Oxford University Press's Blog, page 877

November 20, 2013

The year in words: 2013

Oxford’s lexicographers use the Oxford English Corpus (OEC), a 2-billion-word corpus of contemporary English usage gathered since 2000, to provide accurate descriptions of how English is used around the world in real life. A corpus is simply a collection of texts that are richly tagged so that they can be analyzed using software (we use the Sketch Engine). The OEC helps us answer questions like “how common is the spelling analog (as opposed to analogue) in British English?” or “what are the most common objects of the verb curate?” It is intended to serve as a synchronic corpus of English, allowing us to analyze contemporary English usage across different regions, in different subject areas, in different registers, and in different types of text.

To better track changes in English as they are happening, OUP has recently set up a new corpus project, the New Monitor Corpus (NMC), to facilitate diachronic analysis. The NMC monitors more than 12,000 RSS feeds for articles in a broad range of categories, collecting and adding about 150 million words of English each month. This allows us to observe changes over time in one-month increments, enabling editors to identify new words and patterns as they emerge, and distinguish which items seem to be trending towards widespread currency.

Although the NMC was established specifically to identify new words and meanings, it also provides an interesting window onto social trends, by showing us what is being discussed in a wide variety of online sources, including newspapers and blogs. The list below highlights one word each month which experienced an identifiable usage spike, apparently due to current events. (Frequencies are expressed as a rate per billion words.)

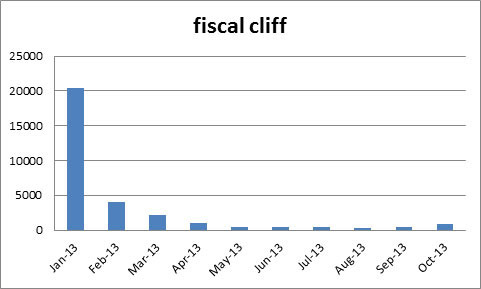

January

In late 2012, the US media was consumed with speculation about the financial cataclysm that might occur if Congress failed to stop several scheduled economic changes, including automatic spending cuts and the expiration of tax cuts, from happening at once. Monthly usage of the term peaked in December 2012, at almost 45K/billion, with fears of approaching doom reaching a fever pitch. Ultimately, a compromise bill partially resolving the crisis was signed into law on 2 January. Mentions of fiscal cliff fell off precipitously afterwards; eventually new budgetary crises reared their heads, and Americans began discussing them instead.

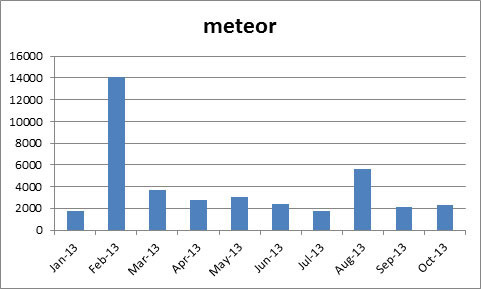

February

On the morning of February 15, a large meteor exploded above Chelyabinsk, Russia, strewing meteorites over a large area and causing injuries and property damage. Unsurprisingly, the month of February saw a huge spike in the frequency of the word meteor. The uptick in August is probably due to the annual Perseid meteor shower.

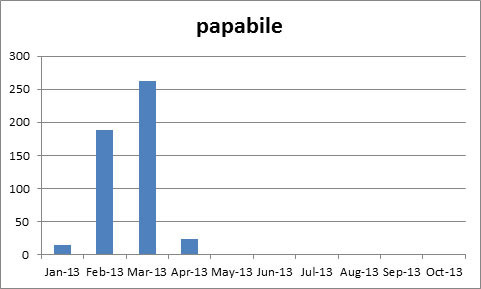

March

The opportunity to use the word papabile, meaning ‘a prelate worthy or likely to be elected as pope’, doesn’t come up very often, but 2013 was one such time. The word’s usage began to climb in February, when Pope Benedict resigned, and then peaked during the conclave at which Pope Francis was elected. Since then, it has largely dropped out of use, waiting to be dusted off by the world’s English speakers during the next papal conclave.

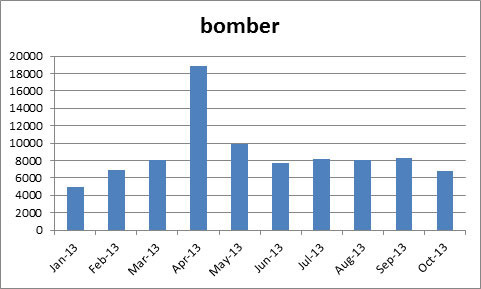

April

On 15 April 2013, the Boston Marathon was cut short when two bombs were detonated at the finish line. In the aftermath of the tragedy and the ensuing manhunt, our corpus registered a significant increase in usage of the word bomber.

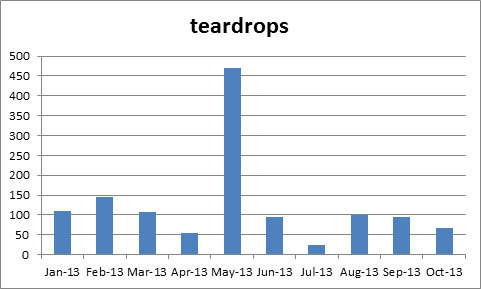

May

Why the sudden increase in teardrops in May? The Eurovision Song Contest. The winner was Denmark’s song “Only Teardrops”, sung by Emmelie de Forest.

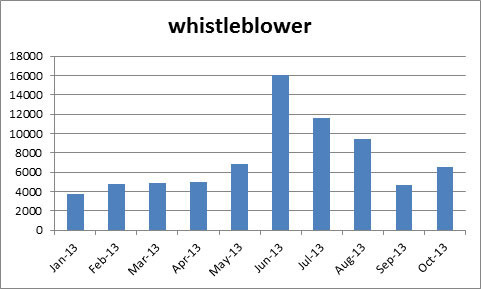

June

The Guardian published the first story in its series based on classified documents provided by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden on 1 June 2013. Increased usage of the word persisted through the summer.

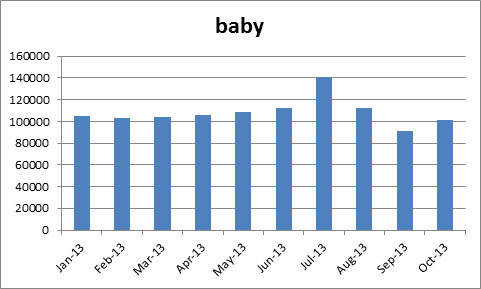

July

Baby is a very common word in English, so to spark a discernible increase in its usage, a single event would have to be discussed a lot. The birth of Prince George of Cambridge on 22 July 2013 appears to meet that standard, with speculation about the “royal baby” contributing to an upward trend in overall usage of the word.

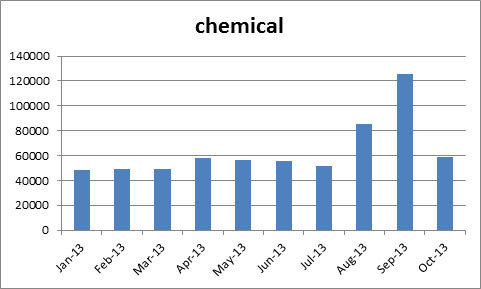

August

A noticeable increase in usage of the word chemical can be observed starting in August, when Ghouta, in Syria, was hit by rockets containing sarin gas. Usage increased still further in the following month, as government officials in the United States, United Kingdom, and other countries debated their response to the chemical attacks.

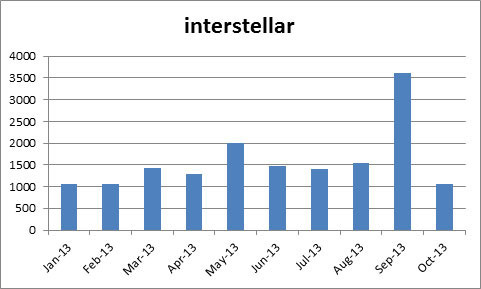

September

In September, researchers confirmed that NASA’s Voyager 1 probe had officially entered interstellar space in August 2012, leaving our solar system. It is the first man-made object to do so.

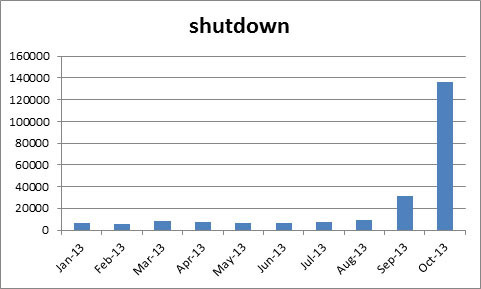

October

In British English, the word shutdown tends to be associated with things like machinery, systems, and sports leagues. In American English, the government shutdown, in which the government ceases to function because of a lack of approved funding, weighs heaviest in the evidence. This was particularly true in October of this year, when the United States experienced its first federal government shutdown since 1996.

November and December

We won’t be able to evaluate the data collected for November and December until those months are complete. (A cynic might question how the year can be declared over with more than a month remaining.) Nonetheless, we can speculate on what the future holds. It seems likely that we will remember November for its association with the terrible tragedy of the Philippine typhoon. December’s words remain wholly unspoken, so we are free to hope for a more optimistic lexical emblem. Peace, perhaps.

Katherine Connor Martin is Head of US Dictionaries, Oxford University Press. She is a regular contributor to the OxfordWords blog.

The Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year 2013 is ‘selfie’. The Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year is a word, or expression, that has attracted a great deal of interest during the year to date and judged to reflect the ethos, mood, or preoccupations of that particular year and to have lasting potential as a word of cultural significance. Learn more about Word of the Year in our FAQ, on the OUPblog, and on the OxfordWords blog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: All word charts created by Oxford Dictionaries using the New Monitor Corpus.

The post The year in words: 2013 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesScholarly reflections on the ‘selfie’Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year 2013: ‘selfie’Edwin Battistella’s words

Related StoriesScholarly reflections on the ‘selfie’Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year 2013: ‘selfie’Edwin Battistella’s words

Ten obscure facts about jazz

The harsh restrictions that North American slaves faced between the sixteenth and nineteenth century led to the innovative ways to communicate through music. Many slaves sang songs and used their surrounding resources to create homemade instruments. This tradition continued to develop after emancipation and several black music genres began to form. From its early forms, such as ragtime, this collection of musical styles, sounds, and culture developed throughout the twentieth century as the great American art form: jazz. We gathered ten facts from Mervyn Cooke’s The Chronicle of Jazz to highlight this evolution.

In 1900, John Philip Sousa took The Sousa Band on a European tour, performing ragtime arrangements at the Paris Exposition. Sousa’s Band was well received and had the honor to represent the United States of America as the official band of the country.

During the World War I, Lieutenant James Reese was the director of the all-black military band of the 369th US Infantry, “The Hellfighters”. In France, they played in several cities during a six week period from February to March 1918, and were met with much success.

Having started out as a drummer, Lionel Hampton recorded a vibraphone solo in 1930 and subsequently became this neglected instrument’s first virtuoso. Invented during World War I, the vibraphone is similar to the xylophone and is made of metal bars laid out in a keyboard arrangement. Each bar is suspended above its own tubular resonator, which contains an electrically driven fan that produces an oscillating tone.

In 1939, Duke Ellington and his band sailed to Le Havre for a concert tour of France, Holland, and Denmark. Knowing of Hitler’s antipathy towards jazz, they passed anxiously through Nazi Germany.

Count Basie’s first European tour took his band to Copenhagen, Stockholm, Amsterdam, Brussels, and cities in France, Germany, and Switzerland. Basie is the originator of the brand of Kansas City jazz that became the hottest big-band sound in the 1930s and 1940s.

Portrait of Count Basie, Aquarium, New York, NY between 1946 and 1948. Photo by William P. Gottlieb. Public domain via Library of Congress.

In 1963, Duke Ellington embarked on a tour arranged by the US State Department. His itinerary included Syria, Jordan, Jerusalem, Beirut, Afghanistan, India, Ceylon, Pakistan, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Turkey, Cyrus, Egypt, and Greece. The tour was abandoned after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy on 22 November 1963.

By the early 1950s, the Hot Club of Japan (founded in 1946) began to flourish, and the climate was ripe for American performers to undertake high-profile tours to locations in Tokyo and Osaka. Many visits were sponsored by Norman Granz’s “Jazz at the Philharmonic” from 1953 onwards, and tours by artists of the stature of Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and Art Blakey became commonplace in the mid-1960s.

Bill Evans is considered to be one of the most respected keyboard players in modern jazz. His harmonic daring and rhythmic subtlety influenced many emerging talents in the 1960s. In 1996, more than eighty hours of Bill’s previously unknown recordings of live gigs, 1966-80, were discovered at the Village Vanguard in Greenwich Village, New York.

Steve Lacy was a soprano saxophone player and composer who worked with Thelonius Monk, Gil Evans, and Cecil Taylor. In the late 1960s, Steve decided to move to Europe and take free jazz to Italy and France. After thirty-three years spent in Paris, Steve returned to the United States to teach at the New England Conservatory in Boston.

In 2001, Regina Carter played jazz on Niccolò Paganini’s $40-million antique violin in Genoa, Italy, and subsequently recorded on the instrument for the album Paganini: After a Dream. This performance outraged many classical music purists; Paganini was an Italian violin virtuoso.

On 20 November 2013, starting at 9:00 a.m. EST, Oxford University Press is giving away 10 copies of The Chronicle of Jazz to residents of the United States, 18 years of age and older. The contest ends on November 21st, 2013 at 11:59pm. Visit the link for entry details.

Dr. Mervyn Cooke is Professor of Music at the University of Nottingham and has published extensively on the history of jazz, film music, and the music of Benjamin Britten. His most recent books include The Chronicle of Jazz, The Cambridge Companion to Jazz, The Hollywood Film Music Reader, The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century Opera and Letters from a Life: The Selected Letters of Benjamin Britten.

Dionna Hargraves works in marketing at Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Ten obscure facts about jazz appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesJazz, the original coolWhat makes music sacred?Images of jazz through the twentieth century

Related StoriesJazz, the original coolWhat makes music sacred?Images of jazz through the twentieth century

Executive compensation practices hijacked and distorted by narrow economic theories

“Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.”

Keynes’ warning applies to debates about skyrocketing levels of executive compensation in the United States and elsewhere. Even leading advocates of reform who insist on better measures of “pay-for-performance” continue to be misled by narrow economic theories that lie at the root of the problem.

Two main economic theories have been translated into the executive compensation debate and established dominance in the last few decades. One is the “agency costs” approach to corporate governance which focuses on the relationship between “principals” and “agents.” This approach is also known as principal-agent theory. Another theory posits an “efficient capital market hypothesis,” which argues that stock prices are the most accurate possible estimation of a public corporation’s value. The combination of these two theories has led in practice to extreme and sometimes absurdly high levels of executive pay. We need to rethink the applicability of these theories. Entrenched interests in both business and academia will resist. Without a change in theory, however, no serious change can be anticipated in practice.

Principal-agent theory derives from a basic insight. Most business relationships involve legal relationships in which one person (the “agent”) agrees to work on behalf of another (the “principal”). The most common example is employment. Principal-agent theory assumes that self-interested motivations will cause agents to tend to “shirk” their responsibilities. To solve this problem, the principal must either oversee the agent (“monitoring”) or find creative ways to tie the agent’s economic interests to the principal’s (“bonding”). In law, however, there is a contrary assumption: the agent owes a “fiduciary duty” to the principal. Acting selfishly and against the principal, such as by taking “secret profits,” is viewed as wrong and punished.

Principal-agency theory is useful. People often behave according to self-interest, and it makes sense to examine firms in terms of agency costs to improve organizational efficiency. The error comes when this economic theory is taken as a complete explanation of the complex structures and motivations in large corporations. Principal-agent theory attempts cut through this complexity by arguing that only two major groups in a corporation matter. The shareholders are called “principals,” and the executives are called the “agents.” The economist then “solves” for the problem agency costs.Executives who otherwise would act only in their own self-interests are difficult to monitor effectively (because shareholders are often dispersed in corporations). Bonding is therefore advocated as the best solution. In practice, this translates into paying executives in stock or stock options. An executive performs in the best interests of shareholders, according to this theory, because it is in his or her own self-interest to do so.

This economic theory does not bear close comparison with the reality of large business corporations. The law gives a different story. Under a traditional legal account, executives owe “fiduciary duties” to act in the best interests of the shareholders and the corporate business as whole. This idea of the corporate interest being larger than shareholders makes sense. Long-term success depends on many factors, including the effective management of employees, creditors, suppliers, and customers. Great CEOs lead their companies by example and by managing legal and other risks effectively. They make the right calls when faced with ethical dilemmas which, at a minimum, keep their firms out of serious legal trouble. The principal-agent theory of the firm oversimplifies the tasks of executive leadership. It also assumes that CEOs will be motivated only by selfishness, when instead a great CEO must exhibit leadership abilities that instill trust and motivate others. Adhering strictly to a principal-agent view of the firm destroys expectations of trust and integrity in corporate leaders.

The second problematic economic theory is the efficient capital market hypothesis. This theory posits that current stock market trading prices are the best estimation of corporate value. This may often prove to be the case, but not always. The rising field of behavioral finance shows that investors are also subject to social psychological influences, causing “panics” (crashes) or “irrational exuberance” (booms). If so, then stock prices are not always a good measure of the current value of a company. Paying an executive for stock-price performance can therefore often get it wrong. During booms, executives may be radically overpaid. During busts, they may be unfairly penalized.

Recalling the legal structure of firms provides a better explanation. Business corporations are organizations of power and authority, not simply a “nexus of contracts” or loose assembly of individuals. Executives exert substantial control over the organizations that they ostensibly also serve. They therefore have great responsibility, and the legal and ethical norms governing expectations for their behavior are essential. A narrow view of executives as essentially selfish leads to a self-fulfilling prophecy (so to speak). Executives will then use their power and authority to overpay themselves. Shareholders may not object and may even cheer them on in the short-run because gains in executive stock options mean gains in shareholder value. But these economic theories do not work well for the long-run. Executive selfishness eventually destroys firms and harms the many people who compose firms and rely on them.

Another unanticipated consequence of following these economic theories has been that they have created high-powered organizational incentives for executive fraud. In theory, executives should work to increase stock price honestly. In practice, many executives have been tempted to “cook the books,” “manage earnings,” and engage in other deceptive activities to hit short-term stock option targets. As a result, we have witnessed an unending wave of high-level corporate fraud and misbehavior.

It will not be easy, but it is time to constrain the influence of narrow economic theories of the firm and to recover some traditional legal values. We should eschew economic theories that assume that business executives are motivated only by greed and self-interest. Instead, we need to return to old-school values of fiduciary duty, integrity, and a larger vision to manage companies in the interests of others who depend on them and who contribute to their success. Healthy compensation for executives should follow only when these larger goals are met.

Eric W. Orts is the author of Business Persons: A Legal Theory of the Firm, which presents a foundational legal theory of the firm in contradistinction to prevailing economic theories and discusses policies informing executive compensation as an example of how economic theories have gone wrong. Eric Orts is the Guardsmark Professor of Legal Studies and Business Ethics at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. He is also a Professor of Management, faculty director of the Initiative for Global Environmental Leadership, and faculty co-director the FINRA Institute at Wharton. Currently, he is a visiting professor at INSEAD in France.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Time to pay. © Gustavo Andrade via iStockphoto.

The post Executive compensation practices hijacked and distorted by narrow economic theories appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEric Orts on business theoryDoes Mexican immigration lead to more crime in US cities?Why is wrongdoing in and by organizations so common?

Related StoriesEric Orts on business theoryDoes Mexican immigration lead to more crime in US cities?Why is wrongdoing in and by organizations so common?

Greeks and Romans: literary influence across languages and ethnicities

How could you have one novel, poem, children’s book, that wasn’t influenced by others? But people haven’t much considered what distinguishes literary interaction that jumps across languages and countries. An interesting case is the impact of Greek literature on Latin literature. (We’ll concentrate on that way round, and on the time after the earliest Latin writers—we want systems, not origins.)

Here’s an Italian writer adapting a French half-sentence on literary lovers: “La gente volgare non immagina quali profondi e nuovi godimenti l’aureola della gloria, anche pallida o falsa, porti all’amore” (“common people do not imagine what deep new pleasures the halo of glory, even pale or false, brings to love”; D’Annunzio, 1889); “On n’imagine pas, d’ordinaire, ce que le nimbe de gloire le plus pâle même, ajoute à l’amour” (“people do not usually imagine what even the palest halo of glory adds to love”; Péladan, 1887). Key words recognizably match: immagina/imagine, gloria/gloire, pallida/pâle, amore/amour; but Greek and Latin vocabularies look fundamentally separate: a chasm, little bridged by borrowings. D’Annunzio is plundering a book just out; but Latin writers mostly feign to draw on a literature that had long faded out.

Let’s develop these two points in turn. Taking something from a writer in your own language creates an intimate relationship; often you use the very same words. Romans think the languages quite unlike: Latin weighty and hard, Greek light, quick, elegant. This suggests a moral contrast; aesthetically Latin is felt inferior. Greek’s sounds are “sweet”, “delightful”, Latin’s “gloomy”, “horrid”, especially the dreadful f, which requires a voice scarcely human. Latin writers contrast Greek and Latin passages, and find the Greek simpler, truer; most Romans thought Greek had a richer vocabulary (Cicero protested). A challenge, then: the Romans wanted victory, or at least an equal battle. That’s the recurring image: warfare. “Cicero,” says one writer, “stopped us being vanquished artistically by those we had vanquished in war.”

Woodcut showing Cicero writing his letters.

But it’s a war with the dead. Officially Latin literature began in 240 BC; by that date (supposedly) the major Greek poets were nearly finished. That last bit Romans got from later Greeks. Latin poets rarely name any Greek poet later than the third century. By then Greek oratory too had entered its alleged decline. Cicero, who claims to begin Latin philosophy, urges Romans to “snatch glory for this genre too from declining Greece and transfer it to this city.” Aggressive, spatial language. Actually, this supposed succession doesn’t match Romans’ ubiquitous interaction with living Greeks.We often think of Roman writers just reading Greek texts. But Romans encounter Greek art with words in a rich panorama of cultural experience. In Rome, the wealthy young would learn Greek language, poetry, rhetoric, philosophy from Greek teachers; rhetoricians and philosophers performed. Greek teachers in Rome radically changed Latin prose after Cicero. Students were noisy, often desperately keen; young Seneca pursued a Greek philosopher during his teaching breaks to beg for more philosophy. Eventually Rome instituted public libraries and performance-based literary competitions; in both, as in education, Greek was at least equal to Latin. In their villas outside Rome, Romans could read Greek works with tame (well, tameish) Greeks to explain and discuss; they made their libraries atmospheric, with inspiring busts of authors, mostly Greek.

Part-Greek cities in South Italy, like Naples, had competitions and plays in Greek. Romans found Athens filled with memories of past writers. From the late second century BC, inscriptions confirm, Roman youths would often spend a year there, hearing eloquent philosophical lectures. For oratory there was Asia (Turkey), and Rhodes, where disputes on rhetoric could turn nasty. All over the Greek world there were games, theatres, law-cases. Marseilles offered Greek culture in a safe environment, Alexandria (if you had permission) in a racy one.

As you might gather, space is crucial to the interaction of these literatures. Greek literature centres on Greece and Asia Minor. Cicero and others turn Athenian oratory into an oratory graphically located in Rome. Roman philosophy presents Greek ideas through Roman speakers in Italian villas. Roman historiography has its spatial centre in Rome; if Greek Polybius describes Hannibal invading Italy, Livy’s version for Romans has a scarier orientation. Latin mythological poetry can be set in Greece or Asia, but with a sense of distance, or move gradually to Italy, like Virgil’s Aeneid or Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Unlike later Italians exploiting Latin, Romans root their use of Greek in ethnic and spatial separation. Leading elephants over the Alps is no bad image for the perpetual challenge they confronted—but they relished it.

So a lot is involved in this example of impact outside one language and literature: language, identity, space, chronological construction, concrete experience. It should set us exploring beyond academic segmentations, in our own demanding adventures.

G. O. Hutchinson is Professor of Greek and Latin Languages and Literature at the University of Oxford. He is the author of Greek to Latin, which is a comprehensive attempt to consider the relationship between the two ancient languages.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Woodcut showing Cicero writing his letters [public domain]. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Greeks and Romans: literary influence across languages and ethnicities appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEdwin Battistella’s wordsLincoln’s rhetoric in the Gettysburg AddressThe Battle of Thermopylae and 300

Related StoriesEdwin Battistella’s wordsLincoln’s rhetoric in the Gettysburg AddressThe Battle of Thermopylae and 300

November 19, 2013

Edwin Battistella’s words

The annual Word of the Year selection by Oxford Dictionaries and others inspired me to an odd personal challenge last year. In November of 2011, about the time that Oxford Dictionaries were settling on squeezed middle as both the UK and US word of the year, I made a New Year’s Resolution for 2012: I would make up and tweet a word a day until 2013 rolled around. In classes, my students and I had been talking about how new words arise; we were disappointed with the mundacity of the textbook examples and inspired by examples like M.K. Anderson’s meg null and J.K. Rowling’s disapparitions, to say nothing of television neologisms like duhmazing and biggerer.

The new year arrived and I jumped in. As I made up my 366 words—dawndle, glind, bycrack, regretoric, laccalaureate, and more, I curated them (they were, after all, artisanal words). I checked various dictionaries, from the OED to the Urban Dictionary to make sure I wasn’t making up something that already existed. This daily practice of word making, which I came to think of as a kind of verbal yoga, taught me several things.

I discovered just how limited my vocabulary was. There were words I simply had not come across before, like thrawn, finick, tain, prehend, fetidity, libate, obclude, and vivify. You should look them up.

Odd puzzles presented themselves. Why do we say behead and unfriend, not dehead and defriend? (It’s got to do with matching up Anglo Saxon and Latin roots and prefixes.) Why do veterate and inveterate mean the same thing? (And why does it bother speakers less than the synonymy of regardless and irregardless?) If you catch up with something that is in a descending trajectory (like education funding), should the verb be to catch down?

The largest percentage of my new words were simple blends, the variety made famous by Lewis Carroll’s chortle. Thus dawndle (to sleep in) comes from dawn plus dawdle, glind (to dance while pressing together) from grind plus glide, regretoric (the language of apology) from regret plus rhetoric, and laccalaureate (someone just a few credits short at graduation) from lack plus baccalaureate. Many were clippings or backformations (like the verb bycrack, from bycracky) and prefixes and suffixes got a workout also. I learned that the noun form of something that needs to be fixed up is fixer upper, with two –ers, prompting breaker downer.

I had some delicious found words as well: the compound every-which-wayiness (which can refer to tangled hair or argumentation), the blend hangry (for the testiness that comes with low blood sugar), and rainmanliness (for the demonstration of savant-like abilities).

New words also come from our mishearings or misspeaking as when we read of “tight-nit groups,” wires “sauntered together,” or an athlete who “vouches never to lose again.” When I overheard the malapropism humbiliate for humiliate, I added it immediately. The meaning: “to humiliate oneself by being excessively humble.”

Some made-up words presented etymological or phonetic challenges: should the word texttumble (to stumble while walking and texting) be a blend of text plus tumble or text plus stumble (and why are stumble and tumble so darn close close anyway)? When I made up twalkers (those who text while walking), I discovered that it worked in print by not when spoken—to sounded too much like a New Yorker saying talkers.

Many of my words had flaws. To succeed new words much be more than just witty, they must capture a much-needed concept or the spirit of the moment. Some were too cute or too esoteric to be adopted. Do we really need to name the concept of flossolallia (the incoherent noises of someone speaking while flossing) or fratulence (the smell of a frat house or gym bag)?

Neology, I discovered, is harder than you think.

How does the Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year fare? Selfie has a lot going for it. It captures a new phenomenon (just check your Facebook or Instagram feeds for those). The root self itself is phonetically familiar and psychologically potent (who doesn’t think about themselves?). Grammatically self is both emphatic and reflexive, figuratively shouting ME, ME, ME! Yet, the –ie ending plays a sly joke because it is a diminutive (the ending that shows up in words like townie, groupie, foodie, doggie, birdie, auntie). And it’s rich with allusion to the near-homonym selfish. With this mix of usefulness, familiarity, potency, and a hint of irony, selfie could have a long future.

Edwin Battistella teaches at Southern Oregon University in Ashland, Oregon. His book Sorry About That: The Language of Public Apology will be published by Oxford University Press in May of 2014. His previous books include Bad Language: Are Some Words Better Than Others?, Do You Make These Mistakes in English?: The Story of Sherwin Cody’s Famous Language School, and The Logic of Markedness.

The Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year 2013 is ‘selfie’. The Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year is a word, or expression, that has attracted a great deal of interest during the year to date and judged to reflect the ethos, mood, or preoccupations of that particular year and to have lasting potential as a word of cultural significance. Learn more about Word of the Year in our FAQ, on the OUPblog, and on the OxfordWords blog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Word cloud via Wordle.

The post Edwin Battistella’s words appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesScholarly reflections on the ‘selfie’Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year 2013: ‘selfie’Lincoln’s rhetoric in the Gettysburg Address

Related StoriesScholarly reflections on the ‘selfie’Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year 2013: ‘selfie’Lincoln’s rhetoric in the Gettysburg Address

Why is wrongdoing in and by organizations so common?

Wrongdoing in and by organizations is a common occurrence. Ronald Clement tracked firms listed among the Fortune 100 in 1999 and found that 40% had engaged in misconduct significant enough to be reported in the national media between 2000 and 2005. A less systematic reading of the national media suggests that major instances of organizational wrongdoing have not subsided. In the last few months allegations of significant misconduct have hit Bloomberg LP (client privacy violation), Goldman Sachs (client deception), SAC Capital Advisors (insider trading), and JP Morgan (bribery). Furthermore, these major scandals fail to capture the many less sensational incidents of wrongdoing not reported in the national media. The New York Times article covering the JP Morgan bribery scandal indicated that JPM was at the same time the focus of investigations by at least eight federal agencies, a state regulator, and two foreign nations. It also indicated that since 2010, the SEC had filed 40 bribery cases against other companies and the Justice Department had filed bribery charges against another 60 firms.

Why is wrongdoing in and by organizations so prevalent? The dominant perspective on organizational wrongdoing does not provide a good answer to this question. It views wrongdoing as an abnormal phenomenon. It tends to characterize wrongdoers as extraordinary; as possessing outsized ambitions or bad values (e.g. as being greedy or having a callous disregard for others). It also tends to categorize wrongful behavior as aberrant, as obvious departures from accepted practice. Finally, received theory tends to attribute wrongdoing to a few out of whack structures, most commonly misaligned incentive systems or perverse cultures. If wrongdoers are outliers, if wrongdoing is clearly out of bounds, and if the causes of wrongdoing are few, then wrongdoing should not be so prevalent.

An emerging alternative perspective on wrongdoing offers insight into why wrongdoing is so common: it’s a normal phenomenon. It holds that wrongdoers are typically ordinary, possessing preference structures and values that do not set them apart from the rest of the population. Wrongdoing is often mundane, little different from accepted practice. In a competitive world, employees are forced to operate close to the line separating right from wrong (so as to not surrender competitive advantage). Once one is close, it does not take much to cross it. Finally, the alternative perspective attributes wrongdoing to a wide variety of structures and processes prevalent in organizations and without which organizations could not exist. Specifically, power structures, administrative systems, social influence processes, and technologies are integral to organizational efficiency and effectiveness — and each of these structures or processes can facilitate misconduct in and by organizations.

For example, almost all organizations have administrative systems that help employees figure out how they should react to specific work situations. These systems, which save time and facilitate coordination, include the explicit division of labor into specialized roles, the articulation of rules, and the formulation of standard operating procedures (Perrow 1972). But administrative systems can give rise to wrongdoing.

In the 1970s, Lee Iacocca instituted the “rule of 2000” when launching the Ford Motor Company’s Pinto subcompact car, giving clear direction to the car’s designers about how much it should weigh (no more than 2000 pounds) and cost to manufacture (no more than $2,000). The rule was intended to insure that the firm’s designers created a car that was suited for the market niche it was intended to fill, but it inadvertently led engineers to forego a number of safety measures that could have mitigated a problem that emerged in pre-production tests: the tendency of the car to erupt into flames when struck from behind at relatively low speeds. While these safety measures were relatively inexpensive (one would have entailed installing a rubber bladder in the gas tank at the cost of only about $11), they were sacrificed because they threatened to put the car over the specified $2,000 production cost limit.

More recently, Bloomberg LP instituted a rule stipulating that employees make contact with a client once a quarter to ask how they might serve the client better. The rule, which applied to Bloomberg’s reporters as well as its customer relations staff, was intended to deliver the message that all Bloomberg employees worked for the firm’s clients, regardless of whether their job designation placed them in immediate contact with clients. This rule went hand in hand with a flexible division of labor, manifested in the fact that Bloomberg reporters were trained in the use of the terminals that the firm leased to clients, geared to empower employees to meet a wide range of client needs. These rules made it natural for a reporter to use his training to take note of a client’s recent use of their terminal as a conversation starter in a phone call to solicit feedback from the client on how he might sever them better. The client, however, was aghast that the reporter had access to private information about his use of the terminal, which was contractually protected and if passed on through one of the reporter’s news stories, could compromise his competitive advantage.

If ordinary people can engage in organizational wrongdoing, if wrongful acts are often small deviations from accepted practice, and if the causes of wrongdoing are omnipresent, then it should come as no surprise that organizational wrongdoing is common. This observation holds an important implication for those seeking to curb organizational wrongdoing. Each of us (not just our subordinates, peers, and superiors) is at significant risk of engaging in misconduct. Thus, it is important for each of us to develop a better understanding of the forces that operate on us that can cause us to cross the line separating right from wrong.

Most importantly, MBA curricula should carve out a space in which students can explore this territory in a way that allows them to develop a better understanding of the forces that cause them to engage in misconduct and an appreciation of their susceptibility to those forces. At the present time, MBA curricula only tackle the problem of wrongdoing in and by organizations in the context of ethics courses. Unfortunately, I think these courses lead students to develop the exact opposite sensibility. They lead students to believe that they have elevated their moral character and in so doing become less likely to engage in wrongdoing. Thus, the most basic implication of the normal organizational wrongdoing perspective pertains to the way in which we view ourselves. It suggests that managers would do well to sensitize themselves to the decidedly grey area in which they operate and familiarize themselves with the many forces shaping their navigation of this terrain. If they can do this, they will not eliminate wrongdoing in their organizations, but they will give themselves a fighting chance of staying on the right side of the line.

Donald Palmer is Professor of Organizational Behavior at the Graduate School of Management, University of California, Davis. He is the author of Normal Organizational Wrongdoing: A Critical Analysis of Theories of Misconduct in and by Organizations. He has conducted quantitative empirical studies on corporate strategy, structure, and inter-organizational relations and qualitative studies of organizational wrongdoing.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: White collar criminal under arrest. © AlexRaths via iStockphoto.

The post Why is wrongdoing in and by organizations so common? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesScholarly reflections on the ‘selfie’Lincoln’s rhetoric in the Gettysburg AddressPlace of the year 2013: Spotlight on Syria

Related StoriesScholarly reflections on the ‘selfie’Lincoln’s rhetoric in the Gettysburg AddressPlace of the year 2013: Spotlight on Syria

Scholarly reflections on the ‘selfie’

When Oxford Dictionaries chose ‘selfie’ as their Word of the Year 2013, we invited several scholars from different fields to share their thoughts on this emerging phenomenon.

“’Selfies in science are way cool!,’ reads the status update that accompanies a series of not-quite focused, off-centered selfies that made its way to my Facebook page recently. In successive frames are images of a blurry young woman with a series of tired, puzzled, and smiling high school students in the background. For the participants, these selfies are at least a little about irony and absurdity: as they’re taken in the most ordinary of school classroom settings, they call into question the very idea that photography — and even selfies — are supposed to be about capturing something meaningful and someone special or important. And in the bureaucratic setting of the public school, the images take on a further irony as they are evidence of young people acting out of their own agency in a setting not of their making. Part of the fun is in knowing that this is an inappropriate place to take a selfie. Selfies like this are about awareness of our own self-awareness. They can create a moment of playfulness that helps us to recognize the truth about living in culture that celebrates the individual and the spectacle. They can help us to deal with the absurdity of the ordinary in the face of all of that expectation of fame and spectacle. They can be disruptive of expectations. And sometimes, even the blurriest of selfies can help us to see ourselves, and the specialness of our own lives, more clearly.”

— Lynn Schofield Clark, Director of the Estlow International Center for Journalism and New Media at the University of Denver and author of The Parent App: Understanding Families in the Digital Age

“A recent trip to Stonehenge had me cringing as I watched visitors to the site posing for selfies in self-absorbed abandon beside the ancient monument. Did they feel that the intriguing thing about Stonehenge was their own presence there? Maybe I’m not alone in my mixed feelings about the message that selfie-obsession sends about the self-documentarian. Research shows that there’s a direct relationship between how many selfies you share on social media and how close your friends feel to you. There are many possible explanations for this finding, including the self-portrait artist looking or being self-absorbed or lonely or lacking the social skills to know when to say when.”

— Karen Dill-Shackleford, Director of the Media Psychology Doctoral Program at Fielding Graduate University and editor of The Oxford Handbook of Media Psychology

“Theory of mind may be foremost among the factors that set people apart from other species. Yet, to know that others have a mind (full of beliefs, expectations, emotions, perceptions — some the same and some different from one’s own) is not enough to be really successful as the social animal. Missing is the wish of the 18th century Scottish poet Robert Burns: ‘O wad some Pow’r the giftie gie us / To see oursels as others see us!’ It was his humorous way to point out that avoiding vanity, hubris, embarrassment, etc., depends on imagining oneself from another’s point of view, and to note that our sensory apparatus is pointed away from “the self,” poorly positioned to help much with that. The selfie (an arm’s length close-up self-portrait) photograph is a way to control others’ images of us, to get out in front of their judgments, to put an image in their heads with purpose and spunk. Others’ judgments are no longer just their own creation, the selfie objectifies the self, influences others’ thoughts. And, since the selfie is one’s own creation, it also affords plausible deniability; it isn’t me, it’s just one ‘me’ that I created for you.”

— Robert Arkin, Professor of Psychology in the Social Psychology program at The Ohio State University and editor of Most Underappreciated: 50 Prominent Social Psychologists Describe Their Most Unloved Work

“In the age social media where consumer brands seek deep consumer engagement, the human race is following suit. We now all behave as brands and the selfie is simply brand advertising. Selfies provide an opportunity to position ourselves (often against our competitors) to gain recognition, support and ultimately interaction from the targeted social circle. This is no different to consumer brand promotion. The problem is, like most advertising done on the cheap and in haste, the selfie can easily backfire making your brand less desirable.”

— Karen Nelson-Field, Senior Research Associate, Ehrenberg-Bass Institute for Marketing Science, University of South Australia, and author of Viral Marketing: The Science of Sharing

“From a social psychological standpoint, the selfie phenomenon seems to stem from two basic human motives. The first is to attract attention from other people. Because people’s positive social outcomes in life require that others know them, people are motivated to get and maintain social attention. By posting selfies, people can keep themselves in other people’s minds. In addition, like all photographs that are posted on line, selfies are used to convey a particular impression of oneself. Through the clothes one wears, one’s expression, staging of the physical setting, and the style of the photo, people can convey a particular public image of themselves, presumably one that they think will garner social rewards.”

— Mark R. Leary, Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience at Duke University and author of The Curse of the Self: Self-Awareness, Egotism, and the Quality of Human Life and editor of Interpersonal Rejection

“‘My friends won’t stop sending selfies on Snapchat even though I already see them all on Instagram and Facebook’ according to the sender of this Snapchat-post. Are all selfies the same? I don’t think so. There is quite a difference in taste and message between selfies on various social media platforms. Facebook selfies tend to be the most ordinary self-portraitures; they are pictures posted by people who want to look normal, happy, nice. Instagram is for ‘stylish’ selfies or ‘stylies’. On Instagram, you don’t portray yourself; you paint a desirable persona. The apex of good taste may not be a self-portrait but an artistic picture of your most coveted object, such as an expensive bracelet on your wrist or four pairs of shoes representing you, your trendy husband, and your two adorable kids. Snapchat selfies are more like funny postcards: look at me, see how waggish I am, how abrasive I look, you’re not going to catch me in a snapshot. Snapchat selfies are meant to fade away like a dream as they vanish in less than ten seconds. So each selfie peculiarly reflects the flair and function of the platform through which it is posted, perhaps even more so than its sender’s taste. The medium is a big part of the message.”

— José van Dijck, Professor of Comparative Media Studies at the University of Amsterdam and author of The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media

“Selfie is an excellent Word of the Year. That -ie ending echoes hundreds of predecessors, and gives it a familiarity, succinctness, and colloquial appeal that’s somehow lacking in such coinages as selbstportrait and autoportrait. It’ll be truly multilingual by the end of the month.”

— David Crystal, writer, editor, lecturer and broadcaster on language, and most recently co-author of Wordsmiths and Warriors: The English-Language Tourist’s Guide to Britain

The Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year 2013 is ‘selfie’. The Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year is a word, or expression, that has attracted a great deal of interest during the year to date and judged to reflect the ethos, mood, or preoccupations of that particular year and to have lasting potential as a word of cultural significance. Learn more about Word of the Year in our FAQ, on the OUPblog, and on the OxfordWords blog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: (1) Young people taking picture of themselves with camera – selfpic series. © Lighthaunter via iStockphoto. (2) Selfies on Snapchat image courtesy of José van Dijck.

The post Scholarly reflections on the ‘selfie’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOxford Dictionaries Word of the Year 2013: ‘selfie’Lincoln’s rhetoric in the Gettysburg AddressLooking forward to AAR/SBL 2013

Related StoriesOxford Dictionaries Word of the Year 2013: ‘selfie’Lincoln’s rhetoric in the Gettysburg AddressLooking forward to AAR/SBL 2013

Looking back: ten years of Oxford Scholarship Online

Oxford Scholarship Online (OSO) launched in 2003 with 700 titles. Now, on its tenth birthday, it’s the online home of over 9,000 titles from Oxford University Press’s distinguished academic list. To celebrate OSO turning ten, we’ve invited a host of people to reflect on the past ten years of online academic publishing, and what the next ten might bring.

By Sophie Goldsworthy

Back in 2001, there was a whole host of reference products online, and journals were well down that digital road. But books? Who on earth would want to read a whole book online? When the idea that grew into Oxford Scholarship Online was first mooted, it faced a lot of scepticism, in-house as well as out.

We were pretty sure we knew how monographs were used at that stage, and by whom. Scholars (and the occasional student) took them down from the library shelves and read them cover to cover. Sometimes not very many scholars, and not very many libraries, but then that was monograph publishing for you. At a time when print runs were dwindling and every conference featured a ‘death of the monograph’ panel, it was widely accepted that demand was declining and there wasn’t a great deal that could be done, bar continue to focus on publishing the very highest quality scholarship.

But we persisted, talking to librarians and others about how this content might work best for them online — how they’d want to buy it, and use it — and beginning the process of rethinking it for an online space. One important early decision was the adoption of standards established for journal content, and the commissioning of tens of thousands of abstracts and keywords for every book and chapter which would be pushed out to search engines and online aggregation services to ensure the content was discoverable. And so we started out, launching in 2003 with four busy publishing areas — philosophy, economics and finance, religion, and political science — and some 700 titles, making many of the most important books published by the Press accessible online for the first time. OSO doesn’t only keep pace with our new print publishing, releasing cutting-edge scholarship by today’s authors, but has opened many seminal works up to new readers: works such as Derek Parfit’s Reasons and Persons, Will Kymlicka’s Multicultural Citizenship, Chris Wickham’s Framing the Middle Ages, Ray Jackendoff’s Foundations of Language, Henry Chadwick’s The Church in Ancient Society, Peter Hall and David Soskice’s Varieties of Capitalism, and Martha Nussbaum and Amartya Sen’s The Quality of Life.

Looking back over articles written about Oxford Scholarship Online in its early years, it’s cheering to note that most of the future plans we had in mind have come to fruition. We’ve extended the site to cover the full range of our academic publishing, taking it into law, medicine, and the sciences, as well as the humanities and social sciences, and in the process building to around 9,250 titles in 20 subjects live on the site today. We’ve adopted flexible business models, adding purchase models to help librarians curate their digital collections, and most recently allowing customers to design their own tailor-made collections of titles, making OSO a practical tool for the creation of online course packs and reading lists. We’ve also opened the platform up to the wider community, to help other publishers take their content online, and are excited to be working with so many leading university presses from Yale, Chicago, Stanford, MIT, California, Edinburgh, Manchester, and elsewhere.

But we’ve also developed Oxford Scholarship Online in ways we couldn’t have imagined at that stage, optimizing the site for use on mobile devices (if we couldn’t imagine anyone reading a monograph online, we certainly couldn’t conceive of them dipping into one on a phone), adding user personalization, more intuitive search tools and better linking, and ever more ways of sharing ideas and references with fellow students or colleagues. We are in continual dialogue with librarians and users, as well as observing the way people use the content on the site, which means we can tailor content and functionality to meet changes in research habits, and OSO continues to evolve in response to users’ suggestions and needs.

Most excitingly, for me, as our business is about dissemination, is the fact that the site has breathed new life into the monograph — that gloomy monograph, whose health has been subject to so much speculation over the years. OSO allows us to make this authoritative content accessible in places our print books failed to reach, from specialist institutions, such as seminaries, to universities that haven’t traditionally been able to build large collections of scholarly works, for economic or political reasons. And by using the XML to unpack the scholarship these books contain we’ve been able to create intelligent links, not only within the site itself and the rest of the Oxford portfolio but also across the wider web, letting our users plot their own research journeys through book chapters and journal articles, and out into reference look-ups or a quick dalliance with an altogether different discipline. At its most basic, OSO has taken those neglected monographs back down from their library shelves, dusted them off, and opened them up for all kinds of readers, wherever in the world they happen to be.

So what might it look like in the next ten years? The bundling of print and online is likely to feature sooner rather than later, as we recognise that readers like to use the different formats in complementary ways. The granularity may be extended to offer the reader a single book, even a single chapter. The site might host ancillary and multimedia content — the kind of thing that adds depth and context to a research project but won’t fit between the covers of a print book — or provide a space for open review and community hubs, building peer discussion into the evolution of a project. We might create other content specifically for the online space, or make it freely available on an open access model. Ultimately, Oxford Scholarship Online will continue to grow and to adapt, reflecting the ever-changing nature of the digital environment, and the fact that it has allowed us to get closer to our customers and readers than ever before, learning how our content is really used for perhaps the first time in our many-centuries-long history.

Sophie Goldsworthy is the Editorial Director for OUP’s Academic and Trade publishing in the UK, was Project Director of Oxford Scholarship Online from 2005 to 2010, and continues to be involved with the site. Read her previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only media articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Looking back: ten years of Oxford Scholarship Online appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA Halloween reading list from University Press Scholarship OnlineThe African CamusShanghai rising

Related StoriesA Halloween reading list from University Press Scholarship OnlineThe African CamusShanghai rising

Lincoln’s rhetoric in the Gettysburg Address

Perhaps no speech in the canon of American oratory is as famous as the “Dedicatory Remarks” delivered in a few minutes, one hundred and fifty years ago, by President Abraham Lincoln. Though school children may no longer memorize the conveniently brief 272 words of “The Gettysburg Address,” most American can still recall its opening and closing phrases. It has received abundant and usually reverent critical attention, especially from rhetoricians who take a functional view of discourse by always asking how an author’s choices, deliberate or not, achieve an author’s purposes. Of these many studies, the greatest is Garry Wills’s Lincoln at Gettysburg (Simon & Schuster, 1992). It leaves little unsaid about the genre, context, and content of the speech, or about the grandeur and beauty of its language, the product of Lincoln’s long self-education in and mastery of prose composition. But while the rhetorical artistry of Lincoln’s speech is uncontestable, it can also be said that its medium, the English language, was and is an instrument worthy of the artist. Among all the ways that this speech can be celebrated for its author, its moment in history, and its lasting effects, still another way is as monument to the resources of the English.

In its amazing lexicon, the largest of any living language in Lincoln’s time or ours, English is, thanks to the accidents of history, a layered language. The bottom layer, containing its simplest and most frequently used words, is Germanic. The Norman invasion added thousands of Latin words, but detoured through French to create, according to eighteenth-century British rhetoricians like Hugh Blair, a distinctive French layer in English. Throughout its history, but peaking between 1400 to 1700, words were stacked on directly from Latin and Greek to form a learned and formal layer in the language. (English of course continues borrowing from any and all languages today.) It is therefore not unusual in synonym-rich English to have multiple ways of saying something, one living on from Anglo-Saxon or Norse, another a French-tinctured option, and still another incorporated directly from a classical language. Consider the alternatives last/endure/persist or full/complete/consummate. Of course no English speaker would see these alternatives as fungible since, through years of usage, each has acquired a special sense and preferred context. But an artist in the English language like Lincoln understands the consequences in precision and nuance of movement from layer to layer. He chose the French-sourced endure at one one point in his Remarks and the Old English full at another.

The only known photograph of President Lincoln giving his Gettysburg address on November 19, 1863. Public domain via United States Library of Congress.

Lincoln’s awareness of this synonym richness is also on display in his progressive restatement of what he and his audience cannot do at Gettysburg: they cannot dedicate — consecrate — hallow the ground they stand on. All three verbs denote roughly the same action: to set apart as special and devoted to a purpose. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first two came into English in the fourteenth century as adjectives and in the fifteenth as verbs, both formed from the past participle of Latin verbs. The second of these, however, has a twelfth century French cognate, consacrer, in use when French was the language of England’s rulers. The third word, hallow, comes from the Old English core and carries the strongest association of a setting apart as holy. Lincoln’s progression then goes from the Latinate layer to the core, a progression in service of the greatest goal of rhetorical style – to amplify, to express one’s meaning with emotional force. Lincoln’s series of synonyms, simply as a series, distances the living from the dead, but as a progression it rises from the formulaic setting apart with words of dedicate, to the making sacred as a church or churchyard are of consecrate, to the making holy in martyrdom of hallow. Forms of consecrate and dedicate appear again, but hallow only once, mid-speech.

Lincoln’s deftness in word choice is matched by his artistry of sentence form. Among the often-noticed features of Lincoln’s sentence style is his fondness for antithesis. This pattern is hardly Lincoln’s invention. It is one of the oldest forms recommended in rhetorical style manuals and in Aristotle’s Topics as the purest form of the argument from contraries. The formally correct antithesis places opposed wording in parallel syntactic positions: little note nor long remember/ what we say here // never forget/ what they did here.

A figure like antitheses can be formed in languages that carry meaning in inflectional endings as well as in English where word order is crucial, but other figures do not translate as easily. For example, the figure polyptoton requires carrying a term through case permutations. Had Lincoln been writing in Latin, the great concluding tricolon of the speech could have been the jangle populi, populo, populo, the genitive of the people, the ablative by the people, and the dative for the people. But English requires prepositional phrases to do what Latin does in case endings, and in this case a constraint yields a great advantage in prosody. For once listeners pick up the meter of the first and second phrase, they are prepared for the third and their satisfied expectation is part of the persuasiveness of the phrasing.

In all languages, rhetorical discourse springs from situations fixed in time and space. It responds to pressing events, addresses particular audiences and is delivered in particular places that can all be referred to with deictic or “pointing” language linking text to context. Much of the Gettysburg Address defines its own immediate rhetorical situation. Lincoln locates “we,” speaker and audience, on a portion of a great battlefield in a continuing war, and he dwells on the immediacy of this setting in space and time by repeating the word here six times (a seventh in one version, an eighth in another). This often-noted repetition is critical in Lincoln’s purpose. The speech opens in the past and closes in the future, but most of it is in the speaker and listeners’ “here” and “now” so that, held in that place and moment, a touching, a transaction can occur between the dead who gave their last full measure of devotion, and the living who take increased devotion from them.

The Gettysburg Address is profoundly the speech of a moment in our history and it is altogether fitting and proper to remember its anniversary. Yet whenever it is read or spoken it seems to belong to that moment. How is that possible? Because languages like English not only express the situation of an utterance, they also recreate that situation when the language is experienced anew. In this way, read or heard again, the Address once more performs a transaction between America’s honored dead, its author now included, and its living citizens affirming their faith in government of, by and for the people, repeating its language into the future.

Jeanne Fahnestock is Professor Emeritus, Department of English, the University of Maryland. She is the author of Rhetorical Style (Oxford, 2011), Rhetorical Figures in Science (Oxford, 1999), and co-author with Marie Secor of A Rhetoric of Argument (McGraw-Hill, 2004).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Lincoln’s rhetoric in the Gettysburg Address appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesClimbing Pikes Peak 200 years agoFrom Boris Johnson to Oscar Wilde: who is the wittiest of them all?An interlude

Related StoriesClimbing Pikes Peak 200 years agoFrom Boris Johnson to Oscar Wilde: who is the wittiest of them all?An interlude

What makes music sacred?

I’ve spent a lot of time in churches throughout my life. I was baptized in the Episcopal Church, raised Methodist, and am a converted Catholic. I’ve worked in Presbyterian, Episcopalian, Lutheran, and Methodist churches and spent a summer in Eastern Europe singing in a Romanian Orthodox church. I’ve experienced a wide variety of religious music — from crazy arm-raising rock band style to lung-clogging incense-burning chants — in different parishes within each of these denominations. While I have my own musical preferences, over and over again I ask myself, is this music sacred? And if so, what makes it sacred?

I am by nature a traditionalist and my inclination is to argue that the so-called more “traditional” style of music in worship is more sacred. I’ve sung Handel’s Messiah with the New York Philharmonic multiple times and I’ve sung Our God is an Awesome God with various local church praise bands more times than I care to count. Every time I sing Messiah I love it more, and every time I sing Our God is an Awesome God I feel like I’ve sold a piece of my musical soul. But I cannot discount the number of people who seem truly moved by the experience of the latter. There are people all over the world who advocate for this more “contemporary” style of worship, and much as I hate to admit it, it seems to be effective. People come to church and do their best to live out a Christian life because of a style of music that they feel connects them with God. Anything that connects people with the divine has merit, but I still wonder, is it sacred?

It might first be important to establish a definition of the word sacred. The Catholic Church makes its definition of sacred music pretty clear, stating in Musicam Sacram that music for the mass must “be holy, and therefore avoid everything that is secular.” It goes on to say that sacred music must also be “universal in this sense.”

For many people, something that is special and deeply meaningful is sacred. Mary McDonough argues, that the music of U2 and Pink Floyd are sacred because they brought her a great deal of comfort after her father’s death. So while the music of U2 and Pink Floyd were sacred to Ms. McDonough because of her own personal experience, it fails to meet the Catholic Church’s criterion. While I like the music of both bands, I have not had any kind of sacred experience with either of them, so in that sense, the music is not universal; it is specific to one individual’s experience. It also most certainly does not fit the first half of the definition that sacred music should avoid anything that is secular.

I think it’s fair to say that the music has to be about God. The word sacred by definition must have to do with God or the gods, and most of the music of the contemporary worship movement fits this criterion. Perhaps then we should consider the purpose of sacred music: to function as part of the mass or service, most often as a part of worship. Worship derives from Old English weorthscipe ‘worthiness, acknowledgement of worth’. So if sacred music is intended to worship God, then such music must be of worth.

Most of the music that fits into the contemporary church music genre has the same structure and most of the songs sound alike. You’ll find I, IV, and V chords pervasive throughout most of it with maybe a vi chord or an added 7th or 9th occasionally. It is by nature accessible—not particularly difficult or innovative. And this is why it appeals to the masses. But is it of high worth? Yes, if you define worth as something that has the potential to be meaningful to someone (hence the Pink Floyd U2 argument). No, if you define worth as something that is rare or unique and has a degree of innovation.

I am not a traditionalist for the sake of tradition. I think it’s important to adapt to the times and to constantly rethink past ways of doing things. After 10 years of thinking about this question, I still don’t have a concrete answer. I am not prepared to say that current popular trends in church music are not sacred. At the risk of offending some of my former colleagues, I am prepared to say that I do not think that music of the contemporary worship genre is as innovative or of as high quality as the music of Bach or Handel or even slightly more modern composers like Howells. But I see and understand the argument for both styles of music, regardless of my own tastes. Ultimately, I believe it is important for all church musicians to consistently ask questions of the music they choose. Is it about God? Is it going to connect others with God? Is it of worth? What makes something of worth? And lastly, is it sacred?

Mezzo-soprano, Laura Davis, is a singer, conductor, and voice teacher. She holds a Master of Music degree in Voice Pedagogy and Performance from the Catholic University of America and a Bachelor of Music degree in Sacred Music from Westminster Choir College. Davis has held positions in numerous churches throughout the past 10 years, most recently in the Baltimore/Washington United Methodist Church where she served as the Director of Music from 2009-2013 for the largest church in the conference. Davis has recently returned to her home state of Colorado where she is in the process of opening a voice studio committed to teaching authentic artistry. Read her previous blog post on yoga and voice.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Antique Building Cathedral Chapel Christian Church. Photo by PublicDomainPictures, public domain, via Pixabay.

The post What makes music sacred? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories“God Bless America” in war and peaceRussian choral music: the joy of discovering ‘unknown unknowns’Looking forward to AAR/SBL 2013

Related Stories“God Bless America” in war and peaceRussian choral music: the joy of discovering ‘unknown unknowns’Looking forward to AAR/SBL 2013

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers