Oxford University Press's Blog, page 876

November 21, 2013

Bad behavior overshadows more subtle systemic exclusions in academia

Much has been made in the media of Professor Colin McGinn’s resignation amid claims that he sexually harassed a female graduate student. The story has headline-grabbing ingredients:

Sex (that is, sexual harassment)

A famous person (well, McGinn is relatively famous within the field of philosophy)

Power relationships (the white, middle-aged, male teacher, and the young, female research assistant)

Tragic consequences (career-ending consequences for him and untold consequences for her)

It is not surprising, then, that the case has resulted in a rare public airing for issues that have been an ongoing concern for women in philosophy. But to what extent does this sort of publicity further the cause of women in philosophy — a field in which women are very poorly represented compared with other disciplines in the humanities? Is overt bad behaviour the main issue facing women, or might more subtle forms of exclusion also need to be addressed?

In contrast with the McGinn case, consider this: “When I was a graduate student one of my fellow students commented that I could not understand the hardships of the academic lifestyle because I was married with a child.”

This story is not a headline-grabber. What’s more, it is not comparable to the McGinn story. It does not belong in the same conversation. A comparison between the two risks trivializing sexual harassment.

Yet the stereotypes at play are harmful. The comment implies that the woman’s peers do not expect her to enter the academic job market with its associated uncertainties, or to disrupt her marriage and family by moving across the country or across the world for an academic job.

There are many other subtle forms of exclusion within philosophy that do not seem to belong in the same conversation as sexual harassment. Jennifer Saul draws our attention to the role of implicit bias in excluding women from philosophy. Citing recent work in social psychology, she points out that the same CV will be judged more positively when it is believed to belong to a man, and the same applies to the review of non-blinded journal submissions.

Samantha Brennan explores exclusions that are even harder to measure than this in her discussion of micro-inequities — unjust inequities that are so small on their own that any mention of them sounds like paranoia. They can include the length of time that someone holds eye contact with you, or how much they say in response to your question. Studies have shown correlations between such small acts and gender. Brennan argues that the cumulative impact of these micro-inequities is likely to be contributing to the underrepresentation of women in philosophy.

Fiona Jenkins has pointed out that mechanisms such as peer review and journal metrics can also be sites of subtle exclusion, in spite of the liberal feminist emphasis on the role of such “fair” meritocratic measures in combating the sexism of the old fashioned “jobs for the boys” alternatives. The conservatism of these meritocratic measures often goes unrecognized, situated as they are within current disciplinary and institutional norms, and upheld by “peers” whose academic reputations are invested in the immediate past of the discipline. Why should we think that they will fairly judge the contributions of the emerging generation — those who will be their disciples or their critics? Track record is another conservative measure of excellence, increasing the likelihood that those who were successful by previous standards will continue to be successful.

These three forms of subtle exclusion — implicit bias, micro-inequities, and unwarranted faith in meritocratic measures — are not practiced by unusual or bad individuals. They are widespread; they are practiced by women as well as men. The “perpetrators” are typically not aware that they are engaging in exclusionary behavior. Combating these forms of exclusion, then, relies heavily on raising awareness, and convincing individuals who believe themselves to be just and fair to change their behavior.

The case of Colin McGinn involves easily recognized bad behavior. It is something we take very seriously, especially given the prevalence indicated in blogs such as What Is it Like to Be a Woman in Philosophy? But there is a risk that when we connect the discourse about the low representation of women in philosophy to overt harassment, another important message about a wide range of subtle exclusions will be lost. We would appear to trivialize sexual harassment by comparing it with micro-inequities such as unequal eye contact during philosophy tutorials. But these can both have highly damaging consequences. Subtle, systemic forms of exclusion of women from professional philosophy deserve urgent attention and redress, alongside the overtly harmful and exploitative behavior of certain individuals.

Katrina Hutchision and Fiona Jenkins are co-editors of Women in Philosophy: What Needs to Change? Katrina Hutchison is a postdoctoral researcher at Macquarie University and is currently working on research projects on the ethics and epistemology of surgery. She also has research interests in feminist philosophy and in the role and value of philosophy beyond the academy. Fiona Jenkins teaches and researches in the School of Philosophy, Research School of Social Sciences, at the Australian National University. She is also the Convenor of the ANU Gender Institute. Her present research includes a project on Judith Butler’s political philosophy, and one looking at how disciplines in the Social Sciences have integrated feminist scholarship.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Philosophy, by Robert Lewis Reid, 1896. Photographed by Carol Highsmith. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Bad behavior overshadows more subtle systemic exclusions in academia appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWoody Allen, P.D. James, and Bernard Williams walk into a philosophy book…The vanished printing housesEnlightened blogging? Gilbert White’s Natural History of Selborne

Related StoriesWoody Allen, P.D. James, and Bernard Williams walk into a philosophy book…The vanished printing housesEnlightened blogging? Gilbert White’s Natural History of Selborne

Woody Allen, P.D. James, and Bernard Williams walk into a philosophy book…

Our ability to lead good lives right now is more dependent upon the survival of future generations than we usually recognize. Our motivations, values, and desires depend upon those who will follow us — human beings we will never meet or know. In Death and the Afterlife, Samuel Scheffler calls upon diverse cultural references — such as Woody Allen, P.D. James, and Bernard Williams in the extracts below — to explore these ideas.

On Woody Allen

Before moving on to my next topic, I want to take a brief detour to discuss the views of Alvy Singer. Alvy Singer, as you may remember, is the character played by Woody Allen in his movie Annie Hall. The movie contains a flashback scene in which the nine-year-old Alvy is taken by his mother to see a doctor. Alvy is refusing to do his homework on the ground that the universe is expanding. He explains that “the universe is everything, and if it’s expanding, someday it will break apart and that would be the end of everything!” Leaving aside Alvy’s nerdy precocity, the scene is funny because the eventual end of the universe is so temporally remote — it won’t happen for “billions of years,” the doctor assures Alvy — that it seems comical to cite it as a reason for not doing one’s homework. But if the universe were going to end soon after the end of his own natural life, then the arguments I have been rehearsing imply that Alvy might have a point. It might well be a serious question whether he still had reason to do his homework. Why should there be this discrepancy? If the end of human life in the near term would make many things matter less to us now, then why aren’t we similarly affected by the knowledge that human life will end in the longer term? The nagging sense that perhaps we should be is also part of what makes Alvy’s refusal to do his homework funny.

Diane Keaton and Woody Allen in Annie Hall. © Jack Rollins-Charles H. Joffe Production

* * *

On P. D. James

It is clear that the prospective destruction of the particular people we care about would be sufficient for us to react with horror to an impending global disaster, and that the elimination of human life as a whole would not be necessary. But, surprisingly perhaps, it seems that the reverse is also true. The imminent disappearance of human life would be sufficient for us to react with horror even if it would not involve the premature death of any of our loved ones. This, it seems to me, is one lesson of P. D. James’s novel The Children of Men, which was published in 1992, and a considerably altered version of which was made into a film in 2006 by the Mexican filmmaker Alfonso Cuarón. The premise of James’s novel, which is set in 2021, is that human beings have become infertile, with no recorded birth having occurred in more than twenty-five years. The human race thus faces the prospect of imminent extinction as the last generation born gradually dies out. The plot of the book revolves around the unexpected pregnancy of an English woman and the ensuing attempts of a small group of people to ensure the safety and freedom of the woman and her baby. For our purposes, however, what is relevant is not this central plot line, with its overtones of Christian allegory, but rather James’s imaginative dystopian portrayal of life on earth prior to the discovery of the redemptive pregnancy. And what is notable is that her asteroid-free variant of the doomsday scenario does not require anyone to die prematurely. It is entirely compatible with every living person having a normal life span. So if we imagine ourselves inhabiting James’s infertile world and we try to predict what our reactions would be to the imminent disappearance of human life on earth, it is clear that those reactions would not include any feelings about the premature deaths of our loved ones, for no such deaths would occur (or at any rate, none would occur as an essential feature of James’s scenario itself). To the extent that we would nevertheless find the prospect of human extinction disturbing or worse, our imagined reaction lacks the particularistic character of a concern for the survival of our loved ones. Indeed, there would be no identifiable people at all who could serve as the focus of our concern, except, of course, insofar as the elimination of a human afterlife gave us reason to feel concern for ourselves and for others now alive, despite its having no implications whatsoever about our own mortality or theirs.

* * *

On Bernard Williams

Bernard Williams’s main ambition in his essay on “The Makropulos Case,” in addition to establishing that death is normally an evil, is to argue that there is a sense in which it nevertheless gives the meaning to our lives, because an immortal life would be a meaningless one. But although he does not address the question of whether death is to be feared, he does suggest, intriguingly, that his position does not rule this out. Just as, in his view, death can reasonably be regarded as an evil despite the fact that it gives the meaning to life, so too, he suggests but does not argue, it may be that we have reason to fear death despite the fact that it is a condition of the meaningfulness of our lives. I believe that this combination of attitudes is in fact reasonable, and I will say more later about why. But first I want to examine Williams’s reasons for the two elements of his own position: the claim that death is an evil and the claim that it gives the meaning to our lives.

Williams’s argument that death is an evil turns on his distinction between categorical and conditional desires. Some desires are conditional on continued life: if I continue living, then I want to go to the dentist to have my cavity filled, but I don’t want to go on living in order to have my cavity filled. By contrast, if one wants something unconditionally or categorically, then one’s desire is not conditional on being alive. Or, as Williams puts it, it does not “hang from the assumption of one’s existence” (86). I may, for example, have a categorical desire to finish my novel or to see my children grow up. If so, then I have reasons to resist death, since death would mean that those desires could not be satisfied. And this, Williams thinks, is as much as to say that I have reason to regard death as an evil…

…The ultimate problem is deeper, and it is a problem about human life. We want to live our lives and to be engaged with the world around us. Categorical desires give us reasons to live, and they support such engagement. But when we are engaged, and so succeed in leading the kinds of lives we want, then the way we succeed is by losing ourselves in absorbing activities. When categorical desire dies, as it must do eventually if we have sufficient constancy of character to define selves worth wanting to sustain in the first place, then we will be left with ourselves, and we ourselves are, terminally, boring. The real problem is that one’s reasons to live are, in a sense, reasons not to live as oneself. It is I who wants to live, but I want to live by losing myself — by not being me. That is the paradox or puzzle that, if Williams is correct, lies at the heart of human experience, and rather than being a consequence of immortality, it is always with us mortals.

Samuel Scheffler is University Professor in the Department of Philosophy at New York University. He is the author of Human Morality, Boundaries and Allegiances, and Equality and Tradition. He is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Death and the Afterlife originated as the Berkeley Tanner lectures in 2012, and includes responses from philosophers Susan Wolf, Harry Frankfurt, Seana Valentine Shiffrin, and Niko Kolodny.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Woody Allen, P.D. James, and Bernard Williams walk into a philosophy book… appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe vanished printing housesEnlightened blogging? Gilbert White’s Natural History of SelborneLanguage history leading to ‘selfie’

Related StoriesThe vanished printing housesEnlightened blogging? Gilbert White’s Natural History of SelborneLanguage history leading to ‘selfie’

Detective’s Casebook: Unearthing the Piltdown Man

It is regarded as one of the most baffling scientific hoaxes of the past few hundred years. The mystery of the Piltdown Man, a skull believed to be an ancient ‘missing link’ in human evolution, blindsided the expert eyes of some of the greatest scientists of the 20th century. Armed with our trusty Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, let’s open our detective’s casebook to get to the bottom of this mystery, 60 years after first the Piltdown Man was first unmasked as a fake.

The Scene of the Crime

Barkham Manor, near Piltdown, Sussex, was the site of the initial skull recovery. Imagine the excitement of Charles Dawson, palaeontologist and antiquary, and now evolutionary pioneer, following his discovery of this ancient fossil. So excited was he that, partnering with his friend and (conveniently enough, some might say,) keeper of Geology in the Natural History sector of the British Museum, Arthur Smith Woodward, he announced this discovery to the Geological Society in London in 1912. And so as an addendum to the discovery, the coining of a new type of early human, namely Eoanthropus dawson, swiftly followed.

The Evidence

The skull appeared to indicate that the evolvement of the brain largely preceded other features, including the jaw and teeth, a fact that comfortably matched the expectations of some scientists at the time. It did indeed appear to be quite a revelation: Piltdown Man was unlike anything else in its evolutionary field.

The Piltdown Gang by John Cooke, 1915. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Crime Scene Investigation

Enter Joseph Weiner and Kenneth Oakley, whose revolutionary experimentation with fluorine paved the way for the initial doubts surrounding the authenticity of the apparent ancient skull. The tests revealed that the mandible and skull cap of the Piltdown Man were of late Pleistocene age — providing solid grounding for this scientific dispute: could a complex man-ape have existed in England at this time? Fuelled by uncertainty, Weiner demonstrated how the molar teeth may have been filed down and the fossil pieces to have been superficially stained, preceding Oakley to confirm this as true. A repeat of the fluorine-content analysis test found that the skull and jaw were of different ages and origins: a relatively recent human skull, with the jaw of a small orang-utan ape with filed teeth! And finally, following a series of further testing, the case was solved. In 1953, Piltdown Man was unearthed (excuse the pun) as a fraud.

The Suspects

Although the work of the 1950’s scientists is undoubtedly remarkable, the question regarding who masterminded this hoax remains unanswered. The list of potential of culprits range from the perhaps rather obvious Dawson, to the rather famous Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who played golf at Piltdown. Moreover, the motive(s) behind the hoax are a mystery we can only ever hope to solve.

Ellie Gregory is Marketing Assistant at Oxford University Press.

The Oxford DNB online is freely available via public libraries across the UK. Libraries offer ‘remote access’ allowing members to log-on to the complete dictionary, for free, from home (or any other computer) twenty-four hours a day. In addition to 58,800 life stories, the ODNB offers a free, twice monthly biography podcast with over 190 life stories now available. You can also sign up for Life of the Day, a topical biography delivered to your inbox, or follow @odnb on Twitter for people in the news.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Detective’s Casebook: Unearthing the Piltdown Man appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBenjamin Britten, revisitedEnlightened blogging? Gilbert White’s Natural History of SelborneA few things to remember, this fifth of November

Related StoriesBenjamin Britten, revisitedEnlightened blogging? Gilbert White’s Natural History of SelborneA few things to remember, this fifth of November

Selfies and the history of self-portrait photography

Selfie – the Oxford Word of the Year for 2013 – is a neologism defined as “a photograph that one has taken of oneself, typically one taken with a smartphone or webcam and uploaded to a social media website.” The emergence of this phenomenon a few years ago was therefore dependent on advances in digital photography and mobile phone technology, as well as the rise of Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, among other sites, which supply an outlet and audience for the photos. But a tradition of self-portraiture in photography is as old as the medium, and the popularity of amateur photography only slightly less so.

Robert Cornelius, self-portrait; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

According to the Grove Art Online entry on photography, “Perhaps the most popular form of early photography was the portrait. The very first portraits, especially those produced by the daguerreian process were treasured for their ability to capture the aspects of facial appearance that constitute family resemblance.” Invented by the French painter Louis Daguerre in the late 1830s, daguerreotypes, with their “cold, mirror-like appearance” were well-suited to capturing exacting likenesses of sitters. Portraits were the most commonly produced type of photographs in the first decades of photography, comprising an estimated 95% of surviving daguerreotypes. Among these are some exquisite self-portraits, including what may have been the first daguerreotype made in America, the self-portrait of the Philadelphia metalworker-turned-photographer Robert Cornelius.

Jean-Gabriel Eynard, daguerreotypist (Swiss, 1775 – 1863). Self-Portrait with a Daguerreotype of Geneva, about 1847, Daguerreotype, hand-colored. 1/4 plate Image: 9.7 x 7.3 cm (3 13/16 x 2 7/8 in.) Object (whole): 15.2 x 12.7 cm (6 x 5 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Many early self-portraits fall into two general categories. In the first type, which had a long tradition in painted portraits and self-portraits, the subject poses with a camera or a set of photographs, showing him as a professional of his trade. As portrait photographers competed for customers, these images demonstrated the photographer’s ability to capture a flattering likeness with his technical skill and his eye for setting and pose. The other type of self-portrait seems to have been the photographer’s attempt to situate photography as a fine art, a novel idea during the era of early photography. In a fine example of this type, Albert Sands Southworth, of the firm Southworth and Hawes, showed himself as a classical sculpted portrait bust, with a far-off, romantic expression. Although the daguerreotype was eventually replaced by other techniques (notwithstanding a 21st-century revival by Chuck Close), self-portraiture has remained one of the most interesting genres in photo history. It seems that from photography’s earliest days, there has been a natural tendency for photographers to turn the camera toward themselves.

Unknown maker, American, daguerreotypist. Portrait of Unidentified Daguerreotypist, 1845, Daguerreotype, hand-colored. 1/6 plate Image: 6.7 x 5.2 cm (2 5/8 x 2 1/16 in.) Mat: 8.3 x 7 cm (3 1/4 x 2 3/4 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

These early practitioners were either professionals with studios or “skilled amateurs” – often wealthy individuals who took up photography as a fashionable hobby. It would be a few decades before new processes and equipment brought the making of photographs to the masses. Pivotal in the development of amateur photography, George Eastman’s Kodak cameras, which hit the market in 1888, were “designed for the general public, who had only to point it in the right direction and release the shutter. When the 100-exposure roll provided with the camera had been exposed, the whole apparatus was returned to Eastman’s factory, where the paper rollfilm was developed and printed, the camera reloaded and returned to the customer; ‘You press the button, we do the rest’ was his slogan” (quite a bit easier than the painstaking process of creating a daguerreotype or a glass-plate negative). Kodak’s line of Brownie box cameras, first released in 1900 and priced at one dollar, made photography truly available to the broad public. Thus began a long era of popular photography made possible by the cheap production of cameras and efficient processing and printing of film.

[image error]

“A Kodak Camera advertisement appeared in the first issue of The Photographic Herald and Amateur Sportsman, November, 1889. The slogan “You press the button, we do the rest” summed up George Eastman’s ground breaking snapshot camera system.”

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The next great pivotal moment in the history of amateur photography – and perhaps photography in general – was the emergence of digital photography. Early digital cameras were available on the consumer market in the early 1990s, but it was not until technical improvements and a drop in prices over the next decade that digital photography had replaced older technologies. In 2002 more digital cameras were sold than film cameras, and Kodak, a giant in American industry for much of the 20th century, filed for bankruptcy in 2012. According to Mary Warner Marien,

…the public use of photographs has changed the medium. Where the photograph was once a tangible item, it can now exist as an array of pixels, seldom printed but collected in phones, cameras, computers and web-based image storage applications. Where once material photographs were saved, now photographs can be considered immaterial phenomena. There are more amateur photographers than ever before, and their conventions emerged in the early 21st century as powerful cultural shapers in the many branches of photographic practice.

The ease with which so many can take photographs of themselves and share them with an audience of many millions has made the selfie a “global phenomenon.” On one hand, this phenomenon is a natural extension of threads in the history of photography of self-portraiture and technical innovation resulting in the increasing democratization of the medium. But on the other, the immediacy of these images – their instantaneous recording and sharing – makes them seem a thing apart from a photograph that required time and expense to process and print, not to mention distribute to friends and relatives.

The ubiquity of selfies has naturally led some to wonder if the practice is either reflecting or promoting what many see as growing narcissism in contemporary culture. But perhaps, as Jenna Wortham suggests, selfies represent a new way not only of representing ourselves to others, but of communicating with one another through images: “Rather than dismissing the trend as a side effect of digital culture or a sad form of exhibitionism, maybe we’re better off seeing selfies for what they are at their best — a kind of visual diary, a way to mark our short existence and hold it up to others as proof that we were here. The rest, of course, is open to interpretation.”

Kandice Rawlings is Associate Editor of Oxford Art Online and holds a PhD in art history from Rutgers University. Read her previous blog posts.

Oxford Art Online offers access to the most authoritative, inclusive, and easily searchable online art resources available today. Through a single, elegant gateway users can access — and simultaneously cross-search — an expanding range of Oxford’s acclaimed art reference works: Grove Art Online, the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, the Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, The Oxford Companion to Western Art, and The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms, as well as many specially commissioned articles and bibliographies available exclusively online.

The Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year 2013 is ‘selfie’. The Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year is a word, or expression, that has attracted a great deal of interest during the year to date and judged to reflect the ethos, mood, or preoccupations of that particular year and to have lasting potential as a word of cultural significance. Learn more about Word of the Year in our FAQ, on the OUPblog, and on the OxfordWords blog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Selfies and the history of self-portrait photography appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPhantoms and frauds: the history of spirit photographyLanguage history leading to ‘selfie’Shanghai rising

Related StoriesPhantoms and frauds: the history of spirit photographyLanguage history leading to ‘selfie’Shanghai rising

Benjamin Britten, revisited

When I was charged with the task of updating the article on Benjamin Britten in Grove Music Online, I thought it would be a relatively simple matter. As Britten’s centenary year approached, it seemed an opportune moment, and the article was one I admired. But I soon found myself in an authorial quandary. The article was first published (in print form) in 1995, and was written by a revered scholar, Philip Brett, who died in 2002 at the age of 64. Brett was one of the first critics to publicly address the issue of Britten’s homosexuality and its relationship to his music. This was in 1977, only a year after Britten’s death, and Brett went on to become a leading figure in sexuality studies in music. (The American Musicology Society’s award for scholarship on LGBT themes is named after him.) The 1995 Grove article was one of his later pieces of writing, and since he never completed a planned book on Britten, it was the culmination of many years of work on the composer. It seemed odd to tinker with Brett’s words, given that the article was a monument to Brett’s scholarship as well as Britten.

But revisiting Brett’s article was an education in how much Britten scholarship and performance has changed since 1995, or even since I began working on Britten a few years later. The bibliography has nearly doubled, and scholarly perspectives have multiplied, losing much of the defensive tone that still persisted 10 or 15 years ago. Something has shifted to render Britten’s place much more secure. The broad rethinking of modernism that has taken place since the mid-1990s leaves Britten—with his commitment to communication and accessibility—a less marginal figure. Interest in Britten has grown outside English-speaking countries, and it continues to spread. There are now Britten biographies in French, German and Italian. This year, Beijing is hosting a celebration of Britten in his centenary week, which will see many first performances in China, as well as the release of a new biography. Once-marginalized works are increasingly being performed—not so much, I think, because people find these works more successful than they once did, but because their very failures are interesting, and there’s less of a sense that some of Britten’s works need to be sequestered for fear of tarnishing his reputation.

Publicity photograph of British composer Benjamin Britten, 1968. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In my updated version of the Grove entry, perhaps the most substantial changes are to the slightly apologetic discussions of The Rape of Lucretia, Paul Bunyan, and Gloriana. Reflecting what I think are larger shifts in Britten scholarship, I occasionally replaced Brett’s personal and psychological explanations with historical and practical ones. On the founding of Britten’s Aldeburgh Festival, for instance, Brett writes, “It was an inspired response to Britten’s vulnerability, personally as well as musically, to the kind of hostility he had experienced early in his operatic ventures.” Drawing in part on recent scholarship by Paul Kildea, I cut this and wrote, “It was in many ways a practical move, providing a base for the English Opera Group after its association with Glyndebourne broke down, and taking advantage of the Arts Council’s interest in funding cultural projects outside London.” In making this change, of course, I also elided Brett’s slightly protective reference both to Britten’s inspiration and to the “hostility” he experienced. Elsewhere, Brett’s image of an oppositional Britten, speaking truth from the margins, is counterbalanced—perhaps, in the end, superseded—by a sense of Britten’s music as negotiating “the contradictions of modernism and mid-20th-century modernity: finding a middle ground between communication and exploration and between tradition and the new, and responding in sophisticated ways to its political and cultural moment.”

Brett’s article was always one of the more personal and idiosyncratic in Grove. This was part of its attraction. Once I was to take at least partial responsibility for it, though, I found myself wanting a bit more distance, and this put me in a bind. What could be worse than erasing Brett’s singular voice at its most personal? After all, Brett’s approach was quite explicitly rooted in his own identity as a gay man who, like Britten, had struggled to live openly and without shame, and to find connections between his homosexuality and public life. But the intimate and sometimes defensive tone of the article, I decided, made it feel precisely “dated,” rooted in the particular musicological and social environment of the mid-1990s (the same environment that produced Humphrey Carpenter’s then slightly scandalous biography of Britten, now largely displaced). So I adjusted it, revising sections that felt to me most rooted in musicology circa 1995.

These included forays into amateur psychoanalysis and affirming descriptions (along with unverifiable judgments) of Britten’s sexual life. Brett had long been committed to the idea that Britten, as a marginalized figure himself, would identify with other oppressed groups, but he seems to have changed his mind shortly before writing the Grove article, and his disappointment in Britten’s failure to identify with other “others” is palpable. “This limitation,” Brett writes, “is perhaps the chief reason his greatness needs to be qualified.” This sense of disappointment, too, I tended to elide, since I don’t find Britten more sympathetic to women and non-Western “others” than any other composer, nor do I expect him to be, based on his sexual preference, particularly given his position of relative privilege.

I spent months taking passages out and putting them back, trying to find the right approach to what seemed like a fairly impossible task. I expect the Grove Music Online Britten article will continue to evolve over the years. However, Brett’s influential print article will remain.

Heather Wiebe is a lecturer in 20th century music at King’s College, London. She is a member of the editorial board of The Opera Quarterly and a contributor to Grove Music Online. She is the author of Britten’s Unquiet Pasts: Sound and Music in Postwar Reconstruction (Cambridge, 2012).

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Benjamin Britten, revisited appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA perfect ten?A few things to remember, this fifth of NovemberSofia Gubaidulina, light and darkness

Related StoriesA perfect ten?A few things to remember, this fifth of NovemberSofia Gubaidulina, light and darkness

The vanished printing houses

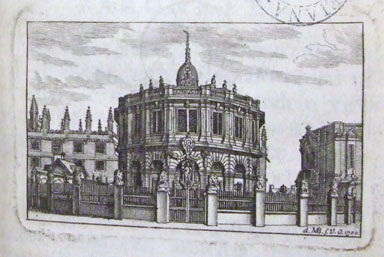

Someone on even the most cursory visit to Oxford must surely see two fine buildings that once housed the University Press: the Sheldonian Theatre and the Clarendon Building, close to each other on today’s Broad Street. If they venture further afield, perhaps heading for the restaurants and bars along Walton Street, they also can’t fail to notice the neo-classical building that has been the Press’s current home since 1832. What they’ll never see however is the Press’s second home. Because it’s no longer there.

To begin at the beginning . . . when the University founded its own Press in order to print books of scholarship, it needed a suitable building to house the type and printing presses and the whole business of book manufacture. Now, there had long been an ambition to move the University ritual of ‘the Act’ — often a raucous and profane affair — out of the sacred space of the University church of St Mary the Virgin. The solution was a new building: Wren’s Sheldonian Theatre. And a theatre it surely was, a place where University ritual — and dissections — could be performed and witnessed. However, in an attempt to kill three birds with one stone it was also decided that the nascent University Press should also be housed there. It’s hard to see this as anything but a temporary expedient: the grand auditorium was hardly a place to install a factory for books, yet that was what happened. In 1669 five wooden printing presses went down into the cellar beneath the auditorium floor, while the racks of cases of type and the frames at which compositors stood when composing type were squirrelled into the spaces beneath the galleries. Damp printed sheets were hung on suspended poles wherever there was room. And when the University needed the Theatre for its primary purpose, much of this materiel had of course to be moved out and the work of the Press was disrupted for the duration.

The ‘Little Print-house’ peeps over the Theatre Court Wall to the left of the Theatre

This was hardly an ideal situation and, not surprisingly, within just a couple of years plans were laid to move out. Right next door to the Theatre, on its east side, was a small house known locally as Tom Pun’s House, and a Mr Delgardno was paid to remove himself and make way for some of the Press’s printing activities; we can see what became known as the ‘Little Print-house’ on an engraving of the Theatre by Michael Burghers. Better still, between that house and the high wall that surrounded the Theatre was a narrow strip of land which the University owned and on which the University now proceeded to build a long, single-storey, wooden building, glazed and slated, into which the compositors and press-crews decamped with their equipment. Though far from grand it was no doubt a great deal more suitable and comfortable than the elegant but inappropriate surroundings of the Theatre. We can clearly see this ‘New Print-house’ on David Loggan’s bird’s-eye-view engraving of Oxford of 1675.

The single-storey ‘New Print-house’ nestles under the Theatre Court Wall

In subsequent years the University continued buying up the lease of the tenements bordered by the Little Print-house on the west, Catte Street on the east, Canditch on the north, and the Schools on the south, and yet more wooden buildings were erected for the Press, in particular one to house a type foundry where the Press could make its own metal printing type, a unique facility that freed it from dependence on London typefounders. All very homely. But the desire at the highest level for the University’s Press to take its proper, dignified place in the heart of the University never went away and architect Nicholas Hawksmoor was engaged to design a new, dedicated printing-house that would stand alongside the Theatre on a line through the Schools. It was time for all those wooden buildings — hardly a matter of pride to the University, we might guess — to be brushed aside, and in early 1712 the workmen and their equipment all moved back into the Theatre while their home of decades was razed and the new edifice — the Clarendon Building — raised. By late 1713 its two equal halves were home to the Learned Press and the Bible Press, one on ‘Learned Side’ (to the west) and the other on ‘Bible Side’ (to the east).

The visitor who stands today on the bleak gravelled area between the Schools and the Clarendon Building might be surprised to know that they stand among the ghosts of a clutch of wooden buildings in which Oxford University Press printed its books and where men set type and pulled at their printing presses three centuries before.

Martyn Ould is an independent researcher who has written on the printing history of OUP, most recently contributing three chapters to volume 1 of The History of Oxford University Press. He is a practising letterpress printer, operating The Old School Press with his wife. The first volume of his own four-volume study Printing at the University Press, Oxford 1660-1780 is planned for publication in 2014. He is a Visiting Scholar at the Book Text and Place 1500-1750 Research Centre at Bath Spa University.

With access to extensive archives, The History of Oxford University Press is the first complete scholarly history of the Press, detailing its organization, publications, trade, and international development. Read our previous posts about the History of Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The vanished printing houses appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPicturing printingA brief history of Oxford University Press in picturesWhen did Oxford University Press begin?

Related StoriesPicturing printingA brief history of Oxford University Press in picturesWhen did Oxford University Press begin?

Violet-blue chrysanthemums

Chrysanthemums (Chrysanthemum morifolium) are the second best-selling flowers after roses in the world. In Japan, they are by far the most popular and the 16 petal chrysanthemum with sixteen tips represents the Imperial Crest. Cultivated chrysanthemums have been generated by hybridization breeding of many wild species for hundreds or possibly thousands of years. Their flowers are pink, red, magenta, yellow, or white, but never violet-blue because chrysanthemums lack the key gene (the so-called blue gene, flavonoid 3′,5′-hydroxylase (F3′5′H) gene) to synthesize the delphinidin-based pigments which most violet-blue flowers accumulate.

Bluish-colored cultivars are not available in major cut flowers such as rose, carnation, chrysanthemum, lily, and gerbera due to the deficiency of F3′5′H gene. Genetic engineering techniques have enabled expression of the F3′5′H gene in rose (Rosa hybrida) and carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus) leading to novel varieties with violet-blue hued flowers accumulating delphinidin-based anthocyanins. The color-modified carnations are sold in USA, EU, Japan, and other countries; the rose is sold only in Japan. Until now comparable genetically modified chrysanthemum varieties had not been developed due to recalcitrant and unpredictable expression of introduced genes; the chrysanthemum tends to shut them off by as yet unknown mechanisms.

For the first time, research teams at Florigene, Suntory, and at NARO Institute of Floricultural Science (NIFS) developed distinct genetic engineering approaches to create the long-desired violet-blue chrysanthemums, the results of which were recently reported in two papers published in the international journal Plant and Cell Physiology.

After incalculable trial and error experiments over the past 15 years, two tactics have now been found to be effective for creation of stable color modified chrysanthemum varieties. The NIFS and Suntory team of Naonobu Noda et al. optimized F3′5′H transgene expression in decorative-type chrysanthemums. They found that the use of a petal-specific promoter (the DNA sequence which lets genes work) from chrysanthemum flavanone 3-hydroxylase gene driving a canterbury bells (Campanula medium) F3′5′H gene is most suitable for production of delphinidin-base anthocyanin in the petals of chrysanthemum. The content of delphinidin in the petals of the transgenic chrysanthemum ranged as high as 95% of total anthocyanin and substitution of anthocyanin chromophore from cyanidin to delphinidin dramatically changed chrysanthemum ray floret color from magenta/pink to purple/violet.

In a second approach, described by Filippa Brugliera et al., the team of Florigene and Suntory found that expression of a pansy F3′5′H gene under the control of a chalcone synthase promoter from rose resulted in the effective diversion of the anthocyanin pathway to delphinidin, producing transgenic daisy-type chrysanthemums. The resultant flower color was bluish with 40% of total anthocyanidins based on delphinidin. Even higher levels of delphinidin (up to 80%) were achieved by down- regulation of the pathway leading to cyanidin-based pigments.

In both studies, delphinidin accumulation led to changes to bluish flower color hues unable to be obtained by conventional chrysanthemum breeding. The new flower color seems to be stable (and consistently beautiful!) in glasshouse trials. Since they are genetically modified plants, government permissions are necessary to release them to the environment for commercialization. This may present a significant challenge, as absolute sterility may be required in some countries to prevent out crossing to wild species.

Nevertheless, these findings have opened the door to more colorful chrysanthemums at the florist. Both teams continue their research: to obtain flowers with a sky blue color and varieties with sterility.

Naonobu Noda is a senior researcher at NARO Institute of Floricultural Science (NIFS), Japan. In 1995, he graduated from the Faculty of Agriculture, Tokyo University of Agriculture and in 2000 he obtained his Ph.D. in Agriculture at Kagoshima University. After moving to Aomori Green BioCenter, Aomori Prefectural Agriculture and Forestry Research Center (from 2000-2007), he joined NIFS where his research focuses on the development of blue-colored chrysanthemums. He is co-author of the paper ‘Genetic Engineering of Novel Bluer-Colored Chrysanthemums Produced by Accumulation of Delphinidin-Based Anthocyanins’, which appears in Plant Cell Physiol (2013) 54 (10): 1684-1695 (doi: 10.1093/pcp/pct111).

Yoshikazu Tanaka is general manager at the Research Institute of Suntory Global Innovation Center Ltd. After gaining a master’s degree from Osaka University, he joined Suntory Ltd. and obtained a doctoral degree at Osaka University. Since 1990, he has been working on genetic engineering of flower color modification and has successfully generated and commercialized novel blue/violet hued transgenic carnations and roses, also published in Plant & Cell Physiology (Plant Cell Physiol (1998) 39 (11): 1119-1126 and Plant Cell Physiol (2007) 48 (11): 1589-1600; doi:10.1093/pcp/pcm131, respectively). His latest work on the generation of violet/blue Chrysanthemums is reported in Plant Cell Physiol (2013) 54 (10): 1684-1695 (doi: 10.1093/pcp/pct111) and in Plant Cell Physiol (2013) 54 (10): 1696-1710 (doi: 10.1093/pcp/pct110).

Plant & Cell Physiology (PCP) is an international journal publishing high quality original research articles on broad aspects of biology, physiology, biochemistry, biophysics, chemistry, molecular genetics, epigenetics, and biotechnology of plants and interacting microorganisms.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only earth, environmental, and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: All images courtesy of the scientists via Plant & Cell Physiology. Do not reproduce without prior written permission.

The post Violet-blue chrysanthemums appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHelping smokers quit during Lung Cancer Awareness MonthWorn out wonder drugsAlcohol marketing, football, and self-regulation

Related StoriesHelping smokers quit during Lung Cancer Awareness MonthWorn out wonder drugsAlcohol marketing, football, and self-regulation

November 20, 2013

Language history leading to ‘selfie’

To celebrate selfie’s tenure as Word of the Year, here are some WOTYs from the past, which may shed some light on its development.

1839—daguerreotype. This was the earliest easily practicable photographic process, which employed a silver plate that had been sensitized to light by iodine. The plate was put in a camera and exposed to sunlight for three to thirty minutes. The exposed plate was held over hot mercury vapor until an image appeared, and finally desensitized by submersion in a hot solution of common salt.

The term daguerreotype spread quickly through the English language as name for both this process and its finely-detailed, silvery product, helped along by the French government’s decision to release Louis Daguerre’s method as a free gift to the world (he got a lifetime pension in return). Photograph—referring more generally to any image made by a camera—also made its first appearance in 1839, but it took a couple of decades before it became the most common word for such an image.

Just two months after Daguerre’s process was publicized, Philadelphian Robert Cornelius set up a camera and sat perfectly still in front of it for 15 minutes, producing the world’s very first selfie. Having nowhere to post it, he contented himself with opening a photographic studio. (He has had quite the internet afterlife, though, being featured prominently on sites such as My Daguerreotype Boyfriend and Bangable Dudes in History.)

The first selfie. After 174 years and billions of tries, this has never been improved upon.

1586—self-. Around this year, there was a sudden explosion of “self-” words. Self is an Old English word and had been in common use as a pronoun and adjective as far back as our records go. Near the end of the 16th century, however, it spawned dozens of compounds, from self-destruction, self-flattering, self-guard [“reserve”], and self-seeking [“selfishness”] (1586)* to self-liking (1561), self-love (1563), self-murder (1570), and self-assurance (1595). In this period, there was an increasing interest in self-examination (a later word; 1647) and consideration of people as individuals as opposed to members of a family, church, or society. The various Puritan sects prominent at the time laid strong emphasis on one’s personal relationship with God, and encouraged believers to scrutinize their consciences daily to tally up the ways in which they had sinned and the ways in which they managed to avoid temptation. The first diaries, records of these spiritual examinations, date from this period. The fact that many of the sixteenth-century self- compounds have quite negative connotations indicates that even as the idea of individuality was spreading, there was cultural unease about the degree to which it can shade into narcissistic self-conceit (1593) or self-regard (1595).

Selfie cleverly mitigates the self-pride (1586, again)—the ostentatious narcissism—associated with taking a picture of oneself and broadcasting it over social media to be “liked.” The “ie” suffix has been an English diminutive since the 15th century, making the nouns to which it is attached sound cute and child-like—laddie (1546), grannie (1663), and dearie (1681), for example.

1000—friend. This is one of the oldest words in our language, found in Beowulf and other Anglo-Saxon texts. It has been used as a verb—“to friend,” meaning to make friends—since the thirteenth century, but of course only since the beginning of the 21st century have these friends been virtual. It is integral to the definition of selfie that these online friends see it; it must be distributed on social media. There is a rather bleak way to look at this. Selfies are a sign of the growing isolation of people in modern life. People in the past didn’t take selfies, because they had friends in the Beowulf sense of the word to take pictures for them. Numerous contributors to Urban Dictionary, a popular site about contemporary slang, make similar points about the selfie: “You can usually see the person’s arm holding out the camera in which case you can clearly tell that this person does not have any friends to take pictures of them so they resort to Myspace to find internet friends.”

Melissa Mohr takes a selfie. Image courtesy of the author.

We can put a more positive spin on this trend too. Like Robert Cornelius, people have always wanted to make pictures of themselves. In the past, however, this was hard to do. Painting a self-portrait demanded skill and time, and was often financially irresponsible, as it was better to paint a picture of someone else, who could pay you. When photography began, it was at first difficult to sit still long enough, then hard to focus the camera, and expensive to develop the film. Now with iPhones and digital cameras, you can take hundreds of photos before finding the perfect one where you’re not blurry, both eyes are open, and most of your head is in the shot. Selfies are cheap and easy, and give us the chance to get great pictures of ourselves in front of the sunset, next to a really cute cat, or in a really cute outfit in front of the mirror, even if there is no one else around.

Melissa Mohr received a Ph.D. in English Literature from Stanford University, specializing in Medieval and Renaissance literature. Her most recent book is Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing. Watch a video about the history of swearing.

The Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year 2013 is ‘selfie’. The Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year is a word, or expression, that has attracted a great deal of interest during the year to date and judged to reflect the ethos, mood, or preoccupations of that particular year and to have lasting potential as a word of cultural significance. Learn more about Word of the Year in our FAQ, on the OUPblog, and on the OxfordWords blog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: (1) Robert Cornelius, self-portrait, 1839. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

*Note: The 1586 self- words are from Philip Sidney’s Arcadia, a heavily-used source text for the OED‘s 1911 editors. It is likely that many of these words will be backdated when the dictionary is revised.

The post Language history leading to ‘selfie’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEdwin Battistella’s wordsScholarly reflections on the ‘selfie’The year in words: 2013

Related StoriesEdwin Battistella’s wordsScholarly reflections on the ‘selfie’The year in words: 2013

A perfect ten?

On 10 July 2013, a potential 50 playing days of Test cricket — ten consecutive Test matches of up to five days each — between England and Australia began. Try explaining to an American how two national teams can play each other for 50 days (or even five days). Or how a match can be ended by “ bad light” in a floodlit stadium. As the distinguished cricket and music writer Neville Cardus wrote, “Where the English language is unspoken there can be no real cricket, which is to say that Americans have never excelled at the game”. Cardus was perhaps unaware that the world’s oldest international sporting rivalry is not England against Australia, which began in 1877, but United States against Canada. A match between these two great cricketing nations was played in Manhattan in 1844. Try explaining that to an Englishman.

For the dedicated follower — people who, like me, have travelled 9,000 miles to watch a match or, if they have to remain at home, stay up all night watching or listening to coverage — England vs. Australia is the ultimate sporting rivalry. The Ashes, as Anglo-Australian bilateral cricket series have been called since 1882, appeal strongly to casual sport fans. For many it’s the only cricket they ever watch. The prestige of The Ashes has always partly been its relative infrequency – each team visits the opposition once every four years.

However, after the ten-match run in 2013–14 Australia will be in England again in 2015. Three series and 15 Tests in only 36 months is perhaps taking for granted the goodwill and spending power of the public and the durability of the players. On 30 July 2013 the draw for the 2015 World Cup was made. The co-hosts Australia will be in the same pool group as England; they will play the opening match of the tournament on 14 February at the MCG.

This year and next year — and the year after that — the players might look at the opposition and think to themselves, “oh no, not you again…” Too much of a good thing? Match receipts suggest not. Tickets that could be purchased upon release for less than £100 were being offered by ticket agencies at up to £1,000. Demand is insatiable because sport is entirely unpredictable. Not even the finest cricketers can control the weather or freak injuries.

This Ashes decathlon is not unprecedented but it is uncommon. The last time England and Australia played ten consecutive Tests against each other was in 1974–75, with six Tests in Australia followed by four in England. The inaugural World Cup was a caesura between the two series.

In 1920–21 there were five Tests in Australia and then five in England. Captained by the hardnosed and imposing “big ship” Warwick Armstrong, Australia won 5–0 at home, the first time that England had been whitewashed in a five-match Ashes series and not repeated until 2006–7. Five and five, home and away, was also the basis of two consecutive series in 1901–2.

History suggests that England will struggle Down Under this winter; Australia has always won back-to-back series. An England victory in 2013–14 would be an historic first. But form says that England will prevail.

In 43 Tests from 1989 to 2005 Australia won 28 to England’s seven. It’s not that long ago that some people were suggesting that an Ashes series should be of three matches. The Aussies were bored with winning so easily; the Poms were worn down by constant beatings. India and South Africa provided more of a contest for Aussie cricketers and more of a spectacle for supporters.

The sensational 2005 Ashes, when England regained the urn after losing every series since 1989, changed all that. Since then that little urn has been harder fought for than ever. From 2001 to the 2010–11 series 30 Tests were played with 25 results and only five draws. The Ashes have never been more competitive.

England’s captain Alistair Cook and Australia’s Michael Clarke make a fascinating, diametrical contrast: Cook the country boy and Clarke the city boy; the English accumulator and the Australian stroke player. Cook is a cautious leader, more often seeking to avoid losing than pursuing a win at all costs, a reminder of the dour 1960s. Unlike Clarke he inherited a strong, successful team; his task is business as usual. Clarke’s job is to reinvigorate Australian cricket, as Allan Border did in the late ’80s. But some commentators have questioned his aptitude and appetite for the job. In recent years his own playing form has been majestic but the team has continued to struggle.

Cricket is constantly evolving. “Nothing is so fleeting as sporting achievement, and nothing so lasting as the recollection of it,” wrote the historian Greg Dening. England dominates now. In 20 years it might be Australia again. So it goes.

Stuart George is a freelance writer in London. He was UK Young Wine Writer of the Year in 2003 and reviews cricket books for the Times Literary Supplement. He is the author of the forthcoming Sports Biographies in Oxford Reference.

Oxford Reference is the home of Oxford’s quality reference publishing, bringing together over 2 million entries, many of which are illustrated, into a single cross-searchable resource. With a fresh and modern look and feel, and specifically designed to meet the needs and expectations of reference users, Oxford Reference provides quality, up-to-date reference content at the click of a button.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only sports articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: The Ashes Urn. By danielgreef [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The post A perfect ten? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLooking back: ten years of Oxford Scholarship OnlineShanghai risingTen obscure facts about jazz

Related StoriesLooking back: ten years of Oxford Scholarship OnlineShanghai risingTen obscure facts about jazz

“Stunning” success is still round the corner

There are many ways to be surprised (confounded, dumbfounded, stupefied, flummoxed, and even flabbergasted). While recently discussing this topic, I half-promised to return to it, and, although the origin of astonish ~ astound ~ stun is less exciting than that of amaze, it is perhaps worthy of a brief note.

I sometimes refer to Franciscus Junius the junior (1591-1677), who even in the constellation of his great contemporaries shines with special brightness. His posthumous etymological dictionary of English, written (fortunately) in not too florid Latin, has been one of my favorite sources for more than twenty years. Junius lived before the discovery of sound correspondences (without which etymology is unprofitable guesswork), but he knew so much and his intuition was so great that his opinion should never be dismissed without giving it some consideration. However, in this case he was wrong. He thought that astonish has the root stone. Fear, sorrow, and admiration “petrify” people, he said, and cited Latin lapidescere “turn into stone.” Despite the Latin parallel, the metaphor at the foundation of astonish is different. The English verb goes back, via French, to Latin extonare, in which tonare means “to thunder.” To be astonished is, from an etymological point of view, to be “thunderstruck.”

I sometimes refer to Franciscus Junius the junior (1591-1677), who even in the constellation of his great contemporaries shines with special brightness. His posthumous etymological dictionary of English, written (fortunately) in not too florid Latin, has been one of my favorite sources for more than twenty years. Junius lived before the discovery of sound correspondences (without which etymology is unprofitable guesswork), but he knew so much and his intuition was so great that his opinion should never be dismissed without giving it some consideration. However, in this case he was wrong. He thought that astonish has the root stone. Fear, sorrow, and admiration “petrify” people, he said, and cited Latin lapidescere “turn into stone.” Despite the Latin parallel, the metaphor at the foundation of astonish is different. The English verb goes back, via French, to Latin extonare, in which tonare means “to thunder.” To be astonished is, from an etymological point of view, to be “thunderstruck.”

The complications in this seemingly neat story are of a phonetic nature. From extonare Old French had the verb estoner, with the past participle estoné, which in Anglo-French became astoné. Astoné yielded Middle Engl. astounen, and quite late (no examples in the OED predate 1600) we find the verb astound. There is some disagreement about how final d appeared in it. According to the traditional view, this consonant was excrescent, that is, added “for no etymological reason.” (Compare t in amongst, whilst, and the substandard but very common form acrosst; the last name Bryant, from Brian, grew -t possibly on analogy of words like pliant, defiant, and vibrant.) Words with such superfluous -d after n are common. Among them we find sound (the root of Latin sonus, as in Engl. assonance and sonata, ends in -n), expound (Latin exponere), and bound, as in the ship is bound for London (from boun “ready,” here possibly under the influence of bind—bound, as though the ship had a binding obligation to go to London). There was also the adjective astound, and the OED (in an entry published in 1885) considered the possibility that it was taken for the past participle of the nonexistent verb; allegedly, usage could convert astounen into astound. Professor Diensberg, a leading specialist in the history of French words in English, rejected this reconstruction unconditionally. We may afford the luxury of staying above the fray, for our goal is to discover the ultimate origin of astound rather than its subsequent history.

Now, the participle astoné (see it above) belongs with the infinitive astone. Its English variants astonie and astony have also been recorded. They occur even in some nineteenth-century dictionaries, though at that time no one used them. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, a fashion for verbs ending in -ish set in. The Latin cluster -isk (with a long vowel) developed on English soil into -iss and -ish. Engl. -ish seems to go back to -ish directly, bypassing -iss (here I again follow Diensberg). Abolish, languish, nourish, and publish, among others, share the suffix -ish with astonish. Consequently, astonish and astound are etymological doublets, or cousins, if you wish. But family ties have never guaranteed tender feelings, and words behave in many respects like people: they fight for the sphere of domination and inheritance. Absolute synonyms do not exist. As a result, astound increased its force, outstripped astonish, and came to designate utter amazement rather than surprise, almost the state of being shocked.

Not too rarely an unstressed prefix consisting of a single vowel has been lost in English. James A. H. Murray called such forms aphetic (this adjective is his coinage). For instance, bide, cute, and squire are the aphetic variants of abide, acute, and esquire. Likewise, stun is, according to the OED, the aphetic variant of the verb astone, and indeed it means more or less the same as astound, except that one is often stunned with a blow. The difference in vowels and the absence of final -d in stun prevent modern speakers from connecting the two words. That might be the end of the story (a happy end: almost everything is clear), but for the existence of the Old English verb stunian “crash, resound, roar; impinge, dash.” Not improbably, the two sets, separated by a semicolon in my gloss, are not different senses of the same verb but homonyms. Stunian, regardless of whether it is one verb or two, has a respectable relative in German, namely staunen “to be astonished or amazed”; more common is the prefixed transitive verb erstaunen “astonish, amaze.”

A stunned cat

Old Icelandic had stynja “to groan,” with unmistakable cognates elsewhere: German stönen (from stenen), Russian stonat’ ~ stenat’ (stress on the second syllable), etc. The basic meaning of all such verbs seems to have been “making a noise.” Old Engl. stunian “impinge, dash” is related to the Old English noun gestun ~ gestund (already then with excrescent d!) “noise, crash” and stund “a strong effort.” Etymologists offer conflicting hypotheses on the origin of staunen, but most often one finds the statement that staunen came to Standard German from Swiss French, where it goes back to extonare. With extonare we return to familiar grounds. But Old Engl. stunian remains unexplained. Skeat derived stun from stunian and bypassed astound. He never gave up his etymology, which appeared early in his dictionary, and it looks good, even though stun emerged in our texts only in a thirteenth-century poem written by a native of northern England.

Regrettably, even our best dictionaries are wholly or partly dogmatic and are apt to shed words of wisdom, without alerting the user of conflicting opinions and unsolved riddles. The aphetic origin of stun is now a commonplace, and it is a pity that The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology, Wyld, and Weekley, our most reliable sources, say nothing about the troublesome verb stunian. In the last editions of his full and concise dictionary, Skeat traced stun to stunian, mentioned the verbs for “groan” as cognates, and did not even mention astound. Such is the state of the art. All this is sad but hardly astounding.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: (1) François Junius. 1698. Michael Burghers after Anthony van Dijck. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Cute young cat looking up in a total surprise. © Fotosmurf03 via iStockphoto.

The post “Stunning” success is still round the corner appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe “brave” old etymologyAmazing!“Deuce,” “doozy,” and “floozy.” Part 2

Related StoriesThe “brave” old etymologyAmazing!“Deuce,” “doozy,” and “floozy.” Part 2

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers