Oxford University Press's Blog, page 688

March 15, 2015

The visual, experiential, and research dimensions of police coercion

Over the past year the number of questionable police use-of-force incidents has been ever present. The deaths of Eric Garner in New York, Michael Brown in Missouri, and 12-year-old Tamir Rice in Ohio, are but just a few tragic cases.

Thanks to technological advances (e.g. cell phone videos, police dashboard and body-worn cameras), police-citizen encounters are increasingly captured in video format. If the old adage is that “a picture tells a thousand words” then how many words does a video tell? Minimally, a video offers quite a bit in terms of seeing how varying police-suspect encounters actually unfold, as opposed to the version provided by police officers in their written reports or those offered by interested bystanders witnessing the event. In addition, a video can be streamed to millions within an instant, thereby opening up the process for many people to see as opposed to a select few, such as police departmental officials.

This isn’t to suggest that the use of video is without limitations. For one, the general citizenry may come to a rush to judgment, despite little knowledge as to what appropriate force entails legally. Further, a video may be shot from a single or limited angle, or fail to capture preceding events, thereby presenting a distorted image of the incident. Nonetheless, on the whole, the use of video brings light to police actions with at least the hope of greater accountability, which is good. Moreover, the growing documentation of video evidence tells those who live outside distressed urban America neighborhoods – where race and class often intersect – what those who live inside such neighborhoods have been saying for the better part of American history: the police abuse their power and those in highly “concentrated disadvantaged” areas share a disproportionate burden.

While empirical evidence can be found in support, and in dispute, of race and class differences in regard to police coercion, unless one is deliberately biased or simply ignorant, it is difficult to dispute that such correlates play at least some role when it comes to coercive police authority. There is too much research showing that race and class matter. Research conducted in multiple cities shows that males, non-whites, poorer, and younger citizens are treated more coercively by the police. Further, neighborhood context is an important predictor of police use of force. More specifically, controlling for a host of situational factors (e.g. suspect resistance, presence of a weapon) and officer-based determinants (e.g. age, education, and training), police officers are significantly more likely to use higher levels of force when suspects are encountered in disadvantaged neighborhoods (i.e. higher levels of poverty and unemployment, a greater proportion of female-headed households, and a higher proportion of minority residents).

Research also shows that police agencies rarely sustain citizen complaints of excessive force or discipline accused officers, and that officers who adhere more strongly to depictions of a traditional police culture (e.g., an “Us versus Them” ideology toward the public, greater suspicion toward citizens, belief structure that the police should always “maintain the edge”) are more coercive toward citizens. It is no wonder police trust and legitimacy have come under intense scrutiny.

Thus, is police misuse of force an issue that deserves and even demands a greater emphasis and call to action from politicians, criminal justice agencies, and the public citizenry? Absolutely. But I would also urge a considerable degree of caution on several fronts before overstating the problem and subsequently recommending changes to something that may not be as “broken” as may appear.

First, rarely are “proper” use-of-force incidents captured on video and broadcast to the world in a similar fashion to incidents involving more questionable behavior. There are countless incidents handled on a daily basis by nearly 900,000 sworn police officers across nearly 18,000 police agencies throughout the USA that are simply not questionable. They don’t make the nightly news. They don’t go viral on YouTube. They don’t become fodder for neighborhood association meetings. In other words, one has to be careful not to overgeneralize based on just the bad cases we see.

Second, there are an untold and undocumented number of police-citizen encounters daily whereby police officers are able to resolve a potentially contentious incident without having to use any physical or weapon-based force. Such good policing rarely receives public attention and almost never gets documented into an official record.

Third, from a research standpoint, the literature is fairly silent on how often officers use less, not more force. With the exception of studies employing a Social Systematic Observation (SSO) methodology, which is rare, it is nearly impossible to determine how well officers perform in this regard. Having the good fortune to conduct such a project, I found that officers are far more likely to use less force than permitted by law, not more (excessive) force, when faced with resistant suspects. That is, officers were much more apt to de-escalate situations when suspects were attempting to escalate the level of conflict. Unfortunately, this form of good policing often gets overlooked within the national debate.

Finally, it is important to recognize that the available research to date doesn’t capture the full spectrum of understanding when it comes to proper and improper force. There is much work yet to be done in this area. Nonetheless, irrespective of the research informing on the topic, one must be ever cognizant that citizen perceptions and experiences matter. When everyday citizens view a video of police behavior (or witness it in person) and consider it a questionable application of force, police officials need to recognize such perception. Too often, officials hunker down into defense mode seeking to justify the behavior, which just causes the citizenry to become even more distrustful of the police and the cycle continues benefitting no one.

Headline image credit: That’s The Sound of the Police, Occupy Oakland Move In Day (13 of 31) by Glenn Halog. CC-BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The visual, experiential, and research dimensions of police coercion appeared first on OUPblog.

Publishing Philosophy: A staff Q&A

This March, Oxford University Press is celebrating Women in Philosophy as part of Women’s History Month. We asked three of our female staff members who work on our distinguished list of philosophy books and journals to describe what it’s like to work on philosophy titles. Eleanor Collins is a Senior Assistant Commission Editor in philosophy who works in the Oxford office. Lucy Randall is a Philosophy Editor who works from our New York office. Sara McNamara is an Associate Editor who assists to manage our philosophy journals from our New York offices. Find out what they think about working on philosophy titles below:

How did you get interested in philosophy?

Eleanor Collins:

I studied philosophy A-level under a brilliant teacher, Ellis Gregory. After that I continued with a joint undergraduate degree in Philosophy and English at the University of Sussex. I had been particularly interested in history of philosophy, but ended up in a very engaged and lively seminar group in the metaphysics and epistemology options that were available, which – in the end – made that the course I remember most vividly.

Sara McNamara:

I took my first philosophy class in the first semester of my freshman year of college. I did not know anything about philosophy, but a scheduling conflict left me a class short for the semester and the course fulfilled one of my university’s general education requirements. I was riveted by my professor’s descriptions of ancient Athenian culture and the audacious defiance of Athens’ gadfly Socrates. From that moment forward I was hooked. I went on to add philosophy as a second major, taking nearly every course the department offered, and eventually earned both an M.A. and a Ph.D. in philosophy.

Lucy Randall:

Different things that I read for pleasure and for school over the years overlapped with philosophy, and I wanted to learn more by immersing myself in it at OUP.

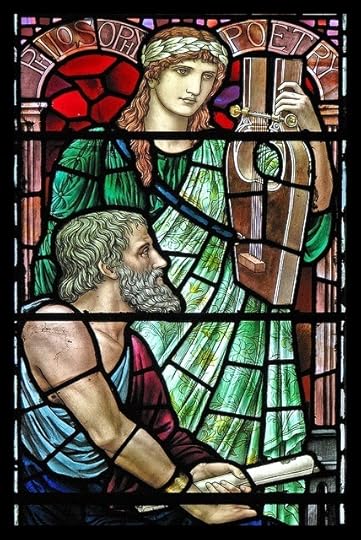

Philosophy & Poetry by Lawrence OP. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr

Philosophy & Poetry by Lawrence OP. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr What’s a current project that you are excited about?

Eleanor Collins:

I hope this answer won’t seem predictable but it has to be our new twitter feed @OUPPhilosophy. It’s doing extremely well and is a great way of keeping up with developments in philosophy more generally, as well as the work of OUP authors.

Sara McNamara:

We were delighted to welcome The Monist, one of the most important journals in the American philosophical tradition, to OUP this year. I have been working on The Monist’s transition to OUP for the last several months, and I’m completely honored to have the opportunity to play a role in this iconic journal’s long and prestigious history.

Lucy Randall:

We’ll soon be launching a new series in philosophy and literature edited by Richard Eldridge, with each book focusing on philosophical themes in a major work of literature. One to look out for!

What would be your top tips for an aspiring academic author?

Eleanor Collins:

Be patient, and try to publish a few good articles in well-established journals before thinking about a book contract: this will help get your work out there, and your name and ideas known.

Sara McNamara:

The best advice I can give to aspiring academic authors is to start/join a writing group. These groups can be small or large, formal gatherings, or relaxed hangouts. The crucial thing is that you find a constructive space to discuss your work with others.

Lucy Randall:

It’s always a good idea to be professional about peer reviews. This is a good way to help others in your profession and also build a good relationship with acquisitions editors. Also, don’t be afraid to reach out and make contact at any point when you’re working on a book project, even if you’re in the very early stages.

What is the most challenging part of your job?

Eleanor Collins:

We publish a lot of titles every year, so there is always a lot going on in the office: new books and manuscripts arriving, cover designs to consider, materials to prepare, and queries to answer. While it is a challenge, it’s also part of what makes the job so interesting and varied.

Sara McNamara:

The most challenging part of my job has been learning about other academic disciplines. In addition to working on philosophy journals, I also manage titles in other fields. While my background in philosophy has been a tremendous asset to my work on journals like The Monist, I have a lot to learn about music, religion, and archaeology.

Lucy Randall:

Keeping up with all the impressive things our authors are doing! That, and walking away from a project that I felt invested in.

What are you currently reading?

Eleanor Collins:

At the moment I am reading Boredom: A Lively History, by Peter Toohey. It’s broad-ranging and accessible, and (amongst other things) explores representations of boredom in art and literature across the ages. The book group I am in has also just finished reading Penelope Fitzgerald’s The Blue Flower. It tells the story of the early years of the poet Novalis, and is unlike anything I’ve read before. Highly recommended.

Sara McNamara:

I am in the final pages of friend and OUP colleague Robert Repino’s debut novel, Mort(e). The pleasure I felt in buying the book as a celebration of my friend’s accomplishment has only been exceeded by my enjoyment in reading it. Mort(e) is earnest, original, and unassumingly insightful.

Lucy Randall:

I’m currently reading Ian McEwan’s The Children Act and a backlog of New Yorker issues from the past month or so (as usual).

If you could invite any three philosophers to a dinner party, who would you choose and why?

Eleanor Collins:

I suspect I would enjoy the company of David Hume, whose work I have always found entertaining and amusing to read; and then René Descartes and Thomas Hobbes. I have a long-lived interest in the early modern period, so these are obvious choices for me.

Sara McNamara:

The first two people I would invite to a dinner party are not, strictly speaking, philosophers. Despite the fact that they are called poems or short stories, the writings of Rainer Maria Rilke and Jorge Luis Borges are intensely philosophical. Their works, as such, always inspired me, made me strive to articulate in my own writing the thoughts and concepts that I found most challenging and elusive. I would love little more than to be able to sit in their presence for an evening. My final invitee would be the incomparable Friedrich Nietzsche. His bold and challenging writings – especially Thus Spoke Zarathustra and The Gay Science – should be required reading. I am not completely sure he would be an enjoyable dinner companion. It is likely he would seek to dominate the conversation and/or antagonize the other guests. Nonetheless, he would be most welcome.

You can explore free journals articles and online resources via our Women in Philosophy site to discover both famous and lesser known female philosophers.

Feature Image Credit: Book Exposition Composition, Poland, Zeromski Kielce, by jarmoluk. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Publishing Philosophy: A staff Q&A appeared first on OUPblog.

March 14, 2015

Putting two and two together

As somebody who loves words and English literature, I have often been assumed to be a natural enemy of the mathematical mind. If we’re being honest, my days of calculus and the hypotenuse are behind me, but with those qualifications under my belt, I did learn that the worlds of words and numbers are not necessarily as separate as they seem. Quite a few expressions use numbers (sixes and sevens, six of one and half a dozen of the other, one of a kind, etc.) but a few are more closely related to mathematics than you’d expect.

Put two and two togetherLet’s start with an easy one. It doesn’t take a mathematical whiz to know that 2 + 2 = 4 and that’s indeed the heart of this expression. To put two and two together is used to mean ‘draw an obvious conclusion from what is known or evident’. Conversely, if you say that somebody might put two and two together and make five, you’re suggesting that they are attempting to draw a plausible conclusion from what is known and evident, but that their conclusion is ultimately incorrect. 2 + 2 = 5 was famously used in George Orwell’s Ninteen Eighty-Four as an example of a dogma that seems obviously false, but which the totalitarian Party of the novel may require the population to believe: ‘In the end the Party would announce that two and two made five, and you would have to believe it.’

Fly off at a tangentI remember a moment of surprise in the middle of one of my mathematics A-Level classes. It was a nice change from the almost unbroken moments of bewilderment that characterized the experience. It was when we were looking at the equations relevant to what happens when something rotating on an axis suddenly stopped. Well, guess what? It would go off at a tangent.

So, what is a tangent? It’s a straight line that touches a curve at a point, but (when extended) does not cross it at that point. (It’s also apparently ‘the trigonometric function that is equal to the ratio of the sides [other than the hypotenuse] opposite and adjacent to an angle in a right-angled triangle’, but the less said about that the better.)

In common parlance, of course, it simply means ‘a completely different line of thought or action’. While we’re mentioning the hypotenuse, you may well recall that it is ‘the longest side of a right-angled triangle, opposite the right angle’, but may not know the word’s origin: it ultimately comes from the Greek verb hupoteinein, from hupo ‘under’ + teinein ‘stretch’.

The lowest common denominatorIn a fit of pique, you might have described a person or a group as the lowest common denominator. It is often said in a derogatory way to mean ‘the level of the least discriminating audience’; for example, ‘they were accused of pandering to the lowest common denominator of public taste’. But what actually is a denominator?

Cast your mind back to the world of fractions–specifically vulgar fractions, or those that are expressed by one number over another, rather than decimally. The number above the line is the numerator and the number below the line is the denominator. In ½, for instance, the numerator is 1 and the denominator is 2. In mathematics, the lowest common denominator is ‘the lowest common multiple of the denominators of several vulgar fractions’. For instance, the lowest common denominator of 2/5 and 1/3 is 15, as that is the lowest common multiple of the denominators 5 and 3; the fractions would become 6/15 and 5/15 respectively. It isn’t entirely clear how this sense transferred to the broader, non-mathematical sense.

Image Credit: “Math Castle” by Gabriel Molina. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

A version of this blog post first appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

The post Putting two and two together appeared first on OUPblog.

Where do drugs come from? [quiz]

The discovery and development of drugs was not always a straight path. Many times, the drugs that are well-known today — both hallucinogenic and medicinal — were discovered by mistake or originally developed for a much different purpose. How well do you know the history of some of the most common drugs? Take this quiz to find out if you can match the drug to its origin.

Get Started! Your Score: Your Ranking:Featured Image: Opium Poppy by SuperFantastic. CC BY 2.0 via Wikmedia Commons.

The post Where do drugs come from? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

Spiders: the allure and fear of our eight-legged friends

What’s your first reaction when you see this picture? Love? Fear? Repulsion? If you are like many Americans, when you come across a spider, especially a large, hairy one like this tarantula, the emotions you experience are most likely in the realm of fear or disgust. Your actions probably include screaming, trapping, swatting, or squashing of the spider.

Chilean rose hair tarantula. Image credit: Photo by Laurie Kerzicnik. Used with permission.

Chilean rose hair tarantula. Image credit: Photo by Laurie Kerzicnik. Used with permission. Despite their negative reputation, spiders are essential members of the global ecosystem. They are present in all terrestrial habitats, except Antarctica, and thrive wherever insect prey and vegetation are present, including freshwater ponds, caves, agricultural crops, and to elevations over 20,000 feet ¬- over 40,000 spider species worldwide. The thing that many people fear about spiders – the predatory instinct – is exactly what makes spiders beneficial. They feed on a variety of insect and invertebrate prey that humans consider pests.

Spiders are beneficial to humans beyond their role in controlling pests. The silk and venom of spiders has commercial appeal. Due to the strength and elasticity of spider silk, it is being considered for mass production for gloves, bullet-proof vests, parachutes, and cables. A peptide from tarantula venom was found that inhibits atrial fibrillation in rabbit hearts, which may be beneficial for the prevention of arrhythmia in humans.

The more we understand these eight-legged creatures, the less we will fear them. With only a few species considered harmful to humans and their tendency to avoid human encounters and bites, their negative reputation is unjustified.

In honor of “Save a Spider Day” take a look at these fascinating species and marvel at the unique biology and adaptations of the arachnid world.

Cat-faced spider, Araneus gemmoides

Cat-faced spider, Araneus gemmoides In your gardens, these eight-legged hunters will help control the troublesome aphids and spider mites. The cat-faced spider, Araneus gemmoides, will build large spiral orb webs on porches, catching the pesky moths, flies, and mosquitoes that are attracted to lights. They are not the go-to predators for specific pest control outbreaks because of their tendency to feed on a variety of prey. Image credit: Photo by Whitney Cranshaw. Used with permission.

Long-jawed orb-weaving spider, Tetragnatha laboriosa in wheat

Long-jawed orb-weaving spider, Tetragnatha laboriosa in wheat But the presence of spiders, like the delicate-looking long-jawed orb weaver, which feeds on aphids and other wheat insect pests, is critical in keeping pest populations below damaging levels. Image credit: Photo by Laurie Kerzicnik. Used with permission.

Funnel web spider

Funnel web spider Most of us associate spiders with webs, but not all spiders build webs. Web builders include funnel web weavers, tangle web weavers, orb weavers, and sheet web weavers. Image credit: Photo by Whitney Cranshaw. Used with permission

Crab spider, Bassiana sp.

Crab spider, Bassiana sp. Other spiders are considered hunters, ambushers, or burrowers. Hunting spiders don’t use webs or silk to catch their prey. Instead, they chase down and grasp their prey. These include ground spiders, wolf spiders, ant mimics, and sac spiders. Jumping spiders and crab spiders are ambushers. Some crab spiders will await the arrival of large bees and other pollinators two to three times their size within flowers, with their crab-like legs outstretched. When the pollinator arrives, they will snatch it with their extended legs and inject venom. Some of the burrowers include tarantulas and trap door spiders, and they capture prey by hunting and seizing it. Image credit: Photo by Whitney Cranshaw. Used with permission.

Yellow sac spider, Cheiracanthium sp.

Yellow sac spider, Cheiracanthium sp. Spiders are timid and would likely try to escape rather than bite. Biting a human is a waste of venom and depletes one of their only resources for prey capture. Venom is used to subdue or immobilize insect or invertebrate prey. After injecting it, a digestive enzyme is regurgitated onto the immobilized prey, creating a liquid meal that will then be sucked back up by the spider. Image credit: Photo by Whitney Cranshaw. Used with permission.

Jumping spider

Jumping spider Although spiders have eyes, their vision is mainly targeted for sensing movement. They rely on sensory structures such as chemical receptors and fine hairs. The chemical receptors are similar to “taste” hairs when they come into contact with a substrate. The fine hairs are critical for sensing motion, air currents, and vibrations. Image credit: Photo by Alex Stephens. Used with permission.

The Brown Recluse Spider

The Brown Recluse Spider In spite of their bad reputation, only about 100 species worldwide are of medical concern to humans. In the United States, there are only three spiders (five spider species) that can cause real harm to humans: black widows (Latrodectus hesperus, Latrodectus mactans, and Latrodectus variolus), a brown widow (Latrodectus geometricus), and the brown recluse (Loxosceles reclusa). Image credit: Photo by Laurie Kerzicnik. Used with permission.

Unfortunately, spiders often take the blame for any sort of lesion or bite that appears on someone’s body, when, in fact, most of the smaller spiders that are commonly encountered can’t even pierce human skin with their fangs. In the midst of spider hysteria, it’s important to remember that almost all spider bites involving humans are nonthreatening. A spider bite and its associated symptoms are often based solely on anecdotal evidence without a spider being captured or professionally identified. Sometimes a specific species, like the brown recluse, Loxosceles reclusa, is accused of biting someone in a location that is not even part of its native range. Many times the victims of “spider bites” do not witness the bite and sometimes they never saw a spider at all! For years, spider bites have been chronically over diagnosed. These misdiagnoses could, in actuality, be infections (bacterial, fungal, or viral), allergic reactions, other arthropod bites, or many other serious medically-related conditions.

The post Spiders: the allure and fear of our eight-legged friends appeared first on OUPblog.

How I stopped worrying and learned to love concrete

Every British university campus has one, and sometimes more than more: the often unlovely and usually unloved concrete building put up at some point in the 1960s. Generally neglected and occasionally even unfinished, with steel reinforcing rods still poking out of it, the sixties building might be a hall of residence or a laboratory, a library or lecture room. It rarely features in prospectuses and is never – never ever – used to house the vice chancellor’s office.

Even as these buildings were erected, they proved unpopular. At Leicester, student journalists mocked the ‘Neo-Urinal’ halls of residence. At Leeds, academics complained about their working conditions, as they struggled on in leaky, under-heated, acoustically-compromised offices. That these concrete and plate-glass ‘fish-tanks’ were a prize-winning piece of design only made them angrier.

New universities, entirely built in the 1960s, fared even worse. Some students of the University of East Anglia (UEA) were so unhappy with their home that they were provoked to offensive hyperbole, describing their massive, monumental concrete mega-structure as ‘Auschwitz with carpets’.

And these sixties buildings didn’t need to be concrete to be disliked. At Essex in the late-1960s, the tall, brick towers erected for student accommodation sparked hostility from locals and from staff alike. Asked to come up with an appropriate dedicatee for the latest block, lecturers took a vote; the winning name was Kafka.

These buildings attracted opprobrium for several reasons. They were the product of avant-garde architects working with ambitious vice-chancellors. As such, they were always intended to be striking, even shocking; glimpses of the future rather than examples of staid, conventional taste.

They were also built in unpropitious times. The British building industry wasn’t really fit for purpose and struggled to cope with experimental methods. Worse still, the stop-start of government funding made it all but impossible for universities to plan effectively. Buildings were begun before it was quite clear how they would be used and then completed without many essential services because the money had run out. In many cases, of course, they were simply left unfinished, as ambitious – perhaps over-ambitious – projects were curtailed by a sudden stop in their financing.

These financial problems would prove particularly troublesome as the sixties buildings aged: an issue made all the worse by cutbacks and spending freezes in the 1970s and 1980s. Seeking economies, and thinking little of the long term, universities pared their maintenance budgets beyond the bone, with predictable results. Buildings and fittings decayed – and failed. Walls cracked, tiles flew off; in Kent, Leicester, and elsewhere, some structures actually collapsed.

![Ziggurat halls of residence buildings, University of East Anglia by blank space via Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 2.0]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1426354506i/14005290._SX540_.jpg) Ziggurat halls of residence buildings, University of East Anglia by blank space. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Ziggurat halls of residence buildings, University of East Anglia by blank space. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Small wonder, then, that these buildings have proved to be an ambiguous inheritance for most universities. Intentionally assertive and inadvertently problematic, they have even been seen as a positive handicap for recruitment, with numerous surveys suggesting that potential students still look down on ‘sad’, ‘concrete’ institutions which they continue to characterize as the ‘worst’ universities.

How, then, have I learned to love the loveless concrete that characterizes so many of our campuses? Why do I believe that we should all come to embrace our sixties buildings?

Well, in part, I think these projects are worth celebrating because they are monuments to a very different understanding of the university: a moment when the state was persuaded to support higher education for its own sake. It was a short-lived episode, and one that was always compromised by the imperatives of the Cold War and the rather generalized belief that the economy would be aided by growing numbers of graduates. But the idea that universities were worth building because they would elevate the cultural life of the nation; the notion that higher education is a more than instrumental, more than solely individual good: these were noble aspirations and their loss is a sad one.

It’s worth recalling, too, that many of the sixties buildings were the work of front-rank architects: international names whose achievements are now increasingly celebrated. Leicester possesses a tower by James Stirling; UEA was designed by Denys Lasdun. Campuses all across the country are host to some of the greatest examples of Brutalist architecture in the world. As fashions change, and as the wheel of taste turns back to this heroic period of British architecture, I confidently predict that many of these neglected buildings will become tourist attractions.

Above all, as a historian, it seems to me that these buildings provide a most wonderful way of understanding universities – and their architecture – more generally. Their ambition, their utopianism is more than matched by some of the buildings built before them and many of those built since. That’s what universities do. Campuses are always landscapes of idealism; shrines, in a sense, to how one generation imagines the future should be.

The failure to complete these projects is also telling: not just because it speaks of how priorities change and funding streams are diverted; but also because it shows how succeeding generations turn their back on what their predecessors did. Master-plan is succeeded by master-plan; vision by revision. Each time, the university tried to build its way out of trouble by rejecting the past and starting again.

This, in the end, is why universities find their sixties buildings so embarrassing; just as, in the 1960s, they found their interwar architecture so shaming. And in the 1920s, it was their Victorian homes that they shunned and sought to hide. It’s also why so little has been written about university architecture. Universities try – sometimes very hard – to forget. It’s important that they’re not allowed to, not least because of what we might learn from the successes, and the failures, of the past.

E.C. Stoner Building, University of Leeds by Mtaylor848. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How I stopped worrying and learned to love concrete appeared first on OUPblog.

March 13, 2015

Chlamydia: a global health question?

A leading researcher in the field of immunogenetics, Servaas Morré has investigated women’s genetic susceptibilities to Chlamydia trachomatis, recently co-authoring “NOD1 in contrast to NOD2 functional polymorphism influence Chlamydia trachomatis infection and the risk of tubal factor infertility” in a special virtual issue of Pathogens and Disease. We sat down with Morré to discuss his findings about the most common sexually transmitted bacterial infection and the impact his research will have on treatment in the years to come.

What first interested you in specializing in Chlamydia research?

Chlamydia trachomatis is the most prevalent bacterial STD, with over 100 million new infections each year. The disease causes Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID), ectopic pregnancy, and tubal infertility, which is the reason for the many treatment and screening studies that combat this devastating infection.

In addition, the unique development cycle of Chlamydia trachomatis and its immunological interaction with its host create challenges in finding new treatment and vaccine approaches for its elimination.

Can you explain how Chlamydia can increase the probability of transmitting HIV?

This is the double edged sword. When Chlamydia exists before an HIV infection, it predisposes the subjects to HIV; and when HIV exists before a Chlamydia infection, it increases the risk of Chlamydia infection.

When a Chlamydia trachomatis infection goes untreated (which is the case in high-prevalence HIV regions), viral shedding will increase, as will the probability of HIV transmission during intercourse with an uninfected partner. With this in mind, HIV and STD detection and treatment should always be advocated for as a combined effort to manage these infections, especially in developing countries.

How does treatment of Chlamydia in Europe differ from the rest of the world?

In Europe—especially Eastern Europe—the treatment and screening of Chlamydia trachomatis is often suboptimal, which means partner treatment, monitoring during pregnancy, and risk group analyses could be improved. In the rest of the world, however, the problem is far more serious.

In a presentation on Chlamydia trachomatis at the 10th Annual Amsterdam Chlamydia Meeting in Africa, Dr. Remco Peters reported that countries with a Chlamydia trachomatis prevalence of over 20% displayed major problems in combating the infection. These problems include challenges in Chlamydia trachomatis management and control, lack of awareness among those infected, and struggles to incorporate the issue on the international public health agenda.

Can you describe how your research into Chlamydia and female infertility may affect medical approaches to infertility?

In Western society, 15% of couples are infertile, meaning they do not conceive within one year and will attend a fertility clinic or gynecologist. Chlamydia trachomatis is the major pathogen involved in infertility due to its ability to cause tubal pathology. This is only believed to occur in a subgroup of women who cannot combat Chlamydia trachomatis infection due to adverse genetic variation in genes involved in pathogen recognition and inflammatory responses. The genetic background of host pathogen interaction is expected to provide new personalized medical diagnostic approaches in the field of female infertility to decrease current misdiagnosis.

Image Credit: “McFarland standards, number 0.5, 1 and 2 from left to right” by Akaniji. CC by 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Chlamydia: a global health question? appeared first on OUPblog.

Clinical placement in Nepal: an interview with Ruth Jones

In May last year, Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine, in partnership with Projects Abroad, offered one lucky medical student the chance to practice their clinical skills abroad in an international placement. The winner was Ruth Jones from the University of Nottingham, who impressed the judging panel with her sincerity, dedication, and willingness to become the best doctor she can be. Ruth has decided to take her placement in Nepal.

Earlier this year, we caught up with Ruth to find out more about her plans for her placement.

Why Nepal?

I had nearly the whole world to choose from, so it took quite a lot of thinking to narrow down the options. I wanted a placement that included three things: I wanted to choose somewhere that couldn’t rely on technology or equipment to inform diagnosis or treatment; I wanted the option of working in an emergency as well as a community setting; and of course, I wanted to visit an amazing country! The shortlist included the Cook Islands, the Solomon Islands, and Tanzania, but Nepal seemed to be the best fit.

What do you hope to achieve on the placement?

By the time I go on my placement, I will have completed my final exams. I’m really hoping to put into practise all of the skills I’ve been working on for the past three years, as well as gaining confidence in them. Above all, my main concern is helping those in need while I’m out there.

Ruth Jones, winner of the 2014 OHCM Clinical Placement Competition

Ruth Jones, winner of the 2014 OHCM Clinical Placement Competition What do you expect to encounter in your day to day work?

I’m planning on working in a trauma setting, in a hospital in Kathmandu, as well as participating in community outreach work to more remote villages. From what I’ve read, attempted suicides, homicides, and road traffic accidents are the top causes of admission to trauma units in Nepal, so this is what I’m expecting to see. The community outreach work is aimed at providing free health checks and basic medications to villages usually too far away or too impoverished to receive medical assistance.

What aspect of the placement are you looking forward to the most?

That’s a tricky one! I’m looking forward to everything about it — it’s my main motivation for hitting the books every evening and weekend at the moment. Of course, I’m really looking forward to seeing how medicine is practised in Nepal, but I’m also very excited about the opportunity to walk some Himalayan foothills.

What are your plans for the future, after the placement and beyond?

I was in the RAF before I returned to university, so I’ll be re-joining as a Medical Officer. My FY1 year is within the West Midlands Deanery, so I have that to look forward to. As for my eventual specialty; it’s too early to say definitively, but so far I’ve really enjoyed the time I’ve spent in Emergency Medicine, and in GP surgeries, so I think those two are my front runners right now.

Finally, what drew you to Medicine in the first place?

I definitely didn’t grow up dreaming of being a doctor; I thought I was neither clever nor committed enough to study it. I originally trained as a PE teacher before joining the RAF as a training and development officer. It was after I came back from deployment that I asked myself whether I would look back on my career, and think that I’d achieved everything I was capable of. A profession combining intellectual rigour with the opportunity to help people seems like the perfect job to me. And the fact I have the chance to return to the RAF to serve as a doctor is an extra bonus.

Featured image: Great Stupa of Bodnath, Kathmandu valley, Nepal, by Jean-Marie Hullot. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Clinical placement in Nepal: an interview with Ruth Jones appeared first on OUPblog.

It’s never too late to change

Ever wanted to change a behavior or habit in your own life? Most of us have tried. And failed. Or, we made modest gains at best. Here’s my story of a small change that made a big difference. Just over two years ago, I decided, at the ripe old age of 55, that it was time to begin exercising. Some of the excuses I had used over the years included:

I can’t possibly work that into my morning routine; The children need me to be home when they first wake up; What would I do if I ran into a student or faculty member I knew while I was working out? Gym membership costs too much—that money is needed for other things; I am too old, and too worn out, to change now.It all began one sunny day when we were on sabbatical in Florida. Away from the Canadian east coast winter, with a more flexible schedule, and with our girls now grown, I had simply run out of excuses.

So I started. It was a long and slow process. Many months passed before there was evidence of much change. But I kept it up. A week turned into a month. A month turned into a season and before long I had established some new habits, and new ways of thinking about exercise and acting on those thoughts. Over time, I lost a bit of weight and reduced the size I wore. Friends noticed the change and encouraged me on. But, for me, the eureka moment came when I realized about four weeks into my new routine that I can do this! I could see that it would be good for me and probably good too for those around me. While change is always difficult, it is easier if: (1) you want to change your ways; (2) someone shows you how to change your ways; and (3) you are reinforced by others as they see small changes take hold. So how does this home-grown story of modest change relate to my research program?

For over twenty-five years I have been studying domestic violence and more recently the stories of men who batter. With my colleague Barbara Fisher-Townsend, I have attempted to understand how men who abuse their intimate partners tell their own stories—the downward vortex into abusive acts, contact with the criminal justice system and batterer intervention programs, and for some the journey towards changed thinking and changed behavior.

Safety for those who have been abused and changed behavior for those who act abusively: these are the goals of intervention. A highly functioning coordinated community response, like HomeFront in Calgary, is a wonderful model. But there are many others too across the United States and Canada.

So what helps change to happen in the life of a man who has battered his intimate partner? Ongoing accountability is one of the biggest factors to account for why some abusive men change, a little, or a lot.

It works a little like my story of beginning to exercise. First, the men who are abusive must want to change. Next, someone shows you how to change. Then, you are reinforced by others as they see small changes take hold.

Social workers are in the business of trying to help people change. Many of their clients don’t believe change is possible, or desirable. While there is clearly a role for law enforcement and the criminal justice system, real change rarely occurs without a coordinated community response that identifies something that needs to be changed followed by strategies to make it possible.

In a world that often glorifies violence in sports, in the movies, and in everyday living, I think that those whose life work involves trying to help people become less violent and less controlling of others should be honored and appreciated. For the month of March, I suggest that we remember the important role that social workers play in our communities—paving the way for change.

Headline image credit: Bicycles. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post It’s never too late to change appeared first on OUPblog.

Unbossed, unbought, and unheralded

March is Women’s History Month and as the United States gears up for the 2016 election, I propose we salute a pathbreaking woman candidate for president. No, not Hillary Rodham Clinton, but Shirley Chisholm, who became the first woman and the first African American to seek the nomination of the Democratic Party for president. Announcing her candidacy in January 1972, she confronted her race and gender head on: “I am not the candidate of black America although I am black and proud. I’m not the candidate of the Women’s Movement of this country although I am a woman and I’m equally proud of that. I am a candidate of the people and my presence before you now symbolizes a new era in American political history.”

And yet far too often Shirley Chisholm is seen as just a footnote or a curiosity, rather than as a serious political contender who demonstrated that a candidate who was black or female or both belonged in the national spotlight. Put another way, she anticipated the 2008 contest between Barack Obama and Hillary Rodham Clinton by almost forty years.

It turns out there have been more women candidates for president than most people realize. According to political scientist Jo Freeman, more than fifty women have run for the highest office. The vast majority were candidates on third-party or fringe tickets, including free love advocate Victoria Claflin Woodhull way back in 1872. Women’s presidential credibility took a giant leap forward when Maine Senator Margaret Chase Smith campaigned for the top spot on the Republican ticket in 1964. Eight years later Shirley Chisholm broke another precedent by becoming the first serious female candidate for the Democrats.

Chisholm’s path to her presidential bid began in Brooklyn, New York. The daughter of Caribbean immigrants, she graduated with honors from Brooklyn College in 1946, and embarked on a career in early childhood education. Soon she found herself increasingly involved in local Democratic politics in her Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, a grass-roots entry into politics that was typical of many women, black and white, at the time. Recruited to run as a candidate, she served in the state assembly from 1964 to 1968 before winning election to Congress in 1968, the first African American woman ever to serve. Her campaign slogan was “Fighting Shirley Chisholm—Unbossed and Unbought.”

Shirley Chisholm. Photo by Thomas J. O’Halloran. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Shirley Chisholm. Photo by Thomas J. O’Halloran. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Chisholm’s political priorities focused on the connections between race, class, and gender long before feminist scholars coined the term “intersectionality.” She hoped to build coalitions and bridges between those who were too often on the fringes of the political process. She was a founder of both the Black Congressional Caucus (1971) and the National Women’s Political Caucus (1972). Yet she was always clear about where the greatest discrimination lay. “As a black person, I am no stranger to race prejudice. But the truth is that in the political world I have been far oftener discriminated against because I am a woman than because I am black.”

From the start, Chisholm’s campaign was hampered by lack of funding and poor coordination, which limited her ability to capitalize on grassroots support for her candidacy. Although Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem ran as Chisholm delegates in New York, her long-shot candidacy received less than robust support from feminist leaders or black politicians, who coalesced around anti-war candidate George McGovern. In the end she garnered just shy of 152 delegate votes at the Democratic National Convention. Chisholm went on to handily win re-election to Congress that year despite the Nixon landslide, and remained there until her retirement in 1982.

Shirley Chisholm saw her presidential bid as a spur to greater participation in American politics by a more diverse range of voters and activists. As she said when she announced her candidacy in 1972, “I stand before you today to repudiate the ridiculous notion that the American people will not vote for a qualified candidate because he is not white or because she is not male. I do not believe that in 1972, the great majority of Americans harbor such narrow and petty prejudices.” I suspect that more Americans than she let on did indeed harbor such prejudices back then, but her pathbreaking candidacy represented a glimpse of “a new kind of America” she heartily looked forward to. More than forty years later, we are still seeing how the story plays out.

Headline image credit: Photo by Texas State Library and Archives Commission. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Unbossed, unbought, and unheralded appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers