Oxford University Press's Blog, page 863

December 19, 2013

Brave new world of foundations

Private foundations are attracting a lot of attention as far as international asset protection and estate planning are concerned.

The international terminology which is used to define a private foundation, however, is complex and even more confusing. But the foundations, fondations, fundaciones, fondazioni, Stiftungen, or stichtings, or whatever private foundations may be called internationally, have one thing in common, which is their basic structure. They all can be defined as a separate fund which is donated by a founder to serve a particular purpose, either public or private in nature. But this is also exactly where the common features end. Legal regimes vary and an entity that is regarded as a private foundation in one country may not qualify as a private foundation in another. Some entities which are called foundations do not even come close to the concept of a private foundation.

The foundation stone to the introduction of private foundations was laid as early as 1926 by the Principality of Liechtenstein, the first jurisdiction to introduce entirely private foundations in the sense of family foundations which stand in contrast to public and charitable foundations. The success of this European prototype has first encouraged other civil law countries overseas to introduce their private foundations, among them Panama in 1995, whose regulation of the foundation was inspired by the Liechtenstein foundation law. Despite the fact that a foundation is difficult to classify under Anglo-Saxon law, common law jurisdictions soon followed suit and began to introduce their own foundation concepts, with St. Kitts in 2003 and The Bahamas in 2004, being the first. As of today the foundation landscape encompasses 22 main jurisdictions, among them civil as well as common law jurisdictions, including Jersey, Guernsey, and the Isle of Man. The adoption by predominantly trust-oriented common law jurisdictions of a civil law concept presents several challenges, such as the ones discussed in the following paragraphs, and it is noticeable that the features of the different laws vary considerably, although one factor common to both the civil law and common law jurisdictions is that the private foundation enjoys separate legal personality.

A question that is closely related to this legal personality and thus the international recognition of private foundations is the question which precedents will be applied to foundation cases. Established foundation jurisdictions like Liechtenstein and Panama dispose of jurisprudence with a view to private foundations but this is not yet the case in common law jurisdictions where the versatility of private foundations first needs to be tested by the courts. The basic problem with the introduction of foundations in common law jurisdictions after all lies in the fact that they are introducing a concept that originally stems from civil, indeed Roman law. This reception of the private foundation in common law jurisdictions has thus undeniably led to a mix between bestowing legal personality on common law private foundations together with certain corporate aspects as well as with features of Anglo-Saxon trust law thereby varying the original legal concept. Concepts thus either reflect common law approaches that bring aspects of the common law trust into the definition of a private foundation or civil law approaches that distinguish between legal persons that have members and others that have not. As a consequence of this it is thus unclear whether the courts in common law jurisdictions will apply trust precedents to private foundations or whether they will treat them as a concept similar but clearly distinctive from trusts. This question is rendered even more complicated as new versions of private foundations, like private purpose foundations, that more resemble a company than a classic private foundation, have begun to appear on the scene. In addition, many of the newer foundation jurisdictions have endeavoured to create a legal entity that is neither a trust in corporate form, nor a company endowed with fiduciary characteristics.

As a consequence of its enveloping international use, the international private foundation of today clearly fulfils the same role that has been occupied for many years by the well-established and long-favoured common law trust. It goes without saying that both trusts and private foundations are legitimate vehicles for asset protection and estate planning and that both, if set up correctly, generally provide sufficient separation of ownership. There is certainly no easy solution as to the choice between a trust or a private foundation. Each case depends upon its own facts. This said, the private foundation should nevertheless be looked at by the common law advisor as a serious alternative to a trust.

Dr Johanna Niegel joined Allgemeines Treuunternehmen (ATU), Vaduz, Liechtenstein, in 1999 and has ever since specialized in the comparative analysis of international private foundations and trusts. She has been editing the foundation issue of the Trusts & Trustees journal called Private Foundations: A World Review since its inception in 2004 and is now also an editor to the survey book entitled Private Foundations World Survey, that was published by Oxford University Press in August 2013. She currently serves as Deputy Chairman of the Vaduz Centre of STEP Switzerland & Liechtenstein.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Flag of Leichenstein. By creisinger, via iStockphoto.

The post Brave new world of foundations appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe G20: policies, politics, and powerWrap contracts: the online scourgePerformance pay and ethnic earnings

Related StoriesThe G20: policies, politics, and powerWrap contracts: the online scourgePerformance pay and ethnic earnings

December 18, 2013

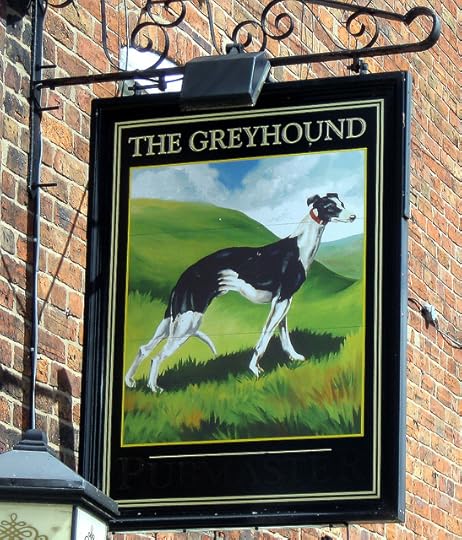

Gray matter, part 2, or, going to the dogs again

I am returning to greyhound, a word whose origin has been discussed with rare dedication and relatively meager results. The component -hound is the generic word for “dog” everywhere in Germanic, except English. I am aware of only one attempt to identify -hound with hunter (so in in the 1688 dictionary by Rúnolfur Jónsson). Today no one doubts that greyhound goes back to the rather obscure Old Engl. grighund and that it is a cognate or a borrowing of Old Icelandic greyhundr. In Icelandic, grey means “bitch” and could always be used in the same derogatory sense as Modern Engl. bitch. For example, in a blasphemous ditty attributed to a tenth-century man, the goddess Freyja was called a grey. Discussion of whether a fertility goddess’s promiscuity deserved this censure and whether the poet’s “lesser outlawry” was a condign punishment for the ditty can be left for another occasion.

Even if we agree that in greyhound both elements mean nearly the same, the word’s overall structure is not absolutely clear. It looks like a tautological compound in which the parts are near synonyms. But, not improbably, the first element in it defines the second: grey would be specific and hound generic (“a dog which is a bitch”). This, however, is a minor point. The real question concerns the origin of grey-. In 1686, it was written that grey goes back to Latin gradus, as in Engl. degree, “because among All Dogs these are the most principal, having the chiefest place and being simply and absolutely the best of the gentle kind of Hounds.” This statement is an English translation of what was said as early as 1570.

The Latin for greyhound was Leporarius, from lepus “hare.” An extremely active contributor to Notes and Queries, who hid under the initials W.H., derived grey- from Irish garrey “hare” (greyhound = “hare-hound”). This is not a bad guess, as we know from both the meaning of Leporarius and many people’s habit of hunting with the hounds and running with the hare. But Mr. W.H. was immediately put right: the correct Irish form, he was told, is not garrey but gerrfhtiadh and it is not a particularly old word, while greyhound has an Old English ancestor. Another proposed Celtic antecedent of grey- was Gaelic greigh “flock, herd,” because dogs hunt in packs. As Skeat (already in 1868, years before he became an iconic figure in English etymology) pointed out, a compound made up of a Celtic element appended to an English one could hardly be imagined, considering that grighound occurred in Old English.

Where did the greyhound come from?

In the Latin nomenclature of Anglo-Saxon England, the greyhound, thanks to its swiftness, was known as Cursorius canis “running dog.” So perhaps in Old Engl. grighund, the first element is the same as Engl. grig “eel”? This would yield greyhound “sprightly, brisk dog.” Like most monosyllabic words beginning and ending with the same consonant, grig is a formation of uncertain etymology, but it seems to have been first applied to any diminutive, rather than quick, creature. (Irish greigh also means “a sudden burst of light,” which allegedly confirms the idea of swiftness.) Fortunately for this narrative, grig in the phrase merry as a grig is an alternation of Greek, a circumstance that allows us to turn our attention to Greece.

The hypothesis of the Greek origin of grey in greyhound probably belongs to Minsheu; it appears in his 1617 etymological dictionary. But why Greek? Because Greek “has always been associated with jollity, luxury, &c.” (so another contributor to Notes and Queries). And hunting, it was implied, is a sport of and for the jolly. Minsheu asserted that greyhounds were first used in Greece but did not offer any evidence in support of his statement. A learned contributor to the discussion wrote that “according to the older and the younger Xenophon it seems this species of dog did not exist in Greece.” Not being a specialist, I can only say that the chapter on dogs in Xenophon is long.

We find still another putative cognate of grey-, namely Engl. gres “buck” (the name alludes to grass and grazing: gres “a fatted buck”). Greyhounds “were used for pulling down the stag, and hunting the wolf and the wild boar; and were a rough dog, like the present Scotch deer-hound.” Buck emerged as a substitute for any big beast, and greyhound as “a dog trained for the chase of the noblest and strongest game.” However, not everybody emphasized the greyhound’s ferocity. Most people admired “this beautifully majestic, gentle, graceful, surpassingly swift, and courageous animal.” All this is very interesting but not instructive, because the old age of the compound and the evidence of the Scandinavian cognate cannot be shaken off. Quite naturally, Murray considered surveying, let alone refuting, such amateurish inroads on etymology below his dignity, but they are good enough for our entertainment, especially during the holiday season.

So what is the origin of Icelandic grey ~ Old Engl. grig- “female dog”? As mentioned in the previous post, Jan de Vries did not exclude a connection between grey and the color name. Before him, another distinguished etymologist Ferdinand Holthausen was of the same opinion (also with a question mark). The OED online treats this idea with justified suspicion. But everything depends on the “shades of gray.” If the Old English adjective could (as Wedgwood suggested) mean “speckled,” the reference might be to the patches often seen on a greyhound. Besides, color words are moving targets. For instance, a possible cognate of gray is Latin ravus “tawny.” Other than that, the names of female animals are usually opaque, as the following list will show (the words left without a gloss mean “bitch”).

Engl. bitch (from bikke)

Old Icelandic bikkja and baka (greybaka does no meant “grayback”!)

German Petze (from some form like betta?)

German Bache “sow; female pig” (from bakka?)

Middle Dutch big, bik, bag

the like “piglet,” Dutch big “pig,” and Engl. pig

Engl. tyke

Old Icelandic tík

Old Engl. ticken “kid” (with a close cognate in German Ziege “nanny-goat”)

German Zohe (from zoha; Icelandic tóa “female fox”)

Greek díza

the somewhat similar German word Töle (a diminutive?)

Dutch teef

German Zibbe (an obvious cognate)

Old Engl. tife

Among the glosses of the words given above, “female dog” predominates, but it competes with “ewe,” “sow,” and “nanny-goat.” The impression is that such sound complexes (tik, tib, big, pig, bak), which resemble baby words, designated pets or cuddly female domestic animals and were not necessarily tied to female dogs. Some coincidences are downright astounding. Russian sobaka “bitch” (stress on the second syllable) is a loanword from the East, but its last two syllables coincide with Icelandic baka (most probably, by chance). Could grig- be one of such migratory words for a female dog (ewe, sow), puppy, piglet, kid, lamb, and the like? Among the non-Germanic words for the greyhound, I find Polish ogar, Hungarian agár, and a few others (with old and modern cognates elsewhere in Slavic, Turkic, and the Caucasian languages); Old Russian grich’ meant “hunting dog.” Perhaps we will know more about the origin of grey- in greyhound when we get a full picture of how this breed spread through the countries of Eurasia. At the moment, we should only admit that to an etymologist the greyhounds are a rough dog.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: The Greyhound Inn sign, Whitchurch. Photo by harrypope. Creative Commons License via harrypope Flickr.

The post Gray matter, part 2, or, going to the dogs again appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGray matter, or many more shades of grey/gray, part 1From the infancy of etymologyEtymology gleanings for November 2013

Related StoriesGray matter, or many more shades of grey/gray, part 1From the infancy of etymologyEtymology gleanings for November 2013

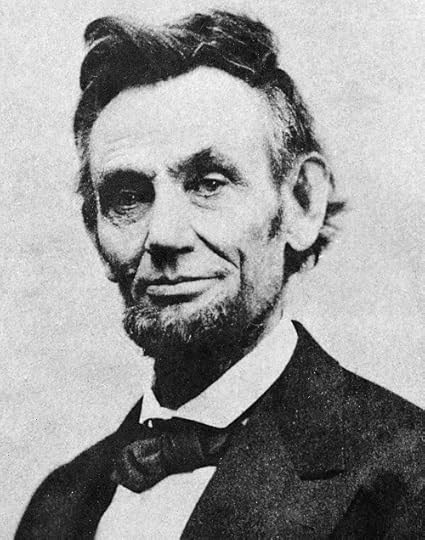

The Thirteenth Amendment

On 18 December 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution was ratified, thus ending the epochal struggle to kill American slavery. But the long struggle to achieve full equality regardless of race was just beginning.

When Abraham Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation, he knew very well that it might eventually be overturned in court as unconstitutional. That was why in December 1862 he urged Congress to pass a package of constitutional amendments that would engraft his administration’s policies on slavery into the Constitution itself.

On 14 December 1863, Representative James Ashley introduced a resolution for a single constitutional amendment that would end slavery. Several other members of Congress introduced resolutions that differed in language from the text that Ashley had proposed. The Senate Judiciary Committee synthesized the various proposals and the Senate passed the constitutional amendment on 8 April 1864. But the measure was bogged down in the House of Representatives.

The presidential election of 1864 was extremely dangerous for Lincoln and the Republicans. War-weariness and a white supremacist backlash against emancipation made Republicans, including Lincoln, run scared. One of the symptoms of Republican fear was the decision to dump Lincoln’s vice president, Hannibal Hamlin of Maine, and replace him with a southern unionist Democrat, Andrew Johnson of Tennessee. While publicly de-emphasizing the stalled Thirteenth Amendment, Lincoln quietly worked behind the scenes to have the Republican platform endorse it.

Photo of Lincoln shortly before he died, 10 April 1865. Edited by Soerfm. CC 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

After the tide of war turned to the extent that Lincoln was re-elected in a landslide, the president lobbied the outgoing Congress to pass the Thirteenth Amendment. The extent of this campaign must to some extent remain mysterious, since Lincoln left few records of his back-room maneuvering. But its nature can grasped by its depiction in the recent Stephen Spielberg film, Lincoln.

When the House of Representatives passed the amendment (by the necessary two-thirds super-majority), Lincoln was jubilant. He called the amendment “the King’s cure for all the evils” and said that the occasion was “one of congratulation to the country and to the whole world.”

On 5 February 1865, Lincoln secretly proposed to his cabinet an audacious (and absolutely unprecedented) plan to assure that the amendment would be ratified by the necessary two-thirds of the states. Lincoln actually suggested that Congress should pay all the slave states to ratify — to the tune of $400 million. But the members of Lincoln’s cabinet resisted the proposal, so the president shelved it.

By the time that Lincoln was assassinated, most of the northern states were in the process of ratifying the amendment. While the new president, Andrew Johnson, was committed to its ratification — he saw the destruction of slavery as a blow to the leadership elite that had master-minded secession — he was no friend to the freedmen. Johnson told the governors of several southern states that the blacks could still be “kept in their place” through state legislation that would reduce them to second-class citizens. When South Carolina ratified the amendment, the ratification was conditional: a declaration was attached to the effect that Congress would have no right to legislate on the political status of the former slaves. Alabama did the same thing.

It was the duty of William Seward, the Secretary of State, to coordinate the ratification process and pronounce it complete when the requisite three quarters of the states (in this case 36 states) had ratified. After Georgia had ratified (on 6 December), Seward proclaimed on 18 December 1865 that the constitution had been duly amended.

But the joyousness of this occasion, at least among those who detested slavery, would prove to be less than it might have been if only Lincoln were alive. In the final speech of his life, Lincoln endorsed the idea of black voting rights. There can be little doubt that the re-elected president would have worked with the Republican super-majorities that would dominate the next Congress to create a Reconstruction that would give the newly-freed slaves a decent chance at full citizenship. But John Wilkes Booth had destroyed that incipient future. Instead, the new Republican Congress would be forced to work with an obstructive white supremacist Democrat in the White House, Andrew Johnson. And, as events turned out, the civil rights revolution would have to wait another hundred years.

Richard Striner, a history professor at Washington College in Chestertown, Maryland, is the author of several books including Father Abraham: Lincoln’s Relentless Struggle to End Slavery, Lincoln’s Way: How Six Great Presidents Created American Power, and Lincoln and Race. His latest presidential study — Woodrow Wilson and World War I: A Burden Too Great To Bear — will be published in spring 2014.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The Thirteenth Amendment appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTen things to understand about the Molly MaguiresThe G20: policies, politics, and powerNon-belief as a moral obligation

Related StoriesTen things to understand about the Molly MaguiresThe G20: policies, politics, and powerNon-belief as a moral obligation

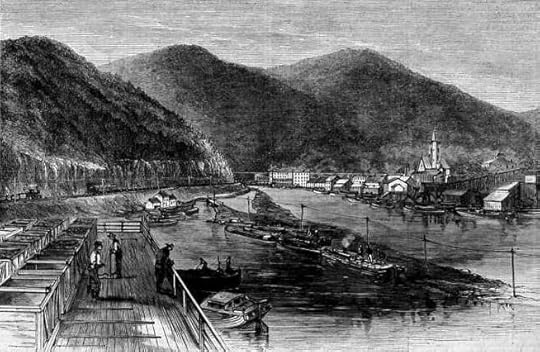

Ten things to understand about the Molly Maguires

On this day 135 years ago, John Kehoe was hanged. Convicted in 1877 of murdering a Pennsylvania mine boss 15 years earlier, he was almost certainly innocent of that crime. But Kehoe also stood accused of being the mastermind in a nefarious secret society called the Molly Maguires. The existence of that organization has long been disputed, but some Irish workers in Pennsylvania clearly used violence to advance the cause of labor as they saw it.

(1) Twenty young Irishmen were hanged in the anthracite region of northeast Pennsylvania in the late 1870s, convicted of a series of killings stretching back to the Civil War. The men were said to belong to a secret society called the Molly Maguires. They were convicted of killing as many as sixteen mine owners, superintendents, bosses, and workers.

(2) To gather information against the Molly Maguires, Franklin B. Gowen of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad hired Allan Pinkerton, America’s first private detective. Pinkerton dispatched an Irish-born agent named James McParlan the anthracite region to infiltrate the organization in October 1873. McParlan spend the next eighteen months working undercover and it was largely on his evidence that the Molly Maguires were convicted.

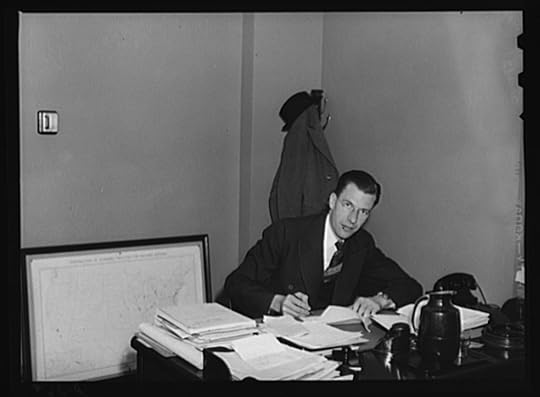

James McParlan, 188-. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

(3) According to McParlan, the Molly Maguires acted behind the cover of an otherwise peaceful Irish fraternal organization called the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH), which had branches throughout the United States, Britain, and Ireland. The leader of the local AOH was John Kehoe.

(4) The Molly Maguires took their name from a rural secret society in Ireland. The Irish Mollys were so-named because their members (invariably young men) disguised themselves in women’s clothing, used powder or burnt cork on their faces, and pledged their allegiance to a mythical woman — Mistress Molly Maguire — who symbolized their struggle against injustice.

(5) The American Mollys Maguires were a rare transatlantic outgrowth of this pattern of Irish rural protest. They did not disguise themselves in women’s clothing, though some of them “blacked up” for disguise. Like their Irish counterparts, they were led by tavern keepers and called on strangers from neighboring “lodges” of the AOH to carry out beatings and killings, pledging to return the favor at a later date.

(6) There were two distinct waves of Molly Maguire activity in Pennsylvania. The first wave, which included six assassinations, involved a combination of resistance to the military draft and rudimentary labor organizing. It was only during the trials of the 1870s that these killings retrospectively traced to individual members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians. The first killing, that of the mine foreman Frank W. Langdon in 1862, was pinned on John Kehoe in this way.

(7) The second wave of violence occurred in 1875, after the collapse the Workingmen’s Benevolent Association (WBA), a labor union that united Irish, British, and American workers across the lines of ethnicity and skill. When the miners’ union went down to defeat in 1875, the Molly Maguires stepped into the vacuum. Six of the 16 assassinations attributed to them took place that summer. With union defeated, Franklin B. Gowen then crushed the Molly Maguires.

(8) The Molly Maguires were arrested by the private police force of Franklin B. Gowen’s Philadelphia & Reading Railroad. They were convicted on the evidence of an undercover detective whom the defense accused of being an agent provocateur, supplemented by the confessions of informers who turned state’s evidence to save their necks. No Irish Catholics served on the juries. Most of the prosecuting attorneys worked for railroads and mining companies. Franklin B. Gowen appeared as the star prosecutor at several trials, and he published his courtroom speeches as popular pamphlets.

(9) The first 10 “Molly Maguires” were hanged on a single day, 21 June 1877, known to the people of the anthracite region ever since as “Black Thursday” or “the day of the rope.” Six men were hanged in Pottsville and four in nearby Mauch Chunk (today’s Jim Thorpe). Ten more went to the gallows over the next three years.

View of Mauch Chunk, Carbon County, Pennsylvania, a wood engraving sketched by Theodore R. Davis and published in Harper’s Weekly, September 1869. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

(10) The Molly Maguires have been the subject of several novels, stage plays, and a movie. Allan Pinkerton published the first book on the subject, The Molly Maguires and the Detectives, in 1877. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who met Pinkerton’s son on an Atlantic crossing, based the plot of his Sherlock Holmes novel The Valley of Fear (1904) on the Molly Maguires, in which the fictional Detective John McMurdo does battle against the “Scowrers,” a murderous secret society operating within the Eminent Order of Freemen and presided over by “Black Jack” McGinty. Both of these works glorified the detective-informer and vilified the Molly Maguires but the movie The Molly Maguires (1968) turned the tables, with John Kehoe (Sean Connery) as the hero and McParlan (Richard Harris) as the anti-hero. The director, Walter Bernstein, who had been blacklisted in the McCarthy era, saw his film as a partial response to Elia Kazan, a “friendly witness” in the HUAC investigations, whose hero in On the Waterfront informs against his corrupt union bosses.

Kevin Kenny is Professor of History at Boston College. His principal area of research and teaching is the history of migration and popular protest in the Atlantic world. His books include Making Sense of the Molly Maguires, Diaspora: A Very Short Introduction, Peaceable Kingdom Lost: The Paxton Boys and the Destruction of William Penn’s Holy Experiment, and The American Irish: A History. He is currently researching various aspects of migration and popular protest in the Atlantic world and laying the groundwork for a long-term project investigating the meaning of immigration in American history.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Ten things to understand about the Molly Maguires appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe G20: policies, politics, and powerWrap contracts: the online scourgeNon-belief as a moral obligation

Related StoriesThe G20: policies, politics, and powerWrap contracts: the online scourgeNon-belief as a moral obligation

Performance pay and ethnic earnings

The British labour market shares two important trends with that in the United States. Wage inequality has increased dramatically since the 1980s and there has been increased use of performance pay, earnings that vary with worker job performance. These twin trends have generated concern in the United States that performance pay causes certain groups in society to ‘lose out’ in the labour market. Indeed, research suggests that the earnings gap between white and black Americans is far larger among those receiving performance pay than among those receiving time rates.

Performance pay provides employers the opportunity to pay workers doing similar tasks differing amounts and as a result it may influence white versus non-white earnings and the extent of wage discrimination. On one hand, tying wages directly to worker’s output should reduce the prospect of discrimination. Simply put, paying two workers of different ethnicity who produce the same amount differing wages makes discrimination quite obvious. The first guess then might be that increased performance pay should reduce discriminatory behaviour and close the earnings gap. On the other hand, much of performance pay comes as bonuses based on subjective judgements or easily manipulated standards. Critically, performance pay may differ across the earnings distribution as at the bottom performance may be easily quantified and rewarded using, for example, piece rates. At the top, the duties of a professional or manager may have many dimensions that are not as easily quantified and tied to rewards. Thus, it is important to examine the role that performance pay has at different places in the distribution of earnings.

The new research for Britain uses data from 1998 to 2008 to show that non-white men who receive performance pay are actually paid more similarly to white male workers. This is most pronounced for those who receive bonus payments. Moreover, at higher wages, non-white men who receive bonuses earn roughly the same amount as their white counterparts. The influence of performance pay in closing the earnings gap appears in the upper middle portion of the distribution. Thus, at the 75th percent of the earnings distribution white workers receiving a bonus earn 2.6% more than those not receiving a bonus. Non-white workers receiving a bonus at the same point in the distribution earn 7.6% more. This difference helps to close the ethnic earnings gap among those receiving bonuses. Other evidence from the study suggests that this partially reflects high ability non-white workers choosing to enter performance pay work. Together this new research paints a dramatically different picture from that shown in the US research. It suggests that the increasing use of performance pay in the United Kingdom has served to improve the labour market fortunes of ethnic workers in Britain.

The authors are Colin P. Green, Professor of Economics at the Lancaster University Management School, John S. Heywood, Distinguished Professor of Economics at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, and Nikolaos Theodoropoulos, Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Cyprus. They are the authors of the paper ‘Performance pay and ethnic earnings differences in Britain‘, which is published in Oxford Economic Papers. The authors worked on this research during visits to Lancaster University.

Oxford Economic Papers is a general economics journal, publishing refereed papers in economic theory, applied economics, econometrics, economic development, economic history, and the history of economic thought.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Diversity and teamwork. By anirav, via iStockphoto.

The post Performance pay and ethnic earnings appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEconomic migration may not lead to happinessWhy evolution wouldn’t favour Homo economicusThe migration-displacement nexus

Related StoriesEconomic migration may not lead to happinessWhy evolution wouldn’t favour Homo economicusThe migration-displacement nexus

The migration-displacement nexus

International Migrants Day is intended to celebrate the enormous contribution that migrants make to economic growth and development, social innovation, and cultural diversity worldwide. It also reminds us of the importance of protecting the human rights of migrants.

But recognizing these rights and realizing these opportunities has become harder in recent years because of the increasing complexity of migration, the difficulties of distinguishing different types of migrants, and the misalignment between existing categories and migration realities.

According to the UN, there are over 232 million international migrants in the world today, comprising around one in every 33 people. Not only is the scale of migration increasing, so too is its diversity. More women than ever before are migrating, and often as the breadwinners for their families. Migrants come from, go to, and transit, almost every country in the world, and over half the world’s migrants move between countries of the Global South. There are internal and international migrants; migrants who leave their homes willingly and those that are forced away by conflict; some who move permanently while others return home; those who move legally and those who do not.

There is diversity even within single categories of migration. Irregular migrants, for example, are also described as illegal, undocumented, and unauthorized. For some their lack of legal status arises because they move without authorization, while for others it is a result of staying and working without authorization. Still others are the victims of the separate crimes of migrant smuggling and human trafficking.

Distinguishing between these various migrant types has also become less straightforward. Migrating from the countryside to the city often precedes international migration. Most migrants – even refugees – exert at least some decision-making in their movement; in reality most people move for mixed motivations, including economic, political, and social factors. Legal migrants can transform into irregular migrants overnight for example by overstaying a visa. Migrant smuggling can easily transform into human trafficking.

Yet policy makers still tend to use old classification systems that do not reflect the new realities of migration. People are designated by where displacement takes place. While international migration has attracted enormous political attention in recent years, internal migration is rarely on the political agenda, despite being numerically far more significant at a global scale. Individuals are also delineated by the causes of movement. The strong international framework for refugees, for example, is not matched for economic migrants. Another distinction is on the basis of time, distinguishing for example short-term or temporary migrants from long-term or permanent migrants.

To a significant extent research on migration also reflects these classifications, with separate courses, research centers, and academic journals devoted to migration and refugees respectively. Oxford University Press for example publishes the Journal of Refugee Studies, the International Journal of Refugee Law, Refugee Survey Quarterly; but also Migration Studies.

Yet it has become increasingly clear that drawing careful lines between categories of migrants hinders rather than facilitates achieving their rights and promoting their potential. Is it reasonable to deport all irregular migrants even if some may face persecution at home? Is it possible to take advantage of the skills of refugees in the labor market, even if they have arrived for safety rather than work? Is there a case for legalizing irregular migrants if they have already lived and worked in a country for years? What happens when migrants get caught up in conflict or natural disasters and are displaced in the countries where they are working?

As the editor of the Journal of Refugee Studies I am acutely aware of the need to maintain the journal’s commitment to raising awareness, promoting debate, and publishing original research on refugees, whose number has increased by millions this year as a result of the crisis in Syria. At the same time refugees can no longer be studied exclusively, or outside a wider context. In addition to over two million Syrians forced from their country as refugees, there are as many as 6.5 million displaced internally. There are expectations that millions of people around the world may be forced from their homes in years to come by the effects of climate change, but they are not legally recognized as refugees. Increasingly refugees move alongside other migrants, for example in boats crossing the Mediterranean or heading for Australia. It is important therefore to understand that refugees co-exist and overlap with other displaced and mobile populations, and that solutions to their plight may sometimes lie in learning lessons from these other situations.

Khalid Koser is Deputy Director and Academic Dean at the Geneva Centre for Security Policy and Editor of the Journal of Refugee Studies.

Oxford University Press presents a free online collection of content from Migration Studies and the Journal of Refugee Studies in order to raise awareness of International Migrants Day on 18 December 2013.

Journal of Refugee Studies provides a forum for exploration of the complex problems of forced migration and national, regional and international responses. The Journal covers all categories of forcibly displaced people. Contributions that develop theoretical understandings of forced migration, or advance knowledge of concepts, policies and practice are welcomed from both academics and practitioners. Journal of Refugee Studies is a multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal, and is published in association with the Refugee Studies Centre, University of Oxford.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only geography articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS

Image credit: Canada Day swearing-in ceremony for new citizens. By stacey_newman via iStockphoto.

The post The migration-displacement nexus appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEconomic migration may not lead to happinessPromoting a sensible debate on migrationSeven facts of Syria’s displacement crisis

Related StoriesEconomic migration may not lead to happinessPromoting a sensible debate on migrationSeven facts of Syria’s displacement crisis

December 17, 2013

The G20: policies, politics, and power

Five years after the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, the world waits for recovery. Last time it took a world war and forty million deaths to achieve. In 2008, a domino — Lehman Brothers — fell over, sparking a financial crisis that quickly threatened to bring the developed economies of the world crashing down. “This sucker could go down” was President George W. Bush’s pithy summary. Only concerted and unprecedented action by the central banks and Treasury departments of the major countries and their smaller trading partners — now known as the G20 — narrowly averted catastrophe. But it was a close-run and we are not out of the woods yet, as the economies of Europe, Japan and North America struggle to grow, weighed down with public debt and under-capitalised banks. A pall of pessimism pervades government and financial markets.

The world appears topsy-turvy, a Shakespearian scene from Twelfth Night, in which lord becomes servant and servant lord. The western economies hang on the action or inaction of a small number of men and two women (Christine Lagarde and Angela Merkel), cloistered in the board rooms of the central banks, IMF, and national governments. The captains of industry have been demoted, great companies drip-fed by whatever credit the ‘gnomes of Zurich’, the predators of Wall street, and the policy makers in Washington in their confused wisdom decree. In this upside down world, ‘fair is foul’, as every suggestion of positive economic news about recovery in the real economy sends financial markets into panic. Addicted to the US Federal Reserves’ money printing regime, more politely termed ‘quantitative easing’ (it sounds less inflationary), the markets take fright at any suggestion that the printing presses might slow down. In Europe, ‘austerity’ has triumphed as the official mantra of the European Union. The ‘Washington Dissensus’ has taken hold as ‘Austerians’ battle with ‘Keynesians’, repacing the easy neoliberal faith in efficient markets and fable of The Great Moderation. “All that is solid melts into air”, as economists and policy makers scratch their heads in frustration. Nothing seems to be working.

None of this would have surprised 20th century American public intellectual Number One, John Kenneth Galbraith. An outsider who grew up in a small Canadian farming community, Galbraith retained this marginalised status in his chosen profession of economics. Eschewing the models, methods, and mathematics of modern economics, he devoted a long lifetime to attacking his colleagues in a prolific series of widely read books, the most famous of which was, of course, The Affluent Society, published in the first post-war period of American triumphalism. (The second period of US hubris occurred after the fall of communism in the ‘end of ideology’ era of the 1990s, to be pricked by nine-eleven, the subsequent failures in Iraq and Afghanistan and the outbreak of the global financial crisis.) Galbraith died two years before the fall of Lehman Brothers but his lifetime’s work would have prepared him for that event and for the muddled responses and blame shifting of both his colleagues and the bankers. Galbraith had written extensively on the nature of money and whence it came. He was deeply skeptical of the wisdom of the monetary authorities and the venality of actors in the financial sector. Like Keynes, he saw monetary policy as a week reed on which to base economic recovery.

Dr. John Kenneth Gailbraith, assistant administrator, Office of Price Administration (OPA) and Civilian Supply, Office of Emergency Management. Photo by Royden Dixon, 1940-1946. Office of War Information. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

On re-reading Galbraith’s book, the overwhelming truths that stand out for me in his critique of his society — and by extension, our own — amount to two. First, his famous construct — the conventional wisdom — has stood the test of time. Herd thinking and herd behaviour characterize us as a social species, in economics as everywhere. Being wrong in company is far preferable to being wrong alone, even if occasionally a stand against the wind proves to be right. It is the risk of being wrong alone that dissuades people, including economists, from seeking lonely ways of being right. Innovation is, as Galbraith observed about both politicians and businessmen, much lauded in principle but little embraced in practice; in later decades this insight was parodied in the mock warning of a fictional civil service chief to his political master: “that is very courageous, Minister”. Ideas about our world that predominate are those that are generally accepted and acceptable. This last point raises Galbraith’s other major point.

Policy is not just about disinterested scientific advice. Policy is about politics and politics is about power. Power is largely absent from orthodox economic accounts of how capitalist economies work. Even the limited use made of the concept — in models of imperfect competition — is ignored in the higher reaches of theory (exceptions, of course, exist) where the rarefied micro-foundations of mainstream macroeconomics assume perfect or near-perfect markets. Galbraith throughout his career saw power, its genesis, application, and outcome as central to understanding the development of post-war American capitalism and the latter’s export to the world. His view of the bifurcated nature of capitalism focused on the internal dynamics of corporate capitalism. His Presidential Address to the American Economic Association Conference in 1971, titled “Power in Economics,” left little impact on a profession rapidly turning to a highly formalistic and politically naïve discipline practice.

Both insights help us begin to understand the current mess that the global economy is experiencing.

Mike Berry is Emeritus Professor at RMIT University, Melbourne Australia, where he was for many years Professor of Urban Studies and Public Policy. He is the author of The Affluent Society Revisited. He is a frequent adviser to state and federal governments in Australia and has had visiting positions at a number of international institutions, including Rutgers University, Lund University, the University of Cambridge, and the University Sussex.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The G20: policies, politics, and power appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWrap contracts: the online scourgeOrwell in AmericaOur kids are safer than you might think

Related StoriesWrap contracts: the online scourgeOrwell in AmericaOur kids are safer than you might think

I’m dreaming of an OSEO Christmas

Snow is falling and your bulging stocking is being hung up above a roaring log fire. The turkey is burning in the oven as you eat your body weight in novelty chocolate. And now your weird, slightly sinister Uncle Frank is coming towards you brandishing mistletoe. This can mean only one thing. In the wise (and slightly altered) words of Noddy Holder: It’s Oxford Scholarly Editions Online Christmas!

Initially derided and dismissed as a Mummers’ play, critics have since revised their treatment of Ben Jonson’s 1616 Christmas Masque. It is now regarded as an important political and social satire on the anti-Christmas forces prevalent in Jacobean society. Jonson’s play promotes traditional Christmas festivities which was a position favoured by King James I but opposed by Puritans. King James I had delivered several public speeches in 1616 promoting traditional country life and pastimes. This Masque is seen as a rather biting criticism of the Puritans who were hostile to Christmas celebrations.

For many, Christmas is personified by mulled wine, mince pies, and The Muppet’s Christmas Carol. For Ben Jonson, it was a man dressed in strange clothes. Each to their own I suppose. The personified character of Christmas frames Ben Jonson’s masque as the first to enter the stage and the last to leave in the final scene, and is ubiquitous throughout the performance (much like the Coca-Cola Christmas advert in December). His appearance is not akin to a modern-day Santa Claus though; the character of Christmas is described by Jonson as being:

“attir’d in round Hose, long Stockings, a close Doublet, a high-crownd Hat with a Broach, a long thin beard, a Truncheon, little Ruffes, white Shoes, his Scarffes, and Garters tyed crosse, and his Drum beaten before him.”

Which, quite frankly, puts my Christmas jumpers to shame.

Robert Herrick’s writing style was strongly influenced by Ben Jonson, a man Herrick admired so much that he became a Son of Ben later in his career. Herrick also shared Jonson’s love for traditional Christmas celebration, and channelled this passion into several poems dedicated to celebrating the Christmas season. In ‘Ceremonies for Christmasse’, Herrick speaks of the ancient tradition of bringing in and setting fire to the Yule Log on Christmas Eve to illuminate the house. Herrick’s description of the “merrie merrie boyes” bringing in “The Christmas Log to the firing” is one of the earliest references to the Yule Log tradition in English literature.

It is a common misconception that the Christmas Pie that Herrick alludes to in ‘Another Ceremonie‘ is a mince-pie similar to the pies he mentions in his other Christmas poems. Instead it is a pie made up of game birds – pheasant, chicken, pigeon, hare, conies – similar in construction to a modern Yorkshire pie. At the heart of this poem is a curious ancient tradition that Herrick describes as standing guard over the Christmas Pie in order to protect the feast from depredators on Christmas Eve. This tradition has since become obsolete. Or so you may think. My Mum still stands guard over our Christmas dinner in order to stop rapscallions like my brothers (ok fine, it’s me) stealing handfuls of pigs-in-blankets.

According to the Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (OSEO) notes on John Dryden, the libretto he provided for Henry Purcell’s semi-opera King Arthur: ‘was the last Piece of Service, which I had the Honour to do, for my Gracious Master, King Charles the Second.’ There are parallels between Dryden’s libretto for King Arthur and Shakespeare’s The Tempest; Prospero and Merlin are both good magicians who use an “airy spirit” (Ariel in The Tempest, Philidel in King Arthur) to defeat a potential usurper (Alonzo/Oswald). However, one clear distinction between the two texts is that there is no evil wizard like Osmond in The Tempest.

It is Osmond who ‘strikes the ground with his Wand’ and makes the scene “change to a Prospect of Winter” in Song VII:

“Cupid sings. What ho, thou Genius of the Clime, what ho! / Ly’st thou asleep beneath those Hills of Snow? / Stretch out thy Lazy Limbs; Awake, awake, / And Winter from thy Furry Mantle shake.”

In this scene, Cupid attempts to shake Osmond’s winter from its “Hills of Snow” and bring about the start of spring. Osmond’s act of blanketing the English countryside in frozen “Beds of Everlasting Snow” in King Arthur is seen as evil; he is viewed as the Restoration equivalent of the White Witch in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (minus the Turkish Delight). However, come Christmas Day, I doubt anyone would begrudge Osmond’s intervention into nature if he conjures up a white Christmas across the United Kingdom!

Your Grandma’s chocolate Yule Log has been reduced to a modicum of crumbs on the rug and the last of the snow has fallen; our OSEO Christmas has sadly come to an end. If you’d like to uncover other festive, scholarly gifts then get your ice-skates on and see what else OSEO can offer you. Wishing you a very merry Christmas from everyone here at Oxford University Press!

Daniel Parker is a Publicity Assistant at Oxford University Press and a big fan of a festive chocolate orange.

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online provides an interlinked collection of authoritative Oxford editions of major works from the humanities. Scholarly editions are the cornerstones of humanities scholarship, and Oxford University Press’s list is unparalleled in breadth and quality. You can take a tour of the site.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Christmas Light Display. Image available on public domain via WikiCommons.

The post I’m dreaming of an OSEO Christmas appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSir John Tavener, saintly and controversial composerAn interview with Dan W. Clanton, Jr.Catching up with Sarah Brett

Related StoriesSir John Tavener, saintly and controversial composerAn interview with Dan W. Clanton, Jr.Catching up with Sarah Brett

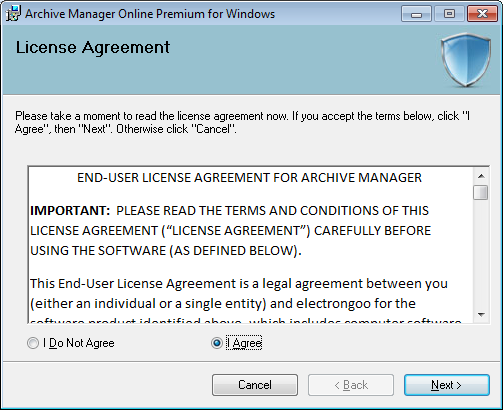

Wrap contracts: the online scourge

Can you enter into a contract without knowing it? According to many judges, the answer is yes. “Wrap contracts” are contracts that can be entered into by clicking on a link or on an “accept” icon and they govern nearly all online activity. Most of us enter into them several times a day and few of us think twice about it. Sometimes it’s because we don’t notice them. Even when we do, they don’t worry us. We think we know what they do — protect the company against litigious consumers and their greedy class action lawyers — and we think they won’t harm us. Think again.

The harms caused by wrap contracts are insidious, prompting Theresa Amato of Citizen Works to refer to them as “online asbestos.” They are everywhere, dangerous to those exposed to them, and “like asbestos, some of the dangers will not necessarily emerge for decades when content thieves and data aggregators use consumer information to the detriment of the consumers.” Wrap contracts limit a company’s liability. They can also diminish your privacy rights, take away your intellectual property and even deprive you of your free speech rights.

In the past couple of months, both Facebook and Google announced changes to their privacy policies, which would allow them to use their users’ information in paid advertisements. Facebook’s agreement, for example, states that: “You give us permission to use your name, profile picture, content, and information in connection with commercial, sponsored, or related content (such as a brand you like) served or enhanced by us. This means, for example, that you permit a business or other entity to pay us to display your name and/or profile picture with your content or information, without any compensation to you.” Sam Fiorella calls out the particularly egregious terms in Facebook Messenger’s Mobile App Terms of Service which permits the app to record audio and take pictures or videos without confirmation.

Users “agree” to these terms via wrap contracts which many fail to read.

It’s not only privacy at stake. Last summer, the Fourth Circuit held that copyright could be assigned via a click. While most sites aimed at creative users currently seek only licenses sufficient to let them provide services, those licenses may vary. Some websites seek a “perpetual, non-terminable” license which means that the license continues even after the user has quit the site (or the site has quit the user). And as we’ve seen with Facebook and Google, terms can change at any time and it’s up to the user to stay alert to those changes — or risk losing control over their creative works.

Courts construct users’ consent even when, in reality, most users are completely unaware of what the change in terms means. As long as a company makes the contract visible, courts are unconcerned with whether the user was actually aware of the contract.

While much of the attention regarding the negative uses of wrap contracts has been focused on privacy harms and control over user content, other dangers lurk for the unwary consumer (and that means all of us). Wrap contracts can be used to set “rules” or codes of conduct which companies can enforce at their discretion. In some cases, they are used to protect users and enforce civility norms. Sometimes, however, they can be used to bully users who dare to complain about bad company behavior. In August, the online consumer review company, Yelp, filed a lawsuit against a user alleging breach of contract. The contract, Yelp’s online Terms of Service, prohibits the writing of fake reviews. Yelp claimed that the user, a bankruptcy law firm, had posted fake positive reviews to make it look good and encouraged others to do the same. The case is unusual because Yelp rarely sues its users for posting fake reviews, even fake negative reviews that may harm a business. Rather than filing a lawsuit, Yelp could simply have removed the reviews and banned the law firm from its site. What takes Yelp’s lawsuit out of the realm of the unusual and into the realm of the alarming is that McMillan, the law firm that Yelp is suing, had previously sued Yelp in small claims court, claiming that it had been coerced into advertising on the site to receive favorable reviews. The small claims court agreed with McMillan and awarded a $2700 judgment against Yelp. That judgment was overturned on appeal. The reason? Under the terms of Yelp’s wrap contract, the dispute was subject to mandatory arbitration. McMillan estimated that the costs of pursuing arbitration pursuant to the clause would cost it about $4,000-$5,000.

In another disheartening example of abuse by wrap contract, a company threatened to fine a consumer named Jen Palmer $3500 for posting a negative review about it on a consumer review website. The company, KlearGear, didn’t claim that the review was false; rather, it claimed that her review ran afoul of a non-disparagement clause in the company’s online terms of sale. Palmer claims that the company reported her to a credit reporting agency which negatively affected her ability to obtain loans for a new car and home repairs. What’s particularly troubling about this example is that it’s unclear which version of the contract applied or that Palmer was even subject to KlearGear’s contract since the company did not complete the sale to her (which was the basis of her negative review). Yet, very few consumers would be willing to sue to test the validity of a wrap contract in court. The wrap contract, by its “legal” nature, can be used to intimidate consumers and deter them from acting in ways that are perfectly lawful. They allow companies to change the rules that would ordinarily apply between a company and a consumer, giving companies all the power to enforce provisions to their advantage.

The solution to wrap contracts requires raising consumer awareness of its potential dangers. Cognitive biases work against the consumer. Consumer optimism and myopia make it easy to ignore latent harms in favor of immediate gratification — why fret about hidden terms when you want to get online now? The herd effect lulls users into a false sense of security since everybody else is clicking “agree” too.

But the consumer is hardly to blame here. There is simply too much information that it would be unrealistic to expect consumers to read every wrap contract they encounter, but consumers can and should make some noise when they encounter unfair terms. They should complain to companies, the state legislature, their friends. (Faircontracts.org has other suggestions here.) What they should not be is indifferent about the status quo. Wrap contracts don’t affect just “some” consumers — they affect all of us.

The biggest danger with wrap contracts may be how they subtly push the boundaries of what is considered acceptable business conduct, cheapening the meaning of “consent” while eroding our rights one click at a time.

Nancy S. Kim is the author of Wrap Contracts: Foundations and Ramifications. She is a law professor at California Western School of Law and a visiting professor at the Rady School of Management, at the University of California, San Diego. Read her previous OUPblog article on Carnival Cruise.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Example of a wrap contract via MSWHS. Used for the purposes of illustration.

The post Wrap contracts: the online scourge appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesInternational Law at Oxford in 2013Our kids are safer than you might thinkCarnival Cruise and the contracting of everything

Related StoriesInternational Law at Oxford in 2013Our kids are safer than you might thinkCarnival Cruise and the contracting of everything

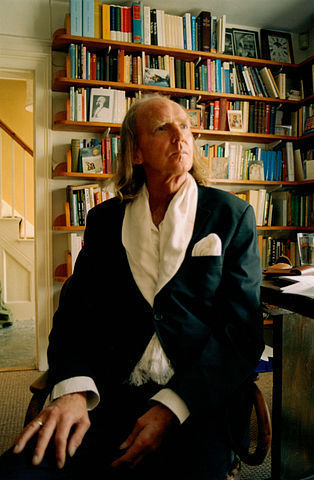

Sir John Tavener, saintly and controversial composer

The recent death of renowned British composer Sir John Tavener (1944-2013) precipitated mourning and reflection on an international scale. By the time of his death, the visionary composer had received numerous honors, including the 2003 Grammy Award for Best Classical Contemporary Composition, the 2005 Ivor Novello Classical Music Award, and a knighthood from Queen Elizabeth II. His works were almost exclusively religious in nature; nevertheless, they held appeal for sacred and secular audiences alike. This distinctive combination of spirituality and mass appeal granted Tavener a unique niche in Western classical music.

Sir John Tavener. Photo by Devlin Crow. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

Tavener’s devotion to both music and faith was evident from an early age. As a student at London’s Highgate School, which was renowned for its choral programs and frequent collaborations with the BBC in musical endeavors, he honed his already formidable skills in composition, piano and organ. He became organist and choirmaster at St. John’s Presbyterian Church in Kensington in 1961 and entered the Royal Academy of Music the following year. However, Tavener’s immersion in the doctrines and music of Western Christianity ultimately proved unfulfilling. In 1977, following his brief marriage to the young Greek ballerina Victoria Maragopoulou, he converted to the Eastern Orthodox Church. His devotion to this faith would be the guiding force of his work for the rest of his life.Tavener’s commercial success began in 1970 with the release of The Whale (1966), a dramatic cantata based on the Biblical account of Jonah and the Whale, on the Beatles’ label Apple Records. This trajectory continued in 1992, when his cello concerto The Protecting Veil (1988), inspired by the Orthodox feast of the same name and originally commissioned by the BBC for the 1989 Proms season, held the top place in the UK Classical Charts for a span of several months. The work that would complete his ascent to international acclaim was Song for Athene (1993). Ostensibly Tavener’s best-known piece, this virtuosic choral elegy drew texts from both the Orthodox funeral liturgy and Shakespeare’s Hamlet. It was originally conceived as a belated requiem for Athene Hariades, a family friend. Four years after its inception, Song for Athene was elevated to iconic status when it was performed by the Westminster Abbey Choir under the baton of Martin Neary at the 1997 funeral of Diana, Princess of Wales. As the recessional for the funeral, which was telecast from Westminster Abbey and viewed worldwide by an estimated 2.5 billion people, Song for Athene came to be recognized not only as a memorial to a specific person but also as an anthem of grief for the modern era. That this outgrowth of Tavener’s personal sorrow eventually held such grave significance for a grieving populace is a testament to the far-reaching appeal of Tavener’s music.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The compositional devices underlying a piece such as Song for Athene are manifold. Tavener counted among his artistic influences a diverse array of composers including Igor Stravinsky, Olivier Messaien, Arvo Pärt, and György Ligeti. Thus it is not surprising that his works can be found at different times to espouse and spurn the diatonic system, one moment embracing neotonal idioms and the next reveling in atonality. In the neotonal Song for Athene, Tavener employs a haunting form of melodic inversion in which two lines move in exact opposition around an inaudible line of symmetry. Orthodox influences abound in Song for Athene as well as other pieces written by Tavener during his affiliation with this denomination, manifested as settings of the Orthodox liturgy, transcriptions of Byzantine chant, and ison (drones meant to anchor the melody). Mother Thekla, founder of the first Orthodox religious order in England and Tavener’s spiritual mentor, added an additional facet of spirituality to Tavener’s music through the text that she provided for a number of his pieces.

In his final years, Tavener grew to espouse the concept of religious universalism, drawing inspiration from Eastern religions as well as Christianity. Given the tumultuous political milieu of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, this was a controversial but timely guiding principle. Tavener’s newfound approach to spirituality was embodied in The Veil of the Temple (2002), a seven-hour long setting of eight prayer cycles drawing from a vast array of belief systems including Orthodox Christianity as well as Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, and Native American religions. Tavener regarded The Veil of the Temple as “the supreme achievement of his life,” and it was a success among critics and audiences alike. More controversial was The Beautiful Names (2007), a setting in the original Arabic of the ninety-nine names of Allah as written in the Quran. Despite the fact that Charles, Prince of Wales himself had commissioned the piece, detractors claimed that in writing The Beautiful Names, Tavener had abandoned Christianity. Not to be deterred by this criticism tinged with religious prejudice, Tavener wrote, “I regard The Beautiful Names highly and think of it as one of the most important of my works.”

While Tavener was represented by turns as saintly and controversial, his ability to create works that appealed to all manifestations of human spirituality and emotion remained constant. There is no doubt that the legacy of John Tavener—an all-encompassing form of spiritual music for a changing world—will remain with us for years to come.

Emma Greenstein is currently interning for the music publications team in the Academic/Trade division. She is a trained opera singer and amateur musicologist whose interests center on music of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Sir John Tavener, saintly and controversial composer appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAn interview with marimbist Kai StensgaardTen fun facts about Claudio MonteverdiAn interview with Dan W. Clanton, Jr.

Related StoriesAn interview with marimbist Kai StensgaardTen fun facts about Claudio MonteverdiAn interview with Dan W. Clanton, Jr.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers