Oxford University Press's Blog, page 686

March 21, 2015

The crime is the fruit of the theology: Christian responses to 50 Shades of Grey

The much anticipated Valentine’s Day release 50 Shades of Grey set off a flurry of activity on social media sites, with bloggers lining up to cajole, shame, reason, or plead with women to resist temptation and abstain from viewing the film. In a case of strange bedfellows, if you will, conservative Christians and liberal feminists alike castigated the film for its packaging of abuse as mainstream entertainment. (Feminists and Christians were also joined by a fair number film critics, whose condemnation revolved more around the film’s artistic offenses than its moral flaws.)

Christians had reason to be concerned about the film’s pernicious influences, even among their own. A 2013 Barna Group study revealed that roughly 9% of practicing Christians had read 50 Shades since its publication the previous year, the same proportion as the general adult population. Despite (or, one wonders, because of?) the social media campaign, the film opened to a record-breaking weekend, though ticket sales have reportedly dropped off rather dramatically since. The film has, however, succeeded in generating a lively conversation among Christians about sex, power, and the abuse of women.

It wasn’t all that long ago that the topic of abuse was all but taboo in many Christian circles. Among conservative Christians who instructed women to submit to their husbands and men to assert headship over women, there was little space in which to address issues of abuse, especially abuse that occurred within the household. In recent years, however, churches, organizations, and individuals have worked to address domestic abuse within Christian communities more openly. Public scandals—from the treatment of rape victims at Bob Jones University, to the well-publicized misogyny of evangelical mega-church pastor Mark Driscoll, to accusations of domestic abuse brought against emergent church leader Tony Jones—have kept the topic of abuse a matter of public discussion among American Christians.

In bringing to light the problem of abuse perpetrated by men who profess to be Christians, however, fellow believers must inevitably confront a critical question: Do perpetrators commit acts of violence against women in contradiction to the theology they espouse, or does that theology itself facilitate a culture of violence against women?

Courtesy of Universal Studios.

Courtesy of Universal Studios.For the majority of Christians, the 50 Shades backlash has reinforced a narrative that locates abusive practices comfortably outside of Christian tradition, and then situates the faith as a powerful antidote to the oppression of women. This narrative, it may be worth noting, finds echoes in American Christians’ enthusiasm, as of late, for global and domestic anti-trafficking campaigns, and for a public concern about the status of women in Islamic cultures. E. L. James’s “soft porn” depiction of male dominance and female submission, together with Hollywood’s eagerness to cash in on these domination fantasies, certainly lends itself to this interpretive trend.

A smaller number of Christians, however, have demonstrated a willingness to question whether Christianity itself, and particularly the patriarchal teachings that have long shaped Christians’ views of gender and sexuality, may in fact contribute to the abuse women suffer at the hands of Christian men.

This was precisely the question posed over a century ago by a remarkable woman by the name of Katharine Bushnell. Like many other Protestant women of her day, Bushnell was a social reformer. After a brief career in missions, she took up the cause of temperance, which soon brought her into contact with the most destitute of women. Troubled that a purportedly Christian society rebuked “fallen women” as beyond redemption, while essentially allowing men to do as they pleased, Bushnell took up the issue of prostitution in Victorian society. Through her efforts to expose the state-sanctioned prostitution in Wisconsin lumber camps, and then for her campaign against the abuse of women at the hands of the British military in colonial India, Bushnell emerged as an internationally-known activist.

Time and again Bushnell was startled to find that it was Christian men who were perpetrating acts of cruelty against women, or upholding legal or social structures that enabled other men to do so. Even when such men were publicly called out for their complicity in crimes against women, other Christians often continued to consider such men “respectable” Christian gentlemen. Ultimately, Bushnell came to conclude that Christianity itself must be to blame, and she turned her attention to the Christian Scriptures in order to discover the theological roots of the abuse of women.

She found what she was looking for in the early chapters of Genesis, where Eve was purportedly but an afterthought, a “weaker vessel,” culpable for humanity’s fall into sin—a mistake so grave that even Christ’s atonement was not sufficient to lift the curse from her and all women after her. Bushnell also found evidence that the “sacred institution” of Christian marriage in fact robbed women of their will in such a way as to amount to nothing less than “the sexual abuse of the wife by the husband.” She defended her use of the term “abuse,” arguing that subordination was abuse. “Man would feel abused if enslaved to a fellow man,” she argued, and the same was true of women, even if theologians liked to consider women’s subjugation “the happiest state in which a woman can exist.” All of this led Bushnell to conclude that crimes against women were, indeed, “the fruit of the theology.”

Despite these conclusions, however, Bushnell didn’t reject Christianity in its entirety. Rather, trained in classics, she investigated English translations in light of Hebrew and Greek texts, whereupon she discovered a centuries-long pattern of mistranslation and misinterpretation that had distorted true Christianity into “a whole fossilized system” of patriarchal theology. By retranslating the Scriptures, she provided a new gospel for women—one that did not prescribe subordination to men as perpetual penance for Eve’s sin, but rather offered an expansive biblical vision for women’s religious and social authority. Most remarkably, Bushnell developed her radical feminist re-readings of the Scriptures while upholding the authority of the scriptures. Indeed, when it came to issues of biblical interpretation, she identified as a fundamentalist, staunchly opposed to the threats of modernism.

Bushnell’s teachings, which she published as God’s Word to Women, remain popular among some conservative Christian subcultures today, and they have proven formative to a number of Christians who are working within their communities to combat the abuse of women and advocate for women’s religious and social authority.

Even today, Bushnell’s writings offer a poignant challenge to Christians who may be tempted to locate the cause of abuse outside the Christian tradition, and to turn a blind eye to the ways in which patriarchal interpretations of the Scriptures may have distorted Christianity itself.

Those seeking to combat the abuse of women worldwide as part of their Christian witness may be better positioned to do so, and able to do so with more integrity, after coming to terms with the effects of patriarchy within their own tradition. And for that, Katharine Bushnell may be a good place to start.

The post The crime is the fruit of the theology: Christian responses to 50 Shades of Grey appeared first on OUPblog.

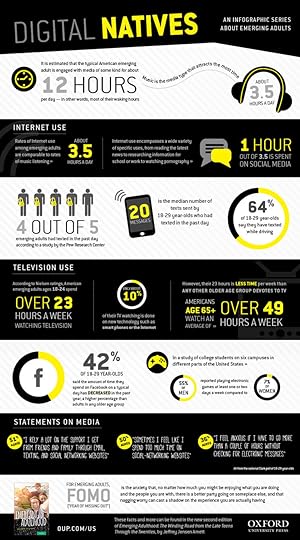

How digital natives spend their time

Who is an emerging adult? How often do young adults text? How long do they spend on the Internet everyday? Where do they watch television? Which social networks do they use?

Ten years ago, Jeffrey Jensen Arnett published a groundbreaking examination of a new life stage: emerging adulthood, a distinct culture for people in their late teens and early twenties. Where once there were only children and adults, then there were teenagers, then adolescents, and now emerging adults. Arnett has revised and updated his book to include the newest findings on media use, social class issues, and their distinctive problems. Most importantly, he refutes many of the stereotypes, such as laziness and selfishness, that are held about these digital natives.

Download the pdf or jpg of the infographic.

Headline image credit: Mobile phone. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post How digital natives spend their time appeared first on OUPblog.

How policing in the UK has changed [infographic]

Policing in the United Kingdom is changing. Far from the traditionalism which defined the role of the police officer in the past, recent years have seen the force undergo wide-reaching alterations designed to shake off the Victoriana which entrenched UK policing in outdated practices, equipment, and organizational structure. In addition to policy-led modernization, extensive budgetary cuts in the wake of the 2007-2008 financial crisis have had significant ramifications for the future of policing. But what can be said of UK policing today?

The power that modern officers possess remains a contentious issue. In the post-9/11 world and more locally in the wake of the 7/7 bombings, UK police have been given extensive powers to combat the thereat of terror, such as those enshrined in the Terrorism Act 2006 which significantly extended stop and search powers and made the arrest of terror suspects much easier (though these anti-terror measures are of debatable efficacy). Along with contemporary concerns over accountability and openness – exemplified in changes regarding RIPA – the practice and procedure of UK policing today has very much been affected by anti-terror legislation.

Regarding the organisation of police, the introduction of PCSOs in 2002 and the steady increase in volunteer ‘Special Constables’ has meant that a large quota of today’s force is made up of roles that are fundamentally different to that of a police officer. Similarly the governing bodies that transcend regional forces have changed in recent times, most notably with the establishment of the National Crime Agency in 2013 which superseded other national law enforcement agencies in England and Wales. These new occupations and organisational bodies mark a notable difference from ways in which the force has operated previously.

So UK policing today has modernised and adapted in accordance with changes in police law and management, which in turn are reacting to the socio-economic developments that have entailed deep consequences for the United Kingdom. But is this how policing today ought to be? What else characterizes policing in recent times and, crucially, where should it be going? Let us know what you think via Twitter or in the comments section below. We look forward to hearing your thoughts.

Headline image credit: Police, by Matty Ring. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post How policing in the UK has changed [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

March 20, 2015

Oral history online: blogging to reach new audiences

I am a child of the internet age. I have never not had a computer in my house. Being in Columbia’s Oral History Master’s Program (OHMA), I’ve read articles for class that describe how oral historians recorded and edited audio in the past. Every time I read one of those articles, I call my mom, who used to work editing tape in the 70s and 80s. “How did you do it?” I ask. “How did you edit with a razor, with no undo button? If it was still like that, I would never have entered this field.” She always laughs, saying they didn’t have that technology and didn’t know how easy it could be.

It’s really a moot point though. We do have this technology. Oral history is now something that more people can create and consume. People can record audio on their phones, later uploading it to a program like Hindenburg or even Garage Band to make edits. So when people ask me what I’m studying, why does the following exchange occur?

“I’m studying oral history.”

“World history?”

“Oral history.”

“Oh. What’s that?”

To the general public, oral history is a thing you do when you have an assignment in school to interview someone in your family, for the purpose of preserving either family history or local community history. But oral history could potentially engage a much broader audience made up of producers and consumers. Not only can people easily record oral histories themselves, but the ability to listen to audio pretty much anywhere means text isn’t the only way to access oral histories.

For class, we recently listened to I Can Almost See the Lights of Home. Beautifully constructed—somewhere between documentary and sound art—the piece describes life in Harlan County, Kentucky. Even so, we learned it wasn’t widely heard because, at the time it was produced, there was no easy way to download and listen to a long-form piece. As someone who frequently traverses the entire length of Manhattan on the A train, I can imagine half the people in the train car would listen to this if it were available as a podcast.

OHMA is interested in pushing the boundaries of what oral history can do, as indicated by the diversity of interests and expertise in this year’s cohort, which includes a former book publisher, a journalist, and a social worker in a methadone clinic, to name a few. We all come with different goals and the program encourages us to take oral history in any direction that interests us. One year, a student’s thesis combined oral history and advocacy through the creation of Groundswell, a movement for social justice oral history projects.

Oral history deserves to be shared.

In keeping with the progressive and outward-facing nature of OHMA, we have begun to focus on strengthening our blog, interfacing with broader uses of storytelling and diving into oral history’s relationship with other disciplines. To this end, I’ve started two series: a bi-weekly roundup of interesting projects I’ve found that involve oral history and a series of OHMA alumni profiles. Both demonstrate the range of oral history’s applications. Whether it’s looking at how someone used oral histories from the Ellis Island Oral History Project to create a song or finding Spock’s life history interview on the Yiddish Book Oral History Project, people are able to see the value of oral history as a field of study and oral historians themselves can see some of the many different applications of their work.

In addition to my work, the OHMA blog invites students and community members to reflect on oral history workshops or events they attended as a way of extending our work beyond people who are physically in New York City. We encourage partners to share new developments or events in the field with our readership.

Oral history deserves to be shared. I think most of us who do oral history can agree that what we do is valuable to the wider public. After partnering with the Tenement Museum and discovering the complete lack of African Americans in the historical record of the Lower East Side, I chose to do my thesis on the predominantly African-American community of St. Augustine’s Episcopal Church. By making clips of my interviews easily accessible online, people will be able to see that there has been a vibrant African American community that contributed to the larger community of the Lower East Side, despite its small size.

I hope that the outward focus of OHMA’s blog encourages readers to think about larger audiences and different forms of oral history. Mary Marshall Clark, director of the Center for Oral History Research, says, “The great strength of oral history is its ability to record memories in a way that honors the dignity and integrity of ordinary people.” As oral historians, we have the responsibility to not just record these histories, but to ensure that ordinary people—not just researchers and academics—have the ability to be enriched by oral history too.

Image Credit: “OHMA students performing oral histories in public with the Sankofa Project” by Amy Starecheski. Photo used with permission.

The post Oral history online: blogging to reach new audiences appeared first on OUPblog.

Early responses to Mendeleev’s periodic law [quiz]

The periodic system, which Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev presented to the science community in the fall of 1870, is a well-established tool frequently used in both pedagogical and research settings today. However, early reception of Mendeleev’s periodic system, particularly from 1870 through 1930, was mixed. In Early Responses to the Periodic System, Masanori Kaji, Helge Kragh, and Gábor Palló explore these reactions in eleven different countries and one region. How much do you know about these early responses? Take this quiz to find out.

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Feature Image: Lab book – Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory by Daderot. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Early responses to Mendeleev’s periodic law [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

Interpreting the laws of the US Congress

The laws of US Congress—federal statutes—often contain ambiguous or even contradictory wording, creating a problem for the judges tasked with interpreting them. Should they only examine the text or can judges consult sources beyond the statutes themselves? Is it relevant to consider the purposes of lawmakers in writing law?

In Judging Statutes, Robert A. Katzmann offers a powerful challenge to Antonin Scalia’s textualist approach with a spirited and compelling defense of why judges must look at the legislative record behind a law—and not merely the statute itself. We interviewed Judge Katzmann about methods of interpreting statutes, understanding statutes through legislative history, and increasing understanding between the courts and Congress. In the clips below, he discusses textualism and purposivism, two methods judges use to interpret statutes, how legislative history guides judicial understanding of statutes, and ways to improve the relationship between the courts and Congress.

Methods of interpreting statutes

Understanding statutes through legislative history

Increasing understanding between courts and Congress

Headline image credit: Male Judge Holding Law Book. © AndreyPopov via iStock.

The post Interpreting the laws of the US Congress appeared first on OUPblog.

Is privacy dead?

In the 1960s British comedy radio show, Beyond Our Ken, an old codger would, in answer to various questions, wheel out his catchphrase—in a weary, tremulous groan—‘Thirty Five Years!’ I was reminded of this today when I realized that it is exactly 35 years ago that my first book on privacy was published. And how the world has changed since then!

In 1980, personal computers were still in their infancy, and the internet did not exist. There were, of course, genuine concerns about threats to our privacy, but, looking back at my book of that year, they mostly revolved around telephone tapping, surveillance, and unwanted press intrusion. Data protection legislation was embryonic, and the concept of privacy as a human right was little more than a chimera.

Technology has dramatically transformed all that. Today ‘privacy’ seems like a lost cause. New attacks proliferate in a variety of forms including the numerous threats we daily encounter online: monitoring, hacking, email interception, CCTV, big data, cloud computing, location data, biometrics, cybercrime, malware, phishing, identity theft, RFID, GPS, brain imaging, DNA profiling, ‘revenge porn’, drones, and so on. And on. Furthermore, the disquieting revelations by whistle-blower, Edward Snowden, of the extensive surveillance conducted by the National Security Agency (NSA) in the United States continue to shock. In the wake of these revelations, a British parliamentary committee this week described the legal framework surrounding surveillance as ‘unnecessarily complicated’ and ‘lacks transparency.’ It proposed a single law to govern access to private communications by UK agencies.

Our lives are now lived in the unsettling knowledge that almost nothing is private. We have witnessed an alarming explosion of private information through the development of blogs, social networking sites, and other devices of our information age. The methods by which our data are collected, stored, exchanged, and used have changed forever, and with it the very nature of our lives both online and in the real world.

The threats keep coming. Only last week a number of disturbing accounts emerged that sound alarm bells for champions of individual privacy. For example, researchers at Stanford University have developed the means to track mobile devices using battery charge data. Another recent report suggests that investigators are able to determine the physical characteristics of crime suspects from the DNA they leave behind; this could become a powerful new tool in the hands of law enforcement authorities. And police are increasingly equipping their officers with body-worn cameras, raising the question of who has access to their recorded footage.

Data Privacy, by Hebi65. Public domain via Pixabay.

Data Privacy, by Hebi65. Public domain via Pixabay.The disconcerting spread of terrorism across the globe cannot be taken lightly either, but unless individual privacy is to be wholly extinguished, the effective oversight of our security services is essential. In the United States President Obama has promised that the NSA’s bulk collection of Americans’ telephone records would be terminated. He admitted that confidence in the intelligence services had been shaken, and pledged to address the concerns of privacy advocates.

What other weapons do we have in our armoury to arrest, or at least contain the relentless violation of our privacy? There are, amid the gloom, a number of positive glimmers of hope.

One other positive development is that those privacy-invading technologies (PITS) that attack us can be repelled by privacy-enhancing technologies (PATs). These include powerful encryption, communication anonymizers that conceal your online identity (email or IP address) and substitute a non-traceable identity such as a random IP address or pseudonym; shared false online accounts, and the set-up of ISPs that permit users access to their data in order to correct or delete them.

The European Commission, especially since its 1995 Data Protection Directive, and in 2012 its draft European General Data Protection Regulation, has been active in seeking to control the collection, storage, and use of personal data. Strictly speaking, these are not privacy-protection measures, but they do, in effect, curb the market in private information. The European Council is currently considering a new draft proposal that some see as strengthening the safeguarding of personal data.

Another unexpected development is the recent recognition of the ‘right to be forgotten.’ Article 17 of the 2012 draft regulation specifies that individuals have the ‘right to be forgotten and to erasure’ which means that they have the right to have irrelevant or obsolete personal data deleted. In a landmark ruling in 2014 the European Court of Justice upheld the right.

The decision—and its implications—have proved highly controversial largely on the ground that the public interest requires that relevant information remains accessible, especially in relation to elected politicians, public officials, and criminals. Google, while accepting the requirement to delete certain old or irrelevant information, has resisted its wholesale application.

More than one hundred countries have enacted comprehensive data protection legislation, and several others are in the process of doing so. But conspicuous by its absence is the United States which has resisted calls to fall in line with most advanced societies. Nonetheless, only last month the White House released what it called a discussion draft of a bill aimed at giving consumers more control over how data about them are collected. Could this signal a change in attitude towards some form of regulatory control over the massive collection and use of personal information?

The courts—particularly in England and Strasbourg—have reshaped the protection of privacy afforded to individuals under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. In a number of cases, this article has been (very broadly) interpreted to protect a wide-ranging assortment of privacy-invading conduct.

These constructive developments suggest that privacy may not have died. Though, as I say in the book, we must look to both technology and the law to provide effective shelter. Technology generates both the ailment and part of the treatment. And although the law is seldom an adequate tool against a dedicated intruder, the advances in protective software along with the fair information practices adopted by the European Directive, and the laws of several jurisdictions, offer a rational and sound normative framework for the protection of our sensitive information. But it—and the law, ethics, and practice—stand in need of constant review and modification if privacy is to survive as a right to which we can continue to lay claim.

The post Is privacy dead? appeared first on OUPblog.

March 19, 2015

What are this year’s most notable cases in law?

As part of our online event, Unlock Oxford Law, we asked some of our expert authors to identify the most important case in their area of law over the past year. From child slavery to data privacy, we’ve highlighted some of the most groundbreaking and noteworthy cases below.

——————–

“Our choice in terms of the most interesting legal reasoning is Doe v. Nestle USA, Inc., a child slavery case involving cocoa farms in the Ivory Coast. The issue to be decided was whether leading chocolate brands had violated the law of nations by profiting from child labour even if they were not the legal owners of the cocoa farms (and did not control local conditions of labour directly). The court refers to the economic leverage exercised by such brands in the world commodity market, from which it may draw legal inferences. Remarkably, neither territory, nor sovereignty, nor the requirements of foreign policy are part of the legal reasoning used by the court, although they been the focus of private international law’s more familiar approach to the governance of corporate conduct abroad. On the other hand, what the Court is clearly attempting to do is bring the pressure of the legal system down on a point in a global production chain. The leverage of private actors within the market through their brands is acknowledged, as are their power of regulatory capture through lobbying and the triumph of self-regulation. The legal response can be understood in terms of social responsibility, jurisdictional touchdown, victim access to justice, and a political horizon in which the pursuit of profit or market efficiency is balanced against other values.”

— Horatia Muir Watt is Professor at Sciences-Po Paris, where she is Co-Director of the programme ‘Global Governance Studies’ within the Master’s Degree in Economic Law. Diego P. Fernández Arroyo has been professor at the School of Law of Sciences Po in Paris since 2010 and a Global Professor of New York University since 2013. They are the co-editors of Private International Law and Global Governance.

——————–

The legal response can be understood in terms of social responsibility, jurisdictional touchdown, victim access to justice and a political horizon in which the pursuit of profit or market efficiency is balanced against other values.

“There is a pending case at the World Trade Organization that has attracted much attention. It opposes a number of tobacco-producing or exporting countries (and the companies that work in this area) and the government of Australia, which has greatly limited the use of trademarks on tobacco packaging. A panel report is expected later this year and I would not be surprised if the case made it to the Appellate Body towards the end of 2015. Like many of the areas of IP, finding a proper balance between IP protection and other important objectives such as public health is often controversial. Many of the debates have been highly emotional in nature. The approach that the panel and possibly the Appellate Body will take is likely to inform the way in which public health and IP will intersect well beyond the issue of tobacco packaging.

— Daniel Gervais is Professor of Law, Co-Director of the Intellectual Property Program, Vanderbilt University Law School, and editor of Intellectual Property, Trade and Development.

——————–

“The most significant court decision of recent years in the field of data privacy law is the CJEU decision of May 2014 ordering Google to suppress certain internet search results for privacy-related reasons: Case C-131/12, Google Spain v. Agencia Española de Protección de Datos (AEPD) and Mario Costeja González. Popularly—but misleadingly—characterized as establishing a ‘right to be forgotten,’ the decision has been heavily debated across the world. The lines of debate concern the extent to which information about a person’s past life ought to be made easily accessible online, even when the information has diminished relevance for assessing the person’s present life and would be difficult to find offline. Less salient but also important is to what degree online search and retrieval tools should emulate the standards of the (past) offline world, particularly in an era when it is technologically difficult to ‘let bygones be bygones.’

Popularly but misleadingly characterized as establishing a ‘right to be forgotten’, the decision has been heavily debated across the world.

The decision has obvious ramifications for internet governance. While the case is not the first time that the CJEU has fired across the path of internet technology deployment, it is the first time that the Court has fired directly at, and forced changes to, a commonly used internet mechanism. It is also the first time that the Court has fired, albeit more indirectly, at a basic and highly profitable element of the ‘internet economy.’ Moreover, the decision has considerable potential to exacerbate ‘Balkanization’ of the internet by accentuating regional differences in what information can be easily accessed online.”

— Lee Bygrave is Professor in the Norwegian Research Centre for Computers and Law at the University of Oxford. He is the author of Internet Governance by Contract and Data Privacy Law: An International Perspective.

——————–

“One of the most important recent decisions of the Court of Appeal on sentencing is Burinskas [2014] EWCA Crim 334, where the Lord Chief Justice provided detailed practical advice for judges on how to sentence the most serious cases involving ‘dangerous offenders’ following abolition of the notorious sentence of ‘imprisonment for public protection’. The judge must consider, in turn, the provisions and the case law relating to the sentences of ‘discretionary life’, ‘life for the second listed offence’, and the revised ‘extended sentence’. If there is evidence that the defendant is affected by mental disorder then, according to the recent decision in Vowles [2015] EWCA Crim 45, the judge is required to consider a ‘hospital and limitation direction’ and a ‘hospital order with a restriction order’ before imposing a prison sentence. Detailed reasons must always be given at each stage of the decision-making process.”

— Martin Wasik CBE is Professor of Law at Keele University. He was formerly chairman of the Sentencing Advisory Panel (1997-2007) and author of A Practical Approaching to Sentencing.

——————–

“The greatest international investment arbitration case of 2014 was the trio of awards on merits in Yukos v. Russia. It is without doubt the greatest victory for an investor ever: claimants were awarded more than USD 50 billion. However this is not without precedent. The United Nations Compensation Commission has approved awards of more than USD 52 billion and some number crunching could put the contemporary value of the 1872 Alabama award at £150 billion. But Yukos certainly surpasses most recent benchmarks in the amount of compensation, whether for inter-State Tribunals (USD 1/2 billion in the Iran-US Claims Tribunal) or mixed dispute settlement (EUR 1.9 billion in another Yukos case in the ECtHR and USD 1.8 billion plus interest in the ICSID case of Occidental v. Ecuador).

…the decision to create judicial bodies that can award important remedies for breaches of particular rules must be reflective, at least to some extent, of the importance that the particular community attributes to the particular rules.

To look solely at compensation would be an unduly simplistic way of assessing the effectiveness of international Tribunals. Cessation of wrongful conduct and non-repetition may be of greater long-term significance in ensuring compliance with international law; these issues are not central in investment arbitration. Still, the decision to create judicial bodies that can award important remedies for breaches of particular rules must be reflective, at least to some extent, of the importance that the particular community attributes to the particular rules. Yukos, then, shows just how important international investment law is for the contemporary international community.

(Yukos is also, without doubt, the greatest victory for the respondent State ever: the application of the principle of contribution to injury reduced the amount of compensation by 25% to the effect of USD 17 billion. The importance and implications of this aspect of the award are a matter for another discussion.)

— Martins Paparinskis is a Lecturer at University College London. He has previously been a Junior Research Fellow at Merton College, University of Oxford, and a postdoctoral fellow at the New York University. He is the author of The International Minimum Standard and Fair and Equitable Treatment.

——————–

For criminal lawyers, case law is low on their list of priorities. They must first understand new criminal law statutes. The difficulties are increased by a variety of commencement dates. As the effect of a statute cannot—in relation to offences or sentence—be backdated, it is essential that this information is identified. Together with new statutes come a series of codes of practice and circulars dealing with the many issues from the police station through the Court of Appeal. New codes of practice under the Police and Criminal Evidence Act have made significant changes in the requirements on disclosure and circulars have dealt with new out of court procedures to divert suspects from the criminal courts.

But it is case law that has reviewed the law of confiscation. In R v. Ahmed and R v. Fields 2014 UKSC 36, the Supreme Court has assisted in identifying the value of the benefit that has been received by a defendant convicted of crime. The court looks at the individual benefit before assuming that everyone has benefited to the full extent. The court did not take the opportunity to limit the benefit to the actual sums retained by a particular defendant. However, in relation to the assets available to pay a confiscation order, the court has ensured that the State may not benefit more than once from the amount confiscated.

— Anthony Edwards is Senior Partner of TV Edwards, a duty solicitor, a supervisor for the specialist fraud panel, and a higher courts advocate. He is author of Magistrates’ Court Handbook.

Image Credit: “Keys, USS Bowfin” by Joseph Novak. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post What are this year’s most notable cases in law? appeared first on OUPblog.

March 18, 2015

Ossing is bossing

If you know the saying ossing comes to bossing, rest assured that it does not mean the same as ossing is bossing. But you may never have heard either of those phrases, though the verb oss “to try, dare” is one of the favorites of English dialectology. The regular users of the Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE, very much in the spirit of this post) find in it hundreds of amusing words and discover that they can be puzzled tourists in their own land. But Americans hardly ever think that, even if a job search transfers them from Maine to Alabama, they will not be able to communicate with the natives. However “funny,” their language is still English. This is not the case in most West European countries, with their ancient, mutually unintelligible dialects. While leafing through Joseph Wright’s English Dialect Dictionary, one wonders: “Is it indeed a dictionary of English”? The origin of even the most common words is often tricky, but at least it can be looked up somewhere. The etymology of regional words poses graver problems. Dictionaries seldom include them, while special articles and books are hard to dig up, and who, except a handful of lexicographers, ever does the digging?

Oss attracted the attention of a few timid specialists and a handful of self-confident amateurs. Its history can also be found in Thomas Hallam’s 1885 booklet. Unsurprisingly, as journalists like to say, linguists are more interested in dialectal words that have old ancestors. One of such aristocrats is nesh “soft.” Its Old English form has come down to us, and it has a cognate even in Gothic. Not every item in our regional speech is so fortunate. Oss, current over a large territory of England, remains partly (but only partly) obscure. Among those who dealt with this verb we find Henry Bradley and Walter W. Skeat (which already lends those items glamor), and, of course, it appears in Wright’s dictionary.

Joseph Wright reproduces the following scene from a Sunday school in Cheshire: “Why did Noah go into the ark?” “Please, teacher, because God was ossin’ for t’ drown the world.”

Joseph Wright reproduces the following scene from a Sunday school in Cheshire: “Why did Noah go into the ark?” “Please, teacher, because God was ossin’ for t’ drown the world.”Several forms of oss have been recorded, including ost ~ aust, hoss, and awse ~ orse. Final t in ost ~ aust should probably be dismissed as excrescent (compare whilst, against, amongst, and many other words in English and German that today end in -st where one expects the historically legitimate s). Although awse and orse look like spelling variants of oss, they point to a long vowel in an r-less dialect. Hoss is closer to oss, but we wonder what to do with initial h: either oss is hoss with its h dropped or hoss is oss with an h added for the sake of gentility, as in the (h)atmosphere of the (h)air. The senses of oss are rather numerous. They include “to try,” “to be about to do something” (also occurring in awse about), “to shape, frame something; design; intend,” and, most unexpectedly, “to prophesy,” which happens to be the oldest one we know. It turned up in the fifteenth century.

Those who tried to discover the verb’s origin often said it is perfectly clear and undoubtedly, but nothing is perfectly clear about the history of oss. As usual, I’ll ignore some hopeless suggestions (oss derived from Basque, oss being a variant of ease, and the like). In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, most researchers believed that oss is a borrowing of either Welsh osio or French oser, both meaning “to try.” Hensleigh Wedgwood had a knack for finding words from unrelated languages that sounded alike and meant almost the same. This ability irritated some of his opponents, for, though his examples often violated phonetic laws, the forms he cited were invariably correct. Thus, he discovered Finnish osata “to aim right, strike the mark, to be able to do, to know the way” (so in 1872) and cited a close Estonian cognate. However, Wedgwood stopped short of offering an etymology and said nothing about Finnish. He stated that, in dealing with the English and the Welsh verbs, we “undoubtedly” have the same word but could not decide which language was the borrower and which the lender. He also had reservations about the French source, for “oss belongs so completely to the popular part of the language that it is very unlikely to have had a French derivation.”

Nine years after Wedgwood, C. B. West, a correspondent to Manchester Notes and Queries, made the following populist statement: “Anyone acquainted with the northern peasant knows his habit of stupidly playing with words and applying to them meanings they will not bear. He is in this respect like the calves which he tends, and is half-conscious of the fact that he is a fool though he persists in his folly. I can liken this habit of intentional absurdity best to that of the Irish peasant who so often perpetrates ‘bulls.’” From such heights of societal and linguistic sophistication Mr. West ridiculed another correspondent who had suggested a French source of oss: “I can only say when our Lancashire peasants begin talking French, the schoolmaster’s ‘occupation will be gone.’” As could be expected, he had his own theory: “My reply is… confident that the word awse is derived from the animal horse.” No details are given. I am aware of an old story about “hoss-men,” allegedly inhabiting Lancashire, but I’m not sure that it has anything to do with the etymology of oss and skip it.

Despite C. B. West’s incredible meanness, his reasoning was not quite unlike Wedgwood’s: since the word oss belongs to popular speech, it is unlikely to have come from French. This argument does not go too far, but, as Bradley made it clear in 1883, oss could hardly derive from oser, for, if such were the case, the consonant in it would have been z, not s. His conclusion is irrefutable. But the Welsh hypothesis inspires no confidence either, because the English word, unknown to the Standard, is known too far from the Welsh border. The opinion favored in the past by the best-informed Celtologists, namely that the Welsh verb was borrowed from English, must be correct.

Ossing comes to bossing.

Ossing comes to bossing.Enter Comestor Oxoniensis. Alas, I don’t know who hid under this pseudonym and can only guess that he borrowed his signature from the famous Petrus Comestor. Whoever this Oxonian Devourer (of learning) might be, his contributions mainly or perhaps exclusively to Notes and Queries in 1902-1903 are excellent. This gentleman offered a good conjecture. He cited Old Engl. halsian (long a in the root, as a in Modern Engl. spa) “to adjure; swear; entreat; exorcise.” The noun formed from this verb meant “exorcism; augury, divination; entreaty.” Halse still appears in the largest dictionaries of Modern English. The group -al- must have become -aw- (as in talk, walk, chalk). It follows that hawse can be a legitimate continuation of halsian. The Devourer was in trouble with the derivation of oss (no h- and a short vowel), and this part of his reconstruction is less convincing, but he seems to have hit the nail on the head with regard to the etymon of at least one variant of the verb. Etymology is an anonymous science, and it grieves me that I cannot celebrate the real name of the discoverer. The first edition of the OED offered no hypothesis about the origin of oss, but the great Middle English Dictionary accepted, though with a question mark, halsian as its source, and Oxford followed suit.

And now back to the saying in the title of this post. To most it means “trying is the best way to achievement” (make an effort, and you will be a boss). But boss is a well-known dialectal word for “kiss,” so that the saying ossing comes to bossing means “be bold, and you will kiss your beloved.” Those interested in the subject of osculation will find some revealing data in my old post on kiss and in Nyrop’s book mentioned in it.

Image credits: (1) Noah’s Ark. East Anglia England Norfolk [perhaps]. illumination about 1190; written about 1490. Getty Open Content Program. The Getty. (2) Kissing Black-tailed Prairie Dogs. Photo by Brocken Inaglory (Photograph edited by Vassil). CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Ossing is bossing appeared first on OUPblog.

Virginia Woolf in the twenty-first century

As we approach 26 March 2015, the centenary of the publication of Virginia Woolf’s first novel, The Voyage Out, it seems apposite to consider how her writing resonates in the twenty-first century. In the performing and filmic arts, there certainly seems to be something lupine in the air. Choreographer Wayne McGregor’s new ballet, Woolf Works, opens at the Royal Opera House this spring and draws on Mrs Dalloway, Orlando, and The Waves. Ben Duke’s dance-theatre piece, Like Rabbits, based on Woolf’s short story, Lappin and Lapinova is currently on tour. Life in Squares, a BBC mini-series focused on Virginia’s relationship with her sister Vanessa was filmed last autumn on location at Charleston. At the same time, I’m told, casting was taking place for a film version of Flush.

But how do her feminist essays, A Room of One’s Own (1929) and Three Guineas (1938), read in 2015? While both of these essays started off as talks given by Woolf to audiences of young women, their fortunes have been quite divergent. A Room of One’s Own has become a feminist classic, its title and central tropes (e.g. Shakespeare’s sister) in turn inspiring their own feminist afterlives. It outlines the history of economic, spatial and ideological constraints on women’s artistry at the same time as it produces the first literary history of women. Three Guineas (1938), Woolf’s feminist, pacifist, anti-fascist essay, has had a more uneven reception. It emerges out of a particular historical moment — the rise of fascism on the continent and in Britain — and a particular conflict: the Spanish Civil War. But Woolf’s dissection of her own militarized, monetized, patriarchal society is easily translated to our own. In thinking about whether women, as outsiders, might be best placed to oppose war she reveals the systemic and structural inequalities in public life. Each issue she raises seems uncannily prescient: access to higher education and the role of the university as a democratic space of intellectual freedom; the number of women in public life; violence against women and girls; women in the church; working motherhood; pay inequality.

Virginia Woolf. By George Charles Beresford. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Virginia Woolf. By George Charles Beresford. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Editing Woolf in the twenty-first century means annotating her writing in ways that reveal her wide-ranging engagement with her contemporary moment (and its literary and political histories). It means framing and introducing those references and contexts that have faded from view, such as the photographs she included of public, male figures instantly recognizable to her readers in the 1930s (and restored to their original position in this new edition). Decked out in full regalia, Stanley Baldwin, Baden Powell, Gordon Hewart and Cosmo Gordon Lang may no longer be familiar to general readers in 2015 but as images of the perpetuation of masculine wealth and privilege through spectacle and tradition they need no translation. As Woolf writes in Three Guineas: ‘we listen to the voices of the past […] Things repeat themselves it seems.’

The post Virginia Woolf in the twenty-first century appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers