Oxford University Press's Blog, page 884

November 6, 2013

Amazing!

Words, as I have noted more than once, live up to their sense. For instance, in searching for the origin of amaze, one encounters numerous truly amazing reefs. This is the story. Old English had the verb amasian “confuse, surprise.” Next to it, amarod (“confused”), the past participle of the unattested verb amarian existed. Both forms were rare, a circumstance that may perhaps bear out my final conclusion. In the entries on amaze, dictionaries of Modern English do not mention amarian, because, as I think, they have nothing to say about it and also because it has left no traces in the present day language. According to a well-known rule (Verner’s Law), s and r in Germanic alternated, depending on the place of stress in the protoform. If stress fell on the root, s was preserved, but, if it fell on the suffix or ending, s turned to z and later to r. Sometimes the “law” worked capriciously. For example, raise, a borrowing from Scandinavian, obviously had stress on the root (the modern pronunciation with z at the end is comparatively recent), while its native doublet rear must have been stressed on the suffix, no longer extant. Just why this happened remains unclear, but at the moment we are interested in the results, not in the mechanism of the change.

Similar alternations (s ~ r) sometimes occur in the forms of the same language, and I wonder whether the ancient verb amasian could sometimes have initial and sometimes “delayed” stress, obedient to the rules of intonation. Compare the situation in Modern English. Some people say ’fifteen rooms but Room fif’teen. Other than that, sentence stress fluctuates regularly: ’long a’go (both words are stressed), but ’ten ’years ago; we say ’Tennessee ’Williams but the ‘State of Tenne’see. I notice that the title of Thackeray’s novel has two stresses (‘Vanity ‘Fair), while the title of the magazine has one (‘Vanity Fair). Naturally, this is only a tendency. American speakers usually pronounce fifteen with initial stress in all situations, while some British speakers tend to distinguish between ‘fifteen and fif’teen. If my guess is right, there is no need to look for the etymology of Old Engl. amarod different from that of amasian. This hypothesis looks mildly attractive, but, as we will see, there is a stiff price to pay for it.

We now have to ask whether the second a in amasian was long or short. Old scholars preferred to look on it as long. Since long a in Old English had only one source, namely the diphthong ai (to which ei corresponded in German and Scandinavian), they cited as possible cognates Old High German meis “a basked carried on the back” and even German Meise “titmouse” (in Engl. titmouse, -mouse is the product of folk etymology: the titmouse is not a rodent, despite the ridiculous modern plural titmice), along with several ghost words. But amazement has nothing to do with birds or baskets, so that we probably have to reconstruct short a in amasian. And here we are lost: the spoor becomes cold. Skeat and Murray’s OED listed numerous Scandinavian nouns and verbs that begin with mas-. The OED online does the same. No one knows what to do with them.

An especially long list can be found in the old and excellent Norwegian etymological dictionary by Falk and Torp. Thus, we have Norw. mase “strive; bustle; beg; crush” (among other glosses, “lose consciousness” and “become delirious” turn up, but neither sense seems to be common). The dialectal and archaic noun mas means “whim; idle chatter.” Already here we begin to sense trouble: “strive” and “bustle” refer to a hectic effort, while “lose consciousness” presupposes listlessness. In Swedish, masa means “walk slowly, dawdle” and, in Norwegian, “warm (oneself).” At first sight, the two meanings have nothing in common. Quite a few related verbs refer to warmth, being drunk, and pleasant sensations, but “walk slowly” can be connected, if at all, only with “lose consciousness.”

It is the incompatibility of multiple meanings (striving and idleness, with warmth and intoxication thrown in for good measure) that baffles students of amaze and its look-alikes. In the nineteenth century, the greatest reward for an etymologist’s investigation was the ability to reconstruct the protoroot from which all the existing forms could be shown to have sprouted. In the first edition of his dictionary (under maze ~ amaze), Skeat set up the root MA “to think.” It is no wonder that he soon gave it up. Falk and Torp preferred the root MA “crush to dust.” Given enough ingenuity, one can derive any meaning from any other. “Crush” is better than “think,” for he who is “crushed” will occasionally lose control of his senses. Conversely, crushing may lead to bustling and striving. Today such exercises arouse subdued inspiration.

I would not have launched on the discussion of these intractable words if some time ago I had not come across a similar case, and also in Scandinavian. The root dras, perhaps known to some from the name of the mythological world tree Yggdrasill, has the same vowel variations as in mas and enters into the words meaning “rubbish; very big and heavy thing; pull with an effort; lazy; blunt; walk slowly, loaf; idle talk; indulge in debauchery.” (Drasill means “horse,” and it must have referred to a restive or uncontrollable horse.) Some of the senses are the same as in the mas- words. I would like to suggest that at least in the Scandinavian area rhyming slang words—dras and mas (and possibly more like them)—existed, none of which went back to a “respectable” Indo-European base. They seem to have had a broad and vague range of meanings, something like “impetuosity; willfulness; lack of predictability and direction” and could refer to about anything from working hard (and achieving nothing), loitering, lounging, and plodding aimlessly along to spending time with boon companions and lying in the sun. Old Engl. amasian would then end up as a borrowing from Scandinavian, because in English a comparable semantic network is absent.

Now the time has come to remember the stiff price mentioned at the beginning of this essay. Verner’s Law functioned very long ago, and if Old Engl. amasian and amarod are related by this law, they must have been current in English before the Germanic tribes settled in Britain. But I could not find similar words in Old Saxon, Low German, or Dutch. This weakens but does not derail my idea that amasian and amarod are related. Regardless of our conclusion, amasian, though lacking native siblings, and the numerous Scandinavian words appear to be congeners. Consequently, the isolation (within West Germanic) of at least amasian has to be accepted as an incontestable fact. But I would be happier if amarod did not exist! Since the participle means “confused,” my frustration deserves some sympathy. (“It is not customary to regret the existence of linguistic phenomena,” an unimaginative but solid professor wrote in a comment on my undergraduate paper.) However shaky my reasoning may be, I think that I am probably right in characterizing amaze as an example of old, perhaps even very old, slang, with analogs outside English.

A single note has to be added to what has been said above. When we see a word like aslant or askew, we assume that they are slant and skew, with the prefix a- being added to the root. Even askance and agog (about both of which I have written in this blog) must be a- plus some enigmatic skance and gog. But as far as we can judge, the English noun maze was abstracted from the verb amaze, rather than being its original stem. Maze denoted a place of utter confusion, which proves that amaze came into being with the sense “confuse, perplex” rather than “surprise.” The broad concept of surprise develops from various situations. For example, the inner form of sur-prise is over-take. Perhaps I will be able to return to this theme in the not too distant future.

Although maze is not the same as labyrinth, the distinction will be disregarded here. See the Minotaur trapped in the labyrinth. Stay amazed and happy.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: The Minotaur. MAFFEI, P. A. “Gemmae Antiche,” 1709, Pt. IV, pl. 31. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Amazing! appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories“Deuce,” “doozy,” and “floozy.” Part 2“Deuce,” “doozy,” and “floozy.” Part 1An interlude

Related Stories“Deuce,” “doozy,” and “floozy.” Part 2“Deuce,” “doozy,” and “floozy.” Part 1An interlude

Tale of two laboratories

The Los Alamos National Laboratory came to life in 1943 as the concluding segment of the Manhattan Project to produce the atomic bombs for the US Army. In August 1945, these bombs were dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

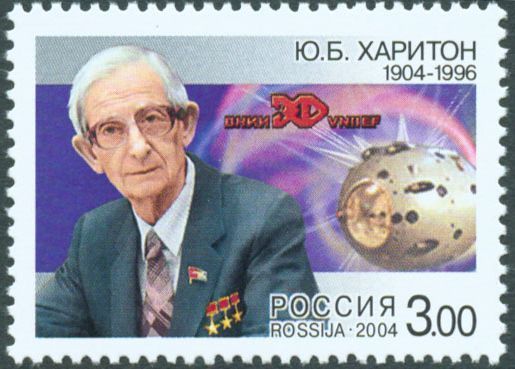

On the other side of the world to Los Alamos, Soviet scientists started researching nuclear fission right after they heard of its discovery in 1939. But when Germany attacked the Soviet Union in 1941, they had to suspend this work and concentrate on traditional weapons. They resumed their nuclear research in 1943. Eventually the secret installation called Arzamas-16 was established some 230 miles east of Moscow. The scientists of Arzamas-16 nicknamed their laboratory “Los Arzamas” and often referred to their scientific director, Yulii Khariton, as the Soviet Oppenheimer.

The poster refers to the deployment of the atomic bombs in anticipation of the expected huge sacrifices of the invasion of Japan in 1945. Photograph of the legendary Ed Westcott; the image is in public domain, courtesy of Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

The two laboratories had a one-way direct connection through espionage — the first Soviet atomic bomb was a copy of the American plutonium bomb. Only the leadership of the Soviet project was aware of the source of information, the scientists were merely given the tasks of what solutions to work out. It was a frustrating experience since they could not bring in their own ideas. For the hydrogen bomb, with less intelligence, the Soviet physicists could utilize their innovative talents.

At Los Alamos, there was a conspicuous concentration of Jewish refugee scientists from Europe. By the time the laboratory came to life, most other scientists had already been engaged in war-related projects. The refugees were latecomers as was the atomic bomb project among war-related research projects. The physics of nuclear weapons was challenging, and the refugee scientists were dedicated to the fight against Germany.

Detail of the Oppenheimer statue in Los Alamos, New Mexico (photograph by I. Hargittai)

At Arzamas-16, a number of the prominent Soviet physicists happened to be Jewish. The nuclear weapons project protected the physicists during the difficult period of 1948-1953 when Stalin’s paranoia developed into active anti-science as well as anti-Semitic persecution. When the pioneer nuclear physicist Yakov Zeldovich got into trouble in Moscow, he found refuge at Arzamas.

Khariton’s year of birth and his first name were not the only similarities with Oppenheimer (Yulii being the Russian equivalent of Julius). They both spent years in Western Europe for postgraduate studies. For both, this included Ernest Rutherford’s Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, England. Like Oppenheimer, Khariton was Jewish, a life-threatening condition under Stalin and a definite disadvantage under the subsequent Soviet leaders. Khariton’s mother lived in Palestine and his father had been kicked out of the Soviet Union and lived in a Baltic state. When in 1940, the Soviet Union annexed the Baltics, he was arrested and directed to the Gulag.

Khariton on Russian postage stamp, 2004.

It was for Khariton’s exceptional talent and abilities that in spite of his circumstances he stayed for forty-six years the scientific leader of the nuclear weapons installation. It was forty-six years of luxurious isolation, a “golden cage,” with his private railway car for travel, other benefits, and the highest decorations.

With few exceptions, the Soviet scientists were dedicated to their nuclear weapons program, at least initially. They were past a bloody war called with good reason the Great Patriotic War, in which their nation literally fought for survival. In the early 1950s, they were taught that a yet more dangerous foreign enemy might attempt their annihilation. This is why even the future human rights fighter Andrei Sakharov could propose murderous schemes to destroy densely populated foreign ports with Soviet thermonuclear devices.

The Soviet scientists worked under the threat of severe punishment in case of failure, but performed impeccably. After the first successful test of nuclear explosion, the regime lavishly rewarded their accomplishments. According to some sources, a simple scheme determined the order of awardees. Those who would have been shot had the test failed, became Heroes of Socialist Labor; those who would have been sentenced to the longest prison terms received the Order of Lenin, and so on.

Gradually, the Soviet scientists realized that placing nuclear weapons into the hands of a dictator could have led to unforeseeable tragedies. Clashes between Sakharov and Nikita Khrushchev demonstrated the blatant recklessness of the Soviet leadership in connection with the nuclear arms race. When during the 1967 war between Israel and its neighbors, Zeldovich heard about the consideration of dropping a nuclear bomb over Israel, he deposited a suicide note in secure hands (he knew the authorities would destroy such a note if they found it) and decided to kill himself if the bombing happened. Fortunately, it did not.

Khariton, on his part, never expressed dissidence. However, when in 1990, amid the great political changes in the Soviet Union, the octogenarian Khariton greeted the first US visitors at Arzamas-16, he told them: “I was waiting for this day for forty years.”

Istvan Hargittai is Professor Emeritus (active) of the Budapest University of Technology and Economics. He is a member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and the Academia Europaea (London) and foreign member of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters. He has honorary doctorates from Moscow State University, the University of North Carolina, and the Russian Academy of Sciences. His latest book is Buried Glory: Portraits of Soviet Scientists (OUP 2013). One of his previous books is The Martians of Science: Five Physicists Who Changed the Twentieth Century (OUP 2006, 2008).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Tale of two laboratories appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIn the footsteps of Alfred Russel Wallace with Bill BaileyThe Milky Way’s tilted dark matter haloSeven historical facts about financial disasters

Related StoriesIn the footsteps of Alfred Russel Wallace with Bill BaileyThe Milky Way’s tilted dark matter haloSeven historical facts about financial disasters

Seven historical facts about financial disasters

Charles IX of Sweden

(1) In the early 1600s, the King of Sweden declared that copper, along with silver, would serve as money. He did this because he owned lots of copper mines and thought that this policy would increase the public’s demand for copper—and also its price, making him much wealthier. Because silver was about 100 times as valuable as copper, massive copper coins had to be minted, including one that weighed 43 pounds. This rendered large-scale transactions in Sweden virtually impossible without a cart and horse. It also explains why Sweden was the first European country to use paper money.(2) In 1925, Britain’s Chancellor of the Exchequer (Secretary of the Treasury) Winston Churchill was considering whether this country should return to the gold standard. Shortly before his announcement, Churchill hosted a small dinner party with both supporters and opponents of the return to gold. According to the only surviving record of that evening, John Maynard Keynes, one of the era’s most articulate opponents of the gold standard, was not particularly persuasive that evening. Churchill announced Britain’s return to gold a few days later; many other countries soon followed. The gold standard is widely recognized as having contributed to the severity of the Great Depression. Could Keynes’ “off night” have brought about one of the worst economic disasters the industrialized world has ever known?

(3) The establishment of the euro is widely regarded as an important cause of the sovereign debt crisis that has ravaged Europe since 2009. Given the difficulties inherent in implementing a common currency and monetary policy for countries as different as Greece and Germany, the Netherlands and Portugal, and Italy and Finland, why did Europeans support the adoption of a single currency? Consider the following: During the pre-euro era, if a tourist had started in one of the 12 countries that adopted the euro in 2002 with one hundred German marks, Irish pounds, or Italian lira and then traveled to each of the 11 other eurozone countries doing nothing in each except exchange money into the local currency at each stop, and was charged a standard 3 percent per conversion, he or she would have spent about 28.5 percent of the original sum on commissions alone.

(4) A major gripe of the American colonists against the British in the run-up to the American Revolution was over economic policy. The philosophy of the British was that Americans should provide the mother country with raw materials at a reasonable price and buy finished products in return. The British statesman William Pitt the Elder went so far as to declare that “…if the Americans should manufacture a lock of wool or a horse shoe,” he would “…fill their ports with ships and their towns with troops.” This led to a somewhat bizarre situation in which an American who wanted to wear a hat made of an American beaver pelt could only buy it after the pelt had been shipped to England, turned into a hat, and shipped back to America to be sold.

(5) In the 1990s Japan suffered from a financial crisis and deep economic recession. The severity of this “lost decade” can be traced to the authorities’ decision to hide the country’s economic problems for as long as possible. This was accomplished by propping up failing banks, in hopes that they would return to profitability when the economy picked up, rather than closing them. Among the measures adopted by the Ministry of Finance in pursuit of this objective were changing accounting rules so banks would not have to publicly reveal their weakness and by forcing healthy banks to provide loans to weaker ones. Small wonder why these living-dead banks subsequently became known as “zombies.”

Germany, 1923: During hyperinflation, banknotes had lost so much value that they were used as wallpaper, being much cheaper than actual wallpaper.

(6) The Federal Reserve System is one of the world’s most powerful and well-regarded central banks. It was not, however, America’s first central bank—or even its second. America’s first central bank, the Bank of the United States, was established in 1791 and lasted only 20 years. Congress soon established a second central bank, but this also ran into difficulties. Its first president had recently gone through bankruptcy proceedings and was soon accused of fraud and mismanagement. The second president ran a scandal-free administration but was so conservative–“even for a banker,” according to his critics– that he was seen as completely ineffective. The bank’s third president was a brilliant financier with poor political instincts who soon ran afoul of President Andrew Jackson, guaranteeing that America’s second central bank also disappeared 20 years after its establishment. It would be another three quarters of a century before America was to have its third–and lasting–central bank.(7) The German hyperinflation during the early 1920s was one of the most severe on record. As a result of the inflation the German mark, which had been worth about two cents, fell to 0.00000000003 cents by its end. The severity of the hyperinflation led Germans to burn banknotes to generate heat and use them as wallpaper. According to one story, a suitcase filled with money was left by its owner on the sidewalk while he went into a store; when the owner returned to retrieve the suitcase, he discovered that a thief had emptied out the money and stolen the now much lighter suitcase. Another story is of the growing practice of ordering two beers at once, since by the time the first beer was consumed, it would have been more expensive to purchase a second.

Richard S. Grossman is Professor of Economics at Wesleyan University and a Visiting Scholar at the Institute for Quantitative Social Science at Harvard University. He is the author of WRONG: Nine Economic Policy Disasters and What We Can Learn from Them and Unsettled Account: The Evolution of Banking in the Industrialized World since 1800. Read his previous blog posts about economics.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: (1) King Charles IX of Sweden painted by unknown artist. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Inflation, Tapezieren mit Geldschein by Georg Pohl from the German Federal Archives. Creative commons license via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Seven historical facts about financial disasters appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFDR, Barack Obama, and the president’s war powersEric Orts on business theoryDeveloping countries in the world economy

Related StoriesFDR, Barack Obama, and the president’s war powersEric Orts on business theoryDeveloping countries in the world economy

November 5, 2013

What has psychology got to do with the Internet?

“What has psychology got to do with the Internet?”

This question was put to me some years ago by an eminent (though clearly not up to date) professor from a well-known university. Hopefully today most of us are pretty clear that the worlds of psychology and the Internet interact constantly.

I believe that the Internet has special characteristics which together create an exceptional environment for the user. To start with, many websites allow you to maintain your anonymity. You may do this by assuming a pseudonym, using your initials or just “leaving the space blank”. This characteristic frees people from many of the issues that constrict them in their day to day offline lives. In other words the anonymous persona on the Internet has no past history, he or she can choose to be whoever they wish. This, for many people, creates positive feelings of self-confidence. So, for example, as an anonymous person I may well have the confidence to comment on a play or a film, safe in the knowledge that no one will retort “Don’t listen to him, he never studied this in his life, he doesn’t know what he’s talking about!” Thus the Internet gives us the power to recreate ourselves in any way we choose.

One of the components of this anonymity, and one which is another factor in the feelings of rising self confidence that many people experience when using the Internet, is the high degree of control assigned to the user as to how much of their physical appearance they expose. Some websites do not ask for any kind of personal identification, but even on those that do, there is a tremendous amount of leeway as to how this is actually done. Thus, while some people may choose to represent themselves by a recent photo, others may, for example, choose a picture of their dog, themselves as baby or a likeness taken some ten years earlier when they were fifteen kilos lighter and had a head full of hair. All these are ways of maintaining anonymity, so no one visiting the site will know if you are white or black, a child or an adult. For people who have some facial disfigurement or any kind of physical characteristic that they believe puts them at a social disadvantage, this freedom from their body image given to them by the Internet is often tremendously liberating and may well make them open to opportunities for social interaction that they would otherwise avoid.

On the Internet people feel a high degree of equality. This stems from the anonymity found there. On the net no one knows who I am and that means that not only am I not judged by my physique or my age, nor am I judged by my wealth and possessions or lack of them. Perhaps surprisingly these feelings of liberty bought about by invisibility have been shown to be important both for the haves and the have-nots. Research has shown that on the net, the wealthy and the physically attractive are likely to be released from familiar feelings that people are only interested in them because of their physical and material attributes and at last feel judged on their own merits, and that those in the contrary position feel similarly.

In many cases, the control that people feel on the Internet, through their anonymity, has a strong impact on their behavior online. This plays out in several ways: individuals feel that if they start an interaction and wish to leave, they can easily disappear with no further consequences, something that does not happen in a face to face interaction. Moreover the fact that on the Internet people do not have to respond immediately leads them to feel less pressure and more control. The Internet gives us the freedom to decide how and when we communicate our message. For those individuals who spend a lot of time shaping and reshaping their message until they are satisfied with the result, this provides feelings of safety and security which provide a very different experience from many face to face encounters.

Another way in which people feel empowered by the Internet is the ease with which they can find similar others. This is significant because when we find people who are similar to us or have similar pursuits we feel that we belong to a group and this belonging is a basic human need. Thus for people who have a minority hobby or interest, it is a tremendous relief to find others who are excited about it, and on the internet locating such individuals is very straightforward.

Today Internet access is almost ubiquitous since through devices such as smartphones and tablets digital access can accompany us throughout our day (and night-should we choose). This means that for many people their online friends, the group they belong to online and maybe even the grandchildren they are in touch with on another continent may accompany them too. This connection may be particularly important for lonely and isolated people or for those who may be going through a crisis or a particularly difficult time and rely on the support they receive from an online forum.

When we put all of this together, we can see that the Internet really does provide an exceptional setting. One in which we feel in control, protected and equal; one that that allows us to recreate ourselves and express ourselves freely wherever and whenever we choose, or equally to remain silent or leave a discussion at will. An environment in which we may find like-minded others with ease and thus build friendships and find support, create groups and community.

Yair Amichai-Hamburger is Director of The Research Center for Internet Psychology, Israel, and author of The Social Net. This article was originally appeared as part of a series on Psychology Today, following a discussion by the author on intergroup conflict.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Hand typing at a computer. By Lincoln Rogers, via iStockphoto.

The post What has psychology got to do with the Internet? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy does this baby cry when her mother sings?Engineering has an image problem that needs fixingDealing with digital death

Related StoriesWhy does this baby cry when her mother sings?Engineering has an image problem that needs fixingDealing with digital death

FDR, Barack Obama, and the president’s war powers

Barack Obama earlier this year became the first president in recent memory to propose limiting the powers of his office when he called for reigning in the use of drones. “Unless we discipline our thinking, our definitions, our actions,” he said on 23 May 2013 referring to the expanded authority of the presidency after 9/11, “we may be drawn into more wars we don’t need to fight, or continue to grant presidents unbound powers more suited for traditional armed conflicts.”

Virtually every president since the Second World War has vigorously protected the executive powers he inherited, and several sought to expand those powers further. The net result is a modern presidency with few constraints built into it when national security in involved. Chief executives have come to employ American power abroad on their own initiative so frequently, particularly in the age of terrorism, that it has become disturbingly commonplace.

This development was effectively given birth on 5 November 1940, exactly seventy-three years ago today, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected to an unprecedented third term. The actions he took immediately before and after that election planted the seeds of the national security state we have become today.

At a time when our headlines are dominated by the NSC, the CIA, the NSA, and the myriad alphabet agencies that constitute our national security infrastructure, it’s hard to imagine a time when they didn’t exist. It’s even harder to imagine a time when they didn’t seem necessary.

By 1939 Roosevelt had long planned to retire to his beloved Hyde Park when his second term ended in January 1941. He was tired, broke, and the New Deal had run its course. Much as he loved being president, he believed his place in history was assured; it was time to go home.

All that changed in September 1939, of course, when Adolf Hitler invaded Poland, causing Great Britain and France to declare war on Germany. FDR became convinced that if those countries fell, the war would come to the Americas. So, despite rampant isolationism in the country, he persuaded Congress to amend the Neutrality Act and made it his top priority to get them everything they needed “short of war.”

The rest is well known: In May 1940 Hitler unleashed the new military art of blitzkrieg and conquered virtually all of continental Europe, including France. Only Britain remained in his path, but most believed that its days too were numbered.

FDR couldn’t find another Democrat who supported his policies and whom he believed could be elected. Concluding he was best qualified to steer the country through this crisis, Roosevelt allowed himself to be “drafted,” which is to say he decided to run.

Although the consummate politician doing all he could to win a tough and hard fought race, FDR never forgot why he was running: he was preparing America for the war he knew was coming. In August 1940, three months before the election, he supported the first peacetime draft in American history and, without seeking congressional approval, he sent fifty aging but desperately needed destroyers to Britain in exchange for naval bases in the Caribbean. Both measures were hugely controversial and involved significant political risk.

He used his election victory as a mandate to persuade Congress to enact Lend-Lease, which gave the president extraordinary powers to send aid to Britain and other allies. His opponents said he was becoming a dictator.

The combination of these actions led directly to changes in the presidency itself, and especially to the tools available to it. Until FDR made Harry Hopkins his de facto national security advisor in 1941, he had no White House staff to assist him; not until after the war would a formal National Security Council be created. Roosevelt had no formal intelligence apparatus on which to rely; his information from abroad was largely ad hoc, not infrequently provided by friends and former Harvard classmates returning from Europe. The president today has a loose collection of intelligence organizations too numerous and complicated for most people to understand.

The leadership Roosevelt exhibited in 1940 and early 1941 succeeded in piercing the veil of isolationism that had defined the country’s foreign policy since its earliest days. Thereafter the United States would be seriously engaged in the affairs of the world, perhaps never more so than in recent years. The neo-isolationists in the Congress today are but a feint echo of those who sought to thwart Roosevelt’s efforts to aid Britain.

After the 1940 election the American electorate would view the presidency very differently, and use expanded criteria in evaluating candidates. The question that year was which candidate was best qualified to protect the American people; polls showed that voters answered it decisively in FDR’s favor.

Elections matter, and the election of 1940 matters still for its profound effect in shaping the internationalist nation we have become. But after nearly three quarters of a century it is time, as President Obama suggested, that we consider disciplining “our thinking, our definitions, our actions” with some thoughtful and measured restraint.

Richard Moe was chief of staff to Vice President Walter Mondale and a senior advisor to President Jimmy Carter from 1977 to 1981. His new book is Roosevelt’s Second Act: The Election of 1940 and the Politics of War, published by Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Official Presidential portrait of Franklin Delano Roosevelt by Frank O. Salisbury. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post FDR, Barack Obama, and the president’s war powers appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA close call: the victory of John AdamsAn Oxford Companion to hosting the most explosive Guy Fawkes NightA few things to remember, this fifth of November

Related StoriesA close call: the victory of John AdamsAn Oxford Companion to hosting the most explosive Guy Fawkes NightA few things to remember, this fifth of November

Why does this baby cry when her mother sings?

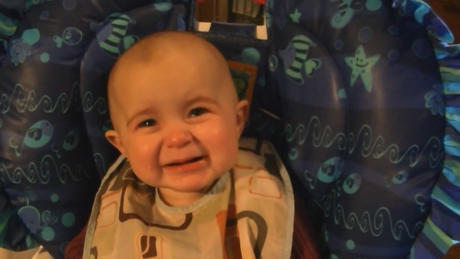

This mesmerizing video has received over 21 million views, and is spreading rapidly through social media.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The baby is 10 month-old Mary Lynne Leroux, who weeps as her mother Amanda sings My Heart Can’t Tell You No, a song most recently popularized by Sara Evans.

Is this baby moved to tears by her mother’s soulful singing?

I have some hunches about this viral video — though nothing that will diminish the marvel of this scene. In the end, we may conclude that the video is even more magical than it first appears…

What we may be witnessing is a remarkable demonstration of emotional contagion, the tendency for humans to absorb and reflect the intense emotions of those around them. Emotional contagion is the foundation of human responses that are essential to social functioning (such as empathy), and is facilitated by the mirror neuron system in the brain.

It is shown in young infants’ tendency to cry when in the vicinity of another crying baby (known as contagious crying), and just as easily to mimic the joy or glee expressed by another person. Emotional contagion may also be seen in the blank stares of infants of depressed mothers or fathers, reflecting their caregivers’ flat affect (emotionally unexpressive faces)

Parents also imitate their infants’ expressions. Infants begin to show a ‘social smile’ by about six to eight weeks of age, and this in turn also triggers more smiling in parents. This moment-to-moment mimicry and matching of emotional expressions in time is emotional synchrony — like ‘getting in step’ with each other, to dance together in a smooth interaction.

What does this have to do with the video?

At the beginning of the video, the mother begins with three spoken sentences. The melody of her voice goes upward at the very end of every sentence: “Mummy’s going to sing you a song…? You want mummy to sing a song, honey? Let me know how you feel about this song, okay?”

Although the infant is not yet verbal, her mother pauses after each question as she would with a speech partner. The mother is essentially inviting the infant into a performance, and the infant responds with smiles and rapt attention.

From video by Amanda and Alain Leroux (licensing@storyful.com)

This orientation to each other is important in establishing the optimal conditions for emotional contagion and synchrony. The singing begins. We cannot see the mother in the video. But when she’s singing, I imagine the emotional expression on her face to be intense as she sings soulfully about loss and longing. The infant immediately mimics this concentrated facial expression (emotional contagion).

From video by Amanda and Alain Leroux (licensing@storyful.com)

The infant shows a yearning and pain in her face way beyond her years, because for the moment she is ‘borrowing’ her mother’s emotion from the song. At the end of each phrase, the mother’s facial muscles probably relax as she takes a new breath—in tandem, we see that the infant also smiles and relaxes at the end of every phrase (emotional synchrony). The depth of this infant’s responses is notable; infants differ from each other as much as adults do, and not every infant shows emotional responses to the same degree.

So does the song itself have no effect?

On the contrary, I believe the singing plays a very important role in this scenario. In daily interactions, emotional expressions are fleeting. Smiles or frowns might flash across the face, constantly changing with speech and environmental cues. But when singing a slow-paced song, facial expressions are shown as if in slow motion—or even as if suspended in time—probably intensifying the effects of emotional contagion.

The structure of the song is also important. In contrast to the mother’s invitation to the song, consisting of three sentences that each rose up in pitch at the end—this song is made up of phrases that generally have a bell-shaped melody. In other words, the melody tends to rise up towards a few high tones, and then has a pronounced downward sweep.

This bell-shaped melody approximates a ‘wailing’ contour that we see in some song structures for (both improvised and composed) mourning songs around the world. It is possible that the ‘wailing’ bell-shaped contour of the phrases of this song may also communicate emotion to the infant, perhaps reflecting ‘emotional contagion’ through vocal cues.

From video by Amanda and Alain Leroux (licensing@storyful.com)

The highest pitches seem to evoke the strongest responses (and tears) in the infant, not only because the greatest musical intensity comes at the peak of a melody—but also perhaps as the highest tones correspond with the most concentrated facial expressions of the singer.

In the closing moments of the video, the mother soothes the infant with her speech. In contrast to the arousing rising inflections before the song, the melody of the speech now descends (like a downward staircase): ”It’s just a song. It’s just a song.” Amanda Leroux demonstrates that emotional speech is a version of song.

Does this analysis make the video any less magical?

In my view, it may be even more remarkable and more compelling to think that what we are witnessing may not just be the power of the human voice and singing—but a window into how deeply and powerfully we are moved by the emotions of those around us, even in our earliest interactions.

Emotional contagion induced by film characters on screen (especially in close-ups of the face)—and sensitivity to rising and falling melodies in film scores, as well as speech contours – are also mechanisms by which films take us on an emotional journey. If filmed while watching a movie, you might catch yourself mimicking facial expressions of the characters, even though nobody is responding to your smiles and grimaces in the dark.

Mary Lynne Leroux at 10 months is ‘in tune’ with her mother in more ways than one—through her, we are reminded of how we are inherently social and emotional beings, as well as musical ones.

So why does this baby cry when her mother sings?

For all the same reasons that we are moved when we watch the mother’s emotions so powerfully reflected in the face of this infant.

Acknowledgments

The YouTube video is by Amanda and Alain Leroux and can be found here . To use this video in a commercial player or broadcast, contact licensing@storyful.com.

Siu-Lan Tan, is Associate Professor of Psychology at Kalamazoo College in Michigan, USA. She is primary editor of The Psychology of Music in Multimedia (Oxford University Press 2013), the first book consolidating the research on the role of music in film, television, video games, and computers. A version of this article also appears on Siu-Lan Tan’s blog entitled What Shapes Film: Elements of the Cinematic Experience on Psychology Today.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: From video by Amanda and Alain Leroux (licensing@storyful.com)

The post Why does this baby cry when her mother sings? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGravity: developmental themes in the Alfonso Cuarón filmRussian choral music: the joy of discovering ‘unknown unknowns’Children’s invented notions of rhythms

Related StoriesGravity: developmental themes in the Alfonso Cuarón filmRussian choral music: the joy of discovering ‘unknown unknowns’Children’s invented notions of rhythms

Discussing capital markets law

There are many mechanisms for raising capital — debt, derivatives, equity, high yield products, securitization, and repackaging — which fund and drive the economy. But as international financial markets move and shift as the world changes, regulations and legal frameworks must also adapt rapidly. What will sovereign debt look like in the future? Will the European Monetary Union break up? How have boilerplate contract terms changed with new decisions and judgements?

General Editors Jeffrey Golden and Lachlan Burn, and Mitu Gulati, Regional Editor for North America sat down to discuss the Eurozone crisis, what academics and practitioners learn from each other, and the goals and achievements of Capital Markets Law Journal.

On the origin of the Capital Markets Law Journal:

Click here to view the embedded video.

On the future of the Eurozone:

Click here to view the embedded video.

On the Capital Markets Law Journal’s achievements:

Click here to view the embedded video.

On the personal and professional satisfaction of Capital Markets Law Journal’s editors:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Capital Markets Law Journal is essential for all serious capital markets practitioners and for academics with an interest in this growing field around the world. It is the first periodical to focus entirely on aspects related to capital markets for lawyers and covers all of the fields within this practice area. The journal provides a mix of thoughtful and in-depth consideration of the law and practice of capital markets through analytical articles on topical issues written by leading practitioners and academics in the international arena. There are also articles on matters of best practice and opinion on legal and practice developments from around the World.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Discussing capital markets law appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBeware of gifts near elections: Cyprus and the EurozoneDrone technology and international lawWhite versus black justice

Related StoriesBeware of gifts near elections: Cyprus and the EurozoneDrone technology and international lawWhite versus black justice

To medical residents

The completion of residency training is a time of key decisions. For residents, the assessment of several strong job options is a long-awaited reward after years of preparation. However, unlike the regimented and scheduled process of residency applications and interviews culminating in match day during the fourth year of medical school, the search for a job or fellowship is self-directed, individualized, and without a set end point or deadline. Your job quest might be the first application process in your career that does not involve a ‘click here to apply’ button.

This flexibility is both exciting and intimidating. As you decide what you want to do after residency, you will consider the obvious questions: Should I work in a private practice or an academic environment? What’s the best geographic location? What’s the best practice size for me? Should I find employment with an established physician or become self-employed?

This flexibility is both exciting and intimidating. As you decide what you want to do after residency, you will consider the obvious questions: Should I work in a private practice or an academic environment? What’s the best geographic location? What’s the best practice size for me? Should I find employment with an established physician or become self-employed?

You will also need to think about what your definition of moving forward in your career means. Do you aspire to become the most respected and sought after clinician? Do you aim to become a hospital wide leader and decision maker? Do you intend to become a researcher, focusing on clinical trials or basic science research in a laboratory environment? Do you wish to focus on public health to change the outcomes for a subset of patients?

Like many doctors at this stage, you may look at some professional leadership positions and wonder: ‘What would I have to do to get there?’ Specialty training formally qualifies you for practice privileges, but there is no official qualification for some of the other interesting opportunities that you may aspire to. Who gets to become program director? Who becomes hospital CEO? Who will become a health policy leader? Who will edit professional journals? Who will write the board exam questions 20 years from now? Who will decide if new procedures are worthy of authorization and acceptance into standard care?

Residency training qualifies you to practice your specialty. But it doesn’t determine how you will practice your specialty or if you will become a leader within your specialty or within the whole field of medicine itself. In fact, most leaders in medicine carved their own paths. There are many roads to leadership and innovation. It is important to realize that no one will invite you to become a leader. Such roles do not happen by accident. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Leaders who aren’t afraid to forge a new road can move their professions in uncharted directions.

Applications for non-traditional positions are not accompanied by a conveniently placed ‘click here to apply’ button on a website. So if you want to take an innovative route, you will need to take steps to determine whether a non-traditional job or leadership position is right for you and learn how to get there. Your specialization and training only serve to open doors for you. Qualifications never close doors. You have a long professional future ahead of you and it is advantageous to gather information about your options and to use the most effective approaches to open doors for yourself. Your personal and professional goals are valid and worthy of your follow through. Medicine as a whole will benefit when caring doctors branch out into all areas of medicine to become leaders and to ensure quality and innovation.

Heidi Moawad M.D. is a neurologist and author of Careers Beyond Clinical Medicine, an instructional book for doctors who are looking for jobs in non-clinical fields. Read her previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: group of young doctors and nurses in hospital. © michaeljung via iStockphoto.

The post To medical residents appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTo medical students: the doctors of the futureWhy do women struggle to achieve work-life balance?Add a fourth year to law school

Related StoriesTo medical students: the doctors of the futureWhy do women struggle to achieve work-life balance?Add a fourth year to law school

An Oxford Companion to hosting the most explosive Guy Fawkes Night

It’s early November and you’re panicking. You’ve decided to host a themed party the likes of which have never been seen before but you don’t know which theme to choose. You like eggs but Easter is too far away? You enjoy Christmas but can’t stand eggnog? You love Yom Kippur but you’re not Jewish? Never fear. If you have a penchant for explosives, a carnal need to set things on fire, and a deep-rooted sense of rebellion (and I know you do) then I have the perfect theme for you: Guy Fawkes Night.

For over 400 years, bonfires, fireworks, and effigies have burned on November 5th to commemorate the failed Gunpowder Plot put together by Guy Fawkes and twelve other conspirators. With a little help from OUP, you could out-shine all previous Bonfire Night celebrations. So pick up your Roman Candles, grab some sparklers, and join me as we run down OUP’s top five tips for hosting the perfect Guy Fawkes Night.

1. Know Your History

All the best hosts know everything about the themed parties they are throwing. Would Elton John ever be found wanting at one of his parties? No. And neither should you. Did you know for example that the actual gunpowder plot took place on the night of the 4th November, 1605? The reason that we celebrate Guy Fawkes Night on the 5th November is that it wasn’t until the night after the failed plot that Londoners found out their King had been saved from harm and lit bonfires in thanksgiving. Did you also know that as well as being frequently referred to as Bonfire Night, Guy Fawkes Night is also infrequently called Pope’s Night?

The thirteen English Catholic rebels had planned to blow up the Houses of Parliament while the King, the Prince of Wales, and key members of Parliament were inside. Following the death of Queen Elizabeth I in 1603, English Catholics hoped that under King James I’s rule they would be persecuted less. However, this did not turn out to be the case. Instead, they continued to be mistreated and victimized in the first few years of James’s reign. A group of thirteen rebels including Guy Fawkes, Robert Catesby, and Thomas Percy decided violent retribution was the only way to respond to such persecution.

However, as the plot developed, some of the other conspirators realised that many innocent men, some of whom had campaigned on behalf of English Catholics, would be killed too. A letter was written to Lord Monteagle that warned him to stay away from Parliament around the date of November 5th. Inevitably the letter reached the King’s forces and this led to the capture, arrest, torture, and execution of Guy Fawkes, who was caught in the cellar underneath Parliament with 36 barrels of gunpowder.

Arrest warrants were circulated for the twelve other conspirators who had escaped. Thomas Percy, the subject of an arrest warrant that can be viewed on Oxford Scholarly Editions Online, was shot dead alongside his friend Robert Catesby in a siege operation in Staffordshire on November 8th, 1605. All thirteen rebels were killed within two weeks of the failed plot. The majority were tortured before their execution. (Best not to mention that at your party though it might dampen the mood.)

2. Plan for fire and fireworks

I know what you’re thinking: stop with the history lesson, I just want to burn things. Calm down, Guido, we’re getting to that.

Fireworks often take centre-stage on Guy Fawkes Night, and a mixture of Roman Candles, Diadems, and Catherine Wheels will make your party guests “ooohhh” and “aaahhh” in unison. Do remember to stand well clear once your fireworks are lit though; otherwise you might need to read up on this subject. Lewes is world famous for its firework display and celebration of Bonfire Night, and people come from all over to see the Lewes bonfire each year. The etymology of the term ‘bonfire’ dates back to Middle English and stems from the words ‘bone’ and ‘fire’. In the Middle Ages, the term originally denoted an open fire on which bones were burnt, often as part of a celebration.

3. Build the Guy

Within years of the failed gunpowder plot, people began mounting effigies on top of their bonfires to add to the fiery spectacle of Guy Fawkes Night. Until the latter part of the 20th century, the “Guy” effigy would nearly always represent Guy Fawkes himself (occasionally it was the Pope). Nowadays, effigies of politicians, sports stars, and Z-list celebrities burn on top of bonfires across the land as the quirky tradition of the “Guy” takes on a new meaning. The preparation of the “Guy” has also changed. In the past, children built the model Guy, paraded him down the street, and begged passers-by to ‘give a penny for the Guy’. The money the children made would then be spent on fireworks. However, adults are increasingly responsible for setting the homemade effigy ablaze. To be set alight before a baying crowd seems a harsh, but fitting, legacy to the “last man to enter Parliament with honest intentions”.

4. Create the playlist

In every group of friends, there is always that one person who will pull out a guitar, seemingly out of thin air, and just start singing away. Why not pre-empt this atrocity by organising a planned sing-a-long? This chant may not encourage aggressive twerking, but many of the hymns and chants sung on November 5th have been passed down from century to century to remember the failed gunpowder plot and early copies are preserved in museums across the UK. The earliest known copy of that Guy Fawkes chant was found in the Tower of London in the early 17th century, the same place that some of the conspirators met their gruesome end.

5. Fire up some food

What makes Bonfire Night the ideal theme for the perfectionist host is the cooking. You don’t need to miss the fun, frolics, and fireworks as you keep going in and out of the kitchen to check on the food. In fact, your oven is the centrepiece of the party; the bonfire itself! Food such as baked potatoes, roasted marshmallows, and cheese fondue are perfect to warm you up on a cold, autumnal night. But if it’s all getting too much for you, and little Timmy keeps running too close to the fire, then you have two options. 1) Kick back and treat yourself to a glass of mulled wine or 2) Invite Timmy to try the Treacle Toffee you made earlier. This recipe is designed to keep jaws locked shut – perhaps if the conspirators had been eating this during the days leading up to November 5th, history would be very different…

At times, your party might resemble the London Riots of August 2011, but as long as you follow all the safety guidelines, there’s no reason why your party shouldn’t be the social highlight of the year. Follow OUP’s Bonfire Night advice and get ready for some festive, fiery fun; just don’t set fire to the cat.

Daniel Parker is Publicity Assistant for Oxford University Press and will be eating his body weight in toffee apples on Bonfire Night. You can find more about the Oxford resources mentioned in this article in Oxford Reference, Oxford Index, OSEO, ODNB, Who’s Who, and Oxford Dictionaries. You can also listen to the ODNB podcast about Guy Fawkes.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Firework Photomontage: Guy Fawkes Night, London, 2007. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post An Oxford Companion to hosting the most explosive Guy Fawkes Night appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA few things to remember, this fifth of NovemberA close call: the victory of John AdamsRussian choral music: the joy of discovering ‘unknown unknowns’

Related StoriesA few things to remember, this fifth of NovemberA close call: the victory of John AdamsRussian choral music: the joy of discovering ‘unknown unknowns’

November 4, 2013

Russian choral music: the joy of discovering ‘unknown unknowns’

Donald Rumsfeld has rather soured the notion of discovering things of which we were previously unaware. If you don’t recall the quote, it’s worth reminding yourself:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Rumsfeld may have been eager to find his ‘unknown unknowns’, but ultimately his sought-after objects weren’t good ones. Yet there are very many wonderful things, as yet outside of one’s world view, whose discovery may change the way we think about this or that – a great novel, the landscape of a country seen for the first time, or a new musical repertoire.

And this is where I am rather jealous of the future readers and performers of the new OUP choral collection Russian Sacred Music for Choirs. I already know the music in this collection and will therefore not experience again the wonder of getting to know this repertoire for the first time.

And this is where I am rather jealous of the future readers and performers of the new OUP choral collection Russian Sacred Music for Choirs. I already know the music in this collection and will therefore not experience again the wonder of getting to know this repertoire for the first time.

I first met its editor Noëlle Mann in the late 1990s as I began my PhD at the University of London. During the course of my studies, I had met (and often had the privilege of being taught by) some incredibly gifted, dedicated musicians and academics. Noëlle was all of that but what struck me most profoundly was the irresistible drive and boundless energy she applied to any venture to which she committed herself. For any sphere in which Noëlle worked, there were no casual observers; the irresistible and happy vortex Noëlle created left nobody watching dispassionately from the wings. You simply got involved.

It just so happens that the Russian choral repertoire was Noëlle’s longest-standing preoccupations and prolific vortices. Her love of this repertoire led her to found the Kalina Choir, the first UK choir exclusively dedicated to performing this repertoire, and teach this music (in performance and practice) to generations of university students. In her edited collection, Noëlle’s vision was to offer to English-speaking choirmasters and their choirs a glimpse into a world of choral music almost unknown outside Russia.

Noëlle sadly died in 2010 before the anthology was completed. Anyone who came to know Noëlle and her work — whether on Russian sacred chant and choral music, or the life and work of Prokofiev — will very quickly have understood that, for her, music was fundamentally and inescapably human and performative. This collection bears witness to that and is the product of many years of directing performances of this repertoire. Every concert of Noëlle’s I attended invariably closed with a setting of ‘Many years’ (Mnogaya leta), a celebratory hymn wishing the person(s) to whom it is sung a long and peaceful life. By the same token, I wish all who discover this incredible repertoire many years of enjoyment and musical fulfilment.

Kristian Hibberd is a musicologist and son-in-law of the late Noëlle Mann. Before her death in 2010, Noëlle tasked Kristian and her daughter, Julia Hibberd, with the completion of the anthology: Russian Sacred Music for Choirs.

Noëlle Mann was born in 1946 in south-west France and died in London in 2010. Having trained first as a concert pianist, Noëlle moved to the UK and read music at Goldsmiths College (University of London), during which she began researching the znamenny chant of the Russian Orthodox Church. Noëlle’s interest in the Russian choral tradition led her in 1993 to establish the Kalina Choir, the first UK choir exclusively dedicated to performing Russian choral music. Through this and subsequent choral directing, Noëlle developed her research and performance practice of this music. As a musicologist, Noëlle’s interests embraced both Russian choral music and the life and work of Serge Prokofiev. Noëlle became the Founding Curator of the Prokofiev Archive in 1994 and established the academic Centre for Russian Music at Goldsmiths College in 1997. In 2001, Noëlle founded and became Editor of Three Oranges, an academic journal dedicated to the study of the life and times of Prokofiev. She is the editor of Russian Sacred Music for Choirs. Oxford Sheet Music is distributed in the USA by Peters Edition.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Russian choral music: the joy of discovering ‘unknown unknowns’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA spooky Halloween playlistIn memoriam: Lou ReedSofia Gubaidulina, light and darkness

Related StoriesA spooky Halloween playlistIn memoriam: Lou ReedSofia Gubaidulina, light and darkness

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers