Oxford University Press's Blog, page 858

January 3, 2014

The many meanings of the Haitian declaration of independence

Two hundred and ten years ago, on 1 January 1804, Haiti formally declared its independence from France at the end of a bitter war against forces sent by Napoléon Bonaparte. This was only the second time, after the United States in 1776, that an American colony had declared independence, so the event called for pomp and circumstance. Haiti’s generals, led by Jean-Jacques Dessalines, gathered in the western city of Gonaïves, where they listened to a public reading of the Declaration by the mixed-race secretary Louis Boisrond-Tonnerre. A handwritten original has yet to be found, but early imprints and manuscript copies have survived.

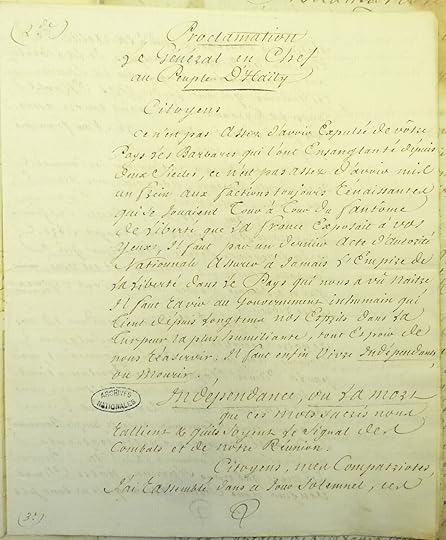

Early manuscript copy of the Haitian declaration of independence. Photograph by (c) Philippe Girard.

The declaration is well known to Haitians, who celebrate its passage every year on 1 January, Haiti’s national holiday. They mostly remember it for its fiery defiance. According the Haitian historian Thomas Madiou, its author Boisrond-Tonnerre got the assignment after promising Dessalines that he would use “the skin of a white man” as parchment, its “skull” as inkwell, and its “blood” as ink. “What do we have in common with this people of executioners [the French]?” he asked in the Declaration. “They are not our brothers, and never will be.”

But the Declaration, which historians are just beginning to study in depth, was actually a layered text whose multiple meanings were tailored for six different audiences: the French, Creoles, Anglo-Americans, Latin Americans, mixed-race Haitians, and black Haitians.

The main intended audience, arguably, was not Haitian but French. The Declaration was not written in Kreyòl, Haiti’s main language, but in very formal French. Many of the people present on 1 January 1804, for whom French was a second or third language, probably struggled to understand its elaborate style, but the French government did not. The very first paragraph explained that Haitians, had gathered for “an act of national authority,” pledged “to live independent or die,” and would destroy any French invading force. They meant it.

The Citadelle, built after 1804 by Henry Christophe, was meant to deter a French invasion. Photograph by (c) Philippe Girard.

The Declaration also addressed the French Creoles still living in Haiti, who had committed unspeakable atrocities in previous years. “Avenge” their victims, Boisrond-Tonnerre urged his listeners, by punishing these “assassins and disgusting tigers.” In ensuing weeks, in a most controversial act, Dessalines personally supervised the massacre of most of Haiti’s white planters, then decreed that all the citizens of Haiti would henceforth be generically known as “blacks”.

But the Declaration had a gentler message for Haiti’s neighbors, Jamaica and the United States in particular. To those who feared that the Haitian Revolution would soon export itself, the Declaration promised “peace to our neighbors…. May [they] live in peace under the aegis of the laws they made for themselves.” Despite all the fears of the American plantocracy, Haiti indeed refrained from encouraging slave revolts outside Hispaniola in ensuing years.

To the many colonies still remaining in Latin America, the Declaration depicted Haiti as the symbol of the continent’s emancipation from European imperialism. Once known by the Spanish name of Santo Domingo, the colony was renamed “Haiti,” a word borrowed from the native Amerindians of the Caribbean. Similarly, Dessalines referred to his soldiers as the “indigenous army” and, more fancifully, “the army of the Incas.” “I avenged America,” he also explained in a 28 April proclamation. The Declaration, in a sense, was Haiti’s Monroe Doctrine.

The Declaration also had something to say to the Haitians who, like Boisrond-Tonnerre, were of mixed-race descent. Would they, as the sons and grandsons of white Creoles, be killed as well? No; in fact, Dessalines even hoped that a joint massacre of the whites would cement racial unity in Haiti. “Blacks and yellows [mulattoes],” he concluded after the massacres, “you now form a single family.”

Le serment des ancêtres. This 1822 painting by the Guadeloupean painter Guillaume Guillon Lethière, representing Alexandre Pétion and Jean-Jacques Dessalines, was housed in Haiti’s presidential palace until it was damaged during the 2010 earthquake. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Last but not least, the Declaration had something to say to the vast majority of the people present on 1 January 1804: the black rank-and-file. Dessalines, a former slave, unambiguously confirmed their emancipation from bondage: “we dared to be free.” But the term “liberty,” which appeared repeatedly in the text, only meant “independence” and “abolition,” not “democracy.” The Declaration did not include a bill of rights and was enacted unilaterally by generals who months later declared Dessalines as their emperor. Eighteen hundred and four marked the end of colonial-era enslavement but also, unfortunately, Year One of Haitian militarism and authoritarianism.

How successful was Haiti’s declaration of independence in the long term? Some goals have eluded Haiti’s Founding Fathers: racial unity remains a work in progress in a country still divided by the color line and Haiti’s reputation in the Americas remains poor despite Dessalines’s reassurances to his neighbors. Formal slavery, on the other hand, disappeared for good (though forms of bondage like the restavek system have endured). The Declaration’s primary purpose, independence, was achieved: Haiti did gain its independence, which was belatedly recognized by France in 1825 (and the United States in 1862). Later centuries were less kind: Haiti had to endure two US invasions in 1915 and 1994, and Haiti is now in many ways a dominion of the United Nations and international NGOs that is in dire need of a second declaration of independence.

Philippe Girard, a native of Guadeloupe in the French Caribbean, is a Professor of History at McNeese State University in Lake Charles, Louisiana. He is the author of many books and articles on the history of Haiti, including the upcoming French- and English-language The Memoir of Touissant Louverture.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The many meanings of the Haitian declaration of independence appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat was inside the first Canadian branch building?Q&A with Claire Payton on Haiti, spirituality, and oral historyI spy, you spy

Related StoriesWhat was inside the first Canadian branch building?Q&A with Claire Payton on Haiti, spirituality, and oral historyI spy, you spy

Everybody has a story: the role of storytelling in therapy

When was the last time you told or heard a good story? Was it happy, sad, or funny? Was it meaningful? What message did the story convey? People have been telling stories throughout history. They tell stories to teach lessons, to share messages, and to motivate others. Some stories are happy, while some stories are sad.

I come from a long line of imaginative storytellers who inherited family lore and legend through the art of storytelling. Because of stories, I know of family misfortune and secrets, and have learned from elders’ indiscretions. Because of stories I have learned of my mother’s joy and despair when hearing of her childhood memories, at age nine frolicking in Wick Park with her younger brother, while simultaneously coping with her mother dying from terminal cancer. Perhaps most importantly, I learned the importance of the resilience of the human spirit. Storytelling can be helpful, even therapeutic, for those experiencing difficult experiences or transitions in their lives.

I come from a long line of imaginative storytellers who inherited family lore and legend through the art of storytelling. Because of stories, I know of family misfortune and secrets, and have learned from elders’ indiscretions. Because of stories I have learned of my mother’s joy and despair when hearing of her childhood memories, at age nine frolicking in Wick Park with her younger brother, while simultaneously coping with her mother dying from terminal cancer. Perhaps most importantly, I learned the importance of the resilience of the human spirit. Storytelling can be helpful, even therapeutic, for those experiencing difficult experiences or transitions in their lives.

Currently, I counsel children, adolescents, and adults about social and personal issues confronting them. I also teach about human behavior, disability, and family issues at the university level. An important aspect of both positions is lending voice to peoples’ stories. I hear and process life stories – some joyous and some tragic. I listen to peoples’ stories about adjusting to disabling conditions, living with memories of abuse or assault, grieving for the loss of loved ones, and learning how to cope with what hand life has dealt them. Everyone has a story to tell, and everyone deserves a chance to tell his or her story.

Storytelling is a vital component of the assessment and intervention process. Strengths-based storytelling can be used in a therapeutic way. Adolescents, young adults, and children can engage with thought provoking vignettes. In turn, many identify with the characters, which often leads to increased self-disclosure in the therapeutic process, especially for those individuals who have difficulty directly expressing themselves verbally.

Through storytelling, many people gain insight that leads to behavioral change, and improvements in the quality of their lives. Stories may be told through writing, through art, through photos, or verbally. There is more than one way to tell a story.

I hope you will reflect on stories you have heard, stories you have told, and how these stories have influenced your life, your work, and the lives of those you touch. Consider the stories you tell, and think about how applying storytelling in your life communicates knowledge, messages, beliefs, and values. If it feels right, share a story with your friends, your family, your students, or your clients today.

Johanna Slivinske is co-author of, Therapeutic Storytelling for Adolescents and Young Adults (2014). She currently works at PsyCare and also teaches in the Department of Social Work at Youngstown State University, where she is also affiliated faculty for the Department of Women’s Studies.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only social work articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Public art – Mary Durack storyteller, Burswood, Perth by Moondyne, Creative Commons via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Everybody has a story: the role of storytelling in therapy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA conversation with Dr. Andrea Farbman on music therapyMusic therapy research and evidence-based practiceThe evolution of music therapy research

Related StoriesA conversation with Dr. Andrea Farbman on music therapyMusic therapy research and evidence-based practiceThe evolution of music therapy research

Globalization: Q&A with Manfred Steger

How has globalization changed in the last ten years? We asked Manfred Steger, author of Globalization: A Very Short Introduction, how he felt it has been affected by world events in the decade since the first edition of his Very Short Introduction was published.

The VSI is now in its third edition. What have been the most important/significant changes in globalization since the first edition in 2003?

The most important change to the third edition is the addition of a substantive chapter on the ‘ecological dimensions of globalization’, which discusses global climate change and the global impact of major environmental disasters such as the destruction of the Fukushima nuclear reactor in the wake of the 2011 earthquake, and the 2010 BP gulf oil spill. Also the chapter on the ‘ideological dimensions of globalization’ has been further developed and expanded. It now introduces three different types of ‘globalisms’. Finally, the opening chapter explains the basic concepts of globalization in the context of the 2010 Football World Cup in South Africa. Of course, all the other chapters have been updated and revised to engage current issues.

Airman looks for trapped survivors March 16, 2011, after 2011 earthquake in Japan

Social networking has become a large part of everyday life for many people. How has this changed globalization in a cultural context?

Social networking has intensified cultural globalization by increasing cultural flows across the world. Some experts argue that the global standardization of the Facebook or Twitter templates have increased cultural tendencies of homogenization (or ‘Americanization’), whereas other scholars emphasize the creation and proliferation of new (sub-cultures) as a result of social networking. My own perspective is that social networking also contributes to cultural ‘hybridization’–the mixing up of different cultural values, styles, and preferences resulting in new cultural expressions that blur the line between ‘Western’ and ‘non-Western’ cultural formations.

How do you see the state of globalization in 5 years’ time?

Unless there is another major global crisis that surpasses the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, I believe that globalization dynamics will further intensify. With the ICT revolution still in full swing, we can expect in five year’s time the emergence of new communication devices that are not even imaginable today. But I am not particularly enthusiastic about the intensifying digitalization of social relationships. The dark side of this dynamic is the decline of face-to-face interactions and physical contact–two basic human qualities that foster a strong sense of community among people.

How would you respond to claims that globalization is ideological?

As I point out in my book, globalization always has ideological dimensions. There is no such thing as a neutral, unbiased perspective on something as multi-faceted and contentious as globalization. At the moment the three main ideological forces employ different types of ‘globalisms’–ideologies centered on globalization–to convince their global audiences of the superiority of their respective political and social views. I call these ideologies ‘market globalism’ (neoliberalism), ‘justice globalism’ and ‘religious globalism’. The neoliberal worldview is still the strongest, but has come under attack, especially in the wake of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.

In economic terms, can globalization benefit all, or will it only benefit high earners?

It depends what form of globalization we are talking about. Market-led globalization, for example, claims that, in the long run, globalization–understood as the liberalization and global integration of markets–will benefit all. But a recent major study undertaken by Branko Milanovic, the leading economist at the World Bank, shows that the bottom 5% of the world population have not benefitted at all in more than 2 decades of market-led globalization. Of course, there have also been improvements in global South countries like China and India, but the economic benefits have disproportionately gone to those at top income bracket. I think it is important to develop more ethical forms of globalization aimed at reducing the growing inequality gap within and among nations. Fortunately, more world leaders have become aware of the rising tide of social and economic inequality. Pope Francis, for example, recently issue a powerful encyclical that warns us of the dangers of growing worldwide disparities in wealth and well-being.

Do you think the subject should be covered more in schools?

I do. In universities around the world, there are currently strong efforts underway to further expand the growing transdisciplinary field of global studies, which focuses on the exploration of the many dimensions of globalization. But the basics of globalization should be taught as early as primary school and most certainly in secondary school. Unfortunately, many current lesson plans require serious updating to engage the major global issues (and problems) of our global age.

Has the financial crisis paused the progress of globalization?

As I noted in my response to questions 3 and 4, the momentum of market globalism was slowed down in response to the economic crash of 2008 and the ensuing Great Recession. But those market globalist ideas of the ‘Roaring 1990s’ and 2000s are still tremendously influential–as we can see in ongoing attempts by neoliberal governments around the world to cut taxes, restrict spending, deregulate the economy, and privatize the few remaining public industries.

Are there any environmental costs of globalization?

The environmental costs to market-led globalization have been been horrific. That is why the 3rd edition of my VSI contains such a substantive chapter on this topic. I believe that the deteriorating ecological health of our planet will become the most pressing global problem by mid-century at the latest. We simply can no longer afford business-as-usual. The problem is not just global warming, but various forms of transboundary pollution (such as the staggering amount of trash and plastics that find their way into our our planet’s soil and oceans) and the rapid decline of biodiversity. And if we don’t switch from fossil fuels to alternative forms of clean energy any time soon, we will reach our ecological point of no return.

What is most exciting/innovative research going on in global studies at the moment?

Political geographers and urban studies scholars have been contributing highly innovative approaches to the study of globalization. Their emphasis on theorizing space is a much needed corrective to the conceptual frameworks of those of us who have been trained to focus primarily on the role of language, ideas, and economics in evolution of human societies. Obviously, the compression of space and time is at the heart of globalization, so it behooves us to pay closer attention to the current reconfigurations of spatial arrangements, especially in the context of our expanding ‘global cities’ and the loss of areas of wilderness.

If you weren’t a political science academic, what would you be?

I am fascinated by the history and culture of ancient Rome, so perhaps I would be a classicist or a historian of the Roman Empire. Or, even better, a bestselling author of historical novels!

Manfred B. Steger is Professor of Political Science at the University of Hawai’i-Manoa and Professor of Global Studies at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT University). He is also the Research Leader of the Globalization and Culture Program in RMIT’s Global Cities Research Institute. He has served as an academic consultant on globalization for the US State Department and as an advisor to the PBS TV series, ‘Heaven on Earth: The Rise and Fall of Socialism’. He is the author or editor of twenty-one books on globalization and the history of political ideas, including the third edition of Globalization: A Very Short Introduction.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: By Harvey McDaniel [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons; By Staff Sgt. Samuel Morse [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Globalization: Q&A with Manfred Steger appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesI spy, you spyWhat to do at ASSA 2014Let them eat theorems!

Related StoriesI spy, you spyWhat to do at ASSA 2014Let them eat theorems!

January 2, 2014

Eponymous Instrument Makers

The 6th of November is Saxophone Day, a.k.a. the birthday of Adolphe Sax, which inspired us to think about instruments that take their name in some way from their inventors (sidenote: for the correct use of eponymous see this informative diatribe in the New York Times).

Adolphe Sax (1814-1894)

Belgian inventor of the saxophone.

Fun fact: Despite its common association with, and prolific use in jazz music, the saxophone, patented in 1846, was originally intended for use in orchestras and concert bands. Par exemple, Debussy’s Rapsodie for orchestra and saxophone:

Click here to view the embedded video.

John Philip Sousa (1854-1932)

American inventor of the sousaphone, a brass instrument related to the tuba and widely used in marching bands.

Fun fact: Sousa wrote dozens of marches, including “Semper Fidelis”, which you can hear in the opening sequence of A Few Good Men, the “Minnesota March”, which John Morris altered ever so slightly for the opening theme of Coach, and “Liberty Bell”, which served as the opening theme for Monty Python’s Flying Circus (shout-out to Oxford alumni Terry Jones and Michael Palin!).

Léon Theremin (1896-1993)

Lev Termen, known also as Léon Theremin, Russian inventor of the theremin.

Not-so-fun-fact: In the late 1930s Termen was imprisoned by a predecessor of the KGB and forced to work in a secret Gulag laboratory; upon his release he became a spy for the KGB and then later as a professor at the Moscow Conservatory.

A sub-category of eponymous instrument makers includes those whose inventive take rendered their names forever associated with certain already well-established instruments:

Antonio Stradivari (1644-1737)

Italian luthier who created the famed Stradivarius line of string instruments.

Fun fact: The film The Red Violin took its inspiration from one of Stradivari’s instruments (still in existence), called the Red Mendelssohn. Bonus: In Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s books, Sherlock Holmes plays a Strad—though we doubt Benedict Cumberbatch is playing one in the BBC series!

Leo Fender (1909-1991)

American inventor of various Fender guitars and amplifiers.

Fun fact: The guitar that Jimi Hendrix set on fire in Monterey in 1967? Well, we’re not sure what type of guitar that was, but the one he was playing right before swapping it out for the fire-bound one was his favorite black Fender Stratocaster.

Robert Moog (1934-2005)

American inventor of the moog analog synthesizer.

Fun fact: Moog paid for his university studies by building and marketing theremins. Bonus: The Moog synthesizer was first demonstrated for music industry professionals at the same festival where Hendrix lit his guitar on fire.

Did we miss any? Share your additions to this list in the comments!

A version of this article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Meghann Wilhoite is an Assistant Editor at Grove Music/Oxford Music Online, music blogger, and organist. Follow her on Twitter at @megwilhoite. Read her previous blog posts on Sibelius, the pipe organ, John Zorn, West Side Story, and other subjects.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Eponymous Instrument Makers appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesExploring the seven principles of Kwanzaa: a playlistSir John Tavener, saintly and controversial composerAn interview with marimbist Kai Stensgaard

Related StoriesExploring the seven principles of Kwanzaa: a playlistSir John Tavener, saintly and controversial composerAn interview with marimbist Kai Stensgaard

What was inside the first Canadian branch building?

I wrote before about the picture that serves as the cover for the chapter on Canada, Australia, and New Zealand in Volume 3 of the newly published History of Oxford University Press. I personally enjoy looking at this type of picture and trying to imagine what went on inside. In the case of this building, we do have another photograph, published in a booklet produced on the 100th anniversary of the Canadian Branch in 2004, which captures the showroom on the ground floor of this building. Perhaps not surprisingly, tables covered with books fill most of the room, with bookcases lining the walls. One other document adds a bit more detail to the picture. Early in the morning on Wednesday, 27 December 1905, a fire broke out in the building. Nobody was hurt in the fire, but there was extensive damage to the offices. Luckily for the Press, the branch had secured fire insurance, and in the detailed claim they submitted we can find a bit more about what was inside the building.

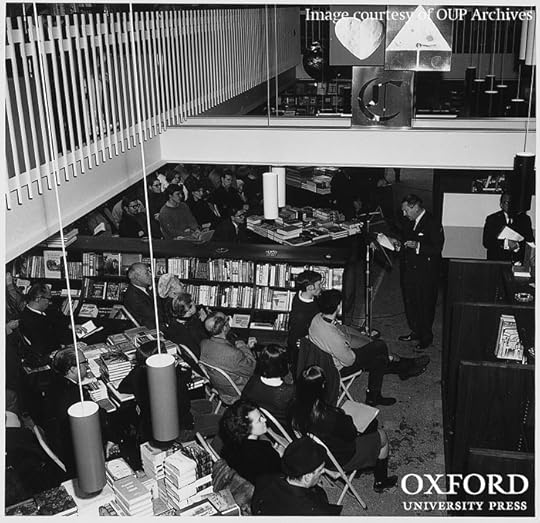

Poetry Reading at OUP Canada. From Volume 3 of the History of Oxford University Press. Image courtesy of OUP Archives. Do not reproduce without permission.

Not surprisingly, by far the most valuable items on the first floor were more than $46,000 (Canadian) worth of books. Fifteen tables, six desks, two counters, and a showcase are also listed, much as you would expect in a showroom. More interesting to me are the smaller items. The rug in S.B. Gundy’s office — the branch manager — was valued at $49.76, almost equal to two oak desks valued at $50. Electric light fixtures accounted for a bit more money ($60), but the claim also included a hat rack ($2.85) and rubber stamps ($8.25). One typewriter desk ($50) and one typewriter copy stand ($3.50) are also included, although apparently the typewriter survived the fire. Two other items, one expensive and one relatively small, struck me. The single most expensive item of furniture is “1 Iron Safe, paint scorched.” Nothing is mentioned of what was in the safe, or if that survived, but at $128.00 this was a notable item in the office. Finally a claim for $7.45 for “Card Index Cabinet” might seem relatively insignificant, but in a pre-computer world where data was kept on index cards, I have no doubt that each card — recording customer information or book orders — was a highly valuable item to the business. Overall, nothing on the list is surprising, but all the items remind us that bookselling in the early 20th century was all about paper and wood — both highly flammable.

Thorin Tritter taught history and American studies for six years at Princeton University. He has directed the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History’s History Scholars program since its inception in 2003 and currently is the managing director of the Fellowships at Auschwitz for the Study of Professional Ethics.

With access to extensive archives, The History of Oxford University Press is the first complete scholarly history of the Press, detailing its organization, publications, trade, and international development. Read previous blog posts about the history of Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only North American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image courtesy of the Oxford University Press Archive. Do not reproduce without prior written permission.

The post What was inside the first Canadian branch building? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLooking for clues about OUP Canada in an early photographI spy, you spyRobert Morison’s Plantarum historiae universalis Oxoniensis

Related StoriesLooking for clues about OUP Canada in an early photographI spy, you spyRobert Morison’s Plantarum historiae universalis Oxoniensis

I spy, you spy

Jonathan Freedland wonders, “Why Surveillance Doesn’t Faze Britain”? Comparing his fellow British subjects to Americans, he finds them “curiously complacent” about their civil liberties when it comes to the massive invasions of privacy implied by Edward Snowden’s revelations of the US National Security Agency’s “big data” scoops of information from digital communication sources. Ultimately, Freedland chalks this up to the two countries’ different political histories. The United States has a written constitution and Bill of Rights, the United Kingdom doesn’t. Brits are still subjects of Her Majesty’s Government, whereas Americans are citizens under their own governance, “of the people, by the people, for the people”—as recent celebrations of the 150th anniversary of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address have reminded us.

But Freedland must feel his admiration compromised by the latest news from the surveillance front, that “United States Can Spy on Britons Despite Pact, N.S.A. Memo Says”. Our Bill of Rights protects us (Americans), but apparently not our closest traditional allies, the “Five Eyes” countries—U.S., Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand—who have long had (since World War II) a gentlemen’s agreement, as well as official protocols, against spying on each other. Sic transit “special relationship.”

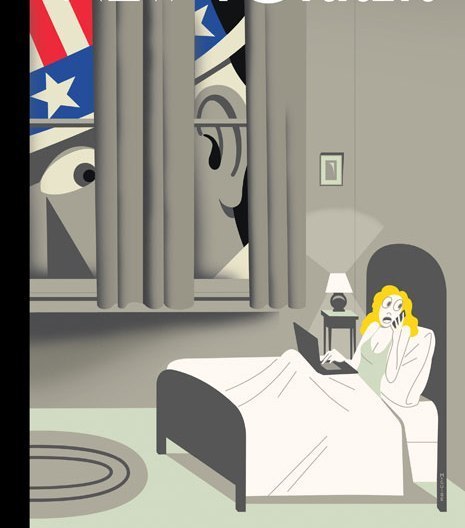

Uncle Sam is Watching You © Richard McGuire. Used with the artist’s permission.

Yet all of these agreements, formal or informal, have always had provisos for special circumstances, reserving the right to spy on each other, in the words of Glanz, “when it is in the best interest of each nation.” Security trumps freedom, when push comes to shove. Or, to put it another way, the closer one is to the hidden violence which is the ultimate justification for all this spying, the less one is disposed to worry about the civil rights of their perpetrators. I am a liberal Democrat, but I felt as murderously vengeful as anyone when I learned that a friend was in an Underground train immediately behind one of those blown up by terrorists in London on 7/7. To say nothing of 9/11.

Our shared histories of civil rights—and violations thereof—illustrate this too, making it hard for Americans to bask too comfortably in the light such admiration as Freedland’s. (Not to speak lightly of it: the Guardian columnist is one of the most astute British admirers of the virtues of American republicanism. His 1998 book, Bring Home the Revolution, can be read as profitably by Americans who take their liberties for granted as by Britons who don’t know what they’re missing.)

But looking back over our shared yet divided histories we find depressingly regular episodes when both countries have signally failed to live up to their highest ideals.

The American Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 were manifestly unconstitutional, but were forced into law by President John Adams and his fellow Federalists, terrified that something like the French Reign of Terror would make headway in the United States if various kinds of “suspicious” persons—and ideas—were not stopped at the border. Terror begets terror.

Also in the 1790s, the government of William Pitt the Younger, long hailed as “the Pilot who brought us through” England’s wars against republican (not Napoleonic) France, passed many laws that suspended the supposedly hallowed right of habeas corpus from the Magna Carta. These were laws against British subjects, motivated by fear of the same Terror which scared Adams, and which motivates the mutually reinforcing, if mutually regretted, violations of the N.S.A. and the British G.C.H.Q. (Government Communications Headquarters). Foremost among these was the Royal Proclamation of May, 1792, in which George III urged his loyal subjects to report any suspicious words or behavior they observed among their neighbors to the Home Office for vetting. This was “See something? Say something!” with a vengeance. It did not rely on sophisticated spy satellites or complicated internet piracy, but it worked very well: there were more trials for sedition and treason in Great Britain between 1792 and 1798 than ever before or after in its history—over one hundred, the government winning convictions in a healthy two-thirds of them (State Trials, ed. Howells and Cobbett, 1809-1826).

Kenneth R. Johnston is the author of Unusual Suspects: Pitt’s Reign of Alarm and the Lost Generation of the 1790s. He received his PhD from Yale University and spent his entire academic career at Indiana University, where he was honored for distinguished teaching and scholarly achievement, while also heading its Department of English. He is also author of Wordsworth and ‘The Recluse’ and The Hidden Wordsworth: Poet, Lover, Rebel, Spy, and editor of Romantic Revolutions. The Hidden Wordsworth won the 1999 Barricelli Prize for outstanding contribution to Romantic studies, and was named to several Book of the Year lists in both United Kingdom and United States. Read his previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Richard McGuire, ‘Uncle Sam is Watching You’, The New Yorker, June 24, 2013. © Richard McGuire. Used with the artist’s permission.

The post I spy, you spy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBill Bratton on both coastsPreparing for AALS 2014Benazir Bhutto’s mixed legacy

Related StoriesBill Bratton on both coastsPreparing for AALS 2014Benazir Bhutto’s mixed legacy

January 1, 2014

Gray matter, part 3, or, going from dogs to cats and ghosts

The shades of gray multiply (as promised in December 2013). Now that we know that greyhounds are not gray, we have to look at our other character, grimalkin. What bothers me is not so much the cat’s color or the witch’s disposition as the unsatisfactory state of etymology. Stephen Goranson has been able to collect sixty opinions about the origin of the word that he studied (see his comment to my recent post on the dialect of Craven). I cannot boast of such numbers. Although my database contains close to a hundred items pertaining to the derivation of god, they do not contain so many solutions: only three or four hypotheses have been recycled again and again. The same holds for numerous other words that have been at the center of attention for centuries. With regard to grimalkin, two reasonable conjectures compete. One has been sanctified by the best dictionaries and repeated everywhere; the other is never mentioned. Such an attitude harms research. Obviously, if everything is clear about the history of a word, no one will return to it, but even a hint of uncertainty, if noticed and taken into account, may result in a new attempt to solve the riddle. It is exactly such a hint that I would like to drop.

Here are the names of the scholars who will figure below. Robert Nares (1753-1829), a distinguished philologist; his work on obscure words in Shakespeare has lost none of its value. Lazar Sainéan (1859-1934; this is a Frenchified variant of the Romanian name, which itself is a variant of his original Jewish name), one of the most ingenious researchers of Romanian and French folklore and linguistics, a man whose studies of French argot and of the native origin of French are among the most important contributions to the subject. Leo Spitzer (1887-1960), an Austrian-born comparative linguist and literary scholar, talented and very prolific (in the United States from 1936 to his death). He was a life-long admirer of Sainéan’s. Both Sainéan and he offered multiple interesting etymologies. Although some of them should be treated with caution, they are always interesting and thought provoking. Paul Barbier (1873-1947), about whom I, unfortunately, know nothing, except that he was a professor of Romance philology at the University of Leeds (1903-1938). I have learned a lot from his articles and would be grateful to those of our readers who may write something about him in a comment and for Wikipedia.

Nares defined grimalkin as “a fiend, supposed to resemble a grey cat.” Skeat said that Nares was probably right. The OED agreed with Nares and Skeat, and so did Charles Scott, the etymology editor of The Century Dictionary and the author of several detailed essays on devilry. But Sainéan, Spitzer (who seems to have known English as well as French and Spanish, to say nothing of his native German, long before he came to America), and Barbier thought differently. Barbier missed the works of his predecessors and reinvented their etymology independently of them. According to Sainéan and especially Spitzer, grimal- is an English adaptation of the French demon Grimaut or Grimaud-, already known from texts in 1561 (and, consequently, having been current for some time before that). If such is the derivation of Grimalkin, its structure is Grimal-kin, with -kin being a diminutive suffix, rather than Gri-malkin. In Part 1 of this series, I noted that outside English the color name gray ~ grey had merged with a word meaning “frightening, terrible.” But since in English gruesome did not become greysome (unlike what happened in German: grau and grausam), an association with grim- may have arisen: Grim-Malkin made perfect sense. Grey Malkin is more remote from Grimalkin. I am not ready to endorse Sainéan’s derivation, but it is not worse than Nares’s, and, as I said at the beginning of this post, my aim consists only in shattering the belief that the origin of Grimalkin needs no further discussion. Scott observed that the English demon Malkin had been attested in Shakespeare’s lifetime; also, in an old ballad Grey Maulkin appears. Perhaps it was abstracted from Grimalkin and understood as a diminutive of Maud or some other feminine name. As long as Malkin meant “cat,” gray fit it perfectly. The question remains open. I would be happy if I succeeded in unclosing it. (Is it possible that Grimalkin was “a word of the year” and that Shakespeare made use of popular slang?)

Nares defined grimalkin as “a fiend, supposed to resemble a grey cat.” Skeat said that Nares was probably right. The OED agreed with Nares and Skeat, and so did Charles Scott, the etymology editor of The Century Dictionary and the author of several detailed essays on devilry. But Sainéan, Spitzer (who seems to have known English as well as French and Spanish, to say nothing of his native German, long before he came to America), and Barbier thought differently. Barbier missed the works of his predecessors and reinvented their etymology independently of them. According to Sainéan and especially Spitzer, grimal- is an English adaptation of the French demon Grimaut or Grimaud-, already known from texts in 1561 (and, consequently, having been current for some time before that). If such is the derivation of Grimalkin, its structure is Grimal-kin, with -kin being a diminutive suffix, rather than Gri-malkin. In Part 1 of this series, I noted that outside English the color name gray ~ grey had merged with a word meaning “frightening, terrible.” But since in English gruesome did not become greysome (unlike what happened in German: grau and grausam), an association with grim- may have arisen: Grim-Malkin made perfect sense. Grey Malkin is more remote from Grimalkin. I am not ready to endorse Sainéan’s derivation, but it is not worse than Nares’s, and, as I said at the beginning of this post, my aim consists only in shattering the belief that the origin of Grimalkin needs no further discussion. Scott observed that the English demon Malkin had been attested in Shakespeare’s lifetime; also, in an old ballad Grey Maulkin appears. Perhaps it was abstracted from Grimalkin and understood as a diminutive of Maud or some other feminine name. As long as Malkin meant “cat,” gray fit it perfectly. The question remains open. I would be happy if I succeeded in unclosing it. (Is it possible that Grimalkin was “a word of the year” and that Shakespeare made use of popular slang?)

Our last demon for today is the gremlin. The noun has been around only since 1941 and is one of the war words that stayed and made a spectacular career. Still later (1970) the car called “Gremlin” was introduced. I have no idea why it was given such a mischievous name and whether it lived up to it. John Moore, in an article published in The Observer for November 8, 1942, discussed the folklore of gremlins and suggested that the sprite had come out of Fremlin beer bottles. This amusing explanation has been recycled by several authors, among others by Joseph T. Shipley, the least reliable etymologist among those whose books have been published by the otherwise dependable presses. The rhyme fremlin / kremlin / gremlin is obvious, but, regrettably, that is where we should stop, for we have no evidence that the word, which sprang up among British aviators, owes anything to its look-alikes. A more certain clue is the suffix, for it may have been borrowed from goblin.

Spitzer said in passing that gremlin had the same origin as grimalkin. Other scholars traced this word to an Old English or a rare Dutch verb. Such attempts should be rejected out of hand. If it is true that gremlin had not been heard of before 1941, in what limbo did it vegetate for centuries? It does happen that a word sometimes leads a hidden life in the language of the underworld, escapes from its environment, stops being slang, and enters aristocratic parlors. Gremlin does not seem to be one of such words. The suggestion that the etymon of gremlin is Irish Gaelic gruamin “ill-humored little fellow” is acceptable, but, as ill luck would have it, we don’t know whether the originator of the word was an Irishman or someone fluent in Irish Gaelic. Also, in the life of a word, its history following the moment of “conception” is of no small importance. How did gremlin gain such popularity? Why among pilots? Genies occasionally come out of the bottle; gremlins probably don’t. The origin of gremlin remains unknown, but a respectable imp should have a name beginning with gr-. Otherwise, who will be afraid of it?

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Britishblue, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Gray matter, part 3, or, going from dogs to cats and ghosts appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGray matter, or many more shades of grey/gray, part 1Monthly gleanings for December 2013Gray matter, part 2, or, going to the dogs again

Related StoriesGray matter, or many more shades of grey/gray, part 1Monthly gleanings for December 2013Gray matter, part 2, or, going to the dogs again

Gray matter, part 3, or, going from dogs to cats and ghosts (grimalkins and gremlins)

The shades of gray multiply (as promised in December 2013). Now that we know that greyhounds are not gray, we have to look at our other character, grimalkin. What bothers me is not so much the cat’s color or the witch’s disposition as the unsatisfactory state of etymology. Stephen Goranson has been able to collect sixty opinions about the origin of the word that he studied (see his comment to my recent post on the dialect of Craven). I cannot boast of such numbers. Although my database contains close to a hundred items pertaining to the derivation of god, they do not contain so many solutions: only three or four hypotheses have been recycled again and again. The same holds for numerous other words that have been at the center of attention for centuries. With regard to grimalkin, two reasonable conjectures compete. One has been sanctified by the best dictionaries and repeated everywhere; the other is never mentioned. Such an attitude harms research. Obviously, if everything is clear about the history of a word, no one will return to it, but even a hint of uncertainty, if noticed and taken into account, may result in a new attempt to solve the riddle. It is exactly such a hint that I would like to drop.

Here are the names of the scholars who will figure below. Robert Nares (1753-1829), a distinguished philologist; his work on obscure words in Shakespeare has lost none of its value. Lazar Sainéan (1859-1934; this is a Frenchified variant of the Romanian name, which itself is a variant of his original Jewish name), one of the most ingenious researchers of Romanian and French folklore and linguistics, a man whose studies of French argot and of the native origin of French are among the most important contributions to the subject. Leo Spitzer (1887-1960), an Austrian-born comparative linguist and literary scholar, talented and very prolific (in the United States from 1936 to his death). He was a life-long admirer of Sainéan’s. Both Sainéan and he offered multiple interesting etymologies. Although some of them should be treated with caution, they are always interesting and thought provoking. Paul Barbier (1873-1947), about whom I, unfortunately, know nothing, except that he was a professor of Romance philology at the University of Leeds (1903-1938). I have learned a lot from his articles and would be grateful to those of our readers who may write something about him in a comment and for Wikipedia.

Nares defined grimalkin as “a fiend, supposed to resemble a grey cat.” Skeat said that Nares was probably right. The OED agreed with Nares and Skeat, and so did Charles Scott, the etymology editor of The Century Dictionary and the author of several detailed essays on devilry. But Sainéan, Spitzer (who seems to have known English as well as French and Spanish, to say nothing of his native German, long before he came to America), and Barbier thought differently. Barbier missed the works of his predecessors and reinvented their etymology independently of them. According to Sainéan and especially Spitzer, grimal- is an English adaptation of the French demon Grimaut or Grimaud-, already known from texts in 1561 (and, consequently, having been current for some time before that). If such is the derivation of Grimalkin, its structure is Grimal-kin, with -kin being a diminutive suffix, rather than Gri-malkin. In Part 1 of this series, I noted that outside English the color name gray ~ grey had merged with a word meaning “frightening, terrible.” But since in English gruesome did not become greysome (unlike what happened in German: grau and grausam), an association with grim- may have arisen: Grim-Malkin made perfect sense. Grey Malkin is more remote from Grimalkin. I am not ready to endorse Sainéan’s derivation, but it is not worse than Nares’s, and, as I said at the beginning of this post, my aim consists only in shattering the belief that the origin of Grimalkin needs no further discussion. Scott observed that the English demon Malkin had been attested in Shakespeare’s lifetime; also, in an old ballad Grey Maulkin appears. Perhaps it was abstracted from Grimalkin and understood as a diminutive of Maud or some other feminine name. As long as Malkin meant “cat,” gray fit it perfectly. The question remains open. I would be happy if I succeeded in unclosing it. (Is it possible that Grimalkin was “a word of the year” and that Shakespeare made use of popular slang?)

Nares defined grimalkin as “a fiend, supposed to resemble a grey cat.” Skeat said that Nares was probably right. The OED agreed with Nares and Skeat, and so did Charles Scott, the etymology editor of The Century Dictionary and the author of several detailed essays on devilry. But Sainéan, Spitzer (who seems to have known English as well as French and Spanish, to say nothing of his native German, long before he came to America), and Barbier thought differently. Barbier missed the works of his predecessors and reinvented their etymology independently of them. According to Sainéan and especially Spitzer, grimal- is an English adaptation of the French demon Grimaut or Grimaud-, already known from texts in 1561 (and, consequently, having been current for some time before that). If such is the derivation of Grimalkin, its structure is Grimal-kin, with -kin being a diminutive suffix, rather than Gri-malkin. In Part 1 of this series, I noted that outside English the color name gray ~ grey had merged with a word meaning “frightening, terrible.” But since in English gruesome did not become greysome (unlike what happened in German: grau and grausam), an association with grim- may have arisen: Grim-Malkin made perfect sense. Grey Malkin is more remote from Grimalkin. I am not ready to endorse Sainéan’s derivation, but it is not worse than Nares’s, and, as I said at the beginning of this post, my aim consists only in shattering the belief that the origin of Grimalkin needs no further discussion. Scott observed that the English demon Malkin had been attested in Shakespeare’s lifetime; also, in an old ballad Grey Maulkin appears. Perhaps it was abstracted from Grimalkin and understood as a diminutive of Maud or some other feminine name. As long as Malkin meant “cat,” gray fit it perfectly. The question remains open. I would be happy if I succeeded in unclosing it. (Is it possible that Grimalkin was “a word of the year” and that Shakespeare made use of popular slang?)

Our last demon for today is the gremlin. The noun has been around only since 1941 and is one of the war words that stayed and made a spectacular career. Still later (1970) the car called “Gremlin” was introduced. I have no idea why it was given such a mischievous name and whether it lived up to it. John Moore, in an article published in The Observer for November 8, 1942, discussed the folklore of gremlins and suggested that the sprite had come out of Fremlin beer bottles. This amusing explanation has been recycled by several authors, among others by Joseph T. Shipley, the least reliable etymologist among those whose books have been published by the otherwise dependable presses. The rhyme fremlin / kremlin / gremlin is obvious, but, regrettably, that is where we should stop, for we have no evidence that the word, which sprang up among British aviators, owes anything to its look-alikes. A more certain clue is the suffix, for it may have been borrowed from goblin.

Spitzer said in passing that gremlin had the same origin as grimalkin. Other scholars traced this word to an Old English or a rare Dutch verb. Such attempts should be rejected out of hand. If it is true that gremlin had not been heard of before 1941, in what limbo did it vegetate for centuries? It does happen that a word sometimes leads a hidden life in the language of the underworld, escapes from its environment, stops being slang, and enters aristocratic parlors. Gremlin does not seem to be one of such words. The suggestion that the etymon of gremlin is Irish Gaelic gruamin “ill-humored little fellow” is acceptable, but, as ill luck would have it, we don’t know whether the originator of the word was an Irishman or someone fluent in Irish Gaelic. Also, in the life of a word, its history following the moment of “conception” is of no small importance. How did gremlin gain such popularity? Why among pilots? Genies occasionally come out of the bottle; gremlins probably don’t. The origin of gremlin remains unknown, but a respectable imp should have a name beginning with gr-. Otherwise, who will be afraid of it?

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Britishblue, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Gray matter, part 3, or, going from dogs to cats and ghosts (grimalkins and gremlins) appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGray matter, or many more shades of grey/gray, part 1Monthly gleanings for December 2013Gray matter, part 2, or, going to the dogs again

Related StoriesGray matter, or many more shades of grey/gray, part 1Monthly gleanings for December 2013Gray matter, part 2, or, going to the dogs again

What to do at ASSA 2014

By Carolyn Napolitano

The 2014 Allied Social Science Associations meeting will be held from 3-5 January at the Philadelphia Marriott Downtown. More than 50 associations nationwide will come together for three days of engaging lectures, thought-provoking sessions, and networking with some of the top figures in the field.

This annual conference is hosted by the American Economic Association. Originally formed in 1885 by a tight-knit group of economics enthusiasts, the AEA has since expanded exponentially and is now composed of over 18,000 academics and business professionals alike.

With over 500 sessions to choose from, the ASSA 2014 Conference has something for everyone to enjoy. Read below for suggestions tailored toward your personal interests:

Do you love social media and anything tech-savvy? Don’t forget to download the ASSA 2014 Annual Meeting App. Described by ASSA as “your Swiss Army Knife for the event,” this free app is a great way to keep track of the sessions you want to attend, network with speakers and fellow attendees, and take notes that can be easily exported to your email. You’ll be kept in the loop on anything and everything you could ever want to know about the conference, via reminders and updates directly accessible on your phone. Quick links to social media channels will also allow you to share your experience with friends and co-workers who are not in attendance and show them all the cool events that they’re missing out on!

Hungry for information about federal finance? Head over to the AEA/AFA Joint Luncheon’s “Banks as Patient Fixed-Income Investors” by Jeremy Stein. Jeremy Stein has a diverse background in economics: he’s currently a member of the Federal Reserve System’s Board of Governors, after working previously as the Moise Y. Safra Professor of Economics at Harvard and the former president of the American Finance Association. His wide-ranging experience has given him a unique perspective in regards to banking, behavioral finance, financial regulation, and corporate investment. This luncheon will be on Friday, 3 January at 12:30 p.m. in the Grand Ballroom (Salons G & H).

Is networking on your top list of priorities for the conference? You can’t miss the Professional Placement Service for Academic and Non-Academic Job Openings. Illinois Job Link has generously offered this complimentary service to be available for all conference attendees. If you are an employer looking to hire, or a job seeker who wants to meet potential employers, you should definitely check out the placement center. Trained IJL staff will be ready and eager to help you find just what you’re looking for. This four-day service will be available from 8:00 am – 5:00 pm each day in Ballroom AB of the Pennsylvania Convention Center.

Do you want to hear more about retirement security? The Richard T. Ely Lecture this year will be “Retirement Security in an Aging Population,” presented by James Poterba, the Mitsui Professor of Economics at MIT and current president of NBER. For the past two decades, Poterba has contributed a great deal of research on tax-deferred retirement saving programs and the importance of annuities in retirement planning. His insight is sure to shed light on this critical topic of much recent debate. This lecture will take place on Friday, January 3rd at 4:45pm in the Grand Ballroom (Salons G & H).

Are you curious about the relationship between the economy and gender? Be sure to check out the AEA Awards Ceremony and Presidential Address by Claudia Goldin on “A Grand Gender Convergence: The Last Chapter.” Claudia Goldin, the Henry Lee Professor of Economics at Harvard, has dedicated a substantial portion of her career to investigating the role of women in the American economy. She’s written about a wide-range of issues that have affected ambitious, career-driven women over the past century, including female access to education, the impact of birth control on family planning, and the recent increase in the female to male undergraduate ratio at select universities. Claudia’s talk will be on Saturday, January 4th at 4:40pm in the Grand Ballroom (Salons G & H).

Are you interested in learning about innovative teaching methods for your economics students? The AEA is hosting the Continuing Education Program, which will take place after the conference, from 5-7 January. There will be three sessions, each taught by distinguished scholars in the field of economics: “Cross-Section Econometrics” [Alberto Abadie (Harvard) and Joshua Angrist (MIT)], “Education and the Economy” [Susan Dynarski and Brian Jacob [both from the University of Michigan)], and “Economic Growth” [Oded Galor and David Weil (both from Brown)]. The AEA hopes that this program will “help mid-career economists and others maintain the value of their human capital.” Please note: this event requires a separate reservation and will take place at the Sheraton Philadelphia Downtown.

We hope that you enjoy the conference and look forward to seeing you at the Oxford Booths #507-511. We will be giving attendees of the conference a 20% discount on our new and bestselling titles, as well as offering sample copies of our latest economics journals and online products.

See you in Philadelphia!

Carolyn Napolitano is a Marketing Assistant for Social Sciences at Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post What to do at ASSA 2014 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy evolution wouldn’t favour Homo economicusEconomic migration may not lead to happinessYour Place of the Year

Related StoriesWhy evolution wouldn’t favour Homo economicusEconomic migration may not lead to happinessYour Place of the Year

Penal reform in the UK

In this podcast Martin Partington talks to Frances Crook, Chief Executive of the Howard League. Does penal policy in the UK operate in a more ‘punitive’ way than other European countries (including the former Eastern-bloc)? Frances makes a passionate defence of the current probation service and deplores the current Government’s approach to reform of the service.

You can listen to this podcast here:

Martin Partington CBE is Emeritus Professor of Law, Bristol University. He was Law Commissioner for five years, and has been a member of numerous committees and bodies working within the English Legal System. He is the author of Introduction to the English Legal System which is published annually. He has previously recorded a podcast with Richard Susskind.

Frances Crook OBE is the Chris Executive of the Howard League for Penal Reform. The Howard League for Penal Reform is the oldest penal reform charity in the UK. It was established in 1866 and is named after John Howard, one of the first prison reformers.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Penal reform in the UK appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesExtreme makeover: England’s new defamation lawPreparing for AALS 2014A New Year’s Eve playlist

Related StoriesExtreme makeover: England’s new defamation lawPreparing for AALS 2014A New Year’s Eve playlist

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers