Oxford University Press's Blog, page 692

March 5, 2015

Starfruit and running dogs: celebrating the Lantern Festival with Chinese word games

Even though much of the world has adopted the Gregorian calendar, which is based on movement of the sun, many traditional cultures still observe lunar calendars, which are based on movement of the moon. The beginning of the Chinese lunar year this time fell on 19 February of the Gregorian calendar. Fifteen days later, at the first full moon of the lunar year (on 5 March this year), people celebrate the Lantern Festival, a literal translation of ‘dēnghùi’ 灯会 or ‘dēngjié’ 灯节 in Chinese.

In Chinese culture, there is also the tradition of grouping years in cycles of twelve, associating each year in the cycle with an animal in following order: mouse, cow, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, sheep, monkey, chicken, dog, and pig. So a girl born this lunar year would ‘belong’ to the Year of the Sheep; in Chinese, she would ‘shŭ yáng’ 属羊 (literally translated: ‘belong sheep.’) Chinese is a tone language, so the diacritics in ‘ŭ’ and in ‘á’ in these two words indicate the tones that must be used in the pronunciation of these vowels. And later, if she goes to school and meets a schoolmate who belongs to the Year of Dragon, she would know she is three years younger than her new friend.

Alongside the various traditions for categorizing periods of time, most cultures also have games that people play with their language. In the English-speaking world, playing Scrabble, doing crossword puzzles, and speaking in Pig Latin are some of the more common language games. The Lantern Festival is a special time in Greater China when people enjoy language games, often with the puzzle written on colorful lanterns. Each puzzle is usually restricted to a category, to make the guessing manageable (similar to the game of charades, where the player has to announce whether the target is a book, song, or movie.)

“Chinese Zodiac Mosaic” by Tom Magliery. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

“Chinese Zodiac Mosaic” by Tom Magliery. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.Here is an example of a Chinese puzzle, where the category is ‘fruit’. It consists of a string of animal names, in the same order as the aforementioned yearly cycle: mouse, cow, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, monkey, chicken, dog, and pig. The challenge is to come up with the name of a fruit that the puzzle is pointing to. The first thing to notice is that ‘sheep’ is missing from the list; it should follow ‘horse’ and precede ‘monkey.’ As we learned earlier, the Chinese word for ‘sheep’ is the monosyllable ‘yáng’.

Monosyllables in Chinese typically can mean many things, all homophonous with each other. In addition to ‘sheep’, the syllable ‘yáng’ can mean, among other things, ‘sun’ 阳, ‘ocean’ 洋, and ‘poplar tree’ 杨. There is also a fruit that thrives in Southeast Asia, which is called ‘starfruit’ in English. In Chinese, this fruit is called ‘yángtáo’, corresponding either to ‘poplar fruit’ 杨桃or to ‘ocean fruit’ 洋桃, depending on the Chinese dialect. The ‘táo’ 桃here is a noun that is used in the name of several types of fruit.

Again, ‘táo’ is a syllable with many possible meanings. Alongside ‘fruit’ 桃it can also mean ‘porcelain’ 陶, and ‘to escape’ 逃. Therefore, ‘yángtáo’ is the right answer to the puzzle since it means literally ‘the sheep escaped’ 羊逃 from the list, while homophonously 杨桃 also satisfies the specified category of ‘fruit’. Solving such puzzles teases the mind and evokes endless laughter at Lantern Festivals.

Here is another example, based on similar structure as ‘yángtáo.’ The answer is not so clear-cut, but it has greater sociopolitical interest. The puzzle this time is: mouse, cow, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, sheep, monkey, chicken, and pig. The reader will notice that the animal missing this time is ‘dog’, which is ‘gŏu’ 狗in Chinese. A possible answer here would be the noun ‘zóugŏu’ 走狗, or ‘running dog’, where the ‘zóu’ 走is a verb meaning ‘to run’. This phrase was used frequently during World War II when large parts of China were occupied by Japanese soldiers. It referred to those traitors or ‘collaborators’ in China who served the invading Japanese against the interests of their own country. In any case, puzzles such as these can have different answers, and the one which is best matched to the context will be the most successful.

The Lantern Festival traces back to Buddhist traditions, some two thousand years ago. In addition to the gorgeous lanterns that are prominently displayed, many adorned with exquisite paintings and calligraphy, it is also celebrated by special ethnic dances and foods. In fact, the festival is also called ‘yuánxiāo’ 元宵, which refers to the delicious balls made from glutinous rice flour, often served in hot water with sweet fillings. Even as I write these lines, the holiday spirit of the Lantern Festival is permeating Chinese communities all over the world, devouring the yuánxiāo and each offering their favorite puzzles.

Headline image: “Festival of Lanterns 4″ by Laurence & Annie. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Starfruit and running dogs: celebrating the Lantern Festival with Chinese word games appeared first on OUPblog.

Revisiting process recordings using videos

I believe that video technology can improve how we as social work instructors provide feedback to students on their clinical skills, enhancing previous teaching methods that relied on more traditional process recordings. Over the years, there has been much debate over the use of process recordings of client interviews as a learning tool in social work education; some instructors have found the practice outdated. Process recordings require students to painstakingly write down their conversations with clients, to the best of their abilities, aware that what they remember may be, in part, a construction of what was actually said. While process recordings can be effective in teaching students the art of practice, the use of self, critical-thinking skills, and the integration of theory and practice, they are being used less and less in teaching and supervision today. This may be because of students’ complaints that they are time-intensive.

What if there were a way to capture the essence of process recordings, but in a way that’s more in tune with the contemporary student and university? Modern video technology can here come to our aid as instructors and save on the labor of students writing copious notes of client interviews. The use of such technology may also be a better means to achieve objectives and improve student outcomes. With the advent of free software on students’ tablets, smartphones, and cameras, it becomes easy for students to video-record each other in mock client role-plays and then show these role-plays in the classroom. This provides a forum for instructors and students to discuss, reflect on, and critically analyze the clinical process and provide meaningful feedback to each other. These mock interviews allow students to demonstrate what actually occurred in simulated client-worker interactions rather than re-create their recollections of what took place. Providing feedback to students based on their written process recordings is limited by what the student chooses to portray or remembers about the encounter. In contrast, videos provide us with a moment-to-moment replay of the client-worker interaction.

Although process recordings are often reviewed only by a supervisor (or instructor) and the student, videos can be shared more widely. As a result, using videos of student work in the classroom opens up many more possibilities for learning. This kind of sharing between students can stimulate more discussion, greater feedback, and critical thinking. Students can reflect and share their thoughts on what is happening, encouraging multiple perspectives and ways of looking at the interventions. Instructors and other students get to see, listen to and really get a feel for the encounter between the client and worker on a visceral level by watching the video and participating in discussions and experiential exercises related to the interview. The video can be stopped at any time to explore the meaning of a particular moment or question an intervention that occurred. The instructor can pose questions: What would happen if another student chose a different intervention, line of inquiry, or paid attention to something else in the interview? These ideas can then be acted out in a role-play by students or the instructor at that moment in the classroom to observe what happens. There are limitless avenues for teaching and learning using such videos in the classroom.

Flip Camera Display by Phil Roeder. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Flip Camera Display by Phil Roeder. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Another significant advantage of videos over process recordings is the ability to observe both verbal and non-verbal communication in the interview, providing students with a richer picture of the interaction. Teaching students to pay attention to process in an interview involves attending to the relationship – the rapport the client and worker have with each other and how well the worker picks up on the client’s feelings. This is hard to ascertain when reading the somewhat dry text of a process recording. Watching a video provides significantly more clues into the quality of the worker-client relationship. One can observe the client’s affect and whether it has changed during the session. Is there a natural flow, a give and take, to the conversation? Is the client showing signs of resistance, or reacting to something the worker has said? How well is the worker connecting to the client and tuning in to the client’s feelings? Does the client seem far away, distracted, or fully engaged with the worker? Are there moments of silence and what do they mean? What can be learned from body language and tone of voice?

I started using student videos, as well as other video-recorded mock interviews I had produced, in the classroom 15 years ago. Although students were a little self-conscious when the concept was first introduced, they often let go of their worries in the context of a classroom environment that emphasized constructive feedback and learning rather than hard judgment of each other. They were given license to make mistakes, understanding that this was an expected part of their path as students. Also teaching from a social constructivist perspective, I explained that there was no one right way of practicing and how looking at and weighing all the possibilities improved our understanding of clients and clinical interventions.

Once they’d gotten the hang of it, students were engaged and the classroom became a forum for animated case discussions. Instructors and students together questioned whether a particular intervention was effective or whether another approach would have been more successful. Students reflected on what they said and how the client responded and whether they could have approached the situation differently. They examined what theory or practice concept informed their interventions and engaged in active critical thinking and self-reflection. By “going live” with their videos in the classroom, students could identify and demonstrate the practice and interviewing skills they used to other students and ask for feedback on their actual clinical work.

Social workers today are being held more accountable, asked to explain the effectiveness of their interventions with clients and evaluate their practices. Much goes on behind closed doors, and there is a growing interest in demystifying the work that happens in the privacy of the clinician’s office. Video recordings can provide some of this transparency. They are a way for workers to identify theories and practice approaches used with clients, and communicate what led to successful treatment. This gives more confidence to outside funders and third-party payers that we can articulate and evaluate our work. We can demonstrate how our interactions with clients are based on a body of knowledge that is well established, has undergone the rigors of scientific research, and is cited in professional journals. In this sense, social work is moving toward relying more heavily on evidence-based practice.

We can talk about what we do with clients, and espouse the theories we think we use in practice, but it is quite another experience to dissect what is really taking place. I believe using video-recorded interviews to teach about social work theory and practice is an incredibly effective way to engage students in the classroom, evaluate progress, and measure student competencies. By revisiting process recordings and holding on to what was valuable, we can bring them to a new level using the technology that is readily available today.

The post Revisiting process recordings using videos appeared first on OUPblog.

What to do with a million (billion) genomes? Share them

A Practical Genomics Revolution is rolling out, owing to the dropping cost of DNA sequencing technology, accelerated DNA research, and the benefits of applying genetic knowledge in everyday life.

We now have ‘million-ome’ genome sequencing projects and talk of ‘billion-omes’ is growing audible.

Given the expense – even at only $1000 a genome, a million still costs $1 billion US dollars — it is only right to ask, “What will the impact be?”

Just as with the three billion dollar Human Genome Project, the primary purpose of these projects is to improve human health. Current priority areas are cancer, rare genetic diseases, welfare of US veterans, and improving quality of life into old age. Admirable goals, these projects will play a second role in history.

Society gets more science out of larger numbers of genomes, just as any one individual does. This is because we need to study the variation found among many genomes to understand the exact sequence of any one genome.

The lasting value of these grand projects will be the shift in people’s interest and willingness to participate. Many people are just starting to accept the notion that most of us might one day be sequenced – or at least, the next generation.

Some are backing into the corner, saying they will never be sequenced, and if it becomes necessary (i.e. for medical reasons), they will never share the information beyond a doctor or immediate family members. Others are weighing up options and eyeing the playing field. The pioneering few are racing to get sequenced and those at the bleeding-edge are sharing the results.

George Church submitted the first sample to his Personal Genome Project, an aggressively ‘open data’ project that has now gained currency not only in the US, but in Canada, the UK, and most recently, Austria.

Bastian Greshake submitted the first sample into his revolutionary personal genome sharing platform, openSNP.

The whole playing field changes with ‘more data’ – if we share it.

“What if we had a DNA registry of people willing to donate organs and matches could be located as soon as the need is identified?”

This is the obvious allure of Ancestry.com’s DNA Circles and surname projects like those from Family Tree. Not only do you get your generic human ancestry report, you might find new family as well. You can even become curator for your entire clan. Just like with any social technology, such as fax machines, mobile phones, or Facebook, the real benefits come once there is wide-spread adoption.

The benefits of ‘more’ are equally apparent in the field of forensics. DNA profiles are commonly used to identify bodies lost in natural and manmade disasters. If we had the DNA of everyone, the identity of remains could always be established.

Successful identification requires viable DNA. As in the recent death of students in Mexico, sometimes even DNA in bones and teeth can be destroyed by intense heat. The DNA must also be processed correctly. It is still difficult to process mixed samples from low quantities of tissue and contamination is always a possibility, as in the famous case of the female serial-killer that turned out to be a DNA contaminant found on the cotton-swabs used by investigators. It is also possible to leave no DNA behind, plant false evidence, or as New York artist, Heather Dewey-Hagbord, explores in “DNA-spoofing”, to leave ‘fake DNA’.

Likewise, perpetrators of crimes would be identifiable. Burglars, murderers, child abandoners and rapist would be exposed. The FBI’s DNA database, CODIS, now contains over 300k DNA profiles. In just one of many recent reports, Houston police found 850 DNA matches to existing DNA profiles while clearing their backlog of 6663 rape kits.

How might a universal DNA registry reshape society? In the case of Houston, it would have led to 100% of tests finding matches, instead of only 13%. Even if the costs appear prohibitive, the benefits are clear, if hurdles surrounding privacy and proper use of the data can be cleared.

What if we had a DNA registry of people willing to donate organs and matches could be located as soon as the need is identified?

What if babies born with rare genetic diseases could be sequenced at birth by willing families and compared to a global database? At best, the identification of such cohorts might lead to the development of cures. At a minimum it might shed light onto a bewildering illness and bring some context and comfort to a difficult situation. A diagnosis is better than helplessly watching a child suffer with no idea what is causing the problem.

This is exactly the idea behind MatchMaker Exchange, a way for hospitals to build a global network of millions of genomes to improve patient outcomes.

Some in genomic research object to super-sized studies saying funding should go to smaller cohort studies. The power of this approach is clear. Genetics company, 23andMe, recently earned $55m from selling existing data, largely because it includes a Parkinson’s disease cohort. Such cohort studies provide an essential way to elucidate the workings of genes and pathways, but large-scale studies also open the doors to the possibility of answering questions we don’t know to ask.

The value of building a collective pool of shared genomes is still going up fast because so much is remains unknown about the workings of our DNA and the distribution of the biologically significant variation that makes us all unique. The value proposition of the collection increases with size, but to a limit. We don’t need to sequence endlessly to answer certain questions, only if we want to answer all questions that can be best addressed using DNA.

Certainly, one very special cohort of individuals is arising – those who believe in the benefits of pooling data, the ‘genomic sharers’.

Featured image credit: DNA. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post What to do with a million (billion) genomes? Share them appeared first on OUPblog.

March 4, 2015

Keys and bolts

I received a question whether I was going to write about the word key in the series on our habitat. I didn’t have such an intention, but, since someone is interested in this matter, I’ll gladly change my plans and satisfy the curiosity of our friend. A detailed and highly technical entry on key can be found in my introduction to an etymological dictionary of English, and in this blog, I usually try not to repeat the information given elsewhere in my published works. But in the present case, I have an excuse. My dictionary can be found in many college libraries, but despite the presence of some risky words in its text and the many shadows it casts it is unable to compete (as regards sales and its appeal to the film industry) with Fifty Shades of Grey. Since, presumably, neither our correspondent nor most of our readers have seen the dictionary, I will briefly discuss the history of key as I understand it. Moreover, I will devote a follow-up post to latches. It would be nice to call the forthcoming miniseries “Nuts and Bolts,” but all I can offer is “Keys and Bolts from an Etymological Point of View.”

Key has been known from texts since the year 1000. Yet dictionaries refuse to say anything definite about its distant origin. The reason for specialists’ extreme caution is not far to seek. In most cases, a word for key means “opener” or “closer” (in the remote past, different tools were sometimes used for locking and unlocking the door), but key cannot be associated with any word meaning “open” or “close.” Desperate attempts to derive key from Latin clavis “key” by eliminating l (claudo means “shut, close”) were obviously doomed to failure. However, they did not lose their attraction even in the second half of the nineteenth century. Equally futile were the references to Engl. quay (from French, from Celtic) and to Welsh cau “close; clasp, etc.” Several unpromising hypotheses should not delay us here. A serious complication consists in the fact that key lacks indubitable cognates except kaei “key” in Frisian (the old forms and numerous variants in Frisian dialects have also been recorded), for in the absence of related words it is usually impossible to draw any conclusions in etymology.

Ancient Greek iron keys, Kerameikos Archaeological Museum (Athens). Picture by Giovanni Dall’Orto, 2009, via Wikimedia Commons.

Ancient Greek iron keys, Kerameikos Archaeological Museum (Athens). Picture by Giovanni Dall’Orto, 2009, via Wikimedia Commons.However, one can be fairly certain that the etymon that yielded Engl. key sounded as *kaigjo- (j stands for what would be y in Modern English), and this form excludes many tempting comparisons, because the only solid basis in our search is phonetics. German and Dutch scholars have more than once tried to connect Engl. key and German Kegel “skittle, ninepin,” but the match is unsatisfactory; consequently, this path leads nowhere. Kegel and most other words that have been used in the hope to shed light on the derivation of key have another flaw: their origin is equally debatable and sometimes unknown. I have often referred to the rule of thumb that should be applied to etymology (although it is of my own devising, its strict application guarantees success): never use an obscure word to explain another word whose history is obscure. I am unaware of a single example in which those who juggled with several opaque forms arrived at viable results. Another rule I always use may appear too vague and even unfair, but it too is useful: “The more convoluted an explanation is, the greater the chance that it is wrong.” Several conjectures concerning the etymology of key by eminent researchers are so involved that their uselessness could be predicted.

Now is the time to provide a clue to key. In addition to the noun key, English has the adjective key “twisted,” as in key-legged “knock-kneed, crooked,” at present known only in northern British dialects, and even there sometimes obsolescent. The verb key means “to twist, to bend.” Those regional words seem to have come to English from Scandinavian. In Swedish dialects, kaja “left hand” occurs. It is allied to Danish regional kei “left-hand”; in the Danish Standard, the corresponding adjective is kejtet. Old Icelandic keikja “bend back” belongs here too. The left side is often looked upon as weak and deficient. “Left” interpreted as “bent, twisted, crooked” is a common occurrence.

The most primitive keys, when they were keys rather than bars, had bits. In many languages, the root of the word for “key” means “curvature.” Wattle doors of the ancient speakers of Germanic had openings in the front wall. They were not real doors and did not need elaborate locks. Their function was to keep the cattle from entering some quarters rather than saving the house from burglars. Laws against thieves were severe. I believe that Engl. key, both the noun and the adjective, goes back to the same source and belongs with the Scandinavian words cited above. Key, it appears, designated a stick, a pin, or a peg with a twisted end. It must have been a northern word from the start. The modern pronunciation of key (unpredictably, key rhymes with see, rather than say) may be of northern origin as well.

Before the Scandinavian noun was borrowed, Old English, quite naturally, had a native word for “key.” It was scyttel ~ scyttels, allied to the verb sceotan “to shoot.” Its disappearance may have been due to the noun’s broad range of senses: scyttel also meant “dart, arrow, missile” (that is, anything that could be shot). However, its modern reflex is shuttle! The Old Frisian word was probably likewise a loan from Scandinavian. Perhaps the borrowing happened at the epoch vaguely referred to as Anglo-Frisian. The Old English form of the word key behaved in a strange way; it could be masculine or feminine, and it vacillated between the so-called strong and weak declensions. All this might be the consequence of the fact that key was a guest in the language and people were not quite sure of its grammatical categories. For the sake of historical justice I should add that E. Magnusen almost guessed the source of key as early as 1882, but he was led astray by his idea that key is a congener of akimbo.

Key West postcard shot. Photo by Ed Schipul. CC BY-SA 2.0 via eschipul Flickr.

Key West postcard shot. Photo by Ed Schipul. CC BY-SA 2.0 via eschipul Flickr.If my reconstruction is correct, the word came to English very early, and one wonders why it did not turn up in texts before the year 1000. Possibly, key was first known only in the north and spread to southern dialects much later. Even if both English and Frisian borrowed the word from their northern neighbors, its source in English was hardly Frisian; a Frisian loan would have taken less time to reach Wessex, whose dialect of Old English we know especially well.

But why was the word borrowed? Probably the Scandinavians had keys whose construction differed from those the Angles and Northumbrians used. Here we enter the sphere of “Words and Things,” an indispensable field for the etymologist, but we don’t know enough about the keys of medieval England to offer an intelligent guess. I find my view of key fairly reasonable. So far, it has met with neither approval nor disapproval, but the wheels of etymological lexicography grind slowly, and I have nowhere to hurry.

Key in place names like Key West is an entirely different word. It is an adaptation of Spanish cayo “shoal, rock, etc.”

The post Keys and bolts appeared first on OUPblog.

March 3, 2015

What can we learn from the lives of male feminists?

In the span of one week at the beginning of February, two of the largest cultural events in the United States featured prominent messages about ending violence against women. The NFL gave away coveted air-time to run this ad from the NO MORE campaign. During the Grammys, President Obama encouraged artists to “take a stand” and activist Brooke Axtell shared her story of domestic violence.

These moments have been hailed for drawing public attention to violence against women, a social problem that has long been marginalized. At the same time, they have been called out for being more flash than substance.

But one aspect of these moments received little attention: they put men front and center in campaigns to end violence against women. After all, it was President Obama, who holds an office never occupied by a woman, and the NFL — arguably the bastion of American manhood — who delivered these messages.

That this barely rates as news today is radical. And at the same time, it is old news. Some men have always identified with anti-violence work. Beginning in the 1970s, some went to work on the front lines at feminist anti-violence agencies, others made a name for themselves speaking about violence, and some marched for policy change. They weren’t celebrities—they were men who shared a belief that violence against women mattered and wanted to work to end it.

The lives of these men who established careers and lives doing anti-violence work matter: fathers, football players, actors, gay, straight, trans, black, latino, white, activists, entrepreneurs, twenty-year-olds, and seventy-year-olds. Not because they tell us about some great and rare men, but for what they can show us about the tensions and possibilities of allies fighting, winning, and falling short in movements which aren’t theirs.

Why do some men from diverse backgrounds and values take actions to end violence against women when most men don’t? How do these differences matter in their work? How do allies navigate being put on a pedestal when men’s privilege is at the core of gender inequality? How do they connect with other men when masculinity itself is risky? What keeps them going in work that can seem hopeless or even harmful? What is at stake for these men, and for the ongoing movement to end violence against women? If major public messages are to have any hope of getting beyond the flash, we need to understand.

Image Credit: “A Women’s Liberation march in Washington, D.C., 1970” by Leffler. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What can we learn from the lives of male feminists? appeared first on OUPblog.

Suffragist Lucy Stone in 10 facts

Lucy Stone, a nineteenth-century abolitionist and suffragist, became by the 1850s one of the most famous women in America. She was a brilliant orator, played a leading role in organizing and participating in national women’s rights conventions, served as president of the American Equal Rights Association, co-founded and helped lead the American Woman Suffrage Association, and founded and edited the Woman’s Journal, the most enduring, influential women’s newspaper of its day. Yet history has wrongly slighted her, relegating her to a far less important role than that of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony.

1. Lucy Stone was the first Massachusetts woman — and one of the first women in the nation — to earn a college degree. Because her father refused to support her dream of attending college, she taught school to earn the money she needed to attend Oberlin Collegiate Institute, the only college at the time that admitted women. Stone graduated in 1847 at the age of twenty-nine.

2. After college, Stone chose public lecturing as her career, a most unusual profession for a woman at the time. In 1848, the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society hired her as a lecturer. She soon added women’s rights to her speeches, defending her choice by insisting, “I was a woman first.” By all accounts, she was a passionate orator. Soon Stone was earning a substantial income and attracting hundreds, sometimes even a few thousand people to her talks.

3. Public speakers, especially those professing radical ideas such as abolition and women’s rights, faced enormous opposition almost every time they spoke. On stage, Stone was pelted with rotten vegetables and books. Mobs of angry men attended her lectures and tried to drown her out. One night someone stuck a hose through the stage window where Stone was standing and doused her with icy water. A resolute Stone pulled her shawl tighter and kept on talking.

4. Stone adopted bloomers in the early 1850s. This costume — pantaloons and a knee-length skirt — challenged popular feminine fashion at the time. Stone loved the new outfit and wore it both at home and in public. Crowds were aghast and after three years of criticism, Stone gave up the comfortable costume, though never again did she don corsets and fancy, voluminous dresses.

A portrait of Lucy Stone. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

A portrait of Lucy Stone. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.5. Stone vowed never to marry because laws at that time made women subordinate to their husbands and removed almost all their rights. But in 1855 after a two-year courtship by Henry Browne Blackwell, she changed her mind. He promised to let her live an independent life. Stone was able to continue her lecturing career and to play a leading role in the women’s movement until the birth of daughter Alice in 1857.

6. A year after her wedding, Lucy made the radical decision to keep her maiden name, insisting that since a man could keep his last name, so too could a woman. All her life, she was Lucy Stone.

7. Motherhood had a profound impact on Stone and her suffrage work. A few months after Alice was born, Stone gave up her lecturing career in order to raise her. Stone found hired help inadequate to meet her standards. The death of a son, born two months prematurely, no doubt caused Stone to be overly-attentive in rearing Alice.

8. Throughout the 1850s, Stone and Susan B. Anthony had been close friends and confidants as they campaigned for women’s suffrage. Yet in 1869, they parted ways. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton opposed the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, which gave black men citizenship and the right to vote. Stone supported both amendments. That year Stanton and Anthony, arguing that white women deserved the vote first, founded the National Woman Suffrage Association. Finding it impossible to work with these women, Stone co-founded the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). For twenty-one years the two organizations worked independently of one another as both campaigned for women’s suffrage. For the rest of their lives, Anthony and Stone remained distrustful and critical of one another.

9. In 1870 after the family moved to Boston, Stone cut back on her lecturing and co-founded and edited the Woman’s Journal, hoping to create a quieter life for herself. Publishing this newspaper each week never brought her that calm, but the Woman’s Journal became the most important, longest-lived newspaper of its kind, covering women’s issues and helping to promote women’s rights. The paper played a significant role in energizing the movement and leading to the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920.

10. In one of the most important sources scholars use to study the nineteenth-century women’s rights movement, the History of Woman Suffrage, Lucy Stone is all but absent. Stanton, Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage edited the first two volumes. Lucy was certain it would present a biased, inaccurate account of the movement. She also shunned the limelight, believing the movement was far more important than its leaders. She refused to participate. Thus, Lucy Stone and the AWSA are all but absent in this monumental work — and in our history.

Featured image: Unnamed members of the women’s suffrage movement carry an American flag and a banner promoting a “mass meeting” of suffragists. Public domain via the Library of Congress.

The post Suffragist Lucy Stone in 10 facts appeared first on OUPblog.

An A – Z guide to Nicolas Nabokov

Who was Nicolas Nabokov? The Russian-born American composer had a huge impact on music and culture globally, but his name remains relatively unknown. He had friends and acquaintances in a variety of circles, whether his cousin the writer Vladimir, the poet Auden, or the choreographer Balanchine. He travelled across the world despite the dangers of the Cold War. His compositions ranged from ballets to operas, concertos to symphonies. This A to Z gives an idea of the amazing range of the composer’s life and work.

A — Auden

Nabokov met W.H. Auden during the Second World War and they remained close friends. Auden and his lover Chester Kallman wrote the libretto of Nabokov’s second opera, Love’s Labour’s Lost (1973), after Shakespeare’s comedy.

B — Balanchine

In the words of someone who knew them both, Nabokov and “Mr. B” were “like brothers” ever since they met in 1928, when they were both under Diaghilev’s tutelage. Their main collaboration was the ballet Don Quixote (1965), which remained in the repertory of the New York City Ballet for 13 seasons.

C — CIA

Nabokov “was not the sort of man that CIA security would have been happy about,” to quote as CIA agent who knew him well and collaborated with him. This biography shows exactly why and disposes once and for all of the insinuation that he was a “fixer.”

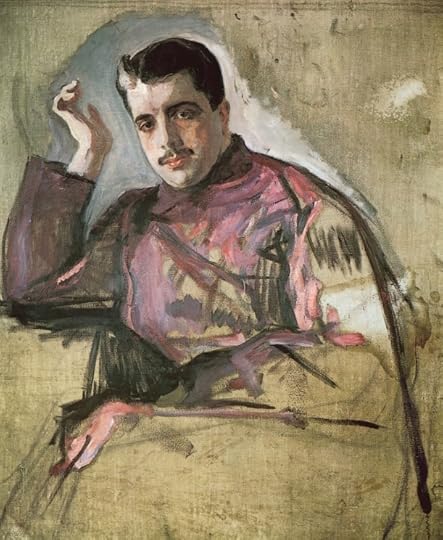

Portrait of Sergei Diaghilev by Valentin Alexandrovich Serov, 1909. ublic somain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Sergei Diaghilev by Valentin Alexandrovich Serov, 1909. ublic somain via Wikimedia Commons.D — Diaghilev

Nabokov was among the last young émigré musicians whose career was launched by the Ballets Russes, which premiered his ballet Ode in 1928. His writings include some of the most perceptive portraits of the great impresario, Sergei Diaghilev.

E — Emigration

Nabokov left Russia with his family in 1919, never to return except for two weeks in 1967 and an even briefer stay the following year. He once referred to émigrés as “the Third Estate of the twentieth century.”

F — Festivals

Some of Nabokov’s greatest achievements were the festivals he organized in the 1950s and 1960s as head of the Congress for Cultural Freedom, in Paris, Rome, Tokyo, and Delhi, and later as cultural adviser to Willy Brandt in Berlin. The 1964 Berlin Festival he organized on the contribution of blacks to world culture is now considered a landmark in this respect.

G — Germany

Like many upper-class Russians, Nabokov had German roots on both sides. A fluent German speaker, he felt at home in Berlin more than in any other major city. “My good German blood saves me,” he used to say.

H — Hindemith

An admirer of the German composer, whom he met in the late 1920s, Nabokov was instrumental in facilitating Paul Hindemith’s move to the United States in the late 1930s after he ran afoul of the Nazi regime.

I — India

When Nabokov discovered India in the 1950s, it became for him “the land of wonders.” A profound admirer of Indian classical music and dance, he played a major role in getting them better known in the West. With the French Indianist Alain Daniélou, he helped create an Institute for Comparative Music Studies in Berlin in 1963.

J — Japan

One of Nabokov’s pioneering festivals was the East-West music encounter he organized in Tokyo in 1961. One of the sensations of this event was the first appearance of the Kathakali dance theater outside Kerala.

Serge Koussevitzky at Carnegie Hall, 1947. Library of Congress.

Serge Koussevitzky at Carnegie Hall, 1947. Library of Congress.K — Koussevitzky

As conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Serge Koussevitzky conducted the American premiere of Nabokov’s First Symphony with considerable success in 1930. After the war he premiered Nabokov’s cantata The Return of Pushkin (1948), while Charles Münch conducted the first performance of the oratorio La vita nuova (1951), also with the BSO.

L — Leontyne Price

Nabokov was instrumental in launching the career of the great African-American soprano when he insisted that Leontyne Price appear in the main role in Virgil Thomson’s opera Four Saints in Three Acts when it was staged in Paris in 1952 as part of his Masterpieces of the Twentieth Century festival. She and he remained lifelong friends.

M — Maritain

A deeply spiritual man, though he came to distance himself from any established religion, Nabokov was close to the Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain and his wife Raïssa, who befriended him in the mid 1920s.

N — Nabokov

Nabokov was justifiably proud to belong to one of the great liberal families of pre-Revolutionary Russia. As Alexander II’s justice minister, his grandfather had given the country one of the most enlightened judicial systems in Europe. Nabokov became particularly close to his uncle Vladimir, one of the leaders of the liberal opposition to the Czar (and father of the novelist), until he was assassinated by a monarchist in Berlin in 1922.

O — Ormandy

The Hungarian-American conductor and the Philadelphia Orchestra gave the world premiere of Nabokov’s Cello Concerto in 1953 and his tone poem Studies in Solitude in 1961. Eugene Ormandy also conducted the American premiere of the Cello Variations he wrote for Mstislav Rostropovich in 1968.

P — Prokofiev

Nabokov became a friend of Sergei Prokofiev and his wife Lina in the late 1920s and subsequently wrote eloquently about the persecution suffered by the Russian composer under Stalin.

Q — Quartet

Nabokov wrote one string quartet in 1937. Subtitled Serenata estiva, it was premiered by the Budapest String Quartet, thanks to a grant from Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, at St John’s College, Annapolis, where Nabokov was then teaching, in 1941.

R — Russia

Though he left his native country at the age of 16 and spent the next 59 years of his life in exile, Nabokov always felt profoundly Russian, both as a human being and as a musician.

Igor Stravinsky, Russian composer. Library of Congress.

Igor Stravinsky, Russian composer. Library of Congress.S — Stravinsky

Nabokov was introduced to Igor Stravinsky in 1927 and became of the great promoters of his music. They were especially close in the last three decades of Stravinsky’s life.

T — Tchaikovsky

Growing up at a time when Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky music was frowned upon by the Western musical avant-garde, Nabokov, for whom lyricism was paramount, always considered Tchaikovsky the greatest of all Russian composers. He was a particular admirer of his ballets.

U — United States

Nabokov emigrated to the United States in 1933, becoming a US citizen in 1939, and making New York his permanent home. Between 1945 and 1947 he served with the American forces in Germany, helping both with the denazification and the reconstitution of musical life in the country.

V — Vladimir

Nabokov was the first cousin of Vladimir Nabokov, the author of Lolita. While Vladimir lived in Berlin, he entertained him in Paris and in Alsace, and in the late 1930s helped him to resettle in the United States. Despite Vladimir’s professed aversion to music, they even collaborated in 1947 on Nabokov’s setting of a poem by Pushkin.

W — Wells College

From 1936 until 1941, Nabokov, who had no prior teaching experience, was professor of music at Wells College in Aurora, NY. There he hosted Copland, Hindemith, and his cousin Vladimir, staged plays with incidental music of his composition, and completely reorganized the musical life of the college.

X — Xenakis

Though Nabokov, as a composer, remained essentially tonal, as a cultural force he was an ardent supporter of all musical trends, and Iannis Xenakis, the Greek-born French composer, was among the younger musicians he promoted.

Y — Yusupov

Rasputin’s End, on a libretto by Stephen Spender and the composer, was Nabokov’s first opera. Premiered in a short version in Louisville in 1958, it was staged in its definitive version at Cologne in 1959, with a cast that included the young Shirley Verrett. In the opera, Prince Felix Yusupov is simply called “The prince.”

Z — Zhdanov

Andrei Aleksandrovich Zhdanov is a Soviet politician who enforced socialist realism in the arts and a Bolshevik historiography. Cultural freedom was not a mere slogan for Nabokov. A member of a circle that included well-informed diplomats such as Chip Bohlen and George Kennan, he never harbored any illusions on the nature of the Soviet regime. In his writings and, later, as head of a non-governmental cultural organization, he felt strongly about the need to protect intellectual and artists from political intimidation and persecution.

Headline Image: Ballet. CC0 via Pixabay

The post An A – Z guide to Nicolas Nabokov appeared first on OUPblog.

Does philosophy matter?

Philosophers love to complain about bad reasoning. How can those other people commit such silly fallacies? Don’t they see how arbitrary and inconsistent their positions are? Aren’t the counter examples obvious? After complaining, philosophers often turn to humor. Can you believe what they said! Ha, ha, ha. Let’s make fun of those stupid people.

I also enjoy complaining and joking, but I worry that this widespread tendency among philosophers puts us out of touch with the rest of society, including academics in other fields. It puts us out of touch partly because they cannot touch us: we cannot learn from others if we see them as unworthy of careful attention and charitable interpretation. This tendency also puts us out of touch with society because we cannot touch them: they will not listen to us if we openly show contempt for them.

One sign of this contempt is the refusal of most philosophers even to try to express their views clearly and concisely enough for readers without extraordinary patience and training. Another sign is that many top departments today view colleagues with suspicion when they choose to write accessible books instead of technical journal articles. Philosophers often risk their professional reputations when they appear on television or write for newspapers or magazines. How can they be serious about philosophy if they are willing to water down their views that much? Are they getting soft?

As a result, philosophers talk only to their own kind and not even to all philosophers. Analytic philosophers complain that continental philosophers are unintelligible. Continental philosophers reply that analytic philosophers pick nits. Both charges contain quite a bit of truth. And how can we expect non-philosophers to understand philosophers if philosophers cannot even understand each other?

Of course, there is a place for professional discourse. Other academic fields from physics to neuroscience also contain tons of technical terms. Professional science journals are rarely enjoyable to read. The difference is that these other fields often work hard to communicate their ideas to outsiders in other venues, whereas most leading philosophers make no such effort. As a result, the general public often sees philosophy as an obscure game that is no fun to play. If philosophers do not find some way to communicate the importance of philosophy, we should not be surprised when nobody else understands why philosophy is important.

This misunderstanding is sad, because philosophy deals with important issues that affect real people. Metaphysicians propose views on free will and causation that could change the way law ascribes responsibility for crimes or limits access to pornography on the grounds that it causes violence to women. Political philosophers defend theories with useful lessons for governments. Philosophers of science raise questions about the objectivity of science that could affect public confidence in evolution or climate change. Philosophers of religion and of human nature present arguments that bear on our place in the universe and nature. Philosophers of language help us understand how we can understand each other when we talk. And, of course, ethicists talk about what is morally wrong or right, good or bad, in situations that we all face and care about.

Because of these potential applications, there must be some way for philosophers to show why and how philosophy is important and to do so clearly and concisely enough that non-philosophers can come to appreciate the value of philosophy. There also must be some way to write philosophy in a lively and engaging fashion, so that the general public will want to read it. A few philosophers already do this. Their examples show that others could do it, but not enough philosophers follow their models. The profession needs to enable and encourage more philosophers to reach beyond the profession.

Feature Image Credit: Dawn Sun Mountain Landscape by danfador. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Does philosophy matter? appeared first on OUPblog.

March 2, 2015

Four questions for Boehner, Bibi, Barack, and Biden

Tomorrow night’s appearance before a joint session of Congress by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin (“Bibi”) Netanyahu raises four important questions:

1. Should Speaker John Boehner have invited the Israeli Prime Minister to speak without consulting with President Obama first?

No. As a matter of law, the Speaker had the authority to extend this invitation to the Israeli Prime Minister without consulting with the President. As a matter of policy, however, this was a bad practice.

The Constitution assigns to each branch of government distinct responsibilities in the conduct of foreign affairs. The President negotiates treaties but the Senate must advise and consent by a two-thirds vote to any treaty negotiated by the President. The Senate also confirms the President’s appointees to head the State Department and the other major national security agencies. Budgetary outlays, including foreign aid and military expenditures, must be approved by the Senate and the House of Representatives.

The President has the constitutional authority to “receive Ambassadors and other public Ministers.” By virtue of this constitutional authority, as well as the President’s power to negotiate treaties for submission to the Senate and his general “executive Power” under the Constitution, the day-to-day, face-to-face diplomacy of the United States is the province of the president. The Speaker’s invitation, extended to a foreign head of government without consultation with President Obama, diminished that authority. A Republican president will some day rue this precedent.

2. Should Prime Minister Netanyahu have accepted Speaker Boehner’s invitation?

No. By accepting the invitation, the Prime Minister unwisely projected himself into U.S. politics in an unacceptable fashion. As the overseas funds flowing into the Clinton Foundation demonstrate, foreign governments and foreign interests continually attempt to influence domestic U.S. opinion and politics. One of the underappreciated facts of American political life is the extent to which the lobbying dollars flowing into Washington come from foreign sources.

Moreover, initial reporting by the New York Times proved inaccurate. Mr. Netanyahu accepted the Speaker’s invitation only after the President had been informed of it. Nevertheless, the Prime Minister’s acceptance of the Speaker’s invitation crossed a line that should not have been crossed. There is a particular salience to a joint appearance before Congress.

3. Given the Speaker’s invitation and the Prime Minister’s acceptance of that invitation, was the President’s refusal to meet with the Prime Minister appropriate?

No. Speaker Boehner’s invitation, extended without first consulting with the President, diminished the Presidency. Mr. Obama’s snubbing of the Israeli Prime Minister diminished the Presidency further. A gracious response by President Obama would have looked strong. The President’s peevish refusal to meet with Mr. Netanyahu, as well as the President’s continuing efforts to degrade Mr. Netanyahu, have done just the opposite.

4. Should the Vice-President, in his constitutional capacity as “President of the Senate,” boycott the Prime Minister’s speech to Congress tomorrow night?

No. Mr. Biden, a steadfast supporter of the Jewish state, should instead announce that he will, in his constitutional capacity, preside over the Senate on this occasion – even as he could legitimately express his reservations about the precedent being set. Such a response would help channel the public debate where it should go: the merits of the criticism of the Obama Administration’s approach to the negotiations with Iran.

As a matter of substance, Prime Minister Netanyahu is right to be skeptical of the course being pursued by President Obama and Secretary of State John Kerry. The President and Secretary of State appear determined to reach an agreement with Iran, even if it is a bad agreement. President Obama seems to have decided to sign an executive agreement with Iran without submitting a treaty to the Senate. The President’s refusal to utilize the constitutional treaty-making process suggests that he is committed to an agreement with Iran that cannot muster the two-thirds support of the Senate.

Mr. Netanyahu’s reservations about the President’s course in the negotiations with Iran is shared by many serious commentators on foreign affairs. These skeptics include Senator Bob Menendez, the ranking Democrat on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, and Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel. If, as seems likely, President Obama continues in his insistence that he can unilaterally make a deal with Iran, that course will confirm the idea that President Obama and Secretary Kerry prefer to make a bad deal with Iran for the sake of making a deal.

Image Credit: “05-24-11 at 10-33-24″ by Speaker John Boehner. CC by NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Four questions for Boehner, Bibi, Barack, and Biden appeared first on OUPblog.

Let’s finally kick the habit: governance of addictions in Europe

More than a century ago, on 23 January 1912, the first international convention on drug control was signed in The Hague. A century later, despite efforts made at all levels and vast quantities of evidence, our societies still struggle to deal effectively with addictive substances and behaviours. Reaching a global consensus has proved harder than kicking the worst drug-taking habit.

Nonetheless, the meeting of the Global Commission on Drug Policy held on 9 September 2014 in New York might be a turning point. During the meeting, a ground-breaking report entitled “Taking Control: Pathways to Drug Policies that Work” was presented. The report calls for an end to criminalization policies, and lays the foundation for a health-oriented approach to tackling drugs.

With the support of evidence-based studies on drugs and addiction, the commission report places the well-being of society at the centre of the debate, a trend that many European countries are already pursuing. Based on a recent study of the models for managing addictions in Europe, it is clear that European nations are increasingly decriminalizing drug use and possession, while implementing harm reduction policies. Intriguingly, these two measures tend to go hand in hand, and most countries with innovative harm reduction policies — such as providing injection rooms for addicts — have also decriminalized the use and possession of illicit drugs.

Although the Global Commission on Drug Policy only takes illicit drugs into account, it is worth mentioning developments in the regulation of legal drugs (alcohol and tobacco) in Europe. This regulative perspective includes evidence-based measures related to marketing, packaging, production, distribution, age limits, taxes, and advertising. In Europe, it can be seen how those countries with strict regulations on alcohol and tobacco have been able to reduce the consumption and the associated harm.

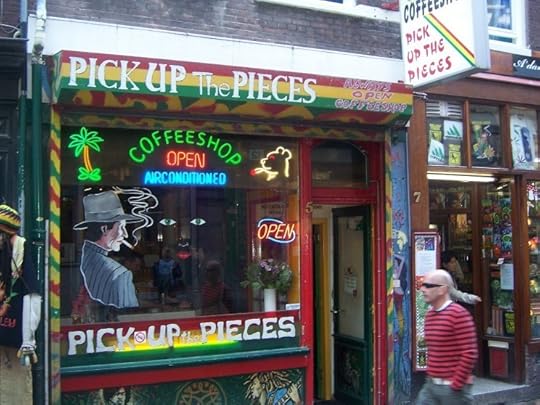

Cannabis coffee shop in the city center of Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Cannabis coffee shop in the city center of Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Public Domain via Wikimedia CommonsUnfortunately, no European country has yet embraced a decriminalization and harm reduction approach accompanied with a regulative perspective on legal substances. Such a comprehensive approach would fully enhance the well-being of everybody. Historical paths and long-term problems with specific substances exert an unfortunate influence on policy-makers: who tend to focus either on legal or illicit substances. Nonetheless, it is time to overcome these taboos and provide comprehensive approaches that include the three main policy trends for tackling addiction: decriminalization, harm reduction, and regulation.

The effects of history and geopolitics entail that many European countries still concentrate efforts on security and implement policies that criminalize people with drug-addiction problems. These countries focus on reducing the supply of illicit substances, and pay less attention to the demand side, which can be tackled by decriminalizing drugs, boosting harm reduction measures, and strengthening the prevention and treatment of addiction. Nonetheless, the European Union is shaping the policies of the countries that criminalize addictions problems and these member states are increasingly taking into account the well-being of society in their policy-making process. The next step, and the most difficult one, is to translate the good intentions that these countries are starting to introduce in their strategies into real actions.

The report published by the Global Commission on Drug Policy is good news and an important step towards a new model that places the well-being of society at the centre of the debate on addictions. However, governments must not underestimate the difficulties involved in translating this discourse into reality. As has been seen in Europe, most nations with health-oriented approaches also enjoy the support and involvement of regional governments, as well as businesses and charities. The involvement of key stakeholders is critical in the decision-making, implementation, and evaluation processes.

Governments can no longer act unilaterally; instead, to kick the drug-taking habit they must encourage the participation of stakeholders, because without their support it will be impossible to achieve a policy shift towards the well-being of society. In this decentralized and multi-level organizational structure, the public sector should have a leading role in determining the strategy of the public policy for addictions. Although the public sector has to encourage the participation of stakeholders, it has to avoid co-optation by both industry and NGOs. In short, the complexity of addiction requires a comprehensive solution, with multiple layers and actors involved. Despite these complexities, there is an increasing agreement between European countries and the international community on the ultimate goal of the governance of addictions: replace the war on drugs by the well-being of society.

Featured image: The Parliament’s hemicycle (debating chamber) during a plenary session in Strasbourg by Diliff. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Let’s finally kick the habit: governance of addictions in Europe appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers