Oxford University Press's Blog, page 695

February 25, 2015

The important role of palatable food in eating disorders

When we hear the term “eating disorder,” we often think of the woman at our gym who looks unhealthily thin or maybe a friend who meticulously monitors each calorie he or she consumes. Though anorexia nervosa (marked by low weight and a strong fear of weight gain) is a serious and harmful mental illness with one of the highest mortality rates of any psychiatric illness, the reality is that the most common eating disorders are bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder, both of which involve—and in fact, require for their diagnoses—binge eating. Binge eating is defined as frequent episodes of eating more than most people would consider normal during a discrete period of time. Thus, although our stock mental image of an eating disorder is usually characterized by severe undereating, many individuals with eating disorders actually struggle with patterns of overeating. In fact, most people don’t know that there is a subtype of patients with anorexia nervosa who also struggle with binge eating.

What types of food do people tend to binge on? According to a research study, both obese women with binge eating disorder and those without binge eating disorder consumed more snack and dessert foods (e.g., ice cream, cake, and potato chips) during a “binge” meal when they were instructed to “let yourself go and eat as much as you can,” indicating that these are the types of food items that people tend to overindulge in when given the opportunity. Another study analyzing the food content of binge episodes among women with bulimia nervosa also found that binge meals include more snack and dessert items.

For the past decade or so, my laboratory has been interested in studying how consumption of highly palatable—or tasty—ingredients, especially sugar and fat, affects the brain reward system, with a particular focus on their effects on dopamine. In a series of studies using laboratory animal models, we have looked at this question from many different angles. For instance, we have investigated how sugar consumption affects dopamine release when rats are underweight as well as how eating a cafeteria diet—composed of many different food items including cheese, marshmallows, and chocolate chip cookies to model the variety available in our current food environment—affects dopamine release in obese rats. The overall take-away from these studies is that palatable food consumption leads to heightened dopamine release, which may help to explain why we tend to indulge in or overeat these foods in particular and continue to eat them despite knowing the harm they can have on our bodies.

While my laboratory’s work has primarily focused on the neural response to palatable food, our eating habits are shaped by a myriad of powerful factors, including taste, cost, cultural traditions, social and other visual cues, convenience, as well as smell (recall the last time you passed a Cinnabon shop in the mall!). Unfortunately, many of these factors collide to make palatable food options appealing on several levels: these foods tend to be tasty, low cost, conveniently packaged for eating on the go, marketed heavily, involved in many of our social and cultural celebrations, and can smell delicious. This helps to explain why overconsuming palatable food is not only a problem for those struggling with certain eating disorders but for society on a larger level and may contribute to the staggering rates of overweight and obesity in the US today.

Special thanks to Ms. Susan Murray for her assistance with drafting this blog post.

Image Credit: “Cake Pops” by White77. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The important role of palatable food in eating disorders appeared first on OUPblog.

Inequality in democracies: interest groups and redistribution

We are by now more or less aware that income inequality in the US and in most of the rich OECD world is higher today than it was some 30 to 40 years ago. Despite varying interpretations of what led to this increase, the fact remains that inequality is exhibiting a persistent increase, which is robust to both expansionary and contractionary economic times. One might even say that it became a stylized fact of the developed world (amid some worthy exceptions). The question on everyone’s lips is how can a democracy result in rising inequality?

In one of the seminal papers in political economy, Meltzer and Richard (1981) proposed a theoretical model in which more democracy implies more redistribution and hence lower inequality. The idea is that the median voter is usually to the left of the mean income voter in a typical income distribution curve, which is always slightly tilted to the right – meaning there are more poor people than rich people in a society. The larger the gap between the mean income voter and the median population voter (i.e. the poorer the median voter) the more redistribution will be demanded (under the classical Downsian assumptions of electoral competition). This also implies that more unequal countries should have larger governments. We of course know this is not true, primarily since most unequal societies are not democracies, meaning that their ruling elites don’t really care of the position of the median voter. But it is true that more democratic societies do on average have lower inequality.

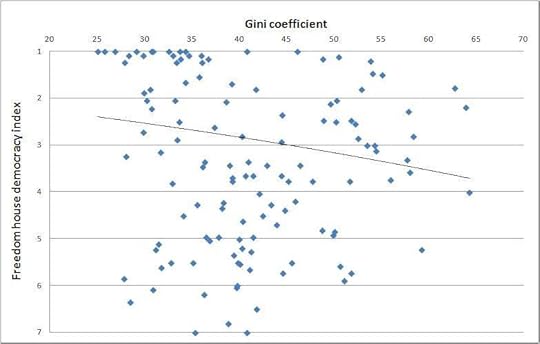

Note: The Freedom house democracy ranking is from 1 (the most democratic) to 7 (the least democratic). Higher Gini implies higher inequality. This graph deploys averages of the democracy index and the Gini in the past 20 years. Source of data: Gini: World Bank. Democracy: Freedom House. Graph used with permission of Vuk Vukovic.

Note: The Freedom house democracy ranking is from 1 (the most democratic) to 7 (the least democratic). Higher Gini implies higher inequality. This graph deploys averages of the democracy index and the Gini in the past 20 years. Source of data: Gini: World Bank. Democracy: Freedom House. Graph used with permission of Vuk Vukovic. Note however that this is mere correlation, not even a strong one, and it doesn’t tell us a lot about why inequality in the West is still rising. It does not explain the dynamics of inequality.

And while it’s relatively easy to explain the persistence of inequality in institutionally weak societies, the question remains as to why the median voter in the West is still disenfranchised? Shouldn’t the persistence and consolidation of a democracy imply a gradual decline of inequality over the past generation?

The rapid rise of interest group power can help us provide a partial answer. As interest groups in democracies become better organised, they become more successful at increasing the size of government but bias that increase towards themselves. This leaves relatively less money for redistribution and programs aimed at the poorer ends of the society, particularly in terms of education and health care. The theory of collective action explains this phenomenon where small (privileged) groups possess enough information, have low enough organization costs, and are far more homogeneous in distributing the potential benefits to successfully solve the public good allocation problem. As the number of interest groups fighting for state redistribution increases, this becomes a wider burden for society, whose productive resources are being sub optimally allocated. We can call this phenomenon “interest group state capture” which unfortunately characterizes more and more democratic societies today – both rich and poor.

If we label the emergence of interest groups as the “macro” cause for rising inequality, then the structural factors such as technology and education, arguably even more important, can be called the “micro” causes. It is indicative that the inequality gap started increasing since the 80s, just around the same time the third industrial revolution started changing the patterns of job market specialization.

“Inequality is exhibiting a persistent increase.”

The culprit for higher inequality, in my opinion, can be found in the interaction of several factors (in addition to the aforementioned interest group capture). Rapid technological progress in the past 30 years resulted in a typical creative destruction process where new jobs and careers made certain types of old jobs obsolete (automated work). Some of these obsolete jobs were outsourced to Asia, while low-skilled workers back home found themselves to be the technological surplus. In addition, a lot of low-skilled labour entered the market (mostly via higher immigration) who failed to adapt to the changes and were left stranded either at lower paid jobs or became long-term unemployed. Poor education played an important role as well, while stagnating wages in the “dying” sectors only widened the gap. On the other hand, the innovative part of the equation was working quite well, taking advantage of the new technological wave, thus raising the income of the top 10% (hence the great disparity in income between workers who hold a college degree and those who do not). It’s not hard to imagine how these two pulling forces (one downwards, one upwards) managed to widen the inequality gap in many of the OECD countries.

However none of these issues affected the real US problem: stagnating social mobility. The underlying causes behind this structural phenomenon can indeed be blamed on interest group capture of democracies. The solution to this problem is thus, primarily political.

Featured image credit: Spirit Level, by aTarom. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Inequality in democracies: interest groups and redistribution appeared first on OUPblog.

February 24, 2015

Questions about India’s environment and economic growth

Must economic growth be privileged over ecological security? Jairam Ramesh argues that this is the wrong question to ask; the two work in concert, not in opposition, and a bright economic and political future requires a safe, protected environment. As India grows as a global power, the nation has become a leader in progressive environmental policies. A Former Minister of State (Independent Charge) of Environment and Forests for the Government of India, Ramesh understands the political debates, struggles, challenges, and obstacles in bringing the environment into decision-making, in particular the ‘1991 moment’. In the following Storify of a Twitter chat yesterday, Jairam Ramesh, author of Green Signals: Ecology, Growth, and Democracy in India, answers questions from the public on India’s environment and economic growth.

[View the story “#GreenIndia Chat with Jairam Ramesh” on Storify]What are your thoughts? Add them in the comments section below, or join the conversation on Twitter with the #GreenIndia hashtag.

Headline image credit: Delhi/New Delhi/Gurgaon, India at Night (NASA, International Space Station, 12/08/12). CC BY-NC 2.0 via NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center Flickr.

The post Questions about India’s environment and economic growth appeared first on OUPblog.

Surrogacy: how the law develops in response to social change

Yesterday, Claire Legras, a distinguished member of the Conseil d’Etat in France and rapporteur for the National Consultative Ethics Committee for Health and Life Sciences, contributed her perspective on the ethical considerations of surrogacy. Her piece, which posits national court case as global problem, underscores the value of discussions between judges in other jurisdictions facing similar problems. Today, Lady Justice Arden explores the international dimensions of surrogacy law, including differences in approach between French and English law.

In its recent decision in Mennesson v. France (App no. 65192/11), the Fifth Section of the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg ruled that surrogate children—in this case, born in the US and having US citizenship—should not be prevented from registering as French citizens, as this would be a violation of their right to respect for their private life. The Strasbourg court’s view, which is very understandable, is that nationality is an important part of a person’s identity.

The Strasbourg court’s view, which is very understandable, is that nationality is an important part of a person’s identity.

France has not asked for this decision to be referred to—and thus reconsidered by—the Grand Chamber of the Strasbourg court. So it will be interesting to see whether, or to what extent, the French legislature or the French courts take account of this decision.

In Mennesson, the child was the biological child of one of the commissioning parents. In the more recent case of Paradiso and Campanelli v. Italy (App. no. 25358/12), the child was not the biological child of either of the commissioning parents; born abroad, the baby was removed from their custody on return to Italy. Strasbourg also found a violation of the child’s right to a private life in that case.

“Playing with Light” by Hugrakka. CC by ND 2.0 via Flickr.

“Playing with Light” by Hugrakka. CC by ND 2.0 via Flickr. Other Convention states are also considering whether to revise their law in order to focus on the best interests of the child. Finland, for instance, is considering modifications to the ban on domestic commercial surrogacy. The Federal Supreme Court of Germany has held that an order of a Californian court, which declares the commissioning parents to be the parents of the surrogate child, should be recognised in Germany (BGH, 10 December 2014, XII ZB 463/13).

These cases demonstrate how courts across Europe are increasingly having to deal with surrogacy issues, and how those issues have now taken on an international dimension. Society is undergoing great change in its acceptance of reproductive autonomy and liberty.

It would be impossible to summarise English law on surrogacy in a few sentences. Here are some key points.

1. Agencies: Surrogacy agreements are unenforceable and agencies that make surrogacy arrangements on a commercial basis are prohibited in England, according to sections 1A and 2 of the Surrogacy Arrangements Act of 1985. That drives commissioning parents abroad.

These cases demonstrate how courts across Europe are increasingly having to deal with surrogacy issues, and how those issues have now taken on an international dimension. Society is undergoing great change in its acceptance of reproductive autonomy and liberty.

2. Parental orders: When the commissioning parents return with a newly-born child that is biologically theirs, they should apply to the English court for a parental order under section 54 of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008 within 6 months. The English court will decide whether it is in the best interests of the child to give parental responsibility to the commissioning parents. The recent Strasbourg case law may, therefore, not cause any immediate difficulty. The 2008 Act provides that at least one of the commissioning parents must be domiciled in the UK at the time of the application for the parental order. The court has held that it must take account of the commissioning parents’ good faith; it must consider whether any offence has been committed, and it is an offence to bring a child into the jurisdiction following a foreign adoption order. The court has also held that the commissioning parents do not commit this offence where the adoption order was made to meet the requirements of the court dealing with the surrogacy arrangements.

3. Birth mother’s consent: The consent of the birth mother must be proved and is ineffective if given less than 6 weeks after the birth.

4. Surrogacy payments: Before making a parental order, the court will also need to consider and authorise any payments which have been made for the surrogacy arrangements ,and which exceed the payment of the birth mother of her reasonable expenses.

5. Liberal interpretation: The courts have applied a liberal interpretation to the statutory requirements: they have to decide whether to make a parental order in the light of the fact that the child has been born and is a fait accompli. The President of the Family Division has, for instance, held that Parliament must have intended that an application for a parental order could be made outside the 6-month period (re X (A Child) (Surrogacy: Time Limit) [2014] EWHC 3135).

6. Role of the courts: The role of the English court requires a high level of judicial skill, but there is a detailed statutory scheme and the role of the judge is therefore very specific.

English law is pragmatic: it proceeds on the basis that there is no turning back and that the legislative framework is not a perfect solution to the issues of surrogacy.

The English courts’ role is far removed from that of the Cour de Cassation in France in deciding whether to apply ethical public policy considerations in the field of nationality, as it did in Mennesson.

7. English law is pragmatic: it proceeds on the basis that there is no turning back and that the legislative framework is not a perfect solution to the issues of surrogacy. English law is not driven by any single public policy aim but by several aims: the policy of not permitting commodification of the human body through commercial arrangements (while not preventing purely altruistic arrangements), protecting the child’s best interests, and safeguarding the interests of the birth mother. The courts and Parliament seek to balance these considerations, and it is, on occasion, difficult to do this.

Claire Legras’ contribution brought me to realise how valuable it was to discuss legal problems with judges and practitioners in other jurisdictions. The value of the international perspective was one of the themes in my recent book, Human Rights and European Law (OUP, 2015), volume 1 of a 2-part series Shaping Tomorrow’s Law. Our appreciation of the problems facing us and the quality of our own law is enriched as a result.

There is another point. The reaction in France to Mennesson shows that the UK is not the only Convention state to experience, from time to time, difficulties and challenges to our deeply held beliefs as a result of advances in human rights. Whatever the strengths and weaknesses of the Convention system, the Strasbourg court is the place where there is an attempt at mediating the diverse views in Europe on ethical issues. The Strasbourg court cannot solve the problems of surrogacy from every angle, but it can survey the legal scene in the Convention states (as it did in Mennesson), and address key issues in this field.

This is a consequence of the Strasbourg court’s conception of the Convention as “a living instrument.” Its dynamic approach enables the law to develop in line with social changes. Our own common law contains similar mechanisms, and how it addresses social change is one of the themes in volume 2, Common Law and Modern Society: Keeping Pace with Change, which will be published later this year.

Image Credit: “Ada’s feet” by Christian Haugen. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Surrogacy: how the law develops in response to social change appeared first on OUPblog.

Andrew Johnson: a little man in a big job

If it were not for his impeachment on 24 February 1868, and the subsequent trial in the Senate that led to his acquittal, Andrew Johnson would probably reside among the faded nineteenth century presidents that only historical specialists now remember. Succeeding to the White House after the murder of Abraham Lincoln in April 1865, Johnson proved to be a presidential failure whose opposition to Republican plans for reshaping the South after the Civil War rested on a noxious brew of state rights ideology and outright racism. Put on the ticket of the Union Party in 1864 with Lincoln as a loyal war Democrat, Johnson had nothing in common with the triumphant Republicans who sought to implement their victory in the Civil War. When he faced the defeated southern states in 1865, he hurried through a plan of presidential Reconstruction that would have allowed the former Rebels a quick return to power and a resumption of their part in American politics. If they failed to repudiate secession and imposed Black Codes on the newly liberated slaves, Johnson saw nothing wrong with those outcomes since he believed in the inherent inferiority of African Americans. “This is a country for white men,” Johnson declared, “and by God as long as I am President, it shall be a government for white men.”

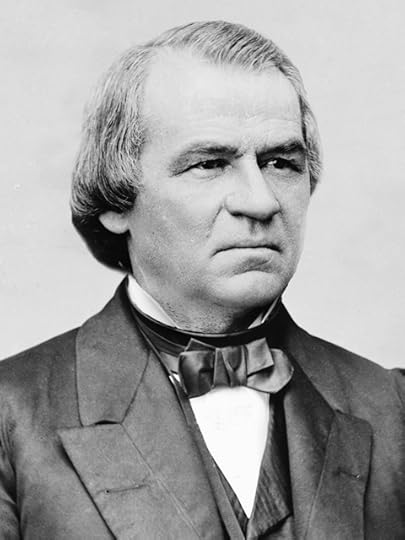

President Andrew Johnson. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

President Andrew Johnson. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Johnson’s policies did not sit well with Republicans in Congress in 1865-1866, who expected contrite submission from the South, protection for the former slaves, and a chance for their party to gain a foothold in the South. The Congressional Republicans rallied around a Civil Rights bill in 1866 which Johnson vetoed. To make the gains of the Civil War permanent, the Republicans coalesced behind the Fourteenth Amendment, making everyone born or naturalized in the United States a citizen entitled to due process of law. The Fourteenth Amendment emerged as the de facto peace terms of the late war. President Johnson attacked the amendment and urged the southern states to oppose ratification. He made it an issue in the 1866 Congressional elections and suffered a humiliating defeat. Nothing daunted, Johnson opposed the Republicans as they sought to implement Reconstruction after 1867. Frustrated at Johnson’s efforts to forestall what they wanted to do, Republicans, led by those who styled themselves “Radical Republicans,” decided that the only way to eliminate Johnson was to remove him through impeachment, a device never before used against a sitting chief executive.

While the Republicans had ample anger against Johnson, demonstrating that he had committed “high crimes and misdemeanors,” as the Constitution specified, proved less easy to establish. The eleven articles of impeachment passed by the House on 24 February 1868 said that he had committed such offenses. The basic case against Johnson was political — not criminal — with ambiguous evidence. After all, his term would end in nine months whether he was convicted or not. In the end, Johnson was acquitted. The Republicans who voted to find him not guilty, while not profiles in courage, did not think it was worth disturbing the constitutional system to remove him.

For a long time that was also the historical verdict on the Johnson impeachment. It was seen as an example of Congressional overreach. With the rise of the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s, scholars took another look at Johnson, condemned his racism, and rehabilitated his critics.

The Watergate controversy also sparked another look at Johnson’s case as participants in that episode sought to learn from the earlier example. While understanding better the motives of the impeachers in 1868, lawyers and historians did not come to see the Johnson impeachment as wise or unnecessary. That assessment survived the unsuccessful effort to convict President Bill Clinton in 1998-1999. So Johnson lingers on, a presidential failure who made the least of his historical moment. Specialists may remember 24 February as a key point in the life of a politician raised by chance above his talents. For other Americans, Andrew Johnson probably deserves his obscurity. He avoided removal by a narrow margin in the Senate, served out his term, won election to the Senate in 1875, and died before he could make any other mark on American history. A little man in a big job, Andrew Johnson falls in the bottom ranks of presidents where he belongs.

Featured image: “The Senate as a Court of Impeachment for the Trial of Andrew Johnson.” Illustration in Harper’s Weekly. 11 April 1868. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Andrew Johnson: a little man in a big job appeared first on OUPblog.

Mississippi hurting: lynching, murder, and the judge

Last week marked two important events in the unfinished story of southern racial violence. On 10 February, the Alabama-based Equal Justice Initiative released Lynching in America, an unflinching report that documents 3,959 black victims of mob violence in twelve southern states between 1877 and 1950. The same day, a US District Court judge handed down sentences in the federal government’s first prosecution in Mississippi under the Shephard-Byrd Hate Crimes Prevention Act. If not for the sentencing remarks that Judge Carlton Reeves delivered to three participants in the June 2011 killing of James Craig Anderson, perhaps no one would be talking about these events in the same breath. They should.

On a summer night three and a half years ago, a group of young whites from Brandon, Mississippi drove into nearby Jackson to “fuck with some niggers.” They attacked James Craig Anderson, a 48-year-old black autoworker, in a motel parking lot. A security camera captured the assault. As the beaten and bloodied victim staggered away, eighteen-year-old Daryl Dedmon revved his Ford pickup, hopped the curb, and crushed Anderson under the wheels as he sped off. Dedmon, already serving a life sentence for capital murder, sat alongside two accomplices as Judge Reeves declared that the three men — and seven others yet to be sentenced — “ ripped off the scab of the healing scars of Mississippi … causing her (our Mississippi) to bleed again.”

Lynch mobs, the judge continued, had stained Mississippi’s soil with the blood of hundreds of black victims. The EJI report, which the judge referenced briefly in his remarks, tallies 576 dead between 1877 and 1950. That count stops short of a rash of racial killings in the Magnolia State that prompted the NAACP to release its 1955 pamphlet, M Is For Mississippi and Murder. It does not include civil rights workers Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney, who were killed the same year — 1964 — that Reeves was born. But the judge invoked the three by name, along with other well-known martyrs and just a sampling of the hundreds of lesser-known black Mississippians who died at the hands of the mob.

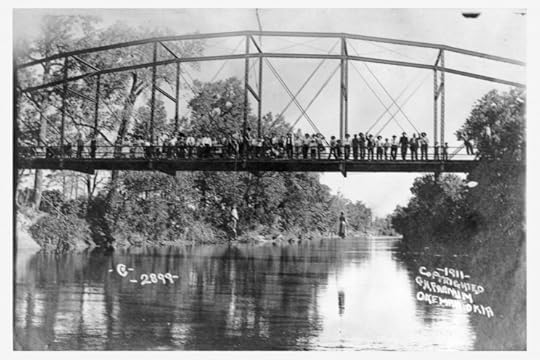

The lynching of Laura and Lawrence Nelson on 25 May 1911 in Okemah, Oklahoma. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The lynching of Laura and Lawrence Nelson on 25 May 1911 in Okemah, Oklahoma. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Judge Reeves needed look no further than Rankin County, home to Anderson’s assailants, for “lesser-known” names. He could have mentioned Stanley Hayes, a black farmhand gunned down by a Brandon mob in 1899, or any of the eight other Rankin County victims tallied by the EJI’s new report. Since June 2011, media outlets have pondered why Brandon, relatively prosperous and disproportionately white by Mississippi standards, became an incubator for a latter-day lynch mob. Defensive locals have fired back that “there is nothing wrong with Brandon,” and increasingly tight-lipped town officials dismiss the attack as an “isolated” incident. Indeed, in Mississippi’s long and bloody history, Brandon is decidedly normal — just another “lynch town” that would rather do anything than faces its past and its echoes in the present.

By placing Anderson’s killing in a longer history of racial terror, Judge Reeves tore through the barrier between past and present. It is a wall that the powerful and privileged in Mississippi worked long and hard to build. Just a generation ago, in a US District Court, the state of Mississippi squandered thousands of taxpayer dollars in a futile attempt to keep a history textbook out of public school classrooms because it contained, among other things, a photograph of a lynching. Last week, the second African American ever appointed to the state’s federal courts quoted from his former professor’s recently published history of Mississippi — which includes dozens of references to mob violence. Part of building the “New Mississippi,” a Judge Reeves demonstrates, is honoring a new history.

Stories of racial violence tap a deep well. Discussion of these atrocities, past and present, often provokes reflexive rationalization, borne of an impulse, as the battle-flag waving governor Ross Barnett once put it, to “Stand Up for Mississippi.” Attempts to confront the state’s record of racial violence dredge up fears and resentments that many would prefer to keep below the surface. In last week’s remarks, which are receiving well-deserved praise, Judge Reeves seized an opportunity to remind his home state that it has a choice and a challenge. The notion of a “New” Mississippi demands the realization that there was indeed an “Old,” and that we are suspended somewhere between the two. The 2011 killing of James Craig Anderson revealed how much we all remain trapped in a history that we often feel more than we know. But last week’s sentences — and those that are sure to follow — offer a chance not just to close a chapter but also to open a conversation. Judge Reeves’s “New Mississippi” is not a place where the past no longer speaks, but a place where all heed its lessons.

This article was first published in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

The post Mississippi hurting: lynching, murder, and the judge appeared first on OUPblog.

The art of musical arrangements

‘I write arrangements, I’m sort of a wannabe composer’ – consciously or otherwise, these words from violinist Joshua Bell seem to give voice to the tension between these two interlocking musical activities. For arrangement and composition are interlocked, as composers throughout the ages have arranged, adapted, revised, and generally played free with musical compositions of all kinds (their own and other people’s) for reasons artistic, practical, or downright commercial.

If an arrangement is – in the definition of New Grove – ‘the reworking of a musical composition, usually for a different medium from that of the original’, then examples abound from earliest times. In the Renaissance, a cappella vocal ensemble pieces were reworked as music for solo keyboard or lute in a practice called ‘intabulation’ (so-called as the music was written in tablature). With simple elaborations of the vocal lines to suit the instrument, it was a technique echoed in some of the pieces from the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book (late 16th/early 17th century), where contemporary songs and airs were filled out and decorated in transcriptions for keyboard. From the same period, English madrigals were published as ‘apt for voices or viols’ – certainly indicating they could be performed in different ways, perhaps also revealing a publisher’s desire to exploit two markets.

This practice of borrowing and adapting took off apace in the Baroque period, with composers plundering their own pieces and the works of others for musical material. Handel was an inveterate borrower of his own material. For example the Presto that forms part of the Finale of the orchestral overture to the opera Il Pastor Fido (1712) was later rewritten as the last movement of the Keyboard Suite No. 3 in D minor, HWV 428, and again as the last movement of the Organ Concerto, Op. 7 No. 4. Bach transcribed some of his cantata movements as the ‘Schübler’ choral preludes for organ, while as director of the Leipzig Collegium Musicum, he rearranged his earlier violin concertos as keyboard concertos for the amateur musicians to play and rehearse at their weekly practices in Zimmermann’s Kaffeehaus. The Italian composer Francesco Geminiani took his compatriot Corelli’s famous Opus 5 collection of sonatas for violin and continuo and transformed them into concerti grossi.

This ease of transference was partly due to compositional techniques. The polyphonic lines of Baroque music could be readily transferred from one instrument to another, while the clear harmonic structure of the figuration meant that the single lines could be filled out with chords. So it was that Bach amplified his Prelude from the Solo Partita for violin BWV 1006 into the introduction to his cantata ‘Wir danken dir, Gott’, where it forms a glorious movement for obbligato organ, strings, oboes, and trumpets. (And some scholars have suggested that Bach’s famous Toccata and Fugue in D minor for organ may have begun life as a work for solo violin.) Bach also transcribed string concertos by Vivaldi for organ solo, partly to learn the compositional technique, as was Mozart’s motivation half a century later for transcribing Bach’s own keyboard fugues for string trio and quartet; but in so doing he couldn’t resist adding musical details and enriching the textures.

Yet there are examples of reworkings of material well into the Classical period. Some of the themes from Beethoven’s The Creatures of Prometheus resurfaced in the finale of the Eroica Symphony, while the composer also rearranged his violin concerto as a piano concerto and the entire Second Symphony for piano trio.

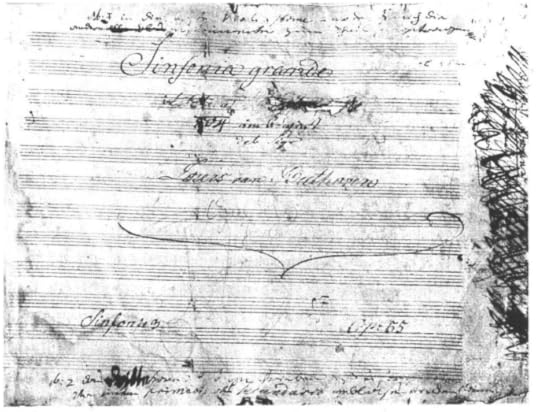

“Beethoven Symphony No.3 cover.” Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Beethoven Symphony No.3 cover.” Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. In the nineteenth century, the rise of the piano as the domestic musical instrument par excellence saw countless transcriptions of orchestral and chamber pieces published for piano solo and duet. At one level, in an age before recordings and mass concert-goings, this became a means of coming to know and appreciate this repertoire. At another, it provided the basis for the virtuoso piano transcription or ‘paraphrase’, such as Liszt’s Réminiscences de Don Juan, a fantasy for piano on themes from Mozart’s Don Giovanni so demanding that Liszt later published a two-piano version.

Sometimes the motivation for an arrangement seems to be a desire to ‘improve’ on the original. Thus we find versions of Beethoven’s Third Symphony rescored to take advantage of advances in instrument design. Rimsky-Korsakov did much to promote the music of his fellow Russian composer Mussorgsky through his reorchestrations, but was he prompted by homage or a wish to ‘correct’ faults he perceived in the original? When a composer orchestrates the work of another, the result can become a hybrid filled with the musical personality of the orchestrator. Ravel’s orchestration of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition shimmers with impressionist colour, while Bach’s Fantasia and Fugue in C minor for organ is so smothered in Elgar’s orchestration that it is almost transformed into a work by Elgar himself.

And so this desire to rework a musical composition for other forces has been a constant throughout music history. Whatever the motivation – practical, instructional, or homage – musicians cannot resist tinkering with pieces and transforming them into new works. Composing and arranging: perhaps these activities are more closely related than we think.

Image Credit: (1) “The Score for ‘An American in Paris’ by Kevin Harber. CC by NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr. (2) “Violin” by Emi Yañez. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The art of musical arrangements appeared first on OUPblog.

International copyright: What the public doesn’t know

Copyright these days is very high up on the agenda of politicians and the public at large. Some see copyright as a stumbling stone for the development of digital services and think it is outdated. They want to make consumers believe that copyright protection is to be blamed, when music or other ‘content’ is not available online, preferably for free.

From Brussels we hear that ‘national copyright silos’ should be broken up, that the EU Internal Market is fragmented when it comes to copyright – in short, an urgent need for copyright reform is claimed.

All this has put copyright in a defensive corner. But one cannot help the feeling that we may be talking cross purposes. Because, while all this heated debate is going on and gaining speed and intensity, there is a subtle and useful framework of copyright protection in place for more than 100 years, which has regularly been updated by lawmakers, not only by EU Member States and the EU, but literally from all over the world.

And as legitimate and pertinent the on-going discussions may be, they all cannot deny, but rather have to take account of, the international framework for copyright protection that is in place and is pretty much up to date.

How did this modern international framework come about?

Well, what happened at international level went almost unnoticed by the general public, including the many efforts that were needed to over the years to stabling this international copyright framework which agreed the balance of rights and interests across the world.

I am proud to have contributed to this framework in various capacities and on various occasions. In the beginning of my career, I attended meetings at the Council of Europe and the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), where the international copyright community discussed how to adapt copyright protection for new technologies, new market structures, and changing consumer behavior.

In the late 1980s, I joined the negotiations on the project of an international agreement on trade-related intellectual property rights (TRIPs) within the framework of the GATT/Uruguay round. The resulting World Trade Organization/TRIPs agreement was, in many respects, a true breakthrough for international law-making on copyright and industrial property alike, including its enforcement.

“While all this heated debate is going on and gaining speed and intensity, there is a subtle and useful framework of copyright protection in place for more than 100 years, which has regularly been updated by lawmakers, not only by EU Member States and the EU, but literally from all over the world.”

Then, in the 1990s, the focus of international copyright shifted towards what was called the ‘digital agenda’. This happened at a time when personal computers in the household became a huge success story, while new digital services like video-on-demand were gaining ground, and the internet grew above its infancy.

During that time, we prepared and negotiated what came to be known as the WIPO Internet Treaties – the two WIPO treaties of 1996 on copyright, the WCT (WIPO Copyright Treaty), and the WPPT (WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty).

What was so significant about these treaties?

Firstly, the fact that they were adopted at the Diplomatic Conference of December 1996 by a vast majority of the more than 150 participating countries from around the world makes them extremely significant. With this in mind, one could almost speak of an international consensus on copyright protection in the digital age.

Secondly, to say that these treaties added value is but a pale understatement. No, it was much more than that: the WCT and the WPPT included several innovative steps to update the balance of rights and interests on the substance of copyright protection. The firm establishment of the ‘three-steps test’ as an international standard for measuring and evaluating exceptions to and limitations of copyright; the introduction of the ‘making available’ right was particularly relevant for the marketing of new interactive services; and the protection of technical protection measures and rights management information paved the way for the management of copyright-related services on the internet.

At the time, I perceived it as a privilege and an important responsibility to be the Head of the EU Delegation at the Diplomatic Conference of 1996 where the treaties were adopted. And after the Diplomatic Conference, I thought it would be a mistake to not share this experience and all of the insights of our team with the outside world. Hence, the idea of writing a book about the two Treaties was born. Together with Silke von Lewinski, who was one of the main EU experts in my team, I published the book The WIPO Treaties 1996 in 2002.

However, a lot has happened since our 2002.

Both WCT and WPPT have now come into force, and at present each already has more than 90 members The Treaties have been implemented into national and – in the case of the European Union – regional law, with the implementing laws of the USA (the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, DMCA) and the European Union (the Information Society Directive 2001/29/EC) being prominent examples In 2009, the European Union adhered to, and became member of, the WCT and the WPPT in its own right Many provisions of the WCT and the WPPT have been interpreted and referred to by national and regional jurisprudence, including the Court of Justice of the European Union With the adoption of the Beijing Treaty on Audiovisual Performances (BTAP) in 2012, an important element of ‘unfinished business’ of the WPPT, the protection of audiovisual performers, was completed A specific element of protection that affects, inter alia, both the WCT and the WPPT is addressed in the Marrakesh Treaty of 2013.In various capacities, Silke and I have been actively involved in these developments. Therefore, we felt the time was right to publish a second edition of the book that includes a commentary on the BTAP, reference to jurisprudence, national and regional legislation and literature, as well as developments in international copyright law with relation to the WIPO Treaties. With digital copyright issues being on top of the agenda of many legislators right now, having full and updated insights into international copyright rules is more crucial than ever.

Featured Image: Globe, by Luke Price. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post International copyright: What the public doesn’t know appeared first on OUPblog.

February 23, 2015

Preparing for IBA and ICSID’s 18th Annual International Arbitration Day

The 18th Annual International Arbitration Day will take place 26-27 February 2015 at the Ronald Reagan Building in Washington, DC. A joint conference presented by the International Bar Association (IBA) Arbitration Committee and the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), International Arbitration Day will gather lawyers and academics to look back on investment arbitration and discuss its future, a theme that coincides with ICSID’s 50th anniversary.

The Young Practitioner’s symposium at Georgetown University Law Center kicks off the conference on Thursday afternoon. This is an interactive event for students and practitioners under age 40 co-hosted by the IBA Arb40 Subcommittee and the Young International Arbitration Group. A welcome reception for all International Arbitration Day delegates and registered guests will follow at the US Institute of Peace from 7:00-9:00 p.m.

International Arbitration Day starts on Friday morning with the IBA Mediation Committee breakfast featuring Michael Ostrove as one of the keynote speakers. The day’s first session is a retrospective of ICSID’s early years. Eduardo Silva Romero, one of the authors of the upcoming fourth edition of International Chamber of Commerce Arbitration, is the moderator, Christoph Schreuer and W. Laurence Craig will speak, and Antonio R. Parra and Jan Paulsson are slated to commentate on the topic.

The second session will focus on the ways investment arbitration fulfils (or does not fulfil) the purposes of BITs. The topic will certainly provoke an interesting discussion from the moderators and speakers, who will examine the effect of arbitral awards on investment law regime and how access to investment arbitration might foster foreign investment.

Following lunch and remarks from IBA President David W. Rivkin, David Caron will join fellow speakers and moderators to talk about procedural issues in investment arbitration such as time and cost, annulment, and more. The day’s final session will feature Lee M. Caplan and focus on the future of investment arbitration. Some of the talking points include what’s being done to address criticism that investment arbitration is elitist and the prospect of a shift to a permanent investment court body.

With a packed schedule of discussion and commentary, this year’s International Arbitration Day promises to be a busy and exciting event. Don’t forget to check out DC’s area attractions, many of which are in walking distance of the conference venue.

The Ronald Reagan Center is in close proximity to the Federal Triangle Metro station, a stop on the blue, orange, and silver lines. Two Smithsonian Museums, the National Museum of American History and the National Museum of Natural History, are just a few blocks down Pennsylvania Avenue and admission is free. If you’re interested in art and media, the National Gallery of Art and the Newseum are also in the area. The average high temperature at the end of February is around 40ºF /4ºC, making it possible to enjoy some of DC’s outdoor attractions. Stop by the White House and National Mall where you can see the Washington Monument, National World War II Memorial, Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Korean War Memorial and Lincoln Memorial. For a longer walk go to the Tidal Basin and visit the Thomas Jefferson Memorial, Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial, and Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial.If you are joining us in DC, visit the Oxford University Press booth where you can learn about our new online law products, browse our books, and take advantage of the conference discount, and pick up an Oxford journal. Arbitration International might be of particular interest to conference attendees. This journal provides quarterly coverage for national and international developments in the world of arbitration.

Want to brush up on investor-state tribunals before International Arbitration Day? Listen to a recording of our latest webinar, “Corrupting Investor-State Arbitration? The Role of Corruption Allegations in IIA Proceedings”. Ian Laird, Editor in Chief of Investment Claims, will moderate two rounds of debate from panelists Dr. Aloysius Llamzon, Brody Greenwald, Teddy Baldwin, and Professor Amy Westbrook. The webinar closes with a question and answer session.

For the latest updates about International Arbitration Day, follow us @OUPIntLaw and @OUPCommLaw and the IBA @IBAnews on Twitter. You can also like the IBA’s Facebook page. See you in DC!

Headline image credit: Business meeting. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Preparing for IBA and ICSID’s 18th Annual International Arbitration Day appeared first on OUPblog.

Why has France banned surrogate motherhood?

Shortly after it emerged in the 1980s, surrogate motherhood was dealt a severe blow in France by a decision of the Cour de Cassation, its highest civil court: in 1991, it ruled that an agreement entered into by a woman to conceive, bear a child, and relinquish it at birth, albeit for altruistic reasons, was contrary to the public policy principle of unavailability of both the human body and civil status. This prohibition was confirmed in the Bioethics Act of 1994 and enshrined in the Civil Code as a regulation which is “a matter of public policy,” i.e. belonging to a category of mandatory rules created by the state to protect fundamental values of society and from which citizens have no freedom to derogate.

In the last few years the issue of legalizing gestational surrogacy has resurfaced for many reasons. First of all, there is growing demand for autonomy, particularly with regards to individual life choices. There is also a persistent specific demand from women whose infertility is related to congenital malformation, cancer surgery, postpartum hemorrhage, or exposure to Distilbene. Last but not least, people can turn to international surrogacy in the US or in countries such as Ukraine and India where specialized clinics operate for foreigners. But when they return to France with children conceived in this way, substantiating ties of filiation is not straightforward.

Today, the prohibition of surrogate motherhood is supported by a majority of French citizens. It is justified by ethical concerns regarding the child, the surrogate mother, and society as a whole.

Recent decisions in French courts illustrate the complexity of enforcing this prohibition in a globalized world. They deny both adoption and recognition of children born abroad to surrogate mothers. The rule is to recognize what is legally done in other countries, except if it appears to be against fundamental principles. For instance, a divorce obtained in another country is considered valid except if it is a result of repudiation. Following this pattern, the Cour de Cassation decided that it was against one of these principles to register a child under the name of a woman who did not give birth to him; in the Mennesson case in 2008, it ruled that the transcript of the birth certificate of a child born to a surrogate mother in California was unlawful even though the child had obtained his birth certificate there and was a US citizen.

Then came the case of a same-sex couple who had travelled to India to get a child through surrogacy. The “mother” had an Indian name and the biological father had issued a declaration of paternity; the court again refused to register the birth certificate, basing its decision on French citizens being unable to go abroad to circumvent French surrogacy laws.

Of course, the Cour de Cassation took into consideration the best interests of those children. Even though the child’s filiation is not recognized in France, as he had a foreign birth certificate, he was not prevented from living in France with the couple and had the same rights as other foreign children regarding school and healthcare. Had the judges accepted de facto a surrogacy performed abroad, it would have been inconsistent with its strict prohibition in France. Moreover, were the child’s best interests to be considered paramount, child abduction and trading could well be justified in some extreme circumstances, making other international conventions, such as The Hague Convention on Adoption, inapplicable and obsolete.

Today, the prohibition of surrogate motherhood is supported by a majority of French citizens. It is justified by ethical concerns regarding the child, the surrogate mother, and society as a whole.

…it is highly plausible that some surrogates are acting entirely of their own free will, but it is still wrong for society to accept a form of alienation, however voluntary.

Firstly, children may be psychologically at risk in such transactions. Ignoring or denying the effects of pregnancy and the mother-child relationship on the child’s future could well be damaging for him or her as well as for the intended parents; and children could become commodities traded as merchandise between surrogate mothers and infertile couples.

Secondly, even aside from the physical risks of pregnancy, the gestational mother is exposed to two dangers: becoming attached to the child and suffering from the separation after birth, since she knows that, for her, childbirth will mean an end rather than a beginning. France is also concerned about the fact that there is an inherent social division in this practice: surrogate mothers are usually from lower economic backgrounds and can be economically exploited in this transaction.

Thirdly, surrogacy could threaten the symbolic image of women (“Marianne” is the female symbol of the Republic) and the principle of human dignity that enjoys constitutional recognition. In France, dignity is often regarded as an obligation that individuals owe themselves to remain worthy of their human condition. Individuals are free to decide what constitutes their own dignity provided the dignity of others is not harmed.

While it is highly plausible that some surrogates are acting entirely of their own free will, it is still wrong for society to accept a form of alienation, however voluntary.

Still, in the wake of a recent ruling of the ECHR in the Mennesson case, read on 26 September 2014, France may well be poised to recognize international surrogacy. The Court decided that although France had not violated the right of the commissioning parents and of the children to respect for family life, a violation of the child’s right to respect for their private life (article 8) had occurred. France had gone beyond its margin of appreciation by refusing to recognize under French law children who had French biological fathers: it is extremely interesting that the decision of the Strasbourg court is based on “the importance of biological parentage as a component of each individual’s identity”. This means that France is not forced to automatically recognize any kind of international surrogacy.

The government did not announce new measures to comply with this decision. It is politically easier to wait until another judicial complaint is made and see how the Cour de Cassation reflects the new direction set by the European Court.

Indeed, legal choices are extremely difficult to make: an ideal solution would be to enforce the intention of the French legislator to ban surrogacy while ensuring children do not suffer from discrimination on account of their parents infringing the law. Unfortunately, one struggles to see how to recognize some situations legally established abroad without paving the way for sordid human trading, ultimately leading to so-called “ethical surrogacies” in our country.

Image Credit: “Palais de Justice, Paris, 26 Sept. 2009.” Photo by Phillip Capper. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Why has France banned surrogate motherhood? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers