Oxford University Press's Blog, page 859

December 31, 2013

Dialect and identity: Pittsburghese goes to the opera

On a Sunday afternoon in November I am at the Benedum Center with hundreds of fellow Pittsburghers watching a performance of Mozart’s The Magic Flute. It’s the second act, and Papageno the bird-man has just found his true love. The English super-titles help us decipher what he is saying as he starts to exit the stage. But then the English words over our heads stop matching what we’re hearing: Papageno is telling us that the “Stillers are playin’ dahntahn n’at, and they’re only four points down!” The audience bursts into laughter. Papageno has updated us on the score of the Pittsburgh Steelers game, and he’s done it in Pittsburghese. It’s a Pittsburgh moment in an event that could otherwise have been anywhere, a low-culture moment in an otherwise high-culture afternoon, a moment that reminded us of who we were and where we were.

Such moments are common here in the Steel City. People put on performances of Pittsburghese when they talk about the Steelers and the Pirates, when they talk about what Pittsburgh is like and what Pittsburghers are like, when they want to show they are Pittsburghers and when they want to mock Pittsburghers. Why? How has the local dialect become such a powerful symbol of local identity?

A hundred years ago, thousands of European immigrants were pouring into the Pittsburgh to work in the area’s steel mills and related industries. They spoke a variety of languages, and some never learned much English. But their children did, and these second-generation immigrants wanted to sound like the locals, not like their accented old-world parents. So they learned the local way of speaking English, a dialect of English that we can easily trace back to the earliest Scots-Irish settlers in the area. They learned to say “slippy” instead of “slippery,” “redd up” for “tidy up,” and “youn’s” or “yinz” for “you guys.” They learned the local accent, and they learned to form phrases the way local kids did, saying “needs washed” instead of “needs to be washed” and using “whenever” in sentences like “I was 14 whenever we moved here.” Nobody ever told them any of these things were wrong, or even non-standard: everyone in Pittsburgh spoke this way, even the local aristocrats.

Things stayed the same for several generations. Children followed their parents into the mills, the mines, or management. Working-class Pittsburghers didn’t have the money to travel, and upper-class Pittsburghers tended to marry locally. With so little social or geographical mobility, nobody had any reason to realize they spoke differently than anyone else.

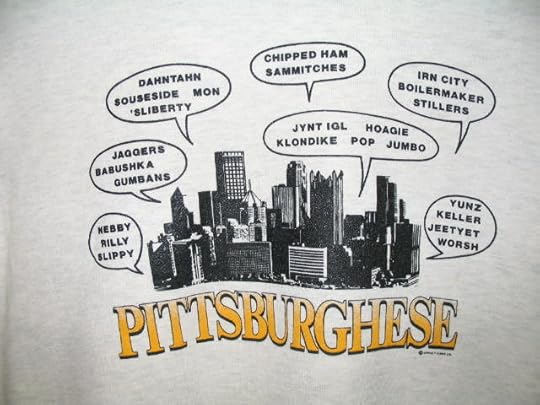

A Pittsburghese sweatshirt. Courtesy of Barbara Johnstone

World War II made Pittsburghers mobile in new ways, with men and women going off to war and encountering people from elsewhere, people who commented on how they spoke. Women began to move into new kinds of jobs, where it sometimes mattered how you talked so that you had to be careful not to sound too working-class. Pittsburgh sounds, words, and structures started to acquire social meaning, differentiating people from one another along class and regional lines.

By the 1960s, articles in the Pittsburgh papers listed words and phrases that outsiders noticed when they encountered Pittsburghers. The word “Pittsburghese” was coined. Although their local accents sounded normal to them — they talked the same as everyone they knew — younger Pittsburghers knew that people from elsewhere thought they sounded funny. In 1982, Pittsburghese acquired a dictionary, in the form of a little book called How to Speak Like a Pittsburgher that defined local words and spelled them in ways that suggested how they sounded. The book was wildly popular.

Pittsburgh’s steel industry had been ailing for decades, and in the 1980s it collapsed seemingly overnight. A generation of young people who had expected to live as their parents had were suddenly without prospects. The city’s population shrank dramatically as young Pittsburghers moved away. Many of these “baby-boomers” were third- or fourth-generation immigrants who no longer identified with their grandparents’ homeland or religion. They thought of themselves as Americans, and as Pittsburghers. But what did it mean to be a Pittsburgher if you weren’t a proud, tough, laborer? What could you hang your identity on? The local football team was one hook, and former Pittsburghers are fanatical fans. Pittsburghese was another. Being a Pittsburgher meant using the sounds and words and phrases that people identified with the city. Pittsburghese came to serve as a shorthand symbol for what it meant to be from Pittsburgh. Ex-Pittsburghers joined online forums to talk about how they talked and exchange words they remembered from their childhoods. They told stories about being recognized as Pittsburghers because of their accents or the words they used.

Ironically, exactly the same factors that make regional differences disappear — social and geographical mobility caused by economic change — also make people become aware of regional differences and celebrate them. Fewer and fewer young Pittsburghers use Pittsburghese in daily life, but more and more you hear short performances of Pittsburghese when people want to make a point about being local or about how local people sound. Young and middle-aged Pittsburghers alike love to hear Pittsburghese in the mouths of radio DJs, talking dolls, and YouTube video stars like Pittsburgh Dad, characters that poke gentle fun at the provincial Pittsburghers of the past as they celebrate the city’s distinctiveness. Go Stillers!

Barbara Johnstone is Professor of Linguistics and Rhetoric at Carnegie Mellon University and the author of Speaking Pittsburghese: The Story of a Dialect.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Dialect and identity: Pittsburghese goes to the opera appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesYour Place of the YearEllie Collins’ top books of 2013A year of reading with the OUP Publicity team

Related StoriesYour Place of the YearEllie Collins’ top books of 2013A year of reading with the OUP Publicity team

Extreme makeover: England’s new defamation law

Britain’s complicated and claimant-friendly defamation laws, honed in important respects in the Star Chamber, have rightly attracted worldwide criticism. In 2008, the New York State legislature condemned their deployment against American nationals as ‘libel terrorism’. In 2010, the US Congress passed a law with the express purpose of preventing British defamation judgments from being recognized and enforced in the land of the First Amendment.

The Defamation Act 2013, which comes into force in England and Wales on 1 January 2014, is thus an occasion for reflection. The culmination of years of lobbying, consultation, inquiries, and reports, the new law contains the most wide-ranging reforms that have ever been attempted to this vexed field. Generally speaking, although not uniformly, the changes are media friendly, tilting the balance towards greater protection for freedom of expression, and making it harder for claimants to bring actions. That a recalibration of the law towards freedom of expression was possible is remarkable: the prestige of the media, and its capacity to influence lawmakers, is at a low ebb in the wake of the revelations before the Leveson inquiry into the culture, practices, and ethics of the press.

The signature reform of the 2013 Act is to be found in section 1, which provides that defamation actions will no longer be permitted to proceed unless the claimant has suffered, or is likely to suffer, serious reputational harm or, in the case of bodies that trade for profit, serious financial loss. The reform may ultimately be of more symbolic than practical import. Courts had already, in recent years, developed and given effect to principles and procedures for weeding out trivial defamation claims. Nonetheless, the provision will serve to deter, and fortify courts in bringing to an end, defamation claims of marginal merit.

Bow Street Magistrates Court (1879), London WC1 by Julian Osley, Creative Commons via Wikimedia Commons

The most significant reform in the new law is likely to prove to be the new defence of honest opinion, which replaces the ancient common law defence of fair comment. The new defence is capable of protecting honestly expressed opinions—as opposed to assertions of fact—on any subject. The defence appears to be capable in some circumstances of protecting the expression of opinions that could have been held by an honest person on the basis of an incomplete or distorted view of the underlying facts, or on the basis of facts that were not known to the publisher and upon which the opinion was not based. It is in those respects a radical liberalization of the law. The new defence is a more important reform than the equally vaunted statutory codifications of the defence of truth, and of the Reynolds defence for false, but responsibly prepared, publications on matters of public interest.

There are a number of internet-friendly reforms in the new law. Courts will no longer have jurisdiction to hear and determine most defamation actions brought against secondary publishers of defamatory statements, including internet content hosts and service providers. There is a new defence for operators of websites in cases involving allegedly defamatory statements that have been posted by others online. Operators in such cases, including operators of news sites which allow reader comments and other online forums, will generally have an effective immunity from suit where they comply with tightly prescribed timeframes and act as a point of liaison between complainants and the anonymous posters of allegedly defamatory statements. A single publication rule has been introduced. Aggrieved persons will generally have only a year from the time when an offending statement first became publicly accessible to bring a claim. In most cases, they will no longer be able to sue in respect of statements first published long ago that remain accessible in online archives, even where new facts have since emerged that change the complexion of the statement.

There are other notable reforms. Inspired in part by the controversy that erupted when the British Chiropractic Association sued Simon Singh over an article in The Guardian, there is a new defence to protect defamatory statements appearing in scientific and academic articles in peer-reviewed journals, and in assessments of the merit of such articles. There are other liberalizations to the categories of report that attract absolute and qualified privilege.

The rather over-stated problem of libel tourism—the phenomenon of foreigners coming to London to take advantage of its defamation laws in cases with limited links to the jurisdiction—has been tackled by a provision that will operate, in most cases, to prevent actions from being brought in England and Wales against persons domiciled outside the European Economic Area.

Courts have been given new powers to order the publication of summaries of their judgments—despite protests of interference with editorial integrity—and to stop the secondary distribution of statements that have been found to be unlawful. The presumption in favour of trial by jury has been reversed.

Ultimately, the 2013 Act does little to simplify the complexity of this notoriously difficult branch of the law. As with reforms past, it mostly bolts new principles onto the rusting hulk of the existing structure of the centuries’ old cause of action: a structure that no-one, starting from scratch, would devise, but with which England and Wales, and the rest of the common law world, have been saddled. It contains many contestable questions of construction and apparently unintended consequences: more than enough to justify a new text on the English law of defamation. Disappointingly, the reforms have, with only minor exceptions, not been taken up in Scotland or Northern Ireland, thereby opening the door to the emergence of a cottage industry in intra-UK libel tourism in favour of Edinburgh and Belfast.

Nonetheless, the broad thrust and direction of the 2013 Act is to be welcomed. London may well cede its crown as the libel capital of the world to Sydney or Toronto. For that, the tireless promoters of reform—particular Liberal Democrat peers Lord Lester and Minister of State for Justice Lord McNally—deserve admiration and thanks.

Dr Matthew Collins SC is a Melbourne-based barrister, a Senior Fellow at the , and the author of The Law of Defamation and the Internet (OUP: 2001, 2005, 2010). His new book, Collins on Defamation, the first comprehensive analysis of the implications of the Defamation Act 2013, will be published by OUP in March 2014.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Extreme makeover: England’s new defamation law appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPreparing for AALS 2014Best international law books of 2013Google Books is fair use

Related StoriesPreparing for AALS 2014Best international law books of 2013Google Books is fair use

A New Year’s Eve playlist

After reflecting on music that they were thankful for a few weeks ago, we have now asked Oxford University Press staffers to share music that reminds them of the New Year. Whether that means a song that points towards a fresh start, one that is (more or less) literal, or one by a band whose very name proclaims newness (German krautrockers Neu!), we’ve pulled together a list of songs to capture that sense of in-between-ness, looking back and looking forward – and hopefully being happy while doing it.

“The New Year” – Death Cab for Cutie

This isn’t exactly a light-hearted, optimistic song about the New Year, but Transatlanticism is one of those albums I discovered in high school that will forever have a place in my heart. I still listen to this song every New Year’s Day.

– Lauren Hill, Associate Publicist

“Für Immer” – Neu!

Neu! is unbeatable for quality space-out music, but they also can put you in mind of the passage of time. The continuous drum pattern that holds up and buoys along the 11-minute “Für Immer” gradually makes you aware on a deep level of the seconds flowing by. It’s a comforting feeling.

– Owen Keiter, Associate Publicist

“You Can Get It If You Really Want” – Jimmy Cliff

Jimmy Cliff’s “You Can Get It If You Really Want” has always struck me as that that perfect song that balances both the inspiration and aspiration that I feel around New Year’s. And the horns in this song…who doesn’t hear the horns in this song, smile, and feel capable, invincible, that all things are possible? It is an optimistic song that reminds me that anything/everything is possible, “but you must try, try and try, try and try.”

– Christian Purdy, Director of Publicity

“This Will Be Our Year” – The Zombies

“This Will Be Our Year” has always been my favorite track from The Zombies’ Odessey and Oracle, an album that’s now critically acknowledged as one of the best to come out of Britain in the 1960s. On the surface, it sounds pretty characteristic of the vaguely corny ’60s sunshine pop you hear on oldies stations, but there’s a gravity (desperation?) in the lyrics about new hope and redemptive love that separates it from a chart topping credits-roller like “Happy Together.” At any rate, it’s a grand and beautifully triumphant song, and – from my perspective, at least – a strong candidate for the all-time anthem to new beginnings.

– Dan Poindexter, Assistant Marketing Manager, Journals

“Denim Jesus” – Journalism

This song by Journalism, my friend and colleague Owen Keiter’s band (NOT on Spotify – neither are The Beatles) must have been one of the best new songs I heard this year, and I watched this video collage, which combines an anatomy film and a 1920’s French film, several times. The bridge at 3:51 is the best part!

– Jeremy Wang-Iverson, Senior Publicist

“Treat Me Like a Baby” – Night Engine

With all the focus on rebirth around this time and the bizarre personification “Baby New Year”, I oddly got stuck on Night Engine’s track for my NYE listening choice. While their song is about frequent comparisons young musicians are subject to – with the implication of unoriginality and inability – I’d like to crowbar a New Year’s appropriate meaning in: don’t let any apparent echoes of the past cloud your judgment — treat the night and the coming year as something entirely new. Plus you can dance around to it while waiting for the clock to chime midnight.

– Alice Northover, Social Media Manager

“Gassenhauer” – Carl Orff

Probably better known through Hans Zimmer’s rewritten version on the True Romance soundtrack, Orff’s gentle, marimba-driven ditty has appeared in scores of movies and television shows. One of those pieces that you recognize immediately once you hear it, this brief piece sounds old and new all at once, hitting that bittersweet spot between ending and beginning. Like the recognition that a sunset here is a sunrise somewhere else.

– Taylor Coe, Marketing Assistant

“Happy” – Pharrell Williams

This song makes me so…well, happy! It is a refreshing, joyous song that wakes me up and makes me feel ready to take on the new year! Also, the music video is just amazing. YouTube has a normal music video, but visit 24hoursofhappy.com for the interactive experience. There are some amazing dancers and funny moments in the video, but 4:32.30 pm is the cutest moment that I have found so far.

– Christie Walsh-Loew, Assistant Marketing Manager

“2080” – Yeasayer

This holiday is always a strange mix of retrospection and looking forward, evaluating and dreaming. “It’s a new year, I’m glad to be here,” reminds me that I can appreciate everything we have now and still aspire to a better future (hopefully one that I see before 2080).

– Kate Pais, Marketing Assistant

“Up, Up & Away” – Kid Cudi

It just has such a fresh beat and a sound that hits you like a baptism. Every time I hear this song I either want to run a marathon or take a quick drive in a fast car.

– Sarah Hansen, Publicity Assistant

Taylor Coe is a Marketing Assistant at Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A New Year’s Eve playlist appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA New Year’s Eve playlistOxford Music in 2013: A look backEllie Collins’ top books of 2013

Related StoriesA New Year’s Eve playlistOxford Music in 2013: A look backEllie Collins’ top books of 2013

December 30, 2013

Top 10 OUPblog posts of 2013 by the numbers

An OUPblog reader?

What have you, the OUPblog reader, been looking for this year? Let’s find out with our top ten posts published this year, according to pageviews, in descending order.(10) “The many “-cides” of Dostoevsky” by Michael R. Katz

(9) “The five most common insults and slogans of medieval rebels” by Jan Dumolyn and Jelle Haemers

(8) “Five facts about the esophagus” (from Stephen Hauser’s Mayo Clinic Gastroenterology and Hepatology Board Review)

(7) ““Third Nation” along the US-Mexico border” by Michael Dear

(6) “How come the past of ‘go’ is ‘went?’” by Anatoly Liberman

(5) “10 moments I love in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby that aren’t in Baz Luhrmann’s film” by Kirk Curnutt

(4) “Why does this baby cry when her mother sings?” by Siu-Lan Tan

(3) “A few things to remember, this fifth of November” by Philip Carter

(2) “Maybe academics aren’t so stupid after all” by Peter Elbow

And the number one blog post of the year is…

(1) “10 facts about Galileo Galilei” by Matt Dorville

I should note that many of our top posts of 2013 were in fact published in previous years, including “Ten Things You Might Not Know About Cleopatra” (2010), “Quantum Theory: If a tree falls in forest…” (2011), and “Semi-legal marijuana in Colorado and Washington: what comes next?” (2012).

Alice Northover is editor of the OUPblog and Social Media Manager at Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Top 10 OUPblog posts of 2013 by the numbers appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTop OUPblog posts of 2013: Editor’s picksA year of reading with OUP authorsYour Place of the Year

Related StoriesTop OUPblog posts of 2013: Editor’s picksA year of reading with OUP authorsYour Place of the Year

Your Place of the Year

As we wrap up the Oxford Atlas Place of the Year project for 2013, we thought we’d open the floor for some personal Places of the Year — that is, locations which have made a significant impact in our individual lives in 2013. Below are year-end picks from some OUP USA staffers. Feel free to add your contributions in the comments section. Thanks from the Place of the Year committee for coming with us on yet another great season of geographical exploration!

Sam Blum, Publicity Assistant:

My place of the year is my Jiu-Jitsu gym, Alliance Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu NYC. Not only does it serve as a place to clear my mind when the craziness of this city gets too loud, but it’s afforded me great, long-lasting friendships that are truly invaluable.

The beach on Hilton Head Island, SC. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Alyssa Bender, Marketing Associate:

My place of the year for 2013 is Hilton Head Island, South Carolina. Not only is it a place I’ve gone to every September for just about my whole life (and therefore one of my favorite places ever), it is where my fiancé and I got engaged. 2013 has been a fantastic year—in great part due to Hilton Head!

Jeremy Wang-Iverson, Senior Publicist:

This year I’m choosing Duke Farms, Hillsborough, NJ. I visited Duke Farms 3-4 times over the summer; it’s great for an easy day trip out of the city. It’s walking distance from the Somerville station on NJ Transit, so you don’t even need a car to get there. And it’s free!

Penny Freedman, Trade Reference Coordinator:

My place of the year, and possibly my life, is the New York City subway system. I spend at least 10 hours a week on the subway, and it’s where I witness the most bizarre things that stand out the most in my mind throughout the year. This year’s winning moment goes to the man who took his desk chair with him for comfort’s sake.

Playa Samara, Costa Rica. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Purdy, Director of Publicity:

Fresh fruit, delicious food, $2 beers & free boca happy hours, $3 cigs, wandering mariachi, live music on the beach, endless cribbage with Canadians, and diverse population of vacationers rivaling the membership of the UN General Assembly: 2013 was the year I discovered unrivaled hospitality and happiness at the Hotel Rancho de la Playa in Playa Samara, Costa Rica. A hammock at Lo Que Hay around the corner from Rancho comes in a very close second.

Owen Keiter, Associate Publicist:

I’m going to have to go with Big Snow Buffalo Lodge in Bushwick, Brooklyn. This low-key, semi-official, probably-illegal music venue and community space was shut down over the summer when one of the owners was injured as a bystander in an unrelated shooting. (He’s okay now.) Before that, though, Big Snow was the home base of the Bushwick music and arts scene – the kind of place you’ll be reading about in musicians’ memoirs in 30 years. New York music won’t be the same without it.

Oxford’s Atlas of the World — the only world atlas updated annually, guaranteeing that users will find the most current geographic information — is the most authoritative resource on the market. The milestone Twentieth Edition is full of crisp, clear cartography of urban areas and virtually uninhabited landscapes around the globe, maps of cities and regions at carefully selected scales that give a striking view of the Earth’s surface, and the most up-to-date census information. The acclaimed resource is not only the best-selling volume of its size and price, but also the benchmark by which all other atlases are measured.

The Oxford Atlas Place of the Year 2013 is Syria. The Oxford Atlas Place of the Year is a location — from street corners to planets — around the globe (and beyond) which has attracted a great deal of interest during the year to date and judged to reflect the important discoveries, conflicts, challenges, and successes of that particular year. Learn more about Place of the Year on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only geography articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Your Place of the Year appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Oxford Atlas Place of the Year 2013 is…Seven facts of Syria’s displacement crisisPlace of the year 2013: Spotlight on Syria

Related StoriesThe Oxford Atlas Place of the Year 2013 is…Seven facts of Syria’s displacement crisisPlace of the year 2013: Spotlight on Syria

Preparing for AALS 2014

As 2013 draws to a close, we take the time to ask ourselves, “What does the coming year hold?” At this year’s Annual Meeting, the Association of American Law Schools asks attendees a similar question, “What does the future hold for legal education?”

The 2014 AALS Annual Meeting will take place 2-5 January 2014 at the New York Hilton Midtown, located in the heart of New York City. The theme of this year’s meeting is “Looking Forward: Legal Education in the 21st Century.”

The 2014 AALS Annual Meeting will take place 2-5 January 2014 at the New York Hilton Midtown, located in the heart of New York City. The theme of this year’s meeting is “Looking Forward: Legal Education in the 21st Century.”

The AALS is a non-profit educational association of 176 law schools representing over 10,000 law faculty in the United States. The largest gathering of law faculty in the world will come together at this year’s Annual Meeting.

Conference highlights include:

Presidential Program – a Joint Program of the AALS and European Law Faculty Association titled Developments and Trends in European Legal Education: What We Can Learn

Presidential Workshop on Tomorrow’s Law Schools: Economics, Governance, and Justice, a day-long follow-up program to the highly attended 2012 Annual Meeting Workshop The Future of the Legal Profession and Legal Education

Quantitative and Qualitative Research Surveys: The Committee on Research presents two intensive 10-hour courses on statistical analysis in the legal context. Choose between quantitative and qualitative.

Law and Film Series: Thursday, 2 January, at 7:30 p.m. a double feature of two classic films, The Wrong Man and Inherit the Wind. On Saturday, 4 January, at 8:00 p.m. a double feature of competitively selected documentaries Central Park Five and The Art of the Steal will be shown.

More program information can be found online.

We hope to see you at Oxford’s booth (#617) where you can take advantage of the following:

The latest in law publishing, all at a discounted conference price

Free trial access to our suite of online products for a month

New journal launches, including London Review of International Law and The Chinese Journal of Comparative Law

Pick up an article collection from International Journal of Constitutional Law in political science, international studies, and law & society. This collection is free online for a limited time.

Watch a demo and learn about our new online law resources such as Oxford Constitutions of the World and Oxford Scholarly Authorities on International Law

You can also order books online with our Conference Discount! Just visit oup.com/us and enter promo code 32383 in the top right-hand corner.

This year many OUP authors will be speaking on a number of different panels at AALS, including:

Mark A. Drumbl, Class of 1975 Alumni Professor at Washington & Lee University School of Law; author of Reimaging Child Soldiers in International Law and Policy (HB and PB, April 2012); and contributor to Tim Waters’ The Milosevic Trial: An Autopsy (Jan 2014) and Kevin Jon Heller & Gerry Simpson’s The Hidden Histories of War Crimes Trials (Dec 2013)

Mary L. Dudziak, Asa Griggs Candler Professor of Law, Emory Law School; author of War Time: An Idea, Its History, Its Consequences (HB Feb 2012, PB Sept 2013)

Eleanor M. Fox, New York University School of Law; co-editor with Michael Trebilcock of The Design of Competition Law Institutions: Global Norms, Local Choices (Mar 2013)

Vicki C. Jackson, Thurgood Marshall Professor of Constitutional Law at Harvard Law School; author of Constitutional Engagement in a Transnational Era (HB Dec 2009, PB Mar 2013)

James Kraska, Mary Derrickson McCurdy Visiting Scholar, Division of Marine Science and Conservation at Duke Nicholas School of the Environment; author of Maritime Power and the Law of the Sea: Expeditionary Operations in World Politics (Jan 2011)

Jenny S. Martinez, Professor of Law and Justin M. Roach, Jr., Faculty Scholar at Stanford Law School; author of The Slave Trade and the Origins of International Human Rights Law (HB Jan 2012, PB Mar 2014); and contributor to the Oxford Handbook of International Human Rights Law (Dec 2013), and the Oxford Handbook of Comparative Constitutional Law (HB Jul 2012, PB Dec 2013).

Mark Tushnet, William Nelson Cromwell Professor of Law at Harvard Law School; contributor to the upcoming book The “Long Decade”: How 9/11 Changed the Law (Apr 2014) edited by David Jenkins, Anders Henriksen, and Amanda Jacobsen.

In your downtime check out these spots as selected by Oxford’s NYC staff.

Brunch in the East Village

Staten Island Ferry – Free views of The Statue of Liberty, Ellis Island, and the skyscrapers and bridges of Lower Manhattan

Winter Village at Bryant Park

Neue Galerie – Museum for German and Austrian Art

Pearl Oyster Bar

Free Tours by Foot

The Brooklyn Museum of Art

See you at the conference!

Sinead O’Connor is a Law Marketing Associate at Oxford University Press

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image via iStockphoto.

The post Preparing for AALS 2014 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEllie Collins’ top books of 2013A year of reading with the OUP Publicity teamReflections on a year in OUP New York

Related StoriesEllie Collins’ top books of 2013A year of reading with the OUP Publicity teamReflections on a year in OUP New York

Is science inconsistent?

An important part of life is judging when to be sceptical about scientific claims, and when to trust in those claims and take actions accordingly. Often this comes down to the task of weighing up evidence. But we might think that when the science in question is internally inconsistent, or self-contradictory, we have an easy decision. In such circumstances the science contravenes one of our most basic conditions on useful, or trustworthy, information. As Karl Popper put it in 1940, “If one were to accept contradictions, then one would have to give up any kind of scientific activity: it would mean a complete breakdown of science.”

It comes as a surprise, then, to learn that the history of physics is littered with (a) inconsistencies going unnoticed for 10s, or even 100s, of years, (b) inconsistencies which are noticed but which are tolerated, and (c) scientific concepts which seem to be self-contradictory. We find all of these things not in the dark corners of science, but instead in some of the most prominent theories, and put forward by ‘great scientific minds’. If we really want to be able to judge the trustworthiness of scientific claims, it turns out Popper’s method of ruling out all inconsistencies is far too crude. Inconsistency and science often can go hand in hand.

Karl Popper

One can start to make sense of this by noting that, although inconsistency rules out any chance of truth, a large part of science is not about ‘the truth’. Instead science is predominantly about ‘getting results’. Oliver Heaviside put it best in 1899: “Shall I refuse my dinner because I do not fully understand the processes of digestion? No, not if I am satisfied with the result. . . . First, get on, in any way possible, and let the logic be left for later work.” What does ‘getting on’ in science mean, if not trying to determine the true nature of reality? Don’t we want to know what really killed off the dinosaurs, what ‘dark energy’ really is, and so on?The answer is ‘yes and no’. Sometimes truth drives scientists, but often they are more than happy to solve some outstanding problem, or make a useful prediction. Often, the word ‘truth’ is left out of science completely – left for the philosophers to think out. The early calculus is a prime example of how a certain inconsistency in one’s thinking is neither here nor there if one is ‘getting results’. The eminent Swiss mathematician Johann Bernoulli was one of the great mathematical minds of his age, and yet in an important essay written in 1691 he stated: “A quantity, which is diminished or increased by an infinitely small quantity, is neither diminished nor increased.” For most of his contemporaries (especially Bishop George Berkeley!), this sort of thinking was plain contradiction, or at least ‘incomprehensible metaphysics’. Nonetheless, Bernoulli and others found an appeal to ‘infinitely small quantities’ extremely useful for solving mathematical problems which had eluded the best minds for centuries. As Heaviside would recommend, he had found a way to ‘get on’, and was ‘leaving the logic for later work’.

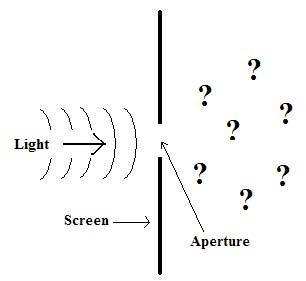

Kirchhoff’s problem

But how can one trust Bernoulli’s ‘results’ in these circumstances? If one starts with something ‘absurd’, doesn’t that suggest that one’s conclusions will also be absurd, or at least definitely false? Actual scientific practice flies in the face of this concern. In general, in science – and especially physics – it is common practice to adjust one’s hypotheses so as to make the reasoning easier. These ‘adjustments’ usually involve moving from an assumption that has a chance of being true, to an assumption one knows, or believes, to be false. In such circumstances one can end up reasoning with an inconsistent set of assumptions, strictly speaking, since one combines things one believes to be true with things one believes to be false. Now it is well known that if one starts with an inconsistency one can, logically speaking, derive any result one wants. But in recent decades there has been increasing appreciation that scientific reasoning both is, and should be, something rather different from simple logical deduction. As Paul Feyerabend already put it in 1978: “The objection that a contradiction entails every statement applies to special systems of logic, not to science which handles contradictions in a less simpleminded fashion.”

A nice example to bring this to life is Gustav Kirchhoff’s theory of the diffraction of light at an aperture – a case that has puzzled scientists for more than a century. In his reasoning Kirchhoff made an assumption concerning the behaviour of incident light within the aperture of a plane screen. But Kirchhoff’s conclusions contradict this very assumption! How then can this be useful, or trustworthy, science? The truth is, Kirchhoff’s conclusions are extremely accurate and useful in a great many respects; so long as one is careful about the ‘respects’, one can trust the predictions. And this needn’t be surprising, since Kirchhoff’s starting assumptions, despite being somehow inconsistent, are also largely approximately true. The final lesson is this: if one starts with false assumptions one can no doubt reach false conclusions. But often one can also reach useful, or even true conclusions. It all depends on how one goes about using them.

Peter Vickers completed his undergraduate BSc in Mathematics and Philosophy at the University of York in 2003. This was followed by an MA in History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Leeds, completed in 2005, and a PhD in the history and philosophy of science, also at the University of Leeds in 2009. Following a year teaching at Leeds, Vickers spent a year as a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Center for Philosophy of Science at the University of Pittsburgh, before returning to the UK in 2011 as a Lecturer in Philosophy at Durham University. He is the author of Understanding Inconsistent Science.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Karl Popper in the 1980s. By LSELibrary [no known copyright restrictions], via Wikimedia Commons; (2) Supplied by the author.

The post Is science inconsistent? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLogic and Buddhist metaphysicsBuddhism and biology: a not-so-odd coupleNon-belief as a moral obligation

Related StoriesLogic and Buddhist metaphysicsBuddhism and biology: a not-so-odd coupleNon-belief as a moral obligation

December 29, 2013

A year of reading with OUP authors

We surveyed a few of Oxford University Press’s authors to see what they thought were the best books of 2013…

“It was widely known that I would like this book; I was given it on my birthday three times. (And I’d already bought it for myself anyway.) Neil Gaiman’s Ocean at the End of the Lane is not merely another great fantasy story from the author of Sandman, friend of Dave McKean and husband to Amanda Palmer. This is a beautifully written book about how children interpret the behaviour of grown-ups. It’s his most personal work to date — and my favourite. Gaiman signed about 75,000 copies on his 2013 tour (according to his blog). When my family and I caught up with him in Manchester, UK, he spoke passionately about everything from Doctor Who to his new Sandman comics — and his wonderful speech ‘Make Good Art’. 2013 was a big year for Gaiman fans. Up close, he did look a little tired.”

— Dan Davis, author of Compatibility Gene: How Our Bodies Fight Disease, Attract Others and Define Ourselves

“My favorite book of the year was Laurent Binet’s HHhH. It’s about the assassination in Prague, 1942, of Reinhard Heydrich by a young Czech and a young Slovak, parachuted in from London. He calls it a historical novel, and it is sort of that, but the “narrative” alternates with journal entries from the semi-tormented author who hates historical novels, even if he’s trying to write one, and feels ashamed because he loves research and he loves getting facts right. It’s about trying to go back inside the past where the events you’re narrating happened, and how that’s heartbreakingly impossible, and about trying to do justice to all kinds of historical characters (except the loathsome Heydrich, who doesn’t deserve any justice!) even if they don’t fit into the plot – and most of all, about trying to reverse history to save the characters you’ve grown attached to. Laurent Binet is my favorite historian of the year, (even if he says the book is a novel) because he gets under the skin of all passionate historians.”

“My favorite book of the year was Laurent Binet’s HHhH. It’s about the assassination in Prague, 1942, of Reinhard Heydrich by a young Czech and a young Slovak, parachuted in from London. He calls it a historical novel, and it is sort of that, but the “narrative” alternates with journal entries from the semi-tormented author who hates historical novels, even if he’s trying to write one, and feels ashamed because he loves research and he loves getting facts right. It’s about trying to go back inside the past where the events you’re narrating happened, and how that’s heartbreakingly impossible, and about trying to do justice to all kinds of historical characters (except the loathsome Heydrich, who doesn’t deserve any justice!) even if they don’t fit into the plot – and most of all, about trying to reverse history to save the characters you’ve grown attached to. Laurent Binet is my favorite historian of the year, (even if he says the book is a novel) because he gets under the skin of all passionate historians.”

— Elizabeth Kendall, author of Balanchine and the Lost Muse: Revolution and the Making of a Choreographer

“Neil’s Gaiman’s Ocean at the End of the Lane: A man remembers. ‘I want to remember,’ his seven-year-old self says. Told from the perspective of a child marked by his realizations decades later of those experiences, this lovely book touches on memory making and the process of remembering, and that murky divide between children and grown-ups, what is real and imagined. ‘Truth is, there aren’t any grown-ups in the whole wide world,’ Lettie Hempstock tells the narrator. Naïve and nightmarish, this fantastical tale traces to the creation of this world, to ‘the language of shaping.’ Memories and worlds inhabit humans’ very beings, and bacteria can be instructed to leave a boy’s teeth alone. The seven-year-old/middle-aged narrator hovers — and it seems this book taps into my own somatic memory – between alienation and belonging; between the narrator’s encounters (what actually happens), the gaps (how he makes sense of it and how others engage with and interpret the same events), and the questions (if how one remembers can change whether events ever happened and the power of a magical old Mrs. Hempstock who can ‘snip and stitch’ to change what really happened). ‘I don’t remember,’ the middle-aged man says. ‘It’s easier that way,’ he’s told. Neil Gaiman reads his audiobook gently and starkly.”

— Abbie Reese, author of Dedicated to God: An Oral History of Cloistered Nuns

“There are few works that justify the adjective ‘magisterial,’ but Fredrik Logevall’s Pulitzer Prize-winning work, Embers of War: The Fall of an Empire and the Making of America’s Vietnam, seems worthy of the acclaim. In recounting the demise of the French empire in Indochina and the rise of American involvement in Southeast Asia after World War II, Logevall has written an essential work evaluating not only why nations go to war, but why they remain in war. This is history at its best—a compelling story combined with judicious analysis told through captivating, at times even gripping, narrative.”

“There are few works that justify the adjective ‘magisterial,’ but Fredrik Logevall’s Pulitzer Prize-winning work, Embers of War: The Fall of an Empire and the Making of America’s Vietnam, seems worthy of the acclaim. In recounting the demise of the French empire in Indochina and the rise of American involvement in Southeast Asia after World War II, Logevall has written an essential work evaluating not only why nations go to war, but why they remain in war. This is history at its best—a compelling story combined with judicious analysis told through captivating, at times even gripping, narrative.”

— Gregory Daddis, author of Westmoreland’s War: Reassessing American Strategy in Vietnam

“Vanessa M. Gezari’s The Tender Soldier is nominally an account of the so-called Human Terrain Teams, groups of anthropologists and academics who embedded within the US military in Afghanistan. This moving and deeply disturbing tale unmasks a lot of the intellectual and moral hubris that surrounds foreign involvement in Afghanistan. A must read for anyone interested in foreign policy or America’s role in the world.”

— Alex Strick van Linschoten, co-author of An Enemy We Created

“Max Boot’s Invisible Armies was a pleasure to read; a great look back at the long history of insurgencies that still trouble us today. Mark Mazetti’s The Way of the Knife is on the various ‘not-so-covert’ operations of the last decade and their consequences. It is the kind of book you wish had been out as some of these really bad ideas were happening. And on the fiction side: the Game of Thrones series, which I find myself rereading each year. It is addictive, wonderfully written, and bizarrely realistic (for a series with dragons in it…) to how people really act in politics and war.”

— P.W. Singer, co-author of Cybersecurity and Cyberwar: What Everyone Needs to Know

“My favorite books this year have been the set of studies by Christian Smith and colleagues about the religious and spiritual lives of American teenagers and emerging adults. In particular, I gained much from Souls in Transition: The Religious & Spiritual Lives of Emerging Adults and Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers. Who can forget the amazing descriptor ‘Moralistic Therapeutic Deism,’ as well as the popular understanding of God they discovered from their interviewees, that is, as combination Divine Butler and Cosmic Therapist. Great lecture material. I’ve also appreciated Charles Taylor’s A Secular Age. Even though these books came out a few years ago, they ‘have legs’ and are well worth your reading time.”

“My favorite books this year have been the set of studies by Christian Smith and colleagues about the religious and spiritual lives of American teenagers and emerging adults. In particular, I gained much from Souls in Transition: The Religious & Spiritual Lives of Emerging Adults and Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers. Who can forget the amazing descriptor ‘Moralistic Therapeutic Deism,’ as well as the popular understanding of God they discovered from their interviewees, that is, as combination Divine Butler and Cosmic Therapist. Great lecture material. I’ve also appreciated Charles Taylor’s A Secular Age. Even though these books came out a few years ago, they ‘have legs’ and are well worth your reading time.”

— Linda Mercadente, author of Belief without Borders

“A Just Defiance: Bombmakers, Insurgents, and the Treason Trial of the Delmas Four by Peter Harris is a gripping account of the last important trial of the apartheid era in South Africa. Unlike most books written by lawyers about cases in which they were involved, it is neither tedious nor self-aggrandizing. Instead, it reads like a legal thriller. Perhaps more importantly, it accurately and graphically describes the mood and events in South Africa in the late 1980s.”

— Ken Broun, author of Saving Nelson Mandela

“Rick Atkinson’s The Guns at Last Light is the final volume in his magisterial Liberation Trilogy, a sweeping history of World War II. This work covers the last year of the war in Europe and is distinguished by its focus on how armies are built and how organizations wage war. It’s meticulously researched and gracefully written.”

— Jeff Berry, co-author of The Outrage Industry

“On a recent trip to Powell’s Books in Portland, Oregon, I picked up Joan Didion’s The White Album (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux 2009 paperback edition; originally published in 1979). Didion provides an intimate insider’s perspective on both the seminal and mundane events that defined America during the late 1960s and 1970s. Over three decades old or more, these essays still feel alive and fresh, and seem to chronicle the cultural neuroses we still live with today including celebrity worship, consumerism, urban sprawl, surveillance and the limits of technology. But her portrayal of American life is as much sublime as dystopic; and as I read, I did feel myself Calfornia Dreamin’ circa 1974 a few times.”

“On a recent trip to Powell’s Books in Portland, Oregon, I picked up Joan Didion’s The White Album (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux 2009 paperback edition; originally published in 1979). Didion provides an intimate insider’s perspective on both the seminal and mundane events that defined America during the late 1960s and 1970s. Over three decades old or more, these essays still feel alive and fresh, and seem to chronicle the cultural neuroses we still live with today including celebrity worship, consumerism, urban sprawl, surveillance and the limits of technology. But her portrayal of American life is as much sublime as dystopic; and as I read, I did feel myself Calfornia Dreamin’ circa 1974 a few times.”

— Daniel Campo, author of The Accidental Playground

“Upon my return from World War II, my father presented me with a book on the world-famous architect Frank Lloyd Wright, ‘hopefully to inspire interest in a career in architecture.’ I was so taken with Wright that my life became involved with almost every aspect of the architect — which soon led me to return to France and Spain to study the tremendous variety of building styles; then a few years later to explore the archaeological ruins of Mexico and Central America, where I ultimately persuaded the American Museum of Natural History to allow me to produce a series of photographs of the pre-Columbian vestiges at a large number of sites; then back in the United States to conduct an ongoing series of architectural walking tours for New York University to study the many styles of domestic architecture in the heart of the city. This devotion to the influence of architecture on our daily lives resulted in the writing of my first book, a study of the Lower East Side’s historic religious institutions. There then followed a half-dozen guide books on New York and downtown Chicago; and in a completely different vein, a children’s book based on my experiences with birds that lived in my office at NYU. The pinnacle of my career as an author and architectural historian came last year with the publication by Fordham University Press of the Synagogues of New York’s Lower East Side: A Retrospective and Contemporary View.”

— Gerard Wolfe, author of Synagogues of New York’s Lower East Side

“My choice is Alan Ryan’s On Politics: A History of Political Thought from Herodotus to the Present, a 1000+-page epic-scale blockbuster originally published in 2012 by Allen Lane in the UK and by W.W. Norton & Company in the States, and reissued in a fat but handy paperback by Penguin Books in 2013. If one acid test of the quality of a book is the quality of the serious reviews it engenders or provokes, then On Politics passes that test with supreme ease, having been positively reviewed — and also profoundly if usually generously critiqued — on both sides of the English-speaking Atlantic and in Australasia by the likes of Adam Kirsch, Jeremy Waldron, Andrew Gamble, Mark Mazower and John Keane. Firmly located within both an Isaiah-Berlin-style ‘great thinkers’ tradition and a Western liberal-democratic ‘great books’ tradition, and open to left-field criticism precisely for choosing just that canon and that canonical approach, it is distinguished and defended by the brilliance of its analyses and the wit and wisdom on display throughout. The very subtitle is a challenge and provocation — was Herodotus a ‘political thinker’? The major themes broached, all subsumed by overarching questions of not just how best should we govern ourselves, but even should we govern ourselves, include the surely disturbing thought — going back to Herodotus — that modern (Western, liberal) states owe more to the ancient Persian empire than to ancient Greece (or the Roman Republic). The comparative-historical way that these themes and questions are broached by political-philosophical Alan Ryan (ex-Oxford Professor, now Princeton, again) makes the long meditated On Politics a must-read for anyone concerned to reconsider the current, global democratic deficit in the broadest long-run perspective.”

— Paul Cartledge, author of After Thermopylae

Stay tuned for more best of 2013 blog posts…

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A year of reading with OUP authors appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTop OUPblog posts of 2013: Editor’s picksEllie Collins’ top books of 2013A year of reading with the OUP Publicity team

Related StoriesTop OUPblog posts of 2013: Editor’s picksEllie Collins’ top books of 2013A year of reading with the OUP Publicity team

Top OUPblog posts of 2013: Editor’s picks

As editor of the OUPblog, I’m probably one of only a handful who read everything we publish over the course of the year. Even those posts which are coded and edited by our Deputy Editors I carefully read through in the hopes of catching any errors (some always make it through). So it’s wonderful to reflect on the amazing work that our authors, editors, and staff have created in 2013. Without further ado, here are a few of my favorites from the past year…

“Scenes from The Iliad in ancient art” : A slideshow of images from Barry B. Powell’s new translation of Homer’s The Iliad. I’ve been working with so many passionate OUP staff members who want to get the word out on this book, that I had to include at least one blog post on it.

“Doctor Who at fifty” by Matthew Kilburn : Even Whovians can learn more about the show and the people behind it in this piece.

“Violet-blue chrysanthemums” by Naonobu Noda and Yoshikazu Tanaka : I’m routinely impressed by the amazing work coming out of our science journals and it was wonderful to learn about the ground-breaking (and beautiful) work of genetic engineering these teams of scientists are undertaking.

“Oxford University Press and the Making of a Book” : A 1925 silent film by the Federation of British Industry on the workings of Oxford University Press. We’ve had this film around for a while (I’ve had the files for over a year), but it was wonderful to receive permission to share it with the world with the publication of the new History of Oxford University Press.

“The first ray gun” by Stephen R. Wilk : A fascinating examination of where fiction and science fiction interweave, as well as learning about Washington Irving as viral marketer.

“Heaney, the Wordsworths, and wonders of the everyday” by Lucy Newlyn : A poem by Dorothy Wordsworth, published here for the first time, by kind permission of the Wordsworth Trust.

“Booksellers in revolution” by Trevor Naylor : During yet another tumultous year in Egypt, our friends at the American University in Cairo Press sent us updates from Tahrir Square.

“Wrenching an etymology out of a monkey” by Anatoly Liberman : It’s a pleasure to read Anatoly’s work every week, and I always love to learn about the complex history of many words I’ve never thought twice about — monkey included.

“What happens when Walmart comes to Nicaragua?” by Hope Michelson : A fascinating set of questions — and results — when examining the impact of major supermarkets in local agricultural supply chains. (I made that sound boring — it isn’t.)

“Eating horse in austerity Britain” by Mark Roodhouse : When the horsemeat scandal erupted in Britain earlier this year, we were surprised to find it wasn’t the first one.

“The Oi! movement and British punk” by Matthew Worley : The association of certain punk music with skinhead activism is much more complex than it is often portrayed. I found the blog post and journal article very enlightening — breaking down what, how, and when these ideas became associated.

“Whose Odyssey is it anyway?” by Justine McConnell : Reclaiming the classics in a post-colonial world!

“The lark ascends for the Last Night” by Robyn Elton : I must reveal a certain jealousy of staff who work on our music products. They have a more intimate understanding of how music works than I can ever hope to achieve — and such warmth and generosity in sharing that knowledge.

“When are bridges public art?” by David Blockley : Blockley’s four criteria to judge whether a bridge is a piece of public art raise great questions about engineering, architecture, and the function of art itself.

“Crawling leaves: photosynthesis in sacoglossan sea slugs” by Sónia Cruz : You had me at “solar-powered sea slugs”.

And I must cut off the list here, or it will extend far too long — despite my urge to share more about dark matter, photosynthesis, and…

Alice Northover is editor of the OUPblog and Social Media Manager at Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Top OUPblog posts of 2013: Editor’s picks appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCrawling leaves: photosynthesis in sacoglossan sea slugsEllie Collins’ top books of 2013A year of reading with the OUP Publicity team

Related StoriesCrawling leaves: photosynthesis in sacoglossan sea slugsEllie Collins’ top books of 2013A year of reading with the OUP Publicity team

Ellie Collins’ top books of 2013

It will come as no suprise that OUP staff love to read. 2013 has been a bumper year for fiction and non-ficiton alike. Ellie Collins takes us through her favourites.

By Ellie Collins

Thomas Pynchon, Bleeding Edge, Jonathan Cape, Hardback

Thomas Pynchon may have a reputation for writing dense and difficult novels, but Bleeding Edge is something of a page-turner: a thought-provoking thriller. The novel follows Maxine Tarnow, a smart-talking, rogue fraud investigator with a pistol in her purse, and is set somewhere between New York in 2001, leading up to the events of 9/11, and the Deep Web – the dark, buried underworld of the internet, teeming with hackers, code-writers, criminals, and lost souls. Maxine’s investigations lead her into a series of fraught and disorienting encounters with a billionaire CEO, secret agents, drug-dealers, a man with a supernatural sense of smell, and a foot fetishist (amongst others), against a backdrop of weird parties, karaoke joints, a haunted hotel, an offshore waste disposal depot with its ‘luminous canyon walls of garbage’, and the unnerving virtual reality of DeepArcher – an online world, or program. Bleeding Edge melds strange coincidence, conspiracy, and the obtusely unexplained into a brilliant and far-reaching narrative that has stayed with me long after reading.

Elizabeth Taylor, Angel, Virago, Paperback

This darkly funny novel by Elizabeth Taylor introduces a young girl, Angel, who has ‘not a seed of irony or a grain of humour in her soul’, coupled with high-flown literary ambitions. At the age of sixteen, Angel finishes what she believes to be a masterpiece, wraps it up and sends it to Oxford University Press, ‘whose address she found in one of her old school books’. Angel’s self-belief and optimism are resplendent: ‘It might take two days, she supposed (but at most, she could not help adding), for the novel to reach Oxford; then she must allow another three days for the publisher to read it, which he could easily do, if he sat up late at night; and another two days (at most) for his reply to reach her. It would be a long week, with a long, long Sunday in it.’ The book tells the story of Angel’s career as a writer and her life, accompanied by a large, pungent dog named Sultan and – later – many, many cats. It paints a hilarious but bleak picture of a magnificent eccentric – at times exceptionally cruel, and at others pathetic, and strangely affecting. This is perfect fireside reading – comic and sad, witty and stylish.

Nicola Barker, Darkmans, Fourth Estate, Paperback

I have been interested in Nicola Barker as a writer for a long time, partly due to her interest in writing on high drama and the spectacularly outlandish in settings that are far from extraordinary: her latest novel, The Yips, is described as an ‘exhilarating tour de force’ that begins in the hotel bar of The Thistle in Luton. Darkmans had been recommended to me several times: set in contemporary Ashford, this 800+ page novel features ‘the deranged ghost of an evil, 500-year-old court jester’. The plot revolves around a large cast of characters who experience hauntings of various inventive kinds, and, though rooted firmly in the present for the most part, swings dizzyingly across centuries and narrative perspectives at times, in flashbacks and dreamlike hallucinations that occur during the malignant ghost’s possessions of some of the characters. Barker’s writing is bold, quick-witted, and well-paced; her characters are sharply drawn; and the scope of this zany novel is sweeping and ambitious. Though lengthy, this is a surprisingly quick read: don’t let the page count put you off.

Ian Donaldson, Ben Jonson: A Life, Oxford University Press, Paperback

Ian Donaldson’s biography of Ben Jonson is one of the most entertaining and incisive works of non-fiction that I have read for a while. Aside from the wealth of information the book provides on this important early modern dramatist, this biography is highly readable and offers important reflections on the nature of literary biography, and the difficulties inherent in presenting a biography of Jonson – who comes across as an ‘impersonator’: a figure adept at self-dramatization. The book opens with a brilliant and illuminating analysis of evidence surrounding the fact that Jonson appears to have been buried in a vertical position, and upside-down – standing on his head – and goes on to provide a historically rigorous, and extremely engaging, account of the events of Jonson’s life – events that seem often theatrical, somehow, themselves. Though academic in nature, anyone interested in early modern history, culture, and drama will find this a rewarding and fascinating read.

Zachary Mason, The Lost Books of the Odyssey, Fourth Estate, Paperback

I received a review copy of this book years ago, and had neglected it since then; a conference trip to Athens in the summer persuaded me finally to open it. I regret not doing it sooner. In simple, elegant prose Zachary Mason offers retellings of passages from Homer’s Odyssey, and reimagines the myths and legends of the minotaur in the labyrinth; the irresistible song of the sirens, ‘sprawled languidly under the stars, arms entwined’; and the near-invincible Achilles: ‘When he was drunk Achilles would take his knife and try to pierce his hand or, if he was very drunk, his heart. And thereby were the delicate blades of many daggers broken’. This is as much a book about the creation of myth, losing oneself in legend, and the relationship between fiction and memory as it is about sad monsters and endless journeys. The Lost Books of the Odyssey is a little, understated masterpiece.

George Saunders, Tenth of December, Bloomsbury, Paperback

An extraordinary collection of short stories: I have not come across anything quite like it before. George Saunders presents a set of modern fables: dystopian scenarios that seem alien but also deliberately, uncomfortably close, in which behaviour and emotions are controlled by the flick of a switch and the administration of drugs, young girls are imported and strung up as decorations across the lawns of affluent American homes, and a little boy is leashed like a dog to a tree in his backyard. These are dark, sometimes brutal, and sometimes beautiful tales, which unfold in deeply unsettling ways and are filled, often, with a kind of indescribable dread – but Saunders also conveys some hope: the last chapter is a story about rescue. A stand-out book: innovative, challenging, and provocative.

Ellie Collins is Senior Assitant Commissioning Editor for Philosophy at OUP. She also reviews theatre for Around the Globe, playstosee.com, and for the academic journal Cahiers Elisabethains, and likes tea, cats, and stuffed olives.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Ellie Collins’ top books of 2013 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA year of reading with the OUP Publicity teamOxford Music in 2013: A look backReflections on a year in OUP New York

Related StoriesA year of reading with the OUP Publicity teamOxford Music in 2013: A look backReflections on a year in OUP New York

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers