Oxford University Press's Blog, page 864

December 17, 2013

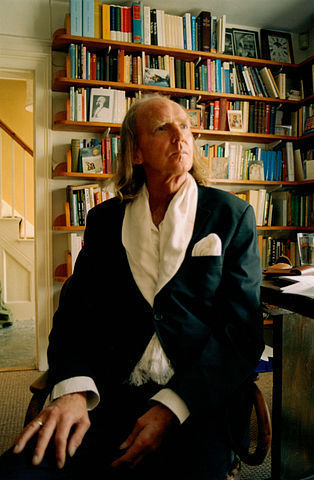

Sir John Tavener, saintly and controversial composer

The recent death of renowned British composer Sir John Tavener (1944-2013) precipitated mourning and reflection on an international scale. By the time of his death, the visionary composer had received numerous honors, including the 2003 Grammy Award for Best Classical Contemporary Composition, the 2005 Ivor Novello Classical Music Award, and a knighthood from Queen Elizabeth II. His works were almost exclusively religious in nature; nevertheless, they held appeal for sacred and secular audiences alike. This distinctive combination of spirituality and mass appeal granted Tavener a unique niche in Western classical music.

Sir John Tavener. Photo by Devlin Crow. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

Tavener’s devotion to both music and faith was evident from an early age. As a student at London’s Highgate School, which was renowned for its choral programs and frequent collaborations with the BBC in musical endeavors, he honed his already formidable skills in composition, piano and organ. He became organist and choirmaster at St. John’s Presbyterian Church in Kensington in 1961 and entered the Royal Academy of Music the following year. However, Tavener’s immersion in the doctrines and music of Western Christianity ultimately proved unfulfilling. In 1977, following his brief marriage to the young Greek ballerina Victoria Maragopoulou, he converted to the Eastern Orthodox Church. His devotion to this faith would be the guiding force of his work for the rest of his life.Tavener’s commercial success began in 1970 with the release of The Whale (1966), a dramatic cantata based on the Biblical account of Jonah and the Whale, on the Beatles’ label Apple Records. This trajectory continued in 1992, when his cello concerto The Protecting Veil (1988), inspired by the Orthodox feast of the same name and originally commissioned by the BBC for the 1989 Proms season, held the top place in the UK Classical Charts for a span of several months. The work that would complete his ascent to international acclaim was Song for Athene (1993). Ostensibly Tavener’s best-known piece, this virtuosic choral elegy drew texts from both the Orthodox funeral liturgy and Shakespeare’s Hamlet. It was originally conceived as a belated requiem for Athene Hariades, a family friend. Four years after its inception, Song for Athene was elevated to iconic status when it was performed by the Westminster Abbey Choir under the baton of Martin Neary at the 1997 funeral of Diana, Princess of Wales. As the recessional for the funeral, which was telecast from Westminster Abbey and viewed worldwide by an estimated 2.5 billion people, Song for Athene came to be recognized not only as a memorial to a specific person but also as an anthem of grief for the modern era. That this outgrowth of Tavener’s personal sorrow eventually held such grave significance for a grieving populace is a testament to the far-reaching appeal of Tavener’s music.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The compositional devices underlying a piece such as Song for Athene are manifold. Tavener counted among his artistic influences a diverse array of composers including Igor Stravinsky, Olivier Messaien, Arvo Pärt, and György Ligeti. Thus it is not surprising that his works can be found at different times to espouse and spurn the diatonic system, one moment embracing neotonal idioms and the next reveling in atonality. In the neotonal Song for Athene, Tavener employs a haunting form of melodic inversion in which two lines move in exact opposition around an inaudible line of symmetry. Orthodox influences abound in Song for Athene as well as other pieces written by Tavener during his affiliation with this denomination, manifested as settings of the Orthodox liturgy, transcriptions of Byzantine chant, and ison (drones meant to anchor the melody). Mother Thekla, founder of the first Orthodox religious order in England and Tavener’s spiritual mentor, added an additional facet of spirituality to Tavener’s music through the text that she provided for a number of his pieces.

In his final years, Tavener grew to espouse the concept of religious universalism, drawing inspiration from Eastern religions as well as Christianity. Given the tumultuous political milieu of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, this was a controversial but timely guiding principle. Tavener’s newfound approach to spirituality was embodied in The Veil of the Temple (2002), a seven-hour long setting of eight prayer cycles drawing from a vast array of belief systems including Orthodox Christianity as well as Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, and Native American religions. Tavener regarded The Veil of the Temple as “the supreme achievement of his life,” and it was a success among critics and audiences alike. More controversial was The Beautiful Names (2007), a setting in the original Arabic of the ninety-nine names of Allah as written in the Quran. Despite the fact that Charles, Prince of Wales himself had commissioned the piece, detractors claimed that in writing The Beautiful Names, Tavener had abandoned Christianity. Not to be deterred by this criticism tinged with religious prejudice, Tavener wrote, “I regard The Beautiful Names highly and think of it as one of the most important of my works.”

While Tavener was represented by turns as saintly and controversial, his ability to create works that appealed to all manifestations of human spirituality and emotion remained constant. There is no doubt that the legacy of John Tavener—an all-encompassing form of spiritual music for a changing world—will remain with us for years to come.

Emma Greenstein is currently interning for the music publications team in the Academic/Trade division. She is a trained opera singer and amateur musicologist whose interests center on music of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Sir John Tavener, saintly and controversial composer appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAn interview with marimbist Kai StensgaardTen fun facts about Claudio MonteverdiAn interview with Dan W. Clanton, Jr.

Related StoriesAn interview with marimbist Kai StensgaardTen fun facts about Claudio MonteverdiAn interview with Dan W. Clanton, Jr.

December 16, 2013

Non-belief as a moral obligation

In 1981, a professor from a small university in Canada, I found myself headed south to the state of Arkansas, to appear as an expert witness for the American Civil Liberties Union, in its attack on a new law that mandated the “balanced treatment” of the teaching of evolution and something known as “Creation Science” (aka Genesis read literally) in the science classrooms of that state. I was to testify as a philosopher that evolution is science and Creation Science is not, that it is in fact religion, and hence that its presence in the curriculum would violate the First Amendment separation of Church and State. I am glad to say that we won and the law was declared unconstitutional.

I don’t know how much my testimony helped to decide things, but I am still proud of a joke I cracked during my cross-examination. On being pressed as to my own religious beliefs I finally snapped: “I am sorry Mr. Williams [the assistant state attorney] but surely you can see that I am not an expert witness on my own religious convictions.” Except it wasn’t really a joke and it still holds. Raised a Quaker, I lost my faith around the age of twenty and am still in a state of non-belief. But where exactly I place myself in that state has long been a mystery to me. I am pretty atheistic about Christianity and other world religions, but whether I think that there is nothing at all, no ultimate meaning to life, is up for grabs. I don’t know what to think.

As always, when I am puzzled about things I like to share my doubts and inadequacies with others. One thing I have come to realize is the extent to which atheism is not just a matter of belief — true or false — but also of morality. Ought one believe in the existence of God? Perhaps expectedly, Richard Dawkins feels so strongly on this matter that he has said that raising a child Catholic is a form of child abuse. Prima facie this seems a bit odd. Surely God exists or not. We don’t say that you ought or ought not believe in the existence of the Eiffel Tower. Go to Paris and open your eyes. The God question is different, obviously, because it is not as easy to answer the question. If you go to Paris, you are not likely to bump into Him at the Louvre, or the Folies Bergère for that matter. It’s not that He doesn’t like art or pretty girls. He is just not that kind of being, and His existence is consequently somewhat clouded in mystery.

The nineteenth-century, English philosopher William Kingdom Clifford spoke in these kinds of cases of the “ethics of belief.” He argued that morally you should not believe in something unless you have good evidence. But what is “good evidence” for God? I don’t think I am speaking out of turn when I say that my good friend Keith Ward, former Regius Professor of Divinity at Oxford, is a deeply committed Christian because at one point of his life he had a personal encounter with Christ. For him, that is evidence enough and more. I have never had such an encounter; I respect the encounters of others but find it easy (too easy?) to give naturalistic explanations. Frankly I am inclined to agree with Karl Barth that natural theology — proofs for the existence of God — are not only inadequate but in some sense a barrier between the human and the divine. Why prize faith if you can have proof?

For all of my cockiness about non-belief when I was young, I had a sneaking suspicion that as I grew older and the prospect of Crossing the Rainbow Bridge grew ever closer, I would start moving back to belief. Better take out an insurance ticket just in case God exists, although if He exists and turns out to be a Jehovah’s Witness then all bets are off. At least I will have the compensation of seeing the Pope trying to dig himself out of an even deeper hole than mine. The funny thing, however, is that as I grow older (I am now in my seventies), if anything my feeling that non-belief is right for me grows ever stronger. I am sure that at least in part it is psychological. Having had one headmaster in this life, I don’t want another one in the next. But I think my feeling is also bound up with what my work on the books on atheism have taught me, together with the insights of Clifford about the morality of belief. I truly don’t know if there is anything more, but that is okay. What would not be okay, morally, would be pretending that there was something more even though I didn’t really think there was adequate evidence, or conversely pretending that there is nothing more, perhaps rather pathetically trying to win the approval of today’s very public atheists.

I suppose if everyone set about solving their problems by editing or writing books, librarians would be whining even more than they already do about the lack of storage space. But it worked for me, and at the risk of bringing down on my head the whole wrath of the Press, even if neither of my books finds a buyer at all, I will feel that it was worth producing them.

Michael Ruse is Lucyle T. Werkmeister Professor of Philosophy and Director of the Program in the History and Philosophy of Science, Florida State University. He is co-editor of The Oxford Handbook of Atheism with Stephen Bullivant. He currently writing another Oxford book, Atheism: What Everyone Needs to Know. The Oxford Handbook of Atheism is available in print and online as part of Oxford Handbooks Online.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Balance. A construction from a pebble. It is isolated on a white background. © galdzer via iStockphoto.

The post Non-belief as a moral obligation appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAn interview with Dan W. Clanton, Jr.Logic and Buddhist metaphysicsSir John Tavener, saintly and controversial composer

Related StoriesAn interview with Dan W. Clanton, Jr.Logic and Buddhist metaphysicsSir John Tavener, saintly and controversial composer

Around the world in eighty mouse clicks

Are you a geography buff? Are the facts and figures of the world your forte? Make the new year’s resolution to brush up on your knowledge of the world we live in. We’ve drawn up a quiz culled from the wealth of geographic information contained within the borders of the beautiful Atlas of the World. Broaden the horizons of your global perspective, levitate above the labyrinthine veins of London, or study the wake of a sailboat as it cuts through the deep, cerulean waters off the coast of Sydney. But, first, put your knowledge to the quiz below.

Are you a geography buff? Are the facts and figures of the world your forte? Make the new year’s resolution to brush up on your knowledge of the world we live in. We’ve drawn up a quiz culled from the wealth of geographic information contained within the borders of the beautiful Atlas of the World. Broaden the horizons of your global perspective, levitate above the labyrinthine veins of London, or study the wake of a sailboat as it cuts through the deep, cerulean waters off the coast of Sydney. But, first, put your knowledge to the quiz below.

Accept this round trip ticket for a virtual voyage around the globe and test your exploratory skills.

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Oxford’s Atlas of the World — the only world atlas updated annually, guaranteeing that users will find the most current geographic information — is the most authoritative resource on the market. The milestone Twentieth Edition is full of crisp, clear cartography of urban areas and virtually uninhabited landscapes around the globe, maps of cities and regions at carefully selected scales that give a striking view of the Earth’s surface, and the most up-to-date census information. The acclaimed resource is not only the best-selling volume of its size and price, but also the benchmark by which all other atlases are measured.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only geography articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Image taken from Oxford’s Atlas of the World

The post Around the world in eighty mouse clicks appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMaps of the worldPlace of the Year: History of the AtlasThe Oxford Atlas Place of the Year 2013 is…

Related StoriesMaps of the worldPlace of the Year: History of the AtlasThe Oxford Atlas Place of the Year 2013 is…

International Law at Oxford in 2013

Throughout 2013 the dimensions and reach of international law have continued to change at a fast pace, and Oxford University Press have been honoured to play a role in some of its scholarly highlights. Like the discipline, this has been an exciting year for our team at OUP. We’ve taken a step back to review all that has unfolded this year below.

March

The Chinese Journal of Comparative Law published its first issue in March, which is completely free for a limited time. The journal publishes content with close relevance to the development of the Chinese legal system and the wider developing world.

If you haven’t already taken it, test out your knowledge on our Public International Law Quiz which published online in March.

April

Oxford University Press Law editor Merel Alstein (right) presented the Francis Deák Prize to Robert Sloane (left) at the American Society of International Law Annual Meeting.

We attended the American Society of International Law’s 107th Annual Meeting, where OUP’s authors were honoured with an array of prestigious awards, including ASIL Certificates of Merit for two of our books:Certificate of Merit for high technical craftsmanship and utility to practicing lawyers and scholars: The Oxford Guide to Treaties , edited by Duncan B. Hollis.

Certificate of Merit in a specialized area of international law: Trade in Goods (2d ed.) by Petros Mavroidis.

The Francis Lieber Prize for Best Book on Humanitarian Law was awarded to Sandesh Sivakumaran for The Law of Non-International Armed Conflict. The Prize is awarded annually by ASIL’s Lieber Society on the Law of Armed Conflict to the authors of publications which the judges consider to be outstanding in the field of law and armed conflict.

Two of our authors were also awarded medals for personal achievements:

Bruno Simma was awarded The Manley O. Hudson Medal, given to a distinguished person of American or other nationality for outstanding contributions to scholarship and achievement in international law.

Dinah Shelton was awarded The Goler T. Butcher Medal, given to a distinguished person for outstanding contributions to the development or effective realization of international human rights.

This busy month was topped by the release of the much-anticipated 7th edition of Martin Dixon’s Textbook on International Law, offering students a concise and focused introduction to international law.

May

In May it was the turn of ASIL’s European counterpart to host international law experts, at the 2013 European Society of International Law Research Forum. We were thrilled to see many of our authors involved, including Laurence Boisson de Chazournes, Elies van Sliedregt, and Andre Nollkaemper speaking at the Opening Ceremony.

July

Oxford Public International Law launched online combining Oxford Reports on International Law and the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law to create a comprehensive, single location providing integrated access across our international law services.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The American Association of Law Libraries 106th Annual Meeting & Conference took place in Seattle this year, where we celebrated the development of the Oxford Law Citator with a wine reception and demo event.

Oxford University Press at the American Association of Law Libraries Meeting.

September

September was another busy month for us, not least because we excitedly launched our Oxford International Law Twitter. Follow us at @OUPIntLaw and tell us what you think!

We created the first of our debate maps, which review scholarly arguments and keep track of which issues have been covered and who has said what. John Louth, Editor-in-Chief of Academic Law at OUP, compiled an index that maps scholarly commentary on the legal arguments regarding the public international law aspects of the use of force against Syria published in English language legal blogs and newspapers.

Also in September, the first issue of London Review of International Law — edited by Matt Craven, Catriona Drew, Stephen Humphreys, Andrew Lang, and Susan Marks — published, which is still completely free for a limited time.

Finally, the Oxford University International Law seminars, sponsored by OUP, kicked off for another academic year.

October

We attended two big conferences this month: the International Bar Association conference and the International Law Weekend. Many OUP authors were in attendance at ILW, including Duncan B. Hollis, Sean D. Murphy, Ruti Teitel, and Curtis A. Bradley.

Oxford University Press at International Law Weekend 2013.

In October, we launched several of our key titles including the republication of An International Bill of the Rights of Man, and new editions of The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and The Law of State Immunity. We also published The Oxford Handbook of International Human Rights Law, edited by international law expert Dinah Shelton. With contributions from forty leading experts, The Handbook provides crucial insights into the field of international human rights law.

November

The second of our debate map went live: “High-profile prosecutions at the International Criminal Court: heads of state, immunities, and arrests,” created by Merel Alstein, Commissioning Editor in Law at OUP, giving an index to scholarly commentary around the International Criminal Courts.

At the end of November, the London Review of International Law celebrated the new journal’s launch at the London School of Economics. Gerry Simpson spoke about ‘the Sentimental Life of International Law,’ and a panel discussion focussing on ‘The Lives of International Law’ took place at LSE, including such speakers as Sundhya Pahuja and Aeyal Gross.

December

Human Rights Day on 10 December was a great opportunity to hear more from our authors on the international law perspective, including:

Mark Goodale’s “Taking stock: Human rights after the end of the Cold War“

“Celebrating Human Rights Day” by Frances Astbury

“US accountability for post-9/11 human rights abuses” by terrorism expert Robert H. Wagstaff

“Human Rights protection at the European Court” by Jonas Christoffersen

There’s also still time to read the journal articles available for free this month in the Human Rights Day collection.

December saw the addition of another Handbook to the series: The Oxford Handbook of International Adjudication.

Finally, the Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights launched its first War Report, edited by Stuart Casey-Maslen, the first in a new series of annual reports of armed conflicts around the world. An interactive panel debate on the Report and its implications took place with an array of international law experts and commentators.

Click here to view the embedded video.

We’ve had a very full year. Many thanks to our authors, editors, and — especially — readers for making it possible! We’re looking forward to 2014 and the new international law publishing it will bring.

Lizzie Shannon-Little is Community Manager at Oxford University Press.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in international law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide. For the latest news, commentary, and insights follow the International Law team on Twitter @OUPIntLaw.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post International Law at Oxford in 2013 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBetween ‘warfare’ and ‘lawfare’Human Rights protection at the European CourtUS accountability for post-9/11 human rights abuses

Related StoriesBetween ‘warfare’ and ‘lawfare’Human Rights protection at the European CourtUS accountability for post-9/11 human rights abuses

Three reasons why we’re drawn to faces in film

Scenes from ‘Swimming Pool’ (c. Fidélité 2003), ‘Three Colors: Blue’ (c. CAB 1993), and ‘Diva’ (c. Les Films Galaxie 1981).

Look at the array of film frames above – where do you find your gaze lingers the longest?

If we were to measure looking time (for instance, with an eye-tracking device), we would probably find that most people would scan all the pictures, but focus mostly on the frames with the faces. Even though the exterior shots and full-figure frames are more complex and colorful, our gaze would tend to fix on the faces.

What makes the human face so compelling?

Even newborns are drawn to faces. In a classic study by Robert Fantz, young infants stared twice as long at a black-and-white simplified human face than black-and-white concentric circles. Even though a bull’s-eye target is eye-catching, babies spent twice as much time gazing at a simplified face.

The vision of the newborn is sharpest at about 8 inches away—perfect for gazing at a caregiver’s face while feeding. This is an important face to learn by heart, for provision of all the basic needs of life. By around eight months, infants search the faces of those they trust for clues as to whether something new is safe to explore—or a threat from which to quickly withdraw (social referencing).

The ability to orient to, and accurately read, human faces has high survival value throughout our lives. We must register quickly if there is a stranger in our midst, and sense if this is a friendly or threatening presence. In short, we may be hard-wired to focus on faces as they provide information that is fundamentally important to our physical and social survival.

Audrey Tautou in ‘Amélie’ (c. Fox 2001)

Why are human faces so compelling in film?

Hungarian film theorist Béla Balázs believed that it is the close-up of the human face that distinguishes film from other performance arts, especially theater. Unlike a staged play, the camera can bring us up close to a face—to gaze deep into the eyes and examine every contracted muscle in intimate detail. During a time when the sweeping wide shot was in style, Balázs was instrumental in bringing attention to the power of expression through face and body in film.

Jimmy Stewart in ‘It’s a Wonderful Life’ (c. Liberty Films II, 1946)

Here, I offer three reasons that we are drawn to the human face in film.

1. Close-ups of faces personify the drama.

We have difficulty computing emotion on a large or abstract scale. The close-up of the distraught face of a single victim helps us to understand the real consequences of a devastating flood or tornado on the nightly news. Balázs writes about how the close-up of the human face captures ‘the very instant in which the general is transformed into the particular’.

Tom Hanks as Captain Miller in ‘Saving Private Ryan’ (c. DreamWorks 1998)

While wide shots reveal landscape and broader context, close-ups of the face personify and embody the emotional character of the film events on an intimate scale that can move us to the core.

Extreme close-up of Tom Hanks in ‘Saving Private Ryan’ (c. DreamWorks 1998)

2. Close-ups of faces can elicit our matching emotions.

Humans have a natural tendency to mimic and synchronize emotional facial expressions and postures and other emotional behaviors of people they are interacting with, leading to eventually taking in or ‘catching’ someone else’s intense emotions. Social psychologists call this emotional contagion, the subject of my previous post found here.

Crowd in ‘Amélie’ (c. Fox 2001)

Philosopher Amy Coplan and others have proposed that we can ‘catch’ the emotions of a film character through contagion, just as we do in real-world interactions. For instance, in one study when students watched a video of a man recounting a happy or sad story, and were videotaped without their knowledge, their facial expressions mirrored those of the storyteller. While watching a film, you may have caught yourself mimicking expressions of film characters, arching or dropping your eyebrows, grimacing or smiling in the dark!

Audrey Tautou in ‘Amélie’ (c. Fox 2001)

Psychologist Elaine Hatfield and others have shown that our tendency to mimic emotional gestures of others can eventually lead us to feel the intense emotions of another person.

Film theorist Carl Plantinga goes a step further, proposing that close-ups of the face may provide a route to empathy for the character (not just sensing the same emotions, but experiencing and understanding the feelings of another).

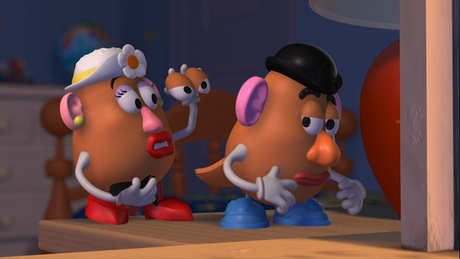

Jessie and Woody in ‘Toy Story 2′ (c. Walt Disney Pictures presents Pixar Animation Studios 1999)

3. The close-up of a nuanced face is open to interpretation – allowing us to project our own feelings, beliefs, and personal meanings.

Lastly, I suggest that while intense emotions may elicit emotional contagion, more subtle expressions may serve as a canvas for our own projections. These may be influenced by transient states such as mood – and more enduring factors such as our personal histories and associations, our own needs and unresolved conflicts.

Audrey Hepburn in ‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s’ (c. Paramount 1961)

The lingering close-up of a face presents only the illusion of being able to read the inner thoughts of another. What we think a film character may be thinking may reveal as much, if not more, about the inner recesses of our own minds.

Faye Wong as Wang Jing-wen in ’2046′ (Jet Tone Films 2004)

The Impact of Music

Other emotion-evoking elements of film—especially the presence of music—can shape our interpretations of close-ups of faces with subtle or neutral facial expressions.

Musicologist Berthold Hoeckner and colleagues found that when a film excerpt ending with a close-up reaction shot with a neutral facial expression was paired with thriller (suspenseful) or melodramatic music, college students rated the character as more likeable if they had seen the scene with melodramatic rather than suspenseful music. More interestingly, when presented later with a still image of the face, they recalled the character’s emotion to be ‘sad’ if they had seen it with melodramatic music, and ‘angry’ if it had been accompanied by suspenseful music.

In a study my colleagues and I published in 2007, Matt Spackman and Matt Bezdek and I found that music does not even have to be playing at the same time as the close-up of a neutral face, to influence our interpretations of characters’ emotions. We paired film excerpts (shown in the Figure below) with pieces of music that had been reliably judged by a pilot group to convey ‘happiness,’ ‘sadness,’ ‘anger,’ or ‘fear’. In each case, the music was played only at the beginning—during exterior shots, fading at the entry of a full-figure shot of a film character—or only at the very ending of the excerpt, after the character had left the scene.

Even though the music was never played during the close-ups of the faces, the viewers’ interpretation of characters’ emotions tended to migrate toward the emotion expressed by the music. The most surprising finding was that even music played after the character left the scene still colored viewers’ perceptions of what they had already seen. (We interpreted this as a case of backward priming).

To end with the words of the strongest advocate for close-ups of the face: ‘Good close-ups are lyrical; it is the heart, not the eye that has perceived them’.

Siu-Lan Tan is an Associate Professor of Psychology at Kalamazoo College, where she has taught developmental psychology and psychology of music for 15 years. She is co-editor and co-author of the recently published 2013 book, The Psychology of Music in Multimedia. It is the first book to consolidate the research on the role of sound and music in film, television, video games, and computer interfaces. A version of this post also appears on Siu-Lan’s blog, What Shapes Film: Elements of the Cinematic Experience on Psychology Today. Read her previous OUPblog articles.

Acknowledgments

The multi-film figure appears with permission of University California Press, as this composite was first published in Tan, Spackman, & Bezdek (2007) as listed below. The actors are Charlotte Rampling in Swimming Pool (c. Fidélité 2003), Juliet Binoche in Three Colors: Blue (c. CAB 1993), and Wilhelmenia Wiggins Fernandez in Diva (c. Les Films Galaxie 1981).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only television and film articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Mrs Potato Head (outtake)

“… I’m packing you an extra pair of shoes. And your angry eyes, just in case…”

Mr. and Mrs. Potato Head in blooper outtake to ‘Toy Story 2′ (c. Walt Disney Pictures presents Pixar Animation Studios 1999)

The post Three reasons why we’re drawn to faces in film appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow film music shapes narrativeOur kids are safer than you might thinkAn interview with Dan W. Clanton, Jr.

Related StoriesHow film music shapes narrativeOur kids are safer than you might thinkAn interview with Dan W. Clanton, Jr.

December 15, 2013

Orwell in America

“There was of course no way of knowing whether you were being watched at any given moment… but they could plug in your wire whenever they wanted to.” (George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four, 1949)

We can imagine Orwell, hands in pockets, strolling across the vast glinting car park of the NSA headquarters at Fort Meade, Maryland. He adjusts his Ray Bans to survey two massive blocks of black plate glass set in a square. He takes out his journal and writes that Fort Meade reminds him of a giant version of the Kaaba shrine in Mecca. He doesn’t know why he knows this but likes the thought. Then he sees Winston Smith leaving the building to shuffle (varicose veins) his way across the lines of baking autos before reaching the far corner and Julia, who waits. They sit in the battered Nissan. Being afraid to speak, they whisper.

Orwell, you should be living at this hour.

A medium ranking, 30 something year old man works on programmes concerned with gathering global information and using it in the interests of the state. Although he is an agency insider and enjoys the modest state privileges that derive from that, he comes to the conclusion that ‘The People’, in whose name he does these things, are not its beneficiaries but its victims, and that for all its talk of freedom and truth the state is intent on deceiving them. The man wants to admit his rebellious thoughts and reveal the deception but knows that by doing so he is going to make the rest of his life difficult, not to say short, and there will be no going back. He does it all the same. He has no accomplices, except his girlfriend. The world has yet to decide what will happen to him.

I am of course talking about Edward Snowden, who worked for the American National Security Agency before tipping its secrets last summer. But I could have been talking about Winston Smith, hero of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Winston, like Snowden, works in state security. Winston, like Snowden, acts alone. In spite of his name, Winston, like Snowden, is no action hero. And Snowden is no Jason Bourne either; a man who has spent years at the keyboard tracking the lives of others, he’s more like Jason’s enemies than the man himself.

Edward Snowden. Photo by Laura Poitra / Praxis Films [CC-BY-3.0]

Here’s my point: Winston Smith and Edward Snowden are ordinary guys. You might say geeky-ordinary. But they had access to what we do not have access to, and came to believe that the job they were doing was not ordinary but extraordinary, and was not only wrong it was pointless. They did not know why they were doing it, or for whom, other than for security itself – a dead and pointless thing locked inside dead and pointless lives.In Nineteen Eighty-Four Winston is obliged to hide in order to write his own thoughts and he and Julia have to look out for microphones hidden in the bushes. Edward Snowden on the other hand has not seen a piece of paper in years and we can be pretty sure that he has never had to bug a bush on behalf of the CIA. Instead, he sits before giant computers designed to engorge and decrypt the world’s information by bulk trawling internet servers and undersea cables. Tapping his keys, this slightly serious young man could target anyone he pleased – even the President he says, if he had written authority to do so (but from who?). He leaves no one in doubt that in slightly less serious hands this infinity of tapping could disfigure not only other people’s lives but other people’s countries too.

Orwell did not predict this. The United States in 2014 is not Oceania in 1949. There is no Big Brother for a start, and there is no plan (that we know about) to shrink the language, police the universities, close The New York Times, arrest Congress, deny science, falsify history, exterminate opponents, confiscate property, and abandon law and due process. ‘The War on Terror’ has made some very bad calls over the past ten years, but no matter how hard America’s ultra left or ultra right scream, the United States is a long way from Fascism or Communism or any kind of totalitarian dystopia. In Nineteen Eighty-Four no one dials a single telephone number let alone trawls a billion. The central device in Winston Smith’s world is not the phone but the telescreen. You see only what the party wants you to see. They, on the other hand, can see you whenever they please. Winston works in a monstrous pyramid while Snowden works for a PRISM, but as yet (as far as we know) there is nothing anything as murderous or delusional in Snowden’s world as there is in Winston’s.

George Orwell [public domain]

The decisive difference is that Snowden is not really alone. So complete was Orwell’s vision of totalitarian power – and reach – Winston and Julia have no allies or means of making allies and in the end do not even have each other. Broken down into their own selves and their own selves into tiny psychotic fragments, they are left to rot. Snowden must feel like this at times but in fact he is not short of supporters, some of them quite powerful although in the face of American diplomatic pull, all of them quite unreliable as well. For all the fuss over Mrs Merkel’s phone, it’s still not clear how far the friends and allies of the US will take their objections. Shamefully, Mr Cameron has not joined the clamour. When the British Foreign Secretary assured the British people that all those who had nothing to fear had nothing to fear, he even managed to come up with a little Orwellian nightmare of his own.After tipping his secrets Edward Snowden left Hawaii for Hong Kong on 20 May, arriving in Moscow on 23 June. There he remains. Orwell would have enjoyed the joke of Putin’s Russia as the voice of America but in truth Snowden has kicked open a hornets’ nest and, although popular opinion appears split and Capitol Hill hasn’t exactly swarmed to his defence, there can be little doubt that he has some very serious and very buzzy hornets on his side. Winston Smith had to sneak into the ghetto in search of supporters (totally without success it has to be said) but Snowden has never lacked important people willing to justify his position. When the New York Times, Der Spiegel, The Guardian, the American Civil Liberties Union, and some very influential legal and political opinion, including that of former President Jimmy Carter on the left and libertarian lawyer Bruce Fein on the right, and influential Democrats and Republicans like Patrick Leahy and Jim Sensenbrenner in the middle – when they and head of US Intelligence James Clapper all voice their various and diverse levels of support for a debate started by a man whom the other side calls an out and out traitor, then you know that unlike Winston Smith, Edward Snowden will not be a traitor for ever. The 9th December statement by the giant American information companies is just as significant. Apple, Google, Microsoft, Face book, and the rest are American brands as well as American corporations. Money counts.

Orwell spent his life loathing intellectuals and state technicians like Edward Snowden. He was sure they would betray the people. Well, Orwell did not always get it right and in this particular matter there can be no doubt that – as the cliché goes – if he was alive today the greatest political commentator of the 20th century would be supporting the young American.

For Edward Snowden recognized two great Orwellian truths; first that liberty depends on millions of private lives kept private. As a fully paid-up non-deceived realist, Orwell would have argued the difficult case as to the point at which state secrecy should end and private life begin. Second, Snowden recognized that the War on Terror is no war and the quicker we drop the impossible abstraction of it all the better. Far better that we stick to what is ordinary: ordinary law, ordinary war, ordinary security, ordinary guys. Far better too that we stick to ordinary presidents. Mr Obama should remove the little badge from his lapel and revert instead to that which we all assumed to be the case anyway – that when it comes to patriotism, ordinary presidents no more and no less than ordinary Joes don’t need a badge to prove it.

Robert Colls is Professor of Cultural History at De Montfort University, Leicester. He was born in South Shields and educated at South Shields Grammar Technical School and the universities of Sussex and York. He has held fellowships at the universities of Oxford, Yale, and Dortmund, and with the Leverhulme Trust. His latest book, George Orwell: English Rebel, published in th UK in October, and will be available in the US in January 2014.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Edward Snowden. By Laura Poitras / Praxis Films [CC-BY-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons; (2) George Orwell’s press photo. By Branch of the National Union of Journalists (BNUJ) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Orwell in America appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTatiana Shchepkina-Kupernik, Anton Chekhov, and Moscow TalesMapping disease: the development of a multidisciplinary fieldLogic and Buddhist metaphysics

Related StoriesTatiana Shchepkina-Kupernik, Anton Chekhov, and Moscow TalesMapping disease: the development of a multidisciplinary fieldLogic and Buddhist metaphysics

Our kids are safer than you might think

“Our society has run amok.”

“What is happening in our schools?”

“You aren’t safe anywhere these days.”

“It wasn’t like this when I was growing up.”

Whether through conversation with my family, friends at dinner, or concerned parents talking to me as a mental health professional, I have heard these statements with growing frequency. With many high-profile violent acts in the last year (e.g. Sandy Hook Elementary School, Boston Marathon bombings, Aurora shooting) some people perceive that our country, our communities, and even our schools have become less safe than they used to be. As a parent, I worry too. Statistically, though, these perceptions are false.

First, let’s start with some basic statistics regarding violence in the United States:

Death from firearms, either from homicide, suicide, or accident, have remained stable for the last 15 years.

Compared to 20 years ago, gun homicide has decreased 49%, and crime victimization with a firearm (e.g., mugging) has decreased 75%.

The total US homicide rate is lower than it has been in 50 years.

Violent crimes in general decreased by over 15% from 2007 to 2011.

These data are somewhat compelling. Indeed, they do not suggest that we should start telling our children they can finally accept candy from strangers. These statistics do, however, help dispel any myths that things have gotten worse. On the contrary, they have unequivocally improved from a national perspective.

What about our schools, though, and what can history tell us? We all, sadly, recall the tragic events at Columbine High School in 1999 that led to the homicide of 12 students and one teacher, 24 injured students, a community forever changed, and a national landscape of fear and uncertainty. Immediately following the Columbine shooting, a majority of Americans felt that a similar situation was likely to happen in their community (not just possible, but likely). Even a year after Columbine, only 40% of parents surveyed across the nation expressed confidence in their child’s safety at school.

The national data at that time, however, did not support these sentiments. That year, 17 students died of homicide in schools, whereas over 12,000 youth were killed in accidents or homicides outside of school. In other words, among all deaths of school-aged youth, less than 1% occurred on school grounds. Further, an interesting analysis was completed by Borum, Cornell, Modzeleski, and Jimerson (2010) that found that any individual school can expect to experience a student homicide once every 6,000 years.

To be sure, a single homicide at school is too much. These events should force us to ask how we can better protect our children and prevent these tragedies. As a school psychologist and a parent, I think that more can and should be done to ensure that these kinds of horrific events never happen. However, I take comfort in the fact that schools remain one of the safest places for our children, if not the safest place. The fact remains that our children are in more danger getting in a car than walking into a school building — yet we typically don’t give a second thought to strapping our kids into their car-seats and heading down the highway. The point is, if we are to direct our energies toward keeping our children safe, we should base these efforts on evidence and not just fear.

With that in mind, it’s important that we consider how to better direct our resources in schools. As product designers continue to leverage fear, sell bulletproof backpacks, and promote educators carrying firearms in schools, I suggest we think more about how to prevent millions of students from experiencing non-lethal violence in schools on a daily basis (e.g. bullying, harassment, discrimination), support those with mental health problems, and improve the psychological safety of our schools. We should acknowledge the positive relationships that educators develop with their students as they encourage them to become thoughtful citizens. We ought to advocate for improved access to school-employed mental health professionals such as school psychologists, school counselors, school social workers, and school nurses. We need to thank the administrator that knows our child’s name and greets them every day (no matter what) and makes them feel like a member of a community. We should promote school-wide prevention initiatives that focus on improving the entire school climate. And lastly, we must remind our children that they are safe, cared for, and loved at home, in school, and wherever they go.

Eric Rossen, PhD, is a nationally certified school psychologist and licensed psychologist in Maryland. He currently serves as director of professional development and standards at the National Association of School Psychologists. Dr. Rossen is co-editor of Supporting and Educating Traumatized Students: A Guide for School-Based Professionals. Follow him on Twitter @E_Rossen. Also read Framework for Safe and Successful Schools.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image via iStockphoto.

The post Our kids are safer than you might think appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMapping disease: the development of a multidisciplinary fieldOne drug for all to cure Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s?Nelson Mandela’s leadership: born or made?

Related StoriesMapping disease: the development of a multidisciplinary fieldOne drug for all to cure Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s?Nelson Mandela’s leadership: born or made?

An interview with Dan W. Clanton, Jr.

Dan W. Clanton, Jr., a Professor of Religious Studies at Doane College, has devoted much of his academic career to the intersection of religion and culture, lecturing and publishing on topics as diverse as the depictions of Hanukkah on the television show South Park and the overlap between the book of Jonah and the comic book Jonah Hex. He has recently co-edited two books that further explored the Bible’s influence on art and culture: The End Will Be Graphic: Apocalyptic in Comic Books and Graphic Novels and Understanding Religion and Popular Culture. In the interview below with Brent Strawn (Emory University), Clanton discusses the varied influences on his work, and the ways in which comic book designers, novelists, screenwriters, and other artists have used the Bible as a source of inspiration.

Brent Strawn: How did you first get interested in graphic novels and their pertinence to biblical studies?

Dan Clanton: I grew up with the original Star Wars films, watched Superfriends on Saturday morning, and had a Six Million Dollar Man action figure with real bionic vision, so I was a sci-fi, fantasy, superhero nerd from the get-go. However, I didn’t read a lot of comics when I was a kid, or even in college. When I was in graduate school, I met my friend Andy Tooze, and after establishing my geek credentials, he recommended a graphic novel (GN) called Kingdom Come, published by DC Comics. This GN is a collection of a four-part, limited series written by Mark Waid and painted (not drawn, which is unusual) by Alex Ross. I’m not overstating when I say that reading this GN changed not only how I looked at comics/sequential art, but it also changed my academic focus.

It’s not an easy read, for three reasons. First, it’s an “Elseworlds” story, which means it’s a “What if?” comic, so the normal plot(s) and continuities one would expect from standard DC Comics characters like Wonder Woman and Superman simply don’t apply. Second—and somewhat oddly, given the first difficulty—the plot assumes that the reader is very familiar with the history of the DC characters, as it includes numerous minor characters and subplots with little to no introductions. And third, the entire story is framed as a series of apocalyptic visions granted to a preacher who is struggling with understanding the book of Revelation. So, the reader must be up on both DC Comic history as well as apocalyptic literature.

As I was slugging my way through the first go-round, I became more impressed by and aware of the sophistication and complexity of the storytelling, as well as the way(s) in which religious concerns, and specifically biblical literature and themes, were addressed and rendered. By the time I’d finished my second reading of the book, I knew I wanted to read more GNs, and also that I wanted to see if other cultural products—like film, literature, TV, music, etc.—also dealt with these same concerns and themes. Like I said, this GN opened up a whole new world for me.

Brent Strawn: What is especially promising/problematic about the graphic novel format with regard to biblical interpretation?

Dan Clanton: Comic art, as found in comic books and GNs, is an extremely malleable medium in which to tell stories. Given certain aesthetic restraints, such as borders and two-dimensional representation, one can do virtually anything. So, when one marries that artistic potentiality with the deep histories of specific characters, say, Batman, for example, one can tell virtually any story one desires in virtually any way one desires. However, just as there are restraints in the visual component of comic art, there are also narrative constraints when one deals with an established character like Batman. There’s always a core story, a central identity, one must account for and deal with when one writes for a specific character. For example, can one write a Superman story in which Krypton never exploded? Is a Wolverine story the same if he’s been de-clawed? Now, to be sure, someone probably has written stories like these, but the informed reader would recognize that they’re the exception, not the rule; that is, that these stories violate the historical continuity of a certain character. So, when a reader engages a narrative told through the medium of sequential art about an established, familiar character, they begin with certain assumptions and background knowledge that will be reinforced, buttressed by, or challenged by this new narrative.

This is, I think, the same experience one has when reading an interpretation of a biblical text. Consider this: can one write a story about Moses in which he doesn’t lead the people out of Egypt? Is a life of Jesus possible in which he’s not crucified? As I note above, surely these stories are possible, but a knowledgeable reader would know they’re not in keeping with the biblical stories. Put differently, the background of a specific character and the plot of a specific narrative function as a baseline of sorts on which later interpreters/authors build their own versions of those characters/stories for specific communities with specific interests at specific times. This process is common to both comic continuity and biblical interpretation, and as such, can serve as a potent and promising point of contact between the two.

However, there are also problematic aspects of the GN genre with regards to biblical literature. Just as one must have a deep knowledge of Bible in order to understand later interpretations of the Bible, one must also be aware of comic history in order to understand many GN/comics today. For example, when reading the New Testament text Hebrews, one needs to know something about the stories of Moses and Melchizedek in order to comprehend the author’s claims that, like Moses, Jesus is the mediator of a covenant, but this new covenant is superior to the old one, and that, like Melchizedek, Jesus is also a high priest. Similarly, if one picks up Brad Meltzer’s 2008 GN Justice League of America: The Lightning Saga, one must know about not only the history of all the individual characters in the League, but also the history of and heroes in the 31st century Legion of Super-Heroes. Along with the issue of narrative knowledge, the GN/comic art format can also be problematic from a visual, or graphic, standpoint. That is, once one has associated a particular character with a specific image, it tends to limit the imaginative possibilities for that character. For example, when I picture Batman in my head, it’s almost always the character from the Warner Brothers animated series. Other Batmen just don’t look right, and sometimes they look plain wrong (sorry, Alex Ross!). In the same way, once a specific image of a biblical figure has become concretized, take Charlton Heston’s Moses as an example, it becomes difficult for interpreters to visualize other incarnations of that character, or to imagine that character doing things their ideal model might not do. In this case, then, the visual specificity offered by GN/comics might be a hindrance to understanding and interpretation.

Read the rest of the interview at Oxford Biblical Studies Online.

Brent A. Strawn is Associate Professor of Old Testament at the Candler School of Theology and in the Graduate Division of Religion at Emory University, where he has taught since 2001. He has a special interest in ancient Near Eastern iconography, the Dead Sea Scrolls, Israelite Religion, Comparative Semitic Philology, legal traditions of the Old Testament, and Old Testament Theology.

Dan W. Clanton, Jr. holds a Ph.D. in Religious and Theological Studies from the University of Denver and the Iliff School of Theology, with an emphasis in Biblical Studies. Since 2008, he has been the Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at Doane College. As a member of the Editorial Board for the SBL Forum, Clanton published a series of articles on the reception of the Bible in graphic novels, and was a contributor to Teaching the Bible through Popular Culture and the Arts.

Oxford Biblical Studies Online is a comprehensive resource for the study of the Bible and biblical history. With Biblical texts, authoritative reference works, and tools that provide ease of research into the background, context, and issues related to the Bible, Oxford Biblical Studies Online is a valuable resource for students, scholars, clergy, and any reader seeking an up-to-date ecumenical resource. Oxford Biblical Studies Online is vetted by a team of leading scholars headed by Michael D. Coogan.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS

The post An interview with Dan W. Clanton, Jr. appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLogic and Buddhist metaphysicsThinking of applying to medical school?Catching up with Sarah Brett

Related StoriesLogic and Buddhist metaphysicsThinking of applying to medical school?Catching up with Sarah Brett

Thinking of applying to medical school?

Applying for medical school becomes harder every year. Many would-be doctors are discouraged by mounting competition for places, achieving A* grades, spiraling student fees, and negative headlines about the National Health Service (NHS). If you’re reading this then you presumably haven’t been put off yet. But you probably do have a lot of questions. Should you apply at all? If so, which medical school is best? How do they differ? How likely are you to win a place? How much will it cost? Which medical schools to choose?

Medical students learning about stitches. Tulane Public Relations. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

Of course there are so many decisions to make and factors involved, and there’s only so much you can learn from a website.

The forthcoming Medlink Conference is a great way to answer a whole host of questions that you might have about applying to medical school. It’s a unique opportunity to speak with admissions tutors, current students, fellow applicants, and representatives of various bodies offering a career in medicine, including the armed forces and volunteer groups abroad. You will attend sample lectures to experience first-hand a ‘day in the life of a medical student’, meet real patients, and have a go at some of the skills you’d be expected to learn at medical school.

The conference is held over three days and can be an intense experience; although that’s something you would have to get used to at medical school. As a veteran of more Medlinks than I can remember, both as an attendee and a speaker, here are my tips:

Plan your trip in advance. Think of what you want to find out at Medlink. What are the questions that you need answers to before you apply? Look at the Medlink programme, and make a list of relevant questions that you want to ask each speaker.

Talk (and listen) to as many admissions tutors as you can. After all, who better to tell you how to get into medical school than the people who make the decision? Find out about their style of teaching, class sizes, unique features about their clinical curriculum, and anything else about their course that they particularly want to emphasize. These are important details for tailoring your personal statement and answering ‘why this course?’ at interview. Specific details about entry requirements (appropriate A-level subjects, grade requirements etc.) are better identified on institution websites but, if there is ambiguity, this is a good time to clarify.

Many medical schools will have current students manning the stand. Make sure you ask them about their experiences of the course, what they particularly like, and what they find difficult.

Try not to be overwhelmed. There will be thousands of other people there, and this year’s Medlink is even bigger than before, with more exhibitors and more sessions. When speaking to admissions tutors, keep in mind (or in your pocket) your list of ‘things to find out’. Don’t be put off by the seemingly dazzling academic careers of those around you, remember your own strengths and achievements and use this unique opportunity to find out as much as you can about a career in medicine.

Keep an open mind. There are so many alternatives presented at Medlink, from working overseas to working outside of clinical medicine in pure bioscience, so ask questions and find out.

Remember that Nottingham has a medical school too. If Nottingham is in your top five, try and squeeze in some time to see the university and the city.

Are you a parent accompanying your child to Medlink? Check the conference programme as there are numerous parallel sessions designed just for you, on topics such as funding and how to get into Oxbridge (a.k.a. Oxford and Cambridge Universities).

Finally, make friends and have fun! Other Medlinkers are your competition and ‘fellow travellers’ who can offer a combined wealth of knowledge (and opinions, not all of which are correct all of the time!), which can help you make your decision about applying to medical school. You might even end of on the same course together, so get chatting. Keep a look out for Medlink’s Facebook and Twitter pages too — it’ll be a great way of keeping up to date and finding out about the evening’s socials too.

Additionally, David Metcalfe, author of So you want to be a doctor?, will be hosting a tweetchat during the conference. Follow the hashtag #AskDrDavid at 7:00 pm GMT on Thursday, 19 December 2013 to discuss medical school questions with @AskDavid2013.

I look forward to seeing you there!

Kelly Hewinson is a Senior Marketing Manager for Medical Books at Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Thinking of applying to medical school? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCatching up with Sarah BrettMapping disease: the development of a multidisciplinary fieldOne drug for all to cure Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s?

Related StoriesCatching up with Sarah BrettMapping disease: the development of a multidisciplinary fieldOne drug for all to cure Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s?

December 14, 2013

Scenes from The Iliad in ancient art

Given its central role in Ancient Greek culture, various poignant moments in Homer’s The Iliad can be found on the drinking cups, water jars, mixing bowls, vases, plates, jugs, friezes, mosaics, and frescoes of ancient art. Each depiction dramatizes an event in the epic poem in a different way (sometimes inaccurately). From the judgement of Paris to Patroklos’s funeral, the war heroes, gods, and battle grounds, are brought to life. From Barry B. Powell’s new translation of The Iliad by Homer, here is a slideshow of Trojan War scenes in ancient art.

Achilles and Priam

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 24.2 - The old man, leaning on his staff, approaches from the left. Behind him slaves carry the ransom. Achilles lies on his inlaid couch, holding a knife with which he has been cutting up the meat served on the table in front of the dining couch; strips of meat hang down over the side of the table, and he holds a strip in his left hand. He has not yet noticed Priam’s presence, and he turns over his shoulder to call out to a slave boy to pour wine from a jug he holds. His shield (with Gorgon’s head), helmet, shinguards, and sword hang from the wall. Beneath the couch lies Hector, his body pierced by many wounds. This is the most commonly represented scene from the Iliad in all of Greek art. Athenian red-figure drinking cup. c. 480 bc.

The Judgment of Paris

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 24.1 - On the right a youthful Paris sits on a stone in a rural location. The sheep near his feet indicates that he is a shepherd. He holds a lyre with a tortoise-shell sounding box because he is accustomed to the beauty of song. In front of him stand from left to right: Hera dressed in a demure robe; Athena, wearing the goatskin fetish as a snake-fringed collar; and a buxom Aphrodite, holding a scepter and the “apple of discord” that Paris has awarded to her. Athenian red-figure water jar, c. 450 bc.

The Funeral Games of Patroklos

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 23.2 - Greeks perch on bleachers to watch the chariot race. Some of the spectators are standing, some sitting, some gesticulating as the four-horse chariot approaches. The nearest horse is white, the next two bays with black faces, and the fourth is black. Inscriptions in front of the horses say “Sophilos painted me” and “The funeral games of Patroklos.” On the other side of the bleachers is written Achilles. Fragment of an Athenian black-figure wine-mixing bowl, c. 570 BC.

Achilles Kills the Trojan Captives

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 23.1 - Here Achilles prepares to cut the throat of a beardless Trojan youth. Achilles stands in “heroic nudity,” but wears a cloak, in front of the pyre. A label across the bottom reads “tomb of Patroklos.” Achilles grips the Trojan victim by the hair, the man’s hands tied behind his back. Behind Achilles, to the far left, is the next Trojan in line, wearing a Phrygian cap. On top of the pyre and in front of it is stacked Patroklos’ armor that Achilles has taken from Hector, once his own armor: two breastplates, a helmet, a shield, and two shinguards. To the right, a fully clothed Agamemnon, holding a scepter, pours out a libation from a phialê, a kind of offering dish. A jug of wine or honey stands beside the pyre at Agamemnon’s feet as in Homer’s description. South Italian red-figure wine-mixing bowl, c. 340–320 BC, from Canosa.

Achilles Drags Hector

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 22.2 - Achilles (labeled) has already tied Hector to his car. As he steps up behind his charioteer, he looks behind at Priam and Andromachê lamenting from the wall. His shield bears a triskelis (“three-legged”) design. Iris appears (she is white) to ask him not to treat Hector in this fashion (see Book 23). Behind the horses is the tomb of Patroklos. His breath-soul (psychê), shown as a miniature winged armed warrior, hovers above the tomb. Patroklos’ name is inscribed on the tomb. Notice the serpent at the base: The beneficent spirits of the dead were thought to live a friendly snakes in tombs (“good spirit,” agathos daimon). Athenian black-figure wine-mixing bowl, c. 510 bc.

Achilles Kills Hector

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 22.1 - The figures are labeled. The illustration does not follow Homer’s account very well. Both men are in “heroic nudity.” A beardless Achilles attacks from the left, wearing shinguards, a helmet, and carrying a hoplite shield, sword, and spear. The bearded Hector is similarly armed (but without shinguards). He has already been wounded in the left thigh and in the chest and is about to go down. Blood flows from the wounds. Athena (half-visible) stands behind Achilles wearing the goatskin fetish as a cape. Athenian red-figure wine-mixing bowl by the Berlin Painter, c. 490–460 bc. Found at Cerveteri, Lazio, Italy.

Achilles’ Horses

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 19.3 - The great hero prepares his team of divine horses for battle. Here they are named Chaitos (probably short for Pyrsochaitos, “red-haired”) and Eutheias (“straight-ahead”) instead of Xanthos and Balios. With his right hand Achilles (labeled) adjusts the harness and with his left holds the horse’s mane. He is “heroically nude” from the waist down, but wears a breastplate and shinguards. To the far right Automedon (?) seems to attach a trace horse. Between Achilles and Chaitos are the words “Nearchos painted me.” Fragment of an Athenian white-ground vase, c. 560 bc.

Achilles Receives the Arms from Thetis

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 19.1 - Thetis hands her son, in “heroic nudity” and carrying a spear, a wreath of victory. With her other hand, she give him a “Boeotian” shield. Behind her a Nereid named Lomaia (“bather”?), not named by Homer, carries a breastplate and what seems a jug for oil. Behind her an unnamed Nereid carries the plumed helmet and the shinguards. To the left, an armed Odysseus keeps guard (not in Homer). The figures are labeled. Detail of an Attic black-figure hydria, c. 550 bc.

Peleus Wrestles Thetis

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 18.2 - Thetis is dressed in an elaborate gown, probably linen, and an elegant cloak. She tugs at her hair-covering while turning into various shapes to escape Peleus’ attentions, here symbolized by the lion that bites Peleus on the arm. The young beardless Peleus wears only a shirt and a sword. It is not clear what the building on the right symbolizes. According to the story, Peleus hung on in spite of the transformations until Thetis relented and agreed to marry him. Athenian red-figure wine-cup, c. 490 bc, from Vulci, Etruria.

Fight Over Patroklos

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 17.2 - Big Ajax, on the left, holds a “Boeotian” shield, either an artistic adaptation of the ancient Mycenaean figure-of-eight shield or an actual shield shape (but no such shield has been found). His opponent is presumably Hector, holding a shield with a “triskelis” blazon, a design showing three running legs. Other unnamed Trojans and Greeks fight. Patroklos’ corpse lies in the center. Black-figure wine-drinking bowl in the style of Exekias, c. 530 bc, from Pharsalos, Greece.

Hector and Menelaos Fight Over Euphorbus

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 17.1 - Hector is on the left, Menelaos on the right, while Euphorbos lies dead between them. The warriors, labeled, are armed as classical hoplites. Hector’s shield is emblazoned with a crow. Two apotropaic eyes (“turning away evil”) are suspended from a central decorative device. Hector does not actually fight Menelaos over Euphorbos in the Iliad, but he tries to. The philosopher Pythagoras (c. 570–c. 495 bc), who taught

metempsychosis, claimed to be a reincarnation of Euphorbos. He said that he recognized Euphorbos’ shield as his own, hung in the temple to Hera at Argos where Menelaos had taken it. An early representation of an Iliadic scene on a plate made in Rhodes around 610 bc.

Death of Sarpedon

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 16.2 - Sleep and Death prepare to carry away the dead Sarpedon in the presence of Hermes. Two unknown warriors, Leodamas and Hippolytos, look on from either side. Sleep, to the left, and Death, to the right, are winged, but otherwisefully armed mature warriors. The naked Sarpedon, stripped of his armor, is pierced by three wounds. The messenger-god Hermes wears a traveler’s cap with broad brim and carries his wand, the caduceus. One of the most celebrated of ancient paintings, the Euphronios wine-mixing bowl was a possession of the Metropolitan Museum in New York City between 1972 and 2008, when it was repatriated to Italy. It is now in the Villa Giulia in Rome. Athenian red-figure wine-mixing bowl signed by Euxitheos (potter) and Euphronios (painter), c. 515 bc, found in Cerveteri, Italy.

Ajax Defends the Ships

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 15.2 - A bearded Ajax, clad in helmet, breastplate, and shinguards, attacks Hector (?), who backs off before the prow of a ship. Hector holds a curiously shaped shield. Between them a dying beardless Achaean falls to the ground, a folded leg and one hand touching the earth. Etruscan two-handled water jug, c. 480 bc.

The Arming of Hector

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 15.1 - Hector arms for battle in the presence of Priam and Hekabê. Hector has already donned his shinguards and now pulls a breastplate around his middle over a shirt. His mother, represented as a young woman, holds out his helmet with her right hand and with her left holds his spear. Hector’s shield, decorated with the head of a satyr, leans against Hekabê’s leg. The aged Priam, with balding head, supports himself with a knobby staff and instructs his son. The characters’ names are inscribed. Athenian red-figure water-jug, c. 510 bc.

The Duel between Hector and Ajax

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 14.2 - Hector falls to his knees as Ajax stabs him with his spear—unlike in Homer’s text, in which Ajax hits him with a stone. To the right of the illustration, Aeneas comes to the rescue. Ajax wears a linen breastplate and bronze plumed helmet and shinguards. Hector wears a plumed helmet and shinguards but is otherwise “heroically nude.” Hector’s shield has an unusual design, perhaps a basket on its side filled with flowers. The figures are labeled in Corinthian script. Corinthian black-figure wine-jug, c. 570.

Combat between a Trojan and a Greek

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig. 12.2 - They are dessed as hoplites. The warrior on the left spears the other fighter in the chest. Frieze on the tomb of a Lycian prince, the Heroon of Goelbasi-Trysa, Turkey, c. 380 BC.

Trojan and Greek Warriors Fighting

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 12.1 - One warrior grabs the other by the hair as he flees. The tree on the left may be the “oak of Zeus” where Sarpedon recovered (Book 5). Frieze

on the tomb of a Lycian prince, the Heroön of Goelbasi-Trysa in Lycia, Turkey, c. 380 bc.

The Killing of Rhesos

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 10.3 - Oddly, the adventure with Rhesos is never shown in Greek art until the fourth century bc. The scene on this pot, made in southern Italy, seems to be inspired by a scene from a tragedy included in the works of Euripides, the Rhesos. To the right, Odysseus, “heroically nude” and wearing a cloak and skull cap and brandishing his sword, seizes the prize horses. Diomedes stands at the left. At the top are three dead Thracians in contorted poses. South Italian red-figure jug by the Lycurgus Painter, c. 360 bc.

The Capture of Dolon

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 10.2 - The Trojan stands in the center, wearing a wolf skin and a weasel cap, with his bow and arrow, just as Homer describes. He raises his hands in a gesture of surrender to Odysseus, who wears a cap inspired by Homer’s description of the boar’s tusk helmet. Odysseus carries a sword, as Homer describes, and Diomedes to the right carries a spear. Both Greeks are in “heroic nudity.” Probably the comic exaggeration of the figures depends on a southern Italian so-called phlyax play, a burlesque dramatic form that developed in the Greek colonies of Italy in the fourth century bc. South Italian red-figure wine-mixing bowl, c. 380 bc.

Embassy to Achilles

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 9.1 - Achilles sits on a chair covered by a goat skin, his head wrapped in a cloak of mourning, his hand to his head in grief. He holds a gnarled staff. Opposite sits Odysseus, with his characteristic hat on his back, holding two javelins. Behind Odysseus stands the aged Phoenix with a staff similar to Achilles’, and on the right Patroklos looks on, leaning on his own staff. Ajax does not appear. Athenian red-figure vase, c. 480 bc, by Kleophrades.

The Duel Between Hector and Ajax

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 7.1 - Behind Ajax, on the left, stands Athena, protector of the Achaeans. She wears a helmet and the goatskin fetish (aegis) around her shoulders. With her left hand, she touches Ajax’s helmet, giving him strength, and holds a down-turned spear in her right hand. Ajax is dressed as a fifth-century hoplite, including shinguards, but is barefooted. He holds a hoplite shield (not a “tower shield”). Behind Hector on the right stands Apollo with his bow and a quiver over his shoulder, protector of the Trojans. Hector is shown in “heroic nudity.” Wounded in the chest with blood streaming out, he leans back to avoid the point of Ajax’s spear. Between the two figures, above Ajax’s shield, is a large stone, standing for the rocks the fighters threw at each other. Athenian red-figure wine-cup, 490–480 bc.

The Wounded Aeneas

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 5.1 - The bare-breasted Aphrodite stands to the left, her cloak around her head in a gesture typical of Roman gods. The physician Machaon cuts the missile from Aeneas’ leg, who stands stoically holding his spear, his sword at his side, dressed in a breastplate. The boy would be his son, Ascanius (or Iulus), famous from Vergil’s Aeneid (c. 19 bc). Other Trojan warriors stand in the background. Fresco from Pompeii, first century ad.

The Duel between Menelaos and Paris

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 3.2 - On the left, Helen, holding a piece of yarn (?), stands behind Menelaos as he draws his sword and attacks Paris, just as Homer describes. Paris holds a spear in his right hand and runs away, but Artemis—with her emblem, the bow—not Aphrodite, stands behind Paris, perhaps because Artemis always favors Trojan affairs. The warriors are dressed as typical fifth-century bc hoplites with breastplate and helmet, except that they do not have shinguards (greaves). Their shields have a strap for the arm and a handgrip, never found in Homer, where shields are suspended over the shoulder by a baldric (telamon); some shields are as large as the whole body (see Figure 4.1). The artist is recreating the scene to include elements he remembers from Homer’s story, but he is careless about details. Athenian red-figure wine cup found in Capua, Italy, c. 480 bc.

The Taking of Briseis

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 1.2 - Achilles sits in a chair holding his spear while Patroklos, his back turned to the viewer, a sword slung over his shouder, hands over Briseis to Agamemnon’s men. To the far left stands Talthybios with his herald’s wand. Achilles’ tutor Phoenix stands behind his chair. Four armed warriors stand at the back against the wall of the tent. Roman fresco from Pompeii, c. first century ad.

The Rage of Achilles

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 1.1 - The seated Agamemnon holds the scepter of authority and sits on a throne, his lower body wrapped in a robe. Achilles, in “heroic nudity,” pulls his sword from its scabbard (“heroic nudity” is an ancient artistic convention of unclear meaning, whereby heroes are shown without clothes). Athena seizes Achilles from behind by the hair. Roman mosaic from Pompeii, c. first century ad.

Barry B. Powell is Halls-Bascom Professor of Classics Emeritus at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. He is the author of a new free verse translation of The Iliad by Homer. Read our previous posts on The Iliad.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Scenes from The Iliad in ancient art appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCharacters from The Iliad in ancient artGods and mythological creatures in The Iliad in Ancient artMaps of The Iliad