Oxford University Press's Blog, page 868

December 8, 2013

Taking stock: Human rights after the end of the Cold War

To mark the date on which the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) in 1948, World Human Rights Day is celebrated each year on 10 December. The first Human Rights Day celebration was held in 1950 following a General Assembly resolution that “[i]nvites all States and interested organizations” to recognize the historical importance of the UDHR as a “distinct forward step in the march of human progress.”

No specific guidelines are given for how this distinct forward step is to be honored; as such, Human Rights Day has evolved over the decades through a wide range of practices and degrees of awareness. More recently, it has become customary for the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) to designate a particular theme for Human Rights Day. For example, the theme for Human Rights Day 2004 was “Human Rights Education”; the theme for Human Rights Day 2006 was “Fighting Poverty: A Matter of Obligation, Not Charity”; and in 2011, the theme was “Celebrate Human Rights!” (the vigorous exclamation point recognizes the role of human rights in revolutions and street protests from the Arab Spring to Occupy Wall Street).

This year, the theme is more sober, measured, and perhaps even a bit bureaucratic: “20 Years: Working For Your Rights.” As a guide to the day’s events, the OHCHR provides a set of promotional videos and statements by international figures and a timeline of important milestones in the twenty years since the World Conference of Human Rights in Vienna, which led to Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action and the establishment of the OHCHR itself.

Click here to view the embedded video.

20 Years of Human Rights – The Road Ahead by United Nations Human Rights

Some of these milestones are specific, demonstrable, and relatively uncontroversial, such as the fact that economic, social, and cultural rights are now considered part of the mainstream corpus of international human rights law and the establishment (in 2002) of the International Criminal Court as the first permanent international court committed to prosecuting those who commit gross violations of human rights. Others are no doubt true, but represent sweeping assertions that fairly beg for closer scrutiny, such as the fact that “[h]uman rights have become central to the global conversation regarding peace, security and development.” And others are so tenuous and prospective as to hardly qualify as a milestone worth of the name, such as the fact that a “growing consensus is emerging that business enterprises have human rights responsibilities.”

Nevertheless, there is no question but that the twenty-five years since the end of the Cold War have been a historical watershed for the broader project of human rights advocacy and enforcement that was forged from the tragedy of the Second World War and its unprecedented levels of military violence, state-sponsored murder, and nationalist imperialism. Despite the fact that a debate is now raging between those who take a long view of the development of the idea of human rights over the decades and even centuries, and those who argue that the project of human rights as we now know it really began as late as the 1970s, there can be little doubt that the end of the Cold War unleashed a flood of both pent-up and new momentum for human rights that continues to wash over a world captivated by the twined promises of human dignity and radical equality.

Beyond the important developments in international human rights law, what was most notable in the transitional years after the end of the Cold War was the emergence of transnational human rights networks and their growing power, particularly in developing countries and those in processes of democratization after periods of dictatorship, military rule, or (as in the case of South Africa) state-sanctioned racism. The key shift that made this possible was the widespread transformation of “development” – understood broadly – from its origins in the technocratic Green Revolution of the 1960s to the more complicated political-moral framework of human rights. It was no longer adequate to facilitate development simply by making the fruits of modern science available to those in most need. Instead, the provisioning of basic human needs now took on a moral imperative. People everywhere had a human right to live as much free from want as from oppression. In this way, the “curious grapevine” that would allow the idea of human rights to “seep in even when governments are not so anxious for it” finally took shape, decades after Eleanor Roosevelt envisioned it.

But if the post-Cold War was a giddy time of possibility for the promotion of human rights, it is worth considering the present status of human rights as the post-Cold War gives way to a world marked by new lines of geopolitical division, new hierarchies of power and influence, and the realization that chronic patterns of socioeconomic inequality continue to set limits on structural change in places where it is most needed. The universal claims of human rights must jostle with other ideologies of political and moral transformation drawn from religion, nationalist politics, culture, doctrines of collective victimhood, and even remnants of Marxist class struggle. And hovering over all is the specter of neoliberal economics and the pervasive logic of costs and benefits, which might or might not encourage the promotion of human rights (with sincere apologies to Kant).

So as the world celebrates Human Rights Day this 10 December, it is right and proper to acknowledge the extraordinary achievements of the last twenty-five years. We now live in an age of human rights. At the same time, this age of human rights is still an uncertain one, with crises over climate change, population growth, and resource scarcity (among others) looming in the near distance. Let us hope a collective appreciation for universal human dignity will guide our attempts to confront them.

Mark Goodale is Associate Professor of Conflict Analysis and Anthropology at George Mason University and Series Editor of Stanford Studies in Human Rights. He is the author or editor of nine books, including Human Rights at the Crossroads, published with Oxford University Press (2012).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Taking stock: Human rights after the end of the Cold War appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSyria’s civil war: historical forces behind regional realitiesBetween ‘warfare’ and ‘lawfare’Requiring local storage of Internet data will not protect privacy

Related StoriesSyria’s civil war: historical forces behind regional realitiesBetween ‘warfare’ and ‘lawfare’Requiring local storage of Internet data will not protect privacy

Innovation in the water industry

This past month has seen much debate about the rising prices of utilities in the UK, focusing on gas and electricity. The price hikes have come not long after reports that companies have made massive increases in profits, for example Scottish Power more than doubled its pre-tax profit to £712m in the year that it raised gas and electricity prices by 7%. This is important, not least because over 3 million people were in fuel poverty in 2011 [see tables here]). David Cameron says that the reason behind rising prices is the introduction of green levies. But when set against this background of fuel poverty means that people are being forced to choose not only between eating and heating, but also between eating and the hope for a habitable climate. I mention all of this to substantiate the claim that the politics of energy often include important considerations of cost and climate change, amongst other issues (for example, energy security) and the balance between the two, but also to highlight the impact of rising utility prices on poverty in the UK.

Questions about rising prices in the water industry often play out according to the same issues of climate change and poverty. But things have been relatively quiet of late for the water companies, which might, in part, be that the average cost of water per household is relatively small compared to gas and electricity, costing £388 compared to £1279. Nonetheless, water poverty is a very significant problem in the UK. In the period 2009-10, nearly a quarter (23.6%) of households were in water poverty (requiring that they spend more than 3% of their income on water).

Prices have consistently risen since privatisation of the water industry in 1989, and have increased faster than overall prices in the UK and faster than average earnings. This is partly because of increasing costs of water provision and treatment, which is caused by a range of factors including climate change (flooding and drought), water practices (consumer and corporate ‘over-use’ and waste) and infrastructural problems (ageing of pipes and leakage in distribution). One key dimension to the increasing price of water is thus the costs of investing in innovations to help to tackle the effects of and reduce our contribution to climate change, and to fix the maze of Victorian pipes that are leaking under out feet.

Prices have consistently risen since privatisation of the water industry in 1989, and have increased faster than overall prices in the UK and faster than average earnings. This is partly because of increasing costs of water provision and treatment, which is caused by a range of factors including climate change (flooding and drought), water practices (consumer and corporate ‘over-use’ and waste) and infrastructural problems (ageing of pipes and leakage in distribution). One key dimension to the increasing price of water is thus the costs of investing in innovations to help to tackle the effects of and reduce our contribution to climate change, and to fix the maze of Victorian pipes that are leaking under out feet.

In a recently published paper, Susan Molyneux-Hodgson (University of Sheffield) and I, presented findings from two years of research on the way in which a group of academic researchers tried to produce a bold technical innovation in the water industry. As part of that work we explored how academic researchers and industry actors worked together and how these groups explained the lack of funding for adventurous innovations. We identified a recurring story about the UK’s impregnable ‘innovation barrier’ for developing cutting-edge technologies, for which there is very limited funding since much of the available money from the UK research councils and from the companies themselves goes instead towards producing incremental improvements in existing techniques.

In our interviews with academics and industrial actors we found that the major narrative explaining the lack of industrial investment was that consumers were ignorant of the costs and ‘true value’ of water and were unwilling to pay the real cost of managing the network and developing novel technologies to help alleviate the problems of climate change and the ageing of the infrastructure. They blamed consumers for their influence on regulators, who seem to be unwilling to let the companies charge more.

Many academic colleagues in natural sciences and engineering bought into the idea that the problem wasn’t so much with monopolies profiting massively from essential water services – whilst the infrastructure aged and climate change got worse – but with consumers, who just couldn’t accept how much it would cost for problems to be fixed. Ultimately, then, the construction of the problem framed its own solution: actors wanted to educate the consumer about the value of water so that they will be willing to pay more for research and innovation, which they believe will help solve leakage and climate change problems.

But we would be rightly sceptical to think that higher prices for water would be used to invest heavily in research to fix problems and lower consumer bills because industrial priorities are not skewed towards investment in infrastructure and technical solutions. For example, across the UK market, investment in research and development varies from a piddling 0.02% of turnover up to the disappointingly tiny drop in ocean at 0.66%. In our interviews with industrial actors we found that they saw no clear incentive to invest in bold technological programmes of innovation if there wasn’t a clear profit to come from it.

Of course, the investment in technologies that might help to protect us against the increasing severity of floods and storms, shortages and droughts, and to help reduce the impact we are having on the global environment are not easily turned into short-term profit making ventures. But clearly, the cost to our water infrastructure, service provision and treatment would be astronomical if we allowed climate change to escalate and the infrastructure to crumble. Technologies are not the only thing we need to help alleviate these problems – we also have to look at consumer and corporate practices. But technological innovation is important. The costs of innovation are not too high, they are essential, but the companies still aren’t willing to pay.

Just like David Cameron wants to focus on green levies in tackling rising fuel bills, trying to educate consumers so that they see the true value of water and thus are willing to pay more is one way of trying to protect profits for shareholders at the expense of often impoverished people in the UK. Regulators of the utilities and our politicians have to be brave and challenge the industries to ensure that profits are not put ahead of the protection of fuel and water poor people in our country or at the expense of our climate and future survival.

Andy Balmer is Simon Research Fellow in the Department of Sociology at the University of Manchester. You can follow him on twitter via @AndyBalmer and read his blog. Susan Molyneux-Hodgson is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Sociological Studies at the University of Sheffield. They are the authors of the paper ‘Synthetic biology, water industry and the performance of an innovation barrier’, published in the journal Science and Public Policy. This post first appeared on Andy Balmer’s own blog, and is reposted with permission.

Science and Public Policy is a leading international journal on public policies for science, technology and innovation. It covers all types of science and technology in both developed and developing countries.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Water coming from a pipe. By klikk, via iStockphoto.

The post Innovation in the water industry appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBetween ‘warfare’ and ‘lawfare’Requiring local storage of Internet data will not protect privacyDo economists ever get it right?

Related StoriesBetween ‘warfare’ and ‘lawfare’Requiring local storage of Internet data will not protect privacyDo economists ever get it right?

December 7, 2013

Gods and mythological creatures in The Iliad in Ancient art

Homer’s The Iliad is filled with references to the gods and other creatures in Greek mythology. The gods regularly interfere with the Trojan War and the fate of various Achaean and Trojan warriors. In the following slideshow, images from Barry B. Powell’s new free verse translation of The Iliad by Homer illustrate the gods’ various appearances and roles throughout the epic poem.

Apollo and Artemis

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 21.2 - Apollo was the aoidos, the “singer,” among the gods. Here young and beardless and holding a lotus staff, he greets his sister Artemis, who carries a bow and is accompanied by a deer, her usual attributes. In classical times the triad Leto, Apollo, and Artemis made up a holy family, although in origin they were unrelated. Athenian red-figure wine-cup by the Brygos painter, c. 470 bc.

Zeus and Ganymede

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 20.2 - Zeus, naked except for a cloak wrapped over his arms, his scepter at his side, seizes the handsome naked boy by the arm and shoulder. Ganymede holds a cock in his left hand, a typical gift in pederastic relationships. He looks down modestly. Zeus’s thunderbolt rests against the frame of the picture to the left. Athenian red-figure wine cup by the Penthesilea Painter, fifth century bc.

Hephaistos Prepares Arms for Achilles

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 18.3 - The smithy-god, bearded and wearing a felt cap, sits in an elaborately draped hall on a platform holding a cloth with which he is polishing

the finished shield. A servant holds it up for inspection. The surface of the back of the shield is so bright that it reflects the figure of Thetis, sitting in a chair with a footstool just as Homer describes. Behind Thetis stands Charis, Hephaistos’ wife. Another servant works on the helmet in the lower left. Between him and Thetis are the breastplate and the shinguards (the surface of the fresco is damaged here). From Pompeii, c. ad 60.

Thetis Consoles Achilles

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 18.1 - Thetis has pulled a cloak over her head in a sign of mourning. Achilles, lying on a couch before which stands a table filled with food, holds his hand to his forehead in a sign of grief for the death of his friend Patroklos. In this representation Thetis has already brought Achilles new armor from Hephaistos, which hangs on the wall. The shield is decorated with the face of a lion. Shinguards hang nearby. To the right of the couch is old man Phoinix and to the left Odysseus—unlike in Homer’s description—and Nereids (?) stand on either side. The names of all figures (except the Nereids) are written out. Black-figure Corinthian wine jug, c. 620 bc.

The Wedding of Zeus and Hera

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 14.1 - The scene is depicted on a metope (a square sculpture on a frieze) from the gigantic temple to Hera (the so-called temple E) at Selinus, at the

southwestern tip of Sicily. Selinus (“parsley”) was the westernmost of the Greek cities in Sicily and destroyed by the Carthaginians in 409 bc. A half-naked Zeus, sitting on a rock, clasps the wrist of Hera. One of her breasts is exposed as Hera removes her head covering in a traditional gesture of sexual submission. c. 540 bc

Poseidon as Kalchas

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 13.2 - In the likness of the prophet, Poseidon holds his trident between the two Ajaxes, Oïlean Ajax and Telamonian Ajax, encouraging them to fight. Telamonian Ajax holds a hoplite shield emblazoned with a ram and behind him to the right is his brother, the bowman Teucer, and another warrior. A fifth warrior stands at the far left. Athenian black-figure wine-cup by Amasis, c. 540 bc.

Poseidon in his Chariot

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 13.1 - The god of the sea rides across the waves in a scene inspired by Homer’s description. He holds his trident in his left hand and points in the direction he wants to go. The chariot is drawn by four horses with dolphin tails. Roman mosaic, ad second century, from a Roman villa in Sousse, Tunisia.

Achilles and Cheiron

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig. 11.3 - In spite of Phoenix’s claims in Book 9 to have educated Achilles, in the usual version referred to by Eurypylos Cheiron the Centaur taught him. Cheiron was the one learned and civilized Centaur in a wild race of savages. Cheiron taught Achilles the arts of a gentleman: to play the lyre and recite poetry, to hunt, and to heal. Here in this Roman fresco from Herculaneum in Italy, Cheiron, bearded and wearing an ivy wreath, holds a plectrum and shows the young Achilles how to play on the lyre. The Romans loved these mythical tales and painted them on their walls as decoration, usually set in a painted frame. This fresco was preserved when Herculaneum was destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in ad 79.

Gorgo

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 11.1 - Shown as the winged Near Eastern “Mistress of Animals,” Gorgo holds a goose in either hand. The scary face is depicted with large eyes, snaky hair (but not here), pig’s tusks, and a lolling tongue. The Gorgon’s stare turns away evil. Here Gorgo is shown with four wings and large, pendulous breasts. Painted red on white ware from Kameiros, Rhodes, c. 600 bc, excavated by Auguste Salzmann and Sir Alfred Biliotti, photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen.

Zeus and his Emblem, the Eagle

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 8.1 - Zeus sits on a throne dressed in an elaborately embroidered cloak. His hair is long and braided and his beard full. Spartan black-figure wine cup, c. 550 BC.

Bellerophon

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 6.1 - Riding the winged horse Pegasos, wearing a traveler’s hat, the hero prepares to stab the Chimaira (“she-goat”). A monster with a snake’s tale, a goat’s head growing from its back, and a lion’s body, the Chimaira is perhaps an invention of the Hittites, who dominated central Anatolia around 1400–1180 bc, and later northern Syria around 900 bc. Pegasos sprang from the blood of the Gorgon when Perseus cut off her head, along with a mysterious Chrysaor, “he of the golden sword” (Apollo has this epithet in Book 5 of the Iliad). From the rim of an Athenian red-figure epinetron (thigh-protector used by a woman when weaving), c. 425–420 bc.

Ares

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 5.2 - On the handle of the famous François Vase, Ares crouches on a stool. His name is written before him (“ARTEMIS” belongs to the figure behind him). He is fully armed as a sixth-century bc hoplite warrior: Shins and chest protected by bronze, he wears a helmet with horse-

hair crest and kneels before his shield. He clings to his single thrusting spear with its point downward. He seems to hold some kind of scepter in his left hand, which he touches to his beard. His genitals are exposed in accordance with conventions of “heroic nudity.” The extraordinary

François Vase, found in Italy, is covered with mythical images, some inspired by the Iliad. Athenian black-figure wine-mixing bowl by Kleitias, c. 570 bc.

Lapiths and Centaurs

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 2.3 - In this relief from the Parthenon in Athens a bearded Centaur seizes the hair of a Lapith youth and prepares to kill him. Homer calls the Centaurs “wild beasts,” and it is not clear that he thought of them as half-horse, half-man, as they were always later portrayed. The Lapith is “heroically nude,” though he does wear a cloak around his shoulders. This is one of the Parthenon metopes, or carved panels, that surrounded the temple high above the line of sight. Marble, c. 430 bc.

Barry B. Powell is Halls-Bascom Professor of Classics Emeritus at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. He is the author of a new free verse translation of The Iliad by Homer. Read our previous posts on The Iliad.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Gods and mythological creatures in The Iliad in Ancient art appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCharacters from The Iliad in ancient artMaps of The IliadEchoes of The Iliad through history

Related StoriesCharacters from The Iliad in ancient artMaps of The IliadEchoes of The Iliad through history

Syria’s civil war: historical forces behind regional realities

Critics of the Obama administration’s Syrian policy have lamented its failure to take into account regional realities. With surprising speed those realities have put the brakes on US intervention. The anti-regime forces in Syria have remained deeply divided — indeed turned violently against each other — and resistant to outside guidance. Government armed forces have retained their integrity and the battlefield initiative. China and Russia have refused to sanction outside meddling. These are the obvious constraints on US activism. But there are broader forces at work that deserve attention.

A good place to start is the Islamist resurgence so important to developments in Turkey, Gaza, southern Lebanon, Egypt, Iran, and Tunisia not to mention Syria. Islamist political movements appearing in all shapes and sizes have discomfited the monarchies of Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain as well as long-established modernizing regimes with a nationalist and secular agenda such as the military-dominated ones in Egypt and Algeria.

The Syrian government dominated by the Ba’ath Party and the Assad family is one of those modernizing regimes up against disruptive Islamist currents. The Ba’ath Party, headed by Hafez al-Assad from the 1970s til his death in 2000, blended nationalism with pan-Arabic sentiments. Its secular, socialist agenda put the party-state at distinct odds with the Syrian branch of the Muslim Brotherhood, which was brutally crushed in a confrontation in 1982. As the successor to his father, Bashar al-Assad talked at first of reform but since 2011 has fought for survival against a loosely-organized, armed opposition including prominently jihadi groups. Civil war has reopened the divisive question not only of Islam’s role within Syrian political and cultural life but also of whose version of Islam should prevail. In Syria as elsewhere the answers vary depending on whether you ask in the city or the countryside or address Sunni, Shia, Christian, Alawites, Druze, or Kurd.

The questions posed by a reinvigorated Islam fit neatly under the heading of nationalist contestation. Edward Said’s caution against thinking about the region in terms of “vast abstractions” that yield “little self knowledge or informed analysis” remains particularly pertinent. Civilization and identity, he contended in The Nation in October 2001), were not “shut-down, sealed-off entities” but rather fields of on-going, multifaceted ideological conflict. Were American leaders to embrace this general truth about the modern world, they might have a better chance of reaching an “informed analysis” of Syria in particular. Outsiders, it should be clear, can try to shape nationalist debates, but they are not likely to have much of a clue about the terms of the debate and even less legitimacy.

Much like nationalism, empire casts a long shadow over the Syrian crisis and the region. The United States, Britain, and France are associated with colonialism, military intervention, and cultural imperialism. They win no points for having shored up dictators, favored Israel, and cultivated a distaste for political Islam. The United States is in a particularly compromised position. While Obama insists (as he did in his Cairo speech in 2009) that the United States was not “the crude stereotype of a self-interested empire,” the historical record argues strongly against him. From Egypt and Palestine to Iraq, Iran, and Afghanistan, British overlords yielded after 1945 to the primacy of a rising power with greater financial resources and military muscle. The Americans not only followed in the British footsteps but also generally continued the strategy of indirect rule reinforced by an occasional coup, a pacification campaign now and then, and an occasional dose of gunboat diplomacy. This approach kept down the costs of empire (especially important for a weakened Britain) but it also avoided the more blatantly imperial direct rule (so distinctly at odds with the American self-image).

Syria is a variant in an old story of outside interference remembered, resented, and resisted. Assad was making more than a casual observation when in an interview this year he associated empire with a “divide and conquer” strategy. “By division, I do not mean [just] redrawing national borders but rather fragmentation of identity, which is far more dangerous.” This preoccupation with the legacy of empire — economic and political as well as cultural — is region-wide and to judge from a July 2013 Pew survey of public opinion makes US policy distinctly suspect. A substantial proportion of respondents flatly declared the United States “an enemy” rather than “a partner.” This was the view of roughly a half to three quarters in Turkey, Lebanon, the Palestinian territory, and Pakistan and from a quarter to a third in Egypt and Jordan. In all these cases the percentage of “enemy” responses exceeded the “partner” responses.

Finally, Syria suggests the importance of bringing globalization into our mix of big, defining historical forces. The Syrian conflict has played out within a complex of transnational networks carrying most notably people (refugees and fighters), NGO’s offering humanitarian assistance to several million driven from Syria by the fighting, and digital information (most evident in the propaganda wars of the combatants). Perhaps most striking of all (and surprising to Washington) has been the capacity of genuinely international norms and institutions to make a difference. The international agreement on chemical weapons and the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons have effectively defused a crisis created by Obama’s careless “red line” declaration and demonstrated what American leaders seem to forget: the efficacy of international law and diplomacy, and the need to take seriously other powers with divergent views (not least Russia and the other permanent members of the UN Security Council) in resolving knotty problems of the sort the Syrian civil war poses.

The absence of historical perspective in the pronouncements of the Obama administration is striking but nothing new in Washington. The denizens of the foreign policy establishment as well as the media tend to lapse into the “vast abstractions” that Said decried. The prevailing version of history is dated and superficial and applied in the main to shoring up predetermined policy, offering inspirational insights on political leadership, or affirming comforting notions of national mission. Reflecting on the particular problem of Syria highlights a general and dangerous blind spot in US policy. A global power with a diminished sense of the past has few resources to illuminate the future.

Michael Hunt is the Everett H. Emerson Professor of History Emeritus at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He is the author of The World Transformed, 1945 to the Present. A leading specialist on international history, Hunt is the author of several prize-winning books, including The Making of a Special Relationship: The United States and China to 1914. His long-term concern with US foreign relations is reflected in several broad interpretive, historiographical, and methodological works, notably Ideology and U.S. Foreign Policy and Crises in U.S. Foreign Policy: An International History Reader.

The Oxford Atlas Place of the Year 2013 is Syria. The Oxford Atlas Place of the Year is a location — from street corners to planets — around the globe (and beyond) which has attracted a great deal of interest during the year to date and judged to reflect the important discoveries, conflicts, challenges, and successes of that particular year. Learn more about Place of the Year on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Palmyra, Syria – March, 25th 2011: A demonstration moves along the main street in the town of Palmyra in the middle of Syria. Young people stand on the roof of a moving car holding the Syrian flag. The Syrian uprising started in March 2011. © Sporthos via iStockphoto.

The post Syria’s civil war: historical forces behind regional realities appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAncient Syria: trouble-prone and politically volatileBetween ‘warfare’ and ‘lawfare’Seven facts of Syria’s displacement crisis

Related StoriesAncient Syria: trouble-prone and politically volatileBetween ‘warfare’ and ‘lawfare’Seven facts of Syria’s displacement crisis

Coherence in photosynthesis

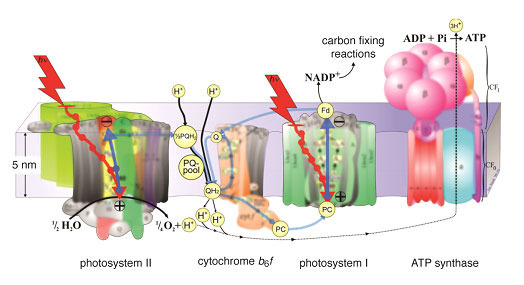

Photosynthesis is responsible for life on our planet, from supplying the oxygen we breathe to the food that we eat. The process of photosynthesis is complex, involving many protein complexes and enzymes that work together in a concerted effort to convert solar energy to chemical bonds. Oxygenic photosynthesis is catalyzed via two light drive electron transfer reactions. The first step in this process is the absorption of a photon by light-harvesting complexes which then funnel this excitation energy to the reaction center (Figure 1). Given the complexity of photosynthesis, it can be hard to imagine the role that quantum mechanics, i.e. coherence, could play in this process.

Figure 1. The photosynthetic apparatus associated with the light dependent reactions of photosynthesis is shown. The energy transfer pathways involved in photosynthesis are depicted as red arrows, electron transfer pathways as blue arrows, and the proton transfer pathways as black arrows. Image courtesy of Jon Nield adapted by Joris Snellenburg.

Recent experiments employing ultrafast laser pulses have investigated light-harvesting complexes to gain insight into the light initiated processes occurring on the femtosecond (1×10-15 s) timescale. These experiments have found that concepts from quantum mechanics are required to sufficiently describe the observations.

In our research, we explored how the experimental technique of two dimensional electronic spectroscopy gives a rather direct measurement of these quantum mechanical effects, i.e. coherences. In these measurements a series of ultrafast laser pulses excite light-absorbing pigment molecules embedded in the protein matrix of a light-harvesting complex (Figure 2). Then the laser pulses record how this absorbed energy flows among the pigment molecules, allowing for scientists to directly track pathways of energy flow. Results of these measurements indicate that upon excitation, individual light-harvesting molecules act collectively to absorb and transfer energy, as opposed to the light-harvesting molecules acting individually. To describe this cooperative action requires the incorporation of concepts from quantum mechanics.

Figure 2. Structural models of the main light harvesting complexes found in plants (a,c) LHCII and purple bacteria (b,d) LH2. Source: Bioscience.

This quantum mechanical aspect of the shared excitation leads to wave-like properties that can interfere when troughs and peaks of different waves overlap. In this sense, one could imagine that this interference could act to provide efficient passage through the array of pigment molecules. However, there is now ample evidence which suggests that this is not necessarily the case and the role coherence plays in photosynthesis is still elusive.

For further research we may ask how coherence in light-harvesting complexes couples to incoherent phenomena, perhaps facilitating some other aspect of the cell. A deeper understanding of these processes could help scientists to incorporate these concepts into artificial photosynthetic devices and bio-inspired solar cells.

Jessica M. Anna, Gregory D. Scholes, and Rienk van Grondelle are the authors of “A Little Coherence in Photosynthetic Light Harvesting” (available to read for free for a limited time) in BioScience. Jessica M. Anna is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Toronto. Gregory D. Scholes is the D.J. LeRoy Distinguished Professor of Chemistry at the University of Toronto. Rienk van Grondelle is a Professor of Biophysics at Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam.

Bioscience publishes timely and authoritative overviews of current research in biology, accompanied by essays and discussion sections on education, public policy, history, and the conceptual underpinnings of the biological sciences.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Coherence in photosynthesis appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOral histories of Chicago youth violenceBetween ‘warfare’ and ‘lawfare’Requiring local storage of Internet data will not protect privacy

Related StoriesOral histories of Chicago youth violenceBetween ‘warfare’ and ‘lawfare’Requiring local storage of Internet data will not protect privacy

December 6, 2013

Oral histories of Chicago youth violence

I’m not sure my introduction will do justice to this week’s interview between OHR managing editor Troy Reeves and DePaul University Professor Miles Harvey. An English professor and bestselling author trained in journalism, Harvey is the editor of How Long Will I Cry: Voices of Youth Violence (Big Shoulder Books , 2013), a compilation of oral histories collected by students in Harvey’s class “Creative Writing and Social Engagement” from young and old Chicago residents affected by youth violence. In addition to relating the powerful collection’s interdisciplinary origins, Harvey discusses oral history as a narrative form and the value of collaborative story telling.

How Long Will I Cry also highlights a new type of publishing. The collection is being printed and distributed by Big Shoulders Books, a small press operating out of DePaul University. BSB aims to publish one book a year that engages with and provides a platform to Chicagoans often marginalized by mainstream media. You can request an exam copy or watch a trailer for How Long Will I Cry:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Finally, here is an excerpt from the collection. This story comes from LaToya Winters, who grew up on the West Side of Chicago. She currently studies sociology and Family and Child Studies at Northern Illinois University.

My grandmother, Carrie Winters, was born and raised in Mississippi. After her parents passed on, she moved to Chicago. She wanted to find work, and she wanted a better life for her children. She worked all these odd jobs just to make a way for her kids—two to three jobs at a time. She worked at Campbell’s Soup forever, and that passed down to my aunt working there. My grandmother bought her house in maybe the ’40s and lived there until she died in 2006.

I always smelled a sense of soulful in her. I could smell this perfume that she’d always wear, especially when she went out or went to church. When I say she was churchgoing, I mean churchgoing. She was always cooking, everything from the big dinners to macaroni to the chitlins. She had a kind of curl to her hair, because she always wore rollers when she went to the beauty salon. She was a hard-working, independent woman; I see that in her from as early as I can remember. It is still deeply rooted in her grandkids today. Oh my God, we are pieces of my grandmother.

A lot of my grandmother’s kids strayed off—a majority of her kids, honestly. Some of them were alcoholics; some were drug addicts like my mother, Raquel. My grandmother raised me. My mother had nine kids, and my grandmother had custody of all of them, plus maybe 10 to 15 of my cousins. My uncles’ kids, then my aunts’ kids—my grandmother raised all of us. We had a two-flat building with a basement, a first floor and a second floor. There was always room.

My grandmother reached out and took care of kids that weren’t hers. At Thanksgiving dinner, if we had a friend who didn’t have anywhere to go, my grandma had enough to go around. She had her table set for everybody. If me and three cousins had to sleep in the same bed, we always had somewhere to sleep. My grandmother adopted all of us, because everyone had their different problems, and she refused to let us be separated. She never closed the door on anybody, including her own kids who didn’t, you know, fulfill their parent responsibilities. I never even heard my grandmother talk down about anybody, no matter what.

Gangs always existed in my neighborhood. The majority of the guys in my family are affiliated with the Gangster Disciples; so are the majority of people in my neighborhood, actually. I never understood what it was about gangs, but then, as I grew older, I learned more. I’ve had these sociology classes about it, and I see the way gangs have destroyed people. I’ve talked to people like my uncles and cousins and brothers who say, “I got put into the gang when I was younger,” and, “If I could have gotten out, I would have.” But some of them wouldn’t have. Like I always say, “You live by it, you die by it.”….

You can read the rest of LaToya’s story, as well as others, at Medium.com.

Professor Miles Harvey is the author of the award-winning novels Painter in a Savage Land: The Strange Saga of the First European Artist in North America (Random House, 2008) and The Island of Lost Maps: A True Story of Cartographic Crime (Random House, 2001). More recently, Harvey worked with a group of DePaul students to collect stories about youth violence across Chicago. This endeavor led to a play staged at Steppenwolf in Spring 2013, and the oral history collection How Long Will I Cry: Voices of Youth Violence (Big Shoulder Books, 2013). He currently serves as Assistant Professor in English at DePaul University.

The Oral History Review, published by the Oral History Association, is the U.S. journal of record for the theory and practice of oral history. Its primary mission is to explore the nature and significance of oral history and advance understanding of the field among scholars, educators, practitioners, and the general public. Follow them on Twitter at @oralhistreview, like them on Facebook, add them to your circles on Google Plus, follow them on Tumblr, listen to them on Soundcloud, or follow the latest OUPblog posts via email or RSS to preview, learn, connect, discover, and study oral history.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Oral histories of Chicago youth violence appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe usable past: an interview with Robert P. Wetteman Jr.CSI: Oral HistoryOral history goes transnational

Related StoriesThe usable past: an interview with Robert P. Wetteman Jr.CSI: Oral HistoryOral history goes transnational

Mandela, icon

The name Nelson Mandela and the word icon are once again on people’s lips, as if spoken in the same breath. With the sad news last night that the nonagenarian former South African President Nelson Mandela has died, his name is again in the air, and with his name the obligatory tag. Mandela the icon of freedom, of liberation, of justice; the hero of the world, to quote Barack Obama; Mandela the symbol of non-racialism, people gravely say, thinking, if they are of a certain age, probably over thirty-five or so, of his long walk to freedom, or the Special AKA song-refrain ‘free-free-free Nelson Mandela’; if they are younger, of a moral giant who fought racism some time last century. Cutting straight to the point many simply use the word icon tout court when speaking of him. Ah yes, Nelson Mandela, they say, what an icon. That incredible man, that icon.

Mandela the icon. The name Mandela as a synonym for icons. It is an interesting locution, one that of course reflects our time’s obsession with celebrity, with individuals who in some sense embody the fame or glamour attached to their name. But it is an interesting locution, too, in respect of the man and the leader Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela himself, of his long political career and world-renowned reputation. There are perhaps few other political leaders who in their life-time have attained the uncontroversial status or the easy recognisability of the media icon as he did. Though MK Gandhi comes close, it is difficult to think of Gandhi hailed as ‘President of the World’ as Mandela was in 2007 on the unveiling of his statue in Westminster Square. At the time Mandela stepped down from power in 1999, the talk at least in his country South Africa was that the international currency of his face as icon was surpassed only by Coca-Cola’s red logo and the golden arches of McDonalds. He was, in a sense, an icon of icons, a hyper-symbol, as is captured in the huge variety of merchandise ranging from fridge-magnets to aprons, from dolls to mugs, bearing the image of his smiling face which is available in tourist shops not only in South Africa, but across the African continent.

Yet an icon, especially one so prevalent, is by and large a static and 2-D entity. ‘Mandela the icon’ tells us little to nothing of Nelson Mandela’s remarkable story: his complicated political legacy, his radiant magic as a leader, and his strength of character in surviving 27.5 years of incarceration. It tells us nothing of his remarkable success in bridging seemingly unbridgeable racial divides in South Africa by forging bonds of reconciliation that many at the time, and since, found next to miraculous. Icon is an end-product word that gives little sense of the painstaking process of building a mass movement and at the same time forging a new national community that was Nelson Mandela’s great achievement.

Both as a young politician and activist in the 1950s, and then later, as an elder statesman and South Africa’s first democratic president, Mandela worked indefatigably to channel his innate qualities of charisma and self-discipline into becoming a source of inspiration and hope for his people, the ground for the making of a non-racial democratic nation. Many of his colleagues and comrades have spoken of his ability to lead from the front and yet at the same time charm his followers with his radiance of personality to think that they were in fact moving forwards as a group. This compelling magnetism was such that those close to him coined the term Madiba magic to describe it—Madiba being his clan honorific. It is a quality that illuminates the Mandela icon from within like a lamp.

‘Mandela the icon’ also does not capture the complicated nature of the man and the interesting contradictions that cut across and disturb our sense of his political legacy. Mandela, both his fans and detractors acknowledge, was a leader who could be all things to all people: an African nationalist when among African nationalists, a socialist in his relations with his South African Communist Party colleagues, even a South African patriot when in dialogue with patriotic Afrikaners. A consummate performer, he was always an extremely able manipulator of his own image, yet this malleability could send out mixed messages. He spoke the language of democracy, but was often authoritarian in his manner. He signed up to the 1956 ANC Freedom Charter with its commitment to nationalization, but on assuming power he made serious and, some critics might say, fatal deals with free-market capitalism in order to secure South Africa’s post-apartheid economic future. In the early 1960s he supported the move to armed struggle in order to bring down the walls of apartheid, yet now it is as a warrior for peace and reconciliation that he is best-known.

Who stands behind the icon Nelson Mandela? What is it that we see when we look into its smiling eyes? Above all, taking into account his interesting, very human complexities, it is for his humanity and what I would like to call his historic warmth that Nelson Mandela will be remembered. He forged reciprocity where none had hoped to find it when he observed that friend and foe by and large shared the same aims, fears and desires. He took the hand of his gaoler and the hand of his comrade and joined them together by pointing out that at the end of the day it was the same piece of earth that they were fighting for. He approached others not as members of a certain race or group but as human beings. Where previously there had been division and hate, he forged interaction. He deserves to be remembered therefore not simply as an icon, but as a towering figure of ordinary humanness and immense courage. He is, as the poet Jeremy Cronin puts it, an undoubted symbol of freedom but one with hands that were ‘pudgy’ and humanly reassuring. His spirit will live on because of the extraordinary human being he was and the superhuman sacrifices he made.

Elleke Boehmer is Professor of World Literature in English at the University of Oxford and author of Nelson Mandela: A Very Short Introduction.

Image credit: Johannesburg, South Africa – February 13, 1990 : Former South African President Nelson Mandela, shows the freedom salute after his release from prison. © ruvanboshoff via iStockphoto.

The post Mandela, icon appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIn memoriam: Nelson MandelaSeven facts of Syria’s displacement crisisPutting Syria in its place

Related StoriesIn memoriam: Nelson MandelaSeven facts of Syria’s displacement crisisPutting Syria in its place

Between ‘warfare’ and ‘lawfare’

The Syria crisis has challenged the boundaries of international law. The concept of the ‘red line’ was used to justify military intervention in response to the use of chemical weapons. This phenomenon reflects a trend to use law as a strategic asset or instrument of warfare (‘lawfare’). In the Syrian context, terms and rationales of criminal law (e.g. retribution, deterrence) entered the justification for the use of force. Intervention was framed in a way that suggested that is acceptable to ‘punish’ the Assad regime through use of force. I argue that this practice reveals certain deeper dilemmas in international law that merit critical reflection: (i) the role of semantics, (ii) the idea of ‘punishment’ through the use of force, and (iii) ‘humanitarian labelling’.

Syria and the role of semantics

In international affairs, law is typically presented as neutral and objective framework of discourse. The debate on intervention challenges this assumption. Legal terms and concepts were used as strategic tools to portray certain narratives about the conflict and to make use of force more acceptable. Classical philosophy uses the distinction between logos (reasoned discourse), pathos (appeal to sympathies), and ethos (expertise and responsible use of knowledge). The Syria crisis shows that is important to understand why and how vocabulary and imagery are used to justify certain choices.

Like in previous interventions (e.g. Kosovo, Iraq) specific techniques were used to ‘frame’ the case for action and to make it more persuasive in legal discourse. Action was contrasted with inaction, by way of binary (‘either/or’) dichotomy in which intervention was presented as a lesser of two evils (G20 statement). Pro-intervention speech used heroic narratives to shift attention from violence of intervener to victims. A compelling example is President Obama’s statement at the General Assembly (‘Should we really accept the notion that the world is powerless in the face of a Rwanda or Srebrenica?’) or Harold Koh’s comparison of interveners to ‘ambulance drivers who run red lights in extremis’. In legal justifications, emphasis was placed on a logic of exceptionalism (UK Legal Memorandum, White House statements). The most compelling example is the image of the ‘red line’ itself. It was invoked to claim the use of ‘chemical weapons’ warrants a repressive response, including a legitimate threat of or recourse to the use of force.

Following the return to collective security, specific legal opinions were voiced by former legal advisors through informal channels, such as blogs, to preserve authority for intervention (e.g., Daniel Bethlehem, Harold Koh).

These dynamics illustrate a trend to use legal terms as a strategy in intervention which deserves critical attention in ‘reading’ international law.

Intervention and ‘punitive’ considerations

A second dilemma of the Syrian crisis is the recourse to ‘punitive’ motives in the rhetoric of justification. Use of force was considered as an instrument to remove the threat of chemical weapons and to achieve retribution. This claim sits uneasily with contemporary international law. The case for intervention conflated two layers of legal reasoning that have been separated for good reasons in the past decade: (i) responsibility of a state for the breach of a fundamental international norm (i.e. the ban of the use of chemical weapons in armed conflict), and (ii) accountability for international crimes (individual criminal responsibility).

The idea that another state might be ‘punished’ for unlawful conduct has has lost support in the development of modern international law. ‘Punitive’ rationales have become suspect in UN collective security action (e.g. ‘targeted sanctions’). International law is hostile towards armed reprisals in peacetime and ‘punitive reprisals’ in armed conflict. International criminal law contains a prohibition of collective punishment to avoid an indiscriminate effect. It remains highly controversial to what extent the right to self-defence might entail dimensions of ‘punishment’. Contemporary just war theorists (e.g. David Rodin) claim that ‘punitive war’ is morally wrong because there is no-one who has the ‘superior’ authority to punish.

Legal discourse on Syria re-opened this distinction. I would argue that this is a dangerous development. Use of force cannot and should not serve as a short-cut to international justice or as a means of punishment in the ‘criminal sense’.

Syria and ‘humanitarian’ labels

Thirdly, recourse to ‘punitive’ justifications was coupled with the use of specific ‘humanitarian’ labels. The concepts of ‘humanitarian intervention’ and ‘protection of civilians’ were invoked as justifications for action. Their use remains contestable.

Syria differs from other cases of ‘humanitarian intervention’. Given the conflicting views over the goals and roles of both parties in the conflict, there was no clear strategy what to stop through ‘intervention’. Intervention was not directly aimed at ending atrocities and armed conflict as such. It was geared at best at shifting the military balance between the Assad regime and opposition forces. It was framed as a response to an incident in a crisis, i.e. the use of chemical weapons. A sustained international presence in and after conflict was ruled out. This reasoning differs from the necessity arguments and moral dilemmas that underpinned other interventions (e.g. Kosovo).

Similar criticisms apply in relation to the use of the label of ‘protection of civilians’ invoked in the UK Legal Memorandum. The concept might justify the establishment of safe-zones or demarcation lines in conflict. But it provides limited scope for retaliatory action against combatants in civil war. It is, in particular, ill-equipped to accommodate goals of ‘punishment’ and regime accountability. Logically, regime accountability might be a consequence or effect of protection. The discourse on intervention in Syria turned this logic on its head. It used protection as a means to achieve accountability through military force. This approach conflates fundamentals of the law of armed force. It relies on core principles under international humanitarian law (jus in bello) to extend claims relating to the use of force (jus ad bellum). This weakens the ban of war as instrument of punishment and enforcement of legal claims which has gained ground in the second half of the 20th century.

The use of armed force was only averted through last-minute diplomacy on Syrian disarmament in late September 2013. The return to UN collective security structures was partly driven by fears about the spread of chemical weapons to non-state actors. This shared concern led to agreement on the disarmament regime under Security Council Resolution 2118.

Logos, pathos, and ethos

What conclusions can be drawn from this? I would argue that the Syrian crisis has at least three key implications for the treatment of intervention under international law.

First of all, there is a need for greater vigilance towards the ‘import’ and ‘expert’ of specific labels in different fields of international law. In past decades, notions and concepts of criminal law have penetrated fields, such as human rights law and international humanitarian law. This process has generally been celebrated as a move towards greater enforcement of legal norms. But it has downsides. Syria shows how the use of semantics may blur lines and conflate categories of law.

Secondly, the strategic use of legal notions and vocabulary as means of intervention makes it necessary to contemplate the role of different actors and constituencies in discourse, including checks and balances. In many contexts, discourse on intervention is dominated by State executive power. There is a need to rethink discourse on intervention through the lens of democratic legitimacy. The role of domestic parliaments in the Syrian crisis supports the idea that ‘humanitarian interventions’ should enjoy a sufficient degree of transparency and legitimacy at the domestic level of the intervening states before such action can be ‘safely’ undertaken.

Thirdly, it is vital for international lawyers to understand how semantics are used and how underlying narratives can be deciphered. Syria shows that there are different approaches towards arguing about intervention. There is a ‘formal’ approach which is geared at constraining options for unilateral intervention. It is grounded in formal legal texts and typically deployed in discourse within collective deliberative fora and international legal institutions. It contrasts with a more ‘flexible ’approach, which is more open towards systemic change and adaptation of the law through less formal processes (e.g. incremental practice) or criteria (e.g. ‘factors’ justifying the use of force). Both of them are inherent in international law. The first approach contributes to the maintenance of the formal ideal (i.e. the preservation of the ‘imperfect, yet resilient, security system’ of the UN Charter). The second one points towards transformation and adjustment of law to practice. They are invoked with logos and pathos. The challenge is how to strengthen ethos in the discourse.

Carsten Stahn is Professor of International Criminal Law and Global Justice at Leiden University and Programme Director of the Grotius Centre for International Legal Studies (The Hague). He directs research projects on ‘Jus Post Bellum’ (see Jus Post Bellum: Mapping the Normative Foundations) and ‘Post-Conflict Justice and Local Ownership’, funded by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO). He is Editor-in-Chief of the Leiden Journal of International Law, Executive Editor of the Criminal Law Forum and Correspondent of the Netherlands International Law Review. He is the author of “Syria and the Semantics of Intervention, Aggression and Punishment” (available to read for free for a limited time) in the Journal of International Criminal Justice.

The Journal of International Criminal Justice aims to promote a profound collective reflection on the new problems facing international law. Established by a group of distinguished criminal lawyers and international lawyers, the journal addresses the major problems of justice from the angle of law, jurisprudence, criminology, penal philosophy, and the history of international judicial institutions.

The Oxford Atlas Place of the Year 2013 is Syria. The Oxford Atlas Place of the Year is a location — from street corners to planets — around the globe (and beyond) which has attracted a great deal of interest during the year to date and judged to reflect the important discoveries, conflicts, challenges, and successes of that particular year. Learn more about Place of the Year on the OUPblog.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in international law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide. For the latest news, commentary, and insights follow the International Law team on Twitter @OUPIntLaw.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Palmyra, Syria – March, 25th 2011: A demonstration moves along the main street in the town of Palmyra in the middle of Syria. Young people stand on the roof of a moving car holding the Syrian flag. The Syrian uprising started in March 2011. © Sporthos via iStockphoto.

The post Between ‘warfare’ and ‘lawfare’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSeven facts of Syria’s displacement crisisAncient Syria: trouble-prone and politically volatileThe Oxford Atlas Place of the Year 2013 is…

Related StoriesSeven facts of Syria’s displacement crisisAncient Syria: trouble-prone and politically volatileThe Oxford Atlas Place of the Year 2013 is…

Requiring local storage of Internet data will not protect privacy

Widespread Internet surveillance by governments, whether carried out directly or by accessing private-sector databases, is a major threat to the data protection and privacy rights of individuals. It seems that in some countries (such as the United States), the national security state is out of control. This has led to proposals to require that the Internet data of individuals be stored within their own national borders, or even to re-engineer the technical infrastructure of the Internet to store data locally.

As I warned, requiring local data storage would undermine, rather than strengthen, fundamental rights by making it easier for intelligence services to access data locally and then share them with other countries. For example, it seems that the French intelligence services conduct widespread Internet surveillance in France and share the data they collect with the United States, so it is not clear what the privacy benefit would be of requiring data to be stored in France. Computer science experts have also stated that requiring data to be stored in country would be largely ineffective in protecting against foreign surveillance.

Proposals to limit transborder data flows under the proposed EU General Data Protection Regulation would have no effect on data processing by the intelligence services, as that instrument does not even apply to data processed for ‘national security’ purposes (under Article 4 of the Treaty on European Union, national security remains the ‘sole responsibility’ of the Member States).

Nor does human rights law necessarily require local data storage. The UN’s International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) protects both privacy (Article 17), and freedom of expression ‘regardless of frontiers’ (Article 19), which rights must be balanced based on the principle of proportionality. Requiring local data storage only strengthens the authority of national intelligence services and their ability to collect data locally, and limits the possibility to communicate across borders, without having any specific benefit for privacy.

To be sure, access to Internet data by the United States and other governments will likely lead to a greater demand by citizens, businesses, and governments for data to be stored within their own borders (particularly data that are especially sensitive, or those concerning critical infrastructure). But no one should be under any illusions that legal requirements to store data locally will prevent intelligence services from gaining access to them.

So, what can and should be done to protect against surveillance of Internet data by the intelligence services?

With regard to excesses by the US intelligence services, the most effective action would be legal reform in the United States itself, and a debate is already underway in this regard. However, as a symposium issue of International Data Privacy Law in 2012 demonstrated, systematic governmental access to online data is a global problem that is not limited to one country. Calls for the UN Human Rights Commission to draft a protocol to the ICCPR specifically covering online data protection rights are praiseworthy, since we need stronger legal protections for privacy at the international level. However, such efforts are unlikely to reach fruition anytime soon.

Any moves by the European Union to protect against data access by foreign intelligence services can only be effective if the EU Member States reach a common understanding of what constitutes ‘national security’. Having 28 different national interpretations of this concept facilitates data collection by national intelligence services and the sharing of data with third countries. Data processing for national security purposes should also be brought within the EU’s data protection reform proposals (though legal issues concerning EU competence would have to be clarified in this regard).

Bellicose rhetoric calling for a ‘legal Maginot Line’ in cyberspace to protect EU data against foreign surveillance should be firmly rejected. There is no legal mechanism that can shut off data transfers from the European Union to other countries without also disconnecting the EU from the Internet, with all the catastrophic economic and social consequences that would entail. Attempting to wall off countries or regions in the Internet would be a disproportionate interference with the right of transborder communication, and would be legally unenforceable. The real Maginot Line was a failure, and a virtual one would be as well.

We should demand that personal data be protected from omnipresent law enforcement surveillance, and that legal protections be implemented to shield data as much as legally possible. However, this should cover both domestic and foreign surveillance, and should allow the Internet to function as a global, open network. If we value the freedom to communicate globally, we will have both to strengthen global standards of data protection, and reject calls for the construction of virtual walls.

Dr. Christopher Kuner is editor-in-chief of the journal International Data Privacy Law. He is author of European Data Protection Law: Corporate Compliance and Regulation and Transborder Data Flow Regulation and Data Privacy Law. Dr. Kuner is Senior Of Counsel at , and an Honorary Fellow of the Centre for European Legal Studies, University of Cambridge.

Combining thoughtful, high level analysis with a practical approach, International Data Privacy Law has a global focus on all aspects of privacy and data protection, including data processing at a company level, international data transfers, civil liberties issues (e.g., government surveillance), technology issues relating to privacy, international security breaches, and conflicts between US privacy rules and European data protection law.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Internet Background with Code and Technology World. © kentoh via iStockphoto.

The post Requiring local storage of Internet data will not protect privacy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDo economists ever get it right?Syria and the social netwar 2011-2013Enforced disappearance: time to open up the exclusive club?

Related StoriesDo economists ever get it right?Syria and the social netwar 2011-2013Enforced disappearance: time to open up the exclusive club?

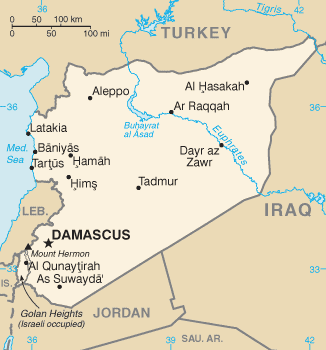

Putting Syria in its place

By Klaus Dodds

Where exactly is Syria, and how is Syria represented as a place? The first part of the question might appear to be fairly straight forward. Syria is an independent state in Western Asia and borders Lebanon, Turkey, Jordan and Israel. It occupies an area of approximately 70, 000 square miles, which is similar in size to the state of North Dakota. Before the civil war (March 2011 onwards), the population was estimated to be around 23 million, but millions of people have been displaced by the crisis. We must also add into the equation that around 18 million other people, living in North America, Latin America, Europe and Australia are of Syrian descent. Famous people of Syrian descent include the late Steve Jobs of Apple fame and the actress Teri Hatcher. So where does Syria begin and end when we factor in the Syrian diaspora?

How has Syria been understood as place?

During the ongoing and bloody civil war, we have arguably been bombarded with news stories and images of a country that has rarely enjoyed such prominence. Fundamentally, and over a period of 18 months, Syria transformed from a minor element of Middle Eastern geopolitics (compared to Israel, Iran and Palestine in the past) and Arab Spring transformation (compared to Egypt, Tunisia and Libya) to a place of mass concern. But making sense of the Syrian civil war or uprising remains a deeply contested affair as rival groups inside and outside Syria struggle to frame Syria in political and geographical terms. My contention is that Syria can be understood in six fundamental, and at times, competing ways.

1. Syria represented as a place of humanitarian disaster

The ongoing conflict in Syria has uprooted communities and forced millions to flee across international borders, or seek safety within the country as internally displaced people. The United Nations believe that around 40% of the population requires humanitarian assistance and some six million people are thought to be displaced in some fashion. As a space of unfolding and continued humanitarian disaster, Syria becomes increasingly demanding of our attention; the focus of concern and assistance in the wake of concern that the state is no longer able to function in a way that is conducive to the security of its citizens. As a humanitarian disaster, it also heightened the likelihood that Syria’s territorial sovereignty will need to be violated in order for the UN and others to offer protection and support for vulnerable citizens, many of whom are women, children and the elderly.

2. Syria framed as a space of extremism

The civil war is believed to have unleashed new forces of extremism and sectarianism. Syria in the process becomes a more complex place. Maps circulate purporting to show the ethnic composition of the country, and like maps of the former Yugoslavia and Iraq, help to sustain arguments warning of long standing animosities and dangers facing those who intervene. It becomes an opportunity for others to note that Syria is an ‘invented country’; a product of the First World War and the French mandate. As if to suggest, as a consequence, what do you expect? Extremism flourishes in such complexity where the ruling elite are a minority sect of Islam (Alawites).

3. Syria represented as a place of opportunity

The ‘big powers’ and ‘rising powers’ that are using Syria opportunistically play out their own agenda so that less attention is given to Syria as a complex inhabited place. Syria becomes both a stage and a conduit for diplomatic and military performances, and a space for flows of arms and other forms of support to particular factions. Some of the players, such as Qatar, are relatively new to this kind of ‘big power geopolitics,’ but apparently driven by a desire to be seen as a more active geopolitical agent in the region. Others, such as Russia, have had a long standing relationship with the Syrian regime and consider the country to be strategically significant, close to the Mediterranean, and close to oil and gas fields of the Middle East. A view that, it is argued, the US shares as well.

CIA map of Syria

4. Syria framed as a place ruled by conspiracy

The fourth version of Syria addresses its role as a place of and for conspiracy. The crisis is thus seen as a ‘distraction’ from what is really happening with commentators keen to point out antecedents. For example, the theory that Syria is part of a wider plot by the US to weaken both Iran and its close ally Syria along with its ally Hezbollah in Lebanon. Other stories include the UK government under Tony Blair considering anti-Syrian activity, in alliance with the United States, because of fears that Syria was not reliable when it came to protecting Western hydrocarbon interests, including a pipeline deal involving Iran and Iraq. Conspiracy theorizing, which is hugely popular in the Middle East, has become an alternative way of viewing places like Syria, where the focus is less on ‘appearances’ and more on detecting ‘hidden’ aspects such as discovering secret meetings, covert operations, and sensitive documents.

5. Syria as a ‘leaky container’, a space with insecure borders and a place barely able to contain flows of people, arms and ideas

The most notable example of this instance is Lebanon, where the Syrian civil war has stretched across an international border and affected the political life of communities there. In November 2013, a bombing occurred outside the Iranian Embassy in Beirut killing 23 and this was attributed to a group, the Abdullah Azzam Shaheed Brigade, who are in opposition to the Syrian regime. This followed months of violence in Lebanese cities and towns such as Beirut, Sidon and Tripoli. But, it is worth bearing in mind that this spill-over is not just one way. Syria, in the recent past, has also been a space of hospitality as spill-over from the Iraqi crisis resulted in over 1.5 million people fleeing over the Iraqi-Syrian border. Spill-over has also caused anxiety to other neighbors, such as Jordan, who fear that more refugees will arrive from Syria.

6. Syria as a place indicative of international norms

In this instance Syria becomes a testing place; a place where the international community must ‘prove’ itself. The bleak stories regarding the use of chemical weapons against civilian populations in August 2013 become a moment to act – not only because of civilian suffering – but because an international norm had been violated. So in principle, the place in question is irrelevant. President Obama, for example, was swift to draw attention to the violation of such norms, and to warn that a failure to act might lead to increased risk of future usage of chemical weapons. The violation of the norm not only presents a danger in the here and now, it also points to future dangers that can now be increasingly imagined as a consequence of the attacks in August 2013. While calls for military strikes were later called off as a consequence of high-level US-Russian diplomacy, Syria remains ‘testing,’ not only of international co-operation, but also in terms of whether it can be proven that weapons of mass destruction have been safely secured. It also became a moment, repeatedly, for ‘Syria’ to be invoked as emblematic of the limits of the United Nations and the role of obstructive others.

Klaus Dodds is Professor of Geopolitics at Royal Holloway, University of London and author of Geopolitics: A Very Short Introduction and The Antarctic: A Very Short Introduction.

The Oxford Atlas Place of the Year 2013 is Syria. The Oxford Atlas Place of the Year is a location — from street corners to planets — around the globe (and beyond) which has attracted a great deal of interest during the year to date and judged to reflect the important discoveries, conflicts, challenges, and successes of that particular year. Learn more about Place of the Year on the OUPblog.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: CIA map of Syria. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Putting Syria in its place appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSeven facts of Syria’s displacement crisisPlace of the year 2013: Spotlight on SyriaThe Oxford Atlas Place of the Year 2013 is…

Related StoriesSeven facts of Syria’s displacement crisisPlace of the year 2013: Spotlight on SyriaThe Oxford Atlas Place of the Year 2013 is…

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers