Oxford University Press's Blog, page 873

November 27, 2013

The indiscipline of discipline, or, whose ‘English’ is it anyway?

It is a great educational paradox that the nature of one of the UK’s key subjects is both ill-defined and poorly understood. What counts as ‘English’ is contested at all levels, from arguments about the literacy hour at primary level, through the relative importance of English Language and English Literature at GCSE level, to the introduction of a new A Level in Creative Writing, and the ‘confirmatory consultations’ recently conducted over the reform of AL and GCSE English syllabi.

What ‘English’ is, then, carries a good deal of political freight, with powerful interests coming down on either side in various debates. Different versions of the subject get pitted against each other in often unhelpful ways: the Russell Group, for instance, includes English Literature but not English Language in its suite of ‘facilitating subjects’, a decision which may have unseen consequences for boys, who more frequently elect to do the former (English Lit, on the other hand, is increasingly a female pursuit, at undergraduate level at least). It would seem unlikely that Creative Writing will be embraced as a facilitating subject: ‘it’s more like performing arts or media’ one Russell Group academic pronounced at a recent conference on the new A Levels, a perception which might also have sociological consequences if the Creative Writing AL finds a more welcoming embrace in the classrooms of Further Education colleges than it does in those of the top public schools.

Underlying all these hierarchies are various other presuppositions: that English Literature is harder or more rigorous than English Language or Creative Writing (a perception not necessarily shared by students of those versions of ‘English’ in HE); or that English Literature alone exposes the student to a Great Tradition of the best that has been thought and said: such Leavisite, Arnoldian assumptions, and the models of authority which accompany them, still inhabit recent consultatory documents issuing from the Department for Education. But this begs the question of what it is that English Literature teachers and students really do in their HE English Literature classes, and whether the nature of that enterprise changes radically according to who we teach and what we teach them. Is a lecturer teaching Paradise Lost at a Russsell Group university really doing something qualitatively different from a lecturer holding a seminar on Usula Le Guin’s Tales from Earthsea in an inner-city new university? Of course, there may be local differences between individual approaches, even different pedagogies or attitudes to the canon: most people would teach a class of five differently than they would one of thirty-five, and these two hypothetical teachers might hold very different views about what should count as the object of inquiry in an ‘English’ degree. These local differences aside, however, are there fundamental differences in what the students learn to do with these texts in their respective seminars when they study them? And second, if sociological factors such as gender, race and class effect the choices students make at A Level (English Literature at HE level is now a largely white, middle-class discipline, as well as a female one) how do such factors manifest themselves in classrooms where students from different backgrounds encounter the methods and approaches of ‘our’ discipline?

With the help of educationalists, I’ve been pursuing these questions though a novel method, videotaping English Literature seminars in institutions with very different cultures, student bodies, and access to resources, trying to uncover what exactly is taught and learned in UK HE English degrees so as to delve a little deeper into some of the old, often theoretical, questions that beset the discipline of ‘English’. Take canonicity and the canon debates, for instance. Is it true, as some critics would have it, that what we study is of such fundamental importance that it trumps almost everything else, and that the cultural landscapes in which we situate those artefacts generate qualitatively different kinds of knowledge (‘it does not do to compare just anything with anything, no matter when and no matter where’ as Jean-Marie Carré put it in 1951). Or is there no such thing as a ‘legitimate’ comparison? Could a student from a middle-ranking university who juxtaposes a contemporary selection of short stories with the Roger’s Profanisaurus someone gave her for her birthday which she ‘just reads when [she’s] bored’ be pursuing an interpretative strategy as intellectually sound, and as potentially productive of meaning as the student from a prestige institution who compares an Old English text with an early modern portrait hanging in his college picture gallery? What is more important, the artefacts we compare with each other, or the act of comparing them? Or, to take a different example, are the strategies we utilise equally available to students who may hail from very different environments, arriving at HE with different habiti, and very different concepts of what is of value. Close reading, for example, however contested it has been in the past, remains a strategy intrinsic to the pedagogical landscape of English Literature. It’s a strategy that presupposes open-endedness, and values the sense of a proliferation of meaning, countering presumptions of singular and immediate legibility and troubling convictions of an accessible, and finite, bottom line. How comfortably does that strategy, and the values it implies, sit with students inducted into HE via an instrumentalist ethos that valorises instead measurement, quantification, particular kinds of transparency and the apprehension of immediately visible and demonstrable educational and economic outcomes and bottom lines?

My research juxtaposes theoretical questions about English Literature with real, mundane, day to day classroom discussions, and draws the conclusion that the apparently inconsequential minutiae of what happens in the course of the seminar discussion can tell us a good deal about what we do, about how we do it, and, importantly, why it matters.

Susan Bruce is Professor of English and Head of the School of Humanities at Keele University. Her publications include Three Early Modern Utopias (Oxford World’s Classics, 1999), King Lear: A Reader’s Guide (Palgrave Macmillan, 1997) and, with Valeria Wagner, Fiction and Economy (Palgrave Macmillan, 2007). She is the author of the paper ‘Money Talks: Classes, Capital, and the Case of Close Reading in a seminar on The Merchant of Venice’, which examines the way in which University English is ‘produced’ through ordinary seminar discussions occurring across the diverse range of UK Higher Education Institutions. It is published in the journal English.

English is an internationally known journal of literary criticism, published on behalf of The English Association. Each issue contains essays on a wide range of authors and literary texts in English, aimed at readers within universities and colleges and presented in a lively and engaging style.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Teenage students studying in classroom. By monkeybusinessimages, via iStockphoto.

The post The indiscipline of discipline, or, whose ‘English’ is it anyway? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesNose to nose with Laurence Sterne and Tristram ShandyNational Bible Week: Learning with Don Kraus, OUP Bible editorRaising the Thanksgiving turkey

Related StoriesNose to nose with Laurence Sterne and Tristram ShandyNational Bible Week: Learning with Don Kraus, OUP Bible editorRaising the Thanksgiving turkey

November 26, 2013

R v Hughes and death while at the wheel

In their judgement in the case of R v Hughes [2013] UKSC 56, the UK Supreme Court has issued guidance which, arguably, negates the offence of s. 3ZB of the Road Traffic Act 1988 of causing death by being unlicensed, uninsured, or disqualified from driving. In a case since this judgement the CPS stated they considered this offence as written ‘no longer existed’ due to the Hughes decision.

The Road Safety Act 2006 introduced a ‘new’ offence of causing death by being unlicensed, uninsured, or disqualified from driving. There was ambiguity in the wording as it says ‘causes the death of’ — how do you cause the death of someone by being uninsured? However, Parliament’s made clear their intention for this offence in a response to the consultation process when it said:

‘The standard of driving could be perfectly acceptable. For example, this offence could bite on a driver who was driving very carefully, but a child ran into the road and was killed. The offence will apply where ‘but for’ the defendant’s car being on the road the person would not have been killed.’

This was a strong deterrent to those who choose to drive without passing a driving test, not insuring their vehicle, or driving when the courts had disqualified them.

This was certainly the stance I, and other road death senior investigating officers, took. In 2009 I charged someone with this offence, her driving was unimpeachable but she had driven in the guilty knowledge she had no driving licence. She had a head on collision with a young man (17-years-old) who was on the wrong side of the road. His untimely death was entirely caused by his own poor driving. The unlicensed driver did not go to prison, but could have. Did I feel sorry for her? Yes, I did have a degree of sentiment, but this was tempered by the fact she had made the conscious, culpable decision to drive knowing she had never passed a driving test, and therefore not shown her driving was to the requisite standard. I also had a great deal of sympathy with the family of the dead boy, and their view was that there ought to be an aggravated form of the offence of driving other than in accordance with a licence, even accepting their son’s responsibility for his own death.

My view was supported by the courts in R v Williams [2010] EWCA Crim 2552. The Court of Appeal, Criminal Division held that as a matter of statutory construction, fault, or another blameworthy act on the part of the defendant was not required to prove an offence of causing death by driving without insurance and without a licence, pursuant to s3ZB.

However in Hughes the Supreme Court have indicated that this is an incorrect approach to this offence and that by the construction of the statute using the phrase ‘causes…death…by driving’ implies some fault in driving other than not having a licence et al. This view seems to be contrary to the wishes of Parliament; however their Lordships stated ‘it would plainly have been possible for Parliament to legislate in terms which left it beyond doubt that a driver was made guilty of causing death whenever a car which he was driving was involved in a fatal accident, if he were at the time uninsured, disqualified or unlicensed’ I believe that’s exactly what Parliament intended by not adding any relationship to driving standards, they envisaged an offence of strict liability.

It is clear from the judgement that the Law Lords felt uncomfortable finding someone guilty of a ‘homicide’ offence, as they put it,

‘for failing to pay his share of the cost of compensation for injuries to innocent persons, he is indicted and liable to be punished for an offence of homicide, when the deceased, Mr Dickinson, was not an innocent victim and could never have recovered any compensation if he had survived injured’.

These words will not receive support from the family of anyone killed by an uninsured driver whatever the causation. Their Lordships miss the point, Mr Hughes and others should not be driving, full stop.

They were also concerned with no insurance being an absolute offence as this would capture those with no insurance through administrative error. With due respect this is a moot point, these cases are rare, what is not rare is the large number of those who choose to drive whilst the law says they shouldn’t; nor is it rare that these drivers are involved in collisions where people die.

The difficulty of the ratio of the decision in Hughes is that their Lordships made it clear that, in their view, this offence:

‘requires at least some act or omission in the control of the car, which involves some element of fault, whether amounting to careless/inconsiderate driving or not, and which contributes in some more than minimal way to the death…’

This effectively negates the section brought in by Parliament and replaces it with a ‘new’ offence that is somewhere between blameless and careless driving (with the required documentation element). Their Lordships suggest ‘driving at 34mph in a 30mph limit’ and ‘slightly below legal limit of tyre wear’ would encapsulate their view. As an experience road death investigator both of these would be virtually impossible to prove as contributory factors to the collision; and for sure the CPS would be unlikely to proceed.

This leaves this offence well and truly in limbo for now; if not in need of statutory intervention.

I cannot help but wonder if the Supreme Court would have had a different view in Hughes had the defendant been a recidivist disqualified driver and the other driver not been driving under the influence of heroin? Emotions aside, people without driving qualifications should not have been on the road and I fear their Lordships have weakened a vital deterrent.

John Watson is a retired police Inspector with over 25 years’ police service and is a qualified police trainer and assessor. He has several years’ experience in writing multiple-choice questions that have been used for in-force training. He is an author of the Blackstone’s Police Q&As.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Uk police vehicles at the scene of a public disturbance. © jeffdalt via iStockphoto.

The post R v Hughes and death while at the wheel appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTransitional justice and international criminal justice: a fraught relationship?National Bible Week: Learning with Don Kraus, OUP Bible editorThe bin of plenty

Related StoriesTransitional justice and international criminal justice: a fraught relationship?National Bible Week: Learning with Don Kraus, OUP Bible editorThe bin of plenty

A journey through 500 years of African American history

This fall, my colleagues and I completed work on Henry Louis Gates, Jr.’s documentary series The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross, which began airing on national PBS in October. In six one-hour episodes, the series traces the history of the African American people, from the 16th century—when Juan Garrido, a free black man, arrived on these shores with Hernando Cortes, searching for gold—to today, when our nation has re-elected its first black president, yet still struggles with staggering racial disparities in education, poverty and incarceration rates.

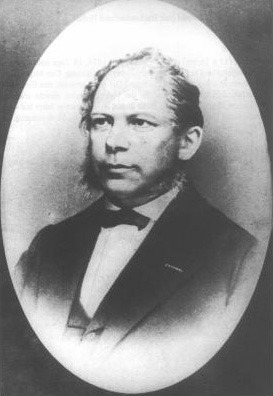

Henry Louis Gates Jr. Photo by Jon Irons, Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

At first, the task of winnowing five hundred years of African American history down to six hours of television seemed like an insoluble conundrum. How could one documentary series possibly cover this vast sweep of history?

The premise advanced by Gates, the series’ creator, executive producer and host, was deceptively simple: to tell this history from an African American perspective, depicting the agency and unfathomable resilience of a people brought here against their will—who ended up defining this country, its society and its culture, against often insurmountable odds.

We began by seeking the counsel of our advisory board—a host of the field’s most eminent historians and scholars. With their guidance, we sifted through endless lists of stories, each of which seemed more essential than the last. The scholars’ views as to which stories and individuals deserved priority were often at odds with one another. As television producers, we relish probing conflicting ideas, but we needed to find a path through the jungle of scholarly debate. Fortunately, the guiding light came from the stories themselves.

As we waded through five centuries of history, we were constantly struck by how relevant many of the stories still felt, and how powerfully they resonated with what we read about in the news every day. The deeper we delved into our story research, the more we were reminded of William Faulkner’s oft-quoted words: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

While exploring the well-known biography of Harriet Tubman, for instance, we simultaneously discovered the remarkable story of Terrence Stevens, a Harlem resident unjustly sent to prison in 1992, at the height of the War on Drugs. After serving almost a decade in unbearable conditions (Stevens suffers from muscular dystrophy, and received no specialized care during most of his time in prison), he emerged with a fierce determination to help children who had lost their parents to incarceration. His efforts to dismantle the cradle-to-prison pipeline, one individual at a time, recall Tubman’s courageous forays to rescue individuals from slavery in the 1850s. The stubborn efforts of both Tubman and Stevens evoke W. E. B. Du Bois’ still-potent admonition: “There is in this world no such force as the force of a person determined to rise.”

Historical parallels cropped up throughout our work on the series. While studying the disappointing fate of black elected officials at the end of Reconstruction, day by day we observed the “birthers” and opponents of “Obamacare” acting out scripts that could have been written in the 1880s—whether or not they realized it consciously. (We were deep into production on the first episodes before we knew whether our series might end with the story of a one-term black president.)

Street rally in New York City, October 11, 1955, under joint sponsorship of NAACP and District 65, Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Workers Union in protest of slaying of Emmett Till. Public domain via Library of Congress.

And as we considered whether to include the story of Emmett Till, the 14-year-old Chicago boy tragically killed in Mississippi in 1955, we followed the trial of George Zimmerman, who had fatally shot another unarmed black teenager, Trayvon Martin, over half a century later in Florida. When Zimmerman—just like Till’s murderers—was ultimately acquitted, it felt as though time had stood still. Except that, in 2013, our African American president acknowledged that Trayvon “could have been me, 35 years ago.”

Some of the most iconic stories, such as John Lewis’ heroic march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama on “Bloody Sunday” in 1965, took on the urgency of current events. While Selma paved the way for the passage of the Voting Rights Act, that same Act was being gutted before our eyes, in real time, as we scripted and filmed that story for the series. The controversial rise and rapid fall of affirmative action provided another fast-moving target.

Resistance, disappointment and despair were not the only themes that resonated across the centuries. Just as slaves created African American music, cuisine and culture amid the dehumanizing conditions in which they were forced to live, we traced how youth in the devastated South Bronx of the 1970s and 80s improvised a new popular culture—hip hop—out of nothing, that went on to conquer the world. As hip hop visionary Chuck D, founder and front man of the legendary group Public Enemy, said in his interview for our series, “Out of the ashes, rose the phoenix of hip hop.” And that phoenix is still thriving in 2013.

As we wrapped up the long process of story selection for all six episodes, we came to realize that our historical research actually helped us to elucidate the present—for ourselves, and now hopefully for our television viewers as well. The response to the series so far, in social media, the press and by word of mouth, seems to affirm that others hear the same echoes.

If it is true that those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it, perhaps this journey will encourage people to remind themselves of what does, and does not, bear repeating. Working on The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross has been a fascinating and inspiring voyage through the past. But perhaps the most exciting revelation has been that the story isn’t over: this history is still being made, every day.

Leslie Asako Gladsjo, a New York-based documentary filmmaker, served as senior story producer of The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross and also directed the final episode, A More Perfect Union, which covers the era from 1968 to 2013. She has worked with Henry Louis Gates, Jr. on four previous series for PBS, including Finding Your Roots (2012), Faces of America (2010) and African American Lives 1 and 2 (2008 and 2006). Before that, Gladsjo was based in Paris, where she made documentaries on social and cultural topics for European broadcasters including Arte, France 2, France 5, BBC and others.

The Oxford African American Studies Center combines the authority of carefully edited reference works with sophisticated technology to create the most comprehensive collection of scholarship available online to focus on the lives and events which have shaped African American and African history and culture.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A journey through 500 years of African American history appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCommon Core: lesson planning with the Oxford African American Studies CenterThe African CamusJudging a book by its cover: recordings, street art, and John Coltrane

Related StoriesCommon Core: lesson planning with the Oxford African American Studies CenterThe African CamusJudging a book by its cover: recordings, street art, and John Coltrane

National Bible Week: Learning with Don Kraus, OUP Bible editor

To celebrate National Bible Week, we sat down with our long-time Bibles editor, Don Kraus, to find out more about his experience with publishing bibles at Oxford University Press.

How long have you been at OUP, and have you worked on Bibles the whole time?

I have worked at OUP since 21 February 1984, and yes, I’ve been Oxford’s Bible editor for that entire time. In fact, one of our former OUP-US presidents used to joke at the annual employee party that “We have an editor with us for [5, 10, 15] years, and he’s only published one book in that entire time.” I think the third time it was less funny!

Don Kraus, OUP’s Bible editor.

What can you tell us about the history of Bibles publishing at OUP?

Oxford isn’t the oldest Bible publisher in the world, but it’s been in the business for a long time — since about 1575. (That was before I came to work here.) In the 19th century Oxford Bibles were sold all around the world, and those sales helped finance other Press activities, including the Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford was the first Bible publisher to develop really thin, strong paper; to include many cross-references (internal links between one Bible verse and another on the same topic or using similar wording); and to publish a Bible with commentary on the same page as the Bible text. The last one is what we know as the original Scofield Reference Bible, published in 1909 and the first publication by OUP in New York — the New York office opened in 1896, but it started as a sales operation and only developed into a publishing center with the Scofield Bible.

What do you think is one of the biggest differences about publishing Bibles rather than other kinds of books?

I think there are two main differences, one physical and one that you might call meta-physical. The physical one is that Bibles are much longer than most books — the Old Testament/Hebrew Bible is about 500,000 words, and the New Testament is almost 200,000; if you add the Apocryphal Books you will have a total word count of nearly 900,000 words. A major trade book, like a blockbuster novel or a best-selling biography, is rarely longer than a couple of hundred thousand words. So Bibles are long, and in order to keep them in bounds they are published on very thin paper, which is not used for anything else. That makes Bible production something of a specialty. Then there are the leather-bound editions, the ones with ribbon markers for keeping your place, and other special features, and the production process can get really complicated.

Study Bibles, our mainstay, get even longer, of course. Our biggest ones are more than 2400 pages, and can amount to 1.4 million words, which is about the limit for something that can be bound in one volume and still hold together!

The “meta-physical” difference in Bible publishing is the incredible fussiness of members of the Bible-readership. A typographical error is a major crisis for some of our readers, and we regularly get mail (or nowadays e-mail) from anguished readers who basically say, “How could you publish this Bible with an error in it?”

How long can the process be for publishing a Bible, start to finish?

A major new study Bible will take five to six years, from the time we plan it to the time we publish. This is not an “insta-book” business! We carefully review a proposal for such a resource, sometimes including research into the student or religious readerships, and work closely with the editorial board to plan the contents and the contributors. When the submissions begin to come in, we edit them carefully so that they are appropriate for the intended audience. We also supply supplemental materials in the back matter, including a glossary of technical terms and guidance about where to find English translations of ancient writings (other than the Bible) that the biblical authors might have known. We also have the whole text copy-edited, and the study materials and Bible text proofread.

What is the most surprising thing you’ve found about working on Bibles?

I think the one aspect of this job that I did not expect was the way in which we could keep developing new publications in such a limited area. There always seems to be something new or different to say about the biblical text, and some new way of presenting it. I would never have imagined when I started in this job that we would have published so many different kinds of Bibles.

How have the changes to publishing and shift to digital affected Bibles publishing at OUP?

Bibles have been available in electronic form for some years now, starting actually back in the time of floppy disks (yes, there were Bible texts on floppies — and they were very awkward to navigate). Later, with CD-ROMs and now with web-based publishing, you can find a wide array of translations at least for reading, if not downloading. And specialist publishers offer subscription services that provide a range of translations, original language texts, and loads of reference tools for researchers.

So far, this hasn’t impacted our sales of print versions very much. There is still a sense that “the Bible” as a printed book is something that people want to have, even if their regular reading is in another medium. As time goes on, however, and as our student population increasingly turns to web-based learning and digital resources, I would expect that our Bible sales will gradually migrate onto the web. And we will then have to decide about the extent of the materials that we will make available: as mentioned above, we’re now about at the limit of a bound, one-volume print edition in our study Bibles, but on the web there is no limit other than the reader’s/viewer’s fatigue!

Any interesting stories to tell concerning working on Bibles?

I think the book that we published that made the biggest splash — though not, I’m sorry to say, on the sales end – was the Inclusive Language New Testament and Psalms, which came out in 1995, when Bill Clinton’s presidency was first dealing with the Republican takeover of Congress (this political background is relevant, as you’ll see below). The inclusive language version was an adaptation of the New Revised Standard Version that avoided male-gendered language not just about human beings, but about God. Terms such as “kingdom” were rendered “reign”; “Father” became “Father-Mother”; even the devil, who in standard translations is male, was not referred to in gendered language.

The reaction was virtually instantaneous, and although some people liked our version, many more were very angry – and they let us know it. My favorite “fan” letter, from a detractor, began, “To Satan’s Right Hand Man (and Clinton supporter).” Another one told me, “You are the scum of a cesspool.” (My thought about that one was, “Well, better scum than lees.”) It was a novel experience for someone who had been in the backwater area of Bible publishing, and who was suddenly Exhibit A in the culture wars. I’ve since receded to the backwaters again.

Don Kraus studied Greek and Hebrew as an undergraduate (Trinity College, Hartford) and Hebrew and biblical studies at the Harvard Divinity School. He has worked in publishing since 1978 (before that he was in bookselling) and has been Oxford’s Bible editor for nearly thirty years. He is the author of three books: Choosing a Bible, about the differences among Bible translations and the readerships for which they are intended; Sex, Sacrifice, Shame, and Smiting, about how to understand difficult or repellent passages in the Bible; and The Book of Job: Annotated and Explained, a translation of Job with an introduction and annotations intended for general readers. He is married (to Susan, an Episcopal priest who is the Rector of St. Giles’ Episcopal Church in Jefferson, Maine). He lives in Maine. He likes murder mysteries, preferably British and not too gory.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post National Bible Week: Learning with Don Kraus, OUP Bible editor appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLooking forward to AAR/SBL 2013Rowan Williams on C.S. Lewis and the point of NarniaThe bin of plenty

Related StoriesLooking forward to AAR/SBL 2013Rowan Williams on C.S. Lewis and the point of NarniaThe bin of plenty

Raising the Thanksgiving turkey

A century ago, the turkey was in truly poor shape. Its numbers had dropped considerably during the late nineteenth century, largely due to overhunting, habitat loss, and disease. In 1920, there were about 3.5 million turkeys in the United States, down from an estimated 10 million when Europeans first arrived in North America. For those Americans in the 1920s who thought about turkeys, fear was in the air: in the future, would there be turkeys to raise? And would there be turkeys to hunt?

Today, there are over 250 million turkeys in the United States. Most of them are domestic turkeys destined for supermarket shelves, but a solid seven million of them roost in the nation’s forests, the object of hunters’ early morning pursuits. Together, the story of wild and domestic turkeys in the United States is one of both massive decline and astonishing restoration.

It is also a story of an incredible division of knowledge, and even loss of knowledge—mostly due to American attitudes toward gender and work.

To explain, it is best to visit the late eighteenth century, when Americans started paying serious attention to turkey raising. Tending the birds was almost entirely women’s work. The often cited observer of American culture, J. Hector St. John Crevecoeur, wrote in 1782 that “our wives are famous for the raising of turkeys” and important diarists of the era, such as the Maine midwife Martha Ballard, made it clear that women indeed were the ones who commonly raised turkeys. Her diary is rich with entries about tending turkeys, including one from 4 May 1792 that read “Put 17 Eggs under Turkey who was Seting.”

In the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, farmwomen in the East and Midwest commonly raised turkeys. To raise hearty birds, they frequently crossed wild and domestic strains by finding the eggs of wild turkeys and raising the birds with their domestic flocks. This illustration, which appeared in an 1833 children’s magazine, displays the popular association of farmwomen with the poultry yard. Credit: Parley’s Magazine for Children and Youth, Saturday, October 12, 1833, 42, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library. Used with permission

Placing eggs in a nest was no trivial act. It blended wild and domestic strains, for the turkey eggs Ballard and other women were putting under their turkeys were eggs they had found in the woods. As Crevecoeur noted, in successful turkey raising, “The great secret consists in procuring eggs of the wild sort.” For a century more, American farmwomen along the East Coast and later in the Midwest commonly used wild stock to keep their domestic flocks healthy, for they understood the problems of too closely interbreeding their turkeys. By the late 1800s, they were entering turkeys into agricultural shows, proud of the strong breeding lines they had created. Among the many breeds, the favored was the Bronze, which the American Farmer noted, were “much sought for because they derive from wild stock.”

Disaster hit in the 1890s, though, and it divided the nineteenth century of American farmwomen raising turkeys from the twentieth century of turkey agribusiness and wildlife management. The disaster was a disease called blackhead. It destroyed a turkey’s liver. The national production of domestic turkeys, which had peaked in 1890 at about 11 million, withered to a mere 3.5 million over the next three decades. Attempts to revive the industry included searching for wild stock to resuscitate the domestic breeds, but wild turkeys were becoming increasingly difficult to find. Overhunting and habitat destruction had nearly extirpated the wild turkey from the United States. Ohio saw its last native wild turkey in 1880 and other Midwestern states soon followed the pattern: Michigan in 1897; Illinois in 1903; and Indiana in 1906.

When the domestic turkey industry did turn around, it did so in the American West, where blackhead was not endemic. Turkey ranching, as it was called, emulated the model of chicken raising, which was gradually adopting efficiency as its most honored value. In the 1920s and 1930s, turkeys became the central focus of farms, no longer a sideline activity. Poultry scientists fine-tuned the breeding of the Bronze turkey, making it first bigger and then white, so that its carcass would appear more attractive at the grocery store (dark feathers left small marks). Meanwhile, the wild turkey population rebounded, largely thanks to the efforts facilitated by the 1937 Pittman-Robertson Act, which created funding for state wildlife agencies. One wildlife biologist calls the rebound the best “example of success in modern wildlife management.” From a low of about 30,000, the wild turkey population has increased to its current 7 million.

In the history of the Thanksgiving turkey, the professionalization of knowledge created a split: wildlife managers studied wild turkeys and poultry scientists studied domestic turkeys. There were few, if any, young farmwomen who grew up to be mid-twentieth century poultry scientists or wildlife managers, and no one in those fields talked about crossing domestic and wild strains, the time honored practice of farmwomen. In fact, that knowledge became largely lost: in a 1967 wild turkey management guide, the Wildlife Society declared that domestic breeds did not derive “from native wild birds.” The organization was simply unaware of farmwomen’s work decades before. The story of the Thanksgiving turkey, then, is a story about how gender, labor, and knowledge relate. If there is a lesson, it is that what we know about nature depends a lot upon who we are and the work we do.

Neil Prendergast is Assistant Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point. He is currently working on a book about nature and American holidays. He is the author of “Raising the Thanksgiving Turkey: Agroecology, Gender, and the Knowledge of Nature” (available to read for free for a limited time) in Environmental History.

Environmental History (EH) is the leading journal in the world for scholars, scientists, and practitioners who are interested in following the development of this exciting field. EH is a quarterly, interdisciplinary journal that carries international articles that portray human interactions with the natural world over time.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only food and drink articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Raising the Thanksgiving turkey appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTransitional justice and international criminal justice: a fraught relationship?Oral history goes transnationalHelping smokers quit during Lung Cancer Awareness Month

Related StoriesTransitional justice and international criminal justice: a fraught relationship?Oral history goes transnationalHelping smokers quit during Lung Cancer Awareness Month

Penderecki, then and now

Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki (pronunciation here) celebrated his 80th birthday over the weekend. As Tom Service has pointed out in the past, you’ve probably already heard some of Penderecki’s famous pieces from the 1960s, which feature in several films from directors such as David Lynch, Stanley Kubrick, and Martin Scorsese. The Radiohead fans out there might also remember Jonny Greenwood’s collaboration with Penderecki last year, which resulted in fresh recordings of two of those famous early pieces, that in turn inspired two new works by Greenwood (48 Responses to Polymorphia and Popcorn Superhet Receiver). Penderecki’s early work, experimental in just about every possible way, still sounds futuristic in 2013; take for example Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Despite the popularity of his avant-garde works, which were considered truly ground-breaking at the time of their composition, Penderecki left that style behind in the mid-1970s to embrace what some would call more familiar musical territory. This perceived familiarity arises mostly from the fact that Penderecki distilled the texture of the later works to discernible tones. In the early works, the textures are so dense and/or unusual that it is difficult to know what notes are being sounded, and what instruments are playing them, at a given moment. Often the music sounds electronically produced when in reality only acoustic instruments are playing. In the works since the mid-70s it becomes easier to identify which instruments are playing, as in his Symphony No. 7, written in 1996:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Nonetheless, Penderecki’s post-avant garde music is still arcane, and can be challenging listening even if it is lighter on the tone clusters. Take for example the opening cello solo in his Concerto Grosso No. 1, for three cellos and orchestra, written in 2000:

Click here to view the embedded video.

The notes in this solo string together to make, not so much a melody, but more of a sinuous line whose path takes advantage of the wide range of the cello and whose message seems grave and deep. The orchestra and other cellos continue in the same vein until about 4:55 into the video, when we hear a descending succession of rich, contemplative chords, interrupted about a minute later by loud woodwinds drawing us back into the more linear, angular style of the opening. This mixing of styles is common in Penderecki’s work, and further prevents us from planting it firmly in any one camp of composition.

Arcaneness aside, there is, as Adrian Thomas puts it in his Grove Music Online article on Penderecki, “an almost cinematic quality to the emotional directness of the music” in both the early and current styles. Penderecki, whether blowing our minds with experimental sounds or using instruments in more traditional ways to no less dramatic effect, consistently leads his listeners down a clear emotional path. I’m looking forward to hearing where he leads us next.

Meghann Wilhoite is an Assistant Editor at Grove Music/Oxford Music Online, music blogger, and organist. Follow her on Twitter at @megwilhoite. Read her previous blog posts on Sibelius, the pipe organ, John Zorn, West Side Story, and other subjects.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Penderecki, then and now appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBenjamin Britten, revisitedSofia Gubaidulina, light and darknessFrancesca Caccini, the composer

Related StoriesBenjamin Britten, revisitedSofia Gubaidulina, light and darknessFrancesca Caccini, the composer

November 25, 2013

In memoriam: M. Therese Southgate

Marie Therese Southgate, MD, a senior editor at JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association for nearly five decades, died at her home in Chicago on 22 November 2013 after a short illness. She was 85.

Dr Southgate was born in Detroit, Michigan, on 27 April 1928; the family moved to Chicago in the 1930s. She attended the College (now University) of St Francis in Joliet, Illinois, graduating with a degree in chemistry in 1948. She earned her MD degree from Marquette University School of Medicine (now the Medical College of Wisconsin) in 1960, one of only three women in her graduating class. She completed her rotating internship at St Mary’s Hospital in San Francisco in 1961.

Dr Southgate accepted the position of senior editor at JAMA, headquartered in Chicago, in 1962, the first woman to hold that position. Two years later, the editors of JAMA made the bold and unprecedented decision to feature a work of fine art on the journal’s cover. In 1974, Dr Southgate was promoted to deputy editor, the second-highest position at the journal. That same year, she began to select all of the works of fine art as well as to write an eloquent accompanying essay. “The Cover” became a hugely popular and much-admired weekly feature until the journal was redesigned in 2013. Although she had no formal art education, she had a keen appreciation of the fine arts and crafted “highly insightful, lyrical essays.”

Many readers—physicians and nonphysicians alike—often asked why a preeminent journal in clinical and scientific medicine would reproduce a renowned work of fine art on its front cover each week. The answer was clear: “The visual arts have everything to do with medicine,” Dr Southgate said. “There exists between the two an affinity that has been recognized for millennia. Art is a uniquely human quality. It signifies the unquenchable human quality of hope. Long and loving attention is at the heart of painting. It is also at the heart of medicine, at the heart of caring for the patient.”

“Terry Southgate became the most beloved of all JAMA editors as a supremely sensitive humanist who selected the world’s greatest art with which to educate countless physicians about the intense humanity of their calling,” said former JAMA editor in chief George D. Lundberg, MD. In a 2007 Medscape interview, Dr Southgate stated: “What has medicine to do with art? I answer: Everything.”

JAMA Editor in Chief Howard Bauchner, MD, stated, “One of the great strengths of JAMA for decades has been its inclusion of the humanities—and no one epitomized that effort more than Terry Southgate, who orchestrated the wonderful art in JAMA for more than 40 years.

In 1997, 2001, and 2010, Dr Southgate published three successive collections of her essays and the accompanying images that had appeared in JAMA over the years—The Art of JAMA—to critical acclaim. She was the 2008 recipient of the Nicholas E. Davies Memorial Scholar Award for Scholarly Activities in the Humanities and History of Medicine from the American College of Physicians. She was chosen by the US National Library of Medicine as a Local Legend, “honoring the remarkable, deeply caring women doctors who are transforming medical practice and improving health care for all across America.”

Catherine D. DeAngelis, MD, MPH, editor emerita, JAMA, stated: “The world has lost a warm, soft-spoken, unpretentious icon who taught so many physicians and others the value of art in life and who now exemplifies her motto, Ars longa, vita brevis.”

Dr Southgate semiretired from JAMA in 2008 and spent much of her time at her Marina City writing studio in Chicago, polishing her memoirs and finishing a murder mystery set in a medieval English town.

Dr Southgate is survived by her brother Clair (Marie) Southgate of San Diego, California; niece Therese (Dan) Southgate Fellbaum and grandnephews Tom and Marc and grandniece Claire of Valencia, California; and niece Susan (Dan) Southgate Johnson and grandnieces Audrey, Lucy, and Gracie of San Jose, California. She was predeceased by her parents Clair and Josephine Southgate.

M. Therese Southgate, MD, Physician-Editor, Fine-Art Specialist

27 April 1928 – 22 November 2013

The post In memoriam: M. Therese Southgate appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHelping smokers quit during Lung Cancer Awareness MonthWorn out wonder drugsDepression in older adults: a q&a with Dr. Brad Karlin

Related StoriesHelping smokers quit during Lung Cancer Awareness MonthWorn out wonder drugsDepression in older adults: a q&a with Dr. Brad Karlin

The bin of plenty

In a desk donated to the Vermont thrift store at which he worked, Tim Bernaby was pleasantly surprised to find several letters and cards written by Robert Frost. He took these missives and sold them for $25,000. When asked about it, he said he found the items not in the desk, but in the trash — an excuse that must have seemed to him unassailable, but that in the field of rare book, map, and document theft is something of a cliché. Next to grandpa’s attic trunk, the humble trash bin is the choicest place for thieves to find otherwise unexplainable items.

The American trash digger par excellence is surely David Breithaupt. If he is to be believed, the garbage dump at the back dock of Kenyon College’s Olin and Chalmers Library, where he worked, was something of a cornucopia, existing for nearly a decade and replenishing his shortage of valuable books on a schedule coinciding nicely with his need for cash. This trash can (actually, it was trash bags) claim was so central to his defense that he trotted it out early and often — not only was it the first official excuse he used, but it was the mainstay he relied on in legal briefs even years later. It was an excuse generally derided by central Ohio lawyers, librarians, and normal people, but accepted by an astonishing array of the literary figures Breithaupt glommed onto during his years in New York.

It is worth noting that while the trash-dock-of-plenty was Breithaupt’s most dearly held and oft-stated excuse, he did not rely on it alone to explain how he came to possess so many hundreds of the college’s rare materials. He “found” several Kenyon books — including a 1635 Mercator Atlas and a first edition Adventures of Huckleberry Finn — at a nearby antique shop. He also “found” a particularly valuable Flannery O’Connor letter tucked into an otherwise unrelated book he bought at a local sale. In the end, Breithaupt was either a hapless fabulist who was dead-to-rights guilty, or the luckiest collector in the history of mankind. A central Ohio jury believed it to be the former.

Breithaupt, as it happens, paid a fairly stiff price for his crimes. Nineteenth century Biblical scholar Constantin Von Tischendorf, on the other hand, parlayed his trash finding story into celebrity. As a young man, Tischendorf set for himself the rather ambitious goal of reconstructing the original text of the New Testament; he noted to a friend that he would compile this Bible “upon the strictest principles; a text that will approach as closely as possible to the very letter as it proceeded from the hands of the Apostles.” Initially this meant he would simply make copies of the oldest New Testaments he found, mostly in Europe, and bring them together for research. But his thinking on the matter would evolve.

Breithaupt, as it happens, paid a fairly stiff price for his crimes. Nineteenth century Biblical scholar Constantin Von Tischendorf, on the other hand, parlayed his trash finding story into celebrity. As a young man, Tischendorf set for himself the rather ambitious goal of reconstructing the original text of the New Testament; he noted to a friend that he would compile this Bible “upon the strictest principles; a text that will approach as closely as possible to the very letter as it proceeded from the hands of the Apostles.” Initially this meant he would simply make copies of the oldest New Testaments he found, mostly in Europe, and bring them together for research. But his thinking on the matter would evolve.

In 1844, he travelled across North Africa and arrived, eventually, at St. Catherine’s Monastery on the Sinai Peninsula. It was, he later claimed, in the monastery’s library that he noticed a basket full of papers “mouldered by time,” being consigned to flames for the sake of heat. He “rescued” from this trash basket some 86 pages of what turned out to be a fourth century Bible, and brought them back to Leipzig. In an age when fire was a major threat to books, saving one from the flames must have struck Tischendorf as an entirely believable tale — never mind that parchment (which is animal skin, after all) does not burn well enough to be a good source of heat. But aside from that, to accept his rescued-from-refuse claim, a person would have to believe that, after some fifteen hundred years of existence, monks were burning the oldest extant copy of the Bible, in the library, on the very day that a man professed to be searching for things exactly like that just happened to be there. In any event, Tischendorf’s story is somewhat undercut by the fact that he returned years later and stole/borrowed/bought (depending upon who is asked) the rest of the manuscript containing the New Testament.

It is tempting to think that 19th century folks were more credulous, and believed the story as Tischendorf wrote it. Some did, of course — like some continue to believe Breithaupt. But here is the 1892 judgment of noted Englishman and book collector W. G. Thorpe: “But as to stealing books. The thing is not only sometimes lawful, but even meritorious, and one man will go to heaven for it — in fact, has gone there already. The mode in which Tischendorf ran off with the Codex Sinaiticus…may be described as anything you please, from theft under trust to hocussing and felony; but it succeeded, and all Christendom was glad thereof.”

Christendom is unlikely to look as kindly upon the trashcan discoveries of Tim Bernaby. Still, who needs Christendom when you have a permissive legal system: Bernaby pleaded guilty to unlawful taking of personal property and was fined $100.

Travis McDade is Curator of Law Rare Books at the University of Illinois College of Law. He is the author of Thieves of Book Row: New York’s Most Notorious Rare Book Ring and the Man Who Stopped It and The Book Thief: The True Crimes of Daniel Spiegelman. He teaches a class called “Rare Books, Crime & Punishment.” Read his previous blog posts: “The professionalization of library theft” ; “Barry Landau’s coat pockets” ; “The difficulty of insider book theft” ; and “Barry Landau and the grim decade of archives theft”.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Konstantin von Tischendorf (1815–1874), German theologian, around 1870. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The bin of plenty appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFive things you didn’t know about Franklin PierceThoughts on the 50th anniversary of JFK’s assassinationPlace of the Year 2013: Then and Now

Related StoriesFive things you didn’t know about Franklin PierceThoughts on the 50th anniversary of JFK’s assassinationPlace of the Year 2013: Then and Now

Seven selfies for the serious-minded

Self-portraits are as old as their medium, from stone carvings and oil paintings, to the first daguerreotypes and instant Polaroids. Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year 2013 – selfie – indicates the latest medium: a photograph that one has taken of oneself, typically one taken with a smartphone or webcam and uploaded to a social media website. Our editors found that the frequency of the word selfie in the English language has increased by 17,000% since this time last year and given its new ubiquity, it isn’t hard to find selfies in a variety of settings. While it’s not always appropriate to snap a quick picture of yourself, there are wonderful instances of selfies that provide context and reflection.

Historical selfies

Many early photographers — whether famous impressionists or First World War servicemen — felt the familiar compulsion to capture themselves on film. Robert Cornelius made arguably the first selfie in 1839 in the early days of photography. As Melissa Mohr stated: “after 174 years and billions of tries, this has never been improved upon.”

Robert Cornelius, self-portrait, 1839. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Scientific selfies

As scientists pioneer new fields of study they record their work — and sometimes themselves performing it. Astronaut selfies like NASA’s Aki Hoshide or ESA’s Luca Parmitano add a new dimension to the documentation of space exploration. NASA’s Mars Curiosity Rover is also fond of showing off at work.

Political selfies

Politicians are no strangers to the arrangement and control of images, so it isn’t surprising to find many using selfies to present their programs, their events, and themselves. First Lady Michelle Obama assisted National Geographic in compiling the largest animal photo album. Chelsea Clinton tweeted a selfie with her mother Hillary Clinton. Bill Clinton and Bill Gates broadcast their attendance at the Clinton Global Initiative.

Religious selfies

It may be a stretch from silent prayer and contemplation or offerings at Shinto temple, but cameras are now omnipresent in scared spaces and on sacred occasions. When one is able to meet a world religious leader and has a smart phone in hand, the temptation for a selfie religious experience is too great. Fabio M. Ragona is now well-known for his photographic encounter with Pope Francis.

Cinematic selfies

In an industry dominated by the image, it’s no wonder that many films feature characters who photograph others and themselves. Recently The Bling Ring featured several teenagers taking traditional party selfies, but self-portraiture features in classics as well. And of course, actors are not afraid to mock the ever-watchful eye of the camera.

Sporting and gaming selfies

The “game face” is hardly a new phenomenon, but can you imagine Instagramming it to the opposing team before a game? Whether taking mascot selfies for fans or documenting your game progress, selfies are becoming part of the athlete and gamer repertoire. Would you want to cross the Golden State Warriors?

Literary selfies

With traditions of autobiography, essay-writing, and thinly-disguised fiction, it’s difficult to see the need for photographs in literary circles. Yet from beloved characters, to publisher logos, to authors themselves, literary self-analysis isn’t limited to words.

What selfies would you add to the list?

Alice Northover is editor of the OUPblog and Social Media Manager at Oxford University Press.

The Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year 2013 is ‘selfie’. The Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year is a word, or expression, that has attracted a great deal of interest during the year to date and judged to reflect the ethos, mood, or preoccupations of that particular year and to have lasting potential as a word of cultural significance. Learn more about Word of the Year in our FAQ, on the OUPblog, and on the OxfordWords blog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Seven selfies for the serious-minded appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesScholarly reflections on the ‘selfie’Is this a selfie which I see before meLanguage history leading to ‘selfie’

Related StoriesScholarly reflections on the ‘selfie’Is this a selfie which I see before meLanguage history leading to ‘selfie’

Place of the Year 2013: Then and Now

Thanksgiving is a time for reflection on the past, present, and future. In our final week of voting for Place of the Year, here’s a look at some of the many changes undergone by the nominees. Which of these will steal the crown from Mars, the 2012 Place of the Year?

Syria

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

A view of Damascus taken around 1910, from the Oregon State University Special Collections & Archives via Flickr Commons.

Syria

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Buildings destroyed by aerial bombings in Azaz, Syria in August 2012. The Syrian Civil War began in Spring 2011 and continues today. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Copacabana Beach, Rio De Janeiro, Brazil, between 1930 and 1947. Image via Library of Congress.

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Brazil has undergone profound growth since then, as Copacabana Beach in 2009 demonstrates! Photograph by Rodrigo Soldon. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License via Wikimedia Commons.

Tahrir Square, Egypt

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Tahrir Square with the Egyptian Museum on the left, circa 1940s. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Tahrir Square, Egypt

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Once merely a traffic intersection, Tahrir Square has been the seat of revolutionary activity since 2011. Here, thousands of Egyptians protest, demanding President Hosni Mubarak’s resignation, on February 9, 2011. Photo by Jonathan Rashad, Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

Greenland

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

View over the Tasiusaq Bay, Greenland in the late 19th-early 20th century. Photograph by Th. N. Krabbe, National Museum of Denmark via Flickr Commons.

Greenland

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Think this canyon along Greenland’s northwest coast is huge? Scientists discovered the longest canyon in the world under Greenland’s ice sheet earlier this year. Image courtesy of NASA/Michael Studinger.

utah

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The NSA Data Center in Bluffdale, Utah lies at the foot of the Wasatch Mountain Range, seen in this photochrom print from 1900. Image courtesy of The Library of Congress.

Utah

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The NSA Data Center resides on approximately 1 million square feet of land in Bluffdale , Utah, just south of Salt Lake City. Image by Swilsonmc, used under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, v1.2 via Wikimedia Commons.

Make sure to vote for your pick below!

What should be Place of the Year 2013?

SyriaTahrir Square, EgyptRio de Janeiro, BrazilThe NSA Data Center, United States of AmericaGrand Canyon, Greenland

View Result

Total votes: 189Syria (52 votes, 28%)Tahrir Square, Egypt (20 votes, 11%)Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (43 votes, 23%)The NSA Data Center, United States of America (33 votes, 17%)Grand Canyon, Greenland (41 votes, 21%)

Vote

Oxford’s Atlas of the World — the only world atlas updated annually, guaranteeing that users will find the most current geographic information — is the most authoritative resource on the market. The milestone Twentieth Edition is full of crisp, clear cartography of urban areas and virtually uninhabited landscapes around the globe, maps of cities and regions at carefully selected scales that give a striking view of the Earth’s surface, and the most up-to-date census information. The acclaimed resource is not only the best-selling volume of its size and price, but also the benchmark by which all other atlases are measured.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only geography articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits:

(1) Syria, then: The Oregon State University Special Collections & Archives via Flickr Commons

(2) Syria, now: Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

(3) Rio de Janeiro, then: General [view], Brazil, D.F. [Distrito Federal], Rio De Janeiro, Copacabana Beach Image via Library of Congress.

(4) Rio de Janeiro, now: Photograph by Rodrigo Soldon. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License via Wikimedia Commons.

(5) Tahrir Square, then: Tahrir Square with the Egyptian Museum on the left, circa 1940s. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

(6) Tahrir Square, now: Photograph by Jonathan Rashad, Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

(7) Greenland, then: Photograph by Th. N. Krabbe, National Museum of Denmark via Flickr Commons.

(8) Greenland, now: Image courtesy of NASA/Michael Studinger.

(9) Utah, then: Image courtesy of The Library of Congress.

(10) Utah, now: Image by Swilsonmc, used under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, v1.2 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Place of the Year 2013: Then and Now appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAnnouncing the Place of the Year 2013 Shortlist: Vote for your pickPlace of the Year 2013: Behind the longlistPlace of the year 2013: Spotlight on Syria

Related StoriesAnnouncing the Place of the Year 2013 Shortlist: Vote for your pickPlace of the Year 2013: Behind the longlistPlace of the year 2013: Spotlight on Syria

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers