Oxford University Press's Blog, page 854

January 22, 2014

Whoa, or “the road we rode”

The world has solved its gravest problems, but a few minor ones have remained. Judging by the Internet, the spelling of whoa is among them. Some people clamor for woah, which is a perversion of whoa and hence “cool”; only bores, it appears, don’t understand it. I understand the rebels but wonder. Woah looks like a garbled Hebrew name, though, on the other hand, why couldn’t there be a maiden called Woah? Quite possibly, she even existed and only escaped the annalists’ attention because she spent her childhood and youth in a cloister known as W.O.A.H. (“World’s Oldest Association for Happiness”), a precursor of YMCA. When she grew up, she found a spouse and became (“morphed into”) Whoa, because, wherever she went, she aroused great surprise. Stranger things happen in married life. I am neither a biblical scholar nor a marriage counselor; my concern is solely about the digraph oa in English. How did this combination of letters arise and why does it occur in so many words?

I will pass by cocoa and boa: both are too exotic to cause trouble. But why is the past of ride spelled rode, while the path used for riding is called road? Let us begin at the beginning. Middle English had two long o’s. One resembled aw in Modern Engl. law, paw, saw, the way those words sound in the varieties of English in which Shah and Shaw are distinguished. It went back to long a (approximately as in Modern Engl. spa) and was an open vowel, that is, during its articulation the lower jaw dropped quite a bit. Another long o continued Old English long o and was less open. In some dialects, a third o appeared, the product of short o lengthened before single consonants. It got in between the two older vowels. The space became too crowded, and multiple mergers took place. As a rule, the third o, in the few areas in which it arose, merged with its close neighbor. Still later all o’s changed under the pressure of the Great Vowel Shift.

While the two o’s coexisted, they were not confused in speech, and scribes needed different symbols for them. They introduced the digraph oa for open o: the letter a could signify the openness of o because a is the most open vowel in any language. The symbol for long close o remained the letter o. The device looks awkward, but its use can be justified. The digraph was not an invention of the English Middle period: oa had sufficient currency in Old French, and the scribes (of French descent or educated in the French tradition) followed the only model they knew. But there may have been another reason. While long a was becoming long open o, the spelling oa reflected the ongoing change or the scribes’ uncertainty (a? o?) quite well.

The roads we take

Here are some examples. The digraph oa in boat, goad, load, loan, oak, soap, and toad, among many others, designates the vowel that once was open long o (from long a). Road also belongs here. Old close long o became long u (pronounced as in Modern Engl. pooh-pooh); hence boot, doom, school, and so forth. These words will no longer interest us. As noted, short o, lengthened in Middle English, tended to merge with its close partner, and orthography did not react to lengthening: words with it were spelled with o in both Old and Middle English, changed under the influence of the Great Vowel Shift, but retained their visual image through the centuries (as, for instance, in spoke)—let us add: sometimes! After open and close long o merged, people could not know which is which, and spelling became chaotic.

Take the word mole “spot.” In Old English it had long a. This means that today we could expect moal. No such English word exists, though the omniscient Internet reminds us of Moalboal, a fourth class municipality in the province of Cebu, Philippines. Mole “animal name” had a short vowel in Old English; consequently, the spelling of its present day reflex (continuation) is regular. Opponents of Spelling Reform keep repeating that, though our spelling is hard to learn, at any rate, it preserves the venerable past of the English language. This argument makes no sense even in general terms (why should the spelling of a modern language be a faithful transcript of the past?), but, to make matters worse, spelling distorts the history of English as often as it reflects it. The case of road is characteristic. This noun and the past tense of the verb ride go back to the same base and were homonyms in Old English, namely rad (with long a). It follows that both should be spelled road. Either under the influence of forms like spoke or for some other reason, rode acquired a wrong shape. Home and bone are also “wrong”: their original forms (ham and ban, with long a) predict modern hoam and boan, like foam and groan. By contrast, soak should be spelled soke, but it is not. To restore fairness, English has a legal term soke “right of local jurisdiction,” which is spelled “correctly.”

The plot thickens when we encounter late borrowings, most often from French. Consider coat and coast. What would have happened if they were spelled coste and cote? Coste, with -e after two consonants, does not look ugly (compare haste, paste, and waste versus waist); cote (as in dovecote and sheepcote) is also fine. Moat had o lengthened before a single consonant and therefore should have been spelled mote, like mote “a speck of dust.” Here opponents of Spelling Reform tell us that homophones should be distinguished in writing. Really? Are they seriously inconvenienced by fan (for winnowing) ~ fan “admirer,” poach (as in poached eggs) ~ poach “trespass,” and dozens of others?

Some dictionaries list dote and doat and explain that dote “to be silly or weak-minded” can be distinguished from doat “to bestow excessive fondness.” Perhaps it can, but I am not sure that someone old but not yet in his (or her or better “their”) dotage will nowadays write a doating parent. The most puzzling word with oa is broad. In Old English, brad rhymed with rad (both had long a). Then, quite regularly, both changed their long a to long open o. Road went further and farther (roads usually do) and acquired a diphthong by the Great Vowel Shift, while broad stayed with its long undiphthongized o. At least two conjectures have been offered to explain this anomaly. According to one, broad, meaning what it does, was pronounced with an intonation that preserved long o intact. This is possible but rather hard to believe. The other explanation has it that broad is a northern form; in the North, vowels stayed away from many changes familiar to those who speak Standard English. But no solid evidence testifies to broad having been particularly favored in the North. Finally, I am pleased to report that there is absolutely no need to spell hoarse and hoard with oa, even though the vowel before r was open. Compare horse and porcelain. Yes, and I have almost forgotten gloat, a probable remnant of eighteenth-century slang. Wouldn’t glote satisfy us?

Read and weep, and when you have dried your tears, look up the origin of school and shoal “large number of fish” in some good dictionary.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Chile – twisting switchbacks at the border crossing. Photo by McKay Savage, 26 February 2012. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Whoa, or “the road we rode” appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFront page news: the Oxford Etymologist harrows an international brothelThe color gray in full bloomGray matter, part 3,or, going from dogs to cats and ghosts (grimalkins and gremlins)

Related StoriesFront page news: the Oxford Etymologist harrows an international brothelThe color gray in full bloomGray matter, part 3,or, going from dogs to cats and ghosts (grimalkins and gremlins)

What Kerry and Obama could learn from FDR on the environment

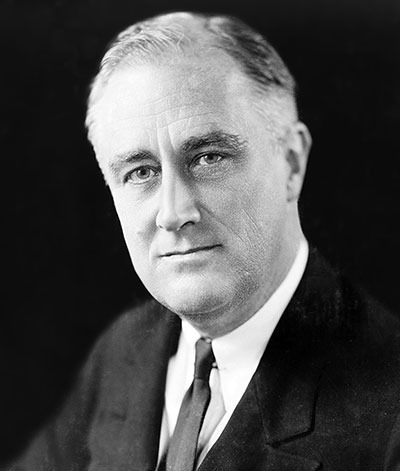

Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933, Photo by Elias Goldensky (1868-1943), Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Recent reports that Secretary of State John Kerry is pushing to create an agency-wide focus on global warming with the goal of leading the effort to obtain a new global climate change treaty are welcome, but long overdue. The scientific community has warned for years that we are on a collision course with global warming, and a recent report from the National Academy of Scientists suggests that “hard-to-predict sudden changes” in the environment due to the effects of climate change might drive the planet to a “tipping point.” Until now, the United States, still the biggest per capita polluter next to the United Arab Emirates and tiny Trinidad and Tobago, has refused to take leadership on this issue. Kerry’s decision may even be too late. Secretary Kerry and his boss would do well to learn from the leadership of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Though faced with an environmental crisis far less apocalyptic and global but nevertheless monumental for its time, Roosevelt rose to the occasion in the first 100 days of his presidency, creating the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Soil Conservation Service, and the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) and exerting a leadership and educational role on conservation that would have a profound and lasting effect on the nation’s environmental health.Most people forget that the Great Depression was not only an economic crisis, but an environmental one. By the time Roosevelt took office, the country had faced a Mississippi River flood of biblical proportions—then the most destructive river flood in the history of the United States. It would face another on the Ohio River in 1937. Seven-eighths of the country’s original forests had been decimated, and the Dust Bowl, on its way to destroying one sixth of the country’s topsoil, would generate the first great environmental refugee migration of the modern age. By the start of the Depression, the United States had experienced nearly 300 years of unchecked wildlife destruction. Large parts of the country also faced a public health crisis resulting from the twin economic and environmental crises. Malnourishment and disease—especially malaria—plagued the impoverished sections of the country, and unknown numbers died from dust pneumonia.

Dust Bowl, South Dakota, 1936. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Within a matter of weeks, the Civilian Conservation Corps had recruited, trained and sent off to work projects thousands of young, impoverished men, World War I veterans and Native Americans. These corpsmen would soon be planting billions of trees (an estimated three billion altogether), essentially reforesting the country, teaching farmers how to conserve the soil, planting thousands of acres of the Great Plains with grasses to retain moisture, and building shelter belts of drought-resistant trees to break the winds and anchor soil to prevent another Dust Bowl. Conservation corpsmen would be bringing white pine blister rust under control; eradicating tree-killing insects; fighting fires; developing sub-marginal land as wild-life refuges; building fish-rearing ponds and animal shelters; developing springs; planting food for animals and birds; constructing nesting areas; reintroducing wildlife to depleted areas; stocking streams, rivers and dams with fish; and collecting, treating, and releasing sick or injured creatures on federal refuges. Some camps were involved in wildlife research, and many more were tasked with monitoring wildlife. Some 800 national and county parks were built by the CCC, national parks were refurbished, and infrastructure was created for their recreational use.

The CCC and TVA also served to conserve the human resource base. One hundred thousand illiterate CCC corpsmen were taught to read and write. Over 25,000 received eighth-grade diplomas, over 5,000 graduated from high school, and 270 were awarded college degrees. On-the-job technical vocational education provided many graduates of the program with skills that they could turn into waged work upon completion. By the end of the program malnourished men had gained weight, muscle, and height, and achieved disease and mortality rates lower than the national average for men of their age group. Using environmentally benign methods, the TVA eradicated malaria in a seven-state region, rid the area of periodic floods saving thousands of lives, and brought electricity into the homes of millions of people. These efforts did much to develop an environmental awareness that would flower into the environmental movement of the 1960s. Though the New Deal’s environmental record was not untarnished—there were some unintended consequences resulting from the limited ecological knowledge available at the time—it is very likely that without the work of the CCC, the Soil Conservation Service and the TVA, the country would have experienced species extinction and global warming much earlier than we have.

All of this is due to the leadership of Franklin D. Roosevelt whose lifelong passion for the environment led him to take action when it was needed and not to wait for public opinion or congressional critics to come around. Recognizing the threat to the nation’s health in the loss of environmental resources, he was willing, despite a dedication to balanced budgets, to permit deficit spending to save them. A master communicator, he spoke of environmental sustainability as requisite to the security of the American people and to the liberty of the community. As early as 1912, New York State Senator Franklin D. Roosevelt in a speech in Troy, New York, challenged the common assumption both then and now that human inventiveness and technology could save us from our destructive patterns.

The opponents of Conservation who, after all, are merely opponents of the liberty of the community, will argue that even though they do exhaust all the natural resources, the inventiveness of man and the progress of civilization will supply a substitute when the crisis comes. . . . I have taken the conservation of our natural resources as the first lesson that points to the necessity for seeking community freedom, because I believe it to be the most important of all our lessons.

As president, Roosevelt used every means of communication at his disposal—speeches, radio chats, posters, the commissioning of movies, music and art–to educate the public about the need to conserve the environment and to plan for its long-term sustainability.

It is tragic that Roosevelt’s message was little heeded in the post-war rush to create a consumer society. We are now paying the terrible price for unregulated and environmentally destructive consumption. We might just have a chance if Kerry and Obama were to learn from the proactive role model of a president who, though lionized for other achievements, is underrated for his consummate environmental leadership.

Sheila D. Collins is Professor of Political Science Emerita, William Paterson University and editor/author with Gertrude Schaffner Goldberg of When Government Helped: Learning from the Success and Failures of the New Deal. She is on the speakers’ bureau of the National New Deal Preservation Association and the board of the National Jobs for All Coalition, is a member of the Global Ecological Integrity Group and co-chairs two seminars at Columbia University.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post What Kerry and Obama could learn from FDR on the environment appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBlack American political thoughtHow secure are you?Five important facts about the Italian economy

Related StoriesBlack American political thoughtHow secure are you?Five important facts about the Italian economy

Five important facts about the Italian economy

Though the Eurozone crisis left many European countries struggling in its wake, Italy suffered one of the most crippling hits to its economy. As Gianni Toniolo notes in his edited volume, The Oxford Handbook of the Italian Economy Since Unification, between 2007-2009, there was a “loss of more than 5 percentage points in GDP per person, a decline comparable with that of the Italian Great depression of the early 1930s.” But there are too many preconceptions about both the history of the Italian economy and the state it’s in today.

(1) Italy has been in debt for the greater part of its economic history.

“Italy’s history after the unification of the country in 1861 is characterized by high levels of public debt. Even excluding the exceptional years between the start of World War I and the end of World War II, nominal debt has been higher than GDP for long spells. The debt-to-GDP ratio has been above 100 percent in sixty-three years (42 percent of the time); it has exceeded 60 percent in 111 years (almost 75 percent of the time). Periods with low debt (e.g., less than 35 percent of GDP) are the exception and they are concentrated in the twenty years after the end of World War II, when Italy experienced its ‘economic miracle.’”

— Fabrizio Balassone, Maura Francese, and Angelo Pace, “Public Debt and Economic Growth: Italy’s First 150 Years”

(2) Northern Italy accounts for more than 90% of Italian exports.

“The location of economic activity within a country is determined by three broad factors: (1) the location of natural advantages, such as mineral deposits, climate, or water supply; (2) domestic market access, meaning how well placed a location is to meet demand from the domestic market and also to obtain inputs from labor, capital, and intermediate goods markets; and (3) foreign market access, capturing access to international trade… Italy’s misfortune is that each, in the period when it was most important, has favored the North… As a consequence, the South of Italy now accounts for less than 10 percent of Italian exports. The legacy is that lack of international exposure weakens the competitive pressure to upgrade institutions and practice in business and in the wider socioeconomic environment. This is a vicious circle which there seems little prospect of breaking.”

— Brian A’Hearn and Anthony J. Venables, “Regional Disparities: Internal Geography and External Trade”

(3) Despite the massive flux of migrants into the country, there is “little evidence of a negative effect on the wages and unemployment prospects of native workers.”

“Massive immigrant flows invariably generate fears about their impact on the host economy. Such fears, amply represented in print and in economic studies, often focus on the impact of immigrants on unemployment, wages, and on the long-run budgetary position of the host country… [however] research into the labor market impact of that immigration finds little evidence of a negative effect on the wages and unemployment prospects of native workers. Gavosto, Venturini, and Villosio (1999) found that immigration impacted positively on the wages of native unskilled labor, whereas Venturini and Villosio (2002, 2006) found that immigrant share had no effect on the transition from employment to unemployment for native workers and that immigration had a positive effect on wages.”

— Matteo Gomellini and Cormac Ó Gráda, “Migrations”

(4) Italian companies are struggling to keep up with new technological developments.

“…For a significant part of the second half of the twentieth century, Italian firms’ innovative ability seems to be based more on creative adoption of foreign technologies and the systematic development of localized learning rather than on formal research (Antonelli and Barbiellini Amidei 2011)… In the era of new globalization the investment in local formalized innovative activity has become vital to capture and integrate with foreign sources of technologic knowledge, and the waning capacity to benefit from international knowledge flows has a critical role in the last decades’ Italian (underperforming) innovation. Moreover, the new direction of technologic change, based on digital technology favoring the intensive use of highly educated human capital (relatively scant in Italy), may have played a part in the recent decades’ innovative decay, dampening Italian firms’ absorptive capacity and slowing down their processes of creative adoption.”

— Federico Barbiellini Amidei, John Cantwell, and Anna Spadavecchia, “Innovation and Foreign Technology”

(5) It will be years before the country’s successful education reforms directly impact its economic productivity and growth.

“…It is encouraging that the fastest improvement in average years of schooling in the population ever achieved by Italy came in the first decade of the twenty-first century: from 8.3 in 2001 to 10.8 in 2010, equal to an increase by 2.9 percent per year (3.6 percent in the South), compared with 1.7 percent over the previous thirty years. More important still, the share of population aged twenty-five to sixty-four that completed tertiary (university) education increased from 9.4 percent in 2000 to 14.5 percent in 2009… In this area enormous progress was made in the first decade of the twenty-first century, despite low GDP growth. Given the low starting level, however, it will take several years for the ratio of university graduates in the population of working age to come close to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) average and make an impact on growth.”

— Gianni Toniolo, “An Overview of Italy’s Economic Growth”

All excerpts taken from chapters in Gianni Toniolo’s edited volume, The Oxford Handbook of the Italian Economy Since Unification. Gianni Toniolo is Research Professor of Economics at Duke University, Professor of Political Science at LUISS (Roma) and Research Fellow at the Center for Economic Policy Research in London. His research has been published in a number of academic journals and he has authored several books, including The World Economy between the Wars (Oxford University Press, 2008).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: “Rome Italy Night Evening Trevi Fountain Water” by tpsdave. Public domain via pixabay.

The post Five important facts about the Italian economy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGus Van Harten on investor-state arbitration“Law Matters” for money market fundsProtecting yourself from the threat of cyberwarfare

Related StoriesGus Van Harten on investor-state arbitration“Law Matters” for money market fundsProtecting yourself from the threat of cyberwarfare

What the ovaries of dinosaurs can tell us

Understanding the internal organs of extinct animals over 100 million years old used to belong in the realm of impossibility. However, during recent decades exceptional discoveries from all over the world have revealed elusive details such as fossilized feathers, skin, and muscle. The Upper Jurassic/Lower Cretaceous Chaomidianzi Formation of Liaoning province in northeastern China has done a great deal to contribute to this wealth of biological information on extinct organisms. Here, exceptionally well-preserved specimens are the norm; feathers are preserved in numerous specimens revealing morphologies that no longer exist today, even allowing scientists to determine the color of extinct dinosaurs. Internal organs and structures such as the crop and gizzard are inferred through preservation of their contents, revealing the diet of dinosaurs and birds over 120 million year old.

More recently, an even more unlikely discovery was made: several specimens of Early Cretaceous birds preserving ovarian follicles (the largest single cells in the body, essentially egg yolks in the ovary before they are ovulated into the oviduct, joined with albumen, and shelled) preserved in place within the abdominal cavity of the body. One specimen is referred to Jeholornis, a long boney-tailed bird only more derived than Archaeopteryx, and two specimens belong to Enantiornithes, the most diverse clade of Mesozoic birds and sister group to Ornithuromorpha, the clade that includes living birds (Neornithes). Together, these three specimens sample a fairly large spectrum of basal birds, revealing early evolutionary trends in reproductive behavior within the clade. After the initial identification of three specimens, my colleagues and I searched the enormous collections of the Shandong Tianyu Museum of Nature for additional specimens, turning up several more enantiornithine specimens preserving follicles. The Collection is heavily biased towards this clade, which apparently dominated the Cretaceous both in diversity and numbers.

The now dozen or so specimens of enantiornithine preserving ovarian follicles reveal a diversity of reproductive strategies. In Neornithes there exists an incredible spectrum: from birds born nearly independent and soon able to fly (super precocial), to those born blind, naked, and entirely dependent (altricial). In living birds, the more that is invested in the individual offspring, the fewer offspring there are in a clutch, and egg size is typically larger. Prior to ovulation, the number of mature ovarian follicles is a good indicator of clutch size — allowing clutch size to be estimated in these Jehol birds. The same trade off is observed in enantiornithines, and smaller egg to body size ratios are associated with larger clutches. Although the spectrum of egg to body size ratios observed in enantiornithines does not come close to that of Neornithes, this is not surprising given the limited ecological diversity observed among Jehol enantiornithines, which are interpreted as arboreal.

Although overlooked in the initial report of the Jehol specimens, the holotype of Compsognathus longipes also was described to preserve ovarian follicles. Although not entirely preserved within the body, descriptions of this specimen are consistent with observations from Jehol specimens and we concur with the author’s interpretation that these circular structures are ovarian follicles. Compsognathus is a primitive maniraptoran and thus reveals the condition outside Paraves (birds and their close relatives). This taxon is also larger than Jeholornis, the long-tailed bird, which is in turn much larger than all Early Cretaceous enantiornithines preserving ovarian follicles. However, despite the disparity in overall body size, follicle size is comparable in all specimens, consistent with S. J. Gould’s theory of egg size conservation — the idea that body size is more easily subject to evolutionary change than the size of the egg itself. This is also observed in ratites, the living group of large flightless birds, in which the large egg of the kiwi bird is the result of the body evolving smaller size while the egg stayed the same size as in other larger ratites (e.g. the ostrich and other even larger extinct relative such as Dinornis).

While egg size is apparently more difficult to change due to biological restrictions, body size is reduced in the theropod lineage that leads to Aves, which apparently facilitated the evolution of flight. As body size decreases around the egg size, the egg becomes increasingly larger and more massive relative to the body. At the same time, a trend in flying organisms is to reduce the weight of the body. Birds are unique among amniotes in that they typically only have one functional ovary and oviduct, the left. The loss of the right ovary, the larger of the two in crocodilians, is inferred to have evolved in order to reduce weight during flight. Imagine a gravid female bird with swollen ovaries and an ovum in each oviduct in the process of being shelled. Her body is considerably heavier than normal, impeding her ability to take off quickly and maneuver in flight.

Given that Early Cretaceous birds were relatively poor fliers compared to living birds, this added weight would have posed a considerable disadvantage. These limitations due to flight may have resulted in the eventual loss of the right ovary. The closest non-avian dinosaur relatives to birds preserve evidence for two functional ovaries and oviducts; one specimen of oviraptorosaur preserves an egg in each oviduct. However, every specimen of Jehol bird preserving ovarian follicles clearly preserves the cluster on the left side of the body, indicating the right ovary has been lost. The long boney-tailed Jeholornis is one of the most basal fossil birds indicating that the loss of the right ovary occurred at the dinosaur-bird transition, providing strong support for the hypothesis that birds lost an ovary in response to the physical restrictions of flight.

Dr. Jingmai O’Connor is associate professor at the Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Dr. O’Connor is a co-author of the paper ‘Ovarian follicles shed new light on dinosaur reproduction during the transition towards birds‘, which is published in the National Science Review.

Under the auspices of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, National Science Review is a new journal aimed at reviewing cutting-edge developments across science and technology in China and around the world. The journal focuses on topics of interest to the international science community, including multi-national collaborations, global issues in scientific and technological development, and their impact on society in general.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Fossil specimen (DNHM D2945/6) of the Early Cretaceous bird Hongshanornis longicresta. By Chiappe et al. [CC-BY-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The post What the ovaries of dinosaurs can tell us appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow meaningful are public attitudes towards stem cell research?Catch statistics are fishyDiseases can stigmatize

Related StoriesHow meaningful are public attitudes towards stem cell research?Catch statistics are fishyDiseases can stigmatize

January 21, 2014

Diseases can stigmatize

Names of diseases have never required scientific accuracy (e.g. malaria means bad air, lyme is a town, and ebola is a river). But some disease names are offensive, victim-blaming, and stigmatizing. Multiple sclerosis was once called hysterical paralysis when people believed that this disease was caused by stress linked with oedipal fixations. AIDS was initially called “Gay Men’s disease” when it was considered a disease only affecting white gay men. Fortunately, when these disease names were changed, those afflicted with Multiple Sclerosis and AIDS experienced less stigma. Inspired patient activists from around the world are currently engaged in another major effort to rename chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). It is a political struggle to alleviate some of the stigma caused by the language of scientists at the CDC 25 years ago.

Chronic fatigue syndrome is an illness as debilitating as Type II diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, multiple sclerosis, and end-stage renal disease. Yet 95% of individuals seeking medical treatment for CFS reported feelings of estrangement; 85% of clinicians view CFS as a wholly or partially psychiatric disorder; and hundreds of thousands of patients cannot find a single knowledgeable and sympathetic physician to take care of them. Patients believe that the name CFS has contributed to health care providers as well as the general public having negative attitudes towards them. They feel that the word “fatigue” trivializes their illness, as fatigue is generally regarded as a common symptom experienced by many otherwise healthy individuals. Activists add, that if bronchitis or emphysema were called chronic cough syndrome, the results would be a trivialization of those illnesses.

Powerful vested forces have opposed changes. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, when I mentioned over the years that patients were stigmatized by the term chronic fatigue syndrome, I was explicitly told it was reckless and irresponsible to change the name. This was despite the fact that patients wanted more medical-sounding name, and our research group had found that a more medical-sounding term like myalgic encephalopathy (ME) was more likely to influence participants to attribute a physiological cause to the illness.

Over the last decade, patient demands for change have grown louder. New names have occurred for several patient organizations (e.g. the Patient Alliance for Neuroendocrineimmune Disorders Organization for Research and Advocacy and the Myalgic Encephalomyelitis Society of America) and research/clinical settings (Whittemore/Peterson Institute for Neuro-Immune Disease). Even the federal government has begun to use the term ME/CFS, and the organization of researchers changed their name to the International Association of CFS/ME. Ultimately, many activist groups want the term myalgic encephalomyelits to replace CFS. Bringing about a name change is a complicated endeavor, and small variations of language can have significant consequences among the stakeholders.

In addition to this effort to rename chronic fatigue syndrome, there is considerable patient activism to change the case definition, which was arrived at by consensus at the CDC rather than through empirical methods. Patients report and surveys confirm that core symptoms of the illness include post-exertional malaise, memory/concentration problems, or unrefreshing sleep. Yet these fundamental symptoms are not required within the current case definition. Patients want the current case definition to be replaced with one that requires these types of fundamental symptoms. If laboratories in different settings identify samples that are not homogenous, then consistent biological markers will not be found, and then many will continue to believe the illness is one of a psychogenic nature, just as once occurred for multiple sclerosis. Clearly, issues concerning reliability of clinical diagnosis are complex and have important research and practical implications. In order to progress the search for biological markers and effective treatments, essential features of this illness need to be empirically identified to increase the probability that individuals included in samples have the same underlying illness.

If progress is to be made on both the name change and an empirical case definition, key gatekeepers including the patients, scientists, clinicians, and government officials will need to work collaboratively and in a transparent way to build a consensus for change. Considerable activity is currently ongoing at the federal level on these critical issues, but only through open communications and the building of trust will there be the possibility of overcoming the past 25 years, which have been marked by feelings of anger and hostility due to being excluded from the decision-making process.

Leonard A. Jason is a professor of clinical and community psychology at DePaul University, director of the Center for Community Research, and the author of Principles of Social Change. Read his previous blog posts on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only social work articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Overworked man frustrated and rubbing head. © apletfx via iStockphoto.

The post Diseases can stigmatize appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEncore! Encore! Encore! Encore!Remembering Daniel SternBlack American political thought

Related StoriesEncore! Encore! Encore! Encore!Remembering Daniel SternBlack American political thought

Writing historical fiction in New Kingdom Egypt

The origins of Egyptian literary fiction can be found in the rollicking adventure tales and sober instructional texts of the early second millennium BCE. Tales such as the Story of Sinuhe, one of the classics of Egyptian literature, enjoyed a robust readership throughout the second millennium BCE as Egypt transitioned politically from the strongly centralized state of the Middle Kingdom and through the political changes, population movements, and strife of the Second Intermediate Period into the imperial glories of the New Kingdom (1550-1070 BCE). During the New Kingdom, particularly the Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasties, the “Ramesside Period,” another literary efflorescence occurred. Among the genres of this new corpus of literary productions are stories that can be most properly described as works of “historical fiction.” Set in the past with attested historical characters, these works of historical fiction are an ancient Egyptian counterpart, albeit ultimately unrelated, to the mammoth corpus of modern historical fiction from Sir Walter Scott, Patrick O’Brien, and George McDonald Frasier to Ken Follett and Philippa Gregory.

Historical fiction in New Kingdom Egypt has never been identified as its own genre, but in identifying it as such, stories that represent this period in history are brought to life. Ancient evidence used to resurrect the plots and characters range from straightforward archaeological excavation to a diverse array of historical texts to an actual royal mummy, whose violent death portends the ending of one tale.

The sarcophagus lid of Queen Sitdjehuti, wife of pharaoh Seqenenre Tao II from Egypt’s 17th dynasty.

Imagine a kingdom divided — a native Egyptian ruler, Seqenenre, has control of the southern portion of Egypt, while his rival, a foreign Hyksos king, Apepi, dominates the north. Called by its modern title The Quarrel of Apepi and Seqenenere, the tale begins with just such a politically treacherous time around 1560 BCE that is a known historical setting. However, the tale as it survives was composed from the comfort of the early Nineteenth Dynasty, three hundred years later, when Egypt possessed an empire that stretched from ancient Syria all the way to southern Nubia.

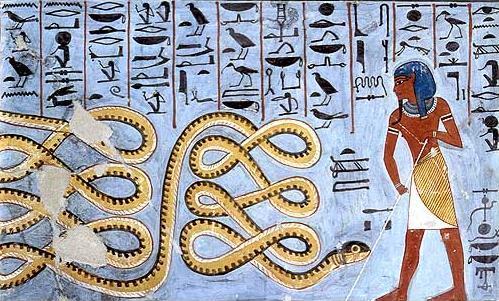

The drama begins when the Hyksos king, Apepi, requests that Seqenenre “expel the hippopotami” from a canal east of Thebes (the southern capital), since their roars are keeping him awake in his own capital hundreds of kilometers to the north. Ancient and modern audiences alike should laugh at such a ridiculous claim, but for the Egyptians, the hippopotami represent the deity that Apepi worships as a foreigner: Seth, a god of chaos and the deserts, a god who is in a sense the patron deity of foreigners like Apepi himself. By asking for actions to be taken against the hippopotami, Apepi betrays his own deity, casting himself into the role of the ultimate evil in Egyptian religion, the serpent Apep. In Egyptian religious texts, Seth fights Apep, the necessary evil of the ordered world turned against the unbridled chaos of the outer darkness. By betraying his own patron, Apepi becomes Apep, the ultimate foe of the order and disorder of the created world.

Apep being warded off by a deity.

The end of the tale does not survive on the one copy we have, as the scribe stopped writing the story and changed to an instruction of letter writing, so the conclusion of Apepi and Seqenenre’s quarrel over the hippopotami will remain an unsolved riddle until another copy of the tale in found. Historically, though, we know Seqenenre’s fate: death by a Hyksos battle axe.

The second story, known by its modern title The Capture of Joppa, opens with an Egyptian army besieging ancient Joppa, located near modern Jaffa. The beginning of the story is lost, but the preserved portion describes a group of drunken individuals and chariot horses being safely put away lest they be stolen by the Apiru, a group of local brigands. The Egyptian general Djehuty — another attested historical individual — is holding a conference with the enemy rebel of Joppa, apparently in a neutral space outside of the city walls. The enemy ruler of Joppa, who remains unnamed, is obsessed with seeing the staff of pharaoh, and in a moment of slap-stick humor, Djehuty obliges by smiting the ruler with the staff.

With the ruler of Joppa incapacitated, but not dead, Djehuty puts into motion one of the first attested ruses in ancient military history: he pretends to surrender to the city of Joppa, presenting hundreds of baskets as the “tribute” of his capitulation. Unknown to the citizens of Joppa, Egyptian soldiers are hidden within the baskets, and they promptly capture the city in what can only be described as a Trojan-horse style story. While the basket stratagem is in the realm of fiction, the setting of the story, Joppa, and its protagonist, Djehuty, are known through archaeological and textual sources — The Capture of Joppa truly is one of the world’s first examples of historical fiction.

Colleen Manassa, the William K. and Marilyn M. Simpson Associate Professor of Egyptology at Yale University, is an award winning author and Egyptologist. She is a frequent contributor to the History Channel and National Geographic Channel. Her most recent books include the catalog to the critically acclaimed exhibition at the Yale Peabody Museum – Echoes of Egypt: Conjuring the Land of the Pharaohs, and, newly released with Oxford University Press, Imagining the Past: Historical Fiction in Ancient Egypt.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Queen Sitdjehuti’s sarcophagus in Munich by Hans Ollermann [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Common. Apep, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Writing historical fiction in New Kingdom Egypt appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEscape Plans: Solomon Northup and Twelve Years a Slave“This strange fête”, an extract from The Lost DomainChristmas quotations from Oxford World’s Classics

Related StoriesEscape Plans: Solomon Northup and Twelve Years a Slave“This strange fête”, an extract from The Lost DomainChristmas quotations from Oxford World’s Classics

Encore! Encore! Encore! Encore!

How much repetition is too much repetition? How high would the number of plays of your favorite track on iTunes have to climb before you found it embarrassing? How many times could a song repeat the chorus before you stopped singing along and starting eyeing the radio suspiciously? And why does musical repetition often lead to bliss instead of exhaustion?

Music is repetitive, but just how repetitive remains a somewhat murky question. Repetition is found in the music itself, but also in your listening behavior. Your favorite track might feature a chorus that repeats several times, but you might also choose to play and replay this already repetitive track ad nauseam. David Huron estimates that more than 90% of the music people hear is music they’ve heard before. Victor Zuckerkandl explains:

Music can never have enough of saying over again what has already been said, not once or twice, but dozens of times; hardly does a section, which consists largely of repetition, come to an end, before the whole story is happily told all over again.

This kind of repetition is so common in music that most of the time we don’t even notice it. But if I recounted the same story to you even twice, let alone 15 times, you’d start avoiding me in the hallways. Although cognitive scientists have often looked to music and language as comparative cases with intriguing similarities, repetition marks a clear point of divergence: we embrace it in one domain and shun it in the other.

But even musical repetitiveness has its limits. The band the National tested them when performing the song “Sorrow” 105 times in a row as part of an installation at MoMA PS1 in New York. How do we decide that enough is enough? It turns out we’re quite good at calibrating our own sensibilities. Toddlers, for example, will often insist on being read the same story night after night. To parents, this can seem counterproductive. In order to learn new words, shouldn’t they need to hear them in a variety of different contexts, so they’re equipped to eventually abstract their meaning?

University of Sussex psychologist Jennifer Horst and colleagues have shown, contrary to this adult intuition, that repetitions of the same story are precisely what toddlers need. Over the course of a week, three-year-olds heard a novel word the same number of times either within repeated tellings of the same story, or different tellings of different stories. Children subjected to what might seem an unendurable amount of repetition for an adult actually learned better. The toddlers know what they need.

Similarly, recent research in my lab has shown that the adult proclivity for musical repetition is no fluke. When repetition was added to pieces of challenging contemporary art music that typically eschew it, everyday listeners found the music more enjoyable and more interesting. What’s more, they even found the repetitive music more likely to have been crafted by a human artist than randomly generated by a computer.

When people heard pieces of music featuring either exact repetition or varied repetition, they found themselves more likely to tap or sing along when the repetition was exact. Repetitiveness increased their kinesthetic engagement with the sound. In another study, listening to music repeatedly caused listeners to shift their attention to different structural levels in the piece, revealing new and rewarding aspects of the music that had been inaccessible on first hearing.

Carlos Silva Pereira at the University of Porto used neuroimaging to reveal that the circuitry underlying emotional response was more active for music that had been repeated. This effect held for music that participants reported liking and for music that participants reported disliking. In other words, musical repetition can engage us even against our will.

When we hit that button to put a track on repeat, we’re doing what we need to do for the sound to carry us to that distinct brand of bliss only music can afford. Just don’t take it too far, or you’ll be left with a hard-to-squash earworm and a longstanding aversion to the chorus.

Elizabeth Hellmuth Margulis directs the Music Cognition Lab at the University of Arkansas. She is the author of On Repeat: How Music Plays the Mind. Her research uses theoretical, behavioral, and neuroimaging methodologies to investigate the dynamic, moment-to-moment experience of listeners without special musical training. She was also trained as a concert pianist.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Eccentric Concentric. © Michael Henderson via iStockphoto.

The post Encore! Encore! Encore! Encore! appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRemembering Daniel SternLandfill Harmonic: lessons in improvisationWhat the bilingual brain tells us about language learning

Related StoriesRemembering Daniel SternLandfill Harmonic: lessons in improvisationWhat the bilingual brain tells us about language learning

January 20, 2014

Black American political thought

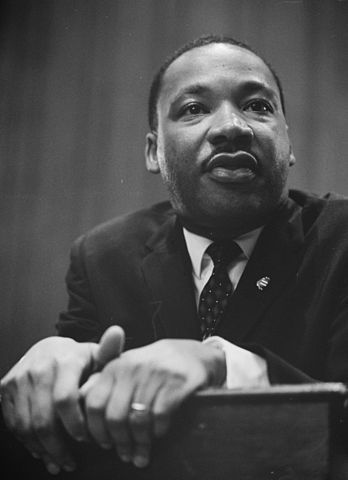

Today the United States celebrates Martin Luther King, Jr Day, to honor a leader that changed a nation. Among his many accomplishments, Dr. King contributed a unique perspective and vocabulary to political thought — one of many black writers and activists who urged Americans to fundamentally re-imagine the nature of their democracy. On this occasion, we present an adapted extract from The Time is Always Now: Black Thought and the Transformation of US Democracy by literary critic and intellectual historian Nick Bromell.

Black American thought about democracy has been too varied and complex to be reducible to a single program or philosophy. Still, within the ever-changing stream of black American political reflection, we can discern a strong current that has sought to achieve full citizenship for black Americans by transforming democracy for all Americans. This current has drawn from both the assimilationist and separatist strains of black political thought, so it cannot be held within either term of this binary. Its vision arises in large part from its critique of the racialized nature of US democracy, or what Charles Mills has called “racial liberalism,” yet it does not abandon hope for democracy. Nor should it be identified with what cultural historian Richard Iton has called (perhaps unfairly) the Bayard Rustin legacy of “pragmatism, instrumentalism, and compromise” that renders black political ideas “acceptable [only] if they correspond to the patterns and practices prevalent in the American national context.” Many black American thinkers provide insights into democracy that disrupt established “patterns and practices” and propose fundamental transformations of “mainstream American norms” of democratic thought and citizenship.

Their thinking originates in a standpoint, or perspective, profoundly different from that of white Americans and from much mainstream democratic theory, be it liberal, republican, Marxist, Straussian, communitarian, agonistic, or deliberative. As Mills and other black philosophers have emphasized, black American political thinkers have understood themselves to be embedded in the matrix of their historical moment, so that the distancing move on which so much history and philosophy depends was seldom available—or appealing—to them. They have been activist thinkers engaged in the politics of the moment. Their raced black bodies have made it doubly unthinkable to them that their theorizing could be occurring somewhere outside of time and space, in a realm of pure thought. This is why Leonard Harris has called black thought a “philosophy born of struggle,” and why Patricia Hill Collins writes that “It is impossible to separate the structure and thematic content of thought from the historical and material conditions shaping the lives of its producers.” Eschewing the stance of distance and the trope of spectatorship that are embedded in the word “theory” itself, black thought works, as George Yancy writes, “within the concrete muck and mire of raced embodied existence.” From this place, from the mire of an unrealized democracy, black political thinkers have found that some of the concepts and keywords coined by the white mainstream are inadequate to the task at hand.

Their thinking originates in a standpoint, or perspective, profoundly different from that of white Americans and from much mainstream democratic theory, be it liberal, republican, Marxist, Straussian, communitarian, agonistic, or deliberative. As Mills and other black philosophers have emphasized, black American political thinkers have understood themselves to be embedded in the matrix of their historical moment, so that the distancing move on which so much history and philosophy depends was seldom available—or appealing—to them. They have been activist thinkers engaged in the politics of the moment. Their raced black bodies have made it doubly unthinkable to them that their theorizing could be occurring somewhere outside of time and space, in a realm of pure thought. This is why Leonard Harris has called black thought a “philosophy born of struggle,” and why Patricia Hill Collins writes that “It is impossible to separate the structure and thematic content of thought from the historical and material conditions shaping the lives of its producers.” Eschewing the stance of distance and the trope of spectatorship that are embedded in the word “theory” itself, black thought works, as George Yancy writes, “within the concrete muck and mire of raced embodied existence.” From this place, from the mire of an unrealized democracy, black political thinkers have found that some of the concepts and keywords coined by the white mainstream are inadequate to the task at hand.

For this reason, black American writers and thinkers have often invented vocabularies with a different accent—crafting images, stories, concepts, and keywords to name different stakes and values. We may have read them, but we may not have recognized their words as bearers of “political thought” if we have read them solely through the lens provided by the mainstream, white political tradition. “There are tongues in trees, sermons in stones, and books in the running brooks! Those laws did speak!” Frederick Douglass declared in response to the Supreme Court’s overturning of the 1875 Civil Rights laws. Douglass was plainly figuring those laws as things of nature that could speak. But why? If we read his words only as a metaphor and fail to take with complete seriousness the radical vision of democracy the metaphor points to, we miss most of what he, once considered a “thing” himself, had to say: things can sometimes speak what men know but cannot or will not say. Any effort to put black political thought into conversation with conventional political theory must register the ways black thought exceeds and radically supplements such theory.

A small but growing number of scholars in the field of political theory have begun this work and I am deeply indebted to them. They include, among others, Danielle S. Allen, Lawrie Balfour, Gregg Crane, Eddie S. Glaude, Robert Gooding-Williams, Michael Hanchard, Jason Frank, Richard H. King, Ross Posnock, Adolph Reed, George Shulman, Jack Turner, and Iris Marion Young. They have given me—as someone housed in an English department and trained to read literary texts—much of the conceptual vocabulary I use to articulate the ways literature thinks about the political in general and democracy in particular. I find common ground with many of these scholars also in believing that the imagination itself does important political work, providing what Wolin has called “a corrected fullness,” a vision of political phenomena not only as they are, but as they might be.

Bringing together political theory with my own training in literary and cultural studies, then, I hope to contribute to a vigorous conversation between these fields. Yet even as I work in both disciplines, I also depart from some conventions they share. I don’t seek to present either a history or an elaborated theory of black American perspectives on democracy. Instead, following the orientation of the writers, I put their ideas to work in the present and in response to a particular problem today — for now is the temporal frame within which these black American thinkers usually placed themselves. They lived in and shared Martin Luther King’s “fierce urgency of now.” They occupied with Frederick Douglass “the ever-present now” from which he declared, “we have to do with the past only as it is of use to the present.”

I write, then, at a particular moment and with an eye toward a specific problem: the disintegration of Americans’ shared understanding of democracy.

Nick Bromell is the author of The Time is Always Now: Black Thought and the Transformation of US Democracy (OUP USA); By the Sweat of the Brow: Labor and Literature in Antebellum American Culture and Tomorrow Never Knows: Rock and Psychedelics in the Sixties, both published by the University of Chicago Press. His articles and essays on African-American literature and political thought have appeared in American Literature, American Literary History, Political Theory, Raritan, and The Sewanee Review. He teaches at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and he blogs at thetimeisalwaysnow.org.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Martin Luther King leaning on a lectern. 26 March 1964. Public domain via Library of Congress.

The post Black American political thought appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow secure are you?Protecting yourself from the threat of cyberwarfareThe real Llewyn Davis

Related StoriesHow secure are you?Protecting yourself from the threat of cyberwarfareThe real Llewyn Davis

A brief and incomplete history of astronomy

NASA posted an update in the last week of December that the international space station would be visible from the New York City area—and therefore the Oxford New York office—on the night of 28 December 2013. While there were certainly a vast number of NASA super fans rushed outside that particularly clear night (this writer included), it’s difficult for recent generations to recall a time when space observations and achievements like this contributed significantly to the cultural zeitgeist. When Sputnik orbited the earth in 1957, entire families rushed onto their lawns for a chance to see the tiny speck of light sail across the sky. The slideshow below, based on an Oxford Reference timeline, reflects a number of key, transformative moments in the study of astronomy, illustrating how far this last century has taken us.

1054

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Astronomers in China and Japan observe the explosion of the supernova which is still visible as the Crab Nebula

1543

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus publishes a book suggesting that the earth moves round the sun

1610

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Galileo, with his new powerful telescope, observes the moons of Jupiter and spots moving on the surface of the sun

1905

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Percival Lowell predicts the existence of an unknown planet, almost exactly where Pluto is discovered 25 years later

1926

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

British astrophysicist Arthur Eddington compares mass and luminosity in The Internal Constitution of the Stars

1929

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

US astronomer Edwin Hubble uses the red shift of light from galaxies to demonstrate that they are receding from each other and the universe is expanding

1957

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The success of the USSR in launching Sputnik prompts the establishment of NASA in the USA

1961

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin becomes the first human to travel in space, orbiting the earth once in Vostok 1

1961

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

President Kennedy commits the US to placing a man on the moon and bringing him back safely by 1970

1968

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The US astronauts in Apollo 8 are the first humans to see (and photograph) the sight of the earth rising above the moon's horizon

1971

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

In the Apollo 15 mission US astronauts David Scott and James Irwin drive the vehicle Rover-1 on the surface of the moon

1998

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The first module is launched of the International Space Station, a cooperative venture by five space agencies (USA, Russia, Japan, Canada, Europe)

Oxford Reference is the home of Oxford’s quality reference publishing, bringing together over 2 million entries, many of which are illustrated, into a single cross-searchable resource. With a fresh and modern look and feel, and specifically designed to meet the needs and expectations of reference users, Oxford Reference provides quality, up-to-date reference content at the click of a button.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits:

(1) Crab Nebula, Joseph DePasquale, Chandra X-Ray Observatory, NASA.

(2) Nicolaus Copernicus – The Heliocentric Solar System (illustration). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

(3) Portrait of Galileo Galilei by Domenico Cresti da Passignano. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

(4) Percival Lowell observing Venus. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

(5) Arthur Stanley Eddington via Library of Congress.

(6) The Hubble Space Telescope via NASA.

(7) Illustration of the seal of NASA, via NASA.

(8) Yuri Gagarin, Convair/General Dynamics Plant and Personnel. Public domain via San Diego Air & Space Museum Archives.

(9) President John F. Kennedy at Cape Canaveral in November 1963. Public domain via NASA.

(10) View from the Apollo 11 spacecraft. Public domain via NASA.

(11) Apollo 15 Lunar Module pilot James B. Irwin loads up the “Rover.” Public domain via NASA.

(12) International Space Station. Public domain via NASA.

The post A brief and incomplete history of astronomy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA voyage in letters [infographic]The Crab NebulaFractal shapes and the natural world

Related StoriesA voyage in letters [infographic]The Crab NebulaFractal shapes and the natural world

Gus Van Harten on investor-state arbitration

What is investor-state arbitration? And how does it impact upon people’s lives? Today, we present a Q&A with Gus Van Harten, author of Sovereign Choices and Sovereign Constraints, where he explains the fundamentals of investor-state arbitration and its place in international law.

What is the most pressing issue in your field right now?

It is to raise awareness about investor-state arbitration which, briefly, allows companies to sue countries (but not vice versa) before a tribunal of for-profit arbitrators that is insulated from judicial review.

We are at a stage where governments and the European Commission may extend this opaque but powerful arbitration mechanism via new trade and investment agreements among developed countries that have mature democracies and judicial systems. This would be a significant departure from the usual approach to resolving disputes between business and the state in those countries.

In the past, the constraints imposed by investor-state arbitration were reserved — with the main exception of Canada under NAFTA — to developing and former East Bloc countries. Even in that context, the system’s implications unfolded in surprising ways since the explosion of investor claims began in the late 1990s. We have seen highly creative claims by investors challenging judicial decisions and general policies, third-party speculative financing of claims, and apparent conflicts of interest in the arbitration process.

If the system is extended to developed countries, the mechanism will be locked in for decades as part of global government. This poses issues of democratic accountability, policy flexibility, and the fiscal risk. I think people and policy-makers need to have a chance to understand the implications before the system is locked-in.

How does it illustrate the way that international law impacts on wider developments in people’s lives?

For most people — those who don’t own tens of millions in assets located abroad — the system diminishes their rights as voters, their security as taxpayers, and their bargaining position when dealing with governments in opposition to a foreign company. It is hard to say to what extent and in what precise ways these things are diminished because the explosion of claims is very recent and still expanding and difficult to analyze systematically. Yet it is clear that the public will be constrained by international investor-state arbitration in ways that go well beyond other forms of international or domestic adjudication.

International law used to be a sleepy area because it lacked hard rules based on binding adjudication. That has changed in recent decades, sometimes in positive ways. However, in international investment law, there has been a sea change and a unique departure from a judicial model of decision-making. A narrow group of actors has been given unparalleled power to attack legislative, regulatory, and judicial decisions. The main beneficiaries — measured by amounts of money awarded — have been very large companies which qualify foreign investors under the treaties.

This power of companies to sue countries is remarkable for various reasons. For example, the term investment is defined broadly in the treaty to include not just land and factories but also more creative concepts such as derivatives, swaps, permits, and patents. Foreign investors unlike anyone else have been given the right to sidestep domestic courts when they bring an international claim. Thus, they can have their claim decided in an advantageous non-judicial forum that is closed to other actors whose rights or interests are affected. Foreign investors are also freed from the prospect of an equivalent claim by the state where a company is alleged to have behaved badly. The companies obtain large amounts of public compensation – sometimes where domestic courts would not award compensation – from arbitrators who lack the usual safeguards of judicial independence and fairness but are insulated or immunized from judicial review.

The treaties creating these foreign investor rights date from decolonization in the late 1960s. They came to fruition with the boom of claims in the 1990s. It sounds alarmist but, from my vantage point, the system’s rapid expansion, largely at the discretion of arbitrators, has altered sovereignty as we have known it in the developed world for centuries and as it has been known in much of the developing world since the colonial era.

How do you see the issue developing over the next few months or years?

Investor-state arbitration will continue to garner attention. More countries are going to be sued and ordered to pay compensation in new and creative ways. For instance, a group of people will demand that their government change a decision. When the government responds, people will discover to their surprise that this arbitration mechanism puts a new layer of strong financial constraints on what governments can do.

Many countries woke up to investor-state arbitration only after it was too late to exit the system because of the lock-in periods in the treaties. Will governments that remain less-exposed be more careful before entering the minefield? Brazil is perhaps the best example of a country that looked carefully at the system about a decade ago and said, no thank you, we are not interested. Yet Brazil has done very well attracting foreign investment.

Another question is how far the arbitrators will take their power over the public purse. In late 2012, the largest known award – over two billion dollars – was issued against Ecuador in favour of a US oil company. The largest case I’ve heard of involves about $200 billion in disputed mineral assets. Given the role of repeat players among the arbitrators and their apparent incentives to grow the business by encouraging claims, we may see yet more expansion once developed countries lock themselves in.

What do you hope to see in the coming years from both the field and the issues your academic work focuses on?

I hope to see more outside people take a look at the system. It is difficult to bring those people in because legal specialists often bury the discussion in hair-splitting details. Yet there is a lot of benefit from greater attention by economists, anthropologists, marine biologists; you name it. The system is relevant to nearly any fields because almost any government decision can trigger an investor claim or get stifled by the risk of a claim.

In my research, I am working on an interview-based project on how investor-state arbitration affects government decisions internally. There is a lot of complexity to this question but, basically, it is debated whether the treaties chill good decisions or deter bad ones. We use interviews with current and former insiders to try to shed light on this issue. I think it is a priority because a large portion of the iceberg has thus far been hidden from view.

That is, what happens behind the scenes when a lawyer or lobbyist threatens a government with a claim? How often is this done and how do governments react? One might expect the rational cost-conscious government to withdraw proposed measures in the face of objections from large companies, where there is a non-negligible risk of large-scale liability. Some interviewees have made clear that this happens. On the other hand, it does not happen all the time and may be highly unlikely in some contexts. We would like to get a more precise sense of where and in what ways this regulatory change occurs.

Gus Van Harten is Associate Professor of Law at Osgoode Hall Law School. He is the author of Sovereign Choices and Sovereign Constraints, published by Oxford University Press (2013).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Law gavel on a stack of American money. © merznatalia via iStockphoto.

The post Gus Van Harten on investor-state arbitration appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories“Law Matters” for money market fundsProtecting yourself from the threat of cyberwarfareHow secure are you?

Related Stories“Law Matters” for money market fundsProtecting yourself from the threat of cyberwarfareHow secure are you?

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers