Oxford University Press's Blog, page 861

December 25, 2013

Oxford University Press holiday trimmings around the globe

Season’s Greetings from Oxford University Press! Here’s some holiday decorations from our different offices around the world, including a great book ‘Christmas tree’ from our Australian colleagues, some ‘green’ decorations in the South Africa branch (all hand made!), and some festive trimmings in Oxford and New York.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Oxford, UK

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Lizzie Shannon-Little.

Oxford, UK

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Lizzie Shannon-Little.

Oxford, UK

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Lizzie Shannon-Little.

New York, USA

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Alana Podolsky.

New York, USA

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Alana Podolsky.

New York, USA

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Alyssa Bender

New York, USA

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Brianna Cuccinello

New York, USA

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Cherie Hackelberg

New York, USA

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Cherie Hackelberg

New York, USA

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Cherie Hackelberg

New York, USA

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Cherie Hackelberg

New York, USA

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Cherie Hackelberg

New York, USA

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Christina Lee

Cary, NC, USA

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Kimberly Taft.

Cary, NC, USA

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Kimberly Taft.

Cary, NC, USA

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Kimberly Taft.

Melbourne, Australia

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Nicola Weideling

Cape Town, South Africa

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Lee-Anne Abrahamse.

Cape Town, South Africa

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Lee-Anne Abrahamse.

Cape Town, South Africa

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Lee-Anne Abrahamse.

Cape Town, South Africa

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Lee-Anne Abrahamse.

Cape Town, South Africa

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Lee-Anne Abrahamse.

Cape Town, South Africa

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Lee-Anne Abrahamse.

Cape Town, South Africa

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Lee-Anne Abrahamse.

Cape Town, South Africa

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Lee-Anne Abrahamse.

Cape Town, South Africa

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Lee-Anne Abrahamse.

Cape Town, South Africa

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Lee-Anne Abrahamse.

Cape Town, South Africa

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Lee-Anne Abrahamse.

Cape Town, South Africa

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Lee-Anne Abrahamse.

Cape Town, South Africa

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Lee-Anne Abrahamse.

Cape Town, South Africa

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Lee-Anne Abrahamse.

Cape Town, South Africa

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Lee-Anne Abrahamse.

Cape Town, South Africa

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photo by Lee-Anne Abrahamse.

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Oxford University Press holiday trimmings around the globe appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOxford Music in 2013: A look backA year in Very Short Introductions: 2013Holiday party conversation starters from OUP

Related StoriesOxford Music in 2013: A look backA year in Very Short Introductions: 2013Holiday party conversation starters from OUP

Christmas quotations from Oxford World’s Classics

By Kirsty Doole

Everyone at Oxford World’s Classics wishes you a very Merry Christmas. Here are a few of our favourite seasonal quotations.

“Christmas was close at hand, in all his bluff and hearty honesty; it was the season of hospitality, merriment, and open-heartedness; the old year was preparing, like an ancient philosopher, to call his friends around him, and amidst the sound of feasting and revelry to pass gently and calmly away.” – The Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens

“‘Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents,’ grumbled Jo, lying on the rug.” – Little Women by Louisa M. Alcott

“I sincerely hope your Christmas in Hertfordshire may abound in the gaieties which that season generally brings, and that your beaux will be so numerous as to prevent your feeling the loss of the three of whom we shall deprive you.” – Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

“At Christmas I no more desire a rose

Than wish a snow in May’s new-fangled shows;

But like of each thing that in season grows.” – Love’s Labour’s Lost by William Shakespeare

“For it is good to be children sometimes, and never better than at Christmas, when its mighty Founder was a child himself.” — A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens

“Whenever five or six English-speaking people meet round a fire on Christmas Eve, they start telling each other ghost stories.” – Jerome K. Jerome, author of Three Men in a Boat

“Humpbacked Father Christmas then made a complete entry, swinging his huge club, and in a general way clearing the stage for the actors proper, while he informed the company in smart verse that he was come, welcome or welcome not; concluding his speech with:

‘Make room, make room, my gallant boys,

And give us space to rhyme;

We’ve come to show Saint George’s play,

Upon this Christmas time.’” – The Return of the Native by Thomas Hardy

‘A Merry Christmas to us all, my dears. God bless us!’ Which all the family re-echoed.

‘God bless us every one!’ said Tiny Tim, the last of all. – A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens

Kirsty Doole is Publicity Manager for Oxford World’s Classics.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog. Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Scrooge’s third visitor. By John Leech [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Christmas quotations from Oxford World’s Classics appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAn Oxford World’s Classics American literature reading listA Scottish reading list from Oxford World’s ClassicsRemembering Frank Norris

Related StoriesAn Oxford World’s Classics American literature reading listA Scottish reading list from Oxford World’s ClassicsRemembering Frank Norris

December 24, 2013

Speaking of India…

In one way or another, the question ‘How is India Doing?’ has been one of great interest down the decades, and not only from the mid-1980s when Amartya Sen wrote an article, with that title, in the New York Review of Books.

The last couple of years have seen the emergence of two books (primarily) on India’s economic and social development, by Jean Dreze and Amartya Sen (An Uncertain Glory: India and its Contradictions: Princeton University Press 2013) and Jagdish Bhagwati and Arvind Panagariya (India’s Tryst with Destiny: Collins Business 2012). Also of recent vintage is Ramachandra Guha’s work of modern history India After Gandhi (Harper Collins 2007). Another major event in scholarly accounts of India is Sunil Khilnani’s The Idea of India (Farrar, Straus and Giroux: 1998); and at least two notable assessments of India, since, have been the books by Satish Deshpande (Contemporary India: A Sociological View: Viking Penguin 2003) and Badri Raina (The Underside of Things: India and the World, A Citizen’s Miscellany, 2006-2011: Three Essays Collective 2012). Interest in post-Independence India – possibly with a long time-lag – was triggered by an early masterly work of humorous fiction, G. V. Desani’s classic All About H. Hatterr (Aldor Press: 1948), which was subsequently to be matched, if at all, only by Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children (Jonathan Cape: 1980).

The books mentioned above represent only a smattering of work on the subject of India. Small though the sample is, it brings into relief the wide variety of approaches to, and perspectives on, the subject which marks this genre of work. Many studies are governed by a disciplinary orientation, ranging over economics and sociology and history and political science. Others are non-academic, or less than explicitly academic, traversing the territories of fiction and belles-lettres and the essay. Some are adulatory of their subject, others fiercely critical, and yet others of the fence-sitting variety.

The fascination with India has, in recent times, been fuelled especially by a perception of remarkable economic performance by the country. The basis for this judgment has resided mainly in the story of India’s growth in per capita national income (a story that has now begun to unravel), and in the allegedly remarkable decline in income-poverty (which has triggered fierce battles on the appropriate way of measuring money-metric deprivation). These aspects of material advancement, at least for a subset of the country’s citizens, has been accompanied by increasingly self-conscious (not to say convoluted) scholarly deliberation on various phenomena that have presided over India’s recent development experience: liberalization, globalization, post-coloniality, secularism, ‘minorityism’, ‘Non-Resident Indianism’, caste, corruption,…

While the West watches with a mixture of apprehension and anticipation (triggered respectively by India’s seeming emergence into economic consolidation and the prospect of a large and friendly market for the West’s goods and services), elite and upper-middle-class India marches on with what one could, from a certain perspective, view as increasing levels of assertive self-confidence, stridency, selfishness, and outright hubris. To the vast assortment of treatments of India already available, it is inevitable that parody should be waiting just round the corner — parody, let it be said, that is fuelled by involvement in and love of country, rather than by petulance toward it.

The elements of such a parody might be expected to cover the subjects of India’s obsession with cricket, its upper crust’s dreams of emerging as a super-power, the ambitions and moral ethos of its middle classes, and the incomprehensibly intricate scholarly excesses of India’s deconstruction. Together, these elements might be expected to add up to what G. V. Desani, in a pre-Introduction passage from All About H. Haterr, referred to as a ‘gesture’:

Indian middle-man (to Author): Sir, if you do not identify your composition a novel, how then do we itemise it? Sir, the rank and file is entitled to know.

Author (to Indian middle-man): Sir, I identify it a gesture. Sir, the rank and file is entitled to know.

Indian middle-man (to Author): Sir, there is no immediate demand for gestures. There is immediate demand for novels. Sir, we are literary agents not free agents.

Author (to Indian middle-man): Sir, I identify it a novel. Sir, itemise it accordingly.

Desani had the advantage that All About H. Hatterr was a novel, apart from the fact that he was a great writer. Other literary gestures might prove much harder to classify, other than as gestures, pure and simple. As Desani observed, one problem with gestures is that they don’t necessarily have a great demand curve facing them — unless, of course, ‘India-watchers’, academic scholars, politically motivated readers, and people with a taste for parody should band together to falsify the proposition.

S. Subramanian is an economist, and was, until recently, a professor at the Madras Institute of Development Studies in Chennai, India. A National Fellow of the Indian Council of Social Science Research, he is the author of Economic Offences: A Compendium of Crimes in Prose and Verse.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Bundi, India, December 3, 2012: A senior Indian man with white hair and mustache, wearing a white shirt, is sitting in his bookstore looking to the camera. © isabel tiessen pastor via iStockphoto.

The post Speaking of India… appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGoogle Books is fair useFrom radio to YouTubeTranslation and subjectivity: the classical model

Related StoriesGoogle Books is fair useFrom radio to YouTubeTranslation and subjectivity: the classical model

Translation and subjectivity: the classical model

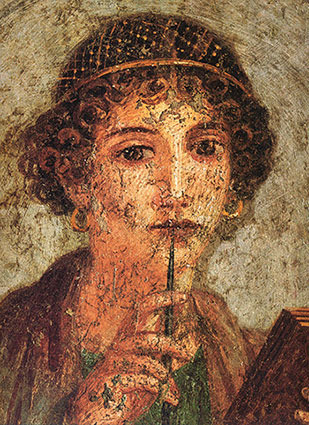

‘Sappho’ fresco from Pompeii. Public Domain via Wikipedia Commons.

At a British Centre for Literary Translation Seminar held jointly with Northampton Library Services some years ago, one of the participating librarians recounted his first encounter with the vagaries of translation; having fallen in love with a black Penguin version of Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot as a student, he had eagerly purchased a new version when it had recently been republished. But dipping in to the book, he quickly became perplexed. Now he could barely recognize the novel he had once so much enjoyed. As he soon realized, it had been retranslated by a different, new translator into a different, new English.The assumption that translation might be static, a ‘correct’ version which has passed, without pollution, through its translator from one language to another, is perhaps hardly surprising. Ignoring Francis William Newman’s caveat against presenting a translation as the original text, Anglophone publishing conventions often exclude translator’s names from the front cover of literary works, particularly those of the established western canon. In such editions, translator’s prefaces rarely refer to their own approaches and strategies in approaching their source text; for instance, Richmond Lattimore’s iconic 1965 version of the Odyssey includes 23 pages for his discussion of the text and four lines for his “Note on the Translation”. His fellow Homeric translator Robert Fagels is more blunt, noting in the introduction to his 1996 Odyssey that any sort of translator statement is “a risky business…petards that will probably hoist the writer later”.

But for translators themselves, a subjective approach to the text is often not only inevitable but essential. Readers, Carol Maier observed wryly, might regard translation as a task “that does not occur in the realms of thought but between the pages of a dictionary” (even if, as radical Catullus translator Louis Zukofsky pointed out, “the trouble with the dictionary is that it keeps changing the subject”). But to translators it is a form of writing offering its own pleasures and triumphs. For Lisa Rose Bradford, the translator of contemporary Argentine poet Juan Gelman, her work represents “a regeneration of delight and a grafting of cultures”.

This is particularly the case for classical translators, working with dead languages, defunct literary forms, and, most tricky of all, incomplete texts. Here, the issue is often not how but what to translate. For example, when working on my 1996 volume Classical Women Poets, I had to create my own large scale copy of the disputed and tattered text of Erinna’s “Distaff”, unearthed in Egypt in 1928, with each scholar’s emendations and new readings represented by a different colour shading. In the case of Sappho’s fragments, issues of translation and framing become more tricky; how to represent a few isolated lines or words or even a string of isolated letters as poetry for a contemporary audience? In her influential 2002 volume If Not, Winter, Canadian poet and classicist Anne Carson adopted an uncompromising approach, mirroring the fragmentation of the Greek as it appears on the texts. Nevertheless, even this “literal” rendering is highly artificial; Carson often misses out lines and letters while at the same time she sprinkles the page with square brackets to represent even more lacunae than are present in the Greek.

In my 1984/1992 volume Sappho: Poems & Fragments, my aim was to allow the framing of the translations within a volume to become a creative strategy in itself. I grouped small pieces together, regardless of their position in modern Greek textual editions which are themselves a construct of modern scholarship. For example, the fragments traditionally numbered 51 and 36, which have both survived in short quotations from much later commentators, were reordered together in my new version as follows:

I don’t know what to do –

I’m torn in two

*****

I desire and yearn

[for you]

Such interventions allowed disparate fragments to interact with each other in new ways, suggesting hidden narratives within the text, presenting these often baffling pieces afresh to a new, contemporary readership. At the same time, in order to maintain the integrity of the texts themselves, like Anne Carson, I also utilised the typography of scholarship to clarify, through poem numberings and asterisk breaks, that these were still to be considered separate pieces.

In addition to this policy of juxtaposition, I then recontextualized the fragments within the book by grouping them together by subject, here in a section I entitled “Despair”. This was, of course, pure speculation; with Sappho’s own poetic vision now lost to us forever, the reordering and regrouping of her fragments within these emotive section headings represent my own subjective interaction with the text. For André Lefevere, such framing is part of a work’s system of “patronage”, which aims to “regulate the relationship between the literary system and other systems, which together make up … a culture”.

If such clearly subjective responses to the text might not meet the approval of all, they undoubtedly provide a means to address the complex textual and cultural issues faced by classical translators. These, in turn, can lead to new, creative engagements with a chosen source, reimagining — and above all reanimating — an ancient text for a new contemporary audience, whether through translation, free versioning or the writing of new, original poems based around it.

In the end perhaps all that matters is the quality of the work. “A translator must know one language well,” Donald Carne-Ross advised a hesitant Christopher Logue as he embarked on his life’s work of Homeric versioning. “Preferably his own.”

Josephine Balmer is a poet, translator, and research scholar. Her study, Piecing Together the Fragments: Translating Classical Verse, Creating Contemporary Poetry, is published by OUP. Her latest collection, The Word for Sorrow, based around Ovid’s Tristia, is published by Salt.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Translation and subjectivity: the classical model appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGreeks and Romans: literary influence across languages and ethnicitiesScenes from The Iliad in ancient artGods and mythological creatures in The Iliad in Ancient art

Related StoriesGreeks and Romans: literary influence across languages and ethnicitiesScenes from The Iliad in ancient artGods and mythological creatures in The Iliad in Ancient art

Bill Bratton on both coasts

Inspired by a chapter on policing by leading criminologists Jeffrey Fagan (Columbia University) and John McDonald (University of Pennsylvania), the editors of the recently published volume New York and Los Angeles: The Uncertain Future, David Halle and Andrew A. Beveridge, along with Sydney Beveridge, take a closer look at the consequences of the recent New York mayoral race.

By David Halle, Andy Beveridge, and Sydney Beveridge

Incoming New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio has just chosen Bill Bratton as the city’s Police Commissioner. Bratton returns to the top post he occupied from 1994 to 1996 where he played a critical role in police reform in New York, and then as Los Angeles Police Commissioner from 2002 to 2009. Bratton’s stint in Los Angeles is a key reason why community-police relations there seem in better shape than New York’s. Bratton achieved this in Los Angeles while also presiding over a massive drop in crime. It is this apparent ability both to reduce crime and improve community-police relations that will now be tested in New York where outgoing mayor Bloomberg and Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly argue that their Stop and Frisk policy, which critics argue has alienated many in the black and Latino community, is vital for keeping crime low.

How did Bratton get his Los Angeles results? For sure the reasons that crime has plummeted in both cities to levels not seen since the early 1960s are a complex mix, from changing police tactics to long-term demographic shifts to the ebbs and flows of drug epidemics. Still, Bratton introduced the famous COMPSTAT program in interestingly different forms in both cities, and this is one key reason for the differences in community-police relations. COMPSTAT uses geographical mapping of crime to make strategic decisions about officer deployment, and sets police division benchmarks for crime reduction. Under the NYPD version of COMPSTAT, each division captain was basically responsible for crime trends and for formulating a response in his or her police area. Performance was noted in monthly, central command staff meetings, but what was noted was primarily crime trends, and how to deal with these was left to local commanders.

When Bratton was appointed LAPD police chief in 2002, he instituted COMPSTAT Plus (i.e. the LA version). This created a centralized audit team of LAPD commanders, who then worked with each local police division to develop its own strategic plan to meet crime reduction goals. This was a sea change for the LAPD and also for COMPSTAT. Previous LAPD approaches to reducing crime, dating back to the 1960s Parker administration, relied on sending specialized units and tactical responses to local divisions. Never before had reducing crime focused on a locally based, community-wide approach that relied primarily on line-officers and command staff, in consultation with a central audit division. Los Angeles witnessed a significant reduction in crime rates after the implementation of COMSTAT Plus, as New York had under the original COMPSTAT (i.e. the version without a central audit), but the LAPD’s central audit version injected a concern for local police-community relations since Bratton has long been an enthusiast of the “Broken Windows” theory of crime that argues that police should focus not just on serious crime but on the quality of neighborhood life including police-community relations. The claim is that in so doing serious crime will anyway be reduced. In implementing COMPSTAT Plus Bratton clearly felt that local commanders could not be trusted to implement a crime reduction program, including Broken Windows, without central intervention.

A second, highly relevant difference between the two cities has to do with the monitoring of consent decrees, which also revolves around variations in central monitoring, though in this case from the courts. The quality of police-community relations has long been a key issue in both cities, and accusations of unconstitutional policing have resulted in major civil litigation, with both cities operating under consent decrees. Still, as Fagan and MacDonald argue, a key reason the NYPD seems to have reduced abuses less under the consent decree than its LA counterpart is that the NYPD, unlike the LAPD, was not subject to court-ordered monitoring of its behavior during this period. In 2009, Los Angeles emerged from nine years under a consent decree. In lifting the decree, the US District Court Judge noted: “The LAPD has become the national and international policing standard for activities that range from audits to handling of the mentally ill to many aspects of training to risk assessment of police officers and more.” The LAPD has entered into new partnerships with various community organizations, and in recent polls nearly eight percent of LA residents expressed strong approval for the performance of the department. Remarkably, this included 76 percent and 68 percent of the black and Latino respondents, respectively.

New York City, by contrast, emerged from the Daniels civil legislation and consent decree from 2003 to 2007, which did not involve court-ordered monitoring of the NYPD’s behavior. The NYPD became immediately mired in three new lawsuits alleging racial discrimination and a pattern of unconstitutional street stops. The NYPD has intensified its spectrum of Order Maintenance Policing tactics, including trespass enforcement in public housing, street stops (also known as “Stop and Frisk”), and misdemeanor marijuana enforcement. All three approaches have led to litigation against the NYPD. The divided response of the City’s diverse communities to the Stop and Frisk program, the centerpiece of the NYPD strategy, shows the depth of the breech between citizens and police along racial lines. In a recent poll, white voters approved 59 to 36 percent, while disapproval was 68 to 27 percent among black voters and 52 to 43 percent among Hispanic voters.

Bill Bratton, 24 April 2012. Photo by Policy Exchange. CC 2.0 via Flickr.

Bill de Blasio made criticism of Stop and Frisk a centerpiece of his mayoral campaign, and had nothing positive to say about the practice. Interestingly, Bratton now insists that Stop and Frisk is integral to effective policing. He says he will not abandon the policy, but operate it in a manner more respectful of blacks and Latinos and more often in white neighborhoods than under Commissioner Kelly/Mayor Bloomberg. He has not said so, but it seems likely that NYPD police behavior will be centrally monitored under Bratton to a far greater extent than it has been. The challenge, of course, is to keep New York’s crime rate low while reducing the widespread hatred of the police among black residents especially. We will see what new COMPSTAT and other initiatives he implements in that effort, perhaps setting precedents for policing in cities nationwide.

A second challenge facing Bratton is getting on with his new boss. Bratton’s first stint as New York’s Commissioner ended when mayor Giuliani fired Bratton out of jealousy because Bratton appeared on the cover of Time magazine for his achievements in reducing New York crime. Bratton and Giuliani both have notoriously large egos. Still, de Blasio’s tolerance here remains to be tested.

In New York and Los Angeles: The Uncertain Future, Fagan and McDonald conclude their chapter by writing, “Many citizens in New York City, including those most heavily policed, await the next mayor and police commissioner to see whether a new era of reform can begin that includes citizen trust and satisfaction as an outcome as equally worthy of addressing as the crime rate.” Hold on for a fascinating ride.

David Halle is Professor of Sociology at the University of California, Los Angeles. He is also an adjunct professor at the City University of New York’s Graduate Center and the author of America’s Working Man: Work, Home, and Politics among Blue-Collar Property Owners and Inside Culture: Art and Class in the American Home. Andrew A. Beveridge is Professor of Sociology at Queens College and the Graduate School and University Center of the City University of New York. Sydney Beveridge is Media and Content Editor at Social Explorer, Inc.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Bill Bratton on both coasts appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA Nelson Mandela reading listBest international law books of 2013Google Books is fair use

Related StoriesA Nelson Mandela reading listBest international law books of 2013Google Books is fair use

Oxford Music in 2013: A look back

It’s been a busy year at OUP Music! Before 2013 comes to a close, we thought we would take a look back at the highlights of another year gone by.

January

Oxford Music announced the first Grove Music Online Mountweazel Contest! The winner, Maurizio Papa (a.k.a. Keith Clifton) submitted a fake article, “Del Marinar, Stella,” which was posted for April Fool’s.

February

Oxford’s Academic division (which we fall under) launched its Tumblr! Music, of course, features prominently throughout. Our most recent music posts include Frank Sinatra’s birthday, temperance songs, and a book gift guide.

Early Music celebrated its 40th anniversary this year with a special anniversary issue.

March

Bob Chilcott’s St John Passion was premiered at Wells Cathedral by the Cathedral Choir, and was directed by Matthew Owens.

OUP Composer, Michael Berkeley, was introduced to the House of Lords on the 26th of March as Lord Berkeley of Knighton, CBE. He now sits on the cross benches as a non-party political peer. Michael is a passionate advocate for the arts, contemporary music, and music education. The appointment, which was approved by the Queen, was made by the Prime Minister on the recommendation of the House of Lords Appointments Commission.

Michael’s much lauded maiden speech can be read in Hansard (see subheading ’14 May 2013: Column 284′) or watched on Parliament Live TV (spool through to timecode 15:53:51).

April

Oxford Music Online was named a Webby Award Honoree for excellence in the category of Best Writing (editorial).

The New York office gathered to listen to Grove Music Online Assistant Editor Meg Wilhoite perform a piano recital in the lobby.

May

OUP-ers Annie Leyman and Helen Boyd went to the Parliamentary Jazz Awards at the Houses of Parliament in London, where an OUP author, Catherine Tackley, won Jazz Publication of the Year.

May saw the inaugural performance of the Grove Trio, made up of Anna-Lise Santella, Jessica Barbour, and Meghann Wilhoite. What talented staff we have!

June

Griselda Sherlaw-Johnson and Robyn were thrilled to attend the Service to mark the 60th anniversary of HRH Queen Elizabeth’s Coronation service at Westminster Abbey. Bob Chilcott’s The King Shall Rejoice was commissioned and premiered at the service.

Griselda Sherlaw-Johnson and Robyn were thrilled to attend the Service to mark the 60th anniversary of HRH Queen Elizabeth’s Coronation service at Westminster Abbey. Bob Chilcott’s The King Shall Rejoice was commissioned and premiered at the service.

Our Twitter — @OUPMusic — turned one year old.

July

The Royal Baby was born! Oxford celebrated with numerous blog posts, including this post about lullabies for Prince George.

August

@OUPMusic Twitter hit 2,249 followers on the first of August!

September

The Internet became alive with the sound of music in September when seven very musical Very Short Introductions (VSIs) were made available online, with the newest and eighth title, Ethnomusicology, making its way online in December. Titles range from The Blues and Film Music, to The Orchestra and Folk Music, with universities, libraries, and schools able to subscribe. Did you know the history of blues as a broadly popular style of music began in 1912, when W. C. Handy’s “Memphis Blues”—along with two similar songs—sparked a national craze?

Renowned composer, Anthony Payne, was commissioned by the BBC to orchestrate Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Four Last Songs for a world premiere at the 2013 Proms on 4 September. The work was performed by the BBC Symphony Orchestra, Osmo Vänskä (conductor), and Jennifer Johnston (mezzo-soprano).

October

An article from The Musical Quarterly “Bayreuth in Miniature: Wagner and the Melodramatic Voice” by David Trippett won the ASCAP Foundation Deems Taylor Award for excellence.

November

The highly-anticipated second edition of The Grove Dictionary of American Music is here! And featured in The New York Times.

Grove editorial board member Philip V. Bohlman was awarded the Jaap Kunst Prize at the annual meeting of the Society for Ethnomusicology for “Analysing Aporia” (Twentieth-Century Music, vol. 8, no. 2, 2011) for the “most significant article in ethnomusicology written by a member of the Society and published in the previous year.”

December

To celebrate the holidays, OUP author Constance Valis Hill (Tap Dancing America: A Cultural History, Brotherhood in Rhythm: The Jazz Tap Dancing of the Nicholas Brothers), and Tony Waag, Artistic Director of the American Tap Dance Foundation, along with the Tap Addicts adult dance ensemble, performed in the New York lobby.

To celebrate the wonderful year that was, music journals have given free access to the most read articles from each journal in 2013. Available for a limited time!

Early Music, “Early Music and Web 2.0” by Elizabeth Eva Leach

Music & Letters, “The Other in the Mirror, or Recognizing the Self: Wilde’s and Zemlinsky’s Dwarf” by Sherry D. Lee

The Musical Quarterly, “ Bayreuth in Miniature: Wagner and the Melodramatic Voice ” by David Trippett

The Opera Quarterly, “(De) Translating Mozart: The Magic Flute in 1909 Paris” by William Gibbons

And last but certainly not least, we are looking forward to 2014 when we welcome Music Theory Spectrum, Music Therapy Perspectives, and Journal of Music Therapy to Oxford University Press!

Victoria Davis is an Online Marketing Coordinator at Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Oxford Music in 2013: A look back appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSir John Tavener, saintly and controversial composerAn interview with marimbist Kai StensgaardAnd the Grammy goes to…

Related StoriesSir John Tavener, saintly and controversial composerAn interview with marimbist Kai StensgaardAnd the Grammy goes to…

December 23, 2013

Imagination and reason

“By reason and logic we die hourly, by imagination we live!” wrote W.B. Yeats, thus resurrecting an age-old dichotomy between our ability to make sense of the world around us and our ability to see beyond what meets the eye. A belief in this dualism informs much thinking on imagination, which is often pitted against what is real. Jean-Paul Sartre had a different way of seeing things. Imagination, he thought, had a critical role to play in the human psyche. His first well-known book, Being and Nothingness, was a philosophical treatise based on his fascination with the world as it is and its relationship to that which is not, but which may also yet be, what he termed the ‘not-yet-real.’

Imagination is in fact the life blood of one of the most fundamental human inclinations — that of storytelling. We tell stories all the time, about everything, to everyone, including ourselves. What we tell and why and how we tell it are strongly influenced by the contexts in which we as narrators operate. But one only needs to think for a moment of what it would mean to have no story to tell, or to have forgotten one’s story — as depicted in some of the wonderfully rich books by Oliver Sachs — to realize that we organize our relationship to those around us, to the world, and indeed to our very selves via narrative.

Narrative and imagination are integrally tied to one another; that they are so is immediately clear to anyone who stops to think about stories — real and imagined, about the past or in a promised, or feared, future. Why and how this is so are questions that direct us to ruminate on what it means to be human. Narrative and imagination are combined, not only in our most elevated thoughts about the world as it might be, but also in the very minutiae of our daily lives. Although we do not often talk about the role of imagination in how we approach each day, carrying out and evading those responsibilities to which we have committed ourselves, and simply being ourselves in the world, negotiating our sometimes troubled paths between competing desires of our own and those of others, its importance cannot be overstated. Sartre argued that our freedom to act in the world is a function of our ability to see not only what is before us, but alternative futures. Writing about Sartre’s work, Mary Warnock comments: the power to see things in different ways and to form images about a so far non-existent future, is identical with the power of imagination (Warnock 1972:xvii). Thus imagination is not antithetical to being able to perceive that which is ‘real’ but rather an extension of it, the scaffolding which underlies our efforts to build a different world.

Molly Andrews is Professor of Political Psychology, and Co-director of the Centre for Narrative Research at the University of East London. Listen to an interview about her newest book, Narrative Imagination and Everyday Life.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Luxor, United Arab Republic: Famed French author Jean-Paul Sartre poses beside an ancient Egyptian statue as he toured the antiquities of Luxor during his visit to the UAR. © Bettmann/CORBIS. Used with permission. Do not reproduce.

The post Imagination and reason appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGoogle Books is fair useThe new lipid guidelines and an age-old principleBest international law books of 2013

Related StoriesGoogle Books is fair useThe new lipid guidelines and an age-old principleBest international law books of 2013

Earth’s forgotten places

Since we have spent the last several months examining the places which have made the biggest impact in recent years, we decided to take a look at some of the locations on Earth which humans have left behind.

Moonville Tunnel

Moonville, Ohio

Train traffic around Moonville dramatically increased after the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad bought out the Marietta and Cincinnati Railroad in 1887. By the 1900s, coal mines began closing down, and the population of the town began to scatter. The last family to leave the town did so in 1947. Most of the buildings had disappeared by the 1960s, and there is now very little to tell the site by— only the town cemetery, and the Moonville tunnel, which is a subject of many ghost stories.

Sesena, Spain

Once projected to become the Manhattan of Madrid, the town now sits quietly, thanks to Spain’s housing market crash and economic implosion. 30,000 people were due to reside in Sesena; of the 13,000 homes originally planned to be constructed, only 5,100 were built. Most of them are now inhabited by Spaniards who bought them as investments, but are now competing to offload them at huge losses.

North Dakota’s Emptied Prairie

In the early 20th century, farmers swarmed in and settled down in the seemingly promising North Dakota prairie. Towns and homesteads were built based on these hopes. The settlers believed that rain followed the plow, but they were proved wrong by Mother Nature; following years of unsuccessful attempts to cultivate the land, many of the farmers have since left for greener pastures, leaving ghost towns in their wake.

The Village of Pegrema, Republic of Karelia, Russia

This town was abandoned after the Russian Revolution, leaving behind wooden peasant houses facing the lake.

Pegrema, Russia

Oradour-sur-Glane, France

The town was destroyed in 1944, when a total of 642 of the town’s residence were killed by the Waffen-SS on June 10, 1944. The only known survivor is Marguerite Rouffanche, aged 44.

Dallol, Ethiopia

Dallol holds the record for the highest temperature for an inhabited location on Earth, the average annual temperature being 35 degrees Celsius, 96 degrees Fahrenheit (recorded 1960-1966). There is no form of regular transportation in the area except for camel caravans that travel around the area to collect salt.

North Brother Island, New York City

This 20-acre island in the East River was used until the mid-20th century as an isolated hospital for infectious patients; Typhoid Mary lived out her final years here. The island was abandoned in 1963, and has become a wildlife sanctuary. Plants, animals and trees now grow all across and inside the ruined hospital campus.

Ruins of Riverside Hospital, North Brother Island, New York

Eun Yeom is a publicity intern at Oxford University Press USA.

Oxford’s Atlas of the World — the only world atlas updated annually, guaranteeing that users will find the most current geographic information — is the most authoritative resource on the market. The milestone Twentieth Edition is full of crisp, clear cartography of urban areas and virtually uninhabited landscapes around the globe, maps of cities and regions at carefully selected scales that give a striking view of the Earth’s surface, and the most up-to-date census information. The acclaimed resource is not only the best-selling volume of its size and price, but also the benchmark by which all other atlases are measured.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only geography articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits:

Moonville Tunnel by ChristopherM, Creative Commons via Wikipedia

Karelia old houses by Jurij Burkanov, Creative Commons via Wikimedia Commons

Riverside Hospital by reivax, Creative Commons via Wikimedia Commons

The post Earth’s forgotten places appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMaps of the worldAround the world in eighty mouse clicksA Nelson Mandela reading list

Related StoriesMaps of the worldAround the world in eighty mouse clicksA Nelson Mandela reading list

Best international law books of 2013

We invited our authors and editors to share their picks for the best books in international law in 2013. Here are their choices.

“The best book in international law published in 2013 I have read is Sarah Dromgoole’s Underwater Cultural Heritage and International Law (Cambridge UP). It is a beautifully written account of a terribly complex area of international law (which brings together law of the sea, cultural heritage law and general international law). It explains things thoroughly and understandably, but without oversimplifying complicated debates.”

— Lucas Lixinski, author of Intangible Cultural Heritage in International Law

“The Prohibition of Torture in Exceptional Circumstances by Michelle Farrell (Cambridge UP) critiques the ticking bomb scenario by reading it as a fiction and one that seeks to render the realities of the everyday practice of torture both morally and legally invisible. Whilst Farrell engages with the ontics of the prohibition of torture within international law, her main thesis endeavours to get to the heart of the so-called torture debate by showing how the ticking bomb construct is able to, in the public domain, transform the figure of the alleged ‘terrorist’ into a bare life figure (recalling Agamben) that is excluded from the legal sphere through a Schmittian state of exception. Farrell’s thesis takes us away from a rather comfortable, but insufficient, rationalization provided both by the ticking bomb construct as well as the more conventional approaches of academics and lawyers to the torture debate, by providing a necessary critique of the relationship between law and violence.”

— Kathleen Cavanaugh, co-author of Minority Rights in the Middle East

“The accepted history of international criminal law is a story of irreversible progress leading to the unfurling of an international rule of law and an end to impunity. The Hidden Histories of War Crimes Trials (Oxford UP, 2013), a collection of essays edited by Kevin Jon Heller and Gerry Simpson, is a timely corrective to the elisions of such panegyrics. Colonial trials in Africa and Siam, Australian-orchestrated proceedings in the Asia-Pacific, atrocities in the Southern Cone of Latin America: these too, the volume’s contributors argue, are part of the field’s history. But it is not only the ‘under-told trial histories’ that are brought in from the margins. We learn too, for example in Grietje Baars’ contribution, of the systematic writing-out of official histories of the relationship between political economy and war. The field draws attention to ‘individual deviancy’ while eliding, and even obfuscating, the economic bases of atrocity: international criminal law as ‘capitalism’s victor’s justice’. For those tired of stale narrative arcs—‘from Nuremberg to The Hague’—or curious about the field’s ‘hidden histories’, the volume is highly recommended.”

“The accepted history of international criminal law is a story of irreversible progress leading to the unfurling of an international rule of law and an end to impunity. The Hidden Histories of War Crimes Trials (Oxford UP, 2013), a collection of essays edited by Kevin Jon Heller and Gerry Simpson, is a timely corrective to the elisions of such panegyrics. Colonial trials in Africa and Siam, Australian-orchestrated proceedings in the Asia-Pacific, atrocities in the Southern Cone of Latin America: these too, the volume’s contributors argue, are part of the field’s history. But it is not only the ‘under-told trial histories’ that are brought in from the margins. We learn too, for example in Grietje Baars’ contribution, of the systematic writing-out of official histories of the relationship between political economy and war. The field draws attention to ‘individual deviancy’ while eliding, and even obfuscating, the economic bases of atrocity: international criminal law as ‘capitalism’s victor’s justice’. For those tired of stale narrative arcs—‘from Nuremberg to The Hague’—or curious about the field’s ‘hidden histories’, the volume is highly recommended.”

— Tor Krever, Assistant Editor of the London Review of International Law

“Daniel Bodansky’s Art and Craft of International Environmental Law (Harvard UP, 2011), is an instant classic. I am using the book in preparation to teach a course on international law of the sea, with a focus on marine environmental protection. The study captures a lifetime of experience and wisdom to take the reader through the emergence of international law and policy, the stakeholders and institutions involved in its development, and how impediments to cooperation can be overcome. The great thing about the book is that it is a deep and sophisticated treatment of the theory and application of international environmental law, but the text unfolds at an engaging clip—a combination of historical thriller, game theory, and practical manual for continuing to build-out international environmental regimes. Throughout this book, Bodansky is masterful in carefully dissecting facts and values, and in distinguishing between the doctrine of law and the normative goals of policy. If I owned just one book on international environmental law, this would be it.”

— James Kraska is the author of Maritime Power and the Law of the Sea: Expeditionary Operations in World Politics

“My recommendation for a 2013 book would be the Tallinn Manual on the International Law Applicable to Cyber Warfare (Cambridge UP, 2013) edited by Michael N. Schmitt. An independent “International Group of Experts” (IGE) spent three years (with financial assistance from NATO) attempting to describe the existing international law for cyber-space. The resulting Tallinn Manual contains 95 separate rules on questions of state responsibility, the jus ad bellum, and the jus in bello along with detailed commentary for each rule. Simply put, the Tallinn Manual is a must-read for anyone interested in cyber warfare and I assume it’s already widely read within foreign and defense ministries across the Globe. You can disagree with its conclusions in some places — and I do in some key respects such as the Manual’s definitions of what cyber operations constitute a use of force and the need for an ‘attack’ to produce physical damage under the jus in bello. Nonetheless, I recommend reading the Tallinn Manual because it’s a necessary and important first step in delineating how international law operates in cyberspace. Indeed, some of the most important parts of the Manual are not the rules themselves so much as the Commentary’s discussion of paths not taken and areas of continuing disagreement among the IGE. All told, the Manual provides a map for future discourse that will surely be an increasingly important part of the international law conversation.”

— Duncan B. Hollis is the editor of The Oxford Guide to Treaties

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in international law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide. For the latest news, commentary, and insights follow the International Law team on Twitter @OUPIntLaw.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Best international law books of 2013 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGoogle Books is fair useInternational Law at Oxford in 2013Human Rights protection at the European Court

Related StoriesGoogle Books is fair useInternational Law at Oxford in 2013Human Rights protection at the European Court

Google Books is fair use

After almost a decade of litigation, on 14 November the Southern District Court of New York has ruled on the class action Authors Guild v Google. Judge Chin, who had rejected in March 2011 the agreement proposing to settle the case, found that the activities carried out in the context of the Google Books project do not infringe copyright. In a nutshell, the ruling affirms that reproducing in-copyright works to make them searchable on the Internet is a fair use under US law.

The legal outcome does not come as a surprise in light of the recent judicial trend in the United States to find fairness in uses that are critical to the functioning of new technologies that would enhance public welfare. Moreover, the project under examination in this case has received wide public support and recognition, and a decision that had outlawed it would have faced serious opposition. Nonetheless, this decision is one of those that mark a watershed in copyright law.

Copyright has been viewed for long time as a right to prevent copying of works. Although this right has always been subject to limitations—including the American doctrine of fair use—no limitation has so far covered an activity that involves systematic and wholesale verbatim reproduction of millions of works. Besides this striking quantitative dimension of copying in Google Books, there are qualitative factors to be taken into account when deciding whether a use is fair or not. The fair use defence has so far covered mainly uses that are either private or transformative in nature. Recently, however, American jurisprudence has expanded the notion of “transformativeness” as embodied in the fair use test to include modification induced by technology in the name of the public interest—for instance, the reduction in size of images to function as thumbnails in search results with a view to enable faster and easier online searches. The Google Books decision has pushed this notion to its boundaries: what is “transformed” is no longer the work as such nor its function, but the use thereof that technology enables. To Justice Chin: “Words in books are being used in a way that they have not been used before. Google Books has created something new in the use of book text”—namely words are now “pointers directing users to a broad selection of books,” or alternatively “data for purposes of substantive research, including data mining and text mining.” There is public interest in having millions of books searchable in this novel way and, since none of these technology-enabled uses supersede or supplant books, they cannot encroach upon the legitimate interests of the rightholders.

What happens now? This ruling is certainly not the final round of the long litigation, and the Authors Guild has already announced that it will appeal. In our view, it is likely that upper courts will expand on the (peculiarly succinct) argument of J. Chin, but will not overturn it. For the time being, the Google Books case instructs that copying for enabling internet search and content mining is a permitted activity under US law. This, in our opinion, will boost the Congress to legislate on orphan works, so to enable Google to display more than just “snippets” of that large amount of works that are still in copyright but cannot clear a license for.

And in Europe? The decision has formally no ground of application outside the United States, although Internet activities are notoriously borderless. As recently reaffirmed by the Advocate General of the CJEU in the Google Spain case (C-131/12), national law applies where a search engine establishes in a Member State an office which orientates its activity towards the inhabitants of that State. This means that authors and publishers of EU Member States can still challenge Google Books under national laws. However, it is unlikely this will happen. A lawsuit with French publishers has been settled in 2012, and no other cases are currently pending on this side of the Atlantic. The Google Books decision, however, may have an indirect impact on European legislations. Since copying for automated text processing (indexing, search, and data mining) is not clearly covered by any of the available exceptions and limitations in Europe, legislators may have to “update” copyright law accordingly. A wise blend of copyright exceptions, fair compensation schemes, and compulsory licenses may serve this purpose perhaps more efficiently than the flexible but unpredictable fair use doctrine. With its announced copyright reform, the United Kingdom is the first European country to move in this direction.

Maurizio Borghi is senior lecturer at Brunel University Law School and director of the Centre for Intellectual Property, Internet and Media. He is a founding member of ISHTIP, the International Society for the History and Theory of Intellectual Property. Stavroula Karapapa is senior lecturer in law at the School of Law, University of Reading and an advocate at the Athens Bar, specialising in Intellectual Property and Internet law. Her research interests focus on the intersection of law and technology with particular emphasis on copyright. They are the authors of Copyright and Mass Digitization.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Copyright by Pasha Ignatov, via iStockphoto.

The post Google Books is fair use appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFrom radio to YouTubeReading the tea leaves: a Q&A with Costas PanagopoulosBrave new world of foundations

Related StoriesFrom radio to YouTubeReading the tea leaves: a Q&A with Costas PanagopoulosBrave new world of foundations

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers