2013 Longlist: Vote for your pickCookstoves and health in the developing world

Related StoriesPlace of the Year: Through the yearsAnnouncing the Place of the Year 2013 Longlist: Vote for your pickCookstoves and health in the developing world

‘And he laid down his hammer and he died’: Health and performance pay

The 19th Century African-American folk hero, John Henry, was said to be the best of all the steel-drivin’ men. According to some musical accounts of his life, he was bet that he could not beat a new steam powered hammer in a tunnelling contest. Henry won, but it cost him his life, as shown in a later line in the song, ‘And he laid down his hammer and he died’. The linkage between working ‘too hard’ and its consequences on health are clearly shown in the death of this legendary folk figure.

John Henry lies dead after beating the steam drill. Painting by Palmer Hayden. © Smithsonian American Art Museum

Interestingly, about 100 years earlier, in observing miners in his native Scotland, the 18th Century political economist, Adam Smith, wrote: ‘Workmen… when they are liberally paid by the piece, are very apt to overwork themselves and to ruin their health and constitution in a few years’ (An Inquiry into the Wealth of Nations, Smith 1776, p. 83). Thus, Smith too was identifying a linkage between health and a particular kind of payment contract – performance-based pay.What might generate such a relationship? Two linkages immediately come to mind. First, performance pay may give incentives to workers to take risks to produce as much as possible, thereby increasing chances of on-the-job injury. Second, people may work more hours in order to produce more, substituting away from time that could be spent on safeguarding health, e.g. working rather than going for exercise, eating take-away rather than cooking a healthy meal, etc.

Although Smith made this observation over 200 years ago, there is little economic research on this linkage and most has focused on the performance pay-injury link. For example, Keith Bender, Colin Green and John Heywood examine European data to find a strong link between piece rate payments and injury.

Our paper investigates the second link – the relationship between health and performance related pay. The study uses the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS) to identify workers who were in good health in 1998 and then follow their health over time to see if they report a worsening in their health, looking at differences in whether they are employed in jobs which have a performance pay element or not. We look at four different measures of health: a subjective evaluation of overall health and three objective measures – heart problems, stomach problems and anxiety or depression problems.

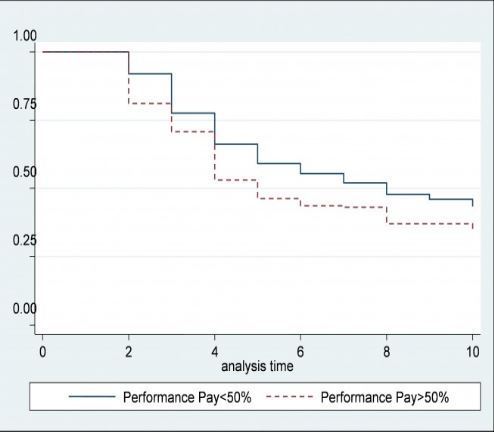

First, we examine graphs of how long it takes a worker to go from good to bad health (in the statistical literature, this is called a ‘survival plot’). The graph below shows how the percentage of workers who started off in good subjective health continue to be in good health each year after 1998. Unsurprisingly, that percentage falls over time. However, the interesting finding is that the percentage of the healthy falls more quickly for those who have spent more than 50% of their time in performance pay (the red, dashed line). The story is no different for the three objective measures of health – the heart, stomach and anxiety or depression measures all have lower probabilities the longer a worker is in performance pay.

Survival plots for the subjective health measure

Of course, there could be other factors that drive these results – differences in gender or industry or previous health, etc. So next, we statistically control for such factors and find that the odds to drop into poor health increase dramatically as the percentage of time spent in performance pay increases. For subjective health, the odds are nearly double for a worker with 50% of his/her time in performance pay compared to a worker with no performance pay. Furthermore, the odds for developing a heart problem is 3.5 times higher for workers with 50% of time spent in performance pay. The health measures for stomach problems and anxiety/depression show an increase in the odds by more than 2.5 times.

What might explain these differences? Evidence from the BHPS is limited, but we find that performance pay is correlated with a higher prevalence of eating out and drinking heavily, behaviours linked to health problems in the medical literature. A more direct linkage is through increased stress. For a series of stress measures (for example, problems sleeping, making decisions, feeling under strain, etc.) the longer one is in a job with performance pay, the more likely one is to experience increased stress.

Relative odds of bad health between a worker with no performance pay and a worker with 50% of time in performance pay

Thus, while performance pay may be linked to desirable economic outcomes like increased productivity, firms should be careful in implementing such payment systems and workers should be aware of the risks in taking jobs with these payment systems, as there may unintended health consequences of such jobs. Adam Smith was right after all!

Keith A. Bender and Ioannis Theodossiou are authors of ‘The Unintended Consequences of the Rat Race: The Detrimental Effects of Performance Pay on Health’, published in Oxford Economic Papers. Keith A. Bender is the SIRE Professor of Economics at the University of Aberdeen Department of Economics and Centre for European Labour Market Research (CELMR). His research examines labour market and heath interactions, as well as the labour market effects of educational mismatches. Ioannis Theodossiou is Professor of Economics in the University of Aberdeen Department of Economics and CELMR). His research focuses on issues related to the effect of socioeconomic conditions and unemployment on health and wellbeing outcomes, on the analysis of the unemployment problem and on issues related to pay determination.

Oxford Economic Papers is a general economics journal, publishing refereed papers in economic theory, applied economics, econometrics, economic development, economic history, and the history of economic thought.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) John Henry Lies Dead After Beating the Steam Drill, painting by Palmer Hayden, Smithsonian American Art Museum, via Wikimedia Commons; (2) and (3) Both graphs courtesy of the authors. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post ‘And he laid down his hammer and he died’: Health and performance pay appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe changing face of war [infographic]Getting parents involved in educationRiding the tails of the pink ribbon

Related StoriesThe changing face of war [infographic]Getting parents involved in educationRiding the tails of the pink ribbon

October 20, 2013

The changing face of war [infographic]

In a world of 9.1 billion people…

where 61% of the world’s population lives in urban centers…

primarily with coastal cities as magnets of growth…

and the people within these cities becoming ever more connected…

with mobile phones as tools for destruction…

All aspects of human society — including, but not limited to, conflict, crime, and violence — are changing at an unprecedented pace. In Out of the Mountains The Coming Age of the Urban Guerrilla, counterinsurgency expert David Kilcullen argues that conflict is increasingly likely to occur in sprawling coastal cities, in peri-urban slum settlements that are enveloping many regions of the Middle East, Africa, Latin America and Asia, and in highly connected, electronically networked settings. Illustrated in the infographic below are four powerful megatrends — population, urbanization, coastal settlement, and connectedness — which are creating challenges and opportunities across the planet for future cities and future conflicts.

Download a jpg of the infographic.

David Kilcullen is the author of the highly acclaimed Out of the Mountains: The Coming Age of the Urban Guerrilla, The Accidental Guerrilla, and Counterinsurgency. A former soldier and diplomat, he served as a senior advisor to both General David H. Petraeus and Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. In recent years he has focused on fieldwork to support aid agencies, non-government organizations and local communities in conflict and disaster-affected regions, and on developing new ways to think about complex conflicts in highly networked urban environments.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The changing face of war [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAnother kind of government shutdownRiots, meaning, and social phenomenaCookstoves and health in the developing world

Related StoriesAnother kind of government shutdownRiots, meaning, and social phenomenaCookstoves and health in the developing world

Medical research ethics: more than abuse prevention?

Scholarly and regulatory attention to the ethics of medical research on human subjects has been one-sidedly focused on the prevention of moral disasters. Scandals such the US Public Health Service (PHS)’s Tuskegee syphilis experiments, which for decades observed the effects of untreated syphilis on the participants, most of whom were poor black sharecroppers, rightly spurred the broad establishment of a regulatory regime that emphasized the importance of preventing such severe harming and exploitation of the human subjects of research. Revelations in 2011 about a similarly horrific set of studies conducted by the PHS from 1946 to 1948 on sexually transmitted diseases has renewed this kind of concern, which has been strongly underlined in a recent report by the Presidential Commission for the Study of Ethical Issues. The regulations motivated by such abuses have established a two-pronged set of institutional protections well designed to make a recurrence of such horrors unlikely: (1) all plans (“protocols”) for research involving human subjects must be approved by “Institutional Review Boards” (United States) or “Research Ethics Committees” (elsewhere), and (2) ordinary consent to participate will not suffice; instead, subjects may be enrolled only if they give their “informed consent.”

Important as this concern is and as valuable as these institutionalized responses are, they dominate thinking about the ethics of medical research so much that the result is unbalanced. In particular, the “helping people” side of morality, which philosophers label with the word “beneficence,” has been left undeveloped. The principles articulated in the Belmont Report, published in 1979 in response to the Tuskegee scandal by the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, included beneficence, alongside respect for persons and justice, as one of its three guiding principles. In practice, however, the aspect of beneficence that has seen the fullest development, in this area, is that of non-maleficence — not hurting people — which many consider a principle distinct from that of beneficence.

Important as this concern is and as valuable as these institutionalized responses are, they dominate thinking about the ethics of medical research so much that the result is unbalanced. In particular, the “helping people” side of morality, which philosophers label with the word “beneficence,” has been left undeveloped. The principles articulated in the Belmont Report, published in 1979 in response to the Tuskegee scandal by the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, included beneficence, alongside respect for persons and justice, as one of its three guiding principles. In practice, however, the aspect of beneficence that has seen the fullest development, in this area, is that of non-maleficence — not hurting people — which many consider a principle distinct from that of beneficence.

This complaint of one-sidedness would be empty if there were not important ethical challenges for medical research involving human subject that arise from beneficence. Central among such challenges is the issue of researchers’ obligations to provide “ancillary care” — medical care that their research subjects need but that is not necessary to conducting worthwhile and sound research in a safe manner. The issue of ancillary care is important in all contexts of medical research, from research on neglected diseases in developing countries to the most advanced, high-tech medical research on genetics or imaging technologies at tertiary hospitals in the developed world. A researcher studying extremely drug-resistant tuberculosis in southern Africa may discover that one of her participants is HIV-positive. Does this researcher have any moral responsibility to help with this person’s HIV care? A genetics researcher working with banked DNA samples may discover a genetic anomaly that poses a dangerous threat that might be averted by clinical treatment. Does this researcher have any moral responsibility to communicate these results to a donor he has never met?

The medical research ethics community has been slow to recognize the challenge posed by the ancillary care issue, no doubt due in large part to that community’s focus on the prevention of moral disasters. The so-called “standard of care” debate regarding medical research in developing countries burst onto the scene with an article and an accompanying editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1997. At issue was whether it was ethical to give only placebos to those in the control arms of studies in Africa intended to determine the effectiveness of shorter administrations of the drug AZT in controlling the transmission of HIV from mother to fetus, despite the fact that the effectiveness of longer, carefully monitored administrations of that same drug had already been proven effective. One would not do that in the United States, so how can it be acceptable to do that in Africa? This important issue lies at the cusp between beneficence and non-maleficence. Using the longer AZT treatment for the controls would have helped them. Yet the thinking about this issue did not break out of the non-maleficence box, for the dominant reasoning seems to be that since participation in medical research unavoidably involves some risk, it is morally wrong to subject people to that risk unless there is a sound scientific reason for it. Where it is already known that a treatment is effective, some special argument would have to be made to explain why one should compare the new, proposed treatment to placebo rather than to the proven treatment.

The standard-of-care debate rages on, addressing these and other complexities pertaining to the kind of care medical researchers owe to their subjects for the disease or condition under study. The ancillary care issue, by contrast, concerns questions about what medical care researchers may owe to their subjects for other medical needs that may arise during a study. Sometimes, clinical physicians enroll their own patients in research studies. In those cases, they owe these people a doctor’s full panoply of duties towards their patients — which may sometimes awkwardly conflict with these doctors’ obligations as researchers. If we confine our attention to medical researchers who enroll subjects who are not (otherwise) their patients, however, we might wonder why they owe them any special help. The enrollment transaction is not merely a consenting one, but one held to a much higher standard than is buying a car or signing up for a white-water rafting trip. Why can’t medical researchers just stipulate how much care they propose to provide for their subjects’ ancillary needs? In developing country settings, it is likely that the research team is automatically providing their subjects more clinical services than are usually available to them. Why think that the researchers might be specially obligated to do any more than that?

To answer these questions, one needs to understand how medical researchers become morally entangled with the lives and needs of their research subjects.

Henry S. Richardson is a Professor of Philosophy, Georgetown University. He is the author of Moral Entanglements: The Ancillary-Care Obligations of Medical Researchers and Democratic Autonomy. His next article for the OUPblog on how medical researchers become morally entangled will appear next week.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Laboratory technicians at work in medical plant with machinery and computers. © diego_cervo via iStockphoto.

The post Medical research ethics: more than abuse prevention? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat patients really wantCookstoves and health in the developing worldCelebrating World Anaesthesia Day

Related StoriesWhat patients really wantCookstoves and health in the developing worldCelebrating World Anaesthesia Day

Does time pass?

In the early 5th century BCE a group of philosophers from the Greek colony of Elea formed a school of thought devoted to the notion that sense perception — as opposed to reason — is a poor guide to reality. The leader of this school was known as Parmenides. He left behind scraps of a long prose poem about the true nature of time and change. This work, On Nature, is one of the earliest surviving examples of philosophical argumentation.

Our perception of the world is of a world of change, of motion and transience. Parmenides was convinced that the reality is quite different. He argued as follows. The ordinary notion of change indicates some thing or state of a thing going from being future to being present to being past. Yet we also ordinarily contrast the what is — i.e., the present state of things — with the what is not — i.e., the merely possible or long gone. The future doesn’t actually exist; if it did, then it would exist now! But then nothing can go from actually being future to being present: if the future is not real, then the present state of things cannot come to be from a future state of things. Hence, change is impossible and illusory. Parmenides concluded that the world is really a timeless, static unity. The terms ‘past,’ ‘present,’ ‘future’ do not designate intrinsic properties of things or events.

It would be difficult to come up with a proposition that meets with any less agreement in our everyday experience. How can we even imagine a world without the passage of time? The lived experience of the flow of a river, the enjoyment of a melody, and the decisions we make from moment to moment that depend on what we think is happening now — and what might be coming up — all speak irresistibly in favor of change. Parmenides must have gone wrong somewhere!

Running by Nevit Dilmen, 2006. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

And yet the vision of a static universe, with no intrinsic past, present, or future, finds powerful validation in Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity. According to that well-confirmed theory, two events that are simultaneous to an observer in one inertial reference frame will not be to a different observer moving relative to the first one. Since there is no absolute motion, there is no privileged vantage point that fixes which events are really simultaneous and which are not. This means that the set of events ‘present’ to one observer is different from another’s set; neither is justified in identifying a particular moment that everyone should agree is the present moment. The same goes for pastness and futurity: an event one observer considers past may be present, or even future, for another, depending on its relative distance and their relative velocity. If there is no privileged vantage point from which to determine the ‘truth’ of the matter — and the whole point of relativity is that there is not — then temporal properties like past, present, and future cannot possibly be aspects of reality. They must be subjective and perspectival in nature.

Of all things, whether a loved one’s death occurs in the past or in the future carries immense significance to us. Yet Einstein insists otherwise in a famous letter eulogizing his friend Michele Besso:

Now Besso has departed from this strange world a little ahead of me. That means nothing. People like us, who believe in physics, know that the distinction between past, present, and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.

We know that the designation ‘here’ is purely perspectival: my ‘here’ may be your ‘there,’ and vice-versa. From the universe’s perspective, the designation ‘now’ is no more an objective designation than ‘here.’ (Think what odd consequences follow from treating designations like ‘past’ as real properties of objects and events. This would entail, for example, that something even now is happening to the Battle of Waterloo: it is becoming more past.)

No doubt our biology requires us to think differently. We have evolved as conscious beings who act on the basis of beliefs. Agency requires us to think in terms of what has been accomplished and what is to be done next. Beings like us must think in terms of “now is the time to feed / fight / escape / go to the department meeting.” Even though no moment is privileged, at any given moment we are convinced by our experience, and by that moment’s memories and anticipations, that the time is now. Consciousness of change and the passage of time is irreducible, inescapable. There is no guarantee, however, that even biologically necessary representations of the world speak the truth of the world as it is in itself.

Adrian Bardon is Associate Professor of Philosophy at Wake Forest University. He is the author of A Brief History of the Philosophy of Time.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Does time pass? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesJonathan Swift, Irish writerRomeo & Juliet: the film adaptationsWhy is Gandhi relevant to the problem of violence against Indian women?

Related StoriesJonathan Swift, Irish writerRomeo & Juliet: the film adaptationsWhy is Gandhi relevant to the problem of violence against Indian women?

October 19, 2013

The wait is now over

Let’s get one thing straight about Andy Murray’s Wimbledon singles title: It was not the first one by a Briton in 77 years, despite what the boisterous headlines might have you believe. London’s venerable Times set the tone on 8 July 2013 with its proclamation, “Murray ends 77-year wait for British win.” Not true. The Daily Mail‘s headline was longer, but not any more accurate: “Andy Murray ends 77 years of waiting for a British champion.” And The Telegraph simply heaved a sigh of relief: “After 77 years, the wait is over.” The vagueness of that statement at least grants the editors a degree of plausible deniability. If they meant that Britain had waited 77 years for one of their male players to capture the singles title, then they would at least have accuracy on their side, even if the tenor of the headline suggested a high degree of chauvinism in its willful downplaying of the four – not one, but four — Wimbledon singles titles by British women in those intervening 77 years since a British man, Fred Perry, had won a singles title in 1936.

Andy Murray celebrates after winning Wimbledon in July 2013. Photograph by Robbie Dale. CC 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Don’t get me wrong. I don’t want the British press to downplay Andy Murray’s success, but can’t they simultaneously play up the successes of their female players? Virginia Wade was, in fact, the last Briton to win a Wimbledon singles title, doing so in 1977, and three other British women have won Wimbledon since Perry’s title — Ann Haydon-Jones and Angela Mortimer, in the 1960s, and Dorothy Round Little, in 1937. As the Guardian pointed out, an acknowledgment of Little’s win would have the effect of whittling Britain’s “wait” for another singles title after Perry’s from seventy-seven years down to just one.

Jaded fans of women’s sports might simply roll their eyes at this willful oversight on the part of the British press and ask in exasperation, “What else is new?” Haven’t female athletes always competed in the shadow of their male counterparts, struggling for any scrap of attention that the sports media might throw their way?

Well, no. In fact, as a look at the German press in the years just before the Nazis came to power shows, sportswomen often garnered as much attention as the men and sometimes even a tiny bit more. The 1931 Wimbledon tournament provides a good case in point. Female players had been drawing attention to themselves throughout the two weeks of play that summer, both for their tennis and for their attire. A British player that year became the first woman to play on center court with bare legs, for example, and a Spanish player raised even more eyebrows for donning skirt that looked a lot like a pair of men’s short pants. The media devoted even more attention to that year’s final, which, for the first time ever, pitted two Germans against one another for the championship: Cilly Aussem and Hilde Krahwinkel.

Cilly Aussem, March 1930. Photographer unknown, from German National Archives. CC 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Even stiffer than the competition that those two women faced from one another for the championship title, though, was the competition that they faced for the attention of the sporting public back home in Germany. After all, at the same time that Aussem and Krahwinkel were facing off in the London suburb on that July day, a traditionally much higher profile men’s sporting event was taking place in Cleveland, Ohio: the men’s world heavyweight title bout between Max Schmeling — the defending champion and first German to claim that honor — and Young Stribling, his American challenger.

As far as the athletic competitions themselves went, it was a double victory for Germany, with Aussem beating Krahwinkel and Schmeling delivering a 15th-round TKO to Stribling. But who won the competition for the hearts and souls of the German public? Cilly Aussem did, at least according to many commentators and headline writers. One arch-conservative (and unmistakably chauvinist) columnist, who wrote under the pseudonym “Rumpelstilzchen,” for instance, gave Schmeling’s success second billing, mentioning it only parenthetically and only after first trumpeting the remarkable achievements of the German women. ”The Englishmen’s eyes nearly popped out of their heads,” the columnist gloated, when they realized that Germans occupied both spots in the finals match, and, Rumpelstilzchen added, the women proved that Germany’s “will to live has not been extinguished.” Their athletic achievements, and not Schmeling’s, he clearly insisted, had restored German pride.

Why did Aussem get so much attention? She was young and very pretty, for one thing, but Schmeling also enjoyed heart-throb in the Weimar Republic. Germany’s recent military defeat — and partial British occupation — also helps to explain the particular glee over an all-German final in one of the most English of all sporting events. The shifting gender constellation in interwar Germany, though, also played a role, creating an environment in which — at least for brief times and in certain contexts — women’s achievements received as much attention as men’s. The fact that contemporary sports coverage still often overlooks women’s accomplishments only shows that those changes initiated in the 1920s and early 1930s have not become permanent. In that regard, the wait is definitely not over.

Erik N. Jensen is Associate Professor of History at Miami University, Oxford, Ohio. He is the author of Body by Weimar: Athletes, Gender, and German Modernity.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only sports articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The wait is now over appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWimbledon, Shakespeare, and strawberriesOh, I say! Brits win WimbledonIvor Gurney and the poetry of the First World War

Related StoriesWimbledon, Shakespeare, and strawberriesOh, I say! Brits win WimbledonIvor Gurney and the poetry of the First World War

Bloody but unbowed

Not much remains to be said about the politics of the written word: scores of historical biographers have examined the literary appetites of revolutionaries, and how what they read determined how they interpreted the world.

Mohandas Gandhi read Henry David Thoreau’s Civil Disobedience during his two-month incarceration in South Africa. Martin Luther King, Jr. read W.E.B. Du Bois’ The Souls of Black Folk from the confines of his Birmingham cell. Liu Xiaobo, a jailed Nobel Peace laureate serving an 11-year sentence for subversion, reportedly read Christian philosophical texts and a popular nonfiction book about the history of Soviet Communism and Russian intellectuals.

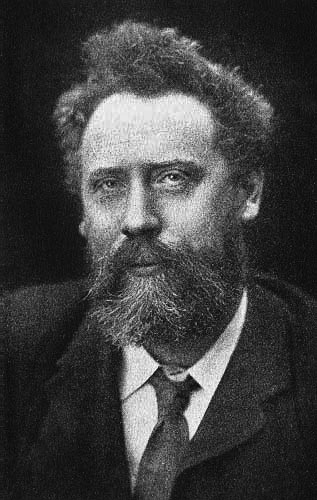

Of these, Nelson Mandela’s recitation of William Ernest Henley’s “Invictus” during his imprisonment on Robben Island is perhaps most memorable, inspiring generations of jailed activists and an eponymously-titled Hollywood adaptation starring Morgan Freeman and Matt Damon. Indeed, the poem — penned by a tuberculosis-stricken Henley in 1888 — has become something of an intellectual heirloom for activists beating back the tides of institutionalized oppression. Even the widely-used idiomatic expression, “bloody but unbowed,” owes its etymological origins to Henley’s poetic masterpiece, which spans just four stanzas.

Not bad for an originally untitled Victorian-era poem, and one with apolitical beginnings at that. Henley’s poem, first published in Echoes of Life and Death, was only inscribed with the dedication “To R.T.H.B.” (a reference to literary patron Robert Thomas Hamilton Bruce) before being posthumously titled “Invictus” by Arthur Quiller-Couch, an editor of The Oxford Book of English Verse. But how, exactly, did “Invictus” make the leap from the pages of obscurity to the halls of poetic fame? And how did a written work inspired by Henley’s private experiences garner so much public resonance?

Not bad for an originally untitled Victorian-era poem, and one with apolitical beginnings at that. Henley’s poem, first published in Echoes of Life and Death, was only inscribed with the dedication “To R.T.H.B.” (a reference to literary patron Robert Thomas Hamilton Bruce) before being posthumously titled “Invictus” by Arthur Quiller-Couch, an editor of The Oxford Book of English Verse. But how, exactly, did “Invictus” make the leap from the pages of obscurity to the halls of poetic fame? And how did a written work inspired by Henley’s private experiences garner so much public resonance?

After all, “Invictus” isn’t a political poem in the usual sense: it’s meditative rather than militant, assuming the quietness of a prayer rather than the pomp and circumstance of a battle cry. Even more remarkable is the sense that its rhymed quatrains comprise much more than an effortless execution of form, conveying a host of revolutionary philosophical implications. In particular, the lines “I am the master of my fate / I am the captain of my soul,” remind us of Henley’s outspoken — and highly controversial — atheism, which remain a source of individual empowerment in a “place of wrath and tears.” Likewise, “whatever gods may be” are rendered obsolete by the poem’s progressive notions of self-determinism, in what should be interpreted as the triumph of human resilience unaided by divine benevolence.

Henley avoids the usual discourse on order and disorder, instead finding an exhilarating freedom in the absence of divine control, not to mention the kind of empowerment one might expect to derive from godlessness. Fate, in this case remains undecided rather than assigned, a series of events governed by free will and its lifelong struggle against the “fell clutch of circumstance.” Henley’s frightening, if awe-inspiring, revelation that no one can or will write our destiny for us explains “Invictus’” unrivaled popularity in political circles — for how else should political activists understand themselves if not as writers of their own history? No wonder innumerable modern revolutionaries, including Burmese opposition leader and Nobel Peace laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, have cited Henley’s 19th century poem as a “great unifier than knows no frontiers of space or time,” a heartfelt iteration of “struggle and suffering, the bloody unbowed head, and even death, all for the sake of freedom.”

The life of a poem is a strange one, such that an originally untitled, four-stanza work might recover itself from the depths of obscurity to become one of the greatest declarations of political martyrdom. William Ernest Henley’s “Invictus” does not necessarily ask us to remember who its author was, and why he wrote what he did, so many years ago — only that he stood “bloody but unbowed,” and that his unconquerable spirit is also our own.

Sonia Tsuruoka is a social media intern at Oxford University Press, and an undergraduate at Johns Hopkins University. Her writing has appeared in a variety of publications, including Slate Magazine and the JHU News-Letter.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: William Ernest Henley. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Bloody but unbowed appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesJonathan Swift, Irish writerSolomon Northup’s 12 Years a Slave, slave narratives, and the American publicRomeo & Juliet: the film adaptations

Related StoriesJonathan Swift, Irish writerSolomon Northup’s 12 Years a Slave, slave narratives, and the American publicRomeo & Juliet: the film adaptations

Jonathan Swift, Irish writer

By Claude Rawson

Jonathan Swift, whom T. S. Eliot called “colossal,” “the greatest writer of English prose, and the greatest man who has ever written great English prose,” died on 19 October 1745. Every year on a Saturday near that day, a gathering of admirers meet for a symposium in his honour, in the Deanery of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin, where Swift lived and worked for the last thirty years of his life. The event is hosted by Swift’s present-day successor as Dean of the Cathedral, and is followed on Sunday by a lay sermon by a well-known Irish person, a distinguished writer, for example, like the novelist Anne Enright, or, more recently in 2012, the President of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins.

This great English writer, dean of an Anglican church in a Roman Catholic country, who regarded Ireland as a place of exile, is nowadays honoured as one of the political as well as literary giants of Irish history. When the three hundredth anniversary of his birth was commemorated in Dublin in 1967, an earlier President, Eamon de Valera, gave the opening address, accompanied by several members of the government. In no other English-speaking country is it usual for a writer to be officially honoured at the highest political level, by national leaders who in addition give every indication of having read his works. Swift is also a hero of the streets, even to people who haven’t read him. Dublin taxi-drivers who ask you what brings you to the city give you brownie points if you say you are working on Swift. “Oh Swift, that’s great, Swift is great. He’s the one who drove the English out.” Well, he wasn’t. He wanted the English in Dublin to be rid of the English from London, and he didn’t much like the Irish natives, but as de Valera (an old revolutionary fighter) understood, Swift knew that the essential thing was first to get London out of Irish affairs.

Gulliver in Brobdingnag by Richard Redgraven

But there is more. Ireland honours its writers, including the Protestant writers, more naturally and profoundly than England or the United States. Both Yeats and Shaw were invited to serve in the Irish Senate at its inception. Shaw said he would only come if the Senate moved to London, but Yeats became a distinguished Senator, of admired wisdom and eloquence. “We are the people of Swift,” he said of the heroes of the Protestant Ascendancy, “one of the great stocks of Europe.” He was responding to Catholic senators who objected to a Protestant speaking in favour of divorce. They did not vote for divorce, but beyond the most passionate partisanship, there is a natural feeling throughout Irish society, percolating down to the unlettered street, that literature matters, and that their writers, whether English or not, are national treasures. My taxi-driver, who took it for granted that “Swift was great,” asked me, “if there was one book by Swift he should read, what would it be?” When I suggested Gulliver’s Travels, he exclaimed, “Did he write Gulliver’s Travels?” The name alone of the great Swift had hitherto been enough.Gulliver’s Travels is an Irish book, and not flattering, either to the Irish or to anyone else. The humanoid Yahoos of Part IV are based on a common view of the Irish natives, and the name has subsequently been used as a synonym for them. The Yahoos are given features “common to all savage Nations,” including, improbably, thick lips, flat noses, and hairy bodies, which were stereotypes of the imperial imagination. This is not, despite appearances, an expression of vulgar “racism,” even allowing for the fact that conceptions of racial difference, and superiority, though not edifying, were less charged with the kind of exacerbated malignity that would be assumed in our own political climate. Swift’s position about despised or pariah groups differs from most others, however, is that he is not saying “we” are better than “them,” but that they are indeed as bad as they are described to be, while “we” are exactly like them. The features of the despised race are baldly confronted, and then reappraised as common to humanity, with an additional sting to the effect that we, their civilized or Christian betters, are if anything worse, not better. The conquest of American Indians is described in the final chapter as more barbaric than the Indians themselves, but the book as a whole gives us little reason to think well of the latter. The Yahoos, “all savage Nations,” are in fact not Irish but, like the Irish and “us,” merely human.

The message is bleak, but it is not “racist.” Unsurprisingly, some readers have shrunk from it, especially in the benignly conformist climate of university literature departments, which prefer their authors to be sanitized to the prevailing idea of political virtue. Swift did not write to be liked, however, and non-academic readers, exemplified by Thackeray in a famous essay, who found Gulliver’s Travels disturbing or even unbearable were closer to Swift than readers who welcome it as a tolerant and broadminded fable written by a Guardian or New York Times columnist. Neither shocked indignation, nor complacent approval, does justice to a great masterpiece, which subjects humanity to a raw exposure of its degraded animal bleakness. T. S. Eliot got it right, as so often, when he said he considered Gulliver’s Travels, “with King Lear as one of the most tragic things ever written.”

Claude Rawson is Maynard Mack Professor of English at Yale University. He is the author of several books on Swift, Fielding and other eighteenth-century authors, and of numerous articles and reviews both in specialist journals and in the Times Literary Supplement, New York Times Book Review and London Review of Books. He has edited Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift for Oxford World’s Classics.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Illustration from Gulliver’s Travels, by Richard Redgraven [public domain]. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Jonathan Swift, Irish writer appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRomeo & Juliet: the film adaptationsMary Hays and the “triumph of affection”Why is Gandhi relevant to the problem of violence against Indian women?

Related StoriesRomeo & Juliet: the film adaptationsMary Hays and the “triumph of affection”Why is Gandhi relevant to the problem of violence against Indian women?

October 18, 2013

Solomon Northup’s 12 Years a Slave, slave narratives, and the American public

Like many scholars who study nineteenth century African American history and literature, I am excited by the attention surrounding the newly released film, 12 Years a Slave, based on the experiences of Solomon Northup, a free black man from New York who was kidnapped in 1841 and sold into slavery. Northup’s memoir of those experiences, published in 1853, forms the basis of the film.

Slave narratives—the literary genre of which Northup’s story is a part—generated plenty of attention in the decades before the civil war, with scores of published narratives selling tens of thousands of copies. The narratives exposed the horrors of American bondage through the personal stories of those who experienced those horrors first hand. Proslavery advocates, however, condemned them as fabrications that distorted what southerners claimed was a benign institution in which slaves were well cared for and content. Many others in a profoundly racist American society were skeptical of blacks’ abilities to put such compelling stories on the printed page. Such skepticism has persisted, in one form or another, among scholars studying the narratives in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. While some slave narrators had limited literacy and relied on white abolitionists to convert their tales to print, a half century of intensive research has convinced most literary and historical scholars today of the general accuracy and authority of their stories.

A recent New York Times article on the film, however, revives some of those troubling questions about slave narratives in general, and Northup’s story in particular—questions that relate to the stories’ accuracy and authenticity. I find it interesting that, in questioning Northup’s veracity, Times writer Michael Cieply relies on scholarly essays published almost thirty years ago. That Cieply zeroed in on those rather dated essays—and not any of the more recent scholarship on the narratives and Northup—seems rather odd. Perhaps Cieply encountered those essays in the summary of Northup’s narrative on the Documenting the American South website. Both essays appear in the 1985 collection, The Slave’s Narrative, edited by Henry Louis Gates and Charles T. Davis.

While there may be legitimate questions about a slave narrative’s accuracy based on the vicissitudes of memory or a narrator’s desire to promote the abolitionist cause, James Olney’s 1985 interpretations regarding Solomon Northup are wildly speculative and rooted primarily in Olney’s assertion that slave narratives were driven more by the desire to fit into popular narrative conventions than by the desire to convey one’s actual experiences.

Chiwetel Ejiofor in 12 Years a Slave. (c) Fox Searchlight. Source: 12yearsaslave.com

Olney argues that slave narrators’ memories of the events of their lives are largely irrelevant, since they are “most often a non-memorial description fitted to a pre-formed mold.” Olney is correct in pointing out the formulaic character of many antebellum narratives and their unapologetic use as propaganda to further the abolitionist cause. More recently, Ann Fabian has observed that nineteenth-century autobiographers, in general, tended to craft their memories into narrative frameworks that would be readily recognized by the reading public. Yet for Olney to dismiss the memories and authorial voices of former slaves—basically accusing them of making stuff up—goes too far.

Cieply’s Times article also cites an essay from the same 1985 volume by Robert Burns Stepto, but he misappropriates Stepto’s point. While Stepto noted Northup’s concern that some readers might not accept the accuracy of his tale, that hardly constitutes evidence that the tale was not true. In fact, later in the Times piece we learn that recent research has uncovered evidence corroborating some of the specific details in 12 Years a Slave.

While slave narratives served as abolitionist propaganda, they also represent one of the earliest and most profound genres of African American literary expression. The process of recalling and setting down one’s life story must have been cathartic for those who had endured slavery and its torments. Surely many former slaves desired never again to revisit that part of their lives. But many who did record their narratives were empowered by their ability to speak their truths and impose narrative control over the experience of their enslavement and liberation. Jennifer Fleischner argues that slave narratives are imbued not only with the “narrators’ insistence that the stories they tell about their slave pasts are true,” but also that “the violent theft of their memories—of their own selves, and of themselves by others—lay at the sick heart of slavery.”

No author’s use of autobiography has been more powerful than that of the early slave narrators. Gates and Davis rightly observed that Western thinkers like Hume, Kant, Jefferson, and Hegel all viewed literary capacity and a sense of collective history and heritage as central to any people’s claims to humanity. Gates and Davis succinctly capture this argument’s logic: “Without writing, there could be no repeatable sign of the workings of reason, of mind; without memory or mind, there could exist no history; without history, there could exist no humanity.” Aside from any other motivations, African American autobiographers’ writings implicitly refuted the notion that blacks lacked those fundamental human characteristics. The indisputable black voices at the heart of their stories, their insistence on embracing their memories, and the collective thematic unities among their narratives established not merely a black literary tradition, but also demonstrated the race’s humanity and intellectual capacity.

One can only hope that the release of 12 Years a Slave will generate interest in Northup’s story among the broader reading public, and will draw more attention to the study of nineteenth century African American literature, and the ongoing and pervasive influence of African American people on American history and culture. If the movie does well at the box office, perhaps we can look forward to more of these powerful American stories reaching the mass audiences they deserve.

Mitch Kachun is Professor and Director of Graduate Studies in the History department at Western Michigan University. He is author of Festivals of Freedom: Memory and Meaning in African American Emancipation Celebrations, 1808-1915 (Massachusetts 2003); co-editor of The Curse of Caste; or, the Slave Bride, a Rediscovered African American Novel by Julia C. Collins (Oxford 2006); and currently completing a manuscript for Oxford, tentatively titled First Martyr of Liberty: Crispus Attucks in American Memory.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to lonly literature articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only television and film articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Solomon Northup’s 12 Years a Slave, slave narratives, and the American public appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRomeo & Juliet: the film adaptationsCookstoves and health in the developing worldChildren’s invented notions of rhythms

Related StoriesRomeo & Juliet: the film adaptationsCookstoves and health in the developing worldChildren’s invented notions of rhythms

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers