Oxford University Press's Blog, page 851

January 30, 2014

Have you ever wondered how snakes work?

Have you ever wondered how a snake slithers up a tree, captures prey far larger than the size of its jaw, or sheds all of its skin? Not many people give these reptiles a second thought. But Dr. Harvey Lillywhite, herpetologist and Professor of Biology at the University of Florida, gives them a great deal of thought. In How Snakes Work: Structure, Function and Behavior of the World’s Snakes, he covers all of the intricacies that make up snakes across the globe—from the more-or-less harmless creatures we find slithering in our backyards to the dangerously venomous reptiles we hope to never encounter in the desert. The snake slideshow below, with facts from the book and snakes photographed by Dr. Lillywhite, demonstrates how much can be learned about these fascinating reptiles including their exceptional anatomy, senses, and movements.

How have snakes evolved?

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Over time, different species of snakes have evolved with very particular adaptations that aid in their survival. This image of a Western Hognose Snake highlights the species’ snout—which helps these snakes burrow into the ground.

How do snakes eat?

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

One of the most gripping features of a snake is its ability to capture and swallow prey without the aid of any appendages. The extreme mobility of a snake’s jaw allows this reptile to swallow food far larger than the size of its head.

How does snakes' venom work?

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Venomous snakes deliver their venom via fangs. This venom can affect prey in a variety of ways, depending on the molecular composition of the venom. Many venoms damage the cell membranes of the victim’s cells, which helps this toxic substance spread quicker throughout the victim’s body. Some venoms can even bind to the proteins involved in neurotransmission of signals between cells, which in turn paralyzes the prey and inhibits its ability to run away.

How do snakes digest food?

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Snakes have a lower rate of metabolism than do mammals, and they require less food. Snakes are also intermittent feeders, and some captive snakes have been documented to fast for more than one whole year between meals. Because snakes only eat periodically, they do not waste energy on maintaining their digestive organs’ function at all times. Snakes have developed the means to up-regulate digestive enzyme production and intestine activity only when food has been consumed. Between feedings, some snakes allow their digestive tract to atrophy.

How do snakes slither?

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The side to side movement that we non-snake experts have come to call slithering is referred to in scientific terms at “horizontal undulatory progression.” Put simply, snakes alternate muscle contractions in a wavelike pattern in order to propel themselves over water or through a variety of terrestrial landscapes. These organized contractions exemplify the development of precise neuron signaling within the bodies of snakes.

How do snakes stay warm?

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Snakes are ectotherms, which means that their bodies depend on heat exchanges with their surrounding environment. Heat passes from the environment to the snake’s body through the snake’s scales. Factors such as the coloration and arrangement of these scales, and the position and posture of the body, will influence the rate at which this heat is ultimately transferred to the snake’s body.

How do snakes breathe?

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Snakes are no exception when it comes to species that require a steady intake of oxygen to survive. Snakes breathe in air through nostrils or nasal openings. A snake’s tongue is not involved in this intake of oxygen, and is used instead primarily for sensory functions.

How do snakes always keep their eyes open?

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Have you ever noticed that snakes’ eyes never appear to close? This is because snakes do not possess eyelids. As such, their cornea requires a special coating called a spectacle or brille. This covering is actually a clear extension of the snake’s skin.

How do snakes hear approaching predators?

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Despite the fact that snakes can make sound—whether that be hissing noises or the rattling of a tail—hearing in snakes is limited. Snakes do not possess any external ears, and instead they rely on conduction of sound or ground vibrations through tissues of the head and body. Snakes can hear sound over a limited range of frequencies compared to humans, but detection of airborne or ground-borne vibrations is an important means by which they stay alert and aware of their surroundings.

How do snakes reproduce?

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Though most snakes appear to look the same to an un-trained eye, snakes can be differentiated between male and female. This is an important distinction to make when it comes to snake reproduction. Like other reptiles, fertilization in snakes is a process that occurs internally within females during copulation with a male partner. Mating and fertilization, however, do not have to occur at the same time, as females can store male sperm—often times from multiple different mates—for several months or years. This adaptation allows females to lay eggs at the most optimum time and with sperm from the most optimum mate, thus increasing the chances of her offspring’s survival.

How do I learn more about snakes?

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

These slides only provide a glimpse of the astounding features that make up snakes. To learn more, pick up your copy of "How Snakes Work: Structure, Function and Behavior of the World’s Snakes."

Harvey B. Lillywhite is a Professor of Biology at the University of Florida and the Past Director of the University of Florida Marine Laboratory at Seahorse Key. He is the author of How Snakes Work: Structure, Function and Behavior of the World’s Snakes.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only earth, environmental, and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: All of the images used in this slideshow were photographed by Dr. Harvey Lillywhite.

The post Have you ever wondered how snakes work? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIn the ‘mind’s eye’: two visual systems in one brainIn memoriam: Pete SeegerWhy do polar bear cubs (and babies) crawl backwards?

Related StoriesIn the ‘mind’s eye’: two visual systems in one brainIn memoriam: Pete SeegerWhy do polar bear cubs (and babies) crawl backwards?

What does opera have to do with football? More than you’d expect

Perhaps you saw that Dr. Pepper ad in which Ravens kicker Justin Tucker shows off his opera chops, singing in a quite lovely bass-baritone voice:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Well, we saw it, and it got us thinking: have there been other opera-singing American football players? How often does the mandolin solo from Don Giovanni appear in football-related ads? The answer to the first question is “yes, a surprising number.” In no particular order, here are some golden-throated pigskin hurlers:

Ta’u Pupu’a, former NFL defensive lineman and Juilliard School graduate.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Keith Miller, former University of Colorado fullback making regular appearances at the Metropolitan Opera.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Morris DeRhon Robinson, former Citadel offensive guard and prolific concert singer.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Lawrence “Larry” Harris, former offensive lineman for the Houston Oilers, who has appeared in productions throughout the United States.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Paul Robeson, former Rutgers University player, who was less focused on opera as a singer, but too good not to include here.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The answer to the second question? We’ll just go with “not very”.

So maybe listening to Don Giovanni isn’t the best way to prepare for the big game. But with legendary soprano Renée Fleming singing the national anthem before the Seahawks and Broncos face off this weekend — the first time an opera singer has ever sung the anthem at the Superbowl — there’s never been a better time to crack open a beer, grab some nachos, and listen to your favorite aria.

Meghann Wilhoite is an Assistant Editor at Grove Music/Oxford Music Online, music blogger, and organist. Follow her on Twitter at @megwilhoite. Read her previous blog posts on Sibelius, the pipe organ, John Zorn, West Side Story, and other subjects.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post What does opera have to do with football? More than you’d expect appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEponymous Instrument MakersTen fun facts about Claudio MonteverdiWhy we should dive deep into studying music history

Related StoriesEponymous Instrument MakersTen fun facts about Claudio MonteverdiWhy we should dive deep into studying music history

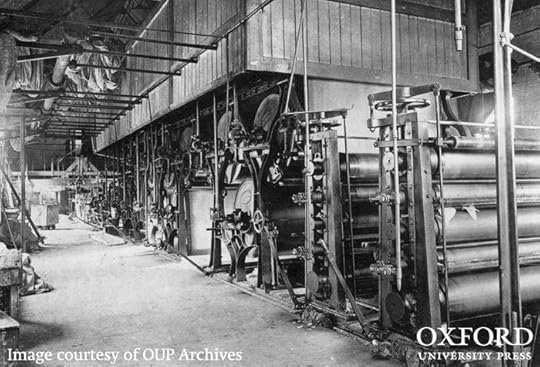

Half the cost of a book

For most of the history of the printed book, from Gutenberg in 1455 onwards, the most expensive part of the material book was paper. Until the mid-nineteenth century, by which time paper was being made by steam-driven machines using esparto grass and wood pulp rather than traditional linen rag as raw material, paper commonly represented at least half the cost of a book’s production.

Paper, its quality, its quantity and its provision was therefore a recurrent theme in the deliberations of the Delegates (those who ran Oxford University Press). On 20 May 1791 ‘the very best paper made by Whatman’, a specimen of which the Delegates had seen, was to be used for the new quarto edition of Aristotle’s Poetics. This almost certainly would have been wove paper rather than the more traditional laid paper (which had a chain and wire pattern). Wove paper, which had no such pattern, was first developed by James Whatman between 1754 and 1756, though it only became widely manufactured in the 1780s and 1790s.

Fourdrinier paper-making machine in Wolvercote Mill in the late 19th century. From The History of Oxford University Press.

The excise duty on paper was a frequent problem for all printers and publishers. The reorganisation of the duty in 1794, whereby it was charged by weight rather than ream, had the effect of making the burden heavier; paper duty was to change again in 1801, 1809, and 1819. In 1795 there was a discussion between the Delegates and those who ran Cambridge University Press (the Syndics) on how to respond to an increase in paper duty. In June 1808 they were again exercised by the rising cost of paper and its effects, in particular on the printing of bibles. This preoccupation is not surprising. In 1779 the Delegates’ accounts recorded that over £762 had been spent on paper alone, 55.3% of a total expenditure of £1,378 of the Learned Press and, though perhaps an exceptional year, the proportion of the Press’s costs represented by paper remained very high throughout these early decades. In 1800, for instance, the Learned Press spent £825 on paper or 34.6% of its total expenditure of £2,382.

An Act of 1794 also required the dating of watermarks in paper in an attempt to prevent a fraud that might otherwise have taken place during the process of ‘drawback’. This requirement was rescinded in 1811 but many papermakers continued to date their paper. Drawback allowed those entitled institutions (including the two university presses) to claim back the duty paid on paper that was subsequently used to print bibles, new testaments, psalms, and books of common prayer. A similar arrangement had been established by an Act of 1712 which allowed the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge to claim a refund of duty paid on paper that was then used to print works in Greek, Latin, oriental, and ‘northern languages’. By the early nineteenth century the drawback on paper was worth a considerable amount to OUP. As production increased so did the amount of paper used, the duty on which the Press could now claw back. In 1804 the sum was £1,088.3.5, by 1808 it was up to £1,891.3.0 although this was exceptional. On average drawback amounted to £1,088 per annum between 1804 and 1817.

In 1800, and for many decades afterwards, learned printing was small beer to the Press. In 1800 the paper bought for bible printing was valued at £7,542.17.0, nine times the value of paper bought by that part of the Press devoted to producing learned books. The printing of bibles may have been regarded as an act of piety, but by the early nineteenth century was becoming a big business amid the dreaming spires of Oxford.

Simon Eliot is Professor of the History of the Book in the Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London. He is general editor of The History of Oxford University Press, and editor of its Volume II 1780-1896.

With access to extensive archives, The History of Oxford University Press is the first complete scholarly history of the Press, detailing its organization, publications, trade, and international development. Read previous blog posts about the history of Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Half the cost of a book appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDamp paper and difficult conditions“Before he wrote it, he lived it”?Printing and the heat death of the universe

Related StoriesDamp paper and difficult conditions“Before he wrote it, he lived it”?Printing and the heat death of the universe

In the ‘mind’s eye’: two visual systems in one brain

Vision, more than any other sense, dominates our mental life. Our visual experience is so rich and detailed that we can scarcely distinguish that subjective world from the real thing. Even when we are just thinking about the world with our eyes closed, we can’t help imagining what it looks like. Our language is full of visual metaphors. We can ‘see the point’, if we are not ‘blind to the facts’. We occasionally show ‘foresight’ (though perhaps more often ‘hindsight’) by ‘seeing the consequences’ of our actions in our ‘mind’s eye.’

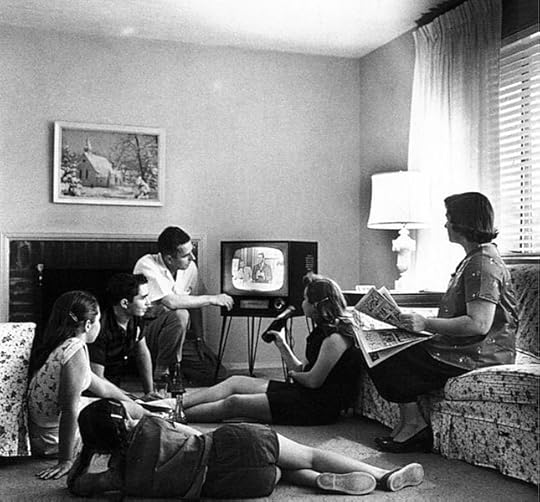

But where does that rich visual experience come from? Most of us have the strong impression that we are simply looking out at the world and registering what we see—as if we were nothing more than a rather sophisticated video camera that delivers a faithful reproduction of the world on some kind of screen inside our heads. This idea that we have an internal picture of the world is compelling, yet it turns out to be not only misleading but fundamentally wrong.

There is much more to vision than just pointing our eyes at the world and having the image projected onto an internal screen. Our brain has to make sense of the world, not simply reproduce it. In fact, the brain has to work just as hard to make sense of what’s on a television screen in our living room as it does to make sense of the real world itself. So putting the television screen in the brain doesn’t explain anything. (Who is looking at the screen in our heads anyway?) But an even more fundamental problem is that our visual experience is not all there is to vision. It turns out that some of the most important things that vision does for us never reach our consciousness at all.

Who is looking at the screen in our heads anyway?

One way to get a handle on how vision works is to study the visual life of people with damage to different ‘visual’ parts of the brain. Research of this kind is revealing just how misleading our intuitions about how vision works can be. In some cases, it is easy to get a feel for what such individuals might experience. For example, some patients lose the capacity to see any colours at all; in other words, they see the world in shades of grey. A depressing but easily imagined experience. After all, most of us are familiar with black and white drawings, photos, and films. But imagine the opposite scenario, being able to see colour and even the fine texture of objects, but losing the ability to discern the geometry of those objects. Such patients, although rare, do exist. There are other equally rare patients who appear to have lost all conscious experience of visual motion, despite being able to see that objects have changed their positions – an experience that might be akin to seeing disco dancers under a strobe light. All of these examples help us understand how the brain constructs our conscious visual experience of the world.

But the role of the brain in creating our conscious visual experience is not all we can learn from studying patients with brain damage. When asked to talk about their visual problems, of course, patients will describe their conscious experience of the world. That’s all any of us can do. But there are other ways of finding out what people can ‘see’. If we look at their behaviour rather than simply listening to what they tell us, we may discover that they have other visual problems not apparent to their own awareness—or conversely that they may be able to see far more than they think they can.

Trying to understand the visual problems that brain damage may cause can cast light on a more fundamental question: Why do we need vision in the first place? A compelling argument can be made that we need vision for two quite different but complementary reasons. On the one hand, we need vision to make sense of the objects and events in the world beyond our bodies. On the other hand, we also need vision to guide our actions in that world from moment to moment. These are two quite different job descriptions, and nature seems to have given us two different visual systems to carry them out. One system, the one that allows us to recognize objects and build up a database about the world, is the one we are more familiar with, the one that gives us our conscious visual experience. The other, much less studied and understood, provides the visual control we need in order to move about and interact with objects. This system does not have to be conscious, but it does have to be quick and accurate. We have investigated a unique neurological patient (D.F.) over a long period who has no conscious perception of object size and shape, but who, through an intact visual control system, is able to orient and shape her hand to pick up objects without any trouble. It was D.F.’s remarkable ability to interact visually with objects whose features she cannot perceive that first led us to the idea of separate visual systems for perception and action.

The idea of two visual systems in a single brain initially seems counterintuitive or even absurd. It seems to conflict with all of our everyday assumptions about how the mind works. In fact, the idea of separate visual systems for perceiving the world and acting on it was not entertained as a plausible scenario even by visual scientists until quite recently. Our visual experience of the world is so compelling that it is hard to believe that a quite separate visual system in the brain, inaccessible to visual consciousness, could be guiding our movements. It seems intuitively obvious that the visual image that allows us to recognize a coffee cup must also guide our hand when we pick it up. But this belief is an illusion. Studies of D.F. and other neurological patients, and complementary research on the normal brain, particularly using brain imaging, is making it abundantly clear that the visual system that gives us our conscious experience of the world is not the same visual system that guides our movements in the world.

Melvyn Goodale (University of Western Ontario, Canada) and David Milner (Durham University, UK) are the authors of Sight Unseen: An Exploration of Conscious and Unconscious Vision published by Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: Family watching television, c. 1958. Photo by Evert F. Baumgardner. National Archives and Records Administration. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post In the ‘mind’s eye’: two visual systems in one brain appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDr. Mark Lazenby reflects on Jahi McMath’s surgery gone wrongWhy do polar bear cubs (and babies) crawl backwards?Be Book Smart on National Reading Day

Related StoriesDr. Mark Lazenby reflects on Jahi McMath’s surgery gone wrongWhy do polar bear cubs (and babies) crawl backwards?Be Book Smart on National Reading Day

Locating in a ‘Silicon Valley’ does not guarantee success for tech firms

In China and Canada, Shenzhen and Waterloo share the same nickname. Both are frequently viewed as their country’s “Silicon Valley”. Despite this shared name, there are fundamental differences between the two, which can be illustrated by the development of their leading firms. Let’s use the local weather of the two cities as a metaphor to describe the current situation.

Mid-January 2014: it is snowy in Waterloo with a temperature of -3 oC. Blackberry, after laying off 4500 employees in recent months, is still struggling for survival. In contrast, Shenzhen is sunny with +15 oC. Huawei, one of its leading technology firms, continues to become stronger after doubling the size of its Ottawa research facility that is now linked to over 20 global research centers. As students of industrial clusters in China and Canada, we cannot resist asking what can be learned from the stories of these two telecom giants and how this maybe be related to their local-global structures?

Apparently, the global economy has been in a state of turbulence for quite some time and successes or failures of firms are “teetering on a knife edge”. On the one hand, industrial leaders can quickly lose their edge in innovation and vibrant regions can unexpectedly fall into stagnation. On the other hand, multinationals from emerging economies “rise like a phoenix” and make global competition less predictable. As a consequence, it is harder to tell where the next round of innovative ideas and new business practices will come from. And it becomes a huge challenge for business managers and regional policy-makers to foster successful innovation in an uncertain world.

A conventional solution to this challenge would be to locate in one of the most dynamic sites of the industry, especially a leading cluster with talented minds, innovative firms, and demanding customers. This would be a natural site because this is where one expects new ideas, technologies and solutions to be developed. For high-tech firms, the place to go to would thus be Silicon Valley. For fashion, it would be Paris or Milano; for finance, New York or London; for film-making, Hollywood; and for ceramic tiles, Emilia-Romagna.

It is true: these places are still the “Mecca” in their respective industries. But, in recent years, new innovative clusters have developed elsewhere — in both developed and developing economies. For example, in high-tech industries, the likes of Bangalore, Shenzhen, Hsinchu, Dallas, and Waterloo have all risen in the past 20 years. These clusters have grown out of varied contexts. New competitive firms from these regions have developed different understandings of industrial dynamics and accumulated different expertise in their fields. Driven by local innovators, many new industrial communities are being quickly transformed from knowledge-absorbing to knowledge-creating places. They are developing into new innovative clusters that are in the same general business, but have somewhat different areas of strengths and specialization. This is a novel trend that will have a distinct impact on the innovation strategies of firms, industries, and regions.

Although many innovations have local origins, it is crucial in this turbulent age not to rely blindly on localized learning networks in a community or cluster — no matter how successful these may have been in the past. It is more important to search, mobilize, and integrate new ideas, technologies, and knowledge scattered at a global scale, sometimes integrating very distant places. This does not imply that entrepreneurs need to be omnipresent because, in each technology field, knowledge pools are distributed quite unevenly, with a limited number of key locations spread around the globe. In each industry, a “small world” of remarkable hotspots or innovative clusters exist, which continuously improve existing technologies and sporadically generate innovations that redefine the “rules of the game” in a global business context. To gain a global competitive advantage, firms and clusters need to tap into such knowledge pools and become insiders in these places. This suggests that we are witnessing a process that generates novel patterns of foreign direct investment (FDI) linkages, a new structure of transnational knowledge flows, and perhaps a new organization of multinational corporations. We refer to this new architecture of globalized learning as “global cluster networks”.

Clusters as distinctive local industrial communities can be both places of opportunities and areas of challenges. Innovation-oriented firms often originate from successful clusters and already know how to interact in a creative environment. They will likely invest in similar clusters located elsewhere to benefit from the local learning milieus of these clusters. On the other hand, cost-squeezing firms may view clusters as places full of competitors, which drive up costs and risks of unintended knowledge spillovers, and consequently try to avoid such locations. We therefore expect that global cluster networks will develop around knowledge-based foreign direct investments (FDIs). In our study of 300 investment cases from Canada to China between 2006 and 2010, we find that firms from Canadian clusters are five times more likely to invest in similar Chinese clusters than firms from Canadian non-clusters.

Within cluster networks, knowledge does not flow in a linear way from one place to others, but is channeled in multi-directional ways among different sites – going back and forth involving feedback loops rather than simply spreading out. To leverage knowledge in global cluster networks, multinationals require both intra- and inter-organizational changes.

Internally, closer connections and interactions between subsidiaries and headquarters, as well as between different subsidiaries, become more significant for knowledge sharing and creation between clusters. Within multinational organizations, global training and learning infrastructures and transnational mobility of professionals become important strategic options. Beyond such arrangements, firms at the core of these networks need to turn into true learning organizations. According to Nohria and Ghoshal, these organizations operate as differentiated networks of global corporate units which are more automatous and horizontally linked, rather than bureaucratic hierarchies. In our analysis of FDI cluster networks between Canada and China, we find that most cluster-based investments are horizontally linked, as Canadian FDIs are generally engaged with similar kinds of activities in China, not exhibiting an international division of labor along global value chains.

Externally, the cluster subsidiaries of multinational firms become nodes in global cluster networks and take the lead in facilitating knowledge sharing processes between multinationals and local industrial communities. This is because they show both: geographical proximity with local competitors as well as organizational connections with distant units of the same multinational structure. Cluster-based FDI affiliates can tap into local knowledge pools, but also interact with the global organizational networks of their multinational corporations. Since learning is a mutual process, clusters also benefit from the existence of cross-cluster multinationals that create pipelines, channeling external knowledge into local communities.

At this point, we may ask whether the idea of global cluster networks can shed some light on the different situations that Blackberry and Huawei are currently facing. While both are complex cases, our conception indeed offers some relevant explanation to understand their recent development. Although Blackberry used to be very successful internationally, it was always quite a local firm. Its research and even production facilities are strongly concentrated around its Waterloo/Toronto headquarter region – i.e. a fact that has become the company’s pride. To find talented engineers outside the local community was difficult but did not appear crucial, as the supply of local talent from one of Canada’s leading tech universities was endless. Although there are many reasons for the decline of Blackberry, its isolation in a peripheral cluster, despite its initially highly innovative nature, contributed to growing bureaucracy and ignorance of fundamental changes in the smartphone industry.

Compared to Waterloo, Shenzhen is an IT cluster with a relatively weak local knowledge base, with no leading research university close-by. Turning this disadvantage into an advantage, Huawei adopted a global innovation strategy by establishing global research centers in many countries and thus tapping into varied knowledge pools. These centers are mostly located in innovative clusters. It is precisely the long-term engagement in such cluster networks that plays an important role for Huawei’s success: being already 20 years in Silicon Valley, 15 years in Bangalore and Dallas, and now 4 years in Ottawa. By being in major places of innovative ideas in the telecom world, Huawei has localized its research centers globally to match the strength of these embedded clusters. Through this, it has been able to integrate dynamic research nodes into a strong global knowledge network that constitutes the firm’s success – now and probably also in the future.

Harald Bathelt and Peng-Fei Li are the authors of the paper ‘Global cluster networks—foreign direct investment flows from Canada to China‘, published in the Journal of Economic Geography. This blog post first appeared on LSE’s USApp blog.

The aims of the Journal of Economic Geography are to redefine and reinvigorate the intersection between economics and geography, and to provide a world-class journal in the field. The journal is steered by a distinguished team of Editors and an Editorial Board, drawn equally from the two disciplines. It publishes original academic research and discussion of the highest scholarly standard in the field of ‘economic geography’ broadly defined.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Skyscrapers in the sun. By Serp77 via iStockphoto.

The post Locating in a ‘Silicon Valley’ does not guarantee success for tech firms appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRethinking European data protection lawProtecting children from hardcore adult content onlineGrowing up in a recession

Related StoriesRethinking European data protection lawProtecting children from hardcore adult content onlineGrowing up in a recession

January 29, 2014

Monthly gleanings for January 2014

Reference works: I received three questions.

(1) Our correspondent would like to buy a good etymological dictionary of English. Which one can be recommended?

(1) Our correspondent would like to buy a good etymological dictionary of English. Which one can be recommended?

Though outdated, still excellent is the great classic by Walter W. Skeat An Etymological Dictionary of the English Language. Despite its drawbacks, The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (a one-volume digest of the OED with some additions and corrections; edited by Charles T. Onions) is a mine of information. Much lighter in style and easier to read (“popular”) is Ernest Weekley’s An Etymological Dictionary of Modern English. Each of those three books will answer the basic questions about the origin of English words, but none gives references to the scholarly literature. Stay away from concise versions and the more recent books bearing titles like the ones above: they rehash (as a rule, uncritically) the material in the OED.

(2) Which are the best encyclopedias of medieval Scandinavia?

In the Scandinavian languages such books are many. If our correspondent can read Swedish or Norwegian or Danish, I’ll supply him with the necessary titles. In English the only comprehensive work of this type is Medieval Scandinavia: An Encyclopedia (Garland). Try also Historical Dictionary of the Vikings by Katherine Holman (2003) and Encyclopædia of the Viking Age by John Haywood (2000). Specialized encyclopedic and reference books on the myths and art of the so-called Viking Age are many.

(3) Dictionaries of Old French slang.

My work with argot seldom takes me beyond the time of Rabelais, and my knowledge of older French slang is limited. I constantly use the works by Lazar Sainéan (whose etymologies I admire but not always trust) and Pierre Guiraud (whose etymologies I also treat with caution). Several times I have consulted Lorédan Larchey’s Dictionnaire historique d’argot and André Stein’s L’écologie de l’argot ancien. I cannot judge how reliable they are. Most books I know are about the origin of modern French slang.

The digraph oa and a hoarse horse

Despite the warnings and rebukes I will persist in my heresy that today there is no reason to spell hoarse and horse differently. My conclusion has very little to do with the words’ history, which, incidentally, is clear only with regard to horse. Here are the basic facts. Horse goes back to Old Engl. hors, so that its modern vowel is pronounced according to expectation. By contrast, hoarse surfaced only in late Middle English, and its origin is obscure. Perhaps it came from Scandinavian, but confusion with some native form is obvious. Compare Dutch hees, German heiser, and Old Norse háss. Most Germanic cognates of hoarse, including the Old Norse one, have no r in it, while the only putative non-Germanic (Albanian) cognate is uncertain. German does have r but in a “wrong” place.

Numerous conjectures have been offered to explain the discrepancy. Perhaps hoarse is a blend of an r-less form and coarse or harsh (mere guesswork). Perhaps two variants competed even in the remote past. An etymologically impenetrable Gothic adjective has been cited, and a dubious Indo-European root set up. The solution of this problem is of no consequence for the present discussion because the earliest recorded English forms of hoarse were horse, hoors, and hoarse (see them in the OED). The spelling is ambiguous, and it is not clear how horse and hoarse were distinguished in Middle English, if at all. Though perhaps homonyms in the fourteenth century, they could have diverged in the sixteenth or the seventeenth (around the time of the colonization of America) and partly merged later. Medieval spelling is an insecure guide to pronunciation, and modern spelling is an insecure guide to history. The horse/hoarse merger is often compared with the marry/merry/Mary merger in many parts of the United States, but the two cases are not parallel, for marry, merry, and Mary have a well-documented history beginning with Old English, whereas hoarse does not. The fact that some people somewhere distinguished or distinguish horse and hoarse should not be allowed to tip the scale in the argument about spelling: one can usually find a conservative or an advanced dialect whose pronunciation differs from that of the majority of English speakers.

The digraph ea in read and its principal forms

The difference between reed and read does have the same cause as the difference between note and oat. There once were two long e’s (close and open), as there were two long o’s. But if I understood the question correctly, it was about the spelling of the past tense and the past participle of read: why also read, rather than red? In the preterit and the participle, the vowel stood before dd (long d) and was shortened in Middle English, but the spelling remained unchanged and reflects the pronunciation with long open e. A similar catastrophe occurred in many words with a formerly long vowel preceding two consonants (like long consonants, they made position for shortening), such as mean ~ meant, deal ~ dealt, and lead (verb) ~ lead (metal). After the shortening the digraph ea acquired two values. It now occurs in bread, dead, dread, head, tread, stead, meadow (typically before d), along with heat, bead, plead, mead. Students, following the example of read/read/read, cannot be persuaded that the past of lead is led (why should something be spelled rationally in English?), and countless innocent foreigners mispronounce the place name Reading and the name of its once famous gaol (jail). (To Masha Bell: No, I am not trying to find logic in modern spelling; I only explain why certain things look the way they do.)

Plural they with a singular antecedent

I think all of us have said on this subject everything we can at least twice but never budged. As is well-known, truth is not born in scholarly discussions. So let me formulate my thesis for the last time, and, if someone has anything new to say, I’ll be happy to be the recipient of the news. Here is my declaration of faith:

“Constructions of the type when a tenant has been evicted, it does not mean that they are a bad tenant and when a student comes, I never make them wait are recent and have been imposed on present day English to make it sound gender neutral. The process resulted in monstrosities of the type I have just quoted—another case of language planning (social engineering) that produced an unpalatable cure. I maintain that in the past no one ever, while describing a case of rape, would have said about the criminal (a man) that they escaped or about the victim (a woman) that they filed a report. No number of examples with someone, anyone, a person, and the like or with so-called distributive constructions having each in the antecedent will prove me wrong.”

I should add, again not for the first time, that American speakers who are thirty-five years old and younger have been taught to speak and write so and look upon such constructions as correct. The reformers have won, but I refuse to congratulate them. I would also like to repeat that no good newspaper and no author with a grain of self-respect uses such grammar. Unlike me, they rebel silently, by defying the trend, for fear of being classified with reactionaries. But I don’t believe that fighting silliness or evil is reactionary and will keep defending the fort even if I am alone to do so. And to quote my motto for the umpteenth time: “One does not always fight to win” (Rostand).

That any innovation moves from an epicenter and affects more and more strata as it spreads was known long before the birth of sociolinguistics. It is enough to look at the map of any important sound change (for instance, the German Consonant Shift or the voicing of initial f- and s- in English dialects) to come to this conclusion. The much-denigrated Neogrammarians taught that sound laws have no exceptions. We now know that the truth is more complex, but all etymology is based on their idea. Every time something goes wrong we are puzzled. The German cognate of Engl. to is zu, and this is the way it should be. But the Gothic cognate is du, with initial d- instead of t-, and no one knows why. Important sounding terms like “residual forms” (German Restformen) are a smoke screen invented to disguise our ignorance. Every exception has to be explained. It won’t do to say that, since on the map sound change progresses gradually, some words are “left behind,” like the children who failed to pass the test. Why doesn’t broad rhyme with road? There must have been a reason, but we don’t know it. The existing explanations are not too persuasive. Saying that broad just did not make it is no explanation at all.

Yes, Grendel’s name does have a sound symbolic or even sound imitating group gr-, even though the etymology of Grendel is debatable (several equally probable derivations have been offered). Grim and gruesome things happen around us; we are ground to dust and grieve. Grimalkins hiss, and greyhounds, contrary to expectation, bark like mythic hell dogs. Stephen Goranson’s antedating of gremlin is important. Although his find confirms the notion that the gremlin was initially a pilots’ demon, everybody believed that the word had originated during the war. As we now know, it only became truly popular during the blitzes.

The origin of the word pagoda

This subject is beyond my expertise, and I can only summarize our correspondent’s hypothesis and hope that some expert in Chinese etymology will comment on it. According to the letter writer, the word pagoda goes back to the well-known Pazhou Pagoda (traditional explanations are different). “The reply from a local Chinese person to a query about what that building is called would surely have been ‘Pazhouta’ and recorded by the curious foreigner as a ‘pagoda’.” The point of the hypothesis is that the word pagoda must have come directly from Chinese. Dictionaries give no support to this derivation, but they may be wrong. However, in light of the zh-g difference and the lack of historical documentation, the idea that the etymon of pagoda is a garbled version of Pazhouta may also be hard to prove.

From Scotland with unrequited love

I have received a letter from a correspondent who found my old post in which Dumfriesshire is said to be in south-central England. I don’t remember where this strange statement occurred and have no idea how it originated, but I hasten to tender my apologies and offer thanks for pointing out this horror to me. Once, in a book written by a Norwegian, I read that Oslo is in the west of Norway. An author’s life is full of inexplicable errors.

ATTENTION! Less than a month ago I had one of my traditional appearances on Minnesota Public Radio and received many interesting questions and suggestions. I’ll definitely answer them, but this post is already too long, so please wait for the next gleanings.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) W.W. Skeat from Notes on English etymology; chiefly reprinted from the Transactions of the Philological society (1901) via LibraryThing. (2) Old Nag by Vincent van Gogh. Public domain via Wikipaintings.

The post Monthly gleanings for January 2014 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe color gray in full bloomGray matter, part 3,or, going from dogs to cats and ghosts (grimalkins and gremlins)Whoa, or “the road we rode”

Related StoriesThe color gray in full bloomGray matter, part 3,or, going from dogs to cats and ghosts (grimalkins and gremlins)Whoa, or “the road we rode”

“Before he wrote it, he lived it”?

The James Bond brand has awesome power. When Agent 007 helped Queen Elizabeth II to parachute into the opening of the 2012 London Olympics, the world gasped (and then laughed) at the witty conjunction of two instantly recognizable icons of Britishness. There was an extra significance: the first fiction featuring James Bond, Casino Royale, came out in EIIR’s coronation year, 1953, and so through the dozen novels and two dozen lucrative films, the very patriotic (and ever youthful) Double Oh Seven has always been On Her Majesty’s Secret Service.

Tired cultural brands need refreshing, the marketing men in silly glasses say. We punters recognize the same-old, same-old names but want updates and new twists. Take the consulting detective Sherlock Holmes and his bromantic pal Dr. John Watson, for example, rebooted on the big screen, reinvented in television on both sides of the Atlantic, huge in China, and burgeoning in new versions at all points of the compass. You can play around with Holmes and Watson as you wish because Sir Arthur Conan Doyle died in 1930 and it’s free-for-all on his characters now. But you can’t mess with James Bond unless you own the franchise like Eon Productions and the Fleming family, because Ian Fleming died only fifty years ago in August 1964, and there are still two decades to run on his copyrights, which are litigiously protected. Meanwhile, the Bond film marque successfully refreshed itself in the 23rd Bond film Skyfall, with a new M, a new Q, a new Moneypenny, all ready for Bond 24 and 25, because, like the monarchy, the firm and the show must go on.

Tired cultural brands need refreshing, the marketing men in silly glasses say. We punters recognize the same-old, same-old names but want updates and new twists. Take the consulting detective Sherlock Holmes and his bromantic pal Dr. John Watson, for example, rebooted on the big screen, reinvented in television on both sides of the Atlantic, huge in China, and burgeoning in new versions at all points of the compass. You can play around with Holmes and Watson as you wish because Sir Arthur Conan Doyle died in 1930 and it’s free-for-all on his characters now. But you can’t mess with James Bond unless you own the franchise like Eon Productions and the Fleming family, because Ian Fleming died only fifty years ago in August 1964, and there are still two decades to run on his copyrights, which are litigiously protected. Meanwhile, the Bond film marque successfully refreshed itself in the 23rd Bond film Skyfall, with a new M, a new Q, a new Moneypenny, all ready for Bond 24 and 25, because, like the monarchy, the firm and the show must go on.

So how can someone else get a slice of the eager worldwide market for Bondian guns, girls and gadgets, free of copyright and licenses? Well, one idea is to focus on Ian Fleming himself, the man who wrote the James Bond books in the 1950s and early 60s, sourcing their excitements in what he did in the Second World War. The slogan for the new four-part series Fleming is: ‘Before he wrote it, he lived it.’ In other words, that Fleming was a kind of James Bond, in WW2.

There’s no doubt that the thriller-writer-to-be had an interesting war. Hand-picked at 30 to be the personal assistant to the Director of Naval Intelligence, Admiral John Godfrey (the basis of the fictional M), and wearing the dark blue uniform of an officer in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, Ian Fleming was at the heart of the secret world from 1939 to 1945. Fleming’s office — Room 39 at the Admiralty — looked across to the back of 10 Downing Street where Winston Churchill was defying Nazi domination. Section 17, where chain-smoking Commander Fleming signed his dockets ‘17F’, was the co-ordinating brain-box, ‘the bridge of the Naval Intelligence ship,’ and he was a good officer there. ‘His zeal, ability and judgment are altogether exceptional,’ wrote John Godfrey of his protégé in 1942, adding later: ‘Ian was a war-winner.’

In his job, Fleming liaised with most of Britain’s nine secret organizations of the Second World War, including the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), the Security Service (MI5), the sabotage and subversion people of the Special Operations Executive, as well as the hush-hush Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park. Fleming was ‘indoctrinated’ into the ULTRA secret of the interception and decrypting of enemy wireless signals very early in the war. He set up an ‘intelligence assault unit’ of naval officers and Royal Marines to ‘pinch’ code-books and new technology from the enemy, who saw their first action from an offshore destroyer during the ill-fated Dieppe Raid of 19 August 1942.

All this is terrific background for a future writer of spy-thrillers, but it has to be said that, apart from that day-trip to Dieppe, Fleming was not an agent or operative who ever went into the field himself. The yarn that he came top of a secret agents’ course at Camp X at Oshawa in Canada was invented by Sir William Stephenson in his anecdotage. Ian Fleming had bags of ideas, but he did not see action. He drove a desk, not a tank. He fired paper memos, not bullets.

It’s a problem for a four-part TV series like Fleming. The truth of his life as a wartime bureaucrat is actually quite boring, as most writers’ lives are boring. Their job is to pound out words on a keyboard, not to have adventures. Of course there are writers who do cut an active dash: Byron, Hemingway, Malraux, etc. (One thinks also of Beckett and Camus in the French Resistance.) But most writers are much closer to Walter Mitty than to men-at-arms, living more by the willed hallucinations of imagination than by their memories of machismo.

Dominic Cooper as Ian Fleming in Fleming. (c) BBC Worldwide Americas.

So Ian Fleming was never a James Bond. The books are his unbridled fantasies of what might have been. But television is a literal-minded medium, so Fleming reverse-engineers the process.

Ian Fleming, who looked like a broken-nosed Roman in life, is portrayed on screen by Dominic Cooper, who has the face of a decadent faun. The actor admits that Fleming has taken huge liberties. ‘There’s what [Ian Fleming] said he did, there’s what his biographers say he did, and then there’s what we say he did.’

‘Everything is based on something real,’ explains Fleming’s director Mat Whitecross, ‘but we have sexed it up at times. If you look at other versions of the biography, [Fleming] is deskbound, but that doesn’t make great drama. He didn’t have any fisticuffs with Nazis, but it felt like it would be better if he did.’

Nicholas Rankin is the author of Ian Fleming’s Commandos: The Story of the Legendary 30 Assault Unit which is publishing in paperback in March.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Grave and memorial to Ian Fleming at Sevenhampton, Wiltshire. Photo by Mervyn. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post “Before he wrote it, he lived it”? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA postcard from Pete SeegerIn memoriam: Pete SeegerInternational Holocaust Remembrance Day reading list

Related StoriesA postcard from Pete SeegerIn memoriam: Pete SeegerInternational Holocaust Remembrance Day reading list

A world in fear [infographic]

For billions around the world, poverty translates not only into a struggle for food, shelter, health, and education. No, poverty exposes them to a vast spectrum of human rights abuses on a daily basis. Safety and freedom from fear do not exist for those living in underdeveloped areas. Ill-equipped judicial systems, under-trained and corrupt law enforcement agencies, and despotic housing complexes are just a few of the challenges the impoverished face. Violence spreads with impunity, devouring families and communities that have no means to protect themselves. In The Locust Effect: Why the End of Poverty Requires the End of Violence, Gary A. Haugen and Victor Boutros explore the virulent power that violence takes on in developing parts of the world where extreme poverty prevails. In the infographic below, take a journey through the often unheard of tribulations and fears a large portion of the world population is vulnerable to as a result of poverty.

Download a jpg or pdf of the infographic.

Gary A. Haugen and Victor Boutros are co-authors of The Locust Effect: Why the End of Poverty Requires the End of Violence. Gary Haugen is the founder and president of International Justice Mission, a global human rights agency that protects the poor from violence. The largest organization of its kind, IJM has partnered with law enforcement to rescue thousands of victims of violence. Victor Boutros is a federal prosecutor who investigates and tries nationally significant cases of police misconduct, hate crimes, and international human trafficking around the country on behalf of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A world in fear [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGetting back in Blackstone’s gameRethinking European data protection lawProtecting children from hardcore adult content online

Related StoriesGetting back in Blackstone’s gameRethinking European data protection lawProtecting children from hardcore adult content online

Hal Gladfelder on The Beggar’s Opera and Polly

The Beggar’s Opera, written in 1728 by John Gay, is the story of Peachum, a fence and thief-catcher, and his family. His daughter, Polly, has married the highwayman Macheath, and the diapproving Peachum sets out to try and kill Macheath and regain his use of Polly for his dubious business. With this work, Gay invented a new form, the ballad opera, and the daring mixture of caustic political satire, well-loved popular tunes, and a story of crime and betrayal set in the urban underworld of prostitutes and thieves was an overnight sensation.

A scene from The Beggar’s Opera painted by William Hogarth [public domain]

In this podcast, Hal Gladfelder discusses Gay’s career, the plot of The Beggar’s Opera and the sequel Polly, the reaction of Robert Walpole to his being satirized in the play, and the work’s enduring success.Hal Gladfelder is Senior Lecturer in Eighteenth-Century English Literature and Culture at the University of Manchester. His books include Criminality and Narrative in Eighteenth-Century England: Beyond the Law (2001) and Fanny Hill in Bombay: The Making and Unmaking of John Cleland (2012), as well as the Broadview edition of Cleland’s Memoirs of a Coxcomb (2005) and the Oxford World’s Classics edition of John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera and Polly (2013). He has also written for OUPblog about The Beggar’s Opera as the first jukebox musical.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog. Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: A scene from The Beggar’s Opera, by William Hogarth [public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Hal Gladfelder on The Beggar’s Opera and Polly appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Banks O’ DoonChristmas quotations from Oxford World’s ClassicsComposer Martin Butler in 10 questions

Related StoriesThe Banks O’ DoonChristmas quotations from Oxford World’s ClassicsComposer Martin Butler in 10 questions

January 28, 2014

A postcard from Pete Seeger

I am saddened to learn of the passing of American folk musician Pete Seeger and am not sure how to sum up his life in a short space. I am just thinking: the world weeps. So I’d like to share the postcard I just got from him. It sums up his life, always caring and studying and thinking.

Sonnet 65 (from Oxford Scholarly Editions Online)

Since brass, nor stone, nor earth, nor boundless sea,

But sad mortality o’ersways their power,

How with this rage shall beauty hold a plea,

Whose action is no stronger than a flower?

how shall summer’s honey breath hold out

Against the wrackful siege of batt’ring days,

When rocks impregnable are not so stout,

Nor gates of steel so strong, but time decays?

O fearful meditation; where, alack,

Shall Time’s best jewel from Time’s chest lie hid?

Or what strong hand can hold his swift foot back,

Or who his spoil of beauty can forbid?

O none, unless this miracle have might,

That in black ink my love may still shine bright.

Ronald Cohen is Professor Emeritus of History Indiana University Northwest, and author of A History of Folk Music Festivals in the United States: Feasts of Musical Celebration (Scarecrow, 2008), Folk Music: The Basics (Routledge, 2006) and Rainbow Quest: The Folk Music Revival and American Society, 1940-1970 (Massachusetts, 2002). He is the co-editor of The Pete Seeger Reader with James Capaldi.

The post A postcard from Pete Seeger appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIn memoriam: Pete SeegerWhy do polar bear cubs (and babies) crawl backwards?Composer Martin Butler in 10 questions

Related StoriesIn memoriam: Pete SeegerWhy do polar bear cubs (and babies) crawl backwards?Composer Martin Butler in 10 questions

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers