Oxford University Press's Blog, page 698

February 18, 2015

Crossing the threshold: Why “thresh ~ thrash”?

The previous post dealt with the uneasy history of the word threshold, and throughout the text I wrote thresh~ thrash, as though those were two variants of the same word. Yet today they are two different words, and their relation poses a few questions. Old English had the strong verb þerscan (þ = th in Engl. thresh), with cognates everywhere in Germanic. “Strong” means that a verb’s infinitive, past tense (preterit singular and preterit plural), and past participle show alternating vowels, as, for instance, in ride—rode—ridden or, even better, in be—was—were—been. Today thresh is “weak” (thresh ~ threshed ~ threshed), but German has retained the vestiges of the old paradigm (dreschen ~ drosch ~ (ge)droschen). Alongside þerscan, the form with æ in the root existed, namely þærscan (æ designated the sound of a in Modern Engl. thrash) and seems to have meant the same as þerscan. But thrash surfaced in English only in the 16th century as a doublet of thresh. It is anybody’s guess whether the modern pair is a continuation of the old one (if so, thrash must have been dormant or current in some unrecorded dialects for a very long time) or whether Early Modern English repeated the process attested in the ancient period and again produced a pair of comparable and almost identical twins. Such things happen. Considering how late thrash turned up in our texts, the second alternative looks more probable.

Even the best books prefer not to discuss this situation. Skeat has the entry Thrash, Thresh and says “Thresh is older,” a correct but somewhat cryptic remark. The Century Dictionary and H. C. Wyld’s The Universal Dictionary of the English Language, both usually so helpful in matters of etymology (regardless of whether their solutions carry conviction), are equally uninformative. Even the great Karl Luick, the author of the unsurpassed history of English sounds, sits on the fence, and that is where we too will stay. As noted, I will assume (with many others) that the modern doublets arose in Shakespeare’s lifetime, rather than continuing þerscan ~ þærscan. Nowadays the verbs are no longer synonyms, for thresh refers to beating corn (grain), and thrash to beating enemies and opponents, though we can also thrash out a problem. In the vocabulary of all languages, such division of labor between close neighbors is typical, unless one of them manages to oust its rival altogether and take over its senses.

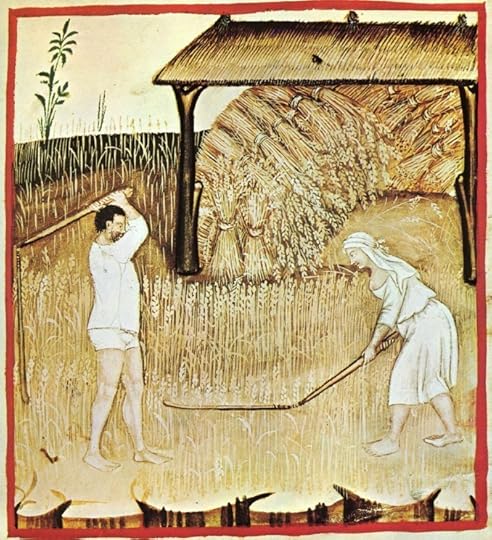

This is threshing

This is threshingThe distant etymology of thresh and the passage of thresh through the centuries need not delay us here. We should only observe that the old verbs began with þ- (= th-) and a vowel followed by r, whereas the present day forms are thresh and thrash, in which the vowel follows thr-. This is not a complication because r is the most frequent partner in the game of leapfrog called metathesis (compare Engl. burn and burst versus German brennen and bresten). The real problem is the variation e ~ a. We don’t know why Old English had two similar verbs, but, since we pretended that this fact is of no consequence to us, we have to explore only the causes of what happened in the sixteenth century.

The variation reminiscent of thresh ~ thrash occurs in all kinds of words. Sometimes it marks social dialects. Demned for damned, a form well-known from direct observation and often ridiculed in fiction and film, is a case in point. Unlike damned, thresh is a word of the neutral style, mainly used by peasants, but thrash is different, and Wilhelm Horn (see more about him below) ascribed the change to emphasis. Perhaps when one beats up an offender, the homey verb thresh is insufficient and in describing the process one wants to open the mouth wide. However tempting such conjectures (like references to sound imitation) may be, we have no way of proving them, which does not mean that they are necessarily wrong. In etymology, once linguists step outside trivial phonetic correspondences, very little can be “proved.”

In the middle of the fifteenth century, the spelling Wanysday “Wednesday” turned up several times. Later, nafew “nephew” appeared in private letters, along with “reverse spellings” (that is, with e for a): bechelor and cheryte for bachelor and charity. Henry Cecil Wyld (the same H. C. Wyld, whose name graces the title page of a superb one-volume dictionary) dug out many such examples, and some of them are discussed in Laut und Leben (“Sound and Life”), a book by Horn-Lehnert (Lehnert was the editor of his teacher’s posthumous opus magnum.) Horn also thought that frantic, which superseded frentic in the sixteen-hundreds, is an emphatic form. Indeed, the word’s expressive meaning does not contradict such a hypothesis. The adjective goes back to French frénétique. The change of e to a ruined for English speakers the ties between frantic and frenzy. In dialects, the form franzy is not uncommon.

Short i was also often broadened in the seventeenth century, as evidenced by such spellings as cheldren, denner, desh, shep, and tell for children, dinner, dish, ship, and till. Those changes need not strike us as absolutely chaotic and unpredictable. In the Early Modern period, the long vowels of English underwent a major restructuring known as the Great Vowel Shift. This is the shift that, among other things, drove a wedge between the names of the letters in English and in the other European languages. (For example, outside English, a is pronounced as Engl. a in spa.) In the languages of the Germanic group, when long vowels begin to change, short vowels usually follow suit and “try” to look more like their long partners. Consequently, a good deal of vacillation that looks odd can be expected.

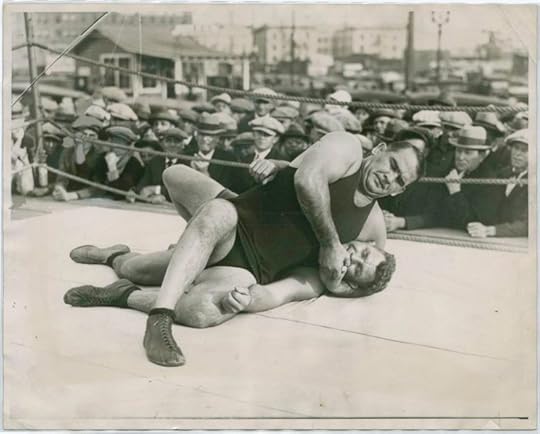

This is thrashing.

This is thrashing.The sound r frequently affects its neighbors (without establishing causal connections, we can at least say that in its vicinity all kinds of events take place). It would be tempting to ascribe the appearance of thrash from thresh to its influence, but the outwardly erratic behavior of vowels, so surprising to the scholar (a linguistic analog of Brownian motion!), makes all conclusions risky. It will be enough to say that the short vowels received an impulse rather than a command to modify their values and either obeyed it or remained stable. Fresh, fret, press, dress, crest, and so forth did not yield forms with a.

A few cases are special. I’ll cite only one. The word errand was pronounced in the eighteenth century and some time later as arrand, though, for some reason, spelled with an e. The pronunciation made sense, for the Middle English form was arunde. Language teachers suggested that perhaps people pronounce this word according to its visual image, and that is what they did. An amazing example of successful and evidently painless language planning! It follows that, when one encounters examples like thresh ~ thrash, all the facts have to be examined before even preliminary conclusions can be offered. (Politicians, with their penchant for buzzwords and clichés, would have probably announced here that all options are on the table.) So, as they teach in grade school: “Don’t generalize.”

When all is said and done, it seems that thrash owes nothing to its Old English lookalike, whose origin remains unclear, and that it developed from thresh for some vaguely stated phonetic reasons. To keep its distance from thrash, the new verb acquired a light-hearted, almost slangy tone. It also seems that the writing thresh ~ thrash with a tilde between them does not distort the history of either word.

Image credits: (1) Piantagione di grano, Tacuinum sanitatis Casanatense (XIV secolo). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) “Strangler” Lewis (above) Wrestling With His Sparring Partner. NYPL Digital Collections.

The post Crossing the threshold: Why “thresh ~ thrash”? appeared first on OUPblog.

International Studies Association Convention 2015: a conference and city guide

The International Studies Association Annual Convention will be held in New Orleans this week. The conference will be focusing on Global International Relations and Regional Worlds, A New Agenda for International Studies.

If you’re attending, stop by booths 202, 204, and 206 to take advantage of our conference discount. Be sure to check out some of the panels and lectures our authors will be giving.

Paul F. Steinberg, author of Who Rules the Earth? How Social Rules Shape our Planet and Our Lives, which won the Genner Innovative Teaching Award, is chairing and speaking in the session “Using Digital and Social Media in the Classroom and Beyond to Represent and Question Science” on Thursday from 10:30-12:15.

Tana Johnson, whose Organizational Progeny: Why Governments are Losing Control over the Proliferating Structures of Global Governance won the Chadwick F. Alger Prize for Best Book on International Organization and Multilateralism, will be speaking on the panel “Location, Location, Location: The Politics of IGO Headquarters” on Thursday, also at 10:30-12:15.

Best Book Award winner Shiping Tang, author of The Social Evolution of International Politics, is chair and speaker at “Interregional Dialogue: Regions, Ideas, and Global IR” on Thursday from 4-5:45.

Be sure to carve out some time to explore our beautiful host city. We’ve highlighted some key neighborhoods and sites to visit in New Orleans. Happy Mardi Gras!

Image Credit: New Orleans French Quarter by Sami99tr. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post International Studies Association Convention 2015: a conference and city guide appeared first on OUPblog.

“You said I killed you — haunt me, then!” An extract from Wuthering Heights

Are you part of the Oxford World’s Classics Readfing Group? The following is an extract from the current selection, Wuthering Heights, by Emily Brontë, taken from volume II, chapter II, pages 147-148 in the Oxford World’s Classics edition.

“Yes, she’s dead!” I answered, checking my sobs, and drying my cheeks. “Gone to heaven, I hope, where we may, everyone, join her, if we take due warning, and leave our evil ways to follow good!”

“Did she take due warning, then?” asked Heathcliff, attempting a sneer. “Did she die like a saint? Come, give me a true history of the event. How did — ”

He endeavoured to pronounce the name, but could not manage it; and compressing his mouth he held a silent combat with his inward agony, defying, meanwhile, my sympathy with an unflinching, ferocious stare.

“How did she die?” he resumed, at last — fain, notwithstanding his hardihod, to have a support behind him, for, after the struggle, he trembled, in spite of himself, to his very finger-ends.

“Poor wretch!” I thought; “you have a heart and nerves the same as your brother men! Why should you be so anxious to conceal them? Your pride cannot blind God! You tempt Him to wring them, till He forces a cry of humiliation!”

“Quietly as a lamb!” I answered, aloud. “She drew a sigh, and stretched herself, like a child reviving, and sinking again to sleep; and five minutes after I felt one little pulse at her heart, and nothing more!”

“And — and did she ever mention me?” he asked, hesitating, as if he dreaded the answer to his question would introduce details that he could not bear to hear.

“Her senses never returned — she recognised nobody from the time you left her,” I said. “She lies with a sweet smile on her face; and her latest ideas wandered back to pleasant early days. Her life closed in a gentle dream — may she wake as kindly in the other world!”

“May she wake in torment!” he cried, with frightful vehemence, stamping his foot, and groaning in a sudden paroxysm of ungovernable passion. “Why, she’s a liar to the end! Where is she? Not there — not in heaven — not perished — where? Oh! you said you cared nothing for my sufferings! And I pray one prayer — I repeat it till my tongue stiffens — Catherine Earnshaw, may you not rest, as long as I am living! You said I killed you — haunt me, then! The murdered do haunt their murderers. I believe — I know that ghosts have wandered on earth. Be with me always — take any form — drive me mad! only do not leave me in this abyss, where I cannot find you! Oh, God! it is unutterable! I cannot live without my life! I cannot live without my soul!”

He dashed his head against the knotted trunk; and, lifting up his eyes, howled, not like a man, but like a savage beast getting goaded to death with knives and spears.

I observed several splashes of blood about the bark of the tree, and his hand and forehead were both stained; probably the scene I witnessed was a repetition of others acted during the night. It hardly moved my compassion — it appalled me; still I felt reluctant to quit him so. But the moment he recollected himself enough to notice me watching, he thundered a command for me to go, and I obeyed. He was beyond my skill to quiet or console!

Heading image: Dancing Fairies by August Malmström. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post “You said I killed you — haunt me, then!” An extract from Wuthering Heights appeared first on OUPblog.

Stephen Hawking, The Theory of Everything, and cosmology

Renowned English cosmologist Stephen Hawking has made his name through his work in theoretical physics as a bestselling author. His life – his pioneering research, his troubled relationship with his wife, and the challenges imposed by his disability – is the subject of a poignant biopic, The Theory of Everything. Directed by James Marsh, the film stars Eddie Redmayne, who has garnered widespread critical acclaim for his moving portrayal: Redmayne has already won the Golden Globe for Best Actor in a Drama and the BAFTA prize for Leading Actor, and is tipped to take home the Best Actor Oscar at the Academy Awards in Hollywood on Sunday.

In recognition of the phenomenal success of The Theory of Everything and the subsequent resurgence of interest in Hawking’s work, we’ve compiled a list of free resources from leading academics across the spectrum of cosmology, which demonstrate the lively debate that Hawking’s theory has stimulated and his enduring influence in the fields of philosophy, mathematics, and physics.

“‘What place, then, for a creator?': Hawking on God and Creation” by William Lane Craig, published in The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science

“‘What place, then, for a creator?': Hawking on God and Creation” by William Lane Craig, published in The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science

“Scientists working in the field of cosmology seem to be irresistibly drawn by the lure of philosophy.” So begins William Lane Craig’s seminal paper in which he explains how Hawking has followed the lead of Carl Sagan in speculating on the philosophical implications of current cosmological models. Craig attempts to understand Hawking’s view of God’s role in the creation of the universe.

“On Hawking’s A Brief History of Time and the Present State of Physics” by Mendel Sachs, published in The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science

In the 1990s, there was a healthy resurgence of interest in the development of contemporary theoretical physics and cosmology, not only within the scientific community, but also among philosophers and historians of science. Hawking’s bestselling book, A Brief History of Time (1988), helped increase the popularity of such ideas. In this paper, Mendel Sachs evaluates the present state of physics by deconstructing Hawking’s unification of quantum theory and the theory of relativity, “two conflicting revolutions in science that form a basis of all modern physics and allied research areas”.

“Stephen Hawking’s cosmology and theism” by Quentin Smith, published in Analysis

“Stephen Hawking’s cosmology and theism” by Quentin Smith, published in Analysis

Does God exist? Or is Hawking’s wave-function law inconsistent with classical theism? In this paper, American philosopher Quentin Smith reflects on that perennial and divisive subject – the existence of God – implicit in Hawking’s theory, arguing that quantum cosmology and the classical theistic hypothesis are incompatible.

“Hartle-Hawking cosmology and unconditional probabilities” by Robert J. Deltete and Reed A. Guy, published in Analysis

In this provocative paper, Deltete and Guy question whether the quantum wave-function model of the universe, formulated by Hawking and fellow physicist James Hartle, provides an “unconditional probability for the universe to arise from literally nothing”. Masterfully weaving issues of physics, philosophy, and theism into their argument, Deltete and Guy debunk Quentin Smith’s interpretation of Hartle-Hawking cosmology.

“Time Travel and Time Machines” by Chris Smeenk and Christian Wüthrich, from The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Time (ed. Craig Callender)

Have researchers figured out the missing link to human time travel? And, according to Stephen Hawking, what are the necessary conditions to create a time machine? In this chapter, Smeenk and Wüthrich dare to illuminate the metaphysics behind the physical possibility of time travel and offer an overview of recent literature on “so-called time machines.”

“Philosophy of Cosmology” by Chris Smeenk, from The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Physics (ed. Robert Batterman)

How does philosophy inform the research of contemporary cosmologists? Certain scientific limitations, such as the nature of physical laws, provide fertile ground for philosophical inquiry, particularly regarding the science of our universe: “Due to the uniqueness of the universe and its inaccessibility, cosmology has often been characterized as ‘unscientific’ or inherently more speculative than other parts of physics. How can one formulate a scientific theory of the ‘universe as a whole’?” In one section of this chapter, Smeenk cites Stephen Hawking’s and others’ “Expanding Universe Models” as those that have effectively applied this philosophical inquiry to provide practical answers to some of the universe’s biggest questions.

The Story of Collapsing Stars: Black Holes, Naked Singularities, and the Cosmic Play of Quantum Gravity by Pankai S. Joshi

Studied by Roger Penrose and Stephen Hawking, visible naked singularities and black holes are considered two possible final fates of a collapsing star. This book describes one of the most fascinating intellectual adventures of recent decades, understanding and exploring the final fate of massive collapsing stars in the universe.

Introduction to Black Hole Physics by Valeri P. Frolov and Andrei Zelnikov

Introduction to Black Hole Physics by Valeri P. Frolov and Andrei Zelnikov

A journey into one of the most fascinating topics in modern theoretical physics and astrophysics, this comprehensive introduction to black holes physics will take you into the mind of Stephen Hawking and many other scientists, including what they found so intriguing about black holes.

“Reading the Mind of God: Stephen Hawking” from Oracles of Science: Celebrity Scientists versus God and Religion by Karl Giberson and Mariano Artigas

Undeniably, Hawking’s work on black holes and the beginnings of the universe is one of the most important contributions to the scientific canon in the modern era. Yet how has this impacted Christianity’s traditional cosmogony beliefs? The Catholic Church and the Papacy have often found the science of the beginning of the universe problematic. This delicate boundary is this chapter’s primary focus. While it’s true that science and religion are often conceived as antithetical, they both share, at their heart, the same grand purpose: to understand and comprehend the world around us and humanity’s place in it.

Would you like to know more about Stephen Hawking? Using Hawking’s Who’s Who article entry, discover the details of his life including his education, career, and publications.

Image Credit: “A Monster Galaxy in Perseus Cluster.” Photo by NASA’s Marshall Space Flight. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Stephen Hawking, The Theory of Everything, and cosmology appeared first on OUPblog.

Is consumer credit growth worth worrying about?

A news release on 6 February 2015 from the Federal Reserve Board, together with a selection of dense numerical tables, showed once again that consumer credit in use has increased over the course of a year. This is the fourth year in a row and the 67th yearly increase in the 69 years since 1945. But does this mean that credit growth is a meaningful worry? Total consumer sector income and total assets have also increased in 67 of the 69 years since World War II.

By itself, the economic phenomenon of continuous credit growth doesn’t mean the trend is either benign or toxic. And, whether rising or falling, it certainly doesn’t deny that some consumers have debt troubles. But it does suggest that evaluating the importance of the long-term trend in credit use might not be a simple one. Credit growth is a statistical fact, but its implications are more subtle.

Significantly, high-powered econometric measurement approaches haven’t produced evidence from past experience that credit growth has led to the biggest expressed concern, that it leads to decrease in future spending and causes or accentuates macroeconomic recessions. If anything, available evidence is to the contrary. It seems that the larger amounts of credit go on the books when consumers are in good shape financially and generally optimistic about the future. These aren’t the conditions that lead quickly to recessions.

Leaving aside sophisticated econometrics, even simple review of the data suggests a more benign conclusion than the simple one that continuous growth somehow proves that credit has just grown too much for too long. For instance, a look at the Federal Reserve’s statistic measuring the ratio of consumer credit debt payments to income known as the “Debt Service Ratio” (the DSR) shows that even with the inclusion of growing student loan debt after 2003, the DSR is trendless since first calculated in 1980. Other burden measures with longer histories are similarly trendless since the 1960s.

Nonetheless, such measures don’t reveal the distribution of debt. For example, are lower income consumers deeper than ever in debt? If so, this may argue to some people for making consumer credit more difficult to obtain, even if this disadvantages the rest of society. But statistical evidence is contrary here too. Ongoing surveys of consumers as reported in the Federal Reserve’s periodic Surveys of Consumer Finances show that growth in the credit using proportion of low income consumers has been slight since 1963 and only moderate since then in higher income groups. The shares of consumer credit owed by the various income quintiles show great stability since the 1950s.

In sum, consumer credit use has grown in the post-World War II era, but not very much relative to income or assets since the early 1960s. Historical patterns in these ratios have been intensely cyclical, though, which may help explain why there are expressions of concern when they are in a rising cyclical phase. Debt growth has occurred in all income and age groups, but the bulk of consumer credit outstanding currently is owed by the higher income population segments, much as in the past. As with many other simple conclusions from observable phenomena, there is more to the credit growth question than revealed in a single glance at the yearly totals.

Featured image credit: Three credit cards by Petr Kratochvil [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Is consumer credit growth worth worrying about? appeared first on OUPblog.

February 17, 2015

That’s relativity

A couple of days after seeing Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar, I bumped into Sir Roger Penrose. If you haven’t seen the movie and don’t want spoilers, I’m sorry but you’d better stop reading now.

Still with me? Excellent.

Some of you may know that Sir Roger developed much of modern black hole theory with his collaborator, Stephen Hawking, and at the heart of Interstellar lies a very unusual black hole. Straightaway, I asked Sir Roger if he’d seen the film. What’s unusual about Gargantua, the black hole in Interstellar, is that it’s scientifically accurate, computer-modeled using Einstein’s field equations from General Relativity.

Scientists reckon they spend far too much time applying for funding and far too little thinking about their research as a consequence. And, generally, scientific budgets are dwarfed by those of Hollywood movies. To give you an idea, Alfonso Cuarón actually told me he briefly considered filming Gravity in space, and that was what’s officially classed as an “independent” movie. For big-budget studio blockbuster Interstellar, Kip Thorne, scientific advisor to Nolan and Caltech’s “Feynman Professor of Theoretical Physics”, seized his opportunity, making use of Nolan’s millions to see what a real black hole actually looks like. He wasn’t disappointed and neither was the director who decided to use the real thing in his movie without tweaks.

Black holes are so called because their gravitational fields are so strong that not even light can escape them. Originally, we thought these would be dark areas of the sky, blacker than space itself, meaning future starship captains might fall into them unawares. Nowadays we know the opposite is true – gravitational forces acting on the material spiralling into the black hole heat it to such high temperatures that it shines super-bright, forming a glowing “accretion disk”.

“Sir Roger Penrose.” Photo by Igor Krivokon. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

“Sir Roger Penrose.” Photo by Igor Krivokon. CC by 2.0 via Flickr. The computer program the visual effects team created revealed a curious rainbowed halo surrounding Gargantua’s accretion disk. At first they and Thorne presumed it was a glitch, but careful analysis revealed it was behavior buried in Einstein’s equations all along – the result of gravitational lensing. The movie had discovered a new scientific phenomenon and at least two academic papers will result: one aimed at the computer graphics community and the other for astrophysicists.

I knew Sir Roger would want to see the movie because there’s a long scene where you, the viewer, fly over the accretion disk–not something made up to look good for the IMAX audience (you have to see this in full IMAX) but our very best prediction of what a real black hole should look like. I was blown away.

Some parts of the movie are a little cringeworthy, not least the oft-repeated line, “that’s relativity”. But there’s a reason for the characters spelling this out. As well as accurately modeling the black hole, the plot requires relativistic “time dilation”. Even though every physicist has known how to travel in time for over a century (go very fast or enter a very strong gravitational field) the general public don’t seem to have cottoned on.

Most people don’t understand relativity, but they’re not alone. As a science editor, I’m privileged to meet many of the world’s most brilliant people. Early in my publishing career I was befriended by Subramanian Chandrasekhar, after whom the Chandra space telescope is now named. Penrose and Hawking built on Chandra’s groundbreaking work for which he received the Nobel Prize; his The Mathematical Theory of Black Holes (1954) is still in print and going strong.

When visiting Oxford from Chicago in the 1990s, Chandra and his wife Lalitha would come to my apartment for tea and we’d talk physics and cosmology. In one of my favorite memories he leant across the table and said, “Keith – Einstein never actually understood relativity”. Quite a bold statement and remarkably, one that Chandra’s own brilliance could end up rebutting.

Space is big – mind-bogglingly so once you start to think about it, but we only know how big because of Chandra. When a giant sun ends its life, it goes supernova – an explosion so bright it outshines all the billions of stars in its home galaxy combined. Chandra deduced that certain supernovae (called “type 1a”) will blaze with near identical brightness. Comparing the actual brightness with however bright it appears through our telescopes tells us how far away it is. Measuring distances is one of the hardest things in astronomy, but Chandra gave us an ingenious yardstick for the Universe.

“Stephen Hawking.” Photo by Lwp Kommunikáció. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

“Stephen Hawking.” Photo by Lwp Kommunikáció. CC by 2.0 via Flickr. In 1998, astrophysicists were observing type 1a supernovae that were a very long way away. Everyone’s heard of the Big Bang, the moment of creation of the Universe; even today, more than 13 billion years later, galaxies continue to rush apart from each other. The purpose of this experiment was to determine how much this rate of expansion was slowing down, due to gravity pulling the Universe back together. It turns out that the expansion’s speeding up. The results stunned the scientific world, led to Nobel Prizes, and gave us an anti-gravitational “force” christened “dark energy”. It also proved Einstein right (sort of) and, perhaps for the only time in his life, Chandra wrong.

Why Chandra told me Einstein was wrong was because of something Einstein himself called his “greatest mistake”. When relativity was first conceived, it was before Edwin Hubble (after whom another space telescope is named) had discovered space itself was expanding. Seeing that the stable solution of his equations would inevitably mean the collapse of everything in the Universe into some “big crunch”, Einstein devised the “cosmological constant” to prevent this from happening – an anti-gravitational force to maintain the presumed status quo.

Once Hubble released his findings, Einstein felt he’d made a dreadful error, as did most astrophysicists. However, the discovery of dark energy has changed all that and Einstein’s greatest mistake could yet prove an accidental triumph.

Of course Chandra knew Einstein understood relativity better than almost anyone on the planet, but it frustrates me that many people have such little grasp of this most beautiful and brilliant temple of science. Well done Christopher Nolan for trying to put that right.

Interstellar is an ambitious movie – I’d call it “Nolan’s 2001” – and it educates as well as entertains. While Matthew McConaughey barely ages in the movie, his young daughter lives to a ripe old age, all based on what we know to be true. Some reviewers have criticized the ending – something I thought I wouldn’t spoil for Sir Roger. Can you get useful information back out of a black hole? Hawking has changed his mind, now believing such a thing is possible, whereas Penrose remains convinced it cannot be done.

We don’t have all the answers, but whichever one of these giants of the field is right, Nolan has produced a thought-provoking and visually spectacular film.

Image Credit: “Best-Ever Snapshot of a Black Hole’s Jets.” Photo by NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post That’s relativity appeared first on OUPblog.

Strife over strategy: shaping American foreign policy

Last month on Capitol Hill, a tedious slur on Henry Kissinger (“war criminal”) provoked an irate reaction (“low-life scum”). The clash between Senator McCain and the protesters of Code Pink garnered media coverage and YouTube clicks. The Senate’s hearings on national strategy not so much. This is unfortunate. For world-weary superpowers, opportunities for sustained strategic reflection are rare. The transfer of power in the Senate affords such an occasion, and John McCain has seized it. His committee hearings nonetheless illustrate both the many challenges facing American foreign policy and the limits of strategy as a guide to foreign-policy choice.

Making strategy is intellectual work. The strategist seeks to explain the patterns of world events, hopeful that comprehension will guide policy and permit policymakers to shape global trends. Requiring interpretation, making strategy is akin to writing history, but what the strategist explains is the present and future. Henry Kissinger once put it thus: “I think of myself as a historian… I have tried to understand the forces that are at work in this period.”

During the Cold War, the forces at work were clear — or so it now appears. The world was divided, and the United States stood for freedom and against the Soviet Union. Washington did not push the USSR too hard, for doing so risked war. Instead, policymakers adhered to a strategy of containment, the logic of which presumed that the USSR would crumble upon its inner contradictions. History vindicated this theory, and many now yearn for the coherence that containment presumably imparted to US foreign policy. The Cold War was dangerous, General Brent Scowcroft told the McCain hearings, but at least “we knew what the strategy was.”

Americans should not yearn for such clarity. Containment nostalgia distorts the actual adaptability of US foreign policy in the Cold War. The search for strategic coherence is, moreover, inappropriate to the needs of US foreign policy today, which requires not intellectual cohesion but tolerance for complexity, improvisation, and even contradiction.

Henry Kissinger – World Economic Forum Annual Meeting Davos 2008. Photo by Remy Steinegger, World Economic Forum. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Henry Kissinger – World Economic Forum Annual Meeting Davos 2008. Photo by Remy Steinegger, World Economic Forum. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Consider Henry Kissinger and Zbigniew Brzezinski — two of the sages who addressed McCain’s committee. They rank among America’s clearest strategic thinkers, but neither was in his own time a strategic dogmatist. Henry Kissinger began as an adept practitioner of Cold War geopolitics, but as new challenges mounted, he pirouetted to champion cooperation on issues, like energy, that had little to do with the Cold War. From these efforts, the International Energy Agency and the G-7 were born.

Brzezinski, with President Carter, worked to build a “framework of international cooperation” for a world that the Cold War no longer defined and brought human rights into the foreign-policy mainstream. Only as US-Soviet relations deteriorated in the late 1970s did the Carter administration adopt an invigorated anti-Soviet policy. Pragmatic adaptation to events, not devotion to strategic coherence, enabled policymakers to lead the United States through one of the hardest phases in its superpower career, prefiguring the Cold War’s resolution on American terms.

America today faces complex and discordant challenges. For John McCain, a revanchist Russia, a rising China, a truculent Iran, an implacable Islamism, and a rash of failing states make the world more dangerous than ever. McCain might have included (as Scowcroft did) global climate change, an existential challenge for industrial civilization. It is seductive to presume that a singular strategy could enable the United States to transcend, resolve, and master the myriad challenges it faces.

The hope is forlorn. Containment during the Cold War provided no roadmap for policy. At most, containment enjoined acceptance of the world’s division and optimism in the West’s prospects. Within this loose outlook, policymakers improvised and adapted, pursuing diverse agendas. The most effective, like Kissinger, understood that even superpowers do not determine the course of world events; instead, their leaders must react and respond. Presuming the reverse risks the kind of strategic hubris that embroiled the United States in the quagmire that President Obama has struggled for six years to resolve.

What role then for strategy? Strategic thinking, which weighs costs and benefits and contemplates long-range consequences, is a prerequisite for responsible foreign policy. Yet Americans should beware the notion that world affairs can be comprehended within coherent, meta-historical frameworks: the Cold War, globalization, the clash of civilizations, and so on. To be creative, strategy must acknowledge both the provisionality of its own conclusions and the validity of alternative perspectives on the world. Like history, it must remain a work in continual progress.

Heading image: Ford Kissinger Rockefeller by David Hume Kennerly. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Strife over strategy: shaping American foreign policy appeared first on OUPblog.

Another side of Yoko Ono

The scraps of an archive often speak in ways that standard histories cannot. In 2005, I spent my days at the Paul Sacher Foundation in Basel, a leading archive for twentieth-century concert music, where I transcribed the papers of the German-Jewish émigré composer Stefan Wolpe (1902-1971). The task was alternately exhilarating and grim. Wolpe had made fruitful connections with creators and thinkers across three continents, from Paul Klee to Anton Webern to Hannah Arendt to Charlie Parker. An introspective storyteller and exuberant synthesizer of ideas, Wolpe narrated a history of modernism in migration as a messy, real-time chronicle in his correspondence and diaries. Yet, within this narrative, the composer had also reckoned with more than his share of death and loss as a multiply-displaced Nazi-era refugee. He had preserved letters from friends as symbols of the ties that had sustained him, in some cases carrying them over dozens of precarious border crossings during his 1933 flight. By the 1950s, his circumstances had calmed down, after he had settled in New York following some years in Mandatory Palestine. Amidst his mid-century papers, I was surprised to come across a cache of artfully spaced poems typewritten on thick leaves of paper, with the attribution “Yoko Ono.” The poems included familiar, stark images of death, desolation, and flight. It was only later that I realized they responded not to Wolpe’s life history, but likely to Ono’s own. The poems inspired a years-long path of research that culminated in my article, “Limits of National History: Yoko Ono, Stefan Wolpe, and Dilemmas of Cosmopolitanism,” recently published in The Musical Quarterly.

Yoko Ono befriended Stefan Wolpe and his wife the poet Hilda Morley in New York City around 1957. Although of different backgrounds and generations, Wolpe and Ono were both displaced people in a city of immigrants. Both had been wartime refugees, and both endured forms of national exile, though in different ways. Ono had survived starvation conditions as an internal refugee after the Tokyo firebombings. She was twelve when her family fled the city to the countryside outside Nagano, while her father was stranded in a POW camp. By then, she had already felt a sense of cultural apartness, since she had spent much of her early childhood shuttling back and forth between Japan and California, following her father’s banking career. When she began her own career as an artist in New York in the 1950s, Ono entered what art historian Midori Yoshimoto has called a gender-based exile from Japan. Her career and lifestyle clashed with a society where there were “few alternatives to the traditional women’s role of becoming ryōsai kenbo (good wives and wise mothers).” Though Ono eventually became known primarily as a performance and visual artist, she identified first as a composer and poet. After she moved to the city to pursue a career in the arts, Ono’s family disowned her. It was around this time that she befriended the Wolpe-Morleys, who often hosted her at their Upper West Side apartment, where she “loved the intellectual, warm, and definitely European atmosphere the two of them had created.”

In 2008, I wrote a letter to Ono, asking her about the poems in Wolpe’s collection. Given her busy schedule, I was surprised to receive a reply within a week. She confirmed that she had given the poems to Wolpe and Morley in the 1950s. She also shared other poems and prose from her early adulthood, alongside a written reminiscence of Wolpe and Morley. She later posted this reminiscence on her blog several months before her 2010 exhibit “Das Gift,” an installation in Wolpe’s hometown Berlin dedicated to addressing histories of violence. The themes of the installation trace back to the earliest phase of her career when she knew Wolpe. During their period of friendship, both creators devoted their artistic projects to questions of violent history and traumatic memory, refashioning them as a basis for rehabilitative thought, action, and community.

Guggenheim Museum, 88th St. & 5th Ave., New York City. Under construction II, 12 November 1957. Gottscho-Schleisner, Inc., photographer. Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Guggenheim Museum, 88th St. & 5th Ave., New York City. Under construction II, 12 November 1957. Gottscho-Schleisner, Inc., photographer. Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Virtually no historical literature acknowledges Ono’s and Wolpe’s connection, which was premised on shared experiences of displacement, exile, and state violence. Their affiliation remains virtually unintelligible to standard art and music histories of modernism and the avant-garde, which tend to segregate their narratives along stable lines of genre, medium, and nation—by categories like “French symbolist poetry,” “Austro-German Second Viennese School composition,” and “American experimental jazz.” From this narrow perspective, Wolpe the German-Jewish, high modernist composer would have little to do with Ono the expatriate Japanese performance artist.

What do we lose by ignoring such creative bonds forged in diaspora? Wolpe and Ono both knew what it was to be treated as less than human. They had both felt the hammer of military state violence. They both knew what it was to not “fit” in the nation—to be neither fully American, Japanese, nor German. And they both directed their artistic work toward the dilemmas arising from these difficult experiences. The record levels of forced displacement during their lifetimes have not ended, but have only risen in our own. According to the most recent report from the UN High Commissioner on Refugees, “more people were forced to flee their homes in 2013 than ever before in modern history.” Though the arts cannot provide refuge, they can do healing work by virtue of the communities they sustain, with the call-and-response of human recognition exemplified in boundary-crossing friendships like Wolpe’s and Ono’s. And to recognize such histories of connection is to recognize figures of history as fully human.

Headline image credit: Cards and poems made for Yoko Ono’s Wish Tree and sent to Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden (Washington), 7 November 2010. Photo by Gianpiero Actis & Lidia Chiarelli. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Another side of Yoko Ono appeared first on OUPblog.

The Grand Budapest Hotel and the mental capacity to make a will

Picture this. A legendary hotel concierge and serial womaniser seduces a rich, elderly widow who regularly stays in the hotel where he works. Just before her death, she has a new will prepared and leaves her vast fortune to him rather than her family.

For a regular member of the public, these events could send alarm bells ringing. “She can’t have known what she was doing!” or “What a low life for preying on the old and vulnerable!” These are some of the more printable common reactions. However, for cinema audiences watching last year’s box office smash, The Grand Budapest Hotel directed by Wes Anderson, they may have laughed, even cheered, when it was Tilda Swinton (as Madame Céline Villeneuve Desgoffe und Taxis) leaving her estate to Ralph Fiennes (as Monsieur Gustave H) rather than her miffed relatives. Thus the rich, old lady disinherits her bizarre clan in what recently became 2015’s most BAFTA-awarded film, and is still up for nine Academy Awards in next week’s Oscars ceremony.

Wills have always provided the public with endless fascination, and are often the subject of great books and dramas. From Bleak House and The Quincunx to Melvin and Howard and The Grand Budapest Hotel, wills are often seen as fantastic plot devices that create difficulties for the protagonists. For a large part of the twentieth century, wills and the lives of dissolute heirs have been regular topics for Sunday journalism. The controversy around the estate of American actress and model, Anna Nicole Smith, is one such case that has since been turned into an opera, and there is little sign that interest in wills and testaments will diminish in the entertainment world in the coming years.

“[The Vegetarian Society v Scott] is probably the only case around testamentary capacity where the testator’s liking for a cooked breakfast has been offered as evidence against the validity of his will.”

Aside from the drama depicted around wills in films, books, and stage shows, there is also the drama of wills in real life. There are two sides to every story with disputed wills and the bitter, protracted, and expensive arguments that are generated often tear families apart. While in The Grand Budapest Hotel the family attempted to solve the battle by setting out to kill Gustave H, this is not an option families usually turn to (although undoubtedly many families have thought about it!).

Usually, the disappointed family members will claim that either the ‘seducer’ forced the relative into making the will, or the elderly relative lacked the mental capacity to make a will; this is known as ‘testamentary capacity’. Both these issues are highly technical legal areas, which are resolved dispassionately by judges trying to escape the vehemence and passion of the protagonists. Regrettably, these arguments are becoming far more common as the population ages and the incidence of dementia increases.

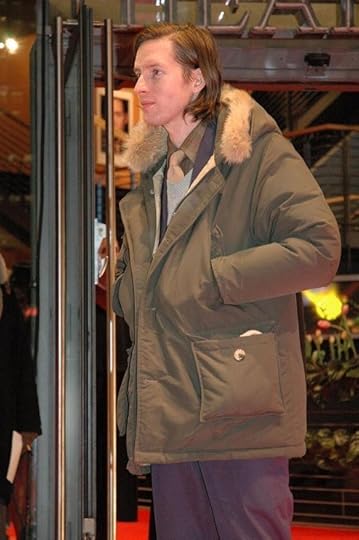

Wes Anderson, director of The Grand Budapest Hotel. By Popperipopp. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Wes Anderson, director of The Grand Budapest Hotel. By Popperipopp. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.The diagnosis of mental illness is now far more advanced and nuanced than it was when courts were grappling with such issues in the nineteenth century. While the leading authority on testamentary capacity still dates from a three-part test laid out in the 1870 Banks v Goodfellow case, it is still a common law decision, and modern judges can (and do) adapt it to meet advancing medical views.

This can be seen in one particular case, The Vegetarian Society v Scott, in which modern diagnosis provided assistance when a question arose in relation to a chronic schizophrenic with logical thought disorder. He left his estate to The Vegetarian Society as opposed to his sister or nephews, for whom he had a known dislike. There was evidence provided by the solicitor who wrote the will that the deceased was capable of logical thought for some goal-directed activities, since the latter was able to instruct the former on his wishes. It was curious however that the individual should have left his estate to The Vegetarian Society, as he was in fact a meat eater. However unusual his choice of heir, the deceased’s carnivorous tendencies were not viewed as relevant to the issues raised in the court case.

As the judge put it, “The sanity or otherwise of the bequest turns not on [the testator’s] for food such as sausages, a full English breakfast or a traditional roast turkey at Christmas; nor does it turn on the fact that he was schizophrenic with severe thought disorder. It really turns on the rationality or otherwise of his instructions for his wills set in the context of his family relations and other relations at various times.”

This is probably the only case around testamentary capacity where the testator’s liking for a cooked breakfast has been offered as evidence against the validity of his will.

For lawyers, The Grand Budapest Hotel’s Madame Céline Villeneuve Desgoffe und Taxis is potentially a great client. Wealth, prestige, and large fees for the will are then followed by even bigger fees in the litigation. If we are to follow the advice of the judge overseeing The Vegetarian Society v Scott, Gustave H would have inherited all of Madame Céline’s money if she was seen to be wholly rational when making her will.

Will disputes will always remain unappealing and traumatic to the family members involved. However, as The Grand Budapest Hotel has shown us, they still hold a strong appeal for cinema audiences and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future.

Feature image: Reflexiones by Serge Saint. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post The Grand Budapest Hotel and the mental capacity to make a will appeared first on OUPblog.

February 16, 2015

How disease names can stigmatize

On 10 February 2015, the long awaited report from the Institute of Medicine (IOM) was released regarding a new name — Systemic Exertion Intolerance Disease — and case definition for chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). Because I was quoted regarding this report in a , in part due to having worked on these issues for many years, hundreds of patients contacted me over the next few days.

The reaction from patients was mixed at best, and some of the critical comments include:

“This new name is an abomination!”

“Absolutely outrageous and intolerable!”

“I find it highly offensive and misleading.”

“It is pathetic, degrading and demeaning.”

“It is the equivalent of calling Parkinson’s Disease: Systemic Shaking Intolerance Disease.”

“(It) is a clear invitation to the prejudiced and ignorant to assume ‘wimps’ and ‘lazy bums.’”

“The word ‘exertion,’ to most people, means something substantial, like lifting something very heavy or running a marathon – not something trivial, like lifting a fork to your mouth or making your way across the hall to the bathroom. Since avoiding substantial exertion is not very difficult, the likelihood that people who are not already knowledgeable will underestimate the challenges of having this disease based on this name seems to me extremely high.”

Several individuals were even more critical in their reactions — suggesting that the Institute of Medicine-initiated name change effort represented another imperialistic US adventure, which began in 1988 when the Centers for Disease Control changed the illness name from myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) to chronic fatigue syndrome. Patients and advocacy groups from around the world perceived this latest effort to rename their illness as alienating, expansionistic, and exploitive. The IOM alleged that the term ME is not medically accurate, but the names of many other diseases have not required scientific accuracy (e.g., malaria means bad air). Regardless of how one feels about the term ME, many patients firmly support it. Our research group has found that a more medically-sounding term like ME is more likely to influence medical interns to attribute a physiological cause to the illness. In response to a past blog post that I wrote on the name change topic, Justin Reilly provided an insightful historical comment: for 25 years patients have experienced “malfeasance and nonfeasance” (also well described in Hillary Johnson’s Osler’s Web). This is key to understanding the patients’ outrage and anger to the IOM.

So how could this have happened? The Institute of Medicine is one of our nation’s most prestigious organizations, and the IOM panel members included some of the premier researchers and clinicians in the myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome arenas, many of whom are my friends and colleagues. Their review of the literature was overall comprehensive; their conclusions were well justified regarding the seriousness of the illness, identification of fundamental symptoms, and recommendations for the need for more funding. But these important contributions might be tarnished by patient reactions to the name change. The IOM solicited opinions from many patients as well as scientists, and I was invited to address the IOM in the spring regarding case definition issues. However, their process in making critical decisions was secretive, and whereas for most IOM initiatives this is understandable in order to be fair and unbiased in deliberations, in this area — due to patients being historically excluded and disempowered — there was a need for a more transparent, interactive, and open process.

So what might be done at this time? Support structural capacities to accomplish transformative change. Set up participatory mechanisms for ongoing data collection and interactive feedback, ones that are vetted by broad-based gatekeepers representing scientists, patients, and government groups. Either the Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Advisory Committee (that makes recommendations to the Secretary of US Department of Health and Human Services) or the International Association of ME/CFS (the scientific organization) may appoint a name change working group with international membership to engage in a process of polling patients and scientists, sharing the names and results with large constituencies, and getting buy in — with a process that is collaborative, open, interactive, and inclusive. Different names might very well apply to different groups of patients, and there is empirical evidence for this type of differentiation. Key gatekeepers including the patients, scientists, clinicians, and government officials could work collaboratively and in a transparent way to build a consensus for change, and most critically, so that all parties are involved in the decision-making process.

Headline image credit: Hospital. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers