Oxford University Press's Blog, page 685

March 23, 2015

Sentencing terrorists: key principles

In July 2014 Yusuf Sarwar and his associate, Mohammed Ahmed, both aged 22, pleaded guilty to conduct in preparation of terrorist acts, contrary to s5 of the Terrorism Act. Sarwar was given an extended sentence (for ‘dangerous’ offenders under s226A of the Criminal Justice Act 2013) comprising 12 years and eight months custody, plus a 5 year extension to his period of release on licence. The pair had fought in Syria for a group affiliated with al-Qaeda. Traces of explosives were found on their clothes. His mother, Majida Sarwar, had told the police about a letter from her son in which he said he had gone to “do jihad” in Syria. The police subsequently arrested her son when he returned to the UK. In interviews Mrs Sarwar said she felt the police had betrayed her: “Other mothers are not going to come forward to the police. Nobody’s going to hand their son in, knowing that they’re going to be behind bars. The sentencing is harsh.” The family have said that they will be appealing the sentence.

In Belgium Jejoen Bontinck’s father made national headlines by risking his own life to travel twice to the Syrian war zone to find his son, then aged 18, who was arrested when he did return to Belgium. The trial on terrorism charges of leaders of Sharia4Belgium took place in February in Antwerp with Jejoen Bontinck as a key witness who himself received a suspended sentence of 40 months. The court accepted Bontinck’s claim that he was not actively fighting but an ambulance driver. However, the leader of the group received 18 years and others received sentences from 3 to 15 years. In France Flavien Moreau was sentenced to 7 years and claimed to have spent only 2 weeks in Syria although he was arrested while seeking to return there.

These developments raise several issues. Politicians have generally praised the courts for dealing severely with returned terrorists. The Immigration and Security Minister, James Brokenshire MP, said of Sarwar’s sentence: “This case clearly demonstrates the government’s clear message that people who commit, plan and support acts of terror abroad will face justice when they come back to the UK.” In the UK the main sentencing framework is retributivist so that justice is what is deserved for the seriousness of the offending. Deciding whether Sarwar’s sentence was harsh is, however, no easy matter. Suffice it to say that, whilst the outcome may be deterrent, that should not be the guiding principle but may be considered alongside the goals of punishment and incapacitation for public protection. The judge in this case noted that Sarwar and Ahmed were deeply committed to extremism and with a great deal of purpose, persistence, and determination had embarked on a course intended to commit acts of terrorism. Sarwar was sentenced last December and, the judge argued, the sentence reflects the seriousness of the offence and risk to the public: “The court will not shrink from its duty where, as here, a grave crime has been committed.”

There is no Sentencing Council Guideline on terrorist offences and so guidance is via case law. Some other recent cases suggest that Sarwar’s sentence is not out of line. For example, Imran Khawaja, aged 27, received an extended sentence in Woolwich Crown Court on 6 February 2015, with 12 years in custody and 5 years for the extended licence term. He travelled to Syria for the purposes of jihad against the wishes of his immediate family who urged him to return. In Syria he received combat training including weapons training and participated in promotional jihadist videos to encourage UK Muslims to join him in jihad, including one showing a severed head. While in Syria his sister repeatedly urged him to return to the UK but he made it clear he did not intend to do so. However, he did eventually return, unsuccessfully attempting to conceal his arrival by reporting his death on social media sites. He was apprehended and charged with offences connected with terrorism, the judge noting in this case that a number of sentencing principles in terrorist cases had emerged from cases considered by the Court of Appeal.

In R v F [2007] QB 960 the court made clear that it made no difference to the seriousness of the offence whether the intended acts of terrorism were to take place in the UK or abroad. In R v Khan [2013] EWCA 468 the Court of Appeal stressed that the element of culpability will be very high in most cases of terrorism and the purpose of sentencing for the most serious terrorist offences will be to punish, deter and incapacitate; the starting point for the inchoate offence will be the sentence that would have been imposed if the objective had been achieved. However, Lord Phillips CJ in R v Rahman and Mohammed [2009] 1 CAR (S) 70 observed that:

“It is true that terrorist acts are usually extremely serious and that sentences for terrorist offences should reflect the need to deter others. Care must, however, be taken to ensure that the sentence is not disproportionate to the facts of the particular offence… If sentences are imposed that are more severe than the particular circumstances of the case warrant this will be likely to inflame rather than deter extremism…”

In Khawaja’s case the Court was not convinced he actually took part in the fighting, although he was extremely close to the combat zones and took an active part in assisting those involved in the fighting. It was also clear that he intended to remain an active member of the organisation on his return to the UK and that he posed a significant risk of causing serious harm to the public.

These cases have highlighted the issue of whether the radicalisation of young men and women is best countered by the use of tough sentencing or by other means, such as the development of educative programmes in schools or measures to encourage the cooperation of parents. Sarwar’s mother clearly felt that a reduced sentence would have been more just given her cooperation with the police. To do that might be a pragmatic policy decision but it is very problematic in terms of sentencing law. The courts are able to take personal mitigation – including the impact on family – into account but do not have to do so and they are extremely reluctant when the offending is very serious. In some circumstances – for example when the child of a prisoner is taken into care – the lack of ‘mercy’ might mean the impact of the sentence on the prisoner is very severe and not commensurate with seriousness of the offending.

However, there are also compelling arguments against using sentencing law for political and social purposes, not least because of principles of equity. If two defendants have committed similar crimes the outcome of the case should not depend on the impact on relatives or indeed the efforts of their relatives to prevent offending, but rather they should be assessed on the degree of culpability and seriousness of the offence. On desert theory the actions of the offender is what should be judged and punished if, as in the above cases, the defendants are adults of full capacity. Sarwar, for example, was well educated and had been an undergraduate student at Birmingham City University.

The news in February that three young girls, aged 15 and 16, had travelled to Turkey to join jihadists in the so-called Islamic State has highlighted the issue as to whether parents should themselves go to try and persuade their sons or daughters to return home or the police should be more proactive. In this case the police did have concerns about the girls’ contacts with others in Syria but a letter to the parents did not reach them because it was given (only) to the girls who failed to pass it on.

Another option is to impose bans on foreign travel with powers to confiscate passports. The Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015, passed in February, strengthened temporary restrictions on travel for persons where there are reasonable grounds to suspect a person is leaving the UK for purposes related to involvement in terrorist activity outside the UK. Temporary Exclusion Orders will also prevent re-entry to the UK for those already abroad. Applications for return can be made subject to risk assessment and obligations can be imposed on return, for example, participation in a de-radicalisation programme. In some circumstances this might be a way for parents to achieve the safe return of their sons and daughters. Similar legislation has been introduced in France.

There are no easy answers to the issues raised by these cases. They highlight the problems European states face in reconciling civil liberties and freedoms with the continuing threat of terrorism here, demonstrated by the attacks in France, Belgium, and Denmark this year and the active involvement of UK nationals in the murder of hostages overseas.

Headline image credit: Destination Damascus. © gmutlu via iStock.

The post Sentencing terrorists: key principles appeared first on OUPblog.

The death of a friend: Queen Elizabeth I, bereavement, and grief

On 25 February 1603, Queen Elizabeth I’ s cousin and friend – Katherine Howard, the countess of Nottingham – died. Although Katherine had been ill for some time, her death hit the queen very hard; indeed one observer wrote that she took the loss “muche more heavyly” than did Katherine’s husband, the Charles, Earl of Nottingham. The queen’s grief was unsurprising, for Elizabeth had known the countess longer than almost anyone else alive at that time. While still a child, Katherine Carey (as she then was) had entered Elizabeth’s household at Hatfield; a few years later, on 3 January 1559, though aged only about twelve, Katherine became one of the new queen’s maids of honour and participated in the coronation ceremonials, twelve days afterwards. What is more, Katherine was close kin to the queen. Her paternal grandmother was Mary Boleyn (the sister of the more famous Anne) and her father was the queen’s favourite male cousin Henry, Lord Hunsdon.

Although Elizabeth has a reputation for opposing her maids’ marriages – undeservedly in my opinion – she had welcomed Katherine’s marriage in July 1563 to another of her cousins on Anne Boleyn’s side, Charles Howard, son of Baron Howard of Effingham. Like a number of other favoured women, Katherine did not leave the queen’s service after her marriage, even when she was pregnant. No longer a maid, she became a gentlewoman of the privy chamber, often taking charge of the queen’s clothes and gifts of jewels. Later, she was promoted to the position of lady carver, with the task of receiving the queen’s food, laying it out on plates and presiding over the table. From 1572 onwards Katherine had the position of chief lady of the privy chamber, and in April 1598 she was recorded as being “grome of the Stoole”, taking responsibility for the royal chamber pot. As such she was one of a tiny number of people who would have had any physical contact with the Queen. Elizabeth liked to have her Boleyn relatives within the inner sanctum of the court, and Katherine was no exception. Kinship ties were always valued in the sixteenth-century, and Elizabeth believed that she could count upon the loyalty and devotion of close kin without royal blood.

Statue of Queen Elizabeth, London, by Mike Peel. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Statue of Queen Elizabeth, London, by Mike Peel. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Katherine’s husband Charles was also an intimate of the queen. His father had helped to protect the young Elizabeth during her sister’s reign, and on her accession Charles was appointed a gentleman of the privy chamber. Though slow to be granted important office, he nonetheless benefitted from his wife’s intimate relationship with the queen. In 1575 he was admitted to the elite order of the Garter, and entered the privy council in 1584, when he achieved major political status as Lord Chamberlain. In May 1585, he exchanged a household role for a martial one, when he was appointed Lord High Admiral. Although relatively inexperienced in naval matters, Howard successfully presided over the fleet during the crisis of the Spanish Armada in 1588, and saw active service in the 1596 Cadiz expedition. As a reward for the latter, he was elevated to the ancient earldom of Nottingham in October the following year. This title placed him as the second highest peer of the realm and most importantly meant that he had ceremonial precedence over his rival, Robert, 2nd Earl of Essex. Matters became more complicated when, to mollify a disaffected Essex, Elizabeth appointed him Earl Marshal, thus leap-frogging Nottingham in precedence, From then on the two men were enemies.

As far as we know, Katherine stayed outside these court rivalries. Nonetheless, an influential story was fabricated later in the seventeenth century, alleging that on her deathbed she confessed her part in the eventual execution of the ill-fated Essex. According to this account, Queen Elizabeth had promised the earl that if he ever incurred her anger, he should return to her a ring which she had given him; receiving this token, she would forgive him any transgression. From his prison cell in the Tower of London in February 1601, the story continues, the condemned earl desperately tried to get the ring to the queen, but it came into Katherine’s possession and she deliberately withheld it from her mistress. News of this supposedly reached Elizabeth two years later, when Katherine was dying, and her last words to the countess were said to be: “God may forgive you, Madam, but I never shall”. A romantic myth, with no foundation of truth, the ring story appeared as a fact on film and even in a devotional Christian text printed in 2007.

What is indisputably true is that after hearing of Katherine’s death, the queen fell into a deep melancholy and barely left her private rooms, except to walk in her privy gardens. Apart from grief at the loss of a friend, it seems that Elizabeth also felt the intimations of her own mortality. A Catholic informant reported that “The Queen loved the countess well, and hath much lamented her death, remaining ever since in a deep melancholy that she must die herself, and complaineth of many infirmities wherewith she seemeth suddenly to be overtaken.” Katherine’s brother Robert Carey, likewise found Elizabeth to be in “a melancholy humour”; when she talked to him at length about her sadness and ’indisposition’, he wrote in his memoirs, “she fetched not so few as forty or fifty great sighs”, an unusual occurrence “for in all my lifetime before, I never knew her fetch a sigh, but when the Queen of Scots was beheaded.”

The day after the audience with Carey – Sunday 12 March – Elizabeth refused to leave her room to go to chapel, but lay on cushions in the privy chamber “hard by the closet door” so she could hear the service. As a Venetian ambassador observed, the queen allows “grief to overcome her strength.” He was right, for so began the physical decline that ended in the queen’s death during the early hours of 24 March.

The post The death of a friend: Queen Elizabeth I, bereavement, and grief appeared first on OUPblog.

March 22, 2015

Leaving New York

In the 1940s and early ’50s, the avant-garde art world of New York was a small, clubby place, similar in many ways to the tight (and equally contentious) circle of the New York intelligentsia. Many artists rented cheap downtown Manhattan industrial loft spaces with rudimentary plumbing and heat. They knew each other because their numbers were small and their problems were shared. Chief among them was grinding poverty and the sad fact that hardly anyone was selling work.

While Parisian artists gathered in cafés, the New Yorkers initially huddled around 5-cent cups of coffee in dreary cafeterias where management clamped down on people who occupied seats for hours without buying a meal. The founding of the Club as an artists’ meeting place in late 1949 changed everything. Together with the nearby Cedar Tavern—drab, but alive with conversation and argument fueled by beer and Scotch—the Club became the place to go for fellowship after spending the day alone in the studio. Friday night talks and panel discussions by significant figures in the visual and performing arts constituted an ad hoc university for many Club members whose formal education was limited. Beginning in the mid-’50s, the Five Spot Café offered another convivial alternative for artists, poets, musicians, and dancers to hang out and perhaps catch a performance by one of the masters of modern jazz.

But by 1960, this sense of community had splintered, in part because several leading artists had left Manhattan. Philip Guston had moved upstate to Woodstock; Willem de Kooning and Larry Rivers lived on Long Island; Franz Kline had bought a house in Provincetown, Massachusetts; Joan Mitchell had decamped for Paris.

Money was another divisive aspect. Painter Mercedes Matter remarked that she heard artists “talking about galleries over their bourbons instead of about art as before, over their beers.” There was now a huge gulf between the prices a famous artist could command and those of lesser-known painters. While de Kooning’s sold-out show at the Sidney Janis Gallery in May 1959 netted him about $80,000 (more than $600,000 in today’s money), Fairfield Porter’s sales for the entire year at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery totaled less than $3,000.

Most devastatingly, galleries and museums were turning their attention from the emotional heat of Abstract Expressionism to the cool styles of Pop Art and Minimalism. Art critics sniped that the freely brushed, energetic style born in the 1940s had hardened into formula—either a caricature of itself (a splattered canvas painted in a frenzy) or an earnest, lifeless imitation (drip here, slash there). Such was the rumbling of negativity that Art News magazine convened eighteen artists to discuss the issue and published edited versions of their remarks in the Summer and September 1959 issues. As the critic Dore Ashton noted, “The New York School as such had vanished and what emerged . . . was a scattering of isolated individualists who continued to paint.”

In 1960, Grace Hartigan—whose richly coloristic paintings combined energetic brushwork with hints of recognizable imagery—was still riding the last wave of Abstract Expressionism, the subject of flattering articles in popular magazines as well as astute reviews in art journals. That year, she fell in love with one of her collectors, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University. She married him in 1961 and moved to Baltimore, Maryland, dreaming of creating an equivalent to her beloved New York gathering places—a salon where the city’s artists, musicians, poets, and scientists would exchange ideas and enjoy each other’s company.

This was not to be; Baltimore was a sleepy backwater with no contemporary arts scene to speak of. The poet Barbara Guest privately rued that her friend was making a big mistake, “disastrous for a career at its peak.” The New York art scene, Guest said later, “never forgives.” Indeed—despite the efforts of her supportive New York dealer, Martha Jackson—Hartigan’s sales began to dry up and reviewers were largely dismissive of her new work. In succeeding decades, as her styles and subject matter changed, she would cycle through several other New York galleries. But her moment in the sun was over.

During the next forty-seven years of her life, Hartigan engaged in a protracted dialogue with her favorite city. While Manhattan rents were zooming upward, she rented an inexpensive studio space in Baltimore. “Eat your heart out, New York!” she crowed. Yet she lamented her remoteness from the art capital that made international reputations possible. Artists need to be loved, she told an interviewer, “and to have rejection, silence, and indifference was very difficult.” As late as 1987, she called her move to Baltimore “the disaster of my life.”

At the same time, Hartigan realized that her queen-bee reputation in Baltimore—where she was a celebrated teacher at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA)—would no longer be possible in Manhattan’s contemporary art world. Over the years, she offered her students seasoned advice about the wisdom of trying to make it in New York. While she continued to believe that working there was essential to anyone aspiring to a major career, she admitted that an artist can have a good life elsewhere. But she cannily hedged her bets—in the mid-’80s, she acquired a pied-à-terre in Greenwich Village, a few blocks from her artistic beginnings on Hester Street.

Image Credit: “Grace Hartigan: Modern Cycle, 1967.” Photo by Smithsonian American Art Museum. CC by NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Leaving New York appeared first on OUPblog.

Counting party members and why party members count

In mid-January 2015, British newspapers suddenly developed a keen interest in Green Party membership. A headline from The Independent proclaimed “Greens get new member every 10 seconds to surge past UKIP’s membership numbers ahead of general election”; other articles compared the membership sizes of the UK’s parties, calculating where Green Party membership stood in relation to that of UKIP (ahead of it, as of January 2015), or of the Liberal Democrats (slightly behind). What triggered this sudden flurry of media attention, and the related jump in Green Party enrollment?

The immediate cause was the broadcasters’ decision to exclude the Green Party from the pre-election leaders’ debate, even though UKIP would be included for the first time. This decision was buttressed by the official communications regulator, Ofcom, which cited electoral performance and opinion poll support in ruling that UKIP was a major party for purposes of allocating party political broadcast, but the Greens weren’t. In response, the Green Party’s leader, Natalie Bennett, pointed to the party’s rapidly increasing membership as a sign that her party enjoyed popular support equal to that of UKIP – at least in membership terms. While the rising membership numbers did not immediately persuade the broadcasters to change their stance, the Green Party gained strong favorable publicity from these well publicized figures – and it gained a large number of new members.

Ard! 50/365 by Blue Square Thing. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr

Ard! 50/365 by Blue Square Thing. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr This raises the question: what are party members good for? This episode with the UK Green Party shows that one answer is legitimacy. Parties can point to their membership rolls as evidence that they enjoy strong support from real people. (Of course, membership numbers can work the other way as well, with declining numbers seen as a sign of popular disaffection. Indeed, the three largest British parties have enrollments today that are significantly smaller than they were at the beginning of the 1990s, and this fact is often cited as evidence of a more general loss of popular trust in political parties.)

But party members can help their parties as more than just numerical tokens of popular support. They often are enlisted as volunteers, and may do the unglamorous but effective campaign work that helps their party to mobilize its voters on election day. Some party members make donations in addition to their dues. Party members can help to put a more human face on party politics when they let friends and family members know about their partisan leanings; in this sense, they act as ambassadors for their parties. In many parties, members are important in other ways as well. Most strikingly, they sometimes play politically significant roles in picking the party candidates and party leaders. That is certainly true in Britain today. Indeed, whichever of Britain’s nationwide parties participate in the leadership debates this spring — whether two parties (Labour and Conservative) or five (Labour, Conservative, LibDems, UKIP, and Greens) – one thing all the party leaders will have in common is that they were selected for their jobs by a ballot of their respective party’s dues-paying members. For all of these reasons, even if parties don’t have a lot of members, those members count for a lot.

The post Counting party members and why party members count appeared first on OUPblog.

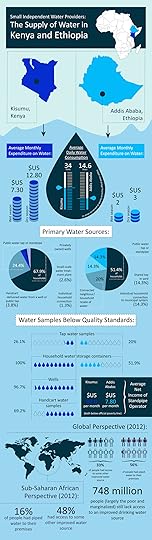

Independent water providers in Kisumu and Addis Ababa

In order to build the future we want, we must consider the part that water plays in our ecosystems, urbanization, industry, energy, and agriculture. In recognition of this challenge, the United Nations celebrates World Water Day on 22 March each year, including this year’s theme: ‘Water and Sustainable Development’.

Sustainable access to safe drinking water is a fundamental human right, yet in 2012, 748 million people were still living without access to an improved source of drinking water. The proper regulation of small water vendors in Kenya and Ethiopia could result in increased access to water for the poor. With data drawn from “Small Independent Water Providers: Their Position in the Regulatory Framework for the Supply of Water in Kenya and Ethiopia” in the Journal of Environmental Law, the following infographic illustrates the crucial role that independent water providers play in the supply of water to Kisumu, Kenya and Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Download a pdf or jpg of the infographic.

Headline image credit: Truck carrying straw in Kisumu, Nyanza, Kenya. Photo by William Warby. CC BY 2.0 via wwarby Flickr.

The post Independent water providers in Kisumu and Addis Ababa appeared first on OUPblog.

Changing conceptions of rights to water?

What do we really mean when we talk about a right to water? A human right to water is a cornerstone of a democratic society. What form that right should take is hotly debated.

Recently 1,884,790 European Union (EU) citizens have signed a petition that asks the EU institutions to pass legislation which recognizes a human right to water, and which declares water to be a public good not a commodity.

But a right to water has various facets. It includes rights of economic operators, such as power stations and farmers to abstract water from rivers, lakes, and groundwater sources. The conundrum here is that an individual human right to water, including a right to drinking water and sanitation, can be in conflict with the rights of economic operators to water. More importantly such human rights to water may be in conflict with a right to water of the environment itself. The natural environment needs water to sustain important features such as habitats that support a wide range of animals and plants.

There is a growing trend under the label of ‘environmental stewardship’ that prompts us to think not in terms of trade-offs between different claims to water, but to change how we think about what a right to water entails. Environmental stewardship means that human uses of water – by individual citizens, consumers and economic operators – should pay greater attention to the needs of the natural environment itself for water. This raises some thorny issues that go to the heart of how we think about fundamental rights in contemporary democracies. Should we abolish the possibility to own natural sources, such as water and thus limit the scope of private property rights? Should we develop ideas of collective property, which involves state ownership of natural resources exercised on behalf of citizens? Should we simply qualify existing private property and administrative rights to water through stewardship practices? It is the latter approach that is currently mainly applied in various countries. How does this work? Water law can impose specific legal duties, for instance on economic operators to use water efficiently, in order to promote stewardship practices. Whether this will be of any consequence, however, depends on what those who are regulated by the legal framework think and do.

A recent study therefore explored how English farmers think about a right to water and its qualification through stewardship practices. The study found that three key factors shape what a right to water means to farmers.

First, the institutional-legal framework that regulates how much water farmers can abstract through licences issued by the Environment Agency defines the scope of a right to water.

Second – and this struck us as particularly interesting – not just the law and the institutions through which water rights are implemented matter, but also how natural space is organized. The characteristics of farms and catchments themselves, in particular whether they facilitated the sharing of water between different users, influenced how farmers thought about a right to water. Water sharing could enable stewardship practices of efficient water use that qualified conventional notions of individual economic rights to water.

Irrigation. CC0 via Pixabay.

Irrigation. CC0 via Pixabay. Third – and this touches upon key debates about the ‘green economy’ – the economic context in which rights to water are exercised has a bearing on how ideas about rights to water become qualified by environmental stewardship.

In particular ‘green’ production and consumption standards shape how farmers think about a right to water. There are a range of standards that have been developed by the farming industry, independent certification bodies, such as the Soil Association, as well as manufacturers of food stuffs to whom farmers sell their produce and supermarkets. These standards prompt farmers to consider the impact of their water use on the natural environment. For instance, the Red Tractor standard for potatoes asks farmers to think of water use in terms of a strategic plan of environmental management for the farm, which also addresses ‘accurate irrigation scheduling’, ‘the use of soil moisture and water application technology’, as well as ‘regular and even watering’. These are voluntary standards, but they matter. They can render farmers’ practices in relation to water stewardship more transparent and thus also promote accountability for the use of natural resources.

Supermarket standards were considered as most influential by farmers, particularly in water scarce areas of the United Kingdom such as East Anglia. But these standards revealed an interesting tension between their economic and environmental facets.

Somehow paradoxically green consumption and production standards could also reinforce significant water use by farmers, such as spray irrigation in order to achieve good product appearance. For instance, some manufacturers of crisps seek to reduce the impact on water use of the crops they source for their products. But farmers who want to sell their potato crops to crisp manufacturers still have to achieve ‘good skin finish’, because ‘nobody wants scabby potatoes’!

So, next time you go grocery shopping ask how your consumer choice shapes a right to water.

Headline image credit: Water. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Changing conceptions of rights to water? appeared first on OUPblog.

Thinking about how we think about morality

Morality is a funny thing. On the one hand, it stands as a normative boundary – a barrier between us and the evils that threaten our lives and humanity. It protects us from the darkness, both outside and within ourselves. It structures and guides our conception of what it is to be good (decent, honorable, honest, compassionate) and to live well.

On the other hand, morality breeds intolerance. After all, if something is morally wrong to do, then we ought not to tolerate its being done. Living morally requires denying the darkness. It requires cultivating virtue and living in alignment with our moral values and principles. Anything that threatens this – divergent ideas, values, practices, or people – must therefore be ignored or challenged; or worse, sanctioned, punished, destroyed.

This wouldn’t be problematic if we agreed on our moral values/principles, on what the “good life” entailed – but, clearly, we don’t. Indeed, the world stands in stark disagreement about what is decent and honorable vs. vile and repugnant, who deserves compassion, what counts as fair, etc. Conflicts are frequently sparked by the clash of divergent moral perspectives. While it is easy to sit in judgment of those who shove “their morality” down the throats of others, it would nonetheless be irresponsible to pretend that this is not precisely what morality is about – the fight against evil, against corruption, injustice, inhumanity, degradation, and impurity.

We seem inclined to forget that morality is hard. I don’t just mean that it is hard to be a good person, to live up to one’s values/principles (though it is!). I also mean that it is hard to know what being a good person requires or which values/principles are the ones with which we should align ourselves. Indeed, getting morality right may be as daunting a task as understanding the physical nature of the universe itself.

Clouds, by theaucitron. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr

Clouds, by theaucitron. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr This difficulty is largely hidden from us by the forces of socialization and the socio-cultural frameworks to which we belong. We are unable to see how fragile our grasp of morality really is, how little we understand about how we ought to live. We forge ahead thinking that our moral perspective is the right perspective – or, at least, that it is better than other perspectives. Such entrenchment not only makes conflict more likely, but it also makes morally significant change difficult to achieve.

And yet, morally significant change must happen. Interaction and exchange between diverse cultures has increased to the point where we simply must adapt and adjust our moral perspectives; we must be open to new ideas, ways of thinking, values and ideals. This means that if we want to get closer to the truth, we must be flexible, receptive, and willing to consider alternatives. In other words, morality requires a contradiction – to be both inflexible and flexible, willing to stand firm on our principles and fight injustice and immorality, yet also willing to listen to the “foreign” other, to adapt, adjust, and amend our beliefs.

How can we navigate these treacherous waters? Studies being conducted in my lab and elsewhere suggest at least one strategy. Over the last 10 years, my colleagues and I have studied how people think about morality and how this predicts their tolerance for values and practices different from their own. Specifically, we asked people to identify their moral values/practices and then explain what they believe grounds them – i.e., whether they were grounded “objectively” (by mind-independent facts impervious to individual or cultural beliefs, desires, attitudes, customs) or “non-objectively” (by individual/cultural beliefs, desires, attitudes, customs). One of the most interesting things we’ve discovered thus far is that most people are meta-ethical pluralists. That is, they view some moral values/practices as objective, while viewing others as non-objective. Not surprisingly, they are also much less tolerant of divergence when it involves objectively grounded moral values/practices than when it involves those non-objectively grounded. When we examined the difference between people’s objective vs. non-objective moral values/practices more closely, we realized that the non-objectively grounded values/practices involved issues currently being heavily debated, with strong advocates on both sides – i.e., areas of potential moral change.

“Living morally requires denying the darkness”

Why does this matter? Because, this suggests that people’s pluralism is not simply a byproduct of some sort of confusion, but is instead an adaptive pragmatic strategy adopted to accommodate morality’s contradiction.

While people don’t feel less strongly about these values/practices, they are nonetheless unwilling to “close them down” in the way that objectivity requires. This was evident by how they responded to objective vs. non-objective moral divergence. They viewed the former as “transgressions” not to be tolerated, but instead sanctioned/disavowed/punished, while viewing the latter as acceptable, to be if not embraced, then at least tolerated, discussed, and debated.

We see examples of this around us all the time. One that stands out very clearly for me was an on-campus talk given by Jonathan Safran Foer, author of Eating Animals, during which he clearly articulated why our mass production of animals for consumption was a serious moral crisis (indeed, the crisis of the 21st century) while also stating that people must be allowed to decide what to do about it for themselves. Here, once again, we see the contradiction. While we are doing something on a massive scale that we have good reason to believe is unethical, we cannot simply force people to abandon their own values/practices, but must work to create a respectful space for conversation and reflection in order to gradually transform our moral perspectives.

The post Thinking about how we think about morality appeared first on OUPblog.

March 21, 2015

From news journalism to academic publishing

“I think I’ve just got an exclusive interview with the new Royal Bank of Scotland chief executive Stephen Hester.” These were the words I told my editor after a couple of years in the newspaper game. He was obviously pleased.

This is the kind of thing editors constantly want from reporters: an ability to dig out a story or to see something not everyone else will spot. It’s a cliché and can be applied to a whole range of careers, but in a way, a newspaper is only as good as its journalists.

So I guess now you might be thinking where this fits in with Oxford University Press. It does—honestly, it does.

Well, for starters, the worlds of publishing and journalism are exciting ones. Very rarely will you find jobs where the belief in the product is higher. As a reporter, you believe you break the best stories (particularly the ones other papers don’t get) and that your readers generally believe in what you write and the overarching concept and mission of a regional or national newspaper (otherwise, why would they read it or buy it?).

Likewise, in publishing, we believe we have the best books out there in our various fields and that people not only believe in the book itself (the content) but have some sort of settled faith that it represents the best of the subject, purely because of the identity of its publisher.

So how does a journalist interviewing politicians, sportsmen, and other apparently cultural icons fare when it comes to getting the best of OUP’s Higher Education publishing out into the market? Quite well I’d like to think.

You see, the key skills are not much different. An understanding of the audience (academics or news consumers), a knowledge of what makes that person tick (an academic’s belief in books or the reader’s taste for a great story), an ability to get them to part with information (academics provide module info while a subject in a newspaper story tells you how their life has been marred by a multi-scale credit card fraud), and a strong belief that you can use what that person gives you to do your job well (sell books more efficiently or write an exclusive front-page story as a result of an interview).

The crucial difference, I guess, would be that my job at Oxford University Press doesn’t require me to go and speak to the wife of Colin McRae the day after her husband died in a helicopter crash (thank goodness). Nor does it ask me to get into a conversation with David Cameron at a charity event about a quote to do with spending cuts (once again, thankfulness here).

What it does require of me, though, is a knack for taking new information, downloading it to my brain, and asserting confidence when it comes to talking to some of the country’s biggest brains. And that’s not bad.

The post From news journalism to academic publishing appeared first on OUPblog.

Getting to know Richard Woodall, Higher Education Sales Executive

From time to time, we try to give you a glimpse into our offices around the globe. This week, Richard Woodall, a former journalist and Higher Education Sales Executive in Oxford, writes about the similarities between news journalism and academic publishing. Richard has been working at the Oxford University Press since September 2014.

“I think I’ve just got an exclusive interview with the new Royal Bank of Scotland chief executive Stephen Hester.” These were the words I told my editor after a couple of years in the newspaper game. He was obviously pleased.

This is the kind of thing editors constantly want from reporters: an ability to dig out a story or to see something not everyone else will spot. It’s a cliché and can be applied to a whole range of careers, but in a way, a newspaper is only as good as its journalists.

So I guess now you might be thinking where this fits in with Oxford University Press. It does—honestly, it does.

Well, for starters, the worlds of publishing and journalism are exciting ones. Very rarely will you find jobs where the belief in the product is higher. As a reporter, you believe you break the best stories (particularly the ones other papers don’t get) and that your readers generally believe in what you write and the overarching concept and mission of a regional or national newspaper (otherwise, why would they read it or buy it?).

Likewise, in publishing, we believe we have the best books out there in our various fields and that people not only believe in the book itself (the content) but have some sort of settled faith that it represents the best of the subject, purely because of the identity of its publisher.

So how does a journalist interviewing politicians, sportsmen, and other apparently cultural icons fare when it comes to getting the best of OUP’s Higher Education publishing out into the market? Quite well I’d like to think.

You see, the key skills are not much different. An understanding of the audience (academics or news consumers), a knowledge of what makes that person tick (an academic’s belief in books or the reader’s taste for a great story), an ability to get them to part with information (academics provide module info while a subject in a newspaper story tells you how their life has been marred by a multi-scale credit card fraud), and a strong belief that you can use what that person gives you to do your job well (sell books more efficiently or write an exclusive front-page story as a result of an interview).

The crucial difference, I guess, would be that my job at Oxford University Press doesn’t require me to go and speak to the wife of Colin McRae the day after her husband died in a helicopter crash (thank goodness). Nor does it ask me to get into a conversation with David Cameron at a charity event about a quote to do with spending cuts (once again, thankfulness here).

What it does require of me, though, is a knack for taking new information, downloading it to my brain, and asserting confidence when it comes to talking to some of the country’s biggest brains. And that’s not bad.

The post Getting to know Richard Woodall, Higher Education Sales Executive appeared first on OUPblog.

How false discoveries in chemistry led to progress in science

In the popular imagination, science proceeds with great leaps of discovery — new planets, new cures, new elements. In reality, though, science is a long, grueling process of trial and error, in which tantalizing false discoveries constantly arise and vanish on further examination. These failures can teach us as much — or more — than its successes. The field of chemistry is littered with them. Today only 118 elements have been documented, but hundreds more have been “discovered” over the years — named, publicly trumpeted, and sometimes even included in textbooks — only to be exposed as bogus with better tools, or when a fraud was sniffed out. Their stories, sprinkled with stubborn pride, analytical incompetency, precipitate haste, amateurish error, and even practical joking, read like a catalog of the ways science can go awry, and how it moves forward nonetheless. Here are some illustrative “lost element” stories and their discoverers — and what we can learn in spite of them.

Junonium was “discovered” by Sir John Herschel in 1858. Herschel was a renowned astronomer, mathematician, and photographer, but not a trained chemist. Junonium was just one of a new class of “photochemical” elements that could never be substantiated, let alone isolated.

Victorium was “discovered” by Sir William Crookes in 1898. Crookes imprudently announced the discovery of a new element that was later shown to be a mixture of gadolinium and terbium. He first called this element monium, and then exacerbated his error by renaming it in honor Queen Victoria, who had recently knighted him.

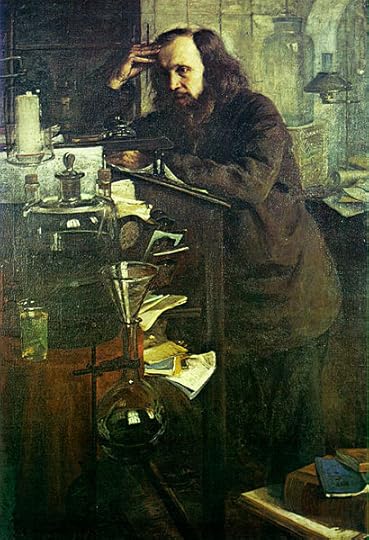

Newtonium and coronium were “discovered” by Dmitri Mendeleev in 1903. Mendeleev is famous for having discovered (and publicized) the periodic law of the elements. What is less well known is that he postulated the existence of elements lighter than air, among them newtonium and coronium. His claims were largely a paranoid response to the discovery of the electron, which he thought would compromise the validity of “his” periodic table.

Dmitri Mendeleev, Museum Archive of Dmitri Mendeleev at the Saint Petersburg State University. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Dmitri Mendeleev, Museum Archive of Dmitri Mendeleev at the Saint Petersburg State University. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Occultum was “discovered” by Annie Besant and Charles W. Leadbeater in 1909. Clairvoyants Besant and Leadbeater claimed to use their cognitive powers to observe the entire atomic universe, slowing down its movement by “force of will” and describing bizarre elements like occultum and anu in great detail. Their book “Occult Chemistry” went into three editions.

Neo-holmium was “discovered” by Josef Maria Eder in 1911. Very influential in photography, Eder postulated this and other nonexistent rare-earth elements on the basis of flimsy and misinterpreted spectroscopic data. Inexperienced and “out-of-field” in this kind of chemistry, he failed to recognize that his samples contained impurities that skewed the results, leading to errors spanning almost a decade.

Celtium was “discovered” by Georges Urbain in 1922. Flimsy evidence on impure samples led Urbain to fall into a trap which was the same kind of error for which he had blamed others for falling into, detecting an “element” where one didn’t exist.

Hibernium was “discovered” by John Joly in 1922. An Irish physicist and geologist, Joly was the first to deduce that the age of the earth might be measured in billions rather than thousands of years. He theorized that strange halo-like marks in mica samples were caused by a radioactive element that he called hibernium. He inferred too much from too little data; it was later found that the causative substance was a radioactive isotope of an already known element.

Florentium was “discovered” by Luigi Rolla in 1927. Many scientists were on the hunt for the elusive element 61. Rolla carried out over 50,000 chemical separations in an attempt to isolate it from naturally occurring rare earth mixtures. Soon after announcing the discovery, he realized it was in error, but he retracted it only 15 years later in an obscure journal published, partially in Latin.

Virginium and Alabamine were “discovered” by Fred Allison in 1931-32. Allison was among many scientists seeking the elements 85 and 87, which were missing spots on the periodic table. He devised an apparatus based on what he called the “magneto-optic” method of analysis, and then claimed to have observed both. Although quickly shown to be false, these elements remained in the periodic tables of chemistry textbooks for years.

Ausonium and hesperium were “discovered” by Enrico Fermi in 1934. The great physicist and his team bombarded uranium with neutrons and detected what seemed like unknown atoms. Despite their caution, their university administrator announced the two “new” elements, and Fermi received the 1938 Nobel Prize in consequence. He never admitted his Nobel was based on a false discovery. Interpreted correctly, he had found the first evidence of nuclear fission, which would have deserved the Nobel anyway.

Element 118 was “discovered” by Victor Ninov in 1999. In the mid-1990s, Ninov helped discover elements 110, 111, and 112 in Germany using a data-analysis code that he developed. He moved to Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory and in 1999 announced the synthesis of element 118; only Ninov had access to the raw data, and it took 3 years to discover that he had deliberately falsified them. Ninov was fired in 2002.

Featured Image: Chemicals in flasks by Joe Sullivan. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How false discoveries in chemistry led to progress in science appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers