Oxford University Press's Blog, page 693

March 2, 2015

How do Russians see international law?

Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 was a watershed in international relations because with this act, Moscow challenged the post-Cold War international order. Yet what has been fascinating is that over the last few years, Russia’s President and Foreign Minister have repeatedly referred to ‘international law’ as one of Russia’s guiding foreign policy principles. This is awkward because in 2004 Russia had ratified a bilateral treaty with Ukraine — not to mention the 1994 Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances (based on which Ukraine gave up its nuclear weapons and in return Russia participated in guaranteeing Ukraine’s territorial integrity along the Soviet-era borders).

So is the Kremlin’s talk of Russia’s support for ‘international law’ all empty or is there something perhaps less visible to the eye behind this claim? I would argue that major nations inside and outside the West to some extent understand international law differently from each other. Aspects such as how one’s civilization is constructed and how does the country do on the scale of democracy versus authoritarianism play a major role in its understanding and use of international law.

Regarding Russia’s re-conquest of Crimea, realists would of course argue that this is what Great Powers do – that they use the rhetoric of international law as fig leaf in their pursuit of power. Indeed, the idea of balance of power seems very prominent in Russia’s thinking on the United Nations, NATO, and international law.

In Russia’s case, one important aspect is that Russia imported the discourse of international law from Western Europe only in the 18th-19th centuries, i.e. several centuries later than international law came to be practiced and theorized in the West. International law came to Tsarist Russia to some extent as foreign language. Although Russian scholars and diplomats like Martens learned to speak this language well, it didn’t grow out naturally from Russia’s own domestic legal ideas and practices.

Furthermore, the whole Communist period (1917-1991) was a legal-normative turning of the back towards the West and ‘Europeanization’. Moscow insisted that it had created for Eastern Europe a unique ‘socialist international law’ which differed from international law of the capitalist West. Thus, Russia’s historical ambivalence regarding Europe and the West has had an impact on the country’s use of international law as (to some extent) a foreign language in which words hide and confuse as much as they reveal.

Moreover, a country’s approach to international law reflects its domestic concepts of law and the relationship between the government and the individual. If a country’s legal culture has been criticized as ‘nihilist’ by its own leaders, contradictions in its international legal arguments should not surprise us so much. If law is a means rather than high societal value in itself, it is not so awkward to use contradicting arguments.

Арбитражный суд Московского округа. Photo by Pardus2. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Арбитражный суд Московского округа. Photo by Pardus2. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Compared to the West, anthropocentric liberal ideas haven’t until now become predominant in Russia. This also mirrors in the theory of international law. For example, the leading post-Soviet international law theoretician, Stanislav Chernichenko, rejects the idea that individuals could be subjects of international law besides the states, and propagates the theory of dualism that rejects direct applicability of international law. Russian experts writing on international law often distinguish between the Western and the Russian doctrines assuming that these might be different to some extent.

The main difference between Russian and Western approaches to international law is an axiological one; it concerns the question of which values in international order are prioritized and which ones are secondary. In Russia, ideas emphasizing state sovereignty rather than human rights, not to speak of democracy, are constantly reflected in the state practice. Russia’s record in the European Court of Human Rights has clearly been among the weakest, and more importantly, problems have been of a systemic, not accidental nature. But Russia has also been an under-performer in international investment law because it has rejected the idea that the capital recipient state and the foreign investor might settle their dispute in binding investor-state arbitration – a practice that has become standard in the West.

Perhaps the broadest and most fascinating dynamic in Russia’s recent use of the language of international law has been the idea that it represents a distinct ‘civilization’ and thus no longer is part of ‘Europe’. References to Russia as unique (and, of course, non-Western) ‘civilization’ have penetrated international legal rhetoric and theory in the country.

Altogether, the West has made a mistake over the last decade of failing to pay enough attention to what the Russians thought about international law and order. Moreover, the West wasn’t concerned enough about the potential precedent value of the use of military force against Yugoslavia (1999) and Iraq (2003); Moscow in turn has used these conflicts as a pretext for using military force itself.

The general ramifications in public international law has put the whole UN system in serious turmoil. A lot is at stake. In order to make realistic policy choices regarding challengers to international law (like Russia), a sense of from where all major players historically and normatively come is urgently needed. Perhaps then it will be possible to take other nations outside the West in the way that they actually are, not how we would like them to be.

Header image: Russian Honor Guard. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post How do Russians see international law? appeared first on OUPblog.

How do we protect ourselves from cybercrime?

Modern society requires a reliable and trustworthy Internet infrastructure. To achieve this goal, cybersecurity research has previously drawn from a multitude of disciplines, including engineering, mathematics, and social sciences, as well as the humanities. Cybersecurity is concerned with the study of the protection of information – stored and processed by computer-based systems – that might be vulnerable to unintended exposure and misuse.

We seem to see new reports of hacking every week, ranging from the social media profiles of Taylor Swift and Centcom, to the email accounts of Sony, to at-home security gadgets such as baby monitors. Certain types of hacking, such as using a public hotspot to access information on someone else’s computer, are mere child’s play, as demonstrated by this 7-year-old. Such public hotspots are used in hundreds of thousands of restaurants, hotels, and other locations throughout the UK. So how do we – companies, institutions, and individuals – protect ourselves from cybercrimes?

Computer-based systems that store and process confidential, sensitive, and private information are vulnerable to attacks exploiting weaknesses at the technical, social, and policy level. Attacks may seek to compromise the confidentiality, integrity, or availability of the information, as well as violate the privacy of the information’s owners and stakeholders.

One reason why achieving cybersecurity is so hard in practice is that systems are often designed in isolation, but operate as parts of a broader ecosystem. In such an environment, delivering complex sets of services, the defenders may be less interested in the security of a particular system and more in the overall sustainability and resilience of the ecosystem. Systems across sectors – financial, transport, retail, health, communications, etc – are massively interconnected. Vulnerabilities in systems in one sector – that may be exploited by criminals, terrorists, nation-states – may lead to critical failures in others.

Privacy Policy. Public Domain via Pixabay

Privacy Policy. Public Domain via PixabayThe extent of the threat to the information ecosystems upon which modern societies depend, and the scale of the required response, is increasingly being recognised by major governments, with substantial research and development funds being made available. Moreover, the solutions to cybersecurity problems also span the technical and policy layers.

Understanding how these ecosystems operate requires an interdisciplinary approach: for example, computer scientists to design the software and networks; cryptographers to protect confidentiality of communications; economists to explain how the competing incentives of stakeholders might play out; anthropologists to explain cultural contexts and how they impact solutions; psychologists to explain how decisions are made and the impact on system design; the legal and policy scholars to set out regulatory constraints; criminologists and crime scientists to explain the motivation of perpetrators; and experts in strategy to frame the international context. Consequently, cybersecurity research cannot remain siloed. Instead, rigorous, interdisciplinary scholarship that incorporates multiple perspectives is required.

Future successes in cybersecurity policy and practice will depend on dialogue, knowledge transfer, and collaboration.

Image credit: Security. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post How do we protect ourselves from cybercrime? appeared first on OUPblog.

March 1, 2015

Does marijuana produce an amotivational syndrome?

Does marijuana produce an amotivational syndrome? Whether the amotivational syndrome exists or not is still controversial; there are still too few poorly controlled small studies that don’t allow a definitive answer. Most people who use marijuana don’t develop this syndrome.

The few existing studies suggest that people who user moderate amounts of marijuana show no personality disturbances. In contrast, people who are heavy users of marijuana for a prolonged period of time are characterized as suffering from apathy, dullness, lethargy, and impairment of judgment, i.e. the classic amotivational syndrome. This finding raises the important issues of how much does the term “moderate” imply, how long have the people in these studies been smoking marijuana, and at what age did they begin smoking.

Why might this syndrome only develop in some long-term users? The answer lies in understanding the behavior of our brain. Our human brain produces its own endogenous marijuana-like chemicals. One of them is called 2-AG and is the most abundant of the endogenous marijuana-like chemicals; the other is called anandamide.

When we consume lots of fat our brain rewards us by releasing 2-AG and anandamide; it makes us feel happier and induces us to eat more fat. 2-AG and anandamide induce their effects in the brain by attaching to proteins called receptors. This process is similar to a key fitting into a lock. However, the brain’s response can be a little more complicated. If we repeatedly insert our key (fat or marijuana) into the lock (receptor protein) too many times or too often the brain does something really strange: it takes away the lock. Thus the person needs to eat or smoke more and more in order to find the reduced number of locks. Are there any long-term consequences to having fewer working receptors (locks) in the brain?

Marijuana. CC0 via Pixabay.

Marijuana. CC0 via Pixabay. Until recently, no one really knew the answer to this question. Then, in 2006, a drug called Acomplia was introduced in the UK market for the treatment of obesity. Acomplia was invented based upon the recognition that marijuana induces “the munchies,” a strong craving for high-calorie foods. This well-known side effect of marijuana indicated that the brain’s feeding center possessed endogenous marijuana receptors. Acomplia was designed to block these receptors, and thus block cravings for high-calorie food. Acomplia worked very well as an anti-obesity drug but it had a very nasty side-effect: it caused severe depression and suicidal thoughts. The drug was withdrawn from the market.

The actions of Acomplia taught neuroscientists an important lesson about the role of our brain’s endogenous marijuana system: we need it to function normally in order to experience everyday pleasures. If the endogenous marijuana receptors are blocked 24-hours each day, day after day, we lose the ability to experience pleasure and become apathetic and depressed.

Thus, long-term use of marijuana may, depending upon many factors such as genetics and age, ultimately produce a condition in the brain that is very similar to amotivational syndrome – the symptoms of which are very similar to the symptoms of depression.

The post Does marijuana produce an amotivational syndrome? appeared first on OUPblog.

Democracy is about more than a vote: politics and brand management

With a General Election rapidly approaching in the UK, it’s easy to get locked into a set of perennial debates concerning electoral registration, voter turnout and candidate selection. In the contemporary climate these are clearly important issues given the shift to individual voter registration, evidence of high levels of electoral disengagement and the general decline in party memberships (a trend bucked by UKIP, the Greens, and the Scottish National Party in recent months).

My concern, however, is that democracy has to be about far more than a vote. It’s not just about elections; it’s certainly not just about political parties and the risk of the 2015 General Election is that without being embedded within a range of more creative and engaging forms of political participation it’s just . . . another election.

Politics therefore has an important challenge in terms of ‘brand management’. Not of the vacuous form of ‘Russell Brand Management’ but of the challenge of re-imaging, redefining and re-connecting with a public that has (and is) changing rapidly; a mass social frenzy around the General Election risks creating a situation of boom-and-bust in terms of the public’s expectations and the subsequent results in terms of governmental performance in an increasingly complex world.

I can’t help wondering if democratic politics even has the capacity anymore to produce those social highs of yesteryear — the ‘Obama effect’ or ‘Blair effect’ — where there was a real sense that positive reform was both possible and on the horizon. Could it be that democratic boom-and-bust (a largely inevitable element of democratic life) has been replaced by the dull thud of bust-and-bust politics?

Voting in Hackney by Alex Lee. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Voting in Hackney by Alex Lee. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. The General Election risks becoming part of the traditional life-cyle of politics that seems to be turning an increasingly large slice of the public away from ‘conventional’ politics. But, then again, does UKIP in the UK — or Podemos in Spain, the Five Star Movement in Italy, the National Front in France, or Syriza in Greece — really offer a rejuvenated model of democracy or (and this is the critical point) simply a thinner and more dangerous form of exclusionary politics? Is the boom-and-bust of populism not potentially louder and more destructive? In many ways the populist parties are a legitimate ‘challenger brand’ but they offer democracy a potentially dangerous dilemma.

In an excellent recent essay on democratic discontent Claudia Chwalisz highlighted that two decades have passed since Arend Lijphart famously identified unequal participation as ‘democracy’s unresolved dilemma’ and this dilemma has intensified rather than diminished in the intervening years. Why? Because the correlation between voting and policy-making has eroded to the extent that the public now question whether voting actually matters. To some extent this is an issue of perception as much as reality — a perception reinforced by the ‘Russell’ approach to Brand Management. It is also, to some extent, an inevitable element of democratic politics that as the demands of the populous become more complex and varied then the compromise-orientated element of that worldly art called politics will reflect this fact and become increasingly opaque. But there is something else going on — the insulation of a dominant economic elite that appears almost insulated from democratic control or scrutiny. Votes don’t seem to affect the cosmopolitan business elite and, as a result, capital in the twenty-first century is eroding democratic politics.

My message? Don’t expect too much from the 2015 General Election for the simple reason that democracy is about far more than a vote. It is about everyday life, it is about community engagement, it is about personal confidence and belief, it is about daring to stand up and be counted and its about the art of life and living together in the twenty-first century. The problem is that democratic politics has become a toxic brand and it need to re-brand itself by offering a new and fresh account of both the challenges and opportunities that undoubtedly lay ahead. That is a model of democracy that is deeper and richer, creative and honest, formal and informal, amateur and professional, agile and responsive, as responsibility-based as rights-based and as innovative as it is international. The problem is that at the moment ‘democracy’ appears almost synonymous with ‘elections’ and this robs it of its potential.

Democracy is about more than a vote.

Heading image: Election MG 3455. By Rama. CC BY-SA 2.0 fr via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Democracy is about more than a vote: politics and brand management appeared first on OUPblog.

Creating a constructive cultural narrative for science

The Oxford Research Centre for the Humanities (TORCH) is currently running a series of events on Humanities and Science. On 11 February 2015, an Oxford-based panel of three disciplinary experts — Sally Shuttleworth (English Literature), John Christie (History), and Ard Louis (Physics) – shone their critical torchlights on Durham physicist Tom McLeish’s new book Faith and Wisdom in Science as part of their regular ‘Book at Lunchtime’ seminars.

How can we understand the relation between science and narrative? Should we even try to? Where can we find and deploy a constructive cultural narrative for science that might unlock some of the current misrepresentations and political tangles around science and technology in the public forum?

In exploring the intersection of faith and science in our society, positive responses and critical questions at the recent TORCH Faith and Wisdom in Science event turned on the central theme of narrative. Ard Louis referred to the book’s ‘lament’ that science is not a cultural possession in the same way that art or music is, and urged the advantage of telling the messy story of real science practice. John Christie sketched the obscured historical details within the stories of Galileo and Newton, and of the Biblical basis beneath Frances’ Bacon’s vision for modern science, which serve to deconstruct the worn old myths about confrontation of science and religion. Sally Shuttleworth welcomed the telling of the stories of science as questioning and creative, yet suffering the fate of ‘almost always being wrong’.

http://media.podcasts.ox.ac.uk/humdiv/torch/2015-02-15_torch_mcleish.mp4

What resources can Judeo-Christian theology supply in constructing a social narrative for science – one that might describe both what science is for, and how it might be more widely enjoyed? The project we now call ‘science’ is in continuity with older human activities by other names: ‘natural philosophy’ in the early modern period and in ancient times just ‘Wisdom’. The theology of science that emerges is ‘participatory reconciliation’, a hopeful engagement with the world that both lights it up and heals our relationship with it.

But is theology the only way to get there? Are we required to carry the heavy cultural baggage of Christian history of thought and structures? Shuttleworth recalled George Eliot’s misery at the dissection of the miraculous as she translated Strauss’ ‘Life of Jesus’ at the dawn of critical Biblical studies. Yet Eliot is able to conceive of a rich and luminous narrative for science in Middlemarch:

“…the imagination that reveals subtle actions inaccessible by any sort of lens, but tracked in that outer darkness through long pathways of necessary sequence by the inward light which is the last refinement of energy, capable of bathing even the ethereal atoms in its ideally illuminated space.”

Eliot’s sources are T.H. Huxley, J.S. Mill, Auguste Compte, and of course her partner G.H Lewes – by no means a theological group. (Compte had even constructed a secular religion.) Perhaps this is an example of an entirely secular route to science’s story? Yet her insight into science as a special sort of deep ‘seeing’ also emerges from the ancient wisdom of, for example, the Book of Job. In his recent Seeing the World and Knowing God, Oxford theologian Paul Fiddes also calls on the material of Proverbs, Job, and Ecclesiastes to challenge the post-modern dissolution of subject and object. Participatory reconciliation emerges for both theologian and scientist motivated to draw on ancient wisdom for modern need. Was Eliot, and will all secular thinkers in the Western tradition be, in some way irrevocably connected to these ancient wellsprings of our thinking?

An aspect of the ‘baggage’ most desirable to drop, according to Shuttleworth, is the notion that scientists are a sort of priesthood. Surely this speaks to the worst suspicions of a mangled modern discourse of authority and power? Louis even suggested that the science/religion debate is really only a proxy for this larger and deeper one. Perhaps the Old Testament first-temple notion of ‘servant priesthood’ is now too overlain with the strata of power-play to serve as a helpful metaphor for how we go about enacting the story of science.

But science needs to rediscover its story, and it is only by acknowledging that its narrative underpinnings must come from the humanities, that it is going to find it.

Headline image credit: Lighting. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Creating a constructive cultural narrative for science appeared first on OUPblog.

Nineteenth and twentieth century Scottish philosophy

In the history of Britain, eighteenth century Scotland stands out as a period of remarkable intellectual energy and fertility. The Scottish Enlightenment, as it came to be known, is widely regarded as a crowning cultural achievement, with philosophy the jewel in the crown. Adam Smith, David Hume, William Robertson, Thomas Reid and Adam Ferguson are just the best known among an astonishing array of innovative thinkers, whose influence in philosophy, economics, history and sociology can still be found at work in the contemporary academy.

The phenomenon of Scottish intellectual life in the eighteenth century, and the widespread interest that it continues to attract, makes it all the more surprising that this was not, in fact, the period in which Scottish philosophy achieved its highest international profile. That distinction came in the century that followed. It is in the nineteenth century that Scottish philosophy set the academic agenda for philosophical debate in Europe and America, provided texts for college students across Canada and the United States, and produced a steady supply of university teachers, not only for North America, but Australia and New Zealand as well.

Scottish philosophy in the nineteenth century had intellectual luminaries who, in their own day, shone even more brilliantly than many of their eighteenth century predecessors. The posthumously published lectures that Thomas Brown gave at Edinburgh went into dozens of editions and were studied for decades. Sir William Hamilton, Professor of Logic and Metaphysics at Edinburgh, was hailed as possibly the most learned Scot who ever lived, and the greatest metaphysician of his age. James Frederick Ferrier at St Andrews ranked as one of Europe’s leading intellectuals. Alexander Bain at Aberdeen laid new and firmer foundations for the emerging science of empirical psychology. Edward Caird at Glasgow inspired a whole new generation of philosophers, who went on to teach philosophy at home and abroad.

Statue of David Hume, Edinburgh, by TwoWings. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Statue of David Hume, Edinburgh, by TwoWings. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Yet, in sharp contrast to Smith, Hume, and so on, these names are now virtually unknown. The things they thought and why they thought them, the books they wrote, the debates they had, the people they influenced, have all fallen far below the intellectual radar of the twenty first century. The only survivor, arguably, is Bain’s friend John Stuart Mill, and though the roots of his philosophical work are easily identified as Scottish, this connection generally goes unnoticed.

Why is there this dramatic difference between these two centuries of Scottish philosophy, one heralded far and wide, the other for the most passed over in silence? Just who were these thinkers and why were they so influential? How did they fall into such neglect? Is their work still worth anything? Did they build significantly upon their Enlightenment heritage, or are they properly relegated to the status of footnotes to it? The existence and social role of Scotland’s four ancient universities meant that, for a long period, the professors of philosophy and their students constituted a genuine intellectual community. Over many generations they sought to maintain and to enlarge a tradition of philosophical inquiry that aimed to unite research and education, bringing scholarly inquiry of international relevance to bear directly on the formation and enrichment of Scotland’s social and cultural life.

This admirable ambition gradually came under pressure, from a number of directions. In Scotland, increasing familiarity with Kant and Hegel began to change the relatively isolated philosophical world of the Scottish Enlightenment, while the development of academic specialization gave new independence to politics, economics and psychology, subjects that philosophy had previously included. In Britain at large, improved communication and the establishment of new universities in England, Ireland and Wales eroded the distinctiveness of the Scottish university system. In America, the Scottish philosophy of common sense morphed into philosophical pragmatism. In the antipodes, Australia and New Zealand began to forge philosophical traditions of their own.

At the turn of the twentieth century and into its opening decades, those raised in the Scottish philosophical tradition acknowledged its passing with a mixture of hindsight, nostalgia and regret. George Davie’s powerful lament, The Democratic Intellect published in 1961, may be said to mark its final demise. Yet there is something of importance to be learned from it. The radically altered nature of our institutions of higher education has recently occasioned a flurry of books. Their shared concern is captured by the title of one of the volumes — Stefan Collini’s What are Universities For? This is a question with renewed, some would say urgent, interest for the contemporary academy. And Scottish philosophy in the nineteenth century still has much to teach us about how to frame it.

Featured image credit: Edinburgh Castle, by David Monniaux. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Nineteenth and twentieth century Scottish philosophy appeared first on OUPblog.

February 28, 2015

Clarity about ‘the gay thing’

Sometimes, we say what we don’t really mean. ‘You look really tired’, for example, when we mean to be caring rather than disparaging of appearance. ‘I thought you were older than that!’ when we mean to applaud maturity rather than further disparage appearance.

And so it is with the gay thing. The accidental difference between what people are saying or writing, and their intended meaning, is becoming perplexingly polarized. It’s becoming an issue because respected news sources with style guides to guard the objectivity of their reporting are straying away from neutral. And this, in turn, is influencing what we consider to be untainted, unprejudiced language about what I’m technically going to call ‘the gay thing’.

The lexicon around neutral language when reporting or writing about lesbian and gay people can lead to misunderstanding. There are several words that sit outside the flagrantly offensive, but in a grey area. It’s not malice, but misunderstanding that causes people to use these murky terms. They don’t intend to insult, but they do intend to be unbiased. Clarity is lost with the terminology we think is clear and plain English. It’s not.

Here are some examples.

What people say: sexual preference

What they really mean: sexual orientation

I actually think that at least three quarters of people and organizations that use this term, are intending to mean something else. If you believe, as all the science available to us indicates, that being gay is attributed to nature and not nurture; that it’s genetic and not a choice, then this term is a common misuse.

My preference is for mocha rather than latte; mashed potato rather than boiled; Madonna rather than Kylie. My sexual orientation is not a casual preference or a choice, like choosing whether I want pizza or pasta. I don’t merely prefer men to women. It’s something innate.

Some gay people find it offensive when it’s suggested that their sexual orientation is a choice; it trivializes the discrimination they’ve had to overcome by suggesting that they’ve just been obstinate and could always have chosen another path. It can also load with ammunition the traditional enemies to equality who’ll argue any measures to accommodate someone’s picky preference are not high priority.

Sexual orientation is clearer and less likely to lead to misunderstanding – without being overly fussy, it strongly insinuates that you’re born with an imaginary inner compass that points in a certain direction on the Kinsey Scale.

Even if you do believe nurture plays a part in sexual orientation, the term sexual preference could still be a misnomer. Some parts of our character are so deeply ingrained from the nurture of our early childhoods, that we have little conscious choice over how they manifest as adults. When deconstructed, the term ‘preference’ relating to sexuality seems, quite frankly, peculiar.

It’s particularly peculiar when it comes from progressive news outlets, such as the Guardian.

What people say: homosexual / homosexuals

What they really mean: gay / gay people

The Guardian, however, listens and learns as language moves on from where it once stigmatized. I write a monthly column for the Guardian’s ‘Mind your language’ section and I successfully challenged them to drop homosexual used as a noun from their official style guide. It has now been replaced with gay people.

Why did I do this? Calling gay people homosexuals is the cold, medical, dehumanizing language used when homosexuality was, until 1992, classified as a mental disorder. It’s like calling people ‘homo sapiens.’ It’s stuffy, it jars and, I argued, it can no longer be deemed to come from a neutral, objective place due to the word’s unsavoury history on medical statutes, such as those used to chemically castrate Alan Turing for being gay.

When working at gay equality charity Stonewall, I also perceived the term homosexualsto be used by enemies of equality in a very clever way; they weren’t using outright insulting language that could easily be called out, but instead this careful, distanced, clinical language that makes gay people seem like an alien breed, worthy of scientific experiment. The term’s insidiousness is its insult.

What people say: gay rights

What they really mean: equality

Fighting for gay rights all sounds very Harvey Milk and uplifting. But the term may not be as empowering as it seems. Introducing gay rights sounds like a long list of special, extra demands gay people insist on having while beating drums and shouting. When, in fact, what I believe the majority of people are really intending when they say gay rights is equality. Why is this important? Equality is measured, palatable, entirely reasonable and sensible, and more likely to be accepted by all classes, people on both the left and right of the political divide. It sounds less entitled. It’s also far harder to argue against.

Gay rights, in effect, insinuates gay people want to be treated specially and differently when in fact the opposite is true. We want to be treated the same. That’s why measures such as an equal age of consent use the vernacular of equality, as opposed to rights.

What people say: gay marriage

What they really mean: marriage

Before marriage finally became a legal reality for same-sex couples in Britain last year, much was written in the media about ‘gay marriage’ as if it were a separate institution, requiring that qualifying prefix. ‘The campaign for equal marriage’ would’ve been a more accurate descriptor of what lay behind the campaign, in a similar rationale to the significant semantics around ‘rights vs equality’. As a Facebook friend of mine posted at the time: “I’m just going to get on my gay bus with my gay girlfriend and then we’re going to the gay airport on a gay holiday” – the prefix feels superfluous on all these words, just as it does with marriage.

What people say: tolerance

What they really mean: acceptance

Another linguistic bugbear of mine. I tolerate mushrooms; I don’t really like them. I can tolerate the pain of getting a tattoo done, though I’d prefer to do without it. I tolerate people walking slowly and aimlessly in front of me – just – but I hardly welcome it. Yet, in many of the places I’ve heard ‘tolerance’ used as a synonym for open-mindedness, I’ve often felt that acceptance is the clearer term – gently implying warmth, but, in a very British way, keeping it understated and straightforward.

I accept, though, that not everyone will tolerate this.

A version of this blog post first appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Image Credit: “Mr. and Mr. Marriage Equality.” Photo by Purple Sherbert Photography. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Clarity about ‘the gay thing’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Emily Brontë, narrative, and nature

Are you following along in the Oxford World’s Classics Reading Group? What new insights have you gained on the windswept moors? To take a closer look at how Emily Brontë uses nature to convey narrative, we present the following extract from Helen Small’s introduction to Wuthering Heights. We hope this provides some further insight as you continue reading.

Catherine’s removal from the plot (other than as a haunting presence in the background, much less potent hereafter than the waif-like child ghost whose wrist Lockwood rubs back and forth across the broken window glass till the blood runs freely (p. 21)) has seemed to some readers to weaken the second half of the novel. One modern critic has suggested, indeed, that the whole of the second-generation narrative was an afterthought. In The Birth of Wuthering Heights (1998), Edward Chitham advances a theory, based on the little evidence remaining for the novel’s timetable of composition, that the addition of most of the material beyond this point was prompted by a publisher’s rejection of the three-novel set which the Brontë sisters sent out in 1846 (Charlotte’s The Master — later reworked as The Professor, Emily’s Wuthering Heights, and Anne’s Agnes Grey). When The Master was rejected outright, Charlotte withdrew from the enterprise and committed herself instead to the writing of Jane Eyre. In consequence, Chitham suggests, Emily undertook to revise and expand Wuthering Heights from a single-volume narrative, ending presumably in Catherine’s death, to one that would fill two volumes. By doing so, she would have been turning a concentrated story of love, betrayal, and haunting into a far more psychologically complex narrative of revenge — ruthlessly pursued, ultimately abandoned.

Chitham’s speculations rest on unevenly persuasive claims about the possible timetable for writing Wuthering Heights, but the core supposition with respect to its initial length seems plausible. If that core element in his thesis is right, the idea that Emily Brontë was willing to alter the narrative fundamentally to produce an optimistic conclusion would not in itself be out of character. In her poetry, and much of her other prose writing, she regularly gravitates towards narrative or lyrical structures in which initial bleakness is transformed to optimism by a sudden change in the appearances of nature. Commonly that change performs a quiet allegory of Christian hope. ‘O come’, the night breeze whispers to the speaker of a poem dated September 1840:

“I’ll win thee ’gainst thy will –

“Have we not been from childhood friends?

“Have I not loved thee long?

“As long as thou hast loved the night

“Whose silence wakes my song?

“And when thy heart is resting

“Beneath the churcheyard stone

“I shall have time for mourning

“And thou for being alone”–

The ending imitates a memento mori, but the voice of the wind, which entirely displaces that of the opening speaker, is strongly resistant to the pessimism associated in this poem with ‘human feelings’. A ‘devoir’ piece written during Emily Brontë’s time as a student in Brussels, and titled ‘The Butterfly’, similarly begins with the speaker recalling a mood of blighting antagonism to nature: ‘Nature is an inexplicable problem; it exists on a principle of destruction’. The discovery of a caterpillar within a flower seems to confirm this miserabilist philosophy: ‘“Sad image of the world and its inhabitants!”’ Then a butterfly, rising among the leaves, and vanishing ‘into the height of the azure vault’ suddenly banishes despair: ‘God is the god of justice and mercy; then, surely, every grief that he inflicts on his creatures, be they human or animal, … is only a seed of that divine harvest’ to come.

Headline image credit: Farm in Yorkshire Dales. Photo by minniemouseaunt. CC BY 2.0 via minniemouseaunt Flickr.

The post Emily Brontë, narrative, and nature appeared first on OUPblog.

Five Biblical remixes from Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Civil Rights icon Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was also a theologian and pastor, who used biblical texts and imagery extensively in his speeches and sermons. Here is a selection of five biblical quotations and allusions that you may not have noticed in his work (in chronological order).

“And there is still a voice saying to every potential Peter, ‘Put up your sword.'”

Following the Detroit Walk to Freedom in 1963 in Detroit, Michigan, King spoke to a huge audience at Cobo Hall. In the speech, he encouraged the crowd to support and employ methods of non-violent resistance. The “potential Peter” refers to Peter’s use of violence after Jesus’s betrayal by Judas and subsequent arrest in John 18. Simon Peter cuts of the ear of the high priest’s slave, and Jesus tells him to put away his sword. (Also see Matthew 26; Mark 14; and Luke 22.)

“We will not be satisfied until ‘justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.'”

At the famous 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, King encouraged the marchers to continue to march forward and to refuse to turn back. Responding to those who ask when the demonstrators will be satisfied, King quoted Amos 5:24. In this text, the author of Amos indicates that the Lord will reject the festivals and sacrifices of the proud and powerful and instead bring justice and righteousness.

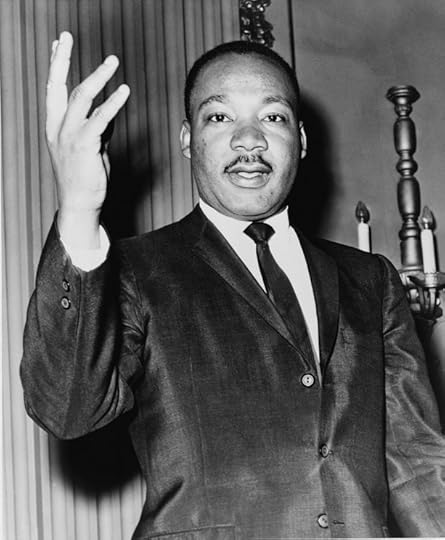

Martin Luther King, Jr. By Dick DeMarsico, World Telegram staff photographer. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Martin Luther King, Jr. By Dick DeMarsico, World Telegram staff photographer. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.“And the lion and the lamb shall lie down together, and every man shall sit under his own vine and fig tree, and none shall be afraid.”

At the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize Ceremony in Oslo, Norway, King gave this acceptance speech in which speaks of his continued hope and faith in humanity. In this quote, he cites two eighth-century BCE prophets, Isaiah and Micah. In Isaiah 11:6, the reign of the ideal king will permit natural adversaries to live together in harmony. In Micah 4:4, a new age of peace will allow nations to convert weapons into farming tools and to live peacefully and securely without fear.

“And thereby speed the day when ‘every valley shall be exalted, and every mountain and hill shall be made low the crooked shall be made straight, and the rough places plain.'”

King’s 1967 Beyond Vietnam speech is not as well-known as many of his other speeches and sermons. King spoke out against the Vietnam War at Riverside Church in New York City, discussing the importance of revolution and mentioning how Western nations created by revolutionaries become anti-revolutionary. King argued that continued challenges to the political status quo will bring about change. In this context, he cited Isaiah’s message of comfort and solace to exiled Israel in Isaiah 40:4, which calls for a new Exodus.

“And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over, and I’ve seen the Promised Land.”

In his famous 1968 “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech — delivered the night before his assassination in Memphis — King mentioned being stabbed by Izola Curry in 1958 and explained that he is not concerned with living a long life. King compares himself to Moses who sees the land that God has given to the Israelites although he himself does not enter (See Numbers 27:12 and Deuteronomy 34).

Image: President Lyndon B. Johnson meets with Martin Luther King, Jr. at the signing of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Five Biblical remixes from Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. appeared first on OUPblog.

Rebel Girl: Lesley Gore’s voice

In 2005, Ms magazine published a conversation between pop singer Lesley Gore and Kathleen Hanna of the bands Bikini Kill and Le Tigre. Hanna opened with a striking statement: “First time I heard your voice,” she said, “I went and bought everything of yours – trying to imitate you but find my own style.” Despite being two singers known for very different genres – they’re icons of 1960s teen pop, and riot grrl and feminist dance-punk, respectively – Gore and Hanna do have strikingly similar singing voices. In her 1960s recordings, Gore’s voice sounds distinctly girlish: young, high, sometimes even a bit whiny; the sound of dissatisfied teen angst. Hanna’s voice has many of the same qualities; she uses similar, nasal-sounding timbres and dissatisfied inflections, repurposing and remixing a sound of 1960s girlhood to tell convey feminist, activist messages.

Gore passed away last week at the age of 68, and profiles and obituaries have explored the connections between her music-making and her activism, how she was both a teen pop sensation and a feminist icon. Gore’s musical career began rather suddenly in 1963. She has said that her parents thought they were just humoring her when they let her go into the studio to record her first single, and never imagined that “It’s My Party” – produced by none other than Quincy Jones – would top the Billboard pop charts. After that surprise hit came “You Don’t Own Me,” an anthem of self-determinacy that’s been a touchstone through feminism’s second and third waves and has been covered by artists from Joan Jett to Amy Winehouse. After her 1960s hits, Gore continued working in music. In 1980 she wrote the Oscar-nominated song “Out Here on My Own” for the film Fame, and in 2005 independently released her album Ever Since. Gore was also an advocate for LGBT rights. She spoke openly about being a lesbian, and hosted PBS’s LGBT news program In the Life. When I revisited the 2005 conversation between Gore and Hanna, I was struck by how Lesley Gore’s relationship to feminism is not only something we can witness in her actions, activism, and musical repertoire, but is also something we can hear in the very sound of her singing voice.

The landscape of mid-twentieth century pop featured a spectrum of different young women’s vocal sounds and timbres that have gone on to become sonic symbols of girlhood. These singers’ voices often exposed and critiqued narrowly defined notions of what it meant to be a respectable young woman. The doo-wop influenced sound of groups like the Shirelles, the Bobbettes, the Marvelettes, and others mimicked schoolyard conversations among girls. As scholars including Susan Douglas, Kyra Gaunt, and Jacqueline Warwick have argued, these groups’ songs not only envoiced the tension of growing up but also spoke to how race and class shaped different experiences of girlhood. Other young women, such as Aretha Franklin and Joan Baez, lent their voices to political struggles like the Civil Rights movement. For her part, Gore’s performances were rife with contradiction; she looked every bit the clean cut, middle-class good girl (and, in fact, subsequently spoke of the difficulty of shedding that image). Despite her image, though, in a 1963 headline, the New Musical Express proclaimed her “Lesley Gore: The Singing Rebel.” In Lesley Gore’s voice was an undercurrent of rebellion.

On the surface, “It’s My Party,” which tells the story of a girl snubbed by her boyfriend at her birthday party, is pure teen melodrama. Gore’s voice sounds almost stereotypically girly throughout: high and light, the sound of someone young. Its choruses, though, also give a hint of what it was about Lesley Gore that seemed rebellious. Gore’s character is unwilling to relinquish her unhappiness; she repeats “I’ll cry if I want to!” over and over again, and each time she repeats the line, especially in the final chorus, where she adds yelping ornaments and melisma, a sense of tension and dissatisfaction grows. The song emphasizes the vowel sound in “cry” – a pointed, sharp-sounding vowel that sticks out and doesn’t sound pretty. In “It’s My Party,” Gore plays the role of a girl who isn’t shy about registering her complaints, even if that kind of self-expression isn’t considered appropriate for young women.

In “You Don’t Own Me,” the sense of rebellion is more encompassing. Again, the song emphasizes vowels that are hard to sing subtly – the “ay” sound in “Don’t tell me what to say,” for instance, sounds pointed and irrepressible. Gore’s diction is loaded with attitude. She attacks her consonants in “Don’t tell me what to do, don’t tell me what to say,” and at the song’s climax – “I’m young, and I love to be young” – she almost speaks the words, spitting them out. She uses contrasting timbres: a hushed, deadly serious vocal quality in the verses, and a strident, forceful one in the choruses. “You Don’t Own Me” communicates dissatisfaction with the status quo not only through its words, but through Gore’s vocal delivery.

Gore’s 1960s image – that of a clean-cut goody two shoes – seems at odds with the content of a song like “You Don’t Own Me,” and for all of the rebellion that one can hear in her voice, she never goes over the top, never takes it into anger and rage. Gore embodied white, middle-class respectability, even while a song like “You Don’t Own Me” expressed desire for a different kind of freedom. It was her appearance of respectability that let her sing such songs without fear of public reprisal. Gore’s sound communicates dissatisfaction, but does so within certain limits. Some might argue that her image, and the fact that she had very little control over her recording career in the 1960s, undermine the message of a song like “You Don’t Own Me.” However, I see her performances as articulating the tensions that young women experienced – and still experience. Girls may crave freedom and self-definition, but still feel enormous pressure to be a certain way and to fit into certain categories.

Since the 1960s, singers have channeled the stereotypically girly-sounding voices of Gore and her 1960s contemporaries, transforming a sound that protests implicitly into a sound that protests explicitly. I can hear the voice of the dissatisfied girl the sound of 1970s punk groups like the Raincoats, the Slits, and the X-Ray Spex. In the X-Ray Spex’s most well-known track, “Oh Bondage! Up Yours!” lead singer Poly Styrene opens with a meek, girlish whisper before switching to a strident, demanding shout. Like “You Don’t Own Me,” the song is about self-determination, and in Styrene’s signature screams, I can hear echoes of Gore’s piercing, uncompromising voice. When Kathleen Hanna sang “Rebel Girl” in the 1990s, or, more recently, “Girls Like Us,” with her current band The Julie Ruin, or when Sleater-Kinney’s Carrie Brownstein sings “Modern Girl,” the nasal quality of their timbres, and forcefulness of their diction convey the same persistence and attitude as Gore’s voice. These are re-appropriations of a sound of girlhood. They point out the shortcomings of the narrow roles available to young women, but they also draw on the sonic language of dissatisfaction that singers like Gore pioneered.

Image credits: (1) A record album on a turntable by Bygone. CC 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Front cover for the 7″ single You Don’t Own Me by the artist Lesley Gore, Mercury Records, via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Rebel Girl: Lesley Gore’s voice appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers