Oxford University Press's Blog, page 865

December 14, 2013

Who started the Reichstag Fire?

In February 1933, upon the ashes of the Reichstag, Adolf Hitler swiftly consolidated the political power of the Nazi Party. He wielded the suspect, 23-year-old Marinus van der Lubbe, a Dutch Communist stonemason, as irrefutable evidence for an impending subversive uprising. By appearing to legitimize the sociopolitical paranoia of the Nazi party, the Reichstag fire fueled Hitler’s assumption of totalitarian leadership over the country. To this day debate surrounds the circumstances of that fateful night. Did Marinus van der Lubbe act as a lone arsonist whom the Nazis exploited as a political tool? Or was the fire started by the Nazis themselves as a way to finally cinch complete control over the country? We sat down with Benjamin Carter Hett, author of Burning the Reichstag: An Investigation into the Third Reich’s Enduring Mystery, to discuss decades of conspiracy theories and why the mystery of who started the Reichstag fire remains pertinent to this day.

On the theories surrounding the Reichstag Fire:

Click here to view the embedded video.

On Fritz Tobias and the Marinus van der Lubbe theory:

Click here to view the embedded video.

On the conspiracy theories surrounding the Reichstag Fire:

Click here to view the embedded video.

What can we learn from the Reichstag Fire?

Click here to view the embedded video.

Benjamin Carter Hett is the author of the new book Burning the Reichstag: An Investigation into the Third Reich’s Enduring Mystery. A former trial lawyer and professor of history at Hunter College and the Graduate Center, City University of New York, Hett is also the author of Death in the Tiergarten and Crossing Hitler, winner of the Fraenkel Prize.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Who started the Reichstag Fire? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMapping disease: the development of a multidisciplinary field‘Paul Pry’ at midnightNelson Mandela’s leadership: born or made?

Related StoriesMapping disease: the development of a multidisciplinary field‘Paul Pry’ at midnightNelson Mandela’s leadership: born or made?

December 13, 2013

Catching up with Sarah Brett

While we regularly bring you the thoughts and insights of Oxford University Press (OUP) authors and editors, we rarely reveal the people who work behind the scenes. I sat down with Oxford University Press Digital Development Editor, Sarah Brett, to find out more about her history with OUP.

When did you start working at OUP?

I left university in 2005 and started working at OUP in May 2006 at the tender age of 21. Can’t quite believe it’s been seven years already!

What is your typical day like at OUP?

I work on one of our online products, Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (OSEO). I’ve been in this job for about five months so I’m still learning new things and my day varies a lot. Getting content online involves working closely with lots of different departments, so there are usually emails from various people to answer throughout the day. I’m also responsible for a team of external freelancers who check the content online so I may also have to bundle documents up to send to them, or answer queries on existing work they’re doing. Because of the collaborative nature of the project I tend to have at least one meeting a day, and then when I have a free day or afternoon I will spend it actually looking at the books closely and writing guidelines for the text capture service to help them understand how to convert the text into xml (a markup language, like html, which can be customised for textual content).

My job is pretty varied as I’m in an editorial role which means a lot of digging around in old books and looking at print content, but because of the nature of an online product I also have to think about xml and how that content is behaving in the online environment. I really like the dual nature of the job.

What’s the most enjoyable part of your day?

I enjoy the detective work that’s involved. Sometimes I can be looking at a very old scholarly edition that was published in the 1930s which doesn’t conform to modern standards of typesetting or that has a really unusual structure, and trying to work out how best to present this very old book so that it behaves in a sensible way online. To add another dimension of difficulty, the editions we’re looking at contain historical material that was originally written pre-1800. For example Shakespeare in the original language and spelling often proves troublesome when it comes to text capture! It’s quite a challenge, but an enjoyable one, trying to bring the worlds of print and online publishing together.

What is the strangest thing currently on or in your desk?

I like having lots of stuff around me at my desk, it never looks tidy, so amongst other things I have a bicycle horn, a cuddly Moomin troll, and a promotional Rubik’s cube with chemical symbols on it.

What was your first job in publishing?

I started work as a Commissioning Assistant in Higher Education editorial at OUP. I stayed in that job for a couple of years working on print books but being from a bit of a geeky background I was always intrigued by the companion websites which accompanied the books. My manager at the time obviously realised that and suggested I apply for a job in the Web Team, and that ultimately led to my current job as a Digital Development Editor working on OSEO. I studied English Literature at university and I’m a bit of a history nut so this job’s pretty ideal.

What are you reading right now?

Despite studying English Literature my heart belongs to fantasy books that can offer some escapism in quiet moments so the book I’m carrying around at the moment is a rather trashy fantasy novel City of Lost Souls by Cassandra Clare, and my bedtime reading is a sci-fi book called The Educated Ape and other Wonders of the Worlds by Robert Rankin.

Tell us about one of your proudest moments at work.

It’s always nice being thanked in the acknowledgements of a book. I couldn’t be an author but I like seeing my name in print. In my new job the most exciting moment is seeing a book appear on the staging site (so online, but only visible in-house) and knowing you helped it to get there.

If you were stranded on a desert island, what three items would you take with you?

My latest knitting project, my bike, and a laptop so that I could read everything that’s published on OSEO. There’s so much interesting stuff on there that I often wish I could just spend my days at work reading it, but sadly that’s not what they pay me for!

What drew you to work for OUP in the first place? What do you think about that now?

I liked the history of the building and the company, and the fact that it seemed like a really friendly place to work — more like a college than a business. Since 2006 I’ve seen a lot of changes happen in publishing but OUP remains a lovely place to work. People are focused on maintaining the sense of history at the same time as changing our output to meet the demands of the digital age.

What is your favourite word?

Amanuensis .The little OED defines it as ‘a person who helps a writer with their work’ – which is how I guess Editors could be described, at a bit of a stretch. Plus it’s a nice word to say.

Sarah Brett is a Digital Development Editor for Oxford Scholarly Editions Online at Oxford University Press.

Katherine Marshall is a Marketing Executive for Academic Law at Oxford University Press.

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (OSEO) is a major new publishing initiative from Oxford University Press, providing an interlinked collection of authoritative Oxford editions of major works from the humanities.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only Life at Oxford articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Sarah Brett’s desk courtesy of Sarah Brett.

The post Catching up with Sarah Brett appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesUniversity libraries and the e-books revolutionShakespeare in disguise‘Paul Pry’ at midnight

Related StoriesUniversity libraries and the e-books revolutionShakespeare in disguise‘Paul Pry’ at midnight

Mapping disease: the development of a multidisciplinary field

For over two centuries, the landscape that lies on the marchland of two very ancient subjects — geography and medicine — has been explored from several directions. One of the main benefits of this intermingling has been the increased use of maps to chart the geographical distribution of diseases in the hope that the patterns revealed will give insights into the aetiologies and prevention of diseases.

Leonard Finke (1792-95) may have been the first to have written about this notion in his Attempt at a general medical-practical geography. In three volumes, this work maps out medical descriptions of the world. It contains anthropological descriptions of its peoples and their possible diseases. But the actual mapping of disease was costly even then and needed agreements on both disease definitions and adequate disease data collection. It was the 1820s before such conditions began to be put in place when the great outbreaks of cholera and yellow fever commenced in cities on both sides of the Atlantic. So some 29 cholera maps were published in the 12 years following the first great cholera pandemic of 1817 which spread from India. Most of these maps plotted routes of spread, dates, and regions of occurrence. In the following decades sophisticated maps showing the distribution of cholera within European cities began to appear. Rothenburg’s 1836 map of cholera in Hamburg and, at a local scale, John Snow’s famous map of individual cholera deaths in the Soho area of London in 1854 are examples. Although medical cartography by 1850 was beginning to be established at local and national scales, the world picture remained difficult to map except in the broadest terms.

Bornholm disease in southeast England, 1956.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Bornholm disease is a distressing illness caused by

enteroviruses in the Coxsackie B virus group. Symptoms may

include fever and headache, but the distinguishing

characteristic of this disease is attacks of severe pain in the

lower chest, often on one side. Coxsackie B virus is spread

by contact and epidemics usually occur during warm

weather in temperate regions and at any time in the tropics.

As is typical with this virus family, it is shed in large amounts

in the faeces of infected persons. The illness lasts about a

week and is rarely fatal. The average family doctor may

recognise no cases for several years and then, perhaps, only

see one or two aff ected patients in a whole summer. This

was true of doctors in southeast England during 1956, but a

collective enquiry led by Williams (later Director of the

Swansea Unit) and Watson at the Epidemic Observation

Unit for the new College of General Practitioners showed

Bornholm disease (red circles) to have been prevalent in a

band of country stretching along the lines of road and rail

from Bournemouth and Portsmouth to the London area. Yet

while this was occurring, other doctors in Sussex and East

Kent, and to the north of the aff ected area, uniformly

reported having seen no cases (yellow circles). Source:

based on Watson (1960, Figure 1, p. 318).

Malaria: the distribution of anopheline mosquitoes in southeastern England, 1918.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Extract from a work

originally prepared by William D. Lang of the Department of Entomology, British Museum, showing the localities in which

diff erent species of anopheline mosquito had been recorded in England and Wales. The preponderance of Anopheles

maculipennis (now A. atroparvus), the principal vector of P. vivax malaria in southeastern England during the outbreak of

1917–22, is clear. Source: Local Government Board (1918a, after p. 85, extract).

Plague contol Liverpool.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Onshore cases of human plague were recorded in Liverpool on several occasions in

the early twentieth century, with the years 1901 (11 cases), 1908 (3 cases), 1914 (10 cases) and 1916 (6 cases) being especially

noteworthy. Many of the cases occurred in connection with the docks and port warehouses, and exposure to plague-infected

rats at these locations is suspected. This image dates to the early twentieth century and shows staff of the Liverpool Port

Sanitary Authority dipping rats in buckets of petrol to kill fl eas. Source: Wellcome Library, London.

Enteric fever: investigation of a local disease outbreak.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

In September 1905, the Local Government Board

instructed Dr Reginald Farrar to undertake an investigation of an explosive outbreak of enteric fever in the old market town of

Basingstoke, Hampshire. This plate shows the central area of Farrar’s map which depicts the widespread distribution of notifi ed

cases (red dots) in relation to the mains water supply (blue lines). The inset shows a sketch of the bottle-shaped chalk well in

the northeastern quarter of the town from which the town’s water supply was derived. Investigations revealed that, under

certain conditions, water in the well could become contaminated with sewage matter from low-lying parts of the town. Such

conditions may have been engendered at about the time of the outbreak by work then being undertaken on the town’s sewer

system. Dissemination of enteric fever through transient contamination of the mains water supply was hypothesised.

Source: Farrar (1907, Figure A, p. 43 and unnumbered map, between pp. 56–7).

Spread of Wave II of Spanish infl uenza in the Borough of Cambridge, 1918.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Vectors trace the

time-ordered sequence of fi rst appearance of infl uenza

deaths in the districts of Cambridge, October–November

1918. The fi rst death was recorded in New Town on

1 October 1918, followed by Romsey Town (13 October),

Sturton Town (17 October), Centre (18 October), Newmarket

Road (21 October), Castle End, New Chesterton and

Newnham (all on 25 October), Cherry Hinton (28 October)

and, fi nally, Old Chesterton on 17 November. Based on

information in Copeman (1920, p. 396).

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Mortality from pulmonary tuberculosis in England and Wales, 1850–1960.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The annual rate of tuberculosis

mortality, plotted as a line trace, has been detrended and is expressed in standard score form. For reference, the number of

European countries at war in each year is plotted as a bar chart. Wartime peaks in tuberculosis mortality refl ect confl icts in

which Britain held a direct military stake (Crimean War, Boer War and the World Wars), and the overspill from continental

European wars in which Britain maintained a non-belligerent status (Austro–Prussian War and Franco–Prussian War). Source:

redrawn from Smallman-Raynor and Cliff (2003, Figure 4.1, p. 74).

Legionnaires’ disease outbreak in relation to BBC Broadcasting House, Portland Place, London, 1988.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

On

27 April 1988, two cases of Legionnaires’ disease were admitted to Rush Green Hospital, Essex. (Left) Both cases worked at the

British Broadcasting Company’s (BBC’s) Broadcasting House in Central London. (Right) Map of the outbreak area, showing the

position of Broadcasting House; the dominant wind direction during the most likely time of outbreak exposure to L.

pneumophila (19–21 April 1988; red arrow) and during an experimental tracer gas release from the implicated cooling tower

(26 May 1988; yellow arrow); and the main area where the experimental tracer gas released from the cooling tower on 26 May

was detected at street level (pink circle). Source: map (B) adapted from Westminster Action Committee (1988, Appendix N,

Figures 3 and 6, after p. 8) and Newson (2009, Figure 6, p. 100).

(Upper) Measles is back.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The interruption of sustained indigenous measles virus transmission was achieved in

the United Kingdom in the late 1990s (Section 8.3). After almost a decade of sub-optimal measles vaccination coverage in

the wake of the MMR vaccine controversy, the Health Protection Agency noted in June 2008 that “the number of children

susceptible to measles is now suffi cient to support the continuous spread of measles” and urged health services to “exploit all

possible opportunities to off er MMR vaccine(s) to children of any age who have not received two doses” (Health Protection

Agency, 2008, unpaginated). The image shows an MMR public information poster used by Lewisham NHS Primary Care

Trust, London, in 2009.

Measles outbreak in London, December 2001–May 2002.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

After an extended period in which only sporadic

cases of measles were reported in London, a cluster of cases was identifi ed among pre-school children in the south of the city

in December 2001. This marked the onset of the largest outbreak of measles in London since the mid-1990s. The epidemic was

eventually associated with 129 confi rmed and 451 suspected cases of measles; 75 percent of the cases were aged under 5 years

and, of those for which relevant information was obtained, 98 percent had no record of measles immunisation. The map plots

the distribution of confi rmed measles cases (blue circles) against a backdrop of ward-level deprivation scores (choropleth

shading; relatively dark shading categories mark relatively more deprived areas). The majority of the confi rmed measles cases

occurred in south inner London and, when compared to the distribution of contemporaneous cases of meningococcal disease

(green circles), were found to be resident in relatively more affl uent wards of the city. The evidence is consistent with a measles

outbreak in which virus transmission was driven by lower levels of MMR vaccine uptake in more affl uent localities. Source:

redrawn from Atkinson, et al. (2005, Figure 1, p. 425).

Filling in the world map awaited the work of the great German physician, August Hirsch, who avoided cartography himself but pioneered the global study of diseases. His two volume Handbuch der historische-geographische pathologie, the first edition of which was published between 1859 and 1864, was a monumental attempt to describe the world distribution of disease, drawing upon more than ten thousand sources. Hirsch had close links with England and dedicated his book to the London Epidemiological Society. Twenty years later, a much revised version was translated by Charles Creighton as Handbook of geographical and historical pathology. This time the adjectives in the title were reversed (a reversal approved by Hirsch) and the contents had swollen to three volumes, covering acute infectious diseases (1883), chronic and constitutional diseases (1885), and diseases of organs (1886).

Then Creighton himself went on to produce his magisterial two-volume A History of Epidemics in Britain, covering the history and geography of epidemic diseases in the British Isles from AD 664 to the end of the nineteenth century. Described at the time in The Lancet as “a great work – great in conception, in learning, in industry, in philosophic insight,” Creighton’s History began with the spread of a mysterious pestilence (pestis ictericia) in southern England in ad 664, and ended with an appended note on the emergence of a seemingly new disease in the 1800s (‘cerebrospinal fever’ or meningococcal meningitis). Creighton’s narrative is imbued with a sense of the historical ebb and flow of infection. It covered all the familiar infectious diseases such as measles, whooping cough, scarlet fever, smallpox, as well as a host of now unfamiliar infections in the British Isles like plague, cholera and typhus.

We attempt to continue the disease mapping tradition by extending Creighton’s account into the 21st century in The Atlas of Epidemic Britain. Creighton would have been recognised a number of epidemic outbreaks of infectious diseases in the first decade of the new millennium; there are also parallels with Creighton’s ‘new’ infection, cerebrospinal fever. In 2003, SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) reached some 30 countries around the world within a few months. In 2004, ‘Bird flu’, highly pathogenic avian influenza (A/H5N1), took the world to Phase 3 (of 6) on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) scale of alert for an influenza pandemic before it receded into the background. In 2009, swine flu, caused by a novel virus subtype of swine lineage (A/H1N1), spread globally from initial cases in Mexico to reach WHO’s Phase 6 (sustained human-to-human transmission) by 11 June. The ebb and flow of infection reveals a century of change from the historically important infections to new and re-emerging infections and a geography of epidemics of communicable diseases in the British Isles.

Professor Matthew Smallman-Raynor has been Professor of Geography at the University of Nottingham since 2004. Professor Andrew Cliff has been Professor of Theoretical Geography at the University of Cambridge since 1997 and Pro-Vice-Chancellor since 2004. They are the authors of the Atlas of Epidemic Britain, which was awarded the Public Health and Medical Book of the Year Awards at the BMA’s Medical Book Awards 2013 at the ceremony in September.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Mapping disease: the development of a multidisciplinary field appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOne drug for all to cure Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s?Why is pain in children ignored?Celebrating the life of Nelson Mandela, continuing the quest for social justice

Related StoriesOne drug for all to cure Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s?Why is pain in children ignored?Celebrating the life of Nelson Mandela, continuing the quest for social justice

Going on retreat to Middle-earth

When I first read The Lord of the Rings, I came away feeling I had just spent a week in another world. I liked the characters, loved the epic scale, and was moved by the story of endurance and sacrifice, but it was the place that really got me. I wanted to go back. As soon as possible. I wanted to wander among the ancient forests, the gleaming caverns, the towering and sometimes malevolent mountains. I missed the deep layers of time that covered even un-storied, out-of-the-way Hobbiton. And I longed for the order and meaning that underlay everything, surfacing occasionally in the form of a prophecy, an enchanted object, or a powerful working of magic.

All of that was there waiting for me in The Hobbit, though on a smaller scale and in a simpler, funnier, more fairy-tale-ish story. And then it wasn’t anywhere else. (I will beg off on judging The Silmarillion and other posthumous publications—they didn’t exist yet.)

“Where can I find more books like Tolkien’s?” I asked friends, family, teachers (in the days before internet searches). I scanned libraries and bookstores for other covers that looked like his and found the beginnings of the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, which held some wonderful discoveries but nothing quite the same. Another publisher called Del Rey started putting out books that looked like The Lord of the Rings but had none of the life or mystery. Like Gertrude Stein’s Oakland, there was no there, there. A few years later, Ursula K. Le Guin opened a portal to Earthsea, which was a place well worth visiting—for me, even a life-changing place—but not the same as Middle-earth.

The closest experience I had to that first trip to Tolkien’s Elvish realms came many years later when I was a guest speaker at a community of Benedictine sisters in central Idaho. Set in a spectacular woodland between Camas Prairie and Hell’s Canyon, far from any population center, this monastery offered temporary retreats as well as long-term residencies. As a guest of the sisters, I was put up in the guest house, where all the rooms were named for visionary women: I stayed in the Hildegarde of Bingen room. In that room at night, I experienced quiet of a sort that is hardly to be found nowadays anywhere on earth. Before my talk I had time to wander through the forest where one could, if so inclined, follow a guided trail of meditations.

Like Middle-earth, this was a place of great natural beauty and significance, a place of study and meditation. It was both Medieval and modern, built by Catholicism but open to those of other religious beliefs or none. Similarly, Middle-earth is deeply imbued by Tolkien’s faith but doesn’t (unlike C. S. Lewis’s Narnia) insist that visitors share its theology.

One of the accusations frequently lobbed at fantasy is that it is a form of escape. The implication is that any time one spends visiting imaginary worlds is time not spent doing one’s duty, uncovering injustices, righting wrongs. Reading realistic fiction doesn’t exactly overthrow tyrants either, but at least the reader is facing facts and presumably arming up for the struggle. Tolkien had a good answer to this charge. The people most concerned about escape, he said, are jailors.

But Tolkien’s comment accepts the terms of the argument. I would suggest that the function of fantasy isn’t escape at all, but retreat, and I don’t mean a military retreat but a spiritual one. What I find in Middle-earth is quiet, harmony, and self-knowledge. The quiet is the quiet of trees: not quite silence but the slow breathing of leaves. The harmony is glimpsed in all those moments that the filmed versions of both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings want us to hurry past: the pauses, the songs, the conversations. It comes from Tolkien’s powerful sense of place: for the look of a star glimpsed through branches, the smell of mushrooms in damp soil, the feel of a day’s long march through open countryside, the glow of a fire at day’s end. This harmony is why Middle-earth is worth the strife and the horror–which are the parts of the books the movies do so well. It is also the thing that gives hobbits and humans the strength to keep struggling even when there seems to be no hope.

The self-knowledge that comes of this retreat is a little harder to pinpoint. We are used to finding self-knowledge in tragedy. Oedipus teaches us about hubris, Othello about blind jealousy, Lear about how little control we have over our own existence. Tolkien’s stories are comedies: they end with treasure and marriage and return to home and hearth, rather than with alienation and death. We don’t think of comedy as a source of deep insight, but that may be because we assume the self we are coming to know is an isolated self-contained thing. Joseph Meeker, in a book called The Comedy of Survival, suggested that critics since Aristotle have gotten it wrong. The comic vision is more profound than the tragic, because it doesn’t glorify the individual. It tells us we are small, ridiculous, incomplete, and interconnected. We are, in a word, hobbits.

So I go on retreat now and again, and I come back each time remembering why I don’t count for very much in the larger scheme of things but also why I need to keep up the struggle. Each time I read The Lord of the Rings or The Hobbit, I bring back a little of that harmony, a little stillness, a little starlight. Those things are always around, but I forget to notice them. Tolkien reminds us that we too live in Middle-earth.

Brian Attebery is Professor of English at Idaho State University and author of the upcoming book, Stories about Stories: Fantasy and the Remaking of Myth. He is Editor of Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts. He is also the coeditor, with Ursula K. Le Guin, of The Norton Book of Science Fiction (Norton, 1997) and the author of Decoding Gender in Science Fiction (Routledge, 2002), among other works.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Jeff Hitchcock (Flickr: Butterfly Catcher) Creative Commons, via Wikimedia Commons

The post Going on retreat to Middle-earth appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLogic and Buddhist metaphysicsWho is Pope Francis?An Oxford World’s Classics American literature reading list

Related StoriesLogic and Buddhist metaphysicsWho is Pope Francis?An Oxford World’s Classics American literature reading list

Logic and Buddhist metaphysics

By Graham Priest

Buddhist metaphysics and modern symbolic logic might seem strange bedfellows. Indeed they are. The thinkers who developed the systems of Buddhist metaphysics knew nothing of modern logic; and the logicians who developed the panoply of techniques which are modern logic knew nothing–for the most part–of Buddhism. Yet unexpected things happen in the evolution of thought, and connections between these two areas are now emerging. (As I write this, I’m on a plane flying back to Germany from Japan, where I’ve been lecturing on these matters for the last two weeks in Kyoto University) Let me try to explain as simply as I can.

At the time of the historical Buddha, Siddhārtha Gautama, c. 5c BCE, a common assumption was that there are four possibilities concerning any claim: that it is true (and true only), that it is false (and false only), that it is both true and false, that it is neither true nor false. The principle was called the catuṣkoṭi (Greek: tetralemma; meaning ‘four points’ in English).

We know this because, in some of the sūtras, the Buddha’s disciples ask him difficult metaphysical questions, such as the status of an enlightened person after death: does the person exist, not exist, both, or neither? They clearly expect him to endorse just one of these possibilities.

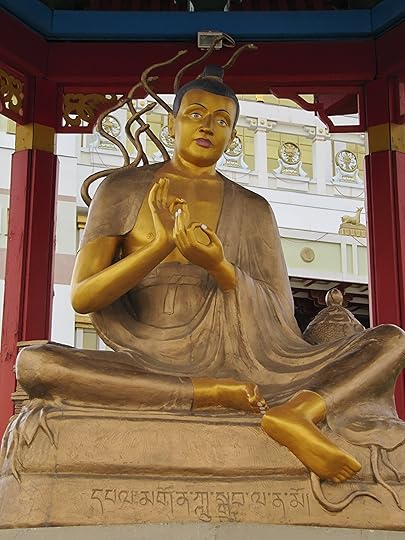

The Buddha

Until recently, Western logicians have had a hard time making sense of this. Standard logic has assumed that there are only two possibilities, true (T) and false (F)–tertium non datur. In particular, there is nothing in the third koṭi (both true and false), and even if there were, it would be in the first two as well (true, and false). So the koṭis would not be exclusive.

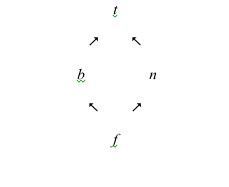

To those who know a little modern non-classical logic, however, the matter is easy. There is a system of logic called First Degree Entailment (FDE). This is a four-valued logic whose values are exactly those of the catuṣkoti (t, f, b, and n). Standardly, they are depicted in a diagram as follows:

Given this ordering, the values interact with other standard machinery of logic, such as negation, conjunction, and validity.

Matters, however, don’t end there. The Buddha refused to answer such tricky questions. Some sūtras suggest that this was because it was simply a waste of time. Others hint at the possibility that sometimes none of the four koṭis may be the case.

And this is just what later metaphysics suggested. Nāgārjuna (dates uncertain, 1st or 2nd c. CE) is perhaps the greatest Buddhist philosopher after the Buddha. His Mūlamadhyamakakārika (Fundamental Verses of the Middle Way) was a text which was to exert a profound influence on all subsequent Buddhisms. And in this, he appears to say that some things are simply ineffable. The state of an enlightened person after death, for example, is such.

This adds a fifth possibility, i, which is none of the above. It is distinguished from the first four, in that if something, A, has the value i, so does any more complex sentence formed out of A. (If A is ineffable, so must this be.)

Nāgārjuna

This still isn’t an end to the matter, however. For Nāgārjuna, and those who follow him, not only claim that some things are ineffable: they explain why they are so (roughly, these situations pertain to an ultimate reality, which is what remains after all conceptual–and therefore linguistic–imputations are “peeled off”). Clearly, speaking of the ineffable is a most paradoxical state of affairs. It would seem to show that some claims can take more than one of the five values, such as both t and i. (And lest it be thought that this is simply a feature of Eastern mysticism, one should note how many of the great Western philosophers have found themselves in exactly the same situation: Aristotle (prime matter), Kant (noumena), Wittgenstein (form, in the Tractatus), Heidegger (being).)

Again, modern techniques of non-classical logic can show how to make sense of this possibility. In standard logics, things take exactly one of whatever values are on offer. But in a construction called plurivalent logic, things can take more than one (maybe even less than one) such value. The plurality of values interact in a perfectly natural and sensible way with the other logical machinery.

What to make of these matters? Philosophers may certainly argue about this. (This, after all, is what philosophers love to do.) However, one thing is ungainsayable: Buddhist metaphysics and formal logic can profitably inform each other.

FDE was a system of logic known independently of Buddhist considerations. (It was developed in the 1960 and 70s in a branch of logic known as relevant logic.) But the development of the five-valued logic above, and plurivalent logics, were motivated, at least in part, by trying to make sense of the Buddhist picture. The metaphysics can therefore stimulate novel developments in logic—developments whose interest is not simply restricted to applications to Buddhist metaphysics.

Conversely, those with a suspicion of metaphysics in general and Eastern systems of metaphysics in particular, might be tempted to write off such enterprises as logically incoherent. They’re not. The techniques of modern logic certainly don’t show that these pictures of reality are true. However, they show that they’re as logically coherent as can be – and, moreover, they allow us to articulate the views with a precision and rigor hitherto unobtainable, and hence to understand them and their consequences better.

Buddhist views are not, of course, the only views that can work in this dialectical way. But because Buddhist views are little known in Western philosophy, they provide a particularly fruitful domain of inquiry.

And what would the Ancient Buddhist metaphysicians themselves have made of such developments in logic? We’ll never, of course, know; but my own guess is that they would have very much appreciated the enlightenment which such techniques can bring.

Graham Priest is Boyce Gibson Professor of Philosophy at the University of Melbourne and Visiting Professor at University of St Andrews. He is the author of Logic: A Very Short Introduction.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook. Subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS

Subscribe to only philosophy articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: 1) The Buddha, by Shivanjan (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0] via Wikimedia Commons; 2) Nāgārjuna, [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Logic and Buddhist metaphysics appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPlato’s mistakeCorrelation is not causationWho is Pope Francis?

Related StoriesPlato’s mistakeCorrelation is not causationWho is Pope Francis?

December 12, 2013

One drug for all to cure Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s?

Recent reports in the news have hailed a ‘breakthrough’ in the treatment of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, but is the cure — tested solely on mice — really just hype?

By Murat Emre

Recently researchers from the MRC Toxicology Unit based at the University Of Leicester provided “food for hope.” Moreno et al reported in Science Translational Medicine that an oral treatment targeting the “unfolded protein response” prevented neurodegeneration and clinical disease in an animal model — in “prion-infected mice,” a model of prion diseases which occur also in humans. In their approach the researchers exploited the natural defence mechanisms built into brain cells. When a virus penetrates a brain cell, it uses the cell’s own machinery to produce viral proteins. As a defensive response cells shut down nearly all protein production in order to stop the virus’s spread.

During prion disease, an increase in misfolded prion protein leads to over-activation of the so-called “unfolded protein response” (UPR) that controls the initiation of protein synthesis. This results in persistent repression of protein synthesis and the loss of critical proteins for cell functioning, leading to neuronal death. In their experiment the researchers showed that oral treatment with a specific inhibitor of a key enzyme for the UPR pathway prevented repression of protein synthesis and development of clinical symptoms of the disease with preservation of nerve cells. Importantly, this enzyme inhibitor acts downstream, that is, it was effective despite continuing accumulation of misfolded prion protein. These data suggest that this enzyme, and potentially other members of this pathway, may be new therapeutic targets for developing drugs against prion disease or some other neurodegenerative diseases.

This is the first time that a compound prevented neurodegeneration in a living animal. What does this mean for neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD), in which there is slowly progressing and selective loss of neurons? Many such diseases involve production of faulty or “misfolded” proteins. These “bad” proteins which can not be cleared by other mechanisms activate the same defence system as described above with grave consequences: the brain cells shut down protein production, depriving themselves from vital proteins and eventually leading to cell death. This process is thought to take place in many forms of neurodegeneration, therefore disrupting it could theoretically treat such diseases. This provides drug developers a new mechanistic pathway to work on, which may eventually yield neuroprotective drugs. Their use can halt disease progression; patients treated early may not progress and may not develop advanced stages of the disease or their complications such as dementia in PD.

This is the first time that a compound prevented neurodegeneration in a living animal. What does this mean for neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD), in which there is slowly progressing and selective loss of neurons? Many such diseases involve production of faulty or “misfolded” proteins. These “bad” proteins which can not be cleared by other mechanisms activate the same defence system as described above with grave consequences: the brain cells shut down protein production, depriving themselves from vital proteins and eventually leading to cell death. This process is thought to take place in many forms of neurodegeneration, therefore disrupting it could theoretically treat such diseases. This provides drug developers a new mechanistic pathway to work on, which may eventually yield neuroprotective drugs. Their use can halt disease progression; patients treated early may not progress and may not develop advanced stages of the disease or their complications such as dementia in PD.

This is a very exciting development, but we are still far from its application in humans. First these results need to be replicated including animal models of AD and PD. In parallel, compounds should be developed which can safely be administered in humans and that are specific for brain, then clinical trials may start which may take 5-10 years. Drug development in neurodegenerative diseases has witnessed many disappointments: compounds with dramatic effects in animal models ended up being dramatic failures in clinical trials. Along with efficacy, safety is an issue, in particular with enzyme inhibitors; this compound had untoward effects on the pancreas and mice developed a mild form of diabetes.

Despite the long way to go, this new finding gives enough reason for excitement. A drug which targets a mechanism common to a number of neurodegenerative diseases may be too good to be true, but after all, innovation starts with novel ideas, which first needs mechanistic proof of concept. That first step seems to be taken.

Murat Emre is Professor of Neurology at the Istanbul Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey. He is the author of Cognitive Impairment and Dementia in Parkinson’s Disease published by Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Experiment, © yurchyks via iStockphoto.

The post One drug for all to cure Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy is pain in children ignored?Nelson Mandela’s leadership: born or made?The neural mechanisms underlying aesthetic appreciation

Related StoriesWhy is pain in children ignored?Nelson Mandela’s leadership: born or made?The neural mechanisms underlying aesthetic appreciation

Sounds of justice: black female entertainers of the Civil Rights era

They spoke to listeners across generations from the early 1940s through the 1980s. They were influential women who faced tremendous risks both personally and professionally. They sang and performed for gender equality and racial liberation. They had names such as Lena Horne, Nina Simone, and Gladys Knight. They were the most powerful black female entertainers of the Civil Rights era. Turn up the music and enjoy the sound of justice in a specially-curated playlist from Ruth Feldstein, author of the upcoming How It Feels to Be Free.

Lena Horne

Lena Horne’s first scene from the all-black cast film, Cabin in the Sky (1943). Lucifer Jr. (Rex Ingraham) urges the seductive Georgia Brown (Horne) to “mosey over“ to see Little Joe (Eddie Anderson). As a performer in the 1930s and 1940s, Horne rejected definitions of black women as either sexualized Jezebels or as caretaking and subordinate Mammies. Instead, by emphasizing glamour, Horne carved out a unique space for herself as a distinctly modern black female performer, one who was sexual and respectable, who was desirable yet also unattainable.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Miriam Makeba

Miriam Makeba sings “Khawuleza (Hurry, Mama, Hurry)” on An Evening With Belafonte/Makeba (1965). Makeba and Harry Belafonte won a Grammy Award for this collaborative album—the first ever conferred on a South African performer. The collection of songs in Xhosa, Zulu and other African languages, was a departure from their previously largely a-political repertoire; several, including this number, posed direct challenges to white authorities in South Africa.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Nina Simone

Nina Simone sings “Four Women” at the Harlem Cultural Festival in 1969, taking on the voices and perspectives of four African American women, each from a different period in history and each burdened in her own way by gender and by skin color. In what became one of her most requested numbers from the time she first recorded it in 1965, Simone infused centuries-old stereotypes of black women with realism, dignity, pain, and anger.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Abbey Lincoln

In the opening minutes of For Love of Ivy (1968), Ivy (Abbey Lincoln) tells her white employers of nine years that she plans to leave her job as a domestic. Doris (Nan Martin) is panic-stricken, and the audience is invited to laugh with Ivy at her white boss. As the straight-haired Ivy (Lincoln in a wig), Lincoln seemed to be a considerable distance from her wordless singing on the album We Insist!, vocals that contemporary critics had compared to primal screams and an explosion of rage. Palomar pictures marketed For Love of Ivy by emphasizing this contrast between the on-screen Ivy and the off-screen Lincoln.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Diahann Carroll

The series Julia, with Diahann Carroll as the title character, chronicled the life of a young widow and mother who works as a nurse and cares for her son in a lovely garden apartment in Los Angeles. In the 1968 debut, Julia tells her future boss (Lloyd Nolan) that she is black. Producer Hal Kanter hoped that Julia would allow white audiences to “laugh with and not at my characters,” and make race seem unimportant.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Cicely Tyson

In the climactic scene of the television special, The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman (1974), the wrinkled and hunched 110-year-old former slave (Cicely Tyson) walks to a “whites only” water fountain in Bayonne, Louisiana. She does so before white authorities wielding nightsticks and guns, and as members of the black community look on. An awestruck white reporter who had interviewed Jane but left the region to cover John Glenn’s space landing, returns as a witness; he realizes that Jane Pittman is, as he tells his editor, far more than “just another human interest story.” The special earned a record-breaking nine Emmys, including a best actress award for Cicely Tyson, and cemented her reputation as an actress who could portray black women with dignity.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Listen to these women and many other influential black female performers in Ruth Feldstein’s How It Feels to Be Free Spotify playlist.

Ruth Feldstein is Associate Professor of History at Rutgers University-Newark. She is the author of How It Feels to Be Free: Black Women Entertainers and the Civil Rights Movement and Motherhood in Black and White: Race and Sex in American Liberalism, 1930-1965.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Sounds of justice: black female entertainers of the Civil Rights era appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHoliday party conversation starters from OUP‘Paul Pry’ at midnightNelson Mandela’s leadership: born or made?

Related StoriesHoliday party conversation starters from OUP‘Paul Pry’ at midnightNelson Mandela’s leadership: born or made?

‘Paul Pry’ at midnight

Until the 1840s time in Oxford, and therefore at the University Press, was five minutes behind that of London. With no uniform national time until the coming of the railways and the telegraph, the sealed clocks carried by mail coaches would have to be adjusted to Oxford or London time as they were shuttled between the two cities.

As early as 1669 there had been a daily coach service to London, which completed the journey in 12-13 hours at an average speed of 4.8 mph — at least in summer — at a cost of 12s (60p) per passenger. That was very expensive fare indeed. In 1710 a skilled man in the building trades, say a carpenter, would take more than a week to earn such a sum. There was also a substantial carrier service operating wagons between Oxford and London, commonly at a speed of around 2 mph or less. However, by 1789 the old road to London via Cheney Lane and Shotover Hill had been abandoned in favour of a new turnpike route via Headington, which now forms part of the present A40. The turnpike was abolished in 1878 as revenue declined through competition with the railways. It was this new London Road that encouraged a proliferation of faster and more frequent coach services. By 1828 the journey time between Oxford and London for passengers was down to six hours. In 1835 there were at least seventeen coach services from Oxford to London on most days including the Royal mails at midnight, ‘Rocket’ at 3 a.m., ‘Defiance’ at 10 a.m., ‘Tantivy’ at 2 p.m. (all via Henley); and ‘Retaliator’ at 11 a.m., ‘Champion’ at 11 p.m., and ‘Paul Pry’ at midnight (all via Wycombe and Uxbridge).

The Mail Coach by John Charles Maggs (1819–1896)

By 1854, in the face of competition from the railways, the array of coach services to London that had been available in the 1820s and 1830s had shrunk to just three a week. However, carriers still operated successfully, though commonly over shorter distances, by adapting to the railways and offering fill-in services to get people and goods to and from the nearest railway station. As late as 1883 there was still a multitude of carriers serving Oxford and the surrounding area.

On 11 April 1843, royal assent was given to a bill that provided for the building of a broad gauge branch line from Didcot to Oxford, terminating at a station by Folly Bridge (Grandpont). By 31 August 1843 the Oxford Railway Company’s £120,000 share issue had been fully subscribed. The mild winter of 1843-4 that followed allowed rapid progress with construction, and by 14 June 1844 the railway was open to the public. A timetable in January 1845 offered a service of nine trains a day to and from London with a journey time of around two and a half hours as opposed to the six hours taken by the fastest coach. Almost all services required that passengers alighted at Didcot and picked up the express services from Exeter and Bristol into London. Ticket prices were high: 15s (75p) for first class, 10s (50p) for second class, and 5s3d (26p) for third class; transporting a horse cost 32s (£1.60), and a four-wheeled carriage 36s (£1.80). The price of a coach journey to London, on the other hand, by this time was just 5s (25p). However, the disposable weekly income of a carpenter in the 1840s would have been no more than 3s (15p) at best. We tend to forget just how expensive travel was in the past.

Simon Eliot is Professor of the History of the Book in the Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London. He is general editor of The History of Oxford University Press, and editor of its Volume II 1780-1896.

With access to extensive archives, The History of Oxford University Press s the first complete scholarly history of the Press, detailing its organization, publications, trade, and international development. Read previous blog posts about the history of Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: The Mail Coach, 1884, by John Charles Maggs (1819–1896). Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The post ‘Paul Pry’ at midnight appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesInk, stink, and sweetmeatsUniversity libraries and the e-books revolutionKenya’s government 50 years after independence

Related StoriesInk, stink, and sweetmeatsUniversity libraries and the e-books revolutionKenya’s government 50 years after independence

Kenya’s government 50 years after independence

Like many large and diverse countries, Kenya has long debated the value of introducing a form of devolved government. That debate seems to have come full circle. The majimbo, ‘regional’, constitution of 1963 was intended to devolve authority away from the centre. It lasted less than a year. By the time Kenya became a republic, one year after independence, the pattern of a centralized state, closely modelled on the administrative structures of colonialism, had been re-established. It endured, more or less unchanged, until 2013, when elections created the institutions of a new kind of devolved government, the design of which had received clear popular backing in the 2010 constitutional referendum. The major question facing Kenya now is very simple. Will this new system — with its 47 county governments (each with its own assembly and executive governor), bicameral parliament, and a cabinet of technocrats — deliver stable and accountable government?

The short answer will probably be: not straight away. This is partly because of some ambivalence at the very centre of the state. The Deputy President, William Ruto, had campaigned vigorously against the constitution at the time of the referendum. Though the President, Uhuru Kenyatta, has insisted that he is committed to implementing the new constitution fully — and has been very vocal and visible in this — there is evidently still a degree of scepticism among senior civil servants as to the wisdom of devolution, and the ability of county governments to take on the roles allotted to them.

But the new institutions face another, perhaps even more profound, problem. Since the early 1990s, there have been two distinct forces pushing the idea of devolution in Kenya. One has been a belief that local scrutiny will make government more transparent, and will reduce corruption. In short, that devolution might reduce the clientilist politics which had long revolved around the presidency. That in turn would allow a spreading of wealth and reduce the disaffection in marginalized areas which threatened the stability of the state. The other force has been the demand to create new, localized kinds of clientilism, with a strong ethnic and/or regional content. That demand has partly come from aspiring political leaders, who encourage ethnic sentiment, but it has also come partly from the public, doubtful whether the state can ever really be transparent and fair, who hope to benefit from more local patronage. These two forces were compatible in the campaign for devolution, but in the implementation of the constitution, an ethnicized politics of devolved patronage may well conflict with a liberal vision of accountable devolved authority. There is an uncomfortable possibility that some governors will become mini-me presidents, ruling over local fiefdoms, championing the claims of those ‘indigenous’ to their counties to ensure the support of an ethnic constituency.

The very extent of popular enthusiasm for the constitution may encourage this. The extremely high turnout in the March polls was partly a result of intense competition for the presidency. But it also reflected the hope of at least some voters that county governments would reward their local constituents with access to land, or with employment, or other kinds of patronage, and that they would favour ‘their’ people over other Kenyans. Expectations are high — unrealistically so, given the very limited resources which are available to county governments. The newspapers have been full of adverts from county governments hiring new staff and of stories of ambitious investment plans. Some counties have already raised property taxes to pay for these schemes; others have allotted land for ambitious investment schemes; others have instructed private employers to hire only ‘local’ people, though they have no power to enforce such orders. Where there are tensions over the presence of ‘outsiders’ on land — notably on the coast, or in the Rift Valley — county governments will come under pressure to support the interests of those who claim to be indigenous, although their power to do so legally will be very limited.

The demands of patronage politics are already complicating devolution. Many of those elected to the county assemblies in March have been on strike, demanding higher wages and benefits. While voters criticize the avarice of their representatives, they nonetheless expect them to be rich enough to offer financial support to those who seek their help. The strike has slowed down the work of county governments, and the improved terms now offered to assembly members will put additional strain on scarce resources.

None of this means that devolution is doomed, or was a bad idea. But it does mean that the 2010 constitution will not end Kenya’s long debate over where power should lie, and how best to ensure prosperity. County governments and national governments will test one another’s strength and resolve over a number of issues: most importantly, over the exact nature of counties’ power over land, and the control of revenue derived from mineral resources, or from major infrastructure, like Mombasa port. Governors and county assemblies also have yet to work out their relationships, which may be stormy. Most of all, county governments will have to manage the expectations of voters. Balancing the demands of an established political culture of clientilism with the aspiration to a devolved government which offers transparency and accountability will not be easy.

Justin Willis is a Professor of History at Durham University, UK. His work has been largely concerned with identity, authority and social change in eastern Africa over the last two hundred years. His co-authored article with George Gona, “Pwani C Kenya? Memory, documents and secessionist politics in coastal Kenya,” was recently included in the virtual issue on Kenya from African Affairs, and is available to read for free for a limited time.

African Affairs is published on behalf of the Royal African Society and is the top ranked journal in African Studies. It is an inter-disciplinary journal, with a focus on the politics and international relations of sub-Saharan Africa. It also includes sociology, anthropology, economics, and to the extent that articles inform debates on contemporary Africa, history, literature, art, music and more. Like African Affairs on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Nairobi, Kenya: neo-classical facade of the City Hall – flags of Kenya and Nairobi – photo by M.Torres. © mtcurado via iStockphoto.

The post Kenya’s government 50 years after independence appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesNelson Mandela’s leadership: born or made?Celebrating the life of Nelson Mandela, continuing the quest for social justiceEconomic migration may not lead to happiness

Related StoriesNelson Mandela’s leadership: born or made?Celebrating the life of Nelson Mandela, continuing the quest for social justiceEconomic migration may not lead to happiness

Why is pain in children ignored?

It is hard to believe that in the mid 1980s it was standard care, even in many academic health centres, for infants to have open heart surgery with no anaesthesia but just a drug to keep the infant still.

This practice was blown out of the water by a courageous mother, Jill Lawson, who against great resistance, pushed to publicize the lack of anaesthesia during open heart surgery that her son, Jeffrey Lawson, had undergone at DC children’s hospital. After dozens of letters and requests for a review of the policy and many condescending rebuffs, the Washington Post published her story. All hell broke loose. There were dozens of news stories because every mother knew that babies feel pain. How could health professionals be so stupid?

Careful research by Dr. Kanwaljeet J. S. Anand on the same procedure for his Rhodes scholarship at Oxford had demonstrated the under medication of children following surgery and the massive stress response that infants experience when undergoing surgery without anesthesia. Anand was feted and given a prize by the British Paediatric Society. But his research was also attacked by a group of British MPs because they claimed he was experimentally torturing babies.

Over the last 30 years, there has been a huge increase in research in paediatric pain. There are some real advances in practice. Health centre accreditation standards now require recording and treatment of pain and some children’s hospitals in the USA have used their pain management as a selling feature. So, one would think that after 30 years of advances in the science of pediatric pain there would be many fewer problems with poorly or completely unmanaged pain. But it is still the case that babies are circumcised with no analgesia; sick neonates are often given 25-30 painful procedures a day without any analgesia; although 5% of children and youth have chronic pain and significant disability, at least 90% of them never get help from a chronic pain specialist; many young patients are told that their pain is “all in your head”; there are only a dozen developmental neuroscientists in the world studying pain in children; in most hospitals about 30% of the children suffer significant unrelieved pain; and many children are still terrified of needles because of poor management of pain.

Click here to view the embedded video.

So why is pain in children and youth ignored? Is it because children can’t speak out for themselves and when they cry it is dismissed because “Children always cry”? Because children as a group are not valued? Does it go unchallenged by parents because those parents believe that the doctors would of course relieve the pain if they could? Or is it the case that advocates for children’s pain have simply not been effective? Or is pain just dismissed as “a symptom”, or is seen as unimportant by health providers?

I don’t know why. Perhaps pediatric pain advocates (and most scientists in this area are advocates too) are not aggressive enough. But the science is there. Pain in children is felt, has significant short and long term consequences and there are effective ways of treating it. But will it take 30 more years for adequate pain management be the norm?

Dr. Patrick McGrath, a clinical child psychologist, has been a leading scientist in pain in children. His research on measurement, psychological mechanisms and treatment of pain has been focused on alleviating suffering. He has published 250 peer reviewed papers, 50 book chapters, 13 books and numerous patient manuals. His work has been recognized by numerous awards including being made Officer of the Order of Canada and election as Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada and Fellow of the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences. He is currently a Professor of Psychology, Pediatrics and Psychiatry and Canada Research Chair at Dalhousie University and Integrated VP Research and Innovation at the IWK Health Centre and Capital District Health Authority. He is one of the editors of the Oxford Textbook of Paediatric Pain.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Why is pain in children ignored? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe neural mechanisms underlying aesthetic appreciationCelebrating the life of Nelson Mandela, continuing the quest for social justiceMental health and human rights

Related StoriesThe neural mechanisms underlying aesthetic appreciationCelebrating the life of Nelson Mandela, continuing the quest for social justiceMental health and human rights

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers