Oxford University Press's Blog, page 871

December 2, 2013

The neural mechanisms underlying aesthetic appreciation

Humans are apparently the only species to aesthetically enjoy the world around them. What is it that allows us to admire the elegance of a ballet dancer, or to enjoy the beauty of the sun’s reflection on the sea as it sets under the horizon? What aspect of our nature enables us to be moved by a piece of music, or by the sublime in a painting like Turner’s Shipwreck of the Minotaur?

Shipwreck of the Minotaur (ca. 1810)

Neuroaesthetics is precisely attempting to answer these sorts of questions. Cognitive neuroscientists are studying the brain mechanisms that give rise to aesthetic experiences. Brain lesion and neuroimaging studies have taught us quite a lot about the nature of aesthetic experiences. We know that it is a complex experience arising from the interaction among the nodes of a broadly distributed network of cortical and subcortical brain regions related to perceptual, cognitive, and emotional processes. These processes or underlying mechanisms are not specialized in aesthetic responses; they all play crucial roles in other domains of human experience, from perceiving small details in the world or making small decisions to abstract reasoning or establishing social relationships. Indeed, Friedrich Schiller referred to beauty as an aesthetic unity of thought and feeling, of contemplation and sensation, of reason and intuition, of activity and passivity, of form and matter.Can this extraordinary complexity be generated by neurons firing in specific regions of our brain? This question also applies to another extraordinary human experience: consciousness. Our approach is not inherently reductionist, but still, we are cognitive scientists. And, as such, we believe that aesthetic experience (as consciousness, in fact) indeed is caused in our brain, likely as a result of complex interactions between different brain regions.

One of these regions, the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (lDLPFC), seems to play a critical role in aesthetic appreciation. Several brain imaging studies have shown that activity in this region is greater when people view artworks and photographs they find beautiful or like more than when they view artworks and photographs they judge as not beautiful or like less. Thus, there are grounds to believe that the increase in lDLPFC activity observed during aesthetic appreciation is specifically related to the adoption of an aesthetic orientation towards visual images.

However, previous studies have relied on correlational evidence. But (taking from and freely interpret another recent blog post) “… correlation does not imply causation. At best it might be taken as indicative or symptomatic of it”. Accordingly, knowledge about the specific role of the lDLPFC in aesthetic appreciation was, until recently, mostly conjectural. We recently carried out an experiment that aimed to overcome these limitations. We used, for the first time, transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) to directly test whether the lDLPFC plays indeed a causal role in aesthetic appreciation of representational and abstract paintings. This technique uses electrical currents to enhance the excitability in targeted brain region. We expected that increasing activity in the lDLPFC via tDCS would lead to a greater appreciation for the presented pictures.

Our predictions were confirmed, at least partially. Our enhancement of activity in the lDLPFC produced an increase of aesthetic appreciation for figurative artworks and photographs, but not for abstract images. Critically, the effect on figurative images was specific for their aesthetic appreciation, and did not extend to other types of visual judgments, like the evaluation of colourfulness.

We believe that our findings show that the lDLPFC facilitates the disengagement from a habitual mode of identifying objects to adopt an aesthetic perspective. And artistically naive people, as the ones we tested, may be oriented aesthetically toward objects they understand or they do not (generally, abstract art) to a different extent. This without neglecting possible tDCS effects on mood: indeed, the lDLPFC is also known to be a critical region in emotional processing, and the enhancement of lDLPFC activity through brain stimulation reduces depressive symptoms.

In conclusion, our results show that the judgments of beauty can be artificially enhanced using brain stimulation. Emily Dickinson was only partially right: beauty certainly is, but it can also be enhanced… well, at least in our brain!

Zaira Cattaneo is at the Department of Psychology, University of Milano-Bicocca, Milano, and the Brain Connectivity Center, IRCCS Mondino, Pavia, Italy. Marcos Nadal is at the Department of Basic Psychological Research and Research Methods of the University of Vienna, Austria. They are the authors of the paper ‘The world can look better: Enhancing beauty experience with brain stimulation’, which is published in the journal Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience.

Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience (SCAN) provides a home for the best research that uses neuroscience techniques to understand the social and emotional aspects of the human mind and human behavior.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology and neuroscience articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Shipwreck of the Minotaur by J. M. W. Turner [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The neural mechanisms underlying aesthetic appreciation appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRadiology training and educationEchoes of The Iliad through historyA Q&A with Ingi Iusmen on international adoption

Related StoriesRadiology training and educationEchoes of The Iliad through historyA Q&A with Ingi Iusmen on international adoption

December 1, 2013

Radiology training and education

The entire structure of the Radiology professional board exam, the last but crucial hurtle after eight years of post-graduate training, changed this year. The old exam, that in place for decades, had two discrete elements. First, a written exam that included imaging physics followed by an oral exam that reviewed only diagnostic imaging that was taken at the end of training. One of the regular criticisms of this process was that the level of resident physics training was not sufficiently relevant to the practice of clinical radiology. While residents knew all about “bremsstrahlung” they were often uneasy about adjusting imaging parameters on a CT scanner or explaining the source of a common MR imaging artifact. The change to an entirely new exam format provided an opportunity to alter the focus of the physics questions with the expectation that residencies would therefore incorporate more practical physics in their resident’s education.

The challenge for residents and medical educators will be to make the changes necessary to prepare trainees for this exam. After forty years of preparing residents for the old exam, the physics curriculum is well established at most programs and presumably carefully refined over the years based on resident performance on their written exams. But change does not come easy and providing the necessary lectures and training will require a close collaboration between the clinical radiologists and medical physicists that may not have existed before.

MAGIC ANGLE EFFECT

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

On this short TE (30) image this bovine tendon appears bright around the bend. This phenomenon is called “magic angle effect”.

Inadvertent water suppression

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

On this axial fat suppressed scan notice how this tumor appears dark along its lateral border (arrow). This is an artifact from inadvertent water suppression due to inhomogeneity of the magnetic field.

ENTRY SLICE BRAIN SAG

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

This sagittal image demonstrates high signal in the cortical veins overlying the brain but with low signal in the transverse sinus (arrow). This is because the cortical veins are flowing from lateral to medial and into the volume of brain scanned. This phenomenon is called “entry slice enhancement”. Since the protons from outside the scan volume have not previously experienced a 90 degree pulse there are more protons available to provide signal. The transverse sinus, however, flows from medial to lateral and so there are fewer available protons. This can be helpful clinically since the appearance of high signal in the transverse sinus would indicate that either its flow is reversed or it is filled with thrombus.

DERMOID 2

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Even though it looks as though this patient has a complex brain tumor (Dermoid 1) the fact that there is dark border on one side and bright border on the other of each mass indicates that it contains fat. This appearance is called “chemical shift artifact”. The CT more clearly shows the fat within Dermoid 2.

DERMOID 1

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Even though it looks as though this patient has a complex brain tumor (Dermoid 1) the fact that there is dark border on one side and bright border on the other of each mass indicates that it contains fat. This appearance is called “chemical shift artifact”. The CT more clearly shows the fat within Dermoid 2.

Radiology requires both detection and analytic skills since there are really two elements to making a diagnosis. First, the radiologist must detect the abnormality so the first decision is establish whether the study is normal or abnormal. If the imager decides it is abnormal, the next decision is whether it is clinically relevant, artifact, or normal variant. While detection skill depend on innate visual skills and experience, the analysis is almost entirely based on education. The ability to recognize imaging artifacts is essential so that they are not mistaken for disease, resulting in unnecessary follow up imaging or treatment. These are all examples of imaging artifacts that you will eventually encounter in your practice of radiology.

Alexander C. Mamourian MD is currently a Professor of Radiology at the University of Pennsylvania. He is the author of Practical MR Physics and CT Imaging: Practical Physics, Artifacts, and Pitfalls. He completed his residency in Radiology at the University of Vermont in 1982. Inspired by meeting Raymond Damadian MD that year he became the first MR fellow at the University of Pennsylvania in 1983. In his subsequent years of academic practice he has focused on MR and CT imaging as well as resident education.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Radiology training and education appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEchoes of The Iliad through historyEchoing John the Baptist at AdventEditing the classics, past and present

Related StoriesEchoes of The Iliad through historyEchoing John the Baptist at AdventEditing the classics, past and present

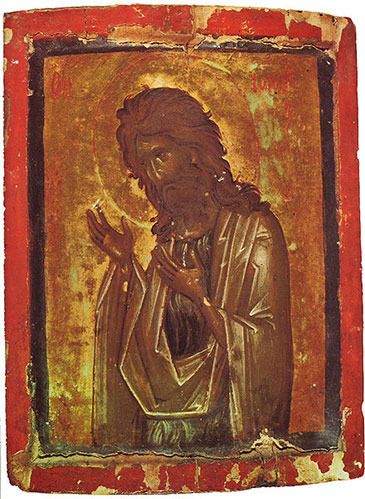

Echoing John the Baptist at Advent

The Christian Church, at its best, is remarkably honest. That characteristic is especially clear in the season of Advent, which calls Christians to look ahead toward the second coming of Christ the Lord of glory (what the New Testament calls his Appearing).

In this expectation, the Church identifies with John the Baptist, who prepared the way for the first coming. At the time, John, who had been faithful in his mission, was in prison, and Jesus did not seem to offer any help or hope. John was no longer sure that the one he had pointed out was indeed the Promised One. Perhaps he had been mistaken. After all, things had not gone as he had expected. There was no display of divine power, no sign of triumph. So John sent emissaries to put it to Jesus directly: “Are you the one who is to come, or are we to wait for another?” (Matt. 11:3).

John the Baptist: Icon from the late Palaiologos epoch, end of the 14th century. Painting by unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Christians today affirm that Jesus was indeed the one who had been promised and whom the world awaited. But looking around at the world as it is now and looking ahead to what has been promised in Scripture, they echo John’s doubtful question. There is no way to tell, no way to be sure. The condition of the world has not changed since biblical times; the coming of the one worshipped as the Savior of the world apparently has made little difference. One cannot help but wonder. An honest confrontation with what seems to be reality stirs doubt and a quiet voice whispers, “Maybe you are mistaken.”

Against that possibility, Christian people cling to the biblical promises and utter the great “nonetheless”. Although they are aware that they may be mistaken, nonetheless they hold the promises that God has made to be dependable. If they do not yet understand or see any clear signs of fulfillment, this may be an indication that the ways of God are far beyond human comprehension. The mind and work of God is greater than mortals can conceive. So in hope and expectation the Christian Church awaits and prays for the promised Appearing of the Lord.

Philip H. Pfatteicher is a Professor of English and Religious Studies Emeritus, East Stroudsburg University of Pennsylvania and sometime Adjunct Professor of Sacred Music at Duquesne University. He is the author of Journey into the Heart of God: Living the Liturgical Year. Read his previous post on the Holy Cross.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Echoing John the Baptist at Advent appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPlato’s mistakeThe Holy CrossRowan Williams on C.S. Lewis and the point of Narnia

Related StoriesPlato’s mistakeThe Holy CrossRowan Williams on C.S. Lewis and the point of Narnia

HIV/AIDS: How to stop the unstoppable?

It is over 100 years since HIV, the AIDS virus, began spreading in humans. It all started in West Central Africa where, scientists calculate, HIV jumped from chimpanzees to humans around 1900. Then in 1964 the virus made its first trans-continental flight. In one move it leaped from Kinshasa, capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo, to the Caribbean island of Hispaniola. Here it established a foot-hold in Haiti before travelling on to the US in 1969. So began a journey that took HIV to virtually every country in the world, eventually infecting 65 million people, a figure that is rising by around three million annually.

Without a doubt the best way to halt this spread is with a vaccine against HIV but none of the many preparations tested so far is effective. The bad news is that we are still decades away from having a licensed vaccine, so is there any good news to impart?

Startling headlines earlier this year reported a breakthrough – a so-called ‘functional cure’ in an HIV positive baby. Surprisingly, the report came from the US where all pregnant women should get antenatal HIV screening. Nevertheless, this particular mother slipped through the net. She was unaware of her HIV infection until she tested positive during labour – too late to give her antiviral drugs to prevent virus transmission to the baby. So doctors gave the baby a course of antivirals, starting within 30 hours of birth. Although he/she initially tested positive for HIV, this soon became undetectable. After 18 months the treatment was discontinued, a process that usually causes the virus to bounce back. But in this case only traces of HIV were detectable after the treatment stopped. So although the drugs had not eliminated the virus completely, doctors think that the child’s immune system can now control the infection so that even without antivirals he/she will remain healthy and will not infect others.

This case may be a one off but around the same time French researchers reported similar ‘functional cures’, this time in adults. Fourteen of 70 patients given antivirals within 2 months of their initial HIV infection maintained undetectable virus loads that did not bounce back after stopping the drugs.

No one knows exactly how these functional cures occur or why they are restricted to a minority of those treated. Yet these two reports highlight the fact that early treatment benefits individuals infected with HIV and can also be used to block another loophole in our armament against the virus – that is, early transmission.

Early after infection, when people feel well and are unaware that HIV is silently invading their bodies, the viral load in the blood and body fluids is extremely high. The combination of unawareness and high levels of circulating virus means that this is the time when the virus is most likely to be spread to others. So early diagnosis followed by antiviral treatment is the key to plugging this virus transmission route. This requires frequent testing of people at high risk of infection and one solution is to allow wider access to HIV testing kits, for example in gay clubs, saunas, and at home – situations that are all presently on trial in the UK and elsewhere.

Other suggestions for curtailing HIV spread to people at very high risk, such as those with HIV positive sexual partners, are pre- or post-exposure prophylactic antivirals. The former mirrors the routine use of anti-malaria drugs for healthy travellers to malaria infested areas while the latter is modelled on the morning after contraceptive pill.

Obviously, without a vaccine, winning the fight against this rogue virus requires a multipronged approach using as many prongs as possible. We must not be complacent. We should acknowledge and build on the landmark introduction of highly active antiviral therapy in the 1990s that transformed the outlook of people living with HIV. Before this date HIV infection was a sure death sentence, afterwards virus carriers could expect a normal life span. Now we are learning how to use these drugs to achieve functional cures and effective preventative measures. Clearly much more needs to be done but the battle against HIV is well under way.

Dorothy H. Crawford has been Assistant Principal for Public Understanding of Medicine at the University of Edinburgh since 2007. Her books include The Invisible Enemy (OUP, 2000), Deadly Companions (OUP, 2007), Viruses: A Very Short Introduction (OUP, 2011), and Virus Hunt (OUP, 2013). She was elected a Fellow of both the Royal Society of Edinburgh and the Academy of Medical Sciences in 2001, and awarded an OBE for services to medicine and higher education in 2005. She has written several previous articles for the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: AIDS ribbon by Amada44. Image available via WikiCommons.

The post HIV/AIDS: How to stop the unstoppable? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIn memoriam: M. Therese SouthgateBrave new world?Detective’s Casebook: Unearthing the Piltdown Man

Related StoriesIn memoriam: M. Therese SouthgateBrave new world?Detective’s Casebook: Unearthing the Piltdown Man

November 30, 2013

Echoes of The Iliad through history

The Iliad was largely believed to belong to myth and legend until Heinrich Schliemann set out to prove the true history behind Homer’s epic poem and find the remnants of the Trojan War. The businessman turned archaeologist excavated a number of sites in Greece and Turkey, and caused an international sensation. While many of his claims and finds have since been discredited or discovered to be contaminated, he set many on the search to reveal life in Ancient Greece. A number of images that convey the real objects and places where scholars have drawn connections to the Trojan War (both historical and fictional) are included Barry B. Powell’s new translation of The Iliad and the slideshow below.

The Walls of Troy

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 0.4 - The translator standing before the walls of the sixth city at Troy.

The Skamandros River

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 21.1 - Two shepherds herd their sheep on a hill above the Skamandros River in the Troad. Homer seems to have had personal knowledge of the Troad and the river’s steep banks. Photo taken May 1, 1915.

“Cup of Nestor”

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 11.2 - From the fourth shaft grave at Mycenae (sixteenth century bc), this amazing solid-gold cup, excavated and named by Heinrich Schliemann in 1876, does bear a remarkable resemblance to the cup described in Book 11 of the Iliad. It could be said to have “four handles” with “two supports beneath” and “two doves” feeding at the handles, except that the birds seem to be falcons. In modern excavations on the island of Ischia in the Bay of Naples off the southern Italian coast, a modest clay pot was found with one of the two oldest known Greek inscriptions. It is from about 740 bc and may be a literary allusion. The inscription seems to refer to the text of Homer, one of the strongest pieces of evidence in our effort to date Homer. Whatever its exact meaning, somebody who knew how to write hexameters in the earliest days of Greek literacy inscribed this joke on the “Cup of Nestor.” It was later placed in a child’s grave and rediscovered in the mid-twentieth century.

Mycenaean Armor

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 10.1 - Little sense could be made of Homer’s description of the boar’s tusk helmet until in modern times actual specimens were found. Here is the only surviving example of a complete Mycenaean suit of armor, from a Mycenaean grave, c. 1400 bc, at Dendra in the Peloponnesus near Mycenae. The reconstructed boar’s tusk helmet is of a type most popular around 1600 bc, but pieces of helmets are found from as late as Homer’s own day c. 800 bc, so it was a traditional type of helmet in use for nearly a thousand years. The helmet Homer describes is an heirloom. Similar armor appears as an ideogram on Linear B tablets from Knossos, Pylos, and Tiryns.

Trojans and Achaeans Fighting Hand to Hand

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 8.2 - In this carving on a Lycian Tomb, Trojan and Achaean warriors fight in the hand-to-hand. The warrior on the left has just speared

his opponent, who falls dead. The figures are dressed as contemporary hoplites with round shields, horse-hair crested helmets, and shinguards. The Lycians, who lived in the southwest of Asia Minor, were not Greeks but were deeply influenced by Greek art and culture, and in Homer’s Iliad they are the most important Trojan allies. They used the Greek alphabet to record an unknown language and on this tomb carved many scenes from the fighting at Troy. Limestone relief on the tomb of a Lycian prince, from the west side of the Heroön of Goelbasi-Trysa, Lycia, Turkey, c. 380 bc.

Spring

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 5.3 - One of the four Horai or “hours, seasons,” Spring is shown as a young woman picking flowers and holding a basket of flowers. Her body is turned in the S-curve long favored by Greek sculptors. Fresco from a Roman private house in Stabiae, Italy, c. ad 60.

Greek Against Greek

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 4.2 - From three hundred or so years after Homer, both men are armed as hoplites, but the warrior on the left is in “heroic nudity,” except that he wears shinguards (greaves). The design on the shield of the naked warrior is probably a tripod, a metal object of high value. The warrior on the right wears bronze shinguards, a chest-protector (cuirass), and a helmet with horse-hair crest. Both fighters use the single thrusting spear. Athenian red-figure painting on a wine-cup from c. 450 bc.

The “Lion-hunt” Dagger

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 4.1 - Discovered by Heinrich Schliemann in the late nineteenth century, many scholars find remote echoes of this kind of fighting in Homeric accounts, preserved in the oral tradition. Here the shields are “like towers” and are carried by a strap around the neck, the telamon. On the far left a man wields a Cretan-style figure-of-eight shield, made of a convex frame covered by cowhides (unfortunately, no examples survive). The man wears no armor. He carries the single thrusting spear. Next is a bowman without shield. In the middle, the man’s shield is rectangular-shaped. The man to his right uses his figure-of-eight cowhide shield as protection against the lion, which he threatens with a single spear. In front him lies the body of a companion, killed by the lion. The companion also carried a rectangular tower-like shield, which stans upright. Gold, bronze, and niello, sixteenth

century bc, from Tomb IV, Mycenae.

A Typical Greek Warship

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 2.2 - Although this illustration is from the sixth century bc, its features are the same as earlier ships from Homer’s day. The steersman sits on a kind of platform at the rear of the ship, to the right, and steers with a large double-oar. The many rowers are represented as black circles, their shields affixed to the side. At the front of the ship, on the left, at the water line, is a ram for penetrating enemy craft, and, above, a chair for the captain (here unoccupied). The sail (not visible here) is attached to a mast that can be lowered into the belly of the craft on a kind of hinge when not in use. Ropes hold it in place. There is no jib so that such ships could only run before the wind; for this reason, much travel is by rowing. On an Athenian black-figure wine-cup, c. 530 bc.

The superimposed settlements of Troy, from c. 3000 bc to c. ad 100.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 0.3 - The enlarged illustration shows Troy VI, c. 1300 bc. (After drawing by Christof Haussner)

Sophia Engastromenos wearing the Jewels of Troy

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 0.2 - Having divorced his first wife in an Indiana divorce court, Schliemann married seventeen-year-old Sophia Engastromenos (1852–1932) in 1869, despite the thirty years difference in age. Here she is shown wearing jewelry that Schliemann found in 1873 in a level of the city that we now know is much too early for the Trojan War, c. 2400 bc. Schliemann called the cache “Priam’s Treasure.” Schliemann smuggled the jewelry out of Turkey and gave it to the University of Berlin. Feared lost after the Russian sack of Berlin in 1945, the jewelry emerged at the Pushkin Museum in 1994, but who owns it remains a matter of international dispute.

First Seven Lines of the Iliad

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 0.1 - This reconstruction is based on what we know about the earliest Greek orthography.

Barry B. Powell is Halls-Bascom Professor of Classics Emeritus at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. He is the author of a new free verse translation of The Iliad by Homer.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Echoes of The Iliad through history appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCharacters from The Iliad in ancient artMaps of The IliadAn interview with Barry B. Powell on his translation of The Iliad

Related StoriesCharacters from The Iliad in ancient artMaps of The IliadAn interview with Barry B. Powell on his translation of The Iliad

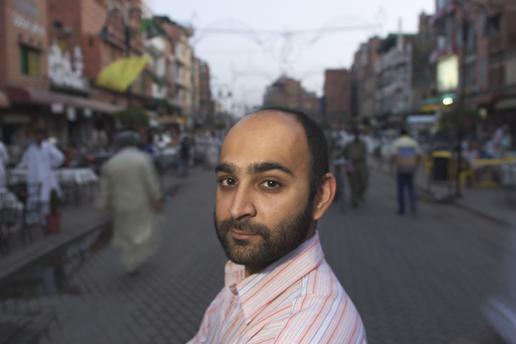

An interview with Mohsin Hamid

Mohsin Hamid is the author of the novels Moth Smoke, The Reluctant Fundamentalist, and How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia. His award-winning fiction has been featured on bestseller lists, adapted for the cinema, shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, and translated into over 30 languages. His essays and short stories have appeared in the New York Times, the Guardian, the New Yorker, Granta, and many other publications. Born in 1971 in Lahore, he has spent about half his life there and much of the rest in London, New York, and California.

Much of Mr. Hamid’s work focuses on issues relevant to his native Pakistan, namely globalization and the intersection of modernity and tradition. In the brief interview below, Mr. Hamid discusses these themes with the editors of Oxford Islamic Studies Online, an online resource designed to foster a more accurate and informed understanding of the Islamic world.

Mohsin Hamid © Ed Kashi

In a recent interview with Anis Shivani, you mentioned the development of the artistic community in Pakistan. “There may not be much support from the state,” you said at the time, “but there’s popular respect for the arts among people…people here care about fiction.” Can you elaborate on this? Have there been any specific events or trends in recent years that have helped or hindered the development of a modern Pakistani literary culture?

Mohsin Hamid: Pakistan has long had a modern literary culture—and has always had an ancient one for that matter. What’s new, perhaps, is the number of writers writing in English and the amount of attention they are getting abroad. Historically, as a society with low literacy, the dominant literary form has been poetry, which is popularized through song. Sung poetry is hugely popular and well known, and classical poets are venerated as saints. People visit their shrines, speak of them with veneration, even invoke them in prayers for blessings. It’s on that foundation that attitudes to modern literature in Pakistan are built. So there is real respect and warmth for the writer, for the notion of the writer. There is also suppression and violence towards the heterodox, which comes from the state and from militant groups. So literature exists in a state of tension, between real warmth on the one hand and real hostility on the other.

Along with a commentary on globalization, your novel How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia has an environmental message to it. The protagonist (the “you” of the story) is an enterprising young man who makes a fortune by selling filtered tap water as high-end mineral water, taking advantage of one of the many challenges facing growing urban centers in Asia. As a follow-up to the last question, are there any other social issues in this region that you would like to see more fiction writers address in their work? Are there pressing issues that they have so far shied away from, in your opinion? Any genres you’d like to see Pakistani writers explore, such as science fiction?

Mohsin Hamid: I’m a reader at least as much as I’m a writer. And as a reader I look for many things. Politics can be one of those things, but isn’t always. I look for language, for form. And also for plot. A rip-roaring yarn, well-written, is always a pleasure to read. I’m very intrigued by the new, by what I haven’t seen done before. And so, yes, good science fiction from Pakistan would be very exciting to me.

Many Western readers may be surprised to find that religion does not have a more overt role in your most recent novels. That is not to say that it has no role, but your work seems to suggest that the political dimension of religion has been muted, and that the more pressing concerns of unemployment, violence, and educational opportunities have a greater impact on a person’s life in modern Pakistan. Is this accurate? And how do you see the role of religion changing as Pakistani culture changes?

Mohsin Hamid: Actually, religion is important to all of my novels, especially the last two. The Reluctant Fundamentalist looks at the politics of religious identification as something separate from the spirituality of religion. It’s about religious tribalism in a way. How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia is about spirituality, and uses elements of Sufi tradition to examine a love-based spirituality as an antidote to the depression of modernity. Neither of them uses the word “religion” very much, but each explores a different side of phenomena that are religious.

Among the many influences for How to Get Filthy Rich you have discussed is the tradition of Sufi poetry. Like the mystical poets, you use a second-person narrative device. Can you go into more detail about how this tradition has influenced your work, and what specific Sufi masters have been the most important in this regard?

Mohsin Hamid: Attar, Rumi, Ghalib—the list of Sufi poets that I’ve been influenced by is probably longer than I can articulate, since in addition to those I’ve read, there are many more who have shaped the culture of Lahore in which I grew up. My first novel, Moth Smoke, was in a sense a post-modern riff on the Sufi theme of the love of a moth for a candle flame. Moth Smoke looked at what happened after such a love was consummated. What is interesting about Sufi thought is that, although it emerges from a Muslim tradition, it transcends religious groupings and can even transcend religious faith. It’s humanist in many ways. Yet it is also ancient, and has co-existed with much more orthodox forms of religion for well over a thousand years. That fascinates me. The Sufi notion that love enables transcendence fascinates me. I’m drawn to explorations that base their inquiry on what one feels, rather than on what one believes.

You have said that you finished the first draft of the novel The Reluctant Fundamentalist in the summer of 2001. How much did the events of 9/11 change the structure, tone, and themes of subsequent drafts? For example, was the unnamed American character who listens to the protagonist a product of the new political context?

Mohsin Hamid: The novel changed completely. The basic plot was the same: a Pakistani man grows a beard and moves back to Pakistan, leaving behind a well-paying job and doomed love affair in New York. But the tone, the voice, the style, the frame, the specific events—all of that changed. Before 9/11, there was no American listener in the novel. It was a quiet folk tale, a parable. Then it became something else. It had to.

You have discussed the issue of American drone strikes in your essays, short fiction, and even in a brief section of How to Get Filthy Rich. Besides your moral and political opposition of this type of warfare, is it safe to say that your work depicts this technology as a metaphor for the instability and conflict associated with globalization?

Mohsin Hamid: I think of drones as dehumanizing. Machines that can watch and kill. They are part of the general trend towards surveillance and violent intervention that we see all around us. I’m not saying that I think they should never be used. But I don’t think the way they are being used in the Pakistani context is helpful. They contribute to an infantilization of Pakistani discourse and a failure of Pakistan to tackle its problem of militancy itself. At a broader level, human beings and machines are integrating, and in the process human beings are becoming more machine-like. It’s not a development I find particularly beautiful.

Robert Repino is an Editor in the Reference department of Oxford University Press. After serving in the Peace Corps in Grenada, he earned an MFA in Creative Writing at Emerson College. His work has appeared in numerous publications, including The African American National Biography (2nd Edition), The Literary Review, The Coachella Review, Hobart, and JMWW. His debut novel Mort(e) is forthcoming from Soho Press in 2014. You can follow him on twitter @Repino1.

Oxford Islamic Studies Online is an authoritative, dynamic resource that brings together the best current scholarship in the field for students, scholars, government officials, community groups, and librarians to foster a more accurate and informed understanding of the Islamic world. Oxford Islamic Studies Online features reference content and commentary by renowned scholars in areas such as global Islamic history, concepts, people, practices, politics, and culture, and is regularly updated as new content is commissioned and approved under the guidance of the Editor in Chief, John L. Esposito.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the via email or RSS.

The post An interview with Mohsin Hamid appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTen fun facts about Claudio MonteverdiAmerican Academy of Religion/Society of Biblical Literature 2013 wrap upA journey through 500 years of African American history

Related StoriesTen fun facts about Claudio MonteverdiAmerican Academy of Religion/Society of Biblical Literature 2013 wrap upA journey through 500 years of African American history

A Scottish reading list from Oxford World’s Classics

By Kirsty Doole

This month’s Oxford World’s Classics reading list celebrates St Andrew’s Day by highlighting some of the great Scottish classics we have in the series. From the gothic tale of Jekyll and Hyde to Burns, and the philosophy of David Hume, there is hopefully something for everyone here. But have we missed out your favourite? Let us know in the comments.

Selected Poems and Songs by Robert Burns

No list of Scotland’s classics is complete without the Scottish Bard, Robert Burns. A lot of the work he produced is known around the world: it’s lyrical, acerbic, bawdy, and democratic. This edition of his selected songs and poems presents his work as it would have been first encountered by his contemporary readers by presenting the texts in the contexts in which they were origianlly published. His most famous pieces are here – Auld Lang Syne, To a Mouse, Tam O’Shanter – along with other, lesser-known works. It also contains letters, and a glossary of Scots words.

Margaret Oliphant

Hester by Margaret OliphantAlthough Mrs Oliphant moved to England when she was 10, she was originally from Midloathian and had lasting pride in her Scottish ancestry. In Hester, Catherine Vernon has risen to power in a man’s world as head her family’s bank. She thinks she sees through everyone but there are two people who resist her rule. One is the eponymous Hester, a young relation with a personality just as strong as Catherine’s, and as determined to find a role for herself.

The Man of Feeling by Henry Mackenzie

Robert Burns said that this was “a book I prize next to the Bible”. Harley, the hero, helps the down-trodden, loses his love, and fails to achieve any worldly success. The novel therefore asks a series of important questions that are just as relevant today as they were at the time of the novel’s publication in the 1770s: what morality is possible in a complex commercial world? Does trying to maintain it make you a saint or a fool? And is sentiment merely a luxury for the leisured classes?

The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner by James Hogg

This masterpiece is a rivetting account of murder, amorality, and a man’s descent into despair and madness. A young man, ‘an outcast in the world’, tells the story of his upbringing by a heretical Calvinist minister who leads him to believe that he is predestined for salvation and is therefore above the moral law. Falling under the spell of a mysterious stranger who bears an uncanny likeness to himself, he becomes a serial murderer.

Selected Essays by David Hume

Hume, a philosopher, economist, and historian, was born in Edinburgh in 1711. His philosophy rejected the possibility of certainty in knowledge, and he agreed with John Locke that there are no innate ideas, only a series of subjective sensations, and that all the data of reason stem from experience.

The Heart of Midlothian by Sir Walter Scott

This is regarded as one of Scott’s finest works. The Heart of Midlothian of the book’s title refers to Tolbooth prison in Edinburgh, and it is right at the core of this tale set around the 1736 Edinburgh riots. The people are infuriated by the actions of the Captain of the Guard and when news that his death has been reprieved by the distant monarch reaches them, they resolve to take their own revenge.

The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson

This short novel, published in the 1880s, was an instant classic. It was a Gothic horror that originated in a feverish nightmare, whose hallucinatory setting in the murky back streets of London gripped a nation mesmerized by crime and violence. The respectable doctor’s mysterious relationship with his disreputable associate is finally revealed in one of the most original and thrilling endings in literature.

Macbeth by William Shakespeare

The Scottish play! Dark and violent, Macbeth is also the most theatrically spectacular of the Shakespearian tragedies. Indeed, for 250 years it was performed with grand operatic additions set to baroque music. It dramatizes the corrosive psychological and political effects produced when evil is chosen as a way to fulfil the ambition for power. But why is there the superstition around saying the play’s name in the theatre? Apparently, it is down to the idea that Shakespeare used “real” spells in his text, purportedly angering the witches and causing them to curse the play. Thus, to say the name inside a theatre is believed to doom the production, and even cause physical injury to the cast members.

Kirsty Doole is Publicity Manager for Oxford World’s Classics. She is also Scottish.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog. Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Margaret Oliphant by Frederick Augustus Sandys (1829-1904) [public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A Scottish reading list from Oxford World’s Classics appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe uncanny Stephen CraneWalter Scott’s anachronismsEditing the classics, past and present

Related StoriesThe uncanny Stephen CraneWalter Scott’s anachronismsEditing the classics, past and present

November 29, 2013

Editing the classics, past and present

By Judith Luna

Actually, editing classics is just what I don’t do. My job can be a bit of a mystery to people who wonder whether I rephrase the occasional Jane Austen sentence, or improve Virginia Woolf’s punctuation. Most days I am looking for living authors, not dead ones: the editors and translators who are responsible for the introductions and notes, and who actually do make decisions about how best to present the texts for modern readers. Discussions about how far to modernize the spelling and punctuation of early works, and which edition of a text to use if a work went through multiple editions in an author’s lifetime are part of what goes into creating an Oxford World’s Classic (OWC) edition, and it is something I have always enjoyed.

My job as commissioning editor for the series hasn’t really changed in essentials since I started working on Oxford World’s Classics (then plain World’s Classics) when the paperback series was first launched in 1980. Then, as now, the main tasks are to identify which titles to include and to find the best editors and translators for the job. In the early days that role was undertaken by several editors who each looked after a separate part of the list and the aim was to grow the series as quickly as possible, publishing sixty or more titles a year. Texts were sourced from out-of-print, public domain editions and photographed rather than re-set, which resulted in a rather curious range of typefaces. We had access to earlier Oxford University Press (OUP) editions whose scholarly apparatus and copious textual notes could be pared down for a mainly student and general reader market. These were also the days in which the asterisks which are used to signal the presence of an explanatory note at the back of the book were individually pasted on to the existing pages before being photographed; occasionally they would drop off, but not often.

As the series grew, and reached a critical mass, the rate of publication slowed and new titles were typeset in a standard typeface to a more or less standard design, though in a series that encompasses everything from Arabic scripture to modern drama, a degree of flexibility is crucial. Once the major titles had been commissioned it was possible to explore areas beyond the core curriculum and to include the kind of non-literary works that hadn’t previously been thought of as classics to sit alongside the novels of Charles Dickens or Charlotte Brontë. Including Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management in the series was a great way of looking at the cookery book as an important document of social and cultural history. It is as revealing of Victorian attitudes in its ambition and assumptions as other contemporary ‘classics’ such as On the Origin of Species and The Woman in White.

As the series grew, and reached a critical mass, the rate of publication slowed and new titles were typeset in a standard typeface to a more or less standard design, though in a series that encompasses everything from Arabic scripture to modern drama, a degree of flexibility is crucial. Once the major titles had been commissioned it was possible to explore areas beyond the core curriculum and to include the kind of non-literary works that hadn’t previously been thought of as classics to sit alongside the novels of Charles Dickens or Charlotte Brontë. Including Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management in the series was a great way of looking at the cookery book as an important document of social and cultural history. It is as revealing of Victorian attitudes in its ambition and assumptions as other contemporary ‘classics’ such as On the Origin of Species and The Woman in White.

Now the series has reached maturity it is possible to revisit editions and bring them up to date with current critical thinking by commissioning new introductions and notes, new translations, and freshly edited texts. I also try to keep an eye out for upcoming anniversaries — beloved by publishers, TV and radio, and journalists the world over — in order to get more attention for a new OWC edition. The proliferation of social media means that it is easier than it ever has been to communicate directly with readers — this blog is a case in point — and to celebrate books whose authors may be long dead but whose content is just as interesting, if not more interesting, than the latest new book. I am constantly amazed by the topical echoes in so many older works, particularly when it comes to corruption (moral and social), misuse of power, money and fraud. I don’t know whether to be reassured that we’ve been there before, or depressed by how little things have changed.

The series has now been through three relaunches since its inception in paperback in 1980, all aimed at reinvigorating the brand and its presence in the marketplace. One of these involved a change in the size of the books in order to conform to the physical dimensions of what has become the most popular paperback format. The series title has evolved from ‘The World’s Classics’ to ‘World’s Classics’ to the current ‘Oxford World’s Classics’, but the most obvious changes concern the cover design. Starting with a boxed illustration and a fixed position for the author and title above it, the cover now has an illustration that fills the front panel. The position and appearance of the type has changed, and the finish has moved from gloss varnish to matt laminate.

Whatever happens to future incarnations of Oxford World’s Classics, one thing is certain: their authors will not be opting for the self-publishing model any time soon.

Judith Luna is Senior Commissioning Editor for Oxford World’s Classics.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Editing the classics, past and present appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Richardsons: the worst of times at Oxford University Press?American Academy of Religion/Society of Biblical Literature 2013 wrap upEtymology gleanings for November 2013

Related StoriesThe Richardsons: the worst of times at Oxford University Press?American Academy of Religion/Society of Biblical Literature 2013 wrap upEtymology gleanings for November 2013

Ten fun facts about Claudio Monteverdi

Italian composer Claudio Monteverdi died 370 years ago today, so what better way to remember him than with the following fun facts:

1. The late American musicologist Leo Schrade called Monteverdi the “creator of modern music”. We’ll call this a bit of an overstatement, but it is true that Monteverdi wrote music that was pivotal in the Western European shift from the Renaissance style to the Baroque style of music.

2. Monteverdi was criticized by fellow composer Giovanni Artusi for the licentious use of dissonance in his madrigals. Monteverdi’s response essentially invalidated Artusi’s criticism: “Oh, you’re talking about the prima pratica, but I’m composing according to the seconda pratica; you might as well compare apples to oranges!” (heavily paraphrased)

3. Speaking of madrigals, Monteverdi wrote nine books full of them, vocal pieces that put the message of the poetry ahead of musical convention (thereby ruffling Artusi’s feathers).

4. Another reason that scholars like Leo Schrade might be inclined to christen Monteverdi the creator of modern music is Monteverdi’s groundbreaking use of music to elicit the strong emotions conveyed by the poems he set. Take for example the extremely evocative second part of his Nymph’s Lament, from the eighth book of madrigals, published in 1638:

Click here to view the embedded video.

5. He was 15 when his first collection of music was published.

6. As I’ve pointed out before, Daniel Day Lewis would be the perfect person to portray him in a movie.

7. He could play the viola da gamba (literally, leg viol) and viola da braccio (arm viol).

8. According to the Grove Music Online article, he dabbled in alchemy. This might be my favorite fun fact.

9. Monteverdi in English? Green mountain.

10. He was one of the first opera composers. I’m partial to his L’Orfeo, published in 1607:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Did I omit your favorite fun fact about Monteverdi? Share it in the comments!

Meghann Wilhoite is an Assistant Editor at Grove Music/Oxford Music Online, music blogger, and organist. Follow her on Twitter at @megwilhoite. Read her previous blog posts on Sibelius, the pipe organ, John Zorn, West Side Story, and other subjects.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: (1) Copy of a portrait of Claudio Monteverdi by Bernardo Strozzi, hanging in the Gallerie dall’Accademia in Venice (1640). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Green Mountain coffee cup via greenmountaincoffee.com.

The post Ten fun facts about Claudio Monteverdi appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPenderecki, then and nowBenjamin Britten, revisitedFrancesca Caccini, the composer

Related StoriesPenderecki, then and nowBenjamin Britten, revisitedFrancesca Caccini, the composer

American Academy of Religion/Society of Biblical Literature 2013 wrap up

We had a great time in Baltimore this past weekend at the 2013 American Academy of Religion/Society of Biblical Literature conference. In addition to searching for the best crab cake in Baltimore, one of our favorite parts was seeing our authors and having them show off their books. See below for a slideshow of some of the fantastic authors (present and future!) that stopped by our booth. And don’t forget you can still access the 20% off conference discount until 31 January 2014!

Peter Gardella

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Peter Gardella, author of American Civil Religion: What Americans Hold Sacred.

la

la Jonathan Yeager

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Jonathan Yeager, author of Early Evangelicalism: A Reader.

la

la Ellen Muehlberger

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Ellen Muehlberger, author of Angels in Late Ancient Christianity.

la

la Mark Leuchter

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Mark Leuchter. author of Samuel and the Shaping of Tradition.

la

la Katie Day

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Katie Day, author of Faith on the Avenue: Religion on a City Street.

la

la Ellen Goldberg

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Ellen Goldberg, co-editor of Gurus of Modern Yoga.

la

la Jay Carney

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Jay Carney, author of Rwanda Before the Genocide: Catholic Politics and Ethnic Discourse in the Late Colonial Era.

la

la Zain Abdullah

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Zain Abdullah, author of Black Mecca: The African Muslims of Harlem.

la

la Janel Bakker

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Janel Kragt Bakker, author of Sister Churches: American Congregations and Their Partners Abroad.

la

la Contract signing

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Nathan Walker and Michael Waggoner signing the contract for the forthcoming handbook on Religion and American Education, with editor Theo Calderara.

la

la Asfar Mohammad

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Afsar Mohammad, author of The Festival of Pirs: Popular Islam and Shared Devotion in South India.

la

la Chad Seales

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Chad Seals, author of The Secular Spectacle: Performing Religion in a Southern Town.

la

la Gary Knoppers

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Gary Knoppers, author of Jews and Samaritans: The Origins and History of Their Early Relations.

la

la Keith Stanglin

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Keith Stanglin, co-author of Jacob Arminius: Theologian of Grace.

la

la Philip Pfatteicher

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Philip Pfatteicher, author of Journey into the Heart of God: Living the Liturgical Year.

la

la Matt Sayers

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Matthew Sayers, author of Feeding the Dead: Ancestor Worship in Ancient India.

la

la Robert Smith

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Robert Smith, author of More Desired than Our Owne Salvation: The Roots of Christian Zionism.

la

la Alyssa Bender is a marketing associate at Oxford University Press, working on the religion Academic/Trade and Reference titles as well as bibles. She can currently be found under a mountain of order forms from the conference.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post American Academy of Religion/Society of Biblical Literature 2013 wrap up appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLooking forward to AAR/SBL 2013Plato’s mistakeNational Bible Week: Learning with Don Kraus, OUP Bible editor

Related StoriesLooking forward to AAR/SBL 2013Plato’s mistakeNational Bible Week: Learning with Don Kraus, OUP Bible editor

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers