Oxford University Press's Blog, page 860

December 28, 2013

A year of reading with the OUP Publicity team

‘Tis the season for gift guides and round-ups, so our US Publicity team took a quick break from pitching the OUP front list to reflect on their year in reading…

Christian Purdy, Director of Publicity:

Christian Purdy, Director of Publicity:

When I saw the jacket art on American Psychosis earlier this year I was reminded of one of my favorite contemporary photographers, Christopher Payne, and his collection of photos of dilapidated and decaying asylums here in the US published by MIT back in 2009. It still makes a great gift for that hard to buy for person on your list. Asylum: Inside the Closed World of State Mental Hospitals by Christopher Payne.

Tara Kennedy, Senior Publicity Manager:

Tara Kennedy, Senior Publicity Manager:

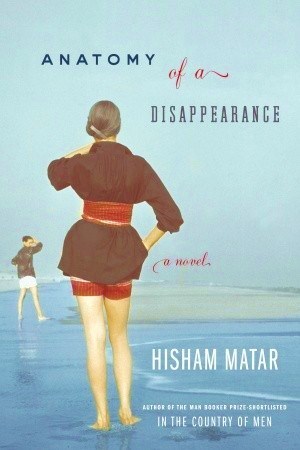

“I bought Anatomy of a Disappearance by Hisham Matar, along with some others, intending to read it over my vacation. It ended up sitting in my still-to-be-read pile for a while but I fell in love with it as soon as I started it. It made me sad, curious, anxious and captivated all at once. As soon as I finished it, I bought In the Country of Men. That one now sits in my still-to-be-read pile because I’m saving it for just the right moment.”

Alana Podolsky, Associate Publicist:

Alana Podolsky, Associate Publicist:

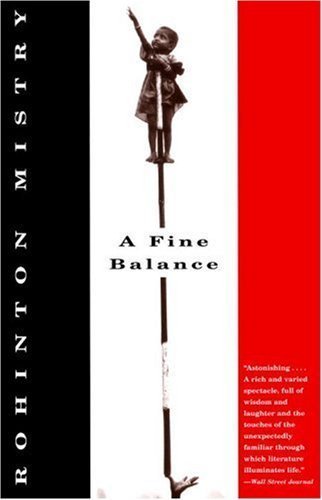

“I’m ashamed I let Rohinton Mistry’s A Fine Balance taunt me from my bedside table for years. In a Tolstoyian feat, Mistry weaves together the lives of four individuals, all dealing with some form of grief and exile, and the hundreds of moments that stay with them over a lifetime. I’m in awe of his quiet and nuanced ability to tackle hardships and celebrate the power of the human spirit and relationships.”

Jonathan Kroberger, Publicist:

Jonathan Kroberger, Publicist:

“I can’t think of a better way to judge a book than by how many times you miss your subway stop while reading it. All of these books made me late for work this year (sorry Purdy): George Saunder’s CivilWarLand in Bad Decline stands out for its perfect weirdness, James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room for its heartbreaking account of doomed love, and Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse for its existential punch in the gut. Bonus pick: I got some weird looks on the subway reading Life’s Vital Link: The Astonishing Role of the Placenta, which is genuinely fascinating.”

Jeremy Wang-Iverson, Senior Publicist:

Jeremy Wang-Iverson, Senior Publicist:

“I’ll mention a new book, an old book, and an OUP book. I recently checked out the e-book for The Lowland by Jhumpa Lahiri from my library and enjoyed it very much. I feel very grateful to have come of age as a reader as she did as a writer and while short stories might be what she’s best at, this is a very good novel. And during the fall I read Daniel Deronda by George Eliot as part of a book club at Community Bookstore in Park Slope. This is a very moving novel about understanding and accepting what one person is able to offer another, when undying love just isn’t in the cards. At the beginning of the year I worked on Louis Michael Seidman’s On Constitutional Disobedience, and his provocative argument in this short book — that we must rethink the role of the Constitution — touches on many aspects of our dysfunctional modern government.”

Lauren Hill, Associate Events Manager:

Lauren Hill, Associate Events Manager:

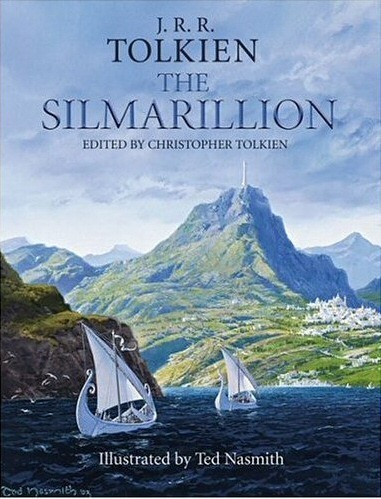

“Maybe I shouldn’t admit this, but I’m reading The Silmarillion, J.R.R. Tolkien (edited by Christopher Tolkien) for the second time, and only on this re-read is it hitting me just how amazing this book is. Tolkien’s mythos is simply astounding in its depth and breadth, and you don’t get a true sense of just how deep the mythology goes from The Lord of the Rings or The Hobbit. The Silmarillion is, in essence, the history of the creation of Middle-Earth as seen through the eyes of the Elves, and it’s filled to the brim with magnificent names and languages and places and heroes. In its finest moments, it’s easy to see why just about every fantasy series that’s been written since has its roots in Tolkien.”

Sarah Hansen, Publicity Assistant:

Sarah Hansen, Publicity Assistant:

“(1) Loving Frank, by Nancy Horan tells the story of Mamah Borthwick, the lesser known yet infamous mistress of Frank Lloyd Wright. It employs a fictional auto-biographical voice as it traces Mamah’s story from her unhappy marriage to her love affair and subsequent world travels with Frank Lloyd Wright. Throughout the story, the book acts as a social statement about a woman’s right to choose love over in early 20th century society, as well as provide historical context for FLW’s Oak Park architecture. (2) The Rosie Project, by Graeme Simson is about the seemingly impossible love between a university professor with asberger syndrome and his wild child crush. Don Tillman, a geneticist who spends most of his time teaching, decides that finding a lifelong mate is easier through a questionnaire rather than the often chaotic process of dating. The questionnaire is designed to weed out all applicants with traits that Don finds ‘unbearable’. Much of the plot and comic relief in the book comes from Don falling in love with a smoking bar tender with spiky red hair who challenges all of his preconceptions of the ‘perfect’ mate. A fun and light read.”

Owen Keiter, Associate Publicist:

Owen Keiter, Associate Publicist:

“The Truth about Marie is a kind of tryptich: three short, cinematic scenes — an escaped horse on an airfield; a medical emergency in the night; a wildfire on Elba — disconnected in time but together telling the story of a broken romance. Gorgeously done stuff, as is usually the case with Toussaint (see also: Running Away, Reticence, Monsieur, etc). The combination of extremely European humor and bittersweet beauty feels sort of like a Fellini film.”

Stay tuned for more best of 2013 blog posts…

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A year of reading with the OUP Publicity team appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOxford University Press holiday trimmings around the globeOxford Music in 2013: A look backHoliday party conversation starters from OUP

Related StoriesOxford University Press holiday trimmings around the globeOxford Music in 2013: A look backHoliday party conversation starters from OUP

December 27, 2013

Reflections on a year in OUP New York

One year. It sounds like a long time, but it feels so much less. Just over a year ago, during the buzz of the Olympics, I packed my bags to move from traditional Oxford to the metropolis that is New York. Being invited to write for this blog has allowed me to reflect on my time here, thus far, and how OUP and life in general differs across the proverbial pond.

The truth is that OUP on both sides of the Atlantic has a huge number of similarities, both are full of hard working people passionate about publishing, both are adapting rapidly to the changes and opportunities that 21st century publishing present, and, thanks to our global nature, there are even a lot of familiar faces. Working in both the medical books and journals teams, I’ve been able to appreciate how the day to day practice of publishing differs on both sides of the pond across two business areas. Language, of course, is the most obvious, and perhaps most clichéd difference. I have long got used to my spellcheck “correcting” my emails, removing u’s and adding z’s, but there are little nuances which still catch me out. The most striking difference is within the subject area and how much medicine differs, especially in my area, psychiatry. It’s been hugely rewarding to learn about the US healthcare system, the place of psychiatry within it, and to continue to work with incredibly intelligent and inspiring authors and editors. There are of course those differences which while unremarkable and frankly tedious cause endless moments of confusion. These are mainly based around I.T. and how identical programs are of course not identical, but have subtle yet crucial differences…

On the face of it, comparing Oxford to New York should be like chalk and cheese, but there are more similarities than you’d first believe. Both cities have young, ambitious populations, both full of hyper-smart go getters, and both architectural miracles. Granted the dreaming spires of Oxford differ to the glass canyons of New York, but here and there similarities are spotted, with the neo-classical pillars of Grand Central Station oddly reminiscent of the Ashmolean. The big difference is the pace of life. Oxford is frenetic in its own way, with cyclists threatening at every turn, but New York is a city on fast forward. The difference can take some getting used to, but like so much in life, its best just to jump in and enjoy the ride.

Life outside work in the two cities does differ dramatically. For someone who spent too much time on a river in Oxford rowing and coaching rowing, the lack of a rowable river has forced a change, and the steep learning curve of learning American sport(s). Softball seemed like the perfect sport to try, with the promise of relaxed games in the evening sun and a few beers in bars after; and indeed it has been the case, although it is far from what I pompously thought of as advanced rounders. For a seemingly simple game, it has a lot more depth than I thought, and is all the more enjoyable for it. Of course, many challenges remain, using a mitt to catch remains unnatural but at least the taunts about cricket are getting fewer…

Overall, the transition between the two offices has been much less daunting than could be expected. As in Oxford, the New York office is not just marked out by hard working intelligent colleagues, but by a warmth and friendliness that I can’t believe exists elsewhere. Despite the accent (which receives less comment than hoped…), I have been accepted and even jokes about 1776 go down relatively well. It has been a huge opportunity to learn about life in a different country and long may the adventure continue. If you are ever presented with the opportunity to move offices to another country, I cannot recommend highly enough that you should seize it, and run with it.

Chris Reid has been an editor at OUP for over seven years. He has worked in both the medical books and journals divisions, in both the US and UK offices and has a wide range of experience across books, journals, and digital publishing. Chris holds a BA (Hons) in Archaeology and Anthropology from the University of Durham.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image courtesy of Chris Reid.

The post Reflections on a year in OUP New York appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOxford University Press holiday trimmings around the globeLooking for clues about OUP Canada in an early photographChristmas quotations from Oxford World’s Classics

Related StoriesOxford University Press holiday trimmings around the globeLooking for clues about OUP Canada in an early photographChristmas quotations from Oxford World’s Classics

Benazir Bhutto’s mixed legacy

Benazir Bhutto, the daughter of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, had been prime minister of Pakistan twice: first in December 1988, and a second time in October 1993 after the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) managed to win two elections under her leadership. Both times the presidents (heads of state) dismissed Bhutto before she completed her full term. After losing the 1997 parliamentary elections she exiled herself until December 2007 when she returned to Pakistan to run for elections, called by exiting President General Pervez Musharraf. Assassinated on 27 December 2007, it is not clear whether she would have won that election as she was also contesting against another popular leader Nawaz Sharif of Pakistan Muslim League.

The Harvard- and Oxford-educated Bhutto came to power with a lot of promise. For one thing, she had much of the charisma and oratory skills of her late father, and she showed quite a bit of courage in dealing with the country’s ever powerful military. She also had considerable goodwill and support among Western and even Indian elite and opinion-makers. During her tenure as Pakistan’s ruler she had to face significant opposition from the Army, presidents (formal heads of state), opposition parties, and Islamist groups.

Bhutto’s long-term legacy in most areas, especially the security and foreign affairs realms, is largely negative. She made some peace overtures toward India, but none were successful. However, two of her initiatives would prove fatal for Pakistan’s, and global, security. The first was the strong support her government extended to the Taliban in its civil war with the Northern Alliance in Afghanistan in the 1990s. The Taliban’s victory in September 1996 was possible because of the material and political support Pakistan provided while she was in office. She appointed a pro-Taliban interior minister, Naseerrullah Babar, who spearheaded Pakistan’s military support to Taliban. It is possible she was undertaking such a policy at the behest of the powerful army and conservative clerics to checkmate India, but the consequences were far and wide, with the victorious Taliban spreading its influence into Pakistan and extending support to al-Qaeda and eventually enabling the 9/11 attacks.

The second area in which Bhutto played a dangerous role was in the spread of nuclear materials and technology. She was prime minister when the A.Q. Khan network engaged in several of its activities spreading nuclear materials and weapons designs to countries such as North Korea, Iran, and Libya. Bhutto revealed in an interview with journalist Shyam Bhatia that she carried CDs in her overcoat containing nuclear weapon designs to Pyongyang in return for North Korean missiles for Pakistan’s nuclear delivery systems, a confession she later recanted.

Bhutto’s efforts to improve relations with India also proved to be unsuccessful. Initially, she was able to build a rapprochement with Prime Ministers Rajiv Gandhi and V.P. Singh. Like the other military and civilian rulers of Pakistan, her effort was also aimed at obtaining strategic parity with India. In response to India’s suppression of the renewed insurgency in Kashmir in the late 1980s, Bhutto’s government increased Pakistan’s support for radical groups fighting for Kashmir liberation, leading to considerable strains in relations with New Delhi. In addition, the efforts at nuclear weapons development were increased during her tenure despite the military’s attempt to hide the details of the program from her.

Benazir Bhutto, photographed at Chandini Restaurant, Newark, CA in 2004. Photograph by iFaqueer. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

In these areas, Bhutto adopted a hard realpolitik approach partially to placate the army and its powerful intelligence wing, the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). She wanted to appear tough in her dealings with Pakistan’s neighbors, as well as towards her domestic opponents.

The domestic political and economic situation under her rule also worsened as a result of the constant efforts by the army and civilian opposition, as well as the presidents, to undermine her authority. Moreover, her husband, Asif Ali Zardari, was involved in bribery and extortion cases, and was sent to jail after she left office in 1996 for six years. He was known as “Mr. 10 Percent” for the commissions he had allegedly obtained from clients for favors from the government. This happened despite the fact that the Bhutto and Zardari families were two of the wealthiest in Pakistan.

After Benazir Bhutto’s assassination in December 2008, Zardari was elected president largely due to the sympathy vote, and showed a more conciliatory approach towards the army and the opposition parties than his wife did. Largely because of this, he was successful in completing his term in office even though the country’s situation in the economic and security dimensions worsened during his rule. The army’s cooperation under General Ashfaq Kayani was also pivotal for his completing the full term.

Benazir Bhutto inherited a bitterly polarized and Islamized Pakistan left by General Zia-ul-Haq. She at times acted as a Sunni Muslim to placate the majority and did very little to remove the difficulties faced by her own Shia minority community. Nothing was done to remove the restrictions placed on the Ahmadi minority. She could not remove the sharia laws put forward by Zia’s regime, nor the blasphemy law which hurts the minorities in Pakistan even today. She was also not able to do much to improve women’s condition in Pakistan, despite promises to repeal the Hudood ordinance which treats women as second class citizens. This ordinance contained provisions like the flogging of both the man and his woman rape victim, and treating a woman’s legal evidence with only half of the value of a man.

Despite the negatives she did receive international acclaim as a forceful spokesperson for Pakistan, and projected abroad a somewhat liberal face of the country. She was ideologically left of the center. Her most important positive legacy was perhaps her strident opposition to the military rule of Zia-al-Huq and Pervez Musharraf. This opposition led to her imprisonment or house arrest several times and the assassination of her father and two brothers. Her decision to return to face elections was a significant effort to strengthen the democratic forces in Pakistan. The decision proved to be fatal as it took her life, but if a democratic system consolidates and the military refrains from coups in the future, she could be claimed as one of the key leaders who made that possible.

T.V. Paul is James McGill Professor of International Relations at McGill University, Canada and the author of The Warrior State: Pakistan in the Contemporary World.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Benazir Bhutto’s mixed legacy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesQ&A with T.V. Paul on the 25th anniversary of Benazir Bhutto’s electionBill Bratton on both coastsSpeaking of India…

Related StoriesQ&A with T.V. Paul on the 25th anniversary of Benazir Bhutto’s electionBill Bratton on both coastsSpeaking of India…

Buddhism and biology: a not-so-odd couple

Science and religion don’t generally get along very well, from the Catholic Church’s denunciation of the heliocentric solar system to vigorous denials — mostly from fundamentalist Protestantism this time — of evolution by natural selection. Add to this Kipling’s claim that “East is east and west is west, and never the twain shall meet,” and one might expect that an Eastern religion (any Eastern religion), would be especially incompatible with science. But one would be wrong.

In fact, there already exists a lively literature regarding the supposed parallels and convergences between Eastern religions (especially Hinduism and Buddhism) and physics, including such book-length treatments as The Tao of Physics, and The Dancing Wu-Li Masters. I have no objection to these efforts at concordance, except that they omit the most dramatic and potentially enriching correspondence of all: between Buddhism and biology.

Buddhism’s appeal in the West has thus far mostly involved its promise of increased inner serenity, derived primarily from mindful meditation, to which can be added a developing strain of “socially engaged Buddhism,” as reflected in the political activism of the Dalai Lama, Aung San Suu Kyi of Burma/Myanmar, and the beloved Vietnamese scholar/monk Thich Nhat Hanh, along with numerous Western activists such as Joanna Macy and the late Robert Aitken. It turns out that in addition, Buddhism and biology have much to say to each other. In part, this might be because Buddhism can be considered as much a philosophy and intellectual perspective as a traditional religion. That is certainly the nature of my own Buddhist “practice,” which has little patience for those aspects of Buddhism that resemble standard religions: belief in various supernatural deities, worship of relics or statues, taking fairy tales as literal truth. But wipe away the mystical nonsense and abracadabra, and we find that many of the foundational ideas of Buddhism converge with newly revealed, empirically-based insights of biology, especially the disciplines of ecology, evolution, genetics, and development.

Perfume Pagoda, Vietnam

Take, for example, the Buddhism concept of anatman, which is often translated as “not-self.” This notion, seemingly so perplexing to the Western mind, actually speaks directly to modern biology, insofar as anatman does not mean that individuals don’t exist, but rather, that they aren’t composed of a solid, unchanging, internal core that is fundamentally distinct from its surroundings. Thus, when the Dalai Lama flies – by airplane, not on a magical Buddhist broomstick – from northern India to the US in order to attend a public symposium, he purchases a ticket in his name, and places his altogether corporeal body in a seat. By anatman, Buddhists mean that no one is a fixed, internal “one,” separate from his or her surroundings. This recognition is especially important to ecologists, who understand that every organism is inextricably tied to its environment, so that it is meaningless to study, for example, North American bison in isolation from their prairie habitat, or to separate a heron from its marsh. For a “master” of physiological ecology, the skin of an animal doesn’t wall it off from its surroundings so much as it joins the two. Ditto for a Buddhist master.

By the same token, neurobiologists know that there is no tiny controlling homunculus or “little green man” residing somewhere inside our brain and constituting each “self.” Instead of being analogous to a peach or avocado, which contains a hard, internal core, our bodies as well as our minds are continuous with rather than walled off from the rest of our central nervous systems and indeed, from the outside world. Getting to our fundamental selves is more like peeling an onion: after removing layer after layer, there is literally nothing left … nothing, that is, distinct from the “nothing” that constitutes the surrounding atmosphere while all this peeling has been going on.

The relationship between genes and bodies, as understood by modern evolutionary biology as well as developmental genetics, conveys a similar lesson. Thus, as emphasized by Richard Dawkins in his book, The Selfish Gene, bodies – although certainly real – are not the primary focus of evolution. Bodies come and go, deriving their temporary existence from appropriate conglomerations of various molecules and atoms scavenged from the Earth’s atomic and subatomic trash heap. Genes, on the other hand, have at least the potential of being immortal (although in reality, they also change via mutation, if our perspective is sufficiently expanded over time). Our bodies, our “selves,” in any event, are 100% composed of what Thich Nhat Hanh calls “non-self elements,” literally indistinguishable from those same elements that constitute plants, rocks, soil, and other animals as well as people that have come before us and will continue after us.

“We are but whirlpools in a river of ever-flowing water,” wrote Norbert Wiener, founder of cybernetics and one of the great mathematicians of the 20th century. Wiener went on: “We are not stuff that abides, but patterns that perpetuate themselves.” On this, Buddhists and biologists agree.

David P. Barash has been an evolutionary biologist as well as a devotee of Buddhist thought for more than 40 years; he is professor of psychology at the University of Washington, and author of more than 200 peer-reviewed scientific research articles as well as 34 books, including Buddhist Biology: Ancient Eastern Wisdom Meets Modern Western Science.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Perfume Pagoda 042 by Jack French from San Francisco, USA, Creative Commons via Wikimedia Commons

The post Buddhism and biology: a not-so-odd couple appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLogic and Buddhist metaphysicsImagination and reasonNon-belief as a moral obligation

Related StoriesLogic and Buddhist metaphysicsImagination and reasonNon-belief as a moral obligation

Let them eat theorems!

By Kenneth Falconer

“This is not maths – maths is about doing calculations, not proving theorems!” So wrote a disaffected student at the end of my recent pure maths lecture course. Theorems, along with their proofs, have gotten a bad name.

The first (and often only) theorem most people encounter is Pythagoras Theorem, discovered over 2500 years ago; that if you square the lengths of the two perpendicular sides of a right-angled triangle and add these numbers together then you get the square of the length of the third side. To many, the name Pythagoras conjures up memories of eccentric maths teachers enthusing over spiders webs of lines. Yet, if the writer of the software underlying your computer had not known their Pythagoras and other such theorems, you would not now be viewing this neatly aligned text or navigating around your screen at the touch of a mouse.

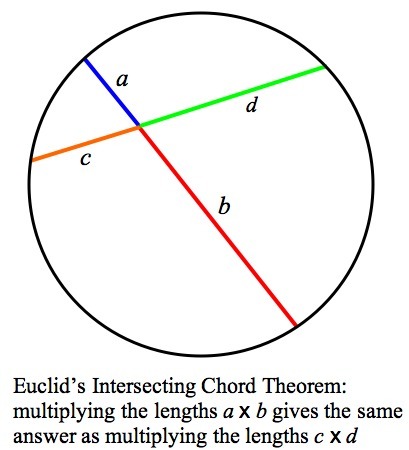

A theorem is the name for an incontrovertible mathematical fact, a statement that is an unavoidable consequence of precisely defined terms or facts that have already been established. Pythagoras’ Theorem follows inexorably from the notions of a straight line, a right-angle and length. A couple of hundred years later, Euclid formulated his theorems or ‘Propositions’ of geometry which became the foundation of western mathematical education for the next 2000 years. My favourite is the Intersecting Chord Theorem: if you draw two intersecting straight lines across a circle and multiply together the lengths of the parts of the chords on either side of the intersection point then you get the same answer for both chords (see diagram). This is a remarkable statement: there seems no obvious reason why it should be so. Yet it is an inevitable consequence of the definition of a circle. Sadly, learning the formal propositions of Euclid by rote, as they were often taught in the past, may have hidden their substance and elegance and turned off many budding mathematicians.

Many further geometrical theorems have been established since Euclid’s days, some with evocative names. The Ham Sandwich Theorem says that given three objects there is always a plane that simultaneously divides each object into two parts of equal volume; thus a sandwich can always be divided by a straight slice so that the bread, butter, and ham are all equally divided between the two portions. Then, according to the Hairy Ball Theorem, it is impossible to comb a sphere covered with hair or fur in such a way that the hairs lie down smoothly everywhere on the sphere. One consequence, perhaps reassuring at times of extreme weather, is that at any instant there is somewhere on the earth’s surface where there is no wind.

The Mandelbrot set has become an icon recognised by many with little or no mathematical knowledge but who have been fascinated by its intriguing beauty. The Fundamental Theorem of the Mandelbrot Set, as it is sometimes called, relates geometrical aspects of this extraordinarily complicated object to the simple formula z2 + c. The theorem was contained in the writings of Pierre Fatou and Gaston Julia back in 1919, but was virtually forgotten until in the mid-1970s Mandelbrot’s computer images revealed the set’s intricate detail. A picture can bring a theorem to life!

At the edge of the Mandelbrot set – complicated yet determined by a simple equation

Of course, not all theorems are about geometry. Some concern properties of numbers; perhaps the most famous is Fermat’s Last Theorem, that the equation xn + yn = zn has no solutions with x, y, z and n positive whole numbers with n greater than 2. This elegant statement was enunciated by Pierre de Fermat in 1637, but was only proved conclusively by Andrew Wiles less than 20 years ago, with a proof running to well over a hundred pages that only a very few professional mathematicians are in a position to understand. I am not aware of any practical applications of Fermat’s Last Theorem outside pure maths. On the other hand, Fermat’s Little Theorem, proposed in 1640, is a valuable tool for calculation. For example, it tells us immediately that the enormous number obtained by multiplying 2013 by itself 3000 times (written 20133000 and having almost 10,000 digits), leaves a remainder of 2013 when divided by 3001. Fermat’s Little Theorem can be proved in a few lines but has hugely important consequences, indeed it underpins many of the cryptographic methods that are used to keep computer and bank data secure.

Theorems are the pillars of mathematics. New theorems, often building on the foundations of earlier ones, are continually being proved. Yes, some may be esoteric, but others have been fundamental in the development of things that we take for granted, such as Stokes’ Theorem for electronic communication and fluid flow. And, though I obviously failed to convince my student, they are the basis for many of the calculations undertaken daily by scientists and engineers.

Kenneth Falconer is author of Fractals: A Very Short Introduction and Fractal Geometry: Mathematical Foundations and Applications (Wiley, 2014). He has been Professor of Pure Mathematics at the University of St Andrews since 1993.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only mathematics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: 1) Figure drawn by author; 2) Image computed by Ben Falconer

The post Let them eat theorems! appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA year in Very Short Introductions: 2013Logic and Buddhist metaphysicsMandela, icon

Related StoriesA year in Very Short Introductions: 2013Logic and Buddhist metaphysicsMandela, icon

December 26, 2013

The Erie Canal: a tour

Before Bill and Hilary, DeWitt Clinton was one of the most famous Clintons that New York could lay claim to. His legacy, mocked at the time as “DeWitt’s ditch”, is the famous Erie Canal. Connecting New York City to the Great Lakes through Lake Erie, this notable trade route cost seven million dollars and cut the expense of shipping to the Midwest significantly. The path to the canal was not always easy though, as explained in this passage from Evan Cornog’s The Birth of Empire:

A final argument was the role the canal could play in moderating sectionalism, although the sectionalism Clinton had in mind was not between North and South but rather between Atlantic America and the trans-Appalachian country… the future would indeed show, well after DeWitt Clinton was gone, that opening the way west would not only make any East-West sectional rupture unlikely but would firmly bind these states of the Midwest to New York City and other commercial centers of the Northeast, with significant consequences for the Civil War.

The memorial [to petition for the canal] was Clinton’s work, and it made the canal Clinton’s project. The part he took would ultimately bring him considerable distinction, though in the short term it hurt the canal. With Daniel Tompkin’s in the governor’s chair, and James Madison in the White House, Clinton—and with him the canal—had powerful enemies. New York City’s Martling Men were discovering a new and highly effective form of leadership in state politics under the hand of Martin Van Buren. While Clinton and his allies were successful in arousing public enthusiasm for the canal, the political situation in Albany remained less favorable. Tompkins knew that any canal plan would reflect favorably on Clinton; but he also knew that the canal was becoming very popular. Moreover, if Tompkins supported the Ontario route, he would lose support in the west. He did what he could to dodge the dilemma. “It will rest with the Legislature,” he said in his annual address to that body, “whether the prospect of connecting the waters of the Hudson with those of the western lakes and of Champlain is not sufficiently important to demand the appropriation of some part of the revenues of the State to its accomplishment, without imposing too great a burden upon our constitution.” There were also, apart from Tompkins’s waffling and the reluctance of Clinton’s enemies to hand him a victory, some sections of the state that still saw the canal as a threat to their interests…

By the following year, the way was clear for the passage of an act authorizing work on the canal to begin. Daniel Tompkins had been elected vice president and resigned the governorship to take up his duties in Washington. Clinton’s advocacy of the canal had revived his political fortunes and he was soon to win election as Tompkins’s successor.

Clearly, Clinton won his battle and was sworn in as governor of New York in July of 1817 despite the challenges up against him. He was able to oversee the construction of the canal, which opened on this day, 26 December, in 1825. The lore is that Clinton carried two barrels of water from Lake Erie with him on a ride down to the New York and dumped them in the harbor, not touching land in between. But now that you know the history behind the Erie Canal, it’s only fair if you see it!

I’m from that way, but the fun stuff to see is in the other direction.

On a mini-Thanksgiving road trip, I started about 19 miles west from the most notable pivot point, Albany, with a long way to the other end in Buffalo. The canal as a whole runs 524 miles (843 km) between these two points, linking up with the Hudson to run south to the ocean.

Lucky number 7.

Tricked you by pointing the wrong way- I went west instead to Lock 7. I spent a few moments standing on top of the doors and looking at the dam on the Mohawk River, adjacent to it. The lock is here because the boats can’t handle the drop of the rapids.

To the right of the station, you can see if the small falls on the Mohawk next to the comparably quiet water of the lock.

The longest man-made waterway in North America, the Erie Canal has 36 locks to handle the varying heights along the route. While it runs along part of the river, the boats can travel smoothly on the varying terrain by moving in the locks and letting the water rise or drop to bring them to the proper elevation. Lock 7 has a 27 foot height difference.

With water almost to the top of the doors, you can see why the locks are so vital.

In its heyday, the canal was the main form of cargo transportation and lead to a boom of towns in central and western New York, many of which are still the largest centers in New York today. With some twentieth century reconstruction, the canal’s life has been sustained. The canal now draws more recreational traffic, both on the water and in its surrounding parks and annual festivals.

Kate Pais joined Oxford University Press in April 2013. She works as a marketing assistant for the history, religion and theology, and bibles lists.

Evan Cornog was educated at Harvard and Columbia, and has taught American history at Columbia, LaGuardia Community College (CUNY), and Lafayette College. He also worked as Press Secretary for former Mayor Edward I. Koch of New York City. Currently, he is Associate Dean of the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University. He is the author of The Birth of Empire: DeWitt Clinton and the American Experience, 1769-1828.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: All photos by Kate Pais and Jason Brennan, used with permission, 2013.

The post The Erie Canal: a tour appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBill Bratton on both coastsLooking for clues about OUP Canada in an early photographExploring the seven principles of Kwanzaa: a playlist

Related StoriesBill Bratton on both coastsLooking for clues about OUP Canada in an early photographExploring the seven principles of Kwanzaa: a playlist

Exploring the seven principles of Kwanzaa: a playlist

Beginning the 26th of December, a globe-spanning group of millions of people of African descent will celebrate Kwanzaa, the seven-day festival of communitarian values created by scholar Maulana Karenga in 1966. The name of the festival is adapted from a Swahili phrase that refers to “the first fruits,” and is meant to recall ancient African harvest celebrations. Karenga drew upon traditional African philosophy to select the seven organizing principles (the Nguzo Saba) that structure the observance of Kwanzaa: umoja (unity), kujichagulia (self-determination), ujima (collective work and responsibility), ujamaa (cooperative economics), nia (purpose), kuumba (creativity), and imani (faith). Each day of Kwanzaa celebrates one of these principles, chosen for their emphasis on strengthening bonds of family, culture, and community among people of African descent.

In anticipation of Kwanzaa, the editors of Oxford Music Online and the Oxford African American Studies Center have put together a short playlist that celebrates the festival’s seven principles. Although these songs are not specifically tied to the Nguzo Saba, we feel that each piece embodies an important aspect of its corresponding principle. We could, of course, expand the list with hundreds of other tracks that are equally pertinent to the philosophy underpinning Kwanzaa. This selection is merely a starting point.

“Happy Kwanzaa”—Teddy Pendergrass (2001)

Our first pick, Teddy Pendergrass’s “Happy Kwanzaa,” provides an overview of the principles of the festival, and is one of the few Kwanzaa-specific songs ever produced by a major recording artist. The track is a smooth, buoyant R&B jam that not only lists the seven Nguzo Saba, but also expresses the joy to be found in celebrating them.

Click here to view the embedded video.

“Nation Time (Part 1)”—Joe McPhee (1971)

Joe McPhee’s funky free jazz classic “Nation Time” shares a title with a 1970 Amiri Baraka poem and captures the spirit of umoja (unity) that undergirded Baraka’s dream of black nationalism. (See below for more on Baraka.) In the early years of the Black Power movement, “nation time” referred to an ideal of African American political and economic cooperation that would result in a new black nation.

McPhee’s composition, recorded live at Vassar College, begins with a short call-and-response between the saxophonist and the audience: “What time is it? NATION TIME!” The band then launches into a fast-paced, densely-layered 18-minute piece that manages to showcase saxophone, piano, trumpet, bass, and organ, evoking Coltrane, soul jazz, early funk, and R&B in equal measure. However, the genius of the arrangement lies in the way in which all of these disparate elements are held together—unified—in an engaging, melodic fashion.

Click here to view the embedded video.

“Ain’t Got No, I Got Life”—Nina Simone (1968)

Nina Simone’s “Ain’t Got No, I Got Life” is the perfect embodiment of the principle of kujichagulia (self-determination). The song is divided into two parts, the first part using a minor-inflected groove to underlay lyrics written from the perspective of someone who has nothing in the way of family, love, or possessions. After a brief bridge in which the energy builds and the lyrics ask “why am I alive anyway?”, the second part begins, using a major-inflected groove to underlay a triumphant enumeration of what the person does have: arms, legs, ears, freedom—but, most importantly, life.

Click here to view the embedded video.

“What’s Happening Brother”—Marvin Gaye (1971)

Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Happening Brother” asks questions central to the principle of ujima (collective work and responsibility) within the context of someone (purportedly Gaye’s younger brother Frankie) returning home from the Vietnam War. The music itself is full of chromatic twists and turns, slickly navigating the central key and its related modes, as the song’s protagonist finds his way back into home life.

Click here to view the embedded video.

“Say it Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud”—James Brown (1968)

The principle of ujamaa (cooperative economics) is perhaps not one that lends itself easily to expression in music, but it probably wouldn’t find a clearer statement than in James Brown’s anthemic “Say it Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud.” The entire second verse of the song addresses systemic economic exploitation (“But all the work I did was for the other man”) and a solution that entails both personal agency and economic cooperation: “Now we demand a chance to do things for ourselves/We’re tired of beating our head against the wall/And working for someone else.” There’s definitely more to this song than its eminently-shoutable chorus.

Click here to view the embedded video.

“The World Is Yours”—Nas (1994)

Nas’s seminal “The World Is Yours” finds him rapping about the demands and tragedies of urban life in New York City, seemingly a million miles away from the fundamental Kwanzaa principle of nia (purpose). But while Nas doesn’t seem to hold out much hope for himself (“Born alone, die alone, no crew to keep my crown or throne”), he envisions a future in which his as-yet-unborn son will learn from his father’s mistakes and make the world his own. “My strength, my son, the star, will be my resurrection,” Nas says, confident in the knowledge that his son will find a purpose that will uplift them both. Pete Rock’s chorus (“It’s mine, it’s mine, it’s mine/Whose world is this?”) on the track is unforgettable, too, keeping nothing back in promising the world to those who endeavor to take it.

Click here to view the embedded video.

“Black Art”—Amiri Baraka (1965)

Amiri Baraka’s poem “Black Art” addresses the principle of kuumba (creativity) directly, but rather than engage with traditional ideas of beauty or aesthetics, the piece focuses, at least initially, on art’s ability to upset and destroy. In one of the poem’s early stanzas, for example, Baraka declares with a shout, “We want ‘poems that kill.’/Assassin poems, Poems that shoot/Guns.” The poem is a raw expression of outrage, full of anger and violence, that can be painful to listen to today.

“Black Art” ends, however, with a burst of positivity:

Let Black people understand/that they are[...]/

[P]oems & poets &/all the loveliness here in the world/

We want a black poem. And a/black world.

This coda comes across as an unexpected, inspirational call to unity. Nevertheless, the social implications of Baraka’s “black poem,” as delineated in the piece’s vicious early verses, have the potential to leave the listener severely troubled.

In this recording, Baraka speaks over an improvised track performed by an all-star avant-garde jazz band that included Sunny Murray on drums, Don Cherry on trumpet, and Albert Ayler on tenor sax. Ayler’s staccato bursts and Murray’s cymbal washes fill the spaces that surround Baraka’s words to create a thick, disorienting sonic cloud that amplifies the tension generated by the poem.

Click here to view the embedded video.

“Keep Ya Head Up”–Tupac (1993)

The seventh principle of Kwanzaa is imani (faith), which encourages African Americans to believe in the righteousness of the struggle for equality. Tupac Shakur’s “Keep Ya Head Up” is an anthem to strength and resilience in the face of devastating tragedies in life—but the title of the song keeps returning: no matter how impossible it seems, you have to keep fighting for what’s right.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Kwanzaa playlist

Tim Allen is an Assistant Editor for the Oxford African American Studies Center. You can follow him on Twitter @timDallen. Meghann Wilhoite is an Assistant Editor at Grove Music/Oxford Music Online, music blogger, and organist. Follow her on Twitter at @megwilhoite. Read her previous blog posts on Sibelius, the pipe organ, John Zorn, West Side Story, and other subjects.

The Oxford African American Studies Center combines the authority of carefully edited reference works with sophisticated technology to create the most comprehensive collection of scholarship available online to focus on the lives and events which have shaped African American and African history and culture.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Exploring the seven principles of Kwanzaa: a playlist appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSir John Tavener, saintly and controversial composerAn interview with marimbist Kai StensgaardOxford Music in 2013: A look back

Related StoriesSir John Tavener, saintly and controversial composerAn interview with marimbist Kai StensgaardOxford Music in 2013: A look back

Looking for clues about OUP Canada in an early photograph

I had the pleasure of writing the chapter about Oxford University Press’s early operations in Canada, Australia and New Zealand for volume three of the new History of Oxford University Press. A photo editor added an early photograph of the first home to the Canadian branch as the cover image for my chapter. It is a photograph I have seen before, but to be honest, I had previously not looked at it very closely. One thing that did catch my eye was the lack of a date for the image. Neither the current photo editor, nor any of the writers and editors who included the same image in the booklet produced for the 100th anniversary of the Canadian branch in 2004, were able to concretely identify when the photograph was taken. I am hoping that some of the readers of this blog will be able to help. Perhaps someone with more knowledge about Canadian automobiles would be able to provide some help?

We do have quite a bit of information about the building that is useful and a close look at the picture offers several additional clues. We know, for example, that the first office opened at 25 Richmond Street West in Toronto on 10 August 1904, so the photograph must be from after 1904. The signage to the right of the entrance provides another bookend date. The sign reads “Doubleday Page & Co.” In 1927 Doubleday Page merged with the George H. Doran Company and took the name Doubleday Moran, so the photograph is almost certainly from before 1927. Lack of fire damage narrows it a bit further, as a fire burned through this building on 20 October 1927, gutting the top floor and forcing the branch to move out — finally settling into Amen House on University Avenue in 1929.

Some of the other signage on the building is also useful. Notably the building carries “Clarendon Building” on its cornice, pushing the earliest date to 1905. When the branch initially opened, it took over an existing lease in the building that was then owned by a Mr. Gowler. Less than a month later, the owner was offered twice as much rent by another prospective tenant and it appeared that the branch would have to find a new home when its lease expired in June 1906. The Press responded by purchasing the entire building, closing on the deal on 2 January 1905. It would have been after that date that the Press added its name to the building and put up what appear to be OUP seals on the second story windows.

Another photograph included in the 100th anniversary booklet produced by OUP Canada in 2004 offers one further clue that suggests the picture is from after 1913. That picture, taken from a slightly different angle, shows a street sign directly in front of the building that reads “Henry Frowde – Oxford Bibles.” Frowde, of course, was the Publisher to the University and the man behind the opening of branches in New York in 1896, Toronto in 1904, and Melbourne in 1908. That sign, however, is not present in this image, perhaps because it was taken after his retirement from the Press in 1913.

My own guess is that the photograph is from much closer to 1927 than 1913, but if anyone has other insights, I’d be eager to hear them.

Thorin Tritter taught history and American studies for six years at Princeton University. He has directed the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History’s History Scholars program since its inception in 2003 and currently is the managing director of the Fellowships at Auschwitz for the Study of Professional Ethics.

With access to extensive archives, The History of Oxford University Press is the first complete scholarly history of the Press, detailing its organization, publications, trade, and international development. Read previous blog posts about the history of Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only North American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image courtesy of the Oxford University Press Archive. Do not reproduce without prior written permission.

The post Looking for clues about OUP Canada in an early photograph appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBill Bratton on both coastsRobert Morison’s Plantarum historiae universalis OxoniensisTranslation and subjectivity: the classical model

Related StoriesBill Bratton on both coastsRobert Morison’s Plantarum historiae universalis OxoniensisTranslation and subjectivity: the classical model

“This strange fête”, an extract from The Lost Domain

Alain-Fournier’s lyrical novel, The Lost Domain, captures the painful transition from adolescence to adulthood without sentimentality, and with heart-wrenching yearning. Romantic and fantastical, it is the story’s ultimate truthfulness about human experience that has captivated readers for a hundred years. The following is an extract from chapter 15 and describes the moment when Meaulnes sees Yvonne de Galais for the first time.

Roaming through the garden, he came upon the fishpond and peered over the rickety fence which surrounded it. The pool was still edged with ice, thin and lacy like foam. He caught sight of himself in the water, as if he were bending over the sky. And in the figure dressed in the clothes of a romantic student he saw another Meaulnes: not the collegian who had made off in a farmer’s carriole, but a charming and fabulous creature out of a book, a book one might receive as a prize…

For some time he strolled along the shore over a sandy stretch that resembled a towpath, stopping here and there to stare up at tall dusty windows through which apartments in a state of dilapidation could be dimly seen, or lumber-rooms cluttered up with wheelbarrows, rusty tools, and broken flowerpots, when all at once he heard footsteps on the sand.

It was two women, one old and bent, the other young, fair, and slender. Her inconspicuous clothes, simple but charming, after all the fancy costumes of the night before, struck him at first as extraordinary.

They paused for a moment to look about them and Meaulnes, in a hasty conclusion that later seemed to him wildly wide of the mark, told himself:

‘Probably one of those girls they call eccentric — perhaps an actress they’ve got here for the fête.’

Meanwhile the two women passed close to him, and he stood watching the girl. Often afterwards, when he had gone to sleep after trying desperately to recapture that beautiful image, he saw in his dreams a procession of young women who resembled her. One wore a hat like hers; one leaned slightly forward as she did; one had her innocent expression, another her slim waist, another her blue eyes — but not one of them was this tall slender girl. He had time to notice a head of luxuriant fair hair and a face with small features so delicate as to be almost over-sensitive. Then she was moving away from him and he noticed the clothes she was wearing which were as simple and modest as garments could possibly be…

Irresolute, wondering whether he dare accompany them, he heard the girl say to her companion, as she turned slightly towards him:

‘The boat ought to be here at any moment now…’

And Meaulnes followed them. The old lady, though feeble and shaky, did most of the talking which she sprinkled with laughter, the girl making gentle replies. And the same gentleness was in the look, innocent and serious, which she turned on him as the two women walked down towards a landing-stage: a look which seemed to say:

‘Who are you? How do you happen to be here? I don’t know you… And yet I do seem to know you.’

Other guests were now standing about under the trees. Then three pleasure-boats came alongside to take on the passengers. One by one young men doffed their hats and young ladies bowed at the approach of the two women, who seemed to be the lady of the château and her daughter. It was all very strange — the morning itself, the excursion… In spite of the sun there was a chill in the air and the women drew more tightly about their throats the feather boas which were then in fashion…

The old lady stayed behind on the shore, and without knowing how it happened, Meaulnes found himself on board the same little vessel as the young lady of the house. He leaned against a rail, one hand protecting his hat from the high wind, unable to take his eyes from the girl, who had found a seat in a sheltered part of the deck. She looked at him too. She would answer the remarks of her neighbours with a smile, then her blue eyes would rest on him gently. He noticed that she had a habit of biting her lip.

In deep silence they drew away from the shore. Nothing could be heard but the purr of the engine and the wash from the bows. It might have been a morning of midsummer. They might have been bound for some country estate where this girl would saunter under a white sunshade, doves cooing through the long afternoon… But an icy gust of wind brought a sharp reminder of December to the people taking part in this strange fête.

Alain-Fournier was the pseudonym of Henri Alban-Fournier, whose only novel, Le Grand Meaulnes (The Lost Domain) was published the year before he was killed in action in 1914, at the age of 27. Like the narrator of his novel, Alain-Fournier was the son of a schoolteacher, and a chance meeting with a girl on the banks of the Seine became the rite of passage that inspired his story.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Alain Fournier as a child. Public domain via WikiCommons.

The post “This strange fête”, an extract from The Lost Domain appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesChristmas quotations from Oxford World’s ClassicsTranslation and subjectivity: the classical modelMonthly gleanings for December 2013

Related StoriesChristmas quotations from Oxford World’s ClassicsTranslation and subjectivity: the classical modelMonthly gleanings for December 2013

December 25, 2013

Monthly gleanings for December 2013

At the end of December people are overwhelmed by calendar feelings: one more year has merged with history, and its successor promises new joys and woes (but thinking of future woes is bad taste). I usually keep multifarious scraps and cuttings to dispose of on the last Wednesday of the year: insoluble questions come and never go away (why, for example, we say this time of year rather than of the year, or things are coming to an end, if there is only one end, and surely it must be the end?). Anyway, that time of year, my friend, thou mayst in me behold when 2013 is coming to an end. I have a few old and a few new things to discuss. The sheen of novelty and the glitter of rime (few people still recognize the word rime) are equally attractive to an etymologist. Also, one can always repeat the same thing, pretending that it is new. Recently, I have read two articles in Washington Post. One informed the public that American English can be divided into 24 zones; the other picked up an old hat and discovered Californian “uptalk” (known as Valley Girl talk). I wish I could lay hands on equally stunning revelations. So let me begin with an ancient theme.

One of our correspondents asked me when I threw the gauntlet to those who use they in speaking about a single person. I think the first time I did it was in a post “The Tenant’s Dilemma,” dated 8 October 2008. The post irritated some of my colleagues who asserted that such constructions go back to at least Middle English and alleged the existence of solid research on the subject. But I knew that all the research amounted to their reading an entry in Fowler’s Modern English Usage. There the celebrated author quotes sentences with they referring to someone, anyone, and other indefinite pronouns. I insisted that horrors like when a tenant is evicted, it is not always their fault owe their origin to a misguided effort to avoid sexism in language and that the cure was worse than the disease. Not unexpectedly (or unsurprisingly, as some authors like to say), my opponents did not find sentences of this type in older sources, though indeed I received (not from them!) two excerpts going back to the end of the nineteenth century in which a patient was called they in a medical record.

The discussion died a natural death (all of us said what we could, though I may add that in stylistically respectable newspapers and in well-written books this ultramodern English usage never occurs), but from time to time I quoted in the gleanings the silliest examples that came my way. I have two such at the moment. They illustrate the degree the stultification of American speakers has reached. People are simply afraid to say he or she. The situation is as follows. Burglars and rapists have become truly fearless around the campus where I teach. To avoid a misunderstanding: all the criminals are male, while the victims of rape are female. From a sheriff’s testimony: “Basically, the modus operandi was the same. He approaches a victim, identifies himself as a police officer, kidnaps them, sexually assaults them and releases them.” From a letter to the student newspaper: “One of my friends said she was able to run away from an alleged mugger by using pepper spray when they threatened her with a gun.” The incidents are horrifying, but isn’t the grammar pathetic? I agree with John Cowan that at present after none both is and are sound correct, but this is an entirely different matter. The same holds for neither he nor she is/are interested in this question. I am not so naïve as to expect that people will stop using the form beaten into them at school, but it does not follow that, when ugliness becomes the norm, everybody is expected to admire it.

Garfish and its spurious kin.

Mr. John Larsson cited Swedish dialectal görgott “very good” and asked whether gör- was related to gar- in garfish (in the fish name, gar- means “spear”). No, this gör- is a descendant of Old Norse gørr ~ gerr), a comparative form meaning “more fully, more precisely” or simply “better.” Since ø is the umlaut of o, rather than an original front vowel, g in Swedish gör- is pronounced “hard.”

Monkey.

Have I answered our correspondent who asked me whether anyone had noticed that the word monkey sounds very much like Malay monyet and others? Yes, the similarity is well-known. See my post for 23 January 2013.

Twerk.

I know that I thanked our correspondent for a comment on my discussion of twerk, but I am amused to observe the attention this word has received. My colleagues already “twerk” letters in the words they explain, the Internet is awash with questions and answers about the origin of twerk, and the whole world and his wife twerk in unison. The noun is old, the verb surfaced about twenty years ago, and the spellchecker in my computer has no knowledge of either. But then people always invent something new and ask ingenious questions, for example: “Does a diner have to serve dinner?” This is indeed the question of the year. Also, can a monkey monkey a monkey? I am sure it can.

New words.

Peter Maher has recently sent me a list of new words compiled by Paul B. Gallagher, who found them in the Russian version of Esquire, with definitions in Russian and an English translation, apparently by a Russian. Mr. Gallagher polished up the translations, so that they read like English. Some entries are amusing.

Seagull management “a management style where the manager suddenly swoops down on an organization, makes a lot of noise, disrupts everything, and then, just as suddenly, takes off, leaving total chaos in his wake” (sounds familiar—the thing, not the phrase).

“Seagull” management.

(Sex in and outside the city). Slide to unlock “a very easy girl” (I have once read an extremely sober book titled Male Fantasies, but this idiom is not there). Girlfriend zone “the situation when a girl wants to stay friends, but a guy only sees her romantically.”

Child supervision “when tech-savvy kids help elderly parents or other relatives with computers or other electronic devices.” Ah, the joys of child supervision! I remember seeing the word blog for the first time. I asked everybody around about its meaning. No one knew. Only my undergraduate assistant, and not a very bright one, explained to me the word’s meaning and origin. And I am supposed to be an expert in etymology… My last self-effacing sentence was added to illustrate the compound humblebrag “a statement whose boastfulness the author tries to disguise with irony or a joke such as who am I, anyway?”

A Happy New Year from The Oxford Etymologist and his (their?) editors!

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: A posed photograph of Anton Chekhov reading his play The Seagull to the Moscow Art Theatre company. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Monthly gleanings for December 2013 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEtymology gleanings for November 2013Gray matter, part 2, or, going to the dogs againGray matter, or many more shades of grey/gray, part 1

Related StoriesEtymology gleanings for November 2013Gray matter, part 2, or, going to the dogs againGray matter, or many more shades of grey/gray, part 1

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers